Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

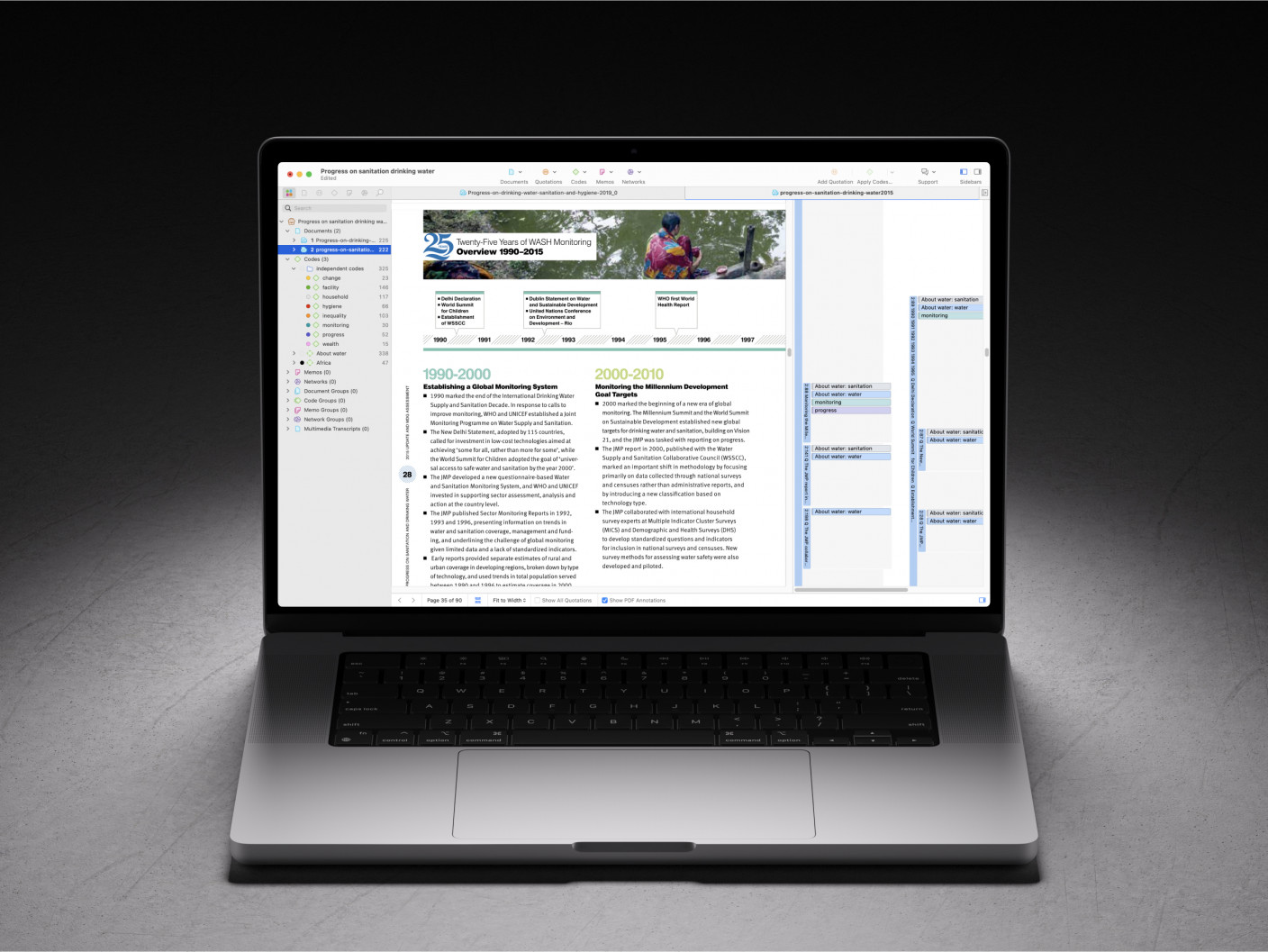

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

How to Write a Case Study: The Compelling Step-by-Step Guide

Is there a poignant pain point that needs to be addressed in your company or industry? Do you have a possible solution but want to test your theory? Why not turn this drive into a transformative learning experience and an opportunity to produce a high-quality business case study? However, before that occurs, you may wonder how to write a case study.

You may also be thinking about why you should produce one at all. Did you know that case studies are impactful and the fifth most used type of content in marketing , despite being more resource-intensive to produce?

Below, we’ll delve into what a case study is, its benefits, and how to approach business case study writing:

Definition of a Written case study and its Purpose

A case study is a research method that involves a detailed and comprehensive examination of a specific real-life situation. It’s often used in various fields, including business, education, economics, and sociology, to understand a complex issue better.

It typically includes an in-depth analysis of the subject and an examination of its context and background information, incorporating data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and existing literature.

The ultimate aim is to provide a rich and detailed account of a situation to identify patterns and relationships, generate new insights and understanding, illustrate theories, or test hypotheses.

Importance of Business Case Study Writing

As such an in-depth exploration into a subject with potentially far-reaching consequences, a case study has benefits to offer various stakeholders in the organisation leading it.

- Business Founders: Use business case study writing to highlight real-life examples of companies or individuals who have benefited from their products or services, providing potential customers with a tangible demonstration of the value their business can bring. It can be effective for attracting new clients or investors by showcasing thought leadership and building trust and credibility.

- Marketers through case studies and encourage them to take action: Marketers use a case studies writer to showcase the success of a particular product, service, or marketing campaign. They can use persuasive storytelling to engage the reader, whether it’s consumers, clients, or potential partners.

- Researchers: They allow researchers to gain insight into real-world scenarios, explore a variety of perspectives, and develop a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to success or failure. Additionally, case studies provide practical business recommendations and help build a body of knowledge in a particular field.

How to Write a Case Study – The Key Elements

Considering how to write a case study can seem overwhelming at first. However, looking at it in terms of its constituent parts will help you to get started, focus on the key issue(s), and execute it efficiently and effectively.

Problem or Challenge Statement

A problem statement concisely describes a specific issue or problem that a written case study aims to address. It sets the stage for the rest of the case study and provides context for the reader.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study problem statement:

- Identify the problem or issue that the case study will focus on.

- Research the problem to better understand its context, causes, and effects.

- Define the problem clearly and concisely. Be specific and avoid generalisations.

- State the significance of the problem: Explain why the issue is worth solving. Consider the impact it has on the individual, organisation, or industry.

- Provide background information that will help the reader understand the context of the problem.

- Keep it concise: A problem statement should be brief and to the point. Avoid going into too much detail – leave this for the body of the case study!

Here is an example of a problem statement for a case study:

“ The XYZ Company is facing a problem with declining sales and increasing customer complaints. Despite improving the customer experience, the company has yet to reverse the trend . This case study will examine the causes of the problem and propose solutions to improve sales and customer satisfaction. “

Solutions and interventions

Business case study writing provides a solution or intervention that identifies the best course of action to address the problem or issue described in the problem statement.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study solution or intervention:

- Identify the objective , which should be directly related to the problem statement.

- Analyse the data, which could include data from interviews, observations, and existing literature.

- Evaluate alternatives that have been proposed or implemented in similar situations, considering their strengths, weaknesses, and impact.

- Choose the best solution based on the objective and data analysis. Remember to consider factors such as feasibility, cost, and potential impact.

- Justify the solution by explaining how it addresses the problem and why it’s the best solution with supportive evidence.

- Provide a detailed, step-by-step plan of action that considers the resources required, timeline, and expected outcomes.

Example of a solution or intervention for a case study:

“ To address the problem of declining sales and increasing customer complaints at the XYZ Company, we propose a comprehensive customer experience improvement program. “

“ This program will involve the following steps:

- Conducting customer surveys to gather feedback and identify areas for improvement

- Implementing training programs for employees to improve customer service skills

- Revising the company’s product offerings to meet customer needs better

- Implementing a customer loyalty program to encourage repeat business “

“ These steps will improve customer satisfaction and increase sales. We expect a 10% increase in sales within the first year of implementation, based on similar programs implemented by other companies in the industry. “

Possible Results and outcomes

Writing case study results and outcomes involves presenting the impact of the proposed solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study results and outcomes:

- Evaluate the solution by measuring its effectiveness in addressing the problem statement. That could involve collecting data, conducting surveys, or monitoring key performance indicators.

- Present the results clearly and concisely, using graphs, charts, and tables to represent the data where applicable visually. Be sure to include both quantitative and qualitative results.

- Compare the results to the expectations set in the solution or intervention section. Explain any discrepancies and why they occurred.

- Discuss the outcomes and impact of the solution, considering the benefits and drawbacks and what lessons can be learned.

- Provide recommendations for future action based on the results. For example, what changes should be made to improve the solution, or what additional steps should be taken?

Example of results and outcomes for a case study:

“ The customer experience improvement program implemented at the XYZ Company was successful. We found significant improvement in employee health and productivity. The program, which included on-site exercise classes and healthy food options, led to a 25% decrease in employee absenteeism and a 15% increase in productivity . “

“ Employee satisfaction with the program was high, with 90% reporting an improved work-life balance. Despite initial costs, the program proved to be cost-effective in the long run, with decreased healthcare costs and increased employee retention. The company plans to continue the program and explore expanding it to other offices .”

Case Study Key takeaways

Key takeaways are the most important and relevant insights and lessons that can be drawn from a case study. Key takeaways can help readers understand the most significant outcomes and impacts of the solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study key takeaways:

- Summarise the problem that was addressed and the solution that was proposed.

- Highlight the most significant results from the case study.

- Identify the key insights and lessons , including what makes the case study unique and relevant to others.

- Consider the broader implications of the outcomes for the industry or field.

- Present the key takeaways clearly and concisely , using bullet points or a list format to make the information easy to understand.

Example of key takeaways for a case study:

- The customer experience improvement program at XYZ Company successfully increased customer satisfaction and sales.

- Employee training and product development were critical components of the program’s success.

- The program resulted in a 20% increase in repeat business, demonstrating the value of a customer loyalty program.

- Despite some initial challenges, the program proved cost-effective in the long run.

- The case study results demonstrate the importance of investing in customer experience to improve business outcomes.

Steps for a Case Study Writer to Follow

If you still feel lost, the good news is as a case studies writer; there is a blueprint you can follow to complete your work. It may be helpful at first to proceed step-by-step and let your research and analysis guide the process:

- Select a suitable case study subject: Ask yourself what the purpose of the business case study is. Is it to illustrate a specific problem and solution, showcase a success story, or demonstrate best practices in a particular field? Based on this, you can select a suitable subject by researching and evaluating various options.

- Research and gather information: We have already covered this in detail above. However, always ensure all data is relevant, valid, and comes from credible sources. Research is the crux of your written case study, and you can’t compromise on its quality.

- Develop a clear and concise problem statement: Follow the guide above, and don’t rush to finalise it. It will set the tone and lay the foundation for the entire study.

- Detail the solution or intervention: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed solution or intervention.

- Present the results and outcomes: Remember that a case study is an unbiased test of how effectively a particular solution addresses an issue. Not all case studies are meant to end in a resounding success. You can often learn more from a loss than a win.

- Include key takeaways and conclusions: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed business case study solution or intervention.

Tips for How to Write a Case Study

Here are some bonus tips for how to write a case study. These tips will help improve the quality of your work and the impact it will have on readers:

- Use a storytelling format: Just because a case study is research-based doesn’t mean it has to be boring and detached. Telling a story will engage readers and help them better identify with the problem statement and see the value in the outcomes. Framing it as a narrative in a real-world context will make it more relatable and memorable.

- Include quotes and testimonials from stakeholders: This will add credibility and depth to your written case study. It also helps improve engagement and will give your written work an emotional impact.

- Use visuals and graphics to support your narrative: Humans are better at processing visually presented data than endless walls of black-on-white text. Visual aids will make it easier to grasp key concepts and make your case study more engaging and enjoyable. It breaks up the text and allows readers to identify key findings and highlights quickly.

- Edit and revise your case study for clarity and impact: As a long and involved project, it can be easy to lose your narrative while in the midst of it. Multiple rounds of editing are vital to ensure your narrative holds, that your message gets across, and that your spelling and grammar are correct, of course!

Our Final Thoughts

A written case study can be a powerful tool in your writing arsenal. It’s a great way to showcase your knowledge in a particular business vertical, industry, or situation. Not only is it an effective way to build authority and engage an audience, but also to explore an important problem and the possible solutions to it. It’s a win-win, even if the proposed solution doesn’t have the outcome you expect. So now that you know more about how to write a case study, try it or talk to us for further guidance.

Are you ready to write your own case study?

Begin by bookmarking this article, so you can come back to it. And for more writing advice and support, read our resource guides and blog content . If you are unsure, please reach out with questions, and we will provide the answers or assistance you need.

Categorised in: Resources

This post was written by Premier Prose

© 2024 Copyright Premier Prose. Website Designed by Ubie

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

More information about our Cookie Policy

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. Professor at Harvard Business School and the former dean of HBS.

Partner Center

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 1

- What is a case study?

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Roberta Heale 1 ,

- Alison Twycross 2

- 1 School of Nursing , Laurentian University , Sudbury , Ontario , Canada

- 2 School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Roberta Heale, School of Nursing, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON P3E2C6, Canada; rheale{at}laurentian.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102845

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

What is it?

Case study is a research methodology, typically seen in social and life sciences. There is no one definition of case study research. 1 However, very simply… ‘a case study can be defined as an intensive study about a person, a group of people or a unit, which is aimed to generalize over several units’. 1 A case study has also been described as an intensive, systematic investigation of a single individual, group, community or some other unit in which the researcher examines in-depth data relating to several variables. 2

Often there are several similar cases to consider such as educational or social service programmes that are delivered from a number of locations. Although similar, they are complex and have unique features. In these circumstances, the evaluation of several, similar cases will provide a better answer to a research question than if only one case is examined, hence the multiple-case study. Stake asserts that the cases are grouped and viewed as one entity, called the quintain . 6 ‘We study what is similar and different about the cases to understand the quintain better’. 6

The steps when using case study methodology are the same as for other types of research. 6 The first step is defining the single case or identifying a group of similar cases that can then be incorporated into a multiple-case study. A search to determine what is known about the case(s) is typically conducted. This may include a review of the literature, grey literature, media, reports and more, which serves to establish a basic understanding of the cases and informs the development of research questions. Data in case studies are often, but not exclusively, qualitative in nature. In multiple-case studies, analysis within cases and across cases is conducted. Themes arise from the analyses and assertions about the cases as a whole, or the quintain, emerge. 6

Benefits and limitations of case studies

If a researcher wants to study a specific phenomenon arising from a particular entity, then a single-case study is warranted and will allow for a in-depth understanding of the single phenomenon and, as discussed above, would involve collecting several different types of data. This is illustrated in example 1 below.

Using a multiple-case research study allows for a more in-depth understanding of the cases as a unit, through comparison of similarities and differences of the individual cases embedded within the quintain. Evidence arising from multiple-case studies is often stronger and more reliable than from single-case research. Multiple-case studies allow for more comprehensive exploration of research questions and theory development. 6

Despite the advantages of case studies, there are limitations. The sheer volume of data is difficult to organise and data analysis and integration strategies need to be carefully thought through. There is also sometimes a temptation to veer away from the research focus. 2 Reporting of findings from multiple-case research studies is also challenging at times, 1 particularly in relation to the word limits for some journal papers.

Examples of case studies

Example 1: nurses’ paediatric pain management practices.

One of the authors of this paper (AT) has used a case study approach to explore nurses’ paediatric pain management practices. This involved collecting several datasets:

Observational data to gain a picture about actual pain management practices.

Questionnaire data about nurses’ knowledge about paediatric pain management practices and how well they felt they managed pain in children.

Questionnaire data about how critical nurses perceived pain management tasks to be.

These datasets were analysed separately and then compared 7–9 and demonstrated that nurses’ level of theoretical did not impact on the quality of their pain management practices. 7 Nor did individual nurse’s perceptions of how critical a task was effect the likelihood of them carrying out this task in practice. 8 There was also a difference in self-reported and observed practices 9 ; actual (observed) practices did not confirm to best practice guidelines, whereas self-reported practices tended to.

Example 2: quality of care for complex patients at Nurse Practitioner-Led Clinics (NPLCs)

The other author of this paper (RH) has conducted a multiple-case study to determine the quality of care for patients with complex clinical presentations in NPLCs in Ontario, Canada. 10 Five NPLCs served as individual cases that, together, represented the quatrain. Three types of data were collected including:

Review of documentation related to the NPLC model (media, annual reports, research articles, grey literature and regulatory legislation).

Interviews with nurse practitioners (NPs) practising at the five NPLCs to determine their perceptions of the impact of the NPLC model on the quality of care provided to patients with multimorbidity.

Chart audits conducted at the five NPLCs to determine the extent to which evidence-based guidelines were followed for patients with diabetes and at least one other chronic condition.

The three sources of data collected from the five NPLCs were analysed and themes arose related to the quality of care for complex patients at NPLCs. The multiple-case study confirmed that nurse practitioners are the primary care providers at the NPLCs, and this positively impacts the quality of care for patients with multimorbidity. Healthcare policy, such as lack of an increase in salary for NPs for 10 years, has resulted in issues in recruitment and retention of NPs at NPLCs. This, along with insufficient resources in the communities where NPLCs are located and high patient vulnerability at NPLCs, have a negative impact on the quality of care. 10

These examples illustrate how collecting data about a single case or multiple cases helps us to better understand the phenomenon in question. Case study methodology serves to provide a framework for evaluation and analysis of complex issues. It shines a light on the holistic nature of nursing practice and offers a perspective that informs improved patient care.

- Gustafsson J

- Calanzaro M

- Sandelowski M

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Beginner Guides

What is a Case Study? [+6 Types of Case Studies]

By Ronita Mohan , Sep 20, 2021

Case studies have become powerful business tools. But what is a case study? What are the benefits of creating one? Are there limitations to the format?

If you’ve asked yourself these questions, our helpful guide will clear things up. Learn how to use a case study for business. Find out how cases analysis works in psychology and research.

We’ve also got examples of case studies to inspire you.

Haven’t made a case study before? You can easily create a case study with Venngage’s customizable templates.

CREATE A CASE STUDY

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study, what is the case study method, benefits of case studies, limitations of case studies, types of case studies, faqs about case studies.

Case studies are research methodologies. They examine subjects, projects, or organizations to tell a story.

USE THIS TEMPLATE

Numerous sectors use case analyses. The social sciences, social work, and psychology create studies regularly.

Healthcare industries write reports on patients and diagnoses. Marketing case study examples , like the one below, highlight the benefits of a business product.

CREATE THIS REPORT TEMPLATE

Now that you know what a case study is, we explain how case reports are used in three different industries.

What is a business case study?

A business or marketing case study aims at showcasing a successful partnership. This can be between a brand and a client. Or the case study can examine a brand’s project.

There is a perception that case studies are used to advertise a brand. But effective reports, like the one below, can show clients how a brand can support them.

Hubspot created a case study on a customer that successfully scaled its business. The report outlines the various Hubspot tools used to achieve these results.

Hubspot also added a video with testimonials from the client company’s employees.

So, what is the purpose of a case study for businesses? There is a lot of competition in the corporate world. Companies are run by people. They can be on the fence about which brand to work with.

Business reports stand out aesthetically, as well. They use brand colors and brand fonts . Usually, a combination of the client’s and the brand’s.

With the Venngage My Brand Kit feature, businesses can automatically apply their brand to designs.

A business case study, like the one below, acts as social proof. This helps customers decide between your brand and your competitors.

Don’t know how to design a report? You can learn how to write a case study with Venngage’s guide. We also share design tips and examples that will help you convert.

Related: 55+ Annual Report Design Templates, Inspirational Examples & Tips [Updated]

What is a case study in psychology?

In the field of psychology, case studies focus on a particular subject. Psychology case histories also examine human behaviors.

Case reports search for commonalities between humans. They are also used to prescribe further research. Or these studies can elaborate on a solution for a behavioral ailment.

The American Psychology Association has a number of case studies on real-life clients. Note how the reports are more text-heavy than a business case study.

Famous psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and Anna O popularised the use of case studies in the field. They did so by regularly interviewing subjects. Their detailed observations build the field of psychology.

It is important to note that psychological studies must be conducted by professionals. Psychologists, psychiatrists and therapists should be the researchers in these cases.

Related: What Netflix’s Top 50 Shows Can Teach Us About Font Psychology [Infographic]

What is a case study in research?

Research is a necessary part of every case study. But specific research fields are required to create studies. These fields include user research, healthcare, education, or social work.