GetGoodEssay

Rights and responsibilities cannot be separated essay

As a society, we often discuss the concepts of rights and responsibilities, recognizing them as integral components of our social fabric. They are intertwined and interdependent, like two sides of the same coin. In this essay, we will delve into the multifaceted relationship between rights and responsibilities, shedding light on how they are inherently connected and why they cannot be separated. By understanding this connection, we can foster a harmonious coexistence and build a stronger foundation for a just and equitable society.

Understanding Rights:

Rights are the fundamental entitlements that individuals possess by virtue of their humanity. They encompass a wide range of aspects, such as civil liberties, political freedoms, social entitlements, and economic opportunities. The concept of rights is rooted in the belief that every person deserves to be treated with dignity, equality, and fairness. Examples of rights include the right to life, liberty, freedom of expression, education, and a fair trial.

Exploring Responsibilities:

Responsibilities, on the other hand, refer to the obligations and duties that individuals have towards themselves, others, and society as a whole. They are the moral, ethical, and legal guidelines that guide our actions and interactions. Responsibilities help maintain order, ensure accountability, and promote the well-being of individuals and communities. They can vary from personal responsibilities, such as self-care and personal growth, to societal responsibilities, such as respecting the rights of others and contributing to the common good.

The Inseparability of Rights and Responsibilities:

Rights and responsibilities are inseparable because they exist in a symbiotic relationship. Let’s examine the various aspects that highlight their interdependence:

- Mutual Reinforcement: Rights and responsibilities reinforce each other in a cyclical manner. In order to protect and preserve our rights, we must fulfil our responsibilities. For example, the right to freedom of expression comes with the responsibility to exercise it responsibly, respecting the rights and dignity of others. Likewise, by respecting the rights of others, we create an environment that upholds our own rights.

- Social Contract: The social contract theory posits that individuals willingly give up certain freedoms and abide by responsibilities in exchange for the protection of their rights within society. This implicit agreement recognizes that the exercise of one’s rights should not impinge upon the rights of others. Upholding responsibilities ensures a harmonious coexistence, wherein everyone’s rights are safeguarded.

- Collective Well-being: Rights and responsibilities are crucial for the collective well-being of society. When individuals fulfil their responsibilities, they contribute to the greater good, fostering social cohesion and harmony. Similarly, when rights are protected and respected, individuals are empowered to participate actively in society, leading to its overall progress.

- Legal Framework: Rights and responsibilities find expression in legal frameworks that govern society. Laws not only outline individual rights but also establish corresponding responsibilities. These legal obligations help maintain order and ensure a just society. Failure to fulfil responsibilities can result in legal consequences, which safeguard the rights of others.

Promoting Rights and Responsibilities:

To promote a society that values and upholds the inseparable connection between rights and responsibilities, we must:

- Education and Awareness: Promote education and awareness about rights and responsibilities from an early age. By fostering an understanding of the interdependence between the two, we can nurture responsible citizens who value the rights of others.

- Encouraging Civic Engagement: Encourage civic engagement and active participation in community affairs. When individuals take an active role in shaping their society, they develop a sense of responsibility towards the common good.

- Cultivating Empathy and Respect: Foster empathy and respect for diverse perspectives and experiences. This cultivates an environment where individuals are more likely to consider the impact of their actions on others’ rights.

- Encouraging Dialogue and Collaboration: Facilitate open dialogue and collaboration between individuals, communities, and institutions. Constructive conversations allow for the identification of common goals and the formulation of inclusive policies that balance rights and responsibilities.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the inseparable connection between rights and responsibilities forms the cornerstone of a just and harmonious society. By recognizing and embracing this interdependence, we can create an environment where individual rights are protected, responsibilities are fulfilled, and the collective well-being of society is upheld. Nurturing a culture that values both rights and responsibilities is crucial for fostering social progress, equality, and justice. Let us strive to uphold our responsibilities while respecting the rights of others, thereby creating a more inclusive and equitable world for all.

- Recent Posts

- Race is a social construct essay - August 24, 2023

- Hunt for the Wilder people essay - August 24, 2023

- Australia’s involvement in the vietnam war essay - August 24, 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Associate Members

- Executive Committee

- In Memoriam

- The InterAction Council and its First 25 Years

- Comments from world leaders

- Annual Plenary Meetings

- High-Level Expert Group meetings

- Economic revitalization

- Peace & security

- Universal ethical standards

- Final Communiqué

- Chairman's Reports

- Declarations

- Publications

Don't be Afraid of Ethics! Why we Need to Talk of Responsibilities as well as Rights

By Hans Küng

"Is he afraid of ethics?" Not very long ago my dear friend Alfred Grosser, the political theorist from Paris, whispered this question in my ear. The occasion was a televised dispute in Baden Baden, in which the presenter was once again gallantly dismissing the question of ethics with a reference to more immediate issues. This question came home to me again on reading the first contributions to the discussion on the proposal for a Universal Declaration of Human Responsibilities.1 As one of the three "academic advisors" to the InterAction Council, which is made up of former heads of state and governments, I was responsible not only for the first draft of this declaration but also for incorporating the numerous corrections suggested by the statesmen and the many experts from different continents, religions and disciplines. I therefore identify completely with this declaration. However, had I not been occupied for years with the problems, and had I not finally written A Global Ethic for Global Politics and Global Economics, published in 1997, which provides a broad treatment of all the problems which arise here, I would not have dared to formulate a first draft at all ? in close conjunction with the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights and the 1993 Declaration on a Global Ethic endorsed by the Parliament of the World's Religions, which required a secular political continuation. I say this simply to those who presuppose great naivety behind such declarations. That is certainly not the case!

I. Globalization calls for a global ethic

1.The declaration by the InterAction Council (IAC) is not an isolated document. It fulfils the urgent call by important international bodies for global ethical standards at present made in chapters of the reports both of the UN Commission on Global Governance (1995) and the World Commission on Culture and Development (1995). The same topic has also been discussed for a long time at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos and similarly in the new UNESCO Universal Ethics Project. Increasing attention is also being paid to it in Asia.2

2. The contemporary background to the questions raised in these international and interreligious bodies is the fact that the globalization of the economy, technology and the media has also brought a globalization of their problems (from the financial and labour markets to ecology and organized crime). If there are to be global solutions to them, they therefore also call for a globalization of ethics: no uniform ethical system, but a necessary minimum of shared ethical values, basic attitudes and criteria to which all regions, nations and interest groups can commit themselves. In another words there is a need for a common basic human ethic. There can be no new world order without a world ethic.

3. All this is not based on an "alarmist" analysis but on a realistic analysis of society. Critics have selected a few isolated quotations in particular from Helmut Schmidt's introductory article on the Declaration of Human Responsibilities in Die Zeit, printed here, and constructed a twofold charge from it:

a. the analysis of society underlying the Declaration is purely negative, gloomy, and oriented on decline;

b. such ''gloomy pictures of society'' would be used in ''potentially successful'' campaigns to ''supplement individual freedoms by reinforcing communal obligations'', a suspicion which culminates in the charge that all would be ''to limit the consequences of these individual freedoms.'' Over against this, emphatic reference is made to empirical investigations which are said to have discovered that there has been no ''repudiation of and decline in'' morality. As if Helmut Schmidt had asserted any of this. As if he had engaged in sheer ''alarmism'', demonized individualism, lamented a decline in values... Instead of this, Schmidt has indicated in a sober and realistic way some elements of danger in the process of globalization which have been seen and complained about for a long time all over the world. And Schmidt's plea for a Declaration of Human Responsibilities in particular presupposes that there are sufficient people also in the younger generation who at least in principle affirm ''responsibility'', ''morality'', and ''orientation on the common good.'' However, hardly anyone can seriously dispute that after the increase in and reinforcement of the rights of the individual over the past three decades, we need a stocktaking of education, journalism and politics. For:

4. A. sober diagnosis of the present notes that the radicalized individualization, accelerated secularization and ideological pluralization of present society is not just a negative development (thus the hierarchy of the Roman church), nor is it just a positive development (thus the belated representatives of the modern Enlightenment), but a highly ambivalent structural change. It brings opportunities and advantages, but also enormous risks and dangers, and in the midst of a revolutionary change raises new questions about criteria for values and points of orientation. This does not mean ''turning back the clock'', but recognizing the ''signs of the times''. As Marion Countess Dönhoff has remarked: ''Of course pluralistic democracy is unthinkable without the autonomous individual. So there can be no question of turning our backs on emancipation and secularization ? moreover that would be impossible. What we have to do is to educate citizens to greater responsibility and again give them a sense of solidarity. In our present world with its manifold temptations and attractions, the desire for a basic moral orientation, for norms and a binding system of values, is very great. Unless we take account of that, this society will not hold together." 3 Ralf Dahrendorf makes the following observation on the ''question of law and order'', which for him is one of the ''great questions of our time'', which for him is one of the ''great questions of our time'', along with unemployment and the welfare state. ''Lawlessness is the scourge of modernity. The sense of belonging disappears, and with is lost the support which a strong civil society gives to individuals and which they can take for granted. There is little to indicate why existing regulations and laws should be observed. Police control can replace social control only at the price of becoming authoritarian or, even worse, totalitarian. What holds modern society together?" 4 5. The question of what holds society together has in fact become more acute in postmodernity, which is a new epoch-making paradigm and does not just amount to a "second modernity". For:

- On the one hand a classic statement which the constitutional lawyer E.W. Böckenförde made at a very early stage is still true: ''The free secular state lives on the basis of presuppositions which it cannot guarantee without putting its freedom in question," 5 Modern society therefore needs a leading social and political ideas which emerged from common convictions, attitudes and traditions which would predate this freedom. These resources are not naturally there, but need to be looked after, aroused and handed down by education (''Responsibilities are not there ''just like that'').

- But on the other hand, what the sociologist H. Dubiel, among others, has emphasized is also true. The modern liberal social order has for a long time relied on ''habits of the heart'', on a thick cushion or pre-modern systems of meaning and obligation, though today - as is also confirmed by many teachers of religion and ethics - these are now ''worn out". 6

6. So what will hold post-modern society together? Certainly not religious fundamentalism of a biblicistic Protestant or a Roman Catholic kind. In the Declaration of Human Responsibilities there is deliberately not a single word about questions like birth control, abortion or euthanasia, on which there cannot be a consensus between and within the churches and religions. Nor however, will society be held together by the random pluralism which wants to sell us indifferentism, consumerism and hedonism as a "post-modern" vision of the future. But in the end the only thing that will hold society together is a new basic social consensus on shared values and criteria, which combines autonomous self-realization with responsibility in solidarity, rights with obligations. So we should not be afraid of an ethic which can be supported by quite different social groups. What we need is a fundamental yes to morality as a moral attitude, combined with a decisive no to moralism, which one-sidedly insists firmly on particular moral positions (e.g. on sexuality).

II. Human responsibility reinforce human rights

1. Individual human rights activists who have evidently been surprised by the new problems and the topicality of human responsibilities initially reacted with perplexity to the proposal for a Declaration of Responsibilities. Here I am not speaking of those one-issue people who wit Jeremiads and scenarios of destruction force all the problems of the world under a single perspective (say the intrinsically justified perspective of ecology, or any other perspective that they regard as the sum and solution of all problems of the world), and who want to force their one-dimensional, often monocausal view, of the world (Carl Amery's ''biospheric perspective'') upon everyone, instead of taking seriously the many levels and the many dimensions of human life and social reality, as the Declaration of Human Responsibilities does. I am speaking, rather, of those who use sophisticated arguments, like the German General Secretary of Amnesty International, Volkmar Deile. 7 In principle he affirms ''a necessary minimum of shared ethical values, basic attitudes and criteria to which all religions, nations, and interest groups can commit themselves'', but he has suspicions about a separate Declaration of Human Responsibilities. These suspicions seem to me to be worth considering, even if in the end I cannot share them. The main reason is that a Declaration of Human Responsibilities does not do the slightest damage to the Declaration of Human Rights. At any rate the UN Commissions and other international bodies cited here 8 are of the same opinion. Reflection on human responsibilities does not damage the realization of human rights. On the contrary, it furthers it. But let us look more closely.

2. A Declaration of Human Responsibilities supports and reinforces the Declaration of Human Rights from an ethical perspective, as is already stated programmatically in the preamble: ''We thus... renew and reinforce commitments already proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: namely, the full acceptance of the dignity of all people; their inalienable freedom and equality, and their solidarity with one another.'' If human rights are not realized in many places where they could be implemented, this is for the most part for want of lack of political and ethical will. There is no disputing the fact that ''the rule of law and the promotion of human rights depend on the readiness of men and women to act justly''. Nor will any of those who fight for human rights dispute this.

3. Of course it would be wrong to think that the legal validity of human rights depends on the actual realization of responsibilities. ''Human rights - a reward for good human behaviour''. Who would assert such nonsense? This would in fact mean that only those who had shown themselves worthy of rights by doing their duty towards society would have any. That would clearly offend against the unconditional dignity of the human person, which is itself a presupposition of both rights and responsibilities. No one has claimed that certain human responsibilities must be fulfilled first, by individuals or a community, before one can claim human rights. These are given with the human person, but this person is always at the same time one who has rights and responsibilities: ''All human rights are by definition directly bound up with the responsibility to observe them'' (V. Deile). Rights and responsibilities can certainly be distinguished neatly, but they cannot be separated from each other. Their relationship needs to be described in a differentiated way. They are not quantities which are to be added or subtracted externally, but two related dimensions of being human in the individual and the social sphere.

4. No rights without responsibilities: as such, this concern is by no means new, but goes back to the ''founding period'' of human rights. The demand was already made in the debate over human rights in the French Revolutionary Parliament of 1789 that if one proclaims a Declaration of Human Rights one must combine it with a Declaration of Human Responsibilities. Otherwise, in the end everyone would have only rights, which they would play off against one another, and no one would any longer know the responsibilities without which these rights cannot function. And what about us, 200 years after the Great Revolution? We in fact live largely in a society in which individual groups all too often insist on rights against others without recognizing any responsibilities that they themselves have. This is certainly not because of codified human rights as such, but because of certain false developments closely connected with them. In the consciousness of many people these have led to a preponderance of rights over responsibilities. Instead of the culture of human rights which is striven for, there is often an unculture of exaggerated claims to rights which ignores the intentions of human rights. The ''equilibrium of freedom, equality and participation'' is not simply ''present'', but time and again has to be realized afresh. After all, we indisputably live in a ''society of claims'', which often presents itself as a ''society of legal claims'', indeed as a ''society of legal disputes''. This makes the state a ''judiciary state'' (a term applied to the Federal Republic of Germany by the legal historian S.Simon). 9 Does this not suggest the need for a new concentration on responsibilities, particularly in our over-developed constitutional states with all their justified insistence on rights?

5. What Deile calls ''the reality of severe violations of human rights which spans the world'' should make it clear, particularly to professional champions of human rights who want to defend human rights ''unconditionally'', how much a declaration and explanation of human rights comes up against a void where people, particularly those in power, ignore (''What concern is that of mine?), neglect (''I have to represent only the interests of my firm''), fail to perceive (''That's what churches and charities are for''), or simply pretend falsely to be fulfilling (''We, the government, the board of directors, are doing all what we can), their humane responsibilities. The ''weakness of human rights'' is not in fact grounded in the concept itself ''but in the lack of any political (and ? I would add ? moral) will on the part of those responsible for implementing them'' (V.Deile). To put it plainly: an ethical impulse and the motivation of norms is needed for an effective realization of human rights. Many human rights champions active on the fronts of this world who confess their ''Yes to a Global Ethic'' 10 have already explicitly endorsed that. Therefore those who want to work effectively for human rights should welcome a new moral impulse and framework of ethical orientation and not reject it, to their own disadvantage.

6. The framework of ethical orientation in the Declaration of Human Responsibilities in some respects extends beyond human rights, which now ''clearly say what is commanded and forbidden only for quite specific spheres (V. Deile). Nor does the Declaration of Human Rights expressly raise such a comprehensive moral claim. A Declaration of Human Responsibilities must extend much further and begin at a much deeper level. And indeed the two basic principles of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities already offer an ethical orientation of everyday life which is as comprehensive as it is fundamental: the basic demand, ''Every human being must be treated humanely'' and the Golden Rule, ''What you do no wish to be done to yourself, do not do to others''. Not to mention the concrete requirements of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities for truthfulness, non-violence, fairness, solidarity, partnership, etc. Where the Declaration of Human Rights has to leave open what is morally permissible and what is not, the Declaration of Human Responsibilities states this ? not as a law but as a moral imperative. Therefore the Declaration of Human Responsibilities ''opens up the possibility of agreement ? democratic agreement ? about what is right and what is wrong. The responsibility of being interested in these important questions returns the manifesto to the individual? Thus it is not paternalistic but political. What else could it be?'' 11

7. If the Declaration of Human Responsibilities is mostly formulated ''anonymously'', since it is focussed less on the individual (to be protected) than on the state (the power of which has to be limited), while the Declaration of Human Responsibilities is also addressed to state and institutions, it is primarily and very directly addressed to responsible persons. Time and again it says, ''all people'' or ''every person''; indeed specific professional groups which have a particular responsibility in our society (politicians, officials, business leaders, writers, artists, doctors, lawyers, journalists, religious leaders) are explicitly addressed, but no one is singled out. It is beyond dispute that such a Declaration of Responsibilities represents a challenge in the age of random pluralism, at least for the ''winners'' in the process of individualism at the expense of others, and for all those who recognize only ''provided it's fun'' or ''it contributes to my personal advancement'' as the sole moral norm. But the declaration is not concerned with a new ''community ideology'', which is the criticism made of the communitarians around Amitai Etzioni. At least these people do not want to set up a ''tyranny of the common mind'' and to relieve people even of individual responsibility. That is what is done, rather, by their superficiality moral opposite numbers, who, fatally mistaking the crisis of the present, think that they have to propagate a ''confession of the selfish society'' or the ''virtue of having no orientation or ties'' as a way into the future.

8. Thus like the Declaration of Human Rights, the Declaration of Human Responsibilities is primarily a moral appeal. As such it does not have the direct binding character of international law, but it proclaims to the world public some basic norms for collective and individual behaviour which apply to everyone. This appeal is, of course, also meant to have an effect on legal and political practice. However, it does not aim at any legalistic morality. The Declaration of Responsibilities is not a ''blueprint for a legally binding canon of responsibilities with a world-wide application'', as has been insinuated. No such spectres should be conjured up at a time when even the pope and the curial apparatus can no longer implement their legalistic authoritarian moral views in their very own sphere (far less in the outside world). A key feature of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities is that it specifically does not aim at legal codification, which in any case is impossible in the case of moral attitudes like truthfulness and fairness. It aims at voluntarily taking responsibility. Such a declaration can of course lead to legal regulations in individual cases, or if it is applied to institutions. However, a Declaration of Human Responsibilities should be morally rather than legally binding.

III. ''Responsibilities'' can be misused - but so too can ''rights''

1. Particularly those who reject any revision of the Declaration of Human Rights (and this is certainly also rejected by the IAC) should argue for a Declaration of Human Responsibilities. To discredit the plea of many Asians for a recognition of responsibilities - traditional in Confucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam - a priori as authoritarian and paternalistic is to be blind to reality and arrogant in a Eurocentric way. It is obvious that here the attack on the idea of responsibilities is often governed by political interests. But that (makes) does not deprive the demand for responsibilities generally of its credibility, any more than the call for freedom is discredited because it is misused by robber baron capitalists or sensational journalists. To think that authoritarian systems would wait specifically for a Declaration of Responsibilities and in the future woo would be dependent on a Declaration of Responsibilities to uphold their authoritarian system is ridiculous. Rather, in the future it will be possible to address authoritarian systems more critically than before over their responsibility to show truthfulness and tolerance - which is not contained in any human rights. And this can have an effect. Authoritarian systems like those of Poland, the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, the Philippines or South Africa were overthrown without bloodshed, not least by moral arguments and demonstrations, with demands for ''truth'', ''freedom'', ''justice'', ''solidarity'', ''humanity'' slogans which often went beyond human rights. So human rights and human responsibilities should be seen together. A Declaration of Human Responsibilities can serve many people as a reference document in the same way as the Declaration of Human Rights - and this can be significant not least for education and schools.

2. Germans in particular have an additional problem here. Unfortunately they do not have the good fortune of the Anglo-Americans, who have three related terms with different emphases, ''duties'', ''obligations'' and ''responsibilities'' where they have to made do with one, ''Pflicht.'' It was exciting to see how among the professionals both in Paris (UNESCO) and Vienna (InterAction Council) and in Davos (World Economic Forum) each time quickly agreed on the term ''responsibilities'' to translate Pflicht. Why? Because this term more than the other words emphasizes inner responsibility rather than the external law, and inner responsibility must be the ultimate aim of a Declaration of Responsibilities, which can in no way enforce an ethic. If ''Verantwortlichkeit'' were accepted terminology, that would have been preferable, but it seemed possible to use this only on isolated occasions.

3. Europeans, and especially Germans, need to be reminded that this term Pflicht in the sense of ''duty'' has been shamefully misused in their more recent history. ''Duty'' (towards superiors, the Fuhrer, the Volk, the party, even the pope) has been hammered home by totalitarian, authoritarian and hierarchical ideologies of all kinds. So one can understand the anxious projections (''authoritarian state'', ''paternalism''... ), which have led to the word being made morally and ultimately even linguistically taboo. But should abusers prevent us from taking up positively a concept which has had a long history since Cicero and Ambrose, which was made a key concept of modern times and which even today seems irreplaceable? So we should not be afraid of ethics: responsibility exerts a moral pressure but it does not compel. It follows primarily not from purely technical or economic reason but from ethical reason, which encourages and urges human beings, whose nature is to be able to decide freedom, to act morally. And here it should be remembered that:

4. Not only obligations but also rights can be misused: particularly when, first, they are constantly used exclusively for one's own advantage and, secondly, when they are constantly exploited to the maximum, to their limit of their own extreme possibilities. Those who neglect their responsibilities finally also undermine rights. Even the state would be endangered if its citizens made no meaningful use of rights and employed them purely to their own advantage. Indeed, not even Amnesty International could survive if it was governed and supported by such egoistic ''being in the right'' instead of by ethically motivated activists. So we should be aware of false alternatives:

5. Liberating rights (in the West) versus enslaving responsibilities (in the East): this is a construction against which resolute opposition must be declared. The Declaration of Responsibilities which reinforces the Declaration of Rights could perceive a function of supplementing and mediating here ? without threatening the universal validity, the indivisibility and the cohesion of human rights. It could be a help towards avoiding a ''clash of civilizations'' which only the innocent can suppose to be ''long refuted'', as soon as on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Human Rights.

6. I share the love of freedom, and Isaiah Berlin was certainly right in saying that freedom is essentially about the absence of compulsion with the ''negative'' aim of avoiding interference: i.e. freedom from. But as a former Isaiah Berlin lecturer in Cambridge, perhaps I may modestly remark that a pure ''freedom from'' can be destructive and sometimes dangerous without a ''freedom for''; here the British sociologist Anthony Giddens confirms a piece of old theological wisdom. This should certainly not be a call for the exercise of freedom ''as service to the community'', which can easily lead to servitude, but is rather that freedom in responsibility without which liberty becomes libertinism, which in the end leaves people who live only for their egos inwardly burnt out. However, such libertinism becomes a social problem the moment there is a dramatic increase in the number of people who selfishly cultivate their own interests and the private aesthetic development of their everyday lives, and are ready for commitment only in so far as this serves their needs and sense of pleasure. Even the political weeklies and journals are slowly beginning to note this: recently major critical articles have appeared on ''The Shameless Society'' or ''The New Shamelessness''.

7. We need not worry: morality and community cannot be ''prescribed'' as obligations. And the best guarantee of peace is in fact a functioning state which guarantees its citizens the security of the law. Here human rights are the ''guiding star'' (not the ''explosive device'') of such a society. But precisely because community and morality cannot be prescribed, the personal responsibility of its citizens is indispensable. As we saw, the democratic state is dependent on a consensus of values, norms and responsibilities, precisely because it cannot and should not either create this consensus or prescribe it.

8. Those concerned with human rights in particular must know that the Declaration of Human Rights itself, in Article 29, contains a definition of the ''duties of everyone towards the community''. From this it follows with compelling logic that a Declaration of Human Responsibilities cannot in any way stand in contradiction to the Declaration of Human Rights. And if concrete forms of political, social and cultural articles on human rights were possible and necessary through international agreements in the 1960s, why should a development of Article 29 by an extended formulation of these responsibilities in the 1990s be illegitimate? On the contrary, precisely in the light of this it becomes clear that human rights and human responsibilities do not mutually restrict each other for society but supplement each other a fruitful way ? and all champions of human rights should recognize this as a reinforcement of their position. It is not by chance that this Article 29 speaks of the ''just requirements of morality, public order and general welfare in a democratic society''. But the asymmetrical structure in the determination of the relationship of rights and responsibilities must be noted.

IV. Not all responsibilities follow from rights

1. The decisive question, whether expressed or not, is whether alongside a claim to rights there is also a need for reflection on responsibilities. The answer to that is: All rights imply responsibilities, but not all responsibilities follow from rights. Here are three examples:

(a) The freedom of the press or of a journalist is guaranteed and protected by the modern constitutional state: the journalist, the newspaper, has the right to report freely. The state must protect this right actively, and if need be to enforce it. Therefore the state and the citizen have the responsibility of respecting the right of this newspaper of this journalist to free reporting. However, this right does not yet in any way touch on the responsibility of the journalist or the media themselves (which has been widely discussed since the death of Princess Diana) to inform the public truthfully and avoid sensational reporting which demeans the dignity of the human person (cf. Article 14 of the Declaration of Responsibilities). But that the freedom of opinion which critics claim entails a responsibility ''not to insult others'' is a claim to which no lawyer would subscribe. 12

(b) The right each individual to property is also guaranteed by the modern constitutional state. It contains the legal responsibility of others (the state of the individual citizen) to respect this property and not to misappropriate it. However, this right does not in any way affect the responsibility of property-owners themselves not to use the property in an anti-social way but to use it socially (this is laid down as a duty in the German Basic Law), to bridle the manifestly unquenchable human greed for money, power, prestige and consumption, and to use economic power in the service of social justice and social order (cf. Article 11).

(c)The freedom of conscience of individuals to decide in accordance with their own consciences contains the legal responsibility of themselves and others (individuals and the state) to respect any free decision of the conscience: the individual conscience is guaranteed protection by the constitution in democracies. However, this right by no means entails the ethical responsibility of individuals to follow their own conscience in every case, even, indeed precisely when this is unacceptable or abhorrent to them.

2. It follows from this that rights also entail certain responsibilities, and these are legal responsibilities. But by no means all responsibilities follow from rights. There are also independent ethical responsibilities which are directly grounded in the dignity of the human person. At a very early stage in the theoretical debate on this, two types of responsibility were distinguished: obligations in the narrower sense, ''complete'', legal obligations; and responsibilities in the wider sense, ''incomplete'', ethical responsibilities like those prompted by conscience, love and humanity. These are based on the insight of the individual and cannot be compelled by the state through law.

3. Thus ethics is not exhausted in law. The levels of law and ethics belong together, but a fundamental distinction is to be made between them, and this is particularly significant for human rights.

- Human beings have fundamental rights which are formulated in the Declarations of Human Rights. To these correspond the legal responsibilities of both state and individual citizens to respect and protect these rights. Here we are at the level of law, regulations, the judiciary, the police. External behaviour in conformity to the law can be examined; in principle the law can be appealed to and if need be enforced (''in the name of the law'').

- But at the same time human beings have original responsibilities which are already given with their personhood and are not grounded in any rights: these are ethical responsibilities which cannot be fixed by law. Here we are at the level of ethics, customs, the conscience, the "heart''... The inward, morally good disposition, or even truthfulness, cannot be tested directly; therefore it cannot be brought under the law, let alone be compelled (''thoughts are free''). The ''sanctions'' of the conscience are not of a legal kind but often of a moral kind - and can even be felt in dreams and sleeplessness. The fact that immorality rarely pays in the long run, even in politics and business, and often leads to conflicts with the criminal law, does not follow directly from the ethical imperative.

4. Where a gap yawns between law and ethics, the law does not function either. Whether human rights will be realized in concrete terms depends not only generally on the ethical will of those responsible, but often on the moral energy of an individual or a few people. Even the realization of the fundamental principle of international law, ''pacta sunt servanda'', ''treaties are to be kept'', depends quite decisively on the ethical will of the partner to the treaty, as the example of former Yugoslavia has again demonstrated. And must not truthfulness, which cannot be tested by law, be presupposed in the conclusion of any treaty, even if it cannot be compelled legally? ''Morality is good, rights are better'' (as Norbert Greinacher remarked) is a simple statement. For what use are any rights and laws if there are no morals, no moral disposition, no obligation of conscience behind them? In other words, the law needs a moral foundation! So the Declaration of Responsibilities says that a better world order cannot be created with laws, conventions and ordinances alone. Indeed, without an ethic, in the end the law will not stand. So it is meaningful and requisite to set a Declaration of Human Responsibilities alongside the Declaration of Human Rights. As I have remarked, the two do not restrict each other but support each other.

5. One last thing: the nineteen articles of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities are anything but a random cocktail. As any expert will easily recognize, they are a reshaping of the four elementary imperatives of humanity (not to kill, steal, lie, commit sexual immorality) translated for our time. Despite all differences between the faiths, these can already be found in Patanjali, the founder of Yoga, the Bhagavadgita and the Buddhist canon, and of course also in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, the Qur’an, and indeed in all the great religious and ethical traditions of humankind. No ''cultural relativism'' is being encouraged here; rather, this is overcome by the integration of culture-specific values into an ethical framework with an universal orientation. As we saw, like human rights, these fundamental human responsibilities have their point of reference, their centre and the nucleus in the acknowledgement of human dignity, which stands at the centre of the very first sentence of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities, as it does in the Declaration of Human Rights. From it follows the fundamental ethical imperative to treat every human being humanely, made concrete by the Golden Rule, which also does not express a right but a responsibility. Thus the Declaration of Responsibilities is an appeal to the institutions, but also to the moral consciousness of individuals, explicitly to note the ethical dimension in all action.

6. My final wish for the wider debate is for there to be no false fronts, no artificial oppositions between rights and responsibilities, between an ethic of freedom and an ethic of responsibility, but rather a grasping of the opportunities which there could be in such a perhaps epoch-making declaration, were it promulgated. After all, it is not every day that statesmen from all the continents agree on such a text and propagate such a cause. And above all let us not be afraid of ethics: rightly understood, ethics does not enslave but frees. It helps us to be truly human and to remain so.

1. Cf. the series on rights and responsibilities in Die Zeit, nos 41-48, 1997. Contributors included Helmut Schmidt, Constanze Stelzenmüller, Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff, Susanne Gaschke, Hans Küng, Norbert Greinacher, Carl Amery, and Marion Gräfin Donhoff. Where names appear in this article without further details they usually refer to this series.

2. Cf. the contribution by J. Frühbauer in this volume.

3. M. Gräfin Dönhoff, ''Verantwörtung für das Ganze'', in E. Teufel (ed.), Was hält die moderne Gesellschaft zusammen?, Frankfurt 1996, 44. Or Thomas Assheuer, addressing the naively optimistic propagandists of a ''second modernity'' (Ulrich Beck); ''To speak of a social and moral crisis is no longer the privilege of conservatives''. T. Assheuer, ''Im Prinzip ohne Hoffnung. Die ''zweite Moderne'' als Formel: Wie Soziologen alte Fragen neue drapieren'', Die Zeit, 18 July 1997.

4. R. Dahrendorf, ''Liberale ohne Heimat'', Die Ziet, 8 January 1998.

5. Thus the federal judge E. W.Bockenforde, ''Fundamente der Freiheit'', in ibid, 89. Böckenförde formulated the thesis quoted above thirty years ago, in the meantime it may be taken to have been fully accepted.

6. H. Dubiel, ''Von welchen Ressourcen leben wir? Erfolge und Grenzen der Aufklärung'', in F. Teufel (ed.), Was halt die moderne Gesellschaft zusammen (n.3), 81.

7. Cf. V. Deile, ''Rechte bedingungslos verteidigen'', Die Zeit, 21 November 1997.

8. There are more details in J. Fruhbauer.

9. Cf. the radio broadcast by the Director of the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History in Frankfurt am Main, D. Simon, ''Der Richter als Ersatzkaiser'' (manuscript).

10. Cf. H. Küng (ed.) Yes to a Global Ethic, London and New York 1996.

12. S Gaschke, ''Die Ego-Polizei", Die Zeit, 24 October 1997.

13. For this complex of problems see the correspondence between the World Press Freedom Committee and the InterAction Council.

Academic freedom can’t be separated from responsibility

PhD candidate, Sociological and Anthropological Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Disclosure statement

Karine Coen-Sanchez does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Ottawa provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA-FR.

University of Ottawa provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

Academic freedom has become a polarizing topic . Recent issues at the University of Ottawa expose ongoing challenges of balancing academic freedom with university community members’ rights to respectful and safe classroom and campus spaces.

In October 2021, the university’s Committee on Academic Freedom issued a report that examined academic freedom, freedom of expression, equity, diversity and inclusion — and the legal aspects of these issues.

This work was set in motion after controversy surrounding a professor who used a derogatory word for Black people in class .

The committee’s report, and wider commentary about the University of Ottawa controversy , point to the need for greater public discussion to understand how academic freedom relates to responsibility.

As a PhD researcher who examines structural and systematic racism embedded in social institutions, including in education systems, I believe it’s critical to consider failures to understand academic freedom as an ethical concept, rather than simply a neutral objective standard .

Role of responsibilities, ethics in freedom

At universities, faculty collective agreements and university policies spell out frameworks for academic freedom.

But as University of Ottawa’s Committee on Academic Freedom noted, universities’ definitions and policies vary, sometimes significantly, in the ways they spell out wider rights, responsibilities, obligations and limits — or how academic freedom relates with equity , diversity or ethics.

The University of British Columbia distinguishes between freedom of expression — protected in Canada under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms — and academic freedom in an FAQ about these issues on the university website:

“Most significantly, academic freedom is not a legal right, but rather a right or a privilege bestowed by an institution of higher learning. It might best be construed as an ethical right, insofar as it serves good ends: the advancement and dissemination of knowledge .”

When speakers seek to responsibly disseminate knowledge, they must be aware of who they’re speaking to, and how what they’re saying may resonate.

Power and privilege

In October 2020, after the University of Ottawa classroom incident, Québec Premier François Legault criticized the university for suspending the professor at the centre of the issue.

As a fully bilingual university close to the Québec border, the University of Ottawa has close connections with the province.

At a news conference, the premier said, “I don’t think there should be banned words,” and “It’s as if [the university] has … censure police.”

The premier’s comments illustrated power and privilege. Their wider related effects, including discussion around Québec’s commission to study academic freedom , have added to the division among professors and students at the University of Ottawa.

Harms to students

In its report, the University of Ottawa’s Academic Freedom Committee made several recommendations, including:

further work to ensure the university community has a wider understanding of principles of academic freedom;

clear criteria and mechanisms are needed for making complaints;

university administration should establish an action plan to fight racism, discrimination and cyberbullying;

affirming “the need to protect academic freedom and freedom of expression in fulfilment of its teaching and research mission.” The committee said it’s against “institutional or self-censorship that is apt to compromise the dissemination of knowledge or is motivated by fear of public repudiation.”

I’m specifically concerned about what this last point will mean, especially given that the report’s recommendations don’t address how professors need to demonstrate self-awareness of their own social positions in how they exercise responsibility.

More discussion is needed about how power shapes identities and access to learning. Communities also need to consider students who experience moral injury when people use irresponsible language and are unaccountable for their privilege.

In June 2021, the Black, Indigenous and People of Colour Professors & Librarians Caucus Working Group at the University of Ottawa made a submission to Committee on Academic Freedom. It stressed that notions of academic freedom cannot be divorced from respect for dignity and integrity in the classroom . This caucus also made ample suggestions about practical ways to urgently tackle systemic racism at the university. This is necessary for creating safer spaces for all community members.

Confronting ‘colonial nostalgia’

Academics concerned about academic freedom and the quality of education note that academic freedom needs to be concerned with the quality of speech and the context in which it’s uttered.

As interdisciplinary scholar Farhana Sultana argues, some academics participate in the erosion of academic integrity when they apply “scholarly” veneer to hateful ideologies. She writes:

“At a time when there are concerted efforts to decolonize academia, there is concurrent rise of colonial nostalgia and white supremacy among some academics, who are supported by and end up lending support to the escalating far-right movements.”

To fully and freely engage in dialogue in the classrooms, professors must recognize different aspects of their identities such as race, gender, sexuality, language — and consider how what they say may resonate among varied groups.

Safe spaces, brave spaces

Educators seeking to balance the need for sincere and challenging dialogue and responsibility have explored the notion of moving from safe spaces to “brave spaces .”

Read more: 4 ways white people can be accountable for addressing anti-Black racism at universities

In the article, “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice,” student affairs educators Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens define safe space as “a learning environment that allows students to engage with one another over controversial issues with honesty, sensitivity and respect.” They also explore how the notion of safety can become conflated with comfort.

Arao and Clemens argue that education about difficult issues may be shocking and uncomfortable, but it’s possible to do so in respectful ways through social justice teaching practices that foster diversity and inclusion. Other researchers have developed these ideas further .

There is an ethical responsibility by professors to provide space for challenging discussions. This necessarily includes not perpetrating old structures that were built on casting out marginalized groups. Professors have a responsibility not to humiliate racialized students or use racist or discriminatory language.

New teaching, training standards needed

Standards of ethical and professional behaviour have progressed, and the practice of academic freedom should adapt.

As anti-racist and feminist scholar bell hooks also argued, what’s needed is learning how to teach students to transgress against racial and class boundaries that promote white supremacy or a hierarchy of human dignity .

I remain hopeful that with ongoing collaborative engagement from administrators and policy-makers, change will occur in our educational system.

- Free speech

- Academic freedom

- Safe Spaces

- Critical race

- Anti-Black racism

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Rights and Responsibilities

In order to enjoy ou

Guiding Questions

- What is a right?

- What is a responsibility?

- What responsibilities are natural byproducts of the rights we enjoy?

- How does exercising our rights and fulfilling our responsibilities help to promote the common good for all?

- Students will differentiate rights from responsibilities.

- Students will analyze the relationship between rights and responsibilities.

- Students will explain how rights and responsibilities are related to the common good.

Expand Materials Materials

Educator Resources

- Handout A and B Answer Keys

- Rights and Responsibilities Slips

Student Handouts

- Rights and Responsibilities Essay

Handout A: How Does the Constitution Protect Liberty?

- Handout B: Excerpts from Federalist No. 10, 51, 55, and 57

- U.S. Constitution

Expand Key Terms Key Terms

- responsibilities

- common good

Expand Prework Prework

Have students read Rights and Responsibilities Essay for homework. (20 minutes)

Prior to class time, print and cut apart the Rights and Responsibilities Slips .

Students will need copies of the U.S. Constitution .

Expand Warmup Warmup

Ask the class, What is a right? What is a responsibility?

After students briefly discuss these questions, give each student one or more of the Rights and Responsibilities Slips . Students work in pairs or small groups to help one another decide which category each slip belongs in: Rights or Responsibilities.

After students have worked on the task for a few minutes, ask the class if there were any items that were difficult to classify and why. Designate a container for Rights on one side of the room and another container for Responsibilities on the other. Have students get up from their desks to place each of their slips of paper in the container they have chosen. Ultimately the person who received each slip has the final authority to decide where it goes.

Expand Activities Activities

Work with the class as a whole to develop a list of rights protected by the U.S. Constitution. Students skim Amendments 1 – 8 of the Bill of Rights. Make a class list of all the rights listed. Discuss how Amendments 9 and 10 apply to the idea of rights. Have one group of students quickly skim Amendments 11- 27, and contribute to the class list of rights. Have another group quickly skim Articles 1 – 7 of the U.S. Constitution to find individual rights, and add to the list of rights.

Have students work in small groups to read Handout A: How Does the Constitution Protect Liberty? , and to discuss the questions at the end of the handout. Invite groups to share their responses to the Comprehension and Critical Thinking Questions.

In whole-class discussion, pick several rights. Ask what action would be required of citizens to exercise that right responsibly. For example, students should naturally discuss voting. Ask whether that is a right or responsibility, and discuss how to participate in the act of voting responsibly. Examples might be keeping up with current events and learning about a candidate’s positions and actions with respect to public affairs and current issues. Free speech: What responsibilities are implied when you wish to exercise your freedom of speech? Examples might be listening respectfully to others and protecting the right to free speech for those who hold unpopular opinions. Continue as time permits with other rights/responsibilities that students may suggest. Conclude by asking, What characteristics of citizens are necessary for republican self-government to be just and to promote the common good?

Have students work in small groups to read Handout B, Excerpts of Federalist Papers No. 10, 51, 55, and 57 , regarding responsibilities of republican government. Discuss the questions provided.

Expand Wrap Up Wrap Up

Develop a classroom definition of “common good” that most can agree upon.

According to Dictionary.com, Common good is “the advantage or benefit of all people in society or in a group.”

Ask, How are rights and responsibilities related to the common good? When we insist upon, and exercise, our inalienable rights, to whom are we responsible? How can exercising our liberties benefit the common good?

Expand Homework Homework

Write a 2-3 paragraph response: How can you be a good citizen and contribute to the common good while exercising your rights and fulfilling your responsibilities? Give concrete examples.

Expand Extensions Extensions

Go back to your original sorting sheet where you divided rights and responsibilities into categories. Which items are both? Is the sorting more or less difficult after this lesson?

Handout B: Excerpts from Federalist No 10, 51, 55, and 57

Next Lesson

Diversity as an American Value

Related resources.

The Constitution

The Constitution was written in the summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by delegates from 12 states, in order to replace the Articles of Confederation with a new form of government. It created a federal system with a national government composed of 3 separated powers, and included both reserved and concurrent powers of states.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Rights and Responsibilities

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 183381

Democracies rest upon the principle that government exists to serve the people. In other words, the people are citizens of the democratic state, not its subjects. Because the state protects the rights of its citizens, they, in turn, give the state their loyalty. Under an authoritarian system, by contrast, the state demands loyalty and service from its people without any reciprocal obligation to secure their consent for its actions.

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

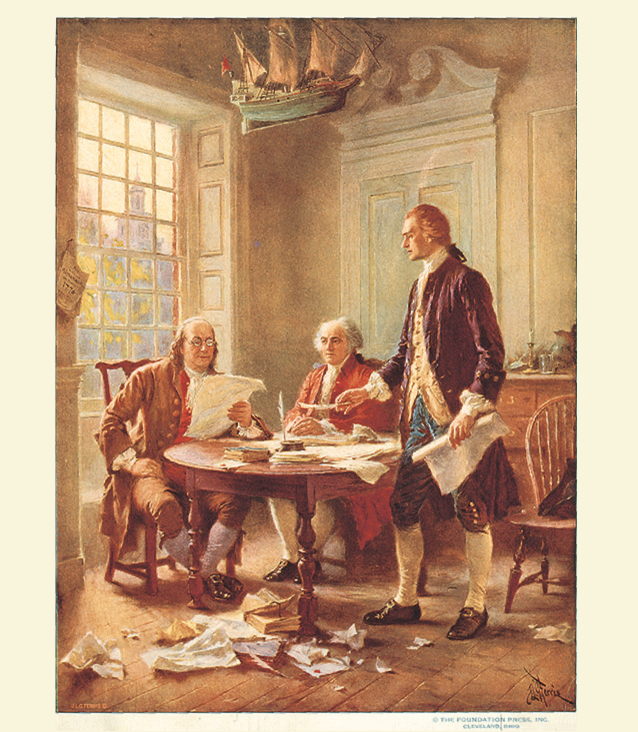

This relationship of citizen and state is fundamental to democracy. In the words of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson in 1776:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

More specifically, in democracies, these fundamental or inalienable rights include freedom of speech and expression, freedom of religion and conscience, freedom of assembly, and the right to equal protection before the law. This is by no means an exhaustive list of the rights that citizens enjoy in a democracy, but it does constitute a set of the irreducible core rights that any democratic government worthy of the name must uphold. Since they exist independently of government, in Jefferson’s view, these rights cannot be legislated away, nor should they be subject to the whim of an electoral majority.

SPEECH, ASSEMBLY, AND PROTEST

Freedom of speech and expression, especially about political and social issues, is the lifeblood of any democracy. Democratic governments do not control the content of most written and verbal speech. Thus democracies are usually filled with many voices expressing different or even contrary ideas and opinions. Democracies tend to be noisy.

Democracy depends upon a literate, knowledgeable citizenry whose access to information enables it to participate as fully as possible in the public life of society and to criticize unwise or oppressive government officials or policies. Citizens and their elected representatives recognize that democracy depends upon the widest possible access to uncensored ideas, data, and opinions. For a free people to govern themselves, they must be free to express themselves—openly, publicly, and repeatedly—in speech and in writing.

The protection of free speech is a so-called "negative right," simply requiring that the government refrain from limiting speech. For the most part, the authorities in a democracy are uninvolved in the content of written and verbal speech.

Protests serve as a testing ground for any democracy—thus the right to peaceful assembly is essential and plays an integral part in facilitating the use of free speech. A civil society allows for spirited debate among those in disagreement over the issues. In the modern United States, even fundamental issues of national security, war, and peace are discussed freely in newspapers and in broadcast media, with those opposed to the administration’s foreign policy easily publicizing their views.

Freedom of speech is a fundamental right, but it is not absolute, and cannot be used to incite violence. Slander and libel, if proven, are usually defined and controlled through the courts. Democracies generally require a high degree of threat to justify banning speech or gatherings that may incite violence, untruthfully harm the reputation of others, or overthrow a constitutional government. Many democracies ban speech that promotes racism or ethnic hatred. The challenge for all democracies, however, is one of balance: to defend freedom of speech and assembly while countering speech that truly encourages violence, intimidation, or subversion of democratic institutions. One can disagree forcefully and publicly with the actions of a public official; calling for his (or her) assassination, however, is a crime.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND TOLERANCE

All citizens should be free to follow their conscience in matters of religious faith. Freedom of religion includes the right to worship alone or with others, in public or private, or not to worship at all, and to participate in religious observance, practice, and teaching without fear of persecution from government or other groups in society. All people have the right to worship or assemble in connection with a religion or belief, and to establish and maintain places for these purposes.

Like other fundamental human rights, religious freedom is not created or granted by the state, but all democratic states should protect it. Although many democracies may choose to recognize an official separation of church and state, the values of government and religion are not in fundamental conflict. Governments that protect religious freedom for all their citizens are more likely to protect other rights necessary for religious freedom, such as free speech and assembly. The American colonies, virtually theocratic states in the 17th and 18th centuries, developed theories of religious tolerance and secular democracy almost simultaneously. By contrast, some of the totalitarian dictatorships of the 20th century attempted to wipe out religion, seeing it (rightly) as a form of self-expression by the individual conscience, akin to political speech. Genuine democracies recognize that individual religious differences must be respected and that a key role of government is to protect religious choice, even in cases where the state sanctions a particular religious faith. However, this does not mean that religion itself can become an excuse for violence against other religions or against society as a whole. Religion is exercised within the context of a democratic society but does not take it over.

CITIZEN RESPONSIBILITIES

Citizenship in a democracy requires participation, civility, patience—rights as well as responsibilities. Political scientist Benjamin Barber has noted, "Democracy is often understood as the rule of the majority, and rights are understood more and more as the private possessions of individuals. ... But this is to misunderstand both rights and democracy." For democracy to succeed, citizens must be active, not passive, because they know that the success or failure of the government is their responsibility, and no one else’s.

It is certainly true that individuals exercise basic rights—such as freedom of speech, assembly, religion—but in another sense, rights, like individuals, do not function in isolation. Rights are exercised within the framework of a society, which is why rights and responsibilities are so closely connected.

Democratic government, which is elected by and accountable to its citizens, protects individual rights so that citizens in a democracy can undertake their civic obligations and responsibilities, thereby strengthening the society as a whole.

At a minimum, citizens should educate themselves about the critical issues confronting their society, if only so that they can vote intelligently. Some obligations, such as serving on juries in civil or criminal trials or in the military, may be required by law, but most are voluntary.

The essence of democratic action is the peaceful, active, freely chosen participation of its citizens in the public life of their community and nation. According to scholar Diane Ravitch, "Democracy is a process, a way of living and working together. It is evolutionary, not static. It requires cooperation, compromise, and tolerance among all citizens. Making it work is hard, not easy. Freedom means responsibility, not freedom from responsibility." Fulfilling this responsibility can involve active engagement in organizations or the pursuit of specific community goals; above all, fulfillment in a democracy involves a certain attitude, a willingness to believe that people who are different from you have similar rights.

- THE ETHICS INSTITUTE

- Putting ethics at the centre of everyday life.

- LIVING OUR ETHICS

- ANNUAL REPORTS

- Articles, podcasts, videos, research & courses tackling the issues that matter.

- WHAT IS ETHICS?

- Events and interactive experiences exploring ethics of being human.

- UPCOMING EVENTS

- PAST EVENTS

- PAST SPEAKERS

- FESTIVAL OF DANGEROUS IDEAS

- Counselling and bespoke consulting programs to help you make better decisions and navigate complexity.

- CONSULTING & LEADERSHIP

- Our work is only made possible because of you. Join us!

- BECOME A MEMBER

- SUPPORT OUR WORK

- THE ETHICS ALLIANCE

- BANKING + FINANCIAL SERVICES OATH

- RESIDENCY PROGRAM

- YOUNG WRITERS’ COMPETITION

- YOUTH ADVISORY COUNCIL

- ENGAGE AN EXPERT

- MEDIA CENTRE

- HIRE OUR SPACE

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Explainer politics + human rights, by the ethics centre 2 jun 2017, when you have a right either to do or not do something, it means you are entitled to do it or not..

Rights are always about relationships. If you were the only person in existence, rights wouldn’t be relevant at all. This is why rights always correspond to responsibilities. My rights will limit the ways you can and can’t behave towards me.

Legal philosopher Wesley Hohfeld distinguished between two sets of rights and responsibilities. First, there are claims and duties. Your right to life is attached to everyone else’s duty not to kill you. You can’t have one without the other.

Second, there are liberties and no-claims. If I’m at liberty to raise my children as I see fit it’s because there’s no duty stopping me – nobody can make a claim to influence my actions here. If we have no claim over other people’s liberties, our only duty is not to interfere with their behaviour.

But your liberty disappears as soon as someone has a claim against you. For example, you’re at liberty to move freely until someone else has a claim to private property. Then you have a duty not to trespass on their land.

It’s useful to add into the mix the distinction between positive and negative rights. If you have a positive right, it creates a duty for someone to give you something – like an education. If you have a negative right, it means others have a duty not to treat you in some way – like assaulting you.

All this might seem like tedious academic stuff but it has real world consequences. If there’s a positive right to free speech, people need to be given opportunities to speak out. For example, they might need access to a radio program so they can be heard.

By contrast, if it’s a negative claim right, nobody can censor anyone else’s speech. And if free speech is a liberty, your right to use it is subject to the claims of other. So if other people claim the right not to be offended, for example, you may not be able to speak up.

There are a few reasons why rights are a useful concept in ethics .

First, they are easy to enforce through legal systems. Once we know what rights and duties people have, we can enshrine them in law.

Second, rights and duties protect what we see as most important when we can’t trust everyone will act well all the time. In our imperfect world, rights provide a strong language to influence people’s behaviour.

Finally, rights capture the central ethical concepts of dignity and respect for persons. As the philosopher Joel Feinberg writes:

Having rights enables us to “stand up like men,” to look others in the eye, and to feel in some fundamental way the equal of anyone. To think of oneself as the holder of rights is not to be unduly but properly proud, to have that minimal self-respect that is necessary to be worthy of the love and esteem of others.

Indeed, respect for persons […] may simply be respect for their rights, so that there cannot be the one without the other; and what is called “human dignity” may simply by the recognizable capacity to assert claims.

Feinberg suggests rights are a manifestation of who we are as human beings. They reflect our dignity, autonomy and our equal ethical value. There are other ways to give voice to these things, but in highly individualistic cultures, what philosophers call “rights talk” resonates for two reasons: individual freedom and equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

- Everyday Ethics Monthly

- Professional Ethics Quarterly

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

Ethics explainer: testimonial injustice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The ethics centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life..

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Human Rights: Samples in 500 and 1500

- Updated on

- Dec 9, 2023

Essay writing is an integral part of the school curriculum and various academic and competitive exams like IELTS , TOEFL , SAT , UPSC , etc. It is designed to test your command of the English language and how well you can gather your thoughts and present them in a structure with a flow. To master your ability to write an essay, you must read as much as possible and practise on any given topic. This blog brings you a detailed guide on how to write an essay on Human Rights , with useful essay samples on Human rights.

This Blog Includes:

The basic human rights, 200 words essay on human rights, 500 words essay on human rights, 500+ words essay on human rights in india, 1500 words essay on human rights, importance of human rights, essay on human rights pdf.

Also Read: List of Human Rights Courses

Also Read: MSc Human Rights

Also Read: 1-Minute Speech on Human Rights for Students

What are Human Rights

Human rights mark everyone as free and equal, irrespective of age, gender, caste, creed, religion and nationality. The United Nations adopted human rights in light of the atrocities people faced during the Second World War. On the 10th of December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Its adoption led to the recognition of human rights as the foundation for freedom, justice and peace for every individual. Although it’s not legally binding, most nations have incorporated these human rights into their constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. Human rights safeguard us from discrimination and guarantee that our most basic needs are protected.

Did you know that the 10th of December is celebrated as Human Rights Day ?

Before we move on to the essays on human rights, let’s check out the basics of what they are.

Also Read: What are Human Rights?

Also Read: 7 Impactful Human Rights Movies Everyone Must Watch!

Here is a 200-word short sample essay on basic Human Rights.

Human rights are a set of rights given to every human being regardless of their gender, caste, creed, religion, nation, location or economic status. These are said to be moral principles that illustrate certain standards of human behaviour. Protected by law , these rights are applicable everywhere and at any time. Basic human rights include the right to life, right to a fair trial, right to remedy by a competent tribunal, right to liberty and personal security, right to own property, right to education, right of peaceful assembly and association, right to marriage and family, right to nationality and freedom to change it, freedom of speech, freedom from discrimination, freedom from slavery, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of movement, right of opinion and information, right to adequate living standard and freedom from interference with privacy, family, home and correspondence.

Also Read: Law Courses

Check out this 500-word long essay on Human Rights.

Every person has dignity and value. One of the ways that we recognise the fundamental worth of every person is by acknowledging and respecting their human rights. Human rights are a set of principles concerned with equality and fairness. They recognise our freedom to make choices about our lives and develop our potential as human beings. They are about living a life free from fear, harassment or discrimination.

Human rights can broadly be defined as the basic rights that people worldwide have agreed are essential. These include the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom from torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the right to health, education and an adequate standard of living. These human rights are the same for all people everywhere – men and women, young and old, rich and poor, regardless of our background, where we live, what we think or believe. This basic property is what makes human rights’ universal’.

Human rights connect us all through a shared set of rights and responsibilities. People’s ability to enjoy their human rights depends on other people respecting those rights. This means that human rights involve responsibility and duties towards other people and the community. Individuals have a responsibility to ensure that they exercise their rights with consideration for the rights of others. For example, when someone uses their right to freedom of speech, they should do so without interfering with someone else’s right to privacy.

Governments have a particular responsibility to ensure that people can enjoy their rights. They must establish and maintain laws and services that enable people to enjoy a life in which their rights are respected and protected. For example, the right to education says that everyone is entitled to a good education. Therefore, governments must provide good quality education facilities and services to their people. If the government fails to respect or protect their basic human rights, people can take it into account.

Values of tolerance, equality and respect can help reduce friction within society. Putting human rights ideas into practice can help us create the kind of society we want to live in. There has been tremendous growth in how we think about and apply human rights ideas in recent decades. This growth has had many positive results – knowledge about human rights can empower individuals and offer solutions for specific problems.

Human rights are an important part of how people interact with others at all levels of society – in the family, the community, school, workplace, politics and international relations. Therefore, people everywhere must strive to understand what human rights are. When people better understand human rights, it is easier for them to promote justice and the well-being of society.

Also Read: Important Articles in Indian Constitution

Here is a human rights essay focused on India.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It has been rightly proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Created with certain unalienable rights….” Similarly, the Indian Constitution has ensured and enshrined Fundamental rights for all citizens irrespective of caste, creed, religion, colour, sex or nationality. These basic rights, commonly known as human rights, are recognised the world over as basic rights with which every individual is born.