Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

DSM-5 Clinical Cases

- Rachel A. Davis , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

DSM-5 Clinical Cases makes the rather overwhelming DSM-5 much more accessible to mental health clinicians by using clinical examples—the way many clinicians learn best—to illustrate the changes in diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5. More than 100 authors contributed to the 103 case vignettes and discussions in this book. Each case is concise but not oversimplified. The cases range from straightforward and typical to complicated and unusual, providing a nice repertoire of clinical material. The cases are realistic in that many portray scenarios that are complicated by confounding factors or in which not all information needed to make a diagnosis is available. The authors are candid in their discussions of difficulties arriving at the correct diagnoses, and they acknowledge the limitations of DSM-5 when appropriate.

The book is conveniently organized in a manner similar to DSM-5. The 19 chapters in DSM-5 Clinical Cases correspond to the first 19 chapters in section 2 of DSM-5. As in DSM-5, DSM-5 Clinical Cases begins with diagnoses that tend to manifest earlier in life and advances to diagnoses that usually occur later in life. Each chapter begins with a discussion of changes from DSM-IV. These changes are further explored in the cases that follow.

Each case vignette is titled with the presenting problem. The cases are formatted similarly throughout and include history of present illness, collateral information, past psychiatric history, social history, examination, any laboratory findings, any neurocognitive testing, and family history. This is followed by the diagnosis or diagnoses and the case discussion. In the discussions, the authors highlight the key symptoms relevant to DSM-5 criteria. They explore the differential diagnosis and explain their rational for arriving at their selected diagnoses versus others they considered as well. In addition, they discuss complicating factors that make the diagnoses less clear and often mention what additional information they would like to have. Each case is followed by a list of suggested readings.

As an example, case 6.1 is titled Depression. This case describes a 52-year-old man, “Mr. King,” presenting with the chief complaint of depressive symptoms for years, with minimal response to medication trials. The case goes on to describe that Mr. King had many anxieties with related compulsions. For example, he worried about contracting diseases such as HIV and would wash his hands repeatedly with bleach. He was able to function at work as a janitor by using gloves but otherwise lived a mostly isolative life. Examination was positive for a strong odor of bleach, an anxious, constricted affect, and insight that his fears and behaviors were “kinda crazy.” No laboratory findings or neurocognitive testing is mentioned.

The diagnoses given for this case are “OCD, with good or fair insight,” and “major depressive disorder.” The discussants acknowledge that evaluation for OCD can be difficult because most patients are not so forthcoming with their symptoms. DSM-5 definitions of obsessions and compulsions are reviewed, and the changes to the description of obsessions are highlighted: the term urge is used instead of impulse so as to minimize confusion with impulse-control disorders; the term unwanted instead of inappropriate is used; and obsessions are noted to generally (rather than always) cause marked anxiety or distress to reflect the research that not all obsessions result in marked anxiety or distress. The authors review the remaining DSM-5 criteria, that OCD symptoms must cause distress or impairment and must not be attributable to a substance use disorder, a medical condition, or another mental disorder. They discuss the two specifiers: degree of insight and current or past history of a tic disorder. They briefly explore the differential diagnosis, noting the importance of considering anxiety disorders and distinguishing the obsessions of OCD from the ruminations of major depressive disorder. They also point out the importance of looking for comorbid diagnoses, for example, body dysmorphic disorder and hoarding disorder.

This brief case, presented and discussed in less than three pages, leaves the reader with an overall understanding of the diagnostic criteria for OCD, as well as a good sense of the changes in DSM-5.

DSM-5 Clinical Cases is easy to read, interesting, and clinically relevant. It will improve the reader’s ability to apply the DSM-5 diagnostic classification system to real-life practice and highlights many nuances to DSM-5 that one might otherwise miss. This book will serve as a valuable supplementary manual for clinicians across many different stages and settings of practice. It may well be a more practical and efficient way to learn the DSM changes than the DSM-5 itself.

The author reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

- Cited by None

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

Cover Focus | September 2022

Challenge Case Report: Tic Disorder in an Adult

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments improve tic frequency and severity., danielle larson, md, clinical presentation.

JB is age 35, right-handed, with a history of generalized anxiety disorder, and presenting to clinic for evaluation and management of unusual movements that began in adolescence. JB also makes brief vocalizations including throat clearing and grunting. The movements and vocalizations have become more frequent and disabling, evolving from rare, mild, and manageable to preventing use of a computer or holding an effective business meeting. There is an anticipatory sensation and urge to perform the movements beforehand followed by relief after completing the movements. JB can suppress these tics temporarily, but after several seconds there is a building urge to perform them.

Medical and Family History

These unusual movements began occurring when JB was age 6 as sudden, brief, jerking movements of the neck and brief shoulder shrugs. In adolescence, JB was diagnosed with a tic disorder by a neurologist and told that the tics would resolve on their own with time; no therapeutics were tried.

JB’s generalized anxiety began in adolescence and is currently poorly controlled owing to life stressors. JB takes 0.5 mg clonazepam tablets, as needed, up to 3 times daily for anxiety; rarely drinks alcohol; and reports being a nonsmoker who uses no other drugs.

Family history is notable for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)-like behaviors in JB’s father and anxiety in JB’s brother.

Diagnostic Evaluations

JB’s neurologic exam is remarkable for frequent brief shoulder shrugs, jerky head turns to the right, and throat clearing. Findings of the cranial nerve, motor, sensory, cerebellar, and reflex examinations are unremarkable.

Complete blood chemistry (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B 12 levels were all within normal limits. A brain CT was unremarkable. Neuropsychologic testing showed relatively mild impairments in perceptual reasoning with mild inattentiveness and mild retrieval-based difficulty in verbal memory.

Challenge Questions

1. Which of the following features from JB’s history is NOT unique to tic phenomenology?

A. Premonitory urge preceding the movement

B. Temporary suppressibility of the movement

C. Quick, jerky movement

D. Transitory relief after performing the movement

Click here for the answer

C, Quick, jerky movements are NOT unique to tic phenomenology and may be seen in functional neurologic disorders, neuromuscular disorders, seizures, and other neurologic conditions. In contrast to those disorders, however, tics are characterized by premonitory urges, temporary suppressibility, and transitory relief after movements occur. 1

2. Which of the following is NOT required for the diagnosis of classic Tourette syndrome?

A. Onset of tics before age 18

B. Male sex

C. Presence of both motor and phonic tics

D. Persistence of tics beyond the period of 1 year

B, Male sex/gender is NOT required for the diagnosis of classic Tourette syndrome (TS). Although TS is reported to be 3 to 4 times more common in boys than girls, it has also been reported that this is attenuated in adulthood. 2 Diagnostic criteria for TS require the presence of at least 1 motor and 1 phonic tic for at least 1 year with onset before age 18 years. 3

3.Which of the following medications is NOT a recommended pharmacologic treatment for tics?

A. Clonidine

B. Topiramate

C. Levetiracetam

D. Olanzapine

C, Levetiracetam is an antiseizure medication (ASM) that is NOT a recommended pharmacologic treatment for tic disorders. The ASM, topiramate, has shown efficacy in 1 randomized controlled clinical trial. 4 Clonidine and guanfacine are alpha-2-agonists that have been shown superior to placebo for tic reduction in multiple clinical trials and are first-line treatment for tics. 5-7

Tic Disorder in an Adult

Diagnosis and Treatment

JB’s semivoluntary movements, associated with preceding urges, temporary relief, and brief suppressibility, are consistent with tics. Considering tic onset before age 18 years, the presence of multiple motor and phonic tics, tic persistence beyond 1 year, and the lack of any other possible etiology for his symptoms, JB was diagnosed with Tourette syndrome (TS). Because of the moderate severity of the tics and interference with daily life, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments were recommended. Guanfacine was prescribed and a referral made for comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics (CBIT)/habit reversal training (HRT) for tics. JB was also referred to psychiatry for further evaluation and management of anxiety that has recently flared and contributed to tic severity.

At a 4-month follow-up visit, JB reported that tic severity and frequency had improved by roughly 50% with the initiation of low-dose guanfacine and completion of 4 of 8 scheduled CBIT/HRT sessions. JB had also established care with a psychiatrist, who has gradually discontinued clonazepam, and recently started working with a psychotherapist for anxiety. In general, JB was happy with the improvement in tics and felt their function at work was improved.

Tics are semivoluntary, purposeless movements that are typically rapid, arrhythmic, and stereotyped. The movements are classically preceded by a premonitory sensation or urge and associated with relief after the tic is performed. 1 Tics are commonly temporarily suppressible, but this is often associated with a building urge to perform the tic.

TS is a neurodevelopmental disorder of unclear etiology characterized by the presence of at least 1 motor and 1 phonic tic with onset before age 18 years that lasts over 1 year, according to diagnostic criteria. 2 TS affects an estimated 0.3% to 1% of the population and is more common in men but occurs in all sexes/genders. 2 Onset of tics is typically between age 4 and 8 years. TS is often familial; first-degree relatives of individuals with tic disorders have a significantly higher risk of TS or other chronic tic disorders. 8,9

In TS, tic frequency and severity tend to wax and wane over the years, with roughly 20% of TS cases persisting into adulthood. 10 Individuals have their own unique set of tics; different tics may develop or abate over the lifespan.

Comorbid attention deficit disorder (40%-60%) and OCD (20%-40%) are strongly associated with TS, occurring at rates more than 10 times higher than in the general population. 11-14 Anxiety (50%-70%) and depression (50%-60%) are frequently present as well. 13

Clinically, tic severity and frequency can be assessed through history taking and examination. Tics can negatively affect an individual’s quality of life by causing social or emotional distress, physical discomfort, or impaired function (in work, driving, sleeping, or other activities of daily living). When tics are causing these impairments, treatment should be initiated.

The initial intervention recommended is CBIT, specifically HRT, which is typically an 8-session treatment with a trained provider based on tic awareness, development of competing response incompatible with tic execution, and relaxation training. 10 Efficacy in reducing tic severity and improving quality of life has been established in randomized control trials (RCTs). 15,16

Pharmacologic therapy should be considered when behavioral therapy is not an option (owing to insurance, limited provider availability, and other barriers to access), has been completed but there is residual tic burden, or tics are severe or need to be addressed quickly. On average, medications reduce tic symptoms by 25% to 50%. 17 There are 3 categories of medications for tics as follows.

Nondopaminergic Agents. The nondopaminergic alpha-2-agonists clonidine and guanfacine are first-line treatments. Clonidine has been used to treat TS for over 30 years with efficacy compared with placebo demonstrated in several RCTs. 5,6 Common side effects include sedation, bradycardia, hypotension, and dry mouth. Guanfacine has a lower risk of sedation and hypotension compared with clonidine and has also been shown to be superior to placebo in RCTs. 5,7 Topiramate, an antiseizure medication with GABAergic properties, has also been shown to effectively reduce tics in 1 clinical RCT. 4

Dopamine Receptor Blockers . As classic dopamine receptor blockers, multiple typical and atypical antipsychotics are approved for tic treatment. Although RCT results support efficacy in tic reduction, these agents are typically reserved for severe or refractory tics owing to undesirable side-effect profiles. Antipsychotics carry the risk of tardive dyskinesia (TD), which can compound the distress and treatment complexity for people with TS.

Dopamine-Modulating Vesicular Monoamine Transporter-2 (VMAT-2) Inhibitors. The VMAT-2 inhibitors offer an alternative to antipsychotics with a better side effect profile and no risk of TD. Although the classic VMAT-2 inhibitor tetrabenazine and newer-generation deutetrabenazine and valbenazine have open-label data showing tic treatment efficacy, RCT results have not corroborated these findings and all are used on an “off-label” basis for tic treatment. 18,19

Importantly, in addition to directly addressing tic severity and frequency with CBIT and/or medications, an individual’s co-morbidities (eg, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit disorder, anxiety, or depression) should be adequately addressed (with psychiatry referral and pharmacotherapy as needed) to optimize tic improvement.

1. Martino D, Madhusudan N, Zis P, Cavanna AE. An introduction to the clinical phenomenology of Tourette syndrome. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;112:1-33.

2. Lichter DG, Finnegan SG. Influence of gender on Tourette syndrome beyond adolescence. Eur Psychiatry . 2015;30(2):334-340.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Neurodevelopmental disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:31-86..

4. Jankovic J, Jimenez-Shahed J, Brown LW. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of topiramate in the treatment of Tourette syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . 2010;81(1):70-73.

5. Quezada J, Coffman K. Current approaches and new developments in the pharmacological management of Tourette Syndrome. CNS Drugs . 2018;32(1):33-45.

6. Du Y, Li H, Vance A, et al. Randomized double-blind multicentre placebo-controlled clinical trial of the clonidine adhesive patch for the treatment of tic disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiatry . 2008;42(9):807-813.

7. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1067-1074.

8. Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol . 2012;47(2):77–90.

9. Mataix-Cols, D, Isomura K, Pérez-Vigil A. Familial risks of Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. A population-based cohort study.J AMA Psychiatry . 2015;72(8):787-793.

10. Hassan N, Cavanna AE. The prognosis of Tourette syndrome: implications for clinical practice. Funct Neurol . 2012;27(1):23-27.

11. Leckman JF, Walker DE, Goodman WK, Pauls DL, Cohen DJ. “Just right” perceptions associated with compulsive behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiatry . 1994;151(5):675-680.

12. Coffey BJ, Biederman J, Smoller JW, et al. Anxiety disorders and tic severity in juveniles with Tourette’s disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2000;39(5):562-568.

13. Coffey BJ, Miguel EC, Biederman J, et al. Tourette’s disorder with and without obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: are they different?. J Nerv Ment Dis . 1998;186(4):201-206.

14. Comings DE, Comings BG. A controlled study of Tourette syndrome. I. Attention-deficit disorder, learning disorders, and school problems. Am J Hum Genet . 1987;41(5):701-741.

15. Van de Griendt JM, Verdellen CW, van Dijk MK, Verbraak MJ. Behavioural treatment of tics: habit reversal and exposure with response prevention. Neurosci Biobehav Rev . 2013;37(6):1172-1177.

16. Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA . 2010;303(19):1929-1937.

17. Roessner V, Schoenefeld K, Buse J, Bender S, Ehrlich S, Münchau A. Pharmacological treatment of tic disorders and Tourette syndrome. Neuropharmacology . 2013;68:143-149.

18. Jankovic J, Glaze DG, Frost JD Jr. Effect of tetrabenazine on tics and sleep of Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Neurology . 1984;34(5):688-692.

19. Jankovic J, Jimenez-Shahed J, Budman C, et al. Deutetrabenazine in tics associated with Tourette syndrome. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (NY) . 2016;6:422

DL reports no disclosures

Assistant Professor of Neurology Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, IL

Progress in Movement Disorders

Erin Furr Stimming, MD, FAAN; and Victor W. Sung, MD

Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes

Steve C. Han, MD; and Steven J. Frucht, MD

This Month's Issue

Anne Møller Witt, MD; Louise Sloth Kodal, MD; and Tina Dysgaard, MedScD

Samantha Kropp, MD; and Joe Mendez, MD

Matthew C. Varon, MD; and Mazen M. Dimachkie, MD

Related Articles

Swati Pradeep, DO; and Jaime M. Hatcher-Martin, MD, PhD

Richa Tripathi, MD, MS; J. Lucas McKay, PhD, MSCR; and Christine D. Esper, MD, FAAN

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Related News

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Spring 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 2 Autism Across the Lifespan CURRENT ISSUE pp.147-262

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 1 Reproductive Psychiatry: Postpartum Depression is Only the Tip of the Iceberg pp.1-142

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Ethics Commentary: Ethical Issues in Bipolar Disorder: Three Case Studies

- Laura Weiss Roberts , M.D., M.A.

Search for more papers by this author

Sound ethical decision making is essential to astute and compassionate clinical care. Wise practitioners readily identify and reflect on the ethical aspects of their work. They engage, often intuitively and without much fuss, in careful habits—in maintaining therapeutic boundaries, in seeking consultation from experts when caring for difficult or especially complex patients, in safeguarding against danger in high-risk situations, and in endeavoring to understand more about mental illnesses and their expression in the lives of patients of all ages, in all places, and from all walks of life. These habits of thought and behavior are signs of professionalism and help ensure ethical rigor in clinical practice.

Psychiatry is a specialty of medicine that, by its nature, touches on big moral questions. The conditions we treat often threaten the qualities that define human beings as individual, as autonomous, as responsible, as developing, and as fulfilled. The conditions we treat often are characterized by great suffering, disability, and stigma, and yet individuals with these conditions demonstrate such tremendous adaptation and strength as well. If all work by physicians is ethically important, then our work is especially so.

As a service to FOCUS readers, in this column we endeavor to provide ethics commentary on topics in clinical psychiatry. We also proffer clinical ethics questions and expert answers in order to sharpen readers’ decision-making skills and advance astute and compassionate clinical care in our field.

Ms. Genera is a 36-year-old woman with bipolar II disorder, first diagnosed in college, who is brought to the psychiatric emergency room by her boyfriend of 5 years. He is hoping that she will be admitted to the hospital “before she goes all-the-way manic.” He reports that she “almost lost her job last time!”

Over the past 6 weeks, he reports that Ms. Genera has needed “less and less” sleep, has been cleaning the house “around the clock,” and has “wanted a lot of sex even though she is really pissed off all of the time.” The patient states that she is “fine, more than fine, in fact.” She says that she has not been able to sleep “because of the neighbors.” She says that they talk loudly at night and that she and the baby will “fix that” because babies are “noisy at night too!” Her boyfriend is confused by this comment, saying that they have no children—“I don’t know why she says stuff like that. I know it’s the manic-depressive, but it is pretty crazy.” Ms. Genera states that her thoughts are like “O’Hare airport!” and that she has “no problem keeping up” with the different “planes coming and going.” The patient says that she stopped taking all of her medications about 3 months ago—“That lithium is really hard on me. I don’t like to take it unless I have to.” She has no history of alcohol or other substance use, no history of suicide attempts, and no history of dangerousness toward others.

On mental status exam, Ms. Genera is a neatly dressed, mildly overweight woman who appears slightly older than her stated age. She is cooperative with the clinical interview and asks that her boyfriend step out of the room when she is talking with the doctor. She is speaking quickly and loudly, with appropriate affect. Her thought form is linear. She denies hallucinations and reports no thoughts of self-harm.

Ms. Genera says that she has “Bipolar II, not Bipolar I—I don’t have it that bad. Never have. Yessirree, I am really good right now.” She does not want to be admitted to the hospital, despite her boyfriend’s request, but volunteers that she will go to an ambulatory care appointment with her psychiatrist on the next day.

——1.3 The psychiatrist arranges to speak with Ms. Genera alone during the clinical interview.

——1.4 The psychiatrist respects the patient’s preference not to be admitted to the hospital.

——1.5 The psychiatrist recommends diagnostic tests to occur at the time of the emergency evaluation.

——1.6 The psychiatrist sits with the patient’s boyfriend to offer emotional support and “a listening ear” after the clinical interview with the patient is completed.

——1.7 The psychiatrist documents accurately in the electronic medical record the full set of concerns raised by the patient and her boyfriend.

A resident in internal medicine with a well-established diagnosis of bipolar I disorder volunteers for a clinical trial that will test a new combination of medications and also involve two neuroimaging studies. The resident discusses the trial with his psychiatrist, who discourages the idea, stating that he has been concerned about the resident-patient, given the stresses of training and the severity of his illness. The resident responds, “Hey, Doc—get real! How often can you get $500—plus a brain scan, let alone TWO—free of charge?!” He decides to undergo screening for the clinical trial because he thinks he might benefit medically from an imaging test.

The resident knows that the trial will involve a washout period, so he decides to taper his medications in advance of the “official” enrollment date, 3 weeks away, which coincides with a planned vacation. Without medication, the resident becomes increasingly symptomatic. He has difficulty concentrating, becomes easily upset with team members, and develops progressively more erratic sleep. He was seen standing on the roof of the academic hospital and confided in a roommate that he was “tired of it all.”

Although he originally met criteria for the project, by the time of enrollment he had become too ill to enter the study. The psychiatrist-investigator permitted him to have the baseline neuroimaging study but did not allow the resident to progress to the full clinical trial. The resident returned to his apartment for his weeklong vacation. On the day he was scheduled to return to his training program, he did not turn up.

An 18-year-old male previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder is brought by his best friend to the emergency department of a rural hospital located near a ski area. The best friend reports that the patient “is completely wild—he just won’t stop—he’s going to kill himself on the slopes!”

The patient was first diagnosed when he experienced a “flat out manic” episode at age 13 years; he has been stable and doing well on lithium. He has a psychiatrist and therapist “back home,” although he will not provide their names.

The patient confided to his best friend that he “secretly” stopped his lithium recently, and the best friend states that the patient has been using alcohol. (“He says, ‘I like to get high while I’m high.’ ”) The patient is on vacation with his grandparents, two younger siblings, and the best friend.

The patient shows evidence of intoxication and is irritable but cooperative during the initial interview in the emergency department. His vitals are within normal limits and are stable. No abnormalities are found on physical examination.

While waiting to be seen, the patient appears to “sober up.” He is calm, pleasant, and respectful and thanks his friend and the emergency staff for helping him. He appears embarrassed. No abnormalities are found on mental status examination. The patient refuses a drug or urine test, and he refuses to allow the emergency physician to contact his grandparents or parents. The emergency physician calls a psychiatrist for consultation, which the patient declines.

Laura Weiss Roberts, M.D., M.A., Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Dr. Roberts reports: Owner, Investigator: Terra Nova Learning Systems

Srivastava S : Ethical considerations in the treatment of bipolar disorder . Focus ( Fall ); 9(4):461–464. Link , Google Scholar

Roberts LW, Hoop JG : Professionalism and Ethics: Q & A Self-Study Guide for Mental Health Professionals . Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2008 . Google Scholar

Roberts LW, Dyer A : A Concise Guide to Ethics in Mental Health Care . Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004 . Google Scholar

- Cited by None

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(3); 2023 Mar

- PMC10097604

A Case Study of Depression in High Achieving Students Associated With Moral Incongruence, Spiritual Distress, and Feelings of Guilt

Bahjat najeeb.

1 Institute of Psychiatry, Rawalpindi Medical University, Rawalpindi, PAK

Muhammad Faisal Amir Malik

Asad t nizami, sadia yasir.

Psychosocial and cultural factors play an important, but often neglected, role in depression in young individuals. In this article, we present two cases of young, educated males with major depressive disorder and prominent themes of guilt and spiritual distress. We explore the relationship between moral incongruence, spiritual distress, and feelings of guilt with major depressive episodes by presenting two cases of depression in young individuals who were high-achieving students. Both cases presented with low mood, psychomotor slowing, and selective mutism. Upon detailed history, spiritual distress and feelings of guilt due to internet pornographic use (IPU) and the resulting self-perceived addiction and moral incongruence were linked to the initiation and progression of major depressive episodes. The severity of the depressive episode was measured using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D). Themes of guilt and shame were measured using the State of Guilt and Shame Scale (SSGS). High expectations from the family were also a source of stress. Hence, it is important to keep these factors in mind while managing mental health problems in young individuals. Late adolescence and early adulthood are periods of high stress and vulnerabe to mental illness. Psychosocial determinants of depression in this age group generally go unexplored and unaddressed leading to suboptimal treatment, particularly in developing countries. Further research is needed to assess the importance of these factors and to determine ways to mitigate them.

Introduction

More attention needs to be paid to the psychological and societal factors which precipitate, prolong, and cause a relapse of depression in high-achieving young individuals. A young, bright individual has to contend with the pressures of -- often quite strenuous -- moral and financial expectations from the family, moral incongruence, spiritual distress, and feelings of guilt.

Moral incongruence is the distress that develops when a person continues to behave in a manner that is at odds with their beliefs. It may be associated with self-perceptions of addictions, including, for example, to pornographic viewing, social networking, and online gaming [ 1 ]. Perceived addiction to pornographic use rather than use is related to the high incidence of feelings of guilt and shame and predicts religious and spiritual struggle [ 2 - 3 ]. Guilt is a negative emotional and cognitive experience that occurs when a person believes that they have negated a standard of conduct or morals. It is a part of the diagnostic criteria for depression and various rating scales for depressive disorders [ 4 ]. Generalized guilt has a direct relationship with major depressive episodes. Guilt can be a possible target for preventive as well as therapeutic interventions in patients who experience major depressive episodes [ 5 ].

We explored the relationship between moral incongruence, spiritual distress, and feelings of guilt with major depressive episodes in high-achieving students. Both patients presented with symptoms of low mood, extreme psychomotor slowing, decreased oral intake, decreased sleep, and mutism. The medical evaluation and lab results were unremarkable. The severity of depressive episodes was measured using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D). Themes of guilt and shame were measured by using the State of Guilt and Shame Scale (SSGS). This case study was presented as a poster abstract at the ‘RCPsych Faculty of General Adult Psychiatry Annual Conference 2021.’

Case presentation

A 25-year-old Sunni Muslim, Punjabi male educated till Bachelors presented with a one-month history of fearfulness, weeping spells during prolonged prostration, social withdrawal, complaints of progressively decreasing verbal communication to the extent of giving nods and one-word answers, and decreased oral intake. His family believed that the patient's symptoms were the result of ‘Djinn’ possession. This was the patient’s second episode. The first episode was a year ago with similar symptoms of lesser severity that resolved on its own. Before being brought to us, he had been taken to multiple faith healers. No history of substance use was reported. Psychosexual history could not be explored at the time of admission. His pre-morbid personality was significant for anxious and avoidant traits.

On mental state examination (MSE), the patient had psychomotor retardation. He responded non-verbally, and that too slowly. Once, he wept excessively and said that he feels guilt over some grave sin. He refused to explain further, saying only that ‘I am afraid of myself.’ All baseline investigations returned normal. His score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) was 28 (Very Severe). A diagnosis of major depressive disorder was made. The patient was started on tab sertraline 50 mg per day and tab olanzapine 5 mg per day. After the second electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), his psychomotor retardation improved and he began to open up about his stressors. His HAM-D score at this time was 17 (moderate). He revealed distress due to feelings of excessive guilt and shame due to moral incongruence secondary to internet pornography use (IPU). The frequency and duration of IPU increased during the last six months preceding current illness. That, according to him, led him to withdraw socially and be fearful. He felt the burden of the high financial and moral expectations of the family. He complained that his parents were overbearing and overinvolved in his life. His family lacked insight into the cause of his illness and had difficulty accepting his current state. All these factors, particularly spiritual distress, were important in precipitating his illness. He scored high on both the shame and guilt domains (14/25, and 20/25, respectively) of the State of Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS).

He was discharged after three weeks following a cycle of four ECTs, psychotherapy, and psychoeducation of the patient and family. At the time of discharge, his HAM-D score was 10 (mild) and he reported no distress due to guilt or feeling of shame. He has been doing well for the past 5 months on outpatient follow-up.

A 21-year-old Sunni Muslim, Punjabi male, high-achieving student of high school presented with low mood, low energy, anhedonia, weeping spells, decreased oral intake, decreased talk, and impaired biological functions. His illness was insidious in onset and progressively worsened over the last 4 months. This was his first episode. He was brought to a psychiatric facility after being taken to multiple faith healers. Positive findings on the MSE included psychomotor slowing, and while he followed commands, he remained mute throughout the interview. Neurological examination and laboratory findings were normal. His score on HAM-D was 24 (very severe). He was diagnosed with major depressive disorder and started on tab lorazepam 1 mg twice daily with tab mirtazapine 15 mg which was built up to 30 mg once daily. He steadily improved, and two weeks later his score on HAM-D was 17 (moderate). His scores on SSGS signified excessive shame and guilt (16/25, and 21/25; respectively). He communicated his stressors which pertained to the psychosexual domain: he started masturbating at the age of 15, and he felt guilt following that but continued to do so putting him in a state of moral incongruence. He perceived his IPU as ‘an addiction’ and considered it a ‘gunahe kabira’ (major sin) and reported increased IPU in the months leading to the current depressive episode leading to him feeling guilt and anguish. Initially, during his illness, he was taken to multiple faith healers as the family struggled to recognize the true nature of the disease. Their understanding of the illness was of him being under the influence of ‘Kala Jadu’ (black magic). His parents had high expectations of him due to him being their only male child. After 3 weeks of treatment and psychotherapy, his condition improved and his HAM-D score came out to be 08 (mild). He was discharged on 30 mg mirtazapine HS and seen on fortnightly visits. His guilt and shame resolved with time after the resolution of depressive symptoms and counseling. We lost the follow-up after 6 months.

Late adolescence and young adulthood can be considered a unique and distinct period in the development of an individual [ 6 ]. It is a period of transition marked by new opportunities for development, growth, and evolution, as well as bringing new freedom and responsibilities. At the same time, this period brings interpersonal conflicts and an increased vulnerability to mental health disorders such as depression and suicidality. Biological, social, and psychological factors should all be explored in the etiology of mental health problems presenting at this age [ 6 ].

Socio-cultural factors played a significant role in the development and course of disease in our patients, and these included the authoritarian parenting style, initial lack of awareness about psychiatric illnesses causing a delay in seeking treatment, high expressed emotions in the family, and the burden of expectations from the family and the peer group. The strict and often quite unreasonable societal and family expectations in terms of what to achieve and how to behave and the resultant onus on a high-scoring, bright young individual make for a highly stressful mental state.

We used the ICD-10 criteria to diagnose depression clinically in our patients and the HAMD-17 to measure the severity of symptoms [ 7 ]. Both our patients had scores signifying severe depression initially. Psychomotor retardation was a prominent and shared clinical feature. Psychomotor retardation is the slowing of cognitive and motor functioning, as seen in slowed speech, thought processes, and motor movements [ 8 - 9 ]. The prevalence of psychomotor retardation in major depressive disorder ranges from 60% to 70% [ 10 ]. While psychomotor retardation often responds poorly to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), both tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA) produce a better response [ 9 , 11 ]. In addition, ECT shows a high treatment response in cases with significant psychomotor retardation [ 11 - 12 ].

A growing body of evidence shows that shame and guilt are features of numerous mental health problems. Guilt is the negative emotional and cognitive experience that follows the perception of negating or repudiating a set of deeply held morals [ 4 ]. Guilt can be generalized as well as contextual and is distinct from shame [ 13 ]. The distinction between guilt and shame allows for an independent assessment of the association of both guilt and shame with depressive disorder. As an example, a meta-analysis of 108 studies including 22,411 individuals measuring the association of shame and guilt in patients with depressive disorder found both shame and guilt to have a positive association with depressive symptoms. This association was stronger for shame (r=0.43) than for guilt (r=0.28) [ 14 ]. In our study, we used the State of Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS), to measure the feelings of guilt and shame [ 15 ]. The SSGS is a self-reported measure and consists of 5 items each for subsets of guilt and shame. SSGS scores showed high levels of guilt and shame in both of our patients.

During the course of treatment, we paid special attention to the psychological, cultural, and social factors that likely contributed to the genesis of the illness, delayed presentation to seek professional help, and could explain the recurrence of the depressive episodes. In particular, we observe the importance, particularly in this age group, of family and societal pressure, spiritual distress, moral incongruence, and feelings of guilt and shame. Moral incongruence is when a person feels that his behavior and his values or judgments about that behavior are not aligned. It can cause a person to more negatively perceive a behavior. As an example, the presence of moral congruence in an individual is a stronger contributor to perceiving internet pornographic use (IPU) as addictive than the actual use itself [ 16 ]. Therefore, moral congruence has a significant association with increased distress about IPU, enhanced psychological distress in general, and a greater incidence of perceived addiction to IPU [ 16 ].

Self-perceived addiction is an individual’s self-judgment that he or she belongs to the group of addicts. The pornography problems due to moral incongruence (PPMI) model is one framework that predicts the factors linking problematic pornographic use with self-perceived addiction. This model associates moral incongruence with self-perceived addiction to problematic pornographic use [ 17 ]. A recent study on the US adult population also showed a high association of guilt and shame with moral incongruence regarding IPU [ 18 ]. Another factor of importance in our patients was spiritual distress, which is the internal strain, tension, and conflict with what people hold sacred [ 19 ]. Spiritual distress can be intrapersonal, interpersonal, or supernatural [ 20 ]. Research indicates that IPU causes people to develop spiritual distress that can ultimately lead to depression [ 16 - 17 ].

Conclusions

In both our cases the initial presentation was that of psychomotor slowing, selective mutism, and affective symptoms of low mood, therefore, a diagnosis of depressive illness was made. One week into treatment, improvement was noted both clinically as well as on the psychometric scales. Upon engaging the patients to give an elaborate psychosexual history, moral incongruence, spiritual distress, and feelings of guilt, linked particularly to self-perceived addiction to IPU were found. Sensitivity to the expectations of the parents, the cognizance of failing them because of illness, and their own and family’s lack of understanding of the situation were additional sources of stress. Hence, it is imperative to note how these factors play an important role in the initiation, progression, and relapse of mental health problems in young individuals.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the participants of this study for their cooperation.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

Module 7: Mood Disorders

Case studies: mood disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify mood disorders in case studies

Let’s use the information we’ve learned in this module to examine a few fictional characters.

Case Study: A.J. from The Sopranos

We’ll start with the case study of Anthony Soprano, Jr. (referred to as A.J.) from The Sopranos (a HBO television series, 1999–2005). A.J. started a new job working construction and was getting more stable in his life following dropping out of community college. He met a girl named Blanca at the construction site and they started dating.

Figure 1 . A.J. became sad and irritable following his failed engagement.

The two became really close, and A. J. eventually proposed to Blanca. After some reconsideration, she decided that A.J. was not right for her and broke up with him. Following the breakup, A.J. is sad and lethargic. A.J. continued to work at the construction site for some time, but the sight of Blanca talking to other men becomes too much for him, so he eventually quits. After the breakup with Blanca, A.J. started sleeping all the time and would not come out of his room. He had a decreased appetite and anhedonia. He seemed to lack energy for quite some time. There were no suicidal ideations initially. Though his symptoms seemed to be improving slightly, after an incident with another student, he again confined himself to his room. He attempted to kill himself by jumping into a pool with a cinderblock around his leg while his parents were out of the house. Luckily, his father came home and saved him prior to there being any significant damage. A.J. was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility and received the therapy he needed.

Proper treatment of A.J.’s diagnosis would, given his severe symptom levels, include beginning with antidepressant medication. Psychotherapy, specifically CBT (which has shown great success with a combination of antidepressant medication), DBT, CT-SP, or BCBT, may also prove helpful.

Case Study: Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh

Background information.

Figure 2 . Eeyore.

Eeyore is an older gray donkey. There are no documents indicating the exact age. Eeyore does not have an occupation. One main difficulty Eeyore has elaborated on is his detachable tail, which seems to cause him several problems. He has indicated that his goals are to remain strong for his friends despite his lack of self-confidence, and as a result, he often feels lonely without support from others that he is close to. Some forms of coping mechanisms include trying to feel useful in the presence of others and also trying his best to find pleasure in life.

Description of the Problem

Eeyore constantly insists that his tail falls off rather frequently. Eeyore’s posture typically involves a slumped head and droopy eyes, and he commonly says, “thanks for noticing me.” Sluggish movement is also apparent, without any physical cause for movement delay. He seems to step on his tail often and fall down. Eeyore indicates that sometimes it seems that even his close friends do not need him. Around friends, he typically makes comments about his relative unimportance and travels near the back of the pack. He also stated that although he tries to force a smile, a real smile has not existed in a long time, even though others try to cheer him up. He often feels empty even when accompanied by friends. Eeyore also seems to experience a loss of energy throughout the day, although sleeping habits are not explicitly expressed.

Eeyore met criteria including depressed mood most of the day, markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities, fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day, feelings of worthlessness, and diminished ability to think or concentrate.

Case Study: Ashlynn

Ashlynn is a 21-year-old college student and political science major who has struggled with depression on and off since beginning college. She was picked up by campus police after being caught vandalizing a man’s apartment and was recommended to a psychiatrist after exhibiting erratic behavior. She explained that she was only at the man’s apartment because he was a classmate and she wanted to prove to him how much she liked him. She spoke about how that, even though he didn’t know it yet, they were destined to be together and that they would someday run for office together and be the first-ever married president and vice president. She was irritable and argumentative, and defensive about her behavior. She indicated that she didn’t care about her finals anymore (though she had consistently good grades in the past), she had been pulling all-nighters to research politicians, and had been experimenting with illicit drugs.

- Major Depressive Disorder Case Studies. Authored by : Bill Pelz. Provided by : Lumen. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-abnormalpsych/chapter/major-depressive-disorder/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Engagement ring. Located at : https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-qfvpb . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Eeyore. Located at : https://pixy.org/852182/ . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

April 17, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

Study identifies new metric for diagnosing autism

by Russ Bahorsky, University of Virginia

Autism spectrum disorder has yet to be linked to a single cause, due to the wide range of its symptoms and severity. However, a study by University of Virginia researchers suggests a promising new approach to finding answers, one that could lead to advances in the study of other neurological diseases and disorders.

The work is published in the journal PLOS ONE .

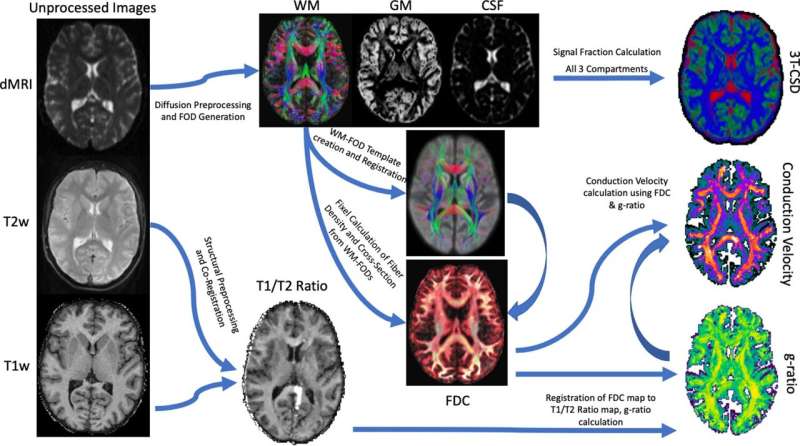

Current approaches to autism research involve observing and understanding the disorder through the study of its behavioral consequences, using techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging that map the brain's responses to input and activity, but little work has been done to understand what's causing those responses.

However, researchers with UVA's College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences have been able to better understand the physiological differences between the brain structures of autistic and non-autistic individuals through the use of Diffusion MRI, a technique that measures molecular diffusion in biological tissue, to observe how water moves throughout the brain and interacts with cellular membranes. The approach has helped the UVA team develop mathematical models of brain microstructures that have helped identify structural differences in the brains of those with autism and those without.

"It hasn't been well understood what those differences might be," said Benjamin Newman, a postdoctoral researcher with UVA's Department of Psychology, recent graduate of UVA School of Medicine's neuroscience graduate program and lead author of the new research paper. "This new approach looks at the neuronal differences contributing to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder ."

Building on the work of Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley, who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Medicine for describing the electrochemical conductivity characteristics of neurons, Newman and his co-authors applied those concepts to understand how that conductivity differs in those with autism and those without, using the latest neuroimaging data and computational methodologies.

The result is a first-of-its-kind approach to calculating the conductivity of neural axons and their capacity to carry information through the brain. The study also offers evidence that those microstructural differences are directly related to participants' scores on the Social Communication Questionnaire, a common clinical tool for diagnosing autism.

"What we're seeing is that there's a difference in the diameter of the microstructural components in the brains of autistic people that can cause them to conduct electricity slower," Newman said. "It's the structure that constrains how the function of the brain works."

One of Newman's co-authors, John Darrell Van Horn, a professor of psychology and data science at UVA, remarked that so often we try to understand autism through a collection of behavioral patterns which might be unusual or seem different.

"But understanding those behaviors can be a bit subjective, depending on who's doing the observing," Van Horn said. "We need greater fidelity in terms of the physiological metrics that we have so that we can better understand where those behaviors coming from. This is the first time this kind of metric has been applied in a clinical population, and it sheds some interesting light on the origins of ASD."

Van Horn said there's been a lot of work done with functional magnetic resonance imaging, looking at blood oxygen related signal changes in autistic individuals, but this research, he said, "goes a little bit deeper."

"It's asking not if there's a particular cognitive functional activation difference; it's asking how the brain actually conducts information around itself through these dynamic networks," Van Horn said. "And I think that we've been successful showing that there's something that's uniquely different about autistic-spectrum-disorder-diagnosed individuals relative to otherwise typically developing control subjects."

Newman and Van Horn, along with co-authors Jason Druzgal and Kevin Pelphrey from the UVA School of Medicine, are affiliated with the National Institute of Health's Autism Center of Excellence (ACE), an initiative that supports large-scale multidisciplinary and multi-institutional studies on ASD with the aim of determining the disorder's causes and potential treatments.

According to Pelphrey, a neuroscientist and expert on brain development and the study's principal investigator, the overarching aim of the ACE project is to lead the way in developing a precision medicine approach to autism.

"This study provides the foundation for a biological target to measure treatment response and allows us to identify avenues for future treatments to be developed," he said.

Van Horn added that study may also have implications for the examination, diagnosis, and treatment of other neurological disorders like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.

"This is a new tool for measuring the properties of neurons which we are particularly excited about. We are still exploring what we might be able to detect with it," Van Horn said.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Occupations that are cognitively stimulating may be protective against later-life dementia

7 hours ago

Researchers develop a new way to safely boost immune cells to fight cancer

Apr 19, 2024

New compound from blessed thistle may promote functional nerve regeneration

New research defines specific genomic changes associated with the transmissibility of the mpox virus

New study confirms community pharmacies can help people quit smoking

Researchers discover glial hyper-drive for triggering epileptic seizures

Deeper dive into the gut microbiome shows changes linked to body weight

A new therapeutic target for traumatic brain injury

Dozens of COVID virus mutations arose in man with longest known case, research finds

Researchers explore causal machine learning, a new advancement for AI in health care

Related stories.

Chemical regulates light processing differently in the autistic and non-autistic eye, new study finds

Apr 4, 2024

Autism develops differently in girls than boys, new research suggests

Apr 16, 2021

Researchers identify altered functional brain connectivity in autism subtypes

Dec 5, 2023

Scientists link genes to brain anatomy in autism

Feb 27, 2018

The hidden connection between adverse drug reactions and autism spectrum disorder

Sep 20, 2023

Guidelines for inclusive language in autism research

Sep 29, 2022

Recommended for you

How myeloid cell replacement could help treat autoimmune encephalomyelitis

Researchers discover dynamic DNA structures that regulate the formation of memory

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

AP Psychology - Unit 8 - Psych Disorder Case Study Stations Worksheet. Station #1. A married woman, whose life was complicated by her mother's living in their home, complained that she felt tense and irritable most of the time. She was apprehensive for fear that something would happen to her mother, her husband, her children, or herself.

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. ... Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety ...

Link each of the following sets of patient's lab results to patho & S&S of cirrhosis: Case Study Gastrointestinal Disorders Answers a. enzymes b. liver enzymes: AST 1000 (normal 10-40); ALT 1100 (normal 10-55) - if there is injury / destruction of hepatocytes such as occurs in cirrhosis there will be release of into ...

2. Hypochondriasis. 3. pain disorder. 4. body dysmorphic. case study disorders. generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Click the card to flip 👆. anxiety everywhere in life. - unable to identify single cause.

Case Study: Lorrie. Figure 1. Lorrie. Lorrie Wiley grew up in a neighborhood on the west side of Baltimore, surrounded by family and friends struggling with drug issues. She started using marijuana and "popping pills" at the age of 13, and within the following decade, someone introduced her to cocaine and heroin.

Case Study: The Grinch. The Grinch, who is a bitter and cave-dwelling creature, lives on the snowy Mount Crumpits, a high mountain north of Whoville. His age is undisclosed, but he looks to be in his 40s and does not have a job. He normally spends a lot of his time alone in his cave. He is often depressed and spends his time avoiding and hating ...

edited by BarnhillJohn W., M.D. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2014, 402 pp., $89.00. DSM-5 Clinical Cases makes the rather overwhelming DSM-5 much more accessible to mental health clinicians by using clinical examples—the way many clinicians learn best—to illustrate the changes in diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5.

Identify somatic disorders in case studies; Case Study: Samuel. The patient, named "Samuel," is a 28-year-old, final year medical student from the south-eastern region of Nigeria in sub-Saharan Africa. He was declared missing for 10 days then later seen in a city in south-western Nigeria, a distance of about 634 km from south-eastern ...

Case Study Details. Mary is a 26-year-old African-American woman who presents with a history of non-suicidal self-injury, specifically cutting her arms and legs, since she was a teenager. She has made two suicide attempts by overdosing on prescribed medications, one as a teenager and one six months ago; she also reports chronic suicidal ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like During the initial assessment, the nurse should focus on which areas that are most characteristic of anxiety? A. Symptoms restlessness, difficulty concentrating, irritability.. B. Social interactions such as withdrawal, shunning family, and drinking alcohol. C. Increasing symptoms of depression with consistently sad, low mood. D ...

Case Study Details. Mike is a 20 year-old who reports to you that he feels depressed and is experiencing a significant amount of stress about school, noting that he'll "probably flunk out.". He spends much of his day in his dorm room playing video games and has a hard time identifying what, if anything, is enjoyable in a typical day.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) UNFOLDING Reasoning ANSWER KEY Marcus Jackson, 34 years old Primary Concept Mood and Affect Interrelated Concepts (In order of emphasis) ... Clinical Judgment 5. Patient Education 6. Communication 7. Collaboration UNFOLDING Reasoning Case Study: ANSWER KEY History of Present Problem: Marcus Jackson is a 34 ...

7. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1067-1074. 8. Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta ...

Case Study: Bryant. Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized ...

Case Studies on Disorders Check your understanding of psychological disorders by reading the information on the following cases, and stating the most appropriate diagnosis for each person. ... ANSWERS 1. Bipolar 2. Major Depression 3. No disorder. This is to be expected so soon after the loss of a loved one. 4. Major Depression

Case 1. Ms. Genera is a 36-year-old woman with bipolar II disorder, first diagnosed in college, who is brought to the psychiatric emergency room by her boyfriend of 5 years. He is hoping that she will be admitted to the hospital "before she goes all-the-way manic.". He reports that she "almost lost her job last time!".

Triggers, attitudes to alcohol-related situations, and positive and negative consequences of drinking thoughts (gives points of focus for treatment) Drug treatment of alcohol abuse. Disulfiram/antabuse. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Borderline personality disorder treatment plan, What is dialectic behaviour ...

As an example, a meta-analysis of 108 studies including 22,411 individuals measuring the association of shame and guilt in patients with depressive disorder found both shame and guilt to have a positive association with depressive symptoms. This association was stronger for shame (r=0.43) than for guilt (r=0.28) .

100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology ... Expand All. Part 1: Cardiovascular Disorders. Case Study 1: Acute Myocardial Infarction. Answers to Disease Summary Questions; Answers to Patient Case Questions; Disease Summary; Case Study 2: Aneurysm of the Abdominal Aorta ... Case Study 47: Bipolar Disorder. Answers to Disease Summary Questions ...

We'll start with the case study of Anthony Soprano, Jr. (referred to as A.J.) from The Sopranos (a HBO television series, 1999-2005). A.J. started a new job working construction and was getting more stable in his life following dropping out of community college. He met a girl named Blanca at the construction site and they started dating ...

Patient who has a blockage or a hemorrhage in the brain with neural deficits that last longer than a day has had a/an. Subdural hemorrhage (hematoma) A hemorrhage above the outer covering of the meninges is a/an. dyslexia. Inability or difficulty with reading and writing is. anosmia. A patient who has lost his/her sense of smell has. Narcolepsy.

Case Studies on Disorders Check your understanding of psychological disorders by reading the information on the following cases, listing the symptoms, and stating the most appropriate diagnosis for each person. Some of these cases may not have disorders. In that case, indicate that the person does not have a disorder, and why that would be your answer.

Autism spectrum disorder has yet to be linked to a single cause, due to the wide range of its symptoms and severity. However, a study by University of Virginia researchers suggests a promising new ...

Find step-by-step solutions and answers to Winningham's Critical Thinking Cases in Nursing - 9780323291965, as well as thousands of textbooks so you can move forward with confidence. ... Patients with Multiple Disorders. Page 461: Case Study 98. Page 469: Case Study 99. Page 475: Case Study 100. Page 481: Case Study 101. ... Case Study 149 ...