- Discussions

- Certificates

- Collab Space

- Course Details

- Announcements

In this course, you will learn about the hypothesis-driven approach to problem-solving. This approach originated from academic research and later adopted in management consulting. The course consists of 4 modules that take you through a step-by-step process of solving problems in an effective and timely manner.

Course information

This course is also available in the following languages:

The hypothesis-driven approach is a problem-solving method that is necessary at WHO because the environment around us is changing rapidly. WHO needs a new way of problem-solving to process large amounts of information from different fields and deliver quick, tailored recommendations to meet the needs of Member States. The hypothesis-driven approach produces solutions quickly with continuous refinement throughout the research process.

What you'll learn

- Define the most important questions to address.

- Break down the question into components and develop an issue tree.

- Develop and validate the hypothesis.

- Synthesize findings and support recommendations by presenting evidence in a structured manner.

Who this course is for

- This course is for everyone. Whether your position is in administrative, operations, or technical area of work, you’re sure to run into problems to solve. Problem-solving is a key skill to continue developing and refining—the hypothesis-driven approach will surely be a great addition in your toolbox!

Course contents

Introduction: hypothesis-driven approach to problem solving:, module 1: identify the question:, module 2: develop & validate hypothesis:, module 3: synthesize findings & make recommendations:, enroll me for this course, certificate requirements.

- Gain a Record of Achievement by earning at least 80% of the maximum number of points from all graded assignments.

- Gain a Confirmation of Participation by completing at least 80% of the course material.

Fresh Perspectives

Want to Solve Problems in Public Health? Here's How

I have many loves in family medicine. I love delivering a newborn directly into a mother's arms. I love excisional biopsies of funny looking moles. I love giving someone hope after a chronic disease diagnosis.

What I love most, however, is community-based preventive medicine. As such, I wrangled a contract directly out of residency that is 20 percent population medicine. (Lesson No. 1: Ask for what you want. You might actually get it).

As part of this endeavor, I am pursuing a master's degree in public health. I hope to use this training to make connections in the world of public health policy; to learn how to create, implement, message and evaluate programming; and perhaps to eventually break into creation of, or participation in, policy. I will have some required coursework in, for example, biostatistics and epidemiology, but I will also have myriad electives on topics like environmental public health and behavioral economics.

Throughout the course of my program, I hope to distill the most useful-to-the-family-medicine-doc public health pearls from my classes and pass them along. This post is the first in this series. Thus far, I have taken courses on problem-solving in public health and intro to persuasive communication.

The course on problem-solving in public health taught me two things: a remarkably egalitarian way to run a meeting and a systematic approach to solving problems.

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT)

In this setup for running a meeting, start by imagining a group of eight people. During each session, one of them is the moderator, one a notetaker and one a timekeeper. The moderator's job is to decide how long each part of the session ought to take, and the timekeeper's job is to cut people off once time is reached. The notetaker … takes notes.

Each meeting uses the following series of steps, and as participants get used to the process, they get faster and more efficient.

- Clarify the purpose and goals. The moderator reminds everyone about the specific question or questions for the session, reviews time limits for each ensuing step and allows for adjustments on each of these points.

- Brainstorm solutions. Group members brainstorm answers to the session's central question, a step that can take place before the meeting.

- Share ideas in a round robin. Going around in a circle, each person briefly shares one idea, adding more brief ideas -- avoiding duplicates -- when the circle comes back around until time runs out or all ideas have been voiced. In this manner, no one dominates the discussion and everyone is heard.

- Discuss as a group. Here the group focuses on clarifying, not debating. The goal is to add salient details or reasons for a certain suggestion. This is a time to ask questions rather than make arguments. Some time can also be spent discussing criteria for voting in the next step.

- Rank the suggestions. Each group member ranks the options based on the set criteria -- perhaps voting for their three favorites, using two votes however they want, or casting one vote each -- and the group ends up with two or three leading suggestions.

- Wrap up with conclusions and assignments. Participants are assigned roles or tasks to complete before the next meeting, and a new moderator, timekeeper and notetaker are assigned.

The NGT is delightfully efficient and focused. Moreover, it imposes a thoughtful, respectful and inclusive methodology to traditionally explosive or at least controversial topics. By using this technique, you can assure all members of the group that each of their voices will be heard with equal weight, as will also be the case in the problem-solving process below.

The Problem-solving Process

Usually applied to public health problems, this series of steps offers a framework through which one can approach just about any problem that involves groups of people. Whether your problem is developing a group visit program or decreasing smoking in pregnant women, you can approach the problem with success in this way. Notably, this process works well in combination with the NGT.

- Define the problem. A good problem definition has a specific group, timeframe and outcome of interest. For example, the definition could be, "Childhood obesity rates in the United States among school-aged children have been rising since the 1970s."

- Identify indicators of the problem. If your problem is childhood obesity, your direct indicators would be things like body mass index, waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio. Indirect indicators -- things that give you a clue your endpoint might be happening -- would be rates of childhood hypertension, diabetes or obesity-related sleep apnea. Using the NGT would lead your group to brainstorm as many direct and indirect indicators as possible, then you vote on which ones to track and change.

- Find data for the indicators. Without data, you will have a hard time convincing others to do what you want.

- Identify stakeholders. Find out who cares about the outcome. A meeting held in the NGT style would come out of brainstorming and round robin with a diverse, inclusive and thorough list of potential stakeholders. For childhood obesity, the stakeholders could be parents, students, educators, elected officials, etc. The ranking step would narrow the list to the stakeholders that your group wants to work with.

- Identify key determinants. These are the things that might make the outcome of interest more or less likely. For childhood obesity, these factors might be diet, exercise, dangerous neighborhoods that prevent exercise, food deserts, genes, obesity in parents, television watching, school lunches and poverty.

- Identify intervention strategies. Here is when you brainstorm actions to change the outcome. Some of the group's ideas might be school lunch programs, educational programs for parents, active recess or adjusting food aid programs. All ideas are welcome for discussion and ranking. At the end of the meeting, your group will have decided on an intervention strategy to pursue.

- Identify implementation strategies. It is all well and good to have an intervention, but the next step is to figure out how to get it off the ground. You need to use all the resources you have -- friends in high places, friends in low places, grants, national organizations, local fundraising, city council meetings and more.

- Evaluate. All good interventions need to be evaluated. Be sure to figure out how to do so. Is it working? Is it costing too much? Does it have any unintended benefits or consequences?

I already have used each of these techniques to great effect. By addressing problems in this step-by-step fashion, I find myself suddenly more organized, and you know what that means: more time for more projects!

Just kidding. I get to read books for fun these days and go on long runs. It is amazing.

Stewart Decker, M.D., is a family physician practicing in southern Oregon. He focuses on the intersection of public health and primary care. You can follow him on Twitter at @drstewartdecker.

The opinions and views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent or reflect the opinions and views of the American Academy of Family Physicians. This blog is not intended to provide medical, financial, or legal advice. All comments are moderated and will be removed if they violate our Terms of Use .

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Table of Contents

TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Tools for implementing an evidence-based approach in public health practice, navigate this article, introduction, the need for evidence-based public health, training programs, key elements, putting evidence to work, acknowledgments, author information, julie a. jacobs, mph; ellen jones, phd; barbara a. gabella, msph; bonnie spring, phd; ross c. brownson, phd.

Suggested citation for this article: Jacobs JA, Jones E, Gabella BA, Spring B, Brownson RC. Tools for Implementing an Evidence-Based Approach in Public Health Practice. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:110324. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.110324 .

PEER REVIEWED

Increasing disease rates, limited funding, and the ever-growing scientific basis for intervention demand the use of proven strategies to improve population health. Public health practitioners must be ready to implement an evidence-based approach in their work to meet health goals and sustain necessary resources. We researched easily accessible and time-efficient tools for implementing an evidence-based public health (EBPH) approach to improve population health. Several tools have been developed to meet EBPH needs, including free online resources in the following topic areas: training and planning tools, US health surveillance, policy tracking and surveillance, systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines, economic evaluation, and gray literature. Key elements of EBPH are engaging the community in assessment and decision making; using data and information systems systematically; making decisions on the basis of the best available peer-reviewed evidence (both quantitative and qualitative); applying program-planning frameworks (often based in health-behavior theory); conducting sound evaluation; and disseminating what is learned.

Top of Page

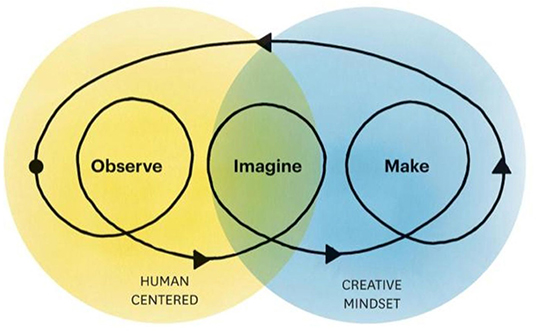

An ever-expanding evidence base, detailing programs and policies that have been scientifically evaluated and proven to work, is available to public health practitioners. The practice of evidence-based public health (EBPH) is an integration of science-based interventions with community preferences for improving population health (1). The concept of EBPH evolved at the same time as discourse on evidence-based practice in the disciplines of medicine, nursing, psychology, and social work. Scholars in these related fields seem to agree that the evidence-based decision-making process integrates 1) best available research evidence, 2) practitioner expertise and other available resources, and 3) the characteristics, needs, values, and preferences of those who will be affected by the intervention (Figure) (2-5).

Figure. Domains that influence evidence-based decision making. Source: Satterfield JM et al (2). [A text description of this figure is also available.]

Public health decision making is a complicated process because of complex inputs and group decision making. Public health evidence often derives from cross-sectional studies and quasi-experimental studies, rather than the so-called “gold standard” of randomized controlled trials often used in clinical medicine. Study designs in public health sometimes lack a comparison group, and the interpretation of study results may have to account for multiple caveats. Public health interventions are seldom a single intervention and often involve large-scale environmental or policy changes that address the needs and balance the preferences of large, often diverse, groups of people.

The formal training of the public health workforce varies more than training in medicine or other clinical disciplines (6). Fewer than half of public health workers have formal training in a public health discipline such as epidemiology or health education (7). No single credential or license certifies a public health practitioner, although voluntary credentialing has begun through the National Board of Public Health Examiners (6). The multidisciplinary approach of public health is often a critical aspect of its successes, but this high level of heterogeneity also means that multiple perspectives must be considered in the decision-making process.

Despite the benefits and efficiencies associated with evidence-based programs or policies, many public health interventions are implemented on the basis of political or media pressures, anecdotal evidence, or “the way it’s always been done” (8,9). Barriers such as lack of funding, skilled personnel, incentives, and time, along with limited buy-in from leadership and elected officials, impede the practice of EBPH (8-12). The wide-scale implementation of EBPH requires not only a workforce that understands and can implement EBPH efficiently but also sustained support from health department leaders, practitioners, and policy makers.

Calls for practitioners to include the concepts of EBPH in their work are increasing as the United States embarks upon the 10-year national agenda for health goals and objectives that constitutes the Healthy People 2020 initiative. The very mission of Healthy People 2020 asks for multisectoral action “to strengthen policies and improve practices that are driven by the best available evidence and knowledge” (13).

Funders, especially federal agencies, often require programs to be evidence-based. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 allocated $650 million to “carry out evidence-based clinical and community-based prevention and wellness strategies . . . that deliver specific, measurable health outcomes that address chronic disease rates” (14). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 mentions “evidence-based” 13 times in Title IV, Prevention of Chronic Disease and Improving Public Health, and will provide $900 million in funding to 75 communities during 5 years through Community Transformation Grants (15).

Federal funding in states, cities, and tribes, and in both urban and rural areas, creates an expectation for EBPH at all levels of practice. Because formal public health training in the workforce is lacking (7), on-the-job training and skills development are needed. The need may be even greater in local health departments, where practitioners may be less aware of and slower to adopt evidence-based guidelines than state practitioners (16) and where training resources may be more limited.

Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals (17) emerged on the basis of recommendations of the Institute of Medicine’s 1988 report The Future of the Public’s Health . Last updated in May 2010, these 74 competencies represent a “set of skills desirable for the broad practice of public health,” and they are compatible with the skills needed for EBPH (3). Elements of state chronic disease programs and competencies endorsed by the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors are also compatible with EBPH (18).

In addition to efforts to establish competencies and certification for individual practitioners, voluntary accreditation for health departments is now offered through the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB). Tribal, state, and local health departments may seek this accreditation to document capacity to deliver the 3 core functions of public health and the Ten Essential Public Health Services (19). One of 12 domains specified by the PHAB as a required level of achievement is “to contribute to and apply the evidence base of public health” (19). This domain emphasizes the importance of the best available evidence and the role of health departments in adding to evidence for promising practices (19).

Several programs have been developed to meet EBPH training needs, including free, online resources (Box 1).

In 1997, the Prevention Research Center in St. Louis (PRC-StL) developed an on-site training course, Evidence-Based Public Health. To date, the course has reached more than 1,250 practitioners and has been replicated by PRC-StL faculty in 14 US states and 6 other countries. The course aims to “train the trainer” to extend the reach of the course and build local capacity (Box 2). Course evaluations are positive, and more than 90% of attendees have indicated they will use course information in their work (20-23). Course slides are available online, and a textbook is in its second edition (8). Using a similar framework, the University of Illinois at Chicago developed an online EBPH course that includes short quizzes and additional resources.

In 2006, with support from National Institutes of Health, experts from the fields of medicine, nursing, public health, social work, psychology, and library sciences formed the Council for Training in Evidence-Based Behavioral Practice. This group produced a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice that facilitates communication and collaboration (Figure) (2,4,5,24) and launched an interactive website to provide web-based training materials and resources to practitioners, researchers, and educators. The EBBP Training Portal, available free with registration, offers 9 modules on both individual and population-based approaches. Users learn how to choose effective interventions, evaluate interventions that are not yet proven, engage in decision making with others, and balance the 3 domains of evidence-based decision making (Figure).

Key elements of EBPH have been summarized (3) as the following:

- Engaging the community in assessment and decision making;

- Using data and information systems systematically;

- Making decisions on the basis of the best available peer-reviewed evidence (both quantitative and qualitative);

- Applying program planning frameworks (often based in health behavior theory);

- Conducting sound evaluation; and

- Disseminating what is learned.

Data for community assessment

As a first step in the EBPH process, a community assessment identifies the health and resource needs, concerns, values, and assets of a community. This assessment allows the intervention (a public health program or policy) to be designed and implemented in a way that increases the likelihood of success and maximizes the benefit to the community. The assessment process engages the community and creates a clear, mutual understanding of where things stand at the outset of the partnership and what should be tracked along the way to determine how an intervention contributed to change.

Public health surveillance is a critical tool for understanding a community’s health issues. Often conducted through national or statewide initiatives, surveillance involves ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of quantitative health data. Various health issues and indicators may be tracked, including deaths, acute illnesses and injuries, chronic illnesses and impairments, birth defects, pregnancy outcomes, risk factors for disease, use of health services, and vaccination coverage. National surveillance sources typically provide state-level data, and county-level data have become more readily available in recent years (Box 1). State health department websites can also be sources of data, particularly for vital statistics and hospital discharge data. Additionally, policy tracking and surveillance systems (Box 1) monitor policy interest and action for various health topics (25).

Other data collection methods can be tailored to describe the particular needs of a community, creating new sources of data rather than relying on existing data. Telephone, mail, online, or face-to-face surveys collect self-reported data from community members. Community audits involve detailed counting of factors such as the number of supermarkets, sidewalks, cigarette butts, or health care facilities. For example, the Active Living Research website (www.activelivingresearch.org) provides a collection of community audit tools designed to assess how built and social environments support physical activity.

Qualitative methods can help create a more complete picture of a community, using words or pictures to describe the “how” and “why” of an issue. Qualitative data collection can take the form of simple observation, interviews, focus groups, photovoice (still or video images that document community conditions), community forums, or listening sessions. Qualitative data analysis involves the verbatim creation of transcripts, the development of data-sorting categories, and iterative sorting and synthesizing of data to develop sets of common concepts or themes (26).

Each of these forms of data collection offers advantages and disadvantages that must be weighed according to the planning team’s expertise, time, and budget. No single source of data is best. Most often data from several sources are needed to fully understand a problem and its best potential solutions. Several planning tools are available (Box 1) to help choose and implement a data collection method.

Selecting evidence

Once health needs are identified through a community assessment, the scientific literature can identify programs and policies that have been effective in addressing those needs. The amount of available evidence can be overwhelming; practitioners can identify the best available evidence by using tools that synthesize, interpret, and evaluate the literature.

Systematic reviews (Box 1) use explicit methods to locate and critically appraise published literature in a specific field or topic area. The products are reports and recommendations that synthesize and summarize the effectiveness of particular interventions, treatments, or services and often include information about their applicability, costs, and implementation barriers. Evidence-based practice guidelines are based on systematic reviews of research-tested interventions and can help practitioners select interventions for implementation. The Guide to Community Preventive Services (the Community Guide ), conducted by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, is one of the most useful sets of reviews for public health interventions (27,28). The Community Guide evaluates evidence related to community or population-based interventions and is intended to complement the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (systematic reviews of clinical preventive services) (29).

Not all populations, settings, and health issues are represented in evidence-based guidelines and systematic reviews. Furthermore, there are many types of evidence (eg, randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, qualitative research), and the best type of evidence depends on the question being asked. Not all types of evidence (eg, qualitative research) are equally represented in reviews and guidelines. To find evidence tailored to their own context, practitioners may need to search resources that contain original data and analysis. Peer-reviewed research articles, conference proceedings, and technical reports can be found in PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed). Maintained by the National Library of Medicine, PubMed is the largest and most widely available bibliographic database; it covers more than 21 million citations in the biomedical literature. This user-friendly site provides tutorials on topics such as the use of Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms. Practitioners can freely access abstracts and some full-text articles; practitioners who do not have journal subscriptions can request reprints from authors directly. Economic evaluations provide powerful evidence for weighing the costs and benefits of an intervention, and the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry tool (Box 1) offers a searchable database and links to PubMed abstracts.

The “gray” literature includes government reports, book chapters, conference proceedings, and other materials not found in PubMed. These sources may provide useful information, although readers should interpret non–peer-reviewed literature carefully. The New York Academy of Medicine produces a bimonthly Grey Literature Report (Box 1), and the US government maintains a website (www.science.gov) that searches the databases and websites of federal agencies in a single query. Internet search engines such as Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com) may also be useful in finding both peer-reviewed articles and gray literature.

Program-planning frameworks

Program-planning frameworks provide structure and organization for the planning process. Commonly used models include PRECEDE-PROCEED (30), Intervention Mapping (31), and Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (Box 1). Public health interventions grounded in health behavior theory often prove to be more effective than those lacking a theoretical base, because these theories conceptualize the mechanisms that underlie behavior change (32,33). Developed as a free resource for public health practitioners, the National Cancer Institute’s guide Theory at a Glance concisely summarizes the most commonly used theories, such as the ecological model, the health belief model, and social cognitive theory, and it uses 2 planning models (PRECEDE-PROCEDE and social marketing) to explain how to incorporate theory in program planning, implementation, and evaluation (34). Logic models are an important planning tool, particularly for incorporating the concepts of health-behavior theories. They visually depict the relationship between program activities and their intended short-term objectives and long-term goals. The first 2 chapters of the Community Tool Box explain how to develop logic models, provide overviews of several program-planning models, and include real-world examples (Box 1).

Evaluation and dissemination

Evaluation answers questions about program needs, implementation, and outcomes (35). Ideally, evaluation begins when a community assessment is initiated and continues across the life of a program to ensure proper implementation. Four basic types of evaluation can achieve program objectives, using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Formative evaluation is conducted before program initiation; the goal is to determine whether an element of the intervention (eg, materials, messages) is feasible, appropriate, and meaningful for the target population (36). Process evaluation assesses the way a program is being implemented, rather than the effectiveness of that program (36) (eg, counting program attendees and examining how they differ from those not attending).

Impact evaluation assesses the extent to which program objectives are being met and may reflect changes in knowledge, attitudes, behavior, or other intermediate outcomes. Ideally, practitioners should use measures that have been tested for validity (the extent to which a measure accurately captures what it is intended to capture) and reliability (the likelihood that the instrument will get the same result time after time) elsewhere. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is the largest telephone health survey in the world, and its website offers a searchable archive of survey questions since the survey’s inception in 1984 (Box 1). New survey questions receive a technical review, cognitive testing, and field testing before inclusion. A 2001 review summarized reliability and validity studies of the BRFSS (37).

Outcome evaluation provides long-term feedback on changes in health status, morbidity, mortality, or quality of life that can be attributed to an intervention. Because it takes so long to observe effects on health outcomes and because changes in these outcomes are influenced by factors outside the scope of the intervention itself, this type of evaluation benefits from more rigorous forms of quantitative evaluation, such as experimental or quasi-experimental rather than observational study designs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Framework for Program Evaluation, developed in 1999, identifies a 6-step process for summarizing and organizing the essential elements of evaluation (38). The related CDC website (Box 1) maintains links to framework-based materials, step-by-step manuals, and other evaluation resources. Within a detailed outline of the CDC framework’s steps, the Community Toolbox also provides tools and examples (Box 1).

After an evaluation, the dissemination of findings is often overlooked, but practitioners have an implied obligation to share results with stakeholders, decision makers, and community members. Often these are people who participated in data collection and can make use of the evaluation findings. Dissemination may take the form of formal written reports, oral presentations, publications in academic journals, or placement of information in newsletters or on websites.

An increasing volume of scientific evidence is now at the fingertips of public health practitioners. Putting this evidence to work can help practitioners meet demands for a systematic approach to public health problem solving that yields measurable outcomes. Practitioners need skills, knowledge, support, and time to implement evidence-based policies and programs. Many tools exist to help efficiently incorporate the best available evidence and strategies into their work. Improvements in population health are most likely when these tools are applied in light of local context, evaluated rigorously, and shared with researchers, practitioners, and other stakeholders.

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; cooperative agreement no. U48/DP001903 from CDC, Prevention Research Centers Program; CDC grant no. 5R18DP001139-02, Improving Public Health Practice Through Translation Research; and National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research contract N01-LM-6-3512, Resources for Training in Evidence-Based Behavioral Practice.

We thank Dr Elizabeth Baker, Dr Kathleen Gillespie, and the late Dr Terry Leet for their roles in developing the PRC-StL EBPH course. We thank the Colorado pilot portfolio teams Erik Aakko, Linda Archer, Gretchen Armijo, Mandy Bakulski, Renee Calanan, Julie Davis, Julie Graves, Indira Gujral, Rebecca Heck, Ashley Juhl, Kyle Legleitner, Flora Martinez, Kristin McDermott, Jessica Osborne, Kerry Thomson, Jason Vahling, and Stephanie Walton. We acknowledge the Mississippi EBPH team, Dr Victor Sutton, Dr Rebecca James, Dr Thomas Dobbs, Cassandra Dove, and State Health Officer Dr Mary Currier, for its commitment to the pilot and implementation of EBPH. We also thank Molly Ferguson, MPH (coordinator), and Drs Ed Mullen, Robin Newhouse, Steve Persell, and Jason Satterfield, members of the Council on Evidence-Based Behavioral Practice.

Corresponding Author: Ross C. Brownson, PhD, Washington University in St. Louis, Kingshighway Building, 660 S Euclid, Campus Box 8109, St. Louis, MO 63110. Telephone: 314-362-9641. E-mail: [email protected] .

Author Affiliations: Julie A. Jacobs, Prevention Research Center in St. Louis, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri; Ellen Jones, School of Health Related Professions, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi; Barbara A. Gabella, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, Colorado; Bonnie Spring, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

- Kohatsu ND, Robinson JG, Torner JC. Evidence-based public health: an evolving concept. Am J Prev Med 2004;27(5):417-21. CrossRef PubMed

- Satterfield JM, Spring B, Brownson RC, Mullen EJ, Newhouse RP, Walker BB, et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Q 2009;87(2):368-90. CrossRef PubMed

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:175-201. CrossRef PubMed

- Spring B, Hitchcock K. Evidence-based practice. In: Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. 4th edition. New York (NY): Wiley; 2009. p. 603-7.

- Spring B, Neville K, Russell SW. Evidence-based behavioral practice. In: Encyclopedia of human behavior. 2nd edition. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2012.

- Gebbie KM. Public health certification. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:203-10. CrossRef PubMed

- Turnock BJ. Public health: what it is and how it works. Sadbury (MA): Jones and Bartlett; 2009.

- Brownson RC, Baker EA, Leet TL, Gillespie KN, True WR. Evidence-based public health. 2nd edition. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Dodson EA, Baker EA, Brownson RC. Use of evidence-based interventions in state health departments: a qualitative assessment of barriers and solutions. J Public Health Manag Pract 2010;16(6):E9-15. PubMed

- Baker EA, Brownson RC, Dreisinger M, McIntosh LD, Karamehic-Muratovic A. Examining the role of training in evidence-based public health: a qualitative study. Health Promot Pract 2009;10(3):342-8. CrossRef PubMed

- Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, Kreuter MW, et al. Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: what contributes to dissemination by state health departments. Am J Prev Med 2007;33(1 Suppl):S66-73. CrossRef PubMed

- Jacobs JA, Dodson EA, Baker EA, Deshpande AD, Brownson RC. Barriers to evidence-based decision making in public health: a national survey of chronic disease practitioners. Public Health Rep 2010;125(5):736-42. PubMed

- Healthy People 2020 framework: the vision, mission and goals of Healthy People 2020. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/Consortium/HP2020Framework.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub L No 111-5, 123 Stat 233 (2009).

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub L No 111-148, 124 Stat 119 (2010).

- Brownson RC, Ballew P, Brown KL, Elliott MB, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, et al. The effect of disseminating evidence-based interventions that promote physical activity to health departments. Am J Public Health 2007;97(10):1900-7. CrossRef PubMed

- Core competencies for public health professionals. Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Pages/Core_Public_Health_Competencies.aspx. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- Slonim A, Wheeler FC, Quinlan KM, Smith SM. Designing competencies for chronic disease practice. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7(2). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/mar/08_0114.htm. Accessed March 7, 2012. PubMed

- Standards and measures. Public Health Accreditation Board. http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-process/public-health-department-standards-and-measures/. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- Brownson RC, Diem G, Grabauskas V, Legetic B, Poternkina R, Shatchkute A, et al. Training practitioners in evidence-based chronic disease prevention for global health. Promot Educ 2007;14(3):159-63. PubMed

- O’Neall MA, Brownson RC. Teaching evidence-based public health to public health practitioners. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15(7):540-4. CrossRef PubMed

- Dreisinger M, Leet TL, Baker EA, Gillespie KN, Haas B, Brownson RC. Improving the public health workforce: evaluation of a training course to enhance evidence-based decision making. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008;14(2):138-43. PubMed

- Franks AL, Brownson RC, Bryant C, Brown KM, Hooker SP, Pluto DM, et al. Prevention Research Centers: contributions to updating the public health workforce through training. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(2). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/apr/04_0139.htm. Accessed March 7, 2012. PubMed

- Newhouse RP, Spring B. Interdisciplinary evidence-based practice: moving from silos to synergy. Nurs Outlook 2010;58(6):309-17. CrossRef PubMed

- Chriqui JF, O’Connor JC, Chaloupka FJ. What gets measured, gets changed: evaluating law and policy for maximum impact. J Law Med Ethics 2011;39 (Suppl 1)21-6. CrossRef PubMed

- Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P. The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2006.

- Mullen PD, Ramirez G. The promise and pitfalls of systematic reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:81-102. CrossRef PubMed

- Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW, editors. The guide to community preventive services: what works to promote health? New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2005.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/. Accessed March 9, 2012.

- Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning: an educational and ecological approach. 4th edition. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; 2004.

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernandez ME. Planning health promotion programs: an Intervention Mapping approach. 3rd edition. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2011.

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in the development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:399-418. CrossRef PubMed

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th edition. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2008.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2005. (NIH publication 05-3896). http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/theory.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- Shadish WR. The common threads in program evaluation. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3(1). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/jan/05_0166.htm. Accessed March 7, 2012. PubMed

- Thompson N, Kegler M, Holtgrave D. Program evaluation. In: Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, editors. Research methods in health promotion. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2006. p. 199-225.

- Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed 2001;(46 Suppl 1):S3-42. PubMed

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR Recomm Rep 1999;(48 RR-11):1-40. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4811a1.htm. Accessed March 7, 2012. PubMed

File Formats Help:

- PCD podcasts

- PCD on Facebook

- Page last reviewed: July 26, 2012

- Page last updated: July 26, 2012

- Content source: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

- Using this Site

- Contact CDC

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2022

A framework of evidence-based decision-making in health system management: a best-fit framework synthesis

- Tahereh Shafaghat 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Peivand Bastani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0412-0267 1 , 3 na1 ,

- Mohammad Hasan Imani Nasab 4 ,

- Mohammad Amin Bahrami 1 ,

- Mahsa Roozrokh Arshadi Montazer 5 ,

- Mohammad Kazem Rahimi Zarchi 2 &

- Sisira Edirippulige 6

Archives of Public Health volume 80 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

6 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scientific evidence is the basis for improving public health; decision-making without sufficient attention to evidence may lead to unpleasant consequences. Despite efforts to create comprehensive guidelines and models for evidence-based decision-making (EBDM), there isn`t any to make the best decisions concerning scarce resources and unlimited needs . The present study aimed to develop a comprehensive applied framework for EBDM.

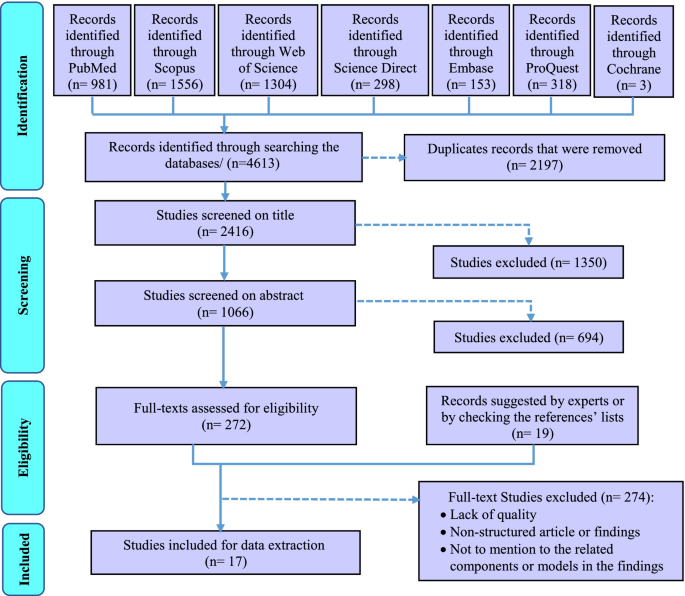

This was a Best-Fit Framework (BFF) synthesis conducted in 2020. A comprehensive systematic review was done via six main databases including PUBMED, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, EMBASE, and ProQuest using related keywords. After the evidence quality appraisal, data were extracted and analyzed via thematic analysis. Results of the thematic analysis and the concepts generated by the research team were then synthesized to achieve the best-fit framework applying Carroll et al. (2013) approach.

Four thousand six hundred thirteen studies were retrieved, and due to the full-text screening of the studies, 17 final articles were selected for extracting the components and steps of EBDM in Health System Management (HSM). After collecting, synthesizing, and categorizing key information, the framework of EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general scopes. These comprised inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating, which included 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps.

Conclusions

The present framework provided a comprehensive guideline that can be well adapted for implementing EBDM in health systems and related organizations especially in underdeveloped and developing countries where there is usually a lag in updating and applying evidence in their decision-making process. In addition, this framework by providing a complete, well-detailed, and the sequential process can be tested in the organizational decision-making process by developed countries to improve their EBDM cycle.

Peer Review reports

Globally, there is a growing interest in using the research evidence in public health policy-making [ 1 , 2 ]. Public health systems are diverse and complex, and health policymakers face many challenges in developing and implementing policies and programs that are required to be efficient [ 1 , 3 ]. The use of scientific evidence is considered to be an effective approach in the decision-making process [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Due to the lack of sufficient resources, evidence-based decision-making ( EBDM) is regarded as a way to optimize costs and prevent wastes [ 6 ]. At the same time, the direct consequence of ignoring evidence is poorer health for the community [ 7 ].

Evidence suggests that health systems often fail to exploit research evidence properly, leading to inefficiencies, death or reduced quality of citizens’ lives, and a decline in productivity [ 8 ]. Decision-making in the health sector without sufficient attention to evidence may lead to a lack of effectiveness, efficiency, and fairness in health systems [ 9 ]. Instead, the advantages of EBDM include adopting cost-effective interventions, making optimal use of limited resources, increasing customer satisfaction, minimizing harm to individuals and society, achieving better health outcomes for individuals and society [ 10 , 11 ], as well as increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of public health programs [ 12 ].

Using the evidence in health systems’ policymaking is a considerable challenging issue that many developed and developing countries are facing nowadays. This is particularly important in the latter, where their health systems are in a rapid transition [ 13 ]. For instance, although in 2012, a study in European Union countries showed that health policymakers rarely had necessary structures, processes, and tools to exploit research evidence in the policy cycle [ 14 ], the condition can be worse among the developing and the underdeveloped ones. For example, evidence-based policy-making in developing countries like those located in the Middle East can have more significant impacts [ 15 , 16 ]. In such countries resources are generally scarce, so the policymakers' awareness of research evidence becomes more important [ 17 ]. In general, low and middle-income countries have fewer resources to deal with health issues and need quality evidence for efficient use of these resources [ 7 ].

Since the use of EBDM is fraught with the dilemma of most pressing needs and having the least capacity for implementation especially in developing countries [ 16 ], efforts have been made to create more comprehensive guidelines for EBDM in healthcare settings, in recent years [ 18 ]. Stakeholders are significantly interested in supporting evidence-based projects that can quickly prioritize funding allocated to health sectors to ensure the effective use of their financial resources [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. However, it is unlikely that the implementation of EBDM in Health System Management (HSM) will follow the evidence-based medicine model [ 10 , 22 ]. On the other hand, the capacity of organizations to facilitate evidence utilization is complex and not well understood [ 22 ], and the EBDM process is not usually institutionalized within the organizational processes [ 10 ]. A study in 2005 found that few organizations support the use of research evidence in health-related decisions, globally [ 23 ]. Weis et al. (2012) also reported there is insufficient information on EBDM in local health sectors [ 12 ]. In general, it can be emphasized that relatively few organizations hold themselves accountable for using research evidence in developing health policies [ 24 ]. To the best of our knowledge, there isn`t any comprehensive global and practical model developed for EBDM in health systems/organizations management. Accordingly, the present study aimed to develop a comprehensive framework for EBDM in health system management. It can shed the light on policymakers to access a detailed practical model and enable them to apply the model in actual conditions.

This was a Best Fit Framework (BFF) synthesis conducted in 2020 to develop a comprehensive framework for EBDM in HSM. Such a framework synthesis is achieved as a combination of the relevant framework, theory, or conceptual models and particularly is applied for developing a priori framework based on deductive reasoning [ 25 ]. The BFF approach is appropriate to create conceptual models to describe or express the decisions and behaviors of individuals and groups in a particular domain. This is distinct from other methods of evidence synthesis because it employs a systematic approach to create an initial framework for synthesis based on existing frameworks, models, or theories [ 25 ] for identifying and adapting theories systematically with the rapid synthesis of evidence [ 25 , 26 ]. The initial framework can be derived from a relatively well-known model in the target field, or be formed by the integration of several existing models. The initial framework is then reduced to its key components that have shaped its concepts [ 25 ]. Indeed, the initial framework considers as the basis and it can be rebuilt, extended, or reduced based on its dimensions [ 26 ]. New concepts also emerge based on the researchers' interpretation of the evidence and ongoing comparisons of these concepts across studies [ 25 ]. This approach of synthesis possesses both positivist and interpretative perspectives; it provides the simultaneous use of the well-known strengths of both framework and evidence synthesis [ 27 ].

In order to achieve this aim the following methodological steps were conducted as follows:

Searching and selection of studies

In this step, we aimed to look for the relevant models and frameworks related to evidence-based decision-making in health systems management. The main research question was “what is the best framework for EBDM in health systems?” after defining the research question, the researchers searched for published studies on EBDM in HSM in different scientific databases with relevant keywords and constraints as inclusion and exclusion criteria from 01.01.2000 to 12.31.2020 (Table 1 ).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were determined as the studies that identify the components or develop a model or framework of EBDM in health organization in the form of original or review articles or dissertations, which were published in English and had a full text. The studies like book reviews, opinion articles, and commentaries that lacked a specific framework for conducting our review were excluded. During the search phase of the study, we attempted as much as possible to access studies that were not included in the search process or gray literature by reviewing the references lists of the retrieved studies or by contacting the authors of the articles or experts and querying them, as well as manually searching the related sites (Fig. 1 ).

The PRISMA flowchart for selection of the studies in scoping review

Quality appraisal

The quality of the obtained studies was investigated using three tools for assessing the quality of various types of studies considering types and methods of the final include studies in systematic review. These tools were including Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) for assessing the quality of qualitative researches [ 28 ], Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) [ 29 ], and The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers [ 30 ] (Table 3- Appendix ).

Data extraction

After searching the studies from all databases and removing duplicates, the studies were independently reviewed and screened by two members (TS and MRAM) of the research team in three phases by the title, abstract, and then the full text of the articles. At each stage of the study, the final decision to enter the study to the next stage was based on agreement and, in case of disagreement, the opinion of the third person from the research team was asked (PB). Mendeley reference manager software was used to systematically search and screen relevant studies. The data from the included studies were extracted based on the study questions and accordingly, a form of the studies’ profile including the author's name, publication year, country, study title, type of study, and its conditions were prepared in Microsoft Excel software (Table 4- Appendix ).

Synthesis and the conceptual model

In this step, a thematic analysis approach was applied to extract and analyze the data. For this purpose, first, the texts of the selected studies were read several times, and the initial qualitative codes or thematic concepts, according to the determined keywords and based on the research question, were found and labeled. Then these initial thematic codes were reviewed to achieve the final codes and they were integrated and categorized to achieve the final main themes and sub-themes, eventually. The main and the sub-themes are representative of the main and sub-steps of EBDM. At the last stage of the synthesis, the thematic analysis was finalized with 8 main themes and all the main and the sub-themes were tabulated (Table 5- Appendix ).

Creation of a new conceptual framework

For BFF synthesis in the present study, we compared the existing models and tried to find a model that fits the best. Three related models that appeared to be relatively well-suited to the purpose of this study to provide a complete, comprehensive, and practical EBDM model in HSM were found. According to the BFF instruction in Carroll et al. (2013) study [ 25 ], we decided to use all three models as the basis for the best fit because any of those models were not complete enough and we could give no one an advantage over others. Consequently, the initial model or the BFF basis was formed and the related thematic codes were classified according to the category of this basis as the main themes/steps of EBDM in HSM (Table 5- Appendix ). Then, the additional founded thematic codes were added and incorporated to this basis as the other main steps and the sub-steps of the EBDM in HSM according to the research team and some details in the form of sub-steps were added by the research team to complete the synthesized framework. Eventually, a comprehensive practical framework consisting of 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps was created with the potentiality of applying and implementing EDBM in HSM that we categorized them into four main phases (Table 6- Appendix ).

Testing the synthesis: comparison with the a priori models, dissonance and sensitivity

In order to assess the differences between the priori framework and the new conceptual framework, the authors tried to ask some experts’ opinions about the validity of the synthesized results. The group of experts has included eight specialists in the field of health system management or health policy-making. These experts have been chosen considering their previous research or experience in evidence-based decision/policy making performance/management (Table 2 ). This panel lasted in two three-hour sessions. The finalized themes and sub-themes (Table 6- Appendix ) and the new generated framework (Fig. 3 ) were provided to them before each session so that they could think and then in each meeting they discussed them. Finally, all the synthesized themes and sub-themes resulted were reviewed and confirmed by the experts.

Ethical considerations

To prevent bias, two individuals carried out all stages of the study such as screening, data extraction, and data analysis. The overall research project related to this manuscript was approved by the medical ethics conceal of the research deputy of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences with approval number IR.SUMS.REC.1396–01-07–14184, too.

The initial search across six electronic databases and the Cochrane library yielded 4613 studies. After removing duplicates, 2416 studies were assessed based on their titles. According to the abstract screening of the 1066 studies that remained after removing the irrelevant titles, 291 studies were selected and were entered into the full-text screening phase. Due to full-text screening of the studies, 17 final studies were selected for extracting the components and steps of EBDM in HSM (Fig. 1 ). The features of these studies were summarized in Table 4- Appendix (see supplementary data). Furthermore, according to the quality appraisal of the included studies, the majority of them had an acceptable level of quality. These results have been shown in Table 3- Appendix .

Results of the thematic analysis of the evidence (Table 5- Appendix ) along with the concepts proposed and added by the research team according to the focus-group discussion of the experts were shown in Table 6- Appendix . Accordingly, the main steps and related sub-steps of the EBDM process in HSM were defined and categorized.

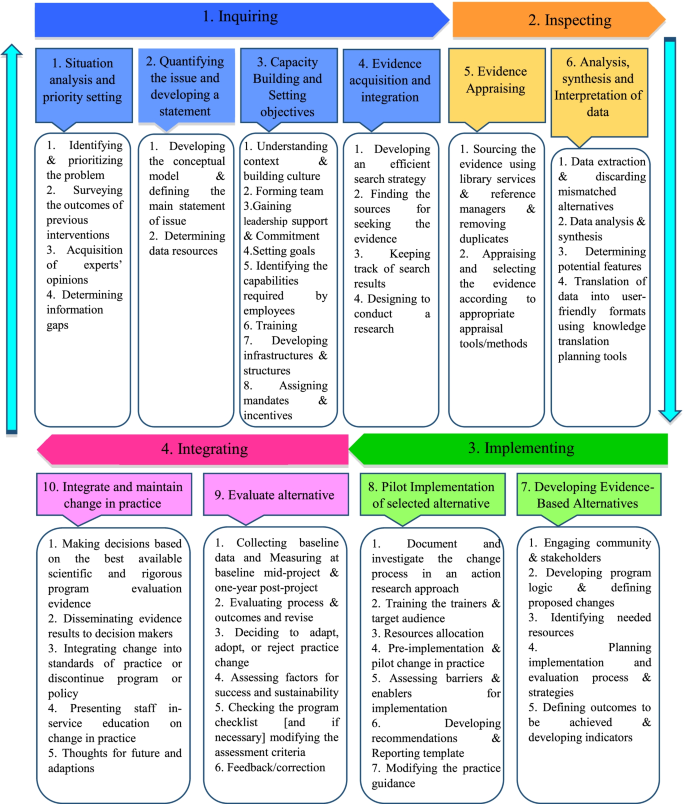

After collecting, synthesizing, and categorizing thematic concepts, incorporating them with the initial models, and adding the additional main steps and sub-steps to the basic models, the final synthesized framework as a best-fit framework for EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general phases of inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating and 10 main steps (Fig. 2 ). For better illustration, this framework with all the main steps and 47 sub-steps has been shown in Fig. 3 , completely.

The final synthesized framework of evidence-based decision-making in health system management

The main steps and sub-steps of the framework of EBDM in health system management

In the present study, a comprehensive framework for EBDM in HSM was developed. This model has different distinguishing characteristics than the formers. First of all, this is a comprehensive practical model that combined the strengths and the crucial components of the limited number of previous models; second, the model includes more details and complementary steps and sub-steps for full implementation of EBDM in health organizations and finally, the model is benefitted from a cyclic nature that has a priority than the linear models. Concerning the differences between the present framework and other previous models in this field, it must be said that most of the previous models related to EBDM were presented in the scope of medicine (that they were excluded from our SR according to the study objectives and exclusion criteria). A significant number of those models were proposed for the scope of public health and evidence-based practice, and only a limited number of them focused exactly on the scope of management and policy/decision making in health system organizations.

Given that the designed model is a comprehensive 10-step model, it can be used in some way at all levels of the health system and even in different countries. However, there will be a difference here, given that this framework provides a practical guide and a comprehensive guideline for applying evidence-based decision-making approach in health systems organizations, at each level of the health system in each country, this management approach can be applied depending on their existing infrastructure and the processes that are already underway (such as capacity building, planning, data collection, etc.), and at the same time, with a general guide, they can provide other infrastructure as well as the prerequisites and processes needed to make this approach much more possible and applicable.

It is true that evidence-based management is different from evidence-based medicine and even more challenging (due to lack of relevant data, greater sensitivity in data collection and their accuracy, lack of consistency and lack of transparency in the implementation of evidence-based decision-making in management rather than evidence-based medicine, etc.). Still, the general framework provided in this article can be used to help organizations that really want to act and move forward through this approach.

Furthermore, based on the findings, most of the previous studies only referred to some parts of the components and steps of the EBDM in health organizations and neglected the other parts or they were not sufficiently comprehensive [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Most of the previous models did not mention the necessary sub-steps, tools, and practical details for accurate and complete implementation of the EBDM, which causes the organizations that want to use these models, will be confused and cannot fully implement and complete the EBDM cycle. Among the studies that have provided a partly complete model than the other studies, were the studies by Brownson (2009), Yost (2014), and Janati (2018) [ 3 , 41 , 42 ]. Consequently, the combination of these three studies has been used as the initial framework for the best-fit synthesis in the present study.

Likewise, the models presented by Brownson (2009) and Janati (2018) were only limited to the six or seven key steps of the EBDM process, and they did not mention the details required for doing in each step, too [ 3 , 4 , 42 ]. Also, the model presented in the study of Janati (2018) was linear, and the relationships between the EBDM components were not well considered [ 42 , 43 ]; however, the model presented in this study was recursive. Also, in Yost's study (2014), despite the 7 main steps of EBDM and some details of each of the steps, the proposed process was not schematically drawn in the form of a framework and therefore the relationships between steps and sub-steps were not clear [ 41 ]. According to what was discussed, the best-fit framework makes the possibility of concentrating the fragmented models to a comprehensive one that can be fully applied and evaluated by the health systems policymakers and managers.

In the present study, the framework of EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general scopes of inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating including 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps. These scopes were discussed as follows:

In the first step, “situation analysis and priority setting”, the most frequently cited sub-step was identifying and prioritizing the problem. Accordingly, Falzer (2009), emphasized the importance of identifying the decision-making conditions and the relevant institutions and determining their dependencies as the first steps of EBDM [ 44 ]. Aas (2012) has also cited the assessment of individuals and problem status and problem-finding as the first steps of EBDM [ 34 ]. Moreover, the necessity of identifying the existing situation and issues and prioritizing them has been emphasized as the initial steps in most management models such as environmental analysis in strategic planning [ 45 ].

Despite considering the opinions and experience of experts and managers as one of the important sources of evidence for decision-making [ 42 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ], many studies did not mention this sub-step in the EBDM framework. Hence, the present authors added the acquisition of experts’ opinions as a sub-step of the first step because of its important role in achieving a comprehensive view of the overall situation.

In the second step, “quantifying the issue and developing a statement”, “Developing the conceptual model for the issue” was more addressed [ 37 , 41 , 47 ]. In addition, the authors to complete this step added the fourth sub-step, “Defining the main statement of issue”. This is because that most of the problems in health settings may have a similar value for managers and decision-makers and quantifying them can be used as a criterion for more attention or selecting the problem as the main issue to solve.

The third step, “Capacity building and setting objectives”, was not seen in many other included studies as a main step in EBDM, however, the present authors include this as a main step because without considering the appropriate objectives and preparing necessary capacities and infrastructures, entering to the next steps may become problematic. Moreover, in numerous studies, factors such as knowledge and skills of human resources, training, and the availability of the essential structures and infrastructures have been identified as facilitators of EBDM [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ]. According to this justification, they are included in the present framework as sub-steps of the third step.

Considering the third step and based on the knowledge extracted from the previous studies, the three sub-steps of “understanding context and Building Culture” [ 56 , 57 ], “gaining the support and commitment of leaders” [ 39 , 57 , 58 ], and “identifying the capabilities required by employees and their skills weaknesses” [ 58 , 59 , 60 ] were the most important sub-steps in this step of EBDM framework. In this regard, Dobrow (2004) has also stated that the two essential components of any EBDM are the evidence and context of its use [ 32 ]. Furthermore, Isfeedvajani (2018) stated that to overcome barriers and persuade hospital managers and committees to apply evidence-based management and decision-making, first and foremost, creating and promoting a culture of "learning through research" was important [ 61 ].

The present findings showed that in the fourth main step, “evidence acquisition and integration”, the most important sub-step was “finding the sources for seeking the evidence” [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 60 , 62 , 63 ]. Concerning the sources for the use of evidence in decision-making in HSM, studies have cited numerous sources, most notably scientific and specialized evidence such as research, articles, academic reports, published texts, books, and clinical guidelines [ 39 , 64 , 65 ]. After scientific evidence, using the opinions and experiences of experts, colleagues, and managers [ 42 , 46 , 49 , 66 ] as well as the use of census and local level data [ 49 , 66 , 67 ], and other sources such as financial [ 67 ], political [ 42 , 49 ] and evaluations [ 49 , 68 ] data were cited.

The fifth step of the present framework, “evidence appraising”, was emphasized by previous literature; for instance, Pierson (2012) pointed to the use of library services in EBDM [ 69 ]. Appraising and selecting the evidence according to appropriate appraisal tools/methods was cited the most. International and local evidence is confirmed that ignoring these criteria can lead to serious faults in the process of decision and policy-making [ 70 , 71 ].

Furthermore, the sixth step, “analysis, synthesis, and interpretation of data”, was mentioned in many included studies [ 36 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 57 , 59 , 72 ]. This step emphasized the role of analysis and synthesis of data in the process of generation applied and useful information. It is obvious that the local interpretation according to different contexts may lead to achieving such kind of knowledge that can be used as a basis for local EBDM in HSM.

Implementing

The third scope consisted of the seventh and eighth steps of the EBDM process in HSM. In the seventh step, “developing evidence-based alternatives”, the issue of involving stakeholders in decision-making and subsequently, planning to design and implementation of the process and evaluation strategies had been focused by the previous studies [ 58 , 60 , 62 , 63 , 73 ]. Studies by Belay (2009) and Armstrong (2014) had also emphasized the need to use stakeholder and public opinion as well as local and demographic data in decision-making [ 49 , 67 ].

“Pilot-implementation of selected alternatives” was the eighth step of the framework. Some key sub-steps of this step were resources allocation [ 58 ], Pre-implementation and pilot change in practice and assessing barriers and enablers for implementation [ 40 ] that indicated the significance of testing the strategies in a pilot stage as a pre- requisition of implementing the whole alternatives. It is obvious that without attention to the pilot stage, adverse and unpleasant outcomes may occur that their correction process imposes many financial, organizational, and human costs on the originations. In addition, a study explained that one of the strategies of the decision-makers to measure the feasibility of the policy options was piloting them, which had a higher chance of being approved by the policymakers. Also, pilot implementation in smaller scales has been recommended in public health in cases of lack of sufficient evidence [ 74 ].

Integrating

This last scope consists of the ninth and tenth steps. The main sub-step of the ninth step, “evaluating alternatives”, was to evaluating process and outcomes and revise. After a successful implementation of the pilot, this step can be assured that the probable outcomes may be achieved and this evaluation will help the decision and policymakers to control the outcomes, effectively. Also, it impacts the whole target program and proposes some correcting plans through an accurate feedback process, too. Pagoto (2007) explained that a facilitator for EBDM would be an efficient and user-friendly system to assess utilization, outcomes, and perceived benefits [ 55 ].

Also, the tenth step, “integrating and maintaining change in practice”, was not considered as a major step in previous models, too, while it is important to maintain and sustain positive changes in organizational performance. In this regard, Ward (2011) also suggested several steps to maintain and sustain the widespread changes in the organization, including increasing the urgency and speed of action, forming a team, getting the right vision, negotiating for buy-in, empowerment, short-term success, not giving up and help to make a change stick [ 35 ]. Finally, the most important sub-steps that could be mentioned in this step were the dissemination of evidence results to decision-makers and the integration of changes made to existing standards and performance guidelines. Liang (2012) had also emphasized the importance of translating existing evidence into useful practices as well as disseminating them [ 47 ]. In addition, the final sub-step, “feedback and feedforward towards the EBDM framework”, was explained by the authors to complete the framework.

Some previous findings showed that about half and two-thirds of organizations do not regularly collect related data about the use of evidence, and they do not systematically evaluate the usefulness or impact of evidence use on interventions and decisions [ 75 ]. The results of a study conducted on healthcare managers at the various levels of an Iranian largest medical university showed that the status of EBDM is not appropriate. This problem was more evident among physicians who have been appointed as managers and who have less managerial and systemic attitudes [ 76 ]. Such studies, by concerning the shortcomings of current models for EBDM in HSM or even lack of a suitable and usable one, have confirmed the necessity of developing a comprehensive framework or model as a practical guide in this field. Consequently, existing and presenting such a framework can help to institutionalize the concept of EBDM in health organizations.

In contrast, results of Lavis study (2008) on organizations that supported the use of research evidence in decision-making reported that more than half of the organizations (especially institutions of health technology assessment agencies) may use the evidence in their process of decision-making [ 75 ], so applying the present framework for these organizations can be recommended, too.

Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of access to some studies (especially gray literature) related to the subject in question that we tried to access them by manual searching and asking from some articles’ authors and experts. In addition, most of the existing studies on EBDM were limited to examining and presenting results on influencing, facilitating, or hindering factors or they only mentioned a few components in this area. Consequently, we tried to search for studies from various databases and carefully review and screen them to make sure that we did not lose any relevant data and thematic code. Also, instead of one model, we used four existing models as a basis in the BFF synthesis so that we can finally, by adding additional codes and themes obtained from other studies as well as expert opinions, provide a comprehensive model taking into account all the required steps and details. Also, the framework developed in this study is a complete conceptual model made by BFF synthesis; however, it may need some localization, according to the status and structure of each health system, for applying it.

The present framework provides a comprehensive guideline that can be well adapted for implementing EBDM in health systems and organizations especially in underdeveloped and developing countries where there is usually a lag in updating and applying evidence in their decision-making process. In addition, this framework by providing a complete, well-detailed, sequential and practical process including 10 steps and 56 sub-steps that did not exist in the incomplete related models, can be tested in the organizational decision-making process or managerial tasks by developed countries to improve their EBDM cycle, too.

Availability of data and materials

All data in a form of data extraction tables are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Evidence-based decision-making

Health System Management

Best-Fit Framework

Rychetnik L, Bauman A, Laws R, King L, Rissel C, Nutbeam D, et al. Translating research for evidence-based public health: Key concepts and future directions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1187–92.

Article Google Scholar

Nutbeam D, Boxall AM. What influences the transfer of research into health policy and practice? Observations from England and Australia. Public Health. 2008;122(8):747–53.

Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-Based Public Health: A Fundamental Concept for Public Health Practice. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 2009;30(1):175–201. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100134 .

Brownson RC, Gurney JG, Land GH. Evidence-based decision making in public health. J Public Heal Manag Pract [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2018 May 26];5(5):86–97. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yxRgAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA133&dq=+criteria+OR+health+%22evidence+based+decision+making%22&ots=hiqVNQtF24&sig=jms9GsBfw6gz1cN2FQXzCBZvmMQ

McGinnis JM. ‘Does Proof Matter? Why Strong Evidence Sometimes Yields Weak Action.’ Am J Heal Promot. 2001;15(5):391–396. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.391 .

Majdzadeh R, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Gholami J, Ahghari S, R. M, et al. Strengthening evidence-based decision-making: Is it possible without improving health system stewardship? Health Policy Plan [Internet]. 2012 Sep 1 [cited 2018 May 15];27(6):499–504. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr072

WHO EIPNET. Using evidence and innovation to strengthen policy and practice. 2008.

Ellen ME, Léon G, Bouchard G, Lavis JN, Ouimet M, Grimshaw JM. What supports do health system organizations have in place to facilitate evidence-informed decision-making? A qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):84.

Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Lewin S, Fretheim A. What is evidence-informed policymaking? Health Res Policy Sys. 2009;7:1–7.

Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, Anderson L, Moore L, Petticrew M, et al. Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: Intervention design and implementation plan. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2013;8(1):1. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84885076767&doi=10.1186%2F1748-5908-8-121&partnerID=40&md5=dddaf4029205c63877a3e6ecf28f7762

Waters E, Armstrong R, Swinburn B, Moore L, Dobbins M, Anderson L, et al. An exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial of knowledge translation strategies to support evidence-informed decision-making in local governments (The KT4LG study). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2011;11(1):34. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/34

Imani-Nasab MH, Yazdizadeh B, Salehi M, Seyedin H, Majdzadeh R. Validity and reliability of the Evidence Utilisation in Policymaking Measurement Tool (EUPMT). Heal Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):1–11.

El-Jardali F, Lavis JN, Ataya N, Jamal D, Ammar W, Raouf S. Use of health systems evidence by policymakers in eastern mediterranean countries: Views, practices, and contextual influences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):200.

Ettelt S, Mays N. Health services research in Europe and its use for informing policy. J Health Serv Res Policy [Internet]. 2011 Jul 29 [cited 2019 Jun 29];16(2_suppl):48–60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011004

Sutcliffe S. Evidence-Based Policymaking: What is it? How does it work? What relevance for developing countries? 2005.

Campbell DM, Redman S, Jorm L, Cooke M, Zwi AB, Rychetnik L. Increasing the use of evidence in health policy: Practice and views of policy makers and researchers. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2009;6(1):1–11.

WHO. Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE) for Policy in African Health Systems. 2007:1–72.

Health Public Accreditation Board. Public Health Accreditation Board STANDARDS : AN OVERVIEW. 2012.

Riley WJ, Bender K, Lownik E. Public health department accreditation implementation: Transforming public health department performance. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):237–42.

Liebman JB. Building on Recent Advances in Evidence-Based Policymaking. 2013:36. Available from: http://www.americaachieves.org/9F42769C-3A65-4CCB-8466-E7BFD835CFE7/FinalDownload/DownloadId-0AB31816953C7B8AFBD2D15DFD39D5A8/9F42769C-3A65-4CCB-8466-E7BFD835CFE7/docs/RFA/THP_Liebman.pdf

Jacobs J a, Jones E, Gabella B a, Spring B, Brownson C. Tools for Implementing an Evidence-Based Approach in Public Health Practice. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2012;9(1):1–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.110324

Kothari A, Edwards N, Hamel N, Judd M. Is research working for you? validating a tool to examine the capacity of health organizations to use research. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–9.

Oxman AD, Bjørndal A, Becerra-Posada F, Gibson M, Block MAG, Haines A, et al. A framework for mandatory impact evaluation to ensure well informed public policy decisions. Lancet. 2010;375(9712):427–31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61251-4

Oxman AD, Vandvik PO, Lavis JN, Fretheim A, Lewin S. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 2: Improving how your organisation support the use of research evidence to inform policymaking. Chinese J Evidence-Based Med. 2010;10(3):247–54.

Google Scholar

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J. “ Best fit ” framework synthesis : refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1 Available from: BMC Medical Research Methodology.

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of “ best fit ” framework synthesis : A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:29.

Barnett-page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research : a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 9. 2009;59:1–26.

Public Health Resource Unit. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) making sense of evidence;10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Public Health. 2006.

Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4(1):2–8.

Hong Q, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. User guide. McGill [Internet]. 2018;1–11. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf%0Ahttp://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/

Titler MG. The Iowa Model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. 2001.

Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur REG. Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2004;58(1):207–17. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953603001667