- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

10 Conducting Mixed Methods Literature Reviews: Synthesizing the Evidence Needed to Develop and Implement Complex Social and Health Interventions

Jennifer Leeman, DrPH, MDiv, is an Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing. Her research focuses on identifying, translating, and disseminating the evidence base for prevention interventions that target change at the levels of behavior, environments, and policy. Dr. Leeman is Co-Principal Investigator of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded Center for Training and Research Translation in Obesity Prevention (2004-2014) and Principal Investigator of the Comprehensive Cancer Control Collaborative, NC (2009-2014), a National Cancer Institute/CDC-funded center that works with nine other centers nationwide to advance dissemination and implementation science in the area of cancer prevention and control. She has published numerous mixed-methods literature reviews and served as a co-investigator on two National Institutes of Health-funded mixed-methods literature synthesis studies.

Corrine I. Voils is Associate Professor, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Duke University Medical Center. Dr. Voils’ primary research interest is in developing and testing behavioral interventions to improve dietary intake, physical activity levels, and medication adherence for chronic disease prevention and management. She uses mixed methods for intervention development and evaluation as well as survey/measure development. Previously, she co-led with Dr. Margie Sandelowski a National Institutes of Health-funded methodology project to develop and evaluate methods for synthesizing qualitative and quantitative research.

Margarete Sandelowski has published widely in nursing, interdisciplinary health, and social science anthologies and journals in the areas of technology and gender, infertility and prenatal diagnosis, and of qualitative and mixed-methods primary research and research synthesis. Among her funded studies are three National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) R01 grants for mixed-methods research projects. Most recently she completed a NIH/NINR-funded study to develop techniques to synthesize qualitative and quantitative research findings. She is currently multiple PI (with Kathleen Knafl) of the NIH/NINR-funded “Mixed-methods synthesis of research on childhood chronic conditions and family,” which is directed toward integrating the findings of empirical research addressing the intersection between family life and childhood chronic physical conditions. Her many publications in the mixed-methods research domain include Sandelowski, M. (2014). Unmixing mixed-methods research. Research in Nursing & Health, 37, 3-8; Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., & Knafl, G. (2009). On quantitizing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3, 208-222; Song, M., Sandelowski, M., & Happ, M. B. (2010). Current practices and emerging trends in conducting mixed-methods intervention studies in the health sciences. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed., pp. 725-747). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; and Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., Leeman, J., & Crandell, J. L. (2012). Mapping the mixed research synthesis terrain. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6, 317-331.

- Published: 19 January 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Systematic literature reviews serve the purpose of integrating findings from reports of multiple research studies and thereby build the evidence base for both research and practice. Mixed methods literature reviews (MMLRs) are distinct in that they summarize and integrate findings from qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies via qualitative and/or quantitative methods. Although MMLRs encompass a range of approaches, the focus of this chapter is on their potential to contribute to the evidence base for complex social and health interventions. The chapter includes examples illustrating how MMLRs have been applied to synthesize evidence for complex interventions and concludes with a discussion of the challenges involved and suggestions for surmounting them.

Introduction

Systematic literature reviews serve the purpose of integrating findings from reports of multiple research studies and, thereby, build the evidence base for both research and practice. Like mono-method research reviews, mixed methods literature reviews (MMLRs) are systematic in that they follow specified research protocols for retrieving literature and extracting and synthesizing data from that literature. MMLRs are distinct in that they summarize and integrate findings from qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies via qualitative and/or quantitative methods. In MMLRs “what is ‘mixed’ are both the object of synthesis (i.e., the findings appearing in written reports of primary qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies) and the mode of synthesis (i.e., the qualitative and quantitative approaches to the integration of those findings)” ( Sandelowski, Voils, Leeman, & Crandell, 2012 , p. 317). Although MMLRs encompass a range of approaches (e.g., Harden & Thomas, 2010 ; Pope, Mays, & Popay, 2007 ), in this chapter, we focus on MMLRs used for the purpose of building the evidence base for practice. We focus, in particular, on the use of MMLR as an approach to developing and implementing complex social and health interventions, in other words, interventions that aim to improve the well-being of individuals and populations either directly (e.g., behavioral and education interventions) or indirectly via changes to policies, systems, and environments.

Although MMLRs constitute a relatively small percentage of published reviews of the literature, their numbers are increasing rapidly. Much of this growth is being driven by calls for greater use of research findings in practice coupled with the recognition that this will require greater understanding of the contexts and perspectives of the potential users of those findings ( Chalmers & Glasziou, 2009 ; Glasgow et al., 2012 ; Tunis, Stryer, & Clancy, 2003 ). Because MMLRs include methodologically diverse findings and multiple methods, they are well suited to the goal of capturing and analyzing the breadth of evidence needed to incorporate users’ contexts and perspectives into the understanding and use of interventions. The inclusion of diverse findings and use of multiple methods also present distinct challenges to those conducting MMLRs. Accordingly, in this chapter, we present an overview of MMLRs’ potential to contribute to the science and practice of complex interventions followed by illustrations of how MMLRs may be applied to build the evidence base. The chapter concludes with a summary of challenges involved in conducting MMLRs of complex interventions and suggestions for surmounting them.

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews’ Potential to Contribute to the Science and Practice of Complex Interventions

Interventions include programs, processes, policies, or guidelines that are intended to improve the well-being of individuals and populations. Historically, generating the evidence base for these interventions has been focused on assessing their effectiveness at achieving targeted outcomes via single-method “effectiveness reviews” of single-method findings. The Cochrane Collaboration, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, and Campbell Collaboration are among the major producers of effectiveness reviews.

Effectiveness reviews involve the use of quantitative methods (e.g., meta-analysis) to summarize and synthesize quantitative findings of an intervention’s effects on outcomes ( Pope et al., 2007 ). For example, Ellis et al. (2004) systematically reviewed diabetes education interventions and applied meta-analysis to synthesize findings on the 28 identified interventions’ effectiveness at improving glycemic control. They identified diabetes education interventions as effective based on the finding that glycemic levels for participants in the intervention groups were .32% lower than for those in the control groups. In many cases, the studies testing an intervention are too few or too dissimilar to synthesize via meta-analyses. In such cases, vote counting can be used to quantify the number of studies in support versus not in support of an intervention’s effectiveness, frequently with additional weight given to studies deemed to have greater methodological rigor ( Cooper, 2010 ). Vote counting is illustrated in Goode, Reeves, and Eakin’s (2012) systematic review of telephone-delivered interventions to increase physical activity and/or improve dietary behavior, in which they counted the number of cases in which the intervention groups’ outcomes were significantly better than the comparison groups’ ( n = 20) versus the number in which they were not ( n = 7).

Although effectiveness reviews have made invaluable contributions to the evidence base for intervention effectiveness, they have been criticized for failing to provide the full range of evidence necessary to generalize findings to new contexts and implement them in real-world settings. As is described in greater detail later, effectiveness reviews have been critiqued for decontextualizing findings, excluding available evidence, and taking a largely atheoretical approach to the assessment of interventions and their effects. Thus they provide information on the net effectiveness of an intervention but fail to detail contextual factors or to build theory that might explain variations in effectiveness across different settings, populations, providers, and approaches to intervening.

The limitations of effectiveness reviews are especially evident for complex social and health interventions. Interventions are complex to the extent that they include multiple components, function at multiple levels, target multiple outcomes, and/or are designed to be tailored and individualized to recipients’ needs and preferences ( Craig et al., 2008 ). Complex interventions may include intervention programs, such as a multicomponent diabetes self-management intervention tailored to recipients’ self-management priorities. They may also include professional, organizational, and public policies such as a public policy requiring that elementary schools implement specific nutrition standards or guidelines specifying the optimal approach to depression screening. To further complicate the issue, complexity encompasses not only the intervention but also the systems within which interventions function ( Sterman, 2006 ). With few exceptions, social and health interventions function within complex systems comprised of numerous heterogeneous components and actors interrelating across multiple levels, such as cafeteria staff working in local schools that operate as part of school districts and food distribution systems or patient-care teams functioning within a medical center that is part of a larger healthcare system ( Hammond, 2009 ; Sterman, 2006 ).

Effectiveness reviews assess the evidence on “what works” by documenting the regularity of the relationship between an intervention and its outcomes ( Howe, 2012 ). In assessing effectiveness, reviewers apply a largely reductionist analytic approach that views interventions as something that can be extracted and understood independent from the broader contexts in which they function. This reductionist approach is consistent with the conventional approach to knowledge translation whereby interventions are viewed as something that can be identified, “commodified,” and then “rolled out across organizations” ( Greig, Entwistle, & Beech, 2012 , p. 305).

Complex interventions challenge a reductionist approach on multiple fronts. Because they involve multiple, flexible, and often interacting activities, complex interventions are difficult to standardize ( Ogilvie, Egan, Hamilton, & Petticrew, 2011 ), and reviewers are challenged to identify the configuration of activities that constituted “the intervention” and achieved the intended outcomes. Furthermore, intervention activities often affect intended outcomes through their effects on a chain of intermediate outcomes (i.e., mediators) that are essential to understanding why an intervention works ( Sidani & Braden, 1998 ).

The effects of intervention activities on intermediate and longer term outcomes are largely a function of how activities interact with contexts. The extent of this interaction is so integral to complex interventions as to trouble the legitimacy of trying to understand interventions separate from the contexts in which they occur ( Greig et al., 2012 ). Reviewers have attempted to capture the interaction between contextual factors and interventions by assessing the moderating effects of factors such as intervention setting or characteristics of inteveners or participants (e.g., race/ethnicity, literacy level). These reviewers often report that data are insufficient to assess variations in outcomes relative to different contextual factors (e.g., Rueda et al., 2006 ). Even when data are sufficient, this approach does not capture the interaction of interventions with the dynamics of complex systems ( Hawe, Shiell, & Riley, 2009 ). Therefore, the evidence base to guide interventions cannot be garnered solely, or even principally, via systematic reviews that take a reductionist approach. Developing the evidence base for intervening requires evidence on how intervention activities, contextual factors, and intermediate and longer term outcomes interact as part of complex systems. In other words, it requires evidence in the form of theories explaining “what works for whom in what circumstances and in what respects” ( Pawson, 2006 , p. 74).

Traditional effectiveness reviews offer conclusions about whether complex interventions have worked, but they do so by “establishing black box associations” between interventions and outcomes ( Howe, 2011 , p. 169). These reviews provide little guidance on how and why the interventions worked or how they functioned differently across contexts ( Pawson, 2006 ). For example, an effectiveness review may quantify the extent to which a problem-centered math intervention led to improvements in sixth graders’ ability to correctly answer word problems. The review typically does not, however, identify which intervention activities (or combination of activities) were effective (i.e., the intervention’s “active ingredients”; Miller, Druss, & Rohrbaugh, 2003 ). In other words, did students improve because the intervention included small work groups, didactic content, tailored practice problems, and/or peer coaching? The findings also will not address the mechanisms through which the intervention affected students’ performance (i.e., intermediate outcomes or mediators). Did students improve because they became more confident, developed new strategies, gained new knowledge, and/or became more motivated? The reviews also provide little evidence on how the effects of active ingredients on mediators and outcomes may have varied across differences in contextual factors (i.e., moderated mediation) such as subgroup and/or community cultures, teachers’ training and experience, students’ prior educational experiences, students’ math aptitudes, or class size. Review findings also do not provide guidance on how to navigate multiple levels and negotiate with diverse actors within the school system to promote widespread intervention adoption and implementation.

To build the evidence base for complex interventions, “the evidence for their effectiveness must be sufficiently comprehensive to encompass that complexity” ( Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe, & Shiell, 2002 , p. 119). As detailed in the following section, MMLRs are well positioned to encompass complexity (i.e., multiple components, levels, or outcomes) by virtue of the fact that they capture more of the available data, apply and often integrate both inductive and deductive approaches, and prioritize the development of theories.

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Include More of the Available Data

By design, effectiveness reviews include only a subset of the literature reporting the development and testing of an intervention, and they thereby exclude much of the available evidence. The exclusion of evidence is largely the result of the priority placed in effectiveness reviews on internal validity and resulting restrictions on the types of studies and publications included ( Glasgow et al., 2012 ). A Cochrane review, for example, “would typically seek all rigorous studies (e.g. randomized trials)” testing the effectiveness of an intervention ( Higgins & Green, 2011 , 5.1.2). Restrictive inclusion criteria may be appropriate for making claims about an intervention’s effect on outcomes, but these criteria limit the inclusion of evidence on how interventions work and how they vary across contexts ( Lewin et al., 2012 ). They may exclude data on participants’ and providers’ perceptions of the intervention or on contextual factors that impeded or facilitated intervention implementation, delivery, and receipt. MMLRs, however, have the potential to include a broader range of studies that provide additional evidence, including studies that are preliminary to controlled trials (e.g., pilot studies with quasi-experimental designs) or that, by design, prioritize a deep understanding of the interplay of contexts and effects, such as case studies or ethnographies. They also have the potential to capture more data from publications included in the review, such as data on intervention feasibility or acceptability or users’ experiences with an intervention. Broader inclusion criteria are particularly important in areas where most of the available evidence is from observational or quasi-experimental designs, such as public policy and health systems research ( Baxter, Killoran, Kelly, & Goyder, 2010 ; Kelly et al., 2010 ; Lewin et al., 2012 ; Rockers et al., 2012 ).

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Apply and Often Integrate Inductive and Deductive Approaches

When developing research questions, reviewers determine the extent to which their review will be guided by questions and constructs that emerge during the course of the literature review (inductive) as opposed to those that are predefined (deductive). Conventional effectiveness reviews take a predominantly confirmatory or deductive approach. In fact, guidelines for conducting and critiquing these reviews specify that review questions, variables, and constructs be identified a priori (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011; Shea et al., 2007 ). MMLRs, on the other hand, often apply an inductive approach, with reviewers identifying one or more broad research questions and then iteratively identifying and conceptualizing phenomena and their interrelationships as they emerge during the review ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ). The evidence base for many complex interventions is in the early stages of development, and, therefore, an inductive approach is critical to discovering unknown and therefore unanticipated phenomena and relationships. For example, Jagosh et al. (2012) conducted a MMLR of the benefits of participatory research, or research that involves an ongoing partnership between the researchers and the people affected by the problems being studied. Although previous reviewers had assessed the value of participatory research, their review methodologies “failed to embrace the complexity of programs or address mechanisms of change” (p. 313). In light of the limited knowledge of how participatory research works, Jagosh et al. took an inductive approach to their review. Rather than identifying variables and constructs a priori, they extracted data on any findings describing how any participatory research process led to an outcome, organized data into themes, and created visual maps of each partnership to depict the evolving relationships among contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes. They then sought patterns of relationships across the projects’ maps with the goal of developing theory to describe the outcomes of participatory research and explain how they occur and why they vary across projects.

Similar to primary mixed methods studies, MMLRs often incorporate inductive and deductive approaches over a series of stages by connecting the findings from an initial inductive analysis of data with findings from subsequent deductive analyses to confirm identifed relationships. Findings from one analysis can be placed beside, “sprinkled” onto, or “mixed” into the findings from a review of the other type of evidence, as when quotations are inserted into findings from a quantitative synthesis ( Bazeley & Kemp, 2012 , pp. 59–60). An analysis of one type of data (e.g., quantitative) may be used to confirm, explain, or explore findings from analysis of another type of data (e.g., qualitative; Creswell, Klassen, Plano Clark, & Clegg Smith, 2011 ). For example, Thomas et al. (2003) conducted a meta-analysis to assess the effects that healthy eating interventions had on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. They also synthesized qualitative and quantitative findings on children’s views of healthy eating and then integrated findings from both analyses to explore whether interventions were more effective when they were consistent with children’s views. The ability to transition between types of evidence and synthesis methods allows MMLRs the flexibility to draw on the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative data and both inductive and deductive approaches.

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Prioritize Theory Development

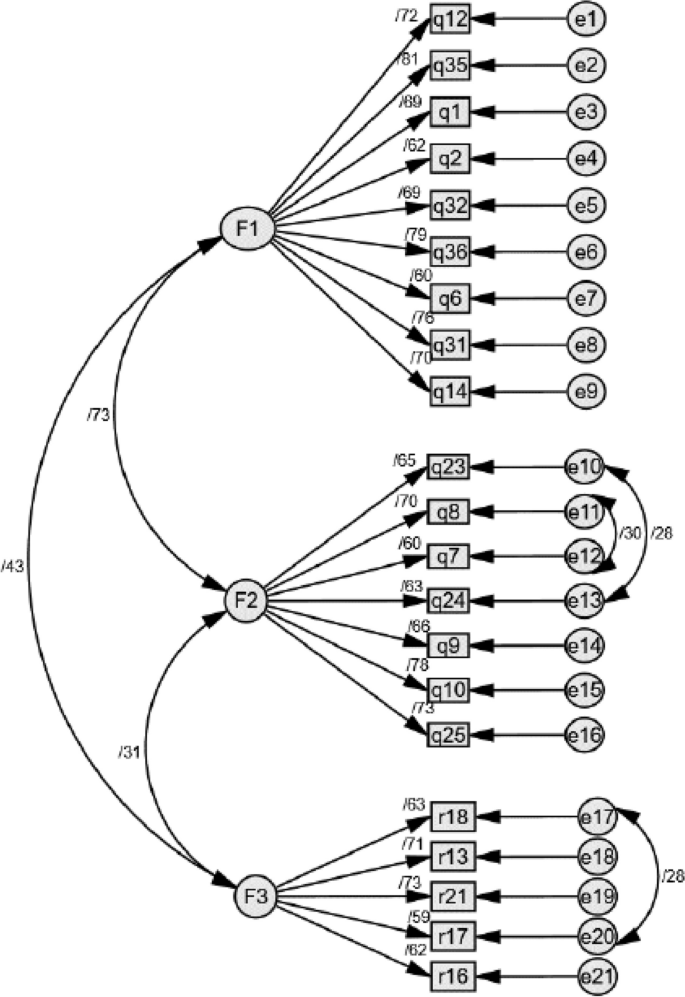

Greater use of theory has been recommended as a central approach to addressing the challenges introduced by the complexity of interventions and the systems in which they function ( Craig et al., 2008 ; Kelly et al., 2010 ; Ogilvie et al., 2011 ). MMLRs may be used to focus on refining or creating theories or conceptual frameworks. The inductive approach afforded by MMLRs offers the advantage of allowing for the discovery of new phenomena and relationships and thereby the development and refinement of theory. Reviewers contribute to theory development and testing via the configuration or aggregation of data, the two defining logics of MMLRs ( Sandelowski et al., 2012 ). Synthesis by configuration involves arranging thematically different phenomena into “a coherent theoretical rendering of them” ( Sandelowski et al., 2012 , p. 325). Reviewers applying logic of configuration explore interrelationships among phenomena with the goal of developing theory to explain why, how, and when they are related. Quantitative approaches to configuring mixed data include structural equation modeling and mediation meta-analyses. Qualitative approaches include meta-ethnography, framework-based synthesis, realist synthesis, meta-synthesis, and grounded theory ( Dixon-Woods, 2011 ; Harden & Thomas, 2010 ; Pawson, 2006 ; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007 ). The Jagosh et al. (2012) review described earlier is an example of a review that applied logic of configuration to develop beginning theory to explain how participatory-research interventions work and why they vary across contexts.

Synthesis by aggregation, on the other hand, involves pooling or merging findings considered to address similar phenomena and relationships in order to quantify the extent and nature of those relationships ( Sandelowski et al., 2012 ). Aggregation methods may be used to test and refine theory by, for example, assessing the weight of evidence in support of relationships posited by existing or reviewer-developed theories and then modifying theory accordingly. Although inherently quantitative, the logic of aggregation may be applied to merge quantitative and qualitative data. Review methodologies that fall within this logic include meta-analysis, meta-summary, and vote counting ( Sandelowski et al., 2012 ). Meta-analysis is a method in which effect sizes (i.e., a statistic representing the difference between the intervention and control group or between two interventions) are pooled across studies. Bayesian meta-analysis is a specific type of meta-analysis in which the findings from prior studies are updated with new evidence as it is obtained. Meta-summary is a quantitatively oriented approach to synthesizing qualitative data whereby the prevalence of findings across reports indicates the extent of replication ( Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007 ). Vote counting is a method in which the proportion of studies reporting a statistically significant finding or reporting a finding of a minimum effect size is calculated.

How Mixed Methods Literature Reviews May be Applied to Build the Evidence Base for Complex Interventions

In the following section, we review a range of questions that MMLRs may address and illustrate how MMLRs may be applied to build the evidence base for complex interventions (see Table 10.1 for an overview). This section is organized around the conceptualization of complex interventions as the interaction of intervention and implementation activities, contextual factors, and intermediate and longer term outcomes within complex systems.

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Contribute to Understanding Intervention and Implementation Activities

In the implementation science literature, a distinction typically is made between intervention and implementation activities, with intervention activities targeting change in the intervention’s intended outcomes and implementation targeting the adoption or integration of interventions within organizations or systems ( Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health , 2010 ). We maintain this distinction, recognizing that the line between intervention and implementation activities often is blurred for complex interventions, particularly those that target change at the level of policies, systems, and environments rather than at the level of individuals or populations. For example, creating a system to remind physicians to screen for colorectal cancer may be conceived as an intervention activity to improve rates of colorectal screening in the clinic’s population or as an implementation activity to increase physicians’ use of an intervention (colorectal screening guidelines) within a clinic system. Taxonomies have been created for use in systematically reviewing organization-level implementation activities, which include, among others, use of reminder systems and change agents, audit and feedback, technical assistance, coaching, and a range of quality improvement methods ( Effective Practice and Organisation of Care, 2002 ; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005 ; Shojania et al., 2004 ). Michie et al. (2011) created a taxonomy of policy-level activities such as legislating, regulating, and environmental/social planning that may be applied to either intervention or implementation activities.

MMLRs may contribute to describing intervention components and identifying those intervention components (i.e., active ingredients) required to achieve intermediate or longer term outcomes. Abraham and Michie (2008) created a taxonomy of intervention components for use in systematic reviews of behavioral change interventions, which includes components such as providing information, encouraging, setting goals, and providing feedback. Identifying an intervention’s active ingredients will aid in determining those components that must be retained versus those that might be adapted when an intervention is transferred to new contexts ( Baker et al., 2008 ; McKleroy et al., 2006 ). What is referred to here as active ingredients may also be referred to as core elements ( Galbraith et al., 2011 ) or as causal mechanisms ( Pawson, 2006 ). Care should be taken with the term causal mechanism because its use often conflates components of the intervention (i.e., active ingredients) with intermediate outcomes that mediate the intervention’s effects on longer term outcomes.

To illustrate the use of MMLR for identifying active ingredients, O’Campo, Kirst, Tsamis, Chambers, and Ahmad (2011) conducted a MMLR of intimate partner violence screening programs in healthcare settings with the goal of identifying the active ingredients responsible for screening programs’ success in increasing provider self-efficacy and rates of universal screening (program outcomes). They identified four active ingredients (institutional support, staff training, screening protocols, and access to on- and off-site support services) and created a conceptual model to configure the relationship of these ingredients to program outcomes.

MMLRs may also be used to describe components of implementation activities. For example, Rycroft-Malone et al. (2012) conducted a MMLR to configure a beginning theory of active ingredients of “change agents” as an approach to implementing change. The term change agents encompassed the roles of, among others, opinion leaders, facilitators, and knowledge brokers, and was used to refer to individuals who were successful in promoting the adoption and implementation of change (e.g., interventions). Rycroft-Malone et al. found, for example, that serving as a role model for a desired change in practice may be one of the active ingredients by which change agents promote implementation of change.

In addition to identifying the core components of intervention and implementation activities, MMLRs may contribute to providing practical guidance on how to deliver and implement specific interventions. Rogers (2003) described this as “how to” guidance, which may include training and oversight of those implementing and delivering the intervention, deviations between the intervention as planned and delivered, resources required, barriers encountered, how barriers were overcome, and other lessons learned from prior implementations of the intervention ( Baker et al., 2008 ; Leeman, Sommers, Leung, & Ammerman, 2011 ). Efforts to use MMLRs to identify implementation guidance have been limited by the lack of implementation data provided in published reports ( Arai et al., 2005 ; Egan et al., 2009 ; Roen et al., 2006 ).

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Contribute to Understanding Intermediate Outcomes

MMLRs also may be used to identify the intermediate outcomes through which intervention activities both cause and contribute to intended outcomes, a central component of an intervention’s theory of change ( McKleroy et al., 2006 ; Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011 ). Michie et al. (2005) developed a widely used taxonomy of the intermediate outcomes (i.e., mediators) through which interventions cause behaviors to change, such as knowledge, skills, and motivation. To illustrate how MMLRs may be applied to better understand mediators, Leeman, Chang, Voils, Crandell, & Sandelowski (2011) conducted an initial inductive review of qualitative and quantitative observational studies to identify potential mediators of individuals’ adherence to antiretroviral regimens. They then used the identified list of eight mediators (e.g., social support) to guide a deductive mediation meta-analysis of both quantitative observational and intervention studies to assess the strength of evidence in support of their potential role as mediators of intervention effects on individuals’ adherence.

Not all intermediate outcomes function as mediators in that they may not be directly linked into a causal chain between interventions and the intended outcomes. Many intermediate outcomes may best be conceived as one of multiple strands that contribute to or support intended outcomes without directly or indirectly “causing them.” For example, as Figure 10.1 illustrates, although intervening to create more sidewalks may not directly cause improvements in physical activity and health status among the population, it may contribute to and support those changes. Multiple other interventions will need to occur to achieve changes in population physical activity and health status. Lavis et al. (2012) developed a taxonomy of organizational and public policy changes generally supportive of longer term outcomes that include changes to governance (e.g., what entities set policies and how they are enforced), finances (e.g., how providers are remunerated, the fees consumers pay), and delivery arrangements (e.g., who delivers services, where and with what level of support). Supportive intermediate outcomes also include changes in environments and sociocultural mechanisms ( Baxter et al., 2010 ). Developing the evidence base for the value of supportive interventions is difficult because most research tends to “deal with end points and outcomes rather than the many and interrelated social and behavioural, structural and cultural intermediate points along the causal chain” ( Kelly et al., 2010 , p. 1060). MMLRs address this challenge by enabling the development of theories of change and synthesis of evidence in support of the intermediate, interrelated outcomes along the causal chain ( Baxter et al., 2010 ; Kelly et al., 2010 ). Identifying intermediate outcomes will also be helpful in identifying proxy measures of success for interventions ( Lewin et al., 2012 ). Using the example of sidewalks, successful enactment of policy and construction of more sidewalks are both measures of success on the road to increasing population-level physical activity.

Intermediate outcomes in a sidewalk intervention’s effects on health status

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Incorporate the Perspectives of Intervention Decision Makers, Providers, and Recipients

The engagement of numerous actors is critical to the implementation and effectiveness of intervention activities. These actors include the formal and informal leaders who decide which interventions to promote and support; staff, community members, and teams who provide intervention services; and the individuals, social groups, and populations who participate in or are reached by the intervention. Understanding the perspectives of these actors is essential to developing interventions that address problems recognized as high priority and use approaches considered acceptable ( Chalmers & Glasziou, 2009 ; Glasgow et al., 2012 ; Tunis et al., 2003 ).

MMLRs may be used to incorporate qualitative research findings documenting actors’ perspectives with a range of other findings to derive a more complete understanding of problems that may be amendable to intervention. For example, Alderson, Foy, Glidewell, McLintock, and House (2012) conducted a sequential, mixed methods synthesis of patients’ beliefs about depression for the purpose of building the evidence base to better engage patients in depression screening. Using Leventhal’s Illness Representations as a guiding framework, these reviewers conducted a content analysis of interview data, during which they revised the framework to more fully capture findings. They then mapped quantitative findings onto the themes and summarized and explained findings specific to each identified theme.

MMLRs may be used to assess participants’ perspectives on the acceptability of different intervention options. Proctor and Brownson (2012) defined “acceptability” as the perception among potential users that an intervention is “agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory” (p. 265). An intervention’s acceptability will likely play a critical role in determining whether it is used in practice, which is critical to determining its potential effectiveness in improving health ( Bowen et al., 2009 ). To illustrate MMLRs’ use in advancing understanding of acceptability, Harden, Brunton, Fletcher, and Oakley (2009) reviewed reports of controlled trials of teenage pregnancy prevention interventions and then reviewed findings from research examining teenagers’ perceptions of the need and appropriateness of different approaches to intervening. They aligned the findings from the two reviews to assess the extent to which existing interventions addressed the needs and concerns of teenagers.

MMLRs may be applied to better understand individuals’ experience of receiving an intervention. To illustrate, Voils, Sandelowski, Barroso, and Hasselblad (2008) aggregated qualitative and quantitative findings on factors influencing HIV-positive women’s adherence to their antiretroviral therapies. They initially aggregated the qualitative data inductively to identify factors and their frequencies across studies. They then integrated the quantitative and qualitative data to ascertain their relationships, that is, whether findings confirmed, refuted, or extended each other. For example, from the review of qualitative findings, they found that women reported greater success with incorporating regimens into their routine schedules when the regimens were less complex, and this was confirmed by the finding from quantitative studies that having a regimen with less (as compared to more) complex dosing was associated with greater adherence.

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Contribute to Understanding How Interventions Interact with Contexts to Affect Outcomes

Understanding how interventions interact with contexts to affect outcomes is essential to assessing an intervention’s generalizability. Understanding the interaction of interventions and contexts also is needed to determine when intervention, implementation, and/or context may need to be modified or adapted to enhance intervention/context fit and thereby achieve intended outcomes ( Glasgow, 2008 ). The effects of interventions vary across contexts because contextual factors modify (i.e., moderate) interactions among activities, mediators, and outcomes ( Ramsay, Thomas, Croal, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2010 ). Contextual factors at the level of intervention recipients may include, for example, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, literacy levels, or readiness to change. Contextual factors also include the characteristics of the complex systems in which interventions occur, for example, multiple interacting social networks, organizational infrastructures, socioeconomic pressures, and incentives ( Damschroder et al., 2009 ). MMLRs can be used to synthesize evidence on how contextual factors interact with intervention and implementation activities, and intermediate and longer term outcomes. This evidence may be synthesized via aggregation or configuration to develop theory to explain how activities interact with contexts to affect intermediate and long-term outcomes.

Wong, Greenhalgh, and Pawson (2010) , for example, applied a configuration logic to develop theory to explain what types of Internet-medical education worked for whom under what circumstances. They then used vote counting to quantify the number of studies that either supported or refuted specific theoretical constructs. They determined that physician and medical student response to Internet courses was contingent on the fit between their needs and priorities and the technical attributes of the course.

Contandriopoulos, Lemire, Denis, and Tremblay (2010) conducted a MMLR to configure interrelationships among actors, contexts, and knowledge in interventions aimed at influencing behaviors or opinions through the communication of information at the organizational or policymaking level. They identified three central dimensions of context: the extent of polarization in actors’ perceptions of the problem and its potential solutions, the way intervention activity costs were distributed within the system, and characteristics of the social networks through which information was communicated. Based on review findings, they posited that the most effective approach to promoting knowledge use (i.e., implementation) would be contingent on the interaction between the extent of polarization and distribution of costs.

For an intervention to have an impact on a population’s health, it must not only be effective but also have broad reach, particularly to the populations at greatest risk and the providers and settings that serve those at-risk populations. To have maximal impact, interventions also need to be implemented with fidelity to their active ingredients and maintained over time ( Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003 ; Rychetnik et al., 2002 ). Therefore, to ensure population impact, evidence is needed on the contextual factors that influence whether providers, settings, and systems adopt an intervention, implement it with fidelity, and maintain it over time.

Leeman et al. (2010) conducted a MMLR to identify barriers and facilitators encountered in implementing antiretroviral therapy interventions. They configured implementation to include providers delivering the intervention and participants enrolling in, attending, and continuing the intervention over time. They then explored the effects that contextual factors had on each link in the implementation chain, with contextual factors including characteristics of the intervention, intervention participants and providers, and settings. Based on review findings, the researchers developed a beginning theory that posited that individuals with HIV would be more likely to enroll in interventions that protected their confidentiality and to attend when interventions were scheduled to meet their needs and when they facilitated a strong relationship with the intervener. Dropout rates were likely to be lower for individuals who had less (as opposed to more) prior experience with antiretroviral therapy and were likely to be higher when interventions were integrated into existing delivery systems than when offered as stand-alone interventions (Figure 10.2 ).

Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Contribute to the Identification of Promising Interventions

Numerous scholars have called for a shift from the prevailing approach of testing the internal validity of researcher-developed interventions and then attempting to translate them into real-world practice settings (e.g., Kessler & Glasgow, 2011 ). This approach has been critiqued not only for its limited attention to external validity but also its inattention to viability validity ( Chen, 2010 ). In designing interventions, researchers have often not attended to whether ordinary people, particularly those in greatest need of an intervention, will participate in or be reached by the intervention or whether busy clinicians, educators, and other practitioners will be able to implement it in their practice settings ( Klesges, Estabrooks, Dzewaltowski, Bull, & Glasgow, 2005 ). To identify more viable interventions, some scholars are advocating looking to identify and carry out interventions that have achieved high levels of reach, adoption, and implementation (i.e., have high viability validity) and then formally testing those interventions in studies ( Chen, 2010 ; Leviton, Khan, Rog, Dawkins, & Cotton, 2010 ). MMLRs may be used to identify promising interventions. For example, Brennan, Castro, Brownson, Claus, and Orleans (2011) reported on methods they were using in a systematic review of both research-tested and practice-based interventions for the purpose of identifying promising policy and environmental change interventions to prevent obesity in children.

Contextual factors influencing each step in an implementation chain

Challenges in Conducting Mixed Methods Literature Reviews to Develop the Evidence Base for Complex Interventions

Like other systematic reviews, MMLRs entail the formulation of purpose and research questions, search for and retrieval of relevant literature, extraction and evaluation of data from retrieved literature, and analysis and integration of extracted data ( Cooper, 2010 ). These activities are not sequential but rather cyclical in that one activity (e.g., searching for literature) often leads to revisions in a prior activity (formulation of purpose).

Multiple resources are available that provide guidance on how to conduct mono- and mixed methods systematic reviews of quantitative and/or qualitative research findings (e.g., Cooper 2010 ; Pope, Mays, & Popay, 2007 ; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007 ; Sandelowski et al., 2012 ). In previous publications, we have addressed the challenges of conducting MMLRs such as managing data derived from different sampling (i.e., purposeful vs. probability) and data collection imperatives (open vs. closed ended), aggregating data at the study vs. subject level, and data that were adjusted versus unadjusted ( Crandell, Voils, & Sandelowski, 2012 ; Sandelowski, Voils, Crandell, & Leeman, 2013 ; Voils, Crandell, Chang, Leeman, & Sandelowski, 2011 ).

Accordingly, we highlight here only those issues distinctive to conducting MMLRs for the purpose of building the evidence base for complex interventions. Specifically, we address issues related to the extraction of findings from primary research reports and to aspects of MMLRs that have been the subject of critique, namely limitations in the way reviewers address the quality of included studies, describe their methods, and link review findings to their sources (Table 10.2 ).

Extracting Findings from Primary Research Reports

When conducting systematic reviews, reviewers typically separate contextual data from data on the intervention’s effects. In the predominant approach to data extraction, reviewers create, pilot, and then use an extraction form to standardize the collection of data on study sample, context, methods, and findings. In the typical extraction form, findings are separated from the information in other sections of the form that make those findings meaningful. Indeed, Pawson (2006) argued that the best way to avoid separating findings from context was to reject the data extraction process altogether. In his realist synthesis approach to MMLR, Pawson argued that rather than extracting data and then reintegrating it, reviewers should configure the findings from each study and then look for demi-regularities across the configurations created for included studies (e.g., Jagosh et al., 2012 ). Concerns have been raised, however, that this approach may be very time-consuming and the findings may not justify the resources required to generate them ( Sheldon, 2005 ).

Sandelowski et al. (2012) developed an approach to the extraction of primary study findings intended to preserve key aspects of the context of those findings in a comparable form regardless of whether they were produced in qualitative or quantitative studies. Findings from qualitative and quantitative studies are transformed into complete and portable statements that anchor those findings to features likely to be most relevant to understanding the context of their production. These include aspects of the sample, the source of the finding (e.g., mother-reported child depression vs. child-reported child depression), time, comparative reference point (e.g., mothers vs. fathers), magnitude and significance, and study-specific conceptualization of phenomena (e.g., family functioning defined as balance between cohesion and conflict). An example of such a statement of findings from a quantitative study is: In families with infants with a congenital heart defect, more mother-reported family cohesion immediately after diagnosis was significantly associated with more father-reported family cohesion one year after diagnosis; neither mother- nor father-reported family cohesion was related to marital satisfaction at any time. All statements addressing family cohesion—whether derived from qualitative or quantitative studies—might then be grouped together to ascertain their topical (e.g., about families with infants as opposed to older children, about congenital heart defect as opposed to other condition) and thematic (whether they confirm, refute, or otherwise modify each other) relationships to each other in preparation for synthesizing them on the basis of common relationships.

Applying Quality Criteria

Methodological problems within the primary studies included in a systematic review are a central threat to the validity of findings for all types of systematic literature reviews. Mono-method reviewers often minimize this potential for bias by excluding studies that fall below predetermined criteria for methodological quality. Yet this a priori, gate-keeping approach to research synthesis has recurrently been shown to be idiosyncratic, unreliable, and a major reason why reviews often cover only a fraction of the potentially relevant research literature available in a target domain ( Cooper, 2010 ; Ogilvie, Egan, Hamilton, & Petticrew, 2005 ; Pawson, 2008 ; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007 ). Because the goal is to maximize the amount of data available, MMLR reviewers typically choose not to exclude studies a priori for quality reasons. With the goal of maximizing the available data, reviewers may include findings from pilot studies conducted preliminary to more rigorous tests of an intervention. By design, these studies may provide valuable information on intervention acceptability, feasibility, and approaches to increasing the fit between the intervention and variations in context ( Bowen et al., 2009 ). Reviewers may also include studies that employed quasi-experimental or case study designs to assess and explore relationships between interventions and outcomes and the range of contextual factors that may influence those relationships. Although the breadth of findings will contribute to the richness of the MMLR, the design and execution of included studies may fall short of meeting established criteria for methodological rigor in the varieties of qualitative and quantitative methods used. In their review of systematic literature reviews, Bouchard, Dubuisson, Simard, and Dorval (2011) found that authors of MMLRs were significantly less likely to account appropriately for the quality of included studies than were authors of mono-method quantitative reviews.

Yet there is no consensus on the best approach to judging the methodological quality of studies included in MMLRs ( Dixon-Woods et al., 2005 ). Efforts to establish quality criteria are challenged by the absence of widely agreed-on and reliable standards for evaluating qualitative studies ( Sandelowski, 2012 ). They are further challenged by the fact that MMLRs will require different criteria for different types of included studies and because the importance of different aspects of study design and execution varies depending on the purpose of the review ( Lewin et al., 2012 ; Pope et al., 2007 ). The problem of study quality becomes even greater when MMLRs include literature other than empirical research reports, such as theoretical papers and grey literature (e. g., unpublished or conference reports). Establishing a standardized approach to evaluating quality may not even be appropriate for MMLR, given the variety and breadth of study aims and methods at the level of both the MMLR and the included studies.

Reviewers have multiple options for addressing the quality of the studies included in a MMLR. First and foremost they need to consider the purpose of their reviews and the types of studies to be included and then select quality criteria that are most relevant to assessing validity within the distinct context of their MMLR. Different criteria will apply if the purpose of the review is to determine the weight of evidence in support of the relationship between two phenomena (e.g., gender and adherence) than if the purpose is to explore contextual factors that may explain differences in implementation. Next, reviewers need to identify criteria appropriate to their review and then justify the selected criteria in their reports of MMLR findings. A vast literature details characteristics of study design and execution that are most relevant to assessing the validity of study findings (e.g., Boeije, van Wesel, & Alisic, 2011 ; Higgins & Green, 2011 ; Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths, & Johnson-Lafleur, 2009 ; Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, 2013 ).

As with other types of systematic reviews, researchers conducting MMLRs may document concerns related to the quality of the primary literature included and then address those concerns during analysis ( Pawson, 2006 ) by addressing quality appraisal as a moderator of review findings or by giving greater weight to findings from studies that are methodologically stronger ( Pope et al., 2007 ). Reviewers also may include critical exploration of threats to validity as an integral part of the synthesis process. Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) incorporated a critical review of methods into an inductive synthesis of literature on vulnerable group’s access to healthcare and identified a concern with the predominant approach used to conceptualize and measure access. They then developed an alternative conceptualization of access they used to guide the subsequent phase of the review.

Explicating Mixed Methods Literature Reviews Methods

Of necessity, MMLRs of complex interventions often are methodologically and conceptually complicated. Reviewers retrieve a broad variety of literatures, use multiple synthesis methods, and employ an iterative approach to both retrieval and synthesis. The complexity of review methods challenges reviewers to explicate methods clearly and completely within the page limits allowed by most journals. Reviewers conducting effectiveness and other types of mono-method reviews often have the advantage of predetermined protocols that prescribe the overall design and methods for the review. The Cochrane Collaboration ( Higgins & Green, 2011 ), for example, provides reviewers with 22 chapters of guidance on how to structure their effectiveness reviews. In contrast, MMLR is a fairly new field with a growing menu of diverse and evolving designs and methods. MMLR by its very nature offers reviewers the opportunity and the challenge to select, revise, and shape their methods as the review progresses. This provides reviewers with the opportunity to select and develop approaches to fit the available literature, the data within that literature, and their evolving research purposes and questions. Although this flexibility enhances reviewers’ capacity to capture the evidence base for complex interventions, it may challenge their efforts explicitly to communicate the details of their methods.

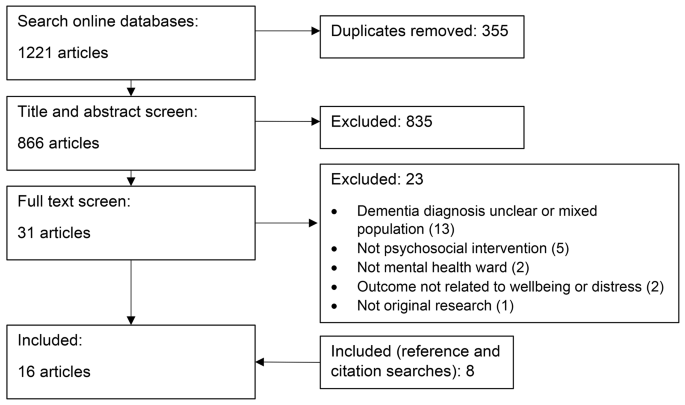

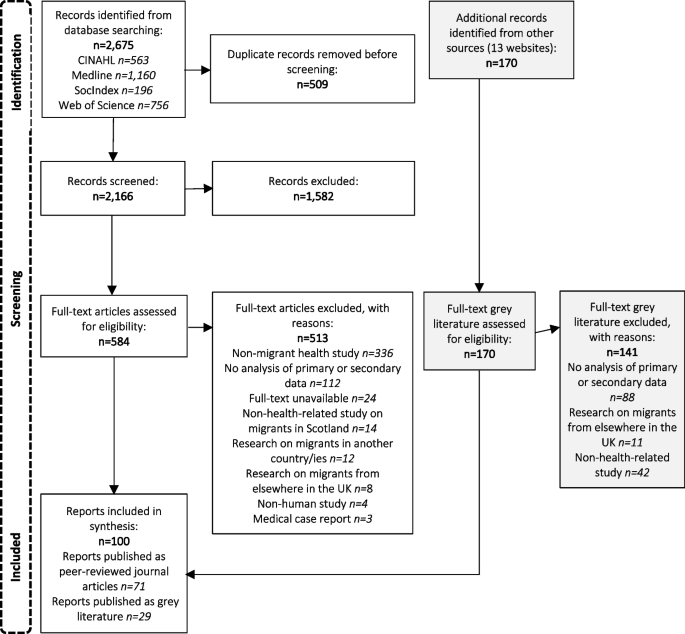

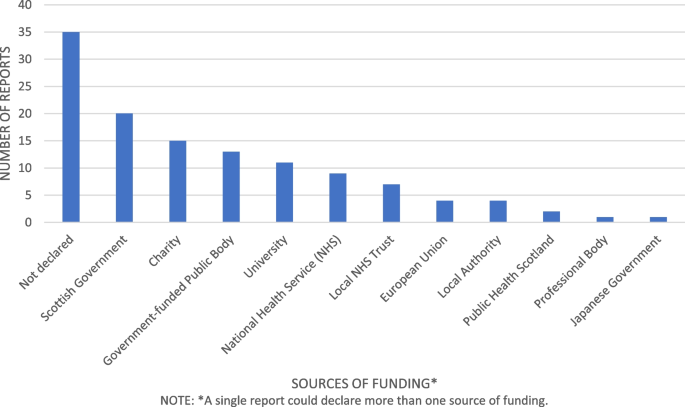

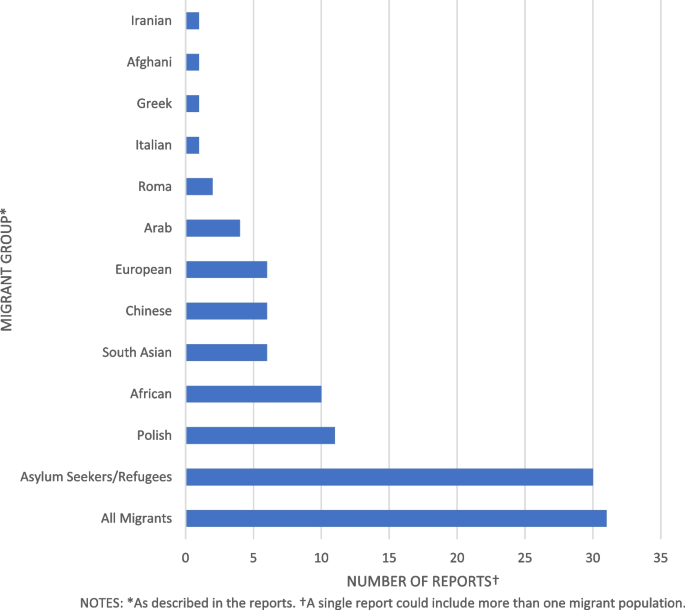

The comprehensive and iterative nature of MMLRs mandates that reviewers take care to document and justify their methodological decisions in ways that are explicit but that accommodate journal word limits. Reviewers may make their methods more explicit by following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for documenting publication yields and exclusion decisions at each phase of the search and retrieval process ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; e.g., Alderson et al., 2012 ). Wong et al. (2013) proposed an approach similar to the PRISMA guidelines that reviewers conducting realist MMLRs may use to depict their iterative literature retrieval process within a single flow diagram (see Figure 10.3 ). Transparency also is enhanced by describing who extracted what data and from which parts of the reports, if and how data were transformed during the extraction process, and how discrepancies between extractors were reconciled.

Adapting the PRISMA approach to document an iterative MMLR search