History Cooperative

The Evolution, Growth, and History of Human Rights

The history of human rights isn’t that simple. The concept has been around for eons, really, but inalienable rights are only a recent development. Just how recent? Well, the legal recognition of human rights within the international community wasn’t until the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Even still, the moral principles that constitute our fundamental rights are rich in history. Global leaders and government officials in 1948 didn’t just wake up one day thinking, “Wow, the last six years sucked for humanity, we need to do something about it.” No, the steps towards securing mankind’s fundamental freedoms have been growing over generations.

Everything grows from something. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Violence begets violence; hate begets hate; and toughness begets a greater toughness.” What is put out into the world comes back to us tenfold. That being said, why not have love beget love; empathy beget empathy; and respect begets greater respect?

Table of Contents

The History of Human Rights: What are Human Rights?

The history of human rights is a complex and evolving narrative that spans centuries and is deeply intertwined with the development of societies, cultures, and philosophical thought.

Human rights are the collective rights of everyone. Every member of the “human family” is entitled to several fundamental freedoms and rights. This includes – but is not limited to – multiple civil and political rights, economic, social, and cultural rights, and environmental rights. In short, human rights can best be described as the most basic rights of mankind.

The United Nations describes human rights as the “rights inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status.” Therefore, human rights are both universal and undeniable. It doesn’t matter who you are or where you are from. In the eyes of the United Nations, you have rights that are worth protecting and enforcing.

Everybody has human rights: you, your grandma, and your weird neighbor included. It is the preservation and implementation of these rights on such a massive, international scale when things get tricky.

Types of Human Rights

There are a handful of human rights. There are five “themes” of human rights that the rest fall beneath.

Types of human rights include…

- Economic rights

- Social rights

- Political rights

- Civil rights

- Cultural rights

These five themes of human rights encapsulate the collective rights of humanity. Though they may not be much to look at at a glance, there is a lot to them. Each theme can be broken down into countless categories and sub-categories. As the years have gone on, the list of human rights only grew (albeit slowly).

Violations of Human Rights

There is not a person on this earth that can be denied their rights as a human being. Right? Unfortunately, that is where things can get complicated.

It is painful to admit, but human rights are a new thing. They may have entertained the thoughts of rulers of ages past, or been explored through the eyes of philosophers many years ago; however, the fundamental rights of mankind have only been established within the last hundred years.

You would think it would be a no-brainer to treat folk with inherent dignity. However, when push comes to shove (or in times of strife), it is easy to lose sight of who we are and what we stand for. War, economic collapses, and ecological and natural disasters can all become a slippery slope into human rights abuses.

As human beings, we are born with rights that supersede state, country, or creed. When these rights are violated – oftentimes in the name of governance, extremism, and war – it is up to everyone to hold offenders accountable. Notably, the government is charged with holding itself accountable as well which…can get complicated if the government is acting in its own self-interest. That is where the international community comes into play.

A History of Human Rights: 539 BC to the 21st-Century

Human rights aren’t new, but their legality is. Such is especially true for universal human rights, which were only adopted in 1948 after one of history’s bloodiest wars. Since then, only limited progress has been made toward expanding, respecting, and enforcing human rights.

Much of the time, the evolution of human rights can be described by generations. The first-generation rights (civil and political rights) are theorized to have begun in the 17th- and 18th centuries. Pretty much, people should have a say in what policies will affect them. These rights also offer protections against violations of state.

Second-generation rights focus more on the social, economic, and cultural rights of individuals. How people live and work together became a hot topic during the Industrial Revolution and the burgeoning working class. On the other hand, third-generation rights are known as solidarity rights. These would include the right to a healthy environment and the right to peace among other things.

539 BCE – Cyrus the Great and Basic Freedoms

Cyrus the Great was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, which stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River. Cyrus was also a phenomenal military strategist; all of this, however, was not necessarily what made Cyrus…well, great .

What defined the reign of Cyrus more than anything was his treatment of the lands he conquered. He respected the cultures, religions, and customs of the many, many lands he inducted into his growing empire. There was no forced assimilation, no denouncing of local religions, and an emphasis was placed on tolerance. Today, Cyrus is viewed as a benevolent leader who championed religious minorities in conquered regions.

Part of why Cyrus has such a sparkling interpretation is the Cyrus Cylinder . The cylinder acts as a record of Cyrus’ 539 BCE conquest of ancient Babylon. Apparently, upon arriving in Babylon, Cyrus the Great declared himself chosen by Marduk, the chief city god . Doing such made him positively stand out compared to the king he had deposed.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

The king, Nabonidus, turned out to be in the middle of an (unpopular) religious reformation with the moon god Sîn at its helm. Despite such reformations taking place successfully in the past, Marduk was a popular god amongst the ancient Babylonians. Cyrus’ open worship of the revered deity had him quickly gain traction with common and high-born Babylonians alike.

Later interpretations of the Cyrus Cylinder suggest that Cyrus freed Babylonian slaves, although slavery was continued throughout Achaemeniad rulership. The historicity of this event is debated, though supported in the Book of Ezra which states that Cyrus ended the Babylonian exile. Whatever the true interpretation of the Cyrus Cylinder, Cyrus is still credited with being the first to establish basic freedoms.

1215 – The Magna Carta and Rule of Law

Ancient leaders afforded their subjects certain rights. Though no international bill, the running of ancient empires and societies – and what they viewed as human rights – is nothing to scoff at. Many rulers (good ones at least) did acknowledge the legal obligation that came with leading. That being said, Magna Carta, anyone?

The signing of the Magna Carta is one of the most famous stories in history. After all, it was the first significant record of the rule of law. The Magna Carta (also called “The Great Charter”) establishes that the monarch and their government are not above the law. While it didn’t necessarily propel human rights forward, the Magna Carta was a big deal.

It wasn’t peasants that forced King John’s hand, but rather feudal lords – barons, in this case – that threatened civil war. They were angry about the rise in taxes to fund bitterly unsuccessful wars in France. The tax spike was viewed as a clear exploitation of power by the king. Therefore, to avoid royal infringement on their finances, the barons grouped up and made a heavy-handed threat to the monarch.

Though the Magna Carta was signed, King John did later reach out to the Pope to negate the document’s legal status. You know, looking for any loophole out of a binding agreement…just as someone looking to exploit their power would. Anyways, doing so led to England ’s First Barons’ War, which lasted two years.

READ MORE: The Kings and Queens of England: English Monarchs Timeline from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II

1625 – Hugo Grotius and International Law

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) is considered the father of international law. So, you’ve probably guessed it: the consensus is that Grotius laid the foundations of modern international law. He was a Dutch juror, a poet, and a massive fan of Greek and Roman philosophy.

In the groundbreaking novel On the Laws of War and Peace (1625), Grotius boldly attempts to find a middle ground between natural law and the laws of nations. Accordingly, the most-favored idealist view is counteractive, but absolute realism is also unacceptable. Wars will happen, but the standard of warfare is determined by international law; likewise, the treatment of minorities is up to review from the international stage. Grotian tradition “views international policies as taking place within an international society” according to A. Claire Cutler in Review of International Studies .

Grotius, therefore, establishes that there are certain human rights that are unwaveringly fundamental to human beings. These rights are then vital to understanding human nature. Then, international laws somewhat based on human nature are, to a degree, completely valid.

Much of Grotian tradition and the themes that Grotius had discussed in his lifetime became blueprints for modern international human rights law. He vaunted non-intervention policies but agreed that another country could step in against tyrannical rule on behalf of the citizens. This would be because of human dignity rather than any personal gain.

1689 – English Bill of Rights

The English Bill of Rights is best known as the document that establishes Parliamentary privilege. However, there is a lot more to this piece of parchment than just that! The English Bill of Rights stated that there could be no taxation without representation (in Parliament), freedom from government interference, the right to petition, and equal treatment in the court system. Furthermore, other human rights were granted to civilians, such as no cruel and unusual punishment and the right to free speech.

If that sounds familiar to all of you Americans reading, it’s because it is.

The whole “no taxation without representation” theme was a major point of contention within the British-American colonies leading up to the Revolutionary War. British colonies did not have appropriate representatives in Parliament. Agents, sure, but not sufficient representatives that could challenge the British majority. Additionally, when drafting the United States Bill of Rights , government officials definitely looked to the English Bill of Rights for some inspiration.

As it turns out, the populace wasn’t too keen on giving the a-OK to a fledgling government with no guarantee of personal liberty. They rightfully didn’t want British monarchy 2.0, so not many Anti-Federalists (nay to national governments) were willing to ratify the Constitution. This left Federalists (yay to the national government) in a sticky situation. The Federalists added the Bill of Rights to make the Constitution more appealing to the opposition.

1789 – The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the French Revolution

The French Revolution was a major upheaval of the feudal system in France. It was a crazy time to be alive and the French Revolution left a lot of European monarchies wiping their brow. The American Revolution – a major source of inspiration for French peasantry – ended a mere 6 years before. And, unlike their American counterparts, the French Revolution was thrice as bloody.

When examining the French Revolution, it is crucial to consider what events led up to it. Again, everything grows from something. Right off the bat, some members of society were granted more rights than others. The Estate System effectively shot down an individual’s right to self-determination and grossly limited their economic rights.

Speaking of economic rights, the economy sucked . The two higher Estates (the First and Second) relied on the taxation of the Third Estate for their livelihood. The Third Estate, composed of the working class, could not afford necessities.

If the bread riots in Paris were bad, then the famine rampant throughout the countryside was horrible. Also, absolutism – the idea that the monarchy has complete, unchallenged control over an entire country – didn’t help at all .

So, the people of France began turning to Enlightenment ideals. The Age of Enlightenment, which emphasized the value of individual liberty and religious tolerance, inspired the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The Declaration was drafted by American Revolution veteran Marquis de Lafayette and clergyman Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyes, both of whom ironically belonged to the Second and First Estates.

Article I of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen reads as follows: “Human Beings are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.” Such an open declaration of human rights ignited a spark in many Frenchmen, women, and children who had felt disenfranchised by their system of government.

1791 – The U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights

The end of the Revolutionary War in the United States was a trying period in the nation’s history. No one was quite certain what they wanted when they wiped their hands clean of British rule; they just knew they didn’t want that . Thus, emerged the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists.

The Federalists wanted a national government whereas Anti-Federalists preferred smaller, self-governing states. There was a massive and very real fear that a big government could lead the new country down the same hole they just dug themselves out of.

The United States Constitution was initially introduced to outline the systems of government that the Articles of Confederation (1777) lacked. It was introduced to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Other Convention topics included state representation in Congress, presidential powers, and the slave trade. The main issue with the Constitution is that it focused only on governmental powers and branches, but not the rights of the people.

READ MORE: Slavery in America: United States’ Black Mark

Which is important when you are trying to assert federal control over them. As the Magna Carta taught us (which the French Bourbon dynasty could have learned from) the government is not above the law. The Federalists needed to think of something to reel the Anti-Feds to their side.

This is where the Bill of Rights comes in. Ten amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution, which collectively became known as the Bill of Rights. These amendments, which guarantee the “certain unalienable Rights” of the Declaration of Independence are still a topic of debate today. While 27 more amendments have been added to the original ratification in 1791, only the first 10 are known as the Bill of Rights.

1919 – Peace Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

The events of World War I (WWI) shocked the international community. It was the Great War: the “war to end all wars.” Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case.

READ MORE: What Caused World War 1? Political, Imperialistic, and Nationalistic Factors

World War I was a period of rapid advancements in warfare. Tanks , chemical weaponry, flamethrowers, and machine guns were all developed in the shadow of the very first world war. Furthermore, violations of human rights were plentiful.

In various countries – the United States included – opposition to the war could lead to jail time. Civilians were court-martialed and sent to military prisons for speech deemed “disloyal.” In Canada, the War Measures Act was introduced, giving the federal government power to suspend all rights of citizens. Meanwhile, 100,000 civilians in France and Belgium were detained by German forces, only to be sent against their will as forced labor in Germany.

So, at the end of the war, drafting a peace treaty was only one of the many hurdles that nations had to contend with. The biggest issue is that no one could agree on how to treat Germany and other Central powers. What ended up happening was a significant stripping of territory, a reduction of military forces, and a reparations bill that was astronomical. The peace that came with the Treaty of Versailles was fragile at best.

From the treaty came the League of Nations , founded by the 28th U.S. President, Woodrow Wilson. In all, 63 countries were a part of the League: this was a majority of sovereign nations in 1920. The League of Nations was the first international congregation of nations and was developed to help achieve international peace.

At some point, Japan had introduced a clause to the treaty that – if approved – would’ve established racial equality within the League of Nations. The U.S. and a number of British dominions rejected the amendment. Despite this fumble, the League of Nations managed to develop organizations that did positively propel human rights forward.

International Labor Organization

The International Labor Organization ( ILO ) was founded by the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. It became a mainstay in the later United Nations. As it stands, the International Labor Organization safeguards social and economic rights by setting international labor standards.

Much of the foundation of the ILO is based on 19th-century social and labor movements. These movements brought international attention to the plights of workers. After World War I, the beliefs of these movements became revitalized as the demand for social justice and a higher standard of living for the working classes emerged.

In the wake of WWI, the International Labor Organization proved especially helpful for developing countries. Among these, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Poland all were considered separated from Russian claims per the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The benefit of the ILO would again be proved in developing countries after WWII. Then, numerous countries were freed from colonial rule including India, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

Protection of Minorities

Humanitarian conditions were not a driving principle sought to be upheld by the League of Nations. Instead, the League was formed to maintain the status quo following the Allied victory in World War I ( Justifications of Minority Protections in International Law , 1997). That being said, the legitimate international concern of another world war happening did provide substantial reasoning to address some amount of human rights.

The administrative branch of the League of Nations, the International Secretariat, included a Minorities Section in the early years. The Minorities Section dealt with the protections of minorities in relevant nations, particularly those newly formed in Eastern Europe.

Before the formation of the Secretariat and its Minorities Section, the rights of minorities that found themselves aloft in war-torn Eastern Europe were ambiguous at best. It was the Minorities Section that developed “a procedural and bureaucratic structure that untangled the League’s…mandate…guaranteeing the rights of some twenty-five million racial, religious, and linguistic minorities” as stated by Thomas Smejkal in his thesis, “ Protection in Practice: The Minorities Section of the League of Nations Secretariat, 1919-1934 .” For a time, the Section was somewhat successful at addressing inequalities experienced by minorities. It was not until later that the overall weaknesses of the League – such as lack of representation – proved to be an issue in the face of World War II.

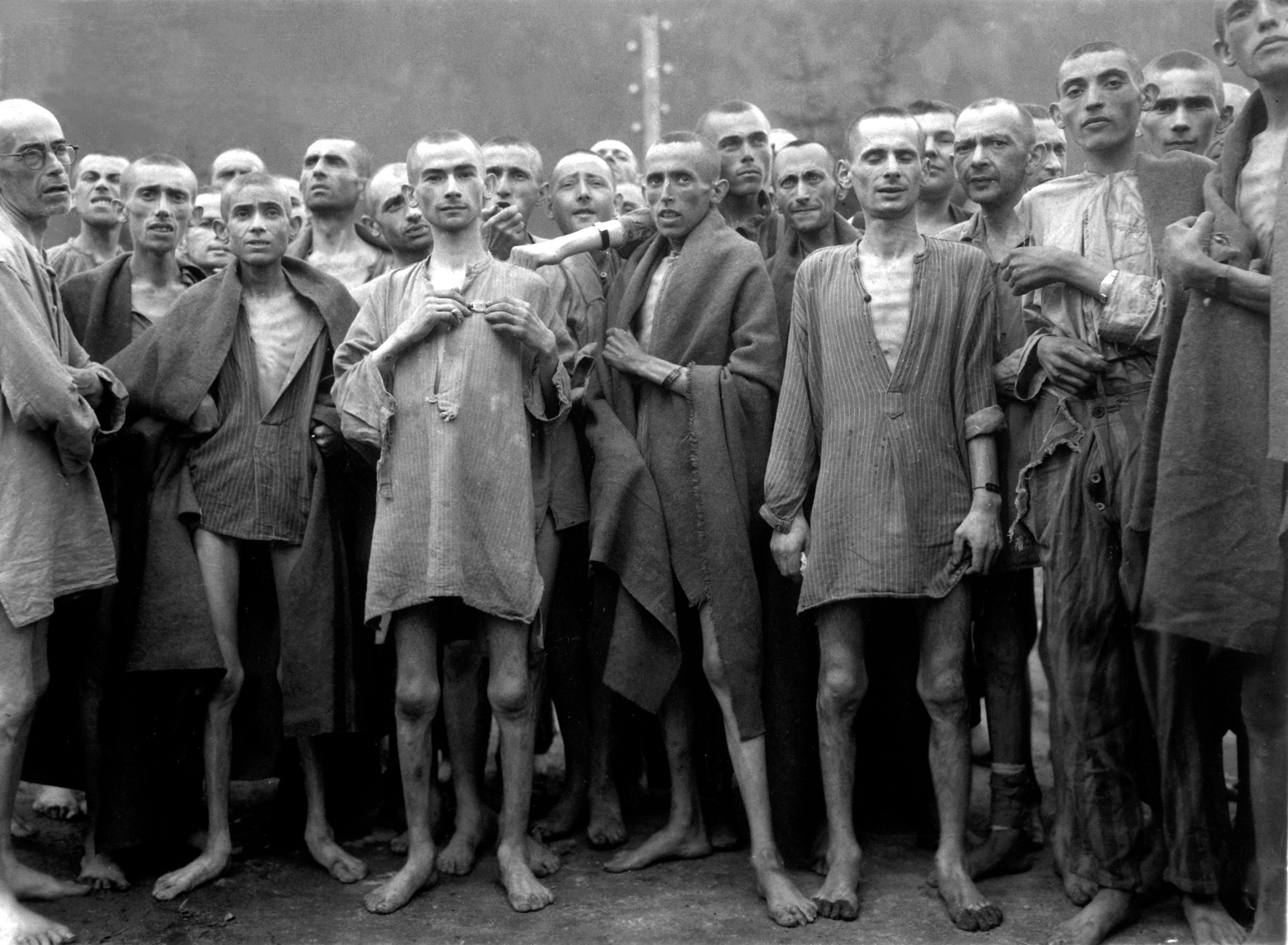

With World War II came numerous human rights abuses, with those hit hardest being certain minority groups in Eastern Europe. Without significant world powers (the United States, Germany, the Soviet Union, Italy, Japan, and Spain) it became increasingly difficult to ensure personal liberty for minorities.

1945 – Post-WWII and the United Nations

World War II, as with the First World War, saw a slew of human rights violations. To be fair, most wars – major and minor – are breeding grounds for such infringements. Supposed “gentlemen wars” are a thing of the past, if not nearer to pure fantasy.

The United Nations was founded in 1945, a month after the end of World War II . To say there was global devastation would be an understatement: roughly 3% of the world’s population died.

Furthermore, a new horror was realized in the later months of 1945. The United States developed and dropped two atomic bombs in the largely civilian-populated cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. The bombing led to the end of the Pacific Theater, with legal experts and scholars still debating whether or not the dual bombings were war crimes.

Though the threat of weapons of mass destruction was real, the United Nations didn’t immediately act against them. It was not until 1968 that the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was signed. Even later still was the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was signed, which didn’t happen until 2017. Currently, the use of weapons of mass destruction is considered a violation of human rights.

After WWII, there was new hope for achieving international peace. The League of Nations, now null and void, was rebranded as the United Nations. In fact, the Charter of the United Nations was signed while World War II was still raging on and the development of the UN began back in 1943 during the pivotal Tehran Conference. During this time, the League of Nations wasn’t completely obsolete, but it was just barely functioning.

The United Nations expanded significantly on human rights and humanitarian laws. Like its predecessor, its primary goal is bolstering international peace.

The United Nations Charter

The United Nations Charter is the founding document of the U.N., signed in 1945. The Charter itself is considered to be an international treaty, legally binding involving countries to oblige by any laws passed. Since its initial signing in 1945, the United Nations Charter has been amended three times.

Commission of Human Rights

One of the more significant creations post-WWII is the Commission of Human Rights . Emerging in 1946, the Commission is responsible for protecting fundamental freedoms. There are numerous themes that the Commission of Human Rights handles.

Anything from the right to self-determination to indigenous issues is discussed by the Commission. Moreover, they look into both human rights violations worldwide and in specific countries. It is the Commission of Human Rights that primarily sets standards for human rights for the international community.

An example is the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The Commission opens the declaration with the recognition “of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world.” Right off the bat, the Commission acknowledges that there are certain fundamental human rights that must be recognized. The inclusion of civil and political rights, and economic, social, and cultural rights, among others, have been later added per the Commission.

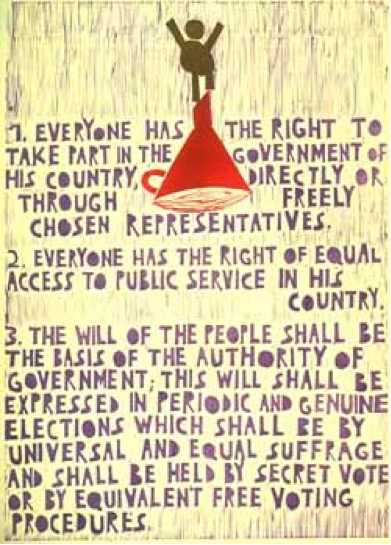

1948 – Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a significant landmark in the history of human rights. It has acted as a model document for several “domestic constitutions, laws, regulations, and policies” according to Hurst Hannum in “ The UDHR in National and International Law ” ( Health and Human Rights , 1998). Despite this, the UDHR is not a legally binding document; at least not in whole. However, the Declaration has been incorporated into most constitutions of the nations belonging to the UN.

All things considered, the UDHR is a customary international law. Everyone understands, acknowledges, and respects the Declaration (at least those 193 states and countries within the United Nations). It was drafted for bolstering international peace, after all.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights essentially acts as a guide to human rights norms. It has alternatively been referred to as the international Magna Carta since it sets a standard for how a government treats its own citizens. Thus, the treatment of a government’s citizens towards its own citizens became everybody ’s business.

Since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been signed, the U.N. has called out numerous governments for their citizen abuses. To be honest, the United Nations is still pointing out government infringements on human rights. One of the most historically significant times the United Nations has done this was during apartheid in South Africa.

In 1962, the U.N. condemned South Africa’s racial discrimination and bigoted laws, even going as far as calling for members to cut economic and military ties with the country. Unfortunately, not many Western countries were willing to end economic relations, even after apartheid became a crime against humanity in 1973.

1949 – International Humanitarian Law

Another international law signed in the aftermath of World War II is the International Humanitarian Law (IHL). These laws are intended to limit the effects of armed conflict and offer protections for those uninvolved in hostilities. Additionally, the IHL puts restrictions on the methods of warfare and the treatment of prisoners of war. Most – if not all – themes of the IHL had been adopted from the four Geneva Conventions of 1949.

Geneva Conventions of 1949

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 prohibit specific abuses during warfare. Three separate protocols have been added to the International Humanitarian Law, two in 1977 and one in 2005 respectively. These supplemental protocols give rights to certain minority groups in times of war.

The first of the Geneva Conventions gives protection to soldiers who are removed from the ongoing conflict. This Convention deals largely with the sick and wounded and the retention of their human rights. Meanwhile, the second Geneva Convention expands on the first, extending rights to naval combatants and ship-bound non-combatants. The second Convention also clarifies that “shipwrecked” includes those who parachute from damaged aircraft (Articles 12 and 18).

The third Geneva Convention sets standards for the treatment of prisoners of war. The Convention emphasizes that POWs are to be treated with basic human dignity. This means that degrading treatment is effectively illegal (as stated in Articles 13, 14, and 16). Also, it clarifies who is considered to be war prisoners.

Members of the armed forces, militia volunteers, and civilians in the company of armed forces are all considered to be prisoners of war. Therefore, the rights of POWs are extended to civilians under certain circumstances. Particularly those civilians involved in resistance movements and non-combatants, such as medics or chaplains, can be viewed as POWs.

The fourth Geneva Convention is an expansion to the rights and treatment of civilians in occupied land or conflict areas. Generally, civilians are to retain their civil and political rights. An example of this is addressed in Article 40, which states that civilians cannot be forced to do military-related work for occupying forces. More importantly, civilians are protected from murder, torture, or brutality; and from discrimination based on race, nationality, religion, or political opinion (Articles 13 and 32).

1954-1976 – The Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights Movements

More was happening in the ’60s than just the musical British Invasion. It was the middle of the Cold War , a “bloodless war,” where the United States and the Soviet Union were at each other’s throats from 1947 to 1991. So much for global peace.

READ MORE: Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy

The two nations got involved in a series of proxy wars, never directly assaulting the other. The most famous of these proxy wars, the Korean War (1950-1954) and the Vietnam War (1955-1975) were unpopular and viewed as “senseless” by the masses. They were only two out of upwards of 11 proxy wars.

During these terribly unpopular wars, the Civil Rights Movement was speeding up in the United States. In truth, it is impossible to argue for being a beacon of democracy if you oppress minorities in your own country. Thus, the Civil Rights era saw a boom in individuals demanding civil and political rights; economic, social, and cultural rights were also at the forefront.

The Civil Rights Movement was largely connected to the generational trauma of Black Americans caused by the horrors of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. As of the ’60s, only very limited progress had been made from the Reconstruction era that followed the Civil War. For generations , an entire demographic of the American population was denied collective rights afforded to them by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights back in 1948.

Other minority groups within (and outside of the United States) took note. Civil Rights inspired a human rights movement among Native Americans, Asian Americans, Mexican Americans, women, and members of the LGBTQ community. Additionally, Northern Ireland was inspired to lead protests against the British occupation of Northern Ireland. These protests led to the Northern Ireland Conflict (the Troubles) and the creation of the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a legally binding international document drafted in 1954. However, the ICCPR was not signed until 1966. It took another decade for it to become effective in 1976.

A ton of stuff happened within those two decades that could have benefitted from such a document, but we digress. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is viewed as an international human rights law. It ensures that those belonging to mankind (i.e. human beings), have certain political rights as citizens and are treated with basic human dignity. Overall, the ICCPR asserts that people are entitled to specific personal liberties that cannot be denied by government entities.

International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

The International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) was another international bill that would have made a huge impact if put into effect the same year it was drafted. The ICESCR was developed alongside the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It was also signed and made effective in the same years as the ICCPR. As its title suggests, the ICESCR is intended to promote economic development, all while providing citizens with social and cultural rights.

Compared to other human rights laws of the past, the International Covenant of Economic Social and Cultural Rights has made significant progress for Indigenous Peoples. The identification of cultural rights specifically as human rights has positively impacted other minority groups as well, including the Roma.

Human Rights in the 21st Century

As the Commission of Human Rights states: “Human rights standards have little value if they are not implemented.” Although there have been countless standards, laws, and treaties passed by the United Nations since World War II, the international community has struggled with implementation. Furthermore, since the perception of human rights is constantly evolving, past acts – slavery, racial discrimination, and nuclear weapons to name a few – are now considered to be human rights violations. While these are all terrible acts (and always have been terrible acts) the argument arises that, at the time of practice, these were not considered to be violations. Do, then, past offenders be treated as such?

The United Nations Human Rights Council has done groundbreaking work at driving the human rights evolution. In that there is no denying. Even still, more work could be done to provide everyone across the globe with equal and inalienable rights.

The internet – a Wild West type of medium – still requires users to uphold human rights; however, it is maintaining human rights in this rapidly evolving environment that’s tricky. Likewise, environmental protections are an extension of the human right to a healthy environment. They are only recent developments.

With everything happening in the world right now, there is legitimate international concern regarding the state of human rights. Only recently has Twitter ’s human rights team been cut from the company. Not to mention the humanitarian crises occurring in parts of Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, South America, and the United States.

Human rights are ever-growing, desperately attempting to keep up with changing times. What has been defined as human rights norms today may always be expanded upon tomorrow.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/history-of-human-rights/ ">The Evolution, Growth, and History of Human Rights</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

International Human Rights Law: A Short History

About the author, frans viljoen.

The phrase "human rights" may be used in an abstract and philosophical sense, either as denoting a special category of moral claim that all humans may invoke or, more pragmatically, as the manifestation of these claims in positive law, for example, as constitutional guarantees to hold Governments accountable under national legal processes. While the first understanding of the phrase may be referred to as "human rights", the second is described herein as "human rights law".

While the origin of "human rights" lies in the nature of the human being itself, as articulated in all the world's major religions and moral philosophy, "human rights law" is a more recent phenomenon that is closely associated with the rise of the liberal democratic State. In such States, majoritarianism legitimizes legislation and the increasingly bureaucratized functioning of the executive. However, majorities sometimes may have little regard for "numerical" minorities, such as sentenced criminals, linguistic or religious groups, non-nationals, indigenous peoples and the socially stigmatized. It therefore becomes necessary to guarantee the existence and rights of numerical minorities, the vulnerable and the powerless. This is done by agreeing on the rules governing society in the form of a constitutionally entrenched and justiciable bill of rights containing basic human rights for all. Through this bill of rights, "human rights law" is created, becoming integral to the legal system and superior to ordinary law and executive action.

In this article, some aspects of the history of human rights law at the global, regional and subregional levels are traced. The focus falls on the recent, rather than the more remote, past. To start with, some observations are made about the "three generations" of human rights law.

Three generations of international human rights law Human rights activism can be described as a struggle to ensure that the gap between human rights and human rights law is narrowed down in order to ensure the full legal recognition and actual realization of human rights. History shows that governments do not generally grant rights willingly but that rights gains are only secured through a successful challenge to absolutist authority. Following on the Magna Carta, which set limits on the powers of royal Government in thirteenth century England, the 1776 American Declaration of Independence and the 1789 French Declaration des droits de l'Homme et de du citoyen (Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen) were landmarks of how revolutionary visions could be transformed into national law and made into justiciable guarantees against future abuse.

The traditional categorization of three generations of human rights, used in both national and international human rights discourse, traces the chronological evolution of human rights as an echo to the cry of the French revolution: Liberté (freedoms, "civil and political" or "first generation" rights), Egalité (equality, "socio-economic" or "second generation" rights), and Fraternité (solidarity, "collective" or "third generation" rights). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the struggle for rights focused on the liberation from authoritarian oppression and the corresponding rights of free speech, association and religion and the right to vote. With the changed view of the State role in an industrializing world, and against the background of growing inequalities, the importance of socio-economic rights became more clearly articulated. With growing globalization and a heightened awareness of overlapping global concerns, especially due to extreme poverty in some parts of the world, "third generation" rights, such as the rights to a healthy environment, to self-determination and to development, have been adopted.

During the period of the cold war, "first generation" rights were prioritized in Western democracies, while second generation rights were resisted as socialist notions. In the developing world, economic growth and development were often regarded as goals able to trump "civil and political" rights. The discrepancy between the two sets of rights was also emphasized: "civil and political" rights were said to be of immediate application, while "second generation" rights were understood to be implemented only in the long term or progressively. Another axis of division was the supposed notion that "first generation" rights place negative obligations on States while "second generation" rights place positive obligations on States. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it became generally accepted that such a dichotomy does not do justice to the extent to which these rights are interrelated and interdependent. The dichotomy of positive/negative obligations no longer holds water. It seems much more useful to regard all rights as interdependent and indivisible, and as potentially entailing a variety of obligations on the State. These obligations may be categorized as the duty to respect, protect, promote and fulfil.

Global level For many centuries, there was no international human rights law regime in place. In fact, international law supported and colluded in many of the worst human rights atrocities, including the Atlantic Slave Trade and colonialism. It was only in the nineteenth century that the international community adopted a treaty abolishing slavery. The first international legal standards were adopted under the auspices of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which was founded in 1919 as part of the Peace Treaty of Versailles. ILO is meant to protect the rights of workers in an ever-industrializing world.

After the First World War, tentative attempts were made to establish a human rights system under the League of Nations. For example, a Minority Committee was established to hear complaints from minorities, and a Mandates Commission was put in place to deal with individual petitions of persons living in mandate territories. However, these attempts had not been very successful and came to an abrupt end when the Second World War erupted. It took the trauma of that war, and in particular Hitler's crude racially-motivated atrocities in the name of national socialism, to cement international consensus in the form of the United Nations as a bulwark against war and for the preservation of peace.

The core system of human rights promotion and protection under the United Nations has a dual basis: the UN Charter, adopted in 1945, and a network of treaties subsequently adopted by UN members. The Charter-based system applies to all 192 UN Member States, while only those States that have ratified or acceded to particular treaties are bound to observe that part of the treaty-based (or conventional) system to which they have explicitly agreed.

Charter-based system This system evolved under the UN Economic and Social Council, which set up the Commission on Human Rights, as mandated by article 68 of the UN Charter. The Commission did not consist of independent experts, but was made up of 54 governmental representatives elected by the Council, irrespective of the human rights record of the States concerned. As a consequence, States earmarked as some of the worst human rights violators served as members of the Commission. The main accomplishment of the Commission was the elaboration and near-universal acceptance of the three major international human rights instruments: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the latter two adopted in 1966. As the adoption of those two separate documents indicates, the initial idea of transforming the Universal Declaration into a single binding instrument was not accomplished, mainly due to a lack of agreement about the justiciability of socio-economic rights. As a result, individual complaints could be lodged, alleging violations by certain States of ICCPR, but not so with ICESCR.

The normative basis of the UN Charter system is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted on 10 December 1948, which has given authoritative content to the vague reference to human rights in the UN Charter. Although it was adopted as a mere declaration, without a binding force, it has subsequently come to be recognized as a universal yardstick of State conduct. Many of its provisions have acquired the status of customary international law.

Faced with allegations of human rights violations, particularly in apartheid South Africa, the Commission had to devise a system for the consideration of complaints. Two mechanisms emerged, the "1235" and "1503" procedures, adopted in 1959 and 1970, respectively, each named after the Economic and Social Council resolution establishing them. Both mechanisms dealt only with situations of gross human rights violations. The difference was that the "1235" procedure entailed a public discussion while "1503" remained confidential. In order to fill the gap in effective implementation of human rights, a number of special procedures were established by the Commission. Unique procedures take the form of special rapporteurs, independent experts or working groups looking at a particular country (country-specific mandate) or focusing on a thematic issue (thematic mandate).

Leapfrogging a few decades to 2005, in his report In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All, the former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, called for the replacement of the Commission by a smaller, permanent and human rights-compliant Council, able to fill the credibility gap left by States that used their Commission membership "to protect themselves against criticism and to criticize others". 1 The major reason for replacing the Commission was the very selective way in which it exercised its country-specific mandate, due mainly to the political bias of representatives and the ability of more powerful countries to deflect the attention away from themselves and those enjoying their support. In 2006, the General Assembly decided to follow the Secretary-General's recommendation, creating the Human Rights Council as a replacement to the Commission on Human Rights. 2

There are some important differences between the former Commission on Human Rights and the current Human Rights Council. As a subsidiary organ of the General Assembly, the Council enjoys an elevated status compared to the Commission, which was a functional body of the Economic and Social Council. It has a slightly smaller membership (47 States) and its members are elected by an absolute majority of the Assembly (97 States). To avoid prolonged dominance by a few States, members may be elected only for two consecutive three-year terms. The Council serves as a standing or permanent body, which meets regularly, not only for annual "politically charged six-week sessions" as the Commission did. Following the more human rights-sensitive selection criteria, the list of States elected by the Assembly contrasts with countries which, in 2006, served on the Commission. The Assembly may, by a two-thirds majority vote, suspend a member that engages in gross and systematic human rights violations.

The Human Rights Council retained most of the special procedures, including the confidential "1503" (now called the "compliant procedure"), and introduced the Universal Peer Review (UPR). Starting in April 2008, one third of UN Member States has undergone this process. The UPR sUPR hows similarities with the African Peer Review Mechanism which has been set up under the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD). Apart from the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the General Assembly adopted numerous other declarations. When sufficient consensus emerges between States, declarations may be transformed into binding agreements. It is revealing that the required level of agreement is lacking on crucial issues, such as the protection of non-hegemonic citizenship. The two relevant declarations -- the Declaration on the Rights of Persons belonging to Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, adopted in 1992, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted in 2007, have not been translated into binding instruments. The same is true of the Declaration on the Right to Development, which was adopted in 1986.

Treaty-based system The treaty-based system developed even more rapidly than the Charter-based system. The first treaty, adopted in 1948, was the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which addressed the most immediate past experience of the Nazi Holocaust. Since then, a huge number of treaties have been adopted, covering a wide array of subjects, eight of them on human rights -- each comprising a treaty monitoring body -- under the auspices of the United Nations.

The first, adopted in 1965, is the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), followed by ICCPR and ICESCR in 1966. The international human rights regime then started to move away from a generic focus, shifting its attention instead to particularly marginalized and oppressed groups or themes: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) adopted in 1979; the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984); the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989); the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (1990); and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006). The latest treaty is the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (ICED), also adopted in 2006 but yet to enter into force. With the adoption of an Optional Protocol to ICESCR in 2008, allowing for individual complaints regarding alleged violations of socio-economic rights, the UN treaty system now also embodies the principle that all rights are justiciable. Office of the UN High Commissioner Twenty years after the adoption of the Universal Declaration, the first International Conference on Human Rights was held in 1968 in Teheran. As the world was at that stage caught in the grip of the cold war, little consensus emerged and not much was achieved. The scene was very different when the second world conference took place in Vienna in 1993. The cold war had come to an end, but the genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina was unfolding. Against this background, 171 Heads of State and Government met and adopted the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. It reaffirmed that all rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent. Several resolutions adopted there were subsequently implemented, including the adoption of an Optional Protocol to CEDAW and the establishment of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, with the first High Commissioner (José Ayala Lasso) elected in 1994. The High Commissioner has the major responsibility for human rights in the United Nations. The increasingly important human rights field presence in ratcheted countries also falls under this Office.

Other conferences have also highlighted important issues, such as racism and xenophobia, which were discussed at the 2001 World Conference Against Racism, held in Durban, South Africa. This culminated in the adoption of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action. A review conference to assess progress in the implementation of the Declaration took place in April 2009.

Regional level Since the Second World War, three regional human rights regimes -- norms and institutions that are accepted as binding by States -- have been established. Each of these systems operates under the auspices of an intergovernmental organization or an international political body. In the case of the European system -- the best of the three -- it is the Council of Europe, which was founded in 1949 by 10 Western European States to promote human rights and the rule of law in post-Second World War Europe, avoided a regression into totalitarianism and served as a bulwark against Communism. The Organization of American States (OAS) was founded in 1948 to promote regional peace, security and development. In Africa, a human rights system was adopted under the auspices of the Organization for African Unity (OAU), which was formed in 1963 and transformed in 2002 into the African Union (AU).

In each of the three systems, the substantive norms are set out in one principal treaty. The Council of Europe adopted its primary human rights treaty in 1950: the European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Incorporating the protocols adopted thereto, it includes mainly "civil and political" rights, but also provides for the right to property. All 47 Council of Europe members have become party to the European Convention. OAS adopted the American Convention on Human Rights in 1969, which has been ratified by 24 States. The American Convention contains rights similar to those in the European Convention but goes further by providing for a minimum of "socio-economic" rights. In contrast to these two treaties, the African Charter, adopted by OAU in 1981, contains justiciable "socio-economic" rights and elaborates on the duties of individuals and the rights of peoples. All AU members are parties to the African Charter.

The way in which the principal treaty is implemented or enforced differs in each region. In an evolution spanning many decades, the European system of implementation, operating out of Strasbourg, France, developed from a system where a Commission and a Court co-existed to form a single judicial institution. The European Court of Human Rights deals with individual cases. A dual model is in place in the Americas, consisting of the Inter-American Commission, based in Washington, D.C., and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in San José, Costa Rica. Individual complainants have to submit their grievances to the Inter-American Commission first; thereafter, the case may proceed to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The Commission also has the function of conducting on-site visits. After some recent institutional reforms, the African system now resembles the Inter-American system.

Fledgling Arab and Muslim regional systems have also emerged under the League of Arab States and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC). According to the Islamic world view, the Koran and other religious sources play a dominant role in the regulation of social life.

The League of Arab States was founded in terms of the Pact of the League of Arab States of 1945. Its overriding aim is to strengthen unity among Arab States by developing closer links between its members. The Pact emphasizes the independence and sovereignty of its members, but no mention is made in its founding document of either the contents or principles of human rights.

At the Teheran World Conference in 1968, some Arab States managed to have the position of Arabs in the territories occupied by Israel included in the agenda and successfully articulated it as a human rights issue. This created awareness of human rights among the Arab States in the aftermath of a number of defeats at the hands of Israel in 1967. However, at the Teheran Conference and thereafter, the commitment of the Arab League to human rights was primarily on directing criticism against Israel over its treatment of the inhabitants in Palestine and other occupied areas. In 1968, a regional conference on human rights was held in Beirut, where the Permanent Arab Commission on Human Rights (ACHR) was established. Since inception, the ACHR has been a highly politicized body, with its political nature accentuated by the method of appointment. The Commission does not consist of independent experts, as in many other international human rights bodies, but of government representatives. On 15 September 1994, the Council of the League of Arab States adopted the Arab Charter on Human Rights, whose entry into force, which required seven ratifications, was reached in 2008.

OIC, established in 1969, aims at the promotion of Islamic solidarity among the 56 Member States and works towards cooperation in the economic, cultural and political spheres. The major human rights document, adopted in Cairo in 1990 under this framework, is the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, which is of a declamatory nature only. As its title indicates, and given the aims of OIC, the declaration is closely based on the principles of the Shari'ah. In 2004, OIC adopted a binding instrument with a specific focus: the Covenant on the Rights of the Child in Islam. This Convention is open for ratification and will enter into force after 20 OIC member States have ratified it. Although the Convention provides for a monitoring mechanism -- the Islamic Committee on the Rights of the Child -- its mandate is only vaguely drafted.

Overlapping to some extent with the Muslim world, the heterogeneous Asian region stretches from Indonesia to Japan, comprising a diverse group of nations. Despite some efforts by the United Nations, no supranational human rights convention or body has been established in the Asia-Pacific region. In the absence of an intergovernmental organization serving as a regional umbrella that unites all the diverse States in this region, a regional human rights system remains unlikely.

Subregional level In more recent times, the subregional level has emerged as another site for human rights struggle, particularly in Africa. As a result of a weak regional system under the African Union, a number of African sub-Regional Economic Communities (RECs) emerged from the 1970s: most prominently, the Economic Community of West African States, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the East African Community (EAC). Although these RECs are primarily aimed at subregional economic integration, and not at the realization of human rights, there is an inevitable overlap in that their aims of economic integration and poverty eradication are linked to the realization of socio-economic rights. In a number of the founding treaties of RECs, human rights are given explicit recognition as being integral to the organizations' aims. By creating subregional courts with an implicit, or sometimes explicit, mandate to deal with human rights cases, it is apparent that these economic communities have become key role-players in the African regional human rights system.

Two decisions of subregional courts illustrate the growing significance of RECs to human rights protection. In a case brought against Uganda, it was contended that Uganda violated the EAC Treaty when it re-arrested 14 accused persons after they had been granted bail. 3 The Court, in 2007, held that Uganda had violated the rule of law doctrine, as enshrined among the fundamental principles governing EAC.

In its first decision on the merits of a case, delivered in November 2008, 4 the SADC Tribunal held that it had jurisdiction, on the basis of the SADC Treaty, to deal with the acquisition of agricultural land by the Zimbabwean Government, carried out under an amendment to the Constitution (Amendment 17). The Tribunal further found that, as it targeted white farmers, the Zimbabwean land reform programme violated article 6(2) of the SADC Treaty, which outlaws discrimination on the grounds of race, among other factors. As to the remedial order, the Tribunal directed Zimbabwe to protect the possession, occupation and ownership of lands belonging to applicants and pay fair compensation to those whose land had already been expropriated.

Promising developments towards subregional human rights protection have also recently occurred in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), bringing together the founding States of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines. Although ASEAN was established in 1967, a formal founding treaty (the ASEAN Charter) was adopted only in 2007. The Charter envisages the establishment of an ASEAN human rights body -- a process that is still underway.

Not by States Alone Advances in human rights are not dependent only on States. Non-governmental organizations have been very influential in advancing awareness on important issues and have prepared the ground for declarations and treaties subsequently adopted by the United Nations.

The role of civil society is of particular importance when the contentiousness of an issue inhibits State action. The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity is a case in point. Although it was adopted in November 2006 by 29 experts from only 25 countries, the 29 principles contained in the document -- related to State obligations in respect of sexual orientation and gender identity -- are becoming an internationally accepted point of reference and are likely to steer future discussions.

The international human rights law landscape today looks radically different from 60 years ago when the Universal Declaration was adopted. Significant advances have been made since the Second World War in expanding the normative reach of international human rights law, leading to the proliferation of human rights law at the international level. Over the last few decades, however, attention has shifted to the implementation and enforcement of human rights norms, to the development of more secure safety nets and to a critical appraisal of the impact of the norms. Greater concern for human rights has also been accompanied with greater emphasis on the individual liability of those responsible for gross human rights violations in the form of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The creation of international criminal tribunals, including the International Criminal Court in 1998, constitutes a trend towards the humanization of international law. The further juridification of international human rights law is exemplified by the establishment of more courts, the extension of judicial mandates to include human rights, and the unequivocal acceptance that all rights are justiciable. With the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, there is much clearer acceptance of the principle of indivisibility under international human rights law. However, the constant evolution of the international human rights regime depends greatly on non-State actors, as is exemplified by their role in advocating for and preparing the normative ground for the recognition of the rights of "sexual minorities". There is no doubt that the landscape is to undergo dramatic changes in the next 60 years.

1. In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All, Report of the Secretary-General, UN Doc A/49/2005, 21 March 2005.

2. UN Doc. A/RES/60/251 (para 13), 3 April 2006, recommending to the Economic and Social Council to "abolish" the Commission on Human Rights on 16 June 2006.

3. James Katabazi and Others v Secretary-General of the EAC and Attorney-General of Uganda, Reference 1 of 2007, East African Court of Justice, 1 November 2007.

4. Mike Campbell (Pvt) Limited and Others v Republic of Zimbabwe, Case SADCT 2/07, SADC Tribunal, 28 November 2008.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

World Down Syndrome Day: A Chance to End the Stereotypes

The international community, led by the United Nations, can continue to improve the lives of people with Down syndrome by addressing stereotypes and misconceptions.

Population and Climate Change: Decent Living for All without Compromising Climate Mitigation

A rise in the demand for energy linked to increasing incomes should not be justification for keeping people in poverty solely to avoid an escalation in emissions and its effects on climate change.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics