These are the 10 biggest global health threats of the decade

Global warming and conflict zones are among the main obstacles. Image: REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic - RC186A78C7A0

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Johnny Wood

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global health.

- The WHO released the top 10 global healthcare challenges in the coming decade.

- Global warming, conflict zones and unfair healthcare provision are among the main obstacles.

- Many healthcare challenges are interconnected and will require a coordinated international effort to overcome.

- Experts are concerned governments around the world are failing to invest sufficient funds in overcoming these issues.

The world can’t afford to do nothing – that's the World Health Organization’s message on the release of its report listing the most urgent health challenges for the coming decade.

All of the health challenges on the WHO list are urgent – and many are linked. And each challenge requires a coordinated effort from the global health sector, policymakers, international agencies and communities, the organization says. However, there is concern global leaders are failing to invest enough resources in core health priorities and systems.

Have you read?

Why the 21st century's biggest health challenge is our shared responsibility, here are 3 ways ai will change healthcare by 2030, to bring universal healthcare to africa, the private sector must get involved.

These are the main challenges on the list.

1. Elevating health in the climate debate The climate crisis poses one of the biggest threats to both the planet and the health of the people who live on it.

Emissions kill around 7 million people each year, and are responsible for more than a quarter of deaths from diseases including heart attacks, stroke and lung cancer. At the same time, more – and more intense – extreme weather events like drought and floods increase malnutrition rates and help spread infectious diseases like malaria.

2. Delivering health in conflict and crisis

The already difficult task of containing disease outbreaks is made more challenging in countries rife with conflict.

Nearly 1,000 attacks on healthcare workers and medical facilities in 11 countries were recorded in 2019, leaving 193 medical staff dead. Despite stricter surveillance, many healthcare workers remain vulnerable.

For the tens of millions of people forced to flee their homes, there is often little or no access to healthcare.

3. Making healthcare fairer

The gap between the haves and have-nots is growing, especially in terms of access to healthcare.

People in wealthy nations can expect to live 18 years longer than their poorer neighbours, and wealth can determine access to healthcare within countries and individual cities, as well. Rising global rates of diseases like cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory conditions have a greater impact on low- and middle-income countries, where medical bills can quickly deplete the limited resources of poorer families.

4. Expanding access to medicines Although many in the world take access to medication for granted, medicines and vaccines are not an option for almost one-third of the global population.

The challenge of expanding access to medicines in areas where few, if any, healthcare products are available includes combatting substandard and imitation medical products . In addition to putting lives at risk by failing to treat the patient’s condition, these products can undermine confidence in medicines and healthcare providers.

5. Stopping infectious diseases

Infectious diseases continue to kill millions of people, most of them poor. This picture looks unlikely to change in the near future.

Preventing the spread of diseases like HIV, tuberculosis and malaria depends on sufficient levels of funding and robust healthcare systems. But in some areas where they are most needed, these resources are in short supply.

Greater funding and political will is required to develop immunization programmes, share data on disease outbreaks and reduce the effects of drug resistance.

6. Preparing for epidemics

Airborne viruses or diseases transferred by mosquito bite can spread quickly, with potentially devastating consequences.

Currently, more time and resources are spent reacting to a new strain of influenza or an outbreak of yellow fever, rather than preparing for future outbreaks. But it’s not a question of if a dangerous virus will come about – but when.

Epidemics are a huge threat to health and the economy: the vast spread of disease can literally destroy societies.

In 2017, at our Annual Meeting, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was launched – bringing together experts from government, business, health, academia and civil society to accelerate the development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases and to enable access to them during outbreaks.

Our world needs stronger, unified responses to major health threats. By creating alliances and coalitions like CEPI, which involve expertise, funding and other support, we are able to collectively address the most pressing global health challenges.

Is your organisation interested in working with the World Economic Forum to tackle global health issues? Find out more here .

7. Protecting people from dangerous products

Many poorer parts of the world face malnutrition and food insecurity, while at the same time, global obesity levels and diet-related problems are on the rise. We need to rethink what we eat, reduce the consumption of food and drinks high in sugar, salt and harmful fats, and promote healthy, sustainable diets. To this end, the WHO is working with countries to develop policies that reduce our reliance on harmful foodstuffs.

Health workers are in short supply the world over. Sustainable health and social care systems depend on well-paid and properly trained staff who can deliver quality care. WHO research predicts that by 2030, there will be a shortfall of 18 million health workers, mostly in low- and middle-income countries.

New investment is needed to properly train health workers and provide decent salaries for people in the profession, it says.

9. Keeping adolescents safe

Every year, more than 1 million adolescents – aged between 10 and 19 – die. The main causes include road accidents, suicides, domestic violence and diseases like HIV or lower respiratory conditions. But many of these premature deaths are preventable. Policymakers, educators and health practitioners need to promote positive mental health among adolescents, to prevent illicit drug use, alcohol abuse and self harm. Programmes that raise awareness of things like contraception, sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy care help address some of the underlying causes of adolescent fatalities.

10. Earning public trust Delivering safe, reliable healthcare to patients involves first gaining their confidence and trust; a trust which can be undermined by the rapid spread of misinformation on social media. For example, the anti-vaccination movement has led to an increase in deaths from preventable diseases. But social media can also be used to spread reliable information and build public trust in healthcare. Community programmes are another way to boost confidence in healthcare provision and practices that prevent the spread of diseases, such as vaccinations or condom use.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How midwife mentors are making it safer for women to give birth in remote, fragile areas

Anna Cecilia Frellsen

May 9, 2024

From Athens to Dhaka: how chief heat officers are battling the heat

Angeli Mehta

May 8, 2024

How a pair of reading glasses could increase your income

Emma Charlton

Nigeria is rolling out Men5CV, a ‘revolutionary’ meningitis vaccine

5 conditions that highlight the women’s health gap

Kate Whiting

May 3, 2024

How philanthropy is empowering India's mental health sector

Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

May 2, 2024

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Cover Archive

- IDSA Guidelines

- IDSA Journals

- The Journal of Infectious Diseases

- Open Forum Infectious Diseases

- Photo Quizzes

- State-of-the-Art Reviews

- Voices of ID

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Journals Career Network

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- About Clinical Infectious Diseases

- About the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About the HIV Medicine Association

- IDSA COI Policy

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- For Reviewers

- For Press Offices

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The scope of the problem, emerging and reemerging infections, infectious causes of chronic diseases, bioterrorism, the science base for infectious diseases in the 21st century, vaccinology in the 21st century, global health, acknowledgment, infectious diseases: considerations for the 21st century.

This article is a shortened and edited version of an address delivered at the 38th annual meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, held in New Orleans on 7–10 September 2000.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Anthony S. Fauci, Infectious Diseases: Considerations for the 21st Century, Clinical Infectious Diseases , Volume 32, Issue 5, 1 March 2001, Pages 675–685, https://doi.org/10.1086/319235

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The discipline of infectious diseases will assume added prominence in the 21st century in both developed and developing nations. To an unprecedented extent, issues related to infectious diseases in the context of global health are on the agendas of world leaders, health policymakers, and philanthropies. This attention has focused both on scientific challenges such as vaccine development and on the deleterious effects of infectious diseases on economic development and political stability. Interest in global health has led to increasing levels of financial support, which, combined with recent technological advances, provide extraordinary opportunities for infectious disease research in the 21st century. The sequencing of human and microbial genomes and advances in functional genomics will underpin significant progress in many areas, including understanding human predisposition and susceptibility to disease, microbial pathogenesis, and the development new diagnostics, vaccines, and therapies. Increasingly, infectious disease research will be linked to the development of the medical infrastructure and training needed in developing countries to translate scientific advances into operational reality.

The history of the medical discipline of infectious diseases is rich in extraordinary accomplishments that have had a major impact on humankind [ 1 ]. The successful diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of a wide array of infectious diseases has altered the very fabric of society, providing important social, economic and political benefits.

In considering the importance of infectious diseases globally as well as in the United States in these first years of the 21st century, I reflect back to December 1967, when then-Surgeon General William H. Stewart, contemplating the benefits realized from antibiotics and vaccines, declared victory against the threat of infectious diseases and suggested that our nation turn its attention and resources to the more important threat of chronic diseases [ 2 ]. At the time, I was completing my residency training in internal medicine at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center and anticipating my move to Bethesda, Maryland, to begin my infectious diseases fellowship at the National Institutes of Health. I became concerned that I was entering a subspecialty of clinical medicine and an area of biomedical research that was disappearing at the same time that I was training for it. However, the history of infectious diseases from that time in my training until the present day has proven quite the opposite. At the dawn of the 21st century, the future of infectious diseases and its impact on societies throughout the world is strikingly apparent. It is this future that I will address herein.

Infectious diseases are the second leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years worldwide (1 disability-adjusted life year is 1 lost year of healthy life) and the third leading cause of death in the United States [ 3 , 4 ]. Among these infectious diseases causing death worldwide, acute lower respiratory tract infections, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal diseases, tuberculosis, and malaria predominate ( table 1 ). Clearly, despite earlier predictions to the contrary [ 2 ], infectious diseases remain a dominant feature of domestic and international public health considerations for the 21st century. In fact, the continual evolution of emerging and reemerging diseases, particularly the acceleration of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in developing countries, will heighten the global impact of infectious diseases in this century.

Leading infectious causes of death worldwide, 1999.

The extent of the global burden of infectious diseases depends on the already established incidences and prevalences of known infections together with the constant, but uneven, flow of emerging and reemerging infections [ 5–8 ]. Emerging infections are those that have not been previously recognized. The AIDS pandemic is a prototypical example of a truly new and emerging infectious disease whose public health impact had not been previously experienced. Reemerging infections have been experienced previously but have reappeared in a more virulent form or in a new epidemiological setting. The influenza A pandemics of 1918, 1957, and 1968 are prototypical examples of reemerging infections [ 9 ].

HIV/AIDS . Despite the fact that the HIV/AIDS pandemic exacted a terrible toll in deaths and human suffering in the last 2 decades of the 20th century, the full impact of this disease will be realized in the 21st century. As of the end of 2000, there were 36 million people worldwide living with HIV infection; >90% of them live in developing countries, and 70% live in southern Africa [ 6 ]. There have been ∼22 million cumulative deaths due to AIDS. In certain countries in Africa, such as Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Swaziland, 25%–35% of the adult population (ages 15–49 years) are infected with HIV [ 10 ]. In South Africa, it is estimated that there are >4 million people infected with HIV, ∼10% of the entire population and 20% of the adult population. The life expectancy in several southern African countries has decreased dramatically because of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, negating the impressive gains that had been made over the previous few decades.

India and other southern and southeastern Asian countries will be the next epicenters of the HIV/AIDS pandemic; the cultural and socioeconomic conditions in those countries are unfortunately well-suited to explosive spread of this infection [ 10 ]. Indeed, it is estimated that ∼4 million people in India are already infected with HIV. The potential for catastrophic spread in this country of >1 billion people is enormous, as it is for China, the most populous nation in the world. Aggressive and sustained AIDS prevention programs are critical to contain the epidemic in these Asian countries.

The continual evolution of infectious diseases . In addition to HIV/AIDS and pandemic influenza [ 10 ], which have had an extraordinary impact on global health, there is a continual evolution of a wide range of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases with varying potentials for global spread. Figure 1 illustrates some salient examples of emerging and reemerging infections throughout the world in recent years. Some, such as Ebola virus and Nipah virus, have been highly virulent but have involved relatively small numbers of people, have remained tightly restricted in their spread, and so have been more medical curiosities than global public health threats. Others, such as multidrug-resistant malaria, have involved large numbers of people but have, because of the demography of the infection, remained for the most part geographically restricted. This has resulted in a serious situation in the region involved but not a global public health threat. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and enterococci are examples of emerging infections that do not immediately involve large numbers of persons but that will ultimately have a serious impact on public health throughout the world [ 8 ].

Range and recognized site(s) of origin of variety of emerging and reemerging infections. v-CJD, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; E. coli, Escherichia coli .

Two examples of recently reemerging infections that are currently causing considerable concern in the United States are dengue and West Nile fever. Dengue has posed an extraordinary problem in Brazil, with >530,000 cases reported in 1998 [ 11 ]. In addition, other nations in South and Central America and the Caribbean have varying degrees of problems with dengue. Dengue has appeared infrequently in the United States since the 1940s. However, it remains a threat because the mosquito vectors for dengue are widely dispersed in the United States, particularly in the states bordering the Gulf of Mexico. Indeed, in 1999, 17 locally acquired cases of dengue were reported in Texas (Gubler D, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, personal communication). In contrast, West Nile fever had never been seen in the United States before 1999, when there were 62 cases and 7 deaths identified in the New York City area [ 12 ]. West Nile fever is caused by a flavivirus that is transmitted by mosquitoes, with a variety of birds serving as intermediate hosts. It is indigenous to the region of the West Nile River (hence its name) and is seen commonly in Middle Eastern countries such as Israel. The virus survived the winter of 1999–2000 in the United States; in 2000, 18 human cases (including 1 death) and numerous infections in various avian and mammalian species were reported in the summer and early fall. Infected birds were identified along the eastern seaboard as far south as North Carolina [ 13 ]. Here again, the major vector for this virus (the Culex pipiens mosquito) is widely dispersed throughout the eastern part of the country. It is unclear how serious West Nile fever will turn out to be in the United States; however, it is clearly a new infectious diseases problem that must be dealt with, and it illustrates the constant threat of reemergence of old diseases in new epidemiological settings.

No discussion of the threat of reemerging infectious diseases in the 21st century would be complete without mention of the threat of yet another catastrophic influenza A epidemic. In an average year, influenza A is responsible for ∼20,000 excess deaths in the United States [ 14 ]. During the influenza A pandemic of 1918, there were at least 20 million deaths worldwide and >500,000 deaths in the United States. In 1957, the second most deadly influenza A epidemic occurred, accounting for ∼70,000 deaths in the United States. In 1968, the third most important influenza epidemic occurred, accounting for ∼35,000–40,000 deaths. Thus, serious influenza epidemics occur about every 20–40 years. The appearance of bird-to-human transmission of H5N1 influenza A virus in Hong Kong in the winter of 1997–1998 [ 15 ] was a cogent reminder of the ever-present threat of a new strain of influenza A virus entering a population that is relatively naïve for the microbe in question. Most public heath experts agree that it is only a matter of time before another catastrophic influenza epidemic occurs, and it certainly will occur in the 21st century.

Antimicrobial resistance . The development of resistance of microbes to antimicrobial drugs has been a problem in medicine since the use of the very first antimicrobial agents. Unfortunately, this problem has worsened, in part because of the widespread and often inappropriate use of antimicrobials [ 16 ]. In this first decade of the 21st century, we are faced with this continuing threat on a wider scale than ever before, with the emergence of resistant strains of a number of important microbes, including pneumococci, enterococci, staphylococci, Plasmodium falciparum, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Furthermore, despite the extraordinary success of antiretroviral drugs in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the development of viral resistance is a major problem in the management of HIV-infected persons. Strategies to contain antimicrobial resistance in these early years of the 21st century should include heightened surveillance; appropriate infection control programs, particularly in hospitals; promotion of the rational use of antimicrobials; and accelerated basic and applied research in the areas of microbial pathogenesis, improved diagnostics, and vaccine and drug development. The recent sequencing of the genomes of important pathogens (see below, “The pathogens”) will provide novel opportunities to delineate more precisely the genetic basis for resistance, as has been accomplished with P. falciparum and chloroquine resistance [ 17 ]. Such information will greatly facilitate the development of alternative therapies against resistant strains of microbes.

During the second half of the 20th century, a number of chronic diseases not thought to be associated with microbial infections were shown to be directly caused by or indirectly resulting from infectious microbes [ 18–20 ]. Table 2 provides a partial list of chronic diseases whose etiologies have proven to be infectious. Perhaps the most dramatic example has been the recent proof that Helicobacter pylori is directly responsible for most peptic ulcer disease as well as gastric carcinoma. Also of considerable interest and importance is the relationship between hepatitis B and/or C virus and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as the strong association of certain strains of human papillomavirus with cervical, vulvar, and anal carcinoma. These associations have potentially important implications for the use of vaccination to prevent microbe-associated cancers. In this regard, the successful use of hepatitis B vaccine has already resulted in a decrease in the incidence of hepatic cancers in certain populations [ 21 ]. Indeed, the association of infectious diseases with cancer is striking; it is estimated that ∼16% of all cancers are directly or indirectly associated with a microbial agent ( figure 2 ) [ 22 ].

Examples of chronic diseases that have infectious etiologies.

Infectious causes of cancer, based on data from [ 22 ]. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HHV, human herpesvirus; HTLV, human T lymphotropic virus.

A bioterrorism attack against the civilian population in the United States is inevitable in the 21st century [ 23 , 24 ]. The only question is which agent(s) will be used and under what circumstances will the attack(s) occur.

The threat of bioterrorism underscores the importance of pathogen genome sequencing projects, because rapid diagnostics will be critical to an adequate response to an attack. The availability of genomic sequences of microbes likely to be used in a bioterrorism attack will allow for the development of gene chips for sensitive, rapid, and accurate diagnosis [ 24 , 25 ]. In addition, it is likely that microbes used for bioterrorism will be genetically modified for antimicrobial resistance. Understanding the genetic basis of resistance will greatly facilitate the development of alternative antimicrobials. Depending on the microorganism used in the bioterrorism attack, vaccines may be effective in protecting substantial numbers of the population after initiation of the attack, as would be the case with an agent such as smallpox. Hence, the development of new and improved vaccines against smallpox and similar agents, as well as the stockpiling of antimicrobials against such agents, will be important components of the effort against bioterrorism in the coming decades.

Critical to our ability to meet the challenges of infectious diseases in the 21st century is the continual and rapid evolution of the scientific and technological advances that serve as the foundation for the response of the public health enterprise to established, emerging, and reemerging diseases ( table 3 ) [ 26 ]. For the discipline of infectious diseases, the application of functional genomics and proteomics will be a critical component of this science base and will draw from the sequencing not only of the human genome but also of a wide array of microbial pathogens. The areas of synthetic chemistry and robotics will greatly facilitate drug design and high-throughput screening of potential antimicrobial candidates. Computer and mathematical modeling likewise will prove useful in drug design and will also provide predictive models of microbial transmission. The field of molecular epidemiology will allow more precise delineation of microbial transmission and virulence patterns. Genetic epidemiology will lead to greater insights into host susceptibility at the individual and population levels. Finally, the rapidly advancing field of information technology will have a great impact on the field of infectious diseases in the 21st century, because rapid access and exchange of information among developed and developing nations will be critical to the overall success of any global health program.

Science base for infectious diseases research in 21st century.

The pathogens . Although we have entered the 21st century armed with an ever-expanding array of technological advances to meet the current and future challenges of microbial pathogens, the microbial world is extraordinarily diverse and possesses an adaptive capacity that in many respects matches our technological capabilities [ 5–8 , 27–29 ]. Microbes are an important part of the external and internal environment of the human species. Indeed, microbial species constitute ∼60% of the Earth's biomass, but <0.5% of the estimated 2–3 billion microbial species have been identified [ 27–29 ]. Microbes preceded animals and plants on Earth by >3 billion years, and although only a minute fraction of all microbial species are real or potential pathogens for the human host, these pathogens continue to emerge and reemerge.

One of the most important recent technological advances in infectious diseases research has been the ability to rapidly sequence the entire genome of microbial pathogens [ 29 ]. This capability will be a critical component of 21st century strategies for the development of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines against currently recognized as well as emerging pathogens. Indeed, the microbial genome sequencing project will likely have as great an impact on the field of infectious diseases as the human genome project will on the entire field of medicine, including infectious diseases.

The first sequence of a human pathogen was obtained for Haemophilus influenzae in 1995 [ 30 ]. Subsequently, the pace of microbial genome sequencing has been extraordinary. As of January 2001, the sequencing of ∼50 microbial genomes had been completed [ 31 ]. It is projected that within 2–4 years, the complete sequencing of an additional 100 microbial species will be available. Table 4 provides a partial list of some of the important human pathogenic microbial species for which genomic sequences have been published. The ability to sequence and perform sequence analysis rapidly on microbial species has resulted from the development and application of novel sequencing and computational techniques. The bold and successful application of the whole-genome “shotgun” sequencing technique used to determine the complete genome sequence of H. influenzae has revolutionized the field of genome sequencing ( figure 3 ) [ 29 ].

Examples of important human pathogens for which complete genomic sequences have been published.

Steps in a whole-genome sequencing project. A “shotgun” sequencing strategy for whole-genome analysis is based on construction of a random cloned DNA library from the microbe in question, followed by sequencing of DNA clones, followed by the assembly of sequences, closing of gaps, editing of sequences, and finally annotation or assignment of function. Adapted from [ 29 ] (with permission).

The real and potential advantages of a microbial genomics approach to diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines are already being realized despite the fact that only ∼50% of the genes of already sequenced microbes have tentatively assigned functions [ 29 ]. When the functions of the remaining 50% of genes of these microbes become known, it is likely that some proportion of these will provide medically applicable insights. Determination of the function of these genes should assume a high priority in the post-sequencing, functional genomics era of the first decade of the 21st century.

The host: the human genome project and infectious diseases . The discipline of infectious diseases is centered around the study of the microbes, the host, or the interaction between the two. The completion of a working draft of the sequence of the entire human genome [ 32 , 33 ] and the subsequent assignment of function to the 30,000–40,000 human genes, which is projected to occur over a period of several years, will have an enormous impact on the entire field of medicine [ 34 ]. This will clearly be the case in the discipline of infectious diseases, as well as that of immunology, a large component of which represents the host response to invading microbes. The ability to examine across the entire human genome the expression of the full menu of host factors involved in the response to a microbial pathogen will provide unprecedented opportunities to understand disease pathogenesis. The cascade of gene expressions involved in the response of the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system [ 35 ] to an invading microbe will clarify the important relationship between these two essential components of host defenses. The feasibility of identifying and assigning function to the entire array of soluble factors (cytokines) and their receptors, together with the relevant signal transduction pathways associated with the host response to pathogens, will truly revolutionize the field of host defense mechanisms.

Before the availability of the sequence of the human genome and the continuing assignment of specific functions to all genes, the recognition of the association of identifiable phenotypes with genetic polymorphisms was often a chance event and was relatively restricted in its scope. In the future, the study of gene polymorphisms and their role in host-microbe interactions will assume a new dimension in the era of human genomics. Polymorphisms are variations in DNA sequence, and most are single-nucleotide polymorphisms [ 36 ]. Certainly, only a small fraction of single-nucleotide polymorphisms might be relevant to host defenses; however, this small degree of difference would still play a potential role in the susceptibility to certain infectious agents at the individual and population levels. In addition, genetic polymorphisms will be identified that determine responses to certain drugs, including antibiotics [ 36 ]. The availability of gene chips or microarrays will enable us to scan the entire human genome for relevant polymorphisms.

The availability of sequences of the entire genomes of non-human species that have a considerable degree of homology with humans will greatly facilitate the task of assigning function to the human genes as they are identified. Species such as the mouse, rat, zebrafish, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, among others, whose genomes have and will be sequenced will serve as invaluable tools for experimentation on the function of a wide array of genes [ 37 , 38 ]. Among these will surely be a variety of genes whose expression is directly or indirectly involved in host defense mechanisms against pathogenic microbes. Thus, the era of genomics will affect the study of infectious diseases from a number of standpoints, including the availability of the genomic sequences of the microbes in question, the human host species, and a variety of animal species that will serve as models for experimentation and delineation of pathogenic processes associated with infection by microbial pathogens.

The impact of vaccinology on the public health in the 20th century has been enormous. Without question, vaccines have been our most powerful tools for preventing disease, disability, and death and controlling health care costs [ 39–42 ]. The evolution of the field of vaccinology has been driven by the development of enabling technologies, such as detoxification methodologies, the use of a variety of tissue culture systems to propagate microbes, and the new biotechnology of the last quarter of the 20th century, particularly that of recombinant DNA. The use of the currently available and future technologies in the 21st century promises to provide a renaissance in an already vital field. As mentioned above, the availability of the annotated sequences of the entire genomes of virtually all of the microbial pathogens will allow for the identification of a wide array of new antigens for vaccine targets. In the 21st century, vaccines derived from microbial genome-based expression of candidate antigens will be widely used. In addition to the traditional live attenuated and whole killed vaccines, concepts that are currently being actively pursued are recombinant proteins, conjugated vaccines, pseudovirions, replicons, vectored vaccines, “naked” DNA vaccines, microencapsulated vaccines, and edible vaccines [ 43 ].

One of the important challenges for the 21st century is the development of safe and effective vaccines for the 3 greatest microbial killers worldwide: HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. These 3 diseases account for one-third to one-half of healthy years lost in less developed countries [ 3 ]. They have become the target of a proposed Millennium Vaccine Initiative [ 44 ] and were addressed in the communiqué from a summit of 8 major industrialized nations (G8) held in Okinawa in July 2000, which stated the goal of substantially reducing the burden of these 3 diseases by the year 2010 [ 45 ] (see below).

Despite the enormous successes of vaccines in decreasing the burden of morbidity and mortality caused by a variety of pathogens worldwide, continual frustration has resulted from the fact there are still millions of deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases worldwide ( table 5 ) [ 46 ]. This is largely caused by the failure to implement vaccine delivery programs in a number of developing countries. As advanced technologies allow for the development of new vaccines against microbes for which no vaccines currently exist and improved vaccines against microbes for which a vaccine currently does exist, it is imperative that a vigorous effort is mounted to assure the delivery of such vaccines for the populations at risk.

Global mortality from major vaccine-preventable diseases.

Global health has long been a subject of intense interest and an area of commitment for a relatively small proportion of the biomedical research and public health communities in the United States. Over the past decade, this interest has become more universal and will become even more intensified in the 21st century. Although humanitarian concerns alone should have spurred such an interest, it was other factors that precipitated an acceleration of involvement in global health issues. The globalization of our economy has led to an unprecedented dependence on the economic and political stability of our trading partners [ 47 , 48 ]. The economic and political stability of a nation is heavily influenced by the general health of that nation. The AIDS epidemic in less developed countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, is a cogent example of this tenet; the same can be said for countries with a high prevalence of endemic malaria, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases, and a wide range of parasitic diseases [ 47 , 48 ].

The globalization of health problems and their relevance to the United States have been brought emphatically to the attention of the American public with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although first recognized in the United States, HIV/AIDS is now predominantly a disease of developing countries [ 9 ]. The scientific and public health response to HIV/AIDS in the United Sates, to which I will refer as “the AIDS model,” provides important scientific and policy lessons that should be considered in our approach to other diseases of high global health impact.

The AIDS model . There have been >750,000 reported cases of AIDS in the United States and >430,000 deaths [ 49 ]. Despite dramatic decreases in the infection rate, the number of new infections has plateaued at an unacceptably high level of 40,000 per year since the early 1990s [ 50 ]. Nonetheless, the importance and speed of research advances that have been made since the disease was first recognized in the summer of 1981 have been breathtaking and unprecedented [ 51 ]. Within 3 years of recognition of this new disease, the etiologic agent was identified and causality proven. A simple and accurate diagnostic test was available for screening blood donors and populations in general. Pathogenic mechanisms of HIV disease have been extensively delineated. There are currently 17 antiretroviral drugs available for the treatment of HIV disease, and these together with earlier and better treatment and prophylaxis of opportunistic diseases has led to a striking decrease in the AIDS-related death rate over the past 5 years [ 52 , 53 ] ( figure 4 ). Many of these drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration with unprecedented speed. Furthermore, a number of vaccine candidates are in various stages of clinical trials [ 54 ]. Government and private organizations mobilized quickly and effectively for the care of HIV-infected persons. Education and behavioral modification efforts have contributed to considerable progress in the prevention of HIV infection, although continued and heightened vigilance is essential, because the successes with therapy have led to an unfortunate increase in risky behavior among certain groups, such as young men who have sex with men [ 55 ].

Death rates from leading causes of death in persons aged 25–44 years, United States, 1983–1998 [ 53 ]

These striking advances would not have occurred without the extraordinary investment in resources for biomedical research at the National Institutes of Health ( figure 5 ). In addition, major investments have been made in the public health arenas of education, behavioral modification, prevention measures, and care of HIV-infected persons. In fiscal year 2000, US Department of Health and Human Services funding for AIDS research and services exceeded $8.5 billion [ 56 ]. These investments were made possible only by the consistent bipartisan commitment of several administrations and congresses to support such endeavors. The paradigm was highly successful: a major domestic public health problem was met with a major investment of public resources, and the results in the United States and other industrialized nations were striking. However, in the last few years of the 20th century, it became apparent that the toll in suffering and death from HIV/AIDS in developing nations was enormous and dwarfed that in the United States. HIV/AIDS had evolved into a true global health catastrophe. Furthermore, the global impact of AIDS began to call greater attention to the fact that other diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis ( table 6 ), had been having a similar impact in developing nations for centuries. Indeed, in certain countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the “big three” of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis account for ⩾50% of all deaths [ 3 ]. Compared with HIV/AIDS, relatively few research and public health resources were committed to these latter diseases by the United States and other developed nations. The question arises whether we can accomplish in malaria and tuberculosis research what has been accomplished in AIDS research. Almost certainly an infusion of dollars into malaria and tuberculosis research, analogous to the “AIDS model,” would yield advances similar to those associated with HIV/AIDS research. Obviously, effective vaccines for all 3 of these diseases would be the ultimate accomplishment of a heightened research effort and would have an enormous impact on global health. However, implementation of such advances would be extremely problematic in many developing nations under the current economic conditions and with the lack of adequate health care infrastructure. In a different era, this would have been seen as an insurmountable problem, or at least someone else's problem. Today, however, global health problems, particularly those related to infectious diseases, are beginning to be perceived by political leaders in the United States and in other nations as a threat to destabilize the world [ 57 ].

Funding at National Institutes of Health for HIV/AIDS research. Est., estimated (Office of Financial Management, National Institutes of Health, personal communication).

Global burden of 3 diseases.

Global health as a foreign policy issue . For the first time in the history of the United States, global infectious diseases are being viewed in the context of foreign policy. In January 2000, HIV/AIDS was discussed by the Security Council of the United Nations [ 57 ], and in April 2000, the White House formally designated HIV/AIDS as a threat to the national security of the United States in that it could potentially contribute to the fall of foreign governments, touch off ethnic wars, and undo decades of work in building free-market democracies abroad [ 58 ]. As noted above, a Millennium Vaccine Initiative targeting HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis for vaccine development and delivery has been proposed [ 44 ]. In addition, a number of legislative proposals have been put forth in the US Congress relating to varying forms of assistance in the development and delivery of vaccines and therapeutics that would benefit developing nations [ 57 ]. Other developed nations are also expressing renewed awareness of the implication of global health issues. At a meeting of the G8 nations in Okinawa in July 2000, a communiqué was issued stating that “infectious and parasitic diseases, most notably HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, as well as childhood diseases and common infections, threaten to reverse decades of development and to rob an entire generation of hope for a better future.” It also established goals to reduce the number of infections and deaths caused by HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis by 25%–50% by the year 2010 [ 45 ]. Philanthropic organizations are investing billions of dollars to assist developing countries in the promotion of health [ 59 ].

It is noteworthy that the area of science that contributed most obviously to foreign policy in the 20th century was the physical sciences related to nuclear weapons, the cold war, and the race for space exploration [ 60 ]. It appears that the growing forces of globalization together with the fact that the health of nations is critical for economic and political stability will lead to an increasing appreciation in the 21st century of the role of biological sciences and global health, particularly with regard to infectious diseases, in the development and execution of foreign policy.

The 21st century will see an ever-increasing emphasis on infectious diseases, both because of the certainty that emerging and reemerging diseases will continue to challenge us and because globalization has led to an increased awareness of and commitment to addressing the terrible burden of infectious diseases in developing nations. Indeed, global health with an emphasis on infectious diseases is gradually assuming an important role in the foreign policy agenda of the United States and other developed nations. Clearly, the anxiety that I felt in 1968 as I traveled to the NIH for my infectious diseases fellowship because of the proclamation by the then-Surgeon General of the United States, that infectious diseases were no longer a problem, has been replaced by a realization of the enormity of the infectious diseases challenges that lie ahead in the 21st century and beyond.

I thank Gregory Folkers for helpful discussions and for invaluable assistance in collecting materials.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Author notes

- communicable diseases

- developing countries

- world health

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1537-6591

- Print ISSN 1058-4838

- Copyright © 2024 Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

Global Health: Priority Agenda for the 21st Century

About the author, haile t. debas.

At the core of the United Nations Millennium Declaration of 2000 are the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for 2015, which recognize that global health is a priority agenda for the twenty-first century. Achieving the MDGs is essential for world peace and economic stability, and for addressing the critical issues of human rights, equality, and equity. Never in human history have people of different national and geographic origins been as interdependent as in the twenty-first century. Globalization and the degree and speed of human mobility have created circumstances under which the health concerns of poor countries are de facto concerns of rich countries. These considerations, and others to be discussed below, emphasize the centrality of the MDGs in an interdependent world. Global health and the global economy are intricately linked. In its 1995 report, the Commission of Global Governance stated: "As economies become more interdependent, it is not only the opportunity for wealth creation that is multiplied, but also the opportunity for destabilizing shocks to be transmitted from one country to another." Pandemics are a perfect example of such "destabilizing shocks". The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome epidemic of 2003 brought the vibrant Hong Kong economy rapidly to its knees, reducing consumption of goods, tourism, and air travel.1 It is expected that an avian influenza pandemic would cause much worse economic and social dislocation worldwide, with a potential impact of $2 trillion to $3 trillion on the world economy and the loss of tens of millions of lives.2 But the linkage between global health and the global economy goes beyond the effect of pandemics. The global market economy is increasingly dependent on a healthy, productive global workforce, especially since the thirty member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development move much of their manufacturing and service industries to low- and middle-income countries. Even as we strive to achieve the MDGs by 2015, the heightened attention and greater public and private investment in global health in recent years is paying dividends. As documented by the Living Proof Project of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, child mortality decreased by 27 per cent between 1990 and 2007.3, 4 Despite earlier gloomy assumptions, maternal mortality has dropped by 35 per cent over the past twenty-eight years -- an encouraging progress towards achieving MDG 55 on improving maternal health. The immunization programme of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation is credited with preventing an estimated 3.4 million deaths in the past decade.6 The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief is estimated to have saved 1.2 million lives.7 By 2008, about 3 million people were receiving anti-retroviral drugs.8 Similarly, thanks to the combined efforts of the Global Fund and the US President's Malaria Initiative, malaria prevention and treatment services have been significantly expanded. Since 2000, reported malaria cases and/or deaths have declined by at least half in twenty-five countries around the world.9 This is all good news -- and there is more of it. Nevertheless, global health faces several great challenges. Most sub-Saharan countries will not achieve the MDGs. One important reason for this is the lack of functional health systems due to a shortage in the health workforce, management incompetence, inadequate infrastructure, and health care financing. The World Health Report 2006 estimates a global deficit of 2.3 million doctors, nurses, and midwives. Critical health workforce shortages exist in fifty-seven countries, of which thirty-seven are in sub-Saharan Africa. It is hard to see how these countries can possibly achieve those MDGs relating to health. Emphasis on vertical or disease-specific programmes such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis may have further weakened the already fractured health systems, thus making delivery of general health care in low-income countries that much more difficult. Unfortunately, neither the governments of these countries nor the global donor community have invested adequately in capacity building. There are more challenges facing global health. Prominent among these are the development of microbial resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants, along with the prevalence, in epidemic proportions, of non-communicable diseases and injuries in low- and middle-income countries. Tackling these challenges is also a priority agenda for global health in the twenty-first century. Several important questions beg for answers: Is the generous aid given by the donor community to poor countries optimally utilized? How do we balance investment in technological solutions with those in capacity building? Have we adequately engaged all the available talent pool to solve the complex problems in global health? In response to the last question, I believe the expertise of academic institutions in both poor and rich countries has been inadequately tapped. Effective collaborations among governments, non-governmental agencies, and academia will be key to addressing the health workforce crisis and to training the leadership that health care requires. An important global health priority agenda for the twenty-first century is achieving the MDGs. Unfortunately, many of the low-income countries are unlikely to achieve these goals, primarily because of critical shortages of health workers and weak health care systems. Beyond the achievement of the MDGs, other priority agenda items are developing effective vaccines and drugs for HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases, addressing microbial resistance, and preparing a worldwide coordinated response to inevitable pandemics. A balanced funding strategy for vaccine and drug discovery on the one hand, and capacity building on the other, will determine how well and how fast we will achieve the MDGs and address the other global health priorities for the twenty-first century.

1 A.K.F. Siu, Y.C.R. Wong, "Economic Impact of SARS: The Case of Hong Kong", Asian Economic Papers 3:1, MIT Press, (2004): pp.62-83. 2 M.T. Osterholm, "Preparing for the next pandemic". N Engl J Med. (2005) May 5;352(18): 1839-42 3 United Nations Population Division: http://esa.un.org/unpp/ 4 D. You, T. Wardlaw, P. Salama, G. Jones, "Levels and trends in under-5 mortality, 1990 -- 2008". The Lancet, Published online September 10, 2009, DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61601-9 5 M. C Hogan, K. J Foreman, M. Naghavi, S. Y. Ahn, M. Wang, S. M. Makela, A. D. Lopez, R. Lozano, C. J. L. Murray, "Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5", The Lancet, Early Online Publication, April 12, 2010,DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1 6 GAVI Alliance Global Results: http://www.gavialliance.org/performance/global_results/index.php 7 E. Bendavid, J. Bhattacharya, "The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in Africa: An Evaluation of Outcomes", Annals of Internal Medicine, May 19 (2009), vol. 150 no. 10 688-695 8 Celebrating Life: The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief 2009 Annual Report to Congress. http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/113827.pdf 9 WHO, World Malaria Report, September 2008: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563697_eng.pdf

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Thirty Years On, Leaders Need to Recommit to the International Conference on Population and Development Agenda

With the gains from the Cairo conference now in peril, the population and development framework is more relevant than ever. At the end of April 2024, countries will convene to review the progress made on the ICPD agenda during the annual session of the Commission on Population and Development.

The LDC Future Forum: Accelerating the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Least Developed Countries

The desired outcome of the LDC Future Forums is the dissemination of practical and evidence-based case studies, solutions and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable development.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 15 November 2022

Medicine and health of 21st Century: Not just a high biotech-driven solution

- Mourad Assidi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2750-1764 1 , 2 ,

- Abdelbaset Buhmeida 1 &

- Bruce Budowle ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4116-2930 3

npj Genomic Medicine volume 7 , Article number: 67 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5703 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

- Molecular medicine

- Quality of life

Many biotechnological innovations have shaped the contemporary healthcare system (CHS) with significant progress to treat or cure several acute conditions and diseases of known causes (particularly infectious, trauma). Some have been successful while others have created additional health care challenges. For example, a reliance on drugs has not been a panacea to meet the challenges related to multifactorial noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)—the main health burden of the 21st century. In contrast, the advent of omics-based and big data technologies has raised global hope to predict, treat, and/or cure NCDs, effectively fight even the current COVID-19 pandemic, and improve overall healthcare outcomes. Although this digital revolution has introduced extensive changes on all aspects of contemporary society, economy, firms, job market, and healthcare management, it is facing and will face several intrinsic and extrinsic challenges, impacting precision medicine implementation, costs, possible outcomes, and managing expectations. With all of biotechnology’s exciting promises, biological systems’ complexity, unfortunately, continues to be underestimated since it cannot readily be compartmentalized as an independent and segregated set of problems, and therefore is, in a number of situations, not readily mimicable by the current algorithm-building proficiency tools. Although the potential of biotechnology is motivating, we should not lose sight of approaches that may not seem as glamorous but can have large impacts on the healthcare of many and across disparate population groups. A balanced approach of “omics and big data” solution in CHS along with a large scale, simpler, and suitable strategies should be defined with expectations properly managed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Axes of a revolution: challenges and promises of big data in healthcare

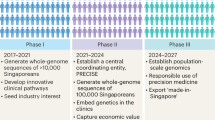

The Singapore National Precision Medicine Strategy

Strategic vision for improving human health at The Forefront of Genomics

Historical context of over-reliance on biotechnology-driven treatments.

The contemporary healthcare system (CHS) has been shaped by century-long innovations and discoveries made notably in the late 1800s and early 1900s 1 . To achieve the ultimate goal of allowing people to live longer and healthier, scientists and clinicians, among others, have made remarkable efforts to continuously enhance the CHS, which has improved the lives of nearly every person on the planet, although not necessarily equally (i.e., there are disparity issues that need to be addressed). While preventive healthcare is practiced by some, CHS is mainly a reactive approach strategy that often waits until the person becomes ill with acute symptoms to undertake a specific surgical intervention and/or a drug-based corrective action.

The “magic bullet” era

Drug therapy began centuries ago with the use of plant extracts and progressively evolved into the development of purified and targeted materials for a wide range of health-related applications, such as morphine (1803), anesthetics (1840s), antipyretics, and analgesics (1870s) in the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, Ehrlich’s research laid the foundations for drug screening and discovery by bridging the gap between chemistry, biology, and medicine. His research discovered one of the first “magic bullets”—the antisyphilitic drug Arsphenamine. Other treatments for other diseases were subsequently discovered, including insulin, penicillin, and chemotherapy 2 , 3 . Pharmacological research expanded significantly to develop new cures and ameliorative approaches for various diseases with many noted successes. Consequently, the proportion of patents and newly-developed pharmaceutical products increased from 25% of all pharmacy remedies in the 1940s to nearly 90% at the end of 20th century 2 . Based on the realized health benefits of drug therapy, there has become an enormous reliance on drug prescriptions and unprecedented levels of use 4 . With the rapid economic development and enhanced living standards since the end of World War II, the use of drugs has steadily increased, boosted in part by the support of insurance and social security systems.

Through marketing and lobbying adopted by pharmaceutical companies to continuously expand their markets and benefits 5 , a major bias has taken root in the public and healthcare providers’ mindset and culture: treatment of disease primarily is achieved through prescription of drugs with a concomitant (and unfortunate) lower reliance on prevention and health promotion 6 , 7 . This reliance on drug therapies has made their use varied and commonplace 4 , although some treatments have become cost prohibitive for the majority of the population contributing to healthcare disparity. The pushing of drug therapy without an appreciation of the human factor has seen a concomitant increase in patients suffering medication (ab)use and/or iatrogenic effects. Many individuals over 65 years of age in the Western world take anywhere between 5 to more than 20 drugs per day 4 , 8 , 9 . Moreover, most of these drugs are palliative treatments; for example, in the USA, 9 out of 10 prescribed drugs are pain killers and symptom relievers 10 . This drug reliance strategy has been associated with unprecedented waste in annual global healthcare expenditures due to overspending, unnecessary prescriptions, mistakes, and corruption costing upwards of USD 300 billion (according to the European Healthcare Fraud and Corruption Network) 11 . The epidemic opioids crisis in the USA is an example of drug (ab)use due to the underestimation of the neurobiological harm and the potential addiction effects mainly on individuals/groups with particular social vulnerabilities 12 , 13 . This crisis is a heavy public health burden that begets severe health, socioeconomic and legal consequences 12 .

Other challenges of the “drug-only” solution

This “drug solution” problem, in turn, is exacerbated with new challenges related to availability, accessibility, affordability, safety and effectiveness 11 . Beyond the heavy financial burden of healthcare commodification and, more importantly, drug interactions and side effects—due to both polypharmacy and inappropriate prescriptions—have led to frailty, severe comorbidities, higher hospital admissions, and increased mortality 14 . Similar issues can be seen with other hopeful cures such as vaccine access to immunize the population suffering from the current pandemic. While rather elegant biotechnology-based solutions have been undertaken to rapidly develop SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (experiencing the fastest development of an approved vaccine(s) in history), the roll out and access to the vaccine to all population groups, as well as willingness by some to receive it, has been far more challenging 15 , 16 , 17 . One would have thought that the logistics for dissemination could have been planned better 18 , 19 . Innovation and cost of vaccine purchase were not impediments but instead, a more basic distribution strategy(ies) and information dissemination should have been implemented. A well-planned distribution strategy reduces the virus reservoir, impacts the greater population, and reduces health disparities.

Despite the considerable budget allocated to drug discovery, pharmacogenomics, and high biotechnology, these fields have substantial bottlenecks in CHS, as they have high rates of failure. These failures were in part due to instrumentation, methods, statistics, computational power, machine learning, etc. that were not able to accommodate, organize, and process the information needed to provide more precise solutions. In the USA, 90% of new drug applications to the FDA are rejected because of a lack of efficacy and/or toxicity 20 . Moreover, among the most prescribed drugs in the USA, the most successful one was reported to be effective in only 25% of patients 21 . This “imprecision medicine” is mostly due to the complexity of human biology systems, inappropriate or limited settings during, for example, the drug development process, and/or the inability of a specific drug to fix multi-level molecular perturbations. Omics solutions will help in predicting those patients in which a positive effect will occur and which patients who will have no effect or adverse reactions to the treatment. Because one can foresee drug development will be targeted to only those individuals with a positive effect, the cost will continue to rise, and likely health disparity will be further exacerbated.

Advancements in biotechnology to improve human health

The promise of omics and big data sciences.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the completion of the human genome project (HGP) provided a blueprint map towards precision medicine (PM) with a promise to improve quality of life. The first deciphered blueprint in itself had little impact. However, the HGP fostered biotechnology innovation and advances in bioinformatics, such as exquisite massively parallel sequencing technologies turning the herculean effort of sequencing an entire human genome into a reasonable cost and trivial exercise today. Boosted by digital analytics, the HGP has metamorphosed the way life science research is conceived and applied. Subsequently, several new disciplines have emerged, such as biobanking, bioinformatics, comparative genomics, pharmacogenomics, clinical genomics, and projects such as the human proteome project, the human microbiome project, the cancer genome atlas project, and the illuminating druggable genome program, to name a few. Furthermore, the emergence of the digital revolution has been progressively introducing extensive changes on all aspects of contemporary society, economy, firms, and job market 22 . This huge impact has also encompassed the way science and research are conducted in every discipline 23 . In medicine, mega sets of sequence and metagenomic data, super-libraries of medical images, and complex drug databases are generated on a massive scale. These huge data sets are clear illustrations of a new complex, automated and data-driven trend to gain insights about both the clinical profiles and molecular signatures in health and disease statuses 24 , 25 , 26 . Experts estimate that innovations, such as omics biotechnologies mainly integrative personal omics profile (iPOP) 27 , connected health systems, wireless wearable devices, blockchain technology, the Internet of Things (IoT), health tokens, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) are promising ways to address CHS’s challenges 28 , 29 , 30 (Table 1 ).

With the advent of these omics-based biotechnologies (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) and big data science, a new wave of hope has spread over the scientific and clinical communities as well as the general public, in search of instant, individualized, and accurate theranostics 31 . There are and will be CHS improvements at both the individual and population levels in NCDs and infectious diseases. While omics undoubtedly will impact positively precision medicine 32 , it is important not to lose focus that individualized solutions that can be leveraged to affect population level challenges still will provide the greatest improvement in CHS. One of the main outcomes of deciphering cancer using omics technologies was targeted therapies. In fact, targeted anticancer therapy (TAT) is an expanding area that revolutionized cancer treatment modalities and significantly improved prognosis, treatment, and prediction of several malignancies 33 , 34 . Furthermore, TATs have played a major role in converting several cancers from fatal diseases to manageable chronic conditions 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 . However, these TATs-induced improvements were lacking enough specificity and effectiveness. The wide genomic instability and tumor heterogeneity marked by myriad possible multi-mutations precludes any hope for precision treatments 33 . Therefore, TATs were often combined with the other treatment modalities as surgery, chemo, radio, hormonal therapy, and even other targeted therapies. So far, the developed TATs were not able to overcome the toxicity, and cross-reactivity on nontarget tissues, relapse, and drug resistance 37 . Notably, only a small proportion of the population benefits from TATs at a higher cost. Therefore, it is obvious that a “magic bullet” solution for cancer treatment is still unreachable.

Noteworthy, of five health determinants (genome and biology, lifestyle choices, social circumstances, environment, and healthcare system), medical care’s contribution does not exceed 11% of each individual’s health 39 , 40 . This means that 89% of one’s health is impacted by determinants outside of the CHS realm. Thus, more emphasis on the remaining health determinants will substantially improve CHS’s performance. A tendency to marginalize prevention and health promotion—perhaps due to its unprofitability character or its lack of glamour or lack of insurance support—has impeded more focus on implementation of health quality pillars and adequate prevention strategies.

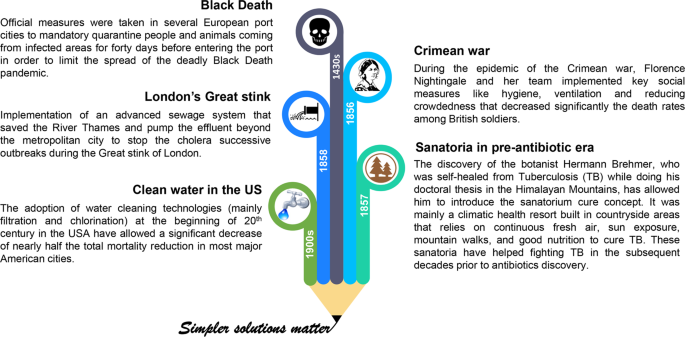

For instance, half of all deaths in the U.S. were due to behavioral causes 41 and therefore may be preventable. These health-related behaviors, which are only part of the problem, were mainly driven/influenced by social determinants as education, employment, and income 41 , 42 . Another illustration of the cost-effective and global impact of the health determinants outside the healthcare realm were the findings of McKeown who demonstrated that the sharp increases in life expectancy at the 19th century in the UK was mainly triggered by the improved living conditions, such as nutrition, sanitation, and potable water availability, decades ahead of the discovery of antibiotics, vaccines, and intensive care units 41 , 43 . Strikingly, more than 75% of healthcare spending in rich countries is dedicated to managing lifestyle-induced conditions. However, it is estimated that 80% of these NCDs are preventable by readily and cost-effective lifestyle choices improvements 44 . Taken together, these findings highlight that CHS effectiveness could not be enhanced by high-tech-driven inputs only but must consider the other health determinants as the foundation of any future reform.

Although better insights and resolution about diseases’ diagnoses and stratification, as well as healthcare management, can be observed given their descriptive character 45 , the digital revolution impact on precision therapeutics may not be realized readily, except for applications such as rapid vaccine development, robotic surgery, detection of unknown pathogens, disease monitoring and predicting adverse drug reactions to name a few. The new and unprecedented challenges are related to big data and biospecimens’ collection, storage, sharing, analysis, reliability, reproducibility, interpretation, governance, and bioethics that have emerged, with accompanying logistics requirements and considerations 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 . The PM concept at this post-genomic era—although inspirational—remains costly with limited success for population level impact at least in the short and medium term 50 . We are not advocating a reduced effort in this regard but managing expectations should become part of the strategy and more so not to lose sight of alternate not as “newsworthy” strategies that may have greater outreach to improving healthcare disparity and quality.

Biology: inconceivable complexity nevertheless user-friendly

Human biology is a multi-layered complexity of dynamic and interactive networks at the single-cell, multicellular, tissue, organ, system, organismal, environmental as well as social levels. In this context, NCDs are a series of perturbations of afore described complex networks that are deeply rooted in the biology, lifestyle choices, and the engineered/devised environment in which we live today. Given its appearance as user-friendly, biology complexity continues to be, unfortunately, underestimated. While the HGP and the ensuing development of omics solutions have lofty goals, the problem of molecular complexity has been underestimated, and deciphering the genotype-phenotype relationship continues to plague reaching the “magic bullet” goal 51 . For example, Singh and Gupta point out that the unanticipated necessary and unnecessary complexity of molecular machinery and systems in conjunction with evolutionary processes make it extremely difficult, currently, to apply PM effectively. An organism’s genetic redundancy and multiple molecular pathways are complex, related, and integrated and they also affect traits and thus complicate interpretation. It should not be surprising that individuals with similar risk factors for a disease may have different phenotypes 52 , 53 . Genetic backgrounds, gene interaction networks, environments, and histories impact PM making it “uncertain, chance-ridden, and probabilistic” 52 .

The scientific community should be aware that these biological systems could not be compartmentalized as independent and segregated problems in the digital and molecular realm, and therefore are very challenging to be mimicable by the current digital tools. Although impressive strides have been made with the advent of customized artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms that analyze the complexity of these still poorly understood biological networks, they likely will not achieve the status of the “magic bullet” solution in the near future. There is a need for education and training of algorithm-building proficiency experts—a fundamental part of the roll out of advance technological solutions that has not been a major focus of national or global strategies. Perhaps computer science or better yet bioinformatics should become a requisite course in the secondary school system or at least part of an undergraduate curriculum for all students.