Essay on Good Citizen

Students are often asked to write an essay on Good Citizen in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Good Citizen

Defining a good citizen.

A good citizen is someone who respects others and their property. They are involved in their community and work to make it a better place.

Characteristics of a Good Citizen

Good citizens are responsible and respectful. They obey laws, pay taxes, and help their neighbors. They also participate in community activities.

The Importance of Being a Good Citizen

Being a good citizen is important for a healthy society. It encourages respect, kindness, and cooperation. It also helps to create a positive environment for everyone.

250 Words Essay on Good Citizen

The essence of a good citizen.

Being a good citizen, an often understated role, is a crucial aspect of any functioning society. It transcends the mere act of abiding by the law and delves into the realm of moral and social responsibilities.

Understanding the Role

A good citizen understands the intricate balance of rights and duties. They are aware of their fundamental rights but do not overlook their duties. They contribute to the community, respect diversity, and promote social harmony. They are the pillars of democracy, ensuring the government’s accountability by actively participating in the electoral process.

Embracing Social Responsibility

A good citizen is a socially responsible individual. They contribute to society by volunteering, helping others, and working towards the betterment of the community. They are environmentally conscious and strive to protect and preserve natural resources. They understand that the actions of today will shape the world of tomorrow.

Upholding Moral Responsibility

In addition to social responsibilities, a good citizen upholds moral responsibilities. They are honest, trustworthy, and respect the rights and beliefs of others. They stand against injustice, not just for themselves, but for others as well. They foster a sense of unity and mutual respect in the society.

In conclusion, a good citizen is an amalgamation of many qualities – law-abiding, socially and morally responsible, and an active participant in the democratic process. They are the backbone of a flourishing society and play a pivotal role in shaping a prosperous nation.

500 Words Essay on Good Citizen

Introduction: the concept of a good citizen.

A good citizen is a cornerstone of any thriving society, embodying the values, norms, and principles that bind a community together. The concept of a good citizen has evolved over time, reflecting the changing social, cultural, and political contexts. However, core elements such as participation, respect for laws, and social responsibility remain constant.

Active Participation in Society

One of the hallmarks of a good citizen is active participation in societal affairs. This includes voting, volunteering, engaging in civic discourse, and staying informed about local and global issues. Active participation ensures that citizens have a say in decisions affecting their lives, fostering a sense of ownership and commitment to societal wellbeing. It also promotes democratic values, as citizens who participate actively are more likely to uphold the principles of democracy such as fairness, equality, and justice.

Adherence to Laws and Respect for Authority

Adherence to laws and respect for authority are also integral to being a good citizen. Laws are designed to maintain order, protect citizens, and uphold societal values. A good citizen understands the importance of these laws and respects them, not out of fear of punishment, but out of respect for the collective good. This respect extends to authority figures who enforce these laws, recognizing their role in maintaining societal order.

Social Responsibility and Empathy

A good citizen is socially responsible, understanding that their actions have implications for others. This responsibility manifests in various ways, from environmental stewardship to advocating for social justice. Good citizens also demonstrate empathy, recognizing and respecting the diverse experiences, perspectives, and needs of others in their community. This empathy fuels a commitment to inclusivity, ensuring that all members of society feel valued and heard.

Continuous Learning and Self-Improvement

Finally, a good citizen is committed to continuous learning and self-improvement. They recognize that to contribute effectively to society, they must continually expand their knowledge, skills, and understanding. This commitment extends to understanding different cultures, histories, and political systems, fostering a more inclusive and tolerant society.

Conclusion: The Role of Good Citizens in Society

In conclusion, a good citizen is an active participant in society, respects laws and authority, is socially responsible, empathetic, and committed to continuous learning. These qualities contribute to a more cohesive, inclusive, and progressive society. Being a good citizen is not a passive role but requires ongoing effort and commitment. It is a role that each of us, as members of our respective societies, should strive to fulfill. By doing so, we can contribute to the betterment of our communities and, ultimately, the world.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Duties of a Good Citizen

- Essay on An Ideal Citizen

- Essay on American Diet

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Leadership Council

- Find People

- Fellowships

- Co-Curricular Program

- Student-led Events

- Recent Publications

- Gleitsman Program in Leadership and Social Change

- Hauser Leaders Program

What Does it Mean to Be a Good Citizen?

In this section.

"We don't agree on everything—but we do agree on enough that we can work together to start to heal our civic culture and our country." CPL's James Piltch asked people all over the US what it means to be a good citizen .

What Is a “Good Citizen”? a Systematic Literature Review

- Open Access

- First Online: 01 September 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Cristóbal Villalobos 23 ,

- María Jesús Morel 23 &

- Ernesto Treviño 24

Part of the book series: IEA Research for Education ((IEAR,volume 12))

11k Accesses

4 Citations

The concept of “good citizenship” has long been part of discussions in various academic fields. Good citizenship involves multiple components, including values, norms, ethical ideals, behaviors, and expectations of participation. This chapter seeks to discuss the idea of good citizenship by surveying the academic literature on the subject. To map the scientific discussion on the notion of good citizenship, a systematic review of 120 academic articles published between 1950 and 2019 is carried out. The review of the literature shows that good citizenship is broadly defined, incorporating notions from multiple fields, although these are mainly produced in Western countries with comparatively higher income levels. Additionally, although there is no single definition of good citizenship, the academic literature focuses on three components: the normative, active, and personal dimensions. This systematic review informs the estimation of citizenship profiles of Chap. 3 using the IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2016.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Values Education and the Making of “Good” Citizens in Australia

What are the Qualities of Good Citizenship in Post-genocide Rwanda? High School Teachers Speak Through a Q-Methodological Approach

Reflections on the Good Citizen

- Citizenship norms

- Good citizenship

- Systematic review

- International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS)

1 Introduction

The concept of “good citizenship” is part of a long-standing discussion in various academic fields, such as political science, education, sociology, anthropology, evolution, and history, among others. In addition, good citizenship involves various components, including values, norms, ethical ideals, behaviors, and expectations of participation. Finally, the idea of good citizenship is related to diverse contemporary issues, such as patterns of political participation, the meaning of democracy and human rights, the notion of civic culture, equal rights, and the role of technology in the digital era (Bolzendahl and Coffé 2009 ; Dalton 2008 ; Hung 2012 ; Noula 2019 ).

In this regard, the notion of good citizenship can be considered as a concept with three basic characteristics: multidisciplinary, multidimensional, and polysemic. Therefore, the definition of good citizenship is a topic of constant debate and academic discussion. This chapter seeks to discuss the idea of good citizenship, with the aim of contributing to the understanding of this phenomenon and its social, political, and educational implications. In this way, this chapter aims to map the academic discussion and literature regarding the notion of good citizenship, presenting the key debates about the limits and possibilities of this concept in the framework of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2016.

In order to organize this complex debate, we start from the premise that any notion of good citizenship is composed of the interaction of two definitions. On the one hand, it involves a certain notion of membership, that is, of belonging to a community. As Stokke ( 2017 ) shows, the definition of who is (and who is not) a citizen is, in itself, a subject of debate, since the definition of citizenship implies political, social, cultural, and legal components. On the other hand, the definition of good citizenship always implies a conceptual position regarding how citizens are expected to act and what they are expected to believe (the “public good” component). In this sense, the debate focuses on the types of behaviors that should be promoted and their ethical-political basis, which is highly dynamic depending on the cultural and historical context (Park and Shin 2006 ). Finally, in order to answer the question about the meaning of good citizenship, it is necessary to first decide who qualifies as a citizen, and how they are expected to behave.

Considering these objectives, the chapter is structured into five sections, including this introduction. The second section describes the systematic review methodology used to select the literature and analyze the discussion regarding the concept of good citizenship. The third and fourth sections describe the results of the analysis, mapping the main trends and characteristics of the academic discussion on good citizenship and exploring its different meanings. Finally, the fifth section presents the conclusions, focusing on the conceptual challenges and methodological limitations to be considered in future research.

2 Methodology

2.1 the systematic review.

We conducted a systematic review to map the academic discussion on good citizenship. This review seeks to identify, evaluate, and analyze the publications in relevant fields of study, in order to determine what has already been written on this topic, what works and what does not, and where new studies are needed (Petticrew and Roberts 2006 ). Through the definition of eligibility criteria, the systematic review is an explicit and reproducible methodology that allows for both an evaluation of the validity of the results of the selected studies (Higgins and Green 2011 ) and the objective valuation of evidence by summarizing and systematically describing the characteristics and results of scientific research (Egger 1997 ). In this regard, the systematic review, unlike other forms of literature review, allows for recognizing “gray” spaces in the literature, describing trends in academic research, and analyzing conceptual and methodological aspects of studies.

2.2 Procedure

The systematic review was conducted using five academic databases, including the main journals in the fields of education, social science, and the humanities. These databases are: (i) Journal Storage, JSTOR ( https://www.jstor.org ); (ii) Educational Resource Information Center, ERIC ( https://eric.ed.gov ); (iii) Springerlink ( https://link.springer.com ); (iv) WorldWideScience ( https://worldwidescience.org ); and (v) Taylor & Francis Group ( https://www.tandfonline.com ). For each search engine, the keywords used were: “good citizen” and “good citizenship.” Additionally, each search engine was tested with other related concepts, such as “citizenship norms,” “citizenship identities,” or “citizen norms.” The results showed that articles containing these latter concepts represented no more than 10% of new articles. For this reason, we decided to concentrate on the two keywords described above.

Considering the importance of these key concepts, the search was limited to those articles that contain these terms in the title, abstract, and/or full text. Of the five search engines, only two had the full-text option in the advanced search and only one allowed searching by keywords, then all results were filtered manually. The search was conducted from May to July 2019, obtaining 693 academic articles.

The search was restricted to those academic articles written in English and published between 1950 and 2019, as a way to study contemporary conceptualizations of good citizenship. We discarded letters to the editor, responses to articles, and book reviews. As a result, we obtained 693 articles to which, based on a full-text review, we applied an additional criterion, excluding those articles about other subjects or from other disciplines. Included in the first search exclusively for having the word “citizenship” in the abstract, there is a wide range of articles including studies on biology, entomology, and film studies. Similarly, with this search strategy we retrieved articles on a related topic but not specifically about citizenship (e.g., leadership, public participation, social values, and immigration), articles on the concept of corporate or organizational citizenship, and articles on social studies in the school curriculum and its contribution to the education of citizens.

After applying the abovementioned selection criteria, we analyzed the abstracts of the articles to verify that they were related to the general objective of the study. As a result, all articles were selected that sought (directly or indirectly) to answer the question, “what is a good citizen?” Specifically, this involved incorporating studies that: (i) study or analyze citizen norms in conceptual, historical, political, educational, or social terms; (ii) generate models or analytic frameworks that define variables or dimensions that should make up the concept of a good citizen; (iii) explore factors on how good citizenship occurs, studying the educational, institutional, and cultural factors that would explain this phenomenon; (iv) relate the expectations (or definitions) of a good citizen with other dimensions or aspects of the political or social behavior of the subjects. The research team, which was comprised of two reviewers, held a weekly discussion (six sessions in total) during which the selection criteria were discussed and refined. This analysis resulted in the selection of a total of 120 articles (see list in Appendix A ).

2.3 Analytical Strategy

The data collected in a systematic review may allow for a wide variety of studies, but the analysis depends on the purpose and nature of the data. Given that the review included quantitative and qualitative studies, as well as both theoretical and demonstrative essays, such heterogeneous literature does not allow for statistical analysis. As a result, the recommended methodology is to carry out a narrative synthesis and an analysis that focuses on relationships between different characteristics and the identification of gaps (Grant and Booth 2009 ; Petticrew and Roberts 2006 ).

The narrative synthesis is a process that allows for extracting and grouping the characteristics and results of each article included in the review (Popay et al. 2006 ), and can be divided into three steps: (i) categorization of articles; (ii) analysis of the findings within each category; and (iii) synthesis of the findings in the selected studies (Petticrew and Roberts 2006 ). The first step towards the narrative synthesis consisted of reading, coding, and tabulating the selected documents in order to describe their main characteristics. A set of categories was designed to classify documents according to four dimensions: general characteristics, purpose, methodology, and results.

To analyze these categories, we transformed data into a common numeric rubric and organized it for thematic analysis, using the techniques proposed by Popay et al. ( 2006 ). The first category was used to summarize the quantity and characteristics of the published studies, while the thematic analysis focused on systematically identifying the main, recurrent, and/or most important concepts of good citizenship.

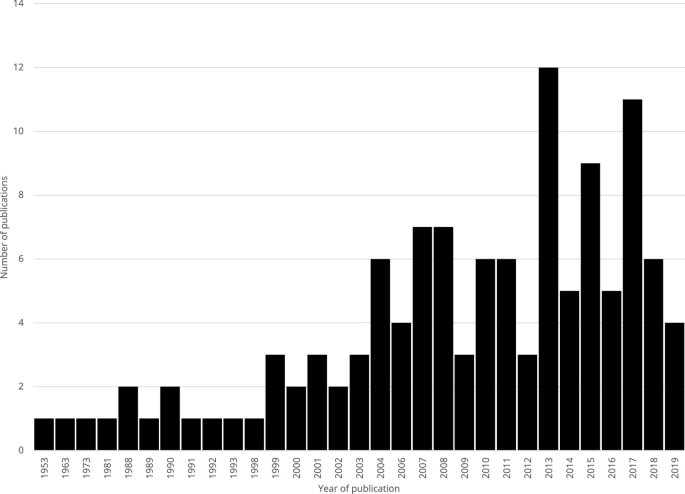

3 The Concept of Good Citizenship in Academia

Despite being a topic of interest for several decades, academic production on good citizenship tends to be concentrated in the second decade of the 21st century. Since 2009, there has been an explosive increase in the number of scientific papers published on this topic (Fig. 1 ). Although an important part of this growth may be due to the global pressures of academic capitalism to publish in academic journals (Slaughter and Rhoades 2009 ), it could also be the case that academic communities have cultivated a growing interest in studying this issue.

Academic papers by year of publication

Although few in number, the earliest articles published represent a landmark for the discussion. Thus, for example, the text of Almond and Verba ( 1963 ), which analyzes through interviews the perceptions of individuals in communities in five countries (United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, and Mexico) and highlights their different participation profiles, has been repeatedly cited in the discussion with 263 references (as of August 2019), according to Google Scholar. Another classic text is Ichilov and Nave ( 1981 ), which aims at understanding the different dimensions of citizenship by surveying young Israelis. To this end, it generates the following five criteria, which have been widely used in academic discussions: (i) citizenship orientation (affective, cognitive, or evaluative); (ii) nature of citizenship (passive or active); (iii) object of citizenship (political or non-political); (iv) source of demand (mandatory or voluntary); and (v) type of guidance (support principles or behavior).

The selected articles are geographically concentrated in two aspects: by institutional affiliation and by the location of their studies. Considering the institutional affiliation of the authors, 32.77% of the articles were produced in the United States, a figure that rises to more than 60% when the countries of Western Europe and Australia are included. This bias is maintained, although to a lesser extent, when analyzing the countries where the studies were carried out. Moreover, more than 50% of the studies were carried out in the United States, England, and the democracies of Western Europe. Africa (4.24%) and Latin America (2.54%) were the regions least represented in the studies. These characteristics, which tend to be representative of global academic production in the social sciences (Connell 2007 ), may encourage certain notions of good citizenship that are anchored in Anglo-Saxon traditions, such as the liberal conception of citizenship studied by Peled ( 1992 ), or more recently, the conception of active citizenship (Ke and Starkey 2014 ), both of which have had an important influence on academic discussion about good citizenship.

Finally, the third characteristic of academic production is related to the multiple research fields and diverse purposes of the studies that deal with the concept of good citizenship. Research on good citizenship is published in multiple disciplines. Of the articles included in the review, 82.29% are concentrated in three disciplines: education, political science, and sociology. However, there are also articles associated with journals of history, philosophy, anthropology, and law. Additionally, we identified six main objectives from the articles reviewed (Table 1 ). The most common objectives are related to bottom-up research, which seeks to gather information on how diverse populations understand good citizenship, and top-down research, which seeks to conceptualize and/or define the idea of good citizens based on conceptual, historical, or political analysis. In addition, there are a wide variety of studies that seek to explain good citizenship, as well as studies that use the idea of a good citizen to explain other behaviors, skills, or knowledge. In other words, in addition to being multidisciplinary, research on good citizenship has multiple purposes.

In sum, although the academic discussion on good citizenship has been mainly developed during the last two decades in the most industrialized Western countries, the academic research is a field of ongoing and open debate.

4 Understanding the Meaning of “Good Citizenship”

As an academic field with a lively ongoing discussion, the notion of good citizenship is associated with different sets of ideas or concepts. Some keywords were repeated at least three times in the articles reviewed (Table 2 ). Only those articles that used a keyword format were included. The most frequent concepts are related to education, norms, social studies, political participation, and democracy.

This indicates that, first, studies tend to associate good citizenship with civic norms and citizen learning, highlighting the formative nature of the concept. Second, studies that associate good citizenship with other dimensions of citizenship (such as knowledge or civic attitudes) or contemporary global problems (such as migration) are comparatively scarcer.

Another way to approach the concept of good citizenship is by analyzing the definitions proposed by the authors in the articles studied. Most of the articles propose characteristics or aspects of good citizenship (in 43.8% of the cases) that, instead of creating new definitions, are often based on existing political, non-political, liberal, or philosophical concepts. In this regard, many papers define good citizenship based on specific behaviors. In contrast, other authors (18.6%) refer to citizenship rules when it comes to voting or participating in politics, thereby seeking to relate the concept of the good citizen with a specific civic attitude—participation in elections. Finally, a large group of studies define good citizenship in terms of the values, virtues, or qualities of a good citizen (22.6%). Within the group of studies that propose new definitions, it is possible to identify two main categories: studies that propose types of citizenship, such as Dalton ( 2008 ), distinguishing between “duty” and “engaged” citizenship, and works, such as Westheimer and Kahne ( 2004 ), which differentiate between “personal responsible citizenship,” “justice-oriented citizenship,” and “participatory citizenship.”

Finally, the meaning of good citizenship can be analyzed by studying the variables used in the studies. Among the quantitative studies included in the review, only 28.3% use international surveys such as ICCS, the Center for Democracy and Civil Society (CDACS), the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), the United Citizenship, Involvement, Democracy (CID) Survey, and the European Social Survey (ESS). Each of these surveys contained a slightly different definition of good citizenship and the variables used to measure the concept (Table 3 ).

In general, the indicators used to measure citizenship in the different surveys share certain similarities. Variables associated with rules (such as obeying the law or paying taxes) are present in all surveys. Additionally, variables related to participation also have an important presence, especially (although not only) related to voting in national elections. To a lesser extent, surveys include variables related to solidarity (supporting people who are worse off than yourself) as well as attitudes related to critical thinking and civic culture (knowing the history of the country, thinking critically).

5 Discussion and Conclusions

The concept of good citizenship can be considered an umbrella term, which includes ethical, political, sociological, and educational aspects and discussions about who qualifies as a citizen and how they should act. The systematic review has shown that good citizenship is broadly defined, although these notions are mainly valued in Western countries with comparatively higher income levels.

For this reason, the definition of good citizenship used is, in large part, highly dependent on the research objective of the academic endeavor. In our case, the analysis is based on ICCS 2016, which defines good citizenship in relation to notions such as conventional citizenship, social movement citizenship, and personal responsibility citizenship (Köhler et al. 2018 ). The variables included in ICCS 2016 are related to the three main dimensions of good citizenship: normative, active, and personal. These three components of good citizenship have been essential in the academic discussion in the last seven decades, constituting the central corpus of the concept, although this definition does not incorporate current discussions on good citizenship, which focus, for example, on the notion of global citizenship (Altikulaç 2016 ) or the idea of digital citizenship (Bennett et al. 2009 ). These latter concepts are part of the ongoing debate on good citizenship, although it seems that more work is needed to better understand how these notions of citizenship are related to the ways in which individuals or groups in society relate to power and exercise it to shape the public sphere.

This systematic review has mapped the academic discussion to date on good citizenship. However, despite its usefulness, this review has a number of limitations. Firstly, it summarizes and analyzes the academic discussion, ignoring the gap between the scientific debate on good citizenship and the social discussion related to this subject. Secondly, it focuses on English-language literature, which may result in a bias towards publications produced in Western countries. In spite of these limitations, the review allows us to study the process of defining the concept of good citizenship, and to identify the main debates related to this notion, which is the central focus of this book.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture. Political attitudes and democracy in five nations . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Altikulaç, A. (2016). Patriotism and global citizenship as values: A research on social studies teacher candidates. Journal of Education and Practice, 7 (36), 26–33.

Google Scholar

Bennett, W. L., Wells, C., & Rank, A. (2009). Young citizens and civic learning: Two paradigms of citizenship in the digital age. Citizenship Studies, 13 (2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020902731116 .

Article Google Scholar

Bolzendahl, C., & Coffe, H. (2009). Citizenship beyond politics: The importance of political, civil and social rights and responsibilities among women and men. The British Journal of Sociology, 60 (4), 763–791.

Connell, R. W. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science . Sydney, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56 (1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x .

Egger, M. (1997). Meta-analysis: Potentials and promise. BMJ, 315 (7119), 1371–1374.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26 (2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x .

Higgins, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions . London, United Kingdom: The Cochrane Collaboration.

Hung, R. (2012). Being human or being a citizen? Rethinking human rights and citizenship education in the light of Agamben and Merleau-Ponty. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42 (1), 37–51.

Ichilov, O., & Nave, N. (1981). The Good Citizen as viewed by Israeli adolescents. Comparative Politics, 13 (3), 361–376.

Ke, L., & Starkey, H. (2014). Active citizens, good citizens, and insouciant bystanders: The educational implications of Chinese university students’ civic participation via social networking. London Review of Education, 12 (1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.12.1.06 .

Köhler, H., Weber, S., Brese, F., Schulz, W., & Carstens, R. (Eds.). (2018). ICCS 2016 user guide for the international database . Amsterdam, the Netherlands: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

Noula, I. (2019). Digital citizenship: Citizenship with a twist? Media@LSE Working Paper Series. London, United Kingdom: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Park, C.-M., & Shin, D. C. (2006). Do Asian values deter popular support for democracy in South Korea? Asian Survey, 46 (3), 341–361.

Peled, Y. (1992). Ethnic democracy and the legal construction of citizenship: Arab citizens of the Jewish state. The American Political Science Review, 86 (2), 432–443.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide . Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing.

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., et al. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme . Lancaster, United Kingdom: Lancaster University.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2009). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Markets, state, and higher education . Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Stokke, K. (2017). Politics of citizenship: Towards an analytical framework. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 71 (4), 193–207.

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41 (2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their research sponsors, the Center for Educational Justice ANID PIA CIE160007, as well as the Chilean National Agency of Research and Development through the grants ANID/FONDECYT N° 1180667, and ANID/FONDECYT N° 11190198.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centro de Estudios de Políticas y Prácticas en Educación (CEPPE-UC), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Cristóbal Villalobos & María Jesús Morel

Center UC for Educational Transformation, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Ernesto Treviño

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cristóbal Villalobos .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Educational Justice, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Centro de Medición MIDE UC, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Diego Carrasco

Centre for Political Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Ellen Claes

University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Kerry J. Kennedy

The following list of publications is the reviewed references for the systematic review conducted in this chapter.

Adler, S. A., & Kho, E. M. (2011). Educating citizens: A cross-cultural conversation. Journal of International Social Studies , 1 (2), 2–20.

Agbaria, A. K., & Katz-Pade, R. (2016). Human rights education in Israel: Four types of good citizenship. Journal of Social Science Education , 15 (2), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v15-i2-1455 .

Ahmad, I. (2017). Political science and the good citizen: The genealogy of traditionalist paradigm of citizenship education in the American school curriculum. Journal of Social Science Education , 16 (4), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v16-i4-1581 .

Ahmad, I. (2004). Islam, democracy and citizenship education: An examination of the social studies curriculum in Pakistan. Current Issues in Comparative Education , 7 (1), 39–49.

Ahrari, S., Othman, J., Hassan, S., Samah, B. A., & D’Silva, J. L. (2013). Role of social studies for pre-service teachers in citizenship education. International Education Studies , 6 (12), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n12p1 .

Alazzi, K., & Chiodo, J. J. (2008). Perceptions of social studies students about citizenship: A study of Jordanian middle and high school students. The Educational Forum , 72 (3), 271–280.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The obligation to participate. In The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations (pp. 161–179). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Altikulaç, A. (2016). Patriotism and global citizenship as values: A research on social studies teacher candidates. Journal of Education and Practice , 7 (36), 26–33.

Al-Zboon, M. S. (2014). Degree of student’s assimilation to the meaning of the term citizenships in the schools high grade basic level in Jordan. International Education Studies , 7 (2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n2p137 .

Angell, A. V. (1990). Civic attitudes of Japanese middle school students: Results of a pilot study [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council for the Social Studies, Anaheim, CA.

Atkinson, L. (2012). Buying into social change: How private consumption choices engender concern for the collective. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 644 (1), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212448366 .

Avery, P. G. (2003). Using research about civic learning to improve courses in the methods of teaching social studies. In J. J. Patrick, G. E. Hamot, & R. S. Leming (Eds.), Civic learning in teacher education: International perspectives on education for democracy in the preparation of teachers (Vol. 2, pp. 45–65). Bloomington, IN: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education.

Baron, J. (2010). Cognitive biases in moral judgments that affect political behavior. Synthese , 172 (1), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-009-9478-z .

Bass, L. E., & Casper, L. M. (2001). Differences in registering and voting between native-born and naturalized. Population Research and Policy Review , 20 (6), 483–511.

Bech, E. C., Borevi, K., & Mouritsen, P. (2017). A ‘civic turn’ in Scandinavian family migration policies? Comparing Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Comparative Migration Studies, 5 (1), 7.

Bickmore, K. (2001). Student conflict resolution, power. Curriculum Inquiry , 31 (2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00189 .

Bolzendahl, C., & Coffé, H. (2009). Citizenship beyond politics: The importance of political, civil and social rights and responsibilities among women and men. British Journal of Sociology , 60 (4), 763–791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01274.x .

Bolzendahl, C., & Coffé, H. (2013). Are “good” citizens “good” participants? Testing citizenship norms and political participation across 25 nations. Political Studies , 61 (SUPPL.1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12010 .

Boontinand, V., & Petcharamesree, S. (2018). Civic/citizenship learning and the challenges for democracy in Thailand. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 13 (1), 36–50.

Capers, I. B. (2018). Criminal procedure and the good citizen. Columbia Law Review , 118 (2), 653–712. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 .

Chávez, K. R. (2010). Border (in)securities: Normative and differential belonging in LGBTQ and immigrant rights discourse. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies , 7 (2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791421003763291 .

Chimiak, G. (2004). NGO activists and their model of the good citizen empirical evidence from Poland. Polish Sociological Review , (1), 33–47.

Chipkin, I. (2003). ‘Functional’ and ‘dysfunctional’ communities: The making of national citizens. Journal of Southern African Studies, 29 (1), 63–82.

Clarke, M. T. (2013). The virtues of republican citizenship in Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy. The Journal of Politics, 75 (2), 317–329.

Coffé, H., & Van Der Lippe, T. (2010). Citizenship norms in Eastern Europe. Social Indicators Research, 96 (3), 479–496.

Conger, K. H., & McGraw, B. T. (2008). Religious conservatives and the requirements of citizenship: Political autonomy. Perspectives on Politics, 6 (2), 253–266.

Connell, J. (2007). The Fiji Times and the good citizen: Constructing modernity and nationhood in Fiji. The Contemporary Pacific, 19 (1), 85–109.

Conover, P. J., Crewe, I. M., & Searing, D. D. (1991). The nature of citizenship in the United States and Great Britain: Empirical comments on theoretical themes. The Journal of Politics , 53 (3), 800–832. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131580 .

Cook, B. L. (2012). Swift-boating in antiquity: Rhetorical framing of the good citizen in fourth-century Athens. Rhetorica - Journal of the History of Rhetoric , 30 (3), 219–251. https://doi.org/10.1525/RH.2012.30.3.219 .

Costa, M. V. (2013). Civic virtue and high commitment schools. Theory and Research in Education , 11 (2), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878513485184 .

Crick, B. (2007). Citizenship: The political and the democratic author. British Journal of Educational Studies , 55 (3), 235–248.

Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies , 56 (1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x .

Damrongpanit, S. (2019). Factors affecting self-discipline as good citizens for the undergraduates of Chiang Mai University in Thailand: A multilevel path analysis. Universal Journal of Educational Research , 7 (2), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2019.070206 .

Damrongpanit, S. (2019). Factor structure and measurement invariance of the self-discipline model using the different-length questionnaires: Application of multiple matrix sampling. Universal Journal of Educational Research , 7 (1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2019.070118 .

Davidovitch, N., & Soen, D. (2015). Teaching civics and instilling democratic values in Israeli high school students: The duality of national and universal aspects. Journal of International Education Research (JIER) , 11 (1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v11i1.9093 .

Dekker, P. (2019). From pillarized active membership to populist active citizenship: The Dutch do democracy. Voluntas , 30 (1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00058-4 .

Denters, B., Gabriel, O. W., & Torcal, M. (2007). Norms of good citizenship. In J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, & A. Westholm (Eds.), Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: A comparative analysis (pp. 112–132). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203965757 .

Develin, R. (1973). The good man and the good citizen in Aristotle’s “Politics.” Phronesis , 18 (1), 71–79.

Dynneson, T. L., Gross, R. E., & Nickel, J. A. (1989). An exploratory survey of four groups of 1987 graduating seniors’ perceptions pertaining to (1) the Qualities of a Good Citizen, (2) the Sources of Citizenship Influence, and (3) the Contributions of Social Studies Courses and Programs of Study to Citizens . Stanford University, California: Citizenship Development Study Center. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 329481.

Eder, A. (2017). Cross-country variation in people’s attitudes toward citizens’ rights and obligations: A descriptive overview based on data from the ISSP Citizenship Module 2014. International Journal of Sociology , 47 (1), 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2017.1265309 .

Enu, D. B., & Eba, M. B. (2014). Teaching for democracy in Nigeria: A paradigm shift. Higher Education Studies , 4 (3), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v4n3p64 .

Ersoy, A. F. (2012). Mothers’ perceptions of citizenship, practices for developing citizenship conscience of their children and problems they encountered. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri , 12 (3), 2120–2124.

Fernández, C., & Jensen, K. K. (2017). The civic integrationist turn in Danish and Swedish school politics. Comparative Migration Studies , 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-017-0049-z .

Garver, E. (2010). Why can’t we all just get along: The reasonable vs. the rational according to Spinoza. Political Theory , 38 (6), 838–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591710378577 .

Goering, E. M. (2013). Engaging citizens: A cross cultural comparison of youth definitions of engaged citizenship. Universal Journal of Educational Research , 1 (3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2013.010306 .

Green, J., Steinbach, R., & Datta, J. (2012). The travelling citizen: Emergent discourses of moral mobility in a study of cycling in London. Sociology , 46 (2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511419193 .

Gutierrez, R. (2002). What can happen to auspicious beginnings: Historical barriers to ideal citizenship. The Social Studies , 93 (5), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377990209600166 .

Haas, M. E., Laughlin, M. A., Wilson, E. K., & Sunal, C. S. (2003, April). Promoting enlightened political engagement by using a citizenship scenario with teacher candidates and experienced teachers [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Hammett, D. (2018). Engaging citizens, depoliticizing society? Training citizens as agents for good governance. Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography , 100 (2), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2018.1433961 .

Hébert, M., & Rosen, M. G. (2007). Community forestry and the paradoxes of citizenship in Mexico: The cases of Oaxaca and Guerrero. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies , 32 (63), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/08263663.2007.10816914 .

Hoekstra, M. (2015). Diverse cities and good citizenship: How local governments in the Netherlands recast national integration discourse. Ethnic and Racial Studies , 38 (10), 1798–1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1015585 .

Hooghe, M., Oser, J., & Marien, S. (2016). A comparative analysis of ‘good citizenship’: A latent class analysis of adolescents’ citizenship norms in 38 countries. International Political Science Review , 37 (1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114541562 .

Hoskins, B., Saisana, M., & Villalba, C. M. H. (2015). Civic competence of youth in Europe: Measuring cross national variation through the creation of a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research , 123 (2), 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0746-z .

Hunter, E. (2013). Dutiful subjects, patriotic citizens, and the concept of “good citizenship” in Twentieth-Century Tanzania. Historical Journal , 56 (1), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X12000623 .

Ibrahimoğlu, Z. (2018). Who are good and bad citizens ? A story-based study with seventh graders. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research , 0 (0), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1523709 .

Ichilov, O. (1988). Citizenship orientation of two Israeli minority groups: Israeli-Arab and Eastern-Jewish youth. Ethnic Groups , 7 (2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1109/ultsym.1996.584088 .

Ichilov, O. (1988). Family politicization and adolescents’ citizenship orientations. Political Psychology , 431–444.

Ichilov, O., & Nave, N. (1981). “The good citizen” as viewed by Israeli adolescents. Comparative Politics , 13 (3), 361–376.

Jarrar, A. G. (2013). Positive thinking & good citizenship culture: From the Jordanian Universities students’ points of view. International Education Studies , 6 (4), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n4p183 .

Kariya, T. (2012). Is everyone capable of becoming a ‘Good Citizen’ in Japanese society? Inequality and the realization of the ‘Good Citizen’ Education. Multicultural Education Review , 4 (1), 119–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/23770031.2009.11102891 .

Ke, L., & Starkey, H. (2014). Active citizens, good citizens, and insouciant bystanders: The educational implications of Chinese university students’ civic participation via social networking. London Review of Education , 12 (1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.12.1.06 .

Kennelly, J. (2009). Good citizen/bad activist: The cultural role of the state in youth activism. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies , 31 (2–3), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714410902827135 .

Kennelly, J. (2011). Policing young people as citizens-in-waiting: Legitimacy, spatiality and governance. British Journal of Criminology , 51 (2), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azr017 .

Kuang, X., & Kennedy, K. J. (2018). Alienated and disaffected students: Exploring the civic capacity of ‘Outsiders’ in Asian societies. Asia Pacific Education Review , 19 (1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9520-2 .

Kwan Choi Tse, T. (2011). Creating good citizens in China: Comparing grade 7–9 school textbooks, 1997–2005. Journal of Moral Education , 40 (2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2011.568098 .

Lefrançois, D., Ethier, M. -A., & Cambron-Prémont, A. (2017). Making “good” or “critical” citizens: From social justice to financial literacy in the Québec Education Program. Journal of Social Science Education , 16 (4), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v16-i4-1698 .

Lehning, P. B. (2001). European citizenship: Towards a European identity? Law and Philosophy, 20 (3), 239–282.

Leung, Y. W., Yuen, T. W. W., Cheng, E. C. K., & Chow, J. K. F. (2014). Is student participation in school governance a “mission impossible”?. Journal of Social Science Education , 13 (4), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.2390/jsse-v13-i4-1363 .

Li, H., & Tan, C. (2017). Chinese teachers’ perceptions of the ‘good citizen’: A personally-responsible citizen. Journal of Moral Education , 46 (1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1277341 .

Liem, G. A. D., & Chua, B. L. (2013). An expectancy-value perspective of civic education motivation, learning and desirable outcomes. Educational Psychology , 33 (3), 276–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.776934 .

Long, D. H. (1990). Continuity and change in Soviet education under Gorbachev. American Educational Research Journal, 27 (3), 403–423.

Mara, G. M. (1998). Interrogating the identities of excellence: Liberal education and democratic culture in Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics”. Polity, 31 (2), 301–329.

Martin, L. A., & Chiodo, J. J. (2007). Good citizenship: What students in rural schools have to say about it. Theory and Research in Social Education , 35 (1), 112–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2007.10473328 .

Martin, L. A., & Chiodo, J. J. (2008). American Indian students speak out: What’s good citizenship? International Journal of Social Education , 23 (1), 1–26.

McGinnis, T. A. (2015). “A good citizen is what you’ll be”: Educating Khmer Youth for citizenship in a United States Migrant Education Program. Journal of Social Science Education , 14 (3), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.2390/jsse-v14-i3-1399 .

Meltzer, J. (2013). “Good citizenship” and the promotion of personal savings accounts in Peru. Citizenship Studies , 17 (5), 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2013.818382 .

Mills, S. (2013). “An instruction in good citizenship”: Scouting and the historical geographies of citizenship education. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers , 38 (1), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00500.x .

Morris, P., & Morris, E. (2000). Constructing the good citizen in Hong Kong: Values promoted in the school curriculum. Asia Pacific Journal of Education , 20 (1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/0218879000200104 .

Mosher, R. (2015). Speaking of belonging: Learning to be “good citizens” in the context of voluntary language coaching projects in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Journal of Social Science Education , 14 (3), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.2390/jsse-v14-i3-1395 .

Murphy, M. (2004, April). Current trends in civic education: An American perspective [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at the philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain Annual Meeting, Oxford, England.

Niemi, R. G., & Chapman, C. (1999). The civic development of 9th- through 12th-grade students in the United States: 1996. The National Center For Education Statistics , 1 (1), 39–41.

Nieuwelink, H., Ten Dam, G., & Dekker, P. (2019). Adolescent citizenship and educational track: a qualitative study on the development of views on the common good. Research Papers in Education , 34 (3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1452958 .

Nurdin, E. S. (2015). The policies on civic education in developing national character in Indonesia. International Education Studies , 8 (8), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n8p199 .

Orton, M. (2006). Wealth, citizenship and responsibility: The views of “better off” citizens in the UK. Citizenship Studies , 10 (2), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020600633218 .

Peled, Y. (1992). Ethnic democracy and the legal construction of citizenship: Arab citizens of the Jewish state. American Political Science Review, 86 (2), 432–443.

Perlmutter, O. W. (1953). Education, the good citizen, and civil religion. The Journal of General Education, 7 (4), 240–249.

Phillips, J. (2004). The relationship between secondary education and civic development: Results from two field experiments with inner city minorities. CIRCLE Working Papers , 14 (14), 1–8.

Prior, W. (1999). What it means to be a “good citizen” in Australia: Perceptions of teachers, students, and parents. Theory and Research in Social Education , 27 (2), 215–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.1999.10505879 .

Reichert, F. (2017). Young adults’ conceptions of ‘good’ citizenship behaviours: A latent class analysis. Journal of Civil Society , 13 (1), 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2016.1270959 .

Reichert, F. (2016). Who is the engaged citizen? Correlates of secondary school students’ concepts of good citizenship. Educational Research and Evaluation , 22 (5–6), 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2016.1245148 .

Russell, S. G., & Quaynor, L. (2017). Constructing citizenship in post-conflict contexts: The cases of Liberia and Rwanda. Globalisation, Societies and Education , 15 (2), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2016.1195723 .

Sasson-Levy, O. (2002). Constructing identities at the margins: Masculinities and citizenship in the Israeli army. The Sociological Quarterly , 43 (3), 357–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2002.tb00053.x .

Schoeman, S. (2006). A blueprint for democratic citizenship in South African public schools: African teacher’s perceptions of good citizenship. South African Journal of Education , 26 (1), 129–142.

Sim, J. B. Y. (2011). Social studies and citizenship for participation in Singapore: How one state seeks to influence its citizens. Oxford Review of Education , 37 (6), 743–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.635103 .

Siphai, S. (2015). Influences of moral, emotional and adversity quotient on good citizenship of Rajabhat Universitys Students in the Northeast of Thailand. Educational Research and Reviews , 10 (17), 2413–2421. https://doi.org/10.5897/err2015.2212 .

Stokke, K. (2017). Politics of citizenship: Towards an analytical framework. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift , 71 (4), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2017.1369454 .

Stuteville, R., & Johnson, H. (2016). Citizenship education in the United States: Perspectives reflected in state education standards. Administrative Issues Journal: Education, Practice, and Research , 6 (1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.5929/2016.6.1.7 .

Sumich, J. (2013). Tenuous belonging: Citizenship and democracy in Mozambique. Social Analysis, 57 (2), 99–116.

Sweeney, E. T. (1972). The A.F.L’.s good citizen, 1920–1940. Labor History , 13 (2), 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00236567208584201 .

Tan, C. (2008). Creating “good citizens” and maintaining religious harmony in Singapore. British Journal of Religious Education , 30 (2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200701830921 .

Terchek, R. J., & Moore, D. K. (2000). Recovering the political Aristotle: A critical response to Smith. American Political Science Review , 94 (4), 905–911. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586215 .

Thapan, M. (2006). ‘Docile’ bodies, ‘good’ citizens or ‘agential’ subjects? Pedagogy and citizenship in contemporary society. Economic and Political Weekly , 4195–4203.

Theiss-morse, E. (1993). Conceptualizations of good citizenship and political participation. Political Behavior , 15 (4), 355–380.

Thompson, L. A. (2004). Identity and the forthcoming Alberta social studies curriculum: A postcolonial reading. Canadian Social Studies , 38 (3), 1–11.

Tibbitts, F. (2001). Prospects for civics education in transitional democracies: Results of an impact study in Romanian classrooms. Intercultural Education , 12 (1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980124250 .

Tonga, D., & Keles, H. (2014). Evaluation of the citizenship consciousness of the 8th year students. Online Submission , 4 (2), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.13054/mije.14.10.4.2 .

Torres, M. (2006). Youth activists in the age of postmodern globalization: Notes from an ongoing project. Chapin Hall Working Paper. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Tupper, J. A., Cappello, M. P., & Sevigny, P. R. (2010). Locating citizenship: Curriculum, social class, and the “good” citizen. International Education Studies , 38 (3), 336–365. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n8p199 .

Van Deth, J. W. (2009). Norms of citizenship. The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior , (June 2018), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0021 .

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal , 41 (2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237 .

White, M. (2006). The dispositions of ‘good’ citizenship: Character, symbolic power and disinterest. Journal of Civil Society , 2 (2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448680600905882 .

Wilkins, C. (1999). Making ‘good citizens’: The social and political attitudes of PGCE students. Oxford Review of Education , 25 (1&2). https://doi.org/10.1080/030549899104224 .

Wong, K. L., Lee, C. K. J., Chan, K. S. J., & Kennedy, K. J. (2017). Constructions of civic education: Hong Kong teachers’ perceptions of moral, civic and national education. Compare , 47 (5), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1262756 .

Woolf, M. (2010). Another mishegas: Global citizenship. Frontiers. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad , 19 , 47–60.

Worku, M. Y. (2018). Perception of Ethiopian students and educators on the responsibility for good citizenship. Journal of International Social Studies , 8 (2), 103–120.

Yesilbursa, C. C. (2015). Turkish pre-service social studies teachers perceptions of “Good” citizenship. Educational Research and Reviews , 10 (5), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.5897/err2014.2058 .

Zamir, S., & Baratz, L. (2013). Educating “good citizenship” through bilingual children literature Arabic and Hebrew. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn) , 7 (4), 223. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v7i4.197 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA)

About this chapter

Villalobos, C., Morel, M.J., Treviño, E. (2021). What Is a “Good Citizen”? a Systematic Literature Review. In: Treviño, E., Carrasco, D., Claes, E., Kennedy, K.J. (eds) Good Citizenship for the Next Generation . IEA Research for Education, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75746-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75746-5_2

Published : 01 September 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75745-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75746-5

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Education Articles & More

How to inspire students to become better citizens, educators can help boost civic engagement among young people..

The political turmoil of the last few years has many of us worried about the future of our country and our planet.

But here’s the good news: Thanks to new trends in education, the next generation may be more engaged, thoughtful, respectful, and compassionate citizens.

Research suggests that the growing emphasis on social-emotional learning (SEL) in schools can lay the foundation for more active civic engagement among our youth. In a 2018 study of almost 2,500 students, researchers found that those with greater emotional and socio-cognitive skills—such as empathy, emotion regulation, and moral reasoning—reported higher civic engagement.

Among this group of eight to 20 year olds, being more empathic (more upset when others are treated unfairly) and more “future-oriented” (more aware of how decisions impact their future) predicted a host of important civic behaviors and attitudes: volunteering; helping friends, family, and neighbors; valuing political involvement (e.g., keeping up with current events and taking part in rallies); engaging in environmentally conscious behaviors; demonstrating social responsibility values; and prioritizing other civic skills like listening and summarizing conflicting views. In other words, students with certain SEL skills also seemed to be more oriented toward social, community, and political issues.

And when students help others and practice civic behaviors, they may feel better, too. In a recent one-week study of 276 college students, participants experienced greater well-being on days when they engaged in certain types of civic activities, like helping friends or strangers and caring for their environment by recycling and conserving resources. According to the researchers, these kind and helpful behaviors also seemed to be meeting young adults’ basic needs for autonomy, connectedness, and competence—to feel free, close to others, and capable.

By its nature, social-emotional learning can support the democratic structures and processes that raise up all voices in our schools, empowering students to be more engaged in their world. So how can we thoughtfully apply these skills in our own classrooms? Here are several research-based ideas and resources to consider.

1. Re-examine your disciplinary practices

Researcher Robert Jagers and his colleagues found that Black and Latino middle school students who perceived more democratic homeroom, classroom, and disciplinary practices had higher civic engagement, particularly when students perceived an equitable school climate.

Similarly, researcher Peter Levine argues that teachers who truly want to educate students about democracy face massive barriers if the school environment is “unjust or alienating.” Harsh, authoritarian, and less-inclusive climates can ultimately weaken their community engagement, turnout in elections, and trust in government .

More and more research suggests that exclusionary discipline (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) can be alienating and counterproductive, and restorative practices (strategies that focus on learning from mistakes and repairing relationships rather than punishing students) may offer a more humanizing, equitable, and respectful alternative. In this context, students come together to learn to navigate conflicts, process their feelings, and collaboratively problem-solve a way forward.

When reviewing disciplinary practices at your school, also consider the following: Who is being disciplined? How often, and why? (If your school is like many others in the U.S., your students of color are disproportionately disciplined for the same or similar infractions when compared to white students. How is your school addressing that difference?) Are preventive strategies your number-one priority (e.g., relationship and community building)? How do you model and practice communication strategies for resolving conflicts ?

2. Facilitate meaningful dialogue among diverse learners

Research suggests that students in an “open classroom climate,” one that grows out of respectful dialogue and exposure to varying opinions, tend to have greater civic knowledge, commitment to voting, and awareness of the role of conflict in a democracy.

But perhaps you don’t feel prepared to teach students how to discuss and resolve tensions—especially around charged topics like racism. You may want your classroom to feel like a “safe space,” but how, exactly, do you foster and sustain one?

Start by preparing yourself. We all have different comfort levels with conversations about race, and being uncomfortable doesn’t necessarily mean that we are unsafe (or shouldn’t venture into that territory). Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, has created the free online Let’s Talk handbook that can help you outline some of the vulnerabilities that make you feel less effective as a facilitator (along with your strengths!), and discover specific strategies for addressing strong emotions in your classroom.

More Resources

Not Light, But Fire , a new book by educator Matthew Kay, encourages teachers to be more focused and deliberate when discussing race in high school classrooms. Kay shares personal anecdotes coupled with practical strategies for facilitating meaningful classroom dialogue.

The Let’s Talk! handbook can help you navigate and understand your own uncomfortable emotions during heated conversations. It also features practical steps for leading reflective classroom discussions.

Learn the elements of compassionate listening , and seven ways to teach listening skills to elementary students . You can also adapt our Greater Good in Action Active Listening pair practice for children or teens in your classroom.

For example, when you sense confusion or denial of racism, this Teaching Tolerance tool recommends that you “ask questions anchored in class content or introduce accurate or objective facts for consideration.” Or, if students respond that they feel blamed, remind them that “racism is like a smog; we all breathe it in and are harmed by it. We may not have created the system, but we can do something about it.”

3. Use advisory time to encourage group cohesion and connectedness

If you value opportunities for meaningful dialogue, but think there isn’t time in your schedule for yet another priority, consider advisory or homeroom time in secondary schools (and classroom meetings in elementary schools). This time in the day or week can be thoughtfully structured for relationship and skill building. In this setting, students can learn how to actively participate in supportive dialogue with their peers over a sustained period of time.

In the Jagers study mentioned above, the featured homeroom routines included establishing social norms and contracts, group problem solving, and fun group activities to build connection and trust. For example, many teachers support their students in jointly creating a group “constitution” or agreement that highlights 1) the group’s values (e.g., responsibility, respect, fairness, and honesty) and 2) the concrete behaviors demonstrating those values. Further, students might lead or assist the teacher in proposing activities, like fostering a small class pet, developing solutions to pressing problems at school (e.g., creating a recycling program), or simply enjoying social time together (yoga in the gym or a “get to know you” game).

Of course, students can also share greetings, personal interests, and feelings with one another. My daughter’s high school “mentor” group (designed to include multiple ethnicities and viewpoints) meets daily and sticks together for four years. Every Wednesday morning, they check in with each other, share how they are feeling, and receive “support” and “resonance” from their peers and teacher-mentor, as needed—a wonderful opportunity for fostering empathy and a sense of belonging.

During advisory or circle time, many students across the country also plan to participate in service activities in their schools and communities, which is a great way to promote volunteerism and civic responsibility.

4. Feature engaging civics lessons, activities, and projects in your curriculum

Of course, there are plenty of opportunities for further civics education in social studies and history classes.

Teaching Tolerance’s website includes quizzes, videos, stories, and lessons for helping children to understand and value the voting process even though they aren’t active voters yet.

Facing History and Ourselves offers a plethora of ready-made lessons and resources for secondary teachers for discussion within the following units: Standing Up for Democracy , Identity and Community: An Intro to Sixth Grade Social Studies , and Universal Declaration of Human Rights . You may also be interested in exploring civic dilemmas .

The Morningside Center for Social Responsibility regularly features lessons on current issues, such as Overcoming Hate: A Circle on the Pittsburgh Synagogue Massacre or Caravan: Why Are People Leaving Their Homes? .

In the Action Civics program, for example, students “ learn politics by doing politics .” They identify an issue they care about (e.g., homelessness, teacher pay, the opioid crisis), research it, and design a plan of action to advocate for that issue at a local level. Project-based learning like this—that is experiential, situated in the real world, and powerfully linked to students’ interests—makes politics come alive for them.

There are a number of different teaching strategies and activities (debates, Socratic seminars , and mock trials, as well as the National Model United Nations ) that give students the opportunity to actively practice civic behaviors, attitudes, and values while learning more about social studies, history, and political science. Many of these approaches help students learn how to paraphrase main ideas, develop an evidence-based argument, and anticipate counter-arguments while they practice conducting themselves respectfully and professionally in a group context.

With these ideas and resources in mind, it’s time to revitalize civic learning in our schools, and SEL skills can help serve as the building blocks. When students actively practice these skills in their schools, they are likely to feel a stronger sense of personal agency in their communities and in the larger world. There may be no more meaningful work right now than supporting a thriving democracy and more informed, responsible, and caring student citizens.

About the Author

Amy L. Eva, Ph.D. , is the associate education director at the Greater Good Science Center. As an educational psychologist and teacher educator with over 25 years in classrooms, she currently writes, presents, and leads online courses focused on student and educator well-being, mindfulness, and courage. Her new book, Surviving Teacher Burnout: A Weekly Guide To Build Resilience, Deal with Emotional Exhaustion, and Stay Inspired in the Classroom, features 52 simple, low-lift strategies for enhancing educators’ social and emotional well-being.

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Zócalo Podcasts

The Many Ways to Be a Good Citizen

From the revolutionary era to today, "doing your part” has meant different things for different americans.

An unidentified woman from Cuba, one of the 196 people from 24 countries, reacts during naturalization ceremonies in Miami, July 1, 2009. Photo by J. Pat Carter/Associated Press.

Christine Woyshner

In clubs and associations, american “joiners” shaped a nation.

Stephen Kantrowitz

African americans asserted their citizenship long before the law backed them up.

Gary Scott Smith

Without a church, could a fledgling u.s. have survived how the country’s citizens made it possible.

Backers of Women’s Suffrage Compromised Perfection for the Sake of Progress

Kevin Boyle

From a bridge in selma, alabama, outrage fed action.

William A. Link

A “new and strange thing” for black students, after the civil war.

Beth Bailey

What is citizens’ service, in the era of the volunteer military.

The Kids Are All Right

May 1, 2017

The news these days is filled with images of citizens marching, protesting, and organizing on behalf of one cause or another. Americans, indeed, have organized since the founding of this nation; the visiting Frenchman Alexis d’Toqueville noted their propensity to do so in the 1830s. But in the past, unlike today, Americans relied on associations that spanned the nation to make social, political, and economic change across the nation and in local communities.

The period from the end of the Civil War to the mid-20th century was a particularly robust time of organized civic activism. There wasn’t a town, city, or hamlet that remained untouched by civic organizations. Voluntary associations were founded by people who were black, white, native-born, immigrant, men, and women—from the middle and the lower classes—in a variety of types: fraternals, veteran’s groups, women’s clubs, civic associations, study clubs, ethnic groups, and even secret societies, such as the Masons. In this “nation of joiners,” to borrow a phrase from eminent historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., the average person was able to unite with others in local face-to-face meetings as well as state and national conventions.

The work volunteers carried out affected local communities as well as national legislation. Both the National PTA and the Black Panthers, for example, worked to institute school lunches over the course of the 20th century. From America’s founding into the 1960s, clubs, organizations, and associations allowed the average citizen to meet others, make change, and learn important skills such as leadership and organizing.

Times have changed, and now most Americans no longer meet in these broadly-focused face-to-face groups, preferring to gather online, and focusing on single, though important, issues. Perhaps current resistance efforts in the public square can draw on the models of the national voluntary organizations of the past—with local, state, and national offices, modeled on the federal government—to achieve their goals.

Christine Woyshner is a professor of education at Temple University. She researches the history of American education, with a focus on civic voluntary organizations. She has authored or edited six books, including The National PTA, Race, and Civic Engagement, 1897-1970 (The Ohio State University Press, 2009).

During the Civil War African Americans didn’t just demand citizenship. Against rejection, denial, and insult, they redefined it.

When the Civil War began, free black people had good reason to wonder whether the United States of America was even a good idea: It was the land of the Fugitive Slave Law, which left them vulnerable to enslavement; of the Dred Scott decision, which denied them national citizenship; and of state laws and constitutions, North and South, that excluded them or even threatened them with enslavement. Yet when South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter and Lincoln called for volunteers, black men in cities across the free states assembled to volunteer their service.

They were refused, curtly and sometimes violently. The United States was a white man’s republic, and this was to be a white man’s war.

When the Union finally did come calling at the end of 1862, free black communities debated whether to participate. Some seized the opportunity to prove their worthiness and their patriotism, hoping to claim the citizenship they had long sought. Others urged a more defiant stand. Resist enlistment, they said, until the government promised equal pay, equal treatment, and black officers. But even those who chose to serve soon became dissidents as well, for the government soon broke its promise of equal pay. For more than a year, soldiers and their families protested, refusing to accept unequal wages. Many endured hardship. Some faced courts martial. A few were executed by their own army for their resistance.

These soldiers and protesters established African Americans’ claim to two kinds of citizenship—the citizenship of patriotic service, and the citizenship of principled dissent. With the first, they made it impossible to deny that African Americans participated in the destruction of slavery. With the second, they hitched that commitment to the principle of equality before the law. Constitutional amendments would soon write these ideas into the nation’s organic law. But African Americans were there first.

Stephen Kantrowitz teaches history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 and Ben Tillman and the Reconstruction of White Supremacy .

“In the six thousand years since the creation of the world,” founding father James Wilson declared, nothing like the American republic had ever been created. What made this fledging republic so special? According to Thomas Jefferson, the United States was “new under the sun” because it rejected the outdated ideology, allegiances, and patterns of the Old World. Prominent among these arrangements was the long-standing practice of establishing a church and supporting it with government revenues. By not having a national established church, the United States broke with 1450 years of Western tradition, stretching back to the Roman Emperor Constantine.

One reason Western nations had established churches was to ensure that their citizens obeyed the laws and followed traditional moral norms. The critical question then was: Could a republic that had no official, tax-supported church survive? Jefferson called this arrangement the “fair experiment,” and he and other founders insisted that the United States could flourish only if its citizens lived by high moral standards. As George Washington argued in his Farewell Address, religion and morality were “indispensable supports” of “political prosperity.”

Ordinary Americans, therefore, had a vital role to play in their new nation’s success. Although they fell short in many ways, most notably their treatment of Indians and the practice of slavery, their moral practices and commitment to the common good enabled their country to survive British, French, and Spanish challenges to undermine their autonomy. Through their participation in congregations, voluntary organizations, and government at the local level—and by caring for their neighbors—many Americans in the early national period put the needs of others before their own, and worked to help the poor, vulnerable, and sick. Their virtuous conduct, self-sacrifice, and compassion helped the United States become a great nation and serve as model of democracy and civic responsibility for other countries.