Write an Error-free Research Protocol As Recommended by WHO: 21 Elements You Shouldn’t Miss!

Principal Investigator: Did you draft the research protocol?

Student: Not yet. I have too many questions about it. Why is it important to write a research protocol? Is it similar to research proposal? What should I include in it? How should I structure it? Is there a specific format?

Researchers at an early stage fall short in understanding the purpose and importance of some supplementary documents, let alone how to write them. Let’s better your understanding of writing an acceptance-worthy research protocol.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Protocol?

The research protocol is a document that describes the background, rationale, objective(s), design, methodology, statistical considerations and organization of a clinical trial. It is a document that outlines the clinical research study plan. Furthermore, the research protocol should be designed to provide a satisfactory answer to the research question. The protocol in effect is the cookbook for conducting your study

Why Is Research Protocol Important?

In clinical research, the research protocol is of paramount importance. It forms the basis of a clinical investigation. It ensures the safety of the clinical trial subjects and integrity of the data collected. Serving as a binding document, the research protocol states what you are—and you are not—allowed to study as part of the trial. Furthermore, it is also considered to be the most important document in your application with your Institution’s Review Board (IRB).

It is written with the contributions and inputs from a medical expert, a statistician, pharmacokinetics expert, the clinical research coordinator, and the project manager to ensure all aspects of the study are covered in the final document.

Is Research Protocol Same As Research Proposal?

Often misinterpreted, research protocol is not similar to research proposal. Here are some significant points of difference between a research protocol and a research proposal:

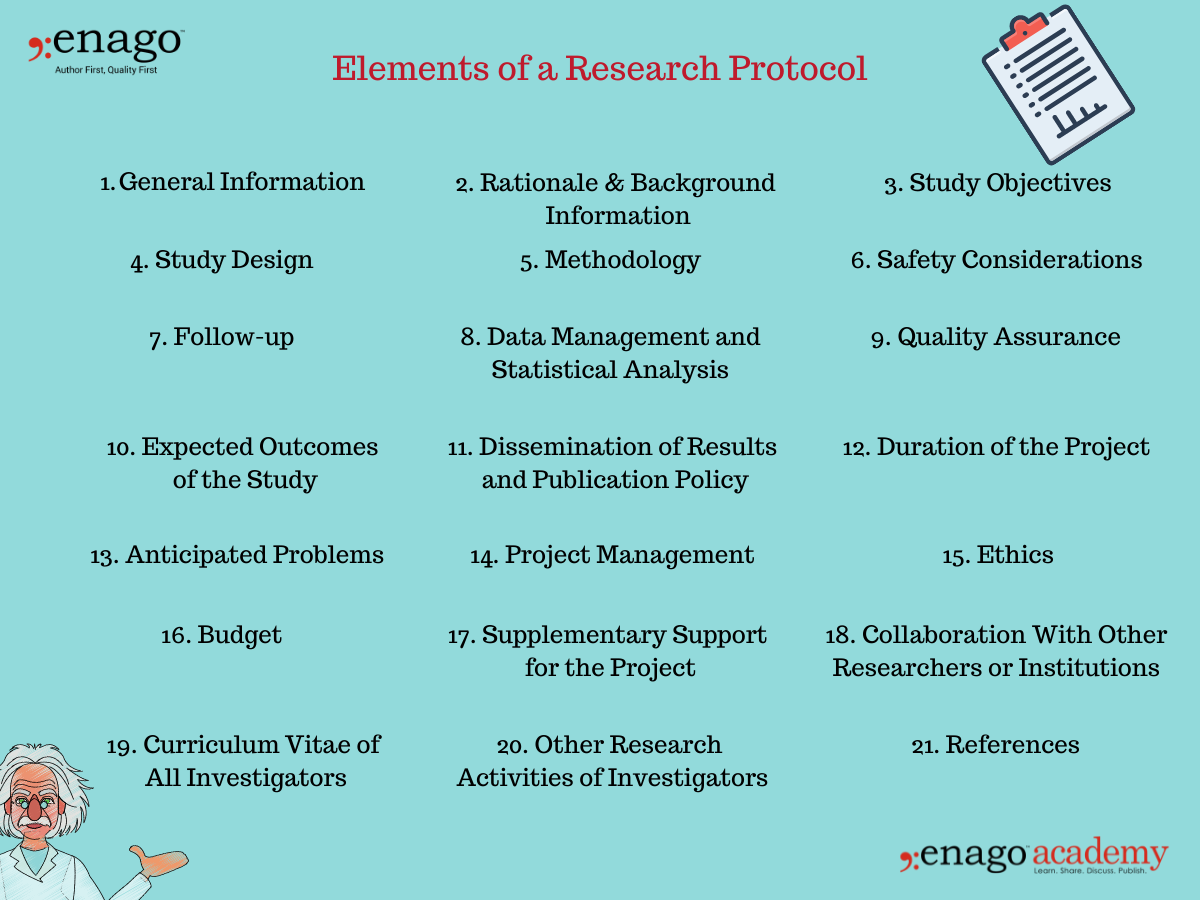

What Are the Elements/Sections of a Research Protocol?

According to Good Clinical Practice guidelines laid by WHO, a research protocol should include the following:

1. General Information

- Protocol title, protocol identifying number (if any), and date.

- Name and address of the funder.

- Name(s) and contact details of the investigator(s) responsible for conducting the research, the research site(s).

- Responsibilities of each investigator.

- Name(s) and address(es) of the clinical laboratory(ies), other medical and/or technical department(s) and/or institutions involved in the research.

2. Rationale & Background Information

- The rationale and background information provides specific reasons for conducting the research in light of pertinent knowledge about the research topic.

- It is a statement that includes the problem that is the basis of the project, the cause of the research problem, and its possible solutions.

- It should be supported with a brief description of the most relevant literatures published on the research topic.

3. Study Objectives

- The study objectives mentioned in the research proposal states what the investigators hope to accomplish. The research is planned based on this section.

- The research proposal objectives should be simple, clear, specific, and stated prior to conducting the research.

- It could be divided into primary and secondary objectives based on their relativity to the research problem and its solution.

4. Study Design

- The study design justifies the scientific integrity and credibility of the research study.

- The study design should include information on the type of study, the research population or the sampling frame, participation criteria (inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal), and the expected duration of the study.

5. Methodology

- The methodology section is the most critical section of the research protocol.

- It should include detailed information on the interventions to be made, procedures to be used, measurements to be taken, observations to be made, laboratory investigations to be done, etc.

- The methodology should be standardized and clearly defined if multiple sites are engaged in a specified protocol.

6. Safety Considerations

- The safety of participants is a top-tier priority while conducting clinical research .

- Safety aspects of the research should be scrutinized and provided in the research protocol.

7. Follow-up

- The research protocol clearly indicate of what follow up will be provided to the participating subjects.

- It must also include the duration of the follow-up.

8. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

- The research protocol should include information on how the data will be managed, including data handling and coding for computer analysis, monitoring and verification.

- It should clearly outline the statistical methods proposed to be used for the analysis of data.

- For qualitative approaches, specify in detail how the data will be analysed.

9. Quality Assurance

- The research protocol should clearly describe the quality control and quality assurance system.

- These include GCP, follow up by clinical monitors, DSMB, data management, etc.

10. Expected Outcomes of the Study

- This section indicates how the study will contribute to the advancement of current knowledge, how the results will be utilized beyond publications.

- It must mention how the study will affect health care, health systems, or health policies.

11. Dissemination of Results and Publication Policy

- The research protocol should specify not only how the results will be disseminated in the scientific media, but also to the community and/or the participants, the policy makers, etc.

- The publication policy should be clearly discussed as to who will be mentioned as contributors, who will be acknowledged, etc.

12. Duration of the Project

- The protocol should clearly mention the time likely to be taken for completion of each phase of the project.

- Furthermore a detailed timeline for each activity to be undertaken should also be provided.

13. Anticipated Problems

- The investigators may face some difficulties while conducting the clinical research. This section must include all anticipated problems in successfully completing their projects.

- Furthermore, it should also provide possible solutions to deal with these difficulties.

14. Project Management

- This section includes detailed specifications of the role and responsibility of each investigator of the team.

- Everyone involved in the research project must be mentioned here along with the specific duties they have performed in completing the research.

- The research protocol should also describe the ethical considerations relating to the study.

- It should not only be limited to providing ethics approval, but also the issues that are likely to raise ethical concerns.

- Additionally, the ethics section must also describe how the investigator(s) plan to obtain informed consent from the research participants.

- This section should include a detailed commodity-wise and service-wise breakdown of the requested funds.

- It should also include justification of utilization of each listed item.

17. Supplementary Support for the Project

- This section should include information about the received funding and other anticipated funding for the specific project.

18. Collaboration With Other Researchers or Institutions

- Every researcher or institute that has been a part of the research project must be mentioned in detail in this section of the research protocol.

19. Curriculum Vitae of All Investigators

- The CVs of the principal investigator along with all the co-investigators should be attached with the research protocol.

- Ideally, each CV should be limited to one page only, unless a full-length CV is requested.

20. Other Research Activities of Investigators

- A list of all current research projects being conducted by all investigators must be listed here.

21. References

- All relevant references should be mentioned and cited accurately in this section to avoid plagiarism.

How Do You Write a Research Protocol? (Research Protocol Example)

Main Investigator

Number of Involved Centers (for multi-centric studies)

Indicate the reference center

Title of the Study

Protocol ID (acronym)

Keywords (up to 7 specific keywords)

Study Design

Mono-centric/multi-centric

Perspective/retrospective

Controlled/uncontrolled

Open-label/single-blinded or double-blinded

Randomized/non-randomized

n parallel branches/n overlapped branches

Experimental/observational

Endpoints (main primary and secondary endpoints to be listed)

Expected Results

Analyzed Criteria

Main variables/endpoints of the primary analysis

Main variables/endpoints of the secondary analysis

Safety variables

Health Economy (if applicable)

Visits and Examinations

Therapeutic plan and goals

Visits/controls schedule (also with graphics)

Comparison to treatment products (if applicable)

Dose and dosage for the study duration (if applicable)

Formulation and power of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Method of administration of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Informed Consent

Study Population

Short description of the main inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal criteria

Sample Size

Estimated Duration of the Study

Safety Advisory

Classification Needed

Requested Funds

Additional Features (based on study objectives)

Click Here to Download the Research Protocol Example/Template

Be prepared to conduct your clinical research by writing a detailed research protocol. It is as easy as mentioned in this article. Follow the aforementioned path and write an impactful research protocol. All the best!

Clear as template! Please, I need your help to shape me an authentic PROTOCOL RESEARCH on this theme: Using the competency-based approach to foster EFL post beginner learners’ writing ability: the case of Benin context. I’m about to start studies for a master degree. Please help! Thanks for your collaboration. God bless.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, contents of a research study protocol, conflict of interest statement, how to write a research study protocol.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julien Al Shakarchi, How to write a research study protocol, Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies , Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, snab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsprm/snab008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. Many funders such as the NHS Health Research Authority encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will describe how to write a research study protocol.

A study protocol is an essential part of a research project. It describes the study in detail to allow all members of the team to know and adhere to the steps of the methodology. Most funders, such as the NHS Health Research Authority in the United Kingdom, encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology, help with publication of the study and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will explain how to write a research protocol by describing what should be included.

Introduction

The introduction is vital in setting the need for the planned research and the context of the current evidence. It should be supported by a background to the topic with appropriate references to the literature. A thorough review of the available evidence is expected to document the need for the planned research. This should be followed by a brief description of the study and the target population. A clear explanation for the rationale of the project is also expected to describe the research question and justify the need of the study.

Methods and analysis

A suitable study design and methodology should be chosen to reflect the aims of the research. This section should explain the study design: single centre or multicentre, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, randomised or not, and observational or experimental. Efforts should be made to explain why that particular design has been chosen. The studied population should be clearly defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria will define the characteristics of the population the study is proposing to investigate and therefore outline the applicability to the reader. The size of the sample should be calculated with a power calculation if possible.

The protocol should describe the screening process about how, when and where patients will be recruited in the process. In the setting of a multicentre study, each participating unit should adhere to the same recruiting model or the differences should be described in the protocol. Informed consent must be obtained prior to any individual participating in the study. The protocol should fully describe the process of gaining informed consent that should include a patient information sheet and assessment of his or her capacity.

The intervention should be described in sufficient detail to allow an external individual or group to replicate the study. The differences in any changes of routine care should be explained. The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly defined and an explanation of their clinical relevance is recommended. Data collection methods should be described in detail as well as where the data will be kept secured. Analysis of the data should be explained with clear statistical methods. There should also be plans on how any reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct will be reported, collected and managed.

Ethics and dissemination

A clear explanation of the risk and benefits to the participants should be included as well as addressing any specific ethical considerations. The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

It is essential to comment on how personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained in order to protect confidentiality. This part of the protocol should also state who owns the data arising from the study and for how long the data will be stored. It should explain that on completion of the study, the data will be analysed and a final study report will be written. We would advise to explain if there are any plans to notify the participants of the outcome of the study, either by provision of the publication or via another form of communication.

The authorship of any publication should have transparent and fair criteria, which should be described in this section of the protocol. By doing so, it will resolve any issues arising at the publication stage.

Funding statement

It is important to explain who are the sponsors and funders of the study. It should clarify the involvement and potential influence of any party. The sponsor is defined as the institution or organisation assuming overall responsibility for the study. Identification of the study sponsor provides transparency and accountability. The protocol should explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of any funder(s) in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and dissemination of results. Any competing interests of the investigators should also be stated in this section.

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. It should be written in detail and researchers should aim to publish their study protocols as it is encouraged by many funders. The spirit 2013 statement provides a useful checklist on what should be included in a research protocol [ 1 ]. In this paper, we have explained a straightforward approach to writing a research study protocol.

None declared.

Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , Altman DG , Mann H , Berlin J , et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013 ; 346 : e7586 .

Google Scholar

- conflict of interest

- national health service (uk)

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- JSPRM Twitter

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-616X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and JSCR Publishing Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing the protocol

A protocol should be prepared before a review is started and used as a guide to carry out the review.

The aim of the protocol is to minimise bias by having pre-defined eligibility criteria of what will , and will not , be included in the review.

The research protocol is a planning document that will:

- describe the rationale for the review

- set out the review objectives

- detail the sources and search strategy used to locate studies

- d etail how studies wil l be selected based on the defined eligibility criteria for the inclusion/exclusion of studies

- detail how the studies will be critically analysed

- provide the basis of how the findings will be reported.

The protocol is developed in conjunction with determining search terms.

A protocol promotes research integrity, accountability, and transparency of the completed review.

Best Practice Tip

It is recommended that you use a standard such as the 27 item PRISMA checklist to develop your protocol. This document will then serve well as a guide to what should be included when the findings of the systematic review are reported.

What is PRISMA? PRISMA is the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Test your knowledge

Research and Writing Skills for Academic and Graduate Researchers Copyright © 2022 by RMIT University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Published peer-reviewed protocols

A research protocol is a detailed study design or set of instructions for carrying out a specific experimental process or procedure.

Benefits of Published Protocols

Peer-review of protocols supports rigorous, high-quality research, while publication increases discoverability, supports reproducibility, and recognizes the importance of the scientific work. Articles published under an Open Access license are freely available for anyone, anywhere in the world to discover, read, distribute or reuse at no cost. For that reason, Open Access articles are more widely read than subscription research.

Improve your approach Expert peer review feedback can help to refine and shape your protocol, promoting usability and efficiency.

Earn readers’ trust It’s difficult to reproduce results—or even confirm the question a study is designed to answer—based on a research article alone. Protocols show that you did what you set out to do, and how you went about it.

Expand your publication record Protocols take time and thought to develop; claim academic credit for your efforts through formal publication.

Help you field move faster Published protocols are discoverable and accessible, enabling other researchers to adapt and build upon your accomplishments.

Discover how publishing protocols helps increase research visibility

PLOS authors share how they have created more visibility and impact for their research with published Lab Protocols.

How reproducible is your research?

Take our self-assessment to see your reproducibility score.

Read more about published protocols

When it comes to methods sharing, Lab Protocols at PLOS ONE offer researchers the best of both worlds: a platform specifically designed for step-by-step protocols, and a peer-reviewed publication in a well-regarded journal.

Our ongoing partnership with protocols.io led to a new and exciting PLOS ONE article type, Lab Protocols, which offers a new avenue to share research in-line with the principles of Open Science.

PLOS ONE’s array of publication options that push the boundaries of Open Science continues to expand. We’re happy to announce two new article types that improve reproducibility and transparency, and allow researchers to receive credit for their contributions to study design: Lab Protocols and Study Protocols.

Lab Protocols

PLOS ONE is committed to pushing the boundaries of Open Science by improving the reproducibility and transparency of scientific research. In collaboration with protocols.io, Lab Protocols offer authors the opportunity to share their peer reviewed step-by-step protocols with the community whilst receiving credit for their contributions.

Discover your options for publishing protocols at PLOS

You devote countless hours to the development of a study design or research method. Each deserves more than a footnote. We invite you to submit your protocols for peer review and formal publication. Choose the publication option that best fits your research needs.

Study Protocols

Study protocols describe detailed plans and proposals for research projects that have not yet generated results. They consist of a single article in PLOS ONE that can be referenced in future papers.

Already common in the health sciences, sharing a study’s design and analysis plan before the research is carried out improves transparency and coordinates effort.

Lab protocols describe reusable methodologies in all fields of study. They consist of two interlinked components:

- A step-by-step protocol posted to protocols.io , with access to specialized tools for communicating technical details, including reagents, measurements, and formulae.

- A peer-reviewed PLOS ONE article contextualizing the protocol, with sections discussing applications, limitations, expected results and sample datasets.

Learn more about the benefits of Open Science. Open Science

- IRB-HSR Home

- Getting Started

- Protocol Submission Process

- Submission Types

- Protocol Builder

- Reliance on the IRB-HSR to serve as the Single IRB (sIRB) of record

- Reliance on a Non-IRB-HSR to serve as the Single IRB (sIRB) of Record

- Clinical Research Connect

- CITI Training

- Education Calendar

- IRB-HSR Learning Shots

- Virginia IRB Consortium

- HRPP Education & Training

- Investigator Resources

- IRB Online/ Protocol Builder

- Board Membership Lists

- Calendars & Deadlines

- For IRB Staff

- Determining Human Subjects Research

- Determining HSR or SBS

- Ethical Principles

- HRPP Standard Operating Procedures

- Federal Regulations

- For Research Participants

- Partner Offices

- IRB-HSR PAM & Ed

- EMERGENCY USE

- UVA Non-Human Subject Research Online Tool

Protocol Elements

The following outlines the basic elements of a research protocol. The IRB templates will provide more specific requirements.

Table of Contents

Introduction/abstract, objectives and rationale, methods and procedures, subject population selection and inclusion/exclusion criteria, risks and benefits, provisions for treatment of adverse events, subject recruitment, review preparatory to research and recruitment.

- Subject Compensation/Reimbursement

Study Management and Personnel

- Confidentiality and Data Storage

Data Analysis and Evaluation Techniques

- Bibliography

Protocols coming from industry or protocols for multi-site studies typically include a table of contents. The UVA IRB protocol templates created by Protocol Builder do not require a table of contents.

The introduction should indicate the specific reasons or rationale for performing the study, the hypotheses, study design ( e.g. , record review, questionnaire, specimen collection, interview, prospective evaluation of a drug or device), and an overview of the literature on comparable studies. If applicable, Principal Investigators should briefly describe the intervention, treatment, drugs, or devices to be used.

A hypothesis is a tentative statement that proposes a possible explanation to some phenomenon or event. A useful hypothesis is a testable statement which may include a prediction. The key word is testable. That is, you will perform a test of how two variables might be related. This is when you are doing a real experiment. You are testing variables.

The objectives of the study should be:

- based on the research question(s);

- limited in scope and number;

- based on specific quantifiable endpoints; and

- congruent with the study design.

The scientific rationale should provide enough information to answer the question, "Why should this study be done?" It should contain a referenced review of the literature specifically pertaining to the reasons for the current study and previous investigations that lead the investigator to pose the specific question. In addition, it should include a justification of the research design and the use of any placebos.

This section describes the study design, the study population, the research intervention, if applicable, sample selection, and an appropriate analytic plan. Specific recommendations for presenting study methods are presented below.

For Clinical Research

The Methods section for clinical study protocols evaluating a drug, device or a treatment modality should explain the treatment plan. Baseline diagnostic tests, initial laboratory assessments for determining eligibility of a potential subject to enter the trial, and any procedures, physical exams, tests, interviews, videotapes, and the amount of time the subject will be involved in the study should be detailed. Principal Investigators should consider including a table or schematic of study events by visit to clarify for the IRB reviewers what tests, procedures, etc. will be done and when they will be done.

Principal Investigators should make clear which interventions and procedures are standard clinical care for the subject's condition and which are experimental or, if not experimental, are being performed solely as a result of the subject's participation in the clinical research.

Principal Investigators should discuss (1) the procedures for monitoring the subject's condition and (2) reasons for dropping any participant from the study (e.g. , relapse, lack of subject compliance).

Subject Selection and Inclusion Criteria

UVA recognizes its responsibility to create an environment in which the equitable selection of research participants is fostered. Therefore, Principal Investigators must provide the IRB the details on the proposed involvement of humans in the research. Principal Investigators must describe the number of subjects and observations necessary to obtain statistically valid results. The type of study design and the procedures for randomization, blinding, crossover, controls (positive and negative), and, washout, as applicable, must all be explained. Principal Investigators must specify the:

- characteristics of the subject population,

- number of subjects to be enrolled (e.g. sign consent)

- number of subjects (e.g. the number of subjects required to obtain statistically valid results),

- age ranges of subjects,

- health statuses of subjects, and

- the gender composition and racial/ethnic composition of the subject population. If ethnic, racial and gender estimates are not specified, the Principal Investigator must provide a clear rationale for exclusion of this information.

Methods for subject screening and eligibility should be described in detail. Screening for enrollment into a study entails careful evaluation of the potential subject on the basis of the criteria that are stated in the protocol.

Subject eligibility criteria should be listed, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and other inclusion and exclusion criteria. If a potential subject conforms to those preliminary criteria, more specific screening evaluations can be performed, such as the taking of a medical history, a physical examination, and clinical laboratory tests, such as a complete blood count with differential; blood chemistry analysis (e.g. electrolytes, cholesterol, and triglycerides, urinalysis, an electrocardiogram, and blood pressure.)

The protocol should state the limits of acceptability for the aforementioned evaluations; for example, it should define a normal range for the clinical laboratory tests and include appropriate statements about the interpretation of those tests (e.g. statements on borderline values).

If the proposed study may include a vulnerable or special subject population, investigators shall refer to the additional requirements for these subject populations.

Subject Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria may include such things as severity of disease, mental incompetence, use of other medication concomitantly, or presence of other diseases. Principal Investigators must explain and justify the exclusion of women and/or minority groups and children.

Women and Minorities

All research involving human subjects should be designed and conducted to include members of both genders and members of minority groups, unless a clear and compelling rationale and justification establishes that such inclusion is inappropriate with respect to the health of the subjects or the purpose of the research.

The NIH acknowledges clear scientific and public health reasons for specifically including members of minority groups in studies of health problems that disproportionately affect U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations. In attempting to include minority groups, Principal Investigators should assess the theoretical and/or scientific connections between race/ethnicity in the topic of study. FDA Guidelines require that subjects recruited to trials reflect the population that will receive the drug/therapeutic intervention when it is marketed or approved for administration. FDA Guidelines also recommend that "representatives of both genders be included in clinical trials in numbers adequate to allow detection of clinically significant gender related differences in drug response."

For NIH-defined Phase I and II clinical trials, the systematic inclusion and reporting of information on women and minorities and minority subpopulations is generally required to increase the scientific base of knowledge about them. For Phase III clinical trials, the design of the trials must reflect the current state of knowledge about any clinically important gender and/or race/ethnicity differences in the response to the intervention. Evidence may include data from prior animal studies, clinical observations, metabolic studies, genetic studies, pharmacology studies, and observational, epidemiologic and other relevant studies. The nature of the evidence should be used to determine the extent to which women, men and members of minority groups and their subpopulations must be included. In addition, national statistics on the disease, disorder or condition under study and national population statistics should be used in designing Phase III clinical trials.

Studies should employ a design with gender, racial and/or age representations appropriate to the known incidence/prevalence of the disease or condition being studied. If subjects of a certain gender, race or age group are to be excluded and it can reasonably be assumed that the drug or therapeutic intervention when approved will be administered to both sexes and all age and racial groups, the investigator must clearly explain and justify such exclusion.

It is not expected that every minority group and subpopulation will be included in each study; however, broad representation and diversity are the goals, even if multiple clinics and sites are needed to accomplish it.

Minority groups recognized by NIH include:

- American Indian or Alaskan Native (person having origins in any of the original peoples of North America , and who maintain cultural identification through tribal affiliation or community recognition);

- (ii) Asian or Pacific Islander (person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent or the Pacific Islands and Samoa);

- (iii) Black, not of Hispanic origin (a person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa ); and

- (iv) Hispanic (a person or Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race).

Each minority group may contain subpopulations which are delimited by geographic origins, national origins and/or cultural differences. The minority group or subpopulation to which an individual belongs is determined by self-reporting.

Subject Withdrawal Criteria

A protocol shall include subject withdrawal criteria and procedures specifying

- when and how to withdraw subjects from the trial,

- the type and timing of data to be collected for withdrawn subjects,

- whether and how subjects will be replaced, and

- the follow-up for such subjects.

If data collected for research purposes has clinical significance for individuals in the study but the data will be analyzed at another institution, resulting in substantial delay in receipt of important clinical findings affecting the subject's welfare, Principal Investigators should specify how they intend to monitor the subject locally.

Background

Per DHHS and FDA regulations (45 CFR 46.111 and 21 CFR 56.111) two of the required criteria for granting IRB approval of the research are:

- Risks to subjects are minimized by using procedures which are consistent with sound research design and which do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk, and whenever appropriate, by using procedures already being performed on the subjects for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

- Risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result. In evaluating risks and benefits, the IRB will consider only those risks and benefits that may result from the research, as distinguished from risks and benefits of therapies subjects would receive even if not participating in the research.

Definitions

- Benefit: A valued or desired outcome; an advantage.

- Risk: The probability of harm or injury (physical, psychological, social, or economic) occurring as a result of participation in a research study. Both the probability and magnitude of possible harm may vary from minimal to significant. Federal regulations define only "minimal risk."

- Minimal Risk: A risk is minimal where the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the proposed research are not greater, in and of themselves, than those ordinarily encountered in daily lives of the general population or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests.

- Minimal Risk for Research involving Prisoners: The definition of minimal risk for research involving prisoners differs somewhat from that given for non-institutionalized adults. Minimal risk is in this case is defined as, "the probability and magnitude of physical or psychological harm that is normally encountered in the daily lives , or in the routine medical, dental or psychological examinations of healthy persons ."

Overview of Risks and Benefits

There are two sources of confusion in the assessment of risks and benefits. One arises from the language employed in the discussion:

- "Risk" is a word expressing probabilities;

- "Benefits" is a word expressing a fact or state of affairs.

It is more accurate to speak as if both were in the realm of probability: i.e., risks and expected or anticipated benefits.

Confusion also may arise because "risks" can refer to two quite different things:

- those chances that specific individuals are willing to undertake for some desired goal; or

- the conditions that make a situation harmful to a subject.

Researchers should provide detailed information in the IRB protocol about potential risks and benefits associated with the research, and provide information about the probability, magnitude and potential harms associated with each risk.

Risk/Benefit Assessment

The IRB is responsible for evaluating the potential risks and weighing the probability of the risk occurring and the magnitude of harm that may result. It must then judge whether the anticipated benefit, either of new knowledge or of improved health for the research subjects, justifies inviting any person to undertake the risks. The IRB cannot approve research in which the risks are judged unreasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits. The IRB must:

- Identify the risks associated with the research, as distinguished from the risks of therapies the subjects would receive even if not participating in research;

- Determine that the risks will be minimized to the extent possible [see below];

- Identify the probable benefits to be derived from the research;

- Determine that the risks are reasonable in relation to be benefits to subjects, if any, and the importance of the knowledge to be gained; and

- Assure that potential subjects will be provided with an accurate and fair description (during consent) of the risks or discomforts and the anticipated benefits.

Types of Risk to Research Subjects

The risks to which research subjects may be exposed have been classified as physical, psychological, social, and economic.

Physical Harms: Medical research often involves exposure to minor pain, discomfort, or injury from invasive medical procedures, or harm from possible side effects of drugs. All of these should be considered "risks" for purposes of IRB review. Some of the adverse effects that result from medical procedures or drugs can be permanent, but most are transient. Procedures commonly used in medical research usually result in no more than minor discomfort (e.g., temporary dizziness, the pain associated with venipuncture). Some medical research is designed only to measure more carefully the effects of therapeutic or diagnostic procedures applied in the course of caring for an illness. Such research may not entail any significant risks beyond those presented by medically indicated interventions. On the other hand, research designed to evaluate new drugs or procedures may present more than minimal risk, and, on occasion, can cause serious or disabling injuries. Psychological Harms: Participation in research may result in undesired changes in thought processes and emotion (e.g., episodes of depression, confusion, or hallucination resulting from drugs, feelings of stress, guilt, and loss of self-esteem). These changes may be transitory, recurrent, or permanent. Most psychological risks are minimal or transitory, but some research has the potential for causing serious psychological harm. Stress and feelings of guilt or embarrassment may arise simply from thinking or talking about one's own behavior or attitudes on sensitive topics such as drug use, sexual preferences, selfishness, and violence. These feelings may be aroused when the subject is being interviewed or filling out a questionnaire. Stress may also be induced when the researchers manipulate the subjects' environment - as when "emergencies" or fake "assaults" are staged to observe how passersby respond. More frequently, however, is the possibility of psychological harm when behavioral research involves an element of deception. Invasion of privacy is a risk of a somewhat different character. In the research context, it usually involves either covert observation or "participant" observation of behavior that the subjects consider private.

The IRB must make two determinations:

- is the invasion of privacy involved acceptable in light of the subjects' reasonable expectations of privacy in the situation under study; and

- is the research question of sufficient importance to justify the intrusion?

The IRB must also consider whether the research design could be modified so that the study can be conducted without invading the privacy of the subjects. Breach of confidentiality is sometimes confused with invasion of privacy, but it is really a different risk. Invasion of privacy concerns access to a person's body or behavior without consent; confidentiality of data concerns safeguarding information that has been given voluntarily by one person to another. Some research requires the use of a subject's hospital, school, or employment records. Access to such records for legitimate research purposes is generally acceptable, as long as the researcher protects the confidentiality of that information. However, it is important to recognize that a breach of confidentiality may result in psychological harm to individuals (in the form of embarrassment, guilt, stress, and so forth) or in social harm (see below). Social and Economic Harms: Some invasions of privacy and breaches of confidentiality may result in embarrassment within one's business or social group, loss of employment, or criminal prosecution. Areas of particular sensitivity are information regarding alcohol or drug abuse, mental illness, illegal activities, and sexual behavior. Some social and behavioral research may yield information about individuals that could "label" or "stigmatize" the subjects. (e.g., as actual or potential delinquents or schizophrenics). Confidentiality safeguards must be strong in these instances. Participation in research may result in additional actual costs to individuals. Any anticipated costs to research participants should be described to prospective subjects during the consent process.

Ways to Minimize Risk

- Provide complete information in the protocol regarding the experimental design and the scientific rationale underlying the proposed research, including the results of previous animal and human studies.

- Assemble a research team with sufficient expertise and experience to conduct the research.

- Ensure that the projected sample size is sufficient to yield useful results.

- Collect data from standard-of-care procedures to avoid unnecessary risk, particularly for invasive or risky procedures (e.g., spinal taps, cardiac catheterization).

- Incorporate adequate safeguards into the research design such as an appropriate data safety monitoring plan, the presence of trained personnel who can respond to emergencies, and procedures to protect the confidentiality of the data (e.g., encryption, codes, and passwords).

Principal Investigators should conduct a detailed and appropriate literature review, and should detail:

- all possible risks to the subject, whether physical, psychological, social, economic, legal, or

- where the research may present a legal risk to subjects through a loss of confidentiality, address the need for a Certificate of Confidentiality .

If other methods of research present fewer risks, Principal Investigators should describe those, if any, that were considered and why they will not be used. Any potential for discomfort associated with any test or procedure performed for research purposes should be noted.

In general, risks to subjects must be minimized by using procedures which are consistent with sound research design and which do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk and whenever appropriate, by using data and procedures already being performed on the subjects for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

For all research involving any risk of physical injury (including any adverse effect affecting the body, such as rashes and infections) these risks must be specified. If there are none, state: "There are no risks of physical injury. However, if there are risks of physical injury, the protocol should state the potential injury, a careful estimate of its probability and severity, and its potential duration and the likelihood of its reversibility.

There should be a statement as to whether these risks are presented by:

- a procedure or modality performed or administered as part of standard care or

- a procedure or modality performed or administered solely as a result of the subjects participation in the research protocol.

Principal Investigators should specify:

- quantities of body fluids or tissues ( e.g. , volume of blood, urine, saliva, number of biopsies),

- the time the subject will have to spend being tested, and

- the duration of the study.

Discussion of the risks should also include the risks of non-treatment. If drugs or medical devices are being used which have known potential adverse side effects Principal Investigators should indicate if side effects are reversible. Risks associated with a drug washout period, non-treatment or discontinuation of active drugs must be addressed by Principal Investigators. Principal Investigators shall include a description of procedures (including confidentiality safeguards) for protecting against or minimizing injuries (physical, psychological and social) and provide an assessment of their likely effectiveness. There should be a clear statement about procedures for early detection of adverse effects and what steps, if any, will be taken to avoid injury to subjects, for example, the subject might be withdrawn from the study or a corrective drug might be administered.

The Principal Investigator should indicate where subjects will be recruited (e.g. in patient unit, walk in clinic, emergency room, ICU, or outside of UVA). The Principal Investigator should also note whether normal controls are to be used and, if applicable, recruitment methods (e.g. advertisements). .

The IRB reviews the information contained in advertisements and other subject recruitment material and the mode of its communication. The IRB also reviews the format of any Internet information and the final copy of printed advertisements to evaluate the relative size of type used and other visual effects.

IRB-HSR review and approval is required prior to initiating research involving health information. Investigators are not authorized to contact potential research subjects identified in reviews preparatory to research unless they are directly responsible for care of the potential subject and entitled to PHI as a result of that duty. All recruitment materials must be approved by the IRB prior to use. Information about recruitment materials, IRB-HSR submission process, and templates are available on the IRB-HSR Website under Subject Selection, Recruitment and Compensation .

Subject Compensation/Reimbursement

It is not uncommon for subjects to be paid for their participation in research, especially in the early phases of investigational drug or device research or in behavioral and epidemiological research which require a significant time commitment on the part of the subject. The investigator should set forth the compensation plan in the protocol. Plans which call for the entire payment being made at the completion of the protocol may appear to be coercive. Subjects may also be reimbursed for out of pocket expenses related to participation (travel costs, parking expenses, child care, etc.) If such monetary compensation or reimbursement is to be offered, investigators should state the amount subjects are to receive. To view additional information on the difference between compensation and reimbursement click on “ More Information ”. Researchers should be aware of the Compensation to Research Trial Participants Procedure from the Office of the Vice President for Research. The procedure requires the researcher to provide justification if compensation cannot be done via the UVA Oracle System or if the researcher is unable to obtain tax information such as name, address, and Social Security number of recipient of compensation. For additional info see: Justification for use of an alternative method of compensation

Justification for not collecting the tax information .

The Principal Investigator should name the professional staff who will be performing the study as sub-investigators, the research study coordinators, and other study support staff. Study staff must complete the UVA required CITI training program. Where specimens or data will be collected and stored, the Principal Investigator should indicate who will be responsible for storage, under what circumstances data or specimens will be released, what future types of research are anticipated using the specimens or data, and what steps will be taken to protect confidentiality (e.g. all identifiers stripped or, if coded, persons with access to code and location of code). Methods for protecting the security of information should be included. If the study is a Phase I or Phase II clinical trial and provides for a Data and Safety Management Board, those provisions should be included in the Data and Safety Monitoring Plan.

In long term studies, study management issues that the Principal Investigator should consider are: the continuity of study personnel; availability of co-investigators; the timing of periodic review of data to assess trends; continuing training for data managers or study personnel to eliminate deviations from the protocol; and the investigator's plan, if any, to "re consent" subjects and obtain authorization over a number of years.

Confidentiality and Data Storage

When appropriate, the subject should be assured that steps will be taken to assure confidentiality. The Principal Investigator should explain how subject confidentiality will be preserved, how data will be kept confidential and used for professional purposes, and whether data will be coded and where the data will be kept ( i.e. , in locked files). This is particularly important in studies in which information will be recorded which, in the view of the subject, is sufficiently sensitive so that he/she would not wish persons other than the investigators to have access to it. The protocol should also address any potential harm resulting. Whatever measures are taken to assure confidentiality should also be discussed in general terms in the consent form. Certain research may qualify for additional privacy protection in the form of a Certificate of Confidentiality (federal funding is not required). Studies that are federally funded and that collect identifiable information are automatically granted a Certificate of Confidentiality by the NIH. Investigators for studies not funded by the federal government may request a Certificate of Confidentiality to be issued by a Federal Agency when research is of a sensitive nature (e.g. involves information pertaining to illegal conduct or relating to the use of alcohol or drugs, sexual attitudes, preferences or practices, mental health, or information potentially damaging to the subject's financial standing, employability or reputation) and the additional protection is judged necessary to achieve the research objectives.

The Principal Investigator should describe the types of analyses to be performed and evaluation techniques (endpoints, pharmacodynamic assessments, outcome measurements, etc.). If the study entails the collection of specimens, the analytical procedure to be followed should be presented and referenced (unless obvious). If a new technique that has not been documented in the literature is to be used, the Principal Investigator should describe the technique or include a statement about the method that will be developed. The Principal Investigator should indicate determinations of response to therapy. These may include laboratory assays, biopsies, bone marrow testing, absence of symptoms, or normal blood levels. The definition of partial response and failure should be included. If the study is designed to evaluate behavior through the use of subjective or objective rating scales, or to study quality of life or activities of daily living, the method of evaluation should be explained with references. The description of the analytical and statistical techniques should be as explicit as possible. All manipulations of the data should be explained, and the statistical methods to be used should be identified. Simple statements about an "appropriate analytical technique" and an "appropriate statistical test" are discouraged; they imply that the investigator has not fully planned the study.

Bibliography

A reasonable list of references directly related to the study should be included.

When additional information is needed to support decisions made by the Principal Investigator, it should be included in an appendix. Typically, appendices include such information as height and weight tables, a description of analytical methodology, calculations, subject screening criteria, subjective and objective rating scales and any supportive literature. Any diagrams for new medical devices or brief reprints from journals might also prove useful.

The Federal Register

The daily journal of the united states government, request access.

Due to aggressive automated scraping of FederalRegister.gov and eCFR.gov, programmatic access to these sites is limited to access to our extensive developer APIs.

If you are human user receiving this message, we can add your IP address to a set of IPs that can access FederalRegister.gov & eCFR.gov; complete the CAPTCHA (bot test) below and click "Request Access". This process will be necessary for each IP address you wish to access the site from, requests are valid for approximately one quarter (three months) after which the process may need to be repeated.

An official website of the United States government.

If you want to request a wider IP range, first request access for your current IP, and then use the "Site Feedback" button found in the lower left-hand side to make the request.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

What is ‘original scholarship’ in the age of AI?

Complex questions, innovative approaches

Early warning sign of extinction?

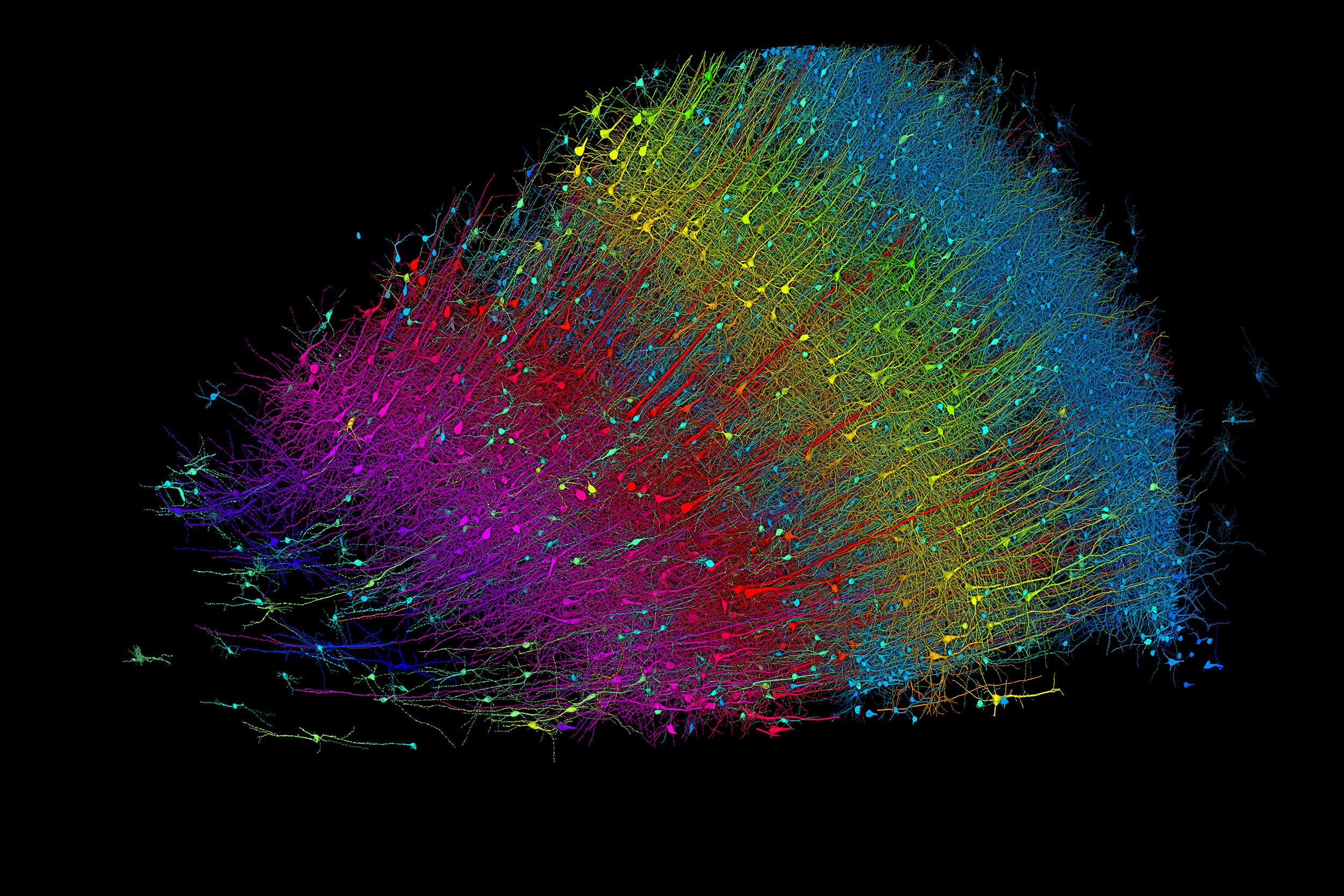

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain.

Six layers of excitatory neurons color-coded by depth.

Credit: Google Research and Lichtman Lab

Anne J. Manning

Harvard Staff Writer

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

A cubic millimeter of brain tissue may not sound like much. But considering that that tiny square contains 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and 150 million synapses, all amounting to 1,400 terabytes of data, Harvard and Google researchers have just accomplished something stupendous.

Led by Jeff Lichtman, the Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and newly appointed dean of science , the Harvard team helped create the largest 3D brain reconstruction to date, showing in vivid detail each cell and its web of connections in a piece of temporal cortex about half the size of a rice grain.

Published in Science, the study is the latest development in a nearly 10-year collaboration with scientists at Google Research, combining Lichtman’s electron microscopy imaging with AI algorithms to color-code and reconstruct the extremely complex wiring of mammal brains. The paper’s three first co-authors are former Harvard postdoc Alexander Shapson-Coe, Michał Januszewski of Google Research, and Harvard postdoc Daniel Berger.

The ultimate goal, supported by the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative , is to create a comprehensive, high-resolution map of a mouse’s neural wiring, which would entail about 1,000 times the amount of data the group just produced from the 1-cubic-millimeter fragment of human cortex.

“The word ‘fragment’ is ironic,” Lichtman said. “A terabyte is, for most people, gigantic, yet a fragment of a human brain — just a minuscule, teeny-weeny little bit of human brain — is still thousands of terabytes.”

Jeff Lichtman.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The latest map contains never-before-seen details of brain structure, including a rare but powerful set of axons connected by up to 50 synapses. The team also noted oddities in the tissue, such as a small number of axons that formed extensive whorls. Because the sample was taken from a patient with epilepsy, the researchers don’t know whether such formations are pathological or simply rare.

Lichtman’s field is connectomics, which seeks to create comprehensive catalogs of brain structure, down to individual cells. Such completed maps would unlock insights into brain function and disease, about which scientists still know very little.

Google’s state-of-the-art AI algorithms allow for reconstruction and mapping of brain tissue in three dimensions. The team has also developed a suite of publicly available tools researchers can use to examine and annotate the connectome.

“Given the enormous investment put into this project, it was important to present the results in a way that anybody else can now go and benefit from them,” said Google collaborator Viren Jain.

Next the team will tackle the mouse hippocampal formation, which is important to neuroscience for its role in memory and neurological disease.

Share this article

You might like.

Symposium considers how technology is changing academia

Seven projects awarded Star-Friedman Challenge grants

Fossil record stretching millions of years shows tiny ocean creatures on the move before Earth heats up

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

How far has COVID set back students?

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Why writing by hand beats typing for thinking and learning

Jonathan Lambert

If you're like many digitally savvy Americans, it has likely been a while since you've spent much time writing by hand.

The laborious process of tracing out our thoughts, letter by letter, on the page is becoming a relic of the past in our screen-dominated world, where text messages and thumb-typed grocery lists have replaced handwritten letters and sticky notes. Electronic keyboards offer obvious efficiency benefits that have undoubtedly boosted our productivity — imagine having to write all your emails longhand.

To keep up, many schools are introducing computers as early as preschool, meaning some kids may learn the basics of typing before writing by hand.

But giving up this slower, more tactile way of expressing ourselves may come at a significant cost, according to a growing body of research that's uncovering the surprising cognitive benefits of taking pen to paper, or even stylus to iPad — for both children and adults.

Is this some kind of joke? A school facing shortages starts teaching standup comedy

In kids, studies show that tracing out ABCs, as opposed to typing them, leads to better and longer-lasting recognition and understanding of letters. Writing by hand also improves memory and recall of words, laying down the foundations of literacy and learning. In adults, taking notes by hand during a lecture, instead of typing, can lead to better conceptual understanding of material.

"There's actually some very important things going on during the embodied experience of writing by hand," says Ramesh Balasubramaniam , a neuroscientist at the University of California, Merced. "It has important cognitive benefits."

While those benefits have long been recognized by some (for instance, many authors, including Jennifer Egan and Neil Gaiman , draft their stories by hand to stoke creativity), scientists have only recently started investigating why writing by hand has these effects.

A slew of recent brain imaging research suggests handwriting's power stems from the relative complexity of the process and how it forces different brain systems to work together to reproduce the shapes of letters in our heads onto the page.

Your brain on handwriting

Both handwriting and typing involve moving our hands and fingers to create words on a page. But handwriting, it turns out, requires a lot more fine-tuned coordination between the motor and visual systems. This seems to more deeply engage the brain in ways that support learning.

Shots - Health News

Feeling artsy here's how making art helps your brain.

"Handwriting is probably among the most complex motor skills that the brain is capable of," says Marieke Longcamp , a cognitive neuroscientist at Aix-Marseille Université.

Gripping a pen nimbly enough to write is a complicated task, as it requires your brain to continuously monitor the pressure that each finger exerts on the pen. Then, your motor system has to delicately modify that pressure to re-create each letter of the words in your head on the page.

"Your fingers have to each do something different to produce a recognizable letter," says Sophia Vinci-Booher , an educational neuroscientist at Vanderbilt University. Adding to the complexity, your visual system must continuously process that letter as it's formed. With each stroke, your brain compares the unfolding script with mental models of the letters and words, making adjustments to fingers in real time to create the letters' shapes, says Vinci-Booher.

That's not true for typing.

To type "tap" your fingers don't have to trace out the form of the letters — they just make three relatively simple and uniform movements. In comparison, it takes a lot more brainpower, as well as cross-talk between brain areas, to write than type.

Recent brain imaging studies bolster this idea. A study published in January found that when students write by hand, brain areas involved in motor and visual information processing " sync up " with areas crucial to memory formation, firing at frequencies associated with learning.

"We don't see that [synchronized activity] in typewriting at all," says Audrey van der Meer , a psychologist and study co-author at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. She suggests that writing by hand is a neurobiologically richer process and that this richness may confer some cognitive benefits.

Other experts agree. "There seems to be something fundamental about engaging your body to produce these shapes," says Robert Wiley , a cognitive psychologist at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. "It lets you make associations between your body and what you're seeing and hearing," he says, which might give the mind more footholds for accessing a given concept or idea.

Those extra footholds are especially important for learning in kids, but they may give adults a leg up too. Wiley and others worry that ditching handwriting for typing could have serious consequences for how we all learn and think.

What might be lost as handwriting wanes

The clearest consequence of screens and keyboards replacing pen and paper might be on kids' ability to learn the building blocks of literacy — letters.

"Letter recognition in early childhood is actually one of the best predictors of later reading and math attainment," says Vinci-Booher. Her work suggests the process of learning to write letters by hand is crucial for learning to read them.

"When kids write letters, they're just messy," she says. As kids practice writing "A," each iteration is different, and that variability helps solidify their conceptual understanding of the letter.

Research suggests kids learn to recognize letters better when seeing variable handwritten examples, compared with uniform typed examples.

This helps develop areas of the brain used during reading in older children and adults, Vinci-Booher found.

"This could be one of the ways that early experiences actually translate to long-term life outcomes," she says. "These visually demanding, fine motor actions bake in neural communication patterns that are really important for learning later on."

Ditching handwriting instruction could mean that those skills don't get developed as well, which could impair kids' ability to learn down the road.

"If young children are not receiving any handwriting training, which is very good brain stimulation, then their brains simply won't reach their full potential," says van der Meer. "It's scary to think of the potential consequences."

Many states are trying to avoid these risks by mandating cursive instruction. This year, California started requiring elementary school students to learn cursive , and similar bills are moving through state legislatures in several states, including Indiana, Kentucky, South Carolina and Wisconsin. (So far, evidence suggests that it's the writing by hand that matters, not whether it's print or cursive.)

Slowing down and processing information

For adults, one of the main benefits of writing by hand is that it simply forces us to slow down.

During a meeting or lecture, it's possible to type what you're hearing verbatim. But often, "you're not actually processing that information — you're just typing in the blind," says van der Meer. "If you take notes by hand, you can't write everything down," she says.

The relative slowness of the medium forces you to process the information, writing key words or phrases and using drawing or arrows to work through ideas, she says. "You make the information your own," she says, which helps it stick in the brain.

Such connections and integration are still possible when typing, but they need to be made more intentionally. And sometimes, efficiency wins out. "When you're writing a long essay, it's obviously much more practical to use a keyboard," says van der Meer.

Still, given our long history of using our hands to mark meaning in the world, some scientists worry about the more diffuse consequences of offloading our thinking to computers.

"We're foisting a lot of our knowledge, extending our cognition, to other devices, so it's only natural that we've started using these other agents to do our writing for us," says Balasubramaniam.

It's possible that this might free up our minds to do other kinds of hard thinking, he says. Or we might be sacrificing a fundamental process that's crucial for the kinds of immersive cognitive experiences that enable us to learn and think at our full potential.

Balasubramaniam stresses, however, that we don't have to ditch digital tools to harness the power of handwriting. So far, research suggests that scribbling with a stylus on a screen activates the same brain pathways as etching ink on paper. It's the movement that counts, he says, not its final form.

Jonathan Lambert is a Washington, D.C.-based freelance journalist who covers science, health and policy.

- handwriting

COMMENTS

Open in a separate window. First section: Description of the core center, contacts of the investigator/s, quantification of the involved centers. A research protocol must start from the definition of the coordinator of the whole study: all the details of the main investigator must be reported in the first paragraph.

The methodology should be standardized and clearly defined if multiple sites are engaged in a specified protocol. 6. Safety Considerations. The safety of participants is a top-tier priority while conducting clinical research. Safety aspects of the research should be scrutinized and provided in the research protocol. 7.

Writing the research protocol. 5.1 Introduction. After proper and complete planning of the study, the plan should be written down. The protocol is the detailed plan of the study. Every research study should have a protocol, and the protocol should be written. The written protocol: •.

The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

Writing of the research protocol should precede application for ethical and regulatory approval; and the final protocol will be required upfront by ethical committees and research and development departments. The length of the research protocol will be governed by the size and nature of the study - a multicenter drug trial will clearly have a ...

A research protocol is the road map you will follow in writing a grant proposal and carrying out your research. This chapter provides a long list of elements that may be included, such as study design, safety considerations, quality assurance, and ethical outcomes. Also included in the chapter are sections on what makes a good research protocol ...

It must convey exactly what you are going to do, in whom, where, when, and how. Methods must relate directly to and only to the specific objectives of the study. In the above example, recording the birthweight of all participants and a history of TB between the ages of 6 and 9 years would address objective 1.

The study protocol serves as a comprehensive guide and also represents the main document for external evaluation of the study (e.g., ethical committee, grant authorities). However, the purpose of the study protocol is to give a concise description of the study idea, plan, and further analysis. The writing style should be brief and concise.

Abstract. A research protocol is best viewed as a key to open the gates between the researcher and his/her research objectives. Each gate is defended by a gatekeeper whose role is to protect the resources and principles of a domain: the ethics committee protects participants and the underlying tenets of good practice, the postgraduate office protects institutional academic standards, the ...

The research protocol must give a clear indication of what follow up will be provided to the research participants and for how long. This may include a follow u, especially for adverse events, even after data collection for the research study is completed. ... This section should discuss the difficulties that the investigators anticipate in ...

Writing the protocol. Photo by Laura Chouette on Unsplash. A protocol should be prepared before a review is started and used as a guide to carry out the review. The aim of the protocol is to minimise bias by having pre-defined eligibility criteria of what will, and will not, be included in the review. The research protocol is a planning ...

A research protocol is a detailed study design or set of instructions for carrying out a specific experimental process or procedure. Open Access; ... A peer-reviewed PLOS ONE article contextualizing the protocol, with sections discussing applications, limitations, expected results and sample datasets. Submit now. Learn more about the benefits ...

The following outlines the basic elements of a research protocol. The IRB templates will provide more specific requirements. ... For Clinical Research The Methods section for clinical study protocols evaluating a drug, device or a treatment modality should explain the treatment plan. Baseline diagnostic tests, initial laboratory assessments for ...

The aim of this guide is to help researchers write a research study protocol for an observational study. The guide will take you through each section of the protocol giving advice and examples of the information required in that section. This is a guide only and for those requiring more information on particular topics; some useful references ...

Here's a list of steps on how to write a research protocol: 1. Write a project summary. A project summary is similar to the abstract of a research paper. It's usually a couple of hundred words and contains a brief synopsis of the protocol's central elements. For example, you may summarize information about the protocol's expected outcomes, time ...

09/21/2022. Every clinical investigation begins with the development of a clinical protocol. The protocol is a document that describes how a clinical trial will be conducted (the objective (s), design, methodology, statistical considerations and organization of a clinical trial,) and ensures the safety of the trial subjects and integrity of the ...

A badly written protocol can contribute substantially to approval times especially for investigator-initiated studies. The protocol provides the scientific basis for the proposed research; it defines the study objectives, the population to be studied, the procedures to be followed, the evaluations to be performed and the plan for analysis; and lastly, it discusses the administrative aspects of ...

Clinical Research Protocol is a formal design of an experiment. It is the plan submitted to an Institutional Review Board for review and to an agency for research support. The protocol includes a description of the research design to be employed, the eligibility requirements for prospective subjects and controls, the treatment regimen(s), and ...

The research protocol should provide the information needed for reviewers to determine that the regulatory and Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) policy requirements have been met. There is no required format or template; different sections and formatting may be used, provided the necessary information is included.