Essay on Buddhism

Students are often asked to write an essay on Buddhism in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Buddhism

Introduction to buddhism.

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy that emerged from the teachings of the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) around 2,500 years ago in India. It emphasizes personal spiritual development and the attainment of a deep insight into the true nature of life.

Key Beliefs of Buddhism

Buddhism’s main beliefs include the Four Noble Truths, which explain suffering and how to overcome it, and the Noble Eightfold Path, a guide to moral and mindful living.

Buddhist Practices

Buddhist practices like meditation and mindfulness help followers to understand themselves and the world. It encourages love, kindness, and compassion towards all beings.

Impact of Buddhism

Buddhism has greatly influenced cultures worldwide, promoting peace, non-violence, and harmony. It’s a path of practice and spiritual development leading to insight into the true nature of reality.

250 Words Essay on Buddhism

Buddhism, a major world religion, emerged from the profound teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, a prince from the Indian subcontinent, around the 5th century BCE. It is not merely a religion but a philosophy and a way of life, focusing on the alleviation of suffering.

The Four Noble Truths

At the heart of Buddhism lie the Four Noble Truths. The first truth recognizes the existence of suffering (Dukkha). The second identifies the cause of suffering, primarily desire or attachment (Samudaya). The third truth, cessation (Nirodha), asserts that ending this desire eliminates suffering. The fourth, the path (Magga), outlines the Eightfold Path as a guide to achieve this cessation.

The Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path, as prescribed by Buddha, is a practical guideline to ethical and mental development with the goal of freeing individuals from attachments and delusions; ultimately leading to understanding, compassion, and enlightenment (Nirvana). The path includes Right Understanding, Right Intent, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Buddhists practice meditation and mindfulness to achieve clarity and tranquility of mind. They follow the Five Precepts, basic ethical guidelines to refrain from harming living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxication.

Buddhism is a path of practice and spiritual development leading to insight into the true nature of reality. It encourages individuals to lead a moral life, be mindful and aware of thoughts and actions, and to develop wisdom and understanding. The ultimate goal is the attainment of enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth and death.

500 Words Essay on Buddhism

Introduction.

Buddhism, a religion and philosophy that emerged from the teachings of the Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), has become a spiritual path followed by millions worldwide. It is a system of thought that offers practical methodologies and profound insights into the nature of existence.

The Life of Buddha

The Buddha, born in the 5th century BCE in Lumbini (present-day Nepal), was a prince who renounced his royal comforts in search of truth. After years of rigorous ascetic practices and meditation, he attained ‘Enlightenment’ under the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, India. His teachings, known as ‘Dhamma,’ are centered around the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, providing a roadmap to end suffering and achieve Nirvana.

The Four Noble Truths are the cornerstone of Buddhism. They outline the nature of suffering (Dukkha), its origin (Samudaya), its cessation (Nirodha), and the path leading to its cessation (Magga). These truths present a pragmatic approach, asserting that suffering is an inherent part of existence, but it can be overcome by following the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path, as taught by Buddha, is a practical guideline to ethical and mental development with the goal of freeing individuals from attachments and delusions, ultimately leading to understanding, compassion, and enlightenment. It includes Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Buddhist Schools of Thought

Buddhism evolved into various schools of thought, each interpreting Buddha’s teachings differently. The two main branches are Theravada, often considered the closest to the original teachings, and Mahayana, which includes Zen, Pure Land, and Tibetan Buddhism. Vajrayana, often considered part of Mahayana, incorporates esoteric practices and is dominant in Tibet.

Buddhism and Modern Science

The compatibility of Buddhism with modern science has been a topic of interest in recent years. Concepts like impermanence, interconnectedness, and the nature of consciousness in Buddhism resonate with findings in quantum physics, neuroscience, and psychology. This convergence has led to the development of fields like neurodharma and contemplative science, exploring the impact of meditation and mindfulness on the human brain.

Buddhism, with its profound philosophical insights and practical methodologies, continues to influence millions of people worldwide. Its teachings provide a framework for understanding the nature of existence, leading to compassion, wisdom, and ultimately, liberation. As we delve deeper into the realms of modern science, the Buddhist worldview continues to offer valuable perspectives, underscoring its enduring relevance in our contemporary world.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Books

- Essay on Bipolar Disorder

- Essay on Biology

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

One Comment

Easy to understand thank u😍😍🙏🙏🙏

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Scientific Outlook Of Buddhism

by Wang Chi Biu | 2003 | 22,992 words

English Translation By P. H. Wei Update: 01-09-2003...

Buddhism is profound, superb and wonderful. However, it is very much distorted and misinterpreted. The common misconception is held by a great many people (Group A) that in the wake of advanced development of science today, Buddhism, which promotes superstition, would become obsolete. On the other hand, some other people (Group B) cherish the notion that insofar as Buddhism is established on theological basis, with a view of spreading its moral teaching, it is not without a good measure of spiritual value to humanity. Whereas the criticism of Group A show sheer ignorance of Buddhism, apparently, the remark of Group B is paradoxical. In view of these misconceptions, the writer therefore presented his understanding of Buddhism based on direct perception from the scientific point of view. To Group A he would like to say that Buddhism is not only devoid of superstition, but on the contrary, is the best cure for every superstition in our world, because its Teaching is absolutely logical, impartial and rational. For the understanding of Group B, he would say that Buddhism is neither a theological religion nor a neurothesia for mental ills, but a Subject of Study, similar to science, to probe into the truths of life and the universe; apart from its extraordinary functions and extensive application, it is a wholesome, practical Way of Living to be realized by self experiencing only.

From the preceding chapters, it may summed up that as a religion, Buddhism is based on absolute freedom and true equality; it is rational, liberal, objective, concrete, complete, positive, pragmatic and applicable at all levels. As a token of the writer" profound gratitude, this page is most sincerely and respectfully presented; may it gladden all those who have read it, enhance their faith and fortify their resolution to live up to the Buddhist Way of Life.

Blessings to All.

Article published on 23 August, 2009

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

- Introduction

- Buddhism in America

- The Buddhist Experience

- Issues for Buddhists in America

The Path of Awakening

Prince Siddhartha: Renouncing the World

Becoming the “Buddha”: The Way of Meditation

The Dharma: The Teachings of the Buddha

The Sangha: The Buddhist Community

The Three Treasures

The Expansion of Buddhism

As Buddhism spread through Asia, it formed distinct streams of thought and practice: the Theravada ("The Way of the Elders" in South and Southeast Asia), the Mahayana (the “Great Vehicle” in East Asia), and the Vajrayana (the “Diamond Vehicle” in Tibet), a distinctive and vibrant form of Mahayana Buddhism that now has a substantial following. ... Read more about The Expansion of Buddhism

Theravada: The Way of the Elders

Mahayana: The Great Vehicle

Vajrayana: The Diamond Vehicle

Buddhists in the American West

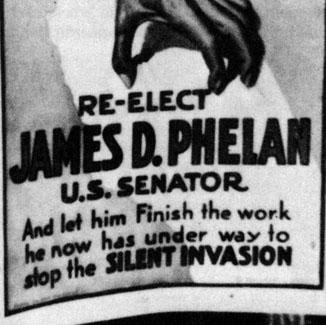

Discrimination and Exclusion

East Coast Buddhists

At the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions

The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions, held at that year's Chicago World’s Fair, gave Buddhists from Sri Lanka and Japan the chance to describe their own traditions to an audience of curious Americans. Some stressed the universal characteristics of Buddhism, and others criticized anti-Japanese sentiment in America. ... Read more about At the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions

Internment Crisis

Building “American Buddhism”

New Asian Immigration and the Temple Boom

Popularizing Buddhism

The Image of the Buddha

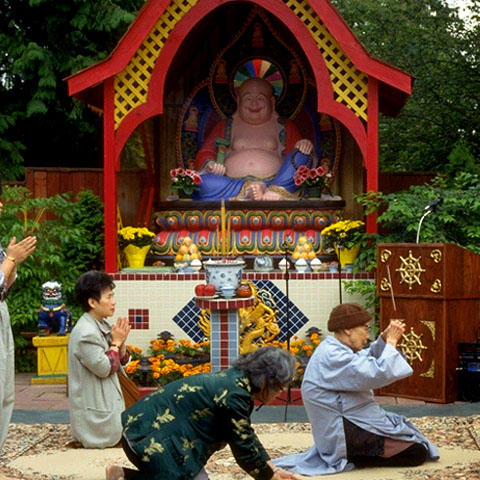

Ever since the first century, Buddhists have created images and other depictions of the Buddha in metal, wood, and stone with stylized hand-positions called mudras . Images of the Buddha are often the focus of reverence and devotion. ... Read more about The Image of the Buddha

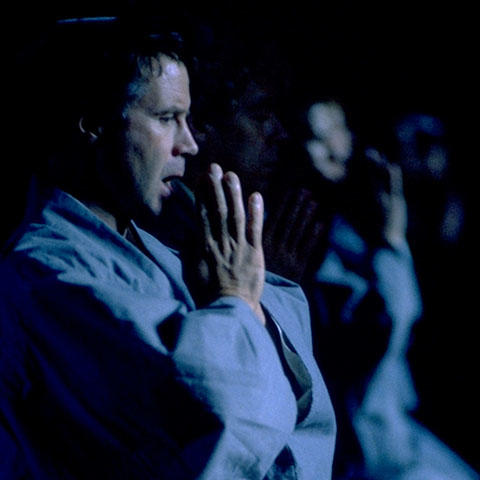

The Practice of Mindfulness

People commonly equate Buddhism with meditation, but historically very few Buddhists meditated. Those who did, however, drew from a long and rich tradition of Buddhist philosophical and contemplative practice. ... Read more about The Practice of Mindfulness

One Hand Clapping?

Sesshin: A Meditation Retreat

Intensive Zen meditation retreats, or sesshins , such as one in Mt. Temper, New York, are designed for participants to focus intensively on monastic Buddhist practice and meditation. Retreats include many rituals to allow students to fully immerse themselves in their practice—even during mealtime. ... Read more about Sesshin: A Meditation Retreat

Chanting the Sutras

Chanting scriptures and prayers to buddhas and bodhisattvas is a central practice in all streams of Buddhism, intended both to reflect upon content and to focus the mind. ... Read more about Chanting the Sutras

Creating a Mandala

Becoming a Monk

The many streams of Buddhism differ in their approaches to monasticism and initiation rituals. For example, is it common in the Theravada tradition for young men to become novice monks as a rite of passage into adulthood. In some Mahayana traditions, women can take the Triple Platform Ordination and become nuns. Meanwhile, in some Japanese traditions, priests and masters can marry and have children. ... Read more about Becoming a Monk

From Street Gangs to Temple

In Southern California, some Theravada temples have taken up the practice of granting temporary novice ordinations to Cambodian American gang members, with the hope of reorienting the youth toward their families’ religion and culture. ... Read more about From Street Gangs to Temple

Devotion to Guanyin

The compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, also known as Guanyin, is central to the practice of Chinese and Vietnamese Buddhists in America. A bodhisattva is an enlightened one who remains engaged in the world in order to enlighten all beings, and Buddhists channel the bodhisattva Guanyin by cultivating compassion for all beings in the world. ... Read more about Devotion to Guanyin

Buddha’s Birthday

Buddhists often consider the Buddha’s birthday an occasion for celebration, and Chinese, Thai, and Japanese temples in America all celebrate differently. ... Read more about Buddha’s Birthday

Remembering the Ancestors

Celebrating the New Year

Although the Lunar New Year is not a particularly “Buddhist” holiday, many Thai and Chinese Buddhists observe the occasion with celebration and visits to family and activities at Buddhist temples. ... Read more about Celebrating the New Year

Building a Pure Land on Earth

Pure Land Buddhists pay respect to Amitabha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, who created a paradise for Buddhist devotees called the “Land of Bliss.” Pure Land Buddhists in America seek to create a Pure Land here on Earth through ritual acts of devotion, care for animals and human beings, study, meditation, and acting compassionately in the public sphere. ... Read more about Building a Pure Land on Earth

Monastery in the Hudson Valley

The Chuang Yen Monastery in Kent, New York, is a prime example of how Chinese Buddhism has flourished in America, in all its richness and complexity. ... Read more about Monastery in the Hudson Valley

One Buddhism? Or Multiple Buddhisms?

There are two distinct but related histories of American Buddhism: that of Asian immigrants and that of American converts. The presence of the two communities raises such questions as: What is the difference between the Buddhism of American converts and Buddhism of Asian immigrant communities? How do we characterize the Buddhism of a new generation Asian-American youth—as a movement of preservation or transformation? ... Read more about One Buddhism? Or Multiple Buddhisms?

The Difficulties of a Monk

A reflection on American Buddhist monasticism from the Venerable Walpola Piyananda highlights the tensions that arise when immigrant Buddhism encounters American social customs that differ from those in Asia. ... Read more about The Difficulties of a Monk

Changing Patterns of Authority

American convert Buddhism and immigrant Asian Buddhism have dramatically different models of authority and institutional hierarchy. Buddhist organizations and communities in America are forced to attend to the question of how spiritual, social, financial, and organizational authorities will be dispersed among its leaders and members. ... Read more about Changing Patterns of Authority

Women in American Buddhism

American Buddhism has created new roles for women in the Buddhist tradition. American Buddhist women have been active in movements to revive the ordination lineages of Buddhist nuns in the Theravada and Vajrayana traditions. ... Read more about Women in American Buddhism

Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism

Pioneered by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh in the 1970s, “Engaged Buddhism” brings a Buddhist perspective to the ongoing struggle for social and environmental justice in America. ... Read more about Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism

Ecumenical and Interfaith Buddhism: Coming Together in America

Since the 1970s, Buddhist leaders from various traditions have engaged together in ecumenical councils and organizations to address prevalent challenges for Buddhism in North America. These events have brought together Buddhist traditions that, in the past, have had limited contact with one another. In addition, these groups have become involved in interfaith partnerships, particularly with Christian and Jewish organizations. ... Read more about Ecumenical and Interfaith Buddhism: Coming Together in America

Teaching the Love of Buddha: The Next Generation

How do Buddhists in America transmit their culture and tradition to new generations? In the Jodo Shinshu school of Japanese Buddhism, Sunday School classes have become an important religious educational tool to address this question, and its curriculum offers a particularly American approach to educating children about their tradition. ... Read more about Teaching the Love of Buddha: The Next Generation

Image Gallery

Awe and dread: How religions have responded to total solar eclipses over the centuries

Silicon valley start-up aims to unlock buddhist jhana states with tech, how lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune, is depicted in jainism and buddhism.

- Goldstein, Joseph

- Dharma school

- Eightfold Noble Path

- Maezumi-roshi, Taizan

Buddhism Timeline

7627213d930e1981366069359e5a876e, buddhism in the world (text), ca. 6th-5th c. bce life of siddhartha gautama, the buddha.

The dates of the Buddha remain a point of controversy within both the Buddhist and scholarly communities. Though many scholars today place the Buddha’s life between 460-380 BCE, according to one widely accepted traditional account, Siddhartha was born as a prince in the Shakya clan in 563 BCE. After achieving enlightenment at the age of 36, the Buddha spent the remainder of his life giving spiritual guidance to an ever-growing body of disciples. He is said to have entered into parinirvana (nirvana after death) in 483 BCE at the age of 81.

c. 480-380 BCE The First Council

Though specific dates are uncertain, a group of the Buddha’s disciples is said to have come together shortly after the Buddha’s parinirvana in hopes of establishing guidelines to ensure the continuity of the Sangha. According to tradition, as many as 500 prominent arhats gathered in Rajagriha to recite together and standardize the Buddha’s sutras (discourses on Dharma) and vinaya (rules of conduct).

c. 350 BCE The Second Council

It remains unclear if what is known as the Second Council refers to one particular assemblage of monks or if there were several meetings convened during the 4th century BCE to clarify points of controversy. It also remains unclear precisely what matters of doctrine or conduct were in dispute. What is clear is that this council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha, between the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika.

269-232 BCE The Spread of Buddhism Through South Asia

After witnessing the great bloodshed and suffering caused by his military campaigns, Indian Emperor Ashoka Maurya converted to Buddhism, sending missionaries throughout India and into present day Sri Lanka.

200 BCE-200 CE Emergence of Two Schools of Buddhism

Differing interpretations of the Buddha’s teachings resulted in the development of two main schools of Buddhism. The first branch, Mahayana, referred to itself as the “Great Vehicle,” and is today principally found in China, Korea, and Japan. The second branch comprised 18 schools, of which only one exists today — Theravada, or the “Way of the Elders.” Theravada Buddhism is presently followed in Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

65 CE First Mention of Buddhism in China

Han dynasty records note that Prince Ying of Ch’u, a half-brother of the Han emperor, provided a vegetarian feast for the Buddhist laity and monks living in his kingdom around 65 CE. This indicates that a Buddhist community had already formed there.

c. 100 CE Ashvaghosha Writes Buddhacarita

Among the early biographies of the Buddha was the Buddhacarita, written in Sanskrit by the Indian poet Ashvaghosha. Buddhacarita, literally “Life of the Buddha,” is regarded as one of the greatest epic poems of all history.

200s CE Nagarjuna Founds the Madhyamaka School

Nagarjuna is one of the most important philosophers of the Buddhist tradition. Based on his reading of the Perfection of Wisdom sutras, Nagarjuna argued that everything in the world is fundamentally sunya, or “empty” — that is, without inherent existence. This idea that the world is real yet radically impermanent and interdependent has played a central role in Buddhist philosophy.

372 CE Buddhism Introduced to Korea from China

In 372 CE the Chinese king Fu Chien sent a monk-envoy, Shun-tao, to the Koguryo court with Buddhist scriptures and images. Although all three of the kingdoms on the Korean peninsula soon embraced Buddhism, it was not until the unification of the peninsula under the Silla in 668 CE that the tradition truly flourished.

400s CE Buddhaghosa Systematizes Theravada Teachings

Buddhaghosa was a South Indian monk who played a formative role in the systematization of Theravada doctrine. After arriving in Sri Lanka in the early part of the fifth century CE, he devoted himself to editing and translating into Pali the scriptural commentaries that had accumulated in the native Sinhalese language. He also composed the Visuddhimagga, “Path of Purity,” an influential treatise on Theravada practice. From this point on, Theravada became the dominant form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and eventually spread to Southeast Asia.

402 CE Pure Land Buddhism Established in China

In 402 CE, Hui-yuan became the first Chinese monk to form a group specifically devoted to reciting the vow to be reborn in the Western Paradise, and founded the Donglin Temple at Mount Lu for this purpose. Subsequent practitioners of Pure Land Buddhism regard Hui-yuan as the school’s founder.

520 CE Bodhidharma and Ch’an (Zen) in China

The Ch’an (Zen) school attributes its establishment to the arrival of the monk Bodhidharma in Northern China in 520 CE. There, he is said to have spent nine years meditating in front of a wall before silently transmitting the Buddha’s Dharma to Shen-Kuang, the second patriarch. All Zen masters trace their authority to this line.

552 CE Buddhism Enters Japan from Korea

In 552 CE the king of Paekche sent an envoy to Japan in hopes of gaining military support. As gifts, he sent an image of Buddha, several Buddhist scriptures, and a memorial praising Buddhism. Within three centuries of this introduction, Buddhism would become the major spiritual and intellectual force in Japan.

700s CE Vajrayana Buddhism Emerges in Tibet

Buddhist teachings and practices appear to have first made their way into Tibet in the mid-7th century CE. During the reign of King Khri-srong (c. 740-798 CE), the first Tibetan monastery was founded and the first monk ordained. For the next four hundred years, a constant flow of Tibetan monks made their way to Northern India to study at the great Buddhist universities. It was from the university of Vikramasila around the year 767 that the yogin-magician Padmasambhava is said to have carried the Vajrayana teachings to Tibet, where they soon became the dominant form of Buddhism.

1044-1077 CE Theravada Buddhism Established in Burma

Theravada Buddhism was practiced in pockets of southern Burma since about the 6th century CE. However, when King Anawrahta ascended the throne in 1044, Shin Arahan, a charismatic Mon monk from Southern Burma, convinced the new monarch to establish a more strictly Theravadin expression of Buddhism for the entire kingdom. From that time on, Theravada would remain the tradition of the majority of the Burmese people.

c. 1050 CE Development of Jogye Buddhism in Korea

The Ch’an school, which first arrived in Korea from China in the 8th century CE, eventually established nine branches, known as the Nine Mountains. In the 11th century, these branches were organized into one system under the name of Jogye. Although all Buddhist teachings were retained, the kong-an (koan) practice of Lin-chi Yixuan gained highest stature as the most direct path to enlightenment.

1100s CE Pure Land Buddhism Established in Japan

Following a reading of a Chinese Pure Land text, the Japanese monk Honen Shonin (1133-1212 CE) became convinced that the only effective mode of practice was nembutsu: chanting the name of Amitabha Buddha. This soon became a dominant form of Buddhist practice in Japan.

1100s CE Rinzai School of Zen Buddhism Established in Japan

In the 12th century CE, a Japanese monk named Eisai returned from China, bringing with him both green tea and the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. In the form of meditation practiced by this school, the student’s only guidance is to come from the subtle hint of a raised eyebrow, the sudden jolt of an unexpected slap, or the teacher’s direct questioning on the meaning of a koan.

1203 CE Destruction of Buddhist Centers in India

By the close of the first millennium CE, Buddhism had passed its zenith in India. Traditionally, the end of Indian Buddhism is identified with the advent of Muslim Rule in Northern India. The Turk Muhammad Ghuri razed the last two great Buddhist universities, Nalanda and Vikramasila, in 1197 and 1203 respectively. However, recent histories have suggested that the destruction of these monasteries was militarily, rather than religiously, motivated.

1200s CE True Pure Land Buddhism Established

Honen’s disciple Shinran Shonin (1173-1262 CE) began the devotional “True Pure Land” movement in the 13th century CE. Considering the lay/monk distinction invalid, Shinran married and had several children, thereby initiating the practice of married Jodo Shinshu clergy and establishing a familial lineage of leadership — traits which continue to distinguish the school to this day.

1200s CE Dōgen Founds Soto Zen in Japan

Dōgen (1200-1253 CE), an influential Japanese priest and philosopher, spent most of his two years in China studying T’ien-t’ai Buddhism. Disappointed by the intellectualism of the school, he was about to return to Japan when the Ts’ao-tung monk Ju-ching (Rujing) explained that the practice of Zen simply meant “dropping off both body and mind.” Dōgen, immediately enlightened, returned to Japan, establishing Soto (the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese graphs for Ts’ao-tung) as one of the pre-eminent schools.

1253 CE Nichiren Buddhism Established in Japan

As the sun began to rise on May 17, 1253 CE, Nichiren Daishonin climbed to the crest of a hill, where he cried out “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo,” “Adoration to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Perfect Truth.” Nichiren considered the recitation of this mantra to be the core of the true teachings of the Buddha. He believed that it would eventually spread throughout the world, a conviction sustained by contemporary sects of the Nichiren school, especially the Soka Gakkai.

1279-1360 CE Theravada Buddhism Established in Southeast Asia

With Kublai Khan’s conquest of China in the thirteenth century CE, ever greater numbers of Tai migrated from southwestern China into present day Thailand and Burma. There, they established political domination over the indigenous Mon and Khmer peoples, while appropriating elements of these cultures, including their Buddhist faith. By the time that King Rama Khamhaeng had ascended the throne in Sukhothai (central Thailand) in 1279, a monk had been sent to Sri Lanka to receive Theravadin texts. During the reigns of Rama Khamhaeng’s son and grandson, Sinhala Buddhism spread northward to the Tai Kingdom of Chiangmai. Within a century, the royal houses of Cambodia and Laos also became Theravadin.

1391-1474 CE The First Dalai Lama

Gedun Drupa (1391-1474 CE), a Tibetan monk of great esteem during his lifetime, was considered after his death to have been the first Dalai Lama. He founded the major monastery of Tashi Lhunpo at Shigatse, which would become the traditional seat of Panchen Lamas (second only to the Dalai Lama).

1881 CE Founding of Pali Text Society

Ever since its founding by the British scholar T.W. Rhys Davids in 1881 CE, the Pali Text Society has been the primary publisher of Theravada texts and translations into Western languages.

1891 CE Anagarika Dharmapala Founds Mahabodhi Society

Sri Lankan writer Anagarika Dharmapala played an important role in restoring Bodh-Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment, which had badly deteriorated after centuries of neglect. In order to raise funds for this project, Dharmapala founded the Mahabodhi Society, first in Ceylon and later in India, the United States, and Britain. He also edited the society’s periodical, The Mahabodhi Journal.

1930 CE Soka Gakkai Established in Japan

Soka Gakkai is a Japanese Buddhist movement that was begun in 1930 CE by an educator named Tsunesaburo Makiguchi. Soon after its founding, it became associated with Nichiren Shoshu, a sect of Nichiren Buddhism. Today the organization has over twelve million members around the world.

1938 CE Rissho Kosei-Kai Established in Japan

The Rissho Kosei-Kai movement was founded by the Rev. Nikkyo Niwano in 1938 CE, and is based on the teachings set forth in the Lotus Sutra and works for individual and world peace. Rev. Niwano was awarded the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion in 1979 and honored by the Vatican in 1992. The Rissho Kosei-Kai has since been active in interfaith activities throughout the world.

1949 CE Buddhist Sangha Flees Mainland China

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Buddhist monks and nuns fled to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore. Many of these monks and nuns subsequently immigrated to Australia, Europe and the United States.

1950 CE World Fellowship of Buddhists Inaugurated in Sri Lanka

The World Fellowship of Buddhists was established in 1950 CE in Sri Lanka to bring Buddhists together in promoting common goals. Since 1969, its permanent headquarters have been in Thailand, with regional offices in 34 different countries.

1956 CE Buddhist Conversions in India

On October 14, 1956 CE, Bhim Rao Ambedkar (1891-1956), India’s leader of Hindu untouchables, publicly converted to Buddhism as part of a political protest. As many as half a million of his followers also took the three refuges and five precepts on that day. In the following years, over four million Indians, chiefly from the castes of untouchables, declared themselves Buddhists.

1959 CE Dalai Lama Flees to India

With the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, the Karmapa, and other Vajrayana Buddhist leaders fled to India. A Tibetan government in exile was established in Dharamsala, India.

1966 CE Thich Nhat Hanh Visits the U.S. and Western Europe

Thich Nhat Hanh is a Vietnamese monk, teacher, and peace activist. While touring the U.S. in 1966, Nhat Hanh was outspoken against the American-supported Saigon government. As a result of his criticism, Nhat Hanh faced certain imprisonment upon his return to Vietnam. He therefore decided to take asylum in France, where he founded Plum Village, today an important center for meditation and action.

1975 CE Devastation of Buddhism in Cambodia

Pol Pot’s Marxist regime came to power in Cambodia in 1975 CE. Over the four years of his governance, most of Cambodia’s 3,600 Buddhist temples were destroyed. The Sangha was left with an estimated 3,000 of its 50,000 monks. The rest did not survive the persecution.

1989 CE Founding of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) began in Thailand in 1989 as a conference of 36 monks and lay persons from 11 countries. Today, it has expanded to 160 members and affiliates from 26 countries. As its name suggests, INEB endeavors to facilitate Buddhist participation in social action in order to create a just and peaceful world.

1989 CE Dalai Lama Receives Nobel Peace Prize

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 for his tireless work spreading a message of non-violence. He has said on many occasions about Buddhism, “My religion is very simple – my religion is kindness.”

2010 CE Western Buddhist Teachers call for U.S. Commission of Inquiry to Burma

In 2010, prominent Buddhist teachers in the U.S. signed a letter to President Barack Obama urging him to repudiate the results of the upcoming Burmese election, in light of crimes against ethnic groups committed by the Burmese military regime.

With over 520 million followers, Buddhism is currently the world’s fourth-largest religious tradition. Though Theravada and Mahayana are its two major branches, contemporary Buddhism comprises a wide diversity of practices, beliefs, and traditions — both throughout East and Southeast Asia and worldwide.

Buddhism in America (text)

1853 ce the first chinese temple in “gold mountain”.

Attracted by the 1850s Gold Rush, many Chinese workers and miners came to California, which they called “Gold Mountain” — and brought their Buddhist and Taoist traditions with them. In 1853, they built the first Buddhist temple in San Francisco’s Chinatown. By 1875, Chinatown was home to eight temples, and by the end of the century, there were hundreds of Chinese temples and shrines along the West Coast.

1878 CE Kuan-yin in Hawaii

In 1878, the monk Leong Dick Ying brought to Honolulu gold-leaf images of the Taoist sage Kuan Kung and the bodhisattva of compassion Kuan-yin. He thus established the Kuan-yin Temple, which is the oldest Chinese organization in Hawaii. The Temple has been located on Vineland Avenue in Honolulu since 1921.

1879 CE The Light of Asia Comes West

Sir Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia, a biography of the Buddha in verse, was published in 1879. This immensely popular book, which went through eighty editions and sold over half a million copies, gave many Americans their first introduction to the Buddha.

1882 CE The Chinese Exclusion Act

Two decades of growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the U.S. led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act barred new Chinese immigration for ten years, including that by women trying to join their husbands who were already in the U.S., and prohibited the naturalization of Chinese people.

1893 CE Buddhists at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

The 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, held in Chicago in conjunction with the World Columbian Exposition, included representatives of many strands of the Buddhist tradition: Anagarika Dharmapala (Sri Lankan Maha Bodhi Society), Shaku Soyen (Japanese Rinzai Zen), Toki Horyu (Shingon), Ashitsu Jitsunen (Tendai), Yatsubuchi Banryu (Jodo Shin), and Hirai Kinzo (a Japanese lay Buddhist). Days after the Parliament, in a ceremony conducted by Anagarika Dharmapala, Charles T. Strauss of New York City became the first person to be ordained into the Buddhist Sangha on American soil.

1894 CE The Gospel of Buddha

The Gospel of Buddha was an influential book published by Paul Carus in 1894. The book brought a selection of Buddhist texts together in readable fashion for a popular audience. By 1910, The Gospel of Buddha had been through 13 editions.

1899 CE Jodo Shinshu Buddhism and the Buddhist Churches of America

The Young Men’s Buddhist Association (Bukkyo Seinenkai), the first Japanese Buddhist organization on the U.S. mainland, was founded in 1899 under the guidance of Jodo Shinshu missionaries Rev. Dr. Shuya Sonoda and Rev. Kakuryo Nishijima. The following years saw temples established in Sacramento (1899), Fresno (1900), Seattle (1901), Oakland (1901), San Jose (1902), Portland (1903), and Stockton (1906). This organization, initially called the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America, went on to become the Buddhist Churches of America (incorporated in 1944). Today, it is the largest Buddhist organization serving Japanese-Americans, entailing some 60 temples and a membership of about 19,000.

1900 CE First Non-Asian Buddhist Association

In 1900, a group of Euro-Americans attracted to the Buddhist teachings of the Jodo Shinshu organized the Dharma Sangha of the Buddha in San Francisco.

1915 CE World Buddhist Conference

Buddhists from throughout the world gathered in San Francisco in August 1915 at a meeting convened by the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America. Resolutions from the conference were taken to President Woodrow Wilson.

1931 CE Sokei-an and Zen in New York

The Buddhist Society of America was incorporated in New York in 1931 under the guidance of Rinzai Zen teacher Sokei-an. Sokei-an first came to the U.S. in 1906 to study with Shokatsu Shaku in California, though he completed his training in Japan where he was ordained in 1931. Sokei-an died of poor health in 1945, after having spent two years in a Japanese internment camp. The center he established in New York City would evolve into the First Zen Institute of America.

1935 CE Relics of the Buddha to San Francisco

In 1935, a portion of the Buddha’s relics was presented to Bishop Masuyama of the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Mission of North America, based in San Francisco. This led to the construction of a new Buddhist Church of San Francisco, with a stupa on its roof for the holy relics, located on Pine Street and completed in 1938.

1942 CE Internment of Japanese Americans

Two months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which eventually removed 120,000 Japanese Americans, both citizens and noncitizens, to internment camps where they remained until the end of World War II. Buddhist priests and other community leaders were among the first to be targeted and evacuated. Zen teachers Sokei-an and Nyogen Senzaki were both interned. Buddhist organizations continued to serve the internees in the camps.

1949 CE Buddhist Studies Center in Berkeley

The Buddhist Studies Center was first established in 1949 in Berkeley, California, under the auspices of the Buddhist Churches of America. In 1966, the center changed its name to the Institute of Buddhist Studies and became the first seminary for Buddhist ministry and research. The Institute affiliated with the Graduate Theological Union in 1985, and today is active in training clergy for the Buddhist Churches of America.

1955 CE Beat Zen and Zen Literature

The Beat Movement was started by American authors who explored American pop culture and politics in the post-war era, with strong themes from Eastern spirituality. The first public reading of the poem “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg in 1955 at the Six Gallery in San Francisco is said to have signalled the beginning of the Beat Zen movement. The late 1950s also saw a Zen literary boom in the U.S. Several popular books on Buddhism were published, including Alan Watt’s bestseller The Way of Zen and Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums.

1960 CE Soka Gakkai in the U.S.

Daisaku Ikeda, President of Soka Gakkai, visited the United States in 1960, largely introducing Soka Gakkai to Americans. By 1992, Soka Gakkai International–USA estimated that it had 150,000 American members.

1965 CE Immigration and Nationality Act

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act ended the quota system which had virtually halted immigration from Asia to the United States for over forty years. Following 1965, growing numbers of Asian immigrants from South, Southeast, and East Asia settled in America; many brought Buddhist traditions with them.

1966 CE The Vietnam Conflict and Thich Nhat Hanh in America

The Vietnam conflict incited a surge of Buddhist activism in Saigon, which included some monks immolating themselves as an act of protest. In response, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Cabot Lodge met with Vietnamese and Japanese Buddhist leaders, and the State Department established an Office of Buddhist Affairs headed by Claremont College Professor Richard Gard. In 1966, Vietnamese monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh came to the United States to speak about the conflict. His visit, coupled with the English publication of his book, Lotus in a Sea of Fire, so impressed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize.

1966 CE First Buddhist Monastery in Washington D.C.

The Washington Buddhist Vihara was the first Sri Lankan Buddhist temple in America. It was established in Washington, D.C. in 1966 as a missionary center with the support of the Sri Lankan government. The Ven. Bope Vinita Thera brought an image and a relic of the Buddha to the nation’s capital in 1965. The following year, the Vihara was incorporated, and in 1968, it moved to its present location on 16th Street, NW.

1969 CE Tibetan Center in Berkeley

Tarthang Tulku, a Tibetan monk educated at Banaras Hindu University in India, came to Berkeley and in 1969 established the Nyingma Meditation Center, the first Tibetan Buddhist center in the U.S.

1970 CE Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche to America

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche was an Oxford-educated Tibetan teacher who brought the Karma Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist lineage to the U.S. in 1970. In 1971, he established Karma Dzong in Boulder, Colorado, and in 1973, he founded Vajradhatu, an organization consolidating many Dharmadhatu centers. Cutting through Spiritual Materialism, his classic introduction to Trungpa’s form of Tibetan Buddhism, was published in 1973.

1970 CE International Buddhist Meditation Center

The International Buddhist Meditation Center was established by Ven. Dr. Thich Thien-An, a Vietnamese Zen Master, in Los Angeles in 1970. The College of Buddhist Studies is also located on the grounds of the Center, which is currently under the direction of Thien-An’s student, Ven. Karuna Dharma.

1972 CE Korean Zen Master comes to Rhode Island

Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn came to the United States in 1972 with little money and little knowledge of English. He rented an apartment in Providence and worked as a washing machine repairman. A note on his door said simply, “What am I?” and announced meditation classes. Thus began the Providence Zen Center, followed soon by Korean Zen Centers in Cambridge, New Haven, New York, and Berkeley, all part of the Kwan Um School of Zen.

1974 CE Buddhist Chaplain in California

In 1974, the California State Senate appointed Rev. Shoko Masunaga as its first Buddhist and first Asian-American chaplain.

1974 CE First Buddhist Liberal Arts College

Naropa Institute was founded in Boulder, Colorado in 1974 as a Buddhist-inspired but non-sectarian liberal arts college. It aimed to combine contemplative studies with traditional Western scholastic and artistic disciplines. The accredited college now offers courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels in Buddhist studies, contemplative psychotherapy, environmental studies, poetics, and dance.

1974 CE Redress for Internment of Japanese Americans

In 1974, Rep. Phillip Burton of California addressed the U.S. House of Representatives on the topic “Seventy-five Years of American Buddhism” as part of an ongoing debate surrounding redress for Japanese Americans interned during World War II.

1975 CE The Fall of Saigon and the Arrival of Refugees

About 130,000 Vietnamese refugees, many of them Buddhists, came to the U.S. in 1975 after the fall of Saigon. By 1985 there were 643,200 Vietnamese in the U.S. Dr. Thich Thien-an, a Vietnamese monk and scholar already in Los Angeles, began the first Vietnamese Buddhist temple in America – the Chua Vietnam – in 1976. The temple is still thriving on Berendo Street, not far from central Los Angeles. With the end of the war, some 70,000 Laotian, 60,000 Hmong, and 10,000 Mien people also arrived in the U.S. as refugees bringing their religious traditions, including Buddhism, with them.

1976 CE Council of Thai Bhikkhus

The Council of Thai Bhikkhus, a nonprofit corporation founded in 1976 and based in Denver, Colorado, became the leading nationwide network for Thai Buddhism.

1976 CE City of 10,000 Buddhas

The City of 10,000 Buddhas was established in 1976 in Talmage, California by the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association as the first Chinese Buddhist monastery for both monks and nuns. The City of 10,000 Buddhas consists of sixty buildings, including elementary and secondary schools and a university, on a 237-acre site.

1976 CE First Rinzai Zen Monastery

On July 4 1976, Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji, America’s first Rinzai Zen monastery, was established in Lew Beach, New York, under the direction of Eido Tai Shimano-roshi.

1979-1989 CE Cambodian Refugees Come to the U.S.

The regime of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge ended in 1979 with the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. Over the following ten years, 180,000 Cambodian refugees were relocated from Thailand to the United States. In 1979, the Cambodian Buddhist Society was established in Silver Spring, Maryland, as the first Cambodian Buddhist temple in America. Later in 1987, the nearly 40,000 Cambodian residents of Long Beach, California, purchased the former headquarters of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union and converted the huge building into a temple complex.

1980 CE First Burmese Temple

Dhammodaya Monastery, the first Burmese Buddhist temple in America, was established in Los Angeles in 1980.

1980 CE Buddhist Sangha Council

The Buddhist Sangha Council of Los Angeles (later of Southern California) was established under the leadership of the Ven. Havanpola Ratanasara in 1980. It was one of the first cross-cultural, inter-Buddhist organizations, bringing together monks and other leaders from a wide range of Buddhist traditions.

1986 CE Buddhist Astronaut on Challenger

Lt. Col. Ellison Onizuka, a Hawaiian-born Jodo Shinshu Buddhist, was killed 73 seconds after takeoff in the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. He was the first Asian-American to reach space.

1987 CE American Buddhists Get Organized

For ten days in July of 1987, Buddhists from all the Buddhist lineages in North America came together in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for a Conference on World Buddhism in North America — intended to promote dialogue, mutual understanding, and cooperation. In the same year, the Buddhist Council of the Midwest gathered twelve Chicago-area lineages of Buddhism; in Los Angeles, the American Buddhist Congress was created, with 47 Buddhist organizations attending its inaugural convention. Also in 1987, the Sri Lanka Sangha Council of North America was established in Los Angeles to serve as the national network for Sri Lankan Buddhism.

1987 CE Buddhist Books Gain Wider Audience

In 1987, Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield published what became a classic book on vipassana meditation – Seeking the Heart of Wisdom: The Path of Insight Meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh, who was residing at Plum Village in France and visiting the United States annually, also published Being Peace, a classic treatment of “engaged Buddhism” – Buddhism that is concerned with social and ecological issues.

1990s CE Popular Buddhism

Throughout the 1990s, immigrant and American-born Buddhist communities were growing and building across the United States. In the midst of this flourishing, there emerged a popular “Hollywood Buddhism” or a Buddhism of celebrities which persists today. Espoused by figures from Tina Turner to the Beastie Boys to bell hooks, Buddhism became a larger part of mass culture during the 90s.

1991 CE Tricycle: the Buddhist Review

The first issue of Tricycle: the Buddhist Review, a non-sectarian national Buddhist magazine, was published in 1991. The journal features articles by prominent Buddhist teachers and writers as well as pieces on Buddhism and American culture at large.

1991 CE Tibetan Resettlement in the United States

The National Office of the Tibetan Resettlement Project was established in New York in 1991 after the U.S. Congress granted 1,000 special visas for Tibetans, all of them Buddhists. Two years later, the Tibetan Community Assistance Program opened to assist Tibetans resettling in New York. Cluster groups of Tibetan refugees have since established their own small temples and have begun to encounter Euro-American practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism.

1991 CE Dalai Lama in Madison Square Garden

For more than a week in October in 1991, the Dalai Lama gave the “Path of Compassion” teachings and conferred the Kalachakra Initiation in Madison Square Garden in New York City.

1993 CE Centennial of the World’s Parliament of Religions

There were many prominent Buddhist speakers at the 1993 Centennial of the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, among them Thich Nhat Hanh, Master Seung Sahn, the Ven. Mahaghosananda, and the Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara. The Dalai Lama gave the closing address. There were myriad Buddhist co-sponsors of the event, including the American Buddhist Congress, Buddhist Churches of America, Buddhist Council of the Midwest, World Fellowship of Buddhists, and Wat Thai of Washington, D.C.

2006 CE American Monk Named First U.S. Representative to World Buddhist Supreme Conference

In 2006, Venerable Bhante Vimalaramsi (Sayadaw Gyi U Vimalaramsi Maha Thera) was nominated and confirmed as the first representative from the United States for the World Buddhist Supreme Conference, which is held every two years and includes representatives from fifty countries.

2007 CE First Buddhist Congresswoman Sworn In

Rep. Mazie Hirono, a Democrat from Hawaii, in 2007 became the first Buddhist to be sworn into the United States Congress.

Today, Buddhism thrives in America, with American Buddhists comprising myriad backgrounds, identities, and religious traditions and often integrating Buddhism with other forms of spiritual practice. It is estimated that there are roughly 3.5 million Buddhist practitioners in the United States at present. Many live in Hawaii or Southern California, but there are surely followers of Buddhism around the nation.

Selected Publications & Links

Takaki, Ronald . A Different Mirror . Boston: Little, Brown & Co. 1993.

Sidor, Ellen S . A Gathering of Spirit: Women Teaching in American Buddhism . Cumberland: Primary Point Press, 1987.

Tweed, Thomas A., and Stephen Prothero (eds.) . Asian Religions in America: A Documentary History . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Access to Insight

America burma buddhist association, american buddhist congress, buddha’s light international association, buddhist churches of america, explore buddhism in greater boston.

Buddhism arrived in Boston in the 19th century with the first Chinese immigrants to the city and a growing intellectual interest in Buddhist arts and practice. Boston’s first Buddhist center was the Cambridge Buddhist Association (1957). The post-1965 immigration brought new immigrants into the city—from Cambodia and Vietnam, as well as Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Korea. These groups brought with them a variety of Buddhist traditions, now practiced at over 90 area Buddhist centers and temples. Representing nearly every ethnicity, age, and social strata, the Buddhist community of Greater Boston is a vibrant presence in the city.

- Bio: Overview

- Encountering a Mentor

- Attending "Toda University"

- Learning Leadership

- Political Involvement and Persecution

- Assuming the Presidency

- Trip to the USA

- The 1960s—Bold Beginnings

- Founding the Komei Party

- Further New Ventures

- The 1970s—Dialogue, Breaking New Ground

- Resignation

- The 1980s—Peace through Dialogue

- Excommunication

- Developing Educational Exchange

- A Question of Motivation

- Photo Album

- Curriculum Vitae

- Profile Downloads

- Encountering Josei Toda

- A Mother's Love

- A Conversation with My Wife

- Buddhism in Action: Overview

- Buddhism and the Lotus Sutra

- A Universal Humanity

- Buddhist Humanism

- Human Revolution

- The Role of Religion

- The Living Buddha

- The Flower of Chinese Buddhism

- The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra

- What Is Human Revolution?

- Death Gives Greater Meaning to Life

- The Buddhist View of Life and Death

- Institute of Oriental Philosophy

- Advancing Peace: Overview

- Opposition to War

- Developing a Culture of Peace

- Dialogue as the Path to Peace

- A Portrait of Citizen Diplomacy

- Sino-Japanese Relations

- Cultural Exchanges for Peace: Cuba

- Facing Up to Asia

- Peace Through Culture

- A Grassroots Movement

- Peace Proposals

- Strongholds for Peace

- The Courage of Nonviolence

- Religion Exists to Realize Peace

- Stop the Killing

- Memories of My Eldest Brother

- Aleksey N. Kosygin

- Chingiz Aitmatov

- Jose Abueva

- Maria Teresa Escoda Roxas

- Mikhail Gorbachev

- Nelson Mandela

- Wangari Maathai

- Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue

- Toda Peace Institute

- Creative Education: Overview

- Why Education?

- What is Value-Creating Education?

- Soka Education in Practice

- Wisdom and Knowledge

- Ikeda's Own Educational Influences

- An Educational Legacy

- A Global Network of Humanistic Education

- Educational Proposal

- Global Citizens and the Imperative of Peace

- For a Sustainable Global Society: Learning for Empowerment and Leadership (2012)

- Education for Sustainable Development Proposal (2002)

- Reviving Education: The Brilliance of the Inner Spirit (2001)

- Building a Society That Serves the Essential Needs of Education (2000)

- The Dawn of a Century of Humanistic Education

- The Tradition of Soka University

- Teachers of My Childhood

- Makiguchi's Philosophy of Education

- Treasuring Every Child

- Be Creative Individuals

- Makiguchi Foundation for Education

- Soka Schools

- Soka University, Japan

- Soka University of America

- Cultivating the Human Spirit: Overview

- A Revitalizing Power

- Infusing Culture into the Soka Gakkai

- Cultural Institutes and Cultural Exchange

- A Culture of Dialogue

- Restoring Our Connections with the World

- The Flowering of Creative Life Force

- Fang Zhaoling

- Brian Wildsmith

- On Writing Children's Stories

- Min-On Concert Association

- Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

- Full List of Published Dialogues

- Book Catalog

- History of Buddhism (3)

- Buddhist Philosophy (3)

- Diaries / Novels (3)

- Dialogues (39)

- Addresses (3)

- Education (1)

- Youth / Children (7)

- Recent Events

- 2024 Events

- 2023 Events

- 2022 Events

- 2021 Events

- 2020 Events

- 2019 Events

- 2018 Events

- 2017 Events

- 2016 Events

- 2015 Events

- 2014 Events

- 2013 Events

- 2012 Events

- 2011 Events

- 2010 Events

- 2009 Events

- 2008 Events

- Dialogue with Nature

- Featured Photos

- Quotations—Overview

- Quotations by Theme

- Academic Honors Conferred

- Conferral Citations

- Literary Awards

- Lectures Delivered

- Institutes Founded

- Statements | Messages | Lectures

- Recollections

- Portraits of Global Citizens

- Opinion Editorials

- IDN , Apr. 19, 2019

- IDN-IPS, Jun. 21, 2010

- IDN-IPS, Sep. 29, 2009

- Tricycle, Winter 2008

- IPS, Aug.1, 2008

- IPS, Mar. 28, 2008

- Emzin, Nov. 2003

- Seikyo Shimbun, Dec. 25, 2001

- Sankei Shimbun, Sep. 17, 2001

- Tribute to Daisaku Ikeda

- The Potter's Hand

- Religion in Action

- Dr. Denis Brière

- Dr. Harvey Cox

- Reader's Response

- Dr. Jin Yong

- Kenneth M. Price

- Dr. Larry A. Hickman

- Dr. M. S. Swaminathan

- Dr. Lou Marinoff

- Dr. Mary Catherine Bateson

- Dr. Mikhail E. Sokolov

- Dr. N. Radhakrishnan

- Dr. Nadezda Shaydenko

- Dr. Nur Yalman

- Dr. Sarah Wider

- Climate Action

- Education for All

- Nuclear Weapons Abolition

- Make It You: Make It Now!

- Daisaku Ikeda: A Tribute

- Archive (2008-2018)

Daisaku Ikeda social media accounts:

Share this page on

- Buddhist Philosopher

- Peacebuilder

- Proponent of Culture

- Terms of Use

- Cookies Policy

Created by the Daisaku Ikeda Website Committee

© Soka Gakkai. All Rights Reserved.

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford scholar discusses Buddhism and its origins

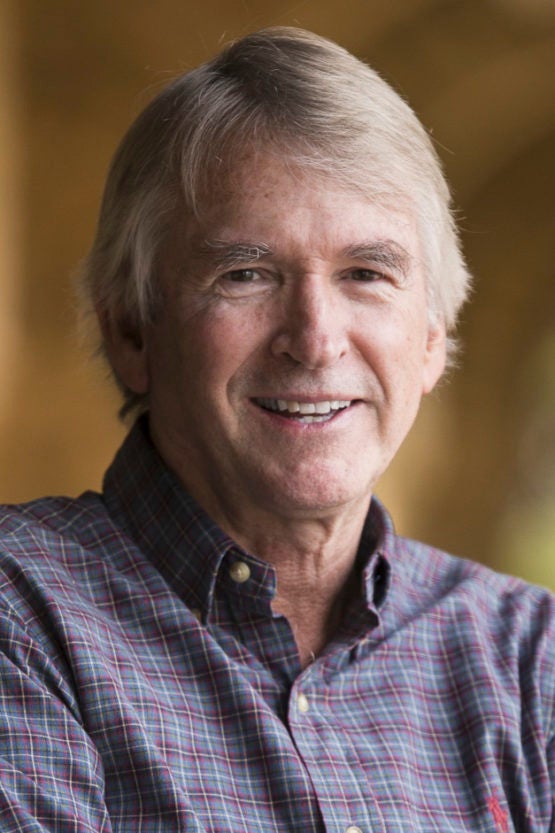

Stanford religious studies Professor Paul Harrison talks about the latest research on the origin of Buddhism and the rise of Mahayana Buddhism, which has influenced most of today’s Buddhist practices around the world.

It’s hard to find a self-help book today that doesn’t praise the benefits of meditation, mindfulness and yoga.

Many individuals engage in meditation and other practices associated with Buddhism. But not all realize the complexities of the religion, according to Stanford expert Paul Harrison. (Image credit: FatCamera / Getty Images)

Many of these practices are rooted in the ancient tradition of Buddhism, a religion first developed by people in India sometime in the fifth century BCE.

But according to Stanford Buddhist scholar Paul Harrison , Buddhism is more than finding zen: It is a religious tradition with a complicated history that has expanded and evolved over centuries. Harrison has dedicated his career to studying the history of this religion, which is now practiced by over 530 million people.

In a recent book he edited, Setting Out on the Great Way: Essays on Early Mahāyāna Buddhism , Harrison brings together the latest perspectives on the origins and early history of a type of Buddhism that has influenced most of today’s Buddhist practices around the world.

This new work focuses on the rise of Mahayana Buddhism, which evolved about 400 years after the birth of Buddhism. It is an elaborate web of ideas that has seen other types of Buddhism branch from its traditions. Unlike other Buddhists, Mahayana followers aspire to not only liberate themselves from suffering but also lead other people toward liberation and enlightenment.

Stanford News Service interviewed Harrison, the George Edwin Burnell Professor of Religious Studies in the School of Humanities and Sciences, about Buddhism and the latest research on its origins.

What are some things that people may not know about Buddhism?

Some people, especially those in the Western world, seem to be bewitched and mesmerized by the spell of Buddhism and the way it’s represented in the media. We’re now saturated with the promotion of mindfulness meditation, which comes from Buddhism.

Paul Harrison (Image credit: Connor Crutcher)

But Buddhism is not all about meditation. Buddhism is an amazingly complex religious tradition. Buddhist monks don’t just sit there and meditate all day. A lot of them don’t do any meditation at all. They’re studying texts, doing administrative work, raising funds and performing rituals for the lay people, with a particular emphasis on funerals.

Buddhism has extremely good press. I try to show my students that Buddhism is not so nice and fluffy as they might think. Buddhism has a dark side, which, for example, we’ve been seeing in Myanmar with the recent persecution of the Rohingya people there.

It’s as if we need to believe that there is a religion out there that’s not as dark and black as everything else around us. But every religion is a human instrument, and it can be used for good and for bad. And that’s just as true of Buddhism as of any other faith.

Why is it important to study the origin of Buddhism and other religions?

Religion plays a hugely important role in our world today. Sometimes it has extremely negative consequences, as evidenced by terrorism incidents such as the Sept. 11 attacks. But sometimes it has positive consequences, when it’s used to promote selfless behavior and compassion.

Religion is important to our politics. So, we need to understand how religions work. And part of that understanding involves trying to grasp how religions developed and became what they became.

This new book of essays on Mahayana Buddhism is just a small part of figuring out how Buddhism developed over time.

What is Mahayana Buddhism and what are its distinct features?

The word Mahayana is usually translated as “the great vehicle.” The word maha means “great,” but the yana bit is trickier. It can mean both “vehicle” and “way,” hence the title of this book.

As far as we know, Mahayana Buddhism began to take shape in the first century BCE. This religious movement then rapidly developed in a number of different places in and around what is now India, the birthplace of Buddhism.

Buddhism itself started sometime in the fifth century BCE. We now think that the Buddha, who founded the religion, died sometime toward the year 400 BCE. As Buddhism developed, it spread beyond India. A number of different schools emerged. And out of that already complicated situation, we had the rise of a number of currents, or ways of thinking, which eventually started being labeled as Mahayana.

The kind of Buddhism before Mahayana, which I call mainstream Buddhism, is more or less a direct continuation of the teachings of the founder. Its primary ideal is attaining liberation from suffering and the cycle of life and rebirth by achieving a state called nirvana. You can achieve nirvana through moral striving, the use of various meditation techniques and learning the Dharma, which is the Buddha’s teachings.

Eventually, some people said that mainstream Buddhism is all fine and well but that it doesn’t go far enough. They believed that people need to not just liberate themselves from suffering but also liberate others and become Buddhas too.

Mahayana Buddhists strive to copy the life of the Buddha and to replicate it infinitely. That effort was the origin of the bodhisattva ideal. A bodhisattva is a person who wants to become a Buddha by setting out on the great way. This meant that Mahayana Buddhists were allegedly motivated by greater compassion than the normal kind of Buddhists and aimed for a complete understanding of reality and greater wisdom.

That’s Mahayana in a nutshell. But along with that goes a whole lot of new techniques of meditation, an elaborate cosmology and mythology, and a huge number of texts that were written around the time of the birth of Mahayana.

What’s the biggest takeaway from the latest research on the origin of Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism?

The development of Buddhism and its literature is much more complicated than we have realized. In the middle of the 20th century, scholars thought Mahayana Buddhism was developed by lay people who wanted to make a Buddhism for everybody. It was compared to the Protestant movement in Christianity. But we now know that this picture is not true.

The evidence shows that Mahayana Buddhism was spearheaded by the renunciants, the Buddhist monks and nuns. These were the hardcore practitioners of the religion, and they were responsible for writing the Mahayana scriptures and promoting these new ideas. The lay people were not the initiators.

But the full story is even more complicated than that. Buddhism’s development is more like a tumbleweed than a tree. And Mahayana Buddhism is sort of like a braided stream of several river currents, without one main current.

Why is it challenging to figure out how Mahayana Buddhism came about?

What’s special about Buddhist studies and makes it different from studying religions like Christianity is that there is still a huge amount of material that has not been translated or studied properly.

In the last two or three decades, scholars have also discovered a whole lot of texts in a long-lost language, called Gandhari, some of which are related to the Mahayana. These documents, the oldest of which date to the first century BCE, have been found in a region that now includes Pakistan and parts of North India, Afghanistan and Central Asia.

A lot of these texts are very hard to translate and understand. And there is more material that keeps surfacing. All of that is changing our view of the early history of Buddhism.

Pain, suffering, and the time of life: a buddhist philosophical analysis

- Published: 08 February 2024

Cite this article

- Sean M. Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8091-689X 1

101 Accesses

Explore all metrics

In this paper, I explore how our experience of pain and suffering structure our experience over time. I argue that pain and suffering are not as easily dissociable, in living and in conceptual analysis, as philosophers have tended to think. Specifically, I do not think that there is only a contingent connection between physical pain and psychological suffering. Rather, physical pain is partially constitutive of existential suffering. My analysis is informed by contemporary thinking about pain and suffering as well as Indian Buddhist philosophy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Phenomenological psychology and qualitative research

The impoverishment problem

Self-identity and personal identity.

A note on the differences between ‘homeostatic’ and ‘homeodynamic’ is in order. They refer to the same process. 'Homeo stasis ' puts emphasis on the fact that an organism survives by aiming for a kind of steady-state that allows it to persist in the face of an unstable world. The organism withstands the onslaught of environmental perturbances by maintaining a balance. This balance is what the ‘stasis’ in ‘homeostasis’ refers to. This process of self-regulation is also 'homeo dynamic ' because perturbations born of self-world contact are constant. Perfect balance is asymptotic. Persistence is achieved when those fluctuations occur within a permissible range of excitation; organismic stability is really meta-stability. The organism is not aiming at a steady state but at preservation of dynamic flexibility that keeps it robust across a variety of self-world interactions. Therefore, I use the term 'homeodynamic' to refer to this most basic level of bodily affect. It is a more accurate description of the regulatory micro-dynamics of the organism.

It is important to distinguish between commitment to the view that pain has a type-identity of being a homeodynamic affect (which I defend) and that tokens of this type have content which is formatted imperatively rather than descriptively. I am friendly to the view that pain content is formatted in this way, but this is consistent with pain’s having a complex formatting which admits of other dimensions to it’s content. Klein ( 2015 ) defends pure imperativism. I have no such commitments. See Corns ( 2014 ) for an astute and critical analysis of the possibility of any unified account of pain. She notes that, "Philosophical accounts of pain traditionally focus on three mental state types: emotions, perceptions, and sensations" (2014, 356), thus, leaving out a consideration of pains as having imperative content. I think this omission is a mistake. But I agree with her that, "…paradigmatic pain experiences also have thoughts and motivational responses as components. A paradigmatic pain feels like something, is about something, includes a perception of something, and makes us want to do something" (Corns 2014 , 356).

Here I want to acknowledge a potential objection from Leder’s excellent work The Absent Body ( 1990 ). Leder might object that the disappearance of the body from awareness is precisely a structural attribute of our phenomenological horizon. That is the surface of the body disappears from awareness in the ekstasis of embodied perception through the latter’s engagement with its world, and it disappears in terms of visceral depth because of the irrelevance of bodily depth of the ordinary practice of everyday activity. Leder refers to these modes of bodily disappearance as ‘corporeal primitives’ (1990, 19). However, in a footnote he also acknowledges that there is “a certain body-awareness that ceaselessly accompanies activity” (ibid, 177–8 fn. 27). Thus, I think we should read ‘disappearance’ not as an absence from consciousness but as a receding into the tacitly experienced phenomenological background.

This is because the body is vulnerable. Here I agree with Russon that: “to the extent that the meaningfulness of our world depend on the determinateness of our (mortal) bodies, that meaningfulness is inherently vulnerable . More precisely, ‘to be meaningful’ and ‘to be vulnerable’ cannot be separated, with the result that suffering is inherent to the developed forms of our meaningful human lives” (206, 184). I will have occasion to return to these themes, and to Russon’s treatment of them, below.

Phenomenological philosophers concerned with pain have glossed this phenomenon as obviously sensory in nature (e.g. Geniusas 2020 , 44) and justify this through adverting to a Husserlian approach to phenomenological description that, “is possible only if it places in brackets the accomplishments we come across in the science of pain” (Geniusas 2020 , 14). By understanding pain’s biological role through its type-identification as a homeodynamic (rather than sensory) affect, we come to understand its phenomenal character as a component of the existential predicament of an embodied milieu. This kind of disagreement about methodology will also bear on my positive characterization of pain’s intentionality, for which see below (§3).

This extended network of nerve fibers that innervate the entire body sends afferent signals of many sorts to the brain, pain being only one.

I will interpret Buddhist philosophers as arguing that the very process of homdeodynamic self-regulation is itself a subtle and pervasive form of suffering. If that is so, then it looks like local pains are themselves specific and obvious instances of a more general existential predicament, one that situates the embodied subject in a world of suffering. See §4.

Obviously, there is more that could be said here. I am unable to go into more detail on account of space. For a nice overview of these and other related issues, see the chapters and responses in Aydede ( 2005 ).

When Buddhist philosophers of different stripes reject the existence of a soul or self ( ātman ), they do so by explaining that anything the self might do in terms of the activities of the aggregates (Smith 2021 ).

Here my analysis should be contrasted with Russon’s who claims of the deepest level of dukkha that it indicates the presence of more “active attitudes rooted in our beliefs and desires” ( 2016 , 184). As should be clear from my reconstruction of the three levels, on the basis of the commentarial literature, this more active way of understanding the third level of dukkha is to over-intellectualize its nature.

While the example here is predominantly perceptual, Husserl later on the same page invokes temporal horizons as having an infinite extension from now to the past and future – a topic which he takes up at length later (Husserl 2008). He also invokes the phenomenon of empathy as well as the field of language and meaning as defining horizonal intentionality ( Crisis §70, 243 and Appendix IV, 358–9, respectively). I cannot treat of these aspects of Husserl’s examination of horizonal intentionality. For the sake of brevity, I contain my analysis to the perceptual case, which also harmonizes with Merleau-Ponty’s analysis. This also makes the connection to pain and suffering more concrete.

For a nice summary of this line of argument, see Zahavi ( 2003 , 96–7). Merleau-Ponty describes this aspect of horizonal intentionality in the following way: “Each object, then, tis the mirror of all the others. When I see the lamp on my table, I attribute to it not merely the qualities that are visible from my location, but also those that the fireplace, the walls, and the table can ‘see’. The back of my lamp is merely the face that it ‘shows’ to the fireplace […] The fully realized object is translucent, it is shot through from all sides by an infinity of present gazes intersecting in its depth and leaving nothing there hidden” ( 1945 /2012, 71).

Geniusas’s work on this subject is exceptional and thorough. For reasons of space, I am only able to address these worries in a preliminary way. Part of the issue here is that Geniusas’s Husserlian analysis is embedded in an attempt to trace the history of Phenomenological analyses of pain’s intentionality; he is sensitive to Husserl’s desire to synthesize the works of philosophers like Brentano and Stumpf. For more, see Geniusas ( 2014 ). As should be clear, my reconstruction of Merleau-Ponty’s account of horizonal intentionality, as applied to pain, shows that we should not think of bodily affect as a non-intentional sensation, but as part of a holistic embodied milieu that orients the subject in a motor-intentional arc towards the world. I think Husserl would agree, but I am framing the point critically here as a response to Geniusas’s way of interpreting Husserl.

My critique of Klein’s imperativism in this section is usefully contrasted with an important phenomenological critique of Klein from Miyahara ( 2021 ). Miyahara notes that imperative theories of pain “overcome the objective concept of the body by acknowledging its inherent intelligence” (307). But he complains that this intelligence is still too dualistic on account of, “the body motivat[ing] the disembodied agent into protective actions by communicating with it in terms of mental contents” (ibid). Here we are agreed that “pain-coping does not involve a dualistic separation between the body and the agent […]” Rather, in pain experience, there is a “form of habitual behaviour, i.e., a patterned embodied response to situations shaped through the agent’s history of engagement with the natural and socio-cultural environment (ibid). I have tried to reconstruct my view in a way that anticipates and avoids these kinds of concerns. That being said, I do not agree with Miyahara when he argues that cultural conditioning constitutes a worry for imeprativists like Klein (cf. Miyahara 2021 , 306). The fact that we can learn to react to pain in different ways according to cultural scripts is no argument against the fact that pain’s primary biological role is to motivate the subject to protect the part of the body that hurts. For a related line of argument focusing on the role of imagination and metaphor in making sense of pain, see Miglio and Stanier ( 2022 ).

Note that the Buddhist philosophers we looked at previously would deny this latter claim. That is, they would claim that it is perfectly consistent to say that a bodily pain ( dukkha ) hurts but that it does not cause psychological anguish ( domanassa ). So, the move from pain, to hurt, to suffering seems a bit rushed. Klein collapses the hurtfulness of pains into the category of suffering. The Buddhists give us the conceptual resources to resist that move. For an astute analysis of the category of psychological pain in Indian Buddhism, see Kachru ( 2021 ), in particular: “And though the word “domanassa” was available to be used alongside many other words to enumerate and convey the degree and kinds of distress that comprise the suffering criterial of our way of being in the world, we find it very early used pairwise with dukkha to comprehend the totality of possible forms of pain, physical and psychological” (133).

On this point, Adams ( 2020 ) helpfully points out that, “For rational agents, pain has unconscious and/or conscious symbolic punch: not only does it signal bodily dysfunction and environmental misfits; it also signifies that the individual in one degree or another falls short of being a perfect specimen, that the individual is not only vulnerable but mortal. Burning pain not only warns us to take our finger off the hot stove; it is also one face of death!” (279).

My thanks to an anonymous referee, Jennifer Nagel, and Danny Goldstick for pressing me to be clearer on this point.

These points are orthogonal to another important line of argument for decreasing the conceptual distance between pain and suffering. By distinguishing between transient, acute, and chronic pain, we can see how feeling pain in a chronic case would entail that feeling pain is a mode of suffering. However, my aim here is to illustrate the implicit way in which existential suffering is present as a background condition of the biological facts of even ordinary non-acute and non-chronic pains. My thanks to an anonymous referee for pointing out this line of argument. For more on this, see Leder ( 1990 , Ch. 3) and Geniusas ( 2020 , Ch. 4). Also, see de Haro ( 2016 ) for an astute analysis of how different forms and intensities of pain shape the structure of attention.

This argument builds on the one we explored earlier in §2 on the physical suffering of the poor and the mental suffering of the privileged (CŚ II.8 and CŚ-ṭ §135, Lang 2003 , 139).

Though, I think Buddhist philosophers – and here I am inclined to agree with them – would argue that this anxiety is precisely masterable. More on this briefly in the conclusion.

Here my view should be contrasted with Geniusas’s ( 2020 ). I disagree that “pain isolates the sufferer within the field of presence, which the suffer experiences as disconnected from the past and the future” (98). On the contrary, what I am arguing is that our experience of pain marks out the articulation of time in the course of a life narrative not only at the end, thus motivating the paradox pointed out by Adams ( 2020 ) but that temporal features of the phenomenology of chronic pain conditions are also implicitly present in the way that ordinary pains represent the inevitable march of time in the course of a fragile life. Pain marks the passage of biological time (cf. Miglio and Stainer 2022 for some remarks in this direction couched at the socio-cultural – rather than, biological – level).

Adams, M. M. (2020). Some paradoxes of pain for rational agency. In D. Bain, M. Brady, & J. Corns (Eds), Philosophy of Suffering: Metaphysics, Value, and Normativity . Routledge

Aydede, M. (2005). Pain: New Essays on its Nature and the Methodology of its Study . MIT Press.

Book Google Scholar