Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy

Main feature of organization, strategic products and current mission, internal and external environments of the lego group, internal environment – swot value change of the company, external environment – pestel, porter five forces, power interest matrix of the lego group, new strategic directions for the organization, works cited.

The Lego Group is a toy-manufacturing company which is based in Billund, Denmark. The company was founded as a family organization in the year 1932, by Ole Kirk Christian. Today, the company stands high as a global player in the world of toys, among other strategic entertainment products (LeGoff 557).

Initially, Lego started as a manufacturer of ironing boards, toys, stepladders, and stools. Among these products, the wooden toys have been the best selling items, thus according the firm a strong reputation in the entertainment business. By the year 1949, the firm started manufacturing early versions of the popular LEGO plastic bricks and this was a strategic approach by the organisation, considering the fact that plastics had just greeted the markets as a new material (Simoes and Dibb 219).

However, the outcome was not what the company managers had anticipated, since the public was a bit hesitant in accepting the new material. The company would rapidly gain popularly in most parts of the world, as a result of progressive development of its products. For instance, the basic bricks were sustained with extra figures and features, in a manner that diversified the playing opportunities for children.

The company’s sales and profit scales were rapidly taking a positive charge between 1950 and 1970. However, the period between 1970 and 1990 proved to be a difficult moment for the company, owing to the serious economical implications that greeted the world then, following the oil crisis of the time.

In the course of this era and the period that followed afterwards, the Lego Group underwent serious fluctuations, due to a number of reasons which included; rapid change in the business environment witnessed at the time, complications in logistic matters and financial control, and the extended times that would be required to run into the future plans of the company.

Among the many problems which threatened to shake the firm’s potential, was the issue of the rising competition from much bigger companies such as Hasbro and Mattel (Hicks 41). Other new firms such as Sony, Activision, and Nintendo, who had just ventured the scene with more advanced electronic products, also posed great challenge to the productivity of the Group.

In this regard, the company’s only survival option in the competitive market was to adopt a strategic development plan that would see it come up with new and more exciting products. According to Claus, Riggs & Sekeran, the toy company enjoys a wide range of products that are fit for children of all ages (71).

These products are grouped in various categories, and some of the latest developments include video gaming, pre-school products, play themes, bricks, licensed products, and educational-based products for children, just to mention but a few. This is a clear indication of how the company has managed to remain high in the current competitive business of toy products.

The Lego Group was actively been involved in several turnaround attempts for the better part of 1990s and in the early 2000s, but with little success. No one could have foretold a possible solution to the progressive issues which appeared to claim the company, until towards the end of the year 2004, when a glimpse of hope shone onto the firm.

It was in the course of this period when the company’s serving CEO, Kjeld, took on more involvement in strategies that helped to identify the factors responsible for the company’s downsizing. This helped in the design of effective strategies that would eventually see the firm come back on track. The design and implementation of these strategies was based on the company’s organization, management and business expectation plans.

This involved the replacement of over three quarters of the senior management team with a new batch. Other strategies would be centered on the firm’s operational systems, among other key interventions.

For instance, a thorough revision was carried out on the cost and the supply chain operations of the company, and major changes were inflicted on the sectors right away. More importantly, the Lego Group had realized that working alone would not take them anywhere, and this would see them cooperate with licensing partners in the widely acclaimed gaming sector.

These interventions were sustained with a progressive development of the company’s products, to fit the demands of the modern era. The company has shown steady advancements lately, as a result of these interventions. The climax of this success was realized in the 2008-2009 financial year, which saw the company registering the biggest rate of growth in sales and profits, since the year 1981.

With these positive outcomes, there can’t be any doubts that the Lego Group is now back to its place in the development of children’s creativity, after several years of financial loss and failure (Irani, Sharif & Love 59). The objective of the company is to develop innovative products to meet the expansive consumer requirements, as they occur in the market.

As part of their recovery strength, the Group has reclaimed its position in the global listings, where it is ranked among the top five toy companies, with an approximate value of 4.8 percent in market shares. Lego’s success can also be associated with their mission, which aims at inspiring the current generation of children to be able to explore and challenge their own potential in creativity (Stacey 79).

This has been achieved through the group’s brand values, which are tailored on aspects meant to bring a significant impact on children. Some of these aspects would include things such as quality, imagination, fun, creativity, caring, and learning.

Lego group is a good example of the international companies that have managed to balance the nature and constraints of the internal and external environments, to make a notable difference in the current competitive world of business. From the perspective of various reports about the company, it is apparent how the toy company has reacted in adapting and utilizing the potential offered by its internal resources, in meeting the demands of its external environment.

According to Dyllick, Thomas & Hockerts, the company’s current strategic development has been achieved through the focused leadership of its former CEO, Kjeld Kirk (139). A better part of this success however, has been reached upon through the feedback which had been received regarding the internal competencies of the firm and its external operating systems.

A major tool that can be used to assess the overall potential of a firm is the SWOT analysis structure, which stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. A SWOT analysis basically considers two main parts; a company’s inward elements which normally constitutes of its strengths and weaknesses, and the attempts to consider the way these factors would come to fit against the external aspects of an organisation’s threats and opportunities.

The company’s key strengths are commonly associated with its constant ability to apply the concept of brand recognition in all its products and services, without having to compromise their core values. The company also maintains a close mutual relationship with its suppliers and retailers, and this gives it a powerful business advantage over its rivals in the industry.

The toy market is an industry bulging with a big number of competent players, but Lego’s products and services are the most preferred by majority of the people in the world (Oliver and Roos 911). This is due to their effective leadership in the development of a wide range of children products that have been praised for quality and originality. The newest products by the company are real manifestation of how the power of innovation applies, in meeting their goals and objectives in business.

Brand heritage is another strength which has succeeded at keeping the company ahead of its rivals in the industry (Hatch and Schultz 597). This is evident in how the company’s products are manufactured to fit in their brand values, which are aimed at making a significant impact on the lives of children all over the world.

Lego’s weaknesses in business can be observed through a number of ways. For instance, even though there have been serious attempts by the company to diversify its products, the company has been poor in technology and IT related matters compared to other competitors, who have fully embraced the power of technology in making their products more enticing to the users in the new media age (Schau 43). Lego Group has also been operating through large toy retailers, and this has been one of their biggest drawbacks in the market.

The large retailers are effective marketing outlets, but they normally operate on high costs and this is likely to deprive the company of substantial amounts of money in profits. More importantly, the company has failed to understand the marketing concepts which are in line with their consumers all over the world.

In other words, Lego group seems to be lacking full understanding of their consumer preferences in the market, and due to this lack of a strategic fit, they have often ended up losing more sales to their competitors in the market, who are well informed of the consumer needs regarding toys and gaming products.

It is also apparent that, Lego Group lacks the ability to effectively translate potential strengths into implemented strategies. This actually explains the company’s gradual response to financial and management issues, among other problems which have affected the company previously (Hölzl 39).

Opportunities & Threats

The company’s notable opportunities and threats can be linked together as key aspects which the company can utilize in achieving its goals and mission in the toy business. According to Schultz and Hatch, while the company has been widely acclaimed all over the world for its production of toys and other children products, there has been a decline in the sales of its traditional toys which constitutes the largest part of their products, due to the increasing attention of children on devices from other companies, that are more electronic (21).

The other biggest threat of the group is the growing number of giant competitors, who are utilizing every opportunity possible to thrive in the industry, thus making it one of the most competitive sectors in the world (Johnson 11). However, Lego Group has always seen these threats as opportunities for further developments in business.

New developments and increase on products has always remained the biggest opportunity to the company. More importantly, as a result of the rapid competition in the market, the company has managed to come up with numerous categories of products, a key strategy which has enabled it to be able to meet the needs of children in the modern era of technology.

Porter’s five forces analysis is observed to have a significant impact on a business, in relation to elements of the external environment (Michael 13). These forces include level of rivalry, power of suppliers, threat of entrants, power of buyers, and threat of substitutes. Each of these five forces is considered individually in assessing and analysing the external environment of the company in this case.

Level of rivalry

The level of rivalry is quite intense and strong for the Lego Group. While it is clear that the company enjoys a strong position in the industry, with relatively few giant competitors, it should be considered that they are taking part in a broader market of toy production, which also includes key players in the electronic sector, such as Sony and Nintendo, among others (Martin 84).

Power of suppliers

The company, whose main products are largely based on standardised inputs, has an average power of suppliers. However, it should be noted that, the power of suppliers is likely to go up, in case the company decides to major in more sophisticated areas of productions, such as games or films.

Power of buyers

The power of buyers is relatively high for the Lego Group, with minimal costs between alternative products.

Threat of entrants

As it would be expected, the toy product industry normally requires huge investments of time and money, in a number of ways that include things such as business capital, research funds, and development costs. All these serve as obstacles to entry in the industry, thus restricting the number of new entrants in the sector. In that case, there is a relatively low threat of new entrants in the wider entertainment market, and this offers the Lego Group a much stronger bargaining power over majority of its competitors in the market.

Threat of substitutes

This is arguably one of the biggest threats facing the entertainment product company today. Even though the company is said to have developed electronic products such as video and games, there is still evidence that some of the company’s products are still made in the traditional form. This has the meaning that, the company is faced by a big threat, given that users are likely to substitute between traditional toy and gaming products through to the ones that are made into electronic features.

It is also apparent that the Lego group has touched many people with its products and services in the entertainment sector. Through the engagement of the right people in its management and productivity systems, the company has made a big success in its mission and objectives in business (Beal 29).

As it would be observed in the above internal and external analyses, the company has tried to implement a number of strategies, in order to influence and attract people on their products. Through these interventions, the company has successfully managed to impact a large number of people from all over the world, with both electronic and alternative traditional products for children entertainment. Among other key players in the market, the company has a high interest on its stakeholders and the community.

The firm recognises these as the people who play the greatest role in helping them achieve their business goal and for that reason it treats them with much respect. Both the shareholders and the people from the diverse community have a positive impact to the company’s financial interest and what motivates them most is to get nothing less of the best from the company. In that respect, the Lego group is fully engaged in putting the necessary efforts which are needed to satisfy these significant groups.

The Lego group is arguably one of the most successful companies in the toy manufacturing industry. Through a wise interaction of its internal and external systems, sustained by the effective management, the company has gained a sustainable competitive advantage over many of its rivals in the market.

However, there are numerous strategic directions which the product company can utilize, to be able to maintain a more sustainable competitive advantage over its rivals.

The Lego Group may have amassed great reputation and success in the entertainment sector, but changing the company into an all-time winner in the global toy market is something that would require much effort, from the company (Schroeder 54). Some of these efforts would tend to involve numerous aspects of strategic management, whose significance in business has often been underestimated.

Some of the strategic directions which the company can incorporate in its operation systems would include; a focus on international opportunities, expansion of digital systems and strategies, constant focus on cost, expansion of target markets, widening of product range, and focus on effective online distribution strategies.

The Lego Group may have made significant attempts in trying to incorporate some of these strategies in their routine business operations, but there is still room for improvement which can be achieved by revising these strategies over and over, to eliminate all the problems which continue to pose a big challenge to the company’s productivity and accountability in children’s toy and entertainment products (Morgan 45).

For instance, the company should focus on the many opportunities provided by the international community and try to utilize them effectively. A good way of achieving this goal is by ensuring that the toy products are manufactured and distributed in all regions of the world, where they are needed most by families, as a key engagement for their little ones.

It should also be considered that, things are changing with the times nowadays and in that respect, expansion of digital systems and strategies is very crucial for the development of the company to fit in the demands of the modern era, which is defined by technology (Cooper 75). To be able to comply fully with this call of modernity, the company should try to ensure that all their products are made into electronic features, to fit the growing demands of technology (Laudon and Traver 18).

It is also necessary for the company to make a constant focus on cost matters, to ensure that there is a two-sided benefit between the producer and the consumers. More importantly, there is also the need for the Lego Group to conduct extensive research on new developments to widen its product range.

Through a corporate level strategy aimed at increasing international coverage and product diversity, the company would be certain to realize more sales and profits out of its toy products. The company should also consider the vast potential business opportunities that are offered by the upcoming trend of e-commerce, and try to utilise these online mediums as effective distribution channels for their wide range of products.

Apart from these strategies, the Lego Group should also try to make good use of other strategic tools in today’s dynamic business world, such as important business information that would provide them with good lessons on how to achieve and uphold a sustainable competitive advantage in business affairs. All these strategies, sustained with the magical touch of an effective organizational management style are likely to bear promising results in the future operations of the company.

Beal, Reginald. Competitive Advantage: Sustainable or Temporary in Today’s Dynamic Environment? Tallahassee, Florida: School of Business and Industry, 2001. Print.

Cooper, Robert. “New products: the factors that drive success.” International Marketing Review 11. 1 (1994): 60-76. Print.

Claus Brian, Riggs Neil & Sekeran Hari. Development of a low cost instructional platform for submersible design: Electrical and Computer Engineering . New York: IEEE, 2009. Print.

Dyllick, Thomas & Hockerts Kai. “Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability.” Business Strategy and the Environment 11 (2002): 130-141. Print.

Hatch, Mary and Schultz, Majken. “Toward a theory of brand co-creation with implications for brand governance.” Journal of Brand Management 17 . 8 (2010): 590-604. Print.

Hicks, Mark. “Collaborate to innovate?: getting fresh small company thinking into big company innovation.” Interactions 17. 3 (2010): 39-43. Print.

Hölzl, Werner. The evolutionary theory of the firm:Routines, complexity and change . Vienna: Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, 2005. Print.

Irani Zahir, Sharif Amir & Love Peter. “Transforming failure into success through organisational learning: an analysis of a manufacturing information system.” European Journal of Information Systems 10. 1 (2001): 55-66. Print.

Johnson, Whittington. Exploring Strategy . Harlow: Pearsons Education, 2011. Print.

Laudon, Kenneth and Traver, Caroh. E-Commerce Business, Technology, Society . Boston: Adison Wesley, 2008. Print.

LeGoff, Daniel. “Use of LEGO as a therapeutic medium for improving social competence.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 34. 5 (2004): 557-571. Print.

Martin, Fred. Circuits to control: Learning engineering by designing LEGO robots . Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1994. Print.

Michael, Porter. Commerce Strategy . Boston: Freepress, 2004. Print.

Morgan, Gareth. Images of Organisations. London: Sage Publications, 2006. Print.

Oliver, David and Roos, Johan. “Decision-making in high-velocity environments: The importance of guiding principles.” Organization Studies 26. 6 (2005): 889-913. Print.

Schau, Hope. “How brand community practices create value.” Journal of Marketing 73. 5 (2009): 30-51. Print.

Schroeder, Jonathan. Brand culture . United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publishers, 2006. Print.

Schultz, Majken and Hatch, Mary. “A cultural perspective on corporate branding.” Brand culture 13. 5 (2006): 17-26. Print.

Simoes, Claudia and Dibb Sally. “Rethinking the brand concept: new brand orientation.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 6. 4 (2001): 217-224. Print.

Stacey, Ralph. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics . London: Pitman Publishing, 1993. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, July 31). Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-the-lego-group-working-with-strategy-case-study/

"Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy." IvyPanda , 31 July 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-the-lego-group-working-with-strategy-case-study/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy'. 31 July.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy." July 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-the-lego-group-working-with-strategy-case-study/.

1. IvyPanda . "Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy." July 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-the-lego-group-working-with-strategy-case-study/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Lego Case Study: The Lego Group Competitive Advantage & Strategy." July 31, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-the-lego-group-working-with-strategy-case-study/.

- Adults' Interest in Lego and Six Brand Touchpoints

- The Lego Firm's Corporate Social Responsibility

- The Lego Company's Story of Innovate or Die

- Lego Company's Business Strategy and Information Resources

- The Lego Company's Inventions and Reinvention

- Lego's Competitive Environment

- Lego Company’s Performance Management

- The Lego Group and Its Sacred Cows

- LEGO Competitive Strength Analysis

- The LEGO Group Strategy to Influence Performance

- MAC Cosmetic: External Factors Effect on Strategic Plans

- Kelda’s SAP Implementation

- Procter and Gamble: Improving Customer Value Through Process Redesign

- Strategic Management of the BMW

- Marketing Services: MK Restaurant

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Innovating a Turnaround at LEGO

- David Robertson and Per Hjuler

Five years ago, the LEGO Group was near bankruptcy. Many of its innovation efforts—theme parks, Clikits craft sets (marketed to girls), an action figure called Galidor supported by a television show—were unprofitable or had failed outright. Today, as the overall toy market declines, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing, up 19% and 30% respectively in […]

Reprint: F0909B

Though the overall toy market is declining, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing—largely because the company revamped its innovation efforts to align with strategy.

Five years ago, the LEGO Group was near bankruptcy. Many of its innovation efforts—theme parks, Clikits craft sets (marketed to girls), an action figure called Galidor supported by a television show—were unprofitable or had failed outright. Today, as the overall toy market declines, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing, up 19% and 30% respectively in 2008.

- DR David Robertson ( [email protected] ) is a professor of innovation and technology management at IMD. Per Hjuler ( [email protected] ) is the LEGO Group vice president of product and marketing development. For more, visit www.innovationgovernance.net.

Partner Center

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- HBS Case Collection

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 23

About The Authors

Jan W. Rivkin

Stefan H. Thomke

Related work.

- July 2013 (Revised February 2014)

- Faculty Research

Jørgen Vig Knudstorp: Reflections on LEGO's Transformation

- LEGO By: Stefan Thomke and Jan W. Rivkin

- Jørgen Vig Knudstorp: Reflections on LEGO's Transformation By: Stefan H. Thomke

Can LEGO Snap Together a Future in Asia?

As one of the largest toy makers in the world, the LEGO Group has been riding high in America and Western Europe. To grow, however, LEGO recently faced a decision familiar to many other multinationals: should the company shift from manufacturing in a few sites in Europe and North America, and build a factory in a low-cost location in Asia?

Such a move over the next five to seven years would be full of risk, especially considering LEGO has had a checkered history of expansion—one such effort almost led to bankruptcy. So Harvard Business School Assistant Professor Anette Mikes knew she had a unique opportunity to study strategy in the making when she headed to the company's Denmark headquarters last year.

The case study The LEGO Group: Envisioning Risks in Asia , coauthored with HBS research associate Dominique Hamel, vividly details sitting in on the toy maker's scenario-planning meeting, where top execs tested whether the current business model was robust enough for the challenges lying ahead.

While LEGO has sold toys in Asia for three decades, there is serious potential to improve market share and maybe even outgrow North America and Western Europe, which together accounted for 72 percent of all LEGO sales in 2011.

"LEGO is a huge success story in Western Europe and America," Mikes says. "The question is will they be able to repeat this success story in Asia?"

The company is a fascinating business study for its extreme ups and downs. Founded in 1932 by Danish carpenter Ole Kirk Kristiansen, the family-owned company grew over the decades, moving from wooden toys to plastic "bricks," the building blocks of its construction sets. The products are designed around play themes such as urban landmarks, trains, and undersea exploration. LEGO also licenses properties from blockbuster films such as Star Wars and Harry Potter .

“It's really easy for them to be nimble and meet demand”

LEGO's ambition has at times exceeded its reach. By 2004, the company's overdiversification into theme parks, book publishing, and specialized toys sparked a colossal tumble . A recapitalization of the company led to a fairy-tale rebound as the group returned to selling its core building sets. LEGO earned $1.0 billion as sales approached $3.5 billion in 2011, and in 2012, it overtook Hasbro as the world's second-largest toy manufacturer.

What's The Scenario?

To sharpen its "Stepping Up in Asia" strategy, LEGO executives employed scenario planning as a key tool to weigh potential outcomes. The technique, which has been around since the 1960s, fell out of favor in recent decades. In his 1994 book, Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning , Henry Mintzberg argued that strategic planning techniques (such as scenario planning) do not work well for organizations because they typically fail to engage business managers and remain detached from everyday action.

But Mikes says the popularity of scenario planning is reemerging, as companies navigate the uncertainty in global markets and a diminishing control in their environments generally. For companies to "break through the illusion of certainty," she says, they must embrace imaginative, creative thinking to better prepare for the future, with scenario planning being one important tool to foster that.

While teaching the case, Mikes asked students to participate in their own scenario- planning exercise, deciding actions to take in Asia if they ran LEGO. Importantly, students had to figure out what to do with the scenarios they came up with. Would they bet on one of the scenarios? Would they exert influence to shape the environment? Or would they try to hedge?

"They had to imagine themselves making a decision," Mikes says. "I asked them to be the CEO: 'Now that these scenarios have been presented to you, what are you going to do next?' "

Assessing The Risks

Both the managers and the students had to consider areas of potential risk for LEGO in Asia, including:

Uncertainty of market growth forecasts. LEGO senior director John Kelley argues in the case that to supply the most optimistic sales forecasts in Asia, the company would need to build costly new capacity for warehousing, packing, and—possibly—molding. But what if demand never came despite the expense?

LEGO's director of strategic risk management, Hans Laessøe, pointed out the uncertainty of even short-term global demand forecasts. Out of the 20 themes launched by LEGO each year, it is likely that one will fall short of forecast by 50 percent while another sells twice what was expected. "We just don't know in advance which ones will be those two," he said.

On the plus side, LEGO's strength is flexible production. "If SKU2 is doing well but SKU7 is failing, all they need to do is repackage the bricks into the boxes of the one that's selling really well," Mikes says. "It's really easy for them to be nimble and meet demand."

The risks of product acceptance. LEGO's standard is to create global products, with 95 percent standardization and only 5 percent variation in its boxes, mainly in packaging—to suit local shoppers' tastes. The trick is to keep this high degree of standardization while creating new global themes with appeal in the various Asian markets.

Products that are big hits in the West are not always hits in Asia, Mikes says. Introducing more localized products coupled with licensing agreements linked to specific movie franchises might be an option, but an expensive one. The company also had to consider that "diminishing play time and the threat of a disruptive educational product innovation could be our biggest risk in Asia," as one LEGO executive put it.

Uncertainties of Asian retail. Many Asian countries lack a developed retail network. And while big chains like Walmart and Tesco are growing in China, the country still relies on many small retailers, few of which use common operations metrics such as margins and stock turnovers that drive LEGO's business model.

Senior distribution manager Asger Juncher Métais said the group should assume that all retailers want quick lead times and fast stock turnover, capabilities where LEGO is strong. The company can provide Asian retailers with a stock turn of six, while competitors could only offer three. However, LEGO offers a 30-35 percent margin to retailers, compared to competing brands offering 40-50 percent margins. What if local retailers wanted the higher margins and could care less about turnover?

Outsourcing risks. With limited real estate in Asia, many local retailers operate with low inventory and depend on LEGO for just-in-time delivery. The company could build molding factories in Asia to shorten lead times and improve efficiency, but pushing down production costs is not a primary driver for LEGO, which enjoys high margins on its products. The company's main priority is quick response to retailer demand. Outsourcing is another possibility, but a previous partnership with Flextronics was a poor match—LEGO eventually moved most production back in-house. Another option, Mikes says, is "they can build local warehouses, packing and distribution centers. Initially, they don't have to make a big commitment to a huge factory, although if demand exceeds forecasts, they may have to."

Time For Decisions

Back in the classroom, after engaging in scenario planning, the students decided that LEGO should put more resources on the ground in China, commit to localization efforts, and continue to introduce products like Ninjago that have global appeal. When Mikes followed up with LEGO, she realized that the managers "were largely moving in the same direction."

Mikes emphasizes that it's critical to understand what scenario planning can and can't do. While scenario planning can't forecast the future, the outcomes from its exercises help managers assign task forces around the necessary actions implied by the scenarios and create early warning indicators that can highlight the emergence of one scenario or another, giving the company a head start on the competition.

"Where we come out on this is that there are situations where scenarios can be useful," Mikes says. "But to make this a truly useful exercise there has to be real business engagement and follow-up. There can't just be stargazing and blue-sky thinking."

The company's recent history, she adds, makes it particularly cautious today.

"LEGO was burned very badly in the past," Mikes says. "They are humble enough to be wary of becoming complacent, as many successful companies do."

- Kapil Kumar Sopory

- Company Secretary, SMEC(India) Private Limited

- President, R&R

- Rohit Desai

- SRILA RAMANUJAM

- 26 Apr 2024

Deion Sanders' Prime Lessons for Leading a Team to Victory

- 02 Apr 2024

- What Do You Think?

What's Enough to Make Us Happy?

- 11 Sep 2017

- Research & Ideas

Why Employers Favor Men

- 25 Jan 2022

More Proof That Money Can Buy Happiness (or a Life with Less Stress)

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- Innovation and Management

- Entertainment and Recreation

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Welcome to the MIT CISR website!

This site uses cookies. Review our Privacy Statement.

Transforming the LEGO Group for the Digital Economy

An in-depth description of a firm’s approach to an IT management issue (intended for MBA and executive education)

To avert bankruptcy, the LEGO Group had transformed itself starting in 2004. As it entered 2016, the company was poised for a new transformation. This time the transformation builds on the strength of an enterprise platform the company developed to provide needed discipline around core business processes. The goal of the new transformation is “to become a digital company.” Although the company already looked digital in 2016, management felt it had not become digital—in its products and processes. This case describes the LEGO Group’s journey to become a successful digital company.

Access More Research!

Any registered, logged-in user of the website can read many MIT CISR Working Papers in the webpage from 90 days after publication, plus download a PDF of the publication. Employees of MIT CISR members organizations get access to additional content.

About the Authors

Jeanne W. Ross, MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research (CISR)

Mit center for information systems research (cisr).

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

MIT CISR Associate Members

MIT CISR wishes to thank all of our associate members for their support and contributions.

MIT CISR's Mission Expand

MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We provide insights on how organizations effectively realize value from approaches such as digital business transformation, data monetization, business ecosystems, and the digital workplace. Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT’s tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, we work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How Lego clicked: the super brand that reinvented itself

The revival of Lego has been hailed as the greatest turnaround in corporate history, ousting Ferrari as the world’s most powerful brand. Johnny Davis reports

F rom its founding in 1932 until 1998, Lego had never posted a loss. By 2003 it was in big trouble. Sales were down 30% year-on-year and it was $800m in debt. An internal report revealed it hadn’t added anything of value to its portfolio for a decade.

Consultants hurried to Lego’s Danish HQ. They advised diversification. The brick had been around since the 1950s, they said, it was obsolete. Lego should look to Mattel, home to Fisher-Price, Barbie, Hot Wheels and Matchbox toys, a company whose portfolio was broad and varied. Lego took their advice: in doing so it almost went bust. It introduced jewellery for girls. There were Lego clothes. It opened theme parks that cost £125m to build and lost £25m in their first year. It built its own video games company from scratch, the largest installation of Silicon Graphics supercomputers in northern Europe , despite having no experience in the field. Lego’s toys still sold, particularly tie-ins, like their Star Wars and Harry Potter -themed kits. But only if there was a movie out that year. Otherwise they sat on shelves.

“We are on a burning platform,” Lego’s CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp told colleagues. “We’re running out of cash… [and] likely won’t survive”

In 2015, the still privately owned, family controlled Lego Group overtook Ferrari to become the world’s most powerful brand. It announced profits of £660m, making it the number one toy company in Europe and Asia, and number three in North America, where sales topped $1bn for the first time. From 2008 to 2010 its profits quadrupled, outstripping Apple’s. Indeed, it has been called the Apple of toys: a profit-generating, design-driven miracle built around premium, intuitive, covetable hardware that fans can’t get enough of. Last year Lego sold 75bn bricks. Lego people – “Minifigures” – the 4cm-tall yellow characters with dotty eyes, permanent grins, hooks for hands and pegs for legs – outnumber humans. The British Toy Retailers Association voted Lego the toy of the century.

When The Lego Movie came out in 2014 the film snob website Rotten Tomatoes awarded it a 96% approval rating: only Oscar nominees 12 Years a Slave and Gravity matched it. This year’s follow-up, The Lego Batman Movie , outperformed the last “proper” Batman movie, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice , to such a degree that DC Comics now faces a genuine problem: audiences overwhelmingly prefer the Dark Knight in his pompous and plastic version voiced by Will Arnett , rather than Ben Affleck ’s portrayal.

Lego’s revival has been called the greatest turnaround in corporate history. A book devoted to the subject, David Robertson’s Brick by Brick: How Lego Rewrote the Rules of Innovation , has become a set business text. Sony, Adidas and Boeing are said to refer to it. Google now uses Lego bricks to help its employees innovate.

Lego’s saviour is the aforementioned Vig Knudstorp – a father of four, perhaps not uncoincidentally – who arrived from management consultants McKinsey & Company in 2001 and was promoted to boss within three years, aged 36. “In some ways, I think he’s a better model for innovation than Steve Jobs,” Robertson has said.

Last month I flew to Billund, a small town in the Jutland peninsula where Lego was founded. The landscape was flat and grey, but as I drove from the airport a large primary coloured arm or head would occasionally appear though the pine trees: the Lego Group owns several buildings here and has decorated the landscape accordingly. I was immediately in a good mood.

“Billund was built to function, not to please,” explained Roar Trangbaek, Lego’s cheerful, bearded publicist. “There’s not a lot of fun here.” He meant there wasn’t a lot to do there – it’s hard to imagine the nightlife is up to much – but given that 120m Lego bricks are manufactured here every day, fun was very much the point of the place. As if to prove it, Trangbaek handed me his business card. It was a Minifigure of himself.

The following morning the Lego Group was due to announce its latest annual results. Today was an opportunity to meet some of its key employees, tour the factory and be among the first to step inside Lego House – a 130,000sq ft marvel that will open in September, and is expected to draw 250,000 visitors a year. It has been designed by Bjarke Ingels , the hottest name in architecture right now, whose commissions include Google’s HQ, the new World Trade Center and last year’s Serpentine Pavilion. Ingels certainly seems to have enjoyed himself: Lego House resembles 21 giant Lego bricks stacked into a 30m tower. Visitors can climb up to the rooftop garden and down the other side, pausing to take in attractions, restaurants, play zones and a gallery dedicated to fan-made Lego extravaganzas. Life-sized Lego sculptures had been placed around the interior – a cop, a firefighter – while real-life construction workers in hi-vis tabards beavered away around them, a surreal sight.

Lego had compensated for the disruption to the town’s shops by allowing them to exclusively sell Lego kits of the Lego House, the only place in the world they’ll be available. (For Lego’s numerous cult fans, this is a massive deal.)

Vig Knudstorp rescued Lego by methodically rebuilding it, brick by brick. He dumped things it had no expertise in – the Legoland parks are now owned by the British company Merlin Entertainments, for example. He slashed the inventory, halving the number of individual pieces Lego produces from 13,000 to 6,500. (Brick colours had somehow expanded from the original bright yellow, red and blue, sourced from Piet Mondrian , to more than 50.) He also encouraged interaction with Lego’s fans, something previously considered verboten. Far from killing off Lego, the internet has played a vital role in allowing fans to share their creations and promote events like Brickworld , adult Lego fan conventions. A year before James Surowiecki’s landmark book The Wisdom of Crowds was published, Lego launched its own crowdsourcing competition: originators of winning ideas get 1% of their product’s net sales, designs that so far include the Back to the Future DeLorean time machine, the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine and a set of female Nasa scientists.

“Lego has this incredible ability to engage with people and that has single-handedly enabled it to weather very, very difficult seas,” says Simon Cotterrell, from brand analytics firm Interbrand. “What’s made them successful over the past 10 years is their ability to create new entities, movies, TV shows, by partnering with brilliant people. They’ve said: ‘We might not make as much money if we outsource it, but the product will be better.’ That mentality is very Danish. It comes from saying: ‘We’re engineers. We know what we’re good at. Let’s stick to our knitting.’ That’s a very brave thing to do and it’s where a lot of companies go wrong. They don’t understand that sometimes it’s better to let go than to hang on.”

It also started making hit toys again. As well as putting a focus back on classic Lego lines like City and Space, it has launched the ninja-themed Ninjago line, Mindstorms, kits that allow you to build programmable Lego robots, aimed at teens. And for grown-up kids, Lego Architecture, replicas of the Guggenheim, Burj Khalifa and Robie House , that last one not for the feint-hearted or time-poor – it contains 2,276 bricks. Most impressively for a company with a customer base that in 2011 was 90% boys, it finally cracked the girls’ market. Lego Friends features a reconfigured “Mini-doll” and centres on five characters in the fictional Heartlake City. None of this has happened by chance. Lego is said to conduct the largest ethnographic study of children in the world.

“We call it ‘camping with consumers’,” says Anne Flemmert Jensen, senior director of its Global Insights group. “My team spends all our time travelling around the world, talking to kids and their families and participating in their daily lives.” This includes watching how kids play on their own and with friends, how siblings interact and why some toys remain perennial favourites while others are relegated to the toy box. Children are fickle – as the makers of forgotten “must-have” Christmas toys, like Pogs and Furby, will concede.

Ninjago was crowdsourced: its first iteration featured skeletons as enemies because tests proved they were the most popular baddies among six-year-old boys, globally. “Ninjas crystallised themselves because we were, like: ‘What’s the greatest hero entry point?’” says Cerim Manovi, senior design manager and creative lead on the line. “We showed them superheroes, everything – but ninjas just grabbed kids right there.”

Lego Friends took four years of research (plus a $40m global marketing push) to get right.

“One of the main things was they couldn’t really relate to the Minifigure,” says Mauricio Affonso, Friends’ model designer. “It’s too blocky. Boys tend to be a lot more about good versus evil, whereas girls really see themselves through the Mini-doll. They wanted a greater level of detail, proportions and realism.”

Lego Friends sets (bakery, amusement park, riding camp, etc) tend to feature something else missing from boys’ sets: a loo. The boys don’t care, the girls’ pragmatism demanded it.

Roar Trangbaek shows me the original Lego house, where the company’s founder Ole Kirk Christiansen lived. It’s now a private museum that tells the Lego chronology through artefacts, packaging and toys. More than one adult visitor has been known to burst into tears when confronted by a key line from their childhood: in my case the Space Lego of the mid-1970s. (Lego gets inundated with requests for re-releases, but they won’t do it. Their focus is the kids of now and tomorrow, not yesterday.) Christiansen was an expert carpenter when the Great Depression hit. He figured the one thing people would always find money for was toys for their children. His company motto is carved into a plaque here – “det bedste er ikke for godt” (Only the best is good enough) – something borne out when Christiansen’s son Godtfred returned home one day to proudly inform dad he’d saved them some cash by only applying two of the usual three coats of varnish to a wooden duck. He got a tongue- lashing for his trouble.

“It is a good story, but it’s also a true story,” says Trangbaek.

In 1946, against everyone’s advice, the family invested in a newfangled plastic-injection moulding machine. Later they adapted Croydon-based inventor Hilary Fisher Page’s self-locking bricks (billed his “sensible toy”) – plastic cubes with two rows of four studs to enable stacking. The final part of Lego’s success clicked into place in 1958 when it created its “system”. Where previously they’d made toys of all shapes and sizes now every brick fitted with every other: everything was backwards compatible. “We’ve got the bricks, you’ve got the ideas,” advised a 1992 Lego catalogue. A mathematician recently deduced that just six eight-stud bricks of the same colour could be combined 915,103,765 ways.

During the factory tour we saw some of those bricks being created. Here, 768 moulding machines work 24/7, 361 days of the year. There was a constant hiss: the sound of raw granulate being fed into the vast machines. Then something akin to Wonka magic, brightly coloured pieces of joy materialising at the other end. Lego’s quality control and precision is rigorous. As any parent who’s trodden on a piece knows, Lego is hard. The bricks have to be strong enough to hold together, but not so strong they can’t easily be pulled apart by a child. They call it “clutch power”. It is a huge industrial process, with similar plants in Hungary, China and Mexico. “Our idea is to have factories located close to key markets,” Trangbaek explained. Most companies make product where it’s cheapest then ship it. Not Lego. “It’s much more costly for us to lose a sale,” he said. “If you go to a toy store and you don’t find the product there on the shelf, you will be disappointed. But you will also not leave the shop without another toy.”

Lego is increasingly concentrating on bridging the physical and the virtual. This year it rolled out Lego Life, a social network for kids too young for Instagram to share their creations, gaining “likes” from peers and Lego characters alike. “Lego Batman can comment in character. ‘That’s awesome – would have been better in black and yellow,’” says Dieter Carstensen , head of digital child safety and the Lego Life team.“That kind of stuff.” There’s also Nexo Knights, a video game where powers are unlocked by scanning Lego pieces. They’re researching VR and AR. “Some of the things we’re looking at are very near to being feasible now,” says William Thorogood, an irrepressibly bouncy Brit, and the senior innovation director with Lego’s creative play lab. “Other things are very exciting, but probably not feasible for 10 years, depending on how mature the tech becomes.” Later this year we can look forward to The Lego Ninjago Movie , whose tone looks every bit as irreverently daft as its predecessors.

The next morning in Billund, Lego announced the highest revenues in its 85-year-history. Since December the company has been run by another Brit, Bali Padda, the first non-Dane in charge, after Vig Knudstorp moved into a new role to expand the brand globally. Asia, with its booming middle class, is a focus.

“The reality is that the last few years the growth has been supernatural,” Julia Goldin, Lego’s chief marketing officer, tells me. “When you look at the proportion of revenue that’s coming out of the mature markets it becomes more and more challenging with the level of penetration. But we look at every year starting at zero because you have to recruit every child again and make the brand exciting for them. That becomes a good challenge, of course.”

Earlier I had met Bo Stjerne Thomsen, the director of research and learning with the Lego Foundation, an independent body that owns 25% of the Lego Group and studies early childhood development through play. (It has partnered with Unicef in South Africa, and funded the world’s first professor of play , at Cambridge University)

Thomsen produced two plastic bags containing a few red and yellow bricks, part of a basic kit they use to engage learning.

“Quickly build a duck,” he instructed me. “Everybody can usually do it in 40 seconds.”

We set to work. Thomsen’s duck had two outstretched wings. Mine had a red bill, a red slab for feet and a yellow block for a tail.

“Oh, that’s fun!” he said. “I like that.”

There was no wrong or right duck, of course. That was the point. “It’s about the process of making and investigating and learning,” Thomsen said.

“How fast do you think anyone can do a duck?” Thomsen asked.

I’m not sure, I said. Ten seconds?

“Ten seconds? OK, let me count.”

Then he slammed another set of pieces straight down on to the table.

“That’s my duck!” he beamed. “I just sliced it up so it’s ready for the oven. Ha ha!”

Lego is a serious business. It just happens to be in the business of fun.

- The Observer

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- News & Ideas

- Work with us

Protecting children from the risks of online play across Asia Pacific

Children spend more time online than ever; they face risks never before imagined. The LEGO Group, the company behind the iconic LEGO ® bricks, has a strategic commitment to helping kids everywhere learn through play and wanted to contribute a solution to this challenge. Working with policymakers and regulators throughout Asia Pacific, the LEGO Group sought to understand and find policy solutions to help today’s children navigate the new digital landscape, while also progressing the company’s ambition to advocate for the well-being of children.

Categories & Services

As play is increasingly digital, children today face new and unprecedented risks. Hacking, invasion of privacy and child safety are the next frontier for safe parenting. Despite the dangers being widely recognized, discussions on the best policies and regulations to combat them were relatively nascent across Asia Pacific. The LEGO Group sought ways to engage the policy discussion to help create a safe and beneficial digital play experience for children.

The LEGO Group’s Government and Public Affairs team engaged APCO to better understand the regional environment and local nuances within four APAC markets. APCO investigated current market trends, regulations and stakeholders governing digital engagement with children, seeking to identify ways to impact policy to level the often-uneven ground between accessible technology and children’s safety. Our recommendations informed the LEGO Group’s approach to engage in policy discussions through innovative research that incorporates the voices of all key stakeholders, including children.

By looking at uncommon ways to address this challenge, APCO was able to structure the LEGO Group’s engagement with policymakers and regulators to enhance the overall understanding of the challenges and expectations of children and relevant stakeholders. This engagement not only helped drive the change needed to get the best out of technology, but also enhanced awareness of the company’s efforts at delivering beneficial digital play for children that considers their well-being.

The Singapore office for THE LEGO Group. Photo: LEGO

A model created by a participant during the creative LEGO play activity at the Children’s Digital Citizenship roundtable in Seoul, South Korea. Photo: APCO

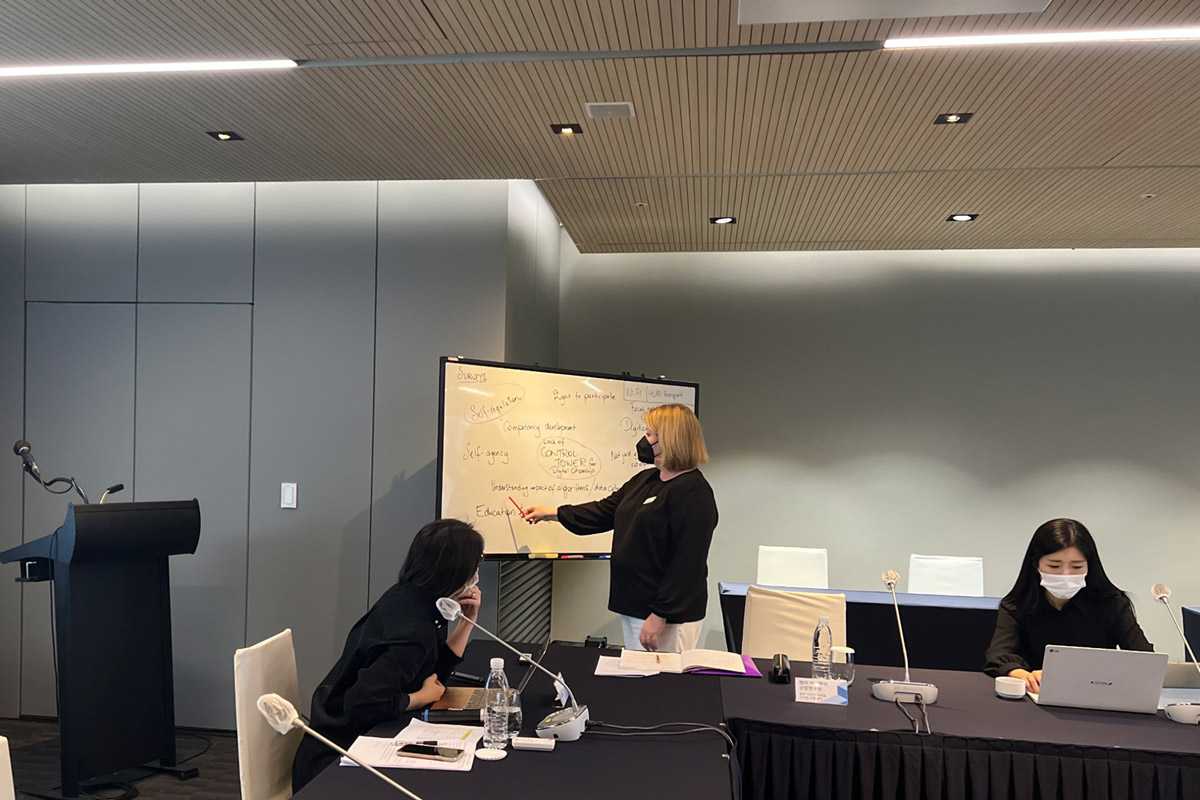

A cross-sectoral group of stakeholders convened in Seoul, South Korea for a roundtable to discuss children’s digital citizenship as a tool for addressing concerns about children’s digital safety. Photo: APCO

Dr. Emma Jayakumar, Lead Research Assistant, Edith Cowan University presents initial research findings on children’s digital citizenship and children’s online experiences at roundtable in Seoul, South Korea. Photo: APCO

SustainCase – Sustainability Magazine

- trending News

- Climate News

- Collections

- case studies

Case study: How the LEGO Group promotes integrity in its operations

As a family-owned, values-based company, with products sold in more than 140 countries around the globe and over 19,000 employees, the LEGO Group aims to have a positive impact on children, society and the planet, not least by operating according to the highest ethical standards.

This case study is based on the 2016 Responsibility Report b y the LEGO Group published on the Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Disclosure Database that can be found at this link . Through all case studies we aim to demonstrate what CSR/ sustainability reporting done responsibly means. Essentially, it means: a) identifying a company’s most important impacts on the environment, economy and society, and b) measuring, managing and changing.

With 131 LEGO Brand Retail Stores and sales offices in 37 countries, the LEGO Group is the world’s largest toy company. Operating ethically is, thus, a top priority. In order to promote integrity in its operations the LEGO Group took action to:

- promote compliance through the Corporate Compliance Board

- provide ethics training

- enhance third party due diligence

Subscribe for free and read the rest of this case study

Please subscribe to the SustainCase Newsletter to keep up to date with the latest sustainability news and gain access to over 100 case studies. These case studies demonstrate how companies are dealing responsibly with their most important impacts, building trust with their stakeholders (Identify > Measure > Manage > Change).

With this case study you will see:

- Which are the most important impacts (material issues) the LEGO Group has identified;

- How the LEGO Group proceeded with stakeholder engagement , and

- What actions were taken by the LEGO Group to promote integrity in its operations

Already Subscribed? Type your email below and click submit

What are the material issues the company has identified?

In its 2016 Responsibility Report the LEGO Group identified a range of material issues, such as product safety, climate change, waste, employee safety, the play and learning experience children get from products. Among these, promoting integrity in its operations stands out as a key material issue for the LEGO Group.

Stakeholder engagement in accordance with the GRI Standards

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) defines the Principle of Stakeholder Inclusiveness when identifying material issues (or a company’s most important impacts) as follows:

“The organization should identify its stakeholders, and explain how it has responded to their reasonable expectations.”

Stakeholders must be consulted in the process s of identifying a company’s most important impacts and their reasonable expectations and interests must be taken into account. This is an important cornerstone for CSR / sustainability reporting done responsibly.

Key stakeholder groups the LEGO Group engages with:

How stakeholder engagement was made to identify material issues

To identify and prioritize material issues, the LEGO Group engaged with a wide range of stakeholders. They included consumers, customers, employees, NGOs, interest groups and industry associations. To achieve engagement, the LEGO Group conducted an online survey among over 1,500 respondents. Moreover, it carried out interviews with 1,500 additional participants, to identify stakeholders’ top priorities.

What actions were taken by the LEGO Group to promote integrity in its operations?

In its 2016 Responsibility Report the LEGO Group reports that it took the following actions to promote integrity in its operations:

- Promoting compliance through the Corporate Compliance Board

- The Corporate Compliance Board (CCB) is the highest decision authority regarding non-compliance issues in the LEGO Group. The CCB promotes the proper handling of ethical issues and compliance with external regulations. The CCB is also responsible for providing relevant operational guidance and reviewing policies. In 2016, the CCB reviewed the updated Responsible Marketing to Children Policy and the Digital Child Safety Policy.

- Providing ethics training

- [tweetthis] All LEGO employees participate in mandatory training on the importance of operating ethically. [/tweetthis] More specifically, the LEGO Group offers training on the LEGO Code of Ethical Business Conduct and Corruption Awareness and Competition Law e-learning programmes. Moreover, the LEGO Group reached the target of training 100% of senior business leaders bi-annually on the LEGO Code of Ethical Business Conduct. Additionally, more than 98% of salaried employees have received bi-annual training on ethical business conduct and anti-corruption principles.

- Enhancing third party due diligence

- The LEGO Group carries out integrity due diligence screenings of third parties and continually improves its third party due diligence process. The LEGO Group addresses risks holistically, including issues concerning anti-bribery and corruption, social responsibility, human rights and environmental sustainability.

Which GRI indicators/Standards have been addressed?

The GRI indicator addressed in this case is: G4-SO4: Communication and training on anti-corruption policies and procedures and the updated GRI Standard is: Disclosure 205-2 Communication and training about anti-corruption policies and procedures

78% of the world’s 250 largest companies report in accordance with the GRI Standards

SustainCase was primarily created to demonstrate, through case studies, the importance of dealing with a company’s most important impacts in a structured way, with use of the GRI Standards. To show how today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social and environmental success – and how you can too.

Research by well-recognised institutions is clearly proving that responsible companies can look to the future with optimism .

7 GRI sustainability disclosures get you started

Any size business can start taking sustainability action

GRI, IEMA, CPD Certified Sustainability courses (2-5 days): Live Online or Classroom (venue: London School of Economics)

- Exclusive FBRH template to begin reporting from day one

- Identify your most important impacts on the Environment, Economy and People

- Formulate in group exercises your plan for action. Begin taking solid, focused, all-round sustainability action ASAP.

- Benchmarking methodology to set you on a path of continuous improvement

See upcoming training dates.

References:

1) This case study is based on published information by the LEGO Group, located at the link below. For the sake of readability, we did not use brackets or ellipses. However, we made sure that the extra or missing words did not change the report’s meaning. If you would like to quote these written sources from the original, please revert to the original on the Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Disclosure Database at the link:

http://database.globalreporting.org/

2) http://www.fbrh.co.uk/en/global-reporting-initiative-gri-g4-guidelines-download-page

3) https://g4.globalreporting.org/Pages/default.aspx

4) https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/

Note to the LEGO Group: With each case study we send out an email requesting a comment on this case study. If you have not received such an email please contact us .

Privacy Overview

Brought to you by:

THE LEGO GROUP LEADERSHIP PLAYGROUND: ENERGIZING EVERYBODY EVERY DAY (A)

By: John Weeks, Lisa Duke

In 2018, the LEGO Group defined a new way of leading to enable the company to move more quickly, to make the right decisions, to deliver its mission and the commercial momentum that sustained it, and…

- Length: 19 page(s)

- Publication Date: Feb 7, 2021

- Discipline: Human Resource Management

- Product #: IM1113-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

In 2018, the LEGO Group defined a new way of leading to enable the company to move more quickly, to make the right decisions, to deliver its mission and the commercial momentum that sustained it, and to shape the LEGO® culture in a positive way. This new way of leading would need to be modeled at the top of the organization. That was certain. But CEO, Niels Christiansen, and Chief People Officer, Loren Shuster, believed that the task of defining the new way of leading should not be done by the Executive Leadership Team or by HR. It should be developed bottom up. The LEGO Group was no longer the patriarchy it had once been under its founder, but Shuster saw that patriarchal assumptions about leadership lingered in its culture. If the LEGO Group was going to move towards a balanced system where leadership responsibility was more distributed and less hierarchical, it would be ironic to impose this top down. A better way to start would be to invite people from different levels and different functions of the organization to answer the question: What kind of leadership do we need in the LEGO Group and how can we embed the new way of leading into the fabric of the organization so that it can be self-generative? Case A describes the process that the LEGO Group used to create what they called The Leadership Playground and bring it to life in the company.

Learning Objectives

How to create a leadership model to change the culture of the LEGO Group in a bottom-up way.

Feb 7, 2021

Discipline:

Human Resource Management

Industries:

Retail and consumer goods, Video game industry

IM1113-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

The LEGO Group – a Case Study In Strategic Risk Management

Using monte carlo simulations to help the board of directors establish risk appetite.

- 2.9 • 8 Ratings

Publisher Description

This book explains how The LEGO Group is using sophisticated methods to quantify specific risks such as project and credit risks, as well as to consolidate its risk portfolio at the highest level.

More Books Like This

More books by ghislain giroux dufort, customers also bought.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

When a benchmarking study revealed LEGO's global name recognition was on par with industry giants like Disney, the team started churning out new products and ideas to leverage the brand's untapped value. A line of LEGO-branded children's wear was created and a division of the LEGO Group was charged with pitching book, movie, and TV ideas.

The Lego Group is a toy-manufacturing company which is based in Billund, Denmark. The company was founded as a family organization in the year 1932, by Ole Kirk Christian. Today, the company stands high as a global player in the world of toys, among other strategic entertainment products (LeGoff 557). Initially, Lego started as a manufacturer ...

Five years ago, the LEGO Group was near bankruptcy. Many of its innovation efforts—theme parks, Clikits craft sets (marketed to girls), an action figure called Galidor supported by a television ...

the smart toy industry is expected to grow at a compound annual rate of 15.5% from 2017 to. 2025 (Business Insider, 2019). Linking Strategy to Innovation: The LEGO Case. This case study focuses on ...

This case describes the LEGO Group's journey to become a successful digital company. Keywords: Enterprise platform, engagement platform ... This case study was prepared by Peter Andersen of Aarhus University and Jeanne W. Ross of the MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research (CISR). This case was written for the purposes of class ...

In 2018, the LEGO Group defined a new way of leading to enable the company to move more quickly, to make the right decisions, to deliver its mission and the commercial momentum that sustained it, and to shape the LEGO® culture in a positive way. This new way of leading would need to be modeled at the top of the organization. That was certain ...

The case tells the story of a company where innovation is tremendously important, but not working well. In 2003, the LEGO Group had a number of positive attributes: it had a well-respected brand with some very good toy lines. It had a passionate customer base that in many areas was more sophisticated than its internal designers.

Abstract. LEGO has emerged as one of the most successful companies in the toy industry. The case describes LEGO's gradual rise, rapid decline, and recent revitalization as it is keeping up with a changing market place. Central to LEGO's management model is the ability to find the right balance among growing through innovation, staying true to ...

The case study The LEGO Group: Envisioning Risks in Asia, coauthored with HBS research associate Dominique Hamel, vividly details sitting in on the toy maker's scenario-planning meeting, where top execs tested whether the current business model was robust enough for the challenges lying ahead. While LEGO has sold toys in Asia for three decades ...

To avert bankruptcy, the LEGO Group had transformed itself starting in 2004. As it entered 2016, the company was poised for a new transformation. This time the transformation builds on the strength of an enterprise platform the company developed to provide needed discipline around core business processes. The goal of the new transformation is "to become a digital company." Although the ...

Home Research & Knowledge Strategy The LEGO group: Family business resilience (A) The family-owned and family-run global toy firm LEGO had spent around a decade reinventing itself, launching new products, committing to continual innovation, employing top designers. It switched from a hierarchical structure to teams. It introduced robotics and ...

The revival of Lego has been hailed as the greatest turnaround in corporate history, ousting Ferrari as the world's most powerful brand. Johnny Davis reports. F rom its founding in 1932 until ...

The Lego case study serves as a powerful reminder that even the most iconic and successful brands must be willing to evolve and adapt to the ever-changing market landscape. ... The Lego Group's ...

Feb 10, 2024. The LEGO Group was founded in 1932 by Ole Kirk Christiansen in Billund, Denmark. What started as a small carpentry workshop soon transitioned to manufacturing wooden toys as ...

Throughout the last 20 years the LEGO Group has nurtured and developed an eco-system of alliances with different partners in different industries. Ever since the late nineties digital game play has been growing exponentially, kids spend much more time on screens and the LEGO Group has to follow this trend by adapting its partnership strategy and approach. This complex set of interdependencies ...

The LEGO Group, the company behind the iconic LEGO ® bricks, has a strategic commitment to helping kids everywhere learn through play and wanted to contribute a solution to this challenge. Working with policymakers and regulators throughout Asia Pacific, the LEGO Group sought to understand and find policy solutions to help today's children ...

This case study is based on the 2016 Responsibility Report by the LEGO Group published on the Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Disclosure Database that can be found at this link. Through all case studies we aim to demonstrate what CSR/ sustainability reporting done responsibly means.

In 2018, the LEGO Group defined a new way of leading to enable the company to move more quickly, to make the right decisions, to deliver its mission and the commercial momentum that sustained it, and to shape the LEGO® culture in a positive way. This new way of leading would need to be modeled at the top of the organization. That was certain. But CEO, Niels Christiansen, and Chief People ...

History and Context. In 2022, the Lego Group turned 90 years old. Founded in Denmark in 1932, by the 1990s someone would be hard-pressed to find a child's toy closet that didn't have any Legos ...

With revenues increasing from $1 billion to $8.4 billion, the company has managed to achieve an 8x increase. Moreover, our LEGO case study shows they have achieved a profit margin of nearly 25% and a profit of $2 billion indicate exceptionally strong performance. To illustrate, click on the financial performance metrics of our LEGO case study.

Case Study #6: Lego Group: An Outsourcing Journey. Robert Kolowitz. May 1, 2019. University of San Francisco. MSIS-675-35. Professor W illiam Kolb. CASE STUDY #6 2. Executive Summary:

Learning & Development Case Study. The LEGO Group. June 9th, 2021. Overview: The globally renowned Lego Group is one of the world's leading manufacturers of toys and play materials. A family-owned business with a mission: to develop the builders of tomorrow. This mission requires constant innovation and effective change management to maintain ...

This book explains how The LEGO Group is using sophisticated methods to quantify specific risks such as project and credit risks, as well as to consolidate its risk portfolio at the highest level. ... The LEGO Group - a Case Study In Strategic Risk Management Using Monte Carlo Simulations to Help the Board of Directors Establish Risk Appetite.