PHILO-notes

Free Online Learning Materials

Aristotle’s Concept of the Self

Aristotle was undoubtedly the most brilliant student of Plato. Yet, Aristotle diverged from most of Plato’s fundamental philosophies, especially on the concept of the self.

As we may already know, Plato is sure that the true self is the soul, not the body. And to be specific, the true self for Plato is the rational soul which is separable from the body. Aristotle’s concept of the self is quite the opposite.

Aristotle’s concept of the self is more complicated as he talked about so many things in this topic. However, there is one main theme in Aristotle’s narrative of the soul that guides us in understanding his concept of the self, that is, the human person is a “rational animal”. In other words, for Aristotle, the human person is simply an animal that thinks.

How did Aristotle come up with the idea that the human person is just an animal that thinks? His idea of the soul provides the key.

Aristotle defines the soul as the principle of life. And as the principle of life, it causes the body to live. This explains why for Aristotle all living beings have souls. Because for Aristotle all living beings have souls, then it follows that plants and animals (in addition to humans) have souls too. Thus, Aristotle distinguishes three levels of soul, namely, vegetative soul, sensitive soul, and rational soul.

According to Aristotle, the vegetative soul is found in plants, while the sensitive and rational souls are found in animals and humans respectively.

According to Aristotle, plants have souls because they possess the three basic requirements for something to be called a “living being”, that is, the capacity to grow, reproduce, and feed itself.

Sensitive souls also grow, reproduce, and feed themselves; but unlike vegetative souls, sensitive souls are capable of sensation.

Finally, rational souls grow, reproduce, feed themselves, and feel; but unlike the sensitive souls, rational souls are capable of thinking. According to Aristotle, this highest level of soul is present only in humans.

Since humans possess all the characteristics of animals, that is, the capacity to grow, reproduce, feed itself, and feel, in addition to being rational, Aristotle concludes that the human person is just an animal that thinks. As Aristotle’s famous dictum on the human person goes, “Man is a rational animal.”

Again, this explains why for Aristotle the human person is just an animal that thinks.

Now, for Aristotle, the human person is not a soul distinct from the body as Plato would have us believe. Aristotle argues that the self or the human person is a composite of body and soul and that the two are inseparable. Aristotle’s concept of the self, therefore, was constructed in terms of hylomorphism.

Aristotle views the soul as the “form” of the human body. And as “form” of the body, the soul is the very structure of the human body which allows humans to perform activities of life, such as thinking, willing, imagining, desiring, and perceiving.

While Aristotle believes that the human person is essentially body and soul, he was led to interpret the “true self” of humans as the soul that animates the body. However, Aristotle believes that the body is as important as the soul as it serves as “matter” to the soul.

Although Aristotle contends that the soul is the form of the body, he did not argue for the primacy of the former over the latter. Again, Aristotle’s concept of the self is hylomorphic, that is, the self or the human person is composed of body and soul. The two are inseparable. Thus, we cannot talk about the self with a soul only or a self with a body only. For Aristotle, the self is essentially body and soul. Indeed, for Aristotle, the self is a unified creature.

Hellenic values; a volunteer helps a refugee girl after arriving on an inflatable boat at Lesbos, Greece, March 2016. Photo by Alexander Koerner/Getty

Why read Aristotle today?

Modern self-help draws heavily on stoic philosophy. but aristotle was better at understanding real human happiness.

by Edith Hall + BIO

In the Western world, only since the mid-18th century has it been possible to discuss ethical questions publicly without referring to Christianity. Modern thinking about morality, which assumes that gods do not exist, or at least do not intervene, is in its infancy. But the ancient Greeks and Romans elaborated robust philosophical schools of ethical thought for more than a millennium, from the first professed agnostics such as Protagoras (fifth century BCE) to the last pagan thinkers. The Platonists’ Academy at Athens was not finally closed down until 529 CE, by the Emperor Justinian.

That longstanding tradition of moral philosophy is an invaluable legacy of ancient Mediterranean civilisation. It has prompted several contemporary secular thinkers, faced with the moral vacuum left by the decline of Christianity since the late 1960s, to revive ancient schools of thought. Stoicism, founded in Athens by the Cypriot Zeno in about 300 BCE, has advocates. Self-styled Stoic organisations on both sides of the Atlantic offer courses, publish books and blogposts, and even run an annual Stoic Week. Some Stoic principles underlay Dale Carnegie’s self-help classic How to Stop Worrying and Start Living (1948). He recommended Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations to its readers. But authentic ancient Stoicism was pessimistic and grim. It denounced pleasure. It required the suppression of emotions and physical appetites. It recommended the resigned acceptance of misfortune, rather than active engagement with the fine-grained business of everyday problem-solving. It left little room for hope, human agency or constructive repudiation of suffering.

Less familiar is the recipe for happiness ( eudaimonia ) advocated by Aristotle, yet it has much to be said for it. Outside of philosophy departments, where neo-Aristotelian thinkers such as Philippa Foot and Rosalind Hursthouse have championed his virtue ethics as an alternative to utilitarianism and Kantian approaches, it is not as well known as it should be. At his Lyceum in Athens, Aristotle developed a model for the maximisation of happiness that could be implemented by individuals and whole societies, and is still relevant today. It became known as ‘peripatetic philosophy’ because Aristotle conducted philosophical debates while strolling in company with his interlocutors.

The fundamental tenet of peripatetic philosophy is this: the goal of life is to maximise happiness by living virtuously, fulfilling your own potential as a human, and engaging with others – family, friends and fellow citizens – in mutually beneficial activities. Humans are animals, and therefore pleasure in responsible fulfilment of physical needs (eating, sex) is a guide to living well. But since humans are advanced animals, naturally inclining to live together in settled communities ( poleis ), we are ‘political animals’ ( zoa politika ). Humans must take responsibility for their own happiness since ‘god’ is a remote entity, the ‘unmoved mover’ who might maintain the universe’s motion but has neither any interest in human welfare, nor any providential function in rewarding virtue or punishing immorality. Yet purposively imagining a better, happier life is feasible since humans have inborn abilities that allow them to promote individual and collective flourishing. These include the inclinations to ask questions about the world, to deliberate about action, and to activate conscious recollection.

Aristotle’s optimistic, practical recipe for happiness is ripe for rediscovery. It offers to the human race facing third-millennial challenges a unique combination of secular, virtue-based morality and empirical science, neither of which seeks answers in any ideal or metaphysical system beyond what humans can perceive by their senses.

B ut what did Aristotle mean by ‘happiness’ or eudaimonia ? He did not believe it could be achieved by the accumulation of good things in life – including material goods, wealth, status or public recognition – but was an internal, private state of mind. Yet neither did he believe it was a continuous sequence of blissful moods, because this could be enjoyed by someone who spent all day sunbathing or feasting. For Aristotle, eudaimonia required the fulfilment of human potentialities that permanent sunbathing or feasting could not achieve. Nor did he believe that happiness is defined by the total proportion of our time spent experiencing pleasure, as did Socrates’ student Aristippus of Cyrene.

Aristippus evolved an ethical system named ‘hedonism’ (the ancient Greek for pleasure is hedone ), arguing that we should aim to maximise physical and sensory enjoyment. The 18th-century utilitarian Jeremy Bentham revived hedonism in proposing that the correct basis for moral decisions and legislation was whatever would achieve the greatest happiness for the greatest number. In his manifesto An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), Bentham actually laid out an algorithm for quantitative hedonism, to measure the total pleasure quotient produced by any given action. The algorithm is often called the ‘hedonic calculus’. Bentham spelled out the variables: how intense is the pleasure? How long will it last? Is it an inevitable or only possible result of the action I am considering? How soon will it happen? Will it be productive and give rise to further pleasure? Will it guarantee no painful consequences? How many people will experience it?

Bentham’s disciple, John Stuart Mill, pointed out that such ‘quantitative hedonism’ did not distinguish human happiness from the happiness of pigs, which could be provided with incessant physical pleasures. So Mill introduced the idea that there were different levels and types of pleasure. Bodily pleasures that we share with animals, such as the pleasure we gain from eating or sex, are ‘lower’ pleasures. Mental pleasures, such as those we derive from the arts, intellectual debate or good behaviour, are ‘higher’ and more valuable. This version of hedonist philosophical theory is usually called prudential hedonism or qualitative hedonism.

Train yourself to be the best possible version of yourself until you do the right thing habitually, on autopilot

There are few philosophers advocating hedonist theories today, but in the public understanding, when ‘happiness’ is not defined as the possession of a set of ‘external’ or ‘objective’ good things such as money and career success, it describes a subjective hedonistic experience – a transient state of elation. The problem with both such views, for Aristotle, is that they neglect the importance of fulfilling one’s potential. He cites approvingly the primordial Greek maxim that nobody can be called happy until he is dead: nobody wants to end up believing on his deathbed that he didn’t fulfil his potential. In her book The Top Five Regrets of the Dying (2011), the palliative nurse Bronnie Ware describes exactly the hazards that Aristotle advises us to avoid. Dying people say: ‘I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.’ John F Kennedy summed up Aristotelian happiness thus: ‘the exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence in a life affording them scope’.

For Aristotle insisted that happiness is constituted by something greater from and different to an accumulation of agreeable experiences. To be happy, we need to sustain constructive activities that we believe are goal-directed. This requires conscious analysis of our goals and conduct, and practising ‘virtue ethics’, by ‘living well’. It requires being nurtured effectively to develop your intellectual and physical capacities, and identify your potential (Aristotle had strong views on education), and also training yourself to be the best possible version of yourself until you do the right thing habitually, on autopilot. If you deliberately respond in a friendly way to everyone you encounter, you will begin to do so unconsciously, making yourself and others happier.

Historically, of course, many philosophers, such as Egoists, have questioned whether virtue is inherently desirable. But, since the mid-20th century, others rehabilitated virtue ethics and focused intensively on Aristotle’s ideas: unfortunately, this academic interest has yet to achieve any real public presence in broader culture in the way that Stoicism has.

S ome thinkers today distinguish between two sub-categories of virtue: between virtues such as courage, honesty and integrity, which affect your own and your community’s happiness; and ‘benevolence virtues’ such as kindness and compassion, which benefit others but are less obviously likely to gratify the agent. But Aristotle, for whom self-liking is necessary to virtue, argues that virtues do have intrinsic benefits, a view he shares with Socrates, the Stoics and the Victorian philosopher Thomas Hill Green. For part of his life, Aristotle lived in the Macedonian court tyrannised by the decadent and ruthless Philip II, whose lieutenants and concubines resorted to plots, extortion and murder to further their self-advantage. He knew what an immoral person looks like, and that such people were often subjectively miserable, despite the outward trappings of wealth and success. In the Nicomachean Ethics , he wrote (all translations my own):

Nobody would call a man ideally happy if he has not got a particle of courage nor of temperance nor of decency nor of good sense, but is afraid of the flies that flutter by him, cannot refrain from any of the most outrageous actions in order to gratify a desire to eat or to drink, and ruins his dearest friends for the sake of a penny …

Aristotle says that if happiness is not god-sent, ‘then it comes as the result of a goodness, along with a learning process, and effort’. Every human being can practise a way of life that will make him happier. Aristotle is not offering a magic wand to erase all threats to happiness. There are indeed some qualifications to the universal capacity for pursuing happiness. He accepts that there are certain kinds of advantage that you either have or you don’t. If you have the bad luck to have been born very low down the socio-economic ladder, or have no children or other family or loved ones, or are extremely ugly, your circumstances, which you can’t avoid, as he puts it, ‘taint’ delight. It is harder to achieve happiness. But not impossible. You do not need material possessions or physical strength or beauty to start exercising your mind in company with Aristotle, since the way of life he advocates concerns a moral and psychological excellence rather than one that lies in material possessions or bodily splendour. There are, he acknowledges, even more difficult obstacles: having children or friends who are completely depraved is one such obstacle. Another – which Aristotle saves until last and elsewhere implies is the most difficult problem any human can ever face – is the loss of fine friends in whom you have invested effort, or especially the loss of children, through death.

Yet, potentially, even people poorly endowed by nature or who have experienced terrible bereavements can live a good life. It is possible to undergo even apparently unendurable disasters and still live well: ‘even in adversity goodness shines through, when someone endures repeated and severe misfortune with patience; this is not owing to insensibility but from generosity and greatness of soul.’ In this sense, Aristotle’s is a deeply optimistic moral system. And it has practical relevance to ‘everyone’, implied by Aristotle’s inclusive use of the first personal plural: ‘This sort of philosophy is different from most other types of philosophy, since we are not asking what goodness is for the sake of knowing what it is, but with the aim of becoming good, without which our enquiry would be useless.’ In fact, the only way to be a good person is to do good things and treat people with fairness recurrently.

Aristotle insists that individuals who want to treat others fairly need to love themselves

Friendships are important to the Aristotelian, and adopting virtue ethics need not disrupt your life. An Aristotelian goal is moral self-sufficiency so that you are invulnerable to psychological manipulation, but he recognises that even the most self-sufficient person’s life is enhanced by having friends, and writes brilliantly on different types of relationship, from marriage or its equivalents to reciprocal cooperation between co-workers and fellow citizens. We might be able to cope alone, but why would we ever choose isolation? Moreover, you need no ‘natural talent’ at virtue, indeed Aristotle says that we are not born either good or bad. Nor is it ever too late: you can decide to retrain yourself morally at any point in your life. Most appealing of all, Aristotle insists that individuals who want to treat others fairly need to love themselves . There is no room for self-hatred, self-flagellation or self-deprivation in his humane system. Aristotle saw long before Sigmund Freud that our biological instincts are natural rather than morally despicable. This makes his ethics compatible with modern psychoanalysis.

An innovative Aristotelian idea is that supposedly reprehensible emotions – even anger and vengefulness – are indispensable to a healthy psyche. In this respect, Aristotle’s philosophy contrasts with the Stoic view that, for example, anger is irrational, and a form of temporary madness that should be eliminated. It’s just that such emotions need to be present in the right amount, the ‘middle’ or ‘mean’. Sexual desire, since humans are animals, is excellent in proportion. Either excessive or insufficient sexual appetite is conducive to unhappiness. Anger is also essential to a flourishing personality. An apathetic individual who never gets angry will not stand up for herself or her dependents when appropriate, and can’t achieve happiness. Yet anger in excess or with the wrong people is a vice.

Aristotle’s ethics are inherently flexible. There are no strict doctrines. Intention is always a crucial gauge of right behaviour: he writes penetratingly about the problems that arise when intended altruistic ends require immoral means. But every ethical situation is different. One person might jump on a train without a ticket because he is rushing to see a child who is in hospital; another might methodically dodge fares when she’s commuting to a well-paid job. Aristotle thought that general principles are important, but without taking into account the specific circumstances, especially intention, general principles can mislead. This is why he distrusted fixed penalties. He believed that the principle of equity needed to be integral to the judiciary, which is why some Aristotelians call themselves ‘moral particularists’. Each dilemma requires detailed engagement with the nuts and bolts of its particulars. When it comes to ethics, the devil really can be in the detail.

Politically speaking, a basic education in Aristotelianism could benefit humanity as a whole. Aristotle is positive about democracy, with which he finds fewer faults than other constitutions. Unlike his elitist tutor Plato, who was skeptical about the intelligence of the lower classes, Aristotle believed that the greatest experts on any given topic (eg zoology, of which he is the acknowledged founding father) are likely to be those who have accumulated experience of that topic (eg farmers, bird-catchers, shepherds and fishermen), however low their social status; scholarship must be informed by what they say. The trust that Aristotle felt in humanity’s general good sense enabled him to conceive a prototype of the ‘smart mob’ – a group that, rather than behaving in the loutish manner often associated with crowds, draws on universally distributed intelligence to behave with maximum efficiency. The idea, introduced by Howard Rheingold in Smart Mobs (2003), was anticipated in Aristotle’s Politics : where many people come together to deliberate, and become ‘a single person with many feet and many hands and many senses, so also it becomes one personality as regards the moral and intellectual faculties’.

A ristotle was the first philosopher to make explicit the distinction between doing wrong by omission and by commission . Not doing something when it is right to do it can have just as bad effects as a misdemeanour. This vital ethical principle has ramifications for the way in which we assess public figures. We do ask whether politicians have ever slipped up. But how often do we ask what they have not done with their power and influence to improve societal wellbeing? We do not ask enough what politicians, business leaders, presidents of universities and funding councils have failed to do, the initiatives that they have never launched, thus abnegating the duties of leadership. Aristotle was also clear that rich people who do not use a significant proportion of their wealth to help others are unhappy (because they are not acting according to the virtuous mean between fiscal irresponsibility and financial meanness). But they are also guilty of injustice by omission.

Aristotle is a utopian. He imagines the possibility that everyone will one day be able to realise his potential and make full use of all his faculties (the distinctive ‘Aristotelian principle’ according to the political philosopher John Rawls). Aristotle envisages a futuristic world in which technological advances would render human labour unnecessary. He remembers the mythical craftsmen Daedalus and Hephaestus, who constructed robots that worked to order: ‘for if every tool could perform its own work when ordered, or by seeing what to do in advance, like the statues of Daedalus in the story, or the automatic tripods of Hephaestus … if shuttles could weave like this, and plectrums strum harps of their own accord, master-craftsmen would have no need of assistants and masters no need of slaves’. It is almost as if he anticipated modern developments in artificial intelligence.

Aristotle’s political theory is flexible. You can be a capitalist or socialist, a businesswoman or a charity worker, vote for (almost) any political party, and still be a consistent Aristotelian. However, Aristotelian capitalists need to find indigence among their fellow citizens intolerable. Aristotle knew that humans come into conflict when commodities are scarce: ‘poverty is the parent of revolution and crime’. In his insistence on grounding political theory in humanity’s basic needs, Aristotle conceived the most advanced economic ideas ever to have appeared in his time, which was why Karl Marx admired him. Aristotle agrees with the recommendation in Plato’s Laws that gross inequality in assets owned by citizens produces divisive litigation and revolting obsequiousness towards the super-rich. Yet Aristotelian socialists need to acknowledge that extending compulsory public ownership to domestic accommodation does not work. People look after things because they enjoy the sense of private ownership, and because the things have value for them; both these qualities are diluted if shared with others. Aristotle thinks that ‘everybody loves a thing more if it has cost him trouble’.

Scientists and classicists agree: Aristotle would be an environmental campaigner today

A climate-change denier could find no encouragement in Aristotle. As a natural scientist who believed in meticulous research based on repeated acts of empirical observation and rigorous examination of hypotheses, he would be alarmed at the current evidence of human-caused environmental damage. The first reference to the extinction of a species by human activity (over-fishing) occurs in Aristotle’s The History of Animals . By seeing humans as animals, he effected a transformation in the ethical relationship between us and our material environment that has unlimited significance. His commitment to living planned lives in a deliberated way, taking long-term and total responsibility for our physical survival as well as our mental happiness, would, scientists and classicists agree, make him an environmental campaigner today. Only humans have moral agency, and therefore, as co-inhabitants of planet Earth with an astounding number of plants and animals, have the unique responsibility for conservation. But humans also have the capacity, because of their unique mental endowment, to cause terrible damage: as Aristotle said, drawing a chilling distinction, a bad man can do 10,000 times more harm than an animal.

The applicability of Aristotle’s holistic ethical and scientific outlook to our 21st-century problems such as theocracy and pollution prompts the question of why is there so little public awareness of his ideas. One is certainly his much-cited prejudices against women and slaves. He was a well-to-do male householder, and in his Politics he endorses slavery in the case of Greeks enslaving non-Greeks, and pronounces that women are incapable of reasoned deliberation. Yet he would have entertained reasoned arguments to the contrary, if backed up by empirical evidence. In every field of knowledge, he argued that all beliefs must be perpetually open to adjustment: ‘medicine has been improved by being altered from the ancestral system, and gymnastic training, and in general all the arts and faculties’. The laws the Greeks used to live by ‘were too simple and uncivilised’: he cites as examples the obsolete practices of purchasing wives and bearing of arms by citizens. He insists that law-codes need revision, ‘because it is impossible that the structure of the state can have been framed correctly for all time in relation to all its details’.

Yet the most important reason why Aristotle is so unfamiliar is that his surviving works are advanced treatises, written in specialist academic language for his colleagues and students. In fact, he did write several famous works for the public, in accessible, flowing prose that encouraged many thousands of ancient Greeks and Romans, over 10 centuries, to become practising virtue ethicists. They included peasant farmers and cobblers as well as kings and statesmen. This is because, as Themistius, one of the greatest ancient commentators on Aristotle, insisted, he was simply ‘more useful to the mass of people’ than other thinkers. The same still holds. The philosopher Robert J Anderson wrote in 1986: ‘There is no ancient thinker who can speak more directly to the concerns and anxieties of contemporary life than can Aristotle. Nor is it clear that any modern thinker offers as much for persons living in this time of uncertainty.’

One of the reasons why Stoicism is enjoying a revival today is that it gives concrete answers to moral questions. Aristotle’s ethical writings, however, contain few explicit instructions about how to act. Aristotelians need to take full responsibility in deciding what is the right way to behave and in repeatedly exerting their own judgment. The chief benefit that Aristotle can bestow on us today, which makes him so useful and practically applicable, is his alternative conception of ‘happiness’. It cannot be acquired by pleasurable experiences but only by identifying and realising our own potential, moral and creative, in our specific environments, with our particular family, friends and colleagues, and helping others to do so. We need to review both what we choose to do and what we avoid doing, because wrongs caused by omission can be just as destructive as those we commit. This involves embracing emotional impulses but also ensuring that we are using them as guides to what is good rather than letting them dictate our actions. And we need to do these thing continuously, since cultivating virtue, and the happiness that comes with this approach to life, can never be anything less than a lifelong goal.

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

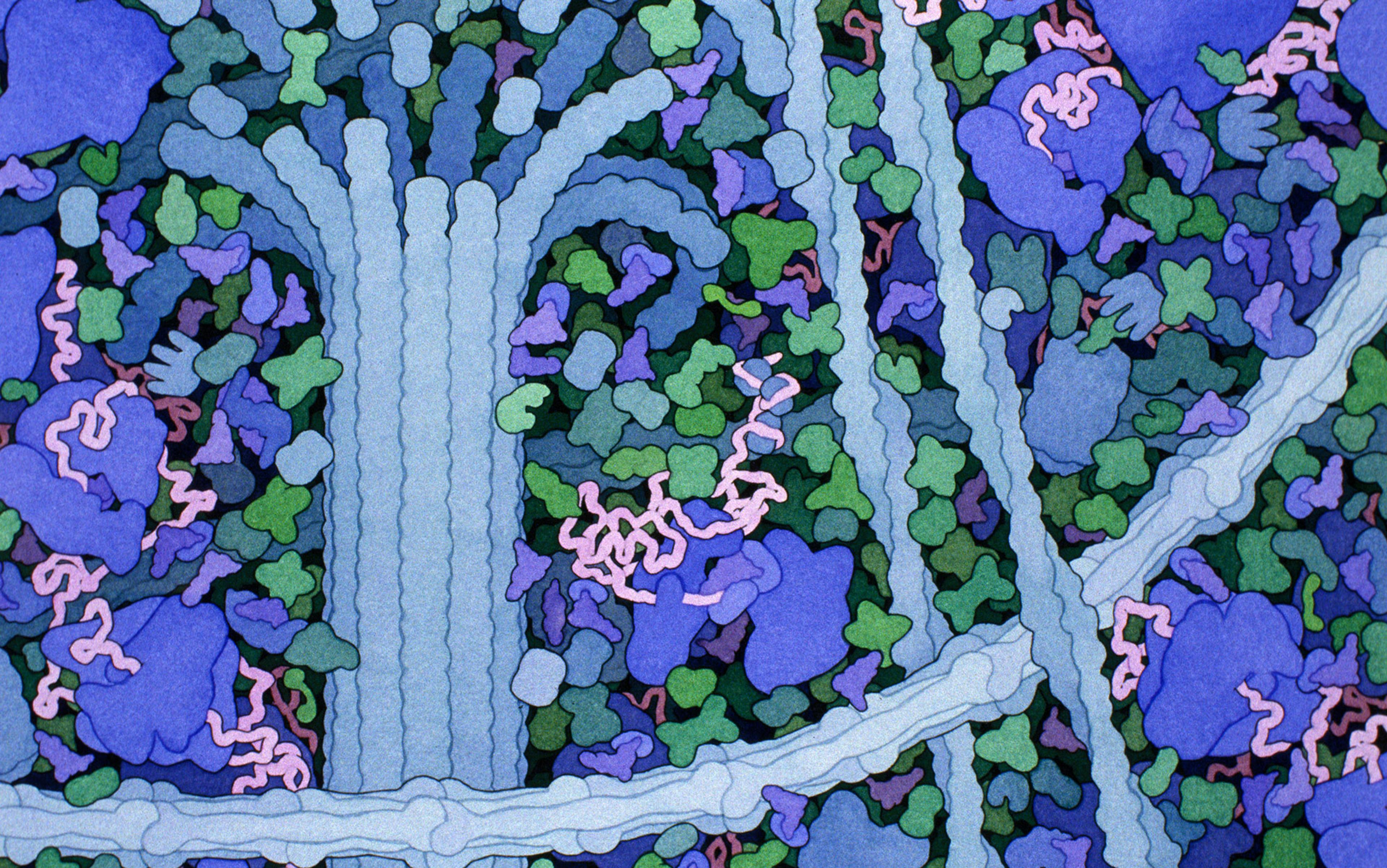

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Stories and literature

Terrifying vistas of reality

H P Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror stories, was a philosopher who believed in the total insignificance of humanity

Sam Woodward

The dangers of AI farming

AI could lead to new ways for people to abuse animals for financial gain. That’s why we need strong ethical guidelines

Virginie Simoneau-Gilbert & Jonathan Birch

A man beyond categories

Paul Tillich was a religious socialist and a profoundly subtle theologian who placed doubt at the centre of his thought

Public health

It’s dirty work

In caring for and bearing with human suffering, hospital staff perform extreme emotional labour. Is there a better way?

Susanna Crossman

6.2 Self and Identity

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Apply the dilemma of persistence to self and identity.

- Outline Western and Eastern theological views of self.

- Describe secular views of the self.

- Describe the mind-body problem.

Today, some might think that atomism and Aristotle’s teleological view have evolved into a theory of cells that resolves the acorn-oak tree identity problem. The purpose, or ergon, of both the acorn and the oak tree are present in the zygote, the cell that forms when male and female sex cells combine. This zygote cell contains the genetic material, or the instructions, for how the organism will develop to carry out its intended purpose.

But not all identity problems are so easily solved today. What if the author of this chapter lived in a house as a child, and years later, after traveling in the highly glamorous life that comes with being a philosopher, returned to find the house had burned down and been rebuilt exactly as it had been. Is it the same home? The generic questions that center on how we should understand the tension between identity and persistence include:

- Can a thing change without losing its identity?

- If so, how much change can occur without a loss of identity for the thing itself?

This section begins to broach these questions of identity and self.

The Ship of Theseus

Consider the following thought experiment. Imagine a wooden ship owned by the hero Theseus. Within months of launching, the need to replace decking would be evident. The salt content of sea water is highly corrosive. Accidents can also happen. Within a common version of the thought experiment, the span of one thousand years is supposed. Throughout the span, it is supposed that the entire decking and wooden content of the ship will have been replaced. The name of the ship remains constant. But given the complete change of materials over the assumed time span, in what sense can we assert that the ship is the same ship? We are tempted to conceptualize identity in terms of persistence, but the Ship of Theseus challenges the commonly held intuition regarding how to make sense of identity.

Similarly, as our bodies develop from zygote to adult, cells die and are replaced using new building materials we obtain though food, water, and our environment. Given this, are we the same being as we were 10 or 20 years ago? How can we identify what defines ourselves? What is our essence? This section examines answers proposed by secular and religious systems of belief.

Write Like a Philosopher

Watch the video “ Metaphysics: Ship of Theseus ” in the series Wi-Phi Philosophy . You will find five possible solutions for making sense of the thought experiment. Pick one solution and explain why the chosen solution is the most salient. Can you explain how the strengths outweigh the stated objections—without ignoring the objections?

Judeo-Christian Views of Self

The common view concerning identity in Judeo-Christian as well as other spiritual traditions is that the self is a soul. In Western thought, the origin of this view can be traced to Plato and his theory of forms. This soul as the real self solves the ship of Theseus dilemma, as the soul continuously exists from zygote or infant and is not replaced by basic building materials. The soul provides permanence and even persists into the afterlife.

Much of the Christian perspective on soul and identity rested on Aristotle’s theory of being, as a result of the work of St. Thomas Aquinas . Aquinas, a medieval philosopher, followed the Aristotelian composite of form and matter but modified the concept to fit within a Christianized cosmology. Drawing upon portions of Aristotle’s works reintroduced to the West as a result of the Crusades, Aquinas offered an alternative philosophical model to the largely Platonic Christian view that was dominant in his day. From an intellectual historical perspective, the reintroduction of the Aristotelian perspective into Western thought owes much to the thought of Aquinas.

In Being and Essence , Aquinas noted that there was a type of existence that was necessary and uncaused and a type of being that was contingent and was therefore dependent upon the former to be brought into existence. While the concept of a first cause or unmoved mover was present within Aristotle’s works, Aquinas identified the Christian idea of God as the “unmoved mover.” God, as necessary being, was understood as the cause of contingent being. God, as the unmoved mover, as the essence from which other contingent beings derived existence, also determined the nature and purpose driving all contingent beings. In addition, God was conceived of as a being beyond change, as perfection realized. Using Aristotelian terms, we could say that God as Being lacked potentiality and was best thought of as that being that attained complete actuality or perfection—in other words, necessary being.

God, as the ultimate Good and Truth, will typically be understood as assigning purpose to the self. The cosmology involved is typically teleological—in other words, there is a design and order and ultimately an end to the story (the eschaton ). Members of this tradition will assert that the Divine is personal and caring and that God has entered the narrative of our history to realize God’s purpose through humanity. With some doctrinal exception, if the self lives the good life (a life according to God’s will), then the possibility of sharing eternity with the Divine is promised.

Think Like a Philosopher

Watch this discussion with Timothy Pawl on the question of eternal life, part of the PBS series Closer to the Truth , “ Imagining Eternal Life ”.

Is eternal life an appealing prospect? If change is not possible within heaven, then heaven (the final resting place for immortal souls) should be outside of time. What exactly would existence within an eternal now be like? In the video, Pawl claimed that time has to be present within eternity. He argued that there must be movement from potentiality to actuality. How can that happen in an eternity?

Hindu and Buddhist Views of Self

Within Hindu traditions, atman is the term associated with the self. The term, with its roots in ancient Sanskrit, is typically translated as the eternal self, spirit, essence, soul, and breath (Rudy, 2019). Western faith traditions speak of an individual soul and its movement toward the Divine. That is, a strong principle of individuation is applied to the soul. A soul is born, and from that time forward, the soul is eternal. Hinduism, on the other hand, frames atman as eternal; atman has always been. Although atman is eternal, atman is reincarnated. The spiritual goal is to “know atman” such that liberation from reincarnation ( moksha ) occurs.

Hindu traditions vary in the meaning of brahman . Some will speak of a force supporting all things, while other traditions might invoke specific deities as manifestations of brahman . Escaping the cycle of reincarnation requires the individual to realize that atman is brahman and to live well or in accordance with dharma , observing the code of conduct as prescribed by scripture, and karma , actions and deeds. Union of the atman with brahman can be reach though yoga, meditation, rituals, and other practices.

Buddha rejected the concept of brahman and proposed an alternate view of the world and the path to liberation. The next sections consider the interaction between the concepts of Atman (the self) and Brahman (reality).

The Doctrine of Dependent Origination

Buddhist philosophy rejects the concept of an eternal soul. The doctrine of dependent origination , a central tenet within Buddhism, is built on the claim that there is a causal link between events in the past, the present, and the future. What we did in the past is part of what happened previously and is part of what will be.

The doctrine of dependent origination (also known as interdependent arising) is the starting point for Buddhist cosmology. The doctrine here asserts that not only are all people joined, but all phenomena are joined with all other phenomena. All things are caused by all other things, and in turn, all things are dependent upon other things. Being is a nexus of interdependencies. There is no first cause or prime mover in this system. There is no self—at least in the Western sense of self—in this system (O’Brien 2019a).

The Buddhist Doctrine of No Self ( Anatman )

One of many distinct features of Buddhism is the notion of anatman as the denial of the self. What is being denied here is the sense of self expressed through metaphysical terms such as substance or universal being. Western traditions want to assert an autonomous being who is strongly individuated from other beings. Within Buddhism, the “me” is ephemeral.

Listen to the podcast “ Graham Priest on Buddhism and Philosophy ” in the series Philosophy Bites.

Suffering and Liberation

Within Buddhism, there are four noble truths that are used to guide the self toward liberation. An often-quoted sentiment from Buddhism is the first of the four noble truths . The first noble truth states that “life is suffering” ( dukkha ).

But there are different types of suffering that need to be addressed in order to understand more fully how suffering is being used here. The first meaning ( dukkha-dukkha ) is commensurate with the ordinary use of suffering as pain. This sort of suffering can be experienced physically and/or emotionally. A metaphysical sense of dukkha is viparinama-dukkha . Suffering in this sense relates to the impermanence of all objects. It is our tendency to impose permanence upon that which by nature is not, or our craving for ontological persistence, that best captures this sense of dukkha. Finally, there is samkhara-dukkha , or suffering brought about through the interdependency of all things.

Building on an understanding of “suffering” informed only by the first sense, some characterize Buddhism as “life is suffering; suffering is caused by greed; suffering ends when we stop being greedy; the way to do that is to follow something called the Eightfold Path” (O’Brien 2019b). A more accurate understanding of dukkha within this context must include all three senses of suffering.

The second of the noble truths is that the cause of suffering is our thirst or craving ( tanha ) for things that lack the ability to satisfy our craving. We attach our self to material things, concepts, ideas, and so on. This attachment, although born of a desire to fulfill our internal cravings, only heightens the craving. The problem is that attachment separates the self from the other. Through our attachments, we lose sight of the impermanence not only of the self but of all things.

The third noble truth teaches that the way to awakening ( nirvana ) is through a letting go of the cravings. Letting go of the cravings entails the cessation of suffering ( dukkha ).

The fourth truth is founded in the realization that living a good life requires doing, not just thinking. By living in accordance with the Eightfold Path, a person may live such that “every action of body, mind, and speech” are geared toward the promotion of dharma.

Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths

Part of the BBC Radio 4 series A History of Ideas , this clip is narrated by Steven Fry and scripted by Nigel Warburton.

The Five Aggregates

How might the self ( atman ) experience the world and follow a path toward liberation? Buddhist philosophy posits five aggregates ( skandhas ), which are the thoughtful and iterative processes, through which the self interacts with the world.

- Form ( rupa ): the aggregate of matter, or the body.

- Sensation ( vedana ): emotional and physical feelings.

- Perception ( samjna ): thinking, the processing of sense data; “knowledge that puts together.”

- Mental formation ( samskara ): how thoughts are processed into habits, predispositions, moods, volitions, biases, interests, etc. The fourth skandhas is related to karma, as much of our actions flow from these elements.

- Consciousness ( vijnana ): awareness and sensitivity concerning a thing that does not include conceptualization.

Although the self uses the aggregates, the self is not thought of as a static and enduring substance underlying the processes. These aggregates are collections that are very much subject to change in an interdependent world.

Secular Notions of Self

In theology, continuity of the self is achieved through the soul. Secular scholars reject this idea, defining self in different ways, some of which are explored in the next sections.

Bundle Theory

One of the first and most influential scholars in the Western tradition to propose a secular concept of self was Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776). Hume formed his thoughts in response to empiricist thinkers’ views on substance and knowledge. British philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) offered a definition of substance in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In Book XXIII, Locke described substance as “a something, I know not what.” He asserted that although we cannot know exactly what substance is, we can reason from experience that there must be a substance “standing under or upholding” the qualities that exist within a thing itself. The meaning of substance is taken from the Latin substantia , or “that which supports.”

If we return to the acorn and oak example, the reality of what it means to be an oak is rooted in the ultimate reality of what it means to be an oak tree. The ultimate reality, like the oak’s root system, stands beneath every particular instance of an oak tree. While not every tree is exactly the same, all oak trees do share a something, a shared whatness, that makes an oak an oak. Philosophers call this whatness that is shared among oaks a substance.

Arguments against a static and enduring substance ensued. David Hume’s answer to the related question of “What is the self?” illustrates how a singular thing may not require an equally singular substance. According to Hume, the self was not a Platonic form or an Aristotelian composite of matter and form. Hume articulated the self as a changing bundle of perceptions. In his Treatise of Human Nature (Book 1, Part IV), Hume described the self as “a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.”

Hume noted that what has been mistaken for a static and enduring self was nothing more than a constantly changing set of impressions that were tied together through their resemblance to one another, the order or predictable pattern (succession) of the impressions, and the appearance of causation lent through the resemblance and succession. The continuity we experience was not due to an enduring self but due to the mind’s ability to act as a sort of theater: “The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations” (Hume 1739, 252).

Which theories of self—and substance—should we accept? The Greek theories of substance and the theological theories of a soul offer advantages. Substance allows us to explain what we observe. For example, an apple, through its substance, allows us to make sense of the qualities of color, taste, the nearness of the object, etc. Without a substance, it could be objected that the qualities are merely unintelligible and unrelated qualities without a reference frame. But bundle theory allows us to make sense of a thing without presupposing a mythical form, or “something I know not what!” Yet, without the mythical form of a soul, how do we explain our own identities?

Anthropological Views

Anthropological views of the self question the cultural and social constructs upon which views of the self are erected. For example, within Western thought, it is supposed that the self is distinct from the “other.” In fact, throughout this section, we have assumed the need for a separate and distinct self and have used a principle of continuity based on the assumption that a self must persist over time. Yet, non-Western cultures blur or negate this distinction. The African notion of ubuntu , for example, posits a humanity that cannot be divided. The Nguni proverb that best describes this concept is “umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” sometimes translated as “a person is a person through other persons” (Gade 2011). The word ubuntu is from the Zulu language, but cultures from southern Africa to Tanzania, Kenya, and Democratic Republic of the Congo all have words for this concept. Anthropological approaches attempt to make clear how the self and the culture share in making meaning.

The Mind as Self

Many philosophers, Western and non-Western, have equated the self to the mind. But what is the mind? A monist response is the mind is the brain. Yet, if the mind is the brain, a purely biological entity, then how do we explain consciousness? Moreover, if we take the position that the mind is immaterial but the body is material, we are left with the question of how two very different types of things can causally affect the other. The question of “How do the two nonidentical and dissimilar entities experience a causal relationship?” is known as the mind-body problem. This section explores some alternative philosophical responses to these questions.

Physicalism

Reducing the mind to the brain seems intuitive given advances in neuroscience and other related sciences that deepen our understanding of cognition. As a doctrine, physicalism is committed to the assumption that everything is physical. Exactly how to define the physical is a matter of contention. Driving this view is the assertion that nothing that is nonphysical has physical effects.

Listen to the podcast “ David Papineau on Physicalism ” in the series Philosophy Bites.

Focus on the thought experiment concerning what Mary knows. Here is a summary of the thought experiment:

Mary is a scientist and specializes in the neurophysiology of color. Strangely, her world has black, white, and shades of gray but lacks color (weird, but go with it!). Due to her expertise, she knows every physical fact concerning colors. What if Mary found herself in a room in which color as we experience it is present? Would she learn anything? A physicalist must respond “no”! Do you agree? How would you respond?

John Locke and Identity

In place of the biological, Locke defined identity as the continuity lent through what we refer to as consciousness. His approach is often referred to as the psychological continuity approach, as our memories and our ability to reflect upon our memories constitute identity for Locke. In his Essay on Human Understanding , Locke (as cited by Gordon-Roth 2019) observed, “We must consider what Person stands for . . . which, I think, is a thinking intelligent Being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider it self as itself, the same thinking thing in different times and places.” He offered a thought experiment to illustrate his point. Imagine a prince and cobbler whose memories (we might say consciousness) were swapped. The notion is far-fetched, but if this were to happen, we would assert that the prince was now the cobbler and the cobbler was now the prince. Therefore, what individuates us cannot be the body (or the biological).

John Locke on Personal Identity

Part of the BBC Radio 4 series A History of Ideas , this clip is narrated by Gillian Anderson and scripted by Nigel Warburton.

The Problem of Consciousness

Christof Koch (2018) has said that “consciousness is everything you experience.” Koch offered examples, such as “a tune stuck in your head,” the “throbbing pain from a toothache,” and “a parent’s love for a child” to illustrate the experience of consciousness. Our first-person experiences are what we think of intuitively when we try to describe what consciousness is. If we were to focus on the throbbing pain of a toothache as listed above, we can see that there is the experiencing of the toothache. Curiously, there is also the experiencing of the experiencing of the toothache. Introspection and theorizing built upon first-person inspections affords vivid and moving accounts of the things experienced, referred to as qualia .

An optimal accounting of consciousness, however, should not only explain what consciousness is but should also offer an explanation concerning how consciousness came to be and why consciousness is present. What difference or differences does consciousness introduce?

Listen to the podcast “ Ted Honderich on What It Is to Be Conscious ,” in the series Philosophy Bites.

Rene Descartes and Dualism

Dualism , as the name suggests, attempts to account for the mind through the introduction of two entities. The dualist split was addressed earlier in the discussion of substance. Plato argued for the reality of immaterial forms but admitted another type of thing—the material. Aristotle disagreed with his teacher Plato and insisted on the location of the immaterial within the material realm. How might the mind and consciousness be explained through dualism?

Mind Body Dualism

A substance dualist, in reference to the mind problem, asserts that there are two fundamental and irreducible realities that are needed to fully explain the self. The mind is nonidentical to the body, and the body is nonidentical to the mind. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) offered a very influential version of substance dualism in his 1641 work Meditations on First Philosophy. In that work, Descartes referred to the mind as a thinking thing ( res cogitans ) and the body as an extended nonthinking thing ( res extensa ). Descartes associated identity with the thinking thing. He introduced a model in which the self and the mind were eternal.

Behaviorism

There is a response that rejects the idea of an independent mind. Within this approach, what is important is not mental states or the existence of a mind as a sort of central processor, but activity that can be translated into statements concerning observable behavior (Palmer 2016, 122). As within most philosophical perspectives, there are many different “takes” on the most correct understanding. Behaviorism is no exception. The “hard” behaviorist asserts that there are no mental states. You might consider this perspective the purist or “die-hard” perspective. The “soft” behaviorist, the moderate position, does not deny the possibility of minds and mental events but believes that theorizing concerning human activity should be based on behavior.

Before dismissing the view, pause and consider the plausibility of the position. Do we ever really know another’s mind? There is some validity to the notion that we ought to rely on behavior when trying to know or to make sense of the “other.” But if you have a toothache, and you experience myself being aware of the qualia associated with a toothache (e.g., pain, swelling, irritability, etc.), are these sensations more than activities? What of the experience that accompanies the experience?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Nathan Smith

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Philosophy

- Publication date: Jun 15, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/6-2-self-and-identity

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

16 Aristotle on Memory and the Self

- Published: November 1995

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This essay argues that Aristotle’s view of memory is more like that of the modern psychologist than that of a modern philosopher; he is more interested in accurately delineating different kinds of memory than in discussing philosophical problems of memory. The short treatise On Memory and Recollection is considered a treatise on memory and loosely associated phenomenon and recollection. It is suggested that this work is better regarded as a treatise on two kinds of memory.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.