Motivation Theories Essay

Introduction, theories of motivation – elton mayo, abraham maslow, theories’ application in creative technology, motivation theory in marketing, motivation tools and techniques, references list.

Motivation is the force that drives people into action and encourages them into exerting more effort towards carrying out something. Motivated employees feel more comfortable and will have feelings of happiness and fulfillment. Besides, motivated workers tend to produce quality results, and are more productive than their counterparts are.

Different factors exist that can determine how an individual is motivated; for instance, everyone has basic needs like; food and shelter which can be catered for by pay. However, other diverse motivators exist that stimulate people into action. A creative environment can encourage motivation especially in design where a high level of creativity is critical.

Some workers will do well given the problem solving nature of their jobs and support initiative against challenges. Besides, creative staff will find the diverse nature of their occupation encouraging because they have the opportunity to try special responsibilities.

According to Elton Mayo, employees are not only motivated by pay, but could also be highly motivated if their social needs are fulfillment especially when they are at the workplace (Sheldrake, 2003). Mayo introduced a new way of looking at employees and argued that managers and supervisors need to have an interest in employees. This involves valuing their opinions and treating them in a worthwhile manner by recognizing that they take pride in inter-personal interactions.

While coming up with the theory, Mayo experimented at the Western Electric Hawthorne factory in Chicago. He separated two groups of women employees and viewed the outcome to productivity intensity in varying environments like working conditions and lighting. Contrary to his expectations, he was surprised to note the productivity of the employees improved or remained constant even with varying lighting and other working conditions. He then concluded that employees are highly motivated by various factors.

Among his top picks are better communication between employees and their managers. When employees feel there exists consultation on their roles and responsibilities with the managers, they tend to perform better also if given the chance to give feedback.

The second factor he discovered was the fact that employees responded very well to increased manager participation in their working lives. Besides the two, Mayo also identified teamwork as a motivator in working environments. He stated that corporate and businesses should reorganize to encourage teamwork, which is a theory that closely links to paternalistic management style.

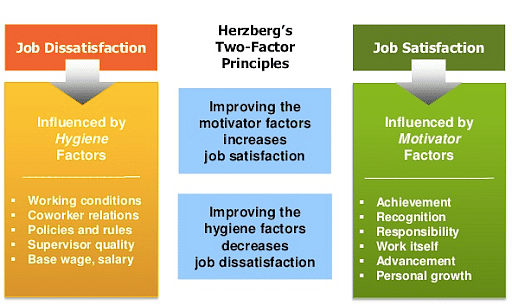

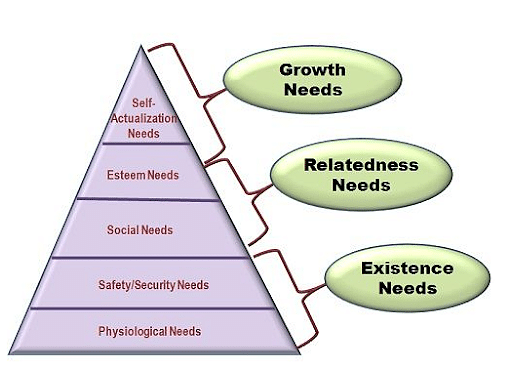

In the 1950’s, Abraham Maslow with Frederick Herzberg came up with the neo-human relations school. According to Montana and Charnov (2008), “The school focused on employees’ psychological needs” (p. 408). In his theory, Maslow illustrates five stages in human needs that workers need to fulfill at the workplace.

Maslow then structured the needs into a hierarchy. When a lower need is fulfilled that an employee will be motivated to the next stage or need. For instance, a person threatened by hunger will have a great motivation to achieve a basic wage to satisfy the need to eat by buying food. in this sense, the person will have less motivation towards getting a formal or secure employment.

At the bottom, of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, physiological needs are the lowest and the most basic; this involves the basic needs of humans, which he argued must be satisfied to sustain life. After the physiological needs are satisfied, attention now shifts towards safety.

In a job environment, this could mean the workers are motivated to such things like living in a safe area, secure job and medical insurance as well as saving for the future. Mackay (2007) noted that “If employees feel there is not enough security provided by their jobs, higher needs will remain unattended” (p.281). Social needs are third in the hierarchy.

Maslow’s theory explains that once the lower levels are satisfied, social needs become a motivator as people have other needs for friends or the need to belong. Esteem needs come after employees feeling the need to be recognized and build their reputation. At the peak of the hierarchy, Maslow describes that this is where people pursue the need to self -actualize.

However, Montana and Charnov (2008) state that “Maslow’s theory stipulates that need to self- actualize is not fully realized as people are constantly pursuing changing endeavors” (p.191). The needs here are mostly related to truth, justice and meaning.

In creative businesses, such as website design, businesses should strive towards giving incentives that meet the needs of the staff to motivate them to progress up the hierarchy.

Furthermore, Maslow’s theory dictates that, it is essential for managers to realize that workers respond differently to different incentives to increase output. Besides, all workers progress up the hierarchy at different paces. According to Mayo’s theory, creative employees should be encouraged to work in teams. Sheldrake (2003) found out that “creativity seems to be strengthened by teamwork” (p.122).

When applying motivation theories in marketing, few changes are necessary. As explained by O’Neil and Drillings (1994) “different employees in different departments will be motivated by different incentives” (p.233). In the marketing of merchandise, high levels of motivation are required from the staff.

A good salary package and attractive benefits attracted from the sales will be necessary in ensuring maximum productivity is reached. On the contrary, employees in creative fields require a serene working environment among other incentives to maximize on productivity.

Pleasure technique is one of the oldest. The tool ensures a pleasurable reward for productivity and in turn creates motivation in employees to become more productive, besides when employees feel that their efforts are being rewarded they will tend to produce more and more.

According to Daft and Lane (2007) “performance incentives play a key role in ensuring high levels of motivation” (p. 102). It works best by creating an appeal to people’s selfishness, and by giving employees an opportunity to earn more, you as an employer will earn more.

In addition, setting deadlines will help achieve more as workers will tend to realize more productivity and are able to concentrate more when nearing a deadline. This can be achieved by creation of smaller deadlines that lead to a bigger result. It is important for managers to encourage team spirit and create an environment of teamwork.

Mackay (2007) noted that “when people work in a team they tend to be more effective” (p. 253) and besides, they don’t want to pull others down by not putting enough effort. Encouraging creativity is very essential, as employees feel more comfortable within an optimistic environment. The last tool for effective motivation is communication. Managers should uphold open channels of communication. This enables one to fix the problems as soon as they arise and it creates a better working environment.

It is important for every business to take note of the theory to implement. Depending on its line of trade, various incentives may be given to employees to maximize production.

Daft, R. L., & Lane, P. G. (2007). The leadership experience . Florence, KY: Cengage Learning

Mackay, A. (2007). Motivation, Ability and Confidence Building in People . London: Taylor & Francis

Montana, P. J., &Charnov, B. H. (2008). Management. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series

O’Neil, H. F., Drillings, M. (1994). Motivation: Theory and Research. New York, NY: Routledge

Sheldrake, J. (2003). Management theory . Florence, KY: Cengage Learning

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 28). Motivation Theories. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories/

"Motivation Theories." IvyPanda , 28 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Motivation Theories'. 28 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Motivation Theories." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories/.

1. IvyPanda . "Motivation Theories." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Motivation Theories." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/motivation-theories/.

- An Analysis on Elton John’s Candle in the Wind 1997 Song

- George Elton Mayo’s Outlook

- Miss Brodie and Miss Mackay - Difference in Education Idea

- Miss Brodie and Miss Mackay’s Ideas of Education

- “Reality TV...” Article by Joanne Morreale

- Technology and Society Relations

- Comparison of Ball Scene in "Emma" With Frat Party Scene in "Clueless"

- Mayo Clinic: Marketing of the Healthcare System

- "Emma" by Jane Austen: Main Character Analysis

- Healthcare Institutions: Problems Facing Management

- Leadership and Cultural Differences

- Career Planning and Succession Management

- Running of Multinational Internet Firm

- Time Management Theories and Models Report

- Examination of the Portfolio Approach to IT Projects

Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research

- First Online: 03 May 2018

Cite this chapter

- Paulina Arango 4

Part of the book series: Literacy Studies ((LITS,volume 15))

1595 Accesses

2 Citations

Motivation is a psychological construct that refers to the disposition to act and direct behavior according to a goal. Like most of psychological processes, motivation develops throughout the life span and is influenced by both biological and environmental factors. The aim of this chapter is to summarize research on the development of motivation from infancy to adolescence, which can help understand the typical developmental trajectories of this ability and its relation to learning. We will start with a review of some of the most influential theories of motivation and the aspects each of them has emphasized. We will also explore how biology and experience interact in this development, paying special attention to factors such as: school, family, and peers, as well as characteristics of the child including self-esteem, cognitive development, and temperament. Finally, we will discuss the implications of understanding the developmental trajectories and the factors that have an impact on this development, for both teachers and parents.

- Achievement

- Motivational theories

- Influences on motivation

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is not intended to be an exhaustive review of motivational theories. For a more detailed review see: (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2013 ; Eccles and Wigfield 2002 ; Wentzel and Miele 2009 ; Wigfield et al. 2007 ).

For more information on the development of motivation in adults you can see: Carstensen 1993 ; Kanfer and Ackerman 2004 ; Wlodkowski 2011 .

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64 (6), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445 .

Article Google Scholar

Atkinson, J. W., & Raynor, J. O. (1978). Personality, motivation, and achievement . Oxford: Hemisphere.

Google Scholar

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. E. (2002). Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and self-concept. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72 (3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902320634447 .

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). Self-regulation of motivation through anticipatory and self-reactive mechanisms. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 69–164). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp. 154–196). New York: Guilford.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72 (1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273 .

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10 (3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/10.3.295 .

Boulton, M. J., Don, J., & Boulton, L. (2011). Predicting children’s liking of school from their peer relationships. Social Psychology of Education, 14 (4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9156-0 .

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 .

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21 (1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x .

Buss, D. M. (2008). Human nature and individual differences. In S. E. Hampson & H. S. Friedman (Eds.), The handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 29–60). New York: The Guilford Press.

Cain, K. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1989). The development of children’s conceptions of Intelligence; A theoretical framework. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of human intelligence (Vol. 5, pp. 47–82). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cain, K., & Dweck, C. S. (1995). The relation between motivational patterns and achievement cognitions through the elementary school years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41 (1), 25–52.

Carlson, C. L., Mann, M., & Alexander, D. K. (2000). Effects of reward and response cost on the performance and motivation of children with ADHD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24 (1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005455009154 .

Carstensen, L. L. (1993, January). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 40, pp. 209–254).

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591 (1), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102 .

Coll, C. G., Bearer, E. L., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Nature and nurture: The complex interplay of genetic and environmental influences on human behavior and development . Mahwah: Psychology Press.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55 (2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003–066X.55.2.218 .

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38 (2), 179. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.2.179 .

Connell, J. P. (1985). A new multidimensional measure of children’s perception of control. Child Development, 56 (4), 1018–1041. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130113 .

Damasio, A. R., Everitt, B. J., & Bishop, D. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex [and discussion]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 351 (1346), 1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0125 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self–determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 .

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002a). The paradox of achievement: The harder you push, the worse it gets. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 61–87). San Diego: Academic Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002b). Self–determination research: Reflections and future directions. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self–determination theory research (pp. 431–441). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation . London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833750 .

Book Google Scholar

Dweck, C. S. (2002). The development of ability conceptions. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 57–88). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978–012750053–9/50005–X .

Eccles, J. S. (1987). Gender roles and women’s achievement–related decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11 (2), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471–6402.1987.tb00781.x .

Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self–perceptions, and activity choice. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 145–208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1993). Parent–school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teachers’ College Record, 94 , 568–587.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy–related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003 .

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 (1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. B. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self– And task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64 (3), 830–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8624.1993.tb02946.x .

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology (5th ed. Vol. 3, pp. 1017–1095). New York: Wiley.

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., & Kaczala, C. M. (1982). Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development, 53 (2), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128973 .

Eccles–Parsons, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco: Freeman.

Eggen, P. D., & Kauchak, D. P. (2007). Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms . Virginia: Prentice Hall.

Ernst, M. (2014). The triadic model perspective for the study of adolescent motivated behavior. Brain and Cognition, 89 , 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.01.006 .

Ernst, M., & Fudge, J. L. (2009). A developmental neurobiological model of motivated behavior: Anatomy, connectivity and ontogeny of the triadic nodes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33 (3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.009 .

Ernst, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2005). Neurobiology of decision making: A selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (8), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.004 .

Ernst, M., Pine, D. S., & Hardin, M. (2006). Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 36 (03), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291705005891 .

Ernst, M., Romeo, R. D., & Andersen, S. L. (2009). Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: A window into a neural systems model. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 93 (3), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children’s competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male–sex–typed domains. Developmental Psychology, 38 (4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.38.4.519 .

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145–164). Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle . London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Friedel, J. M., Cortina, K. S., Turner, J. C., & Midgley, C. (2007). Achievement goals, efficacy beliefs and coping strategies in mathematics: The roles of perceived parent and teacher goal emphases. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32 (3), 434–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.10.009 .

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022–0663.95.1.148 .

Gallardo, L. O., Barrasa, A., & Guevara–Viejo, F. (2016). Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and midadolescence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44 (10), 1637–1648. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1637 .

Glenn, S., Dayus, B., Cunningham, C., & Horgan, M. (2001). Mastery motivation in children with down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 7 (2), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.3104/reports.114 .

Gniewosz, B., Eccles, J. S., & Noack, P. (2015). Early adolescents’ development of academic self-concept and intrinsic task value: The role of contextual feedback. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25 (3), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12140 .

Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender–related math attitudes. Sex Roles, 66 (3–4), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2 .

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Perencevich, K. C. (Eds.). (2004). Motivating reading comprehension: Concept oriented reading instruction . Mahwah: Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610126 .

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., & Elliot, A. J. (1998). Rethinking achievement goals: When are they adaptive for college students and why? Educational Psychologist, 33 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3301_1 .

Heckhausen, H. (1987). Emotional components of action: Their ontogeny as reflected in achievement behavior. In D. Gîrlitz & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Curiosity, imagination, and play (pp. 326–348). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Heckhausen, J. (2000). Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development . Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(00)80003-5 .

Hokoda, A., & Fincham, F. D. (1995). Origins of children’s helpless and mastery achievement patterns in the family. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.375 .

Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior: An introduction to behavior theory . Oxford: Appleton-Century Company, Incorporated.

Jacobs, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Parents, task values, and real-life achievement-related choices. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 405–439). San Diego: Academic Press.

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73 (2), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00421 .

Jacobs, J. E., Davis-Kean, P., Bleeker, M., Eccles, J. S., & Malanchuk, O. (2005). I can, but I don’t want to. The impact of parents, interests, and activities on gender differences in math. In A. Gallagher & J. Kaufman (Eds.), Gender differences in mathematics: An integrative psychological approach (pp. 246–263). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James, W. (1963). Psychology . New York: Fawcett.

Kahne, J., Nagaoka, J., Brown, A., O’Brien, J., Quinn, T., & Thiede, K. (2001). Assessing after-school programs as contexts for youth development. Youth & Society, 32 (4), 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X01032004002 .

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Academy of Management Review, 29 (3), 440–458. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2004.13670969 .

Karbach, J., Gottschling, J., Spengler, M., Hegewald, K., & Spinath, F. M. (2013). Parental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescence. Learning and Instruction, 23 , 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.09.004 .

King, R. B., & Ganotice, F. A., Jr. (2014). The social underpinnings of motivation and achievement: Investigating the role of parents, teachers, and peers on academic outcomes. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23 (3), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0148-z .

Kleinginna, P. R., Jr., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of motivation definitions, with a suggestion for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5 (3), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993889 .

Lee, J., & Shute, V. J. (2010). Personal and social-contextual factors in K–12 academic performance: An integrative perspective on student learning. Educational Psychologist, 45 (3), 185–202. 1080/00461520.2010.493471 .

Lee, V. E., & Smith, J. (2001). Restructuring high schools for equity and excellence: What works . New York: Teachers College Press.

Linnenbrink, E. A. (2005). The dilemma of performance-approach goals: The use of multiple goal contexts to promote students’ motivation and learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97 (2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.197 .

Logan, M., & Skamp, K. (2008). Engaging students in science across the primary secondary interface: Listening to the students’ voice. Research in Science Education, 38 (4), 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-007-9063-8 .

Mantzicopoulos, P., French, B. F., & Maller, S. J. (2004). Factor structure of the pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance with two pre-elementary samples. Child Development, 75 (4), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00734.x .

Marjoribanks, K. (2002). Family and school capital: Towards a context theory of students’ school outcomes . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9980-1 .

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 .

McDougal, W. (1908). An introduction to social psychology . Boston: John W. Luce and Co..

McInerney, D. M. (2008). Personal investment, culture and learning: Insights into school achievement across Anglo, aboriginal, Asian and Lebanese students in Australia. International Journal of Psychology, 43 (5), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701836364 .

Midgley, C. (Ed.). (2014). Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning . Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410602152 .

Murdock, T. B., Hale, N. M., & Weber, M. J. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26 (1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1046 .

National Research Council. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school students’ motivation to learn . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.42–1079 .

Nelson, R. M., & DeBacker, T. K. (2008). Achievement motivation in adolescents: The role of peer climate and best friends. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76 (2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.2.170-190 .

Niccols, A., Atkinson, L., & Pepler, D. (2003). Mastery motivation in young children with Down’s syndrome: Relations with cognitive and adaptive competence. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47 (2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00452.x .

Nicholls, J. G. (1979). Development of perception of own attainment and causal attributions for success and failure in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71 (1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.71.1.94 .

Nicholls, J. G., & Miller, A. T. (1984). The differentiation of the concepts of difficulty and ability. Child Development, 54 (4), 951–959. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129899 .

Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., Ryan, A. M., Edelin, K. C., & Midgley, C. (2001). Teachers’ communication of goal orientations in four fifth-grade classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 102 (1), 35–58. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1002168 .

Pavlov, I. P. (2003). Conditioned reflexes . Mineola: Courier Corporation.

Pesu, L. A., Aunola, K., Viljaranta, J., & Nurmi, J. E. (2016a). The development of adolescents’ self-concept of ability through grades 7–9 and the role of parental beliefs. Frontline Learning Research, 4 (3), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i3.249 .

Pesu, L., Viljaranta, J., & Aunola, K. (2016b). The role of parents’ and teachers’ beliefs in children’s self-concept development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 44 , 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.03.001 .

Petri, H. L., & Govern, J. M. (2012). Motivation: Theory, research, and application . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 (3), 544–555. 10.I037//0022-O663.92.3.544 .

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 (4), 667. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667 .

Pintrich, P. R., & Maehr, M. L. (2004). Advances in motivation and achievement: Motivating students, improving schools (Vol. 13). Bingley: Emerald Grup Publishing Limited.

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. (2004). Family correlates of trajectories of academic motivation during a school transition: A semiparametric group-based approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (4), 743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.743 .

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (1998). Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Development and Psychopathology, 10 (02), 321–352.

Roeser, R. W., Marachi, R., & Gelhbach, H. (2002). A goal theory perspective on teachers’ professional identities and the contexts of teaching. In C. M. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 205–241). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976 .

Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescents’ motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72 (4), 1135–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00338 .

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination theory research (pp. 3–33). Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 15–32). San Diego: Academic Press.

Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. R., & Pintrich, P. R. (2012). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications . Harlow: Pearson Higher Ed.

Shell, D. F., Colvin, C., & Bruning, R. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, attribution, and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement: Grade-level and achievement-level differences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.386 .

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Friendship networks and achievement goals: An examination of selection and influence processes and variations by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43 (9), 1453–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0132-9 .

Simpkins, S. D., Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Charting the Eccles’ expectancy-value model from mothers’ beliefs in childhood to youths’ activities in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 48 (4), 1019–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027468 .

Simpson, R. D., & Oliver, J. (1990). A summary of major influences on attitude toward and achievement in science among adolescent students. Science Education, 74 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730740102 .

Sjaastad, J. (2012). Sources of inspiration: The role of significant persons in young people’s choice of science in higher education. International Journal of Science Education, 34 (10), 1615–1636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2011.590543 .

Skinner, B. F. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18 (8), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045185 .

Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived control, motivation, and coping . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Skinner, E. A., Chapman, M., & Baltes, P. B. (1988). Control, meansends, and agency beliefs: A new conceptualization and its measurement during childhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.117 .

Skinner, E. A., Gembeck-Zimmer, M. J., & Connell, J. P. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 6 (2/3. Serial No. 254), 1–220.

Stipek, D., Recchia, S., McClintic, S., & Lewis, M. (1992). Self-evaluation in young children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 57 (1. Serial No. 226) 1–97.

Swarat, S., Ortony, A., & Revelle, W. (2012). Activity matters: Understanding student interest in school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49 (4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21010 .

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Leaper, C. (2003). Parent-child conversations about science: The socialization of gender inequities? Developmental Psychology, 39 (1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.34 .

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The law of effect. The American Journal of Psychology, 39 (1/4), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/141541310.2307/1415413 .

Ushioda, E. (2007). Motivation, autonomy and sociocultural theory. In P. Benson (Ed.), Learner autonomy 8: Teacher and learner perspectives (pp. 5–24). Dublin: Authentik.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29 , 271–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60019-2 .

Vedder-Weiss, D., & Fortus, D. (2013). School, teacher, peers, and parents’ goals emphases and adolescents’ motivation to learn science in and out of school. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50 (8), 952–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21103 .

Véronneau, M. H., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Dishion, T. J., & Tremblay, R. E. (2010). Transactional analysis of the reciprocal links between peer experiences and academic achievement from middle childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46 (4), 773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019816 .

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J. H., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Telang, F., & Wong, C. (2011). Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Molecular Psychiatry, 16 (11), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.97 .

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83 (3), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x .

Wang, M. T., & Sheikh-Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85 (2), 610–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12153 .

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92 (4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548 .

Weiner, B., Frieze, I., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R. M. (1987). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 95–120). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Weisz, J. P. (1984). Contingency judgments and achievement behavior: Deciding what is controllable and when to try. In J. G. Nicholls (Ed.), The development of achievement motivation (pp. 107–136). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (2), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2000). What is it that I’m trying to achieve? Classroom goals from a content perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1021 .

Wentzel, K. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73 (1), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00406 .

Wentzel, K. R. (2005). Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school. In C. S. Dweck & A. J. Elliot (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 279–296). New York: Guilford Press.

Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of motivation at school . New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., & Muenks, K. (2016). Peer influence on students’ motivation, academic achievement, and social behavior. In K. R. Wentzel & G. B. Ramani (Eds.), Handbook of social influences in school contexts: Social-emotional, motivation, and cognitive outcomes (pp. 13–30). New York: Routledge.

Wentzel, K. R., Battle, A., Russell, S. L., & Looney, L. B. (2010). Social supports from teachers and peers as predictors of academic and social motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35 (3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.002 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12 (3), 265–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90011-P .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015 .

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). The development of competence beliefs and values from childhood through adolescence. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 92–120). San Diego: Academic Press.

Wigfield, A., & Tonks, S. (2004). The development of motivation for reading and how it is influenced by CORI. In J. T. Guthrie, A. Wigfield, & K. C. Perencevich (Eds.), Motivating reading comprehension: Concept-oriented reading instruction (pp. 249–272). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Wigfield, A., & Wagner, A. L. (2005). Competence, motivation, and identity development during adolescence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 222–239). New York: Guilford Press.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A. J., Freedman-Doan, C., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (1997). Change in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A 3-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (3), 451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation . In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon & R.M. Lerner (Vol. 3, pp.933–1002). Hoboken: Wiley. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0315 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis‐Kean, P. (2007). Development of achievement motivation . Hoboken: Wiley.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2008). Development of achievement motivation. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, D. Kuhn, R. S. Siegler, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 406–434). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (2011). Enhancing adult motivation to learn: A comprehensive guide for teaching all adults . San Francisco: Wiley.

Woodworth, R. S. (1918). Dynamic Psychology . New York: Columbia University Press.

Yeung, W. J., Linver, M. R., & Brooks–Gunn, J. (2002). How money matters for young children's development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development, 73 (6), 1861–1879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511 .

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: Relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Escuela de Psicología, Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile

Paulina Arango

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paulina Arango .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Pelusa Orellana García

Institute of Literature, Universidad de los Andes, Las Condes, Chile

Paula Baldwin Lind

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Arango, P. (2018). Motivation: Introduction to the Theory, Concepts, and Research. In: Orellana García, P., Baldwin Lind, P. (eds) Reading Achievement and Motivation in Boys and Girls. Literacy Studies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75948-7_1

Published : 03 May 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-75947-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-75948-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Motivation: The Driving Force Behind Our Actions

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Emily Roberts

- Improvement

The term motivation describes why a person does something. It is the driving force behind human actions. Motivation is the process that initiates, guides, and maintains goal-oriented behaviors.

For instance, motivation is what helps you lose extra weight, or pushes you to get that promotion at work. In short, motivation causes you to act in a way that gets you closer to your goals. Motivation includes the biological , emotional , social , and cognitive forces that activate human behavior.

Motivation also involves factors that direct and maintain goal-directed actions. Although, such motives are rarely directly observable. As a result, we must often infer the reasons why people do the things that they do based on observable behaviors.

Learn the types of motivation that exist and how we use them in our everyday lives. And if it feels like you've lost your motivation, do not worry. There are many ways to develop or improve your self-motivation levels.

Press Play for Advice on Motivation

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares an exercise you can use to help you perform your best. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

What Are the Types of Motivation?

The two main types of motivation are frequently described as being either extrinsic or intrinsic.

- Extrinsic motivation arises from outside of the individual and often involves external rewards such as trophies, money, social recognition, or praise.

- Intrinsic motivation is internal and arises from within the individual, such as doing a complicated crossword puzzle purely for the gratification of solving a problem.

A Third Type of Motivation?

Some research suggests that there is a third type of motivation: family motivation. An example of this type is going to work when you are not motivated to do so internally (no intrinsic motivation), but because it is a means to support your family financially.

Why Motivation Is Important

Motivation serves as a guiding force for all human behavior. So, understanding how motivation works and the factors that may impact it can be important for several reasons.

Understanding motivation can:

- Increase your efficiency as you work toward your goals

- Drive you to take action

- Encourage you to engage in health-oriented behaviors

- Help you avoid unhealthy or maladaptive behaviors, such as risk-taking and addiction

- Help you feel more in control of your life

- Improve your overall well-being and happiness

Click Play to Learn More About Motivation

This video has been medically reviewed by John C. Umhau, MD, MPH, CPE .

What Are the 3 Components of Motivation?

If you've ever had a goal (like wanting to lose 20 pounds or run a marathon), you probably already know that simply having the desire to accomplish these things is not enough. You must also be able to persist through obstacles and have the endurance to keep going in spite of difficulties faced.

These different elements or components are needed to get and stay motivated. Researchers have identified three major components of motivation: activation, persistence, and intensity.

- Activation is the decision to initiate a behavior. An example of activation would be enrolling in psychology courses in order to earn your degree.

- Persistence is the continued effort toward a goal even though obstacles may exist. An example of persistence would be showing up for your psychology class even though you are tired from staying up late the night before.

- Intensity is the concentration and vigor that goes into pursuing a goal. For example, one student might coast by without much effort (minimal intensity) while another student studies regularly, participates in classroom discussions, and takes advantage of research opportunities outside of class (greater intensity).

The degree of each of these components of motivation can impact whether you achieve your goal. Strong activation, for example, means that you are more likely to start pursuing a goal. Persistence and intensity will determine if you keep working toward that goal and how much effort you devote to reaching it.

Tips for Improving Your Motivation

All people experience fluctuations in their motivation and willpower . Sometimes you feel fired up and highly driven to reach your goals. Other times, you might feel listless or unsure of what you want or how to achieve it.

If you're feeling low on motivation, there are steps you can take to help increase your drive. Some things you can do to develop or improve your motivation include:

- Adjust your goals to focus on things that really matter to you. Focusing on things that are highly important to you will help push you through your challenges more than goals based on things that are low in importance.

- If you're tackling something that feels too big or too overwhelming, break it up into smaller, more manageable steps. Then, set your sights on achieving only the first step. Instead of trying to lose 50 pounds, for example, break this goal down into five-pound increments.

- Improve your confidence . Research suggests that there is a connection between confidence and motivation. So, gaining more confidence in yourself and your skills can impact your ability to achieve your goals.

- Remind yourself about what you've achieved in the past and where your strengths lie. This helps keep self-doubts from limiting your motivation.

- If there are things you feel insecure about, try working on making improvements in those areas so you feel more skilled and capable.

Causes of Low Motivation

There are a few things you should watch for that might hurt or inhibit your motivation levels. These include:

- All-or-nothing thinking : If you think that you must be absolutely perfect when trying to reach your goal or there is no point in trying, one small slip-up or relapse can zap your motivation to keep pushing forward.

- Believing in quick fixes : It's easy to feel unmotivated if you can't reach your goal immediately but reaching goals often takes time.

- Thinking that one size fits all : Just because an approach or method worked for someone else does not mean that it will work for you. If you don't feel motivated to pursue your goals, look for other things that will work better for you.

Motivation and Mental Health

Sometimes a persistent lack of motivation is tied to a mental health condition such as depression . Talk to your doctor if you are feeling symptoms of apathy and low mood that last longer than two weeks.

Theories of Motivation

Throughout history, psychologists have proposed different theories to explain what motivates human behavior. The following are some of the major theories of motivation.

The instinct theory of motivation suggests that behaviors are motivated by instincts, which are fixed and inborn patterns of behavior. Psychologists such as William James, Sigmund Freud , and William McDougal have proposed several basic human drives that motivate behavior. They include biological instincts that are important for an organism's survival—such as fear, cleanliness, and love.

Drives and Needs

Many behaviors such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are motivated by biology. We have a biological need for food, water, and sleep. Therefore, we are motivated to eat, drink, and sleep. The drive reduction theory of motivation suggests that people have these basic biological drives, and our behaviors are motivated by the need to fulfill these drives.

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs is another motivation theory based on a desire to fulfill basic physiological needs. Once those needs are met, it expands to our other needs, such as those related to safety and security, social needs, self-esteem, and self-actualization.

Arousal Levels

The arousal theory of motivation suggests that people are motivated to engage in behaviors that help them maintain their optimal level of arousal. A person with low arousal needs might pursue relaxing activities such as reading a book, while those with high arousal needs might be motivated to engage in exciting, thrill-seeking behaviors such as motorcycle racing.

The Bottom Line

Psychologists have proposed many different theories of motivation . The reality is that there are numerous different forces that guide and direct our motivations.

Understanding motivation is important in many areas of life beyond psychology, from parenting to the workplace. You may want to set the best goals and establish the right reward systems to motivate others as well as to increase your own motivation .

Knowledge of motivating factors (and how to manipulate them) is used in marketing and other aspects of industrial psychology. It's an area where there are many myths, and everyone can benefit from knowing what works with motivation and what doesn't.

Nevid JS. Psychology: Concepts and Applications .

Tranquillo J, Stecker M. Using intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in continuing professional education . Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7(Suppl 7):S197-9. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.179231

Menges JI, Tussing DV, Wihler A, Grant AM. When job performance is all relative: How family motivation energizes effort and compensates for intrinsic motivation . Acad Managem J . 2016;60(2):695-719. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0898

Hockenbury DH, Hockenbury SE. Discovering Psychology .

Zhou Y, Siu AF. Motivational intensity modulates the effects of positive emotions on set shifting after controlling physiological arousal . Scand J Psychol . 2015;56(6):613-21. doi:10.1111/sjop.12247

Mystkowska-Wiertelak A, Pawlak M. Designing a tool for measuring the interrelationships between L2 WTC, confidence, beliefs, motivation, and context . Classroom-Oriented Research . 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30373-4_2

Myers DG. Exploring Social Psychology .

Siegling AB, Petrides KV. Drive: Theory and construct validation . PLoS One . 2016;11(7):e0157295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157295

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Emotion and Motivation

Introduction to Motivation

What you’ll learn to do: explain motivation, how it is influenced, and major theories about motivation.

Motivation to engage in a given behavior can come from internal and/or external factors. There are multiple theories have been put forward regarding motivation—biologically oriented theories that say the need to maintain bodily homeostasis motivates behavior, Bandura’s idea that our sense of self-efficacy motivates behavior, and others that focus on social aspects of motivation. In this section, you’ll learn about these theories as well as the famous work of Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs.

Learning Objectives

- Illustrate intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- Describe basic theories of motivation, including concepts such as instincts, drive reduction, and self-efficacy

- Explain the basic concepts associated with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Motivation. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/10-1-motivation . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- climbing picture. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://www.pexels.com/photo/achievement-action-adventure-backlit-209209/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Consumer Motivation and Involvement

14 Motivational Theories and Models

Motivations are often considered in psychology in terms of drives , which are internal states that are activated when the physiological characteristics of the body are out of balance, and goals , which are desired end states that we strive to attain. Motivation can thus be conceptualized as a series of behavioural responses that lead us to attempt to reduce drives and to attain goals by comparing our current state with a desired end state (Lawrence, Carver, & Scheier, 2002).

Drive Theory

What is the longest you’ve ever gone without eating? A couple of hours? An entire day? How did it feel? Humans rely critically on food for nutrition and energy, and the absence of food can create drastic changes, not only in physical appearance, but in thoughts and behaviours. If you’ve ever fasted for a day, you probably noticed how hunger (a form of “tension,” or “hangry” as we call it in my house) can take over your mind, directing your attention to foods you could be eating (a cheesy slice of pizza, or perhaps some cold ice cream), and motivating you to obtain and consume these foods. It’s not until you’ve eaten that your hunger begins to face and the tension you have experienced disappears.

Hunger is a drive state , an affective experience (something you feel, like the sensation of being tired or hungry) that motivates organisms to fulfill goals that are generally beneficial to their survival and reproduction. Like other drive states, such as thirst or sexual arousal, hunger has a profound impact on the functioning of the mind. It affects psychological processes, such as perception, attention, emotion, and motivation , and influences the behaviours that these processes generate.

How Food Advertising Engages Consumers

How do marketers capitalize on the tension that exists when we are hungry or thirsty? Have you ever seen an ad for a juicy steak when you’re feeling hungry? Or ice cream when it’s warm outside and you’ve just eaten dinner? Marketers both enhance our drive state (the tension we feel when we have an unmet goal or desire) through commercials and other forms of advertisements, as well as solve it by making products readily available through wide and prolific distribution systems. Thirsty? No problem, walk about 10 metres and you’re bound to find a Coke somewhere.

Food advertising both engages our senses and enhances our drive state (think: food courts at shopping malls, sample stations at Costco, Ikea’s restaurants, and farmers’ markets in the summertime) and only the savvy of marketer who exasperates the tension is also there with product ready at hand.

Homeostasis

Like a thermostat on an air conditioner, the body tries to maintain homeostasis , the natural state of the body’s systems, with goals, drives, and arousal in balance. When a drive or goal is aroused — for instance, when we are hungry — the thermostat turns on and we start to behave in a way that attempts to reduce the drive or meet the goal (in this case to seek food). As the body works toward the desired end state, the thermostat continues to check whether or not the end state has been reached. Eventually, the need or goal is satisfied (we eat), and the relevant behaviours are turned off. The body’s thermostat continues to check for homeostasis and is always ready to react to future needs.

Many homeostatic mechanisms, such as blood circulation and immune responses, are automatic and non-conscious. Others, however, involve deliberate action. Most drive states motivate action to restore homeostasis using both “ punishments ” and “ rewards .” Imagine that these homeostatic mechanisms are like molecular parents. When you behave poorly by departing from the set point (such as not eating or being somewhere too cold), they raise their voice at you. You experience this as the bad feelings, or “punishments,” of hunger, thirst, or feeling too cold or too hot. However, when you behave well (such as eating nutritious foods when hungry), these homeostatic parents reward you with the pleasure that comes from any activity that moves the system back toward the set point.

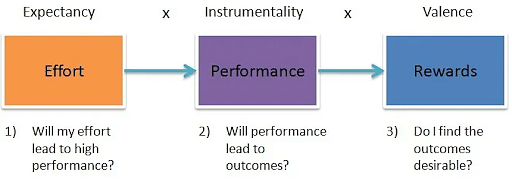

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory explains motivations much differently than drive theory. While drive theory explains why we are motivated to eat, drink, and sleep (to reduce tensions arising to unmet needs—hunger, thirst, tiredness), expectancy theory explains motivations where desirable outcomes can be achieved through our effort and performance.

According to expectancy theory , individual motivation to put forth more or less effort is determined by a rational calculation in which individuals evaluate their situation (Porter & Lawler, 1968; Vroom, 1964). According to this theory, individuals ask themselves three questions:

- Whether the person believes that high levels of effort will lead to outcomes of interest, such as performance or success. This perception is labeled expectancy . For example, do you believe that the effort you put forth in a class is related to performing well in that class? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

- The degree to which the person believes that performance is related to subsequent outcomes, such as rewards. This perception is labeled instrumentality . For example, do you believe that getting a good grade in the class is related to rewards such as getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, or from your friends or parents? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

- Finally, individuals are also concerned about the value of the rewards awaiting them as a result of performance. The anticipated satisfaction that will result from an outcome is labeled valence . For example, do you value getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, friends, or parents? If these outcomes are desirable to you, your expectancy and instrumentality is high, and you are more likely to put forth effort.

Student Op-Ed: Share a Coke, but only some of you

A consumer behaviour concept called “ expectancy theory ” can help illustrate how soft drink giant Coca-Cola (Coke) promoted class and race disparity in America. Expectancy Theory essentially explains that consumers’ decisions are driven by “positive incentives” (Solomon, White & Dahl, 2014). Choosing a certain product rather than any other alternative provides a consumer with a more positive result, like a higher social status. Coke’s marketing techniques during the time of America’s civil rights movement and during its early competition against rival Pepsi, draws a connection between a widening socio-economic class gap and consumers’ choices.

In Irene Angelico’s (1998) film, “The Cola Conquest,” we see how Coke was conceived in Atlanta, Georgia at the end of the American Civil War. To its core, the Coca-Cola company is a deeply southern company built through civil unrest. Specifically, Coke was born at a time when Black people were believed to be second-class citizens. And in their advertising, Coke used caricatures of Black people to demonstrate this belief. In Angelico’s film, Coke is described as a symbol of nationalism to the American people: for white people this meant something to be protected; for Black people it meant everything they were denied (Angelico, 1998).

Since its conception in 1886, the soda magnate has implemented an aggressive marketing strategy to capture as much of the market as possible. So when competition and copy cats came in, Coke easily pulled through with momentum they had been building for decades. At that point, consumers already associated “Coke” with being “American.” When Pepsi launched into the marketplace, arguably Coke’s biggest competitor to this day, Pepsi was branded as a second class drink. People still enjoyed Pepsi, but not in public. “Real Americans” drank Coke. Pepsi was reserved for “non-Americans” (this usually meant Black Americans).

Consumers’ decisions to choose Coke, as shown in the film, is born out of a desire to not be “othered” by friends, family, or strangers. Coke identified how the socioeconomic gap existing between classes could be leveraged as a positioning strategy to align the brand with emerging middle and upper-class Americans. Consequently, this ultimately meant a specific race too. I think it’s critical to be aware of the fact that Coke’s success came at the cost of dignity for Black Americans. I also feel that Coke, without question, operated on their collectives biases which informed their marketing: so instead of developing marketing strategies based on consumers’ needs and wants, the company was guided by historical and racial differences.

Now, when I look at advertisements I have to think more critically about the messages they are conveying: what are they telling me to think? I think the truth of the matter is that while some messages will always go over my head, I need to be aware of the fact that I won’t always have context for every marketing message put in front of me.

It’s inevitable that how I see myself is probably always going to be tied to the products that I buy. But being smart about where I spend my money and recognizing that it’s a privilege to have the freedom to choose, helps me to become a more socially responsible consumer. I think consumers need to realize that big corporations, like the Coca-Cola company, have a significant impact on shaping our cultures and that choosing a product might sometimes mean jeopardizing a whole community.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

One of the most important humanists, Abraham Maslow (1908-1970), conceptualized personality in terms of a pyramid-shaped hierarchy of motives, also called the “ Hierarchy of Needs .” At the base of the pyramid are the lowest-level motivations, including hunger and thirst, and safety and belongingness. Maslow argued that only when people are able to meet the lower-level needs are they able to move on to achieve the higher-level needs of self-esteem, and eventually self-actualization, which is the motivation to develop our innate potential to the fullest possible extent.

Motivating Consumers in a Time of Crisis

Following the economic crisis that began in 2008, the sales of new automobiles dropped sharply virtually everywhere around the world — except the sales of Hyundai vehicles. Hyundai understood that people needed to feel secure and safe and ran an ad campaign that assured car buyers they could return their vehicles if they couldn’t make the payments on them without damaging their credit. Seeing Hyundai’s success, other carmakers began offering similar programs. Likewise, banks began offering “worry-free” mortgages to ease the minds of would-be homebuyers. For a fee of about $500, First Mortgage Corp., a Texas-based bank, offered to make a homeowner’s mortgage payment for six months if he or she got laid off (Jares, 2010).

Likewise, during the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic, brands started to adopt a new line of “worry-free” messaging such as Pizza Hut’s “contact-free” delivery option for consumers living under conditions of quarantine and physical isolation.

Maslow studied how successful people, including Albert Einstein, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Helen Keller, and Mahatma Gandhi, had been able to lead such successful and productive lives. Maslow (1970) believed that self-actualized people are creative, spontaneous, and loving of themselves and others. They tend to have a few deep friendships rather than many superficial ones, and are generally private. He felt that these individuals do not need to conform to the opinions of others because they are very confident and thus free to express unpopular opinions. Self-actualized people are also likely to have peak experiences, or transcendent moments of tranquility accompanied by a strong sense of connection with others.

![Saul McLeod [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] A pyramid illustration showcasing Maslow Hierarchy of Needs.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c6/Maslow%27s_Hierarchy_of_Needs_Pyramid.png)

Maslow & Blackfoot Nation

But did you know that Maslow’s work was informed by the Blackfoot ( Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi) people? In 1943, Maslow spent several weeks performing anthropological research on Blackfoot territory, an experience that had a “powerful impact” on him (Taylor, 2019). Cindy Blackstock, an academic, child welfare activist, and member of Gitksan First Nation, along with Leroy Little Bear, an academic and researcher who founded the Native American Studies Department at the University of Lethridge (Little Bear later went on to be the founding director of the Native American Program at Harvard University) have both put forward that Maslow’s exposure to the Blackfoot people, culture, and way of life was, “instrumental in his formation of the ‘hierarchy of needs’ model'” (Leroy Little Bear, n.d.; Taylor, 2019).

According to Blackstock, Maslow’s model is “a rip-off from the Blackfoot nation”: instead of a triangle, in the Blackfoot tradition they used a tipi to depict an upward motion to the skies (Blackstock, 2014). And, while Maslow’s model places self-actualization at the top of the inverted triangle, the Blackfoot tradition identifies self-actualization as the foundation, followed by “community actualization,” then “cultural perpetuity” (Lincoln Michel, 2014). As Arley Cruthers, a Communications Instructor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University points out, in Maslow’s model self actualization represents the “pinnacle of human achievement,” whereas for the Blackfoot, self-actualization provides a foundation for greater community and cultural purpose (Cruthers, n.d.).

To see these models side-by-side and read more about their differences and how Maslow appropriated Blackfoot culture to inform his research, visit Karen Lincoln Michel’s blog post: Maslow’s hierarchy connected to Blackfoot beliefs .

These two competing models remind us how cultural context shapes consumers needs and wants.

Student Op-Ed: Coca-Cola Marketing for Maslow — Using Consumer Motivation to Create Life-Long Customers

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchical approach to motivation has been universally “adopted by marketers” (Solomon, White, & Dahl, 2015, p. 100) because it helps them to understand which level of need their target consumer is trying to meet and how to market their product to fulfill that need (Thompson, 2019). Coca-Cola (Coke) is known for its unique and innovative marketing strategies and their approach to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is no exception. Throughout history, Coke has expertly targeted every tier of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and by doing so they have created and retained dedicated life-long customers.

The first tier in Maslow’s model is physiological, or basic, needs. The consumers at this level are solely seeking to satisfy their basic survival needs, such as water and staple food items (Walker, 2017). In 1986, Roberto C. Goizueta, the Chairman and CEO of Coke at the time, is quoted saying: “Eventually the number 1 beverage on earth will not be tea, or coffee, or wine, or beer, it will be soft drinks. Our soft drinks.” (Angelico, Neidik, & Webb, 1998) proving that the company was determined to target the consumers in this motivation tier. Since then, Coca Cola has managed to convince consumers that it should be a staple in their diet, and for many, it has completely replaced water, but this was not always the case (Angelico et al., 1998).

In 1886, John Pemberton combined the healing properties of the coco leaf and the cola nut to create a drink that would eventually become Coca Cola; he originally created and marketed it as a “brain-tonic” or “cure-all elixir” (Angelico et al., 1998). Though Maslow would not be born for another 20 or so years (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019), Pemberton was inadvertently marketing his elixir to the second tier in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: safety needs; which includes health, security, and protection. According to Maslow, consumers will not be motivated by safety needs until their physiological needs have been met (Walker, 2017). While Coke is no longer regarded as a “health” drink, it still appeals to consumers motivated by safety needs because it provides them with the comforting feel of home. During WW2, one severely wounded American soldier even credited holding in his hand an empty Coke bottle for being “the only thing that kept him from dying all night long” (Angelico et al., 1998).

The motivational needs in the third tier, belonging and love, address consumers who feel their physiological and safety needs have been adequately satisfied who are now looking to spend more of their disposable income (Walker, 2017). This tier is an appealing choice for marketers (Walker, 2017), Coke included, due to the sheer volume of consumers motivated to make purchasing decisions that satisfy their social needs. Coke’s global growth strategy resulting in the brand becoming “within an arm’s reach” of the consumer at all times, combined with its air of nostalgia sentimentally depicted in advertisements featuring children and the good ol’ days, resulted in many consumers purchasing Coke as a way to fulfill their intimacy motivations (Angelico et al., 1998). “Coca Cola is your friend. Wherever you go Coca Cola is always there, it’s like coming home to mother.” (Angelico et al., 1998).

The second to final tier, self-esteem needs, generally consists of luxury brands (Walker, 2017). In modern-day Eurocentric and Western cultures, we might not consider Coke a luxury item, but its early history is rooted in social status and classism. Mid-20th century, as a feature of American culture and domestic hospitality, a host would be expected to serve friends and family Coke over Pepsi, the former regarded as a luxury and the latter regarded as a, “second-class drink” (Angelico et al., 1998).

This social tier also encompasses motivations surrounding achievement, a theme present throughout Coke’s marketing since the early days when a company hanging a Coke sign out resulted in “immediate business success” (Angelico et al., 1998). Achievement and success were also strong themes developed through the brand’s sponsorship marketing strategies, namely as a feature sponsor for Olympic events including the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta (Angelico et al., 1998) , which continue to this day.

Self-actualization needs, the final tier, addresses the motivations of consumers who have already fulfilled their needs in all of the previous tiers and now desire a sense of self-fulfillment and accomplishment (Walker, 2017). Asa Candler, who transformed Coke into the soda giant we know today, appealed to consumers—name business men at the time – in this tier by claiming “a Coca Cola taken at 8, energizes the brain ‘till 11” (Angelico et al., 1998). Candler also oversaw the creation of Coke’s iconic Normal Rockwell-style of advertisements which would catalyze 2 decades of “ads linking Coke to life’s special moments” (Angelico et al., 1998).

I believe Coke is the perfect brand to study when learning about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Being able to market to the different motivations of consumers at each level of the model cannot be easy, but I believe it is the reason Coca Cola has maintained so much success over such a long period of time. Maslow’s model teaches us that, “[c]onsumers may have different need priorities at different times and stages of their lives” (Solomon et. al, 2015, p. 101), thus by marketing to all 5 tiers, Coca Cola can essentially guarantee life-long consumers.

Media Attributions

- The image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Model is by Saul McLeod from the Creative Commons and licensed under BY-SA 4.0 .

Text Attributions

- The section on “Drive Theory” and the second paragraph under “Homeostasis” are adapted from Bhatia, S. & Loewenstein, G. (2019). “ Drive States “. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI: nobaproject.com which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- “Coca Cola Marketing for Maslow: Using Consumer Motivation to Create Life-Long Customers” is by Hartman, J. (2019) which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA .

- The introductory paragraph; first paragraph on “Homeostasis”; and, the section under “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” are adapted from Introduction to Psychology 1st Canadian Edition by Charles Stangor, Jennifer Walinga which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- The section under “Expectancy Theory” is adapted from Organisational Behaviour: Adapted for Seneca [PDF] by Dr. Melissa Warner which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- The first paragraph in the “Motivating Consumers in a Time of Crisis” is adapted from Principles of Marketing by University of Minnesota which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- “Share a Coke, but only some of you” is by Ventura, S. (2019) which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA .

Angelico, I.L. (Director). (1998). The Cola Conquest [Film]. DLI Productions.