Achieving gender equality in India: what works, and what doesn’t

Research fellow, United Nations University

Disclosure statement

Smriti Sharma does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

United Nations University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Discrimination against women and girls is a pervasive and long-running phenomenon that characterises Indian society at every level.

India’s progress towards gender equality, measured by its position on rankings such as the Gender Development Index has been disappointing, despite fairly rapid rates of economic growth .

In the past decade, while Indian GDP has grown by around 6%, there has been a large decline in female labour force participation from 34% to 27%. The male-female wage gap has been stagnant at 50% (a recent survey finds a 27% gender pay gap in white-collar jobs).

Crimes against women show an upward trend , in particular brutal crimes such as rapes, dowry deaths, and honour killings. These trends are disturbing as a natural prediction would be that with growth comes education and prosperity, and a possible decline in adherence to traditional institutions and socially prescribed gender roles that hold women back.

A preference for sons

Cultural institutions in India, particularly those of patrilineality (inheritance through male descendants) and patrilocality (married couples living with or near the husband’s parents), play a central role in perpetuating gender inequality and ideas about gender-appropriate behaviour.

A culturally ingrained parental preference for sons - emanating from their importance as caregivers for parents in old age - is linked to poorer consequences for daughters.

The dowry system, involving a cash or in-kind payment from the bride’s family to the groom’s at the time of marriage, is another institution that disempowers women. The incidence of dowry payment, which is often a substantial part of a household’s income, has been steadily rising over time across all regions and socioeconomic classes.

This often results in dowry-related violence against women by their husbands and in-laws if the dowry is considered insufficient or as a way to demand more payments.

These practices create incentives for parents not to have girl children or to invest less in girls’ health and education. Such parental preferences are reflected in increasingly masculine sex ratios in India . In 2011, there were 919 girls under age six per 1000 boys, despite sex determination being outlawed in India.

This reinforces the inferior status of Indian women and puts them at risk of violence in their marital households. According to the National Family and Health Survey of 2005-06 , 37% of married women have been victims of physical or sexual violence perpetrated by their spouse.

Affirmative action

There is clearly a need for policy initiatives to empower women as gender disparities in India persist even against the backdrop of economic growth.

Current literature provides pointers from policy changes that have worked so far. One unique policy experiment in village-level governance that mandated one-third representation for women in positions of local leadership has shown promising results .

Evaluations of this affirmative action policy have found that in villages led by women, the preferences of female residents are better represented, and women are more confident in reporting crimes that earlier they may have considered too stigmatising to bring to attention.

Female leaders also serve as role models and raise educational and career aspirations for adolescent girls and their parents .

Behavioural studies find that while in the short run there is backlash by men as traditional gender roles are being challenged, the negative stereotype eventually disappears . This underscores the importance of sustained affirmative action as a way to reduce gender bias.

Another policy change aimed at equalising land inheritance rights between sons and daughters has been met with a more mixed response . While on the one hand, it led to an increase in educational attainment and age at marriage for daughters, on the other hand, it increased spousal conflict leading to more domestic violence.

Improvements in labour market prospects also have the potential to empower women. An influential randomisation study found that job recruiter visits to villages to provide information to young women led to positive effects on their labour market participation and enrolment in professional training.

This also led to an increase in age at marriage and childbearing, a drop in desired number of children, and an increase in school enrolment of younger girls not exposed to the programme.

Recent initiatives on training and recruiting young women from rural areas for factory-based jobs in cities provide economic independence and social autonomy that they were unaccustomed to in their parental homes.

Getting to parity

For India to maintain its position as a global growth leader, more concerted efforts at local and national levels, and by the private sector are needed to bring women to parity with men.

While increasing representation of women in the public spheres is important and can potentially be attained through some form of affirmative action, an attitudinal shift is essential for women to be considered as equal within their homes and in broader society.

Educating Indian children from an early age about the importance of gender equality could be a meaningful start in that direction.

This is the first of a series of articles in partnership with UNU-WIDER and EconFilms on responding to crises worldwide.

- Gender equality

- Development economics

- Women in India

- Responding to crises

- Global perspectives

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

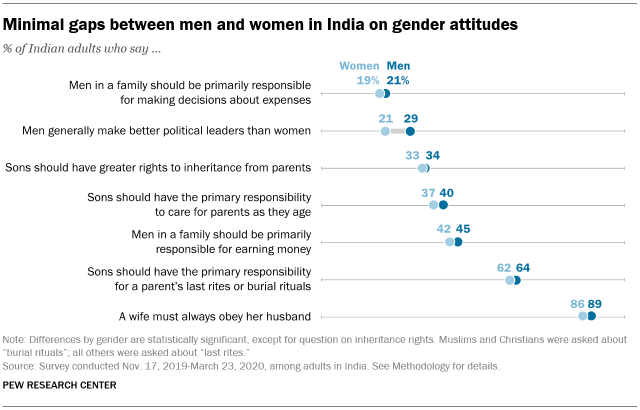

In india and many other countries, there is little gap between men and women in attitudes on gender issues.

Most Indians support gender equality, but a new Pew Research Center survey finds that traditional gender norms still hold sway for many people in the country. And even though traditional norms tend to give men, rather than women, more prominent roles in several aspects of family and public life, women do not differ substantially from men in their opinions on these issues.

One example is how Indians view interactions between husbands and wives. Asked if they agree with the statement that “a wife must always obey her husband,” women in India (86%) are only slightly less likely than Indian men (89%) to say they either completely or mostly agree.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to find out how men and women in India differ – or don’t – in their views toward gender roles. It is based primarily on the March 2022 report “ How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society ,” part of the Center’s most comprehensive, in-depth exploration of Indian public opinion to date. For this report, we surveyed 29,999 Indian adults ages 18 and older living in 26 Indian states and three union territories. Many findings from the survey in India were previously published in “ Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation ,” which looked in detail at religious and national identity, religious beliefs and practices, and attitudes among religious communities. Interviews for this nationally representative survey were conducted face-to-face in 17 languages from Nov. 17, 2019, to March 23, 2020.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design, and data was weighted to account for the different probabilities of selection among respondents, and to align with demographic benchmarks for the Indian adult population from the 2011 census.

We also relied on a 2019 survey of 34 countries to provide a global context for the India findings.

For more information on the India survey, read its methodology . Here are the questions used in this analysis.

Here are the questions used for the 34-nation survey, along with its methodology .

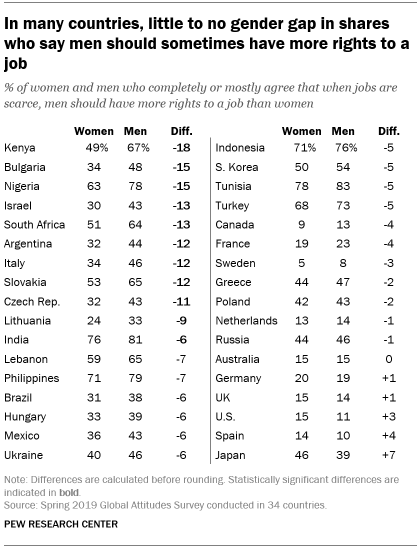

This phenomenon, where women are either as likely as or only modestly less likely than men to express traditional attitudes about gender, is not unique to India. In a different survey of 34 countries conducted by Pew Research Center in the spring and summer of 2019, only 11 countries had statistically significant differences between men and women in the shares who say that if jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to employment than women. This included India, where Indian women (76%) were only somewhat less likely than Indian men (81%) to hold this view. In other words, in most of the countries surveyed, women were about as likely as men to favor job preferences for men in times of high unemployment.

Another question on the same 34-country survey asked respondents how important it is for women to have the same rights as men in their country. In most countries surveyed, women are more likely than men to voice support for gender equality, but this pattern is far from universal. In 14 countries, including Brazil and Poland, roughly the same shares of men and women say equal rights for women are very important, and in an additional seven countries, gender gaps on this question are 10 percentage points or less. In India, women (75%) are only modestly more likely than men (70%) to support equal rights for both genders.

Gender differences also are muted when it comes to Indians’ views about relationships between children and their parents. In Indian society, sons historically have been the primary caregivers for aging parents and the main beneficiaries of inheritance. In line with these and other traditions, families have tended to place higher value on – and provide more support to – their sons than their daughters, a set of attitudes and practices known as “ son preference .”

Today, while most Indian adults believe that sons and daughters should have equal responsibility to care for parents as they age, women (37%) are almost as likely as men (40%) to say it is sons who should have the primary responsibility for this. And when asked whether sons or daughters should be primarily responsible for a parent’s last rites or burial rituals, women (62%) are nearly as likely as men (64%) to say it should be sons. In addition, most Indians say sons and daughters should have equal rights to inheritance from their parents, but about a third of both women (33%) and men (34%) say that sons should have greater inheritance rights than daughters.

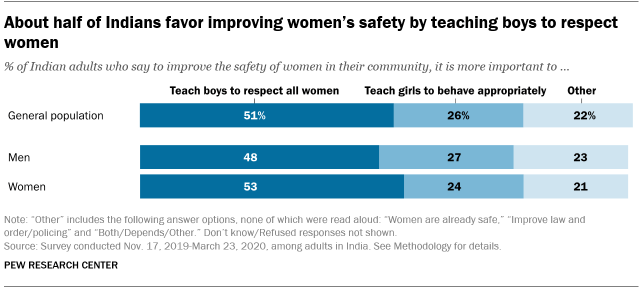

Against the backdrop of violence against women in India that has attracted both national and international attention, three-quarters of Indian men and women say violence against women is a “very big problem” in their country. The survey also asked respondents whether, to improve the safety of women in their community, it is more important to teach boys to respect all women or to teach girls to behave appropriately.

Around half of the Indian population – including 53% of women and 48% of men – says teaching boys to respect women is more important. But women (24%) are almost as likely as men (27%) to put the onus on women’s own behavior, saying that teaching girls to behave appropriately is the better way to improve women’s safety. Roughly a quarter of both men and women don’t take a clear position on the issue, with some saying both approaches are important, that women are already safe, or that the issue is one of law and order rather than gender norms.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Among U.S. couples, women do more cooking and grocery shopping than men

On gender differences, no consensus on nature vs. nurture, in their own words: why do americans say men or women have it easier in the u.s., americans see men as the financial providers, even as women’s contributions grow, sharing chores a key to good marriage, say majority of married adults, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

About Asian Indian Women: Stereotypes, Fabrications, and Lived Realities

- First Online: 13 July 2017

Cite this chapter

- Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman 5

1039 Accesses

2 Citations

Many scholars have emphasized the multiplicity of Indian women, but the need to continue to do so becomes clear when we look at the standard ways in which they are characterized. All too often, Indian women are caricatured as the innocent victims of a uniform “Indian tradition.” Furthermore, although the status of women in India is poor, as seen from several indicators, it is equally true that the status of women is inferior worldwide. Yet, caught up in their certainty that “other” women are abused and miserable, European bourgeois ideas of patriarchy, individualism, womanhood, and feminism are imposed on Indian women, ostensibly to explain their plight. Then, the multicultural narrative of female freedom is inevitably offered as a strategy to liberate them. This chapter offers a multidisciplinary summary of work on Indian women, and traces the sources of widely circulated and pervasive ideas and ideals of Indian womanhood. Against this backdrop, this chapter argues that only by listening to the multivocal and contextualized narratives and visions of personhood of Indian women themselves do we stand a chance of breaking out of the cognitive stranglehold of Western ideas of modernity and articulating indigenous frameworks of Indian womanhood.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Working with children or in the field of child development poses challenges similar to those encountered in working with women. See Balagopalan ( 2011 ) for the growing hegemony of the Convention on the Rights of the Child over defining children and childhood in the international policy discourse.

Taylor makes this claim more broadly about our moral reactions. I use it specifically to refer to the reaction of feminists to Indian women’s alternate rationality.

As Tuhiwai Smith ( 1999 ) and others inform us, the idea of progress as tied to literacy and education can be traced to Western conception of modernity.

In 2004, Karnataka became the first state to pass a minimum wage law, and in 2006, organized by the Stree Jagruti Samiti (Society for Awakened Women), 100,000 women domestic workers struck work, on a national level, for a prolonged period, demanding better conditions.

For a provocative and polemical critique of the sari as a garment, see Poonia ( 2012 ). Worth reading also are the responses that discuss the article and offer sharp rejoinders at http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1588&ptype

particularly Vanita’s ( 2012 ) response.

In 1975, the Department of Women and Child Development started crèches and day care centers for children of low-income working and ailing mothers. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) also runs crèches. The quality of care in these crèches leaves much to be desired.

Bhadramahila in Bengal.

These human capabilities, outlined by Nussbaum ( 1995 ), include: being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; good health; being able to avoid pain and have experiences that give pleasure; being able to imagine, think, and reason; being able to have attachments to both other people and other objects; being able to plan one’s own life; living for and with others; living in harmony with nature; enjoying life through laughter, play, and recreation; being able to make choices; and being able to live in one’s own context.

Kishwar’s ( 1990 ) essay “Why I do not call myself a feminist” offers a clear and insightful commentary on the pitfalls of adopting the ideology and concepts of Western feminism willy-nilly in India.

It is also well worth arguing that women’s status in Indian society will not change unless we bring men into the dialogue. This points to the need for socialization of boys into sensitive men (Bhangaokar, personal communication, February 16, 2014).

Abu-Lughod, L. (2013). Do Muslim women need saving? . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Amin, S. (1994). Introduction to William Crooke. In A glossary of North Indian peasant life. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Apffel-Marglin, F., & Marglin, S. A. (Eds.). (1990). Dominating knowledge: Development, culture and resistance . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Balagopalan, S. (2011). Introduction: Children’s lives and the Indian context. Childhood, 18 (3), 291–297.

Article Google Scholar

Berry, K. (2007). Lakshmi and the scientific housewife: A transnational account of Indian women’s development and the production of an Indian modernity. In R. B. S. Verma, H. S. Verma, & N. Hasnain (Eds.), The Indian state and women’s problematic: Running with the hare and hunting with the hounds (pp. 125–162). New Delhi, India: Serials Publications.

Bharat, S. (2003). Women, work and family in urban India: Towards new families? In R. C. Mishra, John W. Berry, & R. C. Tripathi (Eds.), Psychology in human and social development: Lessons from diverse cultures. A festschrift for Durganand Sinha (pp. 155–169). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Bromet, E., Andrade, L. H., Hwang, I., Sampson, N. A., Alonso, J., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., … Kessler, R. C. (2011). Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Medicine, 9 (90). http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/90 .

Chakraborty, K., & Basu, D. (2010). Management of anorexia and bulimia nervosa: An evidence-based review. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 52 (2), 174–186.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Channa, S. M. (2007). The “ideal Indian woman”: Social imagination and lived realities. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 37–52). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Channa, S. M. (2013). Gender in South Asia: Social imagination and constructed realities . New Delhi, India: Cambridge University Press.

Chatterjee, P. (1989). The nationalist resolution of the women’s question. In K. Sangari & S. Vaid (Eds.), Recasting women: Essays in colonial history (pp. 233–253). New Delhi, India: Kali for Women & Book Review Literary Trust.

Das, V. (1988). Femininity and the orientation to the body. In K. Chanana (Ed.), Women: Explorations in gender identity (pp. 193–207). New Delhi, India: Orient Longman.

Datta, S. (2000). Globalisation and representations of women in Indian cinema. Social Scientist, 28 (3/4), 71–82.

Dernè, S. (2000). Male Hindi filmgoers’ gaze: An ethnographic interpretation. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 34 (2), 243–269.

Dhruvarajan, V., & Vickers, V. D. J. (Eds.). (2002). Gender, race and nation: A global perspective . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Flueckiger, J. B. (2006). In Amma’s healing room: Gender and vernacular Islam in South India . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Ghosh, P., Arah, O. A., Talukar, A., Sur, D., Babu, G. R., Sengupta, P., et al. (2011). Factors associated with HIV infection among Indian women. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 22 (3), 140–145.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Government of India. (2011). Provisional population totals: India: Census 2011 . http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/indiaatglance.html

Government of India. (2005). Protection of women from domestic Violence Act . New Delhi, India: Government of India.

Karlekar, M. (2003). Domestic violence. In V. Das (Ed.), The Oxford India companion to sociology and social anthropology (Vol. 2, pp. 1127–1157). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Kishwar, M. (1990). Why I do not call myself a feminist. Manushi, 61, 2–8.

Kishwar, M. (1999). Off the beaten track: Rethinking gender justice for Indian women . New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Kumar, U. (2001). Indian women and work: A paradigm for research. In A. K. Dalal & G. Misra (Eds.), New directions in Indian psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 366–385). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Kurtz, S. N. (1992). All the mothers are one: Hindu India and the cultural reshaping of psychoanalysis . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lamb, S. (1997). The making and unmaking of persons: Notes on aging and gender in North India. Ethos, 25 (3), 279–302.

Lamb, S. (2000). White saris and sweet mangoes: Aging, gender and body in North India . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory . Oxford, UK & New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mammen, P., Russell, S., & Russell, P. S. (2007). Prevalence of eating disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity among children and adolescents. Indian Pediatrics, 44, 357–359.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mayo, K. (1927). Mother India . New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Menon, N., & Johnson, M. P. (2007). Patriarchy and paternalism in intimate partner violence. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 171–195). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Menon, U. (2002). Neither victim nor rebel: Feminism and the morality of gender and family life in a Hindu temple town. In R. Shweder, M. Minnow, & H. R. Markus (Eds.), Engaging cultural differences: The multicultural challenge in liberal democracies (pp. 288–308). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Menon, U. (2013). Women, wellbeing, and the ethics of domesticity in an Odia Hindu temple town . New York, NY: Springer.

Menon, U., & Shweder, R. A. (1998). The return of the “white man’s burden”: The moral discourse of anthropology and the domestic life of Hindu women. In R. A. Shweder (Ed.), Welcome to middle age (and other cultural fictions) . Chicago, IL & London: University of Chicago Press.

Minturn, L. (1993). Sita’s daughters: Coming out of purdah: The Rajput women of Khalapur revisited . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mohanty, S. (2007). Advice to housewives: ‘Conduct book’ tradition in Orissa. In K. K. Misra & J. H. Lowry (Eds.), Recent studies on Indian women (pp. 53–62). Jaipur & New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications.

Nelasco, S. (2010). Status of women in India . New Delhi, India: Deep & Deep Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Nussbaum, M. (1995). Human capabilities, female human beings. In M. Nussbaum & J. Glover (Eds.), Women, culture and development: A study of human capabilities (pp. 61–104). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Obeyesekere, G. (1985). Depression, Buddhism, and the work of culture in Sri Lanka. In A. Kleinman & B. Good (Eds.), Culture and depression (pp. 134–152). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Parameswaran, R., & Cardoza, K. (2009). Melanin on the margins: Advertising and the cultural politics of fair/light/white beauty in India. Journalism and Communication Monographs, 11 (3), 213–274.

Patel, T. (Ed.). (2007). Sex selective abortion in India: Gender, society and new reproductive technologies . New Delhi, India: Sage Publications Ltd.

Poonia, M.S. (2012). Political economy of the sari. Manushi. http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1585&ptype=

Raheja, G. G. (1994). Women’s speech genres, kinship and contradiction. In N. Kumar (Ed.), Women as subjects: South Asian Histories (pp. 49–80). Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Raheja, G. G., & Gold, A. G. (1994). Listen to the heron’s words: Reimagining gender and kinship in North India . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Raheja, G. G. (2010). ‘A splendid thing for the empire’: Some reflections on ethnography and entextualization in colonial India. In K. A. Leonard, G. Reddy, & A. G. Gold (Eds.), Histories of intimacy and situated ethnography (pp. 253–298.). New Delhi, India: Manohar.

Ramabai, P. (1887). The high-caste Hindu woman . New York, NY: Fleming H. Revell.

Raman, S. A. (2009). Women in India: A social and cultural history (Vols. 1 and 2). Santa Barbara, CA, Denver, CO, & Oxford, UK: Praeger.

Ray, S. (2000). Engendering India: Woman and nation in colonial and postcolonial narratives. Durham, NC, & London: Duke University Press.

Sangari, K., & Vaid, S. (Eds.). (1989). Recasting women: Essays in colonial history . New Delhi, India: Kali for Women.

Sarkar, S. (1985). The women’s question in nineteenth century Bengal. In K. Sangari & S. Vaid (Eds.), Women and culture (pp. 157–172). Bombay, India: SNDT University.

Sen, A. (1989). Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 41–58.

Sen, A. (1995). Gender inequality and theories of justice. In M. C. Nussbaum & J. Glover (Eds.), Women, culture and development: A study of human capabilities (pp. 259–273). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

Seymour, S. C. (1999). Women, family, and child care in India: A world in transition . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Shweder, R. A. (1985). Menstrual pollution, soul loss, and the comparative study of emotions. In A. Kleinman & B. Good (Eds.), Culture and depression (pp. 182–215). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Shweder, R. A. (2012). Relativism and universalism. In D. Fassin (Ed.), A companion to moral anthropology (pp. 85–102). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Sinha, M. (2006). Specters of Mother India: The global restructuring of an empire. Durham, NC, & London: Duke University Press.

Solomon, S., Buck, J., Chaguturu, S. K., Ganesh, A. K., & Kumarasamy, N. (2003). Stopping HIV before it begins: Issues faced by women in India. Nature Immunology, 4, 719–721.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). Urbana, Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Spivak, G. (1990). Questions of multiculturalism. In S. Harasayam (Ed.), The post colonial critic: Interviews, strategies, dialogues (pp. 59–60). New York, NY: Routledge.

Srinivasan, B. (2007). Negotiating complexities: A collection of feminist essays. New Delhi, India & Chicago, IL: Promilla & Co., Publishers & Bibliophile South Asia.

Srinivasan, T. N., Suresh, T. R., & Jayaram, V. (1998). Emergence of eating disorders in India: Study of eating distress syndrome and development of a screening questionnaire. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44 (3), 189–198.

Tagore, S. (2013). Representation of women in Indian cinema and beyond. In 19th Justice Sunanda Bhandare Memorial Lecture. New Delhi, India: India International Centre (IIC).

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, P. (1964). Indian women through the ages: A history of the position of women and the institutions of marriage and family in India from remote antiquity to the present day . Bombay, India: Asia Publishing House.

Trawick, M. (1992). Notes on love in a Tamil family . Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Trawick, M. (2003). The person beyond the family. In V. Das (Ed.), The Oxford Indian companion to sociology and social anthropology (Vol. 2, pp. 1158–1178). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples . London, New York: Zed Books Ltd.

Vanita, R. (2012). The sari: A garment for all seasons. Manushi. Retrieved from http://www.manushi.in/articles.php?articleId=1595&ptype

Vatuk, S. (2008). Islamic feminism in India: Indian Muslim women activists and the reform of Muslim personal law. Modern Asian Studies. Special Issue, Islam in South Asia, 42 (2, 3), 489–518.

Vatuk, S. (2002). Older women, past and present, in an Indian Muslim family. In S. Patel, J. Bagchi, & K. Raj (Eds.), Thinking social science in India: Essays in honour of Alice Thorner (pp. 247–263). New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Vatuk, S. (2001). ‘Where will she go? What will she do?’ Paternalism toward women in the administration of Muslim personal law in contemporary India. In G. J. Larson (Ed.), Religion and personal law in secular India: A call to judgment (pp. 226–238). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Vatuk, S. (1987). Power, authority and autonomy across the life course. In P. Hocking (Ed.), Essays in honor of David G. Mandelbaum (pp. 23–44). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Verma, H. S. (2007). India’s country reports on CEDAW: Separating facts from fiction in the “history” of women’s empowerment written by the Indian politico-administrative class. In H. S. Verma, N. Hasnain, & R. B. S. Verma (Eds.), The Indian state and women’s problematic: Running with the hare and hunting with the hounds (pp. 273–333). New Delhi, India: Serials Publications.

World Bank. (2012). HIV/AIDS in India . Retrieved January 10, 2014, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/07/10/hiv-aids-india

World Health Organization. (2016). Violence against women. Intimate partner and sexual violence against women . Retrieved May 1, 2016, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/

Suggested Readings and Resources for Further Study

Government of India. (2005). Protection of women from Domestic Violence Act . New Delhi, India: Government of India.

Download references

Acknowledgements

My gratitude to Usha Menon for generously pointing me to some of the literature around the topic. Sincere thanks are also due to Rachana Bhangaokar for her valuable critical comments on a draft of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto, Erindale Hall, 3359 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada

Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hemalatha Ganapathy-Coleman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Independent Scholar, Oak Park, California, USA

Carrie M. Brown

Department of Psychology, St. Francis College, Brooklyn, New York, USA

Uwe P. Gielen

Department of Psychology, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA

Judith L. Gibbons

Department of Clinical Psychology, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

Judy Kuriansky

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Ganapathy-Coleman, H. (2017). About Asian Indian Women: Stereotypes, Fabrications, and Lived Realities. In: Brown, C., Gielen, U., Gibbons, J., Kuriansky, J. (eds) Women's Evolving Lives. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58008-1_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58008-1_3

Published : 13 July 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-58007-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-58008-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- +44 0330 027 0207

- +1 (818) 532-6908

- [email protected]

- e-Learning Courses Online

- You are here:

What are Common Stereotypes About India?

A vast and vibrant country, India and Indian culture attract many stereotypes.

Although there might be a little truth in some, very few of these stereotypes are rooted in reality.

Stereotypes also tend to say something about the person, or people, holding them.

It's crucial for all us of to analyze and address the stereotypes we have of others.

By removing these misconceptions and twisted truths, it will help you to fully appreciate the richness of a culture and society; in this instance, India.

Here, we're going to look at 10 of the most common stereotypes we hear about India through our cross-cultural training programmes.

DON'T MISS THE FREE SAMPLE OF OUR ELEARNING COURSE ON INDIAN CULTURE AT THE END!

10 Stereotypes About India We Frequently Hear in Training!

1. indian people cannot speak good english.

Indian people tend to have great English. Why? Because English is the second official language of India and is widely spoken across the country.

The majority of schools across India teach students English right from the start of their formative years which means that it is possible to navigate the country using English alone and with no knowledge of any Indian language.

However, it is important to acknowledge that literacy levels in India are very low which means that higher standards of English tend to be concentrated within those who are educated and working professionals. At the same time, with the influx of Western influences – mainly through the media – into the Indian subcontinent, English references are spreading throughout the different Indian classes.

2. “Thank you kindly, please come again!”

In continuation with the point above comes the issue of the Indian accent, which has been particularised, stereotyped and exaggerated by comedians and the media.

It must be acknowledged that English is not the first language of the majority of Indian people , and that while travellers will often come across the distinct ‘Indian action’ at play, all Indians do not have the same, generalized accent.

In fact, there are distinct shifts in accents and ways of speaking across the many Indian regions. The comical generalization of the Indian accent is a sore point for many who are continuing to learn and improve their language. Be assured, imitations of Apu from the Simpsons will not be appreciated when interacting with Indian nationals.

Education is a big deal in India with many parents putting emphasis on gaining qualifications in order to secure proper careers.

Photo taken in Bengaluru, India by Nikhita S on Unsplash

3. Indians are uneducated

While literacy levels in India, and especially those of women, are not very high, it is important to remember that in a country with a population as high as India’s, it is inaccurate to make generalized assumptions about the entire nation.

The idea that Indians are uneducated is very inaccurate, and education is in fact held in high regard. There are hundreds of thousands of schools across the country, with officially recognized education systems varying from region to region.

Doctors and engineers top the list of professions in India, and MAs, MBAs and PhDs are common qualifications. The university system in India is extremely competitive, with the entry qualifications for some starting at 100%.

4. Indians are poor

There is a commonly held perception that all Indians are poor which is furthered by media portrayals of the country, as seen through the movie Slumdog Millionaire.

While it is true that a major proportion of the Indian populace lives under the poverty line and that there are many beggars within the nation and highly visible slums and shantytowns, this is not the case for the entire nation.

India holds a significant portion of the world’s richest people and there are a large number of Indian nationals who are billionaires – both within the country and abroad.

5. The ‘real India’ is dirty and chaotic

Many travellers come to India for the ‘real Indian experience’, which they associate with dirt, chaos, spontaneity, and confusion.

They live frugally: they eat cheap food, live in cheap hostels, don themselves in traditional Indian clothing and use public transport in an attempt to live the way ‘real Indians’ do.

By doing so, they overlook the huge presence of internationally renowned luxury hotels, shopping malls and designer stores, nightclubs, bars, and restaurants, which are becoming increasingly synonymous with the ‘new’ Indian society. This notion connects to the point preceding this one.

The many dichotomies in India – between the rich and the poor, the West and the East, the traditional and the modern – are highlighted through the dualities of Indian society, and this must be accepted and appreciated.

Believe it or not, pizza is extremely popular in India.

Photo by Shourav Sheikh on Unsplash

6. Indians only eat curry

Indian food abroad has become synonymous with curry, and this is very inaccurate as Indian food is multi-faceted, diverse, and expanses much more than a generic curry.

Indeed, curry is eaten by many in the country – but this statement itself is very vague and incorrect because there are numerous types of curries, in terms of the ingredients they use and the flavours they contain.

Finding ‘international’ cuisines from Chinese to Thai to Mexican, French and American in India is very easy in metropolitan cities, albeit difficult in smaller towns. It already hosts international chains like McDonald's, KFC, Subway, Costa Coffee, and Starbucks, and more are likely to appear in India in the years to come.

7. Indians all speak Hindu

Hindu is the religion , and Hindi is the language.

Due to the sheer diversity and size of India, there are many languages that are spoken and practised in the Indian Union.

Many schools in India – especially those in the South and the East – give precedence to their own languages, thereby not teaching Hindi. Hindi in its most preserved form is spoken largely in North India and is likely to be a second or third language for people in other regions.

If you want to hear some of the linguistic variety, plus how people use 'Hinglish', in India, then watch some TV!

Click here to check out the 3 best Indian shows on Netflix!

8. Indian women are subordinate to men

This stereotype is not completely untrue. In Indian society, gender is extremely hierarchical and favours men over women.

This is not unusual for a developing country and must be looked at in that context. Indian society is largely patriarchal and women are expected to be subordinate to their male counterparts. This is reflected in the skewed sex ratio and literacy rates of the country, which seriously disadvantage the female population.

Traditionally, women were expected to be the carers of their family, mothers and wives, before any other occupation. However, in recent times, this idea is starting to slowly crack, though largely in the upper and middle classes. More women are attending university and going on to hold jobs post-graduation. An increasing number of influential businesspeople in corporations and otherwise are also women.

As a result, more and more women prefer to achieve a certain degree of financial independence before marrying, settling down, and having children. Notably, India has also had a female president – the same came cannot be said of many other countries in the West.

For many Hindus, the cow is a sacred animal. Its horns symbolize the gods, its legs, the ancient Hindu scriptures or the "Vedas" and its udder, the four objectives of life (wealth, desire, righteousness and salvation).

Photo by Monthaye on Unsplash

9. Cows roam the streets of India

The notion of holy cows in India is one that is laden with a lot of curiosity and this stereotype is in fact very accurate!

When in India, you will see a large number of cows – both in farms and fields and on roads and beaches. One reason for the stray cows on the streets is due to the fact that they often wander away from their herds when their owners are transporting them from one locality to another, thus rendering them homeless and on the streets.

These cows are not dangerous, but it is not advisable to approach them or touch them because – despite living in the constant presence of humans and human activity – they may attack you and be infected with disease.

10. Indians worship millions of Gods

Ancient Hindu scriptures have revealed that the religion encompasses the worship of 330 million Gods!

Whilst this is true, it is important to remember that Hinduism is not a polytheistic religion – that is, it speaks of one God.

The millions of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu religion are in fact perceived to be representatives and avatars of the one supreme God – Brahman. So, the answer to the question of the true number of Hindu Gods and Goddesses is fluid and depends on who is asked.

Take a Course About Indian Culture

If you would like to find out more about India and Indian culture, then enrol on our India Cultural Awareness Training e-Learning course which has been developed by Indian culture and business professionals and is jam-packed with essential tips, guidance, case studies and quizzes.

CLICK HERE TO SEE A SAMPLE OF THE COURSE

You may also be interested in the following:

- What do Google Searches Tell us about Indian Culture?

- Inside Indian Culture - Tips when doing Business in India

- Why India is becoming a Top Expat Destination

- What is the Negotiation Style in India?

Main Photo by Fares Nimri on Unsplash

Related Posts

Why you need global dexterity when working with people from different cultures, why is understanding the culture key to successfully doing business in india, why india is becoming a top expat destination.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.commisceo-global.com/

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 or +1 (818) 532-6908

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 +1 (818) 532-6908

Search for something

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to find out how Indians view gender roles in families and society. It is based on the March 2022 report "How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society," and is part of the Center's most comprehensive, in-depth exploration of Indian public opinion to date.For this report, we surveyed 29,999 Indian adults ages 18 and older living in 26 ...

Sexism is the prejudice, stereotype, or discrimination, on the basis of sex, typically against women. 1 It is seen to exist in various socio-occupational fields all over the world, including the media. The media are often seen to underrepresent and misrepresent women as well as stereotype gender roles across the globe. 2 This article focuses on the Indian scenario involving portrayal of women ...

Traditional gender roles and stereotypes: Traditional gender ro les and stereotypes have played a significant role in perpetuating gender inequality in India. Historically, women have been ...

society. This article stress the esneed for sustained efforts to increase the involvement of both men and women to remove socio-cultural barriers, stereotypical attitudes, and violence against women for creating a gender-balanced society. Keywords: Patriarchy, Violence, Theoretical analysis, Feminist perspectives, Indian women,

influence Indian society. Examining its causes reveals entrenched traditional gender roles, economic disparities, and a dearth of women in ... of the primary causes of gender inequality in India is the persistence of traditional gender roles and stereotypes deeply embedded in society. These norms dictate that men are the breadwinners and women ...

imposing masculine and femininity character stereotypes in society, it maintains inequitable power relations between men and women. Gender relations, which are vibrant and complicated, have altered over time, and patriarchy is not a ... In Indian society, giving birth to a woman might be considered a curse. In ancient India, women were ...

Discrimination against women and girls is a pervasive and long-running phenomenon that characterises Indian society at every level. India's progress towards gender equality, measured by its ...

A steady increase in female voter participation has been observed across India, wherein the sex ratio of voters (number of female voters vis-à-vis male) has increased from 715 in the 1960s to 883 ...

In 14 countries, including Brazil and Poland, roughly the same shares of men and women say equal rights for women are very important, and in an additional seven countries, gender gaps on this question are 10 percentage points or less. In India, women (75%) are only modestly more likely than men (70%) to support equal rights for both genders.

Due to the social value attached to women's virginity and chastity, in contrast to men, many women in India have limited freedom of movement, opinion, and speech, and live lives that seclude them from potential external threats of rape or dishonor. Nevertheless, they are still exposed to dangers within the household.

Little girls are gentle, boys are tough. Of course, it's not all one sided. Gender stereotypes are placed on men also, with devastating ripple effects on Indian society. There is a widespread ...

and writers in Indian films has increased, and they contribute their unique viewpoints and experiences to the depiction of women on screen. Women have both directed and written films like Lipstick Under My Burkha® and Parched, which address topics like female sexuality and the patriarchy in Indian society. The need for more understanding and

Relationship Between Culture And Gender Inequality In India Swati Sharma M.Phil, Department of History, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, Lucknow, India. _____ Abstract: This paper throws light on the role played by culture and traditions specifically of Hindu religion in legitimising the subordinate position of women in Indian society.

SCM explores how groups are stereotyped on competence and warmth. This research utilizes the SCM to study India, a heterogenous society with diverse social groups. The purpose of this paper is to study caste stereotypes using SCM within India while also comparing two distinct regions of the country - the north and the south.

India and Indian culture attracts many stereotypes. In this blog we unpick the most common ones, such as poverty, lack of education, manners, accent and more. [email protected] +44 0330 027 0207 or +1 (818) 532-6908 ... In Indian society, gender is extremely hierarchical and favours men over women.

The law needs to be interpreted in a non-discriminatory manner, ensuring justice to women. Article 15, clause (1) and (2) of the Constitution of India, 1950, clearly refers to non-discrimination by the state in terms of race, caste, gender, religion and place of birth. Masculinity and femininity are social constructs.

space of society. Stereotypes, "largely the reflection of culture" than being empirical by nature, take the form of knowledge in Foucault‟s terms.[2] These are the manifestations of the prejudiced attitudes of people promoting ... In Indian society, where the matrimonial world is the ultimate world promising ...

Title: STEREOTYPING WOMEN IN INDIAN CINEMA. Abstract : Cinema is believed to entertain, to take the viewer to a world that is different from the. real one, a world which provides escape from the ...

The essay goes on to say that Singh's supposed "feminist" stance takes advantage of and hides marginalised identities. It also talks about how the market-based media industry has helped shape and push Singh's image. ... • To learn more about the things that might affect how gender stereotypes are seen in Indian society. Hypothesis: Null ...

The stereotypes mainly comprise Physical appearance, Profession, Behaviour, and Characteristics. Physical appearance: An individual's appearance gets determined by society according to their ...

Essay On Indian Stereotypes. 1308 Words6 Pages. With the advancement of our technological innovation, media have become part of our lives. The absolute trust in media encourages people to no longer analyze the situation and to quickly make assumptions based on what they saw or heard. Mass media abuses the power they gained by spreading ...