Periodical Essay Definition and Examples

Print Collector/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

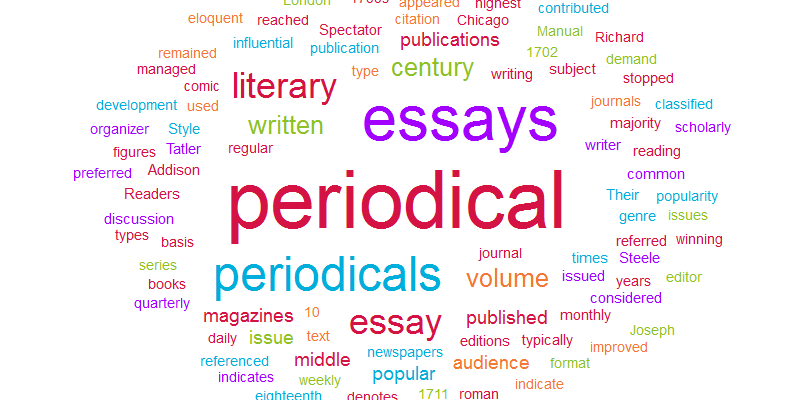

A periodical essay is an essay (that is, a short work of nonfiction) published in a magazine or journal--in particular, an essay that appears as part of a series.

The 18th century is considered the great age of the periodical essay in English. Notable periodical essayists of the 18th century include Joseph Addison, Richard Steele , Samuel Johnson , and Oliver Goldsmith .

Observations on the Periodical Essay

"The periodical essay in Samuel Johnson's view presented general knowledge appropriate for circulation in common talk. This accomplishment had only rarely been achieved in an earlier time and now was to contribute to political harmony by introducing 'subjects to which faction had produced no diversity of sentiment such as literature, morality and family life.'" (Marvin B. Becker, The Emergence of Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century . Indiana University Press, 1994)

The Expanded Reading Public and the Rise of the Periodical Essay

"The largely middle-class readership did not require a university education to get through the contents of periodicals and pamphlets written in a middle style and offering instruction to people with rising social expectations. Early eighteenth-century publishers and editors recognized the existence of such an audience and found the means for satisfying its taste. . . . [A] host of periodical writers, Addison and Sir Richard Steele outstanding among them, shaped their styles and contents to satisfy these readers' tastes and interests. Magazines--those medleys of borrowed and original material and open-invitations to reader participation in publication--struck what modern critics would term a distinctly middlebrow note in literature. "The most pronounced features of the magazine were its brevity of individual items and the variety of its contents. Consequently, the essay played a significant role in such periodicals, presenting commentary on politics, religion, and social matters among its many topics ." (Robert Donald Spector, Samuel Johnson and the Essay . Greenwood, 1997)

Characteristics of the 18th-Century Periodical Essay

"The formal properties of the periodical essay were largely defined through the practice of Joseph Addison and Steele in their two most widely read series, the "Tatler" (1709-1711) and the "Spectator" (1711-1712; 1714). Many characteristics of these two papers--the fictitious nominal proprietor, the group of fictitious contributors who offer advice and observations from their special viewpoints, the miscellaneous and constantly changing fields of discourse , the use of exemplary character sketches , letters to the editor from fictitious correspondents, and various other typical features--existed before Addison and Steele set to work, but these two wrote with such effectiveness and cultivated such attention in their readers that the writing in the Tatler and Spectator served as the models for periodical writing in the next seven or eight decades." (James R. Kuist, "Periodical Essay." The Encyclopedia of the Essay , edited by Tracy Chevalier. Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997)

The Evolution of the Periodical Essay in the 19th Century

"By 1800 the single-essay periodical had virtually disappeared, replaced by the serial essay published in magazines and journals. Yet in many respects, the work of the early-19th-century ' familiar essayists ' reinvigorated the Addisonian essay tradition, though emphasizing eclecticism, flexibility, and experientiality. Charles Lamb , in his serial Essays of Elia (published in the London Magazine during the 1820s), intensified the self-expressiveness of the experientialist essayistic voice . Thomas De Quincey 's periodical essays blended autobiography and literary criticism , and William Hazlitt sought in his periodical essays to combine 'the literary and the conversational.'" (Kathryn Shevelow, "Essay." Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837 , ed. by Gerald Newman and Leslie Ellen Brown. Taylor & Francis, 1997)

Columnists and Contemporary Periodical Essays

"Writers of the popular periodical essay have in common both brevity and regularity; their essays are generally intended to fill a specific space in their publications, be it so many column inches on a feature or op-ed page or a page or two in a predictable location in a magazine. Unlike freelance essayists who can shape the article to serve the subject matter, the columnist more often shapes the subject matter to fit the restrictions of the column. In some ways this is inhibiting because it forces the writer to limit and omit material; in other ways, it is liberating, because it frees the writer from the need to worry about finding a form and lets him or her concentrate on the development of ideas." (Robert L. Root, Jr., Working at Writing: Columnists and Critics Composing . SIU Press, 1991)

- The Essay: History and Definition

- exploratory essay

- What Is Enlightenment Rhetoric?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- Biography of Samuel Johnson, 18th Century Writer and Lexicographer

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- Definition of Belles-Lettres in English Grammer

- Samuel Johnson's Dictionary

- Definition and Examples of Formal Essays

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- 4 Publications of the Harlem Renaissance

- Samuel Johnson Quotes

- Life and Work of H.L. Mencken: Writer, Editor, and Critic

- Top Books About The Age of Enlightenment

What Is a Periodical Essay?

Publication Date: 06 Mar 2019

A periodical essay is a type of writing that is issued on a regular basis as a part of a series in editions such as journals, magazines, newspapers or comic books. It is typically published daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly and is referenced by volume and issue.

Volume indicates the number of years when the publication took place while issue denotes how many times the periodical was issued during the year. For example, the May 1711 publication of a monthly journal that was first published in 1702 would be referred to as, “volume 10, issue 5”. At times, roman numerals were also used to indicate the volume number. For the citation of text in a periodical, such a format as The Chicago Manual of Style is used.

The periodical essay appeared in the early 1700s and reached its highest popularity in the middle of the eighteenth century. London magazines such as The Tatler and The Spectator were the most popular and influential periodicals of that time. It is considered that The Tatler introduced such literary genre as periodical essay while The Spectator improved it. The magazines remained influential even after they stopped publications. Their issues were later published in the form of a book, which was in demand for the rest of the century.

Richard Steele and Joseph Addison are considered to be the figures who contributed the most to the development of the eighteen-century literary genre of periodical essays. They managed to create a winning team where Addison was more of an eloquent writer while Steele made his contribution by being an outstanding organizer and editor.

Typically, the essays can be classified into such two types as popular and scholarly. Also, this literary form was written for an audience of professionals who preferred to read business, technical, academic, scientific and trade publications.

However, for the most part, the periodicals were about morality, emotions and manners. Readers expected essays to be common sense and thought-provoking. Publications were relatively short and mainly characterized as those which provide an opinion inspired by contemporary events. Periodicals were meant to be not “heavy”, especially those which were referred to as popular reading. The majority of topics in the periodicals were supposed to be appropriate for the common talk and general discussion.

Many essays were written for female readers as a target audience. Periodicals were aimed at middle-class people who were literate enough and could afford to buy the editions regularly. The essays were written in a so-called middle style and high education was not required for reading the majority of the contents. Over time, many periodical writers shaped their styles in order to satisfy the literary taste of the audience.

All periodical essays tend to be brief but texts written by a columnist and freelance essayist would slightly differ in length. The former writes his material trying to shape the subject of discussion to fit the requirements of the column. The latter though can take advantage of a more liberating approach by crafting his work the way he wants as long as his text manages to effectively highlight the subject.

Periodicals evolved in the 19 th century and single essays were almost fully replaced by serial essay publishing. The writings became more eclectic, flexible and brave being at the same time literary and conversational.

Do you need the help of a professional essay writer ? Contact us today and get quality assistance with writing any type of paper. Getting good grades has never been so easy!

Periodical Essay – Definition & Meaning

The periodical essay is called ‘periodical’ because the periodical essays appeared in journals and magazines which appeared periodically in the eighteenth century. It flourished in the 18th century and died in the same century. Its aim was public rather than private. Its object was social reformation.

It conformed to the neo-classical ideal which placed a premium, not so much on the personal revelation and confession of the author himself as on his duty to inform the mind and delight the heart of the reading public. The periodical essay differs from the essays of Montaigne, Bacon, Hazlitt or Lamb because their essays were published collectively at one time in a single volume and presented a personal point of view to the readers.

The periodical essay like its other brothers, the novel and coffee houses tended to refine the taste and tone, the cultural and moral outlook of the educated and the wealthy middle classes. It was the literature of the middle classes, for the middle classes and by the middle classes of the eighteenth century. It has all the features of journalism-a wider appeal, a larger coverage. Brevity and precision, simple and chaste English, delicate tone and elegant style. The periodical essay had a double aim: to amuse and to improve. The subjects discussed by the periodical essayists were connected with the varied aspects of the social life with the city of London in the center. The style was deliberately easy, lucid and refined.

The periodical essay began In the year 1709 with the first periodical essay appearing in the Tattler on April 12. The real makers of the periodical essay were men of contrasted characters and temperaments. The Tattler and The Spectator set the fashion for all periodical papers and were soon followed by other imitations. Steele himself brought out the Guardian in 1713, and soon a host of other imitations like the Female Tattler, Whisper made their appearance and thus testifying to the popularity of this class of writing. The best of the wits of the age contributed to all these papers. Swift, Pope, Berkeley. Congreve, Parnell and others wrote occasionally for these papers and the vogue thus created for literary journalism continued right through the century and the next. Almost all the great figures in the literary field contributed either occasionally or regularly to such periodicals. Apart from the political nature of such periodicals, these papers became the chief organ for literary self-expression. Addison started Whig Examiner and Steele came out with Examiner, representing the Tory point of view. Fielding likewise was connected with the Champion; and the Craftsman and the Common-sense were two other journals of the same political colouring as the Champion. Ambrose Phillips made use of the Free Thinker to air forth his views. There were the Plain Dealer and the Farrot too. The growth of the political parties gave to these periodicals a strong party bias and each paper became the organ of one political party or the other. But while their political nature and learning are unmistakable their use of literary wits as the service ground is encouraging. They afforded to the literary aspirants an outlet for self-expression and by so doing, brought out to the full their talents.

The greatest and the best figures of the periodical essay are Addison and Steele. Addison and Steele was also associated with a darker and more somber personality, the greatest and most biting satirist of the age, Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) who transcended the limits of the periodical essay. His important contributions to the periodical essay are :

- Predictions for the Year 1708.

- Account of the Death of Mr. Partridge,

- Letter to a Very Young Lady on Her Marriage,

- Meditations upon a Broom-stick, etc.

In the pleasant art of living with one’s fellows, Addison is easily a master, “Swift is the storm, roaring against the ice and frost of the late spring of English life. Addison is the sunshine, which melts the ice and dries the mud and makes the earth thrill with light and hope. Like Swift, he despised shams, but unlike him, he never lost faith in humanity and in all his satires there is a gentle kindliness which makes one think better of his fellow men, even while he laughs to their little vanities” (Long).

To an age of fundamental coarseness and artificiality Addison came with a wholesome message of refinement and simplicity, much as Ruskin and Amold spoke to a later age of materialism; only Addison’s success was greater than theirs because of his greater knowledge of life and his greater faith in men. He attacks all the little vanities and all the big vices of his time, not in Swift’s terrible way, which makes us feel hopeless of humanity, but with a kindly ridicule and gentle humour which takes speedy improvement for granted. To read Swift’s brutal “Letters to a Young Lady”, and then to read Addison’s ‘Dissection of a Beau’s Head” and his “Dissection of a Coquette’s Heart” is to know at once the secret of the latter’s more enduring influence.

Addison’s essays are the best picture of the new social life of England. They advanced the art of literary criticism to a much higher stage than it had ever before reached, and led Englishmen to a better knowledge and appreciation of their own literature. Furthermore, in Ned Softly the literary dabbler, Will Wimble the poor relation, Sir Andrew Freeport the merchant, Will Honeycomb the fop, and Sir Roger the country gentleman, they give us characters that live forever as part of that goodly company which extends from Chaucer’s country parson to Kipling’s Mulvaney.

Addison and Steele not only introduced the modern essay, but in such characters as cited above they herald the dawn of the modern novel. Of all his essays the best known and loved are those which introduce us to Sir Roger de Coverley, the genial dictator of life and manners in the quiet English country.

In style these essays are remarkable as showing the growing perfection of the English language. Johnson says, “Whoever wishes to attain an English style, familiar but not coarse, and elegant but not ostentatious, must give his days and nights to the volumes of Addison”. And again he says, “Give nights and days, sir, to the study of Addison if you mean to be a good writer, or, what is more worth, an honest man”.

So the periodical essays, more particularly the essays of Addison and Steele, are well worth reading once for their own sake, and many times for their influence in shaping a clear and graceful style of writing.

Also Read :

- Compare Hamlet with Macbeth, Othello and other Tragedies

- “The Pardoner’s Tale” is the finest tale of Chaucer

- Prologue to Canterbury Tales – (Short Ques & Ans)

- Confessional Poetry – Definition & meaning

Steele is the originator of the Tattler, and joins with Addison in creating the Spectator-the two periodicals which, in the short space of less than four years, did more to influence subsequent literature than all other magazines of the century combined. On account of his talent in writing political pamphlets, Steele was awarded the position of official gazetteer. He could combine news, gossip and essays instantaneously.

Johnson’s Rambler is usually ranked as the first of the classical periodicals after The Guardian. Johnson also contributed to The Idler and The Adventurer. His style is mannered and Latinised. His is a learned prose. His vocabulary is heavy and sonorous. He is the classic of pedantic prose. Another luminary of the periodical essay is Oliver Goldsmith. He started his career as a periodical essayist with his contributions to The Bee, a weekly which did not survive its 8 th number. Among his best periodical essays mention must be made of “The City Night Piece”, “The Public Ledger”, “The Citizens of the World”, etc. Oliver Goldsmith should be remembered for his sympathetic humour, magic of his personality, simplicity, chastity and carefulness. His style is always light and refreshing. His descriptions are vivid and picturesque. He carried the personal vein of Steele, his compatriot, a step further and heralded the autobiographical manner of Charles Lamb.

Later on the romantic writers like Lamb, Hazlitt and De Quincey also contributed their essays to the periodicals of their time, but their essays are very much different in spirit of manner from those of the real practitioners of the periodical essay.

The rise of the periodical essay can be attributed to various causes such as vast growth of a reading public, rise of the middle classes, growth and development of numerous periodicals, the rise of the two political parties (the Whig and the Tory), the rise of the coffee-houses as centers of social and political life, the need of social reform and the popular reception accorded by the public to the periodical literature. The periodical essay was a very popular form of literature and communication and recreation in the eighteenth century because it was the mirror of the Augustan age in England” (A. R. Humphreys). It was the social chronicler of the time. It was particularly suited to the genius of the new patrons, because it was the literature of the bourgeoisie. It gave them what they wanted. It gave them pleasure as well as instruction. It was a delicate and sensitive synthesis of literature and journalism. It was neither too ‘literary’ to be comprehended and appreciated by the common people nor too journalistic to meet the fate of ephemeral writings. It could be read. Appreciated, and discussed at the tea-table or in the coffee-house. Its lightness and brevity were its two major popularising factors. The periodical essay, normally, covered not more than two sides of a folio half-sheet; quite often it was even shorter. Furthermore, it was suited to the moral temper of the age. It struck a delicate and rational balance between the strait-jacketed morality of the Puritan and the reckless Bohemianism of the Cavalier. In the words of A. R. Humphreys, “conventionally the code of pleasure was that of the rake: Steele and Addison wished to equate it with virtue, and virtue with religion”. Above all, the periodical essay has a wider appeal to various sections of the eighteenth century society. It appealed not only to the lovers of literature and literary criticism, but also to those who were interested in men and manners, fashions and recreation. It appealed very well to women. The authors were writing for men as well as women, said Mrs. Jane H. Jack.

The periodical essay further avoided heated religious and political controversies and maintained a balance, following generally a middle path. Mr. Spectator says in the very first issue of The Spectator: “I never espoused any party with violence, and am resolved to observe an exact neutrality between the Whigs and Tories…” It also showed a healthy interest in trade, and thus appealed to the traders and merchants too. Lastly, the periodical essay became popular due to the chaste style of its contributors. They used simple and everyday language. It covered all accounts of gallantry, pleasure and entertainment, poetry, learning, foreign and domestic news.

PLEASE HELP ME TO REACH 1000 SUBSCRIBER ON MY COOKING YT CHANNEL (CLICK HERE)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel

🔥 Don't Miss Out! Subscribe to Our YouTube Channel for Exclusive English Literature, Research Papers, Best Notes for UG, PG & UGC-NET!

🌟 Click Now! 👉

Recent Posts

Describe The Happy Ending Of Play Antony and Cleopatra

The Politics of Antony and Cleopatra By Shakespeare

Some Explanation from Indian English Prose

Summary Of No Man’s An Island By John Donne

Ideas Contained In The Essay The Secret of Work by Swami Vivekanand

Education for New India By C. Rajagopalachari

Indian Civilization and Culture By M.K. Gandhi

Critical Analysis Of Night of The Scorpion-Nissim Ezekiel

Explanation Of An Introduction By Kamala Das

Critical Analysis Of An Introduction By Kamala Das

- Buy Custom Assignment

- Custom College Papers

- Buy Dissertation

- Buy Research Papers

- Buy Custom Term Papers

- Cheap Custom Term Papers

- Custom Courseworks

- Custom Thesis Papers

- Custom Expository Essays

- Custom Plagiarism Check

- Cheap Custom Essay

- Custom Argumentative Essays

- Custom Case Study

- Custom Annotated Bibliography

- Custom Book Report

- How It Works

- +1 (888) 398 0091

- Essay Samples

- Essay Topics

- Research Topics

- Uncategorized

- Writing Tips

How To Write a Periodical Essay

December 26, 2016

Periodical essay papers are a journey or journal through one's eye or characters develop based on series of events accordingly.

Essay papers based on periodical is affected by century, culture, language and belief of the community, showing the mirror of their age, the reflection of their thinking. How literature acts as a medium in daily’s usage of a population in certain areas affect most on how this periodical journal is produced, how characters are developed, what makes the journal stands out from the others and so on.

How To Write?

Joseph Addison and Steele have applied periodical essay in their papers which are Tatler in 1709-1711 and Spectator in 1711-1712 and again in 1714. This means that custom periodical essay papers have been recognized and used the long time ago to produce series of events through custom essay papers. It is said that custom periodical essay papers existed even before Joseph Addison and Steele start their work, through sketches and letters from various features.

The most successful periodical essays can be a long list. Most influential custom periodical essay papers include Henry Fielding’s Covent Garden Journal in 1752, Samuel Johnson’s Rambler in 1750- 1752, Henry Mackenzie’s Mirror in 1779-1780, Oliver Goldsmith in 1757 to 1772 to name a few.

Cultures and analysis of the ways relate to the associations are reflected through actors characterization and goals for the particular projects. The role of maintaining language practices in the community allows these essayists to work on their periodical essay papers customization. College essay papers also related to social networks in a culture by the time these papers are produced.

That is basically how these popular periodical essays gain attention from worldwide at their century.

Editorial Policies

The impact on periodical essay papers was immediate through the eighteenth century. It is definitely beyond Addison and Steller's expectations as well as publications. These guys re-modeled their content and editorial policies of their periodical essay, Tatler, and Spectator, as well as Guardian into different languages outside England, gained immediate attention from a community outside England.

Oliver Goldsmith from 1757 to 1772 also contributed to numbers of custom periodical essay including The Monthly Review with ran to eight weekly numbers. His best work, The Citizen of the World in 1762 proves that he is attractive, lack of formality and sensitive as the main attraction to his periodical essay.

Periodically essay is still emerging despite the deep roots and far-reaching networks by the eighteenth century. These essay papers belong to definite period due to its tight connection in publishing practices, politics, and law.

Howeve,r the numbers of publication rise and fall considerably even at times of national crisis.

Customs writing service can do all of your college assignments! Stop dreaming about legal write my essay for me service! We are here!

Sociology Research Topics Ideas

Importance of Computer in Nursing Practice Essay

History Research Paper Topics For Students

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy. We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related emails.

Latest Articles

Navigating the complexities of a Document-Based Question (DBQ) essay can be daunting, especially given its unique blend of historical analysis...

An introduction speech stands as your first opportunity to connect with an audience, setting the tone for the message you...

Embarking on the journey to write a rough draft for an essay is not just a task but a pivotal...

I want to feel as happy, as your customers do, so I'd better order now

We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits. By clicking “Accept All”, you consent to the use of ALL the cookies. However, you may visit "Cookie Settings" to provide a controlled consent.

- Advertise with us

- History Magazine

The Rise of the Literary Periodical

In the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, what has been called the emerging ‘public sphere’ saw the rise of printed pamphlets and journals catering to novel aspirations, anxieties and interests of the people…

In the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution , what has been called the emerging ‘public sphere’ saw the rise of printed pamphlets and journals catering to novel aspirations, anxieties and interests of the people.

The late 17th and early 18th century witnessed the transformation of printed journals through the amalgamation of not just news but also socio-political commentaries, opinion essays, letters and sometimes even fiction and poetry – into a new kind of publication called the periodical.

A man named Richard Steele is often credited with having popularised, if not invented the literary form of periodical essays. Yet, scholars have shown that Motteux’s Gentleman’s Journal and Daniel Defoe’s Review were the true predecessors of Steele’s widely read periodicals The Tatler (1709-1711) and The Spectator (1711-1712). The great German philosopher, Jürgen Habermas argues that these periodicals started by Steele and his friend Joseph Addison played an immense role in the public sphere by acting as the linkage between the British coffeehouses , the political domain of rational-critical debate and formation of a ‘public opinion’.

Periodical literature also contributed majorly to the development of modern authorship and acquainted the readers to the authors who lived and interacted among them. The Tatler and The Spectator, like other popular periodicals, used a mode of invasive ‘spectation’ that involved not just the usage of sight but also other bodily senses. Professor Anthony Pollock argues that The Spectator makes a deliberate transition from the conversational surveillance towards visual one. He writes “Addison and Steele’s personae characteristically do not intervene, they withdraw.” While in The Tatler, the reader gets a sense of the author actively desiring to say something, Mr Spectator’s most amusing idiosyncrasy is his taciturnity. Mr. Spectator thus presented a masculine mode of transcendent reporting, writing more than gossip – contributing to the literary posture of spectatorship which greatly appealed to its astoundingly large reader base.

Another development during this period was the increase in wealth and leisure of the English middle classes and the improvement in women’s education that turned several women into readers. Though, undoubtedly the early modern public sphere was dominated by men, a large number of publishers jumped at the opportunity to expand their female readership. Starting with John Dunton’s Athenian Mercury (1691– 97), many periodicals began devoting one or more issues (or sections) to topics that were likely to please and attract the ladies. A short-lived experiment was the renaming of the October issue of the Gentleman’s Journal, as ‘The Lady’s Journal’. Amusingly, the first imitators of The Tatler were ostensibly women who published The Female Tatler three times a week for about a year. Although The Female Tatler claimed to have been penned by “A Society of Ladies”, in reality, the author was a man called Bernard Mandeville. In later decades, when women actually began publishing journals, unlike ‘Men’s Periodicals’, their themes remained mostly domestic and rarely political.

Although, most of these periodicals were read in coffeehouses, many were also delivered at homes and book stores. The authors of these popular periodicals, like Steele and Addison, not just frequented the coffeehouses but even indicated their sources vividly. For instance, in the premier issue of The Tatler, the author mentions “All accounts of gallantry, pleasure, and entertainment shall be under the article of White’s Chocolate-house; Poetry, under that of Will’s Coffee-house; Learning, under the title of Grecian; Foreign and Domestic News you will have from Saint James’s Coffee-house; and what else I have to offer on any other subject shall be dated from my own Apartment.” Interestingly, after being printed in London, these periodicals did not remain restricted to the city but were also disseminated in various provinces like Oxford and Dublin, where they enjoyed large readership.

The advent of the age of periodicals cannot be simply associated publications related to the news revolution of the 17th century. Many of the 17th century newspapers, often disseminated in coffeehouses were seen as a major source of threat by the ruling class. The crown attempted to suppress these ‘dangerous’ publications through the Licensing Act of 1662 which gave the state a monopoly on the printing of news, making The London Gazette the kingdom’s only official newspaper post 1665. Although this was true on paper, in reality several unofficial publications were printed, distributed and widely read. There were instances, such as the Algiers leak case, when sensitive information was leaked by State office workers to coffeehouses which resulted in a breach of national security and put coffeehouses owners and newspaper publishers in an unfavourable position. Through various laws, the Crown made numerous attempts to restrain the spread of seditious and irreligious newspapers but was never totally successful.

The content and literary style of the popular periodicals were very different from the newspapers. As historian Brian Cowan notes, Steele and Addison, like Defoe disapproved of news mongering and never supported irresponsible interference in matters of the State. The new public sphere was therefore not one that obsessed solely over news and gossip. The periodicals were becoming an important medium not for indecent, heated debates but for refined, socio-political and moral discussions – creating stable, civilised and courteous public spaces.

Disha Ray is a student of History at St. Stephen’s College, University of Delhi. She is particularly interested in questions of gender and minority histories.

Published: July 14th, 2021.

History in your inbox

Sign up for monthly updates

Advertisement

Next article.

English Coffeehouses, Penny Universities

English coffee houses of the 17th and 18th century were meeting places of ideas, science, politics and commerce, known as penny universities…

Popular searches

- Castle Hotels

- Coastal Cottages

- Cottages with Pools

- Kings and Queens

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Rise of the Periodical Essay in the 18th century

Related Papers

Cambridge History of Literary Criticism

James Basker

The rise of periodical literature changed the face of criticism between 1660 and 1800. To chart a course through this jungle of literary growth and its implications for the history of criticism, it is useful to look at three basic periods within which slightly different genres of periodical predominated and left their mark on literary culture. The first, from the mid- 1600s to 1700, saw the infancy of the newspaper and, from about 1665, the establishment of the learned journal; during the second, from 1700 to 1750, the periodical essay enjoyed its greatest influence, and the magazine or monthly miscellany, with all its popular appeal, came to prominence; in the third, from about 1750 to 1800, the literary review journal emerged in a recognizably modern form and rapidly came to dominate the practice of criticism.

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Girija Suri

Claire Boulard

In the aftermath of the 1688 ‘Glorious Revolution’, pamphlets debating revolution, novelty and change were numerous. Many of them raised dangerous questions which potentially challenged and threatened the existing patriarchal and religious order. Among the mooted issues were the sovereignty of the people, the right to rebel against authority and to choose the sovereign, and the sinful nature of resistance or obedience. There was therefore a need to reconcile changes and tradition and to present the new era as a period of positive and limited changes. The Revolution therefore also opened an era of moral reflection that rejected the loose and rakish morals of the Restoration regime along with the theory of the Divine Right of Monarchs. It was this conservative agenda that mostly the Whigs supported in the late seventeenth century and in the early decades of the eighteenth century, in particular by launching a new form of journal: the periodical. These periodicals, a large number of wh...

Encyclopedia of the Essay

Imre Szeman

Achmad Firdaus

Mark R Frost

Draft chapter for the proposed Cambridge HIstory of the Indian Ocean

Eighteenth-Century Studies

Brian Cowan

Jürgen Habermas used the coffeehouse and the periodical essays of Addison and Steele as prime examples of his concept of an eighteenth-century "public sphere." This article revisits Addison's and Steele's attitudes toward the coffeehouse and argues that their understanding of public political life must be read within the context of Whig political fortunes in the later years of Queen Anne's reign. Their purpose was not to celebrate the emergence of a public sphere, but rather to shift the grounds of political debate away from the contentious issues of war and religion that threatened the security of Whig politics after the trial of Sacheverell and the collapse of the junto ministry in 1710. NB: This article offers a revisionist study of the political importance of the periodical essays of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in the early eighteenth century. It focuses on Addison‘s and Steele‘s attitudes towards the role of the coffeehouse in English society and it argues that their understanding of public political life must be understood within the context of Whig political fortunes in the later years of Queen Anne‘s reign. The purpose of Addison‘s and Steele‘s essays was not to celebrate the emergence of an open 'public sphere‘, as has often been assumed, but was rather to shift the grounds of political debate away from the contentious issues of war and religion that threatened the security of Whig politics after the trial of Henry Sacheverell and the collapse of the junto ministry in 1710. Work for this article stimulated my current interest in the broader media politics surrounding the Sacheverell trial that has been my major research interest for the past several years. (Brian Cowan, Feb. 2011)

Susan Oliver

In the 2 April 1836 number of the New-Yorker the editor Horace Greeley, who was just 25 years old and in the early stages of his career, remarked on the relevance of British Periodicals to the North American public. He singled out the Edinburgh Review for particular tribute: ‘We believe the general opinions and spirit of “the Edinburgh” are more consonant with the feelings and tastes of the educated classes of this country than those of either of its rival Quarterlies.’ 1 There are some key words in that brief declaration. Greeley’s concern with ‘opinions,’ ‘spirit’ and ‘taste,’ and the pointed emphasis he places on their location within the nation’s ‘educated classes,’ suggests an area of common ground between him and the editors of the Edinburgh, though his publications were of a very different format and style. Looking back over thirty-four years of the Edinburgh,and forwards to an American age of journal publication and literary growth, Greeley was poised at a turning point in w...

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Neoclassical Prose in English Literature: Characteristics and the Writers

Back to: History of English Literature All Ages – Summary & Notes

Table of Contents

Introduction

Mathew Arnold called the 18 th century in English Literature as the “age of prose and reason, our excellent and indispensable 18 th century”. Thus Neoclassical age is primarily the “ age of prose and reason ”.

As compared to poetry, the prose of the Neoclassical age developed more. The poetry of the period developed the qualities of prose such as clearness, lucidity, and beauty of expression.

Dryden was a poet and dramatist of repute, but he was also a great writer of prose. He was the first great modern prose writer and also the first great critic.

Similarly, the Pope was a poet, but we find in his poetry, characteristics of good prose-neatness, lucidity, uniformity, and balance. Mathew Arnold declared that Dryden and Pope were the classics of prose and not of poetry .

Characteristics

Pre-conditions of literacy.

Literacy rates in the early 18 th century are difficult to estimate accurately. However, it appears that literacy was higher than the school enrolment would indicate and that literacy passed into the working class as well as the middle and upper classes.

The Churches emphasized the need for every Christian to read the Bible and instructions to landlords indicated that it was their duty to teach servants and workers, how to read and to have the Bible read aloud to them. Moreover, literacy was not confined to men. Females of the time were literate to the same extent.

Circulating Libraries

Circulating libraries in England began for those who were literate in the Augustan period. Libraries were open to all. Circulating libraries were a way for women, in particular, to satisfy their desire for books reading without facing the expense of purchase.

Although, Francis Bacon was the first to have introduced an essay in English Literature during the Renaissance period , its development in England remained rather slow during the 17 th century.

No doubt, prose made rapid progress during the time of Dryden, the essay remained where Bacon had left it until it was formally and forcefully launched by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in the 18 th century as Periodical Essay .

Periodical Essays

A periodical is a magazine, with a distinct literary flavour, published at regular intervals, weekly, monthly, quarterly etc.

The periodical essay was chiefly the invention of Steele when he started The Tatler (1709 A.D.) thrice a week, the chief aim of which was to expose the false arts of life and to recommend a general simplicity in our dress, our discourse, and our behaviour.

Later on, Steele and Addison joined hands and brought the publication of The Spectator . It was a daily paper.

At the beginning of this era, John Dryden was the major critic whereas at the end of it was Dr Samuel Johnson . Though we find criticism in all the major genres of literature like poetry, drama etc. but it mainly developed in prose of the age. All the important critics of the period including Dryden, Pope , Addison, Johnson etc were creative writers as well.

Criticism , like other forms of writing in the 18 th century, became a professional activity but its major and influential supporters were the creative writers who showed critical interest in their essays, treatises etc. Addison and Steele’s The Spectator is a good periodical essay that criticised the prevailing vices.

Here is a detailed summarization of Neoclassical Criticism and important critics

the 18th century was a classical age, an age of prose and reason. The Elizabethan Age had been an age of romanticism, imagination etc. which lacked balance but the 18 th century was marked by reason, good sense, wit and logicism with a fair amount of realism. This was basically the age of prose and reason.

Rise of Novel

Read about the Rise of English Novel in the 18th century

Major Writers

Jonathan swift.

He was a son of English parents. He was very wretched and unhappy at school. He might have become Bishop, but he attained mastery of English prose.

He became one of the greatest prose writers of the Neo-classical age. His important works are The Battle of Book, A Tale of Tub , The Whigs for the Tories, Gulliver’s Travel etc.

Joseph Addison

He was educated at the Charter House and later went to Oxford. He died at the age of 40. He wrote many political pamphlets but didn’t get fame as a pamphleteer. He became famous only through his essays. His important prose writings are The Tatler, the Spectator, The Guardian etc.

Richard Steele

He was an unfortunate person, due to his own disposition. He was educated at Charter House and then moved to Oxford without taking a degree. His important works are The Funeral (Drama), The Guardian, The Englishman, The Reader etc.

Daniel Defoe

He was born and died in London. He was one of the best prose writers of his time. His important works are The Dissenters, The True Englishman, Robinson Crusoe , Roxana, A New Voyage Round the World etc.

Presentation

The Periodical Essay and Journal of The 18th Century

Updated August 7, 2022

Could you guess as why periodical essay came into being as special genre of prose writing? If not, let me overstate that these essays were an elegant piece of writing to appeal middle class of England in 18th Century. These periodical articles for journals aimed changes in social conduct and reformation in larger context. Precisely, Periodical essays were first social documents of modern writing.

Although, the literary history terms entire 18 th century as the Age of Pope but the Age of Queen Anne (1665-1714) is remarkable for the growth and development of prose literature. This age witnessed the flowering of the periodical essay in the hands of great writers like Addison and Steele. The beginning of prose fiction has also its root in this age.

The Periodical Essay and Journal

The periodical Essay forms a special branch of the 18 th century English prose. In fact, it was entirely a new kind of development in the field of prose writing. In this regard, it is imperative to know why was the term ‘Periodical Essay’ used for this genre of writing. It is called ‘periodical’ because these essays appeared in journals and magazines which were published periodically in those days. These essays were different in contents and style from other prose writings.

Moreover, these are regarded as the social documents on the 18 th century England. The object of these essays was to bring about social reformation. It is interesting to note that these essays were of the middle classes, for the middle classes and by the middle classes. These essays became highly popular the moment they were published.

The reasons of their popularity had to do with their brevity, precision, a wider appeal, larger coverage, simple and chaste English and elegant style. These essays provided amusement as well as improvement in social behavior. The writers of this age wrote many periodical essays and journal which portrays the then middle classes and deprived classes.

Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729) and Joseph Addison (1662-1719) as Founding Father of Periodical Essay

Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison were the real founders of periodical essays. Steele was the founder of “ The Tatler ” (1709). It appeared three times a week. He used to write under the pseudonym of Mr. Isaac Bickerstaff and recommended truth, innocence, honour and virtue as the chief ornaments of life.

Later Addison and some other prose writers started contributing to it. “ The Tatler ” became very popular but lasted less than two years. But within two months Steele launched “ The Spectator” in collaboration with Addison. But it was not simply “ The Tatler ” revised. It was different in the sense that it avoided the political affairs and in place of several short essays, it consisted of a single long essay. It used to appear daily.

“ The Spectator ” had two principal aims- the first was to present in the essays a true and faithful picture of the 18 th century life and the second was to bring about a moral and social reform in the conditions of the time. Steele and Addison combated the social evil of the time through their periodical essays.

Simply put, both the writers commented on the gay fopperies, the ball dances, the club sittings, the cock-hunting, the violence of political and religious strife and the ugliness of the society. In fact, they were the voices of a new and civilized urban life. Both these writers worked as the great educators of the 18 th century. They established “essay” as an important branch of English literature.

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) as Profound Contributor to Periodical Essay

Jonathan Swift of “Gulliver’s Travels” fame also contributed to periodical essays. But his contributions to “The Tatler”, “The Spectator” and also to “Intelligencer” were meager. His “journal to Stella” is an outstanding description of the contemporary characters and political events. His genius, however, was best revealed in his work fiction.

Daniel Defoe (1661-1731) as Pioneer of Periodical Essays

Daniel Defoe is said to be the pioneer of periodical essays. His important essays are found in “The Review”. Later “The Little Review” appeared in which he contributed essays on the vices and follies of the society. He also contributed to “Mist’s Journal” and “Applebee Journal”.

On top, Daniel Defoe has also written other prose and novels. His semi-fictional work “Robinson Crusoe” made him famous. Later he wrote successful works like “Moll Flanders”, “Colonel Jacque” and “The Unfortunate Mistress” or “Roxana”. All these works are closer to being novels.

Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) As Reviver Of Periodicals

He was also a great prose writer of the 18 th century. Though he is famous for his monumental work “The Dictionary of the English Language “, he contributed to “The Gentleman magazine” and his own periodical “ The rambler ”. His essays were full of deep thought and minute observation. “The Rambler” is credited with re-establishing the periodical essay when it was in the danger of being overtaken by the daily newspapers.

Oliver Goldsmith (1728- 1774) as Mighty Periodical Writer

Oliver Goldsmith contributed to “ The Morality Review ”. He also contributed to several other periodicals and enriched the genre. His essays reveal his extraordinary power, boldness, tenderness and originality of thoughts. They are also remarkable for the minute observation of man and manners. “ The Traveller ”, and “ The Deserted Village ” are the prominent writing of the Oliver Goldsmith.

The periodical essays and journals were immensely popular during the 18 th century. One of the reasons was their avoidance of heated religious and political controversies. These essays generally maintained the middle path. Unfortunately, this form of literature died in the same century in which it flourished.

Beyond Periodical Essay Under Literature Reads

- How Does Quotes of William Wordsworth on Nature Feel Like?

- What is the Summary of Mirror by Sylvia Plath?

- What is there in Summary of Tulips by Sylvia Plath?

- Stanza by Stanza Summary of The Road Not Taken!

- Check Analysis of Walt Whitman’s the Song of Myself!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Legal Details

- Theories and Methods

- Backgrounds

Models and Stereotypes

- Europe on the Road

- European Media

- European Networks

- Transnational Movements and Organisations

- Alliances and Wars

- Europe and the World

- Central Europe

- Balkan Peninsula

- Eastern Europe

- Northern Europe

- Western Europe

- Southern Europe

- Non-European World

- Education, Sciences

- Social Matters, Society

- Law, Constitution

- Migration, Travel

- Media, Communication

- Agents, Intermediaries

- Theory, Methodology

- Economy, Technology

- 15th Century

- 16th Century

- 17th Century

- 18th Century

- 19th Century

- 20th Century

- 21st Century

Advanced Search

Anglophilia

British and American Constitutional Models

Entstehung des Sports in England

European Landscape Garden

Moral Weeklies

Shakespeare

Transfer des englischen Sports

"Dutch Century"

Dutch Anatomy

European Fashion

From the "Turkish Menace" to Orientalism

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire

Church and 'Turkish Threat'

East West Literary Transfers

Islam and Islamic Law

Islam-Christian Transfers of Military Technology

Istanbul as a hub of early modern European diplomacy

Ottoman History of South-East Europe

Oriental Despotism

German Role Models

Deutsche Musik in Europa

Christian Frederik Emil Horneman

Kulturtransfer Leipzig Kopenhagen

Niels Wilhelm Gade

German Education and Science

Germanophilie im Judentum

Wertherfieber

Graecomania and Philhellenism

Christlicher Hellenismus

Model America

Americanisation of the Economy

"Amerika" in Deutschland und Frankreich

US-Film in Europa

Model Classical Antiquity

Idealisierung der Urkirche

Kongregation von Saint-Maur

Model Hercules*

Rezeption der griechisch-römischen Medizin

Galen-Rezeption Melanchthons

Medizinische Humanisten

Roman Law and Reception

Translatio Imperii im Moskauer Russland

Model Europe

Concepts of Europe

Europa-Netzwerke der Zwischenkriegszeit

Homo Europaeus

Model Germania

Model Italy

Modernization

Russification / Sovietization

Economy and Agriculture

Wirtschaft und Landwirtschaft

Kultur und Gesellschaft

Culture and Society

"Spanish Century"

"Leyenda Negra"

The "West" as Enemy

Versailles Model

Enlightenment Philosophy

Französische Musik

Lingua Franca und Verkehrssprachen

Lingua Franca

Moral Weeklies (Periodical Essays)

- de Deutsch German

- en Englisch English

The early eighteenth century witnessed the birth in England of the "Spectators", a journalistic and literary genre that developed in the wake of the Glorious Revolution (1688). Beginning in 1709 these newspapers and their fictitious narrators would influence the entire European continent. In the Anglophone world the "Spectators" were also called "periodical essays", whereas in German-speaking lands they were known as "Moralische Wochenschriften" or, in a re-translation into English, as "Moral Weeklies". These periodicals constituted a new public medium, aimed especially at a bourgeois audience and responsible for a brisk discursive transfer. They thus not only added further dimensions to public communication, but they also contributed decisively to the development of modern narrative forms.

Preconditions for the Periodical Essay

The Spectator genre owed its development in England to the political and cultural events of the late 17th century. In the reigns of William III of Orange (1650–1702) and his successor Queen Anne Stuart (1665–1714) , new forms of democratic sensibility emerged that diverged from absolutist models and laid the foundation for the genesis and promotion of public communication. England had long since set its own course, one that was critically opposed to the traditional social forms of the European continent . Work in Parliament laid the foundation for English law, and new public structures arose; both processes were closely connected to the development of medial communication. The reigning moral code became that of the sober and pragmatic Protestant worldview, which underlay the national stereotype of the "practical Englishman".

The philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) , the founder of modern epistemology and the critique of knowledge, gladly returned to England after William ascended the throne (1688). With his works An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) and Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) he contributed decisively to both the reflection on the process of social renewal and the communication of knowledge in the modern sense. The time was slowly arriving for the successful English model to be exported to the European continent.

Philosophy was joined by freedom of the press, introduced in 1695, in promoting the notion of fairness and tolerance. This brought with it a trend towards liberalization that strengthened the middle class's sense of itself, giving rise to an appreciable feeling that change was in the air. At that time the gentry set the tone in English society, and its ideal of the gentleman served as the model for the emerging bourgeoisie, especially in the capital city of London . Critical observers, however, found fault with this code of behaviour, claiming that it was otiose, morally nonchalant and constituted a playing field for the increasing depravity of culture. At the turn of the century, numerous cries were heard for the comprehensive reform of morals and behavioural patterns. 1

The literary roots of the periodical essays can be found partly in French culture, which at the time still served as the model for wide social circles in Europe . Nicolas Boileau's (1636–1711) writings provided access to discussions about the reception of the hegemonic textual forms of Greek and Roman antiquity. In the foreground of this transfer stood literary forms like satire, the character portraits of Jean de la Bruyère (1645–1696) , and the dramas of Pierre Corneille (1606–1684) . Michel de Montaigne's (1533–1592) Essais (1580) also influenced the development of the Spectators , although the latter departed from the authentic first-person narrator of the French model and vanish behind the mask of a fictional narrator.

Cultural forerunners of the periodical essay can also be found in the literary forms of the Italian classics and the Spanish Golden Age, the Siglo de Oro (16th/17th century), which had had an early influence on English literature. One thinks, among the many possible examples, of Giovanni Boccaccio's (1313–1375) novellas, of the narrative forms of the Spanish picaresque novel, of the romance and its transcendence through Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra's (1547–1616) El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605/1615), of the dream narratives of a Francisco Quevedo (1580–1645) , and of the masque, which spread to Spain by way of Italian culture.

"Spectatorial" Prototypes

The tatler (1709–1711).

This was the background for the journalistic enterprise of the Whig Richard Steele, who launched The Tatler. By Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq. on 12 April 1709. 2 After the first issues had appeared, Steele was joined by his longtime friend and confidant Joseph Addison. The paper ran on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays, the days on which mail was delivered in the countryside. The rhythm suggested by the term "weekly" had not yet been established. It would first come into use in continental imitations, especially in connection with German papers. Thus a genre was created that in the course of the century would spread all over Europe in hundreds of different periodicals. The distinctive feature of this model lay in the fact that it did not just engage in the didactic moralism typical of Anglican devotional literature but rather presented moral considerations in a new, playful and informal way.

In his first "Spectatorial" enterprise Steele used the persona of Isaac Bickerstaff, a fictional character originally contrived by Jonathan Swift. This imaginary figure was well known in England and especially in London, and thus this first observer of contemporary society was in a certain sense "trustworthy." Steele created a fictional frame for Bickerstaff and used this perspective to observe the mercantile society of London. Many contemporaries might have guessed that Steele was behind the mask, but only in the final issue of the newspaper did the true author identify himself. 3 With issue 271 on 2 January 1711, the author brought his Tatler , in which Addison had come to play an increasingly important role, to an end. Nevertheless, in a letter to the editor Bickerstaff was prompted to continue his intellectual game. A sequel to the project was thus to be expected.

The Spectator (1711–1714)

![The Spectator 1711 IMG [Joseph Addison / Richard Steele]: The Spectator (1711–1714), Nr. vom 7. September 1711. Bildquelle: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spectator.jpg.](https://www.ieg-ego.eu/./illustrationen/moralisierende-wochenschriften-bilderordner/the-spectator-1711-img/@@images/image/thumb)

The Guardian (1713)

The third and last journalistic prototype was the short-lived magazine The Guardian , which first appeared on 12 March 1713 and reached 175 issues. 5 The narrator was now Nestor Ironside, a retired tutor living in the circle of his host family, whose patriarch had died. The septuagenarian Ironside possessed the necessary distance to the individual members of the family to portray their moral character and to interpret their conversations accordingly. Here, too, piety and virtue played a central role, as did the rational upbringing of youth and the observation of private discourse.

Characteristics of the Genre

Periodical publication and reissues.

The periodical essays were characterized by their entertaining portrayal of moralizing contents. They were published in regular intervals, and after a certain period of time the folios were often collected and reissued in book form. Depending on the journal, they could appear in several editions over decades, sometimes even being printed in different cities. Thanks to their particular entertaining streak, these volumes tended to enjoy high sales. The economic factor could not be separated from "Spectatorial" enterprises. Thus it often happened that the economic success was reflected upon in the writings themselves or that reader reception was explicitly measured.

The valorisation of public communication brought with it the vitality that was essential to early liberal societies. Since reader expectations were always maintained, the regularly appearing issues became an event unto themselves and facilitated a kind of communication that was closely coupled (in Luhmann's terms) with the differentiation of functional social systems. This dynamic was all the more idiosyncratic, as the weeklies did not deal with issues of everyday politics but rather with life's basic moral-philosophical questions (and thus the same themes tended to recur). Repetition was one of the central traits of the papers, whose articles were self-contained and – with very few exceptions – could be exchanged with one another at will. The articles' timelessness is the reason that the papers could appear years later in anthologies and continue to be of interest to the inquiring readers of the evolving middle class.

Translations and Adaptations

The moralizing journalism pioneered by Steele was quick to win an audience and to give rise to adaptive imitations and translations. This type of reception occurred as early as regarding the Tatler itself. Soon after the journal's appearance several related titles hit the market. 6 Thus on 8 July 1709 – i.e. about three months later – a competing enterprise appeared in the dress of a cooperative union: The Female Tatler. By Mrs. Crackenthorpe, a Lady that knows every thing . The fictional editor Mrs. Crackenthorpe claimed to be a colleague of Bickerstaff and to operate her periodical as a complement to his. The true author of this paper, which ended on 31 March 1710 after 115 issues, has still not been identified. 7

Female Audience

As this example shows, the periodical essays and the later weeklies displayed another core trait: they were often aimed at a female audience, such that the first women's magazines on a larger scale can be found in this genre. 8 Gender roles were critically called into question, and problems dealing with the reigning order of the sexes were discussed. The impact could be more or less appreciable depending on the cultural context in which the journal appeared, such as in Italy or Spain. Female voices were often a disguise for male authors, some of whom were Catholic priests. This was the case in the weekly La Pensadora Gaditana (1763/1764) 9 which appeared under the pseudonym Beatriz Cienfuegos.

The Role of Fictional Authors and Editors

One of the most important traits of the genre was the introduction of fictional authors and editors. Relying on a masked, anonymous authority like Bickerstaff, Spectator or Ironside allowed the periodical essays to achieve a high degree of aesthetic appeal and to communicate moral arguments and observations. The observers were able to capture and comment on all the communication in their environment unnoticed and could therefore construct a moral code that accommodated bourgeois interests. Such characters, finally, provided the audience with innovative possibilities for self-identification. A game was developed with the readers, who felt that their own lifestyle was continually being addressed and that they were themselves being challenged. Many weeklies would later adopt this method, an excellent example of which can be seen in the introduction to the Spectator :

I have observed, that a Reader seldom peruses a Book with Pleasure 'till he knows whether the Writer of it be a black or a fair Man, of a mild or cholerick Disposition, Married or a Batchelor, with other Particulars of the like nature, that conduce very much to the right Understanding of an Author. To gratify this Curiosity, which is so natural to a Reader… 10

This clearly shows the significance of the communicative process between author and reader, in which the author's hidden identity increases the work's playful character. A complex interplay is developed between various types of observers, with opposite types mirroring and adroitly paired with each other, thus creating a reflexive composition of viewpoints. In this way, the anonymity and the mask produced a disjunction in the interaction between writer and reader, as it made it impossible for either one to ascribe anything to any specific individual. The advantage to this novel means of communicating information lay in the way it reduced prejudice to a minimum in the exchange of opinions. For it deactivated the influence that a specific author's name, age, appearance, and so forth might otherwise have on the reader. A similar technique would make its appearance in literature somewhat later in the works of Laurence Sterne (1713–1768) and Denis Diderot (1713–1748) . On the one hand this game between author and reader became typical of the communicative processes being developed in London at the time. On the other it served the transmission of moral teachings in the traditional sense.

These methods made their way into numerous translations and imitations in other European cultural spheres. As linguistic studies of some individual journals have already described in more detail, the fictional first-person narrator of the weeklies was given great importance everywhere. 11 At the same time, the personal narrative style of the disguised authors, which was based on the communicative form of the written letter and carried it forward in a new dress, also became evident. An example of the application of this style in the German context is provided by the introduction to the weekly Hypochondrist (Hypochondriac, 1762). Here the fictional narrator Zaccharias Jernstrupp sketches his hypochondriac symptoms as follows:

Ich würde vielleicht nicht einmal auf den Einfall gekommen seyn, ein Wochenblatt zu schreiben, wenn ich dieser Krankheit entbehren müsste, dass sie mir zu einem schönen Titel für meine Blätter verholfen hat. Ich habe nun alles, was zu einem wöchentlichen Autor erfordert wird. Ich bin eigensinnig, mürrisch, ein bischen eitel, eine Art von Philosoph… 12

The Staging of Sociability

The introduction of a fictional author was not the only prominent innovation of the weeklies; another was the involvement of readers in the genesis of the journal. It was common for many weeklies to invite readers to participate in discussions via letters to the editor and thus to transmit their texts to the editor or fictional author. This staging of sociability on the model of pragmatic communication strategies was probably one of the factors that contributed to the great success of such publications in the English metropolis.

The question just how much these letters, which were revised by the "fictional" editor, can still be ascribed to their "real", original authors provides a further difficulty for the reception and interpretation of such texts. Whether the letters were made up from the very beginning in order to get the communication process going, or whether they reflect what readers actually wrote, will remain a mystery for many weeklies and is a part of the hybridization that characterizes the genre. The tie to the readers is also strengthened by the original titles of the journals, which generally described their respective fictional observers. The broad spectrum spanned from the Matrone ("Matron" – 1728–1729), 13 the Braut ("Bride" – 1740) 14 and the Jüngling ("Youth" – 1747), 15 to the Vernünfftler ("Rationalist" – 1713/1714) 16 and the Patriot ("Patriot" – 1724–1726), 17 down to the Einsiedler ("Hermit" – 1740/1741), 18 the Duende (" Goblin" – 1787/1788), 19 the Misanthrope (1711/1712) 20 and even the Scannabue ("Oxen Butcher" – 1763–1765), 21 to name only a few. French scholarship has examined the entire collection of titles with the aim of elaborating a functional classification valid for all the journals. This research found five functional categories for the genre: réflexion, regard, bavardage, folie and collecte . 22

Literary Forms

Another innovation is the essayistic, narrative treatment of everyday life. The "Tatler", like his much more famous successor, the "Spectator", acts as a reflection of the social discourse in which he participates as well, integrating everything he sees and hears into his texts. It is not only his self-portrayal that is important but also the way he depicts others together with the accompanying stories, conversations, and reports. The poetics of Horace (65–8 B.C.) with its dictum "prodesse et delectare" is the inspiration here. Many other elements of the periodical essays are likewise influenced by classical literature. Letters, dream narratives and allegories, fables and satirical portrayals, all relying on Greek and Roman models, shaped the perception of the genre. Exemplary quotations appear as mottos throughout the texts, aphoristically formulating the points they communicate.

The Netherlands, Portal to the Continent

It did not take long for the periodical essays to make their way to continental Europe. The most important point of transfer for the genre was the Protestant Netherlands , especially Amsterdam and The Hague . A large group of emigrants moved north and settled in the area after the Edict of Nantes had been repealed (1685), contributing decisively to book production in French. English was also more used in this cultural context than in other parts of the continent.

Justus van Effen, the author of the Misanthrope , was born in Utrecht and played an important role in bringing English literature to Holland. He is known above all for his translations of the novel Robinson Crusoe (Daniel Defoe, 1719) and of texts by Jonathan Swift and Bernard de Mandeville (1670–1733) . His Misanthrope was published every Monday in The Hague. In a liberal adaptation of its English model, it successfully discussed moral questions of contemporary society. That two further editions 25 followed – in 1726 and 1742 – testifies to the auspicious reception of the enterprise.

![Hollandsche Spectator IMG [Justus van Effen]: Hollandsche Spectator (1731−1735). Bildquelle: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:De_Hollandsche_Spectator.jpg.](https://www.ieg-ego.eu/./illustrationen/moralisierende-wochenschriften-bilderordner/hollandsche-spectator-img/@@images/image/thumb)

Justus van Effen was the essential link in the transfer and further development of the genre on the continent. He initiated a communication process through which the texts, in the form of adaptations and translations, went from England to Holland and partly even to France . In the years following, the journals were exported to the rest of Europe via francophone connections. Van Effen was quick to recognize the journalistic and literary potential of the English prototypes and to provide for their brisk adaptation to other cultural contexts. He took clever advantage of the resulting dynamic for his own enterprise, and he might even have managed to have an indirect impact on the ongoing development of the Spectator . Likewise he exercised a dialogic influence on later French productions.

His impact can be measured in yet another way. On the one hand, he – like many subsequent European authors, especially in Romance areas – established translations of original texts as the authoritative means for replicating the English prototype. This can be seen in his treatment of the Guardian . On the other hand, from the very beginning he also promoted liberal imitation and thus the adaptation of the canon and relevant moralizing issues to suit specific national and regional characteristics. Typical features of his work were multilingualism, the promotion of cultural transposition, and his many insights into the various processes of national development, which especially helped him to contribute decisively to national adaptations of the prototype – for example in the Hollandsche Spectator . His rationalistic arguments in the interest of bettering the morals of a nation became models for many contemporaries.

Furthermore, he was especially dedicated to the weekly rhythm of publication, such that he became associated not only with the Spectator genre but also with that of the moral weeklies in general. It is thus no wonder, for example, that the first such Spanish journal, El Duende especulativo (1761), 30 was based no longer on the Tatler or Spectator of Steele and Addison but rather on Van Effen's Misanthrope .

The circulation of the English prototypes was exaggerated on the continent from the get-go, the idea clearly being to underline the economic attractiveness of this journalistic enterprise. In one of the first letters accompanying the Misanthrope , the Dutch bookdealer responsible for its publication claimed that 12,000 to 15,000 copies of the Tatler were printed daily – a technical impossibility for a small press. 31 In the foreword to the Spanish Filósofo a la moda ("The Fashionable Philosopher"), the circulation of the first issues was, in imitation of its Dutch model, even placed at 20,000. 32 All in all, the most important weeklies in Europe, depending on region, probably had an average circulation of between a few hundred (Italy, Spain, etc.) and two or three thousand (England, Germany , France, etc.) copies.

The Emergence of a European Network

Further diffusion of the journals in Europe ensued rapidly, although the respective cultural milieus reacted differently. The journals' clearly formulated Protestant values determined their reception, and the genre initially enjoyed greater success in the North than in the South. Urban centres, in which bourgeois values were already more strongly developed, were more favourable than rural areas.

Although the weeklies blossomed in northern Lutheran lands, a few decades were necessary for the genre to develop in the Catholic South. In Romance areas, the Holland-based Spectateur was probably the most influential model.

Apart from a free, abridged translation of the Spectateur that appeared in Venice as early as 1728 under the title Il Filosofo alla Moda ("The Fashionable Philosopher"), 40 the genre did not make its way to Italy until the second half of the century. In 1752 La Spettatrice ("The Female Spectator") 41 appeared; it was followed closely by the Gazzetta Veneta ("Venetian Gazette" –1760/1761), 42 the Osservatore Veneto ("Venetian Observer" – 1761/1762) 43 (later Gli Osservatori Veneti ["The Venetian Observers"]), La Frusta Letteraria di Aristarco Scannabue ("The Literary Whip of Aristarcus the Oxen Butcher" – 1763–1765) and Il Caffè ("The Café" – 1764–1766). 44

![El Pensador IMG [José Clavijo y Fajardo]: El Pensador (1762−1767). Bildquelle: Memoria digital de Canarias, online: http://mdc.ulpgc.es/u?/MDC,70506.](https://www.ieg-ego.eu/./illustrationen/moralisierende-wochenschriften-bilderordner/el-pensador-img/@@images/image/thumb)

Characteristics of the Genre's Transnational Transfer

In its transfer from the English context via Dutch-French mediation to other cultural milieus, the weekly genre took on national characteristics that could also show hints of local colour. Although the journals only seldom discussed events of the day, they were nevertheless integrated in narrative forms and modes of representing sociality that varied from nation to nation. It was common for internal matters of English politics, literature and culture to be left out of continental translations and adaptations or to be replaced or supplemented with issues relevant to the target culture. The fictional author or editor was usually given a local hue or was at least open to discussing cultural issues from his own milieu. Similar strategies were employed when French-language weeklies were adapted by authors of a different provenance. In this way French, German, Italian and Spanish authors enriched their writings with local characteristics and thus contributed to the development of a transnational network.

Journalistic and literary debates were often ignited by the question whether a given weekly was shaped by local cultural conditions or rather an import from the English, Dutch, French or German cultural sphere. A related question was to what extent Protestant ethics were being implanted in Catholic culture or, similarly, how much the liberal tendencies of a given weekly were responsible for bringing modernity to a given cultural milieu. It was, however, also possible for the defenders of a specific tradition to use the weekly as a means of combating the genre itself and the liberalisation it conveyed, as was the purpose behind the Spanish El Escritor sin título ("The Untitled Author", 1763). 47 In such cases, the author's true intention was usually kept hidden behind the weekly's satirical tone, and conflicts of interpretation were still highly likely.

The End of the Periodical Essays

From the very beginning the periodical essays were destined to be ephemeral. They faded more quickly in Protestant areas, giving way to the novel, whereas in the Catholic South, for example in cities like Vienna and Madrid, their moralizing conversational tone helped some to persevere into the nineteenth century. They also stayed alive in the form of supplements to informational bulletins like Justus Möser's (1720–1794) Wöchentliche Osnabrückische Intelligenzblätter ("Weekly Osnabrück Bulletins"). Their traces can also be found in many narrative works. Wolfgang Martens (1924–2000) , a scholar of German weeklies, has described their end quite aptly:

Die Wochenschrift alten Schlages, die die Verfasserfiktion beibehält und zugleich nach wie vor Vernunft und Tugend zum Zwecke der bürgerlichen Glückseligkeit zu fördern bestrebt ist, ist nach 1770 in den nördlichen Breiten selten geworden. Der Roman der Hermes, La Roche und Miller macht ihr das Publikum abspenstig. Sturm und Drang und der Hochsubjektivismus der Empfindsamkeit sind für die Nachfahren der Gattung kein gedeihliches Klima mehr. Das stärkere politische Interesse, das sich seit den 70er Jahren in Deutschland bemerkbar macht, ist ihr fremd, die Aufregungen der Französischen Revolution vollends verschlagen ihr die Rede und der Geist der Romantik ist ihrer bürgerlich-lehrhaften Haltung gänzlich fern. Stoffe, Themen, Motive, erbaulicher Sinn und redliche Absichten leben fort im bürgerlichen Unterhaltungsblatt des 19. Jahrhunderts …. 48

Klaus-Dieter Ertler