Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary? Argumentative Essay

Introduction, works cited.

The role of the American Revolution in history seems to be great indeed: in spite of the fact that some historians define it as a successful American attempt to reject the ideas set by the British government, this event has much more significant aspects and impacts on human lives.

By its nature, a revolution is an effort to change something in order to improve the conditions under which people have to live; it is a change from one constitution to another; it is a beginning of the way that should considerably improve everything. In fact, such definitions are close to those offered by Gordon Wood and Howard Zinn.

These writers made effective attempts to define the nature of the American Revolution as well as to help the reader build a personal opinion.

The nature of the American Revolution is considered to be better understandable relying on the ideas offered by Wood because one of the main purposes which should be achieved are connected with an idea of radical ideological change so strongly supported by Wood:

The Americans did not want to follow the rules dictated by the British people but to create their own constitution and live in accordance with their own demands; and Zinn’s approach based on the material needs is poorer as the results of the American Revolution did not prevent the development of poverty but spread it on the American citizens only regarding British interruptions.

To understand whether the American Revolution was really revolutionary, it is necessary to comprehend the essence of each word in this phrase. The idea of revolution is certainly based on some changes to be achieved. The main goal of the Americans was to gain independence from the British Empire and to become a powerful country in the world.

The results of this revolution were all about American independence and the improvements of living conditions for American people, in other words, it was obligatory to decrease the poverty rates. However, the methods and purposes set during the revolution deserve more attention to be paid. There was a necessity to compare the American and British styles of life (Wood).

Americans were eager to defend their rights as well as to prove their liberty out of the British Empire. What they achieved was the possibilities to develop manufacturing, to establish their own government, to expand any kind of religion, and to vote relying on their own interests.

Wood and Zinn evaluate these achievements from different perspectives: Wood’s ideas seem to be more radical, and Zinn’s ideas are regarded as conservative ones to protect wealth of the country.

As it has been mentioned above, Wood’s approach is based on the radical ideas according to which a revolution presupposes an idea of an ideological shift under which human rights may be recovered and salvation of liberty will be achieved.

He tries to explain that changes which have been achieved influenced considerably the relations between Americans as well as between family members and even between the governmental representatives (Wood).

Zinn, in his turn, focuses on the material backgrounds which are inherent to people: as there is a considerable extent of rich and poor people, supporters of the revolution should get the right to have the same opportunities and develop their knowledge.

The main achievements of Americans were based on the creation of the Constitution under the conditions of which people should be divided again into the representative of the elite and those members of the middle class. The point is that Zinn is more attentive to the examples from the history to support his position. However, the simple facts used are not as possible as the sophisticated arguments offered by Wood.

The language of the American Revolution is based on rebellions, burdens, and attacks which made people be united for some period of time only in order to win the enemy (Zinn). This is why it was more important to concentrate on the moral or even ideological dimension that should lead to the required political separation (Wood).

So, the evaluation of the American Revolution and the attention to the approaches offered by Wood and Zinn help to comprehend a true essence of the event under analysis. Wood’s approach concerning the ideological shift of the conditions defines a revolutionary nature of the events which took place at the end of the 18 th century. Americans were in need of being separated from the tyranny of the British Empire.

Their main purpose was all about separation and independence, and the elimination of poverty among people should be considered as an additional outcome. Wood’s definition of the revolution seems to be correct; however, at the same time, it is wrong to say that Zinn’s attempt was not correct, it is better to admit that his idea was not as powerful and persuasive as the one of Wood is.

In general, the success of Wood’s argumentation of the American Revolution and its nature helps to understand that this event played a very important role in the American history. People should realize that during that period of time, Americans made one of the most powerful and influential attempts to prove their dignity, their rights, and possibilities.

It was possible to achieve the desirable success only by means of the ideological shift described by Wood, and Zinn’s ideas are focused on the consequences which may be observed after the revolution was over.

Still, the American Revolution changed American society considerably and make Americans more confident in personal powers and abilities to change ideologies and follow their own interests to become one of the largest and the richest countries in the whole world.

Wood, Gordon. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, Random House Publishing Group, 2002. Print.

Zinn, Howard. “ Tyranny is Tyranny .” In A People’s History of the United States. History Is a Weapon . n.d. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 5). Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary? https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-american-revolution-really-revolutionary/

"Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary?" IvyPanda , 5 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-american-revolution-really-revolutionary/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary'. 5 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary?" February 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-american-revolution-really-revolutionary/.

1. IvyPanda . "Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary?" February 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-american-revolution-really-revolutionary/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary?" February 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/was-the-american-revolution-really-revolutionary/.

- Congressman Grijalva and Howard Zinn

- “We Take Nothing by Conquest Thank God” by Howard Zinn

- "Columbus, the Indians, and Human Progress" by H. Zinn

- Zinn’s and Schweikart’s Beliefs on American Democracy

- Social Issues in Self Help in Hard Times by Zinn

- New Deal and Cost of Wars in American History

- Anglos and Mexicans in the Twenty First Century

- Arguments of American History: Various Events

- Human Rights: Analysis of Ludlow Massacre and the “Valour and the Horror”

- European Expansionism: Columbus, Arawaks, and Aztecs

- American Revolutionary War: Causes and Outcomes

- History of the American Revolutionary War

- Road to Revolution

- The American Revolution and Its Effects

- Causes of Revolutionary War in America

Essay on How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution

Students are often asked to write an essay on How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution

Introduction to the american revolution.

The American Revolution was a big change where 13 British colonies in North America fought for and won their freedom. This event is important because it led to the creation of the United States.

Changes in Government

The Revolution introduced a new form of government. Instead of a king, the United States would have presidents. The power would come from the citizens.

Impact on Society

The war also changed society. It challenged the class system and increased the desire for equal rights, although this took a long time to achieve.

Global Influence

The success in America inspired other countries to fight for their own freedom, making the revolution a model for others.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was truly revolutionary because it created a new nation, inspired global changes, and reshaped society.

250 Words Essay on How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution

The American Revolution was a big event in history. It happened between 1765 and 1783. People in the thirteen colonies in North America wanted to be free from British rule. They were tired of paying taxes to a country far away without having a say in the government.

Change in Rule

One major change was who made the rules. Before the revolution, Britain made the laws for the colonies. After the revolution, the American people started to make their own laws. This was a big step towards being a free country.

The revolution also introduced new ideas. It talked about freedom and that all people should have rights. These ideas were new and exciting for the people at that time.

The revolution changed society too. It was not just the rich or the powerful who were important. Regular people, like farmers and shopkeepers, started to have a voice in how the country was run.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was quite revolutionary. It changed the way the country was governed, introduced new ideas about freedom and rights, and allowed more people to participate in politics. It was a big step towards the United States becoming a country with its own identity and government.

500 Words Essay on How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution

The American Revolution was a big change in history. It happened from 1775 to 1783 when the 13 American colonies fought against British rule to become their own country, the United States of America. This event was not just a war; it changed how people thought and lived. Let’s look at how this revolution was a major shift in ideas, politics, and society.

The Fight for Independence

First, the American Revolution was about gaining freedom from Britain. The colonists did not want to follow British laws and pay taxes to a king across the ocean. They wanted to make their own rules. When they won the war, they became free to govern themselves. This was a big step because it showed that a group of colonies could stand up to a powerful country and win.

Changes in Thinking

The revolution was also revolutionary in how it changed people’s minds. Before the war, many people believed that kings had the right to rule because God chose them. But the Americans started to think that people should have the right to choose their own leaders. They believed in “no taxation without representation,” which means people should only pay taxes if they have a say in making the laws. This idea was very new and changed how governments worked.

New Government and Laws

Another big change was the kind of government the Americans made after the revolution. They wrote the United States Constitution, which is like a big plan for how the government should work. It said that the government’s power comes from the people, not a king. It also protected the rights of the people, like freedom of speech and religion. This was a new way to think about government, and it inspired other countries later on.

The revolution also changed society. It made some people think more about freedom and equality. While not everyone was treated equally right away, the ideas of the revolution started discussions about ending slavery and giving more rights to women and other groups. These talks would lead to more changes in the future.

Not Revolutionary for Everyone

It’s important to remember that the revolution did not change everything. For many people, life stayed the same. Slaves were still not free, and women and Native Americans did not have the same rights as white men. So, for some people, the revolution was not very revolutionary.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was a big change in many ways. It helped the American colonies become a free country with new ideas about government and rights. It made people think differently about who should have power and why. But it was not a complete change for everyone, and it took many more years for all people in America to be treated fairly. The revolution started a process of change that would grow and develop long after the war was over.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Ozone Layer Protection

- Essay on How We Can Achieve The Common Good

- Essay on Overthinking

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Advertisement

Why Was the American Revolution So Revolutionary?

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Several aspects of the American Revolution could qualify it as revolutionary. First, guerilla warfare played a major role in the war for independence, replacing the pitched battle of earlier periods. Second, the revolution took place outside the borders of its parent nation, which makes the American Revolution remarkable compared to something like the French Revolution .

But what really made the American Revolution so revolutionary was that it didn't end in a regime change only, but in the creation of an entirely new nation founded on democratic principles.

Does that mean that the United States was the world's first democracy? No. In fact, the U.S. government isn't a direct democracy, in which the people themselves vote on the nation's policies and spending budgets, but a representative democracy. In a representative democracy, also known as a republic, the people elect representatives who conduct the nation's business.

The Greek city-state of Athens was one of the world's first direct democracies, and the Roman Republic was the first representative democracy in history, dating from 509 B.C.E. to 27 B.C.E. [sources: Hauer , National Geographic Society ]. Even though it wasn't the first democratic experiment in history, the American Revolution was still considered revolutionary (even radical) in its time, especially when compared to the most powerful European nations of the day, which continued to be ruled by old-world monarchs and wealthy aristocrats.

Historians have vigorously debated how the American Revolution gave rise to democracy. Some see the revolution as a struggle for self-government; others see it as a class struggle that erupted in violence [source: McManus ]. Whatever its origins – and a number of competing and cooperative factors created it – the American Revolution in fact did create a new, democratic nation.

Certainly, the concepts that Thomas Jefferson included in the Declaration Independence – that "all men are created equal," and that government derives its power from the "consent of the governed" – were revolutionarily democratic ideals [source: National Archives ]. Yet it wasn't until the ratification of the Constitution more than a decade later in 1789 that the democratic principles of the new nation were put into practice. Without the Constitution, the document that guaranteed the protection of civil rights and the restraints put on the state, the democracy birthed by the Declaration would have existed only in rhetoric.

Other historians have argued that American democracy wasn't truly born until 1796, when George Washington voluntarily stepped down after two terms as America's first president [source: Stromberg ]. It marked the first peaceful transfer of power in the new nation and set a precedent that American presidents weren't leaders for life, but regularly elected by the will of the people.

A strong case can also be made that the most revolutionary aspects of the American Revolution — lofty democratic ideals of equality and full representation — were obtained through a slow evolution rather than a one-time revolution. American democracy may have been born in the 18th century, but that was a "democracy" in which only white men had the right the vote. Only after the eradication of slavery, the extension of voting rights to African-American men and all women, and the passing of Civil Rights legislation barring discriminatory poll taxes and citizenship tests, could America rightfully call itself a democracy.

Lots More Information

Related articles.

- Who was the Swamp Fox?

- Did Betsy Ross really make the first American flag?

- What happened to the other two men on Paul Revere's ride?

- The War of 1812: The White House Burns and 'The Star Spangled Banner is Born'

- Hauer, Sarah. "Paul Ryan claims the U.S. is the oldest democracy in the world. Is he right?" Politifact. July 11, 2016 https://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2016/jul/11/paul-ryan/paul-ryan-claims-us-oldest-democracy-world-he-righ/

- McManus, John C. "How historians view the American Revolution." For Dummies. (Sept. 24, 2010) .http://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/how-historians-view-the-american-revolution.html

- National Archives. "Declaration of Independence." Sept. 24, 2010. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_transcript.html

- National Geographic Society. "Roman Republic." July 6, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/roman-republic/

- Stromberg, Joseph. "The Real Birth of American Democracy." Smithsonian Magazine. Sept. 20, 2011 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/the-real-birth-of-american-democracy-83232825/

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Revolutionary War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

The Revolutionary War (1775-83), also known as the American Revolution, arose from growing tensions between residents of Great Britain’s 13 North American colonies and the colonial government, which represented the British crown.

Skirmishes between British troops and colonial militiamen in Lexington and Concord in April 1775 kicked off the armed conflict, and by the following summer, the rebels were waging a full-scale war for their independence.

France entered the American Revolution on the side of the colonists in 1778, turning what had essentially been a civil war into an international conflict. After French assistance helped the Continental Army force the British surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, the Americans had effectively won their independence, though fighting did not formally end until 1783.

Causes of the Revolutionary War

For more than a decade before the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, tensions had been building between colonists and the British authorities.

The French and Indian War , or Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), brought new territories under the power of the crown, but the expensive conflict lead to new and unpopular taxes. Attempts by the British government to raise revenue by taxing the colonies (notably the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767 and the Tea Act of 1773) met with heated protest among many colonists, who resented their lack of representation in Parliament and demanded the same rights as other British subjects.

Colonial resistance led to violence in 1770, when British soldiers opened fire on a mob of colonists, killing five men in what was known as the Boston Massacre . After December 1773, when a band of Bostonians altered their appearance to hide their identity boarded British ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party , an outraged Parliament passed a series of measures (known as the Intolerable, or Coercive Acts ) designed to reassert imperial authority in Massachusetts .

Did you know? Now most famous as a traitor to the American cause, General Benedict Arnold began the Revolutionary War as one of its earliest heroes, helping lead rebel forces in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775.

In response, a group of colonial delegates (including George Washington of Virginia , John and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts, Patrick Henry of Virginia and John Jay of New York ) met in Philadelphia in September 1774 to give voice to their grievances against the British crown. This First Continental Congress did not go so far as to demand independence from Britain, but it denounced taxation without representation, as well as the maintenance of the British army in the colonies without their consent. It issued a declaration of the rights due every citizen, including life, liberty, property, assembly and trial by jury. The Continental Congress voted to meet again in May 1775 to consider further action, but by that time violence had already broken out.

On the night of April 18, 1775, hundreds of British troops marched from Boston to nearby Concord, Massachusetts in order to seize an arms cache. Paul Revere and other riders sounded the alarm, and colonial militiamen began mobilizing to intercept the Redcoats. On April 19, local militiamen clashed with British soldiers in the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, marking the “shot heard round the world” that signified the start of the Revolutionary War.

HISTORY Vault: The Revolution

From the roots of the rebellion to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, explore this pivotal era in American history through sweeping cinematic recreations.

Declaring Independence (1775-76)

When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia, delegates—including new additions Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson —voted to form a Continental Army, with Washington as its commander in chief. On June 17, in the Revolution’s first major battle, colonial forces inflicted heavy casualties on the British regiment of General William Howe at Breed’s Hill in Boston. The engagement, known as the Battle of Bunker Hill , ended in British victory, but lent encouragement to the revolutionary cause.

Throughout that fall and winter, Washington’s forces struggled to keep the British contained in Boston, but artillery captured at Fort Ticonderoga in New York helped shift the balance of that struggle in late winter. The British evacuated the city in March 1776, with Howe and his men retreating to Canada to prepare a major invasion of New York.

By June 1776, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, a growing majority of the colonists had come to favor independence from Britain. On July 4 , the Continental Congress voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence , drafted by a five-man committee including Franklin and John Adams but written mainly by Jefferson. That same month, determined to crush the rebellion, the British government sent a large fleet, along with more than 34,000 troops to New York. In August, Howe’s Redcoats routed the Continental Army on Long Island; Washington was forced to evacuate his troops from New York City by September. Pushed across the Delaware River , Washington fought back with a surprise attack in Trenton, New Jersey , on Christmas night and won another victory at Princeton to revive the rebels’ flagging hopes before making winter quarters at Morristown.

Saratoga: Revolutionary War Turning Point (1777-78)

British strategy in 1777 involved two main prongs of attack aimed at separating New England (where the rebellion enjoyed the most popular support) from the other colonies. To that end, General John Burgoyne’s army marched south from Canada toward a planned meeting with Howe’s forces on the Hudson River . Burgoyne’s men dealt a devastating loss to the Americans in July by retaking Fort Ticonderoga, while Howe decided to move his troops southward from New York to confront Washington’s army near the Chesapeake Bay. The British defeated the Americans at Brandywine Creek, Pennsylvania , on September 11 and entered Philadelphia on September 25. Washington rebounded to strike Germantown in early October before withdrawing to winter quarters near Valley Forge .

Howe’s move had left Burgoyne’s army exposed near Saratoga, New York, and the British suffered the consequences of this on September 19, when an American force under General Horatio Gates defeated them at Freeman’s Farm in the first Battle of Saratoga . After suffering another defeat on October 7 at Bemis Heights (the Second Battle of Saratoga), Burgoyne surrendered his remaining forces on October 17. The American victory Saratoga would prove to be a turning point of the American Revolution, as it prompted France (which had been secretly aiding the rebels since 1776) to enter the war openly on the American side, though it would not formally declare war on Great Britain until June 1778. The American Revolution, which had begun as a civil conflict between Britain and its colonies, had become a world war.

Stalemate in the North, Battle in the South (1778-81)

During the long, hard winter at Valley Forge, Washington’s troops benefited from the training and discipline of the Prussian military officer Baron Friedrich von Steuben (sent by the French) and the leadership of the French aristocrat Marquis de Lafayette . On June 28, 1778, as British forces under Sir Henry Clinton (who had replaced Howe as supreme commander) attempted to withdraw from Philadelphia to New York, Washington’s army attacked them near Monmouth, New Jersey. The battle effectively ended in a draw, as the Americans held their ground, but Clinton was able to get his army and supplies safely to New York. On July 8, a French fleet commanded by the Comte d’Estaing arrived off the Atlantic coast, ready to do battle with the British. A joint attack on the British at Newport, Rhode Island , in late July failed, and for the most part the war settled into a stalemate phase in the North.

The Americans suffered a number of setbacks from 1779 to 1781, including the defection of General Benedict Arnold to the British and the first serious mutinies within the Continental Army. In the South, the British occupied Georgia by early 1779 and captured Charleston, South Carolina in May 1780. British forces under Lord Charles Cornwallis then began an offensive in the region, crushing Gates’ American troops at Camden in mid-August, though the Americans scored a victory over Loyalist forces at King’s Mountain in early October. Nathanael Green replaced Gates as the American commander in the South that December. Under Green’s command, General Daniel Morgan scored a victory against a British force led by Colonel Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens, South Carolina, on January 17, 1781.

Revolutionary War Draws to a Close (1781-83)

By the fall of 1781, Greene’s American forces had managed to force Cornwallis and his men to withdraw to Virginia’s Yorktown peninsula, near where the York River empties into Chesapeake Bay. Supported by a French army commanded by General Jean Baptiste de Rochambeau, Washington moved against Yorktown with a total of around 14,000 soldiers, while a fleet of 36 French warships offshore prevented British reinforcement or evacuation. Trapped and overpowered, Cornwallis was forced to surrender his entire army on October 19. Claiming illness, the British general sent his deputy, Charles O’Hara, to surrender; after O’Hara approached Rochambeau to surrender his sword (the Frenchman deferred to Washington), Washington gave the nod to his own deputy, Benjamin Lincoln, who accepted it.

Though the movement for American independence effectively triumphed at the Battle of Yorktown , contemporary observers did not see that as the decisive victory yet. British forces remained stationed around Charleston, and the powerful main army still resided in New York. Though neither side would take decisive action over the better part of the next two years, the British removal of their troops from Charleston and Savannah in late 1782 finally pointed to the end of the conflict. British and American negotiators in Paris signed preliminary peace terms in Paris late that November, and on September 3, 1783, Great Britain formally recognized the independence of the United States in the Treaty of Paris . At the same time, Britain signed separate peace treaties with France and Spain (which had entered the conflict in 1779), bringing the American Revolution to a close after eight long years.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Essays on the American Revolution

In this Book

- Stephen G. Kurtz

- Published by: The University of North Carolina Press

- Series: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia

Table of Contents

- Title page, Copyright

- pp. vii-viii

- Introduction

- 1. The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation

- BERNARD BAILYN

- 2. An Uneasy Connection: An Analysis of the Preconditions of the American Revolution

- JACK P. GREENE

- 3. Violence and the American Revolution

- RICHARD MAXWELL BROWN

- 4. The American Revolution: The Military Conflict Considered as a Revolutionary War

- pp. 121-156

- 5. The Structure of Politics in the Continental Congress

- H. JAMES HENDERSON

- pp. 157-196

- 6. The Role of Religion in the Revolution: Liberty of Conscience and Cultural Cohesion in the New Nation

- WILLIAM G. McLOUGHLIN

- pp. 197-255

- 7. Feudalism, Communalism, and the Yeoman Freeholder: The American Revolution Considered as a Social Accident

- ROWLAND BERTHOFF AND JOHN M. MURRIN

- pp. 256-288

- 8. Conflict and Consensus in the American Revolution

- EDMUND S. MORGAN

- pp. 289-310

- pp. 311-318

- Notes on the Contributors

- pp. 319-320

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- The Legacy of the Revolution

Why the American Revolution Matters

Posted February 18, 2019 / Basic Principles , History Education , The Legacy of the Revolution

The American Revolution was shaped by high principles and low ones, by imperial politics, dynastic rivalries, ambition, greed, personal loyalties, patriotism, demographic growth, social and economic changes, cultural developments, British intransigence, and American anxieties. It was shaped by conflicting interests between Britain and America, between regions within America, between families and between individuals. It was shaped by religion, ethnicity, and race, as well as by tensions between rich and poor. It was shaped, perhaps above all else, by the aspirations of ordinary people to make fulfilling lives for themselves and their families, to be secure in their possessions, safe in their homes, free to worship as they wished, and to improve their lives by availing themselves of opportunities that seemed to lie within their grasp.

No one of these factors, nor any specific combination of them, can properly be said to have caused the American Revolution. An event as vast as the American Revolution is simply too complex to assign it neatly to particular causes. Although we can never know the causes of the American Revolution with precision, we can see very clearly the most important consequences of the Revolution. They are simply too large and important to miss, and so clearly related to the Revolution that they cannot be traced to any other sequence of events. Every educated American should understand and appreciate them.

First, the American Revolution secured the independence of the United States from the dominion of Great Britain and separated it from the British Empire. While it is altogether possible that the thirteen colonies would have become independent during the nineteenth or twentieth century, as other British colonies did, the resulting nation would certainly have been very different than the one that emerged, independent, from the Revolutionary War. The United States was the first nation in modern times to achieve its independence in a national war of liberation and the first to explain its reasons and its aims in a declaration of independence, a model adopted by national liberation movements in dozens of countries over the last 250 years.

Second, the American Revolution established a republic , with a government dedicated to the interests of ordinary people rather than the interests of kings and aristocrats. The United States was the first large republic since ancient times and the first one to emerge from the revolutions that rocked the Atlantic world, from South America to Eastern Europe, through the middle of the nineteenth century. The American Revolution influenced, to varying degrees, all of the subsequent Atlantic revolutions, most of which led to the establishment of republican governments, though some of those republics did not endure. The American republic has endured, due in part to the resilience of the Federal Constitution, which was the product of more than a decade of debate about the fundamental principles of republican government. Today most of the world’s nations are at least nominal republics due in no small way to the success of the American republic.

Third, the American Revolution created American national identity , a sense of community based on shared history and culture, mutual experience, and belief in a common destiny. The Revolution drew together the thirteen colonies, each with its own history and individual identity, first in resistance to new imperial regulations and taxes, then in rebellion, and finally in a shared struggle for independence. Americans inevitably reduced the complex, chaotic and violent experiences of the Revolution into a narrative of national origins, a story with heroes and villains, of epic struggles and personal sacrifices. This narrative is not properly described as a national myth, because the characters and events in it, unlike the mythic figures and imaginary events celebrated by older cultures, were mostly real. Some of the deeds attributed to those characters were exaggerated and others were fabricated, usually to illustrate some very real quality for which the subject was admired and held up for emulation. The Revolutionaries themselves, mindful of their role as founders of the nation, helped create this common narrative as well as symbols to represent national ideals and aspirations.

American national identity has been expanded and enriched by the shared experiences of two centuries of national life, but those experiences were shaped by the legacy of the Revolution and are mostly incomprehensible without reference to the Revolution. The unprecedented movement of people, money and information in the modern world has created a global marketplace of goods, services, and ideas that has diluted the hold of national identity on many people, but no global identity has yet emerged to replace it, nor does this seem likely to happen any time in the foreseeable future.

Fourth, the American Revolution committed the new nation to ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship and made them the basis of a new political order. None of these ideals was new or originated with Americans. They were all rooted in the philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome, and had been discussed, debated and enlarged by creative political thinkers beginning with the Renaissance. The political writers and philosophers of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment disagreed about many things, but all of them imagined that a just political order would be based on these ideals. What those writers and philosophers imagined, the American Revolution created—a nation in which ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship are the basis of law and the foundation of a free society.

The revolutionary generation did not complete the work of creating a truly free society, which requires overcoming layers of social injustice, exploitation, and other forms of institutionalized oppression that have accumulated over many centuries, as well as eliminating the ignorance, bigotry, and greed that support them. One of the fundamental challenges of a political order based on principles of universal right is that it empowers ignorant, bigoted, callous, selfish, and greedy people in the same way it empowers the wise and virtuous. For this reason, political progress in free societies can be painfully, frustratingly slow, with periods of energetic change interspersed with periods of inaction or even retreat. The wisest of our Revolutionaries understood this, and anticipated that creating a truly free society would take many generations. The flaw lies not in our Revolutionary beginnings or our Revolutionary ideals, but in human nature. Perseverance alone is the answer.

Our independence, our republic, our national identity and our commitment to the high ideals that form the basis of our political order are not simply the consequences of the Revolution, to be embalmed in our history books. They are living legacies of the Revolution, more important now as we face the challenges of the modern world than ever before. Without understanding them, we find our history incomprehensible, our present confused, and our future dark. Understanding them, we recognize our common origins, appreciate our present challenges, and can advocate successfully for the Revolutionary ideals that are the only foundation for the future happiness of the world.

Above: Detail of Liberty by an unidentified American artist, ca. 1800-1820, National Gallery of Art.

If you share our concern about ensuring that all Americans understand and appreciate the constructive achievements of the American Revolution, we invite you to join our movement. Sign up for news and notices from the American Revolution Institute. It costs nothing to express your commitment to thoughtful, responsible, balanced, non-partisan history education.

- Basic Principles

- History Education

- Material Culture

- Revolutionary Characters

- Revolutionary Events

- Revolutionary Ideals

Latest Posts

- The Mysterious Hero’s Return

- The People’s Constitution

- Richard Henry Lee: Gentleman Revolutionary

- El General Washington

- Lessons from the Boston Massacre

Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

By Shannon E. Duffy

The Stamp Act of 1765, the first direct tax ever imposed by the British government on colonial Americans, inadvertently provoked a ten-year clash of wills between Britain and the colonies that led to the American Revolutionary War. During this Revolutionary Crisis period (1765-75), colonists resisted imperial taxes and other Parliamentary innovations with protests and with boycotts of British goods, called nonimportation agreements. Many Philadelphians initially proved more reluctant to join the protests than colonists to the north and south. However, with much of the trade of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and parts of New York flowing through the city’s port, Philadelphia became a central focus for enforcing nonimportation. Ultimately, popular anger over British “encroachments” forced a realignment of power in the town and province and brought Philadelphia-area merchants and consumers into greater support for the resistance movement.

Britain’s Parliament passed the Stamp Act on March 22, 1765, to offset the huge debt amassed during the recent Seven Years’ War (1754-63). The British government intended the Stamp Act to defray the cost of “defending, protecting, and securing” the “British colonies and plantations in America.” The terms of the act required colonials to purchase special paper from designated commissioners for a wide variety of legal and business transactions, varying from court pleadings and wills to newspapers and gaming cards. Contracts written on other than stamped paper were null and void, and counterfeiting the stamps was deemed a capital offense.

The British government seriously underestimated the anger this law would provoke. Colonial “Patriots” argued that cooperation with the law, which imposed taxation without American representation in Parliament, was akin to accepting economic slavery. Major riots occurred in Boston and New York City. Colonial legislatures and newspapers issued strongly worded protests. A German-language press in Germantown encouraged readers to resist the unerträglichen (“unbearable”) Stamp Act. Everywhere, angry mobs targeted royal officials; the Constitutional Courant (Woodbridge, New Jersey) called American-born men who would cooperate with such an act the “vipers of human kind,” and the “worst of parricides.” In October 1765, nine of the thirteen colonies sent representatives to a Stamp Act Congress in New York City to draft a unified protest.

In comparison with other colonial cities, Philadelphia’s initial response to the crisis was mild. While other colonial assemblies took a leading role in organizing the resistance, Pennsylvania’s assembly, dominated by the “Quaker” Party of Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), remained caught up in a struggle to wrest the colony from the Penn family. Franklin, serving in London at the time as colonial agent, so misjudged colonial response that he recommended a trusted colleague, John Hughes (1711-72), for the post of Pennsylvania stamp act distributor.

Philadelphia’s Muted Protests

Franklin’s popularity among the mechanics and artisans muted Philadelphia’s protests, but both he and Hughes were castigated for their apparent support of the unpopular measure. On the night of September 16, 1765, a large mob gathered at the State House to target individuals associated with the act, including Franklin, Hughes, and Galloway. Franklin’s wife, Deborah Read Franklin, (1708-74) reported to her husband that the crowd was dissuaded from attacking the Franklin home by an association of over 800 men formed “for the Preservation of the Peace of the City,” who convinced the protesters to disperse. Once the stamps themselves arrived on October 5, another huge crowd corralled stamp distributor Hughes and made him swear not to execute the act or permit the stamps to be unloaded.

Pennsylvania’s rival Proprietary Party also tried to use the controversy to politically weaken Franklin, blaming him for not trying to halt the legislation. Franklin’s supporters countered that no American could have successfully held off the Stamp Act, given its broad Parliamentary support. One broadside signed by “A Freeman of Pennsylvania” claimed: “Mr. Franklin , or any other American …might as easily have stopped the tide of Delaware , at New Castle , with his Finger, as prevented the Bill passing into a Law.”

Amidst the riots, congresses, petitions, and threats, the most potent form of protest was a new type of resistance action: colonial boycotts of British goods. Called “nonimportation agreements” (when merchants signed them) and “nonconsumption agreements” (when citizens signed them), these agreements were the first large-scale boycotts in history. Made possible by colonial Americans’ growing importance as British consumers, they were promoted through colonial newspapers and broadsides that encouraged readers to show patriotic resistance to the unjust acts.

Philadelphia’s merchants pledged cooperation with nonimportation, albeit somewhat reluctantly. Philadelphia docks tried to unload all ships by November 1, 1765, the date when the Stamp Act would go into effect, accordingly preserving “October 31” on their forms as an unloading date for several weeks—if a ship had begun to be unloaded by Halloween, it was “grandfathered” under the pre-act terms. As late as December, ship-owners still received port authorities’ go-ahead to clear ships, under the fiction that the stamps were somehow inaccessible. Even Philadelphia’s vermin reportedly assisted the resistance effort, as one newspaper gleefully reported: “a Quantity of the Stamp Paper, on board the Sardoine Man of War, has been gnawed to pieces by the Rats!”

The Stamp Act Fails

The 1765 Stamp Act proved an abysmal failure. Mobs ultimately forced all the stamp distributors to resign. Not one of the thirteen colonies collected a shilling from the tax, and the boycott worsened England’s already-depressed economy. The act was repealed within a year. When news of the repeal reached Philadelphia on May 19, 1766, large crowds drank to the health of King George III (1738-1820).

In May 1767, the British Parliament again tried to tax the American colonies, prompting a second round of protests and nonimportation agreements. Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend (1725-67) proposed duties to exploit what he perceived to be an apparent flaw in the Patriots’ argument. While the Patriots denied Parliament’s right to tax, they acknowledged Parliament’s right to regulate colonial trade. Accordingly, the Townshend Acts placed import duties on five categories of imported items: paper, glass, paint, lead, and tea.

While response to the Stamp Act had been immediate and spontaneous, resistance to the Townshend Duties was not. Philadelphia’s merchant community remained divided, both because many of the wealthier merchants wished to try to obtain repeal of the duties quietly, through their contacts with English merchant houses, and also because merchants trading primarily in manufactured British goods (“dry goods” merchants) stood to be much more heavily affected by the terms of the boycott than those houses trading primarily with the West Indies, in “wet goods.”

As segments of the Philadelphia merchants’ community resisted calls for an intercolonial nonimportation agreement, political power in Philadelphia began to shift to the mechanic and artisan community, who were more heavily in favor of the ban. By the summer of 1770, Philadelphia radicals, working with the artisans and mechanics, were a new force in Philadelphia politics. Nonimportation appealed to Philadelphia mechanics from the start, as they also had economic motive to support the boycott, which reduced competition from imported British manufactured goods and hence aided domestic manufactures.

“Letters From a Farmer”

The protest movement also found a powerful advocate in John Dickinson (1732-1808), a Philadelphia lawyer connected to Pennsylvania’s Proprietary Party. Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania , which ran in the Pennsylvania Chronicle from December 1767 to February 1768, attacked the taxes on both constitutional and economic grounds. Dickinson argued that if such taxes were accepted meekly, worse would follow, endangering the very notion of private property.

By May of 1768, Boston and New York had agreed upon an intercolonial nonimportation agreement. Anti-British sentiment grew with the garrisoning of troops in Boston and the dissolving of the Massachusetts legislature. A majority of Philadelphia merchants finally adopted nonimportation on March 10, 1769. However, Patriot enforcement methods (including threats of violence to persons or establishments) alienated many of the Quaker elite, and the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting discouraged Quakers from supporting nonimportation, dividing the city’s leadership.

On April 12, 1770, Parliament repealed all of the Townshend Duties save the one on tea, which was retained to make a point about Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. By the fall of 1770, Philadelphia’s radical leaders were trying frantically to hold nonimportation together. In late September, the Philadelphia merchants ended the boycott for all products other than tea, and by December, the intercolonial boycott was defunct.

Anglo-American relations calmed somewhat in the next few years, until May 1773, when Parliament renewed the taxation controversy by passing the Tea Act. This law lowered the existing tax on tea in an effort to convince Americans to switch from smuggled foreign tea, and also granted agents of the East India Company exclusive rights to sell tea in the colonies. Patriots reacted strongly both to this perceived effort to trick Americans into paying a hidden tax and to the precedent established by granting such a monopoly to a small group of merchants. One broadside called on the “industrious and respectable Body of TRADESMEN and MECHANICS of Pennsylvania” to fight to defend the “dear-earned Fruits of our Labour” from a “Set of luxurious, abandoned and piratical Hirelings” who would ruin not only colonial merchants, but also the mechanics and artisans if such monopolistic grants spread to other items of trade.

Morality of Luxury Items

As tension over the Tea Act grew, colonial protests increasingly stressed moral arguments as well as economic ones, presenting British imported goods as dangerous luxury items that were corrupting American morals and health. One writer in Chester, Pennsylvania, noted the manifest virtue that American merchants were showing in resisting the “Pandora’s box” of danger that the tea ships represented, despite the profits that they could have made from the trade. “A Sermon on Tea,” printed in Lancaster, went so far as to depict tea as an evil in itself, blaming “the tea-table” for encouraging female gossip and malevolent rumors, extravagance, sexual promiscuity, and physical infirmities. A mass town meeting October 16 determined that anyone helping tea ships unload their goods into Philadelphia was “an enemy to his country,” and demanded the resignation of the tea consignees. Once the tea itself showed up in late November aboard the Polly , the ship’s captain was quickly persuaded by threats of fire, tar, and feathering to sail back to London without attempting to unload the cargo.

After the colonies received word of the Coercive Acts , passed by Parliament in response to the “Boston Tea Party” of December 16, 1773, nonimportation and nonconsumption agreements became truly continental. A large meeting of the “freeholders and freemen of the city and county of Philadelphia” declared the Boston Port Bill unconstitutional and resolved to support Bostonians “as suffering in the common cause of America.” Berks County, Pennsylvania, was one of many communities across America to begin collecting relief supplies to aid the people of Boston. The first Continental Congress , meeting in Philadelphia in September 1774 with twelve of the thirteen colonies represented, set up an association to oversee boycott of all British products. A total prohibition on imports began in December, and an export embargo was to start in September 1775 if necessary. The association called for every community to set up elected committees in order to enforce its terms, giving them sweeping authority to inspect commercial records and properties and to publicize violators. Nonimportation and nonconsumption remained major strategies for the American protest movement until the outbreak of war in April 1775 moved the quarrel to a different level.

Shannon E. Duffy received her B.A. from Emory University, her M.A. from the University of New Orleans, and her Ph.D. from the University of Maryland. She is a Senior Lecturer in Early American History at Texas State University. Her manuscript in progress, The Twin Occupations of Revolutionary Philadelphia, explores the psychological effects of the British occupation of Philadelphia under General William Howe, as well as the American reoccupation of the city eight months later under the command of General Benedict Arnold. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

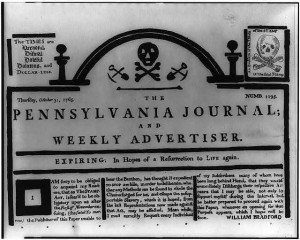

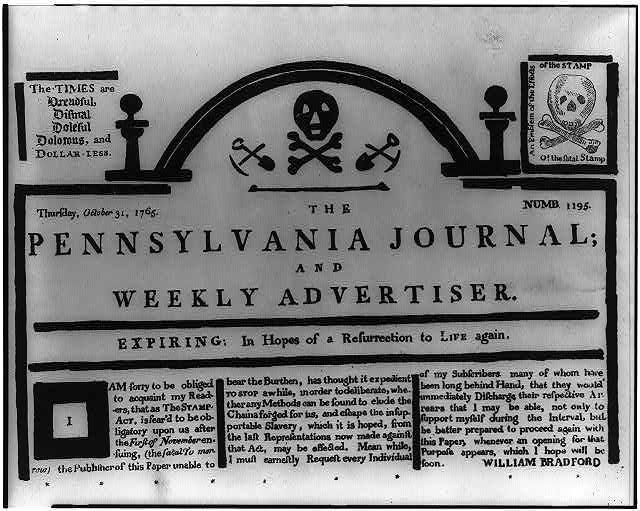

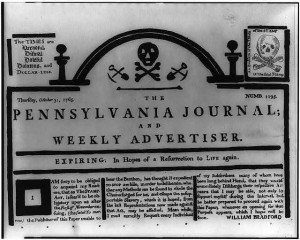

Masthead of the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, October 31, 1765

Library of Congress

This masthead for the October 31, 1765, Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, objecting to the tax about to take effect under the Stamp Act of 1765, depicts a skull-and-crossbones parody of the official stamp required by the act. The publisher, William Bradford, announces that he is suspending publication because he can't afford the tax, calling the skull-and-crossbones icon “An emblem of the effects of the STAMP - O! the fatal Stamp,” and describing the times as “Dreadful, Dismal, Doleful, Dolorous, and Dollar-less.”

Another skull and crossbones turns the masthead into a tombstone with the epitaph, “EXPIRING: In Hopes of a Reserrection to Life again.” Publisher William Bradford reported, “I am sorry to be obliged to acquaint my Readers, that as the STAMP ACT, is fear’d to be obligatory upon us after the First of November ensuing, (the fatal To morrow) the Publisher of this Paper unable to bear the Burthen, has thought it expedient TO STOP awhile.”

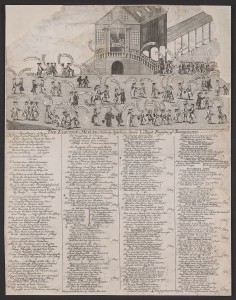

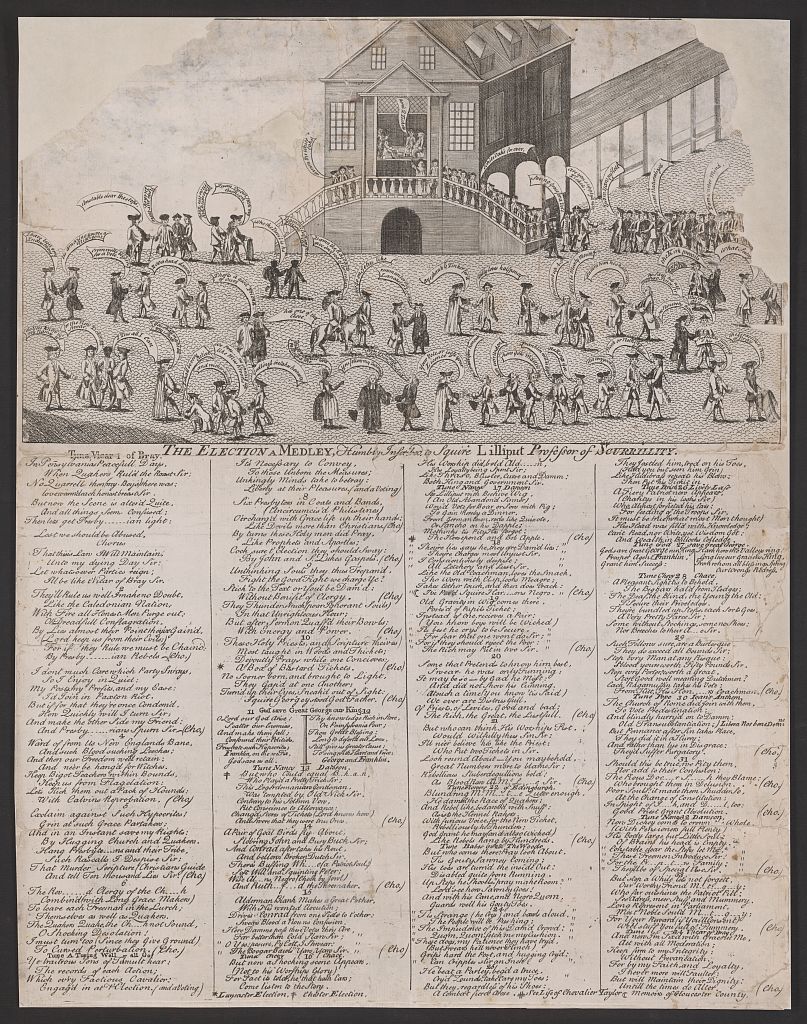

“The ELECTION a MEDLEY, Humbly Inscribed to Squire Lilliput, Professor of SCURRILITY”

This cartoon shows the old courthouse in Philadelphia during the October 1, 1764, election as a line of men wait at the steps on the right to enter the courthouse and cast their votes. In the foreground, many men, several clergymen, and one female slave among them, comment on the candidates and their parties, politics, and religion, as well as on current events and social or political organizations. (Caption adapted from the Library of Congress)

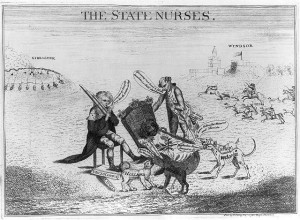

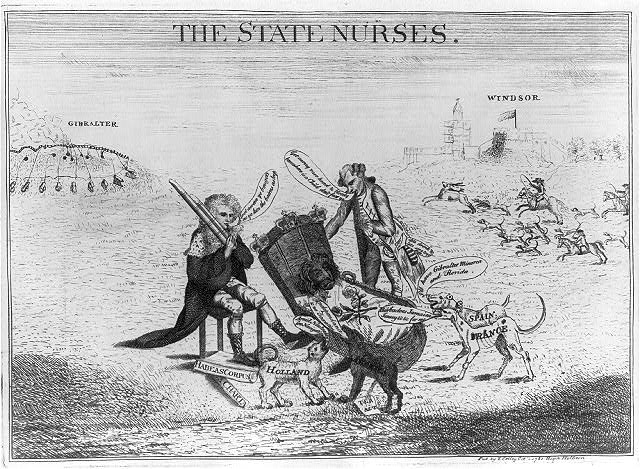

The State Nurses

This 1781 London print shows the Earl of Mansfield, seated, and the Earl of Sandwich keeping watch over the British lion, which is asleep in a cradle surrounded by four barking dogs labeled “Holland,” “America” (urinating on a paper labeled “Tea Act”), “France,” and “Spain.” In the background, on the left, Gibraltar is under siege by the Spanish, and on the right, men (possibly including George III) and dogs are hunting for stag. (Caption adapted from the Library of Congress.)

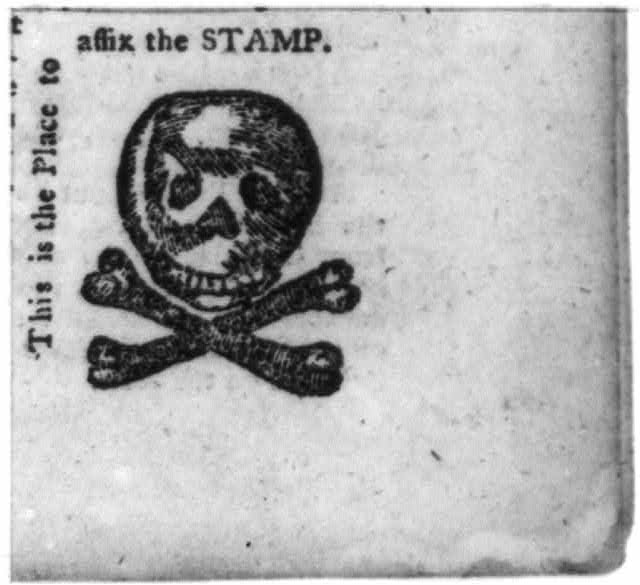

Skull and Crossbones Representation of the Official Stamp Required by the Stamp Act of 1765, Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser , October 24, 1765.

Britain’s Parliament passed the Stamp Act on March 22, 1765, to help offset the huge debt amassed during the recent Seven Years’ War (1754-63). The British government intended the Stamp Act to defray the cost of “defending, protecting, and securing” the “British colonies and plantations in America.”

The terms of the act required colonials to purchase special paper from designated commissioners for a wide variety of legal and business transactions, varying from court pleadings and wills to newspapers and gaming cards. Contracts written on other than stamped paper were null and void, and counterfeiting the stamps was deemed a capital offense.

Colonists angered at the requirements of the Stamp Act used the skull and crossbones to depict the stamp, as seen in this image in the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser that appeared a week before the act was to take effect on November 1, 1765. In fact, resistance to the act in Philadelphia prevented it from being enforced and the act with repealed within a year. When news of the repeal reached Philadelphia on May 19, 1766, large crowds drank to the health of King George III.

Related Topics

- Philadelphia and the World

- Philadelphia and the Nation

- Cradle of Liberty

Time Periods

- American Revolution Era

- Colonial Era

- Center City Philadelphia

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (The)

- Anglican Church (Church of England)

- British Occupation of Philadelphia

- Continental Congresses

- Declaration of Independence

- Philadelphia Campaign

- Common Sense

- Crowds (Colonial and Revolution Eras)

- Ladies Association of Philadelphia

- Trenton and Princeton Campaign (Washington’s Crossing)

- Poconos (The)

- Museum of the American Revolution

Related Reading

Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence . New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Carp, Benjamin L. “Philadelphia Politics, In and Out of Doors, 1742-76,” in Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution , 172-212. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Doerflinger, Thomas M. A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise: Merchants and Economic Development in Revolutionary Philadelphia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

Foner, Eric, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America , rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Merritt, Jane T. “Tea Trade, Consumption, and the Republican Paradox in Prerevolutionary Philadelphia.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 128, no. 2 (Apr. 2004): 117-48.

Morgan, Edmund S. and Helen M. Morgan. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution , rev. ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Nash, Gary. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America . New York: Viking, 2005.

Olton, Charles S. Artisans for Independence: Philadelphia Mechanics and the American Revolution. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1975.

Ousterhout, Anne H. A State Divided: Opposition in Pennsylvania to the American Revolution. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Ryerson, Richard Alan. “The Revolution is now begun”: The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765-1776. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978.

Schultz, Ronald. The Republic of Labor: Philadelphia Artisans and the Politics of Class, 1720-1830 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Related Collections

- Manuscripts and Documents, 1765-1775, Relating to Pennsylvania’s Provincial Non-importation Resolutions American Philosophical Society 105 S. Fifth Street, Philadelphia.

- John Hughes Papers, 1725-1818, and James and Drinker Correspondence related to Philadelphia Tea Act, 1773-1778 Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

Related Places

- Carpenters' Hall, Independence National Historical Park

- Independence Hall and Yard, Independence National Historical Park

- Benjamin Franklin Museum

- American Philosophical Society

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Library Company of Philadelphia

- John Bull and Uncle Sam: Four Centuries of British-American Relations (Library of Congress)

- Benjamin Franklin...In His Own Words: A Cause for Revolution (Library of Congress)

- The Examination of Doctor Franklin, before an August Assembly, relating to the Repeal of the Stamp-Act, &c. (Massachusetts Historical Society)

- The American Revolution, 1765-1783 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Road to Revolution, 1763-1776 Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

National History Day Resources

- Stamp Act announcement and description [Pennsylvania Gazette], March 4, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Benjamin Franklin letter to John Ross, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Resolution of Non-Importation Made by the Citizens of Philadelphia, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania: To the Inhabitants of the British Colonies (Dickinson College)

- Broadside: To the Tradesmen, Mechanics, &c. Of the Province of Pennsylvania, December 4, 1773 (CUNY)

- Joseph Galloway’s Speech to the Continental Congress, September 28, 1774 (Library of Congress)

- Joseph Galloway’s Plan of Union, September 28, 1774 (University of Chicago)

- Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789: Selected Documents (Avalon Project, Yale Law School)

- New Jersey in the American Revolution, 1763-1783: A Documentary History (New Jersey State Library)

- The Sentiments of an American Woman broadside, 1780 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

Home — Essay Samples — History — American Revolution — American Revolution Example

American Revolution Example

- Categories: American Revolution

About this sample

Words: 655 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 655 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Causes of the american revolution, events leading to the american revolution, the declaration of independence, the war and victory, consequences of the american revolution, in conclusion.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1003 words

3 pages / 1790 words

1 pages / 486 words

6 pages / 2546 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American Revolution

The causes of the American Revolution essay delves into the multifaceted reasons behind one of the most pivotal events in American history. The American Revolution, spanning from 1765 to 1783, was a watershed moment that shaped [...]

In conclusion, the Boston Massacre was not an isolated incident, but rather the result of a complex web of political, economic, and social factors. The presence of British troops, the imposition of taxes, the struggle for [...]

Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States has been a seminal work in the field of American history since its publication in 1980. In Chapter 5, titled "A Kind of Revolution," Zinn explores the period leading up to [...]

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet “Common Sense” is a landmark work in the history of American literature and political thought. Published in 1776, it played a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and galvanizing colonists to support [...]

During the American revolution, Great Britain was, and had been, the most powerful empire in the world. As the old saying goes, “the sun never sets on the British empire”, meaning that the British owned land on all sides of the [...]

Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “A woman is like a tea bag - you can’t tell how strong she is until you put her in hot water.” Carol Berkin’s Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence explores this [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Last Witness to the Shot Heard Round the World

T haddeus Blood had just turned twenty when he joined his fellow Minute Men at the Battle of Concord on April 19, 1775. He was, by many accounts, the last survivor of the battle, and, by all accounts, gave the testimony of the fight to Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1833, as Emerson prepared his Concord Hymn, delivered first in 1837. This was the poem in which Emerson famously recounted “the shot heard round the world.” And every year since then, on April 19, men and women from all around the state have traveled to Concord to celebrate this historical moment when a group of “embattled farmers,” to use Emerson’s words, were swept along in the American “Spirit, that made those heroes dare To die, and leave their children free.” And the air is filled with the sound of fife and drum.

It is, however, in the pomp and circumstance, essential to distinguish between wishful mythology and the realities of politics and war. When Emerson interviewed Thaddeus, the old man’s memory of the fight was nearly gone, or at least it had shrunk to more human proportions, admitting, “It could scarcely be called a fight…there was no fife or drum that day.” In fact, Blood’s companions were reluctant freedom fighters, or more likely, just plain old scared. “Capt. Barrett,” Blood informed, “said all sorts of cheering things to his men.” But asked them an earnest, and honest question: “Do you think you can fight em’?” The question was supposed to be rhetorical and energizing, but perhaps it wasn’t. The trees and pastures behind the Minute Men led to the safety of Blood Farm. As Emerson noted, these Minute Men were not lionized yet, and they, “the kings subjects”…”did not want to fight.” This was not necessarily a function of cowardice—at least I don’t think so—but rather a sign of wisdom, an acknowledgement that war is no simple thing, and that once shots are fired, they are very hard to recover. Revolutions are always and only celebrated in hindsight, by the survivors and their descendants.

My family lives in the white clapboard saltbox at 335 River Road in Carlisle, Massachusetts, the one-time home of Thaddeus Blood, who was born—most likely in our family room—on May 28, 1755. He was an American Blood, a member of one of our nation’s first, most expansive, and most audacious pioneer families, part of a lineage that included Thomas Blood, the only man to ever steal the British Crown Jewels, and Robert Blood, who was among the first in the colonies to violently oppose taxation at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Bloods arrived on the shores of New England with the first settlers, and put down roots on Blood Farm, the 3,000-acre plot of land where Thaddeus was born.

What was the truth of the Concord Fight, who actually fired “the shot heard round the world?” It was probably triggered by accident, by the British. “When they had fired,” Blood told Emerson, “there were several (American) men riding on horseback. There was Uncle Blood with hi cap and he waved his cap and cried “fire damn em, and every man shouted along the line.” A misfire and a great deal of fearful shouting in the name of self-defense—this is what precipitated the fight that would become our war. Emerson encouraged the aged Thaddeus to tell him more, to explain in full what it had been like to be there on that historic day. Thaddeus told Emerson to leave him in repose, that “the truth will never be known.”

I think there is something important about Blood’s honesty regarding the truth of war. So did Emerson, writing, “in all the anecdotes of that day’s events we may discern the natural actions of the people. It was not an extravagant ebullition of feeling, but might have been calculated on by any one acquainted with the spirits and habits of our community.” Emerson was cutting the celebration down to rightful size. He wasn’t being cynical but rather realistic, human, and hopeful. He explained that “these poor farmers who came up, that day, to defend their native soil, acted from the simplest instincts. They did not babble about glory…”. They were justifiably frightened in the face of an uncertain future that was soon to become their own.

Some years ago, while teaching military ethics at UMass Lowell (thirteen miles from Concord), one of my students turned to another, a former Marine, and asked the question that all of us had been thinking for most of the semester: “What is it really like to be in battle?” The young man shrugged: “I don’t know. You have to be there. It is very real. And very confusing.” There is very little that is confusing about celebrations and memorials. History is usually presented in such a clean and uniform way—without confusion or contradiction. Which is to say that it is rarely true. Emerson bid Thaddeus Blood goodbye after an interview in July 1835 with a distinct impression that would color his philosophy on the whole: that courage and independence are shocking rare; that they often emerge in tandem with accident and ambivalence; that they often teeter on the brink of their opposite, namely apparent cowardice.

Thaddeus’ family spent the next two-hundred years fanning out across the United States, contributing to its sense of self and to the mythology that we often celebrate today. Among these American Bloods was a friend to Henry David Thoreau and to the American pragmatist William James, and a lover and husband to Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to ever run for the Presidency. They participated in every major military conflict to the present, drove the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, and spearheaded Western expansion in the new United States. But Thaddeus’ family, like any long-standing American family, give us portrait of a nation without the fife and drum—instead realistic, confusing, confused, heedless, halting, and quietly wild. The celebrations will go on, but it seems healthy, if not essential, to think about what might lie beneath our histories, and what might have been pointedly forgotten for the sake of commemoration.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Ashland High School senior is local Daughters of the American Revolution essay winner

SHERBORN — An Ashland High School senior has been selected as this year's Framingham chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution local essay winner.

Emily Umholtz was selected from among seven area Good Citizen winners and selected by judges not affiliated with the DAR. She is a Student Council representative, a 2024 class officer and has been a captain for two years for ultimate frisbee.

Her future plans include attending college to major in chemistry, with a sub-focus in law and justice.

Umholtz was honored in February during the DAR's Good Citizen Award Ceremony at The Sherborn 1858 Town House.

Each year, the Framingham chapter of the DAR invites seven schools to participate in its Good Citizen Program.

Other students selected as Good Citizen winners by their schools included Alivia Toure, of Bellingham High School; Lunah Semprum, of Framingham High School; Reese Holmes, of Holliston High School; William Adamski, of Hopedale Junior-Senior High School; Caroline Kane, of Hopkinton High School); and Robert Lyons Jr., of Milford High School.

Each school’s faculty and student body committee choose one student from their senior class to become their school’s Good Citizen; students are recognized and awarded by the Framingham chapter of the DAR. Each Good Citizen must have and maintain the qualities of dependability, service, leadership and patriotism.

During the ceremony, Master Sgt. Andrew Baumgartner, of West Point Military Academy, served as guest speaker. He spoke of his love of education and his experiences during his years of service.

Also speaking was Vice President General of DAR Paula Renkas.

What campus protests at ASU and elsewhere are really about. It's poisonous.

Opinion: revolutionary thinking is turning american universities into fever swamps of antisemitism and worse..

At the height of the pandemic and the race protests of summer 2020, one of the more perceptive thinkers in American journalism, Peter Savodnik, wrote a haunting essay for Tablet magazine.

Amid all the upheaval in the country, his mind had wandered back to 2012 and the quietude of rural Vermont, when he taught a retreat course at Middlebury College on the intersection of Russian literature and politics.

That summer he guided 18 students, “mostly freshmen and sophomores,” on an excursion of 1860s Russia by way of three novels of that time — Ivan Turgenev’s "Fathers and Sons," Fyodor Dostoevsky’s "Crime and Punishment" and Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s "What Is to Be Done?"

“I focused on the 1860s because that was when everything seemed to pivot just so,” he wrote, “and the arc of history started to bend in a more precarious direction, toward a precipice that few could have foreseen more than a half-century before the revolution.”

An ominous message posted by ASU students

Since reading Savodnik’s long and prescient essay in a magazine devoted to Jewish perspectives on news and culture, I have since recommended it to friends and family so they too may be haunted.

I’ve not stopped thinking about it for years and have returned to it often.

It was on my mind again several weeks ago when one of the student political organizations at Arizona State University found itself in big trouble with the administration.

MECHA de ASU had joined the maelstrom of anti-Israel, pro-Palestinian protests across the nation and, according to ASU’s student newspaper, The State Press, had posted an ominous message on Instagram:

“Death to boer. Death to the Pilgrim. Death to the zionist. Death to the settler."

Anyone who follows international news would instantly recognize “Death to boer (sic)” as similar to the expression of South African populist Julius Malema, who has called on his followers to “Kill the Boer!”, frequently with his hand held in the shape of a pistol.

American businessman Elon Musk, who grew up in South Africa, said Malema is calling for the murder of South Africa’s white farmers – “for the genocide of white people in South Africa.”

But Malema and others in South Africa have argued “Kill the Boer!” is merely an old protest slogan and song lyric of apartheid South Africa and does not literally mean to kill white people.

That didn’t stop The Economist in February from asking, “Is Julius Malema the most dangerous man in South Africa?”

In Mecha de ASU’s Instagram, it also calls for death to “pilgrim,” “zionist” (sic) and “settler,” which should be interpreted as that group’s embrace of “decolonization” or the “global intifada” — the effort to unwind white control of land, property and government across parts of mostly the global north, including North America.

Mecha de ASU is playing with fire

We should interpret it that way, because that’s how Mecha de ASU describes its goals in its mission statement:

“Mechistas must take it upon themselves to organize and politicize our communities to build power to enact liberatory politics. This means not only combating the legacies of colonization such as capitalism and white supremacy, but creating a movement that centers Black, Indigenous, Queer, Trans, and Femme people.”

If you’ve wondered how any LGBTQ people could support the Palestinians, who would brutally abuse them for their sexuality, here’s why.

The campus movement is about bigger things than the children of the Gaza Strip. It’s about power.

As the Mecha de ASU mission statement explains...

“...we must devote ourselves to ending settler colonialism, anti-Black racism, heteronormativity, borders and prisons because our liberation does not exist until these legacies of colonization are abolished. ... MECHA values are rooted in anti-colonialism, anti-capitalism, anti-heteropatriarchy, anti-imperialism, and antiracism.”

After the Instagram post, the university administration placed Mecha de ASU on interim suspension for violating the university code of conduct, the State Press reported.

In an October 2023 statement, ASU officials had written that the school fosters "a safe and inclusive environment," and "respectful conversations that promote mutual understanding and empathy," the State Press reported.