Map Options

PhD Percentage by Country / Number of Doctorate Degrees per Country 2024

1. slovenia.

Slovenia is the highest-ranking country in the number of Ph.D. degrees earned by adults between the ages of 25 and 64. 5% of the entire population in Slovenia has a Ph.D. The distribution between Ph.D. adults in Slovenia finds more female doctorates than males. About 4.5% of adult females have a Ph.D., compared to about 3% of adult males in Slovenia.

2. Switzerland

Switzerland has the second-highest rate of Ph.Ds. globally, with nearly 3% of the adult population holding this advanced degree. In Switzerland, men are more likely to hold a Ph.D., representing 4% of the total doctorate population, compared to about 2.5% for female doctorates.

3. Luxembourg

In Luxembourg, 2% of the total population holds a Ph.D. There are several countries tied for 2% of the population with a Ph.D., and almost all of the highly educated countries are in Europe . In Luxembourg, 2.5% of Ph.D. holders are male, compared to 2% female.

4. United States

The United States is tied with European countries when it comes to being a highly educated population. About 2% of the U.S. population holds a Ph.D. Men are more likely than women to have a Ph.D. in the United States, with 2.5% of the Ph.D. candidates male and about 2% female.

Like other countries on our list, Sweden is tied with 2% of the total population holding a doctorate degree. In this country, males and females are just about equal when it comes to this advanced degree. Around 2.5% of males have a Ph.D., while 2.2% of females hold a Ph.D. in Sweden.

6. The United Kingdom

Rounding out our list of highly educated countries with the most Ph.Ds., the United Kingdom has about 2% of the population holding a Ph.D. In the United Kingdom, males and females are pretty close to equal in higher education. Males account for more Ph.D. degrees, with about 2.5%, while females are close behind with nearly 2.3% Ph.Ds.

Another European country on our list of the most Ph.Ds., Germany, has about 2% of its population with a Ph.D. This country sees a more significant discrepancy between males and females when it comes to higher education. About 1.75% of males account for Ph.Ds. awarded, while only about 1% of females have their Ph.D. in Germany.

8. Australia

Breaking up the stranglehold at the top of our list between Europe and the United States, Australia makes the list with the 8th most Ph.D. citizens per capita. In Australia, 2% of the population holds a doctorate degree. Males and females are almost identical regarding Ph.Ds., with males just slightly earning a Ph.D. more frequently. Males account for 1.1% of Ph.Ds. in the country, while females account for 1.0% of the Ph.Ds. awarded in Australia.

Download Table Data

Enter your email below, and you'll receive this table's data in your inbox momentarily.

What country has the highest percentage of PhDs?

Frequently asked questions.

- What are the characteristics and outcomes of doctoral graduates? - OECD

- These countries have the most doctoral graduates - World Economic Forum

- List of countries by number of doctorates awarded - Wiki

Advertisement

- Publications

This site uses cookies to enhance your user experience. By continuing to use this site you are agreeing to our COOKIE POLICY .

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Create an account below to get 6 c&en articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free., it seems this is your first time logging in online. please enter the following information to continue., as an acs member you automatically get access to this site. all we need is few more details to create your reading experience., not you sign in with a different account..

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Already have an ACS ID? Log in here

The key to knowledge is in your (nitrile-gloved) hands

Access more articles now. choose the acs option that’s right for you..

Already an ACS Member? Log in here

$0 Community Associate

ACS’s Basic Package keeps you connected with C&EN and ACS.

- Access to 6 digital C&EN articles per month on cen.acs.org

- Weekly delivery of the C&EN Essential newsletter

$80 Regular Members & Society Affiliates

ACS’s Standard Package lets you stay up to date with C&EN, stay active in ACS, and save.

- Access to 10 digital C&EN articles per month on cen.acs.org

- Weekly delivery of the digital C&EN Magazine

- Access to our Chemistry News by C&EN mobile app

$160 Regular Members & Society Affiliates $55 Graduate Students $25 Undergraduate Students

ACS’s Premium Package gives you full access to C&EN and everything the ACS Community has to offer.

- Unlimited access to C&EN’s daily news coverage on cen.acs.org

- Weekly delivery of the C&EN Magazine in print or digital format

- Significant discounts on registration for most ACS-sponsored meetings

Your account has been created successfully, and a confirmation email is on the way.

Your username is now your ACS ID.

Science in the US is built on immigrants. Will they keep coming?

International scientists have long been a key part of the us research workforce, but concerns are rising that they’ll start to turn elsewhere, by andrea widener, march 4, 2019 | a version of this story appeared in volume 97, issue 9.

Credit: Davide Bonazzi

- 9 ways to motivate others

- Out and proud

- What US chemists made in 2022, according to the ACS salary survey

- Gianluigi Veglia sexually harassed his students and lab staff but wasn’t fired

- Making space in STEM for people with disabilities

Immigration is a huge contributor to US science and innovation, with thousands of students and scholars coming to the country each year. But the increase in anti-immigrant rhetoric in the past few years has scientists worried that their international colleagues might choose to go to other countries instead. So far, though, few changes to immigration policy are preventing scientists from studying and working in the US. Read on to hear the stories of immigrant chemists and find out more about the challenges they face.

Almost as soon as he started college, Morteza Khaledi knew he wanted to be a professor. And he quickly decided that a doctoral degree from a US university was the best path to get there.

Armed with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Pahlavi University (now Shiraz University), in Iran, Khaledi applied to several US universities for graduate school. He was accepted to the University of Florida in 1978, and he has lived in the US ever since. Over those four decades, he rose from student to chemistry professor to, now, dean of science at the University of Texas at Arlington.

“When I was a student, the US was really dominant in science and technology areas, and I think we still have the upper hand,” he says. “But other countries have caught up.”

He worries that increased competition, amplified by the current wave of anti-immigrant rhetoric in the US, will push top international students to choose schools in Canada, Europe, Singapore, and elsewhere. “There are great talents from all over the world,” Khaledi says. “If you close the door or limit them, then it will have an impact on the research that we do.”

Much of the rest of the scientific community is worried too. With constant talk of a border wall, trade fights with China, and sanctions against Russia, immigration is at the top of many scientists’ minds worldwide.

The Donald J. Trump administration has made some changes to immigration policy. The most notable is the ban against immigrants from six countries , including Iran. Other proposals include stricter examination of Chinese students and scientific visitors, changes to the H-1B visa system for temporary workers, and work restrictions on the spouses of US visa holders.

Despite those changes, though, most scientists are still able to come to the US as they could before Trump became president, albeit with the potential for longer waits. Big changes to US immigration policy—including talk of moving to an immigration system that prioritizes highly skilled workers—will require an act of Congress, something unlikely to happen given the wide political divides.

Sign up for C&EN's must-read weekly newsletter

Contact us to opt out anytime

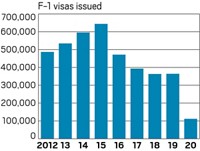

But words have power, and the negative political talk about immigration appears to be having an effect: the number of international applicants to study at US colleges and universities has declined two years in a row. And more and more scientists are starting to question whether the US is the right place for them.

“Every meeting we go to abroad, someone will express concern about US visa issues and visa policy. Every single meeting,” says Kathie Bailey, director of the Board on International Scientific Organizations at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Perceptions are very difficult to battle.”

Scientist immigration by the numbers

Percentage of doctoral-degree chemists who were naturalized or non-US citizens in 2017 a

Percentage of doctoral-degree chemical engineers who were naturalized or non-US citizens in 2017 a

Percentage of foreign-born recipients of US science and engineering doctoral degrees in 2015 who planned to stay in the US b

Percentage of US patents with at least one non-US citizen inventor in 2007 c

Year the number of immigrants from Asia to the US overtook immigration from Latin America d

Percentage of US adults who believe the country should encourage immigration of high-skilled workers e

Impact of science immigration

Chemist Hye-Won Song felt limited by the research choices in her native South Korea. So after she finished a master’s degree there, she applied to graduate schools in the US. “There are more opportunities and more research topics going on,” she says.

That same wide range of research opportunities led her to want to stay in the US after getting her doctoral degree at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California San Diego. But staying wasn’t easy.

Song spent five years in her postdoc, in part waiting for her research papers and citations to stack up while she looked for a job. She was also saving money to hire a lawyer to take her through the immigration process.

In the meantime, she had to deal with the constant uncertainty of being in the US on a limited visa. Once Song had to file a duplicate renewal application—and miss a paycheck—when her original paperwork got lost in the system. And every time she got a new visa, she also had to visit the Department of Motor Vehicles to renew her driver’s license. “It really makes our lives miserable, but most people don’t know about it,” Song says.

Related: Scientists speak out against U.S. President Trump’s immigration ban

Eventually, Song succeeded in becoming a permanent US resident, with the green card to prove it. That status made it a lot easier for her to find a job in industry. “A lot of companies, they do not offer to support a visa,” she says. “They want you to bring your green card with you.”

Song’s story is familiar to many scientists who immigrate to the US and stay. They face constant uncertainty with each visa renewal, along with fear that a visit home might mean they can’t return to work. But they keep coming because of the science. “Research-wise it was worth getting here,” Song says.

The domestic US research community, too, thinks it is worth including foreign-born scientists and for the most part has welcomed immigrants into labs with open arms. “Immigration has been a tremendous boost to science and engineering,” says Harvard Business School’s William Kerr, who has written a book on immigration, The Gift of Global Talent .

Almost any way you look at it—percentages of patents, Nobel Prize winners, citations, entrepreneurs—immigrants match or exceed native US workers, he says. Currently, immigrants make up around 25% of all US science and technology workers and around 50% of the doctoral-level science workforce nationwide.

Kerr’s work and that of others has found that for the most part, international scientists don’t compete with domestic researchers. “You don’t have a fixed pie of jobs,” he explains. Immigrants “make the pie bigger, adding on to what natives would have accomplished.”

Immigrants to the US are more likely than native scientists to be self-employed, including as entrepreneurs, says Jennifer Hunt, an economist at Rutgers University. Immigrants are also more likely to hold patents. “More people means more ideas and probably more innovation,” Hunt explains.

Mikhail Shapiro, a California Institute of Technology chemical engineering professor, came to the US from Russia when he was 11. While he doesn’t think his immigrant background changed his career path, he does think it gave him a certain mentality. “There is a desire to seize opportunities and work hard and really make the most of the opportunities you have,” he says.

That has also been the experience of Jeremy Levin, chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics. Levin lived in South Africa and then Rhodesia before getting his degrees and working in the UK. He then moved to the US specifically because of its vibrant science and innovation culture. He commonly sees other immigrants at the head of science and technology companies, and research labs filled with immigrants.

Immigration “has been a critical component not just of driving innovation but sustaining the US economy in a way that is just remarkable,” Levin says.

Levin worries that any tightening of US immigration policy—perceived or real—will have long-term consequences for the US economy, especially in the biological sciences. In 2017, he wrote a letter in Nature Biotechnology signed by over 150 biotech leaders and founders against Trump’s ban on select immigrants.

The political rhetoric around immigrant criminals and the need for a wall on the US-Mexico border is “raising the specter of intolerance, raising the specter of racism,” he says. “All of this is designed to raise fears around immigration.”

Related: Undocumented students remain in the shadows of the chemical sciences

Terrorism is a real threat that must be addressed, Levin believes. He speaks from personal experience here, too: he was once inspecting a pharmaceutical plant in Israel as it was bombed by Hamas, a militant group. But the fight against terrorism “needs to be distinguished from the need to attract incredibly bright people who want to contribute to science,” he says.

“Many of the best scientists in Europe and Asia will choose not to come to us,” Levin says. “They perceive that the barriers to entry in the US have been raised unreasonably high.”

Typical US visa types for chemists

A temporary visa issued to most international students who are accepted to a US college or university as an undergraduate or graduate. Students must prove they can pay tuition or that it is covered in other ways.

Short for optional practical training, an extension of the F-1 visa, for scientists, that can last up to three years. Frequently used to begin postdoctoral training or start a job while applying for another visa.

A temporary visa issued to research scholars and other visitors. Commonly used by postdoctoral scholars.

A temporary visa for which employers apply to bring in specific high-skilled workers unavailable domestically. The number of visas is capped for companies but unlimited for nonprofit organizations, including universities.

Permanent resident status, signified by obtaining a so-called green card. Requires applicants to submit paperwork proving their value, such as by listing papers published or documenting community service, such as peer review. Frequently requires a job offer from a US organization.

Scaring off students

Regardless of whether the US is actually harder to enter, there has been a measurable decline in international students applying to come to the US. The number of applications from international graduate students to study in the US has dropped a total of 4% in the last two years across all fields. That average masks a more significant 9% decline in physical and earth sciences from 2017 to 2018, according to data from the Council of Graduate Schools .

Academic and industrial scientists worry whether that trend will continue and whether it will spread beyond students. The chaotic rollout of Trump’s travel ban in January 2017 “really spooked international students and scholars,” says Rachel Banks, director of public policy at NAFSA: Association of International Educators. “People increasingly started thinking twice.”

When people are deciding where to go to college or graduate school, they are thinking ahead to whether it’s a place they want to be long term. People who start their education in another country are less likely to migrate to the US later. “You have to think about the international student experience like a pipeline,” Banks says. As international student enrollment has dropped in the US, it has gone up in Australia, Canada, China, and elsewhere. “No doubt they have taken advantage of what is happening in the US as a marketing tool,” Banks says.

Shapiro from Caltech has seen the impact of stricter policies among his students. Currently he has a doctoral student who has been stuck in China for months because he can’t get his visa renewed. “It’s not fair to them,” he says. He hopes the current atmosphere is temporary. “I don’t care where they come from. I want them to stay here.”

Currently, China sends more students to study in the US than any other country. At the same time, the Trump administration has proposed changes, including more scrutiny on scientists working on robotics, aviation, and high-tech manufacturing, that specifically target Chinese immigrants because of fears they are appropriating those technologies. Chemistry has escaped the spotlight so far.

Any moves that significantly shut down Chinese student immigration could be devastating, Harvard’s Kerr says. Currently, about 9% of US innovation is attributed to scientists of Chinese ethnicity.

“It would send shock waves through the system,” Kerr says. “Nothing we have done up until now would compare to revoking student visas.”

That impact would be felt especially hard in chemistry. Economist Patrick Gaule from the University of Bath has studied the quality of chemistry graduate students from China.

His 2013 study of 16,000 US chemistry PhDs showed that Chinese students in chemistry publish more than average. Their quality—as measured by those publications—equals that of domestic students who receive National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships ( Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, DOI: 10.1162/rest_a_00283 ). “It’s more difficult to get into a PhD program if you are applying from China than applying from inside the US,” he says. “That’s what I think is driving the results.”

Gaule has also surveyed US chemistry graduate students on their future-employment preferences. He continues to find that students want to stay in the US. People worry that “everybody is going to Canada,” he says. “So far we don’t see it.”

That’s been the case for postdocs as well. Of approximately 80,000 postdocs in the US, two-thirds are international scholars, says Tracy Costello, chair of the board of directors at the National Postdoctoral Association and director of postdoctoral affairs at the Moffitt Cancer Center.

Related: Working group looks at immigration’s impact on chemistry

“We want to foster an environment where if someone comes and trains here and wants to stay, that’s possible,” Costello says. “If they want to take that knowledge and go back to their countries, that’s possible too. Science is a global enterprise.”

While the postdoc association is concerned about the immigration-related rhetoric, “We hear the sky is falling a lot and somehow there is still a sky,” she says. Fundamentally, the system hasn’t changed, and while she expects minor changes from the Trump administration, “the status quo for right now is not a bad space.”

In 2009, after finishing graduate school in China, Zuolei Liao came to the US as a postdoc, attracted both by the research and by the culture. He works in uranium chemistry and so expected to have to wait a long time for his visa, but it came through in a few weeks, and he was soon on his way to the University of Notre Dame.

Liao spent several years there and then at Oregon State University, first on a visitor visa and then on an H-1B. After several years, he decided he wanted to stay in the US. But he didn’t take a traditional path: Liao joined the military, which made him eligible for citizenship at the end of basic training.

“I probably would have still joined if I had the chance,” even without the opportunity for citizenship, he says. “I just wanted to get more experience, to make myself a better person.”

After 4½ years in the army, Liao now works at a pharmaceutical company in Wisconsin. He knows only a few other scientists who also turned to military service to stay in the country—but however it’s accomplished, he thinks the US should encourage more doctoral students and postdocs to stay. “We trained them here, so we shouldn’t send them to other countries,” he says. “If you follow the law, you should be rewarded.”

Enduring employment woes

“What Trump has done more than anything is just make people scared,” says Brian Getson, an attorney at immigration specialty law firm Getson & Schatz.

While the Trump administration hasn’t eased immigration to the US, at the same time, “there is no proposal to make it more difficult for scientists,” adds Marco Pignone, who is also an attorney at Getson & Schatz and often represents chemists.

Part of the firm’s job is to reassure people that they can still get an employment visa or green card, Getson says. Visa delays have increased, however, especially for scientists from India and China, Getson says. There are more people who want green cards from those countries than the number available.

One of the main ways scientists come to the US for work or stay after graduation is through employer-sponsored visas. Currently, only 25% of US visas are driven by employment (the remaining 75% are family based).

The H-1B, a temporary visa for high-skilled workers, is sometimes the first step. Nonprofits, including universities, don’t have a limit on H-1B slots. But companies do have a limit. There are 85,000 slots available, and companies nationwide routinely submit double that many applications within days of the application system opening each year. Visa recipients are then chosen by lottery.

A lottery is “probably not the best way,” Kerr points out. Even large companies that apply for thousands of H-1Bs don’t get to choose which workers get the visa slots, which means they often aren’t getting their top choice among their applicants.

Right now, around 70% of H-1B visas go to jobs in the computer and technology industry, while just 2.6% fill positions in mathematics and physical sciences.

The Trump administration has proposed some changes to H-1Bs. One would give people with master’s degrees and higher a better chance of getting a slot.

Another would switch the H-1B application process from paper to electronic. “I imagine it would require a lot of money, but it would be money well spent,” Rutgers’s Hunt says. An electronic system would make it easier to tweak the H-1B lottery so it is not as random. And it could allow for better representation across fields rather than letting computer-science occupations crowd out other sectors.

Kerr likes the idea of giving priority to the jobs with the highest salaries, which generally indicate that a job is harder to fill. Some economists have also proposed giving greater preference to applicants with the highest degrees.

“High-skilled immigration is fundamentally an investment,” Kerr says.

But as clunky as the US immigration system is, immigrants in the US tend to have better employment outcomes than those in other countries, and that may be because in the US, more are being chosen by companies than by the government, Hunt says. “I’m actually not sure that the current system is terrible,” Hunt says.

An immigrant from Germany, Jens Breffke went through “the whole alphabet of visas” on his road to becoming a citizen.

Looking for an international adventure, Breffke came to the US on a student F-1 visa to attend graduate school, then began a postdoc at the National Institute of Standards and Technology using a three-year F-1 extension for scientists called OPT for optional practical training.

But when it came time to look for a job in industry, Breffke felt stuck. He couldn’t easily transition to an industry-sponsored H-1B because visa rules meant a gap of almost a year and a half between the time his postdoc ended and when he would have been eligible for an H-1B—and then he still would’ve been subject to the lottery.

“You have to find someone who wants to hire you so badly a year and a half in advance,” Breffke says. “Even if you are the most qualified person, you will always be second in line to someone who could just be hired this week.”

Breffke thinks he would have eventually qualified for a visa for exceptional scientists, but it takes years for the publications and citations that count toward that “exceptional” grade to accumulate. In the end, his girlfriend proposed, and he got a visa through his marriage. He now works for an electronics company in Boston and also serves as chair of the International Activities Committee for the American Chemical Society, which publishes C&EN.

“I did my PhD in this country and a postdoc working for Uncle Sam,” he says. “I do believe I deserved a chance to work in this country, but the system makes that pretty much impossible.”

Changing the climate

“Immigration writ large is top of mind for a lot of people,” says Susan Butts, a consultant and former senior director at Dow Chemical who is chairing an ACS committee developing a policy statement on immigration.

This isn’t the first time the society has tried to develop a policy on the issue, Butts says. The previous effort “was unsuccessful because they could not come to a consensus,” she says. She’s hoping for a different outcome this time. The group has looked at data on immigration, as well as examined surveys of ACS members on the issue.

While there are individual ACS members who are worried about losing their jobs to immigrants, Butts says, “there are a lot of data that say immigrants are an important part of the chemistry enterprise, especially at the advanced-degree level.”

If things go smoothly, a policy statement could be out by the end of 2019, Butts says. Having the statement will enable ACS to better engage in immigration policy discussions in Washington, DC, as part of ACS’s mission to support the chemical enterprise.

Major changes to US immigration policy aren’t likely soon, given the massive divide between Democrats and Republicans in Congress. Many advocates for immigration reform in the past have left Congress, and it’s unclear now who will push for reform.

Kerr says that the US has never had an easy immigration system, and people would adjust if any changes are made fairly for all immigrants.

But denying entry to specific groups can cause serious repercussions. The outcome of recent discourse “really has been to fundamentally shake the confidence that people all around the world have in the United States and whether the US is where they want to make their long-term investment,” Kerr says. “We are getting a black eye.”

That concerning atmosphere isn’t just for scientists abroad. Chemist Madan Bhasin immigrated to the US from India in 1959 and eventually got his PhD at Notre Dame. He got a job at Union Carbide in West Virginia in 1963 and has lived in the area ever since.

Just a handful of Indian families were in the area when Bhasin and his wife first arrived. Although he initially heard some talk about foreigners taking away jobs from US workers, anti-immigrant sentiment in the wider community hadn’t been prevalent until recently.

“I’m fortunate to have come here and to be very happy here,” Bhasin says. But he has felt a difference in the atmosphere in the last few years. To be cautious, his local Indian community center hired police to patrol a function after hearing about attacks on immigrants nationwide. His grandson warned him to be careful in the community.

Bhasin hopes that anti-immigrant rhetoric and visa challenges won’t keep scientists away, but he has heard horror stories from some of his scientist friends who visited India on vacation and then had trouble returning. Trying to immigrate “has been a nightmare for some of them,” he says. “Many people are not even considering coming.”

“I wish we could all practice tolerance toward each other,” Bhasin says.

Anti-immigrant sentiment is what prompted Khaledi from UT Arlington to finally get his green card. “The motivating factor was that after 9/11, things got serious,” he says, referring to the 2001 terrorist attack in the US.

One of his students, from Vietnam, was particularly concerned that Khaledi would go to an international conference and never be able to return. “He used to bring citizenship forms, and he would fill out what he could and sit them on my desk,” Khaledi says.

Khaledi knows that many students are considering the challenges versus benefits of staying in the US or going elsewhere. He remembers a particular Iranian student who was top notch, with perfect English and a stellar record, who ended up going to another country because she couldn’t get a US visa. “You want these people to come here,” he says.

“I don’t see what we gain by excluding people. We’re talking about scientists; we are not talking about politicians. You remove the politics from it, and we all benefit.”

You might also like...

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Linkedin

- Share on Reddit

This article has been sent to the following recipient:

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter

The power is now in your (nitrile gloved) hands

Sign up for a free account to get more articles. or choose the acs option that’s right for you..

Already have an ACS ID? Log in

Create a free account To read 6 articles each month from

Join acs to get even more access to.

The Internationalization of U.S. Doctorate Education

...foreign student demand for U.S. doctorate programs, especially in science and engineering, has grown in countries where undergraduate education has expanded.

One of the most significant transformations in U.S. graduate education and the international market for highly-trained workers in science and engineering during the last quarter century is the representation of students from outside of the United States among the ranks of doctorate recipients from U.S. universities. In all but the life sciences, the foreign share of Ph.D. recipients now equals or exceeds the share from the United States. Students from outside the United States accounted for 51 percent of Ph.D. recipients in science and engineering in 2003, up from 27 percent in 1973. In 2003, doctorate recipients from outside the United States accounted for 50 percent of Ph.D.s awarded in the physical sciences, 67 percent in engineering, and 68 percent in economics.

In Internationalization of U.S. Doctorate Education (NBER Working Paper No. 14792 ), authors John Bound , Sarah Turner , and Patrick Walsh highlight the importance of changes in demand among foreign-born students in explaining the growth and distribution of doctorates awarded in science and engineering. They find in particular that foreign students' demand for U.S. doctorate programs, especially in science and engineering, has grown in countries where undergraduate education has expanded. Many foreign students specialize in those fields as undergraduates: in 2004, China awarded 60 percent of its undergraduate degrees in science and engineering, while the concentrations were lower in European countries including in Great Britain at 35 percent, and in the United States at 32 percent.

Beyond the increase in numbers of foreign undergraduate students prepared for graduate work, periodic 'demand shocks' affect foreign representation in U.S. doctorate programs. These include increased birth-cohort size and undergraduate degree attainment in countries of origin, development of networks among successful immigrants in the United States, and political transformations, such as the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, the fall of the Shah and American hostage crisis in Iran in 1979, and normalization of relations with China in the early 1980s. However, there is little evidence to suggest that these demand shocks have led to direct 'crowd-out' or reductions in degree attainment among U.S. residents, the authors find. For example, the large influx of Chinese students in the early 1980s had no discernible impact on the number of students from the United States or any other nation receiving doctorates in the sciences. Instead, the overall number of doctorates increased, with foreign student representation increasing particularly at less highly ranked U.S. programs.

While there is no direct evidence of crowd out in doctoral programs, the influx of foreigners into the science and engineering labor market in the United States has changed the return to investment in advanced degrees in science and engineering for U.S. residents. Bound, Turner, and Walsh suggest that these effects explain why domestic demand for programs in science and engineering has remained stagnant or declined in the period of increasing foreign demand. Over the last quarter century, the relative returns to U.S. students from advanced study in the sciences have not increased. Labor market data show that the earnings of new advanced degree recipients in science-and-engineering fields trail earnings for other college-educated workers. At U.S. universities, the extended duration of low-wage post-doctorate appointments has lengthened the time between entry and completion of graduate school; the salary gap between senior and junior faculty has widened; and permanent university employment is uncertain.

-- Sarah H. Wright

Researchers

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 13 November 2019

PhDs: the tortuous truth

- Chris Woolston 0

Chris Woolston is a freelance writer in Billings, Montana.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Getting a PhD is never easy, but it’s fair to say that Marina Kovačević had it especially hard. A third-year chemistry student at the University of Novi Sad in Serbia, she started her PhD programme with no funding, which forced her to get side jobs bartending and waitressing. When a funded position came up in another laboratory two years later, she made an abrupt switch from medicinal chemistry to computational chemistry. With the additional side jobs, long hours in the lab, and the total overhaul of her research and area of focus, Kovačević epitomizes the overworked, overextended PhD student with an uncertain future.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 575 , 403-406 (2019)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7

Woolston, C. Nature 550 , 549–552 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Auerbach, R. P. et al. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127 , 623–638 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Oswalt, S. B. et al. J. Am. Coll. Health https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1515748 (2018).

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L. & Hubbard, K. Int. J. Dr Stud. 13 , 361–388 (2018).

Download references

Related Articles

- Institutions

‘Shrugging off failure is hard’: the $400-million grant setback that shaped the Smithsonian lead scientist’s career

Career Column 15 APR 24

Citizenship privilege harms science

Comment 15 APR 24

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

Exclusive: official investigation reveals how superconductivity physicist faked blockbuster results

News 06 APR 24

Larger or longer grants unlikely to push senior scientists towards high-risk, high-reward work

Nature Index 25 MAR 24

A fresh start for the African Academy of Sciences

Editorial 19 MAR 24

Ready or not, AI is coming to science education — and students have opinions

Career Feature 08 APR 24

After the genocide: what scientists are learning from Rwanda

News Feature 05 APR 24

How can we make PhD training fit for the modern world? Broaden its philosophical foundations

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Assistant Professor - Cell Physiology & Molecular Biophysics

Opportunity in the Department of Cell Physiology and Molecular Biophysics (CPMB) at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC)

Lubbock, Texas

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate- Curing Brain Tumors

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Energy AI / Grid Modernization / Hydrogen Energy / Power Semiconductor Concentration / KENTECH College

21, Kentech-gil, Naju-si, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea(KR)

Korea Institute of Energy Technology

Professor in Macromolecular Chemistry

The Department of Chemistry - Ångström conducts research and education in Chemistry. The department has 260 employees and has a turnover of 290 mil...

Uppsala (Stad) (SE)

Uppsala University

Postdoctoral research fellow focused on generative modelling of synthetic cohorts in brain research

Lunds universitet, Institutionen för kliniska vetenskaper Malmö Lund University was founded in 1666 and is repeatedly ranked among the world’s top ...

Lund (Stad), Skåne (SE)

Lund University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Skip to Main Content

- Media Center

Resource Library

More U.S. Scientists and Engineers Are Foreign-Born

January 11, 2011

Focus Areas

Inequality and Poverty World and U.S. Population Trends

Scientists and engineers working in the United States are increasingly likely to be foreign-born, primarily because the United States continues to attract large numbers of skilled workers from abroad. In an article in the journal Demography , Vanderbilt University professor Mariano Sana reported that the ratio of foreign-born to U.S.-born scientists and engineers doubled in little more than a decade (see figure). 1 In 1994, there were 6.2 U.S.-born workers for every foreign-born worker in science and engineering occupations. By 2006, the ratio was 3.1 to 1.

More than 60 percent of foreign-born scientists and engineers in the United States in 2009 were from Asia, according to Census Bureau data analyzed by PRB. Nearly one-fourth were from India, with another one-fifth from China, the Philippines, and Taiwan.

Foreign-born residents not only expanded the U.S. high-tech workforce but helped start new businesses that have generated billions in revenue and hired tens of thousands of workers. Foreign-born entrepreneurs helped start one-fourth of all new U.S. engineering and technology business established between 1995 and 2005, including Google and eBay. In high-tech Silicon Valley, California, more than one-half of business start-ups over that period involved a foreign-born scientist or engineer; one-fourth included an Indian or Chinese immigrant. 2

Economic Growth Attracts Foreign-Born Workers

U.s. workers in science and engineering by place of birth.

Note: Includes workers with at least a bachelor’s degree. Source: Mariano Sana, Demography 47, no. 3 (2010): table 1.

What caused this shift? Were fewer U.S.-born students going into the sciences and mathematics? Did the recent wave of immigrants include more scientists than previous waves? Did U.S. immigration policy change to attract more scientists and engineers? None of these factors had a major role in boosting the proportion of foreign-born workers in these occupations, according to Sana’s research. The heavy volume of immigrants, driven by ample job opportunities in science and engineering, explained about three-fourths of the increase.

The number of foreign scientists and engineers entering the United States has ebbed and flowed along with the job opportunities in those fields. U.S. immigration policy apparently did not have a large effect on these trends. Foreign professionals may enter the country and work for up to six years under an H-1B visa, and many U.S. firms used these visas to hire foreign scientists and engineers during the dot-com boom of the 1990s. High-tech firms twice persuaded the U.S. Congress to increase the annual limit on H-1B visas (originally 65,000) to allow in more foreigners. 3 But Sana found that raising the visa ceiling did not raise the ratio of foreign-born to U.S.-born scientists and engineers. In fact, the number of visas awarded fell short of the new ceiling after the dot-com “bust” because of declining job opportunities. The ratio of foreigners to U.S.-born in these jobs declined slightly in the early 2000s, but has generally trended upward.

U.S. Universities an Important Conduit

Many foreign-born scientists and engineers arrive with advanced degrees in their field, but the majority are products of U.S. graduate programs. The NSF reports that about two-thirds of foreign doctoral students stay in the United States at least five years after earning a degree from a U.S. university.

Foreign-born students are earning an increasing percentage of U.S. graduate science and engineering degrees. They earned 40 percent of U.S. doctoral degrees in science and engineering in 2003, and they were responsible for most of the growth in doctoral degrees in these fields between 1985 and 2005. 4 Just four countries—China, India, South Korea, and Taiwan—accounted for one-half of the doctorates awarded to foreign-born students during that period.

Recession and Globalization May Slow Rise of Foreign Scientists and Engineers

The economic downturn appears to dampen the enthusiasm for coming to the United States to study and work. Enrollment of new graduate students in science and engineering dropped 2 percent between 2008 and 2009. 5 Because science and engineering students make up nearly one-half of all foreign students in U.S. universities, this drop may also signal smaller increases—or even decreases—in overall foreign enrollment in the near future.

Some foreign professionals leave their U.S. jobs to work in their own or another country, although there are no solid estimates of how many are returning or whether the number is increasing. 6 This return migration reflects economic recessions in the United States as well as expanding opportunities elsewhere. The economies of India, China, South Korea, and many other developing countries, for example, are growing more rapidly than the U.S. economy. Because immigrants from these countries are more likely to be highly educated, they often can take advantage of new opportunities back home or more lucrative jobs in other countries.

Regardless of how this plays out, the foreign-born presence in U.S. science and engineering jobs remains strong and the United States still attracts the best and brightest from many countries.

- Mariano Sana, “Immigrants and Natives in U.S. Science and Engineering Occupations, 1994-2006,” Demography 47, no. 3 (2010): 801-20.

- Vivek Wadhwa et al., “America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Part I,” Duke Science, Technology & Innovation Paper , no. 23 (2007), accessed at http://ssrn.com/abstract=990152 , on Oct. 20, 2010.

- Philip Martin and Elizabeth Midgley, “Immigration: Shaping and Reshaping America,” Population Bulletin 61, no. 4 (2006).

- National Science Foundation, Science and Engineering Indicators 2010 (Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2010), accessed at www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind10/ , on Oct. 20, 2010.

- Joan Burrelli, “Foreign Science and Engineering Students in the United States,” InfoBrief (July 2010), accessed at www.nsf.gov/statistics/infbrief/nsf10324.pdf , on Oct. 20, 2010.

- Vivek Wadhwa et al., “America’s Loss Is the World’s Gain: America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Part III” (2009), accessed at www.kauffman.org/uploadedFiles/americas_loss.pdf , on Oct. 20, 2010.

Inequality and Poverty

Family-Centered Care Matters for Kids With Special Needs, but Many Families Report Challenges With Providers

The Best Years of Their Lives? Young Adults Reported More Anxiety Than Older Adults During Pandemic, Despite Lower Health Risks

Public Housing, Vouchers Open Doors to Better Child Health, New Research Suggests

PRB @ PAA 2023 Annual Meeting

Maternal Death Among U.S. Black Women

Anti-Poverty Tax Credits Linked to Declines in Reports of Child Neglect, Youth Violence, and Juvenile Convictions

Vulnerable Older Americans Aren’t Getting Adequate Care—Even With Paid Caregivers or Grown Children

Event: Data and Democracy in the Age of Disinformation

Prb @ paa 2022 annual meeting.

Center for Security and Emerging Technology

The global distribution of stem graduates: which countries lead the way.

Brendan Oliss

Cole McFaul

Jaret C. Riddick

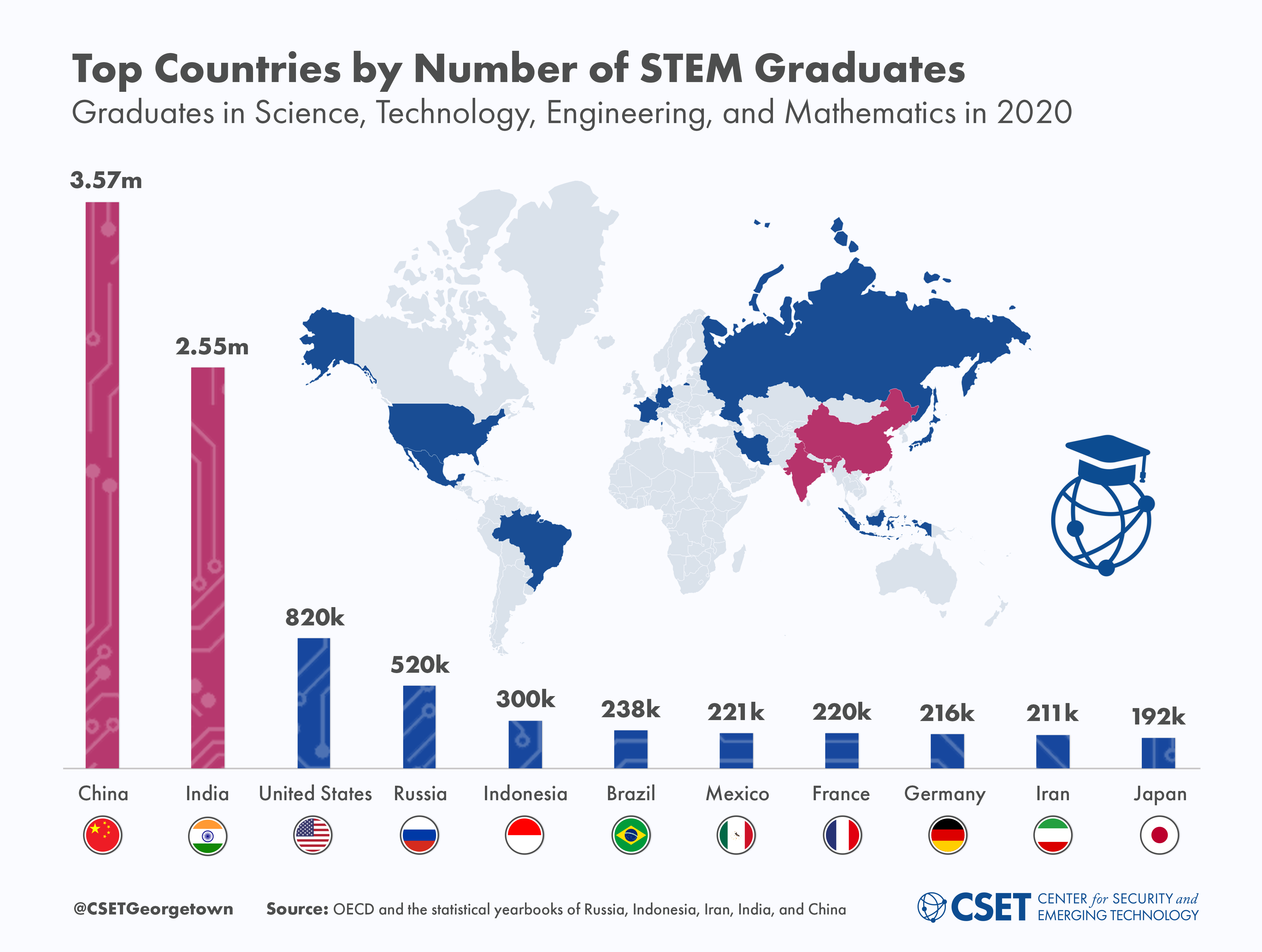

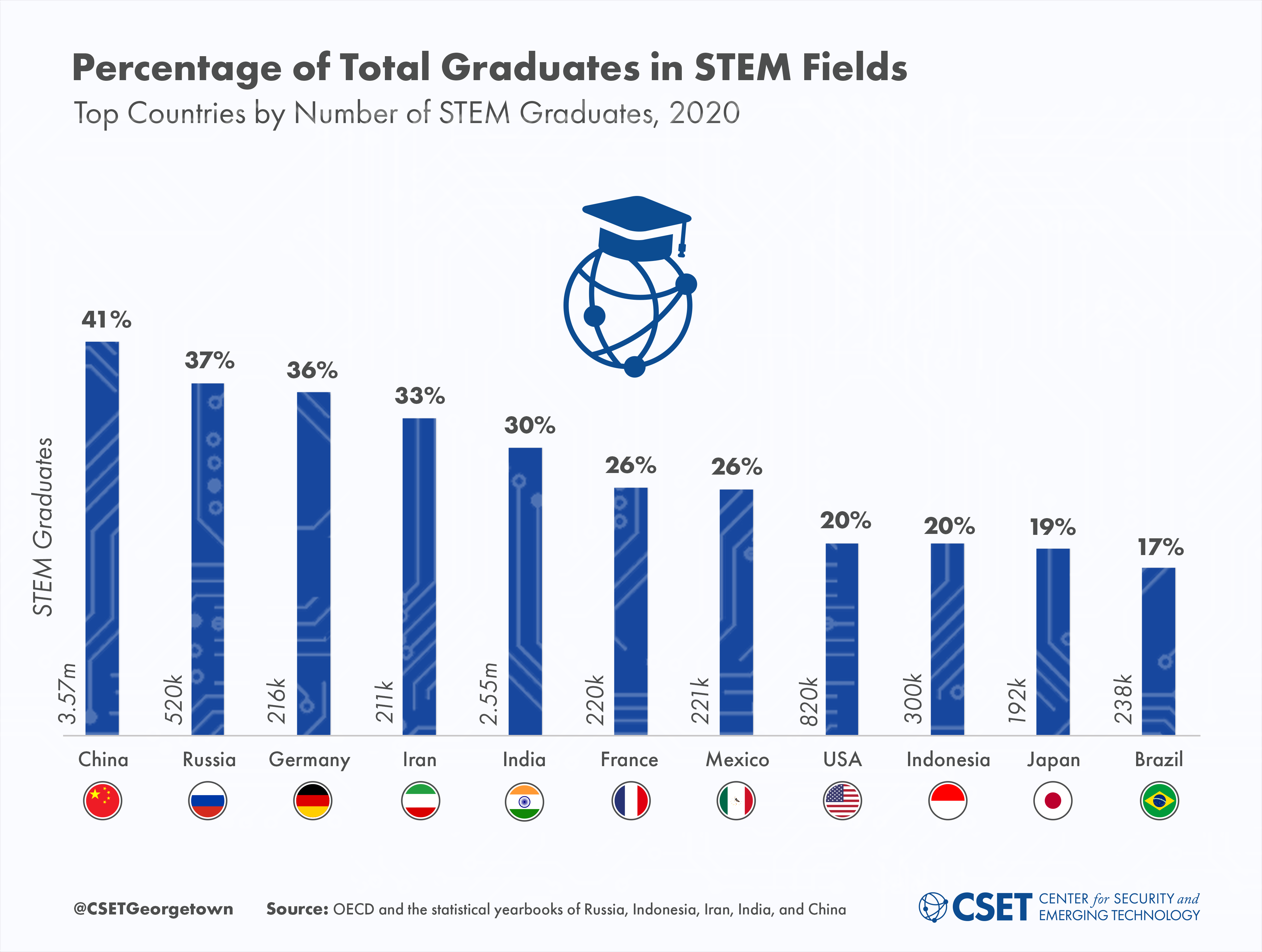

Discover how the global landscape of STEM graduates is shifting, potentially reshaping the future of innovation and education worldwide. This blog post analyzes recent education data from the countries with the most graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields. For each of the top eleven countries by number of STEM graduates, we present the total number of STEM graduates as well as STEM graduates as a percentage of total graduates in 2020.

On October 30, 2023, the Biden administration released the Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which demonstrated the White House’s commitment to expanding the United States’ AI workforce and AI education ecosystems. Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) graduates can aid the development of a highly skilled technical workforce, enabling technological innovation and economic growth. As tech competition intensifies globally, demand for STEM talent will continue to rise. Countries with more STEM graduates are better poised to make technological breakthroughs in fields like artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and advanced materials.

In this blog post, we analyze the current global distribution of STEM graduates using data from 2020, the most recent education statistics available across the countries included in this study. This analysis serves as an update to key figures originally published in the 2016 World Economic Forum Human Capital report.

Examining Total STEM Graduates by Country

Throughout most of the 20th century, the United States and Europe—particularly Russia, Germany, the UK, and France—were considered the global centers of scientific and technological education. In the last few decades, however, new players have emerged. In Asia, countries like China, India, South Korea, and Japan rapidly expanded their STEM education programs and today produce significant numbers of graduates in STEM fields.

Figure 1 below shows the top eleven countries by number of STEM graduates in 2020. To perform this analysis, we draw on national education data and rely on the International Standard Classification Education framework developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as well as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s designation of STEM fields . We further describe our approach to this study in the “Methods” section below.

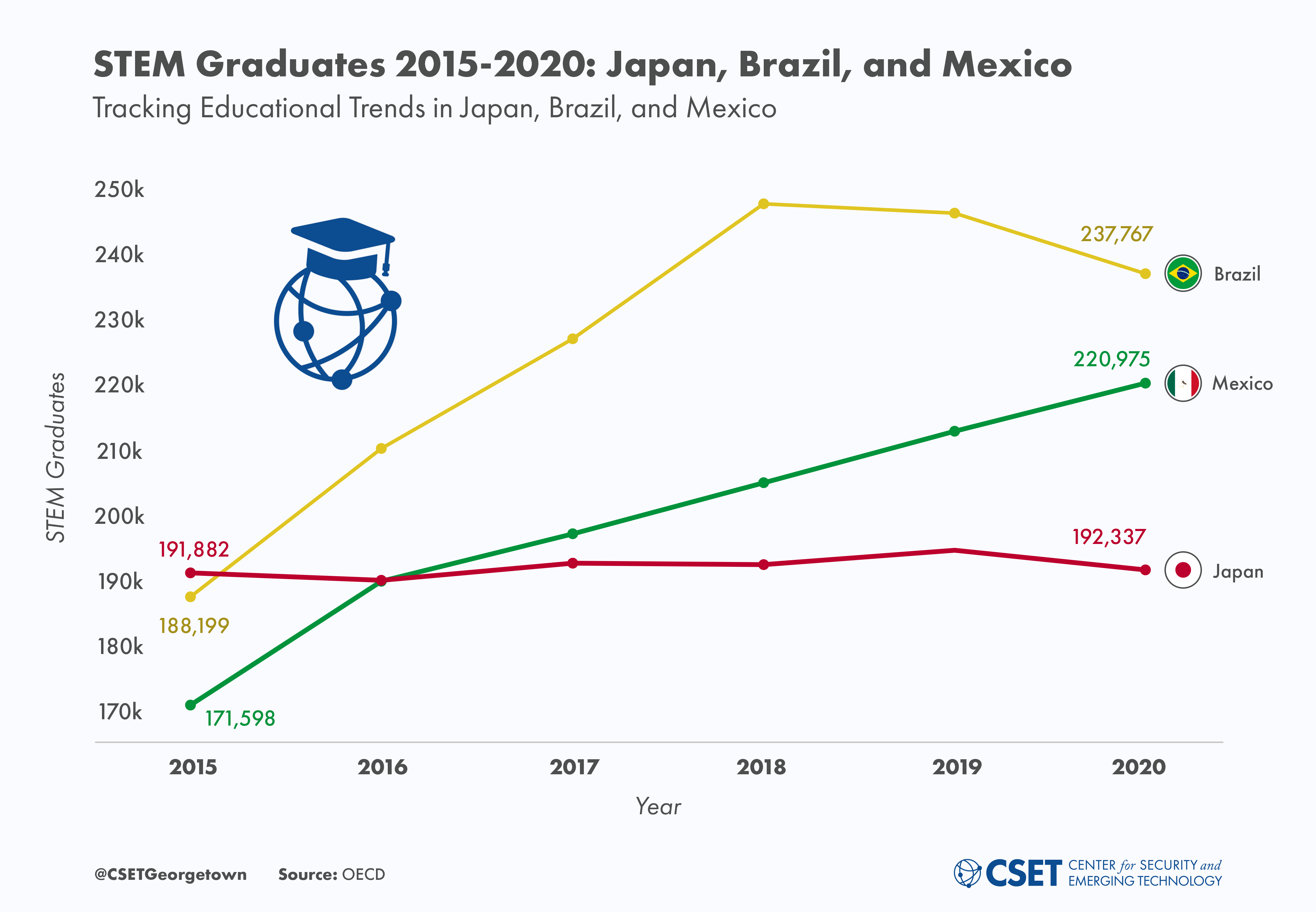

Figure 1 reveals a new shift in the global distribution of STEM graduates compared to the 2016 World Economic Forum report. The WEF report identified China, India, the United States, Russia, Iran, Indonesia, and Japan as the top seven STEM graduate-producing countries in the world. As of 2020, however, we find that Brazil and Mexico surpassed Iran and Japan in the number of graduates in STEM fields.

Following the boom in STEM education in Asia over the last several decades, the rapid growth of STEM graduates in China, India, Japan, and South Korea has received significant attention. Indeed, although each of these countries experienced tremendous growth in the number of STEM graduates over the past 50 years, new players like Brazil and Mexico are making significant strides in increasing the number of students graduating in STEM fields.

Figure 2 depicts the increase in STEM graduates in Brazil, Mexico, and Japan from 2015 to 2020. While Japan’s output of STEM graduates is relatively constant over the time period, Brazil’s number of graduates grew by ~26% and Mexico’s grew by ~30%. As higher numbers of STEM graduates have historically been an indicator of future economic growth , these strides in advancing STEM education suggest that Brazil and Mexico may be positioned for future success.

Comparing Percentage of STEM Graduates for Alternate View

While the number of STEM graduates may serve as an indicator of future scientific and technological capacity, it fails to account for other differences in the STEM ecosystems of different countries. In Figure 3, we present the number of STEM graduates as a percentage of total graduates for each country to provide another perspective through which to understand the differences between countries’ STEM education ecosystems.

As shown in Figure 3, China leads in the percentage of students in STEM fields, with over 40 percent of college graduates obtaining a STEM degree. Not far behind, Russia, Germany, Iran, and India all produced more than 30 percent of graduates in STEM fields, with Germany closely rivaling Russia. Moreover, just 20 percent of graduates in the United States obtain a STEM degree, behind both Mexico and France.

Fostering U.S. Leadership in STEM

As the United States aims to maintain its leadership in talent in an increasingly competitive world, policymakers should foster STEM education at home and leverage its attractiveness to foreign talent from abroad. To expand the United States’ domestic supply of STEM graduates, policymakers should work to increase the accessibility of STEM programs at community colleges and 4-year institutions . Additionally, the United States should ensure that individuals with advanced degrees in STEM can continue to immigrate to the United States, as the recent EO endeavors to enable via H1-B processing and other reforms. As the United States seeks to attract talent from abroad, it is important to understand global shifts in the supply of STEM graduates. Particular attention should be paid to the rise of STEM talent in emerging market economies such as Mexico and Brazil. Recognizing these global shifts, the United States must continue to invest in building and attracting a highly skilled workforce, in order to maintain a thriving pool of STEM graduates for innovation, discovery, and national security. In doing so, the country will be better positioned to improve its competitiveness in critical, emerging technologies, and ultimately benefit from future progress in STEM.

More on Methods

For this analysis, we adopted widely-accepted standards for the classification of education statistics to collect and analyze our data. UNESCO and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) define “STEM fields” as subjects in information and communication technology, engineering, construction, manufacturing, natural sciences, mathematics, and statistics. We adopted these fields, along with UNESCO’s standard classification of “tertiary education,” which designates the international equivalents of associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees, to identify and count STEM graduates.

Related Content

China is fast outpacing u.s. stem phd growth.

Since the mid-2000s, China has consistently graduated more STEM PhDs than the United States, a key indicator of a country’s future competitiveness in STEM fields. This paper explores the data on STEM PhD graduation rates… Read More

Leading the Charge: A Look at the Top-Producing AI Programs in U.S. Colleges and Universities

Data Snapshots are informative descriptions and quick analyses that dig into CSET’s unique data resources. This five-part series uses data from the U.S. Department of Education and other select sources to complement existing CSET work… Read More

Training Tomorrow’s AI Workforce

Community and technical colleges offer enormous potential to grow, sustain, and diversify the U.S. artificial intelligence (AI) talent pipeline. However, these institutions are not being leveraged effectively. This report evaluates current AI-related programs and the… Read More

The Race for U.S. Technical Talent

Technical talent is vital to innovation and economic growth, and attracting these highly mobile workers is critical to staying on the cutting-edge of the technological frontier. Conventional wisdom holds that the defense community generally struggles… Read More

Building the Cybersecurity Workforce Pipeline

Creating adequate talent pipelines for the cybersecurity workforce is an ongoing priority for the federal government. Understanding the effectiveness of current education initiatives will help policymakers make informed decisions. This report analyzes the National Centers… Read More

U.S. Demand for AI Certifications

This issue brief explores whether artificial intelligence and AI-related certifications serve as potential pathways to enter the U.S. AI workforce. The authors find that according to U.S. AI occupation job postings data over 2010–2020, there… Read More

This website uses cookies.

Privacy overview.

- Society ›

Education & Science

Number of international students in the U.S. 2022/23, by country of origin

International students, international students and college, number of international students studying in the united states in 2022/23, by country of origin.

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

November 2023

United States

academic year 2022-2023

Other statistics on the topic College & University

Number of students enrolled in higher education in France 1980-2023

Total number of students at university in France 2022-2023, by degree course

Distribution of foreign students in France 2022-2023, by country

Unemployment rate of French young graduates from one to four years 2022, per degree

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Other statistics that may interest you

- Leading places of origin for Intensive English Program students in the U.S. 2015

- Breakdown of postsecondary enrollment in the U.S. 1980-2021, by race

- U.S. American Indian/Alaska Native undergraduate enrollment, by gender 1976-2010

- Asian/Pacific Islander undergraduate enrollment in the U.S., by gender 1976-2010

- Higher education students from African countries in Russia 2010-2021

- Higher education students from Africa in Russia 2021, by country

- Average amount of time U.S. students spent studying abroad 2020/21

- Regions with the most U.S. students studying abroad 2020/21

- International students in the U.S. 2003-2023

- International students in the U.S. 2004-2023, by academic level

- Undergraduate enrollment in 2-year colleges U.S. 2021, by ethnicity

- Share of college students 2009, by degree attainment and degree completion status

- Primary funding sources for international students U.S. 2022

- Countries with the most U.S. students studying abroad 2021/22

- Share of students receiving student aid in the U.S. 2020-2021, by type of aid

- Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers U.S. 1976-2031, by gender

- Post-baccalaureate enrollment U.S. 1976-2031, by attendance type

- Enrollment/projections in U.S. 2-year postsecondary institutions 1970-2031, by gender

- Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers U.S. 1976-2021, by ethnicity

- Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. 1970-2031, by attendance

- African-American undergraduate enrollment numbers, by gender 1976 to 2011

- Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers in the U.S., by institution type 1976-2010

- Number of degrees in visual and performing arts in the U.S. 1999-2013

- Foreigners enrolled in university institutions in Spain 2023, by origin

- Number of college and university graduates in China 2022, by region

- Number of international students in higher education in Malaysia 2022, by country

- Number of registered university students in Finland 2012-2022

- Number of granted student residence permits in Sweden 2020, by citizenship

- Number of Taiwanese students studying in the U.S. 2012/13-2022/23

- Number of foreign students in Italy 2014-2020

- Tertiary students enrolled in agriculture in Ghana 2019, by type of institution

- United Kingdom: perceptions of drinking at university prior to starting as of 2017/18

- University application rate in England, by ethnic group

- Hispanic undergraduate enrollment numbers U.S. 1980-2021, by gender

- Enrollment status of the Hispanic population, by type U.S. 2022

- Enrollment rate of the Hispanic population, by sex and age U.S. 2022

- Share of Native American students at tribally controlled colleges U.S. 2018

- U.S. college majors with the highest participation of Hispanic students 2015

- Leading U.S. college majors for Hispanics, by earnings 2015

- Worst 10 U.S. college majors for Hispanics, by earnings 2013

- Average spending per student at U.S. public community colleges 2003-2013

- Average revenue per student in a public community college in the U.S. 2003-2013

- Number of Pell Grant recipients in the U.S. 2013/14, by state

Other statistics that may interest you Statistics on

About the industry

- Premium Statistic Leading places of origin for Intensive English Program students in the U.S. 2015

- Basic Statistic Breakdown of postsecondary enrollment in the U.S. 1980-2021, by race

- Basic Statistic U.S. American Indian/Alaska Native undergraduate enrollment, by gender 1976-2010

- Basic Statistic Asian/Pacific Islander undergraduate enrollment in the U.S., by gender 1976-2010

- Basic Statistic Higher education students from African countries in Russia 2010-2021

- Basic Statistic Higher education students from Africa in Russia 2021, by country

- Basic Statistic Average amount of time U.S. students spent studying abroad 2020/21

- Basic Statistic Regions with the most U.S. students studying abroad 2020/21

- Basic Statistic International students in the U.S. 2003-2023

- Basic Statistic International students in the U.S. 2004-2023, by academic level

About the region

- Basic Statistic Undergraduate enrollment in 2-year colleges U.S. 2021, by ethnicity

- Basic Statistic Share of college students 2009, by degree attainment and degree completion status

- Basic Statistic Primary funding sources for international students U.S. 2022

- Basic Statistic Countries with the most U.S. students studying abroad 2021/22

- Basic Statistic Share of students receiving student aid in the U.S. 2020-2021, by type of aid

- Basic Statistic Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers U.S. 1976-2031, by gender

- Basic Statistic Post-baccalaureate enrollment U.S. 1976-2031, by attendance type

- Premium Statistic Enrollment/projections in U.S. 2-year postsecondary institutions 1970-2031, by gender

- Basic Statistic Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers U.S. 1976-2021, by ethnicity

- Premium Statistic Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. 1970-2031, by attendance

Selected statistics

- Basic Statistic African-American undergraduate enrollment numbers, by gender 1976 to 2011

- Basic Statistic Post-baccalaureate enrollment numbers in the U.S., by institution type 1976-2010

- Basic Statistic Number of degrees in visual and performing arts in the U.S. 1999-2013

Other regions

- Basic Statistic Foreigners enrolled in university institutions in Spain 2023, by origin

- Premium Statistic Number of college and university graduates in China 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Number of international students in higher education in Malaysia 2022, by country

- Basic Statistic Number of registered university students in Finland 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of granted student residence permits in Sweden 2020, by citizenship

- Premium Statistic Number of Taiwanese students studying in the U.S. 2012/13-2022/23

- Basic Statistic Number of foreign students in Italy 2014-2020

- Premium Statistic Tertiary students enrolled in agriculture in Ghana 2019, by type of institution

- Premium Statistic United Kingdom: perceptions of drinking at university prior to starting as of 2017/18

- Basic Statistic University application rate in England, by ethnic group

Related statistics

- Basic Statistic Hispanic undergraduate enrollment numbers U.S. 1980-2021, by gender

- Basic Statistic Enrollment status of the Hispanic population, by type U.S. 2022

- Basic Statistic Enrollment rate of the Hispanic population, by sex and age U.S. 2022

- Premium Statistic Share of Native American students at tribally controlled colleges U.S. 2018

- Basic Statistic U.S. college majors with the highest participation of Hispanic students 2015

- Basic Statistic Leading U.S. college majors for Hispanics, by earnings 2015

- Basic Statistic Worst 10 U.S. college majors for Hispanics, by earnings 2013

- Premium Statistic Average spending per student at U.S. public community colleges 2003-2013

- Premium Statistic Average revenue per student in a public community college in the U.S. 2003-2013

- Basic Statistic Number of Pell Grant recipients in the U.S. 2013/14, by state

Further related statistics

- Basic Statistic U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels, private four-year colleges 2006-2022

- Basic Statistic College graduation rate , by acceptance rate of U.S. college institution 2013

- Basic Statistic Highest earning increase from obtaining a graduate degree in the U.S. 2013

- Basic Statistic College majors with the highest participation of Asian students in the U.S. 2009

- Basic Statistic U.S. college majors with the highest participation of African-American students 2009

- Basic Statistic Least popular college majors in the U.S. by gender 2009

- Basic Statistic Share of student loans provided in the U.S. 2001-2023, by source

- Basic Statistic Amount of student loans offered, by federal loan program U.S. 2017-2023

- Premium Statistic Median income of arts majors by study focus in the U.S. 2013

- Premium Statistic Median income of communications and journalism majors by study focus in the U.S. 2013

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

- U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels, private four-year colleges 2006-2022

- College graduation rate , by acceptance rate of U.S. college institution 2013

- Highest earning increase from obtaining a graduate degree in the U.S. 2013

- College majors with the highest participation of Asian students in the U.S. 2009

- U.S. college majors with the highest participation of African-American students 2009

- Least popular college majors in the U.S. by gender 2009

- Share of student loans provided in the U.S. 2001-2023, by source

- Amount of student loans offered, by federal loan program U.S. 2017-2023

- Median income of arts majors by study focus in the U.S. 2013

- Median income of communications and journalism majors by study focus in the U.S. 2013

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Number of foreign college students staying and working in u.s. after graduation surges, federal training program sees 400% increase in foreign students graduating and working in stem fields from 2008 to 2016.

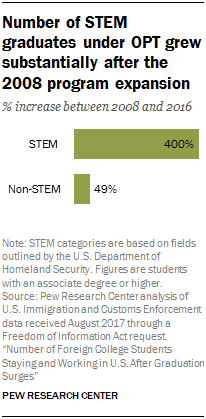

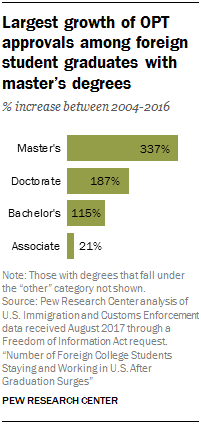

Many foreign STEM graduates enrolled with OPT after executive actions in 2008 and 2016 initially doubled (29 months), then later tripled (36 months), the maximum length of employment for foreign students with STEM degrees. The number of foreign STEM graduates participating in OPT grew by 400% since the first employment extension was introduced in 2008.

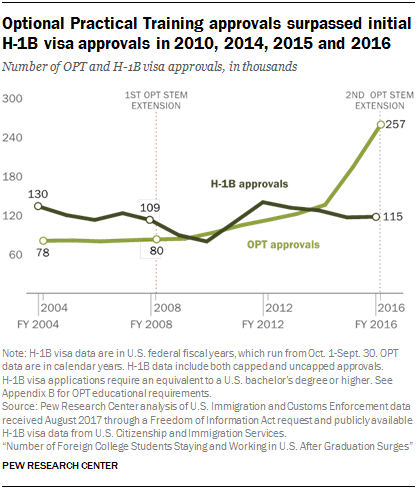

OPT is one mechanism by which the U.S. can compete with other countries for top talent. It is less well-known than the H-1B visa program – which enables U.S. companies to hire highly skilled foreign workers and is the nation’s largest temporary employment visa program – yet OPT approvals actually outnumbered initial H-1B visa approvals in recent years. 2 In addition, OPT’s eligible population has been on the rise: Between 2008 and 2016, new college enrollments among foreign students on F-1 visas grew 104%.

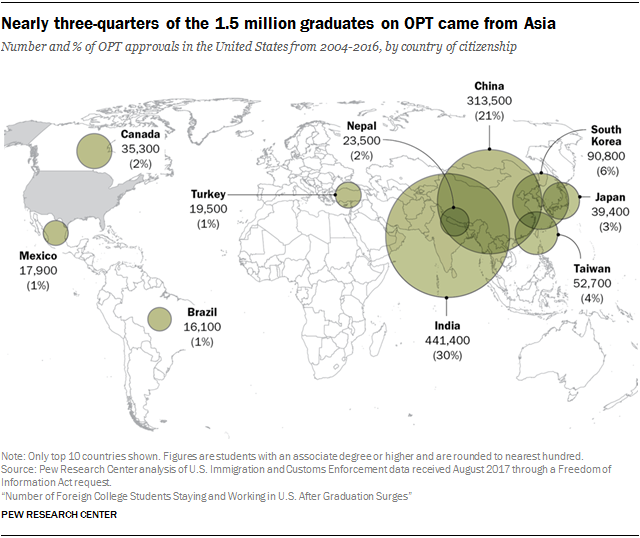

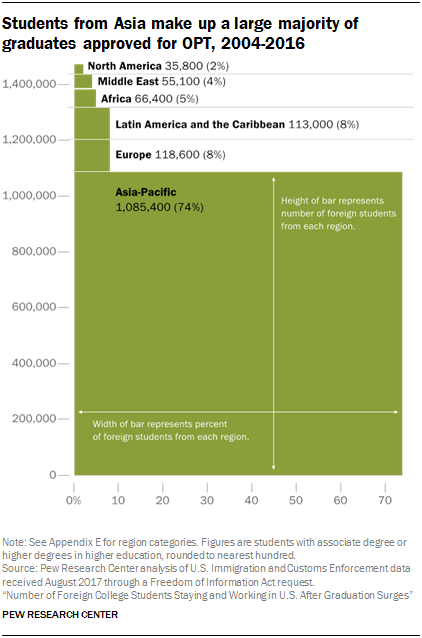

Foreign students obtaining authorization to remain and work in the U.S. after graduation come from all corners of the globe, but the majority of them hold citizenship in Asia. Students from India, China and South Korea made up 57% of all OPT participants between 2004 and 2016.

Although the data referenced in this report cover F-1 visa holders approved for OPT participation between 2004 and 2016, only those who pursued degrees in higher education (associate, bachelor’s, master’s or doctorate) are included in the analysis.

This data made it possible to map where foreign college graduates came from and where they were going – both for their education and their OPT employment. Major metro areas in the U.S. tend to attract large numbers of foreign students and also keep a significant share as OPT enrollees. By contrast, smaller-sized metro areas often see local foreign graduates relocate elsewhere as part of OPT employment.

View our interactive to see where foreign student graduates under OPT worked in the United States, by the top 61 metro areas with the largest number of graduates approved for OPT between 2004 and 2016.

Newly enrolled foreign students surge at U.S. colleges and universities from 2008 to 2016

Only foreign students enrolled full-time at U.S. colleges and universities are eligible for OPT. The most common type of visa for foreign students is the F-1 academic student visa, which is typically given to those pursuing degrees in higher education. The number of newly enrolled foreign students with F-1 visas at U.S. colleges and universities has grown dramatically in recent years, increasing from 138,500 in 2004 to 364,000 in 2016. Much of this growth happened after the start of the Great Recession at the end of 2007. Between 2008 and 2016, new foreign student enrollment has increased by 104%, far outpacing overall college enrollment growth, which was 3.4% during the same period, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. This increase was greatest in public colleges and universities, which faced budget cuts during the recession and began to rely more heavily on tuition from foreign students.

For more in-depth analysis, see this Pew Research Center study on foreign students in the U.S. and its related fact sheet .

Foreign STEM graduates make up majority of OPT participants

The overall surge in the number of foreign college graduates participating in OPT is largely attributable to a 400% increase in STEM graduates approved to temporarily work in the U.S. since 2008.

Among OPT participants with doctoral degrees, 78% studied in a STEM field, while among those with master’s degrees the share was 60%. STEM graduates made up smaller shares of OPT participants with bachelor’s (33%) and associate degrees (12%).

The top fields of study among OPT participants with doctorates were engineering (34%), physical sciences (16%) and biological and biomedical sciences (13%). 4 Foreign graduates with master’s degrees concentrated in the areas of engineering (27%), computer and information sciences and support services (22%), and business, management, marketing, and support services (22%). OPT enrollees with bachelor’s degrees most often completed majors in business, management, marketing, and support services (32%), engineering (12%), and the social sciences (9%).

OPT approvals outpaced initial H-1B visa approvals in recent years

Transitioning to the H-1B visa is one of the pathways that foreign graduates can pursue to stay in the U.S. once their OPT period expires. 12 However, there is no guarantee that H-1B visas will be available for employers who want to sponsor foreign graduates working under OPT. In recent years, the number of applications for this visa program has exceeded its annual cap, and a lottery system was put in place to award the visas.

As yearly H-1B visa applications surpass the annual cap, OPT is becoming a more popular pathway for foreign graduates of U.S. higher educational institutions to stay in the country

The Optional Practical Training program (OPT) was developed to allow F-1 visa holders to gain practical work experience after graduating from a U.S. college or university. In 2007 and 2013 , Congress did not pass expansive reforms to the H-1B visa program as part of comprehensive immigration reform bills. At the time, there were proposals to increase the number of H-1B visas as well as legislation to add 55,000 green cards exclusively for foreign student graduates with a STEM degree. With no legislation passed on the H-1B visa program, the residency limit for OPT was extended an additional 24 months for those with a STEM degree.

In light of economic concerns and pressure raised by high-tech professionals , members of Congress and U.S. educational institutions, the George W. Bush and Obama administrations expanded the OPT program for those with STEM degrees in 2008 and 2016, respectively. This expansion was intended to prevent a “ brain drain ,” addressing U.S. concerns of losing students unable to obtain an H-1B visa.

The federal government also established the “cap-gap extension,” which extends the OPT period authorization for U.S. foreign student graduates whose work authorization has expired. This extension allows foreign graduates to continue residing in the U.S. if they are attempting to change status to an H-1B visa. Only those with pending or approved H-1B visa petitions are granted cap-gap extension, valid until the beginning of the government’s fiscal year (Oct. 1).

With these policy developments, the OPT program has become a more popular pathway that foreign students on F-1 visas are taking to remain in the U.S. after graduation. Foreign students are now given multiple chances to adjust status to the H-1B visa program, which they can then use to potentially obtain a green card . H-1B visas for private companies are awarded to employers on a first-come, first-served basis, with applications accepted each year beginning in April. Employers that are institutions of higher education, nonprofits or government research institutions are exempted from the cap through the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act of 2000. Those OPT participants without STEM degrees have two opportunities to find employers to sponsor them under the H-1B visa program (one during the year of graduation and the other during their 12 month OPT period). OPT participants with STEM degrees could have four chances to get sponsored for an H-1B visa because of the additional 24 months that they receive.

More recently, a lawsuit filed against the Department of Homeland Security by the Washington Alliance of Technology Workers (WashTech) contested the validity of the STEM OPT extension program that started in 2008. It was dismissed after a new rule by the Obama administration was issued on May 10, 2016.

Majority of foreign student graduates working under OPT are from Asia

In terms of country of citizenship, graduates from India made up the largest share of those authorized to work under the OPT program during this period, with 441,400 (30% of the total). Students from China came second at 313,500 (21%), followed by South Koreans at 90,800 (6%).

Among citizens of India, STEM graduates made up the majority of OPT participants. Between 2004 and 2016, the number of students from India graduating with STEM degrees increased 658%, compared with a 93% increase for Indian students with non-STEM degrees.

Foreign graduates with master’s degrees drive OPT’s growth

This rapid increase in master’s degree holders took place almost exclusively in the wake of a 2008 revision to OPT that enabled STEM graduates work an additional 17 months in the U.S. The contrast before and after the Bush-era revision is stark: Between 2004 and 2007, the number of master’s degree OPT enrollees decreased by 7%, whereas between 2008 and 2016 it increased by 322%.

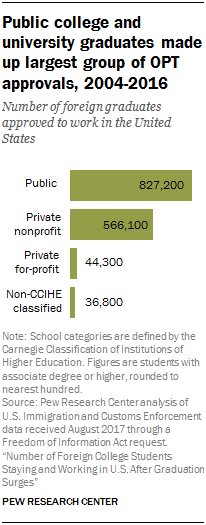

Most foreign students enrolled in OPT attended public colleges

Despite these overall percentages, the three top sources of OPT enrollees between 2004 and 2016 are all private, nonprofit colleges: the University of Southern California (27,100), New York University (26,800) and Columbia University (22,600).

The top public college for OPT participants is City University of New York’s Bernard M. Baruch College (18,500). Other public schools that graduated significant numbers of OPT enrollees include University of Michigan at Ann Arbor (13,700), University of California, Los Angeles (13,600), and University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (13,600).

Where OPT participants work in the United States

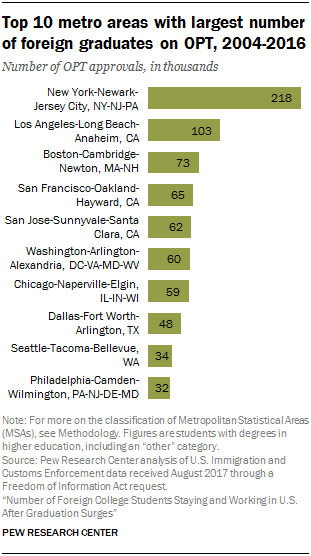

The New York-Newark-Jersey City metro area had the largest cumulative population of OPT participants (218,400). 16 That was followed by the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim (103,600) and Boston-Cambridge-Newton metro areas (73,000).

New York’s dominance can be explained in part by its ability to retain foreign students graduating from local colleges: 85% of foreign students graduating from New York-area schools stayed in the metro region to work under OPT between 2004 and 2016. In the Los Angeles and Boston areas, the shares were 78% and 72%, respectively. The Seattle (84%) and Honolulu areas (83%) actually outperformed Los Angeles and Boston in terms of the share of local foreign students retained through OPT.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the Springfield, Illinois, metro area retained the lowest share (7%) of foreign graduates who attended schools in its area. The Carbondale-Marion, Illinois, and Beaumont-Port Arthur, Texas, areas were next above it at 20% and 23%, respectively.

Across U.S. metro areas, OPT has resulted in both net “importers” and net “exporters” of foreign college graduates. New York topped the list for attracting the most foreign students who graduated from schools outside its metro area, with 74,000 students coming into the area for work between 2004 and 2016. Three California metro areas followed: San Jose (44,500), San Francisco (33,700) and Los Angeles (27,800). The San Jose metro, however, had the largest share (71%) of foreign graduates working in the area on OPT who graduated from other metros. This was followed by the Kansas City, Missouri (69%), and Peoria, Illinois (66%), areas.