- Scriptwriting

What is Context — Definition and Examples for Writers

C ontext has the ability to change the meaning of a story and how we view its characters — but what is context? We’re going to answer that question by looking at examples from The Office, In Cold Blood and more. We’ll also look at some tips and tricks for how you can effectively implement this necessary element in your own stories. By the end, you’ll know why context is so important and how to apply it in a variety of different ways. But before we jump into our examples, let’s define context.

Content vs Context Definition

What does context mean.

Whether we realize it or not, context is all around us. It is the fundamental way we come to understand people, situations and ideas. Everything that we think, say, see, hear, and do is a response to the external stimuli of the world.

And how we regard that stimuli is largely in response to the context it’s presented to us in. For more on this idea, check out the video from the University of Auckland below.

What is Context? By University of Auckland

So you’re probably thinking, “Okay that’s fine and good and all, but what is context? Surely the meaning can’t be so vague.” Well, it is and it isn’t.

But by understanding the essential aspects of the term, we’re better prepared to apply it in meaningful ways. So without further ado, let’s dive into a formal context definition.

CONTEXT DEFINITION

What is context.

Context is the facets of a situation, fictional or non-fictional, that inspire feelings, thoughts and beliefs of groups and individuals. It is the background information that allows people to make informed decisions. Most of the time, the view of a person on a subject will be made in response to the presented context. In storytelling, it is everything that surrounds the characters and plot to give both a particular perspective. No story takes place without contextual information and elements.

Characteristics of Context:

- Information that’s presented to us

- Used in an argumentative sense

- Biased/subjective form of education

ContextUal Information

Context clues : in and out of context.

In terms of storytelling, there are only two kinds of context: narrative and non-narrative. The former gives us information on the story and the latter gives us information on everything outside of the story.

Narrative types of context include:

Narrative context is everything that explains “what’s going on” in a story. Take a comedy series like The Office for example: there are a lot of moments in the show that wouldn’t make sense without contextual information — and there just so happens to be a video that explores The Office “out of context.”

What Does Context Mean in The Office?

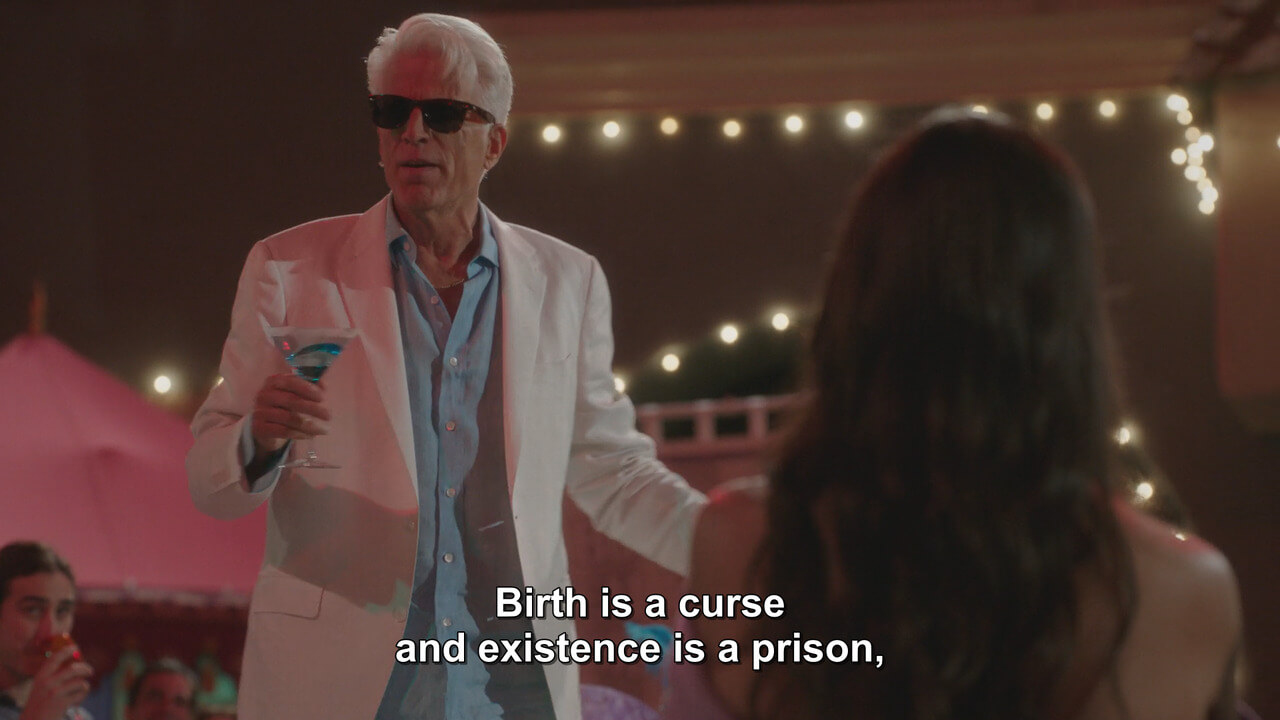

Even the most ardent fans of The Office may find themselves asking, “what in the world is going on?” when presented with these clips out of context. On social media channels, moments from film and television are often presented like this — like this screen grab from The Good Place .

Context Definition and Examples

In a sense, out of context moments have become a type of humor in and of themselves. But it’s important that we also consider how information outside of the narrative may influence our feelings on the story.

Non-narrative types of context include:

Non-narrative context is everything outside the story that influences our thoughts and opinions on the subject matter. Take Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood for example: when we learn of the circumstances outside of the subject matter, it’s impossible for us to feel the same way about the story.

In Cold Blood is an investigative novel about the murder of a family of four in Holcomb, Kansas. Capote started writing about the murders in earnest before expanding his research into a full-fledged novel — the end result speaks for itself — not only is Capote’s prose considered some of the greatest of all-time, but it also pioneered true-crime writing.

But when In Cold Blood is viewed through the context of the man who wrote it, the setting it took place in, and the precedence of its writing, the meaning is liable to change. The two convicted murderers in the novel, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, were interviewed by Capote through the writing process.

Their testimony is admitted in the novel, but filtered by Capote. So, for us to say their testimonies are veracious would be irresponsible, considering the context through which it was written.

Elsewhere, critics argue that we can only judge a piece of art based on the merit of the art itself, not the context it was created in. French literary theorist Roland Barthes said that “text” can only speak for itself and that the thoughts and feelings of the author should have no impact on its merit. For more on this “The Death of the Author” theory, watch the video below.

Exploring Context Clues • Lindsay Ellis on ‘The Death of the Author’

In recent years, many fans have criticized J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books in light of her political views. Some critics argue that her views change the meaning of the novels. Others argue that her views should have no impact. Alas, there’s no “right” answer, but it’s important to consider how context, both inside and outside of a story, can influence readers.

Context Clues Set the Stage

How to use context as exposition.

There’s a word in screenwriting that most screenwriters shutter to hear… and that word is exposition . Ah yes, the dreaded exposition — or explanatory description — has been known to sink more than a few good scripts. So, how do screenwriters use exposition effectively? Well, it starts with a need for context. When I say need, I mean the story would have no impact without it.

We imported the On the Waterfront screenplay into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software to look at an iconic scene where context is the primary force behind exposition.

In this scene, Terry details how Charley and Johnny abandoned him. This backstory, or exposition, adds the necessary context needed to make Terry’s exclamation, “I coulda’ been a contender!” impactful.

Click the link below to read the scene.

What is Context? • Read the On the Waterfront Screenplay

This explanatory description establishes a context in which we’re able to see that Terry has endured “years of abuse.” The context is further executed as Terry laments the actions of his best friends. Think of it this way: proper exposition should act like a tea-kettle; each relevant detail making the kettle hotter and hotter — or more contextual and more contextual — until — the tension is released… and whoosh, the conflict is resolved.

How to Add Context Clues

Tips for incorporating context.

Context plays a huge role in guiding the attention and emotional attachment of the audience. Say a character does something really bad, like kill another character. Our natural inclination is to vilify them, but if their actions are given context, we might view their actions as heroic.

Take Ridley Scott’s Gladiator for example: when Maximus kills Commodus, we view him as the hero. Let’s take a look at how this scene plays out:

Context Examples in Gladiator

In context, Maximus’ actions are justified. Commodus killed Maximus’ family and rigged the fight against him. As such, it makes sense that we root for his death. Here are some tips for how to incorporate context in your own works:

- Create empathy for your protagonist

- Vilify your antagonist

- Maximize conflict

- Develop themes

- Callback to prior events

By utilizing these strategies, you’ll create narrative continuity. Context relies on the impact of the past, so you should be mindful of the character’s pasts at all times when writing.

What is a Plot?

Context may be what informs our understanding of a story’s events, but it would mean nothing if there weren’t events to be informed of. Plot refers to the events and actions that take place within a story — and it’s an essential aspect of every narrative. In this next article, we look at how plot is used in Die Hard to connect narrative threads from beginning to end!

Up Next: Plot Definition and Examples →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Film Distribution — The Ultimate Guide for Filmmakers

- What is a Fable — Definition, Examples & Characteristics

- Whiplash Script PDF Download — Plot, Characters and Theme

- What Is a Talking Head — Definition and Examples

- What is Blue Comedy — Definitions, Examples and Impact

- 1 Pinterest

Definition of Context

Context is the background, environment, setting , framework, or surroundings of events or occurrences. Simply, context means circumstances forming a background of an event, idea, or statement, in such a way as to enable readers to understand the narrative or a literary piece. It is necessary for writing to provide information, new concepts, and words to develop thoughts.

Whenever writers use a quote or a fact from some source, it becomes necessary to provide their readers some information about the source, to give context to its use. This piece of information is called context. Context illuminates the meaning and relevance of the text and maybe something cultural, historical, social, or political.

Difference Between Content and Context

Content is a written text, while context is a place or situation. Although a text is not a context, content could present context within it. For example, if there occurs a statement in a certain text, it is content in its own right but it is also the context of that statement. It would show what comes next and what comes before that specific statement. Hence, it presents the context that is the place, situation or even atmosphere .

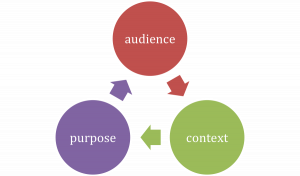

Rhetorical Context: Purpose, Author, and Audience

Although the context in literature is something different, it is different in rhetoric , too. In literary writings, it is just the situation where some statement or characters or events take place. However, in rhetoric, it is not just the text, it is also the purpose of the writing, its author and its audience that matter the most. They make up the context of that rhetorical piece. The reason is that rhetoric is specifically intended to be used for a specific purpose and by a specific person, or it loses its real purpose as well as its effectiveness.

Use of Context in Sentences

- This story was written in the 19 th century after the end of the Civil War. (The context mentions – when)

- Gandhi studied law in South Africa before returning to India and starting the Freedom Movement. (The context mentions – where)

- Harry Potter was published in 1997 by Bloomsbury, United Kingdom. (The context mentions when and where)

- Ivan heard ‘Bonjour’ as soon as he landed at the airport and saw the tower’s top on the way to the exit. (The context mentions a setting and the character is abroad)

- The English Tommies with their weapons entered the buildings to secure the area. (The context mentions the time period of WW1, when soldiers were called ‘Tommies’)

Examples of Context in Literature

Example #1: a tale of two cities by charles dickens.

Dickens begins his novel , A Tale of Two Cities , in 1770, by describing the release of Doctor Manette from Bastille, before taking the story to 1793 and early 1794. In this time span, the narrative covers a broad story. In a larger view, this novel begins in 1757, while its final scene looks forward to the situation in post-revolutionary Paris.

This story has a historical context, which Dickens has organized around various events that occurred during the French Revolution. He has drawn historical features from major events, including the fall of Bastille, the September Massacres, and the Reign of Terror. This backdrop is the story’s context.

Example #2: Animal Farm by George Orwell

George Orwell felt disillusioned by Soviet Communism and its revolution during his time. In the phenomenal novel, Animal Farm , Orwell has expressed himself by using satire through the allegorical characters of Old Major and Boxer; relating them to the Russian Revolution and its characters. Orwell uses animals to explain the history and context of Soviet Communism, some of which relate to party leaders. For instance, the pig Napoleon represents Joseph Stalin, and Snowball represents Leon Trotsky. In fact, Orwell uses this fable for political and aesthetic reasons, following the Russian Revolution as its context.

Example #3: Dr. Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Historical context of Christopher Marlowe ’s Dr. Faustus is religious, as it hints at cultural changes taking place during Marlowe’s time. In 16th century Europe, there was a conflict between Roman Catholicism and the Protestant English Church. During this entire period, Calvinism was popular within the English churches; however, it was controversial. According to Calvinistic doctrine, the status of the people was predestined as saved or damned. Scholars and readers have debated on the stance that Marlowe’s play takes regarding the Calvinist doctrine, in whether Faustus is predestined to hell or not. The Renaissance period provides context for this play by Marlowe.

Example #4: Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

There is a popular saying that stories indicate the values and cultures of the societies in which their authors live. In Oedipus Rex , Sophocles presents his protagonist , Oedipus, struggling to implement his will against the destiny set forth by the Greek gods. During this process, Sophocles reveals the Greek values of the period during which he wrote the play.

He has illustrated the context of this play through the words and actions of Oedipus and other characters; as their Greek ideals concerning their governance, fate, and human relationships with the gods. These were some of the more popular themes of that era, and so form the context of the Oedipus Rex .

Example #5: Lord of the Flies by William Golding

“While stranded on a deserted island, a group of boys believe there is a dangerous creature lurking in the underbrush; Simon is the first to identify this menace, suggesting to the boys that ‘maybe,’ he said hesitantly, ‘maybe there is a beast’.”

This excerpt provides an excellent example of context, as it narrates an incident involving a group of young men on a deserted island. The context describes why they were afraid, giving a clear picture of the situation and setting.

Context is all about providing a background or picture of the situation, and of who is involved. Context is an essential part of a literary text, which helps to engage the audience. If writers ignore context, they may overlook a critical aspect of the story’s intent. Without context, readers may not see the true picture of a literary work. Context helps readers understand the cultural, social, philosophical, and political ideas and movements prevalent in society at the time of the writing.

Synonyms of Context

Context does not have an equivalent, it has several synonyms that could replace it in different contexts. For example, conditions, factors, surroundings, state of affairs, environment, situation, background, milieu, mood , ambiance, subject , text, theme , or topic.

Post navigation

What Is Context? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Context definition.

Context (KAHN-tekst) is the circumstances that inform an event, an idea, or a statement. It is the detail that adds meaning to a text. Readers can study internal context—details included by the author, such as backstory, characterization , or setting —as well as external context—the time period of the work’s publication, the author’s literary influences, and even their personal history.

Imagine context as a bridge between the writer and the reader that clarifies a text’s meaning and purpose. Authors provide these details to ensure a story is richly developed and true to life, and readers consider external context to understand a story’s broader significance.

Types of Context

There are several types of literary context, but the following are the most common applications.

Authorial Context

A writer’s experiences inevitably inform their writing, from content to style. This biographical context can refer to an author’s life history, a text’s place in an author’s body of work, the author’s success, the circumstances in which a text was written, current events at the time of publication, and even an author’s motivation for writing a text.

Historical Context

Literature is often influenced by history. Historical novels are directly grounded in past events and circumstances, but historical context also encompasses how literature reflects or responds to the society in which it was written. This can manifest as intentional criticism, in which an author addresses a social issue and perhaps argues for change (e.g., Jonathan Swift’s “ A Modest Proposal ,” his satirical indictment of the aristocracy). However, literature can also unconsciously reflect attitudes or beliefs predominant at the time of composition. Gone with the Wind is a beloved classic, but modern audiences often criticize its sanitized portrayal of slavery.

Philosophical Context

Literature addresses age-old questions of metaphysics, ethics, and morality. It ponders the purpose of life, the nature of God or the universe, right versus wrong, death, time—the list goes on. Philosophies go in and out of style, and the great literary movements were influenced by philosophies that waxed and waned over time. Romanticism was followed by realism , which was followed by transcendentalism and then naturalism , modernism, postmodernism, and so on. Each of these movements was influenced by contemporaneous philosophical thought, and readers can learn much about a text by researching those concepts, the associated philosophers, and the author’s stance on the issue.

Literary Context

Allusion is a common demonstration of literary context, in which one text indirectly references another. But literary context can include several different things, such as an author’s role models or the way one text influences another. Literary context also considers how a text fits into broad categories of literature, such as the aforementioned literary movements.

How Writers Use Context

Writers use context to engage, inform, and entertain readers. These details establish the narrative ’s setting and the author’s motivation for writing, and they help propel the action. Context adds authenticity, helping a story reflect readers’ experiences and securing their investment in the text. Like most literary tools, moderation is essential when it comes to context. Too much of it can burden a story, rendering it boring or incomprehensible.

Context can be conveyed through just about anything— characterization , setting, backstory, memory, dialogue, and so on. If a detail informs readers’ understanding of the text, engages their intellect or emotions, or hooks their interest, then it can be used as context. However, specificity is key. By choosing what context to include, and when and how to do so, writers can guide readers’ interpretation of a text. They can also incorporate specific details to better anchor a story in a particular time or place. Consider the HBO miniseries Chernobyl . It is ostensibly about the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Pripyat, Russia, but the show’s true focus is government lies and corruption. The show uses the context of Soviet Russia to elicit nostalgia and cultural memory, emphasizing how modern politics echo that of the Cold War era.

Context can also inspire. A writer might reflect upon their life and realize they have a unique point of view worth sharing. They can use the context of their lives to communicate that perspective to the world. When a writer does this well, they spark understanding within readers, helping them make new connections and realizations.

Context and Literary Analysis

Publication opens a work up to criticism, including literary analysis, which dissects and evaluates literature to make connections that general audiences may have missed. Literary analysis hinges on context. Scholars and critics engage in close reading to discover deeper meaning, identify narrative patterns or themes, and detect influences, then analyze and synthesize their findings. They bring these disparate details together like puzzle pieces to explain why and how a text is significant and how it fits into culture and literature in general.

Writers’ Vernacular and Context Clues

When a reader encounters an unfamiliar word, they study the surrounding text to discern its meaning. This process of gleaning connotation is called using context clues. These are details that directly or indirectly suggest information about a word, phrase, or situation.

There are several types of context clues, the following five being the most common.

- Definition and explanation : There’s nothing subtle about these context clues, as the author clarifies the word’s intended meaning directly in the text.

- Inferences : When a word or idea is not explained within the same sentence, readers must decipher the writer’s implied or indirect meaning from the surrounding text.

- Synonyms and comparison : Synonyms draw comparisons that clarify, refine, or emphasize a writer’s meaning.

- Antonyms and contrast : Antonyms convey an opposite meaning to underscore contrast or disparity.

- Punctuation : Writers can use punctuation to several effects, such as conveying emotion (e.g., using exclamation points to express anger) or implying meaning (e.g., using parenthetical asides to suggest confidentiality).

Examples of Context in Literature

1. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Set in a dystopian near-future, The Handmaid’s Tale follows Offred and other subjugated women who strive to reclaim their independence after a theonomic totalitarian state called Gilead usurps the US government. This quote comes from Chapter 6, as Offred and fellow handmaiden Ofglen observe the corpses of people murdered by the state:

Ordinary, said Aunt Lydia, is what you are used to. This may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time it will. It will become ordinary.

Gripped by horror, Offred recalls these words, which suggest that “ordinary” is a matter of perspective and that, in time, Gilead’s atrocities will seem normal. Aunt Lydia’s assurance that murder, oppression, and subjugation can become commonplace, even routine, reveals the depth of Gilead’s power and depravity.

2. Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

This novel, set before and during the French Revolution, tells the story of Doctor Alexandre Menette, who is imprisoned in the Bastille for 18 years then moves to London to reunite with his daughter Lucie. Dickens contextualizes the setting in the very first paragraph:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

This passage immediately establishes that the novel’s main conflicts revolve around binary extremes, such as good and evil or wisdom and folly. This signals that the story is rife with contradiction and controversy, and that the setting is full of tension but also hope.

3. Tim O’Brien, “ The Things They Carried ”

This is the eponymous short story in a collection of tales about the Vietnam War. The story reflects on the things soldiers carry with them into war:

To carry something was to hump it, as when Lieutenant Jimmy Cross humped his love for Martha up the hills and through the swamps. In its intransitive form, to hump meant to walk, or to march, but it implied burdens far beyond the intransitive.

The opening phrase is a context clue that directly explains the author’s meaning. The passage further explains that although hump has alternative meanings, such as “to walk” or “to march,” in this context it means something more abstract, something heavy and grim.

Further Resources on Context

This Writing Cooperative article explains how context builds trust between the writer and their audience, and why that relationship is so important.

ThoughtCo provides a more thorough look at context clues —and their limitations.

This resource from Harper College explains the textual elements (including context) used to analyze literature.

Related Terms

- Characterization

- Point of View

The Context In an Essay

Low Cost, Fast Delivery, and Top-Quality Content: Buy Essay Now and Achieve Academic Excellence for Less!

- What Is The Context In an Essay

- Historical Context

- Cultural Context

- Geographical Context

- Social Context

- Biological Context

- Political Context

- Literary Context

- Scientific Context

- Technical Context

- Legal Context

- Ethical Context

- Economic Context

- Psychological Context

- When And How to Use The Context In an Essay

One of the main principles of academic writing is to use context. Using context may help you to avoid plagiarism, show the diversity of your knowledge, and make your text more interesting for readers. What is the context? Context can be defined as “background information.” It should be used in every piece of written work, primarily in academic essays (including research papers, term papers, etc.). Read on to discover what you can and cannot do with the context, how to use it properly, and how to find it.

Article structure

What is the context in an essay

If your topic is more specific, you can use even more context. However, remember that you should avoid using too many context options at once – the more options you have, the harder it will be to analyze and select the most appropriate one.

Here are some examples of common contexts that you can use in a research paper.

Historical context

The context of a research paper should be a specific event that took place in the past. It is very important that you provide an accurate description of the historical context, so your paper will be more interesting for your readers. For example, the research paper about the Holocaust can be written in the context of World War II, so you must describe in detail the events that took place. Your historical research paper should provide all necessary data, facts, and numbers about the history of the event, so you can write the essay with a clear understanding of all details.

The most important factor of the historical context is the correct chronological order. The best historical research papers are usually written in chronological order. In fact, the whole structure of the research paper is defined by the order of the events. The most interesting and useful information is at the beginning. In this case, the historical context is very important, because it gives an opportunity to understand the main topic of the essay.

The next step is to analyze the historical data in the essay. You have to make the right conclusion about your research, so you can write the essay in the right chronological order.

Cultural context

This context is usually used in writing about art, literature, music, etc. To create an interesting essay, you should include information about the culture in which you grew up, such as your country, region, family, and so on. This information can be written in different ways. Sometimes, information about culture should be provided to the reader from the start. At other times, you should use it as background information for your own comments and explanations. You may use cultural elements of your own experience to illustrate the concept of the subject at hand.

The idea of cultural context is very similar to the idea of historical context. However, cultural context usually refers to the context of the current period of your life, whereas historical context refers to the period when you grew up. Therefore, you are more likely to use information about your own cultural context, but you may also want to use information about the historical context of the topic. For example, if you are studying World War I, you would probably want to include some information about the culture of the time, but you would also want to focus on the events and conditions that led to the war. In other words, your cultural context must be specific and relevant to the topic of your paper.

If you need to write an essay about a period of time when you were not born, you should make use of your current cultural context to write about the events of the time.

Geographical context

This context is usually used in writing about geography, sociology, economics, politics, and many other disciplines. To make your paper more interesting, you need to include geographical, political, and economical information about your country, state, city, and town. You can also include demographic information about the area that is of your study.

You should include this geographical context whenever it is applicable. In some cases, it could even influence the flow of your paper. It could be either positive or negative. For instance, if you are writing about a country that is a large producer of oil, it may be difficult for you to gain sympathy from the people who are not aware of the country’s environmental damage.

In some cases, the geographical context could affect the flow of your paper. If your study is about an industrial city, then you should include information about the city’s industry. If you are going to study a small town, then you should include a small business report or small business owners’ report.

Social context

This context is used in social sciences, psychology, law, political science, economics, etc. You need to include information about your family, the friends you have, the social situation of your city, and so on. You also need to be aware of the social context of your topic. This is the main purpose of this chapter. It may be the context of your work or the context of your study. For instance, in this chapter, we may be talking about the context of studying and working in London or New York.

When you are studying or working in a new country, try to see if you can find out about its culture or society. Try to talk to the natives to find out about how they live and work. See if you can find some interesting books, or magazines, or TV programs about your new country.

Biological context

Biological context is used in many disciplines such as biology, chemistry, nutrition, etc. You need to include all the details about your parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, hobbies, and so on. If you are describing the biological system or a biochemistry procedure, then you need to include a detailed description of the system itself. You need to include a description of all the compounds involved. If you are a cell biologist, you will need to explain all the biochemical steps involved in a cell cycle or DNA replication.

The basic biological context includes the history of the discovery and the biological and medical context of a particular problem that needs to be solved.

Political context

The political context is the most complex of all. You need to include information about the current political situation in your country, the situation of the region where you live, your political preferences, and so on.

When writing a research paper in political science, you need to be well-informed about the political situation in your country at the moment of writing. It is very difficult to write about politics, but if you are not well-informed, the research paper will sound biased and unauthentic.

The political situation is very important, as it is a determinant of the development of the country. A country with a democratic government can be easily influenced by external factors, whereas in a country with a communist or authoritarian government, external factors cannot influence such a country. When writing an essay about politics in general, it is important to mention the main political factors, the most important ones.

Literary context

In a research paper, the literary context should be the most important because of the following reasons:

- The more the authors in your paper are famous, the more your paper will become interesting to your readers;

- A good literature essay needs the authors’ names;

- The more a research paper is about famous people, the more accurate information you can provide about them.

In this case, the best literary sources to be used are biographies and autobiographies. Biographies and autobiographies provide more information about famous people because it is not the same to write about someone from his life as it is to write about someone’s life.

In writing about someone’s life, you have to write about all the things that make someone special and interesting. In order to write about someone’s life, you need to write about the events that have occurred to this person, the thoughts and emotions he has felt during his lifetime, and also the actions that he has done.

Scientific context

The scientific context is used in scientific papers. Here you should give information about your laboratory, university, the research institute, your research interests, and so on. You need to be aware of the scientific context of your research topic. You can get inspiration from other people’s research, look for papers that use the same scientific context as you, and have similar research interests. Also, find out which journal your paper will be published. Finally, check whether a scientific context is necessary for your paper.

Technical context

The technical context is used in many disciplines. If your essay is more technical, the information you need to include in your paper will be different. The technical context will be a list of things that you use to describe the context in which your writing takes place.

What are the major aspects of the technical context?

The technical context is used to describe the nature of a problem or the nature of the subject in which a particular paper has been written. For instance, a report on a product will have a specific technical context, so it is important to know what your report is about. This knowledge will help you to choose the most suitable technical language and style of writing.

Legal context

The legal context is used in many disciplines. If your essay is more legal, the information you should include in your paper will be different. There are various elements to the legal context of an argument, such as the nature of the case, and the relevant law, in order to analyze your paper. Some questions to think about when analyzing the legal context are:

- What are the rules that are used in the law to analyze the case?

- How can those rules help you to determine whether or not the case is a good one for you to use?

- What are the reasons behind the rules?

- How will you use those reasons to determine whether or not the case will be a good fit for your argument?

Ethical context

The ethical context is used in many disciplines. If your essay is more ethical, the information you should include in your paper will be different.

Ethical context is used to address the moral nature of a certain action or issue. The paper will discuss the ethical context in terms of the values that are attached to the subject. Ethical context should be included in the paper so that the values and beliefs of the readers are considered. The ethical context will make the paper more complete and also will prevent plagiarism.

Economic context

The economic context is usually used in economics. If your essay is more economic, the information you should include in your paper will be different. A paper that is entirely economic would typically have:

- a short introduction

- a discussion of the main economic concepts that will be used in your essay

- an overview of the different economic problems that will be discussed

- an analysis of the economic problems

- an examination of the arguments used in the analysis of the economic problem

- an evaluation of the arguments used in the discussion of the economic problem

Psychological context

The psychological context is usually used in psychology. If your essay is more psychological, the information you should include in your paper will be different. In this case, you need to understand a little more about psychology and the people that you are writing about.

It is very important to understand what kind of psychological context the essay you are writing about is in. This is very important as the writer has to consider what the essay is about. The context of the psychological essay you are writing about will help you decide whether to write about positive or negative issues. If the essay is positive, then you will need to think about the people in a positive context. If the essay is negative, then you will need to think about the people in the negative context.

When and how to use the context in an essay

Now you know what the context is and how it should be used in your research paper. However, how do you use context when writing? The answer to this question is a separate issue.

You should use the context in your essay in many situations. One of them is to provide extra information that you might need during the writing process. This is very useful when you need to write an outline, write a thesis statement, find examples, or describe a certain event.

If you use the right context, you will have no problem writing a strong essay. Moreover, you will avoid plagiarism and your text will be more interesting for readers.

Here are some situations in which the context can be useful in your research paper:

1. Research paper topics

The research paper topics may be very broad or very specific. It is not always possible to write a research paper about a narrow topic. The context may be useful in such situations to explain the topic. You should include more information about it in your essay.

If you have a very broad topic, you will need to give more information about it to make your essay more interesting. However, be careful that you do not include too many options. This could lead to plagiarism.

If you have a very specific topic, you will need to provide more information about it to make your essay more interesting for readers. The main idea of a research paper should be clear to them from the beginning, so you should provide the most relevant information.

2. Outlining

Writing an outline is not always easy for everybody. Sometimes you are not able to choose the most appropriate order of the main ideas in your research paper. In such a situation, the context can be useful to explain the order of ideas.

It is very easy to make a mistake in writing an outline. However, the context can help you to remember the main topics in your research paper.

3. Writing a thesis

You need to know how to write a thesis statement. However, it is also very important to know how to choose the most suitable thesis statement for a particular essay. If you find yourself in such a situation, the context can be useful to explain the main topic.

When you choose the right thesis statement for a particular essay, you will avoid plagiarism and make your essay more interesting for readers.

4. Writing an introduction

The introduction is one of the most important parts of a research paper. If you need to write an interesting introduction, you should include the right context in your essay. The context may include information about the problem, the thesis statement, the main idea, examples, and so on.

If you need to make the best out of the context, you should use the following structure of an introduction:

- What the problem is.

- What is the main idea is.

This structure is very useful because it gives your readers brief information about your topic. You can also provide links to further information. The main idea is explained in a clear and understandable way. You can use several examples to illustrate your point.

5. Writing a conclusion

The conclusion of the research paper is also very important. If you need to write a strong conclusion, you should provide more information about your topic. You should give more information about it in your conclusion.

The context can be used in several ways in your conclusion. You can use information about the problem, the main idea, examples, and so on. If you need to make the best of the context, the structure of a conclusion should be as follows:

- Explain what the conclusion is.

- Explain what the main idea is.

You can use examples to show what the conclusion means. It is very important to include these examples because they help to make your text more interesting for readers.

6. Writing an essay

In this case, the context is not used in your writing. However, it is very important to know about the structure of a research paper. The main idea of a research paper should be clear to your readers from the beginning. However, you should know how to make the best of the context. You should not make any unnecessary claims that may lead your reader to reject the whole paper.

In short, a context is an important tool in any research paper. A good thesis statement must have context. It will not be clear to your readers if you are talking about a subject in the abstract or you have used the context to support your thesis statement.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Audience, Purpose, & Context

Questions to Ponder

Discuss these following scenario with your partners:

Imagine you are a computer scientist, and you have written an important paper about cybersecurity. You have been invited to speak at a conference to explain your ideas. As you prepare your slides and notes for your speech, you are thinking about these questions:

- What kind of language should I use?

- What information should I include on my slides?

Now, imagine you are the same computer scientist, and you have a nephew in 3rd grade. Your nephew’s teacher has invited you to come to his class for Parents’ Day, to explain what you do at work. Will you give the same speech to the class of eight-year-olds? How will your language and information be the same or different?

Thinking about audience, purpose, and context

Before we give the presentations in the scenarios described above, we need to consider our audience, purpose, and context. We need to adjust the formality and complexity of our language, depending on what our audience already knows. In the context of a professional conference, we can assume that our audience knows the technical language of our subject. In a third grade classroom, on the other hand, we would use less complex language. For the professional conference, we could include complicated information on our slides, but that probably wouldn’t be effective for children. Our purpose will also affect how we make our presentation; we want to inform our listeners about cybersecurity, but we may need to entertain an audience of third graders a bit more than our professional colleagues.

The same thing is true with writing. For example, when we are writing for an academic audience of classmates and instructors, we use more formal, complex language than when we are writing for an audience of children. In all cases, we need to consider what our audience already knows, what they might think about our topic, and how they will respond to our ideas.

In writing, we also need to think about appearance, just as we do when giving a presentation. The way our essay looks is an important part of establishing our credibility as authors, in the same way that our appearance matters in a professional setting. Careful use of MLA format and careful proofreading help our essays to appear professional; consult MLA Formatting Guides for advice.

Before you start to write, you need to know:

Who is the intended audience ? ( Who are you writing this for?)

What is the purpose ? ( Why are you writing this?)

What is the context ? ( What is the situation, when is the time period, and where are your readers?)

We will examine each of these below.

AUDIENCE ~ Who are you writing for?

Your audience are the people who will read your writing, or listen to your presentation. In the examples above, the first audience were your professional colleagues; the second audience were your daughter and her classmates. Naturally, your presentation will not be the same to these two audiences.

Here are some questions you might think about as you’re deciding what to write about and how to shape your message:

- What do I know about my audience? (What are their ages, interests, and biases? Do they have an opinion already? Are they interested in the topic? Why or why not?)

- What do they know about my topic? (And, what does this audience not know about the topic? What do they need to know?)

- What details might affect the way this audience thinks about my topic? (How will facts, statistics, personal stories, examples, definitions, or other types of evidence affect this audience?)

In academic writing, your readers will usually be your classmates and instructors. Sometimes, your instructor may ask you to write for a specific audience. This should be clear from the assignment prompt; if you are not sure, ask your instructor who the intended audience is.

PURPOSE – Why are you writing?

Your primary purpose for academic writing may be to inform, to persuade, or to entertain your audience. In the examples above, your primary purpose was to inform your listeners about cybersecurity.

Audience and purpose work together, as in these examples:

- I need to write a letter to my landlord explaining why my rent is late so she won’t be upset. (Audience = landlord; Purpose = explaining my situation and keeping my landlord happy)

- I want to write a proposal for my work team to persuade them to change our schedule. (Audience = work team; Purpose = persuading them to get the schedule changed)

- I have to write a research paper for my environmental science instructor comparing solar to wind power. (Audience = instructor; Purpose = informing by analyzing and showing that you understand these two power sources)

Here are some of the main kinds of informative and persuasive writing you will do in college:

How Do I Know What My Purpose Is?

Sometimes your instructor will give you a purpose, like in the example above about the environmental science research paper ( to inform ), but other times, in college and in life, your purpose will depend on what effect you want your writing to have on your audience. What is the goal of your writing? What do you hope for your audience to think, feel, or do after reading it? Here are a few possibilities:

- Persuade or inspire them to act or to think about an issue from your point of view.

- Challenge them or make them question their thinking or behavior.

- Argue for or against something they believe or do; change their minds or behavior.

- Inform or teach them about a topic they don’t know much about.

- Connect with them emotionally; help them feel understood.

There are many different types of writing in college: essays, lab reports, case studies, business proposals, and so on. Your audience and purpose may be different for each type of writing, and each discipline, or kind of class. This brings us to context.

CONTEXT ~ What is the situation?

When and where are you and your readers situated? What are your readers’ circumstances? What is happening around them? Answering these questions will help you figure out the context, which helps you decide what kind of writing fits the situation best. The context is the situation, setting, or environment; it is the place and time that you are writing for. In our examples above, the first context is a professional conference; the second context is a third-grade classroom. The kind of presentation you write would be very different for these different contexts.

Here’s another example: Imagine that your car breaks down on the way to class. You need to send a message to someone to help you.

AUDIENCE : your friends

PURPOSE : to ask for help

CONTEXT : you are standing by the side of Little Patuxent Parkway, 10 minutes before class begins. Your friends are already at the campus Starbucks or in Duncan Hall.

Do you and your readers have time for you to write a 1,000-word essay about how a car works, and how yours has broken down? Or would one word (‘help!’) and a photo be a better way to send your message?

Now imagine that you are enrolled in a mechanical engineering class, and your professor has asked for a 4-page explanation of how internal combustion works in your car. What kind of writing should you produce? This would be the appropriate audience, purpose, and context for the 1,000-word essay about how a car works.

Activity ~ A Note about Tone

As you consider your audience, purpose, and context, you will need to think about your word choice as well. For example, say these two phrases out loud:

- very sick kids

- seriously ill children

Do they mean the same thing? Would you use the phrases in the same way? How about:

- lots of stuff

The words we choose help determine the tone of our writing, which is connected to audience, purpose, and context. Can you think of other examples using formal and informal tone?

Is this chapter:

…about right, but you would like more detail? –> Watch “ Audience: Introduction & Overview ” and from Purdue’s Online Writing Lab. Also, view “ Purpose, Audience, & Context ” from The Ohio State University.

…about right, but you prefer to listen and learn? –> Try “ Thinking About Your Assignment ” from the Excelsior OWL and “ A Smart Move: Responding the Rhetorical Situation .”

…too easy? –> Watch “ Writing for Audiences in U.S. Academic Settings ” from Purdue OWL.

Or, how about watching a funny video? In this short (3.5 minutes) video from the popular children’s program Sesame Street , Sir Ian McKellen tries to teach Cookie Monster a new word, but at first, Sir Ian doesn’t really understand what his audience knows (or doesn’t know), so Cookie Monster doesn’t understand.

Portions of this chapter were modified from the following Open Educational Resources:

Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

“ Audience ” and “ Purpose ” chapters from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Note: links open in new tabs.

to think about

believability

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

16.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically About Text

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a writing project focused on textual analysis.

- Complete the stages of the writing process, including generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Integrate the writer’s ideas with ideas of others.

- Collaborate in the peer review process.

When analyzing a text, writers usually focus on the content of the text itself and deliberately leave themselves in the background, minimizing personal presence and bias. To write this way, they avoid first-person pronouns and value judgments. In reality, of course, writers do reveal their presence by the choices they make: what they include, what they exclude, and what they emphasize. Although your own subjectivity and situation will likely affect your inferences and judgments, recognizing these potential biases will help you keep the focus on your subject and off yourself.

Summary of Assignment

Write an analytical essay about a short story or another short text of your choice, either fiction or literary nonfiction. If desired, you may choose “The Storm” by Kate Chopin, reprinted above. Consider the author’s form and organization, tone, or stylistic choices, including diction and sensory or figurative language. You might also consider the historical or social context, the theme, the character development, or the relation between setting and plot or characterization. If you are free to choose your own text and topic, consider the following approaches:

- Analyze the literary components mentioned and focus your essay on their significance in the work.

- Like student author Gwyn Garrison, choose one or several components and examine how different authors use them and how they relate to broader contexts.

Convincing textual analysis essays usually include the following information:

- overview of the text, identifying author, title, and genre

- very brief summary

- description of the text’s form and structure

- explanation of the author’s point of view

- summary of the social, historical, or cultural context in which the work was written

- assertion or thesis about what the text means: your main task as an analyst

When writing about a novel or short story, explain how the main elements function:

- narrator (who tells the story)

- plot (what happens in the story)

- one or more characters (who are acting or being acted upon)

- setting (when and where things are happening)

- theme (the meaning of the story)

Keep in mind that the author who writes the story is different from the narrator and invented characters in it. Keep in mind, too, that what happens in the story—the plot—is different from the meaning of the story—the theme. Understanding what happens will help you discover what the text means.

The elements of literary or narrative nonfiction are similar to those of a fictional story except that everything in the text is supposed to have really happened. For this reason, the author and the narrator of the story may be one and the same. Informational nonfiction—essays, reports, and textbook chapters—is also meant to be believed; here, however, ideas and arguments must be strong and well supported to be convincing. When analyzing nonfiction, pay special attention to the author’s thesis or claim and to how it is supported through reasoning and evidence. Also note interesting or unusual tone, style, form, or voice.

Another Lens 1. In writing from a personal or subjective viewpoint, the writer and their beliefs and experiences are necessarily part of your analysis and may need to be expressed and examined. For example, you may write subjectively and compare and contrast your situation with that of the author or a character. You might explain how your personal background causes you to read the text in a particular way that is meaningful to you. If you choose this option, be sure to analyze the text as you would for a more objective analysis before focusing on your personal views.

Another Lens 2. A leading contemporary example of narrative nonfiction writing is Jon Krakauer ’s (b. 1954) Into the Wild , the story of Chris McCandless (1968– c. 1992), a young college graduate who lived at subsistence level in the backwoods of Alaska for 113 days. The text is somewhat similar thematically to Henry David Thoreau ’s (1817–1862) Walden (1854), written more than a century earlier and discussed later in this section. Both are about dropping out of society to create a meaningful life. After reading the excerpt of Into the Wild linked above, you may choose to write a textual analysis of it either on its own or in light of the sample analysis of Thoreau’s writings later in this section. Consider comparing and contrasting McCandless’s situation with Thoreau’s life in Walden and how Krakauer and Thoreau use various literary elements in their writing. Topics for analysis might be setting, character traits, motives, cultural communities, historical context, and attitudes toward life and society.

Quick Launch: Start with Your Thesis

For textual analysis, your thesis should be a clear, concise statement that identifies your analytical stance on which readers will expect you to elaborate.

Develop a working thesis

A working thesis is referred to as such because the thesis is subject to revision. You may have to revisit it later in the writing process, for it is almost impossible to craft a thesis without having analyzed some of the text first. Your thesis, therefore, will come from the element(s) you choose to analyze, such as the following:

- an aspect or several aspects of form and structure and their significance

- social, historical, or cultural context in which the text was written and its significance

- style elements such as diction, imagery, or figurative language and their significance

- aspects of characters, plot, or setting

- overall theme of a single work or more than one work

- comparison or contrast of elements within one or more works

- relation to issues outside the text

To develop a working thesis, use the formula shown in Table 16.1 , basing your answers on one of the bulleted items listed above.

You can also start with an analytical question: For what reason(s) does Chopin use linguistic variety? Your initial answer might yield the thesis above. Or you can ask another analytical question, such as this one: In what ways do the plot and setting of “The Storm” reinforce its theme?

Drafting: Explore Possible Areas of Analysis for Fiction: Approach 1

Analytical essays begin by answering basic questions: What genre is this text—poem, play, story, biography, memoir, essay? What is its title? Who is the author? When was it published?

Identify and Summarize the Text

In addition to the basic questions, analytical essays provide a brief summary of the plot or main idea. Summarize briefly, logically, and objectively to provide a background for what you plan to say about the text. This information may be incorporated into the introduction or may follow it.

Explain the Form and Organization

To analyze the organizational structure of a text, ask: How is it put together? Why does the author start here and end there? Why does the author sequence information in this order? What connects the text from start to finish? For example, by repeating words, ideas, and images, writers call attention to these elements and indicate that they are important to the meaning of the text. No matter what the text, some principle or plan holds it together and gives it structure. Fiction and nonfiction texts that tell stories are often, but not always, organized as a sequence of events in chronological order. Poems may have formal structures or other organizational elements. Other texts may alternate between explanations and examples or between first-person and third-person narrative. You will have to decide which aspects of the text’s form and organization are most important for your analysis.

For example, this student analyzes the point of view of Gwendolyn Brooks ’s poem “ We Real Cool .”.

student sample text Gwendolyn Brooks writes “We Real Cool” (1963) from the point of view of members of a street gang who speak as one voice. The boys have dropped out of school to spend their lives hanging around pool halls—in this case “The Golden Shovel.” These guys speak in slangy lingo, such as “Strike straight,” that reveals their need for a melded identity in their rebellious attitude toward life. The plural speaker in the poem, “We,” celebrates what adults might call adolescent hedonism—but the speaker, feeling powerful in the group identity, makes a conscious choice for a short, intense life over a long, safe, and dull existence. end student sample text

Place the Work in Context

To analyze the context of a text, ask: What circumstances (historical, social, political, biographical) produced this text? How does this text compare or contrast with another by the same author or with a similar work by a different author? No text exists in isolation. Each was created by a particular author in a particular place at a particular time. Describing this context provides readers with important background information and indicates which conditions you think were most influential.

For example, this student analyzes the social context of Gwendolyn Brooks ’s poem “We Real Cool.”

student sample text From society’s viewpoint, the boys are nothing but misfits—refusing to work, leading violent lives, breaking laws, and confronting police. However, these boys live in a society that is dangerous for Black men, who often die at the hands of police even when they are doing the right thing. The boys are hopeless, recognizing no future but death, regardless of their actions, and thus “Die soon.” end student sample text

Explain the Theme of the Text

To analyze the theme of a text, determine the implied theme in fiction, poetry, and narrative nonfiction. One purpose for writing a textual analysis is to point out the theme. Ask yourself: So what? What is this text really about? What do I think the author is trying to say by writing this text? What problems, puzzles, or ideas are most interesting? In what ways do the characters change between the beginning and end of the text? Good ideas for a thesis arise from material in which the meaning is not obviously stated.

For example, this student analyzes one theme of Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool.”

student sample text For the “Seven at the Golden Shovel,” companionship is everything. For many teenagers, fitting in or conforming to a group identity is more important than developing an individual identity. Brooks expresses this theme through the poem’s point of view, the plural “We” repeated at the end of each line. end student sample text

Analyze Stylistic Choices

To analyze stylistic choices, examine the details of the text. Ask yourself: Why does the author use this word or phrase instead of a synonym for it? In what ways does this word or phrase relate to other words or phrases? In what ways do the author’s figurative comparisons affect the meaning or tone of the text? In what ways does use of sensory language (imagery) affect the meaning or tone of the text? In what ways does this element represent more than itself? In what ways does the author use sound or rhythm to support meaning?

For example, this student analyzes the diction of Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool.”

student sample text Brooks chooses the word cool to open the poem and build the first rhyme. Being cool is the code by which the boys live. However, the word cool also suggests the idiom “to be placed ‘on ice,’” a term that suggests a delay. The boys live in a state of arrested development, anticipating early deaths. In addition, the term to ice someone means “to kill,” another reference to the death imagery at poem’s end. The boys are not suggesting suicide; they expect to be killed by members of society who find them threatening. end student sample text

Support Your Analysis

Analytical interpretations are built around evidence from the text itself. You’ll note the quotations in the examples above. Summarize larger ideas in your own language to conserve space. Paraphrase more specific ideas, also in your own words, and quote directly to feature the author’s diction. See Editing Focus: Paragraphs and Transitions and Writing Process: Integrating Research for more information about summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting directly. If you include outside information for support, comparison, or contrast, document the sources carefully: MLA Documentation and Format .

Use a graphic organizer such as Table 16.2 to gather ideas for drafting.

Drafting: Explore Possible Areas of Analysis for Literary Nonfiction: Approach 2

Although similar to fiction, narrative or literary nonfiction has a basic orientation toward exposition: relating real events in a creative way rather than inventing fictional events and characters. In reading and analyzing expository prose, you also may encounter literary language, narrative structure, characters, setting, theme, and plot development, depending on the type of prose. Therefore, your approach to analyzing nonfiction will call on many of the same strategies you use to analyze fiction. Two basic differences, however, are that literary nonfiction may have less dialogue, depending on the genre, and that the author and narrator may be the same. In other words, no intermediary or artistic filter may exist between the author and the work. The nonfiction author is assumed to be speaking a truth, which may be serious, comic, controversial, or neutral. Fictional characters, on the other hand, are creations of an author’s mind; they think and speak as they were created to do.

Planning the Essay

In writing your essay, you will need to present the same kinds of text evidence as you would when analyzing fiction to give credibility to your claims and to support your thesis. And you’ll need to keep in mind the rhetorical situation—purpose, audience, stance, context, and culture—as well, for it remains the building block of an effective analysis. As in most academic essays, body paragraphs refer to the thesis through topic sentences and move consistently toward supporting it before you finally arrive at a convincing conclusion that has grown out of the analysis. In nonfiction, because you assume you are dealing with a truthful explanation of facts and views, your task should be to give a new view and understanding of something that already may be familiar to readers. In writing your analysis, consider the following plan:

- Begin your analysis of nonfiction with an introductory overview in which you include the work’s genre, title, author, and publication date.

- Identify the literary point of view, if relevant: first person— I or plural we —or third-person— he, she , or they .

- Continue with a brief summary of the work, and place it in context: the work’s social, historical, and cultural background will help readers follow your points about its theme.

- Present your thesis near the end of the introduction. It should be argumentative, in an academic sense, so that you can “prove” your points.

- Support your thesis with well-elaborated body paragraphs, as you do with all thesis-based writing. Include paraphrases, summaries, and quotations from the text (and outside sources, if you do research for the assignment). Body paragraphs support the topic sentences, which in turn support the thesis.

- Conclude by restating your thesis (using different words and an appropriate transition). Add a general statement about the work and its significance or, if applicable, its relation to culture, history, current events, art, or anything else outside it.

Use the applicable suggestions in Table 16.3 in planning your essay :

Literary Nonfiction Model

A frequent theme in literary nonfiction is the examination of alternative ways of living, often solitary and away from society, and finding truth in individualism and self-sufficiency. Although most people live in social groups and willingly accept the identity and security that communities offer, dropping out and going it alone have long been a part of emotional as well as physical life for some.

You have the option to analyze the nonfiction accounts of writers exploring solitary human behavior in American life. If you select Another Lens 2 , you will read an excerpt from the story of Chris McCandless (1968–c. 1992), who chose a brief and uncomfortable solitary existence in Alaska. Or you can read the following section dealing with the works of Henry David Thoreau , the American philosopher and author who dropped out of society temporarily, largely because of his strong opposition to government policies he believed to be morally wrong and because of his refusal to conform to social practices and expectations he found objectionable.

Introduction

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) is best known as a thinker and writer on nature, as reflected in his two famous works, the highly influential Civil Disobedience (1849) and Walden ; or, Life in the Woods (1854). Both works celebrate individual freedoms: the right to protest against what one believes is morally or ethically wrong and the choice to live as one believes. In describing his life over a period of precisely two years, two months, and two days in a 10-by-15-foot cabin he built on Walden Pond, 20 miles northwest of Boston near Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau wrote:

public domain text I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately [carefully, unhurried], to front [confront] only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life. end public domain text

Thoreau’s insistence on standing by his principles and on living a simple life by choice are two abiding themes in his work. Even before the physical move to Walden, Thoreau had refused to pay his poll tax (granting him the right to vote) for a number of years because he strongly objected to the government’s use of his money to support enslavement and the war with Mexico. He went peacefully to jail as a result, until he was bailed out (the next day). In “Civil Disobedience,” Thoreau advocates for more individual freedom and for individuals to defy unjust laws in nonviolent ways. His writings on “passive resistance” inspired the thoughts and actions of influential figures such as Indian leader Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948), American religious and civil rights leader Martin Luther King , Jr. (1929–1968), and other leaders of nonviolent liberation movements. In Walden , Thoreau describes and advocates for a simple life in which a person breaks with society when they feel the need to express their individualism, often based on ideas others do not share.

These themes are the focus of analysis in the following excerpts from an essay by student Alex Jones for a first-year composition class.

student sample text The Two Freedoms of Henry David Thoreau by Alex Jones end student sample text

student sample text Henry David Thoreau led millions of people throughout the world to think of individual freedom in new ways. During his lifetime he attempted to live free of unjust governmental restraints as well as conventional social expectations. In his 1849 political essay “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,” he makes his strongest case against governmental interference in the lives of citizens. In his 1854 book Walden; or Life in the Woods , he makes the case for actually living free, as he did in his own life, from social conventions and expectations. end student sample text

annotated text The title clearly identifies Thoreau and sets the expectation that two aspects or definitions of freedom will be discussed in two different works. Alex Jones wants readers to know that millions of people worldwide figure in Thoreau’s legacy. He gives the examples of “unjust governmental restraints” and “conventional social expectations” as the parts of social life Thoreau rejected, thus limiting the scope of the analysis and preparing for the body of the essay. end annotated text

annotated text Jones notes the titles and publication dates of both works and immediately moves ahead to analyze the two works, “Civil Disobedience” first. He will show how this political statement leads to the narrative of Walden , the actual story of a man’s life in temporary exile. end annotated text

student sample text Thoreau opens “Civil Disobedience” with his statement “that government is best which governs not at all.” end student sample text

annotated text The analysis moves immediately to the first work to be discussed and features the memorable quotation regarding a government that does not govern. The statement may seem contradictory, but for Thoreau it is a direct statement in that someone who allows himself to be imprisoned will find freedom by distancing himself from all others to prove his point. end annotated text

student sample text He argues that a government should allow its people to be as free as possible while providing for their needs without interfering in daily life. In other words, in daily life a person attends to the business of eating, sleeping, and earning a living and not dealing in any noticeable way with an entity called “a government.” end student sample text

annotated text Jones repeats “in daily life” to give a rhythm to his own prose and to emphasize the importance to Thoreau of daily activities that are simple and meaningful. The word government is repeated for emphasis as the negative subject of this essay—in literary terms, a powerful and constant antagonist that constrains and disempowers. end annotated text

student sample text Because Thoreau did not want his freedom overshadowed by government regulations, he tried to ignore them. However, the American government of 1845 would not let him. He was arrested and put in the Concord jail for failing to pay his poll tax, a tax he believed unjust because it supported the government’s war with Mexico as well as the immoral institution of slavery. Instead of protesting his arrest, he celebrated it and explained its meaning by writing “Civil Disobedience,” one of the most famous English-language essays ever written. In it, he argues persuasively, “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison” (230). Thus, the idea of passive resistance—and accepting unjust arrest to make a point—was formed, a doctrine that advocated protest against the government by nonviolent means: end student sample text

student sample text How does it become a man to behave toward this American government today? I answer that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also. (224) end student sample text

annotated text Jones strengthens his own writing by calling the essay one of the most famous works ever written. This is not an ordinary technique in textual analysis, but when done for emphasis, it helps the analysis gain power. Using “instead of protesting” at the start of his sentence is another example of strong contrast and linkage. end annotated text

student sample text For nearly 200 years, Thoreau’s formulation of passive resistance has been a part of the human struggle for freedom. In fact, it changed the world by inspiring the resistance movements led by Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. end student sample text

annotated text The total effect is to make Jones’s analytical essay more important for readers, as Thoreau’s writings have indeed changed the world despite being written humbly as the voice of one man’s conscience and isolation in his own freedom. end annotated text

student sample text Thoreau also wanted to be free from the everyday pressures to conform to society’s expectations. end student sample text

annotated text Jones transitions from the first short work to the different and equally famous nonfiction narrative Walden , moving smoothly from one freedom to the next with the transition “also wanted.” This second analysis of freedom is the second part of the essay’s thesis. end annotated text

student sample text He believed in doing and possessing only the essential things in life. To demonstrate his case, in 1845, he moved to the outskirts of Concord, Massachusetts, and lived by himself for just over two years in a cabin he built at Walden Pond. Thoreau wrote Walden to explain the value of living simply, far removed from the unnecessary complexity of society: “simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand” (66). At Walden, he lived as much as possible by this statement, building his own house and furniture, growing his own food, bartering for simple necessities, and attending to his own business rather than seeking employment from others. end student sample text