- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Handbook of Feminist Research Theory and Praxis

- Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber - Boston College, USA

- Description

This Handbook presents both a theoretical and practical approach to conducting social science research on, for, and about women. It develops an understanding of feminist research by introducing a range of feminist epistemologies, methodologies, and emergent methods that have had a significant impact on feminist research practice and women's studies scholarship. Contributors to the Second Edition continue to highlight the close link between feminist research and social change and transformation.

The new edition expands the base of scholarship into new areas, with 12 entirely new chapters on topics such as the natural sciences, social work, the health sciences, and environmental studies. It extends discussion of the intersections of race, class, gender, and globalization, as well as transgender, transsexualism and the queering of gender identities. All 22 chapters retained from the first edition are updated with the most current scholarship, including a focus on the role that new technologies play in the feminist research process.

Discover the latest news from Author Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber: Visit http://www.fordham.edu/Campus_Resources/eNewsroom/topstories_2397.asp

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

'The Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis is a well-developed contribution to the body of feminist literature. It effectively highlights the connection between feminist research and social change by drawing upon the range of existent feminist epistemologies, methods, and practices, all of which adopt different means of conceptualising, researching, and ultimately representing the lived experiences of women, varied across the lines of race, class and/or other demographics. The text, while accessible for both research and teaching purposes, perhaps most importantly draws our attention to the need to be critically aware in the process of conducting feminist research. One must address the challenges, research developments, and, crucially, the diversity amongst women, that may be incurred in attempting to research, understand, and accurately represent the lived experiences of all women'

Key Features of the Second Edition

- Expands the base of scholarship into new areas , with new chapters on the place of feminism in the natural sciences, social work, the health sciences, and environmental studies

- Extends discussion of the intersections of race, class, gender, and globalization , with new chapter on issues of gender identity

- Updates all chapters retained from the first edition with the most current scholarship , including a focus on the role that new technologies play in the feminist research process

- Includes research case studies in each chapter , providing readers with step-by-step praxis examples for conducting their own research projects

- Offers new research and teaching resources, including discussion questions, and a list of websites as well as journal references geared to each chapter's content

We continue to reach out to two primary constituencies. The first is researchers, practitioners, and students within, and outside the academy, who conduct a variety of research projects and who are interested in consulting "cutting edge" research methods and gaining insights into the overall research process. This group also includes policymakers and activists who are interested in how to conduct research for social change. The second edition's audience continues to include academic researchers who, it is hoped, will use the Handbook in their research scholarship, as well as in their courses, at the upper-level undergraduate and graduate levels, as a main or supplementary text.

The second edition of the Handbook also includes a range of new research and teaching resources for both these readership groups with a list of websites as well as journal references that are specifically geared to each chapter's content. In addition, the second edition has an enhanced pedagogical feature at the end of each chapter that provides a set of key discussion questions intended as a praxis application for the ideas and concepts contained in each chapter.

The second edition's Handbook structure contains three primary sections that that represent a more finely tuned focus on theory and praxis, including the an enhanced set of case study research examples for each chapter that provide readers with a step-by- step praxis examples for conducting their own research projects.

Section one, "Feminist Perspectives on Knowledge Building,"

traces the historical rise of feminist research and begins with the early link of feminist epistemologies and perspectives within the research process. We trace the contours of early feminist inquiry and introduce the reader to the history, and historical debates, of and within feminist scholarship. We explore the androcentrism (male bias) in traditional research projects and the alternative set of questions feminist researchers bring to the research endeavor. We explore the political process of knowledge building by introducing the reader to the link between knowledge, authority, representation and power relations.

The chapters in Section One, introduce the unique knowledge frameworks feminists offer to enhance our understanding of the social reality. We explore some of the range of issues and questions feminists have addressed and the emphasis of feminist epistemologies and methodologies on understanding of the diversity of women's experiences, the commitment to the empowerment of women and other oppressed groups.

We examine a broad spectrum of the most important feminist perspectives and we take an in-depth look at how a given methodology intersects with epistemology and method to produce set of research practices. The Handbook's overall thesis is that any given feminist perspective does not preclude the use of specific methods, but serves to guide how a given method is practiced in the research process. While each feminist perspective is distinct, it sometimes shares elements with other perspectives. We discuss the similarities and differences across the spectrum of feminist perspectives on knowledge building.

Section two of the Handbook , "Feminist Research Praxis," examines how feminist researchers utilize a range of research methods in the service of feminist perspectives. Feminist researchers use a range of qualitative and quantitative as well as mixed and multi methods, and this section examines the unique characteristics feminists researchers bring to the practice of feminist research, by by maintaining a tight link between their theoretical perspectives and methods practices.

This section includes three new chapters. Deboleena Roy's chapter titled, "Feminist Approaches to Inquiry in the Natural Sciences: Practices for the Lab," tackles how feminist researchers go about their work within a natural science laboratory setting. She notes the importance of being reflexive of the range of ethical conundrums that are contained within practicing the scientific method. Roy suggests the importance of infusing laboratory research with a sense of "playfulness" and what she terms a "feeling around" in the pursuit of feminist laboratory knowledge building, that privileges a reaching out to other scientists in order to build a community of "togetherness" among researchers.

Stephanie Wahab, Ben Anderson-Nathe, and Christina Gringeri's new chapter, "Joining the Conversation: Social Work Contributions to Feminist Research," provides exemplary case studies of the practice of feminist research within a social work setting. Wahab et al. suggest that social work history of being grounded in praxis, ethics and reflection, can contribute to feminist knowledge building. In turn, social work's engagement with feminist theory, may help to disrupt the assumptions of knowledge contain in social work practice. Kristen Intemann's new chapter, "Putting Feminist Research Principles Into Practice," suggests that research principles of feminist praxis can benefit scientific research. Intemann proposes that scientific communities need to tend to issues of difference in the scientific research process by including diverse researchers (in terms of experiences, social positions, and values), that will serve to enhance a critical reflection on scientific research praxis with the goals of enhancing the perspective of the marginalized, and working towards a multiplicity of conceptual models.

Section III of the Handbook, "Feminist Issues and Insights in Practice and Pedagogy" examines some of the current tensions within feminist research and discusses a range of strategies for positioning of feminist research within the dominant research paradigms and emerging research practices. Section III also introduces some feminist "conundrums" regarding knowledge building that deal with issues of truth, reason logic and ethics. Section III also tackles the conceptualization of difference and its practice. In addition, it addresses how feminist researchers can develop an empowered feminist community of scholars across transnational space. Section three also focuses on issues within the practice of feminist pedagogy that includes a discussion of how feminists can or should convey the range of women's scholarship that differentiates it from the charge that women's studies scholarship conveys only ideology not knowledge.

A new chapter added to this section is Katherine Johnson's contribution titled, "Transgender, Transsexualism, and the Queering of Gender Identities: Debates for Feminist Research." Johnson examines some of the core issues of contention within queer studies with the goal of identify those theoretical perspectives that have particular relevance to feminist researchers. Johnson argues that feminist researchers need to be cognizant of the range of identity positions with regard to gender identities. Johnson encourages feminist researchers to explore definitions, terminology, and areas for coalitions in order to promote the crossing of identity borders. Johnson's work analyzes the dialogues between feminism and transgender, transsexual, and queer studies and at how the fields may work together to more robust research.

Sharlene Hesse-Biber and Abigail Brooks' introduction to this section remind us that "There is no one feminist viewpoint that defines feminist inquiry." But rather "feminists continue to engage in and dialogue across a range of diverse approaches to theory, praxis, and pedagogy" (Hesse-Biber & Brooks, this volume).

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1: FEMINIST RESEARCH

Chapter 2: FEMINIST EMPIRICISM

Select a Purchasing Option

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory

Lisa Disch is Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of Michigan.

Mary Hawkesworth, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Women's and Gender Studies, Rutgers University.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory provides an overview of the analytical frameworks and theoretical concepts feminist theorists have developed to challenge established knowledge. Leading feminist theorists, from around the globe, provide in-depth explorations of a diverse array of subject areas, capturing a plurality of approaches. The Handbook raises new questions, brings new evidence, and poses significant challenges across the spectrum of academic disciplines, demonstrating the interdisciplinary nature of feminist theory. The chapters offer innovative analyses of the central topics in social and political science (e.g. civilization, development, divisions of labor, economies, institutions, markets, migration, militarization, prisons, policy, politics, representation, the state/nation, the transnational, violence); cultural studies and the humanities (e.g. affect, agency, experience, identity, intersectionality, jurisprudence, narrative, performativity, popular culture, posthumanism, religion, representation, standpoint, temporality, visual culture); and discourses in medicine and science (e.g. cyborgs, health, intersexuality, nature, pregnancy, reproduction, science studies, sex/gender, sexuality, transsexuality) and contemporary critical theory that have been transformed through feminist theorization (e.g. biopolitics, coloniality, diaspora, the microphysics of power, norms/normalization, postcoloniality, race/racialization, subjectivity/subjectivation). The Handbook identifies the limitations of key epistemic assumptions that inform traditional scholarship and shows how theorizing from women’s and men’s lives has profound effects on the conceptualization of central categories, whether the field of analysis is aesthetics, biology, cultural studies, development, economics, film studies, health, history, literature, politics, religion, science studies, sexualities, violence, or war.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Feminist Theory

Jo Ann Arinder

Feminist theory falls under the umbrella of critical theory, which in general have the purpose of destabilizing systems of power and oppression. Feminist theory will be discussed here as a theory with a lower case ‘t’, however this is not meant to imply that it is not a Theory or cannot be used as one, only to acknowledge that for some it may be a sub-genre of Critical Theory, while for others it stands alone. According to Egbert and Sanden (2020), some scholars see critical paradigms as extensions of the interpretivist, but there is also an emphasis on oppression and lived experience grounded in subjectivist epistemology.

The purpose of using a feminist lens is to enable the discovery of how people interact within systems and possibly offer solutions to confront and eradicate oppressive systems and structures. Feminist theory considers the lived experience of any person/people, not just women, with an emphasis on oppression. While there may not be a consensus on where feminist theory fits as a theory or paradigm, disruption of oppression is a core tenant of feminist work. As hooks (2000) states, “Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. I liked this definition because it does not imply that men were the enemy” (p. viii).

Previous Studies

Marxism and socialism are key components in the heritage.of feminist theory. The origins of feminist theory can be found in the 18th century with growth in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ equality movements. According to Burton (2014), feminist theory has its roots in Marxism but specifically looks to Engles’ (1884) work as one possible starting point. Burton (2014) notes that, “Origin of the Family and commentaries on it were central texts to the feminist movement in its early years because of the felt need to understand the origins and subsequent development of the subordination of the female sex” (p. 2). Work in feminist theory, including research regarding gender equality, is ongoing.

Gender equality continues to be an issue today, and research into gender equality in education is still moving feminist theory forward. For example, Pincock’s (2017) study discusses the impact of repressive norms on the education of girls in Tanzania. The author states that, “…considerations of what empowerment looks like in relation to one’s sexuality are particularly important in relation to schooling for teenage girls as a route to expanding their agency” (p. 909). This consideration can be extended to any oppressed group within an educational setting and is not an area of inquiry relegated to the oppression of only female students. For example, non-binary students face oppression within educational systems and even male students can face barriers, and students are often still led towards what are considered “gender appropriate” studies. This creates a system of oppression that requires active work to disrupt.

Looking at representation in the literature used in education is another area of inquiry in feminist research. For example, Earles (2017) focused on physical educational settings to explore relationships “between gendered literary characters and stories and the normative and marginal responses produced by children” (p. 369). In this research, Earles found evidence to support that a contradiction between the literature and children’s lived experiences exists. The author suggests that educators can help to continue the reduction of oppressive gender norms through careful selection of literature and spaces to allow learners opportunities for appropriate discussions about these inconsistencies.

In another study, Mackie (1999) explored incorporating feminist theory into evaluation research. Mackie was evaluating curriculum created for English language learners that recognized the dual realities of some students, also known as the intersectionality of identity, and concluded that this recognition empowered students. Mackie noted that valuing experience and identity created a potential for change on an individual and community level and “Feminist and other types of critical teaching and research provide needed balance to TESL and applied linguistics” (p. 571).Further, Bierema and Cseh (2003) used a feminist research framework to examine previously ignored structural inequalities that affect the lives of women working in the field of human resources.

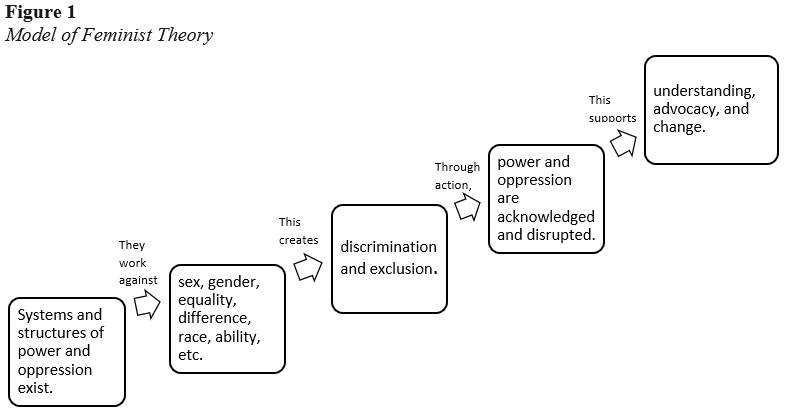

Model of Feminist Theory

Figure 1 presents a model of feminist theory that begins with the belief that systems exist that oppress and work against individuals. The model then shows that oppression is based on intersecting identities that can create discrimination and exclusion. The model indicates the idea that, through knowledge and action, oppressive systems can be disrupted to support change and understanding.

The core concepts in feminist theory are sex, gender, race, discrimination, equality, difference, and choice. There are systems and structures in place that work against individuals based on these qualities and against equality and equity. Research in critical paradigms requires the belief that, through the exploration of these existing conditions in the current social order, truths can be revealed. More important, however, this exploration can simultaneously build awareness of oppressive systems and create spaces for diverse voices to speak for themselves (Egbert & Sanden, 2019).

Constructs

Feminism is concerned with the constructs of intersectionality, dimensions of social life, social inequality, and social transformation. Through feminist research, lasting contributions have been made to understanding the complexities and changes in the gendered division of labor. Men and women should be politically, economically, and socially equal and this theory does not subscribe to differences or similarities between men, nor does it refer to excluding men or only furthering women’s causes. Feminist theory works to support change and understanding through acknowledging and disrupting power and oppression.

Proposition

Feminist theory proposes that when power and oppression are acknowledged and disrupted, understanding, advocacy, and change can occur.

Using the Model

There are many potential ways to utilize this model in research and practice. First, teachers and students can consider what systems of power exist in their classroom, school, or district. They can question how these systems are working to create discrimination and exclusion. By considering existing social structures, they can acknowledge barriers and issues inherit to the system. Once these issues are acknowledged, they can be disrupted so that change and understanding can begin. This may manifest, for example, as considering how past colonialism has oppressed learners of English as a second or foreign language.

The use of feminist theory in the classroom can ensure that the classroom is created, in advance, to consider barriers to learning faced by learners due to sex, gender, difference, race, or ability. This can help to reduce oppression created by systemic issues. In the case of the English language classroom, learners may be facing oppression based on their native language or country of origin. Facing these barriers in and out of the classroom can affect learners’ access to education. Considering these barriers in planning and including efforts to mitigate the issues and barriers faced by learners is a use of feminist theory.

Feminist research is interested in disrupting systems of oppression or barriers created from these systems with a goal of creating change. All research can include feminist theory when the research adds to efforts to work against and advocate to eliminate the power and oppression that exists within systems or structures that, in particular, oppress women. An examination of education in general could be useful since education is a field typically dominated by women; however, women are not often in leadership roles in the field. In the same way, using feminist theory for an examination into the lack of people of color and male teachers represented in education might also be useful. Action research is another area that can use feminist theory. Action research is often conducted in the pursuit of establishing changes that are discovered during a project. Feminism and action research are both concerned with creating change, which makes them a natural pairing.

Pre-existing beliefs about what feminism means can make including it in classroom practice or research challenging. Understanding that feminism is about reducing oppression for everyone and sharing that definition can reduce this challenge. hooks (2000) said that, “A male who has divested of male privilege, who has embraced feminist politics, is a worthy comrade in struggle, in no way a threat to feminism, whereas a female who remains wedded to sexist thinking and behavior infiltrating feminist movement is a dangerous threat”(p. 12). As Angela Davis noted during a speech at Western Washington University in 2017, “Everything is a feminist issue.” Feminist theory is about questioning existing structures and whether they are creating barriers for anyone. An interest in the reduction of barriers is feminist. Anyone can believe in the need to eliminate oppression and work as teachers or researchers to actively to disrupt systems of oppression.

Bierema, L. L., & Cseh, M. (2003). Evaluating AHRD research using a feminist research framework. Human Resource Development Quarterly , 14 (1), 5–26.

Burton, C. (2014). Subordination: Feminism and social theory . Routledge.

Earles, J. (2017). Reading gender: A feminist, queer approach to children’s literature and children’s discursive agency. Gender and Education, 29 (3), 369–388.

Egbert, J., & Sanden, S. (2019). Foundations of education research: Understanding theoretical components . Taylor & Francis.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics . South End Press.

Mackie, A. (1999). Possibilities for feminism in ESL education and research. TESOL Quarterly, 33 (3), 566-573.

Pincock, K. (2018). School, sexuality and problematic girlhoods: Reframing ‘empowerment’ discourse. Third World Quarterly, 39 (5), 906-919.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Feminist Theory and Research on Family Relationships: Pluralism and Complexity

- Original Article

- Published: 07 August 2015

- Volume 73 , pages 93–99, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Katherine R. Allen 1 &

- Ana L. Jaramillo-Sierra 2

9603 Accesses

40 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Feminist perspectives on family relationships begin with the critique of the idealized template of the White, middle class, heterosexually married couple and their dependent children. Feminist scholars take family diversity and complexity as their starting point, by emphasizing how power infuses all of family relationships, from the local to the global scale. As the main location for caring and productive labor, families are the primary unit for providing gendered socialization and distributing power across the generations. In this issue and two subsequent issues of Sex Roles , we have collected theoretical and empirical articles that include critical analyses, case studies, quantitative studies, and qualitative studies that focus on a wide array of substantive topics in the examination of families. These topics include variations in marital and intimate partnerships and dissolution; motherhood and fatherhood in relation to ideology and practice; intergenerational parent–child relationships and socialization practices; and paid and unpaid labor. All of the articles across the three issues are guided by a type of feminist theory (e.g., gender theory; intersectional theory; Black feminist theory; globalization theory; queer theory) and many incorporate multiple theoretical perspectives, including mainstream social and behavioral science theories. Another feature of the collection is the authors’ insistence on conducting research that makes a difference in the lives of the individuals and families they study, thereby generating a wealth of practical strategies for relevant future research and empowering social change. In this introduction, we specifically address the first six articles in the special collection on feminist perspectives on family relationships.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Impact of Financial Hardship on Single Parents: An Exploration of the Journey From Social Distress to Seeking Help

Rebecca Jayne Stack & Alex Meredith

Gender as a Social Structure

The New Roles of Men and Women and Implications for Families and Societies

Acker, J., Barry, K., & Esseveld, J. (1983). Objectivity and truth: Problems in doing feminist research. Women’s Studies International Forum, 6 , 423–435. doi: 10.1016/0277-5395(83)90035-3 .

Article Google Scholar

Allen, K. R. (2000). A conscious and inclusive family studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62 , 4–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00004.x .

Allen, K. R., Walker, A. J., & McCann, B. R. (2013). Feminism and families. In G. W. Peterson & K. R. Bush (Eds.), Handbook of marriage and the family (3rd ed., pp. 139–158). New York: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Allen, K. R., Lloyd, S. A., & Few, A. L. (2009). Reclaiming feminist theory, methods, and practice for family studies. In S. A. Lloyd, A. L. Few, & K. R. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of feminist family studies (pp. 3–17). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Baber, K. M. (2004). Building bridges: Feminist research, theory, and practice: A response to Janet Saltzman Chafetz. Journal of Family Issues, 25 , 978–983. doi: 10.1177/0192513x04267100 .

Baber, K. M., & Allen, K. R. (1992). Women & families: Feminist reconstructions . New York: Guilford.

Google Scholar

Bjork-James, S. (2015). Feminist ethnography in cyberspace: Imagining families in the cloud. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0507-8 .

Chafetz, J. S. (2004). Bridging feminist theory and research methodology. Journal of Family Issues, 25 , 963–977. doi: 10.1177/0192513x04267098 .

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment . Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Coontz, S. (2015). Revolution in intimate life and relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7 , 5–12. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12061 .

Crawford, M., & Kimmel, E. (1999). Promoting methodological diversity in feminist research. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23 , 1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00337.x .

Curran, M. A., McDaniel, B. T., Pollitt, A. M., & Totenhagen, C. J. (2015). Gender, emotion work, and relationship quality: A daily diary study. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0495-8 .

De Reus, L., Few, A. L., & Blume, L. B. (2005). Multicultural and critical race feminisms: Theorizing families in the third wave. In V. L. Bengtson, A. C. Acock, K. R. Allen, P. Dilworth-Anderson, & D. M. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 447–468). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dill, B. T., McLaughlin, A. E., & Nieves, A. D. (2007). Future directions of feminist research: Intersectionality. In S. N. Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (pp. 629–637). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

England, P. (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender and Society, 24 , 149–166. doi: 10.1177/0891243210361475 .

Ferree, M. M. (1990). Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52 , 866–884. doi: 10.2307/353307 .

Ferree, M. M. (2010). Filling the glass: Gender perspectives on families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72 , 420–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00711.x .

Few, A. L. (2007). Integrating black consciousness and critical race feminism into family studies research. Journal of Family Issues, 28 , 452–473. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06297330 .

Few-Demo, A. L. (2014). Intersectionality as the “new” critical approach in feminist family studies: Evolving racial/ethnic feminisms and critical race theories. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6 , 169–183. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12039 .

Few-Demo, A. L., Lloyd, S. A., & Allen, K. R. (2014). It’s all about power: Integrating feminist family studies and family communication. Journal of Family Communication, 14 , 85–94. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2013.864295 .

Freedman, E. B. (2002). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women . New York: Ballantine.

Fulcher, M., Dinella, L. M., & Weisgram, E. S. (2015). Constructing a feminist reorganization of the heterosexual breadwinner/caregiver family model: College students’ plans for their own future families. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0487-8 .

Gergen, M. (2001). Feminist reconstructions in psychology: Narrative, gender, and performance . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Goldberg, A. E., & Allen, K. R. (2015). Communicating qualitative research: Some practical guideposts for scholars. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77 , 3–22. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12153 .

Goldberg, A. E., Moyer, A. M., Black, K., & Henry, A. (2014). Lesbian and heterosexual adoptive mothers’ experiences of relationship dissolution. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0432-2 .

Harding, S. (1998). Is science multicultural?: Postcolonialisms, feminisms, and epistemologies . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hermann, A. C., & Stewart, A. J. (Eds.). (1994). Theorizing feminism: Parallel trends in the humanities and social sciences . Boulder: Westview Press.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Piatelli, D. (2007). Holistic reflexivity: The feminist practice of reflexivity. In S. N. Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (pp. 493–514). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Jacobs, J., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Krieger, S. (1996). The family silver: Essays on relationships among women . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lather, P. (1991). Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern . New York: Routledge.

Mahalingam, R., Balan, S., & Molina, K. M. (2009). Transnational intersectionality: A critical framework for theorizing motherhood. In S. A. Lloyd, A. L. Few, & K. R. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of feminist family studies (pp. 69–80). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mahler, S. J., Chaudhuri, M., & Patil, V. (2015). Scaling intersectionality: Advancing feminist analysis of transnational families. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/211199-015-0506-9 .

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30 , 1771–1800. doi: 10.1086/426800 .

Osmond, M. W., & Thorne, B. (1993). Feminist theories: The social construction of gender in families. In V. L. Bengtson, A. C. Acock, K. R. Allen, P. Dilworth-Anderson, & D. M. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 591–623). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Patil, V. (2013). From patriarchy to intersectionality: A transnational feminist assessment of how far we’ve really come. Signs, 38 , 847–867. doi: 10.1086/669560 .

Risman, B. J. (2004). Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender and Society, 18 , 429–450. doi: 10.1177/0891243204265349 .

Shields, S. A. (2010). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles, 59 , 301–311. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8 .

Smith, D. E. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology . Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Smith, D. E. (1993). The Standard North American Family: SNAF as an ideological code. Journal of Family Issues, 14 , 50–65. doi: 10.1177/0192513x93014001005 .

Sprague, J. (2005). Feminist methodologies for critical researchers: Bridging differences . Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Stanley, L. (1990). Feminist praxis and the academic mode of production: An editorial introduction. In L. Stanley (Ed.), Feminist praxis: Research, theory and epistemology in feminist sociology (pp. 3–19). London: Routledge.

Tasker, F., & Delvoye, M. (2015). Moving out of the shadows: Accomplishing bisexual motherhood. Sex Roles . doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0503-z .

Thompson, L., & Walker, A. J. (1995). The place of feminism in family studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57 , 847–865. doi: 10.2307/353407 .

Thorne, B. (1982). Feminist rethinking of the family: An overview. In B. Thorne & M. Yalom (Eds.), Rethinking the family: Some feminist questions (pp. 1–24). New York: Longman.

Tronto, J. (2006). Moral perspectives: Gender, ethnics, and political theory. In K. Davis, M. Evans, & J. Lorber (Eds.), Handbook of gender and women’s studies (pp. 417–434). London: Sage.

Walker, A. J. (1999). Gender and family relationships. In M. Sussman, S. K. Steinmetz, & G. W. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of marriage and the family (2nd ed., pp. 439–474). New York: Plenum Press.

Walker, A. J. (2000). Refracted knowledge: Viewing families through the prism of social science. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62 , 595–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00595.x .

Walker, A. J. (2009). A feminist critique of family studies. In S. A. Lloyd, A. L. Few, & K. R. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of feminist family studies (pp. 19–27). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Wills, J., & Risman, B. (2006). The visibility of feminist thought in family studies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68 , 690–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00283.x .

Wise, S., & Stanley, L. (2006). Having it all: Feminist fractured foundationalism. In K. Davis, M. Evans, & J. Lorber (Eds.), Handbook of gender and women’s studies (pp. 435–456). London: Sage.

Yllo, K., & Bograd, M. (Eds.). (1988). Feminist perspectives on wife abuse . Newbury Park: Sage.

Download references

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This article complies with ethical standards of the American Psychological Association.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Human Development, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, 24061, USA

Katherine R. Allen

Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia

Ana L. Jaramillo-Sierra

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katherine R. Allen .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Allen, K.R., Jaramillo-Sierra, A.L. Feminist Theory and Research on Family Relationships: Pluralism and Complexity. Sex Roles 73 , 93–99 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0527-4

Download citation

Published : 07 August 2015

Issue Date : August 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0527-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Family relationships

- Feminist research

- Feminist theory

- Intersectionality

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ova-looking feminist theory: a call for consideration within health professions education and research

1 School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

M. E. L. Brown

2 Medical Education Innovation and Research Centre, Imperial College London, London, UK

The role of feminist theory in health professions education is often ‘ova-looked’. Gender is one cause of healthcare inequalities within contemporary medicine. Shockingly, according to the World Health Organisation, no European member state has achieved full gender equity in regard to health outcomes. Further, contemporary curricula have not evolved to reflect the realities of a diverse society that remains riddled with inequity. This paper outlines the history of feminist theory, and applies it to health professions education research and teaching, in order to advocate for its continued relevance within contemporary healthcare.

Introduction

This paper outlines the history of feminist theory, and applies it to health professions education research and teaching, to advocate for its continued relevance within contemporary healthcare. Sharma presented an overview of feminist theory in a 2019 publication. In this paper we consider the history in order to take a deeper dive into several feminist theories, each selected purposively from a different ‘wave’ of feminism and contextualise them within health professions education. We consider pertinent literature in order to offer practical implications and demonstrate the value added for our field. The theories presented are not exhaustive. Rather, we have selected those that offer a new lens through which to consider our field, with some choices informed by our own experiences as medical educators, and others to reflect the spectrum of health professions education research, scholarship, and teaching. We have highlighted areas where future work is warranted within our discipline. In particular, we noted absence, as defined by Paton and colleagues ( 2020 ) as: absence of content, absence of research, and absence of evidence. However, where we see a gap, others may see different absences, or perhaps across different domains of our field such as within a curricular space as opposed to research. As Malorie Blackman said, “ Reading is an exercise in empathy; an exercise in walking in someone else’s shoes for a while. (Blackman, 2021 )” Thus, we urge readers to continue their journey and discover the implications of feminist theory for themselves and the students, educators, and patients who they accompany along the road.

What is feminism?

A critique often advanced against feminist scholars is that they are unable, or unwilling (Thompson, 2001 ) to offer a clear, or simple answer to the question ‘What is feminism?’, or ‘What is feminist theory’ (Smelser and Baltes, 2001 ). Feminist theory represents a diverse range of concepts, theories and principles. Maggie Humm ( 2015 ) has variously described feminism as ‘equal rights for women’, ‘the ideology of women’s liberation’, as ‘the theory of the woman’s point of view’, and ‘fundamentally about women’s experience’(Thompson, 2001 ). It is this multiplicity that makes feminism such an important and flexible topic, but frustrating or alienating for others. As a field rooted in positivist and postpositivist ways of thinking which maintain the existence of a singular, objective reality, the inability to succinctly summarise feminism as one, neat way of viewing the world is liable to criticism from some. Yet, the diverse range of theories captured within the umbrella of feminism offers a flexibility to approaching educational or research questions that can more readily expose and remedy gender inequities. Whilst we cannot claim to offer a definitive and enduring answer to the broad question of ‘What is feminism’, this paper aims to highlight the core features which span several feminist approaches to education and research, applying these ideas to the field of health professions education to explore ways in which the feminist agenda could be advanced in practice.

Why should health professions educators care about feminism?

Gender is one cause of healthcare inequalities within contemporary medicine. Shockingly, according to the World Health Organisation (2020), no European member state has achieved full gender equity in regard to health outcomes. Within the UK alone, it is estimated that there are two preventable gender gap-related deaths per day (Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists., 2019 ). Gender inequality affects the working lives of women, too. Indeed, recent evidence demonstrates that women are still not treated equally within health professions education, from students (Brown et al., 2020 ) across the career trajectory (Finn and Morgan, 2020 ). For a field responsible for training tomorrow’s clinicians, who will go on to hold great power to influence health-related inequalities, a lack of gender equality within the educational and research domains of our field should be of supreme concern. Yet, far too often, gender equity is dismissed as a women’s issue, and feminism as a position of the fervent, and extreme. The stigma associated with identifying oneself as a feminist has stalled the critical evaluation of the long-accepted systems and structures in place in many academic fields which is necessary to advance the cause of justice and equality for women. Health professions education, unfortunately, is no exception. So commonplace is the inequity and discrimination faced by women, the British Medical Journal published a lexicon of terms used in association with women and gender bias. Examples include ova-looked, femi-nazi, mansplaining and repriwomand (Choo and DeMayo, 2018 ).

Some argue that we are now in the ‘post-feminism’ era, characterised by the perception that feminism is either over, or no longer relevant (Leavy and Harris, 2018 ). We disagree – while healthcare services have undergone a renaissance, with greater awareness of sex, gender, and associated health inequalities, health professions curricula have not kept pace (Finn et al., 2021 ). Though feminism and feminist theory have evolved and increasingly consider individuals holistically, and as embedded in iniquitous social structures, there is more work to be done to advance feminist thinking and advocacy in our field.

Firstly, inequality pervades the career paths of health professions educators, and of medics. The struggles faced by women in workforces are well documented (Williams, 2005 ; Williams et al., 2006 ; Williams and Dempsey, 2014 ), and health professions education is no exception (Varpio et al., 2020a ; Brown et al., 2020 ; Finn and Morgan, 2020 ). As with the aforementioned lexicon of gender biases (Choo and DeMayo, 2018 ), a plethora of metaphors pertaining to the differential experiences of women’s career trajectories exist, further evidencing the inequity of experience. The most common metaphors include the sticky floor, the glass ceiling, and the labyrinth (Tesch et al., 1995 ; Yap and Konrad, 2009 ; Kark and Eagly, 2010 ). Within health professions education, Varpio and colleagues ( 2020a ) described the arduous path for women in achieving their professorial positions, when compared to men. Maternal status was cited as impacting upon the careers of the participants in Varpio’s study, further supported by explicit examples of maternal wall bias within studies by Finn ( 2020 ) and Brown (2020). So ingrained and systemic is the inequity, that within the United Kingdom, initiatives such as Athena SWAN have been developed. Athena SWAN is a charter recognises good practices in higher education and research institutions towards the advancement of gender equality, and, more recently, towards broader equality for marginalised groups (Ovseiko et al., 2017 ).

Given that education lays the foundational building blocks for future physicians’ and educators’ attitudes and perceptions, health professions curricula are ripe for feminist change. Even in 2021, curricula, organisational culture, physical education environments remain binary in regard to gender. Dualistic thinking prevails, where the underlying assumptions of an education or healthcare system comprised of only two contrasting, mutually exclusive choices or realities remain the accepted reality. Recent studies (Brown et al., 2020 ; Finn and Morgan., 2020) reported that both medical students and faculty were recipients of tacit gender bias messaging from their physical environments. Such messages served to manifest organisational values regarding who is most welcome, again presenting a gendered message through imagery, for example, that remains ‘too male, too pale…too stale’. Further, within curricula, marginalised groups, for example the LGBTQIA + community, are underrepresented; this poses the risk of potentially perpetuating the well-documented health inequalities experienced by LGBTQIA + individuals and their community (Finn et al., 2021 ). Sex and gender are often conflated, with many curricula failing to integrate these issues into their teaching and learning. Sex and gender are fundamental principles for healthcare given that differences exist between them with respect to the manifestation and prevalence of many conditions and diseases (Finn et al., 2022 ) (Miller et al., 2012 ). Failure to differentiate between sex and gender has been highlighted as problematic in curriculum design, particularly within anatomy (Lazarus & Sanchez., 2021).

Additionally, as gendered inequities in healthcare continue globally, including in women’s health and reproductive decision making, awareness of feminist theory is pivotal in engaging students in meaningful discourse with regard to social determinants of health. It is the duty of healthcare educators to ensure that students are aware that the ‘gender relations of power constitute the root causes of gender inequality and are among the most influential of the social determinants of health’ (Sen and Östlin, 2008 .)

Contemporary health professions education, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, provides further evidence of the gendered inequity within global healthcare systems and further challenges the notion that feminism is no longer relevant. The differential impact of the pandemic on men and women has been well documented (Fortier, 2020 ; Ewing-Nelson, 2020 ; Froldi and Dorigo, 2020 ), in terms of the socio-economic hardships, gendered-divisions of labour and wellbeing. The clinical academic workforce, namely the educators doing the teaching and research, are one group where differential impacts have been frequently reported (Finn and Morgan, 2020 ). Finally, the disease itself has notable risk factors associated with worse outcomes for patients including protected characteristics 1 such as older age and male gender (Froldi and Dorigo, 2020 ), further evidencing the need for gender theory within curriculum design.

Gendered assumptions are documented as stagnating consultations with patients, particularly heteronormative assumptions (e.g., by negatively influencing rapport or preventing health seeking behaviours for sexual health issues) (Finn et al., 2021 ; Laughey et al., 2018 ; Finn et al., 2022 ). It is worth noting the typical manifestation of heteronormativity within curricula, as well as the curricula presentation of sex and gender (Lazarus and Sanchez, 2021 ). Feminist theory is crucial in challenging the gendered nature of curricula. Whitehead et al. ( 2012 ), advocate for recognition of the importance of theory-informed curricula. While caution must be paid to claiming that curricula can fix health inequalities, thus ‘diverting attention from structural social inequities’. Hubris has been cited as having led to such claims, and warnings issued that to make such claims that curricula can transform trainees or healthcare systems is arrogant (Whitehead et al., 2012 ). While it may be somewhat of a leap, tackling health inequalities must start somewhere and perhaps the classroom is no worse than any other place – the future healthcare workforce are also our future policy makers, after all.

What is feminist theory?