The Simpl Blog

Rise of e-commerce in india: 7 trends influencing growth.

2020 – the year of the pandemic was a game changer for the e-commerce industry, which witnessed hyper-growth, both in volume as well as in value terms.

The rise of e-commerce in India was accentuated by evolving spending patterns and shopping preferences with an estimated 30-40% growth in consumers that shifted from in-store shopping to online purchases. They prioritized convenience, no-contact home delivery and a seamless, touchless shopping experience.

The promising prospects of the e-commerce space is confirmed by IBEF , which opines that India’s e-commerce industry is expected to leapfrog to #2 globally by 2034. Further, the sector would be worth US$99 billion by 2024, a jump from US$30 billion in 2019, growing at a CAGR of 27%.

Additionally, segments like grocery and fashion/apparel would be key growth drivers. It is estimated that the size of the grocery market in India is valued at $380Bn (2019 ), comprising 60% of the retail market.

Source: IBEF

Key Trends in the Rise of E-commerce in India

A Goldman Sachs report indicates that online retail penetration levels are expected to jump to 11% by 2024 from 4.7% in 2019. Further the size in value terms of online grocery would swell 20X times to $29Bn in the next 5 years, from the current $2Bn in 2020.

The e-commerce growth rate in India till 2024 would exceed that of other countries like the US, UK, other European countries, Brazil and China. We shall look at some of the key trends that triggered the rise of e-commerce in India.

Increased participation and funding

Recognizing the huge business opportunity, the e-commerce sector is attracting increased investments as well as intense competition with several players foraying into the segment. In 2019 alone, e-commerce and consumer internet companies received inflows worth over $4.32 Bn by way of investments from PE and VC players.

A Grant Thornton report highlights the increased investments in 2020 namely PhonePe (USD 28 million), BigBasket (USD 50 million) and Nykaa (USD 13 million). Further, the cumulative investments of over USD 13 billion (INR 100,000 crore) by multiple business entities in the Jio platform will shake up the e-commerce market dynamics in the coming days.

Source: ET

Statistics indicate that BigBasket and Grofers commanded over 80% market share in 2019 . However, the entry of RIL into the e-commerce space is expected to be a major disruption. A Goldman Sachs study reveals that while online grocery clocked a 50% y-o-y growth, the online buying trend and RIL’s foray would boost the CAGR (2019-24) to 81%. With intense competition, one can expect the end-consumer to benefit with price discounts, bulk offers and consumer loyalty points.

Favourable Policy reforms

Another factor contributing to the success of e-commerce is the policy support offered by the Central Government, summarized below:

- 100% FDI is permitted in B2B e-commerce

- In the case of the marketplace model of e-commerce, 100% FDI under the automatic route is allowed

The Indian Govt: Leading by example

In August 2016 itself, the Indian Government took the digital plunge and launched a landmark portal under the common umbrella name Government e-marketplace (GeM), an online, digital B2B market place with the aim to bring in transparency and cost efficiency to the Government procurement process. Since then, the efforts have yielded positive results.

As per estimates (Sept 2020), India has saved to the tune of $1 billion as of date, since the transition of $400 billion public procurement to GeM. According to a BCG report, the platform has contributed up to 25% savings in Government expenditure.

Enhanced adoption of Digital payments

A complementary sector closely associated with the e-commerce space is the digital payments segment within the larger fintech landscape. A Grant Thornton report emphasizes that India would register the highest growth in the digital payments domain with an estimated 20.2% CAGR.

This is due to rapid digitalisation, huge user base, and proactive policy support from the Government and RBI. It spells good news for the e-commerce domain as the use of digital payment modes would find higher acceptance amongst e-commerce buyers.

Transactions surge during the festive season

The exponential hike in transactions during the festive seasons like Diwali is another trend seen during the rise of e-commerce in India. This year, owing to the pandemic and the preference to stay indoors, there was a huge jump in the transactions recorded during the festive months, as is confirmed from the below chart. It is estimated that the gross e-commerce sales touched a whopping $33Bn in the calendar year 2020 alone.

The emergence of the digital-savvy buyer and netizens

Higher internet penetration and mobile connectivity are also instrumental in driving the e-commerce user base in India. Another key factor is the Government’s favourable policies like Digital India, thrust on cashless payment options and the upcoming 5G telecom revolution in 2021.

By 2021, India’s internet users’ pool would include over 846 Mn , with 80% of this segment also having access to mobile. A report by Invest India states that by 2025, internet penetration would cover more than 55% of the entire population with a corresponding jump in online shoppers from the 15% in 2020 to 50% by 2026.

Internet users have indicated a preference for online e-commerce transactions. A study revealed that at the start of 2020, 74% stated they had made at least a single online purchase in the past month.

Higher purchasing power finds its way to e-commerce

The Indian middle class, defined as being aspirational and experimental in their purchases are fuelling the exponential growth of e-commerce. A PwC report highlights that by 2022, the Indian middle class, with an estimated annual income between $7.5k-37k will comprise the lion’s share of the population.

This segment with its new-found spending power is expected to channelise consumption-driven demand towards e-commerce platforms as a form of experimentation and exploring of new products and services. While the per capita consumption of rural Indians would grow 4.3x , the urban counterparts would witness a 3.5x increase.

Concluding thoughts on the Rise of E-commerce in India:

The rise of e-commerce in India shows no signs of stopping. The Government is drafting a comprehensive e-commerce policy law with proposed monetary incentives for stores and retailers that transition to e-commerce.

Additionally, with the mandatory requirement to display the country of origin and the thrust on ‘vocal for local’, one can expect that ‘Made in India’ products would enhance their market share. There is also a growing preference for specialisation with niche e-commerce players offering only apparel, furniture, jewelry or electronic goods.

The e-commerce industry too needs to reinvent itself to match the changing customer expectations. Removal of supply chain bottlenecks, on-time last-mile delivery along with switching from the point-to-point model to the hub and spoke model would enhance the global competitiveness of domestic e-commerce players.

- ← Riding the COVID storm How digital payments won consumer trust amidst shifting spending patterns

- Online Payments – The Transition Story →

You May Also Like

How the buy now pay later(bnpl) industry fared in 2020 and what lies ahead, india’s growing e-commerce sector goes mainstream – part 1, secure digital payments are mandatory in today’s world, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Speech Writing /

Speech on the Rise of E-Commerce for School Students in English

- Updated on

- Jan 5, 2024

Speech on the Rise of E-Commerce: Last day, I received a smartphone from an e-commerce website that was unavailable everywhere onsite. I was at the top of the world not just because I received the phone of my choice but also because the e-commerce company from which I ordered my handset gave me a cashback too, which was just half the price of an electronic device.

E-commerce has changed the scene of business worldwide. It has changed the way of buying and selling any commodity in trade. Prior, our presence was necessary for any purchase, but now we are getting the things, say electronic gadgets, furniture, books, or even groceries, packed food, and likewise, at the doorstep. Receiving all such goods and services with just one order is possible because of e-commerce companies.

Also Read: Speech on National Youth Day For Students In English

5-minutes Speech on the Rise of E-commerce

Greetings to all the fellow learners here. Today´s topic is centered around ¨Speech on the Rise of E-Commerce.¨

Electronic commerce, or e-commerce, refers to the buying and selling of goods and services over the Internet. E-commerce includes different types of segments for customers, which include food items, fashion, electronics, flight and train tickets, beauty and personal care products, sports and outdoors, toys and games, and services such as online learning, cloud storage, streaming services, and many more.

The history of retail shops entering the market is not new. A student from Standford University started the business by buying and selling marijuana, a psychoactive drug that comes from the cannabis plant. The person, rather than the first online businessman, used the Advanced Research Projects Agency´s Network (ARPANET), which was later shut down by the university.

The market for online retail businesses became progressively active with the entry of e-commerce businesses in 1995 with the launch of Amazon and eBay. The beginning of the transformative era of e-commerce keeps on expanding and is successful with more development and diversification every year. Also, accessibility to the internet, use of smartphones, consumer preferences, and providing service with convenience help the e-commerce business grow within a short period.

Who will deny shopping if consumers get a range of diverse products while sitting at home with competitive pricing? Moreover, e-commerce market strategies , innovative methods of selling a product, and engaging online experiences help secure online transactions, which not only enhance the customer experience but also help build trust.

Furthermore, the use of artificial intelligence and applications gave the customer an environment for a seamless and personalized online shopping experience.

From business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions to business-to-business (B2B) collaborations, the lives of customers have turned to ease and convenience, and this is made possible only because of the rise of e-commerce.

Talking regarding India, with the pride of being the 7th largest market for e-commerce businesses, we have successfully built up the trust and satisfaction of the customers in these online retail shops, which have earned revenue of 138 billion rupees and are expected to triple over the next three years, with a projected market volume of US$108,060.8 million by 2027.

However, as the saying goes, everything comes with a price, and so does the rise of e-commerce. The rise in e-commerce marks opportunities as well as challenges for customers and small business owners. On the one hand, these small businesses gain global market reach with reduced overhead expenses and increased visibility, but on the other hand, they face challenges in making their online presence.

Also, online fraudulent cases, with customers delivering damaged or replica products, turn the user experience bad and create an obstacle to the upswing of e-commerce businesses.

It is important to control the challenges for keeping the market of e-commerce growing with quality assurance measures, secure websites with a safe online presence, monitoring the customer reviews, clear return and refund exchange policies and investing in flexible infrastructure that helps in growing e-commerce business without any compromise in performance.

In conclusion, e-commerce not only seizes opportunities but also helps in giving a boom to sectors related to business. Just a balance is needed to remove the hurdles, if any, and make the customer feel like a digital king.

Also Read: Difference between E Commerce and E Business

10 Lines on The Rise of E-commerce

Here are the short and simple lines for the topic ¨The Rise of E-Commerce.¨

1. E-commerce refers to the buying and selling of goods and services over the Internet.

2. Most people love the convenience of shopping online.

3. The use of smartphones, consumer preferences, and providing service with convenience help the e-commerce business grow within a short period.

4. Small businesses are growing through the global market of e-commerce.

5. Safe and secure payment options have built on the trust of customers for online retail shopping.

6. One of the major reasons for the boom in the e-commerce sector was the pandemic of COVID-19.

7. Strategies like giving discounts on competitive prices, attract customers for more shopping.

8. It is important to control the challenges for keeping the market of e-commerce growing with quality assurance measures.

9. Mobile commerce helps individuals to shop online through smartphones.

10. E-commerce is a reflection of shifting to digital easiness shopping habits.

Ans. The reasons behind the rise of E-commerce are convenie nce, variety of products under one roof and competitive pricing among the brands.

Ans. Michael Aldrich is known as the father of E-commerce stores.

Ans. Talking regarding India, with the pride of being the 7th largest market for e-commerce businesses in the world.

Ans. Online food delivery is the fastest-growing E-commerce industry in the world.

Ans. Business-to-consumer (B2C) is the most popular type of E-commerce. It is a business where the selling and buying of products and services is done directly to individual consumers.

Related Articles

For more information on such interesting speech topics for your school, visit our speech writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Deepika Joshi

Deepika Joshi is an experienced content writer with expertise in creating educational and informative content. She has a year of experience writing content for speeches, essays, NCERT, study abroad and EdTech SaaS. Her strengths lie in conducting thorough research and ananlysis to provide accurate and up-to-date information to readers. She enjoys staying updated on new skills and knowledge, particulary in education domain. In her free time, she loves to read articles, and blogs with related to her field to further expand her expertise. In personal life, she loves creative writing and aspire to connect with innovative people who have fresh ideas to offer.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Related Expertise: Emerging Markets , Go-to-Market Strategy , International Business

Ten Things You Should Know About E-Commerce in India

July 06, 2022 By Nimisha Jain , Kanika Sanghi , and Nivedita Balaji

- Consumers in new online shopper cohorts are just as likely to be moderate to heavy buyers as longtime online shoppers.

- E- commerce spending by PIN code diverges sharply from offline spending.

- Smaller cities are playing an outsize role in the expansion of online shopping in India.

- Marketplaces now have more digital influence overall than search sites do.

- Social media and chat are a small but rapidly growing online-purchasing channel.

Our detailed survey of Indian consumers investigates the country’s explosive growth in online shopping--with extensive implications for businesses, platforms, and channels.

With the world’s lowest data and smartphone costs, growing internet penetration, and a proliferation of new online shopping channels, India is experiencing a dramatic rise in e-commerce and digitally influenced spending. In fact, the numbers of digitally influenced shoppers and online shoppers have grown rapidly in recent years, reaching 260 million to 280 million for the former and 210 million to 230 million for the latter in 2021. We expect these numbers to increase by 2.5 times over the next decade, accompanied by nearly sixfold growth in online retail spending. (See Exhibit 1.)

E-tail growth received a kick-start from the COVID-19 pandemic , which pushed many consumers to begin shopping online for the first time and encouraged existing shoppers to increase their online purchasing, as physical shopping channels closed or became difficult to access. The net effect was to accelerate growth in the number of online shoppers in India by approximately four years and in the amount of online spending by about three years. Shoppers who were new to online shopping made up 35% of total online buyers during the period from April to September 2020. (See Exhibit 2.)

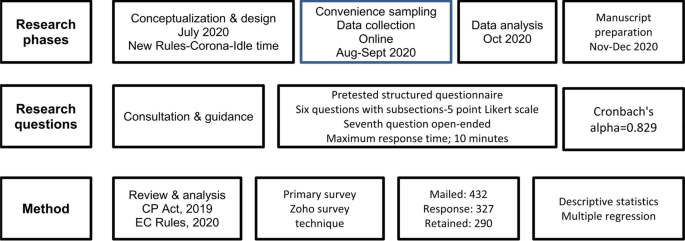

To fully explore this growth in digital and digitally influenced spending, we surveyed more than 10,000 consumers in India across a range of geographies and incomes, analyzed the online transaction data of more than 200,000 online shoppers, and interviewed multiple industry experts. (See “Our Methodology.”)

Our Methodology

The results provide detailed and extensive insights into Indian consumers’ shopping patterns and preferences . They also reveal a number of intriguing trends, including changes in who is shopping, where they live, what they buy, and how they shop.

For example, in a surprising divergence from the traditional Indian e-commerce shopper—the metropolitan millennial male—several new shopper cohorts that previously were e-commerce laggards turned to e-commerce as the pandemic began. Two potentially overlapping cohorts dominate this new-shopper category: the over-45 age group, which now accounts for more than a third of new shoppers in India and is the fastest growing segment; and the “next billion,” or middle-income population, which accounts for 38% of new online shoppers. In addition, Indian women are rapidly increasing their presence in the internet marketplace, where they already make up about 43% of the country’s new post-pandemic shoppers. (See Exhibit 3.)

We found that smaller cities are also contributing a great deal to India’s e-commerce growth. However, rural shoppers—consumers who live on farms or in towns and villages with populations of no more than 50,000 people—may be the future of e-commerce. Our study indicates that 54% of online shoppers in India will hail from rural areas by 2030, and that they will account for 24% of online retail spending. (See Exhibit 4.) The primary sources of this growth are the youngest adult cohort (ages 18 to 24) and the rural affluent (incomes of at least $13,000).

As more and more shoppers in India embrace the internet and e-commerce, they are also expanding the number of categories in which they buy online. Spurred by the onset of the pandemic , for example, they have added groceries and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) to their list of online go-to items. In fact, categories such as online food orders, FMCG, and beauty and personal care (BPC) items have seen sales grow by three to five times in recent years.

We expect the shape of e-commerce spending in India to continue to evolve along this path. Whereas mobile devices, electronics, and fashion once dominated e-commerce, food and FMCG will gain share from mobile and electronics. According to our projections, fashion and food and FMCG will account for nearly half of the e-tail market by 2030, up from just over 30% today. (See Exhibit 5.)

Our findings have extensive implications for businesses, platforms, and channels that cater to the evolving e-commerce buyer in India. These players can take a number of actions to keep abreast of the changing market , including understanding the needs of new cohorts and high-growth categories, adapting their e-commerce strategy to meet them, taking advantage of emerging opportunities, developing new go-to-market approaches, and working toward integrated and seamless customer journeys .

Whatever steps they choose, businesses should act quickly to attract consumers’ attention online, convert that attention into sales, and continue the conversation to keep their customers engaged.

Download the full report to read more about our detailed findings.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

Partner and Director, Center for Customer Insight

Mumbai - Nariman Point

Associate Director

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation

With more than half a billion internet subscribers, India is one of the largest and fastest-growing markets for digital consumers, but adoption is uneven among businesses. As digital capabilities improve and connectivity becomes omnipresent, technology is poised to quickly and radically change nearly every sector of India’s economy. That is likely to both create significant economic value and change the nature of work for tens of millions of Indians.

In Digital India: Technology to transform a connected nation (PDF–3MB), the McKinsey Global Institute highlights the rapid spread of digital technologies and their potential value to the Indian economy by 2025 if government and the private sector work together to create new digital ecosystems.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

India's consumers are taking a digital leap, uneven adoption among india's businesses has opened a digital gap, measuring the potential economic impact of digital applications in 2025, building digital ecosystems that connect, automate, and analyze, what are the implications for companies, policy makers, and individuals.

By many measures, India is well on its way to becoming a digitally advanced country. Propelled by the falling cost and rising availability of smartphones and high-speed connectivity, India is already home to one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing bases of digital consumers and is digitizing faster than many mature and emerging economies.

India had 560 million internet subscribers in September 2018, second only to China. Digital services are growing in parallel (Exhibit 1). Indians download more apps—12.3 billion in 2018—than any country except China and spend more time on social media—an average of 17 hours a week —than social media users in China and the United States. The share of Indian adults with at least one digital financial account has more than doubled since 2011, to 80 percent , thanks in large part to the government’s mass financial-inclusion program, Jan-Dhan Yojana.

To put this digital growth in context, we analyzed 17 mature and emerging economies across 30 dimensions of digital adoption since 2014 and found that India is digitizing faster than all but one other country in the study, Indonesia. Our Country Digital Adoption Index covers three elements: digital foundation (cost, speed, and reliability of internet service); digital reach (number of mobile devices, app downloads, and data consumption), and digital value, (how much consumers engage online by chatting, tweeting, shopping, or streaming). India’s score rose by 90 percent since 2014 (Exhibit 2). In absolute terms, its score is low—32 on a scale of 100—so there remains ample room to grow.

Public- and private-sector actions have driven digital growth so far

The public sector has been a strong catalyst for India’s rapid digitization. The government’s efforts to ramp up Aadhaar, the national biometric digital identity program, has played a major role. Aadhaar has enrolled 1.2 billion people since it was introduced in 2009, making it the single largest digital ID program in the world, hastening the spread of other digital services. For example, almost 870 million bank accounts were linked to Aadhaar by February 2018, compared with 399 million in April 2017 and 56 million in January 2014. Likewise, the Goods and Services Tax Network, established in 2013, brings all transactions of about 10.3 million indirect tax-paying businesses onto one digital platform, creating a powerful incentive for businesses to digitize their operations.

At the same time, private sector innovation has helped bring internet-enabled services to millions of consumers and made online usage more accessible. For example, Reliance Jio’s strategy of bundling virtually free smartphones with mobile-service subscriptions has spurred innovation and competitive pricing. Data costs have plummeted by more than 95 percent since 2013 and fixed-line download speeds quadrupled between 2014 and 2017. As a result, mobile data consumption per user grew by 152 percent annually—more than twice the rates in the United States and China (Exhibit 3).

Global and local digital businesses have recognized the opportunity in India and are creating services tailored to its consumers and unique operating conditions. Media companies are making content available in India’s 22 official languages, for example. And by tailoring its mobile payments and commerce platform to India’s market, Alibaba-backed Paytm has registered more than 100 million electronic “Know Your Customer”-compliant mobile wallet users and nine million merchants .

The pace of growth is helping India’s poorer states to narrow the digital gap with wealthier states. Lower-income states like Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand are expanding internet infrastructure such as base tower stations and increasing the penetration of internet services to new customers faster than wealthier states. Uttar Pradesh alone added close to 36 million internet subscribers between 2014 and 2018. Ordinary Indians in many parts of the country—including small towns and rural areas—can now read the news online, order food delivery via a phone app, video chat with a friend (Indians log 50 million video-calling minutes a day on WhatsApp), shop at a virtual retailer, send money to a family member using their phone, or watch a movie streamed to a handheld device.

Despite these advances, India has plenty of room to grow. Only about 40 percent of the populace has an internet subscription. While many people have digital bank accounts, 90 percent of all retail transactions in India, by volume, are still made with cash. E-commerce revenue is growing by more than 25 to 30 percent per year, yet only 5 percent of trade in India is done online, compared with 15 percent in China in 2015. Looking ahead, India’s digital consumers are poised for robust growth.

We surveyed more than 600 large and small companies in India to gauge the level of digitization in various sectors as well as the underlying traits, activities, and mind-sets that drive digitization at the firm level. We used each company’s answers to score its level of digitization and then ranked them in the MGI India Firm Digitization Index. Companies in the top quartile, which we characterize as digital leaders, had an average score of 58.2 (relative to a maximum potential value of 100), while those in the bottom quartile, the digital laggards, averaged 33.2. The median score was 46.2. A higher score indicates that the company is using digital in its day-to-day operations more extensively (implementing CRM systems, accepting digital modes of payments, etc.) and in a more organized manner (having separate analytics team, centralized digital organization, etc.) than the ones with lower scores.

Our survey found that, on average, leaders outscored others by 70 percent on strategy, 40 percent on organization, and 31 percent on capabilities (Exhibit 4).

Differences within sectors are higher than those across sectors. While some sectors have more digital leaders than others, top-quartile companies are found in all sectors—even those considered resistant to technology, such as farming or construction. Conversely, sectors with more leaders, such as information and communication technology, still have companies in the bottom quartile.

However, India’s digital leaders generally do share common traits in terms of the following areas:

- Digital strategy: Leaders are 30 percent more likely than bottom-quartile companies to fully integrate digital and global strategies and 2.3 times more likely to sell on e-commerce platforms. Leaders are 3.5 times more likely to say digital disruptions led them to change core operations and 40 percent more likely to say digital is a top priority for investment.

- Digital organization: Leaders are 14.5 times more likely than bottom-quartile companies to centralize digital management, and five times more likely to have a stand-alone, properly staffed analytics team. Top-quartile firms are also 70 percent more likely than bottom-quartile firms to say their CEO is “supportive and directly engaged” in digital initiatives.

- Digital capabilities: Leaders are 2.6 times more likely than bottom-quartile firms to use digital tools to manage customer relationships and 2.5 times more likely to use digital tools to coordinate the management of their core business operations.

The gap between digital leaders and other firms is not insurmountable. In some cases, even when the gap is large, lagging companies may be able to begin closing it by digitizing in small, relatively simple ways. Social media marketing is a good example. While bottom-quartile firms are much less likely than leaders to use social media, e-commerce, or listing platforms, each of these channels is cheap and easily accessible and there is little to stop a business owner with a high-speed internet connection and a smartphone from taking advantage of them.

For now, large companies (defined in our survey as having revenue greater than 5 billion rupees, or about $70 million) are more likely to have the financial resources and expertise needed to invest in some advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things. But growing high-speed internet connectivity and falling data costs may soon make some of these technologies available to small-business owners and even sole proprietors.

Indeed, our survey found small businesses are ahead of big companies in terms of accepting digital payments: 94 percent accept payment by debit or credit card, compared with only 79 percent of big companies; for digital wallets the difference was 78 percent versus 49 percent.

Our survey found 70 percent of small businesses use their own websites to reach clients, compared with 82 percent of big companies. Small businesses are less likely than big companies to buy display ads on the web (37 percent versus 66 percent), but they are ahead of big companies in connecting with customers via social media, and more likely to use search-engine optimization. More than 60 percent of the small firms surveyed use LinkedIn to hire talent, and about half believe that most of their employees today need basic digital skills. While only 51 percent of smaller firms said they “extensively” sell goods and services on their websites (compared with 73 percent of big businesses), small businesses use e-commerce platforms and other digital sales channels just as much as large firms and are equally likely to receive orders through digital means like WhatsApp.

Companies that innovate and digitize rapidly will be better placed to take advantage of India’s large, connected market, which could include up to 700 million smartphone users and 840 million internet users by 2023. In the context of rapidly improving technology and falling data costs, technology-enabled business models could become pervasive over the next decade. That will likely create significant economic value.

We consider economic impact in three broad areas. First are core digital sectors, such as IT-BPM, digital communications, and electronics manufacturing. Second are newly digitizing sectors such as financial services, agriculture, healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing, which are not traditionally considered part of India’s digital economy but have the potential to rapidly adopt new technologies. Third are government services and labor markets, which can use digital technologies in new ways.

Core digital sectors could double their GDP contribution by 2025

India’s core digital sectors accounted for about $170 billion—or 7 percent—of GDP in 2017–18. This comprises value added from core digital sectors: $115 billion from IT-BPM, $45 billion from digital communications, and $10 billion from electronics manufacturing. Based on industry revenue, cost structures, and growth trends, we estimate these sectors could grow significantly faster than GDP: value-added contribution in 2025 could range from $205 billion to $250 billion for IT-BPM, from $100 billion to $130 billion for electronics manufacturing, and $50 billion to $55 billion for digital communications. The total, between $355 billion and $435 billion, may account for 8 to 10 percent of India’s 2025 GDP.

Newly digitizing sectors are already creating added value

Alongside these already digitized sectors, India stands to create more value if it can nurture new and emerging digital ecosystems in sectors such as agriculture, education, energy, financial services, healthcare, and logistics. The benefits of digital applications in each of these newly digitizing sectors are already visible. For example, in logistics, tracking vehicles in real time has enabled shippers to reduce fleet turnaround time by 50 to 70 percent . Similarly, digitized supply chains help companies reduce their inventory by up to 20 percent. Farmers can cut the cost of growing crops by 15 to 20 percent using data on soil conditions that enables them to minimize the use of fertilizers and other inputs.

Digital can improve government services and the efficiency of India’s job market

Digital technologies can also create significant value in areas such as government services and the job market. Moving government subsidy transfers, procurement, and other transactions online can enhance public-sector efficiency and productivity, while creating online labor marketplaces could considerably improve the efficiency of India’s fragmented and largely informal job market.

To unlock this value will require widespread adoption and implementation. The economic value will be proportionate to the extent digital applications permeate production processes, from supply chains to delivery channels. Our estimates of potential economic value depend on each sector’s digital adoption rate by 2025; where the readiness of India’s firms and government agencies is low and significant effort will be required to catalyze broad-based digitization, adoption may be low, between 20 to 40 percent of the potential. Where private-sector readiness is high and government policy already supports large-scale digitization, adoption could be as high as 60 to 80 percent.

In all, we estimate that India’s newly digitizing sectors have the potential to create sizable economic value by 2025: from $130 billion to $170 billion in financial services, including digital payments; $50 billion to $65 billion in agriculture; $25 billion to $35 billion each in retail and e-commerce, logistics and transportation; and $10 billion in energy and healthcare (Exhibit 5). Digitizing more government services and benefit transfers could yield economic value of $20 billion to $40 billion, while digital skill-training and job-market platforms could yield up to $70 billion. While these ranges underscore large potential value, realization of this value is not guaranteed: losing momentum on government policies that enable the digital economy would mean India could realize less than half of the potential value by 2025.

Digital can create jobs but will require new skills and some labor redeployment

Changes brought by digital adoption will disrupt India’s labor force as well as its industries. We estimate that as many as 60 million to 65 million new jobs could be created from the direct and indirect impact of productivity-boosting digital applications. These jobs could be enabled in industries as diverse as construction and manufacturing, agriculture, trade and hotels, IT-BPM, finance, media and telecom, and transport and logistics.

However, some work will be automated or rendered obsolete. We estimate that all or parts of 40 million to 45 million existing jobs could be affected by 2025. These include data-entry operators, bank tellers, clerks, and insurance claims- and policy-processing staff. Millions of people who currently hold these positions will need to be retrained and redeployed.

Jobs of the future will be more skill-intensive. Along with rising demand for skills in emerging digital technologies (such as the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and 3-D printing), demand for higher cognitive, social, and emotional skills , such as creativity, unstructured problem solving, teamwork, and communication, will also increase. These are skills that machines, for now, are unable to master. As the technology evolves and develops, individuals will need to constantly learn and relearn marketable skills throughout their lifetime. India will need to create affordable and effective education and training programs at scale, not just for new job market entrants but also for midcareer workers.

To capture the potential economic value that we size at a macro level, businesses will need to deliver digital technologies at a micro level: that is, how they use digital technologies to fundamentally alter day-to-day activities.

Three digital forces will drive these shifts: One is the greater ease with which people can connect, collaborate, transact, and share information; another is the opportunity for companies to increase productivity by automating routine tasks; the third is the greater ease with which organizations can analyze data to make insights and improve decision making.

The interplay of these forces will create new data ecosystems, which in turn will spur new products, services, and channels in virtually every business sector, and create economic value for consumers as well as those members of the ecosystem that best adapt their business models.

To highlight the kinds of business model changes that companies should predict and prepare for, we examine how this connect-automate-analyze trio can play out across four sectors: agriculture, healthcare, retail, and logistics.

Digital agriculture

India’s farms are small, averaging a little more than one hectare in size, with yields ranging from 50 to 90 percent of those in Brazil, China, and other developing economies. Many factors contribute to this. Indian farmers have a dearth of farm machinery and relatively little data on soil, weather, and other variables. Poor storage and logistics allows produce to go to waste before reaching consumers— $15 billion worth in 2013.

Digital technology can alter this ecosystem in several ways. Precision advisory services—using real-time granular data to optimize inputs such as fertilizer and pesticides—can increase yields by 15 percent or more. After harvest, farmers could use online marketplaces to transact with a larger pool of potential buyers. One such platform, the government’s electronic National Agriculture Market, has helped farmers increase revenue by up to 15 percent . Furthermore, online banking can provide the financial data farmers need to qualify for cheaper bank credit. Digital land records can make crop insurance more available. These and other digital innovations in Indian agriculture can help add $50 billion to $65 billion of economic value by 2025.

Digital healthcare

India has too few doctors, not enough hospital beds, and a low share of state spending on healthcare relative to GDP. While life expectancy has risen to 68.3 years from 37 in 1951, the country still ranks 125th among all nations on this parameter. Indian women are three times as likely to die in childbirth as women in Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa—and ten times as likely as women in the United States.

Digital solutions can help alleviate the shortage of medical professionals by making doctors and nurses more productive. Telemedicine, for example, enables doctors to consult with patients over a digital voice or video link rather in person; this could allow them to see more patients overall and permit doctors in cities to serve patients in rural areas. Telemedicine could also be more cost effective: in trials and pilots, it cut consultation costs by about 30 percent. If telemedicine replaced 30 to 40 percent of in-person outpatient consultations, coupled with digitization in overall healthcare industry, India could save up to $10 billion in 2025.

Digital retail

More than 80 percent of all retail outlets in India—most of them sole proprietors or mom-and-pop shops—operate in the cash-driven informal economy. These businesses do not generate the financial records needed to apply for bank loans, limiting their growth potential. Large retailers have their own sets of challenges. Their reliance on manual store operations and high inventory levels is capital heavy. In many cases, their marketing practices are ineffective, and their prices are static regardless of inventory or demand.

Digital solutions could reshape much of the sector. E-commerce enables retailers to expand without capital-intensive physical stores. Some do not even bother with their own website, relying instead on third-party sites such as Amazon, which offer large, ready pools of shoppers along with logistics, inventory, and payment services, and customer data analytics. E-commerce creates financial records that attest to the creditworthiness of both buyers and sellers, making it cheaper to borrow. Digital marketing can inexpensively engage customers and build brand loyalty. We estimate e-commerce in India will grow faster than sales at brick-and-mortar outlets, allowing digital retail to increase its share of trade from 5 percent now to about 15 percent by 2025.

Digital logistics

India’s economy has grown by at least 6.5 percent annually for the last 20 years. Continuing at that pace of growth would challenge India’s logistics network, which already suffers from a fragmented trucking industry, inadequate railways infrastructure, and a shortage of warehousing. India spends about 14 percent of GDP on logistics, compared with 8 percent in the United States, according to McKinsey estimates.

Digital technology can disrupt even this traditional, physical sector. The government is creating a transactional e-marketplace, the National Logistics Platform , to connect shipping agencies, inland container depots, port authorities, banks, insurers, customs officials, and railways managers. By letting stakeholders share information and coordinate plans, the platform may speed up deliveries, reduce inventory requirements, and smooth order processing. At the same time, private firms are using digital technologies to streamline operations by moving freight booking online, automating customer service, installing tracking devices to monitor cargo movements, using real-time weather and traffic data to map efficient routes, and equipping trucks with internet-linked sensors to alert dispatchers when a vehicle needs servicing. According to McKinsey estimates, digital interventions that result in higher system efficiency and better asset utilization can reduce logistics cost by 15 to 25 percent.

For India to reap the full benefits of digitization—and minimize the pain of transitioning to a digital economy—business leaders, government officials, and individual citizens will need to play distinct roles while also working together.

Business leaders will need to assess how and where digital may disrupt their company and industry and set priorities for how to adapt. Potential disruptions and benefits may be particularly large in India because of its scale, the rapid pace of digitization, and its relatively low productivity in many sectors. To benefit from these changes, companies need to act quickly and decisively to both adapt existing business models and to digitize internal operations. In this context, four imperatives stand out.

First, companies will need to take smart risks as they adapt current business models and adopt new, disruptive ones. Only 46 percent of Indian companies in our survey have an organization-wide plan to change their core operations to react to large-scale disruption.

Second, digital should be front of mind as executives plan. Customers are more digitally literate and have come to expect the convenience and speed of digital, whether shopping online or questioning a bill, but many companies have not reacted. In our survey, 80 percent of firms cite digital as a “top priority,” but only 41 percent say their digital strategy is fully integrated with their overall strategy.

Indian companies will need to invest in building digital capabilities, especially hiring people with the skills needed to start and accelerate a digital transformation.

Third, Indian companies will need to invest in building digital capabilities, especially hiring people with the skills needed to start and accelerate a digital transformation. That is challenging because many of India’s most talented workers emigrate. Companies could work with universities to recruit and develop skilled workers, beginning with digital natives who are currently in universities or have recently finished their studies. Companies also need to build deeper technology understanding and capabilities at all levels, including in the C-suite.

Finally, firms will need to be agile and think of themselves as digital-first organizations. This may need a new attitude that starts with a “test and learn” mind-set that encourages rapid iteration and has a high tolerance for failure and redeployment.

India’s government has done much to encourage digital progress, from rationalizing regulations to improving infrastructure to launching Digital India, an ambitious initiative to double the size of the country’s digital economy. However, much needs to be done for India to realize its full potential.

National and state governments can help by partnering with the private sector to drive digitization, starting by putting the technology at the core of their operations. This helps by providing a market for digital solutions, which generates revenue for providers, encourages digital start-ups, and gives individuals more reasons to go online—whether to receive a cooking-gas subsidy, register a property purchase, or access any other government service.

Governments also can help by creating and administering public data sources that entrepreneurs can use to improve existing products and services and create new ones; by fostering a regulatory environment that supports digital adoption and protects citizens’ privacy; and by facilitating the evolution of labor markets in industries disrupted by automation.

Individuals

Individual Indians are already reaping the benefits of digitization as consumers, but they will need to be cognizant that its disruptive powers can affect their lives and work in other fundamental ways. For example, they will need to be aware of how digitally driven automation may change their work and what skills they will need to thrive in the future. Individuals will also need to become stewards of their personal data and skeptical consumers of information.

While India’s public and private sectors have propelled the country into the forefront of the world’s consumers of internet and digital applications over the past few years, its digitization story is far from over.

Navigating the emerging digital landscape will not be easy, but it is one of the golden keys to India’s future growth and prosperity. Unlocking the opportunities will be a challenge for the government, for businesses large and small, and for individual Indians, and there will be pain along with gains. But if India can accelerate its digital growth trajectory, the rewards will be palpable to millions of businesses and hundreds of millions of its citizens.

Stay current on your favorite topics

Explore a career with us, related articles.

Globalization in transition: The future of trade and value chains

A new emphasis on gainful employment in India

The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in India, 2018

Advertisement

E-Commerce and Consumer Protection in India: The Emerging Trend

- Original Paper

- Published: 09 July 2021

- Volume 180 , pages 581–604, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Neelam Chawla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2161-1102 1 &

- Basanta Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3339-7481 2

70k Accesses

33 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

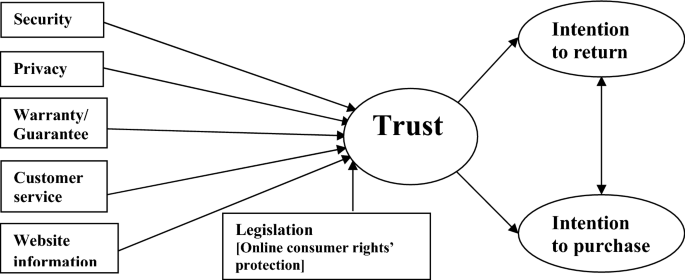

Given the rapid growth and emerging trend of e-commerce have changed consumer preferences to buy online, this study analyzes the current Indian legal framework that protects online consumers ’ interests. A thorough analysis of the two newly enacted laws, i.e., the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 and Consumer Protection (E-commerce) Rules, 2020 and literature review support analysis of 290 online consumers answering the research questions and achieving research objectives. The significant findings are that a secure and reliable system is essential for e-business firms to work successfully; cash on delivery is the priority option for online shopping; website information and effective customer care services build a customer's trust. The new regulations are arguably strong enough to protect and safeguard online consumers' rights and boost India’s e-commerce growth. Besides factors such as s ecurity, privacy, warranty, customer service, and website information, laws governing consumer rights protection in e-commerce influence customers’ trust. Growing e-commerce looks promising with a robust legal framework and consumer protection measures. The findings contribute to the body of knowledge on e-commerce and consumer rights protection by elucidating the key factors that affect customer trust and loyalty and offering an informative perspective on e-consumer protection in the Indian context with broader implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital payments and consumer experience in India: a survey based empirical study

Sudiksha Shree, Bhanu Pratap, … Sarat Dhal

“Untact”: a new customer service strategy in the digital age

Sang M. Lee & DonHee Lee

The role of data privacy in marketing

Kelly D. Martin & Patrick E. Murphy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Study Background

The study context, which discusses two key aspects, namely the rationale for consumer protection in e-commerce and its growth, is presented hereunder:

The Rationale for Consumer Protection in E-commerce

Consumer protection is a burning issue in e-commerce throughout the globe. E-Commerce refers to a mechanism that mediates transactions to sell goods and services through electronic exchange. E-commerce increases productivity and widens choice through cost savings, competitiveness and a better production process organisation Footnote 1 (Vancauteren et al., 2011 ). According to the guidelines-1999 of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), e-commerce is online business activities-both communications, including advertising and marketing, and transactions comprising ordering, invoicing and payments (OECD, 2000 ). OCED-1999 guidelines recognised, among others, three essential dimensions of consumer protection in e-commerce. All consumers need to have access to e-commerce. Second, to build consumer trust/confidence in e-commerce, the continued development of transparent and effective consumer protection mechanisms is required to check fraudulent, misleading, and unfair practices online. Third, all stakeholders-government, businesses, consumers, and their representatives- must pay close attention to creating effective redress systems. These guidelines are primarily for cross-border transactions (OECD, 2000 ).

Considering the technological advances, internet penetration, massive use of smartphones and social media penetration led e-commerce growth, the OECD revised its 1999 recommendations for consumer protection in 2016. The 2016-guidelines aim to address the growing challenges of e-consumers’ protection by stimulating innovation and competition, including non-monetary transactions, digital content products, consumers-to-consumers (C2C) transactions, mobile devices, privacy and security risks, payment protection and product safety. Furthermore, it emphasises the importance of consumer protection authorities in ensuring their ability to protect e-commerce consumers and cooperate in cross-border matters (OECD, 2016 ). The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in its notes-2017, also recognises similar consumer protection challenges in e-commerce. The notes look into policy measures covering relevant laws and their enforcement, consumer education, fair business practices and international cooperation to build consumer trust (UNCTAD, 2017 ).

E-commerce takes either the domestic (intra-border) route or cross-border (International) transactions. Invariably, six e-commerce models, i.e. Business-to-Consumer (B2C), Business-to-Business (B2B), Consumer-to-Business (C2B), Consumer-to-Consumer (C2C), Business-to-Administration (B2A) and Consumer-to-Administration (C2A) operate across countries (UNESAP and ADB, 2019 ; Kumar & Chandrasekar, 2016 ). Irrespective of the model, the consumer is the King in the marketplace and needs to protect his interest. However, the focus of this paper is the major e-commerce activities covering B2B and B2C.

The OECD and UNCTAD are two global consumer protection agencies that promote healthy and competitive international trade. Founded in 1960, Consumer International Footnote 2 (CI) is a group of around 250 consumer organisations in over 100 countries representing and defending consumer rights in international policy forums and the global marketplace. The other leading international agencies promoting healthy competition in national and international trade are European Consumer Cooperation Network, ECC-Net (European Consumer Center Network), APEC Electronic Consumer Directing Group (APECSG), Iberoamerikanische Forum der Konsumer Protection Agenturen (FIAGC), International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Agencies (Durovic, 2020 ).

ICPEN, in the new form, started functioning in 2002 and is now a global membership organisation of consumer protection authorities from 64 countries, including India joining in 2019 and six observing authorities (COMESA, EU, GPEN, FIAGC, OECD and UNCTAD). While it addresses coordination and cooperation on consumer protection enforcement issues, disseminates information on consumer protection trends and shares best practices on consumer protection laws, it does not regulate financial services or product safety. Through econsumer.gov Footnote 3 enduring initiative, ICPEN, in association with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), redresses international online fraud. Footnote 4 Econsumer.gov, a collaboration of consumer protection agencies from 41 countries around the world, investigates the following types of international online fraud:

Online shopping/internet services/computer equipment

Credit and debit

Telemarketing & spam

Jobs & making money

Imposters scam: family, friend, government, business or romance

Lottery or sweepstake or prize scams

Travel & vacations

Phones/mobile devices & phone services

Something else

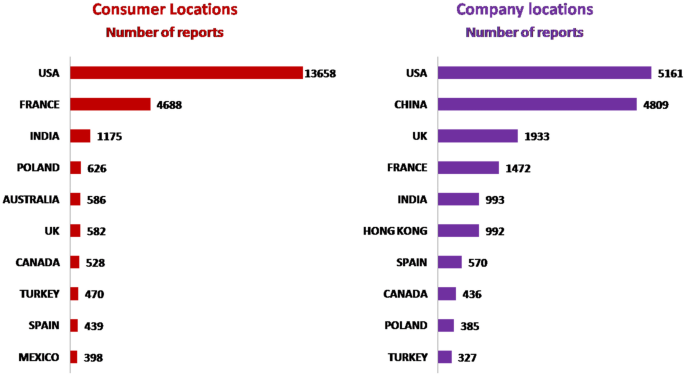

Online criminals target personal and financial information. Online trading issues involve scammers targeting customers who buy/sell/trade online. Table 1 on online cross-border complaints of fraud reported by econsumer.gov reveals that international scams are rising. Total cross-border fraud during 2020 (till 30 June) was 33,968 with a reported loss of US$91.95 million as against 40,432 cases with a loss of US$ 151.3 million and 14,797 complaints with the loss of US$40.83 million 5 years back. Among others, these complaints included online shopping fraud, misrepresented products, products that did not arrive, and refund issues. Figure 1 shows that the United States ranked first among the ten countries where consumers lodged online fraud complaints based on consumer and business locations. India was the third country next to France for online fraud reporting in consumer locations, while it was the fifth nation for company location-based reporting. Besides the USA and India, Poland, Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Turkey, Spain, and Mexico reported many consumer complaints. Companies in China, the United Kingdom, France, Hong Kong, Spain, Canada, Poland and Turkey received the most complaints. The trend is a serious global concern, with a magnitude of reported loss of above 60%.

Source: Data compiled from https://public.tableau.com/profile/federal.trade.commission#!/vizhome/eConsumer/Infographic , Accessed 7 October 2020

Online shopping-top consumer locations and company locations.

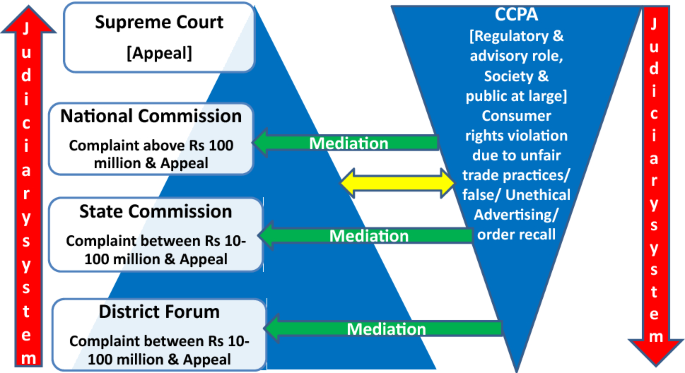

The international scenario and views on consumer protection in e-commerce provide impetus to discuss consumer protection in e-business in a regional context-India. The reason for this is that India has become a leading country for online consumer fraud, putting a spotlight on electronic governance systems-which may have an impact on India's ease of doing business ranking. However, to check fraud and ensure consumer protection in e-commerce, the government has replaced the earlier Consumer Protection Act, 1986, with the new Act-2019 and E-Commerce Rule-2020 is in place now.

E-commerce Growth

E-commerce has been booming since the advent of the worldwide web (internet) in 1991, but its root is traced back to the Berlin Blockade for ordering and airlifting goods via telex between 24 June 1948 and 12 May 1949. Since then, new technological developments, improvements in internet connectivity, and widespread consumer and business adoption, e-commerce has helped countless companies grow. The first e-commerce transaction took place with the Boston Computer Exchange that launched its first e-commerce platform way back in 1982 (Azamat et al., 2011 ; Boateng et al., 2008 ). E-commerce growth potential is directly associated with internet penetration (Nielsen, 2018 ). The increase in the worldwide use of mobile devices/smartphones has primarily led to the growth of e-commerce. With mobile devices, individuals are more versatile and passive in buying and selling over the internet (Harrisson et al., 2017 ; Išoraitė & Miniotienė, 2018 ; Milan et al., ( 2020 ); Nielsen, 2018 ; Singh, 2019 ; UNCTAD, 2019a , 2019b ). The growth of the millennial digital-savvy workforce, mobile ubiquity and continuous optimisation of e-commerce technology is pressing the hand and speed of the historically slow-moving B2B market. The nearly US$1 Billion B2B e-commerce industry is about to hit the perfect storm that is driving the growth of B2C businesses (Harrisson et al., 2017 ). Now, e-commerce has reshaped the global retail market (Nielsen, 2019 ). The observation is that e-commerce is vibrant and an ever-expanding business model; its future is even more competitive than ever, with the increasing purchasing power of global buyers, the proliferation of social media users, and the increasingly advancing infrastructure and technology (McKinsey Global Institute, 2019 ; UNCTAD, 2019a , 2019b ).

The analysis of the growth trend in e-commerce, especially since 2015, explains that online consumers continue to place a premium on both flexibility and scope of shopping online. With the convenience of buying and returning items locally, online retailers will increase their footprint (Harrisson et al., 2017 ). Today, e-commerce is growing across countries with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15% between 2014 and 2020; it is likely to grow at 25% between 2020 and 2025. Further analysis of e-commerce business reveals that internet penetration will be nearly 60% of the population in 2020, and Smartphone penetration has reached almost 42%. Among the users, 31% are in the age group of 25–34 years old, followed by 24% among the 35–44 years bracket and 22% in 18–24 years. Such a vast infrastructure and networking have ensured over 70% of the global e-commerce activities in the Asia–Pacific region. While China alone accounts for US$740 billion, the USA accounts for over US$$560 billion (Kerick, 2019 ). A review of global shoppers making online purchases (Fig. 2 ) shows that consumers look beyond their borders-cross-border purchases in all regions. While 90% of consumers visited an online retail site by July 2020, 74% purchased a product online, and 52% used a mobile device.

Source: Data compiled from https://datareportal.com/global-dig ital-overview#: ~ :text = There%20are%205.15%20billion%20unique,of%202.4%20percent%20per%20 year and , Accessed 12 October 2020

Global e-commerce activities and overseas online purchase.

The e-commerce uprising in Asia and the Pacific presents vast economic potential. The region holds the largest share of the B2C e-commerce market (UNCTAD, 2017 ). The size of e-commerce relative to the gross domestic product was 4.5% in the region by 2015. E-commerce enables small and medium-sized enterprises to reach global markets and compete on an international scale. It has improved economic efficiency and created many new jobs in developing economies and least developed countries, offering them a chance to narrow development gaps and increase inclusiveness—whether demographic, economic, geographic, cultural, or linguistic. It also helps narrow the rural–urban divide.

Nevertheless, Asia’s e-commerce market remains highly heterogeneous. In terms of e-commerce readiness—based on the UNCTAD e-commerce index 2017, the Republic of Korea ranks fifth globally (score 95.5) while Afghanistan, with 17 points, ranks 132 (UNCTAD, 2017 ). According to a joint study (2018) by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) and Asian Development Bank (ADB), Asia is the fastest-growing region in the global e-commerce marketplace. The region accounted for the largest share of the world’s business-to-consumer e-commerce market (UNESCAP and ADB, 2019). World Retail Congress (2019) brought out the Global E-Commerce Market Ranking 2019 assessing the top 30 ranking e-commerce markets on various parameters-USA, UK, China, Japan and Germany were the first top countries. India figured at 15 with a CAGR of 19.8% between 2018 and 2022. The report suggests that companies need to enhance every aspect of online buying, focusing on localised payment mode and duty-free return. Footnote 5 The observation of this trend implies online consumers’ safety and security.

Figure 3 explains that global cross-border e-commerce (B2C) shopping is growing significantly and is estimated to cross US$1 Trillion in 2020. Adobe Digital Economic Index Survey-2020 Footnote 6 in March 2020 reported that a remarkable fact to note is about steadily accelerated growth in global e-commerce because of COVID-19. While virus protection-related goods increased by 807%, toilet paper spiked by 231%. Online consumers worldwide prefer the eWallet payment system. The survey also revealed an exciting constellation that COVID-19 is further pushing overall online inflation down.

Source: Authors’ compilation from https://www.invespcro.com/blog/cross-border-shopping/ , Accessed on 15 October 2020

Global cross-border e-commerce (B2C) market. *Estimated to cross US$ 1 Trillion in 2020.

According to UNCTD’s B2C E-Commerce Index 2019 survey measuring an economy’s preparedness to support online shopping, India ranks 73rd with 57 index values, seven times better than the 80th rank index report 2018 (UNCTAD, 2019a , 2019b ). The E-commerce industry has emerged as a front-runner in the Indian economy with an internet penetration rate of about 50% now, nearly 37% of smartphone internet users, launching the 4G network, internet content in the local language, and increasing consumer wealth. Massive infrastructure and policy support propelled the e-commerce industry to reach US$ 64 billion in 2020, up by 39% from 2017 and will touch US$ 200 by 2026 with a CAGR of 21%. Footnote 7 Now, India envisions a five trillion dollar economy Footnote 8 by 2024. It would be difficult with the present growth rate, but not impossible, pushing for robust e-governance and a digitally empowered society. The proliferation of smartphones, growing internet access and booming digital payments and policy reforms are accelerating the growth of the e-commerce sector vis-a-vis the economy.

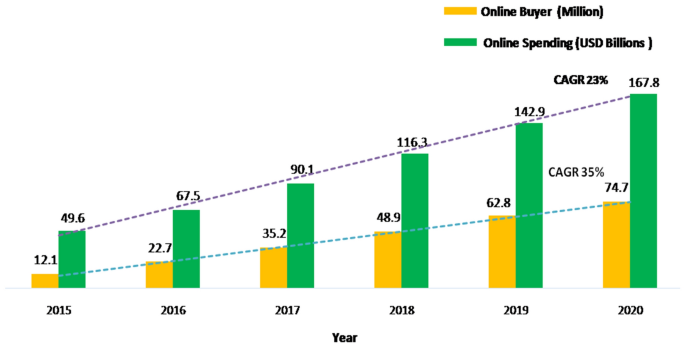

Analysis of different studies on the growth of e-commerce in India shows that while retail spending has grown by a CAGR of 22.52% during 2015–2020, online buyers have climbed by a CAGR of 35.44% during the same period (Fig. 4 ). The government’s Digital India drive beginning 1 July 2015-surge using mobile wallets like Paytm, Ola Money, Mobiwik, BHIM etc., and the declaration of demonetisation on 9 November 2016 appears to be the prime reasons for such a vast growth in the country’s e-commerce industry. The Times of India (2020 October 12), a daily leading Indian newspaper, reported that India's increase in digital payments was at a CAGR of 55.1% from March 2016 to March 2020, jumping from US$ 73,90 million to 470.40, reflecting the country's positive policy environment and preparedness for the digital economy. The government's policy objective is to promote a safe, secure, sound and efficient payment system; hence, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the national financial and fiscal regulating authority, attempts to ensure security and increase customer trust in digital payments (RBI, 2020 ).

Source: Data compiled from https://www.ibef.org/news/vision-of-a-new-india-US$-5-trillion-economy , http://www.ficci.in/ficci-in-news-page.asp?nid=19630 , https://www.pwc.in/research-insights/2018/propelling-india-towards-global-leadership-in-e-commerce.html , https://www.forrester.com/data/forecastview/reports# , Accessed 12 October 2020

E-Commerce growth in India during 2015–2020.

The massive growth of e-commerce in countries worldwide, especially in India, has prompted an examination of the legal structure regulating online consumer protection.

Literature Review and Research Gap

Theoretical framework.

Generally speaking, customers, as treated inferior to their contracting partners, need protection (Daniel, 2005 ). Therefore, due to low bargaining power, it is agreed that their interests need to be secured. The ‘inequality of negotiating power’ theory emphasises the consumer's economically weaker status than suppliers (Haupt, 2003 ; Liyang, 2019 ; Porter, 1979 ). The ‘inequality in bargaining power’ principle emphasises the customer's economically inferior position to suppliers (Haupt, 2003 ). The ‘exploitation theory’ also supports a similar view to the ‘weaker party’ argument. According to this theory, for two reasons, consumers need protection: first, consumers have little choice but to buy and contract on the terms set by increasingly large and powerful businesses; second, companies can manipulate significant discrepancies in knowledge and complexity in their favour (Cockshott & Dieterich, 2011 ). However, a researcher such as Ruhl ( 2011 ) believed that this conventional theoretical claim about defining the customer as the weaker party is no longer valid in modern times. The logic was that the exploitation theory did not take into account competition between firms. Through competition from other businesses, any negotiating power that companies have vis-a-vis clients is minimal. The study, therefore, considers that the ‘economic theory’ is the suitable theoretical rationale for consumer protection today.

The principle of ‘economic philosophy’ focuses primarily on promoting economic productivity and preserving wealth as a benefit (Siciliani et al., 2019 ). As such, the contract law had to change a great deal to deal with modern-age consumer transactions where there is no delay between agreement and outcomes (McCoubrey & White, 1999 ). Thus, the ‘economic theory’ justifies the flow of goods and services through electronic transactions since online markets' versatility and rewards are greater than those of face-to-face transactions. The further argument suggests that a robust consumer protection framework can provide an impetus for the growth of reliability and trust in electronic commerce. The ‘incentive theory’ works based on that argument to describe consumer protection in electronic transactions (McCoubrey & White, 1999 ).

Online shopping needs greater trust than purchasing offline (Nielsen, 2018 ). From the viewpoint of ‘behavioural economics, trust (faith/confidence) has long been considered a trigger for buyer–seller transactions that can provide high standards of fulfilling trade relationships for customers (Pavlou, 2003 ). Pavlou ( 2003 ) supports the logical reasoning of Lee and Turban ( 2001 ) that the role of trust is of fundamental importance in adequately capturing e-commerce customer behaviour. The study by O'Hara ( 2005 ) also suggests a relationship between law and trust (belief/faith), referred to as ‘safety net evaluation’, suggesting that law may play a role in building trust between two parties. However, with cross-border transactions, the constraint of establishing adequate online trust increases, especially if one of the parties to the transaction comes from another jurisdiction with a high incidence of counterfeits or a weak rule of law (Loannis et al., 2019 ). Thus, the law promotes the parties' ability to enter into a contractual obligation to the extent that it works to reduce a contractual relationship's insecurity. The present research uses the idea of trust (faith/belief/confidence) as another theoretical context in line with ‘behavioural economics’.

As a focal point in e-commerce, trust refers to a party's ability to be vulnerable to another party's actions; the trustor, with its involvement in networking, sees trust in the form of risk-taking activity (Mayer et al., 1995 ; Helge et al., 2020 ). Lack of confidence could result in weak contracts, expensive legal protections, sales loss and business failure. Therefore, trust plays a crucial role in serving customers transcend the perceived risk of doing business online and in helping them become susceptible, actual or imaginary, to those inherent e-business risks. While mutual benefit is usually the reason behind a dealing/transaction, trust is the insurance or chance that the customer can receive that profit (Cazier, 2007 ). The level of trust can be low or high. Low risk-taking behaviour leads to lower trustor engagement, whereas high risk-taking participation leads to higher trustor engagement (Helge et al., 2020 ). The theory of trust propounded by (Mayer et al., 1995 ) suggests that trust formation depends on three components, viz. ability, benevolence, and integrity (ABI model). From the analysis of the previous studies (Mayer et al., 1995 ; Cazier, 2007 ; Helge et al., 2020 ), the following dimensions of the ABI model emerge:

Precisely, ability, benevolence and integrity have a direct influence on the trust of e-commerce customers.

Gaining the trust of consumers and developing a relationship has become more challenging for e-businesses. The primary reasons are weak online security, lack of effectiveness of the electronic payment system, lack of effective marketing program, delay in delivery, low quality of goods and services, and ineffective return policy (Kamari & Kamari, 2012 ; Mangiaracina & Perego, 2009 ). These weaknesses adversely impact business operations profoundly later. Among the challenges that are the reasons for the distrust of customers and downsides of e-commerce is that the online payment mechanism is widely insecure. The lack of trust in electronic payment is the one that impacts negatively on the e-commerce industry, and this issue is still prevalent (Mangiaracina & Perego, 2009 ). The revelation of a recent study (Orendorff, 2019 ) and survey results Footnote 9 on trust-building, particularly about the method of payment, preferred language and data protection, is fascinating. The mode of payment is another matter of trust-building. Today’s customers wish to shop in their local currency seamlessly. In an online shoppers’ survey of 30,000 respondents in 2019, about 92% of customers preferred to purchase in their local currency, and 33% abandoned a buy if pricing was listed in US$ only (Orendorff, 2019 ). Airbnb, an online accommodation booking e-business that began operations in 2009, has expanded and spread its wings globally as of September 2020-over 220 countries and 100 k + cities serving 7 + billion customers (guests) with local currency payment options. Footnote 10

Common Sense Advisory Survey Footnote 11 -Nov. 2019-Feb. 2020 with 8709 online shoppers (B2C) in 29 countries, reported that 75% of them preferred to purchase products if the information was in their native language. About 60% confirmed that they rarely/never bought from an English-only website because they can’t read. Similarly, its survey of 956 business people (B2B) moved in a similar direction. Whether it is B2B or B2C customers, they wanted to go beyond Google translator-this is about language being a front-line issue making or breaking global sales. Leading Indian e-commerce companies like Amazon Footnote 12 and Flipkart Footnote 13 have started capturing the subsequent 100 million users by providing text and voice-based consumer support in vernacular languages. These observations suggest trust in information that the customers can rely upon for a successful transaction.

Data protection is probably the most severe risk of e-commerce. The marketplaces witness so many violations that it often seems that everyone gets hacked, which makes it a real challenge to guarantee that your store is safe and secure. For e-commerce firms, preserving the data is a considerable expense; it points a finger to maintaining the safety and security of the e-commerce consumers’ data privacy in compliance with General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) across countries. Footnote 14

PwC’s Global Consumer Insight Survey 2020 reports that while customers’ buying habits would become more volatile post-COVID 19, consumers’ experience requires safety, accessibility, and digital engagement would be robust and diversified. Footnote 15 The report reveals that the COVID-19 outbreak pushed the popularity of mobile shopping. Online grocery shopping (including phone use) has increased by nearly 63% post-COVID than before social distancing execution and is likely to increase to 86% until its removal. Knowing the speed of market change will place companies in a position to handle the disruption-74% of the work is from home, at least for the time being. Again, the trend applies to consumers’ and businesses’ confidence/trust-building. The safety and security of customers or consumer protection are of paramount importance.

Given the rationale above, the doctrine of low bargaining power, exploitation theory and the economic approach provides the theoretical justification for consumer protection. Economic theory also justifies electronic transactions and e-commerce operations as instruments for optimising income. The trust theory based on behavioural economic conception also builds up the relationship between the law and customer trust and thus increases confidence in the online market. These premises form the basis for this research.

Need and Instruments for Online Consumer Protection