Essay on Addiction for Students and Children

500 words essay on addiction.

As we all know that excess of anything can be very dangerous, the same way, addiction of any kind can hamper the life quality of an individual. The phrase states that addiction is a family disease as one person uses and the whole family suffers. The above statement stands true in all its essence as the addict does not merely suffer but the people around him suffer greatly too. However, that does not mean they can’t be helped. Addiction is curable and we must not give up on the person who is addicted, rather help them out for a better life.

Cost of Addiction

Addiction comes at a great cost and we need to be able to recognize its harmful consequences to not let ourselves or anyone become an addict. Firstly, addiction has major health hazards. Intake of anything is bad for our body , and it does not matter what type of addiction it is, it will always impact the mental and physical health of a person.

For instance, if you are addicted to drugs or food, you will get various diseases and illnesses. Similarly, if you are addicted to video games, your mental health will also suffer along with physical health.

Moreover, people who are addicts usually face monetary issues. As they use that thing in excess, they spend loads of money on it. People become obsessed with spending all their fortunes on that one thing to satisfy their addiction. Thus, all these addictions of drugs , alcohol , gambling, and more drain the finances of a person and they usually end up in debt or even worse.

Furthermore, the personal and professional relationships of addicts suffer the most. They end up doing things or making decisions that do not work in their favor. This constraint the relationships of people and they drift apart.

Moreover, it also hampers their studies or work life. When you are spending all your money and time on your addiction, naturally your concentration levels in other things will drop. However, all this is not impossible to beat. There are many ways through which one can beat their addiction.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Beat Your Addiction

It is best to work towards beating your addiction rather than getting beat by it. One can try many ways to do so. Firstly, recognize and identify that you have an addiction problem. That is the first step to getting cured. You need to take some time and understand the symptoms in order to treat them. Motivate yourself to do better.

After that, understand that the journey will be long but worthwhile. Identify the triggers in your life and try to stay away from them as far as possible. There is no shame in asking for professional help. Always remember that professionals can always help you get better. Enroll yourself in rehabilitation programs and try to make the most out of them.

Most importantly, do not be hesitant in talking to your loved ones. Approach them and talk it out as they care most about you. They will surely help you get on the right path and help you in beating addiction for better health and life.

Q.1 What are the consequences of addiction?

A.1 Addiction has very severe consequences. Some of them are health hazards, monetary issues, relationship problems, adverse problems on studies and work of a person. It seriously hampers the quality of life of a person.

Q.2 How can one get rid of addiction?

A.2 A little help can go a long way. One can get rid of addiction by enrolling in rehabilitation programs and opening up about their struggle. Try to take professional help and talk with your close ones to become better.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neuropsychopharmacology

- v.46(10); 2021 Sep

Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience

Markus heilig.

1 Center for Social and Affective Neuroscience, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

James MacKillop

2 Peter Boris Centre for Addictions Research, McMaster University and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton, ON Canada

3 Homewood Research Institute, Guelph, ON Canada

Diana Martinez

4 New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY USA

Jürgen Rehm

5 Institute for Mental Health Policy Research & Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Toronto, ON Canada

6 Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto (UofT), Toronto, ON Canada

7 Klinische Psychologie & Psychotherapie, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

8 Department of International Health Projects, Institute for Leadership and Health Management, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia

Lorenzo Leggio

9 Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, Translational Addiction Medicine Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore and Bethesda, MD USA

Louk J. M. J. Vanderschuren

10 Department of Population Health Sciences, Unit Animals in Science and Society, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands

The view that substance addiction is a brain disease, although widely accepted in the neuroscience community, has become subject to acerbic criticism in recent years. These criticisms state that the brain disease view is deterministic, fails to account for heterogeneity in remission and recovery, places too much emphasis on a compulsive dimension of addiction, and that a specific neural signature of addiction has not been identified. We acknowledge that some of these criticisms have merit, but assert that the foundational premise that addiction has a neurobiological basis is fundamentally sound. We also emphasize that denying that addiction is a brain disease is a harmful standpoint since it contributes to reducing access to healthcare and treatment, the consequences of which are catastrophic. Here, we therefore address these criticisms, and in doing so provide a contemporary update of the brain disease view of addiction. We provide arguments to support this view, discuss why apparently spontaneous remission does not negate it, and how seemingly compulsive behaviors can co-exist with the sensitivity to alternative reinforcement in addiction. Most importantly, we argue that the brain is the biological substrate from which both addiction and the capacity for behavior change arise, arguing for an intensified neuroscientific study of recovery. More broadly, we propose that these disagreements reveal the need for multidisciplinary research that integrates neuroscientific, behavioral, clinical, and sociocultural perspectives.

Introduction

Close to a quarter of a century ago, then director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse Alan Leshner famously asserted that “addiction is a brain disease”, articulated a set of implications of this position, and outlined an agenda for realizing its promise [ 1 ]. The paper, now cited almost 2000 times, put forward a position that has been highly influential in guiding the efforts of researchers, and resource allocation by funding agencies. A subsequent 2000 paper by McLellan et al. [ 2 ] examined whether data justify distinguishing addiction from other conditions for which a disease label is rarely questioned, such as diabetes, hypertension or asthma. It concluded that neither genetic risk, the role of personal choices, nor the influence of environmental factors differentiated addiction in a manner that would warrant viewing it differently; neither did relapse rates, nor compliance with treatment. The authors outlined an agenda closely related to that put forward by Leshner, but with a more clinical focus. Their conclusion was that addiction should be insured, treated, and evaluated like other diseases. This paper, too, has been exceptionally influential by academic standards, as witnessed by its ~3000 citations to date. What may be less appreciated among scientists is that its impact in the real world of addiction treatment has remained more limited, with large numbers of patients still not receiving evidence-based treatments.

In recent years, the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease has come under increasing criticism. When first put forward, the brain disease view was mainly an attempt to articulate an effective response to prevailing nonscientific, moralizing, and stigmatizing attitudes to addiction. According to these attitudes, addiction was simply the result of a person’s moral failing or weakness of character, rather than a “real” disease [ 3 ]. These attitudes created barriers for people with substance use problems to access evidence-based treatments, both those available at the time, such as opioid agonist maintenance, cognitive behavioral therapy-based relapse prevention, community reinforcement or contingency management, and those that could result from research. To promote patient access to treatments, scientists needed to argue that there is a biological basis beneath the challenging behaviors of individuals suffering from addiction. This argument was particularly targeted to the public, policymakers and health care professionals, many of whom held that since addiction was a misery people brought upon themselves, it fell beyond the scope of medicine, and was neither amenable to treatment, nor warranted the use of taxpayer money.

Present-day criticism directed at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease is of a very different nature. It originates from within the scientific community itself, and asserts that this conceptualization is neither supported by data, nor helpful for people with substance use problems [ 4 – 8 ]. Addressing these critiques requires a very different perspective, and is the objective of our paper. We readily acknowledge that in some cases, recent critiques of the notion of addiction as a brain disease as postulated originally have merit, and that those critiques require the postulates to be re-assessed and refined. In other cases, we believe the arguments have less validity, but still provide an opportunity to update the position of addiction as a brain disease. Our overarching concern is that questionable arguments against the notion of addiction as a brain disease may harm patients, by impeding access to care, and slowing development of novel treatments.

A premise of our argument is that any useful conceptualization of addiction requires an understanding both of the brains involved, and of environmental factors that interact with those brains [ 9 ]. These environmental factors critically include availability of drugs, but also of healthy alternative rewards and opportunities. As we will show, stating that brain mechanisms are critical for understanding and treating addiction in no way negates the role of psychological, social and socioeconomic processes as both causes and consequences of substance use. To reflect this complex nature of addiction, we have assembled a team with expertise that spans from molecular neuroscience, through animal models of addiction, human brain imaging, clinical addiction medicine, to epidemiology. What brings us together is a passionate commitment to improving the lives of people with substance use problems through science and science-based treatments, with empirical evidence as the guiding principle.

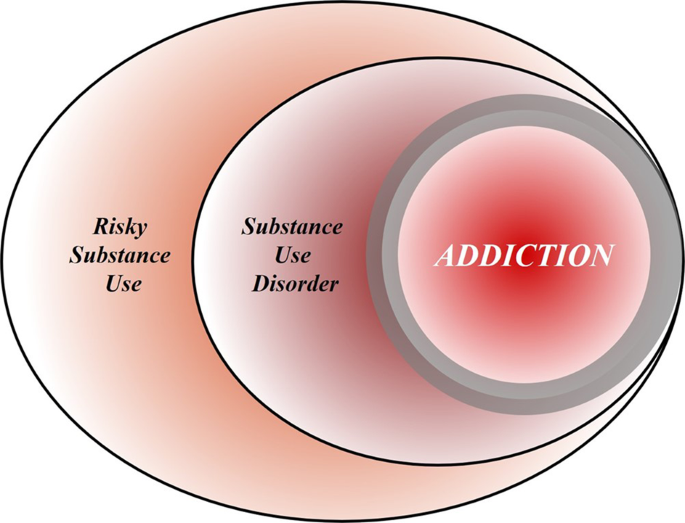

To achieve this goal, we first discuss the nature of the disease concept itself, and why we believe it is important for the science and treatment of addiction. This is followed by a discussion of the main points raised when the notion of addiction as a brain disease has come under criticism. Key among those are claims that spontaneous remission rates are high; that a specific brain pathology is lacking; and that people suffering from addiction, rather than behaving “compulsively”, in fact show a preserved ability to make informed and advantageous choices. In the process of discussing these issues, we also address the common criticism that viewing addiction as a brain disease is a fully deterministic theory of addiction. For our argument, we use the term “addiction” as originally used by Leshner [ 1 ]; in Box 1 , we map out and discuss how this construct may relate to the current diagnostic categories, such as Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and its different levels of severity (Fig. 1) .

Risky (hazardous) substance use refers to quantity/frequency indicators of consumption; SUD refers to individuals who meet criteria for a DSM-5 diagnosis (mild, moderate, or severe); and addiction refers to individuals who exhibit persistent difficulties with self-regulation of drug consumption. Among high-risk individuals, a subgroup will meet criteria for SUD and, among those who have an SUD, a further subgroup would be considered to be addicted to the drug. However, the boundary for addiction is intentionally blurred to reflect that the dividing line for defining addiction within the category of SUD remains an open empirical question.

Box 1 What’s in a name? Differentiating hazardous use, substance use disorder, and addiction

Although our principal focus is on the brain disease model of addiction, the definition of addiction itself is a source of ambiguity. Here, we provide a perspective on the major forms of terminology in the field.

Hazardous Substance Use

Hazardous (risky) substance use refers to quantitative levels of consumption that increase an individual’s risk for adverse health consequences. In practice, this pertains to alcohol use [ 110 , 111 ]. Clinically, alcohol consumption that exceeds guidelines for moderate drinking has been used to prompt brief interventions or referral for specialist care [ 112 ]. More recently, a reduction in these quantitative levels has been validated as treatment endpoints [ 113 ].

Substance Use Disorder

SUD refers to the DSM-5 diagnosis category that encompasses significant impairment or distress resulting from specific categories of psychoactive drug use. The diagnosis of SUD is operationalized as 2 or more of 11 symptoms over the past year. As a result, the diagnosis is heterogenous, with more than 1100 symptom permutations possible. The diagnosis in DSM-5 is the result of combining two diagnoses from the DSM-IV, abuse and dependence, which proved to be less valid than a single dimensional approach [ 114 ]. Critically, SUD includes three levels of severity: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (6+ symptoms). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system retains two diagnoses, harmful use (lower severity) and substance dependence (higher severity).

Addiction is a natural language concept, etymologically meaning enslavement, with the contemporary meaning traceable to the Middle and Late Roman Republic periods [ 115 ]. As a scientific construct, drug addiction can be defined as a state in which an individual exhibits an inability to self-regulate consumption of a substance, although it does not have an operational definition. Regarding clinical diagnosis, as it is typically used in scientific and clinical parlance, addiction is not synonymous with the simple presence of SUD. Nowhere in DSM-5 is it articulated that the diagnostic threshold (or any specific number/type of symptoms) should be interpreted as reflecting addiction, which inherently connotes a high degree of severity. Indeed, concerns were raised about setting the diagnostic standard too low because of the issue of potentially conflating a low-severity SUD with addiction [ 116 ]. In scientific and clinical usage, addiction typically refers to individuals at a moderate or high severity of SUD. This is consistent with the fact that moderate-to-severe SUD has the closest correspondence with the more severe diagnosis in ICD [ 117 – 119 ]. Nonetheless, akin to the undefined overlap between hazardous use and SUD, the field has not identified the exact thresholds of SUD symptoms above which addiction would be definitively present.

Integration

The ambiguous relationships among these terms contribute to misunderstandings and disagreements. Figure 1 provides a simple working model of how these terms overlap. Fundamentally, we consider that these terms represent successive dimensions of severity, clinical “nesting dolls”. Not all individuals consuming substances at hazardous levels have an SUD, but a subgroup do. Not all individuals with a SUD are addicted to the drug in question, but a subgroup are. At the severe end of the spectrum, these domains converge (heavy consumption, numerous symptoms, the unambiguous presence of addiction), but at low severity, the overlap is more modest. The exact mapping of addiction onto SUD is an open empirical question, warranting systematic study among scientists, clinicians, and patients with lived experience. No less important will be future research situating our definition of SUD using more objective indicators (e.g., [ 55 , 120 ]), brain-based and otherwise, and more precisely in relation to clinical needs [ 121 ]. Finally, such work should ultimately be codified in both the DSM and ICD systems to demarcate clearly where the attribution of addiction belongs within the clinical nosology, and to foster greater clarity and specificity in scientific discourse.

What is a disease?

In his classic 1960 book “The Disease Concept of Alcoholism”, Jellinek noted that in the alcohol field, the debate over the disease concept was plagued by too many definitions of “alcoholism” and too few definitions of “disease” [ 10 ]. He suggested that the addiction field needed to follow the rest of medicine in moving away from viewing disease as an “entity”, i.e., something that has “its own independent existence, apart from other things” [ 11 ]. To modern medicine, he pointed out, a disease is simply a label that is agreed upon to describe a cluster of substantial, deteriorating changes in the structure or function of the human body, and the accompanying deterioration in biopsychosocial functioning. Thus, he concluded that alcoholism can simply be defined as changes in structure or function of the body due to drinking that cause disability or death. A disease label is useful to identify groups of people with commonly co-occurring constellations of problems—syndromes—that significantly impair function, and that lead to clinically significant distress, harm, or both. This convention allows a systematic study of the condition, and of whether group members benefit from a specific intervention.

It is not trivial to delineate the exact category of harmful substance use for which a label such as addiction is warranted (See Box 1 ). Challenges to diagnostic categorization are not unique to addiction, however. Throughout clinical medicine, diagnostic cut-offs are set by consensus, commonly based on an evolving understanding of thresholds above which people tend to benefit from available interventions. Because assessing benefits in large patient groups over time is difficult, diagnostic thresholds are always subject to debate and adjustments. It can be debated whether diagnostic thresholds “merely” capture the extreme of a single underlying population, or actually identify a subpopulation that is at some level distinct. Resolving this issue remains challenging in addiction, but once again, this is not different from other areas of medicine [see e.g., [ 12 ] for type 2 diabetes]. Longitudinal studies that track patient trajectories over time may have a better ability to identify subpopulations than cross-sectional assessments [ 13 ].

By this pragmatic, clinical understanding of the disease concept, it is difficult to argue that “addiction” is unjustified as a disease label. Among people who use drugs or alcohol, some progress to using with a quantity and frequency that results in impaired function and often death, making substance use a major cause of global disease burden [ 14 ]. In these people, use occurs with a pattern that in milder forms may be challenging to capture by current diagnostic criteria (See Box 1 ), but is readily recognized by patients, their families and treatment providers when it reaches a severity that is clinically significant [see [ 15 ] for a classical discussion]. In some cases, such as opioid addiction, those who receive the diagnosis stand to obtain some of the greatest benefits from medical treatments in all of clinical medicine [ 16 , 17 ]. Although effect sizes of available treatments are more modest in nicotine [ 18 ] and alcohol addiction [ 19 ], the evidence supporting their efficacy is also indisputable. A view of addiction as a disease is justified, because it is beneficial: a failure to diagnose addiction drastically increases the risk of a failure to treat it [ 20 ].

Of course, establishing a diagnosis is not a requirement for interventions to be meaningful. People with hazardous or harmful substance use who have not (yet) developed addiction should also be identified, and interventions should be initiated to address their substance-related risks. This is particularly relevant for alcohol, where even in the absence of addiction, use is frequently associated with risks or harm to self, e.g., through cardiovascular disease, liver disease or cancer, and to others, e.g., through accidents or violence [ 21 ]. Interventions to reduce hazardous or harmful substance use in people who have not developed addiction are in fact particularly appealing. In these individuals, limited interventions are able to achieve robust and meaningful benefits [ 22 ], presumably because patterns of misuse have not yet become entrenched.

Thus, as originally pointed out by McLellan and colleagues, most of the criticisms of addiction as a disease could equally be applied to other medical conditions [ 2 ]. This type of criticism could also be applied to other psychiatric disorders, and that has indeed been the case historically [ 23 , 24 ]. Today, there is broad consensus that those criticisms were misguided. Few, if any healthcare professionals continue to maintain that schizophrenia, rather than being a disease, is a normal response to societal conditions. Why, then, do people continue to question if addiction is a disease, but not whether schizophrenia, major depressive disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder are diseases? This is particularly troubling given the decades of data showing high co-morbidity of addiction with these conditions [ 25 , 26 ]. We argue that it comes down to stigma. Dysregulated substance use continues to be perceived as a self-inflicted condition characterized by a lack of willpower, thus falling outside the scope of medicine and into that of morality [ 3 ].

Chronic and relapsing, developmentally-limited, or spontaneously remitting?

Much of the critique targeted at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease focuses on its original assertion that addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition. Epidemiological data are cited in support of the notion that large proportions of individuals achieve remission [ 27 ], frequently without any formal treatment [ 28 , 29 ] and in some cases resuming low risk substance use [ 30 ]. For instance, based on data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) study [ 27 ], it has been pointed out that a significant proportion of people with an addictive disorder quit each year, and that most afflicted individuals ultimately remit. These spontaneous remission rates are argued to invalidate the concept of a chronic, relapsing disease [ 4 ].

Interpreting these and similar data is complicated by several methodological and conceptual issues. First, people may appear to remit spontaneously because they actually do, but also because of limited test–retest reliability of the diagnosis [ 31 ]. For instance, using a validated diagnostic interview and trained interviewers, the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism examined the likelihood that an individual diagnosed with a lifetime history of substance dependence would retain this classification after 5 years. This is obviously a diagnosis that, once met, by definition cannot truly remit. Lifetime alcohol dependence was indeed stable in individuals recruited from addiction treatment units, ~90% for women, and 95% for men. In contrast, in a community-based sample similar to that used in the NESARC [ 27 ], stability was only ~30% and 65% for women and men, respectively. The most important characteristic that determined diagnostic stability was severity. Diagnosis was stable in severe, treatment-seeking cases, but not in general population cases of alcohol dependence.

These data suggest that commonly used diagnostic criteria alone are simply over-inclusive for a reliable, clinically meaningful diagnosis of addiction. They do identify a core group of treatment seeking individuals with a reliable diagnosis, but, if applied to nonclinical populations, also flag as “cases” a considerable halo of individuals for whom the diagnostic categorization is unreliable. Any meaningful discussion of remission rates needs to take this into account, and specify which of these two populations that is being discussed. Unfortunately, the DSM-5 has not made this task easier. With only 2 out of 11 symptoms being sufficient for a diagnosis of SUD, it captures under a single diagnostic label individuals in a “mild” category, whose diagnosis is likely to have very low test–retest reliability, and who are unlikely to exhibit a chronic relapsing course, together with people at the severe end of the spectrum, whose diagnosis is reliable, many of whom do show a chronic relapsing course.

The NESARC data nevertheless show that close to 10% of people in the general population who are diagnosed with alcohol addiction (here equated with DSM-IV “dependence” used in the NESARC study) never remitted throughout their participation in the survey. The base life-time prevalence of alcohol dependence in NESARC was 12.5% [ 32 ]. Thus, the data cited against the concept of addiction as a chronic relapsing disease in fact indicate that over 1% of the US population develops an alcohol-related condition that is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and whose chronic and/or relapsing nature cannot be disputed, since it does not remit.

Secondly, the analysis of NESARC data [ 4 , 27 ] omits opioid addiction, which, together with alcohol and tobacco, is the largest addiction-related public health problem in the US [ 33 ]. This is probably the addictive condition where an analysis of cumulative evidence most strikingly supports the notion of a chronic disorder with frequent relapses in a large proportion of people affected [ 34 ]. Of course, a large number of people with opioid addiction are unable to express the chronic, relapsing course of their disease, because over the long term, their mortality rate is about 15 times greater than that of the general population [ 35 ]. However, even among those who remain alive, the prevalence of stable abstinence from opioid use after 10–30 years of observation is <30%. Remission may not always require abstinence, for instance in the case of alcohol addiction, but is a reasonable proxy for remission with opioids, where return to controlled use is rare. Embedded in these data is a message of literally vital importance: when opioid addiction is diagnosed and treated as a chronic relapsing disease, outcomes are markedly improved, and retention in treatment is associated with a greater likelihood of abstinence.

The fact that significant numbers of individuals exhibit a chronic relapsing course does not negate that even larger numbers of individuals with SUD according to current diagnostic criteria do not. For instance, in many countries, the highest prevalence of substance use problems is found among young adults, aged 18–25 [ 36 ], and a majority of these ‘age out’ of excessive substance use [ 37 ]. It is also well documented that many individuals with SUD achieve longstanding remission, in many cases without any formal treatment (see e.g., [ 27 , 30 , 38 ]).

Collectively, the data show that the course of SUD, as defined by current diagnostic criteria, is highly heterogeneous. Accordingly, we do not maintain that a chronic relapsing course is a defining feature of SUD. When present in a patient, however, such as course is of clinical significance, because it identifies a need for long-term disease management [ 2 ], rather than expectations of a recovery that may not be within the individual’s reach [ 39 ]. From a conceptual standpoint, however, a chronic relapsing course is neither necessary nor implied in a view that addiction is a brain disease. This view also does not mean that it is irreversible and hopeless. Human neuroscience documents restoration of functioning after abstinence [ 40 , 41 ] and reveals predictors of clinical success [ 42 ]. If anything, this evidence suggests a need to increase efforts devoted to neuroscientific research on addiction recovery [ 40 , 43 ].

Lessons from genetics

For alcohol addiction, meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies has estimated heritability at ~50%, while estimates for opioid addiction are even higher [ 44 , 45 ]. Genetic risk factors are to a large extent shared across substances [ 46 ]. It has been argued that a genetic contribution cannot support a disease view of a behavior, because most behavioral traits, including religious and political inclinations, have a genetic contribution [ 4 ]. This statement, while correct in pointing out broad heritability of behavioral traits, misses a fundamental point. Genetic architecture is much like organ structure. The fact that normal anatomy shapes healthy organ function does not negate that an altered structure can contribute to pathophysiology of disease. The structure of the genetic landscape is no different. Critics further state that a “genetic predisposition is not a recipe for compulsion”, but no neuroscientist or geneticist would claim that genetic risk is “a recipe for compulsion”. Genetic risk is probabilistic, not deterministic. However, as we will see below, in the case of addiction, it contributes to large, consistent probability shifts towards maladaptive behavior.

In dismissing the relevance of genetic risk for addiction, Hall writes that “a large number of alleles are involved in the genetic susceptibility to addiction and individually these alleles might very weakly predict a risk of addiction”. He goes on to conclude that “generally, genetic prediction of the risk of disease (even with whole-genome sequencing data) is unlikely to be informative for most people who have a so-called average risk of developing an addiction disorder” [ 7 ]. This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of polygenic risk. It is true that a large number of risk alleles are involved, and that the explanatory power of currently available polygenic risk scores for addictive disorders lags behind those for e.g., schizophrenia or major depression [ 47 , 48 ]. The only implication of this, however, is that low average effect sizes of risk alleles in addiction necessitate larger study samples to construct polygenic scores that account for a large proportion of the known heritability.

However, a heritability of addiction of ~50% indicates that DNA sequence variation accounts for 50% of the risk for this condition. Once whole genome sequencing is readily available, it is likely that it will be possible to identify most of that DNA variation. For clinical purposes, those polygenic scores will of course not replace an understanding of the intricate web of biological and social factors that promote or prevent expression of addiction in an individual case; rather, they will add to it [ 49 ]. Meanwhile, however, genome-wide association studies in addiction have already provided important information. For instance, they have established that the genetic underpinnings of alcohol addiction only partially overlap with those for alcohol consumption, underscoring the genetic distinction between pathological and nonpathological drinking behaviors [ 50 ].

It thus seems that, rather than negating a rationale for a disease view of addiction, the important implication of the polygenic nature of addiction risk is a very different one. Genome-wide association studies of complex traits have largely confirmed the century old “infinitisemal model” in which Fisher reconciled Mendelian and polygenic traits [ 51 ]. A key implication of this model is that genetic susceptibility for a complex, polygenic trait is continuously distributed in the population. This may seem antithetical to a view of addiction as a distinct disease category, but the contradiction is only apparent, and one that has long been familiar to quantitative genetics. Viewing addiction susceptibility as a polygenic quantitative trait, and addiction as a disease category is entirely in line with Falconer’s theorem, according to which, in a given set of environmental conditions, a certain level of genetic susceptibility will determine a threshold above which disease will arise.

A brain disease? Then show me the brain lesion!

The notion of addiction as a brain disease is commonly criticized with the argument that a specific pathognomonic brain lesion has not been identified. Indeed, brain imaging findings in addiction (perhaps with the exception of extensive neurotoxic gray matter loss in advanced alcohol addiction) are nowhere near the level of specificity and sensitivity required of clinical diagnostic tests. However, this criticism neglects the fact that neuroimaging is not used to diagnose many neurologic and psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, ALS, migraine, Huntington’s disease, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Even among conditions where signs of disease can be detected using brain imaging, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, a scan is best used in conjunction with clinical acumen when making the diagnosis. Thus, the requirement that addiction be detectable with a brain scan in order to be classified as a disease does not recognize the role of neuroimaging in the clinic.

For the foreseeable future, the main objective of imaging in addiction research is not to diagnose addiction, but rather to improve our understanding of mechanisms that underlie it. The hope is that mechanistic insights will help bring forward new treatments, by identifying candidate targets for them, by pointing to treatment-responsive biomarkers, or both [ 52 ]. Developing innovative treatments is essential to address unmet treatment needs, in particular in stimulant and cannabis addiction, where no approved medications are currently available. Although the task to develop novel treatments is challenging, promising candidates await evaluation [ 53 ]. A particular opportunity for imaging-based research is related to the complex and heterogeneous nature of addictive disorders. Imaging-based biomarkers hold the promise of allowing this complexity to be deconstructed into specific functional domains, as proposed by the RDoC initiative [ 54 ] and its application to addiction [ 55 , 56 ]. This can ultimately guide the development of personalized medicine strategies to addiction treatment.

Countless imaging studies have reported differences in brain structure and function between people with addictive disorders and those without them. Meta-analyses of structural data show that alcohol addiction is associated with gray matter losses in the prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum, insula, and posterior cingulate cortex [ 57 ], and similar results have been obtained in stimulant-addicted individuals [ 58 ]. Meta-analysis of functional imaging studies has demonstrated common alterations in dorsal striatal, and frontal circuits engaged in reward and salience processing, habit formation, and executive control, across different substances and task-paradigms [ 59 ]. Molecular imaging studies have shown that large and fast increases in dopamine are associated with the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, but that after chronic drug use and during withdrawal, brain dopamine function is markedly decreased and that these decreases are associated with dysfunction of prefrontal regions [ 60 ]. Collectively, these findings have given rise to a widely held view of addiction as a disorder of fronto-striatal circuitry that mediates top-down regulation of behavior [ 61 ].

Critics reply that none of the brain imaging findings are sufficiently specific to distinguish between addiction and its absence, and that they are typically obtained in cross-sectional studies that can at best establish correlative rather than causal links. In this, they are largely right, and an updated version of a conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease needs to acknowledge this. Many of the structural brain findings reported are not specific for addiction, but rather shared across psychiatric disorders [ 62 ]. Also, for now, the most sophisticated tools of human brain imaging remain crude in face of complex neural circuit function. Importantly however, a vast literature from animal studies also documents functional changes in fronto-striatal circuits, as well their limbic and midbrain inputs, associated with addictive behaviors [ 63 – 68 ]. These are circuits akin to those identified by neuroimaging studies in humans, implicated in positive and negative emotions, learning processes and executive functions, altered function of which is thought to underlie addiction. These animal studies, by virtue of their cellular and molecular level resolution, and their ability to establish causality under experimental control, are therefore an important complement to human neuroimaging work.

Nevertheless, factors that seem remote from the activity of brain circuits, such as policies, substance availability and cost, as well as socioeconomic factors, also are critically important determinants of substance use. In this complex landscape, is the brain really a defensible focal point for research and treatment? The answer is “yes”. As powerfully articulated by Francis Crick [ 69 ], “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules”. Social and interpersonal factors are critically important in addiction, but they can only exert their influences by impacting neural processes. They must be encoded as sensory data, represented together with memories of the past and predictions about the future, and combined with representations of interoceptive and other influences to provide inputs to the valuation machinery of the brain. Collectively, these inputs drive action selection and execution of behavior—say, to drink or not to drink, and then, within an episode, to stop drinking or keep drinking. Stating that the pathophysiology of addiction is largely about the brain does not ignore the role of other influences. It is just the opposite: it is attempting to understand how those important influences contribute to drug seeking and taking in the context of the brain, and vice versa.

But if the criticism is one of emphasis rather than of principle—i.e., too much brain, too little social and environmental factors – then neuroscientists need to acknowledge that they are in part guilty as charged. Brain-centric accounts of addiction have for a long time failed to pay enough attention to the inputs that social factors provide to neural processing behind drug seeking and taking [ 9 ]. This landscape is, however, rapidly changing. For instance, using animal models, scientists are finding that lack of social play early in life increases the motivation to take addictive substances in adulthood [ 70 ]. Others find that the opportunity to interact with a fellow rat is protective against addiction-like behaviors [ 71 ]. In humans, a relationship has been found between perceived social support, socioeconomic status, and the availability of dopamine D2 receptors [ 72 , 73 ], a biological marker of addiction vulnerability. Those findings in turn provided translation of data from nonhuman primates, which showed that D2 receptor availability can be altered by changes in social hierarchy, and that these changes are associated with the motivation to obtain cocaine [ 74 ].

Epidemiologically, it is well established that social determinants of health, including major racial and ethnic disparities, play a significant role in the risk for addiction [ 75 , 76 ]. Contemporary neuroscience is illuminating how those factors penetrate the brain [ 77 ] and, in some cases, reveals pathways of resilience [ 78 ] and how evidence-based prevention can interrupt those adverse consequences [ 79 , 80 ]. In other words, from our perspective, viewing addiction as a brain disease in no way negates the importance of social determinants of health or societal inequalities as critical influences. In fact, as shown by the studies correlating dopamine receptors with social experience, imaging is capable of capturing the impact of the social environment on brain function. This provides a platform for understanding how those influences become embedded in the biology of the brain, which provides a biological roadmap for prevention and intervention.

We therefore argue that a contemporary view of addiction as a brain disease does not deny the influence of social, environmental, developmental, or socioeconomic processes, but rather proposes that the brain is the underlying material substrate upon which those factors impinge and from which the responses originate. Because of this, neurobiology is a critical level of analysis for understanding addiction, although certainly not the only one. It is recognized throughout modern medicine that a host of biological and non-biological factors give rise to disease; understanding the biological pathophysiology is critical for understanding etiology and informing treatment.

Is a view of addiction as a brain disease deterministic?

A common criticism of the notion that addiction is a brain disease is that it is reductionist and in the end therefore deterministic [ 81 , 82 ]. This is a fundamental misrepresentation. As indicated above, viewing addiction as a brain disease simply states that neurobiology is an undeniable component of addiction. A reason for deterministic interpretations may be that modern neuroscience emphasizes an understanding of proximal causality within research designs (e.g., whether an observed link between biological processes is mediated by a specific mechanism). That does not in any way reflect a superordinate assumption that neuroscience will achieve global causality. On the contrary, since we realize that addiction involves interactions between biology, environment and society, ultimate (complete) prediction of behavior based on an understanding of neural processes alone is neither expected, nor a goal.

A fairer representation of a contemporary neuroscience view is that it believes insights from neurobiology allow useful probabilistic models to be developed of the inherently stochastic processes involved in behavior [see [ 83 ] for an elegant recent example]. Changes in brain function and structure in addiction exert a powerful probabilistic influence over a person’s behavior, but one that is highly multifactorial, variable, and thus stochastic. Philosophically, this is best understood as being aligned with indeterminism, a perspective that has a deep history in philosophy and psychology [ 84 ]. In modern neuroscience, it refers to the position that the dynamic complexity of the brain, given the probabilistic threshold-gated nature of its biology (e.g., action potential depolarization, ion channel gating), means that behavior cannot be definitively predicted in any individual instance [ 85 , 86 ].

Driven by compulsion, or free to choose?

A major criticism of the brain disease view of addiction, and one that is related to the issue of determinism vs indeterminism, centers around the term “compulsivity” [ 6 , 87 – 90 ] and the different meanings it is given. Prominent addiction theories state that addiction is characterized by a transition from controlled to “compulsive” drug seeking and taking [ 91 – 95 ], but allocate somewhat different meanings to “compulsivity”. By some accounts, compulsive substance use is habitual and insensitive to its outcomes [ 92 , 94 , 96 ]. Others refer to compulsive use as a result of increasing incentive value of drug associated cues [ 97 ], while others view it as driven by a recruitment of systems that encode negative affective states [ 95 , 98 ].

The prototype for compulsive behavior is provided by obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), where compulsion refers to repeatedly and stereotypically carrying out actions that in themselves may be meaningful, but lose their purpose and become harmful when performed in excess, such as persistent handwashing until skin injuries result. Crucially, this happens despite a conscious desire to do otherwise. Attempts to resist these compulsions result in increasing and ultimately intractable anxiety [ 99 ]. This is in important ways different from the meaning of compulsivity as commonly used in addiction theories. In the addiction field, compulsive drug use typically refers to inflexible, drug-centered behavior in which substance use is insensitive to adverse consequences [ 100 ]. Although this phenomenon is not necessarily present in every patient, it reflects important symptoms of clinical addiction, and is captured by several DSM-5 criteria for SUD [ 101 ]. Examples are needle-sharing despite knowledge of a risk to contract HIV or Hepatitis C, drinking despite a knowledge of having liver cirrhosis, but also the neglect of social and professional activities that previously were more important than substance use. While these behaviors do show similarities with the compulsions of OCD, there are also important differences. For example, “compulsive” substance use is not necessarily accompanied by a conscious desire to withhold the behavior, nor is addictive behavior consistently impervious to change.

Critics question the existence of compulsivity in addiction altogether [ 5 – 7 , 89 ], typically using a literal interpretation, i.e., that a person who uses alcohol or drugs simply can not do otherwise. Were that the intended meaning in theories of addiction—which it is not—it would clearly be invalidated by observations of preserved sensitivity of behavior to contingencies in addiction. Indeed, substance use is influenced both by the availability of alternative reinforcers, and the state of the organism. The roots of this insight date back to 1940, when Spragg found that chimpanzees would normally choose a banana over morphine. However, when physically dependent and in a state of withdrawal, their choice preference would reverse [ 102 ]. The critical role of alternative reinforcers was elegantly brought into modern neuroscience by Ahmed et al., who showed that rats extensively trained to self-administer cocaine would readily forego the drug if offered a sweet solution as an alternative [ 103 ]. This was later also found to be the case for heroin [ 103 ], methamphetamine [ 104 ] and alcohol [ 105 ]. Early residential laboratory studies on alcohol use disorder indeed revealed orderly operant control over alcohol consumption [ 106 ]. Furthermore, efficacy of treatment approaches such as contingency management, which provides systematic incentives for abstinence [ 107 ], supports the notion that behavioral choices in patients with addictions remain sensitive to reward contingencies.

Evidence that a capacity for choosing advantageously is preserved in addiction provides a valid argument against a narrow concept of “compulsivity” as rigid, immutable behavior that applies to all patients. It does not, however, provide an argument against addiction as a brain disease. If not from the brain, from where do the healthy and unhealthy choices people make originate? The critical question is whether addictive behaviors—for the most part—result from healthy brains responding normally to externally determined contingencies; or rather from a pathology of brain circuits that, through probabilistic shifts, promotes the likelihood of maladaptive choices even when reward contingencies are within a normal range. To resolve this question, it is critical to understand that the ability to choose advantageously is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon, but rather is about probabilities and their shifts, multiple faculties within human cognition, and their interaction. Yes, it is clear that most people whom we would consider to suffer from addiction remain able to choose advantageously much, if not most, of the time. However, it is also clear that the probability of them choosing to their own disadvantage, even when more salutary options are available and sometimes at the expense of losing their life, is systematically and quantifiably increased. There is a freedom of choice, yet there is a shift of prevailing choices that nevertheless can kill.

Synthesized, the notion of addiction as a disease of choice and addiction as a brain disease can be understood as two sides of the same coin. Both of these perspectives are informative, and they are complementary. Viewed this way, addiction is a brain disease in which a person’s choice faculties become profoundly compromised. To articulate it more specifically, embedded in and principally executed by the central nervous system, addiction can be understood as a disorder of choice preferences, preferences that overvalue immediate reinforcement (both positive and negative), preferences for drug-reinforcement in spite of costs, and preferences that are unstable ( “I’ll never drink like that again;” “this will be my last cigarette” ), prone to reversals in the form of lapses and relapse. From a contemporary neuroscience perspective, pre-existing vulnerabilities and persistent drug use lead to a vicious circle of substantive disruptions in the brain that impair and undermine choice capacities for adaptive behavior, but do not annihilate them. Evidence of generally intact decision making does not fundamentally contradict addiction as a brain disease.

Conclusions

The present paper is a response to the increasing number of criticisms of the view that addiction is a chronic relapsing brain disease. In many cases, we show that those criticisms target tenets that are neither needed nor held by a contemporary version of this view. Common themes are that viewing addiction as a brain disease is criticized for being both too narrow (addiction is only a brain disease; no other perspectives or factors are important) or too far reaching (it purports to discover the final causes of addiction). With regard to disease course, we propose that viewing addiction as a chronic relapsing disease is appropriate for some populations, and much less so for others, simply necessitating better ways of delineating the populations being discussed. We argue that when considering addiction as a disease, the lens of neurobiology is valuable to use. It is not the only lens, and it does not have supremacy over other scientific approaches. We agree that critiques of neuroscience are warranted [ 108 ] and that critical thinking is essential to avoid deterministic language and scientific overreach.

Beyond making the case for a view of addiction as a brain disease, perhaps the more important question is when a specific level of analysis is most useful. For understanding the biology of addiction and designing biological interventions, a neurobiological view is almost certainly the most appropriate level of analysis, in particular when informed by an understanding of the behavioral manifestations. In contrast, for understanding the psychology of addiction and designing psychological interventions, behavioral science is the natural realm, but one that can often benefit from an understanding of the underlying neurobiology. For designing policies, such as taxation and regulation of access, economics and public administration provide the most pertinent perspectives, but these also benefit from biological and behavioral science insights.

Finally, we argue that progress would come from integration of these scientific perspectives and traditions. E.O. Wilson has argued more broadly for greater consilience [ 109 ], unity of knowledge, in science. We believe that addiction is among the areas where consilience is most needed. A plurality of disciplines brings important and trenchant insights to bear on this condition; it is the exclusive remit of no single perspective or field. Addiction inherently and necessarily requires multidisciplinary examination. Moreover, those who suffer from addiction will benefit most from the application of the full armamentarium of scientific perspectives.

Funding and disclosures

Supported by the Swedish Research Council grants 2013-07434, 2019-01138 (MH); Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) under project number 912.14.093 (LJMJV); NIDA and NIAAA intramural research programs (LL; the content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health); the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research, Homewood Research Institute, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants AA025911, AA024930, AA025849, AA027679 (JM; the content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health).

MH has received consulting fees, research support or other compensation from Indivior, Camurus, BrainsWay, Aelis Farma, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. JM is a Principal and Senior Scientist at BEAM Diagnostics, Inc. DM, JR, LL, and LJMJV declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge comments by Drs. David Epstein, Kenneth Kendler and Naomi Wray.

Author contributions

All authors jointly drafted the paper.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

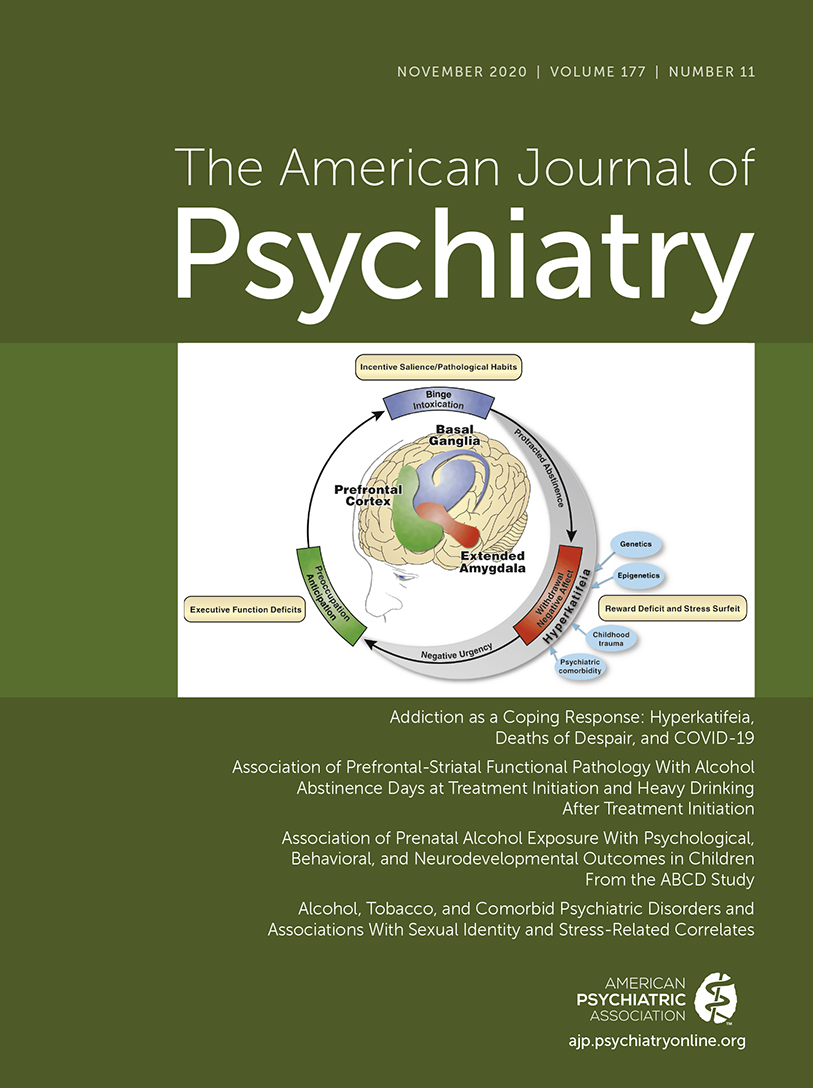

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Abstract , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

Essay on Addiction

Students are often asked to write an essay on Addiction in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Addiction

Understanding addiction.

Addiction is a strong desire to do something repeatedly, even if it’s harmful. It’s like a brain disease. People can get addicted to different things like drugs, alcohol, or even activities like gambling.

Why People Get Addicted

People can get addicted for many reasons. Some may feel good when they do something, so they repeat it. Others may want to escape from problems or stress. Sometimes, it’s because of peer pressure or trying to fit in.

Effects of Addiction

Addiction can harm a person’s health. It can lead to diseases, mental problems, and even death. It can also ruin relationships and cause problems at work or school.

Overcoming Addiction

Overcoming addiction is hard, but possible. It needs strong willpower and often help from doctors or therapists. Support from family and friends is also important. Remember, it’s okay to ask for help.

Preventing Addiction

To avoid addiction, we should learn about its dangers. It’s also important to make good friends and have healthy habits. Always remember, it’s okay to say no if something doesn’t feel right.

250 Words Essay on Addiction

What is addiction.

Addiction is when a person can’t stop doing something, even if it’s harmful. It can be about drugs, alcohol, games, or even food. The person knows it’s bad but can’t stop. It’s like a strong pull that keeps them going back.

How Does it Start?

Addiction often starts with trying something new. This could be a friend offering a cigarette, or playing a new video game. At first, it seems fun and exciting. But over time, the person starts needing it more and more. It becomes a need, not just a want.

The Impact of Addiction

Addiction can hurt a person in many ways. It can make them sick, or cause problems at school or work. It can also hurt their relationships with family and friends. They may lie or steal to keep doing what they’re addicted to. This can lead to feelings of guilt and shame.

Fighting Addiction