Attention! Your ePaper is waiting for publication!

By publishing your document, the content will be optimally indexed by Google via AI and sorted into the right category for over 500 million ePaper readers on YUMPU.

This will ensure high visibility and many readers!

Your ePaper is now published and live on YUMPU!

You can find your publication here:

Share your interactive ePaper on all platforms and on your website with our embed function

Critical Thinking Disposition Self- Rating Form. - Pearson Learning ...

- disposition

- pearsoncustom.com

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Think <strong>Critical</strong>ly, by Peter Facione and Carol Ann Gittens. Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2013 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.<br />

000200010271662400

Read the Chapter on mythinkinglab.com<br />

Listen to the Chapter Audio on mythinkinglab.com<br />

After training<br />

for every conceivable contingency, the unexpected<br />

happened. Initially, the challenge was simply to figure<br />

out what the problem was. If it could be correctly<br />

identified, then there might be some slim chance of<br />

survival. If not, the outcome could be tragic.<br />

Watch the Video on mythinkinglab.com<br />

As you watch the<br />

video clip at www.mythinkinglab.com, keep in mind<br />

that you are seeing a dramatic reenactment. The actors,<br />

music, camera angles, staging, props, and lighting<br />

all contribute to our overall experience. That said,<br />

this portrayal of individual and group problem solving<br />

is highly consistent with the research on human<br />

cognition and decision making. i The clip dramatizes<br />

a group of people engaged in thinking critically together<br />

about one thing: What could the problem be<br />

Their approach is to apply their reasoning skills to the<br />

best of their ability. But, more than only their thinking<br />

skills, their mental habits of being analytical, focused,<br />

and systematic enabled them to apply those skills<br />

well during the moment of crisis. We suggest that you<br />

watch the brief video prior to reading the summary<br />

analysis of Apollo 13.<br />

CHAPTER<br />

Skilled and<br />

Eager to<br />

Think<br />

QHOW can I cultivate positive<br />

critical thinking habits of mind<br />

WHAT questions can I ask to<br />

engage my critical thinking<br />

skills<br />

WHAT are induction and<br />

deduction, and how do they<br />

differ<br />

HOW can I best use this book<br />

to develop my critical thinking<br />

02<br />

19<br />

000200010271662400<br />

Chapter 02 20<br />

Positive <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

Habits of Mind<br />

The Apollo 13 sequence opens with the staff at Mission Control<br />

in Houston and the three-person crew of Apollo 13 well<br />

into the boredom of routine housekeeping. Suddenly, the crew<br />

of Apollo 13 hears a loud banging noise and their small, fragile<br />

craft starts gyrating wildly. The startled look on Tom Hanks’s<br />

face in the video reenactment is priceless. A full fifteen seconds<br />

elapses before he speaks. During that time his critical<br />

thinking is in overdrive. He is trying to interpret what has just<br />

happened. His mind has to make sense of the entirely unexpected<br />

and unfamiliar experience. He neither dismisses nor<br />

ignores the new information that presents itself. His attention<br />

moves between checking the craft’s instrument panel and<br />

attending to the sounds and motions of the spacecraft itself.<br />

He focuses his mind, forms a cautious but accurate interpretation,<br />

and with the disciplined self-control we expect of a welltrained<br />

professional, he informs Mission Control in Houston,<br />

Texas that they most definitely have a problem! ii<br />

At first, the astronauts in the spacecraft and the technicians<br />

at Mission Control call out information from their desk monitors<br />

and the spacecraft’s instrument displays. They crave information<br />

from all sources. They know they must share what<br />

they are learning with each other as quickly as they can in the<br />

hope that someone will be able to make sense out of things.<br />

They do not yet know which piece of information may be the<br />

clue to their life-or-death problem, but they have the discipline<br />

of mind to want to know everything that might be relevant.<br />

And they have the confidence in their collective critical thinking<br />

skills to believe that this approach offers their best hope to<br />

identify the true problem.<br />

One member of the ground crew calls out, that O 2<br />

Tank<br />

Two is not showing any readings. That vital bit of information<br />

swooshes by almost unnoticed in the torrents of data. Soon<br />

a number of people begin proposing explanations: Perhaps<br />

the spacecraft had been struck by a meteor. Perhaps its radio<br />

antenna is broken. Perhaps the issue is instrumentation, rather<br />

than something more serious, like a loss of power.<br />

The vital critical thinking skill of <strong>Self</strong>-Regulation is personified<br />

in the movie by the character played by Ed Harris. His job<br />

is to monitor everything that is going on and to correct the process<br />

if he judges that it is getting off track. Harris’s character<br />

makes the claim that the problem cannot simply be instrumentation.<br />

The reason for that claim is clear and reasonable.<br />

The astronauts are reporting hearing loud bangs and feeling<br />

their spacecraft jolt and shimmy. The unspoken assumption,<br />

one every pilot and technician understands in this context<br />

is that these physical manifestations—the noises and the<br />

shaking—would not be occurring if the problem were instrumentation.<br />

The conclusion Harris’s character expressed has<br />

the effect of directing everyone’s energy and attention toward<br />

one set of possibilities, those that would be considered real<br />

problems rather than toward the other set of possibilities. Had<br />

he categorized the problem as instrumentation, then everyone’s<br />

efforts would have been directed toward checking and<br />

verifying that the gauges and computers were functioning<br />

properly.<br />

There is a very important lesson for good critical thinking in<br />

what we see Ed Harris doing. Judging correctly what kind of<br />

problem we are facing is essential. If we are mistaken about<br />

what the problem is, we are likely to consume time, energy,<br />

and resources exploring the wrong kinds of solutions. By the<br />

time we figure out that we took the wrong road, the situation<br />

could have become much worse than when we started.<br />

The Apollo 13 situation is a perfect example. In real life, had<br />

the people at Mission Control in Houston classified the problem<br />

as instrumentation, they would have used up what little<br />

oxygen there was left aboard the spacecraft while the ground<br />

crew spent time validating their instrument readouts.<br />

Back on the spacecraft, Tom Hanks, who personifies the<br />

critical thinking skills of interpretation and inference, is struggling<br />

to regain navigational control. He articulates the inference<br />

by saying that had they been hit by a meteor, they would all be<br />

dead already. A few moments later he glances out the spacecraft’s<br />

side window. Something in the rearview mirror catches<br />

his attention. Again, his inquisitive mind will not ignore what<br />

he’s seeing. A few seconds pass as he tries to interpret what it<br />

might be. He offers his first observation that the craft is venting<br />

something into space. The mental focus and stress of the entire<br />

Houston ground crew are etched on their faces. Their expressions<br />

reveal the question in their minds: What could he possibly<br />

be seeing Seconds pass with agonizing slowness. Using<br />

his interpretive skills, Tom Hanks categorizes with caution and<br />

then, adding greater precision, he infers that the venting must<br />

be some kind of a gas. He pauses to try to figure out what the<br />

gas might be and realizes that it must surely be the oxygen.<br />

Kevin Bacon looks immediately to the oxygen tank gauge on<br />

the instrument panel for information that might confirm or disconfirm<br />

whether it really is the oxygen. It is.<br />

“If we were compelled to make<br />

a choice between these personal<br />

attributes [of a thoughtful reasoner]<br />

and knowledge about the principles<br />

of logical reasoning together with<br />

some degree of technical skill<br />

in manipulating special logical<br />

processes, we should decide for<br />

the former.”<br />

John Dewey, How We Think iii<br />

Think <strong>Critical</strong>ly, by Peter Facione and Carol Ann Gittens. Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2013 by <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc.

• ••<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Disposition</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-<strong>Rating</strong> <strong>Form</strong><br />

Answer yes or no to each. Can I name any<br />

specific instances over the past two days<br />

when I:<br />

1 was courageous enough to<br />

ask tough questions about some of<br />

my longest held and most cherished<br />

beliefs<br />

2 backed away from questions<br />

that might undercut some of my<br />

longest held and most cherished<br />

3 showed tolerance toward the<br />

beliefs, ideas, or opinions of someone<br />

with whom I disagreed<br />

4 tried to find information to<br />

build up my side of an argument but<br />

not the other side<br />

5 tried to think ahead and anticipate<br />

the consequences of various<br />

options<br />

6 laughed at what other people<br />

said and made fun of their beliefs,<br />

values, opinion, or points of views<br />

7 made a serious effort to be<br />

analytical about the foreseeable outcomes<br />

of my decisions<br />

8 manipulated information to<br />

suit my own purposes<br />

9 encouraged peers not to dismiss<br />

out of hand the opinions and<br />

ideas other people offered<br />

10 acted with disregard for the<br />

possible averse consequences of my<br />

choices<br />

11 organized for myself a<br />

thoughtfully systematic approach to<br />

a question or issue<br />

12 jumped in and tried to solve a<br />

problem without first thinking about<br />

how to approach it<br />

13 approached a challenging<br />

problem with confidence that I could<br />

think it through<br />

14 instead of working through a<br />

question for myself, took the easy<br />

way out and asked someone else for<br />

the answer<br />

15 read a report, newspaper, or<br />

book chapter or watched the world<br />

news or a documentary just to learn<br />

something new<br />

16 put zero effort into learning<br />

something new until I saw the immediate<br />

utility in doing so<br />

17 showed how strong I was by<br />

being willing to honestly reconsider<br />

a decision<br />

18 showed how strong I was by<br />

refusing to change my mind<br />

19 attended to variations in circumstances,<br />

contexts, and situations<br />

in coming to a decision<br />

20 refused to reconsider my<br />

position on an issue in light of differences<br />

in context, situations, or<br />

circumstances<br />

If you have described yourself honestly, this<br />

self-rating form can offer a rough estimate<br />

of what you think your overall disposition<br />

toward critical thinking has been in the past<br />

two days.<br />

Give yourself 5 points for every “Yes” on<br />

odd numbered items and for every “No” on<br />

even numbered items. If your total is 70 or<br />

above, you are rating your disposition toward<br />

critical thinking over the past two days<br />

as generally positive. Scores of 50 or lower<br />

indicate a self-rating that is averse or hostile<br />

toward critical thinking over the past two<br />

days. Scores between 50 and 70 show that<br />

you would rate yourself as displaying an ambivalent<br />

or mixed overall disposition toward<br />

critical thinking over the past two days.<br />

Interpret results on this tool cautiously. At<br />

best this tool offers only a rough approximation<br />

with regard to a brief moment in<br />

time. Other tools are more refined, such as<br />

the California <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Disposition</strong><br />

Inventory, which gives results for each of<br />

the seven critical thinking habits of mind.<br />

© 2009 Measured Reasons LLC, Hermosa<br />

Beach, CA. Used with permission.<br />

21<br />

Skilled and Eager to Think<br />

Being by habit inclined to anticipate consequences, everyone<br />

silently contemplates the potential tragedy implied by the<br />

loss of oxygen. As truth-seekers, they must accept the finding.<br />

They cannot fathom denying it or hiding from it. Their somber<br />

response comes in the form of Mission Control’s grim but objective<br />

acknowledgment that the spacecraft is venting.<br />

OK, now we have the truth. What are we going to do about<br />

it The characters depicted in this movie are driven by a powerful<br />

orientation toward using critical thinking to resolve whatever<br />

problems they encounter. The room erupts with noise<br />

as each person refocuses on their little piece of the problem.<br />

People are moving quickly, talking fast, pulling headset wires<br />

out of sockets in their haste. The chaos and cacophony in the<br />

room reveal that the group is not yet taking a systematic, organized<br />

approach. Monitoring this, Ed Harris’s character interjects<br />

another self-correction into the group’s critical thinking.<br />

He may not yet know how this problem of the oxygen supply<br />

is going to be solved or even whether this problem can<br />

be solved, but he is going to be sure that the ground crew addresses<br />

it with all the skill and all the mental power it can muster.<br />

He directs everyone to locate whomever they may need to<br />

assist them in their work and to focus themselves and those<br />

others immediately on working the problem.<br />

As depicted in this excerpt, the combined ground crew<br />

and spacecraft crew, as a group, would earn a top score on<br />

“Holistic <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Scoring Rubric.” The emotions and<br />

stresses of the situation are unmistakable. The group’s powerfully<br />

strong critical thinking habits of mind enable the group to<br />

use that energy productively. It gives urgency to the efforts.<br />

Thus, the message about our thinking processes that emerges<br />

is that emotion need not be the antithesis to reason; emotion<br />

can be the impetus to reason.<br />

Chapter 02 22<br />

THE SPIRIT OF A STRONG<br />

CRITICAL THINKER<br />

The scene shown in the video clip was well staged. Skillful<br />

actors displayed the behaviors and responses of strong critical<br />

thinkers engaged in problem solving at a moment of crisis.<br />

Authors of screenplays and novels often endow their protagonists<br />

with strongly positive critical thinking skills and dispositions.<br />

The brilliantly insightful Sherlock Holmes, played in films<br />

by Robert Downey Jr., the analytical and streetwise NYPD<br />

Detective Jane Timoney from the NBC series Prime Suspect,<br />

played by Maria Bello, or the clever and quick witted Patrick<br />

Jane in the CBS series The Mentalist, played by Simon Baker,<br />

come to mind as examples. A key difference, however, is that<br />

fictional detectives always solve the mystery, while, as we all<br />

know, in the real world there is no guarantee. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking<br />

is about how we approach problems, decisions, questions,<br />

and issues even if ultimate success eludes us. Being<br />

disposed to engage our skills as best we can is the “eager”<br />

part of “skilled and eager” to think. First we will examine the<br />

“eager” part, beginning with taking a closer look at the overall<br />

disposition toward critical thinking. Later in this chapter we will<br />

examine the “skilled” part, the core critical thinking skills.<br />

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE HABITS<br />

OF MIND<br />

A person with a strong disposition toward critical thinking has<br />

the consistent internal motivation to engage problems and<br />

make decisions by using critical thinking. iv Operationally this<br />

means three things: The person consistently values critical<br />

thinking, believes that using critical thinking skills offers the<br />

greatest promise for reaching good judgments, and intends to<br />

approach problems and decisions by applying critical thinking<br />

skills as best as he or she can. This combination of values, beliefs,<br />

and intentions forms the habits of mind that dispose the<br />

person toward critical thinking. v<br />

Someone strongly disposed toward critical thinking would<br />

probably agree with the following statements:<br />

• “I hate talk shows where people shout their opinions but<br />

never give any reasons at all.”<br />

• “Figuring out what people really mean by what they say is<br />

important to me.”<br />

• “I always do better in jobs where I’m expected to think<br />

things out for myself.”<br />

• “I hold off making decisions until I have thought through<br />

my options.”<br />

• “Rather than relying on someone else’s notes, I prefer to<br />

read the material myself.”<br />

• “I try to see the merit in another’s opinion, even if I reject it later.”<br />

• “Even if a problem is tougher than I expected, I will keep<br />

working on it.”<br />

• “Making intelligent decisions is more important than<br />

winning arguments.”<br />

Persons who display a strong positive disposition toward<br />

critical thinking are described in the literature as “having<br />

a critical spirit,” or as people who are “mindful,” “reflective,”<br />

and “meta-cognitive.” These expressions give a person credit<br />

for consistently applying their critical thinking skills to whatever<br />

problem, question, or issue is at hand. People with a<br />

critical spirit tend to ask good questions, probe deeply for<br />

the truth, inquire fully into matters, and strive to anticipate the<br />

consequences of various options. In real life our skills may or<br />

may not be strong enough, our knowledge may or may not be<br />

adequate to the task at hand. The problem may or may not be<br />

too difficult for us. Forces beyond our control might or might<br />

not determine the actual outcome. None of that cancels out<br />

the positive critical thinking habits of mind with which strong<br />

critical thinkers strive to approach the problems life sends<br />

their way.<br />

A person with weak critical thinking dispositions might<br />

disagree with the previous statements and be more likely to<br />

agree with these:<br />

• “I prefer jobs where the supervisor says exactly what to do<br />

and exactly how to do it.”<br />

• “No matter how complex the problem, you can bet there<br />

will be a simple solution.”<br />

• “I don’t waste time looking things up.”<br />

• “I hate when teachers discuss problems instead of just<br />

giving the answers.”<br />

• “If my belief is truly sincere, evidence to the contrary is<br />

irrelevant.”<br />

• “Selling an idea is like selling cars; you say whatever<br />

works.”<br />

• “Why go to the library when you can use made-up quotes<br />

and phony references”<br />

• “I take a lot on faith because questioning the fundamentals<br />

frightens me.”<br />

• “There is no point in trying to understand what terrorists<br />

are thinking.”<br />

When it comes to approaching specific questions, issues,<br />

decisions or problems, people with a weak or negative critical<br />

thinking disposition are apt to be impulsive, reactive, muddleheaded,<br />

disorganized, overly simplistic, spotty about getting<br />

relevant information, likely to apply unreasonable criteria, easily<br />

distracted, ready to give up at the least hint of difficulty, intent<br />

on a solution that is more detailed than is possible, or too<br />

readily satisfied with some uselessly vague response.<br />

PRELIMINARY SELF-ASSESSMENT<br />

It is only natural to wonder about our own disposition. The<br />

“<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Disposition</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-<strong>Rating</strong> <strong>Form</strong>,” found on<br />

page 21, offers us a way of reflecting on our own values, beliefs,<br />

and intentions about the use of critical thinking. As noted<br />

on the form itself, “This tool offers only a rough approximation<br />

with regard to a brief moment in time.” We invite you to take<br />

a moment and complete the self-assessment. Keep in mind<br />

as you interpret the results that this measure does not assess<br />

critical thinking skills. Rather, this tool permits one to reflect on<br />

whether, over the past two days, the disposition manifested<br />

in behavior was positive, ambivalent, or averse toward engaging<br />

in thoughtful, reflective, and fair-minded judgments about<br />

what to believe or what to do.<br />

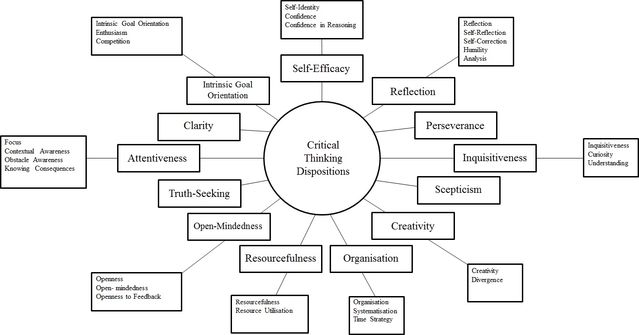

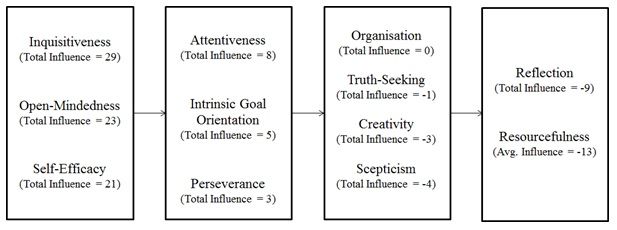

RESEARCH ON CRITICAL THINKING<br />

HABITS OF MIND<br />

The broad understanding of being disposed toward using critical<br />

thinking, or disposed away from using critical thinking, has been<br />

the object of empirical research in the cognitive sciences since<br />

the early 1990s. The purpose of this research has been to give<br />

greater precision to the analysis and measurement of the dispositional<br />

dimension of critical thinking.<br />

Seven Positive <strong>Critical</strong><br />

<strong>Thinking</strong> Habits of Mind<br />

One research approach involved asking thousands of people<br />

to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed<br />

with a long list of statements not unlike those in the two<br />

short lists presented above. Using statistical analysis, these<br />

researchers identified seven measurable aspects within the<br />

overall disposition toward critical thinking. We can think of<br />

these as the seven positive critical thinking habits of mind. vi<br />

Based on this research, we can describe someone who has<br />

all seven positive critical thinking habits of mind as a person<br />

who is:<br />

• Truth-seeking – meaning that the person has intellectual integrity<br />

and a courageous desire to actively strive for the best<br />

possible knowledge in any given situation. A truth-seeker<br />

asks probing questions and follows reasons and evidence<br />

wherever they lead, even if the results go against his or her<br />

cherished beliefs.<br />

• Open-minded – meaning that the person is tolerant of divergent<br />

views and sensitive to the possibility of his or her<br />

own possible biases. An open-minded person respects the<br />

right of others to have different opinions.<br />

• Analytical – meaning that the person is habitually alert<br />

to potential problems and vigilant in anticipating consequences<br />

and trying to foresee short-term and long-term<br />

outcomes of events, decisions, and actions. Another word<br />

to describe this habit of mind might be “Foresightful.”<br />

• Systematic – meaning that the person consistently endeavors<br />

to take an organized and thorough approach to<br />

identifying and resolving problems. The systematic person<br />

is orderly, focused, persistent, and diligent in his or her<br />

approach to problem solving, learning, and inquiry.<br />

• Confident in reasoning – meaning that the person is trustful<br />

of his or her own reasoning skills to yield good judgments. A<br />

person’s or a group’s confidence in their own critical thinking<br />

may or may not be warranted, which is another matter.<br />

• Inquisitive – meaning that the person habitually strives to be<br />

well-informed, wants to know how things work, and seeks<br />

to learn new things about a wide range of topics, even if<br />

the immediate utility of knowing those things is not directly<br />

evident. The inquisitive person has a strong sense of intellectual<br />

curiosity.<br />

• Judicious – meaning that the person approaches problems<br />

with a sense that some are ill-structured and some can have<br />

more than one plausible solution. The judicious person has<br />

the cognitive maturity to realize that many questions and<br />

issues are not black and white and that, at times, judgments<br />

must be made in contexts of uncertainty.<br />

Negative Habits of Mind<br />

After the measurement tools were refined and validated for<br />

use in data gathering, the results of repeated samplings<br />

showed that some people are strongly positive on one or<br />

more of the seven positive dispositional aspects. Some people<br />

are ambivalent or negatively disposed on one or more of<br />

the seven.<br />

There is a name associated with the negative end of the<br />

scale for each of the seven attributes, just as there is a name<br />

associated with the positive end of the scale. The “<strong>Critical</strong><br />

<strong>Thinking</strong> Habits of Mind” chart on page 26 lists the names,<br />

for both positive and negative attributes. A person’s individual<br />

dispositional portrait emerges from the seven, for a person<br />

may be positive, ambivalent, or negative on each.<br />

In the film Philadelphia, Denzel Washington plays a personal<br />

liability litigator who is not above increasing the amount<br />

a client seeks for “pain and suffering” by hinting to the client<br />

that he may have more medical problems than the client<br />

had at first noticed. Watch the scene where a new potential<br />

client, played by Tom Hanks, visits Washington’s office seeking<br />

representation. Access this clip at www.mythinkinglab<br />

.com. Watch the Video on mythinkinglab.com<br />

The clip from Philadelphia starts out with Denzel Washington<br />

talking to a client who wants to sue the city over a<br />

foolish accident that the man brought upon himself. The<br />

scene establishes that Washington is a hungry lawyer who<br />

will take almost any case. Tom Hanks comes into the office<br />

and says that he wants to sue his former employer, believing<br />

that he was wrongly fired from his job because he has<br />

AIDS. You would think that Washington would jump at this<br />

opportunity. There is a lot of money to be made if he can win<br />

the case. Truth-seeking demands that the real reason for the<br />

firing be brought to light. But at this point in the story, Washington<br />

declines to take the case.<br />

Notice what the filmmakers do with the camera angles to<br />

show what Washington is thinking as he considers what to do.<br />

His eyes focus on the picture of his wife and child, on the skin<br />

lesion on Hanks’s head, and on the cigars and other things<br />

Hanks touches. The story takes place during the early years<br />

when the general public did not understand AIDS well at all. It<br />

was a time when prejudices, homophobia, and misinformation<br />

23<br />

Chapter 02 24<br />

nonverbal thinking cues are so well done<br />

The <strong>Disposition</strong> toward <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

by the filmmakers that we are not surprised<br />

when Washington, having thought<br />

things through, refuses to take the case.<br />

There is no question that critical thinking<br />

is wonderfully powerful. Yet, by itself<br />

it is incomplete. We need knowledge,<br />

values, and sensitivities to guide our<br />

thinking. Washington’s character is<br />

sensitive to what he thinks are the<br />

dangers of the disease and what he<br />

believes (wrongly) about the ways<br />

it might be transmitted. His character<br />

uses his critical thinking skills,<br />

which turn out to be quite formidable<br />

as the film progresses. But his beliefs<br />

about AIDS are simply wrong. He<br />

makes a judgment at the time not to represent<br />

Hanks’s character. It is not the same<br />

judgment he will make later in the film, after<br />

he becomes better informed. Fortunately, he has<br />

the open-mindedness to entertain the possibility of representing<br />

Hanks’s character, that perhaps Hanks’s character<br />

does have a winnable case, and that perhaps the risks associated<br />

with AIDS are not as great as he had at first imagined. He<br />

has the inquisitiveness and the truth-seeking skills to gather<br />

more accurate information. And he has the judiciousness to<br />

reconsider and to change his mind.<br />

surrounded the disease. Washington’s character portrays<br />

the uncertainty and misplaced fears of the U.S. public at that<br />

time. Not understanding AIDS or being misinformed, Washington’s<br />

character is frightened for himself and for his family.<br />

Notice how he stands in the very far corner of his office, as<br />

physically far away from Hanks’s character as possible. He<br />

wipes his hand against his trousers after shaking hands. The<br />

<strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Critical</strong>ly<br />

1 You can do this exercise by yourself<br />

or with a classmate. This exercise<br />

requires watching TV for two hours.<br />

Begin with a clean piece of paper and<br />

draw a line down the page. Mark one<br />

side + and the other –. With pencil and<br />

paper in hand, watch CBS, NBC, or<br />

ABC or a cable network that shows<br />

commercials along with its regular programming.<br />

Pay close attention to the<br />

commercials, not the regular programming.<br />

Note each of the people who<br />

appear on screen. If you judge that a<br />

person is portrayed as a strong critical<br />

thinker, note it (e.g., Woman in car commercial<br />

+). If you think a person is portrayed<br />

as a weak critical thinker, note<br />

that (e.g., Three guys in beer commercial<br />

2 2 2). If you cannot tell (e.g., in<br />

the car commercial there were two kids<br />

riding in the back seat but they were<br />

not doing or saying anything), do not<br />

make any notation. After watching only<br />

the commercials during one hour of<br />

How Does TV Portray <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

programming, total up the plusses and<br />

the minuses. Now do the same thing for<br />

another hour, but this time pay attention<br />

only to the regular programming,<br />

not the commercials. Again note every<br />

character who appears and indicate on<br />

the paper if the person is portrayed as<br />

a strong critical thinker (e.g., evil bad<br />

guy +, clever detective +) or a weak<br />

critical thinker (e.g., victim who foolishly<br />

walked into the dark alley alone –). Tally<br />

up the plusses and minuses. Based on<br />

your observations, is there a tendency<br />

or pattern that might be evident regarding<br />

the critical thinking strengths or<br />

weaknesses of children, adolescents,<br />

young adults, middle-aged people, and<br />

senior citizens<br />

2 Group Project – 4-page mini-paper:<br />

Attitudes, while not immutable, are<br />

shaped and formed as we mature. To<br />

the extent that the disposition toward<br />

critical thinking is attitudinal, it can be<br />

affected by our experiences growing<br />

up. Begin by locating research reports<br />

(not just opinion pieces) in which credible<br />

experts report findings based on<br />

solid data about the impact of the<br />

images of ourselves we see on television<br />

and whether those images influence<br />

how we behave. Research on the<br />

power of TV stereotypes, for example,<br />

can be a good place to start. Consider<br />

what you learn through your review of<br />

the materials you found, and drawing<br />

too on your own life experience, formulate<br />

your response to this question:<br />

What is the potential impact that the<br />

characters portrayed on TV have on<br />

the disposition toward critical thinking,<br />

which is developing in adolescents<br />

Explain your opinion on this by providing<br />

reasons, examples, and citations.<br />

In the last part of your short paper,<br />

respond to this question: What kind<br />

of evidence would lead you to revise<br />

or reverse the opinion you have been<br />

presenting and explaining<br />

25<br />

In Philadelphia, the plaintiff, played by Tom Hanks, and his lawyer, played by Denzel Washington, wade through a<br />

crowd of reporters. How does Denzel Washington’s character use critical thinking throughout the course of the film<br />

“The expressions mental disciplines<br />

and mental virtues can be used to<br />

refer to habits of mind as well. The<br />

word disciplines in a military context<br />

and the word virtues in an ethical<br />

context both suggest something<br />

positive. We will use habits of mind<br />

because the word habit is neutral.<br />

Some habits are good, others bad.<br />

As will become evident, the same<br />

can be said with regard to critical<br />

thinking habits of mind. Some, like<br />

truth-seeking, are positive. Others,<br />

like indifference or intellectual<br />

dishonesty, are negative.”<br />

IS A GOOD CRITICAL THINKER<br />

AUTOMATICALLY A GOOD PERSON<br />

<strong>Thinking</strong> about Denzel Washington’s character in Philadelphia<br />

raises the natural question about how critical thinking<br />

might or might not be connected with being an ethical<br />

person. We have been using the expression “strong critical<br />

thinker” instead of “good critical thinker” because of the ambiguity<br />

of the word good. We want to praise the person as a<br />

critical thinker without necessarily making a judgment about<br />

the person’s ethics. For example, a person can be adept at<br />

developing cogent arguments and very adroit at finding the<br />

flaws in other people’s reasoning, but that same person can<br />

use these skills unethically to mislead and exploit a gullible<br />

person, perpetrate a fraud, or deliberately confuse, confound,<br />

and frustrate a project.<br />

A person can be strong at critical thinking, meaning that the<br />

person can have the appropriate dispositions, and be adept<br />

using his or her critical thinking skill, but still not be an ethical<br />

critical thinker. There have been people with superior thinking<br />

skills and strong habits of mind who, unfortunately, have<br />

used their talents for ruthless, horrific, and immoral purposes.<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Habits of Mind<br />

BUILDING POSITIVE HABITS<br />

Positive<br />

Truth-seeking<br />

Open-minded<br />

Analytical<br />

Negative<br />

Intellectually Dishonest<br />

Intolerant<br />

Heedless of Consequences<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> thinking skills can be strengthened by exercising<br />

them, which is what the examples and the exercises in this<br />

book are intended to help you do. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking habits of<br />

mind can be nurtured by internalizing the values that they<br />

embody and by reaffirming the intention each day to live by<br />

those values. vii Here are four specific suggestions about how<br />

to go about this.<br />

Chapter 02 26<br />

Systematic<br />

Confident in Reasoning<br />

Inquisitive<br />

Judicious<br />

Disorganized<br />

Hostile toward Reason<br />

Indifferent<br />

Imprudent<br />

To get some sense of the colossal<br />

problems that result from our<br />

collective failures to anticipate<br />

consequences, watch the<br />

documentary film The Unforeseen<br />

(2007, directed by Laura Dunn). It is<br />

the remarkable story of the loss of<br />

quality of life and environmental<br />

degradation associated with real<br />

estate development in Austin,<br />

Texas, over the past 50 years.<br />

It would be great if experience, knowledge, mental horsepower,<br />

and ethical virtue were all one and the same. But they are not.<br />

Consider, for example, the revelations that Victor Crawford, a<br />

tobacco lobbyist, makes in the clip from his 60 Minutes interview<br />

with Leslie Stahl. You can access a transcript of the interview<br />

at www.mythinkinglab.com. He admits that he lied, falsified<br />

information, and manipulated people in order to advance the<br />

interests of the tobacco indu stry. Ms. Stahl calls him out, saying<br />

that he was unethical and despicable to act that way. Crawford<br />

admits as much. He used his critical thinking skills to help<br />

sell people a product that, if used as intended by its manufacturer,<br />

was apt to cause them grave harm. Now, all these years<br />

later, he regrets having done that. The interview is part of his<br />

effort to make amends for his lies and the harm they may have<br />

caused to others. www.mythinkinglab.com and some printed<br />

versions of this book include a chapter exploring the relationship<br />

between critical thinking and ethical decision making more<br />

deeply.<br />

Read the Document on mythinkinglab.com<br />

1 Value <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong>. If we value critical thinking, we<br />

desire to be ever more truth-seeking, open-minded, mindful<br />

of consequences, systematic, inquisitive, confident in<br />

our critical thinking, and mature in our judgment. We will<br />

expect to manifest that desire in what we do and in what<br />

we say. We will seek to improve our critical thinking skills.<br />

2 Take Stock. It is always good to know where we are in<br />

our journey. The “<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Disposition</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-<strong>Rating</strong><br />

<strong>Form</strong>,” presented earlier in this chapter (page 21), will<br />

give us a rough idea. If we have general positive critical<br />

thinking habits of mind, that should show up in the score<br />

we give ourselves using this self-rating form.<br />

3 Be Alert for Opportunities. Each day be alert for opportunities<br />

to act on the desire by translating it into words and<br />

actions. Make a conscious effort each day to be as reflective<br />

and thoughtful as possible in addressing at least one<br />

of the many problems or decisions of the day.<br />

4 Forgive and Persist. Forgive yourself if you happen to<br />

backslide. Pick yourself up and get right back on the<br />

path. These are ideals we are striving to achieve. We each<br />

need discipline, determination, and persistence. There<br />

will be missteps along the way, but do not let them deter<br />

you. Working with a friend, mentor, or role model might<br />

make it easier to be successful, but it is really about what<br />

you want for your own thinking process.<br />

The Experts Worried That Schooling Might Be Harmful!<br />

The critical thinking expert panel we talked<br />

about in Chapter 1 was absolutely convinced<br />

that critical thinking is a pervasive and purposeful<br />

human phenomenon. They insisted<br />

that strong critical thinkers should be characterized<br />

not merely by the cognitive skills they<br />

may have, but also by how they approach life<br />

and living in general.<br />

This was a bold claim. At that time schooling<br />

in most of the world was characterized by<br />

the memorization of received truths. In the<br />

USA, the “back to basics” mantra echoed the<br />

pre-1960s Eisenhower era, when so much of<br />

schooling was focused on producing “interchangeable<br />

human parts” for an industrial<br />

manufacturing economy. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking that<br />

frees the mind to ask any question and evaluate<br />

any assumption naturally goes far beyond<br />

what the typical classroom was delivering. In<br />

fact, many of the experts feared that some of<br />

the things people experience in our schools<br />

could actually be harmful to the development<br />

and cultivation of strong critical thinking.<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> thinking came before formal schooling<br />

was invented. It lies at the very roots of<br />

civilization. The experts saw critical thinking<br />

as a driving force in the human journey from<br />

ignorance, superstition, and savagery toward<br />

global understanding. Consider what life would<br />

be like without the things on this list, and you<br />

will appreciate why they had such confidence<br />

in strong critical thinking. The approaches to<br />

life and living which the experts said characterized<br />

the strong critical thinker included:<br />

• inquisitiveness and a desire to remain<br />

well-informed with regard to a wide range<br />

of topics,<br />

• trust in the processes of reasoned inquiry,<br />

• self-confidence in one’s own abilities to<br />

reason,<br />

• open-mindedness regarding divergent<br />

world views,<br />

• flexibility in considering alternatives and<br />

opinions,<br />

• understanding of the opinions of other<br />

people,<br />

• fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning,<br />

• honesty in facing one’s own biases,<br />

prej udices, stereotypes, or egocentric<br />

tendencies,<br />

• prudence in suspending, making, or altering<br />

judgments,<br />

• willingness to reconsider and revise views<br />

where honest reflection suggests that<br />

change is warranted,<br />

• alertness to opportunities to use critical<br />

thinking.<br />

The experts went beyond approaches to<br />

life and living in general to emphasize how<br />

strong critical thinkers approach specific<br />

issues, questions, or problems. The experts<br />

said we would find strong critical thinkers<br />

striving for:<br />

• clarity in stating the question or concern,<br />

• orderliness in working with complexity,<br />

• diligence in seeking relevant information,<br />

• reasonableness in selecting and applying<br />

criteria,<br />

• care in focusing attention on the concern<br />

at hand,<br />

• persistence though difficulties are<br />

encountered,<br />

• precision to the degree permitted by the<br />

subject and the circumstances.<br />

Table 5, page 25. American Philosophical Association.<br />

1990, <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong>: An Expert<br />

Consensus Statement for Purposes of Educational<br />

Assessment and Instruction. ERIC<br />

Doc. ED 315 423.<br />

Putting the Positive <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Habits of Mind into Practice<br />

Here are a few suggestions about ways<br />

to translate each of the seven positive<br />

aspects of the disposition toward critical<br />

thinking into action.<br />

Truth-seeking – Ask courageous and<br />

probing questions. Think deeply about the<br />

reasons and evidence for and against a given<br />

decision you must make. Pick one or two of<br />

your own most cherished beliefs and ask yourself<br />

what reasons and what evidence there are<br />

for those beliefs.<br />

Open-mindedness – Listen patiently to<br />

someone who is offering opinions with which<br />

you do not agree. As you listen, show respect<br />

and tolerance toward the person offering the<br />

ideas. Show that you understand (not the same<br />

as “agree with”) the opinions being presented.<br />

Analyticity – Identify an opportunity to<br />

consciously pause to ask yourself about all<br />

the foreseeable and likely consequences of a<br />

decision you are making. Ask yourself what<br />

that choice, whether it be large or small, will<br />

mean for your future life and behavior.<br />

Systematicity – Focus on getting more<br />

organized. Make lists of your most urgent<br />

work, family and educational responsibilities,<br />

and your assignments. Make lists of the most<br />

important priorities and obligations as well.<br />

Compare the urgent with the important. Budget<br />

time to take a systematic and methodical<br />

approach to fulfilling obligations.<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Confidence – Commit<br />

to resolve a challenging problem by reasoning<br />

it through. Embrace a question, problem,<br />

or issue that calls for a reasoned decision<br />

and begin working on it yourself or in collaboration<br />

with others.<br />

Inquisitiveness – Learn something new.<br />

Go out and seek information about any topic<br />

of interest, but not one that you must learn<br />

about for work, and let the world surprise you<br />

with its variety and complexity.<br />

Judiciousness – Revisit a decision you<br />

made recently and consider whether it is still<br />

the right decision. See if any relevant new information<br />

has come to light. Ask if the results<br />

that had been anticipated are being realized.<br />

If warranted, revise the decision to better<br />

suit your new understanding of the state of<br />

affairs.<br />

•••<br />

27<br />

What Is Wrong with These Statements<br />

Each of the following statements contains<br />

a mistake. Identify the mistake and edit the<br />

statement so that it is more accurate.<br />

1 Having a “critical spirit” means one is<br />

a cynic.<br />

2 <strong>Critical</strong> thinking habits of mind are always<br />

positive.<br />

3 If you are open-minded, you must be<br />

a truth-seeker. Hint: open-mindedness<br />

is passive.<br />

4 Calling on people to be systematic means<br />

that everyone must think the same way.<br />

5 If a person is confident in his or her<br />

critical thinking, then he or she must<br />

have strong critical thinking skills.<br />

6 If a person has strong critical thinking<br />

skills, then he or she must be confident<br />

in his or her critical thinking.<br />

7 Truth-seeking is fine up to a point, but<br />

we have to draw the line. Some questions<br />

are too dangerous to be asked.<br />

8 People with strong desire to be<br />

analytical have the skill to foresee<br />

the consequences of options and<br />

events.<br />

9 If a person can see the value of critical<br />

thinking, then the person is disposed<br />

toward critical thinking. That’s all it<br />

takes.<br />

10 People who have not taken a course<br />

in critical thinking cannot have strong<br />

critical thinking skills.<br />

Chapter 02 28<br />

If you feel comfortable with the<br />

idea, you may want to ask a close<br />

friend or two to rate you using the<br />

“<strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> <strong>Disposition</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-<br />

<strong>Rating</strong> <strong>Form</strong>.” To do this your friend<br />

would replace the words I or my with<br />

references to you. This assessment<br />

could provide valuable information<br />

about how your critical thinking<br />

disposition manifests itself to others.<br />

When thinking critically, we apply these six skills to:<br />

• Evidence (facts, experiences, statements)<br />

• Conceptualizations (ideas, theories, ways of seeing the world)<br />

• Methods (strategies, techniques, approaches)<br />

• Criteria<br />

(standards, benchmarks, expectations)<br />

• Context<br />

(situations, conditions, circumstances)<br />

We are expected to ask a lot of tough questions about all<br />

five areas. For example, How good is the evidence Do these<br />

concepts apply Were the methods appropriate Are there<br />

better methods for investigating this question What standard<br />

of proof should we be using How rigorous should we be<br />

What circumstantial factors might lead us to revise our opinions<br />

Good critical thinkers are ever-vigilant, monitoring and<br />

correcting their own thinking.<br />

Core <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Skills<br />

We have talked about the “eager” in the phrase “skilled and<br />

eager” to think critically. Now let’s explore the “skilled” part<br />

by examining those mental skills which are at the core of<br />

purposeful reflective judgment.<br />

INTERPRETING AND ANALYZING<br />

THE CONSENSUS STATEMENT<br />

When thinking about the meaning and importance of the term<br />

“critical thinking” in Chapter 1, we referred to an expert consensus.<br />

That consensus identified certain cognitive skills as<br />

being central to critical thinking. Their research findings are<br />

shown below. viii<br />

Let’s unpack their quote. The experts identify six skills:<br />

• Interpretation<br />

• Analysis<br />

• Inference<br />

• Evaluation<br />

• Explanation<br />

• <strong>Self</strong>-Regulation<br />

THE JURY IS DELIBERATING<br />

In 12 Angry Men by Reginal Rose a jury deliberates the guilt or<br />

innocence of a young man accused of murder. ix The jury room<br />

is hot, the hour is late, and tempers are short. Ten of the twelve<br />

jurors have voted to convict when we join the story. In the classic<br />

American film version of Rose’s play, one of the two jurors<br />

who are still uncertain is Henry Fonda’s character. x That character<br />

first analyzes the testimony of a pair of witnesses, putting<br />

what each said side by side. Using all his critical thinking skills,<br />

he tries to reconcile their conflicting testimony. He asks how the<br />

old man could possibly have heard the accused man threaten<br />

the victim with the El Train roaring by the open window. From<br />

the facts of the situation Fonda’s character has inferred that<br />

the old man could not have been telling the truth. Fonda then<br />

explains that inference to the other jurors with a flawless argument.<br />

But the other jurors still want to know why an old man<br />

with apparently nothing to gain would not tell the truth. One of<br />

the other jurors, an old man himself, interprets that witness’s<br />

behavior for his colleagues. The conversation then turns to the<br />

The jury has the authority to question the quality of the<br />

evidence, to dispute the competing theories of the case that<br />

are presented by the prosecution and the defense, to find fault<br />

with the investigatory methods of the police, to dispute whether<br />

the doubts some members may have meet the criterion of<br />

“reasonable doubt” or not, and to take into consideration all<br />

the contextual and circumstantial elements that may be relevant.<br />

In other words, a good jury is the embodiment of good<br />

critical thinking that a group of people practice. The stronger<br />

their collective skills, the greater the justice that will be done.<br />

Access the El Train video clip from 12 Angry Men at www.<br />

mythinkinglab.com. Watch the Video on mythinkinglab.com<br />

CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS FIRE<br />

IN MANY COMBINATIONS<br />

question of how to interpret the expression “I’m going kill you!”<br />

that the accused is alleged to have shouted. One juror wants<br />

to take it literally as a statement of intent. Another argues that<br />

context matters, that words and phrases cannot always be<br />

taken literally. Someone asks why the defense attorney did not<br />

bring up these same arguments during his cross examination<br />

of the witness. In their evaluation, the jury does seem to agree<br />

on the quality of the defense—namely, that it was poor. One<br />

juror draws the conclusion that this means the lawyer thought<br />

his own client was guilty. But is that so Could there be some<br />

other explanation or interpretation for the half-hearted defense<br />

“We understand critical thinking<br />

to be purposeful, self-regulatory<br />

judgment which results in<br />

interpretation, analysis, evaluation,<br />

and inference, as well as explanation<br />

of the evidential, conceptual,<br />

methodological, criteriological, or<br />

contextual considerations upon<br />

which that judgment is based.”<br />

— The Delphi Report, American<br />

Philosophical Association xi<br />

One way to present critical thinking skills is in the form of a<br />

list. But lists typically suggest that we move from one item to<br />

another in a predetermined step-by-step progression, similar<br />

to pilots methodically working down the mandatory list of preflight<br />

safety checks. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking is not rote or scripted in<br />

the way that a list of skills might suggest.<br />

<strong>Critical</strong> thinking is a form of judgment—namely reflective,<br />

purposeful judgment. The skills are what we use to<br />

make that judgment. Imagine for a moment what it is like<br />

looking for an address while driving on a busy and unfamiliar<br />

street. To do this, we must simultaneously be coordinating<br />

the use of many skills, but fundamentally our focus<br />

is on the driving and not on the individual skills. We are<br />

concentrating on street signs and address numbers while<br />

also interpreting traffic signals such as stoplights, and controlling<br />

the car’s speed, direction, and location relative to<br />

other vehicles. Driving requires coordinating physical skills<br />

such as how hard to press the gas or tap the brakes and<br />

mental skills such as analyzing the movement of our vehicle<br />

relative to those around ours to avoid accidents.<br />

In the end, however, we say that we drove the car to the<br />

destination. We do not list all the skills, and we certainly do<br />

not practice them one by one in a serial order. Rather, we<br />

use them all in concert. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking has certain important<br />

features in common with looking for an address while<br />

driving on a busy and unfamiliar street. The key similarity to<br />

notice here is that critical thinking requires using all the skills<br />

in concert, not one at a time sequentially.<br />

The intricate interaction of critical thinking skills in real-life<br />

problem solving and decision making may begin with an analysis,<br />

an interpretation, an inference, or an evaluation. Then, using<br />

self-regulation, we may go back and check ourselves for accuracy.<br />

On other occasions, we may first draw an inference on the<br />

basis of an interpretation and then evaluate our own inference.<br />

We may be explaining our reasoning to someone and realize,<br />

because we are monitoring our own thinking, that our reasoning<br />

is not adequate. And this may lead us to recheck our analyses or<br />

our inferences to see where we may need to refine our thinking.<br />

29<br />

Chapter 02 30<br />

That was what the jury, considered as a whole, was doing in 12<br />

Angry Men—going back and forth among interpretation, analysis,<br />

inference, and evaluation, with Henry Fonda’s character<br />

as the person who called for more careful self-monitoring and<br />

self-correction. The jury’s deliberation demanded reflection and<br />

an orderly analysis and evaluation of the facts, but deliberation<br />

is not constrained by adherence to a predetermined list or sequencing<br />

of mental events. Nor is critical thinking.<br />

No, it would be an unfortunate and misleading oversimplification<br />

to reduce critical thinking to a list of skills, such as the<br />

recipe on the lid of dehydrated soup: first analyze, then infer,<br />

then explain, then close the lid and wait five minutes. To avoid<br />

the misimpressions that a list might engender, we need some<br />

other way of displaying the names of the skills.<br />

We xii have always found it helpful when talking with college<br />

students and faculty around the world about critical thinking skills<br />

to use the metaphor of a sphere with the names of the skills displayed<br />

randomly over its surface. xiii Why a sphere Three reasons.<br />

• First, organizing the names of the skills on a sphere is truer<br />

to our lived experience of engaging in reflective judgment,<br />

as indicated above. We have all experienced those moments<br />

when, in the mental space of a few seconds, our<br />

minds fly from interpretation to analysis to inference and<br />

evaluation as we try to sort out our thoughts before we<br />

commit ourselves to a particular decision. We may go back<br />

and forth interpreting what we are seeing, analyzing ideas<br />

and drawing tentative inferences, trying to be sure that we<br />

have things right before we make a judgment.<br />

• Second, a sphere does not presume any given order of<br />

events, which, for the present, is truer to the current state<br />

of the science.<br />

• Third, a sphere reminds us about another important characteristic<br />

of critical thinking skills, namely that each can be<br />

applied to the other and to themselves. xiv We can analyze<br />

Core <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

Skills Interact<br />

Professionals Measure Outcomes<br />

Musicians<br />

Salesperson<br />

Athletes<br />

Nurses<br />

Teachers<br />

Soldiers<br />

our inferences. We can analyze our analyses. We can explain<br />

our interpretations. We can evaluate our explanations.<br />

We can monitor those processes and correct any mistakes<br />

we might see ourselves making. In this way, the core critical<br />

thinking skills can be said to interact.<br />

STRENGTHENING OUR CORE<br />

CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS<br />

Quality of<br />

the concert<br />

Number of<br />

sales<br />

Games won<br />

Health care<br />

outcomes<br />

achieved<br />

<strong>Learning</strong><br />

accomplished<br />

Success of<br />

the mission<br />

Musicians, salespeople, athletes, nurses, teachers, and soldiers<br />

strive to improve their likelihood of success by strengthening<br />

the skills needed in their respective professions. Even<br />

as they train in one skill or another, working people must not<br />

lose sight of how those skills come together in their professional<br />

work. The quality of the concert, the number of sales<br />

made, the games won, the health care outcomes achieved,<br />

the learning accomplished, and the success of the mission—<br />

these are the outcomes that count. The same holds for critical<br />

thinkers. Success consists of making well-reasoned, reflective<br />

judgments to solve problems effectively and to make good<br />

decisions. <strong>Critical</strong> thinking skills are the tools we use to accomplish<br />

those purposes. In the driving example, our attention<br />

was on the challenges associated with reaching the intended<br />

street address. In real-world critical thinking, our attention will<br />

be on the challenges associated with solving the problem or<br />

making the decision at hand.<br />

THE ART OF THE GOOD QUESTION<br />

There are many familiar questions that invite people to use<br />

their critical thinking skills. We can associate certain questions<br />

with certain skills. The table below gives some examples. xv<br />

Often, our best critical thinking comes when we ask the right<br />

questions. xvi<br />

Asking good questions, ones that promote critical thinking,<br />

is a highly effective way to gather important information<br />

about a topic, to probe unspoken assumptions, to clarify issues<br />

and to explore options. Asking good questions promotes<br />

strong problem solving and decision making, particularly<br />

when we encounter unfamiliar issues or significant problems.<br />

Questions to Fire Up Our <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Skills<br />

Interpretation<br />

Analysis<br />

• What does this mean<br />

• What’s happening<br />

• How should we understand that (e.g., what he or she just said)<br />

• What is the best way to characterize/categorize/classify this<br />

• In this context, what was intended by saying/doing that<br />

• How can we make sense out of this (experience, feeling, statement)<br />

• Please tell us again your reasons for making that claim.<br />

• What is your conclusion/What is it that you are claiming<br />

• Why do you think that<br />

• What are the arguments pro and con<br />

• What assumptions must we make to accept that conclusion<br />

• What is your basis for saying that<br />

Inference<br />

Evaluation<br />

• Given what we know so far, what conclusions can we draw<br />

• Given what we know so far, what can we rule out<br />

• What does this evidence imply<br />

• If we abandoned/accepted that assumption, how would things change<br />

• What additional information do we need to resolve this question<br />

• If we believed these things, what would they imply for us going forward<br />

• What are the consequences of doing things that way<br />

• What are some alternatives we haven’t yet explored<br />

• Let’s consider each option and see where it takes us.<br />

• Are there any undesirable consequences that we can and should foresee<br />

• How credible is that claim<br />

• Why do we think we can trust what this person claims<br />

• How strong are those arguments<br />

• Do we have our facts right<br />

• How confident can we be in our conclusion, given what we now know<br />

31<br />

Explanation<br />

• What were the specific findings/results of the investigation<br />

• Please tell us how you conducted that analysis.<br />

• How did you come to that interpretation<br />

• Please take us through your reasoning one more time.<br />

• Why do you think that (was the right answer/was the solution)<br />

• How would you explain why this particular decision was made<br />

<strong>Self</strong>-Regulation<br />

• Our position on this issue is still too vague; can we be more precise<br />

• How good was our methodology, and how well did we follow it<br />

• Is there a way we can reconcile these two apparently conflicting conclusions<br />

• How good is our evidence<br />

• OK, before we commit, what are we missing<br />

• I’m finding some of our definitions a little confusing; can we revisit what we mean by certain things before making<br />

any final decisions<br />

Source: © 2009. Test Manual for the California <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Skills Test, published by Insight Assessment. Used with permission.<br />

Ask Good <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Questions<br />

Chapter 02 32<br />

Using the discussion about shale gas drilling<br />

as an example, practice formulating good<br />

critical thinking questions about the topics<br />

listed below. Look too at the table entitled<br />

“Questions to Fire Up Our <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

Skills” on page 31 to get ideas about how to<br />

target specific critical thinking skills with your<br />

questions. Write at least four good critical<br />

thinking questions about each of the topics<br />

below. The materials supporting this exerice<br />

are available at www.mythinkinglab.com.<br />

1 Perhaps with more foresight strong<br />

critical thinkers might have anticipated<br />

this problem. But when the onechild<br />

policy was put in place, China<br />

was also beginning to experience a<br />

phenomenon that has continued for<br />

many decades, namely the migration<br />

of young people into urban areas in<br />

search of better jobs and a lifestyle<br />

different from what is available “back<br />

on the farm.” Recently China was considering<br />

a regulation requiring children<br />

to visit their elderly parents who lived<br />

in the countryside. Review the story at<br />

www.mythinkinglab.com and then<br />

formulate good critical thinking questions<br />

about this policy and its the<br />

potential benefits and difficulties.<br />

Consider for a moment the topic of drilling to extract natural<br />

gas from shale. Natural gas as an alternative fuel source<br />

has not enjoyed the attention of the American population<br />

like solar energy or wind energy, mostly because it has been<br />

thought to be in short supply—until recently, that is. It turns<br />

out that natural gas can be harvested from shale rock formations<br />

two miles beneath the Earth’s surface. The technology<br />

behind shale gas drilling involves sideways drilling and a process<br />

called “fracking.” Over 30 states in the U.S. have underground<br />

shale beds and drilling in those regions has made<br />

2 USA Today reported that 40 percent<br />

of all pregnancies across the United<br />

States were “unwanted or mistimed.”<br />

The report was based on a study of<br />

86,000 women who gave birth and<br />

9,000 women who had abortions.<br />

The study itself appeared online in<br />

the journal Perspectives on Sexual<br />

and Reproductive Health. Review the<br />

study itself and the newspaper story<br />

at www.mythinkinglab.com and then<br />

about this phenomenon.<br />

3 The plant called quinoa offers “an exceptional<br />

balance of amino acids; quinoa,<br />

they declared, is virtually unrivaled<br />

in the plant or animal kingdom for its<br />

life-sustaining nutrients,” according<br />

to a New York Times story about the<br />

problems of too much success. As<br />

global demand skyrockets, quinoa producers<br />

and other Bolivians may not be<br />

receiving either the nutritional or the<br />

economic benefits of this crop. Learn<br />

more about quinoa and the problems of<br />

its success by reading the news story<br />

at www.mythinkinglab.com. Then<br />

formulate four good critical thinking<br />

questions about this issue. Let<br />

one of the questions be about the importance<br />

of foresightfulness.<br />

4 The Buddhist nation of Bhutan has a<br />

Commission for Gross National Happiness,<br />

and the head of that commission<br />

has a problem: Domestic violence appears<br />

to be rampant among a population<br />

whose religion abhors any kind<br />

of violence. Review the news story at<br />

from the perspective of the head<br />

of the Commission for Gross National<br />

Happiness.<br />

5 How could a voluntary parent participation<br />

program that resulted in increased<br />

test scores go so wrong That’s what<br />

parents and school administrators are<br />

asking themselves in San Jose, California.<br />

Read the story by Sharon Noguchi, which<br />

appeared in the June 16, 2011 San Jose<br />

Mercury News at www.mythinkinglab.<br />

com, and then formulate good critical<br />

thinking questions to further analyze what<br />

happened and to guide in the formulation<br />

of possible next steps to resolve the<br />

situation.<br />

some homeowners into overnight millionaires. The drilling<br />

has given a boost to the local economies in terms of jobs<br />

and retail sales. But, as reported by Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes,<br />

accidents and other safety concerns that have people<br />

who live in drilling communities concerned. Those living near<br />

shale gas drill sites are questioning the contamination of<br />

the drinking water by the chemicals involved in the fracking<br />

process. Go to www.mythinkinglab.com to listen to Lesley<br />

Stahl’s full report.<br />

Holistic <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong> Scoring Rubric<br />

1 Look at the descriptions of each of<br />

the four levels of the “Holistic <strong>Critical</strong><br />

<strong>Thinking</strong> Scoring Rubric” on page 12.<br />

In each, underline the elements that<br />

call out positive or negative critical<br />

thinking habits of mind.<br />

2 Go online and locate two editorials<br />

from this week’s New York Times or<br />

Washington Post. Select any issue or<br />

topic you wish. But find something<br />

that is controversial enough that the<br />

paper published at least one pro and<br />

one con editorial. Approach the two<br />

editorials with an open mind. Resist<br />

forming a judgment about the issue<br />

at least until you have read and considered<br />

both carefully. Evaluate both<br />

using the “Holistic <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Thinking</strong><br />

Scoring Rubric.” Explain in detail the<br />

reasons for the score you assigned.<br />

Before forming an opinion for or against fracking under<br />

residential real estate in your community, as a strong critical<br />

thinker you first would want to know more about this natural<br />

gas extraction method. Let’s try to think of good critical thinking<br />

questions to ask. You might ask “What is known about the<br />

environmental risks of the chemicals involved in the fracking<br />

processes” or “What exactly is involved in establishing a new<br />

drill site in my community” to promote interpretation. You<br />

could also ask “What are the statistics on the frequency and<br />

severity of the accidents and safety violations associated with<br />

shale gas drilling” to promote inference. Perhaps we would<br />

ask “If our community were to permit fracking, what would be<br />

the economic impact of that decision, and for whom, and how<br />

long would we have to wait before seeing those benefits”<br />

to promote evaluation. Or you could ask “Do my past statements<br />

in support of alternative energy policies, or my financial<br />

interests in residential real estate, or my fears for the health<br />

and safety of myself and my family bias my review of the information<br />

about shale gas drilling” to exercise our judiciousness<br />

habit of mind and our self-regulation skills.<br />

SKILLS AND SUBSKILLS DEFINED<br />

The six core critical thinking skills each has related subskills,<br />

as shown in the table below. The descriptions in the table<br />

of each core skill come from the expert consensus research discussed<br />

earlier. xvii The experts provided this more refined level of<br />

SKILL Experts’ Consensus Description Subskill<br />

Interpretation “To comprehend and express the meaning or significance of a wide variety of<br />

experiences, situations, data, events, judgments, conventions, beliefs, rules,<br />

procedures, or criteria”<br />

Categorize<br />

Decode significance<br />

Clarify meaning<br />

“To identify the intended and actual inferential relationships among statements,<br />

questions, concepts, descriptions, or other forms of representation intended to<br />

express belief, judgment, experiences, reasons, information, or opinions”<br />

Examine ideas<br />

Identify arguments<br />

Identify reasons and claims<br />

33<br />

“To identify and secure elements needed to draw reasonable conclusions; to form<br />

conjectures and hypotheses; to consider relevant information and to educe the<br />

consequences flowing from data, statements, principles, evidence, judgments, beliefs,<br />

opinions, concepts, descriptions, questions, or other forms of representation”<br />

“To assess the credibility of statements or other representations that are accounts<br />

or descriptions of a person’s perception, experience, situation, judgment, belief, or<br />

opinion; and to assess the logical strength of the actual or intended inferential relationships<br />

among statements, descriptions, questions, or other forms of representation”<br />

“To state and to justify that reasoning in terms of the evidential, conceptual,<br />

methodological, criteriological, and contextual considerations upon which one’s<br />

results were based; and to present one’s reasoning in the form of cogent arguments”<br />

Query evidence<br />

Conjecture alternatives<br />

Draw conclusions using inductive<br />

or deductive reasoning<br />

Assess credibility of claims<br />

Assess quality of arguments<br />

that were made using inductive<br />