Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

How to realize immense promise of gene editing

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

Following the leak of a draft decision by the Supreme Court that would overturn Roe v. Wade, the Medical School’s Louise King discusses how the potential ruling might affect providers.

AP Photo/Alex Brandon

How a bioethicist and doctor sees abortion

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Her work touches questions we can answer and questions we can’t. But her main focus is elsewhere: ‘the patient in front of me.’

With the leak Monday of a draft decision by the Supreme Court that would overturn Roe v. Wade, the future of abortion in the U.S. has been a highly charged topic of conversation all week. Doctors are among those wondering what’s next. Louise King is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and a Brigham and Women’s Hospital physician whose practice includes abortion services. King, who is also the director of reproductive bioethics for the Center for Bioethics at the Medical School, spoke with the Gazette about ethical dimensions of abortion and how a ruling against Roe might affect providers.

Louise King

GAZETTE: In the U.S., abortion is framed in broad ethical terms: life versus death, privacy versus government intrusion, etc. From a medical ethics standpoint, what are the important concerns to be balanced on this issue?

KING: I frame the topic in the context of the patient in front of me. In other words, I look primarily to autonomy and beneficence in the context of doing good for the patient. That might mean upholding that person’s choice not to proceed with what is still a very dangerous proposition, namely carrying a pregnancy to term and delivering. If someone says to me, “I’m pregnant and do not wish to be pregnant,” for a multitude of reasons, I support that decision, because the alternative of carrying to term is risky. I want to protect that person’s bodily autonomy. From a reproductive justice standpoint, I want to support persons who have uteri in making decisions about when they wish to have a family, how they want that to look, whether they want to have a family at all, in expressing their sexuality, and in all kinds of different things.

I don’t believe that life begins at conception. Among the minority of people in this country who believe that’s the case, some are vocal and aggressive in imposing that belief on others, which may happen with this upcoming decision. But quite a number of students that I meet who believe life begins at conception still don’t believe that they have the right to impose that belief on others. To contextualize what we ask of persons with uteri when we make abortion illegal, it’s helpful to compare instances where we could ask people to undergo very risky procedures to help others. For example, we don’t demand that people give blood. It’s not a big deal and it could save lives every day, but we don’t demand that anybody donate blood or bone marrow. We don’t demand kidney donations, which are less risky than childbirth nowadays.

So we generally don’t ask one human being to give so completely of themselves to another, but we do so when it’s a pregnant person. That, I believe, does not comport with our ethics. But it also doesn’t fully address the concerns of persons who believe life begins at conception. They come to those beliefs honestly, but I think they have to explore them more deeply and figure out whether, even if true — do they hold up to the point where we require somebody to have a forced pregnancy to term? I would say, within my understanding of ethics, no.

“It’s not a big deal and it could save lives every day, but we don’t demand that anybody donate blood or bone marrow. We don’t demand kidney donations, which are less risky than childbirth nowadays.”

GAZETTE: Abortion is one of the most divisive issues in the country. Is the medical profession unified on it one way or another?

KING: That’s hard to say definitively. No study or survey exists to truly quantify this. The American Medical Association and the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists say that abortion is health care, and I agree. ACOG is very strong in their wording about supporting the right to access abortion. Unfortunately, only 14 percent of practicing OBGYNs provide abortion care. As a profession, our words and actions don’t match. I think there’s a multitude of reasons for that. One is the stigma associated with providing abortion care in some parts of the country.

I would guess that most providers feel similarly to the majority of Americans — that abortion is health care and should be available. While I’ve met some medical students and practicing physicians in all kinds of disciplines who feel strongly that abortion is unethical, the vast majority that I’ve spoken to feel as I feel: that it’s health care and should be provided.

GAZETTE: A big part of the debate over the decades has centered on viability. Is this an issue for science to determine? Is it an issue for society? Is it an issue for religion?

More like this

Softer language post-leak? Maybe, says Tribe, but ruling will remain an ‘iron fist’

Mothers of stillborns face prison in El Salvador

KING: I don’t think that science can tell us definitively when life begins. Life is a broad term and includes a variety of living entities. I don’t think that religion can define it because we have freedom of religion and religions see this differently. Rabbis will explain that in the Torah, it’s very clear that an embryo is simply an extension of a woman’s body, like a limb, and should not be considered another person until birth. The leaked decision presumes that one version of Christianity’s assessment of this prevails, which seems to violate our understanding of freedom of religion in this country.

Ultimately, “when life begins” isn’t the right question because it’s unanswerable. The question then must be: How do we as a society come up with a compromise that upholds the autonomous rights of the persons in front of us who may become pregnant, who may have excessive risks associated with a pregnancy, or who may simply not wish to be pregnant, that also observes whatever our society’s agreed-upon understanding is of when a protected entity exists.

I think Massachusetts absolutely gets it right. If you read the Roe Act : Abortion is allowed for any reason in the first and second trimesters, and then abortion for medical reasons or lethal fetal anomalies can extend into the third trimester with careful consideration between patient and medical teams. To me, that is an exceptionally well-thought-out compromise. This is a societal decision. It shouldn’t be made by a minority of persons based on their narrow definition of “when life begins.”

GAZETTE: If something like the leaked draft decision emerges, is there a potential for medical providers to get caught in the middle?

KING: Overturning Roe would turn the question over to the states. That would mean that those providers who exist within the states that are clearly going to go forward with legislation to outlaw abortion would be in dire situations. In Massachusetts, we could provide the care we’re already providing and would expect people to travel from out of state to us. I don’t think that the long-arm statutes would reach a provider here, that somebody could come after me from Texas if somebody traveled from Texas to me and I provided care. But if I traveled to Texas, for a conference, it might. Legal experts aren’t sure.

GAZETTE: Have you ever been threatened because you’ve offered abortions?

KING: I haven’t, but many of my colleagues have. I did my training in Texas, so I lived a long time in the South. I’ve not been threatened directly, but spoken sternly to by many people who disagreed with me. I mentioned earlier that there are plenty of people who believe life begins at conception but who do not feel they should impose their viewpoints on others — those are people I met in Texas and Louisiana. There are a lot of people like that, but they can’t speak up for fear of being ostracized. The sense that I have through all the conversations I’ve had over many years is that we are all talking past each other. You started off by saying this is a topic that divides our country, but it doesn’t. The vast majority of people are settled on having abortion as an option, having contraception as an option, and having sex education available. There’s a group of politicians who make it appear that we’re divided and build their political careers off of that. It’s incredibly disheartening and unethical for them to do so.

Share this article

You might like.

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

Nobel-winning CRISPR pioneer says approval of revolutionary sickle-cell therapy shows need for more efficient, less expensive process

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Ethics and Morality

Ethics and abortion, two opposing arguments on the morality of abortion..

Posted June 7, 2019 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Abortion is, once again, center stage in our political debates. According to the Guttmacher Institute, over 350 pieces of legislation restricting abortion have been introduced. Ten states have signed bans of some sort, but these are all being challenged. None of these, including "heartbeat" laws, are currently in effect. 1

Much has been written about abortion from a philosophical perspective. Here, I'd like to summarize what I believe to be the best argument on each side of the abortion debate. To be clear, I'm not advocating either position here; I'm simply trying to bring some clarity to the issues. The focus of these arguments is on the morality of abortion, not its constitutional or legal status. This is important. One might believe, as many do, that at least some abortions are immoral but that the law should not restrict choice in this realm of life. Others, of course, argue that abortion is immoral and should be illegal in most or all cases.

"Personhood"

Personhood refers to the moral status of an entity. If an entity is a person , in this particular sense, it has full moral status . A person, then, has rights , and we have obligations to that person. This includes the right to life. Both of the arguments I summarize here focus on the question of whether or not the fetus is a person, or whether or not it is the type of entity that has the right to life. This is an important aspect to focus on, because what a thing is determines how we should treat it, morally speaking. For example, if I break a leg off of a table, I haven't done anything wrong. But if I break a puppy's leg, I surely have done something wrong. I have obligations to the puppy, given what kind of creature it is, that I don't have to a table, or any other inanimate object. The issue, then, is what kind of thing a fetus is, and what that entails for how we ought to treat it.

A Pro-Choice Argument

I believe that the best type of pro-choice argument focuses on the personhood of the fetus. Mary Ann Warren has argued that fetuses are not persons; they do not have the right to life. 2 Therefore, abortion is morally permissible throughout the entire pregnancy . To see why, Warren argues that persons have the following traits:

- Consciousness: awareness of oneself, the external world, the ability to feel pain.

- Reasoning: a developed ability to solve fairly complex problems.

- Ability to communicate: on a variety of topics, with some depth.

- Self-motivated activity: ability to choose what to do (or not to do) in a way that is not determined by genetics or the environment .

- Self-concept : see themselves as _____; e.g. Kenyan, female, athlete , Muslim, Christian, atheist, etc.

The key point for Warren is that fetuses do not have any of these traits. Therefore, they are not persons. They do not have a right to life, and abortion is morally permissible. You and I do have these traits, therefore we are persons. We do have rights, including the right to life.

One problem with this argument is that we now know that fetuses are conscious at roughly the midpoint of a pregnancy, given the development timeline of fetal brain activity. Given this, some have modified Warren's argument so that it only applies to the first half of a pregnancy. This still covers the vast majority of abortions that occur in the United States, however.

A Pro-Life Argument

The following pro-life argument shares the same approach, focusing on the personhood of the fetus. However, this argument contends that fetuses are persons because in an important sense they possess all of the traits Warren lists. 3

At first glance, this sounds ridiculous. At 12 weeks, for example, fetuses are not able to engage in reasoning, they don't have a self-concept, nor are they conscious. In fact, they don't possess any of these traits.

Or do they?

In one sense, they do. To see how, consider an important distinction, the distinction between latent capacities vs. actualized capacities. Right now, I have the actualized capacity to communicate in English about the ethics of abortion. I'm demonstrating that capacity right now. I do not, however, have the actualized capacity to communicate in Spanish on this issue. I do, however, have the latent capacity to do so. If I studied Spanish, practiced it with others, or even lived in a Spanish-speaking nation for a while, I would likely be able to do so. The latent capacity I have now to communicate in Spanish would become actualized.

Here is the key point for this argument: Given the type of entities that human fetuses are, they have all of the traits of persons laid out by Mary Anne Warren. They do not possess these traits in their actualized form. But they have them in their latent form, because of their human nature. Proponents of this argument claim that possessing the traits of personhood, in their latent form, is sufficient for being a person, for having full moral status, including the right to life. They say that fetuses are not potential persons, but persons with potential. In contrast to this, Warren and others maintain that the capacities must be actualized before one is person.

The Abortion Debate

There is much confusion in the abortion debate. The existence of a heartbeat is not enough, on its own, to confer a right to life. On this, I believe many pro-lifers are mistaken. But on the pro-choice side, is it ethical to abort fetuses as a way to select the gender of one's child, for instance?

We should not focus solely on the fetus, of course, but also on the interests of the mother, father, and society as a whole. Many believe that in order to achieve this goal, we need to provide much greater support to women who may want to give birth and raise their children, but choose not to for financial, psychological, health, or relationship reasons; that adoption should be much less expensive, so that it is a live option for more qualified parents; and that quality health care should be accessible to all.

I fear , however, that one thing that gets lost in all of the dialogue, debate, and rhetoric surrounding the abortion issue is the nature of the human fetus. This is certainly not the only issue. But it is crucial to determining the morality of abortion, one way or the other. People on both sides of the debate would do well to build their views with this in mind.

https://abcnews.go.com/US/state-abortion-bans-2019-signed-effect/story?id=63172532

Mary Ann Warren, "On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion," originally in Monist 57:1 (1973), pp. 43-61. Widely anthologized.

This is a synthesis of several pro-life arguments. For more, see the work of Robert George and Francis Beckwith on these issues.

Michael W. Austin, Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

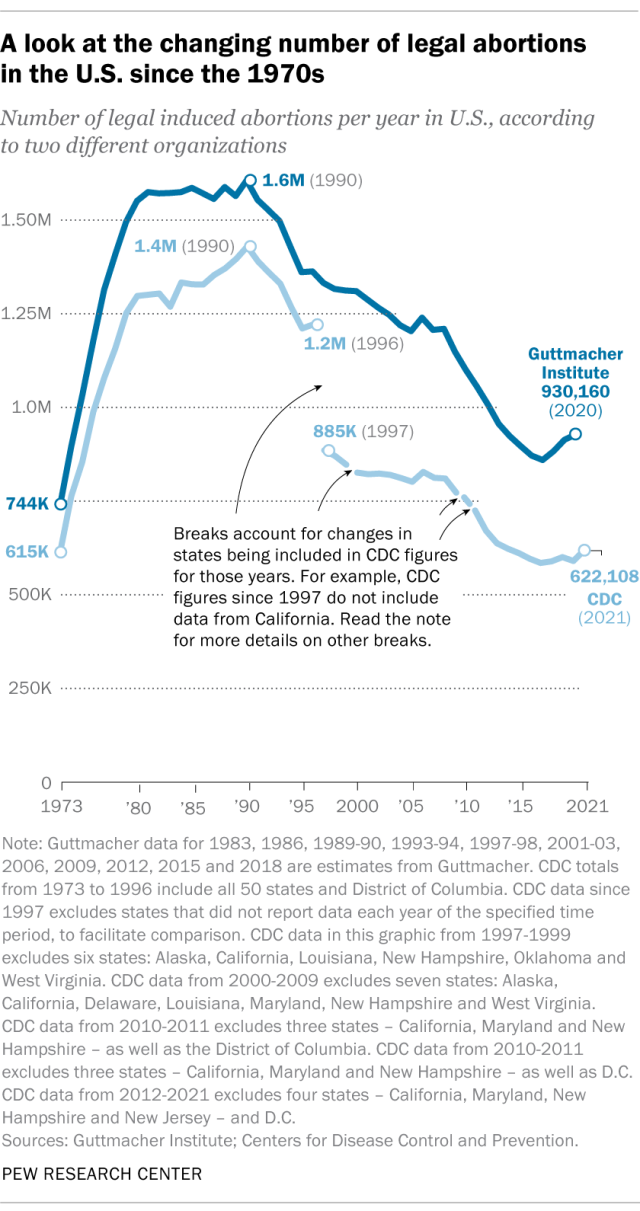

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

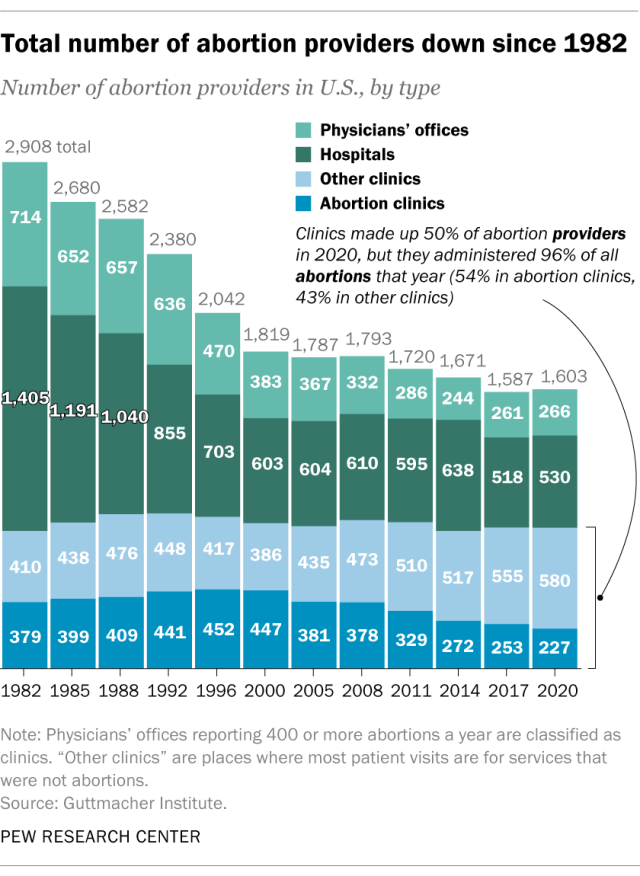

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.

In the District of Columbia, New York City (but not the rest of New York) and the 31 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to the CDC , 42% of all women who had abortions in 2021 were non-Hispanic Black, while 30% were non-Hispanic White, 22% were Hispanic and 6% were of other races.

Looking at abortion rates among those ages 15 to 44, there were 28.6 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic Black women in 2021; 12.3 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.4 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 9.2 abortions per 1,000 women of other races, the CDC reported from those same 31 states, D.C. and New York City.

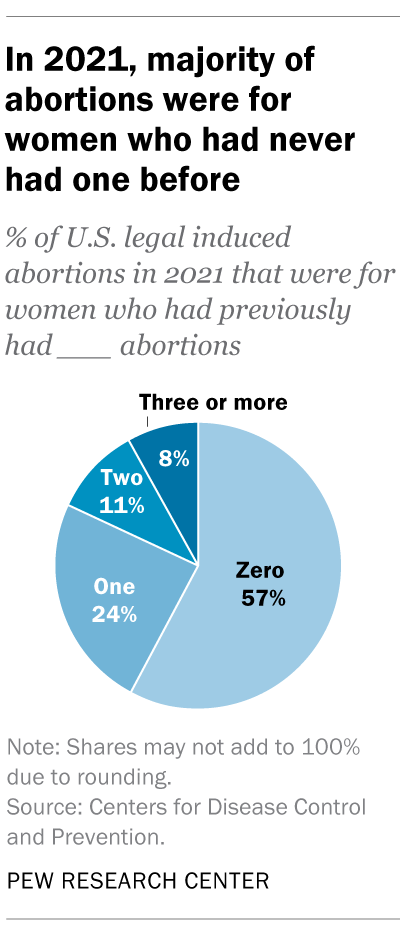

For 57% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2021, it was the first time they had ever had one, according to the CDC. For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of women who had an abortion that year, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or more. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

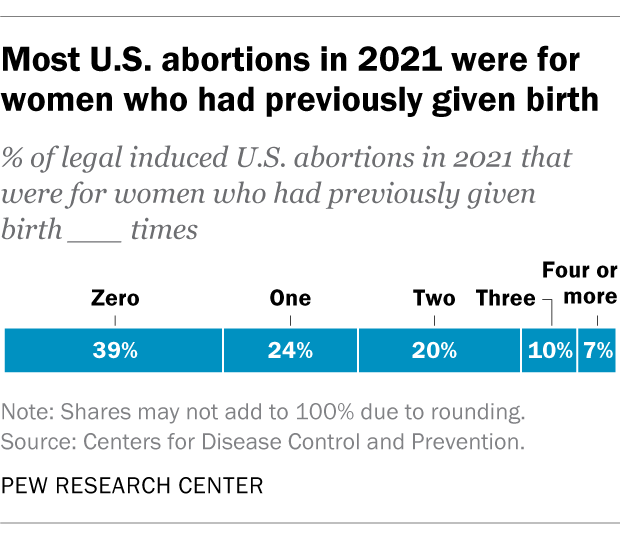

Nearly four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2021 (39%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion, according to the CDC . Almost a quarter (24%) of women who had abortions in 2021 had one previous live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 10% had three, and 7% had four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2021, 93% of abortions occurred during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of gestation, according to the CDC . An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and about 1% were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures include data from 40 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman , according to an article in StatPearls, an online health care resource. “Most complications are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and post-anesthesia complications,” according to the article.

The CDC calculates case-fatality rates for women from induced abortions – that is, how many women die from abortion-related complications, for every 100,000 legal abortions that occur in the U.S . The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined by the agency (2013 to 2020), when there were 0.45 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to 1977), when it was 2.09 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged from 0.52 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.78 (from 1978 to 1982).

The CDC calculates death rates by five-year and seven-year periods because of year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low number of women who die from legal induced abortions.

In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has information , six women in the U.S. died due to complications from induced abortions. Four women died in this way in 2019, two in 2018, and three in 2017. (These deaths all followed legal abortions.) Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women due to legal induced abortion has ranged from two to 12.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions (legal and illegal) tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 63. One driver of the decline was the drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 39 deaths from illegal abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that. (The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then, though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than afterward. For instance, there were 119 deaths from induced abortions in 1963 and 99 in 1965 , according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 27, 2022, and first updated June 24, 2022.

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many countries, especially in Europe

Nearly a year after roe’s demise, americans’ views of abortion access increasingly vary by where they live, by more than two-to-one, americans say medication abortion should be legal in their state, most latinos say democrats care about them and work hard for their vote, far fewer say so of gop, positive views of supreme court decline sharply following abortion ruling, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- JME Commentaries

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Further clarity on cooperation and morality David S Oderberg Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 192-200; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103476

- Freedom of conscience in Europe? An analysis of three cases of midwives with conscientious objection to abortion Valerie Fleming , Beate Ramsayer , Teja Škodič Zakšek Journal of Medical Ethics Feb 2018, 44 (2) 104-108; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103529

- Mere sincerity Edward Collins Vacek Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 201-202; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103885

- A reasonable objection? Commentary on ‘Further clarity on cooperation and morality’ Trevor G Stammers Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 203; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103884

- Conscientious objection in healthcare and the duty to refer Christopher Cowley Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 207-212; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103928

- Conscientious objection in healthcare: why tribunals might be the answer Jonathan A Hughes Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 213-217; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2015-102970

- Conscientious objection in healthcare, referral and the military analogy Steve Clarke Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 218-221; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103777

- Why medical professionals have no moral claim to conscientious objection accommodation in liberal democracies Udo Schuklenk , Ricardo Smalling Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 234-240; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103560

- Two conceptions of conscience and the problem of conscientious objection Xavier Symons Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 245-247; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103702

- Response to: ‘Why medical professionals have no moral claim to conscientious objection accommodation in liberal democracies’ by Schuklenk and Smalling Richard John Lyus Journal of Medical Ethics Apr 2017, 43 (4) 250-252; DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103643

- Other anaesthesia (34)

- Pain (anaesthesia) (18)

- Clinical diagnostic tests (63)

- Effectiveness of care

- Equity of care

- Teaching EBM

- General practice / family medicine (108)

- Clinical genetics (36)

- Cytogenetics

- Genetic screening / counselling (21)

- Molecular genetics (10)

- Elder abuse (1)

- End of life decisions (geriatric medicine) (424)

- Long term care (10)

- Psychogeriatrics (13)

- Bird flu (2)

- HIV/AIDS (151)

- Infectious diseases

- Adult intensive care (67)

- Mechanical ventilation (11)

- Paediatric intensive care (6)

- Neurogenetics

- Nursing (25)

- Abortion (18)

- Oncology (115)

- Child health (222)

- End of life decisions (palliative care) (424)

- Hospice (155)

- Pain (palliative care) (22)

- Prison medicine (45)

- Psychotic disorders (incl schizophrenia)

- Suicide (psychiatry) (160)

- Disability (71)

- Dialysis (1)

- Renal transplantation (17)

- Airway biology

- Bronchiolitis

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Sexual health (194)

- Sports and exercise medicine (30)

- Communication (14)

- Clinical trials (epidemiology) (110)

- Epidemiologic studies (104)

- Population trends

- Screening (epidemiology) (83)

- Survey techniques

- Therapeutic trials (1)

- Time-to-event methods

- Artificial and donated transplantation (201)

- Assisted dying (249)

- Bioethics (215)

- Clinical ethics (96)

- Codes of professional ethics (8)

- Competing interests (ethics) (85)

- Confidentiality (110)

- Drug issues (5)

- End of life decisions (ethics) (424)

- Ethics of abortion (206)

- Ethics of contraception

- Ethics of reproduction (375)

- Experiments in vivo (10)

- Informed consent (348)

- International / political dimensions of biology and medicine

- Research and publication ethics (592)

- Sexuality / gender

- The neurosciences and mental therapies

- Ethnic studies

- Health economics (50)

- Health informatics (8)

- Health policy (143)

- Health service research (118)

- Access, care

- Clinical governance

- Complexity science

- Healthcare dispariety

- Medical error

- Patient-centered, care

- Quality of life and health status

- Shared decision making

- Legal and forensic medicine (513)

- Getting and changing jobs (including job descriptions and contracts)

- Professional conduct and regulation (3)

- Postgraduate (10)

- Undergraduate (133)

- Aesthetics and medicine

- Architecture and medicine

- Art and medicine

- Arts in health

- Culture, health and illness (6)

- Education, medical (72)

- Experience of illness

- History of medicine (14)

- Human nature

- Illness narratives

- Images, use of in medicine

- Imagination and science

- Literature and medicine

- Medical anthropology

- Metaphor and illness

- Music and medicine

- Pain and pain management

- Performing arts and medicine

- Personal development

- Personhood and personality

- Philosophy and medicine

- Philosophy of medicine (22)

- Philosophy of science

- Politics and medicine

- Psychology and medicine (290)

- Quality of life

- Religion and spirituality

- Sex and sexuality (206)

- Theory of medical knowledge

- Value enquiry

- Medical humanities

- Doctors' morale and well being

- Medical error/ patient safety (22)

- Occupational and environmental medicine (18)

- Patients (85)

- Abuse (child, partner, elder) (16)

- Health education (106)

- Health of indigenous peoples

- Human rights (194)

- Infection control

- Burns (diagnoses)

- Head injury

- Spinal cord injury

- Workplace injury

- Pedestrian injury

- Poisoning/Injestion

- Recreation/Sports injury

- Suicide/Self harm (injury)

- Medical consequences of conflict

- Migration and health

- Obesity (public health) (18)

- Screening (public health) (83)

- Sexual health (public health)

- Smoking (37)

- Suicide (public health) (160)

- Vaccination programs (6)

- Violence against women (3)

- Sociology (6)

- Editor's choice (122)

- Guidelines, Recommendations and Consensus Statements

- JME Author meets critics (89)

- JME DSM-5 (5)

- JME Medical Ethics and Asylum

- Open access (184)

- Press releases (63)

- Special issue: 40th Anniversary of JME

- Special issue: Circumcision (18)

- Special issue: Criminalizing contagion (1)

- Special Issue: Ethics of Incentives in Healthcare (13)

- Special issue: Stem cell derived gametes (8)

- Special issue: The human body as property? Possession, control and commodification (12)

- Special issue: Withholding artificial nutrition & hydration (11)

I'm a Democrat who moved to Florida to be closer to my boyfriend. I was nervous about the politics and weather but have been most dismayed by the cost of living.

- David Maughan, 32, moved from Richmond, Virginia, to Oakland Park, Florida, last year.

- As a progressive, Maughan said he was nervous about Florida's culture war politics.

- But he's found Floridians to be accepting and welcoming, especially in the LGBTQ+ community.

This as-told-to essay is based on a conversation with David Maughan, a 32-year-old human resource analyst who moved from Richmond, Virginia, to Oakland Park, Florida, in August 2023 to be closer to his boyfriend. He shared his thoughts about living in the Sunshine State with Business Insider.

David : My Florida story started in 2020 when I met a guy named Brandon. We met online, like a lot of relationships nowadays, especially during early COVID. He lived in South Florida.

I was born and raised in Central Pennsylvania but had been living in Richmond, Virginia, since I was about 25.

Brandon and I dated casually for a couple of months and then became official. We were long-distance, going back and forth between Virginia and Florida for about three years. We knew we wanted to be together in the same place, so it became a question of which one of us would move. I work remotely, so it was easier for me to make the move.

I had a lot of concerns about moving to Florida

First of all, it was a big move away from my entire support system. I'm part of the LGBTQ+ community and that was something I felt was really strong in Richmond.

Thinking about starting over and making new friends in your 30s is daunting. I knew I would be with my boyfriend, and I had met a lot of his friends, so there would be a built-in friendship circle to some extent, but I still wanted to make my own friends.

But my top two concerns were the state politics and the weather. Many of my Richmond friends understood the first but didn't get my concerns about the weather. Everyone says the weather in Florida is great, but they don't realize that Florida is hot hot . In the summer, it's 90 to 95 degrees every day. It's exhausting. You don't want to go outside. Some people love that. But for me, it was a huge concern.

The other primary concern I had was politics. I consider myself a progressive and a Democrat. I call myself a pragmatic progressive. In Richmond, I had been very involved in volunteering for local Democratic campaigns. It's more than just a hobby for me; it's something I'm really passionate about.

Everyone in progressive circles looks at Florida in horror because of what the governor , state legislature, and state Supreme Court do. They've pushed really far-right policies, from gerrymandering congressional districts to passing a six-week abortion ban . These are not acceptable policies to me.

My boyfriend and I had a lot of conversations about those concerns before the move. He has a little saying: Florida is trash, but it's my trash. And I understand, he's lived here a long time.

I made the move in August 2023.

I moved to Oakland Park, which is a suburb of Fort Lauderdale. Oakland Park is small population-wise, but the surrounding Broward County has almost 2 million people. So, it's a much bigger metro area than I was used to.

Related stories

Overall, it's a comfortable place to live. But it's been a bit of a mixed bag for me so far. I love the community I've been able to find here. I found an LGBTQ+ adult sports league to participate in, and the nightlife nearby is good.

I think part of why it's been so easy to make friends is that a lot of people are also transplants . I haven't gotten any criticism from native Floridians about moving here. They've been welcoming.

But in terms of the downsides, Florida has a really car-centric design, which makes it uncomfortable to get around any other way. There are six-lane roads with traffic flying down them. There are signs that say bikes can share the road, but you'd have to be insane to do that. Even biking to the beach is difficult. I think I've only been to the beach three times in eight months.

I'm still getting used to Florida's topography. Richmond is a place with hills and rivers. But here, it's obviously flat as can be. There are a lot of single-family homes, low-rise apartments, and strip malls. A lot of the neighborhoods don't have good sidewalks, which was surprising to me.

I can't complain too much about the weather because I moved here in August when it started to cool off. The fall and winter have been nice. But we'll see how my first full summer goes.

Florida has dug into waging culture wars

Florida's elected leaders are pretty far-right. But I don't think the people of Florida are as far-right. That's an important difference. A lot of the races here are really close. And when you look at some of the ballot referendums that get put on the ballot in Florida , they are often for very progressive issues like reforming felon disenfranchisement.

I've tried to get involved with politics at the local level, where I feel I can make an impact. I got plugged into a group called Broward Young Democrats.

The area where I live is pretty accepting of the LGBTQ+ community for the most part. Wilton Manors, the town right next to Oakland Park is known as a "gay mecca." At the local level, there's a strong, supportive community.

But while I haven't experienced any direct harassment, and I don't fear for my safety, it is certainly concerning to think about what Florida might try to do down the road. If they're trying to ban transgender medical care today , what's to stop them from trying to pass discriminatory laws against all gay people tomorrow?

The cost of living is way higher in Florida

The biggest example is my rent. I had a one-bedroom apartment in Richmond that was 700 square feet, and I paid $1,400 a month, which at the time felt kind of expensive.

But here, I have a one-bedroom apartment that's about 800 square feet and it runs me $2,400 a month. It's a full thousand dollars more for an almost identical apartment.

Car insurance is also more expensive here. I pay double what I paid in Richmond. I had to reorient a lot of things in my budget when I moved here. I had to cancel some services, and I adjusted my retirement savings.

My apartment here is really nice, though. I decided I wanted to make sure I was happy with my living space, knowing the concerns I had about the state. Because if I was unhappy with the state politics and I had an apartment I hated, I would have been really miserable.

Florida is the right choice for me right now

Living here has obviously been great for my relationship with Brandon. We've been able to deepen our relationship and build a life together. That's the number one benefit, and it's been amazing.

But when I think longer-term, I don't see myself living here for the rest of my life. It's been a topic of conversation between us because I don't see myself buying property here, mainly because of the climate risk with hurricanes and flooding.

I'd like to buy property somewhere else, maybe in DC or Philly, somewhere more North. Then we could maybe rent an apartment or a condo down here and become snowbirds because I don't know if I'll able to be able to pull Brandon away from Florida entirely. He's got roots here.

And I always tell people: Love will make you do crazy things.

- Main content

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

A Terrorist Attack in Russia

The tragedy in a moscow suburb is a blow to vladimir v. putin, coming only days after his stage-managed election victory..

This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

From “The New York Times,” I’m Sabrina Tavernise, and this is “The Daily.”

A terrorist attack on a concert hall near Moscow Friday night killed more than 100 people and injured scores more. It was the deadliest attack in Russia in decades. Today, my colleague Anton Troianovski on the uncomfortable question it raises for Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin. Has his focus on the war in Ukraine left his country more vulnerable to other threats?

It’s Monday, March 25.

So Anton, tell us about this horrific attack in Russia. When did you first hear about it?

So it was Friday night around 8:30 Moscow time that we started seeing reports about a terrorist attack at a concert hall just outside Moscow. I frankly wasn’t sure right at the beginning how serious this was because we have seen quite a lot of attacks inside Russia over the last two years since the full scale invasion of Ukraine, and it was hard to make sense of right away. But then within a few hours, it was really looking like we were seeing the worst terrorist attack in or around the Russian capital in more than 20 years.

On Friday night, Crocus City Hall was the venue for a concert by an old time Russian rock group called Picnic. It was a sold-out show. Thousands of people were expected to be there. And before the start of the concert, it appears that four gunmen in camouflage walked into the venue and started shooting.

We started seeing videos on social media, just incredibly awful graphic footage of these men shooting concertgoers at point blank range. In one of the videos, we see one of them slitting the throat of one of the concertgoers. And then what appears to have happened is that they set the concert hall on fire. Russian investigators said they had some kind of flammable liquid that they lit on fire and basically tried to burn down this huge concert hall with wounded people in it.

Some of these people ended up trapped as the building burned, as eventually, the roof of this concert hall collapsed. And it seems as though much of the casualties actually came as a result of the fire as opposed to as a result of the shooting.

The actual attack, it looks didn’t take more than 15 to 30 minutes. At which point, the four men were able to escape. They got into a white Renault sedan and fled the scene.

It took the authorities clearly a while to arrive. The attackers were able to spread this horrific violence for, as I said, at least 15 minutes or so. So among other things, there’s a lot of questions being raised right now about why the official response took so long.

And you said the perpetrators got away. What happened next?

So it looks like they were caught at some point hours after the attack. On Saturday morning, the Kremlin said that 11 people had been arrested in connection to the attack, including all four perpetrators. They were taken into custody according to the Russian authorities in the Bryansk region of Russia, roughly a five-hour drive from the concert hall in southwestern Russia, also pretty close to the border with Ukraine.

Obviously, we have to take everything that the Russian authorities are saying with a grain of salt. And as we’ve been reporting on this throughout the weekend, we have very much tried to verify all the claims that the Russian authorities are making independently. And so our colleagues in the visual investigations unit of the times have been working very hard on that.

And what we can say based on the footage of the attack that was taken by many different individuals and posted to social media, it very much looks like the four men who were detained who Russia says were the attackers, in fact, are the same people who were seen doing the shooting in those videos of the attack judging by their clothes, judging by their hairstyle, judging by their build and other identifying characteristics that our colleagues have been looking at. So it does appear that by Saturday morning, the men who directly carried out this attack had been taken into custody.

Wow. So the Russian government actually apprehended the perpetrators, according to our reporting work that our colleagues have done. So who are these guys?

We don’t know much about them. The Russian government says that none of them are Russian citizens. After the arrest, throughout the weekend, videos, short clips of interrogations of these men have been popping up on the Telegram social networks, clearly leaked or provided by Russian law enforcement. You see these men bloodied, hurt.

And is this Russian interrogators abusing them?

Yes. That is very much what it looks like. And it’s also notable that the Russian authorities aren’t even hiding it. Two of the suspects in those videos are heard speaking Tajik. So that’s the language spoken in Tajikistan, a Central Asian country, but also in some of the surrounding countries, including Afghanistan.

At the end of the day, this is still very much a developing situation, and there’s a ton that we don’t know. But hours after the attack, the Islamic State, ISIS, took responsibility. And they then really tried to emphasize this by even releasing a video on Saturday showing the attack taking place as it was filmed apparently by one of the attackers. And US intelligence officials have told our colleagues in Washington that they indeed believe this to be true, that they believe that this ISIS offshoot did carry out this attack.

Wow. So the Americans actually think that ISIS, the extremist group that we know so well from Iraq and Syria, carried out this attack.

Yes. And all of this is really remarkable because just a few weeks ago, on March 7, the United States actually warned publicly that something just like this could happen. The US embassy in Moscow issued a security alert, urging US citizens to avoid large gatherings over the next 48 hours. They said that the embassy is monitoring reports that extremists have imminent plans to target large gatherings in Moscow to include concerts.

Crazy. That is a very specific warning.

Absolutely. And of course, the statement mentioned that specific 48-hour time frame. But nevertheless, it feels really significant.

And did the Russian authorities respond to that?

They did, and frankly, they responded mostly by ridiculing it. This is all obviously happening against the backdrop of the worst conflict between Moscow and the West since the depths of the Cold War. And so Vladimir Putin actually publicly dismissed this warning. He called it blackmail in a speech that he gave just three days before the attack last Tuesday.

So despite the specificity publicly at least, the Russian authorities did not take it seriously.

That is remarkable. And so three days later, this huge attack happens. Where is Putin in all of this? And who is he blaming? What’s his version of events?

So he’s coming off this Russian election season, as you know, where he declared this very stage managed victory and after that had been taking a victory lap of sorts. But Putin doesn’t appear on camera until around 19 hours after the attack. At that point, Russian state television airs a five-minute speech by Putin.

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]

He’s sitting at this nondescript desk surrounded by two Russian flags, but it’s not clear where he is located at that point. It doesn’t look like he’s at the Kremlin.

And Anton, what does he say?

So he describes the horror of this attack. He declares Sunday a national day of mourning. He says the most important thing is to make sure that the people who did this aren’t able to carry out more violence.

He also says that the four men who carried out the attack were captured as they were moving toward Ukraine. And he claims that based on preliminary information, as he put it, there were people on the Ukrainian side who were going to help these men cross the border safely. And remember, this is an extremely dangerous militarized border given that Russia and Ukraine have been in a state of full scale war for over two years now.

And as he ends the speech, He. Says that Russia will punish the perpetrators, whoever they may be, whoever may have sent them.

So what’s important about all that is first of all, that Putin did not mention the apparent Islamic extremist connection here that Western officials have been talking about, and that is in front of all of us given that Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the attack. But he does set the stage for blaming Ukraine for this horrific tragedy, even though it seems that Putin and the Russian government may be alone in thinking that.

We’ll be right back.

So Anton, the Islamic State has claimed responsibility for this attack, but Putin ignores that and kind of obliquely points the finger at Ukraine. What do we actually know about who did this?

Well, let’s start with the group that claimed responsibility for this attack. That’s ISIS, the Islamic State. And in particular, US officials are talking about a branch of ISIS called ISIS-K or Islamic State Khorasan, which is an Islamic State affiliate that’s primarily active in Afghanistan and that in recent years has gained this reputation for extreme brutality.

They might be best known in the US for being the group behind the Kabul Airport bombing back in 2021 right after the Taliban took over when thousands of Afghans were trying to escape. That was a bombing that killed 13 American troops and 171 civilians, and it really raised ISIS case profile.

So this terrorist group is mainly based in Afghanistan. What do they want with Russia?

So what’s notable is our colleague Eric Schmitt in Washington talked to an expert over the weekend who said ISIS-K has really developed an obsession with Russia and Putin over the last two years. They say Russia has Muslim blood on its hands.

So it looks like the primary driver in this enmity against Russia is Russia’s alliance with Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president, who is also a sworn enemy of ISIS. And Russia intervened, of course, on Assad’s behalf in the Syrian civil war starting back in 2015. But it’s not just Syria. So the experts we’ve talked to say that in the ISIS-K propaganda, you also hear about Russia’s wars in the Southern region of Chechnya in the 1990s and the early 2000s.

And also even about the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan throughout the 1980s. There’s this really long arc of Russia’s and the Soviet Union’s wars in Muslim regions that appears to be driving this violent hatred of Russia on the part of ISIS-K.

OK. So ISIS-K is pointing not only to Russia’s actions in Syria but actually further back into Russian history, even Soviet history, to its war in Chechnya and then to the Soviet’s war in Afghanistan. Yet Putin in his speech ignores the group entirely and instead points in the direction of Ukraine. Is there a chance that this attack could have been carried out by Ukraine?

Well, look. It is true that Ukraine has carried out attacks inside Russia that put Russian civilians at risk. There have been several bombings that American officials have ascribed to parts of the Ukrainian government. Perhaps most famously, there was the bombing that killed Darya Dugina, the daughter of a leading Russian ultranationalist back in the summer of 2022.

That was a bombing that happened just outside Moscow. And of course, there have been various drone strikes by Ukraine against things like Russian energy infrastructure even just in the last few weeks. But we really don’t see any evidence right now of any connection of the Ukrainian state to this attack. US officials tell us they don’t see anything, and we haven’t in our own reporting come across such a connection either.

And there is, of course, the context of the US has said very clearly that they don’t want to see Ukraine carrying out big attacks inside Russia. American officials have said that doing so is counterproductive, could lead to the risk of greater escalation by Putin in his war. And we’re in an extremely sensitive time right now when it comes to US support for Ukraine.

The US, of course, has given all these weapons, tens of billions of dollars in aid to Ukraine. But right now, $60 billion in aid are stuck in US Congress. And you would think that Ukraine wouldn’t want to do anything right now —

That could risk that.

That could risk that. Exactly. I mean, also, let’s just say, I mean, this was an incredibly horrific attack, and we haven’t seen anything from Ukraine in the way they’ve carried themselves in defending against Russia in this war that would make us think they would be capable of doing something like this.

Anton, just to step back for a moment. I mean, it’s interesting because this attack, it really doesn’t remotely fit into Putin’s obsession about where the threat is coming from in the world to Russia, right? His obsession is Ukraine. And this kind of short circuits that.

Absolutely. I mean, Russia has had a real Islamic extremism problem for decades going back to the 1990s to those brutal wars against Chechen separatists that were a big part of Putin coming to power and developing his strongman image.

So it’s really remarkable how we’ve arrived at this turning point here for Putin where he used to be someone who really portrayed himself as the man keeping Russians safe from terrorism. Now the threat of terrorism coming from Islamic extremists doesn’t really fit into that narrative that Putin has because now Putin’s narrative is all about the threat from Ukraine and the West and that the most important thing to do now for Russian national security is to win the war against Ukraine.

And does the security failure here have anything to do with Russia actually being obsessed with Ukraine? Like it’s kind of taken its eye off the ball?

Well, look. The Russian domestic intelligence agency, the FSB, they’re the ones who are supposed to keep the country safe from terrorism. But that has also been the agency that has been charged with asserting control over the territories in Ukraine that Putin has occupied, and the FSB has been spending all this time hunting down dissidents of Putin.

Just a few hours before the attack on Friday, Russia officially classified the so-called LGBT movement, as they put it, on their list of terrorists and extremists. So terrorists in the current Putin narrative are anyone who disagrees with him, who criticizes the war, and who doesn’t fit into the Kremlin’s conception of so-called traditional values, which has become such a big Putin talking point.

So the FSB has been pretty busy but not in terms of Islamic terrorism. In terms of its own people.

Exactly. We don’t know for sure obviously how the FSB is apportioning its resources, but there’s a lot of reason to believe that as the leadership of that organization has been looking at Putin’s priorities in Ukraine and in terms of cracking down on dissent domestically, they could well have lost sight of the risks of actual terrorism inside Russia.

Which is pretty remarkable, right, Anton? Because you and I know and we’ve spoken a lot about on the show, a big part of the reason that Putin actually appeals, his argument to Russians is that he’s the security guy. Think what you will about him. He’s the guy who’s fundamentally going to keep you safe. And here we have this attack.

That’s right. And so he needs to continue making the case that he knows how to keep Russia safe. And that’s why my colleagues and I have been watching a lot of Russian state TV this weekend. And this ISIS claim of responsibility barely comes up. And when it does come up, it’s often being referred to as fake news. Instead, Russian propaganda is already assuming that it was Ukraine and the West that did this. We’ll see if the Russian public buys that.

But if you look at the way the last two years have gone in Russia, I think you have to draw the conclusion that Russian propaganda is extremely powerful. And I think if this message continues, it’s quite likely that very many Russians will believe that Ukraine and the West had something to do with this attack.

And so the worry now, as we look ahead, is that Putin could end up using this to try to escalate his war even further, which shows us why this is such a tenuous and perilous moment because at the same time, this attack reminds us that Russia faces other security risks. And as Putin deepens that conflict with the West, he may be doing so at the cost of introducing even more instability inside the country.

Anton, thank you.

Thank you, Sabrina.

Late Sunday night, the four men suspected of carrying out the concert hall attack were arraigned in a court in Moscow and charged with committing an act of terrorism. All four are from Tajikistan but worked as migrant laborers in Russia. They range in age from 19 to 32 and face a maximum sentence of life in prison. Also on Sunday, Russian authorities said that 137 bodies had been recovered from the charred remains of the concert hall, including those of three children.

Here’s what else you need to know today.

In January, I underwent major abdominal surgery in London, and at the time, it was thought that my condition was non-cancerous. The surgery was successful. However, tests after the operation found cancer had been present.

In a video message on Friday, Catherine, Princess of Wales, disclosed that she’d been diagnosed with cancer and has begun chemotherapy, ending weeks of fevered speculation about her absence from British public life.

This, of course, came as a huge shock, and William and I have been doing everything we can to process and manage this privately.

In her message, Middleton did not say what kind of cancer. She had or how far it had progressed but emphasized that the diagnosis has required meaningful time to process.

It has taken me time to recover from major surgery in order to start my treatment. But most importantly, it has taken us time to explain everything to George, Charlotte, and Louis in a way that’s appropriate for them and to reassure them that I’m going to be OK.

Today’s episode was produced by Will Reid and Rachelle Bonja. It was edited by Patricia Willens, contains original music by Dan Powell and Marion Lozano, and translations by Milana Mirzayeva and was engineered by Alyssa Moxley. Special thanks to Eric Schmitt and Valerie Hopkins. Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m Sabrina Tavernise. See you tomorrow.

- April 19, 2024 • 30:42 The Supreme Court Takes Up Homelessness

- April 18, 2024 • 30:07 The Opening Days of Trump’s First Criminal Trial

- April 17, 2024 • 24:52 Are ‘Forever Chemicals’ a Forever Problem?

- April 16, 2024 • 29:29 A.I.’s Original Sin

- April 15, 2024 • 24:07 Iran’s Unprecedented Attack on Israel

- April 14, 2024 • 46:17 The Sunday Read: ‘What I Saw Working at The National Enquirer During Donald Trump’s Rise’

- April 12, 2024 • 34:23 How One Family Lost $900,000 in a Timeshare Scam

- April 11, 2024 • 28:39 The Staggering Success of Trump’s Trial Delay Tactics

- April 10, 2024 • 22:49 Trump’s Abortion Dilemma

- April 9, 2024 • 30:48 How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

- April 8, 2024 • 30:28 The Eclipse Chaser

- April 7, 2024 The Sunday Read: ‘What Deathbed Visions Teach Us About Living’

Hosted by Sabrina Tavernise

Featuring Anton Troianovski

Produced by Will Reid and Rachelle Bonja

Edited by Patricia Willens

Original music by Dan Powell and Marion Lozano

Engineered by Alyssa Moxley

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

Warning: this episode contains descriptions of violence.

More than a hundred people died and scores more were wounded on Friday night in a terrorist attack on a concert hall near Moscow — the deadliest such attack in Russia in decades.

Anton Troianovski, the Moscow bureau chief for The Times, discusses the uncomfortable question the assault raises for Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin: Has his focus on the war in Ukraine left his country more vulnerable to other threats?

On today’s episode

Anton Troianovski , the Moscow bureau chief for The New York Times.

Background reading

In Russia, fingers point anywhere but at ISIS for the concert hall attack.

The attack shatters Mr. Putin’s security promise to Russians.

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

Translations by Milana Mazaeva .

Special thanks to Eric Schmitt and Valerie Hopkins .

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Anton Troianovski is the Moscow bureau chief for The Times. He writes about Russia, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. More about Anton Troianovski

Advertisement

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Kidney Dis (Basel)

- v.4(4); 2018 Nov

History, Current Advances, Problems, and Pitfalls of Nephrology in Russia

The anatomy and physiology of kidneys as well as kidney diseases have been studied in Russia since the 18th century. However, there was a surge in interest in the 1920s, with numerous researchers and clinicians making substantial advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology, pathology, and diagnostics of kidney diseases. The field of nephrology as clinical practice can be traced back to 1957–1958, when the first beds for patients with kidney diseases became available and the first hemodialysis procedure was performed. Nephrology and hemodialysis units were opened soon after, offering kidney biopsy, corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapies, and dialysis for acute renal failure and end stage of renal disease. In 1965 kidney transplantation commenced. Between 1970 and 1990, the number of centers providing care for patients with kidney diseases increased; however, they were insufficient to meet the demands of native kidney disorders and renal replacement therapy. To address this, several educational institutions established postgraduate programs in nephrology and dialysis, and professional societies and journals were funded. While economic changes at the end of the 1990s resulted in a rapid increase of dialysis service, kidney transplantation and pathology-based diagnostics of kidney diseases remained underdeveloped. During the last 2 decades cooperation among international professional societies, continuing medical education courses, and the translation and implementation of international guidelines have resulted in substantial improvements in the quality of care provided to patients with kidney diseases.

We describe the history and development of clinical nephrology, dialysis, kidney transplantation, education in nephrology and dialysis, professional societies and journals, and registry of patients on renal replacement therapy in Russia during almost 60 years. We also present the most recent registry data analysis, address current problems and difficulties, and stress the role of incorporation into the international nephrology community.

Key Message