We apologize for the inconvenience...

To ensure we keep this website safe, please can you confirm you are a human by ticking the box below.

If you are unable to complete the above request please contact us using the below link, providing a screenshot of your experience.

https://ioppublishing.org/contacts/

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Informal Urban Settlements and Slums’ Upgrading: Global Case Studies

Resilience of Informal Areas in Megacities – Magnitude, Challenges, and Policies

Related Papers

Rachid Choghary

Sustainable Development

Andrew Jorgenson

Current History

Global Report on Human Settlements

The Challenge of Slums presents the first global assessment of slums, emphasizing their problems and prospects. It presents estimates of the numbers of urban slum dwellers and examines the factors that underlie the formation of slums, as well as their social, spatial and economic characteristics and dynamics. It also evaluates the principal policy responses to the slum challenge of the last few decades. The report argues that the number of slum dwellers is growing and will continue to increase unless there is serious and concerted action by all relevant stakeholders. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This book is 20 years old, but still contains much important material. It was my major undertaking after working in and with UN-Habitat for ten years. Many people contributed to the book and I edited the submissions into a consistent style and narrative. My main direct contribution was the material about inequality in Chapters 2, 3 and 4,. It was very controversial and full credit is due to UN-Habitat for slipping the yoke of WB/IMF and publishing it. I was also responsible for the material about cultural innovations emerging from "vibrant mixed urban communities'. The process of development of the report was heavily contested, due to UN-Habitat's desire to use it for advocacy, while the authors were more concerned with accuracy and clarity. First, researchers thought that 'slum' was not a viable concept for statistical purposes, and could not be defined, but UN-Habitat wanted it. Next they they wanted a billion slum dwellers. I considered that from the definitions laid down by the Expert Group there were 'only' half a billion. This was not good enough. So UN-Habitat wrote the first chapter with a billion slum dwellers. This was the main factoid publicising the report World Bank were not happy and commissioned an audit. It emerged that a billion was the number of people who did not have adequate sanitation, which included very many in China not living in "slums". Despite these disputes, the report stands as the flagship introduction to informal settlements "slums" globally.

The Contemporary Urban Conundrum. New Delhi: Routledge.

Swastik Harish

Urban Science

Jota Samper

Slums are a structural feature of urbanization, and shifting urbanization trends underline their significance for the cities of tomorrow. Despite their importance, data and knowledge on slums are very limited. In consideration of the current data landscape, it is not possible to answer one of the most essential questions: Where are slums located? The goal of this study is to provide a more nuanced understanding of the geography of slums and their growth trajectories. The methods rely on the combination of different datasets (city-level slum maps, world cities, global human settlements layer, Atlas of Informality). Slum data from city-level maps form the backbone of this research and are made compatible by differentiating between the municipal area, the urbanized area, and the area beyond. This study quantifies the location of slums in 30 cities, and our findings show that only half of all slums are located within the administrative borders of cities. Spatial growth has also shifted outwards. However, this phenomenon is very different in different regions of the world; the municipality captures less than half of all slums in Africa and the Middle East but almost two-thirds of all slums in cities of South Asia. These insights are used to estimate land requirements within the Sustainable Development Goals time frame. In 2015, almost one billion slum residents occupied a land area as large as twice the size of the country of Portugal. The estimated 380 million residents to be added up to 2030 will need land equivalent to the size of the country of Egypt. This land will be added to cities mainly outside their administrative borders. Insights are provided on how this land demand differs within cities and between world regions. Such novel insights are highly relevant to the policy actions needed to achieve Target 11.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (“by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services, and upgrade slums”) as interventions targeted at slums or informal settlements are strongly linked to political and administrative boundaries. More research is needed to draw attention to the urban expansion of cities and the role of slums and informal settlements.

Andrew Crooks , Arie Croitoru , ron mahabir

Over 1 billion people currently live in slums, with the number of slum dwellers only expected to grow in the coming decades. The vast majority of slums are located in and around urban centres in the less economically developed countries, which are also experiencing greater rates of urbanization compared with more developed countries. This rapid rate of urbanization is cause for significant concern given that many of these countries often lack the ability to provide the infrastructure (e.g., roads and affordable housing) and basic services (e.g., water and sanitation) to provide adequately for the increasing influx of people into cities. While research on slums has been ongoing, such work has mainly focused on one of three constructs: exploring the socio-economic and policy issues; exploring the physical characteristics; and, lastly, those modelling slums. This paper reviews these lines of research and argues that while each is valuable, there is a need for a more holistic approach for studying slums to truly understand them. By synthesizing the social and physical constructs, this paper provides a more holistic synthesis of the problem, which can potentially lead to a deeper understanding and, consequently, better approaches for tackling the challenge of slums at the local, national and regional scales.

James Rice , Andrew Jorgenson

Habitat International

Richard Sliuzas

American Journal of Public Health

Elliott Sclar

RELATED PAPERS

Roman Trobec

Annemarie Profanter

História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos

Guilherme Arantes Mello

Wildlife Rehabilitation Bulletin

Mark Pokras

World journal of gastroenterology : WJG

ramang magga

Atlantic Journal of Communication

Rebecca Steiner

Muhebbi Al Hudi

Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics

Zhitao Shen

Dinamik Jurnal Teknologi Informasi

Eri Zuliarso

Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi

Şener Uysal

Águas Subterrâneas

Maria Cristina Santiago

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Serghei Corcimaru

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

Juan Carlos Matallín Sáez

Hugo Chirinos

Annals of clinical and laboratory science

Leonard I. Boral

emmanuel garcia

Quipukamayoc

Revista Quipukamayoc

Presentasi Pajak 1

Frontiers in Physiology

Aleksandar Kalauzi

Enciclopédia Biosfera

Geovana Lopes Pereira

Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering

Maria Polese

Lewis Perkins

Turizmus Bulletin

Hinek Mátyás

Hpb Surgery

PRATIMA CHAURASIA

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Data Descriptor

- Open access

- Published: 09 January 2018

Survey-based socio-economic data from slums in Bangalore, India

- Debraj Roy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3579-7219 1 , 2 ,

- Bharath Palavalli 3 ,

- Niveditha Menon 4 ,

- Robin King 5 , 6 ,

- Karin Pfeffer 1 ,

- Michael Lees 1 , 7 &

- Peter M. A. Sloot ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3848-5395 1 , 2 , 7

Scientific Data volume 5 , Article number: 170200 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

31 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Socioeconomic scenarios

In 2010, an estimated 860 million people were living in slums worldwide, with around 60 million added to the slum population between 2000 and 2010. In 2011, 200 million people in urban Indian households were considered to live in slums. In order to address and create slum development programmes and poverty alleviation methods, it is necessary to understand the needs of these communities. Therefore, we require data with high granularity in the Indian context. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of highly granular data at the level of individual slums. We collected the data presented in this paper in partnership with the slum dwellers in order to overcome the challenges such as validity and efficacy of self reported data. Our survey of Bangalore covered 36 slums across the city. The slums were chosen based on stratification criteria, which included geographical location of the slum, whether the slum was resettled or rehabilitated, notification status of the slum, the size of the slum and the religious profile. This paper describes the relational model of the slum dataset, the variables in the dataset, the variables constructed for analysis and the issues identified with the dataset. The data collected includes around 267,894 data points spread over 242 questions for 1,107 households. The dataset can facilitate interdisciplinary research on spatial and temporal dynamics of urban poverty and well-being in the context of rapid urbanization of cities in developing countries.

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Similar content being viewed by others

Multidimensional well-being of US households at a fine spatial scale using fused household surveys

Kevin Ummel, Miguel Poblete-Cazenave, … Narasimha D. Rao

A subnational reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and development atlas of India

Carla Pezzulo, Natalia Tejedor-Garavito, … Andrew J. Tatem

Social dynamics of short term variability in key measures of household and community wellbeing in Bangladesh

Md. Ehsanul Haque Tamal, Andrew R. Bell, … Patrick S. Ward

Background & Summary

Cities have become engines of accelerated growth as they are centres of high productivity and provide easy access to resources 1 . The outcome of this high rate of urbanization has been the rise of informal settlements or ‘slums’, characterized by a lack of adequate living space, insecure tenure and public services 2 . In 2010, an estimated 860 million people were living in slums worldwide with around 60 million added to the slum population between 2000 and 2010. In sub-Saharan Africa, the slum population doubles every 4.5 years 3 . In the past decade, over 22 million people have migrated from rural to urban areas in India 4 . While official estimates indicate that the number of slum dwellers in India increased from 30 million in 1981 to over 61 million in 2001 4 , a UN Habitat report estimates the number of slum dwellers in India to be over 100 million. In 2011, 200 million people in urban Indian households were considered to live in slums 5 , of which over a third were in million-plus cities of India.

In this paper, we present granular data about slums from the city of Bangalore in India. Bangalore grew exponentially from 1941 to 1971 6 and is now rapidly growing due to the establishment of the software industry in the city. The urban agglomeration of Bangalore is the administrative capital of the state of Karnataka in India, with a metropolitan population of about 11.52 million and a population growth rate of 47.18% 5 , making it the third most populous city and fifth most populous urban agglomeration in India. The city has seen phases of growth that correspond to the different waves of industrialization and immigration. The first wave of immigration took place between 1880 and 1920, when the textile industry developed in the western part of the city. The second wave of industrialization took place in the eastern and northern areas, when a slew of state owned industries were created between 1940 and 1960. At the same time, state owned research and development establishments were created in the north western region of the city. The final wave can be characterized post 1990, with the establishment of special economic zones for electronics and the IT industry (which was initiated in the 1980s by the state government). To meet housing needs, in the period between the 1980s–1990s, state owned bodies created townships for their employees at the periphery, while housing co-operative societies met the demand for those in the formal sector 6 . A rapid shortage of housing and increased demand for manpower in the city has led to the growth and emergence of slums in Bangalore. The number of slums in Bangalore has grown from 159 in 1971 to over 2000 slums (notified and non-notified) in 2015. Those living in slums accounted for just over 10% of the city’s population in 1971 and an estimated 25 to 35% in 2015.

However, one of the biggest problems associated with studying slum populations is that, despite being ubiquitous, their needs, issues and problems are often invisible due to lack of representation. In this data collection effort the lack of accessibility to slums because of the social distance between the researcher and the respondent was overcome by the use of participatory methods. In order to measure poverty in slums, previous studies have often relied on consumption and income indicators. A Basic Needs Index requires data on literacy, water (piped), sanitation facilities and food requirements 7 . Well-being and vulnerability indicators have used household assets, access to financial services and formal safety nets and social networks 8 . In order to acknowledge the shift in thinking towards multi-dimensional poverty, we ensured that the survey moved away from consumption indicators to well-being and vulnerability indicators. The primary questions for this survey included the economic contribution of the urban poor in the city, the affordability and accessibility of infrastructure facilities, the various migration streams and access to financial systems. Using a participatory method, the survey was conducted in 1,107 households in 36 slums, with each household answering 242 questions. This study and the data descriptor provides a template for future data that can be collected to provide a better understanding of slums in other cities. The data can be used to generate a wide range of measures to study the impact of various programs on the slum dwellers, their expenditure patterns and the economic profile of the slums.

The main purpose of the study was to obtain a better understanding of the nature of urban poverty, to unpack the needs, issues and problems of slum dwellers, but also how slum-dwellers contribute to the urban economy and why households live in slums. The primary research questions were:

What is the economic contribution (labour, production aspects) of the urban poor to the city’s economy?

What are the infrastructure facilities (health, education, water, mobility, sanitation) that are available? Are they affordable, accessible and who pays for it (state/private)?

What are the key drivers of migration flows in and out of the city? When do people enter/leave a slum?

What is the demographic and economic profile of the people living in slums?

Do slum dwellers have access to financial systems and savings?

What are the expenditures of people in the slums?

We combined a structured survey with focus groups and personal interviews. While the structured survey supported the systematic data collection, the use of the qualitative methods such as focus group discussions. Personal interviews allowed for individuals living in the slums to articulate their concerns and also supported further processing of the data, for instance to create categories. The design of the questionnaire was informed by our research questions and former surveys carried out in Bangalore, a survey developed earlier by the Word Bank 9 and surveys reported in literature 10 – 12 . The slum-survey was done in collaboration with slum dwellers to get access to slum areas and have sufficient trust between surveyor and respondent to obtain a higher validity in the answers. The following sections describe the sampling strategy used to randomly select households and individuals for the survey and survey implementation.

Sampling strategy

The slums in Bangalore were stratified based on the following parameters: Age of the Slum (Old, New), Location in the city (Core, Periphery, North, South, East, West); Size of the slum; Land Type (whether the slums are on Public land or Private land); Declaration Status (Declared or Not Declared); Major Linguistic Group (slums that contain a majority of Kannada, Tamil, or Telugu speakers); Major Religious Group (slums that contain a majority of Hindi, Muslim, or Christian populations) and State of Development (Redeveloped slums, Resettled slums, In situ developed and Planned slums). A list of 597 slums was compiled using the notified, non-notified and de-notified slums published by Karnataka Slum Clearance Board (now the Karnataka Slum Development Board). A total of 51 slums were short-listed based on the stratification criteria, after which 36 were surveyed based on verbal consent provided by the slum leaders. The following question guides the calculation of samples.

How many households should be surveyed to estimate the true proportion of households who are below the poverty line (or do not have access to finance/ water etc), with a 95% confidence interval 6% wide? The 95% confidence interval is a standard used across disciplines. We have used a width of 6% instead of 10% (standard used across disciplines) to overestimate the number of samples (in case of missed households).

The required sample size ( X ) for the slum households was then calculated using the following formula 13 :

where, N is the entire population of slum households in Bangalore and

where Z is the Z-score ( Z is 1.96 for a 95% confidence level), D is the margin of error (3%), P is the estimated proportion of an attribute (such as households below poverty line) that is present in the population, Q is 1− P . Therefore, P × Q is the estimate of variance of the attribute in the population. Because a proportion of 0.5 indicates the maximum variability of an attribute in a population, it is often used in determining a more conservative sample size. Therefore, applying equation (2), we get n =1,067. The total number of slum households in Bangalore was estimated to be 321,296 (N ) as per the report released by the Karnataka Slum Development Board in 2010. Since, N ≫ n , in equation (1), the calculated sample size is 1,067.

Survey implementation

The social survey was implemented in the city of Bangalore, India with the assistance of Fields of View (FoV), a non-profit research organization, highly experienced in data collection. FoV together with Slum Jagaththu provided intensive training on survey tools, data collection methodology and ethical grounds of social data collection. The questionnaire was designed based on the research questions, after which the stratification and identification of slums (described in section Sampling Strategy) was performed. After the slums were identified, the questionnaire was modified to include questions based on the input and needs of the slum dwellers (see Table 1 ). A set of qualitative interviews on thematic topics were carried out based on the request from the slum dwellers, which served as a reference point for comparison with past surveys. The questionnaire was piloted in 2 slums and then revised after a round of feedback (see Table 2 ). A typical survey procedure consisted of the field coordinator speaking to the local leaders in each slum before the team conducted the survey. The coordinator would then introduce the enumerator team covering that slum to the slum leaders. If the slum leaders were agreeable, they would survey 10% of the slum, based on the procedure elaborated above. Informed consent was obtained at 3 different levels. First, local slum leaders were apprised of the objectives of the survey and the methods. Once local slum leaders approved the survey, we identified and approached community leaders within a slum. After the consent of the community leaders was obtained we approached individual slum households. Efforts were made to ensure that all respondents were appropriately informed about the study and thoroughly understood their participation in the study was voluntary. In the cases where slum leaders or community leaders did not agree to the survey we did not proceed further. In all cases where community leaders agreed to be a part of the survey, all households complied to the request. Participation was voluntary and interviewers ensured that participants knew that refusal to participate would not lead to any adverse consequences. If the main earner was not available at the time of interview then the enumerator excluded that household and moved to the next selected household and then reverted to the normal pattern.

The data was captured in paper questionnaires with handwritten responses, with most answers coded into structured replies (as indicated in the validation section), in addition to a few open-ended questions. Several case studies on thematic topics such as the homeless, informal workers and street vendors were also conducted. These case studies were conducted based on qualitative interviews with the participants and the data is not included in the datasets. The survey was administered by women participants from the slums in order to increase the level of comfort and trust with the participants. The enumerators comprised of fourteen women, who conducted the surveys in teams of two. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated into Kannada (the local language of the state of Karnataka). To ensure quality of the data, a monitoring team from FoV checked one percent of the data and held periodic meetings to provide necessary feedback regarding the field work. The survey was completed in two stages, the first beginning in June 2010 included 20 slums and the second, beginning in March 2011 included 16 slums (see Table 3 ). Direct observation or spot checking in selected houses and re-interviewing with a quality control questionnaire in selected households formed part of the monitoring process. Survey data and accompanying questionnaires are available on the ReShare Repository ( Data Citation 1 ).

The data collected from this survey underwent cleaning and was stored in a relational database for further analysis. More specifically, the data was vetted by the enumerators and research team by randomly picking households and a site visit with field verification was carried out. Once the data was verified by the surveyors, the filled-in questionnaires were translated to English and then digitized by an independent group. The research team then carried out two rounds of validation, in the first round, the data was checked for consistency and outliers and in the second round, the research team coordinated with the enumerators to validate any discrepancies. This paper describes the relational model of the database, how to use it, the variables in the dataset, the variables constructed for analysis and the issues identified with the dataset. The data collected included 267,894 data points spread over 242 questions for 1,107 households.

Code availability

This study did not use any computer codes to generate the dataset. A MySQL relational database was used to store the collected data. A set of SQL queries were used to verify and validate the data.

Data Records

The Survey data is provided in SQL format ( Data Citation 1 ). All 242 questionnaire variables are named according to their number in the questionnaire and fully described in the variable labels. The household listing and survey instruments can be downloaded in English which acts as the code book for the datasets ( Supplementary File 1 ).

Technical Validation

The technical validation and quality control comprised of three stages. The first stage of quality control was done before the survey was carried and it involved: a) thorough pre-testing of the questionnaire; b) translating the questionnaire into Kannada, including local terminology and reverse translating to check quality of translations; c) recruitment of women enumerators from slums and comprehensive training in survey implementation. The survey questionnaire was designed based on the research questions of the project, using questions from other surveys already implemented in India and drawing on the qualitative data collection and expert judgement to create new questions. To ensure that the questions are relevant and meaningful, pre-testing of the quantitative questionnaire was conducted in the study area through pilot surveys and focus group discussions (described in Survey Implementation) prior to finalisation of the questions. Training of the enumerators is essential for effective implementation of a survey. A deep understanding of the questions and philosophy of the survey ensured that enumerators can help the surveyed households in answering the questions properly. To achieve this, the enumerator team was selected from the local slums (described in Survey Implementation). Role play and field practice was carried out for every section of the questionnaire.

The second stage of validation was performed during the survey and it involved field quality control questionnaires being carried out alongside the main data collection as described below. A quality control team was assigned in the field to monitor data collection. The field quality control involved quality control visits, spot check visits and checking of forms as recommended by the Demographic Surveillance Systems guidelines. Quality control visits was done by the supervisor on 5% 14 , 15 of the households in each round of data collection. It provided a way of cross-checking the accuracy and completeness of the data. Random and unannounced spot check visits were conducted to ensure that the data collection was being done as per the schedule. Finally, during the survey a field supervisor checked all the completed forms for completeness (no missing values and units) and accuracy before they were submitted for data entry. To ensure the data is accurate all possible inconsistencies (e.g., range checks, checking that only females have given birth) were checked. Forms with omissions and obvious errors were returned to the fieldworker for correction or revisits. The field quality control exercise demonstrated that most respondents were not willing to disclose their caste as it is considered sensitive in India. At the point of data entry a further checking of the forms is performed and forms that have errors or inconsistencies were returned to the fieldworker via his/her supervisor. The built-in validation during data entry comprised of standard methods such as uniqueness check, referential integrity, presence check, length check, data type check, fixed value check and cross field check 16 .

The final stage of validation was after the survey was completed and it involved checking data entry, detecting typing errors and comparison with previous studies. Two-pass verification, also called double data entry was performed to ensure correct data entry. To identify data entry errors, individual and composite variables were summarised as minimum, median, mean, maximum and compared between the two data entries. The original paper version has been retained to allow the team to check individual records in the digital dataset if necessary. Further, in this section we present a detailed quantitative validation of the survey data by comparing frequency distributions with previous studies and census surveys. First, we validate the demographic variables in the survey.

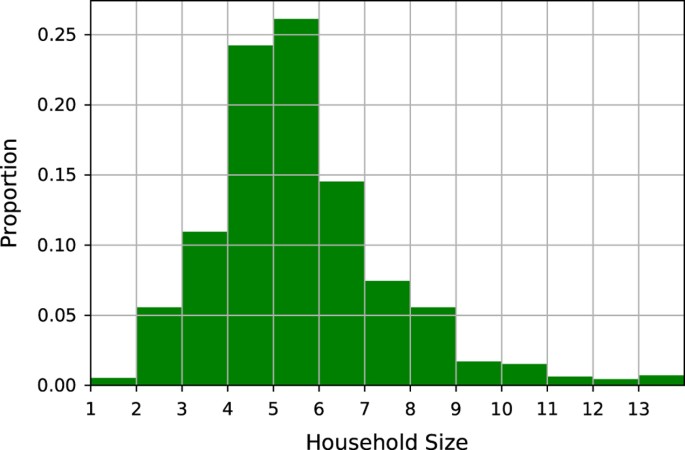

The median household size in the slums of Bangalore is 5. We find that 25% of the families have a household size of up to 4 members and 75% of the slum dwellers have a household size of up to 6 members. The maximum size of a household in the survey is 13. Figure 1 shows the family size distribution across the 36 surveyed slums in Bangalore. Table 4 indicates that the gender ratio (female to male ratio) is around 1, which is different to the trend in non-slum urban households where there are around 966 female per 1,000 male. A similar deviation has been observed in the Census of India 2011 5 and other slum studies in Bangalore 17 . Table 4 also shows that the population in the slum is young, with 35% of the respondents under the age of 18 and around 70% under the age of 35. The age distribution is consistent with the data from Census of India 2011 5 . The majority of surveyed households (67%) are Hindus. About 20% of the respondents are Muslims and 8% are Christians. The native language of 45% of surveyed households is Tamil, while 17% speak Kannada and 15% speak Telugu. Analysis of the migration data from slums show that 73% of migrants are from rural areas within Karnataka itself while the remaining 27% migrated from the rest of India, which indicates that the native language may not be an indication of migration. The above social and demographic distribution are similar to values reported in various slum studies of Bangalore 17 – 21 .

The data indicates that the average age at marriage is 24 for men and 17 for women. This is lower than the average of non-slum urban households in Bangalore, where the average age of marriage is 27.5 for men and 24 for women 5 . The median age of marriage has been rising in India. However, 49% of all women in the survey, were married before the age of 17. The median age at first pregnancy in slums of Bangalore is around 18 years, which is significantly lower than the median age of 25 years for non-slum urban households in Bangalore 5 . The average age at marriage and pregnancy are similar to the reported values in various slum studies of Bangalore 22 , 23 .

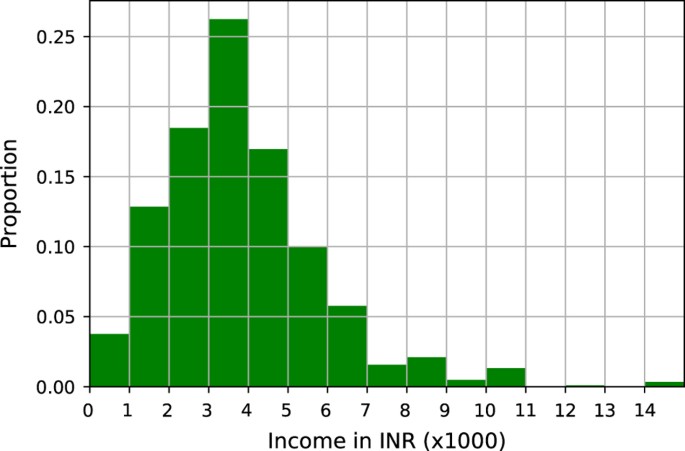

Second, we validate the data pertaining to income, expenditure and assets in the survey. The income distribution (see Fig. 2 ) shows that 25% of sample respondents earn a monthly income of less than 2,000 INR (31 USD), out of which they spend 93% on basic amenities. Around 75% of the sample respondents earn a monthly income lower than INR 4,000 (62 USD) and spend 91% of their income on basic amenities. Around 13% of households earn more than 10,000 INR (156 USD) per month and spend around 77% of their income on basic amenities. The monthly median income of slum dwellers in Bangalore is around 3,000 INR (47 USD). The median income reported in previous studies is around 3,500 INR (54 USD) 17 – 19 . Table 5 shows that the slum households spend the majority of their income on food items. The reasons for this high percentage are low income level coupled with high food inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which was 12.56% during 2013. Hence, money available for other activities is very low. Education is a priority for the urban poor, but only the top 10% highest earning households can afford a school education for their children. The other key components which contribute to the expenditure are home appliances, rent, healthcare and clothing. The expenditure patterns observed in the data are consistent with previous findings 17 , 18 .

In the surveyed slums, television sets, mobile phones and electric fans are the common asset types, with more than 75% reporting ownership of each of these assets. The least common form of assets are cars, trucks and agricultural land, possessed by less than 1% of all slum households. Bicycles or motorcycles/scooters are also owned by fewer than 20% of these households. The asset distribution we observe is similar to previous studies in the slums of Bangalore 17 , 18 .

When we examine the employment patterns in the slums, we find that most slum dwellers are employed in the informal sector, primarily working as domestic help or as manual labour. Only 13% of the sample respondents are employed in the formal sector (White collar, blue collar and sales occupations). These findings are similar to the reported values in various slum studies of Bangalore 17 – 21 . Further, we find that the slum-based micro enterprises are not served by traditional financial institutions due to their informal status ( Table 6 ). Again, this is consistent with previous studies, for example the study conducted by Society for Participatory Research in Asia 17 .

Finally, we validate the data pertaining to physical structure of the houses and tenure in the survey. The survey data indicates that around 40% of the slum households have Hakku Patra , which is an important document given by Tehsildar for land ownership indicating title to the dwelling. This indicates that the majority of slum dwellers possess legal titles. Households with a legal title to their dwelling usually live in pukka structures. A pukka structure is a semi-permanent structure with a tiled or stone roof and walls that are wooden, metal, asbestos sheets, burnt brick, stone, concrete or cement bricks. Around 20% of the households have a Possession Certificate document and live in semi-pukka houses. The remaining 40%, who have either migrated from neighbouring districts or other states, do not have any proper ownership to land and live in kutcha structures. A kutcha structure is one whose roof is built using grass, thatch, bamboo, plastic, polythene, metal, asbestos sheets and walls that are grass, thatch, bamboo, plastic, polythene, mud, burnt brick, wood, metal, asbestos sheets (See Table 7 ). Analysis of ration card data from the slums in Bangalore shows that around 3% of households have Antyodaya cards, 60% possess below poverty line (BPL) cards and 17% have the above poverty line (APL) card. A comparison with the study conducted by Society for Participatory Research in Asia 17 shows that the above distributions are comparable.

Usage Notes

Data access conditions.

A benefit of the data is its spatial nature, which allows social factors to be analysed in the context of environmental conditions and resources. However, this increases the sensitivity of the data as it creates the potential for households within each slum to be identified from the survey data. As such, the data has been made available as safeguarded on the UK Data Archive’s data repository ReShare. In order to download safeguarded data the user must register with the UKDA and agree to the conditions of their End User Licence (For conditions of the End User Licence see: https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/how-to-access/conditions ). For commercial use, please contact the UK Data Service at [email protected].

The diversity of variables collected in the survey instrument create a high possibility for reuse of this dataset. Furthermore, certain variables are comparable with the standard National Family Health Survey v.2,3,4 surveys of Bangalore and the national census, offering the possibility of longitudinal analysis. The dataset can be used to test key associations between social and land-use outcomes that are critical for environmental policy and development strategies for Bangalore.

For example, there are a range of variables that will allow researchers to examine the social relationships that affect livelihoods in slums such as money lending, informal labour, remittances and assets. Comprehensive data on expenditure, income and livelihood choices could be used to model growth and emergence of slums (e.g., ref. 24 ) and design strategic slum management interventions, ranging from improvements in public distribution system, through to social interventions in availability of credit, or supporting mobility and migration. The dataset can be disaggregated by group identities, and crucially includes information on seasonal variation in occupation and livelihoods, a critical issue in the variation of well-being and poverty.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Roy, D. et al. Survey-based socio-economic data from slums in Bangalore, India. Sci. Data 5:170200 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.200 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Moreno, E. & Warah, R. The State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/2007: 30 Years of Shaping the Habitat Agenda , Report No. HS/815/06E (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2006).

Google Scholar

Roy, D., Lees, M. H., Palavalli, B., Pfeffer, K. & Sloot, P. M. A. The emergence of slums: A contemporary view on simulation models. Environ Modell Softw. 59 , 76–90 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Moreno, E., Arimah, B. C., Mboup, G., Halfani, M. & Oyeyinka, O. State of the world’s cities 2012/2013: Prosperity of cities (Report No. HS/080/12E United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2012).

Revi, A. Urban India 2011: Evidence (Report No. 3 Indian Institute of Human Settlements, 2012).

Book Google Scholar

Chandramouli, C. Census of India (The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, New Delhi, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2011).

Nair, J. The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Baker, J. Analyzing Urban Poverty: A Summary of Methods and Approaches (World Bank Publications, 2004).

Deaton, A. Income, health and wellbeing around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect. 22 , 1–8 (2008).

Sapsford, R. Survey Research (SAGE Publications Limited, 2007).

Grosh, M. & Glewwe, P. Designing Household Survey Questionnaires for Developing Countries Lessons from 15 Years of the Living Standards Measurement Study Volume 3 (World Bank, 2000).

Shiri, G. Our Slums: Mirror a Systemic Malady: An Empirical Case Study of Bangalore Slums (Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society, 1999).

Deaton, A. & Grosh, M. Designing Household Survey Questionnaires for Developing Countries: Lessons from Ten Years of LSMS Experience (World Bank, 1998).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques . 2nd edn. (John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1963).

MATH Google Scholar

Indepth Network. Resource kit for Demographic Surveillance Systems . Ihttp://www.indepth-network.org/ (2008).

Adams, H. et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of multidimensional well-being, livelihoods and ecosystem services in coastal Bangladesh. Sci. Data. 3 , 94 (2016).

Maydanchik, A. Data Quality Assessment (Technics publications, 2007).

Society for Participatory Research in Asia. Bengaluru Study Report 2014 https://www.pria.org/ (2014).

Krishna, A. Stuck in Place: Investigating Social Mobility in 14 Bangalore Slums. J Dev Stud 49 , 1010–1028 (2013).

Marimuthu, P., Babu, B. V., Sekar, K., Sharma, M. K. & Manikappa, S. Effect of socio-demographic characteristics on the morbidity prevalence among the urban poor in a metropolitan city of South India. Int J Community Med Public Health 4 , 173–177 (2014).

Krishna, A., Sriram, M. S. & Prakash, P. Slum types and adaptation strategies: identifying policy-relevant differences in Bangalore. Environ Urban. 26 , 568–585 (2014).

Shivashankara, G. P. Household Environmental Problems In Developing Countries. Wit Trans Ecol Envir 153 , 287–298 (2011).

Rocca, C. H., Rathod, S., Falle, T., Pande, R. P. & Krishnan, S. Challenging assumptions about women’s empowerment: Social and Economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int J Epidemiol. 38 , 577–585 (2011).

Krishna, A. Family Migration into Bangalore. Econ Polit Wkly. 12 , 1–8 (1960).

Roy, D., Lees, M. H., Pfeffer, K. & Sloot, P. M. Modelling the impact of household life cycle on slums in Bangalore. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 64 , 275–287 (2017).

Data Citations

Roy, D., Palavalli, B., Menon, N., King, R., & Sloot, P. M. UK Data Service ReShare https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-852705 (2017)

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from the Dutch NWO, eScience project number 027.015.G05 ‘DynaSlum: Data Driven Modelling and Decision Support for Slums’, Russian Science Foundation project number 14-21-00137 ‘Supercomputer modelling of critical phenomena in complex social systems’, SimCity project of the Dutch NWO, eScience agency under contract C.2324.0293. The authors also acknowledge the support of Mr. Isaac Arul Selva from ‘Slum Jagaththu’ for his contribution towards collecting the data as the liaison with the slums (access to the slums and data collection) and Ms. Bhagyalakshmi Srinivas from ‘Fields of View’ for training the field surveyors and cleaning the data. The survey was carried out with grants from Jamshedji Tata Trust, India and the Next Generation Infrastructure Foundation, Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1098 XH, The Netherlands

Debraj Roy, Karin Pfeffer, Michael Lees & Peter M. A. Sloot

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 639798, Singapore

Debraj Roy & Peter M. A. Sloot

Fields of View, Bangalore, 560078, India

Bharath Palavalli

Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, Bangalore, 560004, India

Niveditha Menon

Urban Development, Ross Center for Sustainable Cities, World Resources Institute, Washington, DC 20002, USA

School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20057, USA,

National Research University ITMO, St Petersburg, 197101, Russia

Michael Lees & Peter M. A. Sloot

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.R. wrote sections of this paper and led the writing of the paper, carried out technical validation and quality control of the database received from the survey team; M.L. is also the principal investigator of the DynaSlum project and helped in writing the paper and acted as the daily supervisor for D.R.; K.P. helped in writing the paper and served as the supervisor for B.M.P.; B.M.P. was involved in conceptualization, data collection, verification, data cleaning, analysis, qualitative research and prepared sections of the manuscript; N.M. was involved in conceptualization, analysis, qualitative research and helped with preparing the manuscript; R.K. was the principal investigator for the survey, led the design of the qualitative research of the study; P.M.A.S. is the principal investigator of the SimCITY project and contributed to the design of the study.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Debraj Roy or Peter M. A. Sloot .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ISA-Tab metadata

Supplementary information, supplementary file 1 (pdf 1731 kb), rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files made available in this article.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Roy, D., Palavalli, B., Menon, N. et al. Survey-based socio-economic data from slums in Bangalore, India. Sci Data 5 , 170200 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.200

Download citation

Received : 19 June 2017

Accepted : 28 November 2017

Published : 09 January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.200

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Informal settlements, the emerging response to covid and the imperative of transforming the narrative.

- Amita Bhide

Journal of Social and Economic Development (2021)

Health issues in a Bangalore slum: findings from a household survey using a mobile screening toolkit in Devarajeevanahalli

- Carolin Elizabeth George

- Gift Norman

- Luc de Witte

BMC Public Health (2019)

A dataset on human perception of and response to wildfire smoke

- Mariah Fowler

- Arash Modaresi Rad

- Mojtaba Sadegh

Scientific Data (2019)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Advertisement

Socio-economic and environmental vulnerability of urban slums: a case study of slums at Jammu (India)

- Environmental Pollution led Vulnerability and Risk Assessment for Adaptation and Resilience of Socio-ecological Systems

- Published: 03 November 2023

- Volume 31 , pages 18074–18099, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Shehnaz Khan 1 ,

- Dheeraj Rathore 2 ,

- Anoop Singh 3 ,

- Rekha Kumari 1 &

- Piyush Malaviya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8857-5540 1

374 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Rapid urban population growth, the urbanization of poverty, and the proliferation of slums are being driven to a great extent by this dynamic form of globalization. Consequently, the multifaceted effects of globalization on the poor and low-income populations in the cities need to be better understood in this context, both at the individual level and within the community. Therefore, the present study was conducted to highlight the various determinants affecting the lives and enhancing the vulnerability of the dwellers of four slum settlements present in various areas of Jammu City, India. Emphasis was made to integrate biological, physical, social, and spatial facets of vulnerability to understand the complex dynamics of urban areas in developing countries. A descriptive survey design was used for questions concerning the social and environmental aspects. Social aspects including age, sex, education, religion, caste, profession, and family income that correspond to social stratification acted as baseline information, while both indoor and outdoor environments such as housing conditions, sanitation, personal habits, solid waste disposal, disaster proneness, and air and water pollution problems were taken into consideration to assess the environmental aspect. Results indicated that the slum settlement has a migratory population with permanent or temporary settlements. The status of education and skill level is poor which results in poor economic development and social well-being of the dwellers in slums. The study also identified vulnerability of the population on social and environmental front which could result into severe health issues. The study concluded and recommended policy planning specified for slums for uplifting such unprivileged populations.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Locational analysis of slums and the effects of slum dweller’s activities on the social, economic and ecological facets of the city: insights from Kumasi in Ghana

Stephen Appiah Takyi, Owusu Amponsah, … Emmanuel Mantey

Urban Poverty, Climate Change and Health Risks for Slum Dwellers in Bangladesh

Researching Urban Slum Health in Nima, a Slum in Accra

Data availability.

Not applicable.

Agarwal S, Majumdar A (2004) Participatory Community Health Enquiry and Planning in selected urban slums of Indore, Madhya Pradesh. Indore: USAID Environmental Health Project, Urban Child Health Program

Akter T (2009) Migration and living conditions in urban slums: implications for food security. Unnayan Onneshan, The Innovators, Centre for Research and Action on Development, Dhaka, Bangladesh

APHA (2005) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association, Washington DC, USA

Google Scholar

Banerjee A, Pande R, Vaidya Y, Walton M, Weaver J (2012) Delhi’s slum-dwellers: deprivation, preferences and political engagement among the urban poor. London School of Economics. London: International Growth Centre Working Paper 1–39

Bardhan P (1995) Research on poverty and development twenty years after redistribution with growth. World Bank, Washington, DC

Bhargava A (2006) Estimating short and long run income elasticities of foods and nutrients. Econometrics, Statistics and Computational Approaches in Food and Health Sciences, 81. World scientific publishing Co. Ltd.

Bhat RL (2005) External benefits of women’s education: some evidence from developing countries. J Educ Plann Admin 19(1):5–29

Bloch R, Monroy J, Fox S, Ojo A (2015) Urbanisation and urban expansion in Nigeria . Urbanisation Research Nigeria (URN) Research Report. ICF International, London

Brandes K, Schoebitz L, Kimwaga R, Strande L (2015) SFD promotion initiative Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Burgos S, Ruiz P, Koifman R (2013) Changes to indoor air quality as a result of relocating families from slums to public housing. Atmos Environ 70:179–185

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar

Buttenheim AM (2008) The sanitation environment in urban slums: implications for child health. Popul Environ 30(1–2):26–47

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chen J, Hill AA, Urbano DL (2009) A GIS-based model for urban flood inundation. J Hydrol 373:184–192

Article Google Scholar

Cobbinah PB, Erdiaw-Kwasie MO, Amoateng P (2015) Thinking sustainable development within the framework of poverty and urbanisation in developing countries. Environ Dev 13:18–32

Crow B, Odaba E (2010) Access to water in a Nairobi slum: women’s work and institutional learning. Water Int 35(6):733–747

Daniere AG, Takahashi LM (1999) Environmental behavior in Bangkok, Thailand: a portrait of attitudes, values, and behavior. Econ Dev Cult Change 47(3):525–557

David AM, Mercado SP, Edmundo K, Becker D, Mugisha F (2007) The prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, TB, and vector borne diseases in informal settlements, challenge, opportunities and insights. J Urban Health 84:65–71

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

DESA U (2018) World urbanization prospects: 2018 . Nairobi (Kenya): United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs

Dixon P, Egalite AJ, Humble S, Wolf PJ (2019) Experimental results from a four-year targeted education voucher program in the slums of Delhi, India. World Dev 124:104644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104644

Edberg SCL, Rice EW, Karlin RJ, Allen MJ (2000) Escherichia coli : the best biological drinking water indicator for public health protection. J Appl Microbiol 88(S1):106S-116S

Graf J, Meierhofer R, Wegelin M, Mosler HJ (2008) Water disinfection and hygiene behaviour in an urban slum in Kenya: impact on childhood diarrhoea and influence of beliefs. Int J Environ Health Res 18(5):335–355

Gundry SW, Wright JA, Conroy R, Du Preez M, Genthe B, Moyo S, Mutisi C, Ndamba J, Potgieter N (2006) Contamination of drinking water between source and point-of-use in rural households of South Africa and Zimbabwe: implications for monitoring the millennium development goal for water. Water Pract Technol 1(2):1–9

Gupta HS, Baghel A (1999) Infant mortality in the Indian slums: case studies of Calcutta metropolis and Raipur city. Int J Popul Geogr 5(5):353–366

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Bonzanigo L, Fay M, Kane T, Narloch U, Rozenberg J, Treguer D, Vogt-Schilb A (2015) Shock waves: managing the impacts of climate change on poverty. The World Bank

Hazra J (2002) Calcutta: a study of urban health. In: Akhtar R (ed) Urban health in third world. APH Publishers, New Delhi, pp 93–119

Hoque BA (2003) Handwashing practices and challenges in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Health Res 13(sup1):S81–S87

Indirabai WPS, George S (2002) Assessment of drinking water quality in selected areas of Tiruchirappalli town after floods. Pollut Res 21(3):243–248

CAS Google Scholar

Jankowska MM, Weeks JR, Engstrom R (2011) Do the most vulnerable people live in the worst slums? A spatial analysis of Accra, Ghana. Ann GIS 17(4):221–235

Jarvis BB, Miller JD (2005) Mycotoxins as harmful indoor air contaminants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 66(4):367–372

Jenkins MW, Curtis V (2005) Achieving the ‘good life’: why some people want latrines in rural Benin. Soc Sci Med 61(11):2446–2459

Jha D, Tripathi V (2014) Quality of life in slums of Varanasi city: A comparative study. Transactions of the Institute of Indian Geographers 36(2):172–183

Kalbende S, Dalal L, Bhowal M (2012) The monitoring of airborne mycoflora in indoor air quality of library. J Nat Prod Plant Resour 2:675–679

Karn SK, Shikura S, Harada H (2003) Living environment and health of urban poor: a study in Mumbai. Econ Pol Wkly 38(34):3575–3586

Khullar DR (2006) Mineral resources, India: a comprehensive geography. Kalyani Publishers, New Delhi, pp 630–659

Kimani-Murage EW, Ngindu AM (2007) Quality of water the slum dwellers use: the case of a Kenyan slum. J Urban Health 84(6):829–838

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Krebs CJ (1989) Ecological methodology. Harper and Row Publishers Inc, New York, NY

Krishnaswamy K, Vijayaraghavan K, Gowrinath Sastry J, Hanumantha Rao D, Brahmam G, Radhaiah G, Kashinath K, Vishnuvardhan Rao M (2000) Years of National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau 1972–1997. Indian Council for Medical Research, National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India

Kulabako RN, Nalubega M, Wozei E, Thunvik R (2010) Environmental health practices, constraints and possible interventions in peri-urban settlements in developing countries- a review of Kampala, Uganda. Int J Environ Health Res 20(4):231–257

Kundu N (2003) Understanding slums, the case of Kolkata. United Nations Global Report on Human Settlement, UN-Habitat

Langergraber G, Muellegger E (2005) Ecological sanitation- a way to solve global sanitation problems? Environ Int 31:433–444

Luka RS, Sharma K, Tiwari P (2014) Aeromycoflora of Jackman Memorial Hospital, Bilaspur. Sch Acad J Pharm 3(1):6–8

McClure FJ (1970) Water fluoridation, the search and the victory. US National Institute of Dental Research

Maclean R, Jagannathan S, Panth B (2018) Introduction- education and skills for inclusive growth, green jobs and the greening of economies in Asia. Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, Springer

McFarlane C (2008) Sanitation in Mumbai’s informal settlements: state, ‘slum’, and infrastructure. Environ Plan A 40(1):88–107

McGranahan G, Satterthwaite D (2002) The environmental dimensions of sustainable development for cities. Geography 87(3):213–226

Mesene M, Meskele M, Mengistu T (2022) The proliferation of noise pollution as an urban social problem in Wolaita Sodo city, Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. Cogent Soc Sci 8:1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2103280

Mishra VK, Banerjee A (2020) Socio-economic deprivation among slum dwellers: a case study of migrants in slums of Allahabad. In: Banerjee A, Jana N, Mishra V (eds) Population dynamics in contemporary South Asia. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1668-9_8

Chapter Google Scholar

Montgomery MA, Elimelech M (2007) Water and sanitation in developing countries: Including health in the equation. Environ Sci Technol 41(1):17–24

Article PubMed ADS Google Scholar

Münzel T, Sørensen M, Daiber A (2021) Transportation noise pollution and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 18:619–636. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00532-5

Nair GA, Bohjuari JA, Al-Mariami MA, Attia FA, El-Touml FF (2006) Groundwater quality of north-east Libya. J Environ Biol 27(4):695–700

PubMed Google Scholar

Panesar A, Walther D, Kauter-Eby T, Bieker S, Rohilla S, Augustin K, Wasser H, Schertenleib R (2015) The SuSanA platform and the Shit Flow Diagram-tools to achieve more sustainable sanitation for all 3509

Polydoros A, Cartalis C (2015) Use of Earth observation based indices for the monitoring of built-up area features and dynamics in support of urban energy studies. Energy Build 98:92–99

Rahman A (2006) Assessing income-wise household environmental conditions and disease profile in urban areas: study of an Indian city. GeoJournal 65(3):211–227

Ramakrishna CH, Mallikarjuna Rao D, Subba Rao K, Srinivas N (2009) Studies on groundwater quality in slums of Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh. Asian J Chem 21(6):4246–4250

Renn CE (1970) Investigating water problems. Educational Products Division. LaMotte Chemical Products Company, Maryland

Royuela V, Díaz-Sanchez JP, Romani J (2019) Migration effects on living standards of the left behind. The case of overcrowding levels in Ecuadorian households. Habitat Int 93:102030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102030

Rufener S, Mausezahl D, Mosler HJ, Weingartner R (2010) Quality of drinking water at source and point-of-consumption - drinking cup as a high potential recontamination risk: a field study in Bolivia. J Health Popul Nutr 28(1):34–41

Sheuya SA (2008) Improving the health and lives of people living in slums. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1136(1):298–306

Shibata T, Wilson JL, Watson LM, Nikitin IV, La Ane R, Maidin A (2015) Life in a landfill slum, children’s health, and the millennium development goals. Sci Total Environ 536:408–418

Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar

Singh R, Rathore D (2019) Impact assessment of azulene and chromium on growth and metabolites of wheat and chilli cultivars under biosurfactant augmentation. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 186:109789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109789

Singh R, Rathore D (2021) Effects of fertilization with textile effluent on germination, growth and metabolites of chilli ( Capsicum annum L) cultivars. Environ Process 8:1249–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40710-021-00531-1

Article CAS Google Scholar

Singh R, Glick BR, Rathore D (2020) Role of textile effluent fertilization with biosurfactant to sustain soil quality and nutrient availability. J Environ Manag 268:110664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110664

Singh RL, Rana PB (1979) “Spatial planning in Indian perspective” N.G.S.I. Research Bulletin

Srinivas C, Shankar R, Venkateshwar C, Rao MSS, Reddy RR (2000) Studies on groundwater quality of Hyderabad. Pollut Res 19(2):285–289

Streimikiene D (2014) Housing indicators for assessing quality of life in Lithuania. Intellect Econ 8(1):25–41

Stryjakowska-Sekulska M, Piotraszewska-Pajak A, Szyszka A, Nowicki M, Filipiak M (2007) Microbiological quality of indoor air in university rooms. Pol J Environ Stud 16(4):623–632

Subbaraman R, Nolan L, Shitole T, Sawant K, Shitole S, Sood K, Nanarkar M, Ghannam J, Betancourt TS, Bloom DE, Patil-Deshmukh A (2014) The psychological toll of slum living in Mumbai, India: a mixed methods study. Soc Sci Med 119:155–169

Sultana I (2019) Social factors causing low motivation for primary education among girls in the slums of Karachi. Bull Educ Res 41(3):61–72

Sundari S (2003) Quality of life of migrant households in urban slums. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Environment and Health, Chennai, India 15–17

Tiwari G (2016) Perspectives for integrating housing location considerations and transport planning as a means to face social exclusion in Indian cities. Int Transp Forum

Tumwine J, Thompson J, Katui-Katua M, Mujwahuzi M, Johnstone N, Porras I (2003) Sanitation and hygiene in urban and rural households in East Africa. Int J Environ Health Res 13(2):107–115

UNESCO (2012) Youth and skills: putting education to work. EFA Global Monitoring Report, New York:United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

Van Derslice J, Briscoe J (1993) All coliforms are not created equal: a comparison of the effects of water source and in-house water contamination on infantile diarrheal disease. Water Resour Res 29(7):1983–1995

Article ADS Google Scholar

WHO (2004) Guidelines for drinking-water quality-Recommendations. World Health Organization, Geneva

Wright J, Gundry S, Conroy R (2004) Household drinking water in developing countries: a systematic review of microbiological contamination between source and point-of-use. Tropical Med Int Health 9(1):106–117

Yogendra K, Puttaiah ET (2008) Determination of water quality index and suitability of an urban waterbody in Shimoga Town, Karnataka. Proceedings of Taal 2007: The 12th World Lake Conference 342–346

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Jammu, Jammu, 180006, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Shehnaz Khan, Rekha Kumari & Piyush Malaviya

School of Environment and Sustainable Development, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

Dheeraj Rathore

Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Mehrauli Road, 110016, New Delhi, India

Anoop Singh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by P. M. Experiments and data collection were conducted by S. K. Data analysis was performed by R. K. and S. K. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S. K., D. R., A. S., R. K., and P. M., and all authors commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. The overall study was supervised by P. M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Piyush Malaviya .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval, consent to participate.

Prior consent was taken from the participants before conducting the interviews.

Consent to publish

Prior consent was taken.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Philippe Garrigues

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Khan, S., Rathore, D., Singh, A. et al. Socio-economic and environmental vulnerability of urban slums: a case study of slums at Jammu (India). Environ Sci Pollut Res 31 , 18074–18099 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30630-5

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2022

Accepted : 19 October 2023

Published : 03 November 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30630-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Environmental vulnerability

- Socio-economic

- Sustainable development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Educ Health Promot

Community empowerment for health promotion in slums areas: A narrative review with emphasis on challenges and interventions

Mohammad hosein mehrolhasani.

1 Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

4 Department of Health Management, Policy and Economics, Faculty of Management and Medical Information Sciences, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Vahid Yazdi-Feyzabadi

2 Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Sara Ghasemi

3 Health Services Management Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Community empowerment has been proposed since the 1980s as a way to increase people's power to influence social determinants of health. However, community empowerment for health promotion in urban slums still faces challenges. The present study examined interventions, challenges, actors, scopes, and the consequences mentioned in various studies and with emphasizing interventions and executive challenges tried to create a clear understanding of empowerment programs in slums and improving their health. Narrative review method was used to conduct the study. Databases including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane were searched. The selection of studies was done according to the “community empowerment” defined by the World Health Organization, the concept of bottom–up approach for health promotion of Laverack and Labonte's study and definition of slums by UN-HABITAT. Finally, Hare and Noblit's meta-synthesis was used to analyze the studies. From 15 selected studies, the most intervention proposed for empowerment was identified to be “residents' participation in expressing problems and solutions.” The challenge of “creating a sense of trust and changing some attitudes among residents” was the greatest challenge in the studies. Moreover, “improving living conditions and health services” were the most important outcomes, “slum residents” and “governments” were the most important actors, and “sanitation” was the most important scope among the studies. Having a comprehensive view to the health and its determinants and attention to the factors beyond neighborhood and health sector would lead to fewer implementation challenges and better intervention choices to health promotion of slum dwellers.

Introduction

More than 55% of the world's population live in urban areas. This number is expected to increase to 68% by 2050.[ 1 ] However, the rapid increase in urbanization is accompanied by warnings of higher urban poverty. About one billion people in the world live in slums.[ 2 ] According to the UN-HABITAT, slum dwellers are a group of people who live in similar conditions as in the urban areas that do not have one or more of the following advantages: sustainable and firm housing, access to public health, easy access to safe drinking water, sufficient living space, and property security.[ 3 ] In addition to inadequate health infrastructure, lack of safe water and suitable food and other items, living in marginal and poor urban areas is also accompanied by various crimes and social deprivation.[ 4 , 5 ]

Resolving health challenges and improving the health of urban slum dwellers require understanding the effects of the urban environment on health and generally understanding the effect of social determinants of health.[ 6 , 7 ] Vulnerable urban populations are often more influenced by social determinants than other urban residents.[ 8 ] Social determinants of health include the conditions, under which people live and work. In fact, these factors refer to economic, social, political, and environmental structures and access to health-care services.[ 9 , 10 ]

Differences in the distribution of social determinants of health in a society or between different societies provide a basis for some discrimination and differences in access to resources and cause some to be more deprived than others.[ 10 ] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), deprivation includes “dynamic and multifaceted processes that are manifested at different levels through unequal power relations in interacting with the four main economic, social, political, and cultural areas.”[ 11 ] Powerlessness or inability in a community means that the community has little control over the social determinants of health and life. Therefore, giving power and empowering these groups can improve their health.[ 12 , 13 ]

Empowerment is the process of participation and distribution of power in such a way that people can control the factors and decisions shaping their lives and health. Empowerment can be discussed at three individual, community, and social levels.[ 14 ] Emphasis on community and collective level in the category of empowerment can be observed in the speech of many thinkers. For example, Hoyt-Oliver (2020) with emphasizes on community empowerment, stating that communities can be more organized than individuals alone, and even individual empowerment projects should consider community, values, and cultures.[ 15 ]

As defined by the WHO, “community empowerment refers to the process of enabling communities to increase control over their own lives. Community are groups of people who share common interests, concerns, or identities and may or may not be spatially connected to each other. These communities can be local, national, or international, with specific or broad interests.”[ 16 ]

With regard to the urban context and its complexities, empowerment at the community level, with people's participation in interventions, leads to transparency and accountability. This is further used especially in developing countries where marginalization and informal settlements are more prevalent.[ 17 , 18 ] However, it should be noted that any participation is not considered empowerment and sometimes participations can be created passively, superficially, and partially in the short term or as a means to provide the interests of those in power.[ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]

Community empowerment for health promotion in urban slums still faces challenges. There is not much knowledge about how urban characteristics influence human health. Public health studies focus less on the impact of urban environmental characteristics and often emphasize individual behaviors.[ 23 ]

Since the 1980s, many studies have been conducted on empowerment to improve people's health.[ 24 ] Empowerment in health promotion thinking was legalized by the Ottawa Charter in 1986. However, empowerment in health promotion has always been a controversial concept. According to Laverack and Labonte's study, there have always been tensions in implementing the concept of empowerment and using bottom–up approaches in health promotion.[ 25 ] Woodall et al . (2010) mentioned that there is unclear relationship between empowerment strategies and health promotion and acknowledged the complexity of the empowerment processes in health field.[ 26 ] Hence, it could be predicted that the interventions defined for empowerment in practice are still not professional and standard, and there is a considerable gap between the empowerment evidences and the practice of empowerment.[ 27 ]

These challenges in urban slums are more pronounced due to the complexities of the urban environment. Moreover, unlike rural areas, community empowerment for urban health is still in its infancy and more discussions and studies are needed.[ 17 , 28 ] Corburn (2017) remarks when it discussed “health” in “slum upgrading programs”, it is often limited to a specific disease, exposure to a particular risk factor, and so forth; social determinants of health is less considered. Furthermore, interventions in the slum upgrading, including community empowerment, are less commonly known as an intervention to improve health justice.[ 28 ]

Since the health, urban life, and justice are intertwined issues, therefore, review of various studies in the field of empowerment in urban slums to health promotion can be helpful in making better interventions and strategies to eliminate health injustices in cities and create innovations in this area. Moreover, multiple studies have been conducted on urban management and health in relation to community empowerment. Summary of these studies can be led to a clear understanding of the concept of community empowerment, create the systemic perspectives, comprehensive planning, and standard interventions. In addition, identifying various challenges occurring during the community empowerment process in slums and eliminating these challenges would help to provide a background for improving empowerment implementation processes in slums and health promotion.

Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following questions: What are the challenges related to empowerment of slum residents and promoting their health? What interventions to slum dwellers empowerment are done in the world, in what scopes and what effects? Paying attention to which aspects of community empowerment could result to better planning to improve the health of slum dwellers?

In addition, this study intends to making a step toward bringing the concepts of slum upgrading projects closer to health promotion. Hence, the present study aims to use perspectives, knowledge, and experiences in various scientific articles for identifying, summarizing, and discussing in case of interventions, challenges, actors, scopes, and outcomes in these areas.

Materials and Methods

This study is a narrative review that has been done by searching articles on scientific databases.

Research design

Review studies are conducted to investigate what has already been published and to collect the best available evidence. Narrative reviews are conducted with the aim of identifying and summarizing what has been published, avoiding duplication, and searching for new areas of studies that have not yet been addressed.[ 29 ] The present study reviewed articles related to community empowerment in urban slums. Therefore, narrative review was used.

Search strategy

At the beginning of the article search process, the definitions of slum areas and community empowerment were determined according to the literature review. Then, the keywords were searched according to EMtree, MeSH, and Thesaurus.

Keywords to be searched were defined in two categories as follows:

- ”Slums,” “informal settlement,” “Poverty Area,” “Ghetto,” “shanty town,” “marginal settlement,” and “suburban”

- ”community empowerment,” “health empowerment,” “empowerment,” “health participation,” “health Involvement,” “people Engagement,” “people participation,” “people Involvement,” “community based,” “community resource,” “community Mobilization,” “health enabling,” and “health engagement.”

PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases were used to search the studies. A manual search was also performed separately. Google Scholar was also searched and the first ten pages were examined.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

According to the research question and the definition of community empowerment by the WHO,[ 16 ] the concept of bottom–up approach to health promotion and its difference with the top–down approach is mentioned in Laverack and Labonte's study (2000),[ 25 ] as well as the definition of the UN-HABITAT from slums,[ 3 ] the selection of scientific articles, and definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria were done. It is shown in Table 1 .

There was no time limit for the search operation.

Studies' selection