5 Powerful Essays Advocating for Gender Equality

Gender equality – which becomes reality when all genders are treated fairly and allowed equal opportunities – is a complicated human rights issue for every country in the world. Recent statistics are sobering. According to the World Economic Forum, it will take 108 years to achieve gender parity . The biggest gaps are found in political empowerment and economics. Also, there are currently just six countries that give women and men equal legal work rights. Generally, women are only given ¾ of the rights given to men. To learn more about how gender equality is measured, how it affects both women and men, and what can be done, here are five essays making a fair point.

Take a free course on Gender Equality offered by top universities!

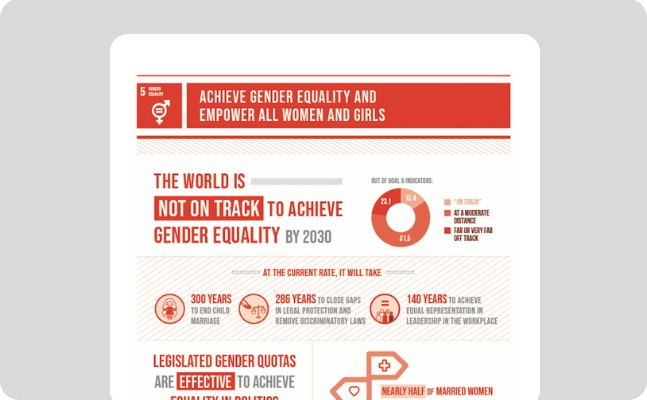

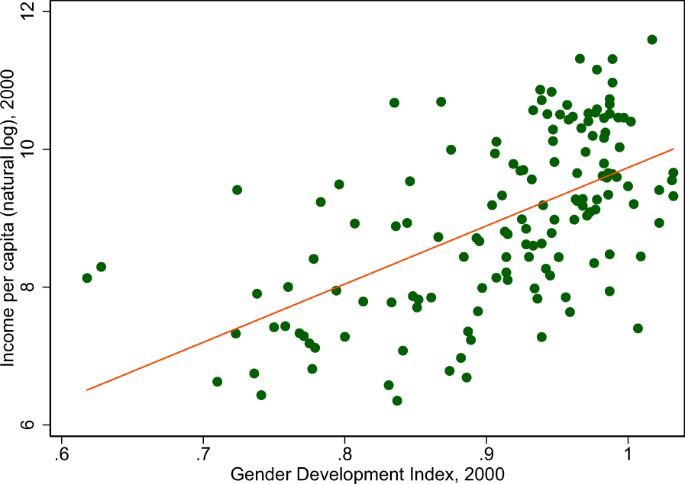

“Countries With Less Gender Equity Have More Women In STEM — Huh?” – Adam Mastroianni and Dakota McCoy

This essay from two Harvard PhD candidates (Mastroianni in psychology and McCoy in biology) takes a closer look at a recent study that showed that in countries with lower gender equity, more women are in STEM. The study’s researchers suggested that this is because women are actually especially interested in STEM fields, and because they are given more choice in Western countries, they go with different careers. Mastroianni and McCoy disagree.

They argue the research actually shows that cultural attitudes and discrimination are impacting women’s interests, and that bias and discrimination is present even in countries with better gender equality. The problem may lie in the Gender Gap Index (GGI), which tracks factors like wage disparity and government representation. To learn why there’s more women in STEM from countries with less gender equality, a more nuanced and complex approach is needed.

“Men’s health is better, too, in countries with more gender equality” – Liz Plank

When it comes to discussions about gender equality, it isn’t uncommon for someone in the room to say, “What about the men?” Achieving gender equality has been difficult because of the underlying belief that giving women more rights and freedom somehow takes rights away from men. The reality, however, is that gender equality is good for everyone. In Liz Plank’s essay, which is an adaption from her book For the Love of Men: A Vision for Mindful Masculinity, she explores how in Iceland, the #1 ranked country for gender equality, men live longer. Plank lays out the research for why this is, revealing that men who hold “traditional” ideas about masculinity are more likely to die by suicide and suffer worse health. Anxiety about being the only financial provider plays a big role in this, so in countries where women are allowed education and equal earning power, men don’t shoulder the burden alone.

Liz Plank is an author and award-winning journalist with Vox, where she works as a senior producer and political correspondent. In 2015, Forbes named her one of their “30 Under 30” in the Media category. She’s focused on feminist issues throughout her career.

“China’s #MeToo Moment” – Jiayang Fan

Some of the most visible examples of gender inequality and discrimination comes from “Me Too” stories. Women are coming forward in huge numbers relating how they’ve been harassed and abused by men who have power over them. Most of the time, established systems protect these men from accountability. In this article from Jiayang Fan, a New Yorker staff writer, we get a look at what’s happening in China.

The essay opens with a story from a PhD student inspired by the United States’ Me Too movement to open up about her experience with an academic adviser. Her story led to more accusations against the adviser, and he was eventually dismissed. This is a rare victory, because as Fan says, China employs a more rigid system of patriarchy and hierarchy. There aren’t clear definitions or laws surrounding sexual harassment. Activists are charting unfamiliar territory, which this essay explores.

“Men built this system. No wonder gender equality remains as far off as ever.” – Ellie Mae O’Hagan

Freelance journalist Ellie Mae O’Hagan (whose book The New Normal is scheduled for a May 2020 release) is discouraged that gender equality is so many years away. She argues that it’s because the global system of power at its core is broken. Even when women are in power, which is proportionally rare on a global scale, they deal with a system built by the patriarchy. O’Hagan’s essay lays out ideas for how to fix what’s fundamentally flawed, so gender equality can become a reality.

Ideas include investing in welfare; reducing gender-based violence (which is mostly men committing violence against women); and strengthening trade unions and improving work conditions. With a system that’s not designed to put women down, the world can finally achieve gender equality.

“Invisibility of Race in Gender Pay Gap Discussions” – Bonnie Chu

The gender pay gap has been a pressing issue for many years in the United States, but most discussions miss the factor of race. In this concise essay, Senior Contributor Bonnie Chu examines the reality, writing that within the gender pay gap, there’s other gaps when it comes to black, Native American, and Latina women. Asian-American women, on the other hand, are paid 85 cents for every dollar. This data is extremely important and should be present in discussions about the gender pay gap. It reminds us that when it comes to gender equality, there’s other factors at play, like racism.

Bonnie Chu is a gender equality advocate and a Forbes 30 Under 30 social entrepreneur. She’s the founder and CEO of Lensational, which empowers women through photography, and the Managing Director of The Social Investment Consultancy.

You may also like

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

Top 20 Issues Women Are Facing Today

Top 20 Issues Children Are Facing Today

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

Closing the equity gap

Jeni Klugman

Caren Grown and Odera Onyechi

Why addressing gender inequality is central to tackling today’s polycrises

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative, Global Economy and Development, Brookings Institution

As we enter 2023, the term “ polycrisis ” is an increasingly apt way to describe today’s challenges. 1 Major wars, high inflation, and climate events are creating hardship all around the world, which is still grappling with a pandemic death toll approaching 7 million people.

Faced with such daunting challenges, one might well ask why we should be thinking about the gender dimensions of recovery and resilience for future shocks. The answer is simple: We can no longer afford to think in silos. Today’s interlocking challenges demand that sharp inequalities, including gender disparities, must be addressed as part and parcel of efforts to tackle Africa’s pressing issues and ensure the continent’s future success.

“We can no longer afford to think in silos. … Gender disparities, must be addressed as part and parcel of efforts to tackle Africa’s pressing issues and ensure the continent’s future success.”

The burdens of the pandemic have been unequally borne across regions and countries, and between the poor and better off. Inequalities exist around gender—which can be defined as the “socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities, attributes and opportunities that any society considers appropriate for men and women, boys and girls” and people with non-binary identities. 2 As Raewyn Connell laid out more than two decades ago, existing systems typically distribute greater power, resources, and status to men and behaviors considered masculine . 3 As a result, gender intersects with other sources of disadvantage, most notably income, age, race, and ethnicity.

This understanding is now mainstream. As recently observed by the IMF, “The gender inequalities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic follow different paths but almost always end up the same: Women have suffered disproportionate economic harm from the crisis.” 4 Among the important nuances revealed by micro-surveys is that rural women working informally continued to work through the pandemic , but with sharply reduced earnings in Nigeria and elsewhere. 5 And as the burden of child care and home schooling soared, rural households headed by women were far less likely than urban households to have children engaged in learning activities during school closures.

Important insights emerge from IFPRI’s longitudinal panel study (which included Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda) covering income loss, coping strategies, labor and time use, food and water insecurity, and child education outcomes. 6

Among the especially adverse impacts for women were greater food and water insecurity compared to men, including worrying about insufficient food and eating less than usual, while a large proportion of women also did not have adequately diverse diets. Moreover, many women had to add hours to their workday caring for sick family members, and their economic opportunities shrank, cutting their earnings and widening gender income gaps.

While today’s problems seem daunting, there remain huge causes for optimism, especially in Africa. Over the past three decades, many African countries have achieved enormous gains in levels of education, health, and poverty reduction. Indeed, the pace of change has been staggering and commendable. As captured in the Women Peace and Security Index , which measures performance in inclusion, justice, and security, 6 of the top 10 score improvers during the period 2017-2021 were in sub-Saharan Africa. [GIWPS.2022. “Women Peace and Security Index” Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security.] The Democratic Republic of Congo was among top score improvers since 2017, as the share of women with financial accounts almost tripled, to 24 percent; and increases exceeding 5 percentage points were registered in cell phone use and parliamentary representation. In the Central African Republic, improvements were experienced in the security dimension, where organized violence fell significantly, and women’s perceptions of community safety rose 6 percentage points up to 49 percent.

Looking ahead, efforts to mitigate gender inequalities must clearly be multi-pronged, and as highlighted above—we need to think outside silos. That said, two major policy fronts emerge to the fore.

Ensure cash transfers that protect against poverty , are built and designed to promote women’s opportunities, with a focus on digital payments. 7 Ways to address gender inequalities as part of social protection program responses 8 include deliberate efforts to overcome gender gaps in cell phone access by distributing phones to those women who need them, as well as private sector partnerships to subsidize airtime for the poorest, and to make key information services and apps freely available . 9 Programs could also make women the default recipient of cash transfer schemes, instead of the head of household. Furthermore, capacity-building initiatives can be built into program design to give women the skills and capabilities needed to successfully manage accounts and financial decisionmaking. 10

Reducing the risk of violence against women. Women who are not safe at home are denied the freedom from violence needed to pursue opportunities that should be afforded to all. In 2018, 10 of the 15 countries with the worst rates of intimate partner violence were in sub-Saharan Africa—in descending order of average intimate partner violence these were, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Zambia, Ethiopia, Liberia, South Sudan, Djibouti, and Uganda.

“As the burden of child care and home schooling soared, rural households headed by women were far less likely than urban households to have children engaged in learning activities.”

Conflicts and crises multiply women’s risk of physical, emotional, and sexual violence . During the pandemic, risk factors like economic stress were compounded by service closures and stay-at-home orders, which increased exposure to potential perpetrators. 11 Several governments responded by strengthening existing help services , including police and justice, supporting hotlines, ensuring the provision of psychological support, and health sector responses. 12 Examples of good practice included an NGO in North-Eastern Nigeria, which equipped existing safe spaces with phone booths to enable survivors to contact caseworkers.

However, given the high levels of prevalence and often low levels of reporting, prevention of gender-based violence is key. Targeted programs with promising results in prevention include community dialogues and efforts to change harmful norms, safe spaces, as well as possibilities to reduce the risk of violence through cash plus social protection programs. These efforts should be accompanied by more systematic monitoring and evaluation to build evidence about what works in diverse settings.

Finally, but certainly not least, women should have space and voices in decisionmaking. This case was powerfully put by former President Sirleaf Johnson in her 2021 Foresight essay, which underlined that “ economic, political, institutional, and social barriers persist throughout the continent, limiting women’s abilities to reach high-level leadership positions .” 13 Persistent gender gaps in power and decision-making, not only limits innovative thinking and solutions, but also the consideration of more basic measures to avoid the worsening of gender inequalities. Overcoming these gaps in power and decision-making requires safeguarding legal protections and rights, investing in women and girls financially, and opening space for women in political parties so that women have the platforms to access high-level appointed and competitive positions across national, regional, and international institutions. 14

Strengthening fiscal policy for gender equality

Senior Fellow, Center for Sustainable Development, Global Economy and Development, Brookings Institution

Research Analyst, Center for Sustainable Development, Global Economy and Development, Brookings Institution

It is often said that women act as “shock absorbers” during times of crisis; this is even more so in the current context of climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and increased geopolitical conflict. These three global crises have simultaneously stretched women’s ability to earn income and intensified their unpaid work. Well-designed fiscal policy can help cushion the effects of these shocks and enable women and their households to recover more quickly.

Over 60 percent of employed women in Africa work in agriculture, including in small-scale food production; women are the primary sellers in food markets, and they work in other sectors such as informal trading. At the same time, women are an increasing share of entrepreneurs in countries such as Ghana and Uganda, even as they face financial and other constraints to start and grow their firms. [Africa Gender Innovation Lab (GIL). 2020. “Supporting Women Throughout the Coronavirus Emergency Response and Economic Recovery.” World Bank Group. ] In addition to earning income for their households, women bear the major responsibility for unpaid domestic activities such as cooking; collecting water and fuelwood; caring for children, elderly, and other dependents—so women are more time-poor than are men.

African women and entrepreneurs have been impacted disproportionately more than men by the triple shocks mentioned earlier. Extreme weather events disrupt food production and agricultural employment, making it harder for women to earn income . 15 16 17 The pandemic and conflict in Ukraine further intensified women’s paid and unpaid activities . 18 19 Beyond climate change and the war in Ukraine, localized conflicts and insecurity in East and West Africa exposes women and girls to gender-based violence and other risks as they seek to support their families and develop new coping strategies. 20 21 22

“Responding to these shocks necessitates a large infusion of resources. In this context, fiscal policy can be deployed more smartly to advance gender equality and create an enabling environment for women to play a greater role in building their economies’ recovery and resilience.”

Responding to these shocks necessitates a large infusion of resources. In this context, fiscal policy can be deployed more smartly to advance gender equality and create an enabling environment for women to play a greater role in building their economies’ recovery and resilience. Public expenditure supports critical sectors such as education, health, agriculture, social protection, and physical and social infrastructure, while well-designed tax policy is essential to fund the public goods, services, and infrastructure on which both women and men rely.

Gender-responsive budgets, which exist in over 30 countries across the continent, can be strengthened. Rwanda provides a good model for other countries. After an early unsuccessful attempt, Rwanda invested seriously in gender budgeting beginning in 2011. 23 24 The budget is focused on closing gaps and strengthening women’s roles in key sectors—agriculture, education, health, and infrastructure—which are all critical for short- and medium-term economic growth and productivity. The process has been sustained by strong political will among parliamentarians. Led by the Ministry of Finance, the process has financed and been complemented by important institutional and policy reforms. A constitutional regulatory body monitors results, with additional accountability by civil society organizations.

However, raising adequate fiscal revenue to support a gender budget is a challenge in the current macro environment of high public debt levels, increased borrowing costs, and low levels of public savings. Yet, observers note there is scope to increase revenues through taxation reforms, debt relief, cutting wasteful public expenditure, and other means. 25 26 We focus here on taxation.

Many countries are reforming their tax systems to strengthen revenue collection. Overall tax collection is currently low; the average tax-to-GDP ratio in Africa in 2020 was 14.8 percent and fell sharply during the pandemic, although it may be rebounding. 27 Very few Africans pay personal income tax or other central government taxes, 28 29 and statutory corporate tax rates (which range from 25-35 percent), are higher than even the recent OECD proposal for a global minimum tax 30 so scope for raising them further is limited. Efforts should be made to close loopholes and reduce tax evasion.

As countries reform their tax policies, they should be intentional about avoiding implicit and explicit gender biases. 31 32 33 34 Most African countries rely more on indirect taxes than direct taxes, given the structure of their economies, but indirect taxes can be regressive as their incidence falls primarily on the poor. Presumptive or turnover taxes, for example, which are uniform or fixed amounts of tax based on the “presumed” incomes of different occupations such as hairdressers, can hit women particularly hard, since the burden often falls heavily on sectors where women predominate. 35 36

Property taxes are also becoming an increasingly popular way to raise revenue for local governments. The impact of these efforts on male and female property owners has not been systematically evaluated, but a recent study of land use fees and agricultural income taxes in Ethiopia finds that female-headed and female adult-only households bear a larger tax burden than male-headed and dual-adult households of property taxes. This is likely a result of unequal land ownership patterns, gender norms restricting women’s engagement in agriculture, and the gender gap in agricultural productivity. 37

“Indirect taxes can be regressive as their incidence falls primarily on the poor. Presumptive or turnover taxes … can hit women particularly hard, since the burden often falls heavily on sectors where women predominate.”

Going forward, two key ingredients for gender budgeting on the continent need to be strengthened. The first is having sufficient, regularly collected, sex-disaggregated administrative data related to households, the labor force, and other survey data. Investment in the robust technical capacity for ministries and academia to be able to access, analyze, and use it is also necessary. For instance, the World Bank, UN Women, and the Economic Commission for Africa are all working with National Statistical Offices across the continent to strengthen statistical capacity in the areas of asset ownership and control, work and employment, and entrepreneurship which can be used in a gender budget.

The second ingredient is stronger diagnostic tools. One promising new tool, pioneered by Tulane University, is the Commitment to Equity methodology, designed to assess the impact of taxes and transfers on income inequality and poverty within countries. 38 It was recently extended to examine the impact of government transfers and taxes on women and men by income level and other dimensions. The methodology requires standard household-level data but for maximum effect should be supplemented with time use data, which are becoming more common in several African countries. As African countries seek to expand revenue from direct taxes, lessons from higher income economies are instructive. Although there is no one size fits all approach, key principles to keep in mind for designing personal income taxes include building in strong progressivity, taxing individuals as opposed to families, ensuring that the allocation of shared income (e.g., property or non-labor income) does not penalize women, and building in allowances for care of children and dependents. 39 As noted, corporate income taxes need to eliminate the many breaks, loopholes, and exemptions that currently exist, 40 and countries might consider experimenting with wealth taxes.

In terms of indirect taxes, most African countries do not have single-rate VAT systems and already have zero or reduced rates for basic necessities, including foodstuffs and other necessities. While it is important to minimize exempted sectors and products, estimates show that goods essential for women’s and children’s health (e.g., menstrual health products, diapers, cooking fuel) should be considered part of the basket of basic goods that have reduced or zero rates. 41 And while African governments are being advised to bring informal workers and entrepreneurs into the formal tax system, 42 it should be noted that this massive sector earns well below income tax thresholds and already pays multiple informal fees and levies, for instance in fees to market associations. 43 44

Lastly, leveraging data and digital technologies to improve tax administration (i.e., taxpayer registration, e-filing, and e-payment of taxes) may help minimize costs and processing time, and reduce the incidence of corruption and evasion.32 Digitalization can also be important for bringing more female taxpayers into the net, especially if digital systems are interoperable; for instance, digital taxpayer registries linked to national identification or to property registration at the local level. However, digitalization can be a double-edged sword if privacy and security concerns are not built-in from the outset. Women particularly may need targeted digital financial literacy and other measures to ensure their trust in the system. Recent shocks have worsened gender inequality in Africa. It is therefore important now, more than ever, to invest in strengthening fiscal systems to help women and men recover, withstand future shocks, and reduce gender inequalities. While fiscal policy is not the only tool, it is an important part of government action. To be effective and improve both budgeting and revenue collection, more and better data, new diagnostic tools, and digitalization will all be necessary.

- 1. Martin Wolf. 2022.“How to think about policy in a policy crisis”. Financial Times.

- 2. WTO. 2022. “Gender and Health”. World Health Organization.

- 3. Connell RW. 1995. “Masculinities”. Cambridge, UK. Polity Press.

- 4. Aoyagi, Chie.2021.“Africa’s Unequal Pandemic”. Finance and Development. International Monetary Fund.

- 5. WB.2022. “LSMS-Supported High-Frequency Phone Surveys”. World Bank.

- 6. Muzna Alvi, Shweta Gupta, Prapti Barooah, Claudia Ringler, Elizabeth Bryan and Ruth Meinzen-Dick.2022.“Gendered Impacts of COVID-19: Insights from 7 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia”. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- 7. Klugman, Jeni, Zimmerman, Jamie M., Maria A. May, and Elizabeth Kellison. 2020. “Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of COVID 19: Opportunities and Considerations for Women’s Inclusion and Empowerment”. World Bank Group.

- 8. IFPRI.2020. “Why gender-sensitive social protection is critical to the COVID-19 response in low-and middle-income countries”. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- 9. IDFR.2020. “Kenya: Mobile-money as a public-health tool”. International Day of Family Remittances.

- 10. Jaclyn Berfond Franz Gómez S. Juan Navarrete Ryan Newton Ana Pantelic. 2019. “Capacity Building for Government-to-Person Payments A Path to Women’s Economic Empowerment”. Women’s World Banking.

- 11. Peterman, A. et al.2020. “Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children”.Center for Global Development Working Paper.

- 12. UNDP/ UN Women Tracker.2022. “United Nations Development Programme. COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker”. United Nations Development Programme. New York.

- 13. McKinsey Global Institute .2019. “The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Africa”.

- 14. Foresight Africa. 2022. “African Women and Girls: Leading a continent.” The Brookings Institution.

- 15. One recent study in West, Central Africa, East and Southern Africa found that women represented a larger share of agricultural employment in areas affected by heat waves and droughts, and a lower share in areas unaffected by extreme weather events. Nico, G. et al. 2022. “How Weather Variability and Extreme Shocks Affect Women’s Participation in African Agriculture.” Gender, Climate Change, and Nutrition Integration Initiative Policy Note 14.

- 16. Carleton, E. 2022. “Climate Change in Africa: What Will It Mean for Agriculture and Food Security?” International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

- 17. Nebie, E.K. et al. 2021. “Food Security and Climate Shocks in Senegal: Who and Where Are the Most Vulnerable Households?” Global Food Security, 29.

- 18. Sen, A.K. 2022. “Russia’s War in Ukraine Is Taking a Toll on Africa.” United States Institute of Peace.

- 19. Thomas, A. 2020. “Power Structures over Gender Make Women More Vulnerable to Climate Change.” Climate Change News.

- 21. Kalbarczyk, A. et al. 2022. “COVID-19, Nutrition, and Gender: An Evidence-Informed Approach to Gender Responsive Policies and Programs.” Social Science & Medicine, 312.

- 22. Epstein, A. 2020. “Drought and Intimate Partner Violence Towards Women in 19 Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa During 2011-2018: A Population-Based Study.” PLoS Med, 17(3).

- 23. Stotsky, J. et al. 2016. “Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of Gender Budgeting Efforts. IMF Working Paper 2016/512.

- 24. Kadama, C. et al. 2018. Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Kolovich, L. (Ed.), Fiscal Policies and Gender Equality (pp. 9-32). International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- 25. Ortiz, I. and Cummins, M. 2021. “Abandoning Austerity: Fiscal Policies for Inclusive Development.” In Gallagher, K. and Gao, H. (Eds.), Building Back a Better Global Financial Safety Net (pp. 11-22). Global Development Policy Center.

- 26. Roy, R. et al. 2006. “Fiscal Space for Public Investment: Towards a Human Development Approach.”

- 27. ATAF, 2021.

- 28. Moore, M. et al. 2018. “Taxing Africa: Coercion, Reform and Development. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- 29. Rogan, M. 2019. Tax Justice and the Informal Economy: A Review of the Debates.” Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing Working Paper 14.

- 30. African Tax Administrative Forum (ATAF). 2021. African Tax Outlook 2021.

- 31. Stotsky, J. et al. 2016. “Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of Gender Budgeting Efforts.” IMF Working Paper 2016/512.

- 32. Coelho, M. et al. 2022. “Gendered Taxes: The Interaction of Tax Policy with Gender Equality.” IMF Working Paper 2022/26.

- 33. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2021. Gender and Capital Budgeting.

- 34. Grown, C. and Valodia, I. 2010. Taxation and Gender Equity: A Comparative Analysis of Direct and Indirect Taxes in Developing and Developed Countries. Routledge.

- 35. Joshi, Anuradha et al. 2020. “Gender and Tax Policies in the Global South.” International Centre for Tax and Development.

- 36. Komatsu, H. et al. 2021. “Gender and Tax Incidence of Rural Land Use Fee and Agricultural In¬come Tax in Ethiopia.” Policy Research Working Papers.

- 38. Lustig, N. 2018. “Commitment to Equity Handbook: Estimating the Impact of Fiscal Policy on Inequality and Poverty.” Brookings Institution Press.

- 39. Grown, C. and Valodia, I. 2010. “Taxation and Gender Equity: A Comparative Analysis of Direct and Indirect Taxes in Developing and Developed Countries.” Routledge.

- 40. Cesar, C. et al. 2022. “Africa’s Pulse: An Analysis of Issues Shaping Africa’s Economic Future.” World Bank.

- 41. Woolard, I. 2018. Recommendations on Zero Ratings in the Value-Added Tax System. Independent Panel of Experts for the Review of Zero Rating in South Africa.

- 42. It is important to distinguish between firms and individuals that are large enough to pay taxes but do not (which include icebergs, e.g., which are registered and therefore partially visible to tax authorities but do not pay their full obligations) and ghosts, e.g., those which should register to pay but do not and there invisible to tax authorities) and firms and individuals that are small and potentially but not necessarily taxable such as street vendors and waste pickers. Rogan, M. (2019). “Tax Justice and the Informal Economy: A Review of the Debates.” Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing Working Paper 14.

- 44. Ligomeka, W. 2019. “Expensive to be a Female Trader: The Reality of Taxation of Flea Market Trad¬ers in Zimbabwe.” International Center for Tax and Development Working Paper 93.

By Mavis Owusu-Gyamfi

Mavis Owusu-Gyamfi explores the role of gender equality in Africa’s economic development.

By Cina Lawson

Cina Lawson describes Togolese initiatives to expand the reach of social protection.

By Malado Kaba

Malado Kaba identifies four priorities for governments to transform the informal sector and economic prospects for African women.

By J. Jarpa Duwuni

J. Jarpa Dawuni identifies priority areas to expand access to justice for women and girls in Africa.

Next Chapter

06 | Climate Change Adapting to a new normal

Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2023

On January 30, AGI hosted a Foresight Africa launch featuring a high-level panel of leading Africa experts to offer insights on regional trends along with recommendations for national governments, regional organizations, multilateral institutions, the private sector, and civil society actors as they forge ahead in 2022.

Africa in Focus

What should be the top priority for Africa in 2023?

BY ALOYSIUS UCHE ORDU

Aloysius Uche Ordu introduces Foresight Africa 2023, which outlines top priorities for the year ahead and offers recommendations for supporting Africa at a time of heightened global turbulence.

Foresight Africa Podcast

The Foresight Africa podcast celebrates Africa’s dynamism and explores strategies for broadening the benefits of growth to all people of Africa.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

What does gender equality look like today?

Date: Wednesday, 6 October 2021

Progress towards gender equality is looking bleak. But it doesn’t need to.

A new global analysis of progress on gender equality and women’s rights shows women and girls remain disproportionately affected by the socioeconomic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling with disproportionately high job and livelihood losses, education disruptions and increased burdens of unpaid care work. Women’s health services, poorly funded even before the pandemic, faced major disruptions, undermining women’s sexual and reproductive health. And despite women’s central role in responding to COVID-19, including as front-line health workers, they are still largely bypassed for leadership positions they deserve.

UN Women’s latest report, together with UN DESA, Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2021 presents the latest data on gender equality across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The report highlights the progress made since 2015 but also the continued alarm over the COVID-19 pandemic, its immediate effect on women’s well-being and the threat it poses to future generations.

We’re breaking down some of the findings from the report, and calling for the action needed to accelerate progress.

The pandemic is making matters worse

One and a half years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the toll on the poorest and most vulnerable people remains devastating and disproportionate. The combined impact of conflict, extreme weather events and COVID-19 has deprived women and girls of even basic needs such as food security. Without urgent action to stem rising poverty, hunger and inequality, especially in countries affected by conflict and other acute forms of crisis, millions will continue to suffer.

A global goal by global goal reality check:

Goal 1. Poverty

In 2021, extreme poverty is on the rise and progress towards its elimination has reversed. An estimated 435 million women and girls globally are living in extreme poverty.

And yet we can change this .

Over 150 million women and girls could emerge from poverty by 2030 if governments implement a comprehensive strategy to improve access to education and family planning, achieve equal wages and extend social transfers.

Goal 2. Zero hunger

The global gender gap in food security has risen dramatically during the pandemic, with more women and girls going hungry. Women’s food insecurity levels were 10 per cent higher than men’s in 2020, compared with 6 per cent higher in 2019.

This trend can be reversed , including by supporting women small-scale producers, who typically earn far less than men, through increased funding, training and land rights reforms.

Goal 3. Good health and well-being

Disruptions in essential health services due to COVID-19 are taking a tragic toll on women and girls. In the first year of the pandemic, there were an estimated 1.4 million additional unintended pregnancies in lower and middle-income countries.

We need to do better .

Response to the pandemic must include prioritizing sexual and reproductive health services, ensuring they continue to operate safely now and after the pandemic is long over. In addition, more support is needed to ensure life-saving personal protection equipment, tests, oxygen and especially vaccines are available in rich and poor countries alike as well as to vulnerable population within countries.

Goal 4. Quality education

A year and a half into the pandemic, schools remain partially or fully closed in 42 per cent of the world’s countries and territories. School closures spell lost opportunities for girls and an increased risk of violence, exploitation and early marriage .

Governments can do more to protect girls education .

Measures focused specifically on supporting girls returning to school are urgently needed, including measures focused on girls from marginalized communities who are most at risk.

Goal 5. Gender equality

The pandemic has tested and even reversed progress in expanding women’s rights and opportunities. Reports of violence against women and girls, a “shadow” pandemic to COVID-19, are increasing in many parts of the world. COVID-19 is also intensifying women’s workload at home, forcing many to leave the labour force altogether.

Building forward differently and better will hinge on placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation

In 2018, nearly 2.3 billion people lived in water-stressed countries. Without safe drinking water, adequate sanitation and menstrual hygiene facilities, women and girls find it harder to lead safe, productive and healthy lives.

Change is possible .

Involve those most impacted in water management processes, including women. Women’s voices are often missing in water management processes.

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy

Increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon solutions is driving an unprecedented transformation of the energy sector. But women are being left out. Women hold only 32 per cent of renewable energy jobs.

We can do better .

Expose girls early on to STEM education, provide training and support to women entering the energy field, close the pay gap and increase women’s leadership in the energy sector.

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth

The number of employed women declined by 54 million in 2020 and 45 million women left the labour market altogether. Women have suffered steeper job losses than men, along with increased unpaid care burdens at home.

We must do more to support women in the workforce .

Guarantee decent work for all, introduce labour laws/reforms, removing legal barriers for married women entering the workforce, support access to affordable/quality childcare.

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure

The COVID-19 crisis has spurred striking achievements in medical research and innovation. Women’s contribution has been profound. But still only a little over a third of graduates in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics field are female.

We can take action today.

Quotas mandating that a proportion of research grants are awarded to women-led teams or teams that include women is one concrete way to support women researchers.

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities

Limited progress for women is being eroded by the pandemic. Women facing multiple forms of discrimination, including women and girls with disabilities, migrant women, women discriminated against because of their race/ethnicity are especially affected.

Commit to end racism and discrimination in all its forms, invest in inclusive, universal, gender responsive social protection systems that support all women.

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities

Globally, more than 1 billion people live in informal settlements and slums. Women and girls, often overrepresented in these densely populated areas, suffer from lack of access to basic water and sanitation, health care and transportation.

The needs of urban poor women must be prioritized .

Increase the provision of durable and adequate housing and equitable access to land; included women in urban planning and development processes.

Goal 12. Sustainable consumption and production; Goal 13. Climate action; Goal 14. Life below water; and Goal 15. Life on land

Women activists, scientists and researchers are working hard to solve the climate crisis but often without the same platforms as men to share their knowledge and skills. Only 29 per cent of featured speakers at international ocean science conferences are women.

And yet we can change this .

Ensure women activists, scientists and researchers have equal voice, representation and access to forums where these issues are being discussed and debated.

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions

The lack of women in decision-making limits the reach and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency recovery efforts. In conflict-affected countries, 18.9 per cent of parliamentary seats are held by women, much lower than the global average of 25.6 per cent.

This is unacceptable .

It's time for women to have an equal share of power and decision-making at all levels.

Goal 17. Global partnerships for the goals

There are just 9 years left to achieve the Global Goals by 2030, and gender equality cuts across all 17 of them. With COVID-19 slowing progress on women's rights, the time to act is now.

Looking ahead

As it stands today, only one indicator under the global goal for gender equality (SDG5) is ‘close to target’: proportion of seats held by women in local government. In other areas critical to women’s empowerment, equality in time spent on unpaid care and domestic work and decision making regarding sexual and reproductive health the world is far from target. Without a bold commitment to accelerate progress, the global community will fail to achieve gender equality. Building forward differently and better will require placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: How Bias Against Women Persists in Female-Dominated Workplaces

- Amber L. Stephenson,

- Leanne M. Dzubinski

A look inside the ongoing barriers women face in law, health care, faith-based nonprofits, and higher education.

New research examines gender bias within four industries with more female than male workers — law, higher education, faith-based nonprofits, and health care. Having balanced or even greater numbers of women in an organization is not, by itself, changing women’s experiences of bias. Bias is built into the system and continues to operate even when more women than men are present. Leaders can use these findings to create gender-equitable practices and environments which reduce bias. First, replace competition with cooperation. Second, measure success by goals, not by time spent in the office or online. Third, implement equitable reward structures, and provide remote and flexible work with autonomy. Finally, increase transparency in decision making.

It’s been thought that once industries achieve gender balance, bias will decrease and gender gaps will close. Sometimes called the “ add women and stir ” approach, people tend to think that having more women present is all that’s needed to promote change. But simply adding women into a workplace does not change the organizational structures and systems that benefit men more than women . Our new research (to be published in a forthcoming issue of Personnel Review ) shows gender bias is still prevalent in gender-balanced and female-dominated industries.

- Amy Diehl , PhD is chief information officer at Wilson College and a gender equity researcher and speaker. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield). Find her on LinkedIn at Amy-Diehl , Twitter @amydiehl , and visit her website at amy-diehl.com

- AS Amber L. Stephenson , PhD is an associate professor of management and director of healthcare management programs in the David D. Reh School of Business at Clarkson University. Her research focuses on the healthcare workforce, how professional identity influences attitudes and behaviors, and how women leaders experience gender bias.

- LD Leanne M. Dzubinski , PhD is acting dean of the Cook School of Intercultural Studies and associate professor of intercultural education at Biola University, and a prominent researcher on women in leadership. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield).

Partner Center

The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality

The economic downturn caused by the current COVID-19 outbreak has substantial implications for gender equality, both during the downturn and the subsequent recovery. Compared to “regular” recessions, which affect men’s employment more severely than women’s employment, the employment drop related to social distancing measures has a large impact on sectors with high female employment shares. In addition, closures of schools and daycare centers have massively increased child care needs, which has a particularly large impact on working mothers. The effects of the crisis on working mothers are likely to be persistent, due to high returns to experience in the labor market. Beyond the immediate crisis, there are opposing forces which may ultimately promote gender equality in the labor market. First, businesses are rapidly adopting flexible work arrangements, which are likely to persist. Second, there are also many fathers who now have to take primary responsibility for child care, which may erode social norms that currently lead to a lopsided distribution of the division of labor in house work and child care.

This is a preliminary version of an evolving project—feedback highly appreciated. We thank Fabrizio Zilibotti for early discussions that helped shape some of the ideas in this paper. Financial support from the German Science Foundation (through CRC-TR-224 (project A3) and the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz-Prize) and the National Science Foundation (grant SES-1949228) is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Mentioned in the News

More from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Publications

- Key Findings

- Infographics

- Economy profiles

- Full report

Global Gender Gap Report 2023

Gender gaps in the workforce

This chapter sheds light on global workforce, leadership and skilling patterns across industries and across time to give a more nuanced picture of the current anatomy of gender gaps in labour markets and senior leadership to equip decision-makers with the data to tackle gender gaps in the most targeted and impactful way possible.

Evolving gender gaps in the global labour market

As we approach the middle of 2023, the global economy has resisted slipping into recession, yet the risks to future growth and broad-based prosperity remain many and expected volatility high. Risks include those inherent in ongoing geopolitical conflicts, open questions about the future of trade and global supply chains, large-scale climate events, as well as the disruptive impact of emerging technologies. Many of these risks are expected to have a disproportionately negative effect on women, especially for women in vulnerable situations.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts modest global growth in the near term at 2.8% in 2023, improving marginally in 2024. 1 Yet, further down the line, the World Bank projects falling long-term global economic prospects in the absence of deep structural transformation. 2 Unlocking all talent in the workforce, in innovation and leadership will be critical in brightening the current prospects.

Increases in the cost-of-living are set to remain elevated, with baseline global inflation expected around 7% in 2023, significantly above traditional central bank targets of 2%. This will continue to put disproportionate pressure on individuals with low incomes. 3 Furthermore, labour markets are showing signs of cooling after a post-pandemic period of high demand for workers and upward pressures on wages. In the longer run, International Labour Organization (ILO) projections point to rising global unemployment and informal work as well as further slowing productivity growth. 4

The 2022 edition of the Global Gender Gap Report raised concerns over the state of gender parity in the labour market. Not only was women’s participation slipping globally, but other markers of economic opportunity were showing substantive disparities between women and men. Since the last edition, while women have (re-)entered the labour force at higher rates than men globally, leading to a small recovery in gender parity in the labour-force participation rate, gaps remain wide overall and in several specific dimensions.

Labour-force participation

Between 2019 and 2020, the global women’s labour-force participation rate declined by 3.4%, as compared to 2.4% for men. 5 Women have been (re-)entering the workforce at a slightly higher rate than men since then, resulting in a modest recovery in gender parity. Between the 2022 and 2023 editions, parity in the labour-force participation rate increased from 63% to 64%. However, the recovery remains unfinished, as parity is still at the second-lowest point since the first edition of the index in 2006 and significantly below its 2009 peak of 69%.

At the regional level, developments have been uneven. After all regions saw a downturn in the 2022 edition, the most marked recovery this year is observed in Southern Asia, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean, Eurasia and Central Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, then Sub-Saharan Africa. Parity in labour-force participation in both Europe and North America saw virtually no change compared to the 2022 edition, while the Middle East and North Africa saw a slight drop.

Overall, the lowest levels of parity in participation on average at the regional level are in the Middle East and North Africa (30%) and Southern Asia (34%). Of all regions, North America attains the highest score of 84%, followed by Europe at 82% and East Asia and the Pacific at 80%.

Unemployment

Labour-force participation rates mask trends in unemployment since the former counts both those working and those unemployed but actively looking for employment.

After the surge in unemployment due to pandemic lock-downs, both men’s and women’s unemployment rates have almost returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2.3). Historically, women have consistently faced higher unemployment rates than men, except for a short period in 2020 when the pandemic led to a peak in unemployment for both genders (and slightly more so for men). Since then, the likelihood of women experiencing unemployment is again higher than for men, compounding the gender gap observed in labour- force participation: not only are fewer women participating in the labour market, but out of those who are, relatively fewer are employed. According to the latest data from the International Labour Organization (ILO), the global unemployment rate stands at approximately 4.5% for women and 4.3% for men. 6

Disparity in female and male unemployment is highest in the Middle East and North Africa region, where the parity ratio currently stands at 2.69, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean, with 1.51 parity, and Eurasia and Central Asia at 1.21. East Asia and the Pacific is the only region below parity (1.0), meaning unemployment is lower for female workers than for men.

Figure 2.4 further illustrates that unemployment patterns for women tend to be an amplified version of what is experienced by men. The likelihood of unemployment among workers with different levels of educational attainment tends to vary based on a country’s income level. In many advanced economies individuals with basic education face a higher risk of unemployment, and this pattern is particularly pronounced for women (Figure 2.4.a). Conversely, in low- and middle-income countries, individuals with advanced education are more susceptible to unemployment, with women again disproportionately affected (Figure 2.4.b).

Further, women face greater difficulties in their search for employment. An individual is considered unemployed if they are actively looking for work and are available to start a job within a short notice period, typically a week. However, this definition assumes that men and women face similar conditions in their job searches and are equally available to take up employment on short notice. To address these limitations, the ILO has introduced the “jobs gap” measure, which encompasses all individuals who desire employment but are currently unemployed, including those actively seeking employment and readily available to start work on short notice, those not actively searching employment opportunities and not available for immediate job placement, and those searching for employment but unable to join the workforce on short notice.

According to this ILO estimate, 12.3%, or 473 million people, fall into the jobs gap category. Women’s jobs gap rate of 15% is significantly higher than men’s jobs gap rate of 10.5%. 7 Among both men and women actively seeking employment, women are also significantly less likely to be readily available to start work on short notice than men. 8 Evidence suggests that these gaps persist due to both a lack of suitable job opportunities and lack of access to existing opportunities, in turn due to disproportionate care responsibilities and discouragement to search for opportunities, among other factors. 9

Working conditions

When women secure employment, they often face substandard quality of working conditions. A significant portion of the recovery in employment since 2020 can be attributed to informal employment. The ILO estimates that out of every five jobs created for women, four are within the informal economy, whereas for men,the ratio is two out of every three jobs. 10 While informal work is critical and may drive production and employment, it is often a “last-resort” option characterized by a lack of legal protections, social security, and decent working conditions, and poses numerous challenges for women’s economic and social well-being.

Overall, over the last decade, there has been insufficient progress in improving working conditions, interrupted by shocks in key labour-force indicators. Women still encounter barriers entering the workforce, struggle to find jobs, and face relatively poorer working conditions, calling for renewed focus by both governments and business leaders. Across the world, inadequate care systems are one of the largest roadblocks to improving gender gaps in the labour market.

Workforce representation across industries

In addition to overall barriers to labour-force participation and employment, global data provided by LinkedIn shows persistent skewing in women’s representation in the workforce across industries. 11

In LinkedIn’s sample, which comprises all LinkedIn users in 163 countries, women account for 41.9% of the workforce (ILO reports 39.5% in 2021 for the global workforce 12 ). Trends over time indicate that the share of women hired into the total workforce saw upward trends between 2016-2019, increasing from 41.6% to 42.1% before plateauing in 2020. In the last three years, the proportion of jobs held by women increased again in 2021 (+0.12 percentage points), followed by a slight drop in 2022 (-0.03 percentage points) and a steeper decline in 2023 (-0.31 percentage points).

A closer look across industries reveals that Healthcare and Care Services (64.7%) continues to be a female-dominated field. Women also outnumber men, though to a lesser degree, in Education (54.0%) and Consumer Services (51.8%). The Government and Public sector is the only one showcasing a fairly balanced distribution of men and women across occupations, with women accounting for almost half (49.7%) of the workforce in 2023 (down from 50% in 2022). Industries where women are under-represented yet still make up more than 40% of the workforce (i.e. above the global average score of 41.9%, and the median score of 42.4%) are Retail (48.7%), Entertainment Providers (48.4%), Administrative and Support Services (46.5%), Real Estate (44.7%), Accommodation and Food (43.3%) and Financial Services (42.4%). Finally, women are poorly represented in sectors like Oil, Gas and Mining (22.7%) and Infrastructure (22.3%), where they account for less than one-quarter of workers.

The drop in women’s workforce representation between 2022 and 2023 noted earlier is observed across industries, but especially in Consumer Services (-0.71 percentage points), Accommodation and Food (-0.67 percentage points), Agriculture (-0.65 percentage points), and Wholesale (-0.62 percentage points).

The share of women in Accommodation and Food, however, has been experiencing a downward trend since 2020 – along with women’s share in Retail and, to a smaller extent, in Healthcare and Care Services and Financial Services (for the latter, the decline started in 2018).

The industries where women’s representation has been trending markedly upward since 2016 (albeit dipping at the beginning of 2023) are: Government and Public Sector (+1.8 percentage points in 2022 compared to 2016), Agriculture (+1.24 percentage points), Infrastructure (+1.16 percentage points), Consumer Services (+1.1 percentage points), Professional Services (+0.95 percentage points) and Technology, Information and Media (+0.94 percentage points).

Representation of women in senior leadership

LinkedIn data indicates that the share of women in senior leadership positions – where “senior leadership” is defined as Director, 13 Vice-President (VP) 14 or C-suite 15 – is at 32.2% in 2023 nearly 10 percentage points lower than women’s overall 2023 workforce representation of 41.9%. Women continue to be outnumbered by men in senior leadership positions across all industries, especially so in fields like Manufacturing (24.6% women); Agriculture (23.3%); Supply Chain and Transportation (23.0%); Oil, Gas and Mining (18.6%); and Infrastructure (16.1%).

The sectors where gender diversity in senior leadership is more present, with women taking up between one-third and one-half of senior leadership roles, are: Healthcare and Care Services (49.5%), Education (46.0%), Consumer Services (45.9%), Government and Public Sector (40.3%), Retail (38.5%), Entertainment Providers (37.1%), Administrative and Support Services (34.7%), and Accommodation and Food (33.5%).

Organizational hierarchy levels

When further disaggregating the data by seniority levels, it becomes apparent that different industries display different intensities and patterns when it comes to the “drop to the top” – the degree to which female representation drops as seniority level increases. This is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

Representation drops to 25% in C-suite positions on average, which is just more than half of the representation in entry-level positions, at 46%. Women fare relatively better in industries such as Consumer Services, Retail, and Education, which register ratios of C-suite vs entry level representation between 64% and 68%, as shown in Table 2.1. Construction, Financial Services and Real Estate, on the other hand, present the toughest conditions for aspiring female leaders, with a ratio of C-suite to entry-level representation of less than 50%.

On average, across industries, a significant gap is seen when comparing the share of women in senior contributor positions (44.0%) to that of women in Manager (35.5%) or Director roles (36.8%). The disproportionate share of men holding top positions is even starker among higher-ranked positions, where men account for 71.7% of Vice-President (VP) roles and 74.6% of C-suite positions on average.

Industries with the greatest discrepancy between women’s share in senior contributor roles and that in either Director or higher-ranked roles (VP or C-suite) are Real Estate (-12.9 percentage points), Administrative and Support Services (-11.7 percentage points), Entertainment Providers (-10.9 percentage points) and Healthcare and Care Services (-10 percentage points). The fields with a better retention of women and thus less abrupt drops in women’s share in senior contributor versus senior leader roles are Education (-1.3 percentage points) and Consumer Services (-1.4 percentage points).

Despite a significant drop in gender diversity from more junior to more senior levels, Healthcare and Care Services is the only industry where women surpass men in either Manager (60.7%) or Director (53.8%) positions, while also displaying the highest share of women in either VP (46.8%) or C-suite (39.8%) roles. The next-best industries for female senior leaders are Consumer Services (e.g. 49.9% of Director positions, 46.3% of VP roles and 38.4% of C-suite roles are held by women) and Education (e.g. 49.3% of Director positions, 41.4% of VP roles and 38.6% of C-suite roles are held by women).

Senior leadership

Despite the overall “drop to the top”, women have increased their representation in senior leadership since 2016 across all industries. The sectors that made gains in women taking up Director roles, for instance, are Technology, Information and Media (an increase of 2.4 percentage points from 30.8% in 2016 to 33.2% in 2022), Professional Services (+2.1 percentage points) and Government and Public Sector (+2 percentage points). Slower progression over time is noticed in the field of Entertainment Providers (+0.4 percentage points) and in Healthcare and Care Services (+0.5 percentage points).

The latter, however, displays one of the more marked improvements of women’s representation in VP roles, with an increase of 1.6 percentage points between 2016-2022, alongside even more notable progress in Technology, Information and Media as well as Professional Services (both registering a rise of 1.9 percentage points). Women’s ranks in VP positions have not increased as quickly in either Accommodation and Food (+0.4 percentage points) or Administrative and Support Services (+0.3 percentage points).

The global share of women taking up senior leadership roles (Director, VP or C-suite) had been on an upward slope in recent years, increasing from 31.1% in 2016 to 32.6% in 2022, yet dropping to 32.2% in the first quarter of 2023. Between 2016 and mid-2022, progress on women’s representation in senior leadership was seen across industries: upward trends were steeper in Technology, Information and Media (+1.98 percentage points); Professional Services (+1.96 percentage points); Government and Public Sector (+1.93 percentage points); Manufacturing (+1.84 percentage points); and Utilities (+1.75 percentage points).

Yet, women’s workforce representation decreased at all levels of seniority across the examined industries in the early 2023 data (-0.31 percentage points), and the decline is stronger for senior leader positions (-0.33 percentage points). The recent drop in the representation of women in top positions is especially visible in sectors like Consumer Services (-0.58 percentage points), Healthcare and Care Services (-0.42 percentage points), Real Estate (-0.41 percentage points), and Infrastructure and Agriculture (-0.4 percentage points).

Leadership hiring rates

A similar trajectory is observed when tracking the evolution of leadership hiring rates over time, which in turn affects the overall leadership representation rates as seen in Figure 2.8. For the past eight years, the proportion of women hired into leadership positions has been steadily increasing by about 1% per year globally. In the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there was a decline followed by a recovery matching or in some industries even exceeding the pre-pandemic trajectory. However, this trend shows a clear reversal starting in 2022, bringing the 2023 rate back to 2021 levels (Figure 2.9).

Progress in hiring women into top positions has not been advancing at the same rate across industries since 2016 (Figure 2.10). Some sectors are displaying upward trends over several years (Financial Services; Professional Services; Oil, Gas, and Mining), while others are fluctuating (Government Administration, Administrative and Support Services).

The recent downturn shown in Figure 2.9 has been observed across industries. Estimates by LinkedIn show that as of May 2023, the proportion of women hired into leadership is lower than what would be predicted based on the pre-2022 trend line for most industries apart from Construction; Real Estate; Oil, Gas and Mining; Education; and Agriculture, which continue to stay on trend. The most affected industries are Technology and Professional Services, which in May 2023 was 4 percentage points below trend, and Entertainment Providers and Wholesale, which were 3 percentage points below trend (Figure 2.10).

Gender gaps in the labour markets of the future

Stem occupations.

Examining more closely science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) occupations – an important set of jobs that are well remunerated and expected to grow in significance and scope in the future – Linkedin data on members’ job profiles show that women remain significantly underrepresented in the STEM workforce. 16 Women make up almost half (49.3%) of total employment across non-STEM occupations, but just 29.2% of all STEM workers (Figure 2.11). The fraction of women in STEM jobs has nonetheless grown by 1.58 percentage points from 27.6% in 2015, and the growth outpaces that for non-STEM jobs (0.37 percentage points).

This data from LinkedIn suggests that one first point of intervention in improving numbers could be to smooth the transition for female STEM graduates from university to the world of work. While the percentage of female STEM graduates entering into STEM employment is increasing with every cohort, the numbers on the integration of STEM university graduates into the labour market show that the retention of women in STEM one year after graduating sees a significant drop. Figure 2.12 shows that among those graduating with a STEM degree in 2017, for instance, 35.5% were women; a year after graduation, 29.6% of those holding STEM jobs were women (a drop of 5.9 percentage points). In 2021, women comprised 38.5% of STEM degree recipients compared with 31.6% of STEM workers one year following graduation (a drop of 6.9 percentage points). Once in the workforce, however, women are generally less likely to drop out in the first years (until they start climbing the hierarchy, see Figure 2.12. For example, the difference between year 2 after graduation and year 1 after graduation is around 1 or 2 percentage points.

When it comes to STEM occupations, women are scarce throughout all industries, apart from Healthcare and Care Services, where they represent 51.5% of the workforce. Gender parity in STEM jobs across industries varies widely. In Technology, Information and Media, for example, the share of STEM occupations stands at 23.4% for women versus 43.6% for men, meaning that women are half (53.8%) as likely to take up STEM employment in this field. In other industries, such as Real Estate, women are only 35% as likely as men to work in STEM, whereas in Agriculture and Education, parity reaches 69% and 61.5% respectively.

Women generally tend to be underrepresented in leadership roles, but especially in STEM work: they account for 29.4% of entry-level workers and 29.9% of senior workers, but the share of women in Manager or Director positions drops to one-quarter (25.5% and 26.7% respectively). Women’s representation in high-level leadership roles such as VP and C-suite drops even lower, to 17.8% and 12.4%, respectively.

AI occupation take-up

As AI continues to revolutionize the labour market, a new metric has been developed in collaboration with LinkedIn to analyse the gender gap in the distribution of AI talent across industries that have experienced significant impacts from AI. 17

The concentration of AI talent overall has surged, increasing six times between 2016 and 2022. The extent of this increase varies across industries, with Technology, Education, Professional Services, and Financial Services exhibiting the highest concentration of AI talent.

However, when it comes to gender gaps, representation of female AI talent is lower compared to men in all large industries, as depicted in Figure 2.14. Overall, as of 2022, only 30% of AI talent were female. The industries with the highest concentration of AI talent include those with a low representation of women, as well as those with higher representation, such as Financial Services (female representation of 28%); Education (40%); Professional Services (31%); and Technology, Information, and Media (25%). Additionally, Consumer Services (38%) and Government and Public Sector (35%) are industries with a large gender gap overall and in AI. Female representation in AI is progressing, yet very slowly. The percentage of women working in AI today is roughly 4% higher than it was in 2016 (~26%).

The gender gap in AI professionals has far-reaching implications that extend beyond the realm of technology. It exacerbates the existing gender disparities in the workforce, particularly in a rapidly-growing sector like AI that holds significant influence over various industries. As AI is disrupting critical solutions in knowledge work, supply chains, hiring, education, health and the environment, among others, underrepresentation of women in AI can impede the realization of the innovation premium associated with diversity. In addition, when women’s perspectives, experiences and insights are not adequately incorporated into AI development and deployment, biased algorithms and technologies may be perpetuated, risking biased and suboptimal solutions to emerging challenges.

Gender gaps in the skills of the future

As labour markets get reconfigured with the emergence of new working arrangements and frontier technologies, education and skills do not only drive employability, productivity and wages, they also impact people’s access to temporal and geographical flexibility and their ability to balance caregiving responsibilities around work. This has been an important factor for labour-force participation choices among women and men, their career progression and their stress levels, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began.18

It is no longer sufficient to frontload skills through training in the initial phase of the career for a single qualification throughout a lifetime.19 In the changing job market, demand for skills is rapidly shifting. As illustrated in Figure 2.15, creative thinking, analytical thinking, technological literacy, curiosity and lifelong learning and resilience, flexibility and agility are increasing in demand, according to the Forum’s Future of Jobs survey that studied the business expectations of evolution of the importance of these skills.

To match supply for these rapidly evolving demand for skills, governments and organizations have been calling for policy focus and financial investment into adult education, training and lifelong learning, in line with SDG 4 (“Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”).20 In this context, the emergence of online learning has introduced a wide array of new educational solutions that can assist individuals in adapting to the dynamic job market.

Online learning offers the advantages of flexibility, accessibility and customization, enabling learners to acquire knowledge in a manner that suits their specific needs and circumstances. However, women and men currently do not have equal opportunties and access to these online platforms, given the persistent digital divide. 21 Even when they do use these platforms, there are gender gaps in skilling, especially those that are projected to grow in importance and demand. In the subsections that follow, analysis developed in collaboration with Coursera reveals important aspects related to gender gaps in the enrollment, attainment and efficiency in the acquisition of skills that are expected to grow in importance.

Online enrolment