Guide on How to Write a Reflection Paper with Free Tips and Example

A reflection paper is a very common type of paper among college students. Almost any subject you enroll in requires you to express your opinion on certain matters. In this article, we will explain how to write a reflection paper and provide examples and useful tips to make the essay writing process easier.

Reflection papers should have an academic tone yet be personal and subjective. In this paper, you should analyze and reflect upon how an experience, academic task, article, or lecture shaped your perception and thoughts on a subject.

Here is what you need to know about writing an effective critical reflection paper. Stick around until the end of our guide to get some useful writing tips from the writing team at EssayPro — a research paper writing service

What Is a Reflection Paper

A reflection paper is a type of paper that requires you to write your opinion on a topic, supporting it with your observations and personal experiences. As opposed to presenting your reader with the views of other academics and writers, in this essay, you get an opportunity to write your point of view—and the best part is that there is no wrong answer. It is YOUR opinion, and it is your job to express your thoughts in a manner that will be understandable and clear for all readers that will read your paper. The topic range is endless. Here are some examples: whether or not you think aliens exist, your favorite TV show, or your opinion on the outcome of WWII. You can write about pretty much anything.

There are three types of reflection paper; depending on which one you end up with, the tone you write with can be slightly different. The first type is the educational reflective paper. Here your job is to write feedback about a book, movie, or seminar you attended—in a manner that teaches the reader about it. The second is the professional paper. Usually, it is written by people who study or work in education or psychology. For example, it can be a reflection of someone’s behavior. And the last is the personal type, which explores your thoughts and feelings about an individual subject.

However, reflection paper writing will stop eventually with one very important final paper to write - your resume. This is where you will need to reflect on your entire life leading up to that moment. To learn how to list education on resume perfectly, follow the link on our dissertation writing services .

Unlock the potential of your thoughts with EssayPro . Order a reflection paper and explore a range of other academic services tailored to your needs. Dive deep into your experiences, analyze them with expert guidance, and turn your insights into an impactful reflection paper.

Free Reflection Paper Example

Now that we went over all of the essentials about a reflection paper and how to approach it, we would like to show you some examples that will definitely help you with getting started on your paper.

Reflection Paper Format

Reflection papers typically do not follow any specific format. Since it is your opinion, professors usually let you handle them in any comfortable way. It is best to write your thoughts freely, without guideline constraints. If a personal reflection paper was assigned to you, the format of your paper might depend on the criteria set by your professor. College reflection papers (also known as reflection essays) can typically range from about 400-800 words in length.

Here’s how we can suggest you format your reflection paper:

How to Start a Reflection Paper

The first thing to do when beginning to work on a reflection essay is to read your article thoroughly while taking notes. Whether you are reflecting on, for example, an activity, book/newspaper, or academic essay, you want to highlight key ideas and concepts.

You can start writing your reflection paper by summarizing the main concept of your notes to see if your essay includes all the information needed for your readers. It is helpful to add charts, diagrams, and lists to deliver your ideas to the audience in a better fashion.

After you have finished reading your article, it’s time to brainstorm. We’ve got a simple brainstorming technique for writing reflection papers. Just answer some of the basic questions below:

- How did the article affect you?

- How does this article catch the reader’s attention (or does it all)?

- Has the article changed your mind about something? If so, explain how.

- Has the article left you with any questions?

- Were there any unaddressed critical issues that didn’t appear in the article?

- Does the article relate to anything from your past reading experiences?

- Does the article agree with any of your past reading experiences?

Here are some reflection paper topic examples for you to keep in mind before preparing to write your own:

- How my views on rap music have changed over time

- My reflection and interpretation of Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Why my theory about the size of the universe has changed over time

- How my observations for clinical psychological studies have developed in the last year

The result of your brainstorming should be a written outline of the contents of your future paper. Do not skip this step, as it will ensure that your essay will have a proper flow and appropriate organization.

Another good way to organize your ideas is to write them down in a 3-column chart or table.

Do you want your task look awesome?

If you would like your reflection paper to look professional, feel free to check out one of our articles on how to format MLA, APA or Chicago style

Writing a Reflection Paper Outline

Reflection paper should contain few key elements:

Introduction

Your introduction should specify what you’re reflecting upon. Make sure that your thesis informs your reader about your general position, or opinion, toward your subject.

- State what you are analyzing: a passage, a lecture, an academic article, an experience, etc...)

- Briefly summarize the work.

- Write a thesis statement stating how your subject has affected you.

One way you can start your thesis is to write:

Example: “After reading/experiencing (your chosen topic), I gained the knowledge of…”

Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs should examine your ideas and experiences in context to your topic. Make sure each new body paragraph starts with a topic sentence.

Your reflection may include quotes and passages if you are writing about a book or an academic paper. They give your reader a point of reference to fully understand your feedback. Feel free to describe what you saw, what you heard, and how you felt.

Example: “I saw many people participating in our weight experiment. The atmosphere felt nervous yet inspiring. I was amazed by the excitement of the event.”

As with any conclusion, you should summarize what you’ve learned from the experience. Next, tell the reader how your newfound knowledge has affected your understanding of the subject in general. Finally, describe the feeling and overall lesson you had from the reading or experience.

There are a few good ways to conclude a reflection paper:

- Tie all the ideas from your body paragraphs together, and generalize the major insights you’ve experienced.

- Restate your thesis and summarize the content of your paper.

We have a separate blog post dedicated to writing a great conclusion. Be sure to check it out for an in-depth look at how to make a good final impression on your reader.

Need a hand? Get help from our writers. Edit, proofread or buy essay .

How to Write a Reflection Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: create a main theme.

After you choose your topic, write a short summary about what you have learned about your experience with that topic. Then, let readers know how you feel about your case — and be honest. Chances are that your readers will likely be able to relate to your opinion or at least the way you form your perspective, which will help them better understand your reflection.

For example: After watching a TEDx episode on Wim Hof, I was able to reevaluate my preconceived notions about the negative effects of cold exposure.

Step 2: Brainstorm Ideas and Experiences You’ve Had Related to Your Topic

You can write down specific quotes, predispositions you have, things that influenced you, or anything memorable. Be personal and explain, in simple words, how you felt.

For example: • A lot of people think that even a small amount of carbohydrates will make people gain weight • A specific moment when I struggled with an excess weight where I avoided carbohydrates entirely • The consequences of my actions that gave rise to my research • The evidence and studies of nutritional science that claim carbohydrates alone are to blame for making people obese • My new experience with having a healthy diet with a well-balanced intake of nutrients • The influence of other people’s perceptions on the harm of carbohydrates, and the role their influence has had on me • New ideas I’ve created as a result of my shift in perspective

Step 3: Analyze How and Why These Ideas and Experiences Have Affected Your Interpretation of Your Theme

Pick an idea or experience you had from the last step, and analyze it further. Then, write your reasoning for agreeing or disagreeing with it.

For example, Idea: I was raised to think that carbohydrates make people gain weight.

Analysis: Most people think that if they eat any carbohydrates, such as bread, cereal, and sugar, they will gain weight. I believe in this misconception to such a great extent that I avoided carbohydrates entirely. As a result, my blood glucose levels were very low. I needed to do a lot of research to overcome my beliefs finally. Afterward, I adopted the philosophy of “everything in moderation” as a key to a healthy lifestyle.

For example: Idea: I was brought up to think that carbohydrates make people gain weight. Analysis: Most people think that if they eat any carbohydrates, such as bread, cereal, and sugar, they will gain weight. I believe in this misconception to such a great extent that I avoided carbohydrates entirely. As a result, my blood glucose levels were very low. I needed to do a lot of my own research to finally overcome my beliefs. After, I adopted the philosophy of “everything in moderation” as a key for having a healthy lifestyle.

Step 4: Make Connections Between Your Observations, Experiences, and Opinions

Try to connect your ideas and insights to form a cohesive picture for your theme. You can also try to recognize and break down your assumptions, which you may challenge in the future.

There are some subjects for reflection papers that are most commonly written about. They include:

- Book – Start by writing some information about the author’s biography and summarize the plot—without revealing the ending to keep your readers interested. Make sure to include the names of the characters, the main themes, and any issues mentioned in the book. Finally, express your thoughts and reflect on the book itself.

- Course – Including the course name and description is a good place to start. Then, you can write about the course flow, explain why you took this course, and tell readers what you learned from it. Since it is a reflection paper, express your opinion, supporting it with examples from the course.

- Project – The structure for a reflection paper about a project has identical guidelines to that of a course. One of the things you might want to add would be the pros and cons of the course. Also, mention some changes you might want to see, and evaluate how relevant the skills you acquired are to real life.

- Interview – First, introduce the person and briefly mention the discussion. Touch on the main points, controversies, and your opinion of that person.

Writing Tips

Everyone has their style of writing a reflective essay – and that's the beauty of it; you have plenty of leeway with this type of paper – but there are still a few tips everyone should incorporate.

Before you start your piece, read some examples of other papers; they will likely help you better understand what they are and how to approach yours. When picking your subject, try to write about something unusual and memorable — it is more likely to capture your readers' attention. Never write the whole essay at once. Space out the time slots when you work on your reflection paper to at least a day apart. This will allow your brain to generate new thoughts and reflections.

- Short and Sweet – Most reflection papers are between 250 and 750 words. Don't go off on tangents. Only include relevant information.

- Clear and Concise – Make your paper as clear and concise as possible. Use a strong thesis statement so your essay can follow it with the same strength.

- Maintain the Right Tone – Use a professional and academic tone—even though the writing is personal.

- Cite Your Sources – Try to cite authoritative sources and experts to back up your personal opinions.

- Proofreading – Not only should you proofread for spelling and grammatical errors, but you should proofread to focus on your organization as well. Answer the question presented in the introduction.

'If only someone could write my essay !' you may think. Ask for help our professional writers in case you need it.

Do You Need a Well-Written Reflection Paper?

Then send us your assignment requirements and we'll get it done in no time.

How To Write A Reflection Paper?

How to start a reflection paper, how long should a reflection paper be, related articles.

.webp)

- Study Guides

- Homework Questions

Memory Reflection Paper (19) (1)

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

6 Tips to Writing a Solid Reflection Paper (With a Sample Essay)

A reflection paper is an essay that focuses on your personal thoughts related to an experience, topic, or behavior. It can veer toward educational as a reflection of a book you've read or something you've been studying in class. It can also take a more professional slant as you reflect on a certain profession or your experiences within that profession.

A lot of students enjoy writing this type of essay, especially if they find it easy to discuss their feelings and experiences related to a topic or profession. However, some students find this type of subjective writing to be difficult and would rather a more objective writing assignment.

Whether you're the former or the latter, for this article, we're going to look at 6 tips for writing a solid reflection paper that will help you get through the outlining and writing processes. We've also provided a sample reflection paper so you can see these tips in action.

Tip #1—Choose a topic you're passionate about

However you choose to focus your reflection paper, if you're able to choose your own topic, choose one that is highly interesting to you or that you find important. You'll find that your paper will be much easier to outline and draft if you do. There are a range of potential topics that have been used or have the potential of turning into a great reflection paper. Here are a few suggestions:

- Describe your internship experience.

- Discuss a recent book you read that changed you.

- What is "family" to you and why?

- What are some of the qualities demonstrated by your favorite employers and/or managers? What makes them your favorite?

- Discuss music that has altered your way of thinking or made you see the world from a different perspective.

- Reflect on your favorite memory of a pet or loved one.

Tip #2—Outline your reflection paper before you write

Be sure to outline your reflection paper first before you start to write. Even though this sort of essay is written as a personal reflection, you'll still need to make sure you stay on topic and organize your writing in a clear, logical way. As with other traditional essays, there should be an introduction with a thesis statement, a body, and a conclusion. Each paragraph within your body should focus on a different sub-topic within the scope of your overall topic.

Tip #3—Write in first-person singular

Write in first-person singular. Format the essay according to your teacher's instructions, using whatever citation style required. Your teacher will likely request that it is double-spaced, with 1" indentation in each margin, in 12 pt. font. Also keep in mind that most reflection papers will be around 750 words or less.

Tip #4—Avoid too much description

Avoiding adding too much description of events. This is not the kind of essay where you need to discuss a play-by-play of everything that happens. Rather, it is the kind of essay that focuses on your reflection of the topic and how you felt during these experiences.

Tip #5—Avoid colloquial expressions or slang

Avoid colloquial expressions or slang—this is still an academic assignment. Also, be sure to edit your essay thoroughly for any grammar or spelling mistakes. Since a reflection paper is written in first-person point of view, it's easy to mistake it for an informal essay and skip the editing. Regardless of the type of essay you submit to your professor, it should always be edited and error-free.

Tip #6—Critical reflection goes deeper

If your assignment asks you to write a critical reflection paper, it is asking for your observations and evaluations regarding an experience. You'll need to provide an in-depth analysis of the subject and your experience with it in an academic context. You might also provide a summary, if the critical reflection paper is about a book or article you've read.

Sample reflection paper

My student teaching experience with the Master's in Education program has been a great learning opportunity. Although I was nervous at first, it didn't take long to apply lessons I have been learning in my academic program to real-world skills such as classroom management, lesson planning, and instruction.

During my first week of student teaching, I was assigned a mentor who had been teaching middle school grades for over 12 years. She assured me that middle school is one of the most difficult grades to teach and that there is a high turnover rate of teachers, which worried me. However, once the week got started and I began to meet the students, my fears abated. These young people were funny, inquisitive, and eager to begin reading the assigned book, Lord of the Flies —especially after we started with a group project scenario that included kids being stranded on an island without adults.

The first few weeks of applying classroom management skills I had read about in my Master's program were a definite learning experience. I had read enough about adolescent development to know that they were not yet at the age where they were able to control all of their impulses, so there were moments when some would yell out an answer or speak without raising their hand first. So, at my mentor's suggestion, I worked with the students to create their own classroom rules that everyone would agree to abide by. Since they played a role in coming up with these rules, I believe it helped them take more personal responsibility in following them.

When we finished that initial group project, I began to see how tasks such as lesson planning—and plans that have to be turned in to the administration weekly—can easily become overwhelming if not worked out on the front-end of the semester. My mentor explained that most seasoned teachers will work on their lesson plans over the summer, using the proper state curriculum, to have them ready with the school year begins. Having scrambled to get my lesson planning done in time during the first few weeks, I saw the value in this and agreed with her that summertime preparation makes the most logical sense. When the school year gets started, it's really a whirlwind of activities, professional development and other events that make it really difficult to find the time to plan lessons.

Once the semester got well underway and I had lesson planning worked out with as little stress as possible, I was able to focus more on instructional time, which I found to be incredibly exciting. I began to see how incorporating multiple learning styles into my lesson, including visual, auditory and kinesthetic learning styles, helped the students stay more actively engaged in the discussion. They also enjoyed it when I showed them short video clips of the movie versions of the books we were reading, as well as the free-write sessions where they were able to write a scene and perform it with their classmates.

Finally, my student teaching experience taught me that above all else, I have truly found my "calling" in teaching. Every day was something new and there was never a dull moment—not when you're teaching a group of 30 teenagers! This lack of boredom and the things I learned from the students are two of the most positive things for me that resulted from the experience, and I can't wait to have my own classroom in the fall when the school year begins again.

Related Posts

The Ecological Fallacy: Look Before You Leap

How to Write About Negative (Or Null) Results in Academic Research

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Memory Writing Prompts: Dive into Reflective Narratives

My name is Debbie, and I am passionate about developing a love for the written word and planting a seed that will grow into a powerful voice that can inspire many.

What are Memory Writing Prompts?

How memory writing prompts can deepen reflective narratives, the benefits of engaging with memory writing prompts, how to use memory writing prompts to spark reflective writing, memory writing prompts for reflective writing, examples of memory writing prompts to get started, tips for crafting compelling reflective narratives using memory writing prompts, enhancing self-reflection through regular memory writing practice, frequently asked questions, in conclusion.

Memory writing prompts are thought-provoking cues designed to help you access and explore the depths of your memories. As human beings, our minds store a vast amount of experiences and emotions that shape who we are. These prompts serve as triggers, sparking our recollection and allowing us to delve into our past.

Whether you’re looking to preserve cherished moments, ignite your creativity, or simply explore your own personal narrative, memory writing prompts can be a valuable tool. They can help you unlock forgotten memories, unearth details long lost, and provide a space for self-reflection.

- Memory writing prompts encourage introspection and self-discovery.

- They offer an opportunity to explore personal anecdotes, moments of growth, or life-changing events.

- Using these prompts can enhance storytelling abilities and writing skills, allowing you to express yourself more vividly on paper.

So, whenever you feel stuck or want to embark on a journey through your own memories, try out these prompts. They can take various forms, ranging from questions about significant individuals in your life to nostalgic descriptions of special places. Let your memories flow and allow your writing to capture the essence of your experiences.

Memory writing prompts offer a powerful tool to enhance the depth and richness of your reflective narratives. By tapping into personal memories and experiences, these prompts encourage you to delve into the nuances of life, adding layers of authenticity and emotional connection to your writing. Whether you are a seasoned writer or just starting to explore the art of storytelling, memory prompts can ignite your creativity and bring your narratives to life.

One of the key benefits of using memory prompts is their ability to activate vivid details and sensory imagery. By prompting you to recall specific moments or emotions from your past, these prompts help you re-engage with your memories on a deeper level. As you write about these experiences, you naturally begin to incorporate sensory language, painting a more vivid picture for your readers. This not only creates a more engaging narrative but also allows your audience to better connect with your story on an emotional level.

Furthermore, memory prompts provide a framework for introspection and self-reflection. Through intentional writing exercises, you can explore the meaning and significance of past events, gaining new insights and understanding. When you revisit your memories and connect them to your current thoughts and emotions, you invite a deeper level of self-awareness and personal growth. Additionally, the act of writing about your memories can offer catharsis and healing, allowing you to process and make sense of challenging or transformative experiences.

Incorporating memory writing prompts into your writing practice can be a transformative experience. By accessing your personal memories and infusing them into your narratives, you can enrich your storytelling, uncover new perspectives, and foster self-growth. So, grab your pen, choose a memory prompt, and prepare to embark on a captivating journey of self-discovery through reflective narratives.

Memory writing prompts offer an incredible opportunity to unlock a treasure trove of forgotten memories and enrich our lives in numerous ways. Whether you’re seeking therapeutic benefits or a creative outlet, engaging with these prompts can bring about positive changes in your overall well-being. Here are some of the key advantages of incorporating memory writing prompts into your daily routine:

- Self-reflection and personal growth: Writing about our memories is a powerful tool for self-reflection. It allows us to revisit past experiences, analyze them from a new perspective, and gain insights into our own personal growth. Reflecting on our memories helps us better understand our emotions, behaviors, and thought processes.

- Preservation of personal history: Our memories make up the fabric of who we are. By engaging with memory writing prompts, we can capture our life stories, preserving them for future generations. These written accounts provide a valuable legacy that helps our loved ones understand the depth and richness of our lives.

- Improved mental well-being: Writing about memories has therapeutic benefits, aiding in the processing of emotions and stress reduction. Engaging with writing prompts can be cathartic, allowing us to release pent-up feelings and gain a sense of closure. Additionally, writing stimulates our cognitive functions, improving memory recall and overall mental acuity.

Incorporating memory writing prompts into your daily routine can be an enlightening and fulfilling experience. By delving into your past, you can uncover hidden facets of your identity, gain new perspectives, and find solace in revisiting long-forgotten experiences. So grab a pen, find a quiet space, and let the power of memory writing prompts guide you on a transformative journey of self-discovery and reflection!

Reflective writing allows us to explore our memories, thoughts, and experiences in a meaningful way. It enables us to gain insights, process emotions, and gain a deeper understanding of ourselves. Memory writing prompts can be a powerful tool to ignite this reflective process. Here are some tips on how to effectively use memory writing prompts to spark your reflective writing:

- Select meaningful prompts: Choose memory writing prompts that resonate with you personally. Whether it’s a specific event, a significant person, or a place that holds special memories, pick prompts that evoke emotions and offer opportunities for self-reflection.

- Create a safe and comfortable writing space: Find a quiet place where you can write without distractions. Make sure you have a comfortable chair, good lighting, and all the tools you need to jot down your thoughts. Creating a cozy and relaxed writing environment can help you delve deeper into your reflections.

- Set aside dedicated time: Reflective writing requires time and focus. Dedicate a specific time slot each day or week to engage in this practice. Whether it’s early morning when your mind is fresh or before bed when you can unwind, find a time that works best for you, and stick to it.

By using memory writing prompts, we embark on a journey of self-discovery, enabling us to gain insights, find closure, and even heal emotional wounds. Reflective writing serves as a medium to express ourselves, understand our experiences better, and ultimately grow as individuals. So, grab your pen and paper, or open up a blank document, and let your memories guide you towards a deeper level of self-reflection and understanding.

Memory writing is a powerful tool that helps us revisit our past experiences and create a meaningful narrative. If you’re looking to get started with memory writing, here are some unique and creative prompts to spark your imagination:

- A Childhood Adventure: Recall an exciting adventure from your childhood. Describe the sights, sounds, and emotions you experienced during this memorable moment.

- A Special Relationship: Write about a person who has had a significant impact on your life. Share anecdotes, experiences, and lessons learned from this unique relationship.

- A Place of Solitude: Take yourself back to a place where you found peace and tranquility. Describe the setting, the sensations it evoked, and the emotions you felt in that moment.

Furthermore, you can explore writing prompts like:

- A Life-Changing Decision: Reflect on a decision that altered the course of your life. Explain the factors that influenced your choice and how it has shaped you into the person you are today.

- A Hilarious Mishap: Recount a funny incident from your life that still brings a smile to your face. Share the details, the unexpected twists, and the comedic value of this unforgettable event.

- A Lesson from Nature: Connect with the natural world and recount a moment where you learned a valuable lesson from the elements around you. Describe the setting, the lesson learned, and how it impacted your perspective.

These prompts are meant to ignite your memory and unlock a treasure trove of stories within. Remember, every memory holds significance, no matter how small or insignificant it may seem at first glance. Happy writing!

Reflective narratives can be powerful tools for self-reflection and personal growth. By using memory writing prompts, you can tap into your past experiences and delve deep into cherished memories or significant events. Here are some tips to help you craft compelling narratives that will captivate your readers and evoke genuine emotions:

1. Identify a memorable prompt: The first step is to choose a memory writing prompt that resonates with you. It could be a specific question about a significant milestone, a challenging moment, or a joyful memory. Select a prompt that sparks your interest and ignites your passion to explore further.

2. Bring your memory to life: Once you’ve selected a memory prompt, it’s time to immerse your readers in the experience. Use descriptive language to paint a vivid picture and engage their senses. You want your readers to feel like they are present in the moment with you. Be specific and precise in your descriptions, focusing on sights, sounds, smells, and even the way you felt physically and emotionally.

3. Reflect on the significance: A compelling reflective narrative goes beyond simply recounting an event; it dives into the deeper meaning behind it. Take the time to reflect on how this memory has impacted your life, changed your perspective, or influenced your decisions. Share your insights and lessons learned, allowing your readers to connect with your personal growth journey.

4. Be honest and vulnerable: Authenticity is key when crafting reflective narratives. Don’t shy away from sharing your true emotions and vulnerabilities. Being open and honest will create a genuine connection with your readers, making your narrative more relatable and impactful.

5. Structure your narrative: Organize your narrative in a logical and coherent manner. Consider using an introduction to set the stage and to capture your readers’ attention. Use paragraphs to separate different aspects of your memory, and utilize transitions to guide your readers smoothly from one idea to the next. Finally, wrap up your narrative with a meaningful conclusion that leaves a lasting impression on your audience.

By following these tips and infusing your reflective narrative with your unique voice, you can create a compelling piece that not only sheds light on your past but also resonates with others, sparking their own introspection and personal growth. Embrace the power of memory writing prompts and let your narratives take your readers on a transformative journey.

Self-reflection is a powerful practice that allows us to understand ourselves better, learn from past experiences, and make positive changes in our lives. One effective way to enhance self-reflection is through regular memory writing practice. By engaging in this simple yet profound exercise, we can delve deeper into our thoughts, emotions, and memories, gaining valuable insights along the way.

A regular memory writing practice involves setting aside dedicated time each day or week to write about significant events, experiences, or moments that have impacted us. This could range from personal milestones and achievements to challenging situations and lessons learned. The act of writing not only serves as an outlet for self-expression, but it also helps us organize our thoughts and reflect on our past with clarity.

So how can regular memory writing practice enhance self-reflection? Here are a few key ways:

- Increased self-awareness: Through the process of writing about our memories, we become more aware of our emotions, reactions, and thought patterns. This heightened self-awareness allows us to identify behavioral patterns, triggers, and areas where personal growth is needed.

- Deepened understanding: By revisiting past experiences and examining them from various angles, we gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and the events that have shaped us. Writing helps us process complex emotions, analyze our actions, and discover underlying motivations, enabling personal development and growth.

- Enhanced problem-solving: Memory writing practice enables us to evaluate past challenges and the strategies used to overcome them. By reflecting on our decision-making and problem-solving processes, we can identify effective approaches and avoid repeating mistakes in the future.

Q: What are memory writing prompts? A: Memory writing prompts are thought-provoking questions or prompts that encourage you to reflect on past experiences and memories. They serve as inspiration for writing reflective narratives that allow you to explore and capture the depth of your memories.

Q: How do memory writing prompts work? A: Memory writing prompts work by triggering memories and emotions related to a specific moment or event. By asking questions that recall details or evoke certain feelings, these prompts help you tap into your memory bank and produce more honest and vivid narratives.

Q: Why should I use memory writing prompts? A: Memory writing prompts can be highly beneficial for numerous reasons. Firstly, they provide an opportunity for self-reflection and personal growth. Engaging with memories in writing allows you to better understand your experiences, learn from them, and gain new insights. Additionally, memory writing prompts can inspire creativity, improve writing skills , and serve as a therapeutic practice for your mental well-being.

Q: Who can benefit from using memory writing prompts? A: Anyone can benefit from using memory writing prompts. Whether you’re an aspiring writer looking to enhance your storytelling abilities, an individual seeking self-reflection and personal growth, or simply someone wanting to explore your memories in a meaningful way, memory writing prompts offer an accessible and effective tool.

Q: How can I use memory writing prompts effectively? A: To use memory writing prompts effectively, find a quiet and comfortable space where you feel inspired. Select a prompt that resonates with you or choose one randomly. Allow yourself to dive into your memories, recalling specific details and sensations associated with the prompt. Write freely and without judgment, letting the words flow as you explore the depth of your memory. Finally, read and reflect on what you’ve written, capturing any new insights or emotions that arise.

Q: Are there any tips for finding the right memory writing prompts? A: Absolutely! When looking for memory writing prompts, consider choosing prompts that are personal to you. Prompts related to significant life events, transformative moments, or emotionally charged experiences tend to evoke deeper reflections. Additionally, you can find memory writing prompts in books, online resources, or even create your own based on specific themes or time periods in your life.

Q: Can memory writing prompts be used for therapeutic purposes? A: Yes, memory writing prompts can indeed be used as a therapeutic practice. Engaging with memories and writing about them can help process emotions, heal past wounds , and reduce stress or anxiety. The act of reflection and storytelling can provide a sense of relief and offer an avenue for personal growth and self-discovery.

Q: Are memory writing prompts only for professional writers? A: Not at all! Memory writing prompts are not limited to professional writers. These prompts are for anyone looking to explore their memories, express themselves through writing, or engage in self-reflection. In fact, memory writing prompts can be particularly helpful for novice writers as they offer a structured starting point and guidance for crafting a compelling narrative.

Q: Can memory writing prompts be beneficial for preserving family histories? A: Definitely! Memory writing prompts serve as excellent tools for preserving family histories. By encouraging individuals to recall and document their past experiences, these prompts can help capture important family stories, traditions, and memories that might otherwise be lost over time. They enable future generations to connect with their roots and understand their family’s history on a deeper level.

Q: Where can I find memory writing prompts? A: You can find memory writing prompts in various places. Many books, both fiction and nonfiction, include prompts for self-reflection. Numerous websites and blogs also provide an array of memory writing prompts suited to different topics and styles. You can even create your own prompts inspired by specific memories or experiences, making the process more personalized and meaningful to you.

In conclusion, memory writing prompts offer a powerful tool for exploring our past and sharing our experiences through reflective narratives.

If I Had a Pot of Gold Writing Prompt: Imagine Riches and Adventures

Academic Insights: Revisiting Creative Writing in High School

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities.

Welcome to Creative Writing Prompts

At Creative Writing Prompts, we believe in the power of words to shape worlds. Our platform is a sanctuary for aspiring writers, seasoned wordsmiths, and everyone. Here, storytelling finds its home, and your creative journey begins its captivating voyage.

© 2024 Creativewriting-prompts.com

How Memory Works

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Memory is a continually unfolding process. Initial details of an experience take shape in memory; the brain’s representation of that information then changes over time. With subsequent reactivations, the memory grows stronger or fainter and takes on different characteristics. Memories reflect real-world experience, but with varying levels of fidelity to that original experience.

The degree to which the memories we form are accurate or easily recalled depends on a variety of factors, from the psychological conditions in which information is first translated into memory to the manner in which we seek—or are unwittingly prompted—to conjure details from the past.

On This Page

- How Memories Are Made

- How Memories Are Stored in the Brain

- How We Recall Memories

- False and Distorted Memories

The creation of a memory requires a conversion of a select amount of the information one perceives into more permanent form. A subset of that memory will be secured in long-term storage, accessible for future use. Many factors during and after the creation of a memory influence what (and how much) gets preserved.

Memory serves many purposes, from allowing us to revisit and learn from past experiences to storing knowledge about the world and how things work. More broadly, a major function of memory in humans and other animals is to help ensure that our behavior fits the present situation and that we can adjust it based on experience.

Encoding is the first stage of memory. It is the process by which the details of a person’s experience are converted into a form that can be stored in the brain. People are more likely to encode details of what they are paying attention to and details that are personally significant.

Retention, or storage, is the stage in which information is preserved in memory following its initial encoding. These stored memories are incomplete : Some of the information that is encoded during an experience fades during retention, sometimes quickly, while other details remain. A related term, memory consolidation , refers to the neurobiological process of long-term memory formation.

Sleep facilitates the retention of memories, though why exactly this is the case is not fully understood. Research has found that people tend to show better memory performance if they sleep after a phase of studying rather than staying awake. Researchers have proposed that sleep supports memory consolidation in the brain, though other explanations include tha t sleep aids retention by eliminating interference from memories that would be formed while awake.

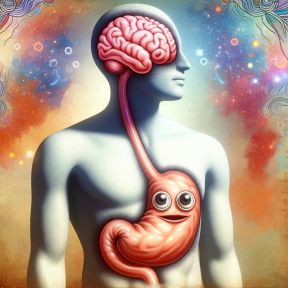

While memories are usually described in terms of mental concepts, such as single packages of personal experience or specific facts, they are ultimately reducible to the workings and characteristics of the ever-firing cells of the brain. Scientists have narrowed down regions of the brain that are key to memory and developed an increasingly detailed understanding of the material form of these mental phenomena.

The hippocampus and other parts of the medial temporal lobe are critical for many forms of memory, though various other parts of the brain play roles as well. These include areas of the more recently evolved cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the brain, as well as deep-seated structures such as the basal ganglia. The amygdala is important for memory as well, including the integration of emotional responses into memory. The extent to which different brain regions are involved in memory depends on the type of memory.

Memory involves changes to the brain’s neural networks. Neurons in the brain are connected by synapses, which are bound together by chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) to form larger networks. Memory storage is thought to involve changes in the strength of these connections in the areas of the brain that have been linked to memory.

A memory engram , or memory trace, is a term for the set of changes in the brain on which a memory is based. These are thought to include changes at the level of the synapses that connect brain cells. Research suggests an engram is not located in one specific location in the brain, but in multiple, interconnected locations. Engram cells are groups of cells that support a memory: They are activated and altered during learning and reactivated during remembering.

After memories are stored in the brain, they must be retrieved in order to be useful. While we may or may not be consciously aware that information is being summoned from storage at any given moment, this stage of memory is constantly unfolding—and the very act of remembering changes how memories are subsequently filed away.

Retrieval is the stage of memory in which the information saved in memory is recalled, whether consciously or unconsciously. It follows the stages of encoding and storage. Retrieval includes both intentional remembering, as when one thinks back to a previous experience or tries to put a name to a face, and more passive recall, as when the meanings of well-known words or the notes of a song come effortlessly to mind.

A retrieval cue is a stimulus that initiates remembering. Retrieval cues can be external, such as an image, text, a scent, or some other stimulus that relates to the memory. They can also be internal, such as a thought or sensation that is relevant to the memory. Cues can be encountered inadvertently or deliberately sought in the process of deliberately trying to remember something.

Multiple factors influence why we remember what we do. Emotionally charged memories tend to be relatively easy to recall. So is information that has been retrieved from memory many times, through studying, carrying out a routine, or some other form of repetition. And the “encoding specificity principle” holds that one is more likely to recall a memory when there is greater similarity between a retrieval cue (such as an image or sound in the present) and the conditions in which the memory was initially formed.

After a memory is retrieved, it is thought to undergo a process called reconsolidation , during which its representation in the brain can change based on input at the time of remembering. This capacity for memories to be reformed after retrieval has been explored as a potential element of psychotherapeutic interventions (for dampening the intensity of threatening memories, for example).

“Flashbulb memories” are what psychologists have called memories of one’s personal experience of significant and emotionally intense events, such as the 9/11 attacks and other highly distinctive occurrences. These memories may seem especially vivid and reliable even if the accuracy of the remembered details diminishes over time.

Priming is what happens when being exposed to one stimulus (such as a word) affects how a person responds to another, related one. For example, if someone is shown a list of words that includes nurse , he may be more likely to subsequently fill out the word stem nu____ with that word. Measures of priming can be used to demonstrate implicit memory, or memory that does not involve conscious recollection.

Memories have to be reconstructed in order to be used, and the piecing-together of details leaves plenty of room for inaccuracies—and even outright falsehoods—to contaminate the record. These errors reflect a memory system that is built to craft a useful account of past experience, not a perfect one. (For more, see False Memories .)

Memories may be rendered less accurate based on conditions when they are first formed, such as how much attention is paid during the experience. And the malleability of memories over time means internal and external factors can introduce errors. These may include a person’s knowledge and expectations about the world (used to fill in the blanks of a memory) and misleading suggestions by other people about what occurred.

False memories can be as simple as concluding that you were shown a word that you actually weren’t , but it may also include believing you experienced a dramatic event that you didn’t. People may produce such false recollections by unwittingly drawing on the details of actual, related experiences, or in some cases, as a response to another person’s detailed suggestions (perhaps involving some true details) about an imaginary event that is purported to be real.

It probably depends on the kind of memory. Minor manipulations like convincing people they saw a word that they did not see seem to be fairly easy to do. Getting people to conclude they had an experience (like spilling punch at a wedding) that was in fact made up seems to require more work—including, in one study, a couple of conversations and encouragement to think more about the “memory”—and may fully succeed only for a minority of people. Still, researchers who have investigated the implanting of false memories argue that in some cases, enough outside suggestion could result in the creation of false or distorted memories that have serious legal consequences.

Déjà vu, a French phrase that translates to “already seen,” is the sense of having seen or experienced something before, even though one is in fact encountering it for the first time. While the cause is not fully understood, one explanation for why déjà vu happens is that there is some resemblance between a current experience and a previous one, but the previous experience is not readily identified in the moment. Others have suggested that déjà vu may result from new information somehow being passed straight to long-term memory, or from the spontaneous activation of a part of the brain called the rhinal cortex, involved in the sense of familiarity.

A woman at my gym walks on the treadmill backwards; sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. After months of watching her and wondering when she might fall, I asked her about it.

Personal Perspective: We are thrilled by even the least coincidental of stories, but do they shape our lives with meaning? Or are they meaningless, random connections?

Without thinking, we often punish fear in small ways—by scolding, humiliating, or trivializing. Instead, teach fear management gradually and methodically in people and animals.

Convincing evidence from plants, flatworms, slime molds, and our own bodies suggests that neurons may not be the only cells that "think."

A new study reveals the importance of idle periods for long-term memory formation.

Research shows that even our closest primate relatives struggle to learn sequences. Could sequential memory differentiate us from the rest of the animal world?

Having a good memory is definitely an asset in life, particularly as people get older. New research on emotions and forgetting shows how a good mood can build that asset.

Would you like to improve recall, emotional control, and productivity? Learn how to think about working memory differently and apply four key strategies for improving it.

Eyewitness testimony is known to be unreliable. New research suggests that it's even worse when a witness is also the victim.

For those burdened by their past, relief can be found not in the science of memory but in the recognition of our ability to shape the very nature of our personal histories.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Cognitive Philosophy of Reflection

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 12 September 2020

- Volume 87 , pages 2219–2242, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Andreas Stephens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5684-3355 1 &

- Trond A. Tjøstheim 1

8901 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

Hilary Kornblith argues that many traditional philosophical accounts involve problematic views of reflection (understood as second-order mental states). According to Kornblith, reflection does not add reliability, which makes it unfit to underlie a separate form of knowledge. We show that a broader understanding of reflection, encompassing Type 2 processes, working memory, and episodic long-term memory, can provide philosophy with elucidating input that a restricted view misses. We further argue that reflection in fact often does add reliability, through generalizability, flexibility, and creativity that is helpful in newly encountered situations, even if the restricted sense of both reflection and knowledge is accepted. And so, a division of knowledge into one reflexive (animal) form and one reflective form remains a plausible, and possibly fruitful, option.

Similar content being viewed by others

What Is the Function of Confirmation Bias?

From short-term store to multicomponent working memory: the role of the modal model.

Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Throughout the history of Western philosophy, reflection has been considered an especially important human ability. Its role has long been prominent and can still be found at the center of theories by contemporary scholars such as, for example, BonJour ( 1985 , 1998 ), Chisholm ( 1989 ), and Sosa ( 2007 , 2009 ). Accordingly, a lot of effort has been invested in the inquiry of its role for thinking, knowledge, and justification. Common traditional positions have included that reflection is necessary in order to guarantee that an agent’s knowledge is acceptable and certain, that her epistemic duty is fulfilled, that her knowledge is accessible, and that faulty beliefs due to inferential errors are avoided (see, e.g., Pappas 2017 ; see also Bortolotti 2011 ).

But in contrast to the above-described positions, Hilary Kornblith in his book On reflection ( 2012 ) points out that the common interpretation of reflection is problematic since reflection actually cannot provide that which many believe it can. Indeed much relevant research seems to indicate that rather than providing trustworthy knowledge, reflection can be quite unreliable. Numerous psychological studies, seemingly, show how human reflection often fails due to, for example, various biases (see, e.g., Stanovich and West 2000 ; Kahneman 2011 ). With this in mind, the importance of reflection, and its role for human thinking, knowledge, and justification, should arguably be deemphasized.

This leaves us at an interesting junction. On the one hand, reflection seems to underlie the very essence of human greatness and is commonly seen as a particularly important phenomenon. On the other hand, empirical evidence seems to support Kornblith’s view and suggest that reflection only brings a false sense of certainty.

We recognize that inquiries are affected by the inquirer’s stance (approach, commitments), which makes it important to briefly clarify our own. In line with Kornblith (see, e.g., 1993 , 2002 , 2012 ), we heed a naturalistic stance where philosophy needs to take relevant scientific results into account whenever such results are available. Accordingly, we accept both ontological and (cooperative) methodological naturalism, where natural phenomena and relevant scientific results are seen as more important than language or intuitions (see, e.g., Papineau 2016 ; Rysiew 2017 ; Cellucci 2017 ). We claim, as does Kornblith, that such a stance can offer philosophy new insights that are crucial for keeping the field relevant as well as for dissolving old problems.

In short, we believe that Kornblith’s discussion of reflection is problematic due to its too-narrow understanding of what reflection brings to the table. Given this position, our aim in this article is to investigate reflection more broadly by examining relevant psychological constructs and their neural underpinnings. By stepwise investigating reflection on multiple levels of analysis, a synthesizing understanding of reflection that is biologically plausible can arguably be reached (see, e.g., Hassabis et al. 2017 ). This allows us to triangulate essential features of the natural phenomenon that Kornblith downplays or ignores (Horst 2016 ). We will, however, also argue that even if we accept a restricted view of reflection as ‘second-order mental states,’ as well as Kornblith’s insistence on that reliability is the only epistemic value to consider, reflection, in fact, often does offer the subject added reliability. Importantly, this would leave the division of knowledge into a reflexive (animal) form and a reflective form a plausible option.

This article comprises five sections. In Sect. 2 , we outline and discuss Kornblith’s account of reflection. In Sect. 3 , we investigate how reflection can be further elucidated by cognitive psychology, also outlining the neural correlates of reflection. In Sect. 4 , we then explore philosophical consequences of the reached position pertaining to reliability and knowledge. Finally, in Sect. 5 , we offer some concluding remarks.

2 Kornblith on Reflection

Kornblith ( 2012 ) argues that most traditional philosophers have valued reflection too highly due to faulty understandings of what it involves. And this overestimation has, in his view, led them to suggest, or even demand, that reflection is necessary when, in fact, such a view is wrong. Traditional philosophers, on Kornblith’s view, tend to call on reflection when problems are recognized at a first-order level. Second-order reflection is then supposed to provide a solution by removing unreliability. This, however, according to Kornblith, is problematic since neither first-order processes nor second-order reflective scrutiny are entirely reliable. Kornblith argues that his points concerning reflection are generalizable and relevant for discussions of knowledge, reasoning, freedom of the will, and normativity. In this article we will focus on his discussion of knowledge.

Importantly, Kornblith addresses reflection specifically seen as consisting in ‘second-order mental states.’ He further considers reliability as being the only important criteria for belief acquisition processes (Kornblith 2012 , p. 34). Kornblith then attacks the traditional view from two angles. Firstly, he argues that a reliance on reflection leads to an infinite regress and that reflection thus cannot provide the sought after reliability for first-order problems. Secondly, he argues that empirical evidence indeed indicates that the processes involved in reflection often are unreliable. Both these arguments, which will be presented more fully in the following subsections, according to Kornblith shows that reflection fails to be relevant for knowledge.

2.1 Infinite Regress

As a first argument against the traditional view, Kornblith claims that demands for reflection lead to an infinite regress since it continuously would require demands of ever higher-level reflections. Footnote 1

According to Kornblith, knowledge, in its paradigmatic formulation, is commonly held to require justified true belief. And, as pointed out by Kornblith, according to many theoreticians, justification involves reflection on the epistemic status of one’s beliefs. It is then only reflection that can guarantee the right epistemic status to one’s beliefs. An omission to reflect would result in beliefs that cannot be considered knowledge.

We regard this a reasonable estimate of the common-sense view, although it arguably involves an implicit internalist view of knowledge. Indeed, Kornblith starts his discussion by presenting the famous ‘Norman the clairvoyant’ case by BonJour ( 1985 ). In short, BonJour (an internalist) argues that an agent needs active reflection, that makes her epistemically responsible, for knowledge. This is presented, by BonJour, as an argument against reliabilism (a form of externalism) that views knowledge as involving reliably produced true beliefs, hinging on the external connection between the agent and the world.

Now, Kornblith, who is an outspoken reliabilist (see, e.g., Kornblith 2002 ) argues that if an agent is to meet BonJour’s requirements and reflect on her beliefs, the reached beliefs would themselves, in turn, need to be justified by higher-order reflection, leading to an infinite regress (Kornblith 2012 , pp. 12–13).

If one accepts Kornblith’s strict understanding of reflection as second-order mental states and knowledge as being dependent on reliability, this indeed seems to be the forced conclusion.

2.2 Empirical Evidence Against the Reliability of Reflection

As a second argument against the traditional view, Kornblith claims that a wide range of empirical evidence shows that reflection often is unreliable. Reflective scrutiny does then most often not succeed in making us able to more reliably judge our first-order beliefs, but seems to make subjects more confident when in fact this is not motivated (Kornblith 2012 , pp. 3, 25). This would indicate that it is not a tenable option to accept the aforementioned infinite regress as an inevitability and claim that having some reflective scrutiny at least is better than having none.

Sidestepping the merely logical matter of things, a large amount of empirical evidence seemingly does support Kornblith’s interpretation where reflection is best seen as only bringing a false sense of certainty to the table. In defense of his position Kornblith presents, and interprets, several empirical findings that cohere with his account. Notably, he acknowledges the tentative nature of such findings and theorizing (Kornblith 2012 , p. 136). It is also important to point out that Kornblith does not claim that reflection is useless, rather he argues that reflection might be useful if a more realistic account of it is accepted.

Kornblith focuses on cognitive psychology and the influential dual process theory. Briefly put, reflection figures distinctly in this framework, which partitions the mental into two forms. The first form (the old mind, System 1, or Type 1) is considered to be intuitive, automatic, non-conscious, and implicit, whereas the second form (the new mind, System 2, or Type 2) is reflective, controlled, conscious, and explicit. Footnote 2 On this account, the first form generate fast reflexive responses, which the second form sometimes reflectively inhibits (Tversky and Kahneman 1974 , 1983 ; Sloman 1996 ; Barrett et al. 2004 ; Kahneman 2011 ; Evans 2007 , 2008 ; Samuels 2009 ; Lizardo et al. 2016 ; Bago and De Neys 2017 ).

We consider Kornblith’s choice to focus on dual process theory reasonable since that framework is canonical and directly addresses aspects of cognition that are highly relevant for understanding reflection and knowledge, being supported ‘… by a wide range of converging experimental, psychometric, and neuroscientific methods’ (Evans and Stanovich 2013 , p. 224). But, we want to point out that many interpretations of dual process theory exist, addressing, for example, types, systems or modes. This said, most interpretations of dual process theory can, arguably, be integrated into a common format which makes it fruitful to explore dual process theory as a, more or less, unified field although this should be done with care (Smith and DeCoster 2000 , p. 110; Evans 2003 , p. 458). Moreover, it should be mentioned that there are researchers critical of dual process theory, where critics have pointed out both faults and alternative interpretations (see, e.g., Gigerenzer and Regier 1996 ; Keren and Schul 2009 ; Kruglanski et al. 2003 ; Osman 2004 ; Kruglanski and Gigerenzer 2011 ). The force of these lines of critique, though, hinge on which specific form of dual process theory they attack, and, for example, Evans and Stanovich ( 2013 ) in our view convincingly counters a number of the more common ones.

Importantly, if dual process theory, more generally, is not accepted as a provider of valid empirical input, Kornblith’s argument would indeed be severely stifled. However, our main point here does not involve questioning dual process theory per se. Rather we claim that Kornblith’s interpretation of cognitive psychological theorizing and evidence is problematic since it too narrowly only focuses on dual process theory. To remain a plausible option, Kornblith’s restricted position needs to be developed in a pluralist direction that investigates the many important roles reflection fills for how a subject (organism) acts in her (its) environment (see, e.g., Shah and Vavova 2014 ). We will in the following Sect. 3 explore what such an account of reflection involves and how it can offer philosophy elucidating input.

2.3 Reflection as Decoupled from Knowledge

Taken together, Kornblith’s arguments, indeed, seem to capture essential problems with the traditional positions that he criticises; it is, it seems, deeply questionable whether reflection can solve the problems often assumed that it can. And since reflection, indeed, does take such a center stage in much philosophical discussion, Kornblith’s focus is highly relevant. Kornblith interprets the reached position as indicating that theoreticians ought to abandon any false hopes regarding what reflection can provide (Kornblith 2012 , p. 7).

Kornblith discusses how Sosa’s ( 1991 ; see also 2007 ; 2009 ) distinction between ‘animal knowledge’ and ‘reflective knowledge’ can offer a way out of the infinite regress. On this account, animal knowledge governs direct responses to one’s sensory impacts, whereas reflective knowledge governs a wider understanding of one’s responses and how they came about (Sosa 1991 , p. 240). Animal knowledge is then more or less what externalist theories focus on, and reflective knowledge is what internalist theories focus on. Kornblith claims that this distinction, indeed, would resolve the issue of an infinite regress. Nonetheless he continues to argue that the reflective knowledge of the bisection does not add anything extra that is superior to ‘mere’ animal knowledge. Kornblith discusses, and rejects, the possibility that what reflective knowledge adds is increased reliability, which is also what Sosa argues (Kornblith 2012 , pp. 16–17; Sosa 1991 , p. 240). Since Kornblith considers reliability crucial for knowledge he then rejects a division of knowledge, even though he acknowledges that reflection might fill some other important role(s) (Kornblith 2012 , pp. 19–20).

Yet, even if we accept the restricted view of reflection as second-order mental states, and accept that reliability is of sole importance (something we believe indicates a rather strong externalist position), then if it turned out that reflective processes do add to a subject’s reliability, this would, on Kornblith’s own account, rebut the infinite regress and make reflection eligible as underlying a distinct form of knowledge.

Kornblith accepts this possibility but emphatically denies that this is the case:

We have examined a number of alternative motivations, and found that these motivations as well cannot bear the weight of the tempting distinction. It seems that there really is no ground at all for drawing a distinction between unreflective knowledge and something better, knowledge which involves reflection. (Kornblith 2012 , p. 40)

We will in Sect. 4 specifically address how reflection can add reliability, even if the narrow account of it as only involving second-order mental states is accepted. This can be done by providing the subject with an opportunity to remember previous experiences and internally reflect on them in order to find patterns in them and then adjusting ensuing behaviors in accordance with the found patterns. In doing so the subject gains generalizability, flexibility, and creativity that is helpful in newly encountered situations. Therefore, a division of knowledge into one reflexive (animal) form and one reflective form remains a plausible, and possibly fruitful, option (see, e.g., Perrine 2014 ; Shah and Vavova 2014 ; Smithies 2016 ). So, although Kornblith ( 2012 , pp. 16, 19) discusses how an allowance of two forms of knowledge could be seen as arbitrary and might risk leading to that infinitely many multiple forms must be allowed, we will below present a discussion that instead argues that two forms are biologically plausible.

But before we do this, we will next explore what a biologically plausible broader account of reflection involves and how it can offer philosophy elucidating input.

3 A Broader Understanding of Reflection

In this section, we follow Kornblith in focusing on cognitive psychology but, importantly, strive to stepwise develop a deeper multi-level investigation into reflection and its underlying processes that go beyond Kornblith’s sole focus on dual process theory. This account, which also encompasses memory systems and neural correlates, offers a broader understanding of reflection that is not restricted to only involve second-order mental states. It is our belief that this account can provide philosophy with elucidating input that Kornblith’s restricted focus misses.

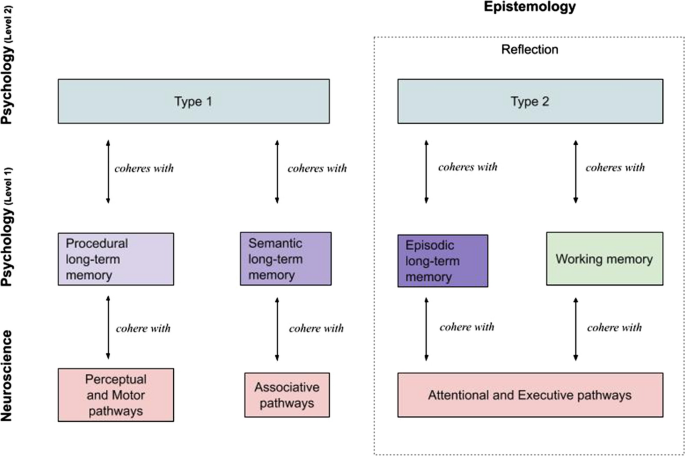

In Fig. 1 we present a schematic illustration of how influential models from three levels of analysis cohere with each other, and how they relate to reflection. Although this is not an exhaustive account, we aim to substantiate this interdisciplinary approximation in the following discussion:

Schematic illustration of relations between cognitive models, on different levels of analysis, and their relation to reflection. Four perspectives are represented: epistemology (dotted square); psychology level 2 (top row); psychology level 1 (middle row); neuroscience (bottom row). Boxes indicate model categories. Arrows indicate functional relationships

We now move to a description of how reflection is understood in cognitive psychology and find that a broader interpretation than the one Kornblith presents is motivated.

3.1 Reflection in Cognitive Psychology

In the dual process theory-literature, which is Kornblith’s specific focus, reflection tends to be explicitly highlighted as an important phenomenon (see, e.g., Carruthers 2009 ; Mercier and Sperber 2009 ; Stanovich 2009 ; Evans and Stanovich 2013 ). According to dual process theory, reflection is considered to involve many specific functions linked to Type 2 processes (Evans 2008 , p. 257). These complex functions encompass, for example, internal linguistics sequences or ‘sentences of inner speech’ (Frankish 2009 , pp. 11–12; see also Carruthers 2009 , p. 118), the ability to connect mental images to language, comprehend visual semantics, as well as visual manipulation (visual management) (Frankish 2010 , p. 921; Carruthers 2009 , p. 112). Moreover, from the perspective of dual process theory, the reflective mind is considered to include decision making, mental simulation, goal-adoption, belief-fixation, the ability for making comparisons, reasoning, metacognition in the form of second-order mental states, as well as hypothetical thinking (Evans and Stanovich 2013 ). Furthermore, recollection and the binding of information are dependent on reflection. It is crucial for a sense of time and to make out specific events (Yonelinas 2013 , p. 2). In addition, Type 2 processes are linked to explicit rule learning (Evans 2008 , pp. 257, 261, 267).

Even though human agents might not always be as in control as they believe themselves to be, these functions of reflection are important for their self-awareness and sense of agency. All these abilities are thus plausible to see as comprising a first outline.

There is a line of critique arguing that cognition is better seen as a continuum of processes than as two distinct ones (see, e.g., Osman 2004 ). This has some intuitive plausibility, however, by highlighting the difference of various forms of dual process theories this issue can, arguably, be circumvented. As Evans and Stanovich ( 2013 , p. 229) point out, there are indeed modes of processing (‘cognitive styles applied in Type 2 processing’) that can vary on a continuum. Specific Type 2 reflections can thus be performed in a variety of different manners. But, what most dual process theories try to point out is that there are two distinct types of cognitive processes, where Type 2 processes stand out as being flexible and linked to reflection. And so, ‘[c]ontinuous variation in both cognitive ability and thinking dispositions can determine the probability that a response primed by Type 1 processing will be expressed—but the continuous variation in this probability in no way invalidates the discrete distinction between Type 1 and Type 2 processing’ (Evans and Stanovich 2013 , pp. 229–230).

So, even though there are pending issues concerning how we should view reflection from the perspective of cognitive psychology, we consider it initially plausible to link reflection to Type 2 processes. To reiterate, rather than viewing reflection as problematic, dual process theory indicates that it underlies several important cognitive functions such as internal linguistics sequences or ‘inner speech,’ visual semantic comprehension, visual manipulation, and mental simulation (visual management for short), decision making, goal-adoption, belief-fixation, reasoning, metacognition in the form of second-order mental states, hypothetical thinking, self-awareness, and our sense of agency.

To broaden our understanding of reflection and Type 2 processes we continue by focusing on a second, ‘lower,’ cognitive psychological level of analysis where the human memory systems are seen as consisting of many interconnected functional processes that encode, store, retrieve, and manage information. On this level, an influential division is made between long-term memory (LTM) and working memory (WM), where LTM can store information over a lifetime whereas WM governs active information handling (see, e.g., Repovš and Baddeley 2006 ). Footnote 3

LTM is commonly partitioned into an implicit (non-declarative, non-conscious) system and an explicit (declarative, conscious) system. The non-declarative system is thought to govern automatic actions, whereas the declarative system is thought to govern abstracted knowledge about the world and autobiographical remembrance. In Tulving’s (see, e.g., 1972 , 1985 , 2002 , 2005 ) canonical and very influential three-part model of LTM, involving procedural, semantic and episodic memory, procedural memory governs perceptual and motor skills, semantic memory governs conceptual and categorical knowledge, whereas episodic memory governs remembrance of events (Tulving 1985 , p. 2). According to Tulving ‘… procedural memory entails semantic memory as a specialized subcategory, and… semantic memory, in turn, entails episodic memory as a specialized subcategory.’ (Tulving 1985 , pp. 2–3, italics in original).

Regarding WM, various models have been proposed although a very influential multi-component ‘standard model’ presents it as consisting of four parts: the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad, the central executive, and the episodic buffer (Baddeley and Hitch 1974 ; Baddeley 2000 , 2007 ; Repovš and Baddeley 2006 ; D’Esposito and Postle 2015 ; Chai et al. 2018 ). In short, the phonological loop controls auditory information, the visuospatial sketchpad controls visual and spatial information, the central executive controls attention and decisions, whereas the episodic buffer binds together information from different domains, working as a link to (episodic) LTM. Footnote 4

Since it is through WM we actively handle information (see, e.g., Miller 1956 ; Cowan 2001 ) we argue that it is this system—on this level of analysis—which is primarily involved in Type 2 processes and reflection (Evans 2008 ). To substantiate this claim we show below how WM coheres with reflection as well as to the various previously mentioned features of Type 2 processes.

The phonological loop includes the articulatory network and the sensorimotor interface (Hickok and Poeppel 2007 ). It is thought to consist of a phonological store that can hold acoustic information for a couple of seconds, and an articulatory rehearsal process governing subvocalization by which verbal information is kept in memory. Apart from auditory information and speech, information needs to be re-coded through articulatory rehearsal before it can enter the phonological store. Accordingly, the phonological loop connects WM to language, and thus coheres with internal linguistics sequences and inner speech (Repovš and Baddeley 2006 , p. 7).

The visuospatial sketchpad consists of two separate subsystems governing visual and spatial information respectively. It is crucially connected to how we perceive the world. Interestingly, we rely on a quite small amount of information from the surrounding world—since it tends to be stable, offering us a continuing ‘external memory.’ However, this bottom-up information also relies on top-down predictions when being interpreted into meaningful percepts (see, e.g., Friston 2010 ; Hohwy 2013 ; but see Firestone and Scholl 2016 for a recent challenge). The visuospatial sketchpad thus coheres with previously mentioned visual management abilities (Repovš and Baddeley 2006 , pp. 8, 12).