- Foundations

- Goal Oriented

- Self-Assessment

- Study Skills

- Dunn and Dunn Learning Style

- Felder and Silverman Index of Learning Styles

- Honey-Mumford

- Kolb Learning Style

- MBTI Learning Styles

- Multiple Intelligences

- Book 1: Calais

- Book 2: Lemosa

- Book 3: Damien

- Book 4: Celestina

- Book 5: Lillin

- Rachel’s 8

- MBTI Learning Styles: A Practical Approach

- Securing Your Tent

- Philosophy of Education

- Guided Learning

- Learning Logs

- Organize Learning

- Reflective Learning

- Youth & Children

- Non-fiction

- Teaching Resources

Problem Solving through Reflective Practice

Reflective practice progresses through several steps. The practitioner first identifies a problem followed by the observation and analysis stage. Ostermann & Kottk amp (2004) identify this stage as “the most critical and complex of the four” (p. 28) stages. This stage entails the necessity of not only gathering information about the problem without tainting it with personal judgment but also analyzing the dilemma as it is compared from the current situation to the desired goal . The third stage, abstract re-conceptualization requires the practitioner to investigate new solutions and resources which address the root of the dilemma. Lastly, experimentation enters as the new strategies are utilized in changing behaviors. York-Barr et al. (2005) suggests that these steps are not linear, nor are they circular. Each step is interconnected

Using a learning journal aids in the learning process. Click on image.

with the others.

This practice can be utilized through recording each step and later reviewing what was learned. It allows educators to provide the example for the students in a continuous learning environment of progression as they develop skills to be more proficient at teaching and more skilled at learning. It is simply the experiential model by which educators learn most effectively.

These are some of my favorite sources for a reflective practice and problem solving using reflective practice.

Click on image.

Osterman, K. & Kottkamp, R. (2004). Reflective practice for educators: Professional development to improve student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

York-Barr, J., Sommers, W., Ghere, G. & Monthie, J. (2005). Reflective practice to improve schools: An action guide for educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

By Tracy Harrington-Atkinson

Tracy Harrington-Atkinson, mother of six, lives in the Midwest with her husband. She is a teacher, having taught elementary school to higher education, holding degrees in elementary education, a master’s in higher education and continued on to a PhD in curriculum design. She has published several titles, including Calais: The Annals of the Hidden , Lemosa: The Annals of the Hidden, Book Two, Rachel’s 8 and Securing Your Tent . She is currently working on a non-fiction text exploring the attributes of self-directed learners: The Five Characteristics of Self-directed Learners.

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel by clicking here .

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Reflection within Deep Learning

- Relating Teaching Theory to Practice

- Reflective Leader

- Using a Learning Journal

Categories:

Comments are closed

- VARK Strengths and Weaknesses

- MBTI INFJ (Introversion, Intuition, Feeling, Judging) Learning Styles

- MBTI ENFP (Extraversion, Intuition, Feeling, Perceiving) Learning Styles

- MBTI ENFJ (Extraversion, Intuition, Feeling, Judging) Learning Styles

- MBTI INFP (Introversion, Intuition, Feeling, Perceiving) Learning Styles

- Fleming VARK Theory

- MBTI ISTP (Introversion, Sensing, Thinking, Perceiving) Learning Styles

- Reading - A Four-Step Process

How to Improve Teaching and Learning Through Reflective Practice

- brightwheel

- Staff development

Think back on the past week of your life. What went well? What didn’t? If you could go back in time, are there things you would change to avoid making certain mistakes? What actions would you repeat to experience the same successes or moments of joy?

It might seem silly, but this act of thinking back on past experiences to learn from them and make better decisions in the future is a process called reflective action. And for early childhood educators, continually engaging in reflective action can have a profound impact, both on how you teach and how your children learn.

In this article, we'll discuss the benefits of reflective practice and ways to incorporate this into your routine.

What is reflective practice?

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one’s actions to engage in a process of continuous learning. For educators, this means reviewing lessons and identifying ways in which those lessons were, or were not, successful. Ultimately, this process can help ensure that all children are learning as effectively as possible.

There are four steps to the reflective cycle:

It might seem obvious, but executing your lesson plans is the most important part of the reflective cycle. These experiences and their outcomes will set a baseline for you to reflect upon and help you identify areas where you can improve.

Self-assessment

The key to self-assessment is to understand the effect your teaching has had on your children’s learning. It’s not a matter of if the lesson is “good” or “bad.” Instead, it’s about identifying which aspects of the lesson you can improve to meet your children’s current learning needs.

Considering new methods

Do children need more hands-on experience with the current material? Can you incorporate more play into your teaching? Are there ways to enhance the learning environment to make the lessons more impactful? Consider all possibilities, and don’t be afraid to try something new if you think it will improve the quality of your teaching.

Putting ideas into practice

Once you’ve identified new methods, you can start to incorporate them into your lesson plans. Remember, reflective practice is a cycle, and any new ideas you use in your teaching can be reviewed and improved upon later. It’s about continuously trying new things and learning what works best for young children.

Use a software like brightwheel's classroom management feature to aid in your reflective practice. Document and track children's progress in the app, record observations and notes, and quickly adjust learning activities to keep your classroom engaged.

The importance of reflection in teaching

The world of education is constantly evolving, and educators must continually improve or revise their teaching practices to meet the increasingly diverse needs of their children. In other words, reflective practice helps to ensure that all children learn most effectively, as teaching is tailored to their learning needs. But educators and children can also benefit from reflection in a number of other ways.

Promotes professional growth

Studies show that engaging in reflective practice can help educators better understand their own personal strengths and weaknesses. By identifying goals and noting the results of lessons, you can find new ways to adjust your teaching methods, modify routines, and improve strategies when addressing your children.

Fosters innovation

Reflective practice and innovation go hand-in-hand. By taking the time to review your teaching methods and children’s engagement with the lessons, you can find new and creative ways to address challenges. Consider incorporating more play, taking the learning outside , or finding ways for children to have more hands-on experiences.

Cultivates better teacher-child relationships

Reflective teaching practices give educators the opportunity to consider the unique learning needs of every child they teach. Incorporating more individualized learning techniques into your lessons can help children better understand the material and help you foster better communication with them.

Enhances problem-solving

Learning to solve problems and meet challenges effectively and efficiently is incredibly important in the classroom. Reflective practice gives educators the time to identify solutions for the challenges they are facing. For instance, a teacher can use previous teaching experience (their own or those borrowed from a colleague) to find new ways to motivate children who face learning problems. By drawing on knowledge and past experiences, you can become more resourceful and confident when faced with new challenges.

Reflective practice examples

While the benefits of reflective practice seem too good to pass up, for busy educators, finding time to sit and reflect after a long day might seem impossible. Fortunately, reflection doesn’t require a lengthy meditation period—in fact, it doesn’t even have to be done alone. Try these helpful techniques when you want to reflect on your lessons.

Start a journal

Maintaining an ongoing journal of your teaching techniques and outcomes is the simplest way to reflect on your lessons. This doesn’t mean you have to spend an hour a day writing. Just five minutes a day, or a few times a week, will help you think back on your time spent teaching and answer questions like:

- “What went well?”

- “What could I have done differently?”

- “What can I try next time?”

Record your lessons

Use your phone (while keeping it out of sight) to record your lessons . This can be a video of the entire class or just audio of your instruction. Recording your lessons can allow you to fully reflect on all aspects of your teaching, from gauging the clarity of your instructions to identifying which children are engaging the most or least.

Reflect in the moment

Another simple and quick way to use technology to your advantage is by leaving yourself real-time feedback on your phone or tablet. This can be a voice memo or a few lines written in a notes app. Recording quick summaries of your lessons in real-time ensures that you don’t forget any important aspects of the lessons and that you can more accurately assess what went well and what didn’t.

Ask for suggestions

Reflective practice doesn’t always have to be done alone. Talk to other educators about their experiences and ways they’ve improved their own lessons. Getting advice from colleagues can help you reflect more objectively and spot areas of improvement you might not notice on your own.

Observe your peers

If you have the time to sit in on your fellow educators’ lessons, observing their methods can give you insight into the strengths and areas of improvement of your own teaching strategies. The goal here is not to identify what they are doing wrong but rather to create open communication and professional development among you and your peers.

How to become a more reflective teacher

There is no such thing as the perfect teacher. Educators are always growing and evolving as children’s needs change. Reflection is a critical part of your professional development as a teacher because it allows you to put yourself inside the learning experience and better identify areas where you can grow. But it’s not always easy.

Being objective with yourself (or having others be objective for you) takes time and doesn’t always lead to positive findings. But putting in the time to be reflective gives you the opportunity to make sense of the learning happening in your classroom. To ensure that your reflection is beneficial, consider a few simple rules:

- Be honest with yourself

- Be open to new ideas and methods

- Reflect on all aspects of your teaching

- Avoid giving yourself unnecessary restrictions on areas to review

- Don’t just reflect—put your ideas into action

- Keep the needs of your children at the forefront of your reflection

- Don’t just focus on the negative; give yourself credit for the things you are doing right too

The bottom line

Reflective practice is a key part of teaching and learning. And it doesn’t have to be hard or time-consuming. Develop reflective habits that work best for you, whether it’s jotting down notes in a journal or watching your lessons on video. By staying consistent, you’ll ensure that your lessons are timely, engaging, and effective for your children.

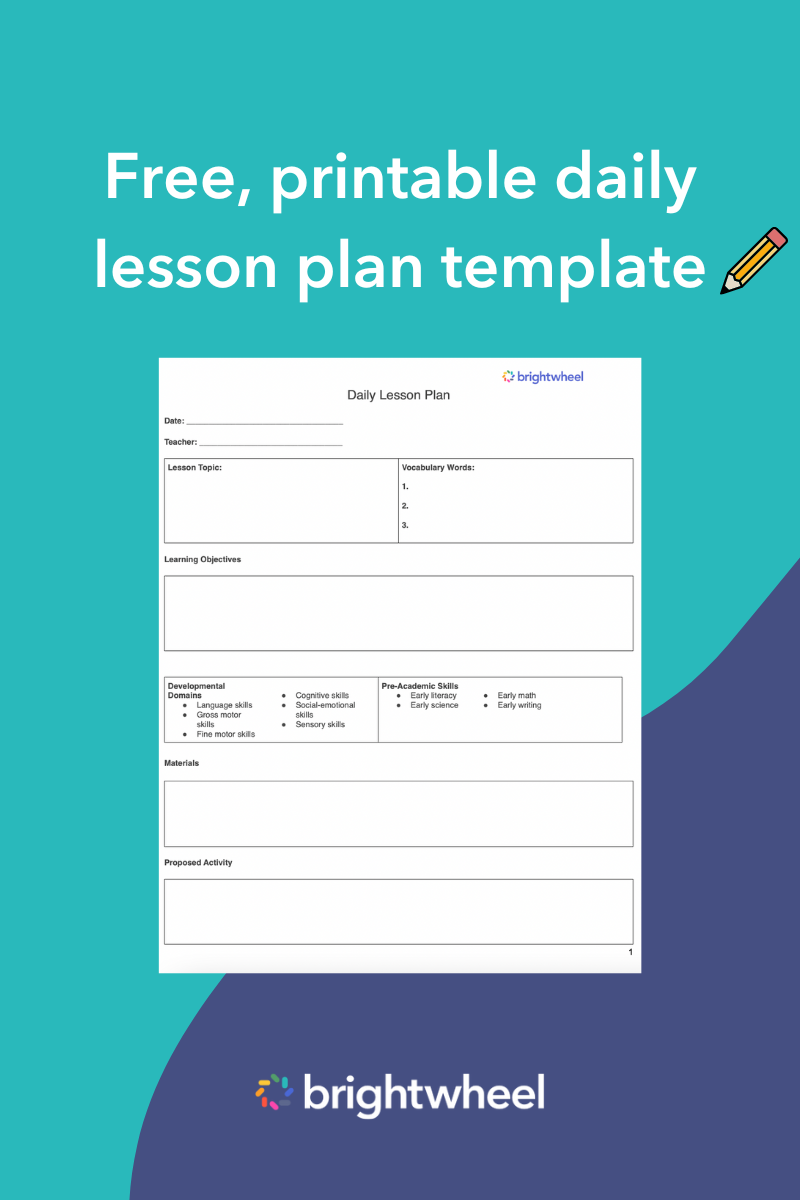

Daily Lesson Plan Template

A free, printable template for creating lesson plans.

Subscribe to the brightwheel blog

Recent Posts

- Navigating Childcare Grants and Other Funding Resources in Michigan April 19, 2024

- 75 Staff Appreciation Ideas April 19, 2024

- 50 Creative Ways to Celebrate Teacher Appreciation Week April 19, 2024

- Navigating Childcare Grants and Other Funding Resources in New Jersey April 19, 2024

- How to Create a Preschool Newsletter: A Guide for Teachers April 18, 2024

Posts by Tag

- Running a business (180)

- Child development (164)

- Curriculum (83)

- Staff development (47)

- Family engagement (40)

- Financial health (32)

- COVID-19 (30)

- Technology (27)

- Small business funding (19)

- Family communications (15)

- Staff retention (15)

- ECE career growth (13)

- For Parents (10)

- Diversity and inclusion (9)

- Enrollment (7)

- Staff appreciation (7)

- Marketing (6)

- Public policy (6)

- Staff hiring (5)

- ECE current events (4)

- Family retention (4)

- Salary guides (4)

- Leadership (2)

- Faculty & Staff

Teaching problem solving

Strategies for teaching problem solving apply across disciplines and instructional contexts. First, introduce the problem and explain how people in your discipline generally make sense of the given information. Then, explain how to apply these approaches to solve the problem.

Introducing the problem

Explaining how people in your discipline understand and interpret these types of problems can help students develop the skills they need to understand the problem (and find a solution). After introducing how you would go about solving a problem, you could then ask students to:

- frame the problem in their own words

- define key terms and concepts

- determine statements that accurately represent the givens of a problem

- identify analogous problems

- determine what information is needed to solve the problem

Working on solutions

In the solution phase, one develops and then implements a coherent plan for solving the problem. As you help students with this phase, you might ask them to:

- identify the general model or procedure they have in mind for solving the problem

- set sub-goals for solving the problem

- identify necessary operations and steps

- draw conclusions

- carry out necessary operations

You can help students tackle a problem effectively by asking them to:

- systematically explain each step and its rationale

- explain how they would approach solving the problem

- help you solve the problem by posing questions at key points in the process

- work together in small groups (3 to 5 students) to solve the problem and then have the solution presented to the rest of the class (either by you or by a student in the group)

In all cases, the more you get the students to articulate their own understandings of the problem and potential solutions, the more you can help them develop their expertise in approaching problems in your discipline.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Conceptualizing the complexity of reflective practice in education

Misrah mohamed.

1 Centre for Enhancement of Learning and Teaching, University of West London, London, United Kingdom

Radzuwan Ab Rashid

2 Faculty of Languages and Communication, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Terengganu, Malaysia

Marwan Harb Alqaryouti

3 Department of English Language, Literature and Translation, Zarqa University, Zarqa, Jordan

In higher education, reflective practice has become a dynamic, participatory, and cyclical process that contributes to educators’ professional development and personal growth. While it is now a prominent part of educators, many still find it challenging to apply the concept for it carries diverse meaning for different people in different contexts. This article attempts to (re)conceptualize the complexity of reflective practice in an educational context. Scholars in this field have taken different approaches to reflective practice, but all these approaches consist of four main components in common: (i) reflecting; (ii) planning for future action; (iii) acting; and (iv) evaluating the outcomes. We extend the existing literature by proposing a model which integrates these four components with three key aspects of reflection: problem-solving, action orientation, and criticality. The novelty of this model lies within its alignment of the three key aspects with different levels of criticality in a comprehensive framework with detailed descriptors provided. The model and its descriptors are useful in guiding individuals who directly or indirectly involve in critical reflection, especially educators, in appraising their levels of criticality and consequently engage in a meaningful reflection.

Introduction

In the field of education, reflective practice has been recognized as an important aspect in continuing professional development. Through reflective practice, we can identify the factors, the consequences of and the assumptions that underlie our actions. In higher education, reflective practice has become a dynamic, participatory, and cyclical process ( Ai et al., 2017 ) that contributes to educators’ professional development and personal growth ( McAlpine et al., 2004 ; De Geest et al., 2011 ; Davies, 2012 ; Marshall, 2019 ). It enables professional judgment ( Day, 1999 ) and fosters professional competence through planning, implementing and improving performance by rethinking about strengths, weaknesses and specific learning needs ( Huda and Teh, 2018 ; Cirocki and Widodo, 2019 ; Zahid and Khanam, 2019 ; Seyed Abolghasem et al., 2020 ; Huynh, 2022 ). Without routinely engaging in reflective practice, it is unlikely that educators will comprehend the effects of their motivations, expectations and experiences upon their practice ( Lubbe and Botha, 2020 ). Thus, reflective practice becomes an important tool that helps educators to explore and articulate lived experiences, current experience, and newly created knowledge ( Osterman and Kottkamp, 2004 ). Educators are continually recommended to apply reflective practice in getting a better understanding of what they know and do as they develop their knowledge of practice ( Loughran, 2002 ; Lubbe and Botha, 2020 ). In fact, reflective practice is now a prominent part of training for trainee teachers (e.g., Shek et al., 2021 ; Childs and Hillier, 2022 ; Ruffinelli et al., 2022 ) because it can help future teachers review their own practices and develop relevant skills where necessary.

Despite the wide acceptance of the concept of reflective practice, the notion of ‘reflection’ in itself is still broad. Our review of literature reveals that reflection is a term that carries diverse meaning. For some, “it simply means thinking about something” or “just thinking” (e.g., Loughran, 2002 , p. 33), whereas for others, it is a well-defined practice with very specific purpose, meaning and action (e.g., Dewey, 1933 ; Schön, 1983 ; Grimmett and Erickson, 1988 ; Richardson, 1990 ; Loughran, 2002 ; Spalding et al., 2002 ; Paterson and Chapman, 2013 ). We found many interesting interpretations made along this continuum, but we believe the most appealing that rings true for most people is that reflection is useful and informing in the development and understanding of teaching and learning (e.g., Seitova, 2019 ; McGarr, 2021 ; Huynh, 2022 ). This, however, is not enough to signify the characteristics of reflection. Consequently, many teachers find it hard to understand the concept and engage in reflective practice for their professional development ( Bennett-Levy and Lee, 2014 ; Burt and Morgan, 2014 ; Haarhoff et al., 2015 ; Marshall, 2019 ; Huynh, 2022 ; Knassmüller, 2022 ; Kovacs and Corrie, 2022 ). For example, some teachers from higher arts education have considered reflective practice as antithetical to practical learning ( Guillaumier, 2016 ; Georgii-Hemming et al., 2020 ) as they often frame explicit reflection as assessed reflective writing, which is “disconnected from the embodied and non-verbal dimensions of making and reflecting on art” ( Treacy & Gaunt, 2021 , p. 488). The lack of understanding of the concept has created disengagement in reflection and reflective practice ( Aliakbari and Adibpour, 2018 ; Huynh, 2022 ; Knassmüller, 2022 ) which resulted in poor insight and performance in practice ( Davies, 2012 ). To overcome this, educators should foster their understanding of the reflective practice, so they not only can reap its benefits for their own learning, but also facilitate and maximize reflective skills within their students.

In this paper, we aim to provide an overview of the concepts of effective reflective practice and present the value of reflective practice that can help teachers to professionally develop. First, we situate our conceptual understanding of reflective practice by discussing key issues surrounding reflection and reflective practice. Second, we present the key aspects of effective reflective practice. Finally, based on our discussion of key aspects of effective reflective practice, we introduce a revised model of reflective practice that may serve as a guide for educators to professionally develop. Although the model is but one approach, we believe it holds promise for others grappling as we are with efforts to encourage reflective practices among educators who find reflection in and on their practices a complex concept.

Key issues in reflective practice

The concepts of “reflection,” “reflective thought,” and “reflective thinking” have been discussed since 1904, when John Dewey claimed that an individual with good ethical values would treat professional actions as experimental and reflect upon their actions and consequences. Dewey defined reflection as the “active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends” ( Dewey, 1904 , p. 10). His basic notion is that reflection is an active, deliberative cognitive process involving a sequence of interconnected ideas that include the underlying beliefs and knowledge of an individual.

Following Dewey’s original work and its subsequent interpretation, four key thought-provoking issues are worthy of discussion: reflective thinking versus reflective action; time of reflection; reflection and problem solving; and critical reflection. The first concern is whether reflection is a process limited to thinking about action or also bound up in action ( Grant and Zeichner, 1984 ; Noffke and Brennan, 1988 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ). There seems to be broad agreement that reflection is a form of thought process ( Ross, 1989 ; McNamara, 1990 ; Sparks-Langer et al., 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ) even though some do not lead to action. However, Dewey’s first mention of “reflective action” suggests he was concerned with the implementation of solutions after thinking through problems. Therefore, reflective practice, in our view, is bound up with the constant, careful consideration of practice in the light of knowledge and beliefs. The complete cycle of reflection should then lead to clear, modified action and this needs to be distinguished from routine action derived from impulse, tradition, or authority ( Noffke and Brennan, 1988 ; Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ).

The time frames within which reflection takes place, needs to be addressed—relatively immediate and short term, or rather more extended and systematic. Schön (1983) holds that professionals should learn to frame and reframe the problems they often face and after trying out various interpretations, modify their actions as a result. He proposes “reflection-in-action,” which requires conscious thinking and modification, simultaneously reflecting and doing almost immediately. Similar to this concept is “technical reflection,” involving thinking about competencies or skills and their effectiveness and occurs almost immediately after an implementation and can then lead to changes in subsequent action ( Cruickshank, 1985 ; Killen, 1989 ). While the notion of immediacy in reflective practice seems appropriate, some argue that the process should involve conscious detachment from an activity after a distinct period of contemplation ( Boud et al., 1985 ; Buchmann, 1990 ). This is because reflection demands contemplating rational and moral practices in order to make reasoned judgments about better ways to act. Reflective practice often involves looking back at actions from a distance, after they have taken place ( Schön, 1983 ; Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ; Smith and Lovat, 1991 ). While immediate and extended “versions” of reflections are both recognized, we suppose no one is better than another. However, we believe that being able to think consciously about what is happening and respond instantaneously makes for a higher level of reflective competence.

The third issue identified from our literature review is whether reflection by its very nature is problem orientated ( Calderhead, 1989 ; Adler, 1991 ). Reflection is widely agreed to be a thought process concerned with finding solutions to real problems ( Calderhead, 1989 ; Adler, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ; Loughran, 2002 ; Choy and Oo, 2012 ). However, it is unclear whether solving problems is an inherent characteristic of reflection. For example, Schön’s (1983) reflection-in-action involves thought processing simultaneously with a group event taking place, and reflection-on-action refers to a debriefing process after an event. Both aims to develop insights into what took place—the aims, the difficulties during the event or experience and better ways to act. While focusing on reacting to practical events, these practices do not often intend to find solutions to specific practical problems. Instead, reflective practitioners are invited to think about a new set of actions from if not wider, at least different perspectives.

The fourth issue in the literature revolves around “critical reflection.” Very often critical reflection is concerned with how individuals consciously consider their actions from within wider historical, cultural and political beliefs when framing practical problems for which to seek solutions ( Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ; Choy and Oo, 2012 ). It is a measure of a person’s acceptance of a particular ideology, its assumptions and epistemology, when critical reflection is developed within reflective practice ( McNamara, 1990 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ). It implies the individual locates any analysis of personal action within her/his wider socio-historical and political-cultural contexts ( Noffke and Brennan, 1988 ; Smith and Lovat, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ). While this makes sense, critical reflection in the literature appears to loosely refer to an individual’s constructive self-criticism of their actions to improve in future ( Calderhead, 1989 ), not a consideration of personal actions with both moral and ethical criteria ( Senge, 1990 ; Adler, 1991 ; Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ). Thus, we see a need to define critical reflection in line with the key characteristics of reflective practice.

Effective reflective practice

Reflecting on the issues discussed above, we conclude that for reflective practice to be effective, it requires three key aspects: problem-solving, critical reflection and action-orientation. However, these aspects of reflective practice have different levels of complexity and meaning.

Problem-solving

A problem is unlikely to be acted upon if it is not viewed as a problem. Thus, it is crucial to problematize things during reflection, to see concerns that require improvement. This is not a simple process as people’s ability to perceive things as problems is related to their previous experiences. For example, a senior teacher with years of teaching experience and a rapport with the students s/he teaches will be immediately aware of students experiencing difficulties with current teaching strategies. However, a junior teacher whose experience is restricted to a three-month placement and who has met students only a few times will be less aware. The differences in experience also influence the way people interpret problems. For example, the senior teacher may believe his/her teaching strategy is at fault if half the students cannot complete the given tasks. A junior teacher with only 2 weeks teaching experience may deduce that the students were not interested in the topic, and that is why they cannot complete the tasks given. This example illustrates the range of ways a problem can be perceived and the advantages of developing the ability to frame and reframe a problem ( Schön, 1983 ). Problems can also be perceived differently depending on one’s moral and cultural beliefs, and social, ethical and/or political values ( Aliakbari and Adibpour, 2018 ; Karnieli-Miller, 2020 ). This could be extended to other factors such as institutional, educational and political system ( Aliakbari and Adibpour, 2018 ).

Framing and reframing a problem through reflection can influence the practice of subsequent actions ( Loughran, 2002 ; Arms Almengor, 2018 ; Treacy and Gaunt, 2021 ). In the example above, the junior teacher attributes the problem to the students’ attitude, which gives her/him little to no incentive to address the situation. This is an ineffective reflective practice because it has little impact on the problem. Thus, we believe it is crucial for individuals to not only recognize problems but to examine their practices ( Loughran, 2002 ; Arms Almengor, 2018 ; Zahid and Khanam, 2019 ) through a different lens to their existing perspectives so solutions can be developed and acted upon. This requires critical reflection.

Critical reflection

We believe it is the critical aspect of reflection that makes reflective practice effective and more complex, formulated by various scholars as different stages of reflection. Zeichner and Liston (1987) proposed three stages of reflection similar to those described by Van Manen (1977) . They suggested the first stage was “technical reflection” on how far the means to achieve certain end goals were effective, without criticism or modification. In the second stage, “practical reflection,” both the means and the ends are examined, with the assumptions compared to the actual outcomes. This level of reflection recognizes that meanings are embedded in and negotiated through language, hence are not absolute. The final stage, “critical reflection,” combined with the previous two, considers both the moral and ethical criteria of the judgments about professional activity ( Senge, 1990 ; Adler, 1991 ; Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ).

While the three stages above capture the complexity of reflection, individuals will only reach an effective level of reflection when they are able to be self-critical in their judgments and reasoning and can expand their thinking based on new evidence. This aligns with Ross’ (1989) five stages of reflection (see Table 1 ). In her five stages of reflection, individuals do not arrive at the level of critical reflection until they get to stages 4 and 5, which require them to contextualize their knowledge and integrate the new evidence before making any judgments or modification ( Van Gyn, 1996 ).

Five stages of reflections ( Ross, 1989 ).

Action-orientation

We believe it is important that any reflections should be acted upon. Looking at the types and stages of reflection discussed earlier, there is a clear indication that reflective practice is a cyclical process ( Kolb, 1984 ; Richards and Lockhart, 2005 ; Taggart and Wilson, 2005 ; Clarke, 2008 ; Pollard et al., 2014 ; Babaei and Abednia, 2016 ; Ratminingsih et al., 2018 ; Oo and Habók, 2020 ). Richards and Lockhart (2005) suggest this cyclical process comprises planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. This is further developed by Hulsman et al. (2009) who believe that the cyclical process not only involves action and observation, but also analysis, presentation and feedback. In the education field, reflective practice is also considered cyclical ( Clarke, 2008 ; Pollard et al., 2014 ; Kennedy-Clark et al., 2018 ) because educators plan, observe, evaluate, and revise their teaching practice continuously ( Pollard et al., 2014 ). This process can be done through a constant systematic self-evaluation cycle ( Ratminingsih et al., 2018 ) which involves a written analysis or an open discussion with colleagues.

From the descriptions above, it seems that cyclical reflective practice entails identifying a problem, exploring its root cause, modifying action plans based on reasoning and evidence, executing and evaluating the new action and its results. Within this cyclical process, we consider action as a deliberate change is the key to effective reflective practice, especially in the field of education. Reflection that is action-oriented is an ongoing process which refers to how educators prepare and teach and the methods they employ. Educators move from one teaching stage to the next while gaining the knowledge through experience of the importance/relevance of the chosen methods in the classroom situation ( Oo and Habók, 2020 ).

While reflection is an invisible cognitive process, it is not altogether intuitive ( Plessner et al., 2011 ). Individuals, especially those lacking experience, may lack adequate intuition ( Greenhalgh, 2002 ). To achieve a certain level of reflection, they need guidance and this can be done with others either in groups ( Gibbs, 1988 ; Grant et al., 2017 ) or through one-on-one feedback ( Karnieli-Miller, 2020 ). The others, who can be peers or mentors, can help provide different perspectives in exploring alternative interpretations and behaviors. Having said this, reflecting with others may not always feasible as it often requires investment of time and energy from others ( Karnieli-Miller, 2020 ). Therefore, teachers must learn how to scaffold their own underlying values, attitudes, thoughts, and emotions, and critically challenge and evaluate assumptions of everyday practice on their own. With this in mind, we have created a cyclical process of reflective practice which may help in individual reflections. It captures the three key aspects of reflective practice discussed above. This model may help teachers having a range of experience enhance their competence through different focus and levels of reflection (see Figure 1 ).

Cyclical reflective practice model capturing problem-solving, action-oriented critical reflection.

The model illustrates the cyclical process with three stages: reflection, modification and action. At the reflection stage, a problem and the root of the problem is explored so it can be framed as it is/was and then reframed to identify a possible solution. This is followed by a modification for change based on the reasoning and evidence explored during the reflection stage. Finally, the action stage involves executing action (an event), followed by the reflection stage to begin another cycle and continue the process.

As presented earlier, it is crucial for individuals to be able to frame and reframe problems through a different lens to their existing perspectives so solutions can be developed and acted upon. Thus, the model above expands Tsangaridou and O’Sullivan’s (1994) framework by adding together the element of problematizing. The current revised framework highlights the four focuses of reflection; technical addresses the management or procedural aspects of teaching practice; situational addresses the context of teaching; sensitizing involves reflecting upon the social, moral, ethical or political concerns of teaching; and problematizing concerns the framing and reframing of the problem identified within the teaching context. Considering the different levels of critical reflection, we extend the four focuses of reflection to three different levels of critical reflection: descriptive involves reflection of the four focuses without reasoning or criticism; descriptive with rationale involves reflection of the four focuses with reasoning; and descriptive with rationale and evaluation involves reflection of the four focuses with both reasoning and criticism (see Table 2 ). Each of these levels requires different degrees of critical analysis and competence to extract information from actions and experiences. Overall, level three best captures effective critical reflection for each focus.

A framework of reflection.

This revised model that we proposed encompasses different levels of critical reflection and is action-oriented. There is also a clear link to problem-solving which requires framing and reframing problems to accurately identify them, which may influence the value and effectiveness of the actions that follow ( Loughran, 2002 ). Thus, this model may help people, especially those with lack experience to recognize the different aspects of reflection so they can make better assessments of and modifications to their procedures ( Ross, 1989 ; Van Gyn, 1996 ).

The meaning of reflection and reflective practice is not clear cut. However, we believe a reflective educator should cultivate a set of responses to how their teaching operates in practice. As Dewey (1933) suggested, educators must find time to reflect on their activity, knowledge, and experience so that they can develop and more effectively serve their community, nurturing each student’s learning. However, this does not always happen. Some educators do not reflect on their own practice because they find the concept of reflective practice difficult to put into practice for their professional development ( Jay and Johnson, 2002 ; Bennett-Levy and Lee, 2014 ; Burt and Morgan, 2014 ; Haarhoff et al., 2015 ; Marshall, 2019 ; Huynh, 2022 ).

Our review of the literature indicates that reflective practice is a complex process and some scholars argue that it should involve active thinking that is more bound up with action ( Grant and Zeichner, 1984 ; Noffke and Brennan, 1988 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ). Thus, the complete cycle of reflective practice needs to be distinguished from routine action which may stem from impulse, tradition, or authority ( Noffke and Brennan, 1988 ; Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ). In addition, some also argue that reflective practice involves the conscious detachment from an activity followed by deliberation ( Boud et al., 1985 ; Buchmann, 1990 ), and therefore reflective practice should not occur immediately after action. Although this is acceptable, we believe that instant reflection and modification for future action can be a good indicator of an individual’s level of reflective competence.

Reflective practice is an active process that requires individuals to make the tacit explicit. Thus, it is crucial to acknowledge that reflection is, by its very nature, problem-centered ( Calderhead, 1989 ; Adler, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ; Loughran, 2002 ; Choy and Oo, 2012 ). Only with this in mind can individuals frame and reframe their actions or experiences to discover specific solutions. Reflective practice is also complex, requiring critical appraisal and consideration of various aspects of thought processes. Individuals must play close attention to what they do, evaluate what works and what does not work on a personal, practical and professional level ( Gore and Zeichner, 1991 ; Hatton and Smith, 1995 ; Choy and Oo, 2012 ). However, some would consider critical reflection as no more than constructive self-criticism of one’s actions with a view to improve ( Calderhead, 1989 ). Consequently, scholars have taken different approaches to reflective practice in teaching areas that include critical thinking (e.g., Ross, 1989 ; Tsangaridou and O’Sullivan, 1994 ; Loughran, 2002 ). These approaches had four components in common: reflecting (observing actions, reviewing, recollecting), planning for future action (thinking and considering), acting (practice, experience, and learning), and evaluating (interpreting and assessing outcomes). We propose a model that embraces these four sub-areas and three key aspects of reflection: problem-solving, action orientation and critical reflection. We align these key aspects with level of criticality in a framework with detailed descriptors. It is hoped that these elements, combined together, demonstrate the complexities of reflection in a better, clearer way so that those struggling to adopt reflective practice will now be able to do so without much difficulty.

Author contributions

MM contributed to conception and written the first draft of the manuscript. RR contributed in the discussion of the topic. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Adler S. (1991). The reflective practitioner and the curriculum of teacher education . J. Educ. Teach. 17 , 139–150. doi: 10.1080/0260747910170203 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ai A., Al-Shamrani S., Almufti A. (2017). Secondary school science teachers’ views about their reflective practices . J. Teach. Educ. Sustainability 19 , 43–53. doi: 10.1515/jtes-2017-0003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aliakbari M., Adibpour M. (2018). Reflective EFL education in Iran: existing situation and teachers’ perceived fundamental challenges . Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 18 , 1–16. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2018.77.7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arms Almengor R. (2018). Reflective practice and mediator learning: a current review . Conflict Resolut. Q. 36 , 21–38. doi: 10.1002/crq.21219 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babaei M., Abednia A. (2016). Reflective teaching and self-efficacy beliefs: exploring relationships in the context of teaching EFL in Iran . Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 41 , 1–27. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2016v41n9.1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bennett-Levy J., Lee N. K. (2014). Self-practice and self-reflection in cognitive behaviour therapy training: what factors influence trainees’ engagement and experience of benefit? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 42 , 48–64. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812000781, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boud D., Keogh M., Walker D. (1985). Reflection. Turning experience into learning . London: Kogan Page. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buchmann M. (1990). Beyond the lonely, choosing will: professional development in teacher thinking . Teach. Coll. Rec. 91 :508. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burt E., Morgan P. (2014). Barriers to systematic reflective practice as perceived by UKCC level 1 and level 2 qualified Rugby union coaches . Reflective Pract. 15 , 468–480. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2014.900016 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calderhead J. (1989). Reflective teaching and teacher education . Teach. Teach. Educ. 5 , 43–51. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(89)90018-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Childs A., Hillier J. (2022). “ Developing the practice of teacher educators: the role of practical theorising ,” in Practical Theorising in teacher education: Holding theory and practice together . eds. Burn K., Mutton T., Thompson I. (London: Taylor & Francis; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Choy S. C., Oo P. S. (2012). Reflective thinking and teaching practices: a precursor for incorporating critical thinking into the classroom? Online Submission 5 , 167–182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cirocki A., Widodo H. P. (2019). Reflective practice in English language teaching in Indonesia: shared practices from two teacher educators . Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 7 , 15–35. doi: 10.30466/ijltr.2019.120734 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke P. A. (2008). Reflective teaching model: a tool for motivation, collaboration, self-reflection, and innovation in learning . Georgia Educ. Res. J. 5 , 1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruickshank D. (1985). Uses and benefits of reflective teaching Phi Delta Kappan, 704–706. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20387492 [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies S. (2012). Embracing reflective practice . Educ. Prim. Care 23 , 9–12. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2012.11494064, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Day C. (1999). “ Researching teaching through reflective practice ,” in Researching teaching: Methodologies and practices for understanding pedagogy . ed. Loughran J. J. (London: Falmer; ) [ Google Scholar ]

- De Geest E., Joubert M. V., Sutherland R. J., Back J., Hirst C. (2011). Researching effective continuing professional development in mathematics education . In International Approaches to Professional Development of Mathematics Teachers. (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press; ), 223–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewey J. (1904). “ The relation of theory to practice in education ,” in Third yearbook of the National Society for the scientific study of education . ed. McMurray C. S. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press; ), 9–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewey J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process . New York: D.C. Heath and Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Georgii-Hemming E., Johansson K., Moberg N. (2020). Reflection in higher music education: what, why, wherefore? Music. Educ. Res. 22 , 245–256. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2020.1766006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibbs G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic. Oxford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gore J., Zeichner K. (1991). Action research and reflective teaching in preservice teacher education: a case study from the United States . Teach. Teach. Educ. 7 :136 [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant A., McKimm J., Murphy F. (2017). Developing reflective practice: A guide for medical students, doctors and teachers . West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant C., Zeichner K. (1984). “ On becoming a reflective teacher ,” in Preparing for reflective teaching . ed. Grant C. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenhalgh T. (2002). Intuition and evidence--uneasy bedfellows? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 52 , 395–400. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grimmett P. P., and Erickson G. L. (1988). Reflection in teacher education . New York: Teachers College Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guillaumier C. (2016). Reflection as creative process: perspectives, challenges and practice . Arts Human. Higher Educ. 15 , 353–363. doi: 10.1177/1474022216647381 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haarhoff B., Thwaites R., Bennett-Levy J. (2015). Engagement with self-practice/self-reflection as a professional development activity: the role of therapist beliefs . Aust. Psychol. 50 , 322–328. doi: 10.1111/ap.12152 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatton N., Smith D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation . Teach. Teach. Educ. 11 , 33–49. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huda M., Teh K. S. M. (2018). “ Empowering professional and ethical competence on reflective teaching practice in digital era ,” in Mentorship strategies in teacher education . eds. Dikilitas K., Mede E., Atay D. (IGI Global; ), 136–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hulsman R. L., Harmsen A. B., Fabriek M. (2009). Reflective teaching of medical communication skills with DiViDU: Assessing the level of student reflection on recorded consultations with simulated patients . Patient education and counseling 74 , 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huynh H. T. (2022). Promoting professional development in language teaching through reflective practice . Vietnam J. Educ. 6 , 62–68. doi: 10.52296/vje.2022.126 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jay J. K., Johnson K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education . Teach. Teach. Educ. 18 , 73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00051-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Karnieli-Miller O. (2020). Reflective practice in the teaching of communication skills . Patient Educ. Couns. 103 , 2166–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.021 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kennedy-Clark S., Eddles-Hirsch K., Francis T., Cummins G., Ferantino L., Tichelaar M., et al.. (2018). Developing pre-service teacher professional capabilities through action research . Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 43 , 39–58. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n9.3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Killen L. (1989). Reflective teaching . J. Teach. Educ. 40 , 49–52. doi: 10.1177/002248718904000209 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knassmüller M. (2022). “ The challenges of developing reflective practice in public administration: a teaching perspective ,” in Handbook of teaching public administration . eds. Bottom K., Diamond J., Dunning P., Elliott I. (Edward Elgar Publishing; ), 178–187. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolb D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development . PrenticeHall: New Jersey. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kovacs L., Corrie S. (2022). Building reflective capability to enhance coaching practice . In Coaching Practiced . eds. Tee D., Passmore J. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd; ), 85–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loughran J. J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: in search of meaning in learning about teaching . J. Teach. Educ. 53 , 33–43. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053001004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lubbe W., Botha C. S. (2020). The dimensions of reflective practice: a teacher educator’s and nurse educator’s perspective . Reflective Pract. 21 , 287–300. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2020.1738369 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall T. (2019). The concept of reflection: a systematic review and thematic synthesis across professional contexts . Reflective Pract. 20 , 396–415. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2019.1622520 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McAlpine L., Weston C., Berthiaume D., Fairbank-Roch G., Owen W. (2004). Reflection on teaching: types and goals of reflection . Educ. Res. Eval. 10 , 337–363. doi: 10.1080/13803610512331383489 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McGarr O. (2021). The use of virtual simulations in teacher education to develop pre-service teachers’ behaviour and classroom management skills: implications for reflective practice . J. Educ. Teach. 47 , 274–286. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1733398 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McNamara D. (1990). Research on teachers’ thinking: its contribution to educating student teachers to think critically . J. Educ. Teach. 16 , 147–160. doi: 10.1080/0260747900160203 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Noffke S., Brennan M. (1988). The dimensions of reflection: A conceptual and contextual analysis. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the America Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

- Oo T. Z., Habók A. (2020). The development of a reflective teaching model for Reading comprehension in English language teaching . Int. Electr. J. Element. Educ. 13 , 127–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Osterman K. F., Kottkamp R. B. (2004). Reflective practice for educators: Professional development to improve student learning . Thousand California: Corwin Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paterson C., Chapman J. (2013). Enhancing skills of critical reflection to evidence learning in professional practice . Phys. Ther. Sport 14 , 133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.03.004, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plessner H., Betsch C., Betsch T. (2011). The nature of intuition and its neglect in research on judgment and decision making . In Intuition in Judgment and Decision Making . (New York: Psychology Press; ), 23–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pollard A., Black-Hawkins K., Hodges G. C., Dudley P., James M., Linklater H., et al.. (2014). Reflective teaching in schools (4th edtn.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ratminingsih N. M., Artini L. P., Padmadewi N. N. (2018). Incorporating self and peer assessment in reflective teaching practices . Int. J. Instr. 10 , 165–184. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richards J. C., Lockhart C. (2005). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms . New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richardson V. (1990). “ The evolution of reflective teaching and teacher education ,” in Encouraging reflective practice in education . ed. Pugach M. (New York: Teachers College Press; ), 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross D. D. (1989). First steps in developing a reflective approach . J. Teach. Educ. 40 , 22–30. doi: 10.1177/002248718904000205 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruffinelli A., Álvarez Valdés C., Salas Aguayo M. (2022). Strategies to promote generative reflection in practicum tutorials in teacher training: the representations of tutors and practicum students . Reflective Pract. 23 , 30–43. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1974371 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schön D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . NewYork: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seitova M. (2019). Student Teachers’ perceptions of reflective practice . Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 6 , 765–772. [ Google Scholar ]

- Senge P. (1990). The 5th discipline . New York: Doubleday. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seyed Abolghasem F., Othman J., Ahmad Shah S. S. (2020). Enhanced learning: the hidden art of reflective journal writing among Malaysian pre-registered student nurses . J. Nusantara Stud. 5 , 54–79. doi: 10.24200/jonus.vol5iss1pp54-79 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shek M. M. P., Leung K. C., To P. Y. L. (2021). Using a video annotation tool to enhance student-teachers’ reflective practices and communication competence in consultation practices through a collaborative learning community . Educ. Inf. Technol. 26 , 4329–4352. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10480-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith D., Lovat T. (1991). Curriculum: Action on reflection (2nd edtn.). Wentworth Falls: Social Science Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spalding E., Wilson A., Mewborn D. (2002). Demystifying reflection: a study of pedagogical strategies that encourage reflective journal writing . Teach. Coll. Rec. 104 , 1393–1421. doi: 10.1111/1467-9620.00208 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sparks-Langer G., Colton A., Pasch M., Starko A. (1991). Promoting cognitive, critical, and narrative reflection. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

- Taggart G. L., Wilson A. P. (eds.) (2005). “ Becoming a reflective teacher ,” in Promoting reflective thinking in teachers: 50 action strategies (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press; ) [ Google Scholar ]

- Treacy D., Gaunt H. (2021). Promoting interconnections between reflective practice and collective creativity in higher arts education: the potential of engaging with a reflective matrix . Reflective Pract. 22 , 488–500. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1923471 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsangaridou N., O’Sullivan M. (1994). Using pedagogical reflective strategies to enhance reflection among preservice physical education teachers . J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 14 , 13–33. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.14.1.13 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Gyn G. H. (1996). Reflective practice: the needs of professions and the promise of cooperative education . J. Cooperat. Educ. 31 , 103–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Manen M. (1977). Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical . Curric. Inq. 6 , 205–228. doi: 10.1080/03626784.1977.11075533 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahid M., Khanam A. (2019). Effect of reflective teaching practices on the performance of prospective teachers . Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 18 , 32–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeichner K. M., Liston D. (1987). Teaching student teachers to reflect . Harv. Educ. Rev. 57 , 23–49. doi: 10.17763/haer.57.1.j18v7162275t1w3w [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

What is Reflective Teaching? Lessons Learned from ELT Teachers from the Philippines

- Regular Article

- Published: 11 January 2018

- Volume 27 , pages 91–98, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Paolo Nino Valdez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4404-350X 1 ,

- Jocelyn Amor Navera 1 &

- Jerico Juan Esteron 1

1283 Accesses

11 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Reflection is an essential dimension of effective teaching. It prompts classroom teachers to subject themselves to a process of self-observation or self-evaluation. By reflecting on what they do in the classroom, teachers specifically explore their teaching practices and beliefs and whether these, indeed, work. This then may lead teachers to continue or modify their teaching strategies for the improvement of their class instruction. Grounded on the notions of reflective practice (in: Kumaradivelu 2003 ; Freeman 2002 ; Borg 2003 ), this brief report aims to share insights from a case study conducted in the Philippines. Initially, the study presents challenges teachers face in the Philippine education system in terms of actualizing reflective teaching. Using a case study approach among teachers taking a master’s class on English Language Teaching issues, the presentation proceeds with discussing the teachers’ views on reflective teaching and the existing challenges faced in actualizing this practice in their respective contexts. The presentation further identifies teachers’ contrasting views about existing theoretical viewpoints on reflective teaching that may serve as potential areas for further investigation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Reflective Practice

Developing Reflective Practice

How Do I Know What I Think I Know? Teaching Reflection to Improve Practice

Benson, P. (2009). Learner autonomy. TESOL Quarterly, 47 (4), 839–842.

Article Google Scholar

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36 (2), 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444803001903 .

Borg, S. (2012). Current approaches to language teacher cognition research: A methodological analysis. In R. Barnard & A. Burns (Eds.), Research language teacher cognition and practice (pp. 11–29). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Google Scholar

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

de la Rosa, P. (2005). Toward a more reflective teaching practice: Revisiting excellence in teaching. Asia Pacific Education Review, 6 (2), 170–176.

Department of Education. (2016). DO no. 39, s. 2016—Adoption of the Basic Education Research Agenda [PDF document]. http://www.deped.gov.ph/sites/default/files/order/2016/DO_s2016_039.pdf.

Farrell, T.S.C. (2008). Reflective practice in the professional development of teachers of adult English language learners. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/pd_resources/CAELABrief-ReflectivePractice.pdf

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning to teach. Language Teaching, 35, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444801001720 .

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . New York: Seabury Press.

Hacker, P., & Barkhuizen, G. (2008). Autonomous teachers, autonomous cognition: Developing personal theories through reflection in language teacher education. In T. Lamb & H. Reinders (Eds.), Learner autonomy: Concepts, realities and issues (pp. 161–186). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Chapter Google Scholar

Jay, J. K., & Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18 (1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00051-8 .

Kumaradivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching . New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Kumaradivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod . New York/London: Taylor and Francis.

Martin, I. P. (2005). Conflicts and implications in Philippine education: Implications for ELT. In D. T. Dayag & J. S. Quakenbush (Eds.), Linguistics and language education in the Philippines and beyond: A festschrift in honor of Ma. Lourdes S. Bautista (pp. 267–280). Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

Ocampo, D. S. (2014). The K to 12 Curriculum [PDF document]. http://industry.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/6th-TID-Usec.-Ocampos-Presentation-on-K-to-12.pdf.

Perfecto, M. R. G. (2012). Contextual factors in teacher decision making: Extending the woods model. Asia Pacific Education Researcher, 21 (3), 474–483.

Rañosa-Madrunio, M., Tarrayo, V. N., Tupas, R., & Valdez, P. N. (2016). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and practices in the Philippines. In R. Barnard & J. Li (Eds.), Language learner autonomy: Teachers’ beliefs and practices in Asian contexts (pp. 114–133). Phnom Penh: IDP Education (Cambodia) Ltd.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York, USA: Basic Books Inc.

Valdez, P., & Lapinid, M. R. (2015). The constraints of math teachers in the conduct of action research: A rights analysis. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 12, 1–19.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English and Applied Linguistics, Brother Andrew Gonzalez College of Education, De La Salle University, 1501 Andrew Gonzalez Hall, DLSU 2401 Taft Avenue, 1004, Manila, Philippines

Paolo Nino Valdez, Jocelyn Amor Navera & Jerico Juan Esteron

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paolo Nino Valdez .

Appendix A: Informed Consent Form

Dear Student:

We are conducting a research on the reflective teaching and challenges in applying reflective teaching in the workplace. We seek your participation through our interview and responding to this simple survey. Rest assured that your participation in the study will not have any bearing on your grades for the class. Moreover, data that will be gathered shall be used exclusively for the aforementioned purposes. Likewise, data that you will provide shall be treated with utmost confidentiality. Therefore, your confirmation shall mean that you agree to participate in this project.

Researchers

Name (optional):

Levels/subjects taught:

Years of teaching experience:

Reflective exercise:

The set of questions do not have right or wrong answers as these do not have a bearing on your grades.

What is reflective teaching for you, and how do you practice it in the classroom?

Does your workplace allow you to become a reflective teacher? What could be the possible impediments to achieving this, and in what way can your institution help you become reflective teachers?

How does reflective teaching affect your view or practice of:

Work as teachers?

Students as language learners?

School as an institution of progress?

Interview questions:

Could you narrate some experiences related to the application of reflective teaching? What was your goal? And were these goals met?

In what ways do you think your institution has been helpful or not helpful in making you a reflective teacher? Could you cite specific instances concerning this?

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Valdez, P.N., Navera, J.A. & Esteron, J.J. What is Reflective Teaching? Lessons Learned from ELT Teachers from the Philippines. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 27 , 91–98 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0368-3

Download citation

Published : 11 January 2018

Issue Date : April 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0368-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- English Language Teaching

- Philippine education

- Reflective teaching

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Problem Solving through Reflective Practice. Reflective practice allows educators to identify areas of needs and while developing strategies built upon documented knowledge and information. "It is a way of thinking that fosters personal learning, behavioral change, and improved performance" (Ostermann & Kottkamp, 2004, p.

outside context as these influence their teaching quality. Reflective practice is a key to promote this understanding (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009). In other words, reflective practice provides teachers ... reflective practice and problem-solving tasks are similar in Dewey's view. Building on Dewey's work, Schön (1983) extends the concept of ...

Reflective practice (RP) is a concept that has been studied by scholars in a wide variety of fields, including evaluation (e.g., Archibald et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2015; van Draanen, 2017), and much of the conversation has centered on what the term means and what it ought to mean as part of professional practice (e.g., Finlay, 2008; Fook et al., 2006; Ganly, 2018; Jones & Stubbe, 2004 ...

Abstract. Reflective practices in education are widely advocated for and have become important components of professional reviews. The advantages of reflective practices are many; however, the literature often focuses on the benefits to students, rather than the benefits for the educators themselves. Additionally, the extant literature ...

group of learners. This description of the reflective teacher is similar to char-acteristics of the professional teacher as described by Steffy et al. (2000). One of the primary ways that a teacher develops into a professional is through the process of reflective problem solving as described by Dewey and Schon (Steffy et al., 2000).

Enhances problem-solving. Learning to solve problems and meet challenges effectively and efficiently is incredibly important in the classroom. Reflective practice gives educators the time to identify solutions for the challenges they are facing. ... Reflective practice is a key part of teaching and learning. And it doesn't have to be hard or ...

Lawrence-Wilkes and Ashmore suggest that 'Schön was influential in changing understanding when he described the 'reflective practitioner' in professional practice as a way of developing teaching beyond a technical-rational model' (p. 12). However, as with any such change, there has been misunderstanding and misappropriation in the ...

The 21st-century skillset is generally understood to encompass a range of competencies, including critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, meta-cognition, communication, digital and technological literacy, civic responsibility, and global awareness (for a review of frameworks, see Dede, 2010).And nowhere is the development of such competencies more important than in developing country ...

Similarly, in the context of co-teaching, researchers conclude that collaborative discussion of problem cases and teaching practices may facilitate the exchange of individual knowledge and the development of more positive attitudes towards a more reflective and evidence-based practice (Baeten and Simons 2014; Birrell and Bullough 2005; Nokes et ...

We explore development of elementary preservice teachers' reflective practices as they solved problems encountered while teaching in a reading clinic. Written reflections ( N = 175) were collected across 8 weeks from 23 preservice teachers and analyzed to investigate relationships among problem exploration, teaching adaptations, and problem ...

Working on solutions. In the solution phase, one develops and then implements a coherent plan for solving the problem. As you help students with this phase, you might ask them to: identify the general model or procedure they have in mind for solving the problem. set sub-goals for solving the problem. identify necessary operations and steps.

Complex problem solving is an effective means to engage students in disciplinary content while also furnishing critical non-cognitive and life skills. Despite increased adoption of complex problem-solving methods in K-12 classrooms today (e.g., case-, project-, or problem-based learning), we know little about how to make these approaches accessible to linguistically and culturally diverse (LCD ...

In the field of education, reflective practice has been recognized as an important aspect in continuing professional development. Through reflective practice, we can identify the factors, the consequences of and the assumptions that underlie our actions. In higher education, reflective practice has become a dynamic, participatory, and cyclical ...

Abstract. This study aimed to investigate the levels of teachers′ reflective practices as well as their attitudes toward professional self-development in relation to various variables, including gender, number of workshops attended and experience. The study sample consisted of 162 teachers who work as teachersat a number of private schools in ...

Within this course, we focus on developing effective problem solvers through students' teaching practices. We discuss reflective practices necessary for teaching and problem solving; theoretical frames for effective learning; how culture, context, and identity impact problem solving and teaching; and the impact of the problem-solving cycle.

It occurs when solving a problem or attempting to better understand a complex situation, and results in an awareness from which emerges a questioning of the act of teaching ( De Champlain, 2013; Dewey, 1933; Lison, 2013 ). Reflective practice includes three stages: 1) reflection before action; 2) reflection in action; and 3) reflection on action.

4.2.1.5 Definition of Reflective Teaching. In this study, Zeichner and Liston's definition of reflective teaching has been adopted because it proposes a solution to the dilemmas of classroom practice, which fits well with the subject of this study.Based on a distinction between teaching that is reflective and teaching that is technically focused, Zeichner and Liston argue that reflective ...

These frames call for teaching and problem solving methods that require the use of reflective thinking, which promotes deeper learning and optimizes ... practice, reflective learning is a tool that each student should practice habitually for it is through the process of reflection that students think and organize their internal thoughts as ...

Abstract. The challenges of 21st century skills require equipping children with essential dispositions and reflective skills as relevant dimension of education. Reflection is a valuable skill that ...

When discussing the instructional practice of teachers, it is believed that "effective self-reflection is a key component of excellent teaching" (Bell et al., 2010, p. 57), and "reflective practice can be a beneficial process in teacher professional development" (Ferraro, 2000, para. 1).

We explore development of elementary preservice teachers' reflective practices as they solved problems encountered while teaching in a reading clinic. Written reflections (N = 175) were collected across 8 weeks from 23 preservice teachers and analyzed to investigate relationships among problem exploration, teaching adaptations, and problem resolution.

Reflection is an essential dimension of effective teaching. It prompts classroom teachers to subject themselves to a process of self-observation or self-evaluation. By reflecting on what they do in the classroom, teachers specifically explore their teaching practices and beliefs and whether these, indeed, work. This then may lead teachers to continue or modify their teaching strategies for the ...

A reflective teaching-based program for developing teaching skills in accordance with quality standards and improving the teaching theory of Arabic language and Islamic pre-service teachers in Egypt and Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Education, 2(7), 652-682. Hassan S. A., & Mojtaba, F. (2018).