/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="research statement of work"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Graduate School Applications: Writing a Research Statement

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a Research Statement?

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential candidate’s application for post-undergraduate study. This may include applications for graduate programs, post-doctoral fellowships, or faculty positions. The research statement is often the primary way that a committee determines if a candidate’s interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

What Should It Look Like?

Research statements are generally one to two single-spaced pages. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application.

Your research statement should situate your work within the larger context of your field and show how your works contributes to, complicates, or counters other work being done. It should be written for an audience of other professionals in your field.

What Should It Include?

Your statement should start by articulating the broader field that you are working within and the larger question or questions that you are interested in answering. It should then move to articulate your specific interest.

The body of your statement should include a brief history of your past research . What questions did you initially set out to answer in your research project? What did you find? How did it contribute to your field? (i.e. did it lead to academic publications, conferences, or collaborations?). How did your past research propel you forward?

It should also address your present research . What questions are you actively trying to solve? What have you found so far? How are you connecting your research to the larger academic conversation? (i.e. do you have any publications under review, upcoming conferences, or other professional engagements?) What are the larger implications of your work?

Finally, it should describe the future trajectory on which you intend to take your research. What further questions do you want to solve? How do you intend to find answers to these questions? How can the institution to which you are applying help you in that process? What are the broader implications of your potential results?

Note: Make sure that the research project that you propose can be completed at the institution to which you are applying.

Other Considerations:

- What is the primary question that you have tried to address over the course of your academic career? Why is this question important to the field? How has each stage of your work related to that question?

- Include a few specific examples that show your success. What tangible solutions have you found to the question that you were trying to answer? How have your solutions impacted the larger field? Examples can include references to published findings, conference presentations, or other professional involvement.

- Be confident about your skills and abilities. The research statement is your opportunity to sell yourself to an institution. Show that you are self-motivated and passionate about your project.

- Enhancing Student Success

- Innovative Research

- Alumni Success

- About NC State

How to Construct a Compelling Research Statement

A research statement is a critical document for prospective faculty applicants. This document allows applicants to convey to their future colleagues the importance and impact of their past and, most importantly, future research. You as an applicant should use this document to lay out your planned research for the next few years, making sure to outline how your planned research contributes to your field.

Some general guidelines

(from Carleton University )

An effective research statement accomplishes three key goals:

- It clearly presents your scholarship in nonspecialist terms;

- It places your research in a broader context, scientifically and societally; and

- It lays out a clear road map for future accomplishments in the new setting (the institution to which you’re applying).

Another way to think about the success of your research statement is to consider whether, after reading it, a reader is able to answer these questions:

- What do you do (what are your major accomplishments; what techniques do you use; how have you added to your field)?

- Why is your work important (why should both other scientists and nonscientists care)?

- Where is it going in the future (what are the next steps; how will you carry them out in your new job; does your research plan meet the requirements for tenure at this institution)?

1. Make your statement reader-friendly

A typical faculty application call can easily receive 200+ applicants. As such, you need to make all your application documents reader-friendly. Use headings and subheadings to organize your ideas and leave white space between sections.

In addition, you may want to include figures and diagrams in your research statement that capture key findings or concepts so a reader can quickly determine what you are studying and why it is important. A wall of text in your research statement should be avoided at all costs. Rather, a research statement that is concise and thoughtfully laid out demonstrates to hiring committees that you can organize ideas in a coherent and easy-to-understand manner.

Also, this presentation demonstrates your ability to develop competitive funding applications (see more in next section), which is critical for success in a research-intensive faculty position.

2. Be sure to touch on the fundability of your planned research work

Another goal of your research statement is to make the case for why your planned research is fundable. You may get different opinions here, but I would recommend citing open or planned funding opportunities at federal agencies or other funders that you plan to submit to. You might also use open funding calls as a way to demonstrate that your planned research is in an area receiving funding prioritization by various agencies.

If you are looking for funding, check out this list of funding resources on my personal website. Another great way to look for funding is to use NIH Reporter and NSF award search .

3. Draft the statement and get feedback early and often

I can tell you from personal experience that it takes time to refine a strong research statement. I went on the faculty job market two years in a row and found my second year materials to be much stronger. You need time to read, review and reflect on your statements and documents to really make them stand out.

It is important to have your supervisor and other faculty read and give feedback on your critical application documents and especially your research statement. Also, finding peers to provide feedback and in return giving them feedback on their documents is very helpful. Seek out communities of support such as Future PI Slack to find peer reviewers (and get a lot of great application advice) if needed.

4. Share with nonexperts to assess your writing’s clarity

Additionally, you may want to consider sharing your job materials, including your research statement, with non-experts to assess clarity. For example, NC State’s Professional Development Team offers an Academic Packways: Gearing Up for Faculty program each year where you can get feedback on your application documents from individuals working in a variety of areas. You can also ask classmates and colleagues working in different areas to review your research statement. The more feedback you can receive on your materials through formal or informal means, the better.

5. Tailor your statement to the institution

It is critical in your research statement to mention how you will make use of core facilities or resources at the institution you are applying to. If you need particular research infrastructure to do your work and the institution has it, you should mention that in your statement. Something to the effect of: “The presence of the XXX core facility at YYY University will greatly facilitate my lab’s ability to investigate this important process.”

Mentioning core facilities and resources at the target institution shows you have done your research, which is critical in demonstrating your interest in that institution.

Finally, think about the resources available at the institution you are applying to. If you are applying to a primarily undergraduate-serving institution, you will want to be sure you propose a research program that could reasonably take place with undergraduate students, working mostly in the summer and utilizing core facilities that may be limited or require external collaborations.

Undergraduate-serving institutions will value research projects that meaningfully involve students. Proposing overly ambitious research at a primarily undergraduate institution is a recipe for rejection as the institution will read your application as out of touch … that either you didn’t do the work to research them or that you are applying to them as a “backup” to research-intensive positions.

You should carefully think about how to restructure your research statements if you are applying to both primarily undergraduate-serving and research-intensive institutions. For examples of how I framed my research statement for faculty applications at each type of institution, see my personal website ( undergraduate-serving ; research-intensive research statements).

6. Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants

In the end, a research statement allows you to think critically about where you see your research going in the future. What are you excited about studying based on your previous work? How will you go about answering the unanswered questions in your field? What agencies and initiatives are funding your type of research? If you develop your research statement from these core questions, your passion and commitment to the work will surely shine through.

A closing thought: Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants. If you try to frame yourself as someone you really aren’t, you are setting the hiring institution and you up for disappointment. You want a university to hire you because they like you, the work you have done, and the work you want to do, not some filtered or idealized version of you.

So, put your true self out there, and realize you want to find the right institutional fit for you and your research. This all takes time and effort. The earlier you start and the more reflection and feedback you get on your research statement and remaining application documents, the better you can present the true you to potential employers.

More Advice on Faculty Job Application Documents on ImPACKful

How to write a better academic cover letter

Tips on writing an effective teaching statement

More Resources

See here for samples of a variety of application materials from UCSF.

- Rules of the (Social Sciences & Humanities) Research Statement

- CMU’s Writing a Research Statement

- UW’s Academic Careers: Research Statements

- Developing a Winning Research Statement (UCSF)

- Academic Packways

- ImPACKful Tips

Leave a Response Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

More From The Graduate School

Advice From Newly Hired Assistant Professors

Virtual Postdoc Research Symposium Elevates and Supports Postdoctoral Scholars Across North Carolina

Expand Your Pack: Start or Join an Online Writing Group!

Statement of Work (SOW)

The Statement of Work (SOW) describes the what, why, how, and when of the research project. It shows how the project relates to the sponsor’s purpose and goals. For the proposal to succeed in peer review, it must win over the assigned reviewers. The application has two audiences: a small number who are familiar with the field, and the majority of reviewers who are probably not familiar with the proposed research techniques or field. All reviewers are important because each reviewer gets one vote. The proposal should be written and organized so all the reviewers can readily grasp and explain what is proposed and advocate for the proposal.

The statement of work should provide a clear description of the work to be undertaken and must include:

Objectives for the period of the proposed work

Expected significance of the proposed work

Relation to longer-term goals of the PI's project

Relation to the present state of knowledge in the field

Relation to work in progress by the PI under other support

Relation to work in progress elsewhere.

The statement of work should outline the general plan of work, including the broad design of activities to be undertaken, and, where appropriate, provide a clear description of experimental methods and procedures.

Created: 12.21.2020

Updated: 04.22.2024

Writing a Research Statement

What is a research statement.

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential student's application for post-undergraduate study. The research statement is often the primary way for departments and faculty to determine if a student's interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

Although many programs ask for ‘personal statements,' these are not really meant to be biographies or life stories. What we, at Tufts Psychology, hope to find out is how well your abilities, interests, experiences and goals would fit within our program.

We encourage you to illustrate how your lived experience demonstrates qualities that are critical to success in pursuing a PhD in our program. Earning a PhD in any program is hard! Thus, as you are relaying your past, present, and future research interests, we are interested in learning how your lived experiences showcase the following:

- Perseverance

- Resilience in the face of difficulty

- Motivation to undertake intensive research training

- Involvement in efforts to promote equity and inclusion in your professional and/or personal life

- Unique perspectives that enrich the research questions you ask, the methods you use, and the communities to whom your research applies

How Do I Even Start Writing One?

Before you begin your statement, read as much as possible about our program so you can tailor your statement and convince the admissions committee that you will be a good fit.

Prepare an outline of the topics you want to cover (e.g., professional objectives and personal background) and list supporting material under each main topic. Write a rough draft in which you transform your outline into prose. Set it aside and read it a week later. If it still sounds good, go to the next stage. If not, rewrite it until it sounds right.

Do not feel bad if you do not have a great deal of experience in psychology to write about; no one who is about to graduate from college does. Do explain your relevant experiences (e.g., internships or research projects), but do not try to turn them into events of cosmic proportion. Be honest, sincere, and objective.

What Information Should It Include?

Your research statement should describe your previous experience, how that experience will facilitate your graduate education in our department, and why you are choosing to pursue graduate education in our department. Your goal should be to demonstrate how well you will fit in our program and in a specific laboratory.

Make sure to link your research interests to the expertise and research programs of faculty here. Identify at least one faculty member with whom you would like to work. Make sure that person is accepting graduate students when you apply. Read some of their papers and describe how you think the research could be extended in one or more novel directions. Again, specificity is a good idea.

Make sure to describe your relevant experience (e.g., honors thesis, research assistantship) in specific detail. If you have worked on a research project, discuss that project in detail. Your research statement should describe what you did on the project and how your role impacted your understanding of the research question.

Describe the concrete skills you have acquired prior to graduate school and the skills you hope to acquire.

Articulate why you want to pursue a graduate degree at our institution and with specific faculty in our department.

Make sure to clearly state your core research interests and explain why you think they are scientifically and/or practically important. Again, be specific.

What Should It Look Like?

Your final statement should be succinct. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application. Finally, stick to the points requested by each program, and avoid lengthy personal or philosophical discussions.

How Do I Know if It is Ready?

Ask for feedback from at least one professor, preferably in the area you are interested in. Feedback from friends and family may also be useful. Many colleges and universities also have writing centers that are able to provide general feedback.

Of course, read and proofread the document multiple times. It is not always easy to be a thoughtful editor of your own work, so don't be afraid to ask for help.

Lastly, consider signing up to take part in the Application Statement Feedback Program . The program provides constructive feedback and editing support for the research statements of applicants to Psychology PhD programs in the United States.

How to Write a Research Statement

- Experimental Psychology

Task #1: Understand the Purpose of the Research Statement

The primary mistake people make when writing a research statement is that they fail to appreciate its purpose. The purpose isn’t simply to list and briefly describe all the projects that you’ve completed, as though you’re a museum docent and your research publications are the exhibits. “Here, we see a pen and watercolor self-portrait of the artist. This painting is the earliest known likeness of the artist. It captures the artist’s melancholic temperament … Next, we see a steel engraving. This engraving has appeared in almost every illustrated publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and has also appeared as the television studio back-drop for the …”

Similar to touring through a museum, we’ve read through research statements that narrate a researcher’s projects: “My dissertation examined the ways in which preschool-age children’s memory for a novel event was shaped by the verbal dialogue they shared with trained experimenters. The focus was on the important use of what we call elaborative conversational techniques … I have recently launched another project that represents my continued commitment to experimental methods and is yet another extension of the ways in which we can explore the role of conversational engagement during novel events … In addition to my current experimental work, I am also involved in a large-scale collaborative longitudinal project …”

Treating your research statement as though it’s a narrated walk through your vita does let you describe each of your projects (or publications). But the format is boring, and the statement doesn’t tell us much more than if we had the abstracts of each of your papers. Most problematic, treating your research statement as though it’s a narrated walk through your vita misses the primary purpose of the research statement, which is to make a persuasive case about the importance of your completed work and the excitement of your future trajectory.

Writing a persuasive case about your research means setting the stage for why the questions you are investigating are important. Writing a persuasive case about your research means engaging your audience so that they want to learn more about the answers you are discovering. How do you do that? You do that by crafting a coherent story.

Task #2: Tell a Story

Surpass the narrated-vita format and use either an Op-Ed format or a Detective Story format. The Op-Ed format is your basic five-paragraph persuasive essay format:

First paragraph (introduction):

- broad sentence or two introducing your research topic;

- thesis sentence, the position you want to prove (e.g., my research is important); and

- organization sentence that briefly overviews your three bodies of evidence (e.g., my research is important because a, b, and c).

Second, third, and fourth paragraphs (each covering a body of evidence that will prove your position):

- topic sentence (about one body of evidence);

- fact to support claim in topic sentence;

- another fact to support claim in topic sentence;

- another fact to support claim in topic sentence; and

- analysis/transition sentence.

Fifth paragraph (synopsis and conclusion):

- sentence that restates your thesis (e.g., my research is important);

- three sentences that restate your topic sentences from second, third, and fourth paragraph (e.g., my research is important because a, b, and c); and

- analysis/conclusion sentence.

Although the five-paragraph persuasive essay format feels formulaic, it works. It’s used in just about every successful op-ed ever published. And like all good recipes, it can be doubled. Want a 10-paragraph, rather than five-paragraph research statement? Double the amount of each component. Take two paragraphs to introduce the point you’re going to prove. Take two paragraphs to synthesize and conclude. And in the middle, either raise six points of evidence, with a paragraph for each, or take two paragraphs to supply evidence for each of three points. The op-ed format works incredibly well for writing persuasive essays, which is what your research statement should be.

The Detective Story format is more difficult to write, but it’s more enjoyable to read. Whereas the op-ed format works off deductive reasoning, the Detective Story format works off inductive reasoning. The Detective Story does not start with your thesis statement (“hire/retain/promote/ award/honor me because I’m a talented developmental/cognitive/social/clinical/biological/perception psychologist”). Rather, the Detective Story starts with your broad, overarching research question. For example, how do babies learn their native languages? How do we remember autobiographical information? Why do we favor people who are most similar to ourselves? How do we perceive depth? What’s the best way to treat depression? How does the stress we experience every day affect our long-term health?

Because it’s your research statement, you can personalize that overarching question. A great example of a personalized overarching question occurs in the opening paragraph of George Miller’s (1956) article, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.”

My problem is that I have been persecuted by an integer. For seven years this number has followed me around, has intruded in my most private data, and has assaulted me from the pages of our most public journals. This number assumes a variety of disguises, being sometimes a little larger and sometimes a little smaller than usual, but never changing so much as to be unrecognizable. The persistence with which this number plagues me is far more than a random accident. There is, to quote a famous senator, a design behind it, some pattern governing its appearances. Either there really is something unusual about the number or else I am suffering from delusions of persecution. I shall begin my case history by telling you about some experiments that tested how accurately people can assign numbers to the magnitudes of various aspects of a stimulus. …

In case you think the above opening was to a newsletter piece or some other low-visibility outlet, it wasn’t. Those opening paragraphs are from a Psych Review article, which has been cited nearly 16,000 times. Science can be personalized. Another example of using the Detective Story format, which opens with your broad research question and personalizes it, is the opening paragraph of a research statement from a chemist:

I became interested in inorganic chemistry because of one element: Boron. The cage structures and complexity of boron hydrides have fascinated my fellow Boron chemists for more than 40 years — and me for more than a decade. Boron is only one element away from carbon, yet its reactivity is dramatically different. I research why.

When truest to the genre of Detective Story format, the full answer to your introductory question won’t be available until the end of your statement — just like a reader doesn’t know whodunit until the last chapter of a mystery. Along the way, clues to the answer are provided, and false leads are ruled out, which keeps readers turning the pages. In the same way, writing your research statement in the Detective Story format will keep members of the hiring committee, the review committee, and the awards panel reading until the last paragraph.

Task #3: Envision Each Audience

The second mistake people make when writing their research statements is that they write for the specialist, as though they’re talking to another member of their lab. But in most cases, the audience for your research statement won’t be well-informed specialists. Therefore, you need to convey the importance of your work and the contribution of your research without getting bogged down in jargon. Some details are important, but an intelligent reader outside your area of study should be able to understand every word of your research statement.

Because research statements are most often included in academic job applications, tenure and promotion evaluations, and award nominations, we’ll talk about how to envision the audiences for each of these contexts.

Job Applications . Even in the largest department, it’s doubtful that more than a couple of people will know the intricacies of your research area as well as you do. And those two or three people are unlikely to have carte blanche authority on hiring. Rather, in most departments, the decision is made by the entire department. In smaller departments, there’s probably no one else in your research area; that’s why they have a search going on. Therefore, the target audience for your research statement in a job application comprises other psychologists, but not psychologists who study what you study (the way you study it).

Envision this target audience explicitly.Think of one of your fellow graduate students or post docs who’s in another area (e.g., if you’re in developmental, think of your friend in biological). Envision what that person will — and won’t — know about the questions you’re asking in your research, the methods you’re using, the statistics you’re employing, and — most importantly — the jargon that you usually use to describe all of this. Write your research statement so that this graduate student or post doc in another area in psychology will not only understand your research statement, but also find your work interesting and exciting.

Tenure Review . During the tenure review process, your research statement will have two target audiences: members of your department and, if your tenure case receives a positive vote in the department, members of the university at large. For envisioning the first audience, follow the advice given above for writing a research statement for a job application. Think of one of your departmental colleagues in another area (e.g., if you’re in developmental, think of your friend in biological). Write in such a way that the colleague in another area in psychology will understand every word — and find the work interesting. (This advice also applies to writing research statements for annual reviews, for which the review is conducted in the department and usually by all members of the department.)

For the second stage of the tenure process, when your research statement is read by members of the university at large, you’re going to have to scale it down a notch. (And yes, we are suggesting that you write two different statements: one for your department’s review and one for the university’s review, because the audiences differ. And you should always write with an explicit target audience in mind.) For the audience that comprises the entire university, envision a faculty friend in another department. Think political science or economics or sociology, because your statement will be read by political scientists, economists, and sociologists. It’s an art to hit the perfect pitch of being understood by such a wide range of scholars without being trivial, but it’s achievable.

Award Nominations . Members of award selection committees are unlikely to be specialists in your immediate field. Depending on the award, they might not even be members of your discipline. Find out the typical constitution of the selection committee for each award nomination you submit, and tailor your statement accordingly.

Task #4: Be Succinct

When writing a research statement, many people go on for far too long. Consider three pages a maximum, and aim for two. Use subheadings to help break up the wall of text. You might also embed a well-designed figure or graph, if it will help you make a point. (If so, use wrap-around text, and make sure that your figure has its axes labeled.)

And don’t use those undergraduate tricks of trying to cram more in by reducing the margins or the font size. Undoubtedly, most of the people reading your research statement will be older than you, and we old folks don’t like reading small fonts. It makes us crabby, and that’s the last thing you want us to be when we’re reading your research statement.

Nice piece of information. I will keep in mind while writing my research statement

Thank you so much for your guidance.

HOSSEIN DIVAN-BEIGI

Absolutely agree! I also want to add that: On the one hand it`s easy to write good research personal statement, but on the other hand it`s a little bit difficult to summarize all minds and as result the main idea of the statement could be incomprehensible. It also seems like a challenge for those guys, who aren`t native speakers. That`s why you should prepare carefully for this kind of statement to target your goals.

How do you write an action research topic?? An then stAte the problem an purpose for an action research. Can I get an example on language development?? Please I need some help.

Thankyou I now have idea to come up with the research statement. If I need help I will inform you …

much appreciated

Just like Boote & Beile (2005) explained “Doctors before researchers” because of the importance of the dissertation literature review in research groundwork.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Authors

Morton Ann Gernsbacher , APS Past President, is the Vilas Research Professor and Sir Frederic Bartlett Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Patricia G. Devine , a Past APS Board Member, is Chair of the Department of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Careers Up Close: Joel Anderson on Gender and Sexual Prejudices, the Freedoms of Academic Research, and the Importance of Collaboration

Joel Anderson, a senior research fellow at both Australian Catholic University and La Trobe University, researches group processes, with a specific interest on prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes.

Experimental Methods Are Not Neutral Tools

Ana Sofia Morais and Ralph Hertwig explain how experimental psychologists have painted too negative a picture of human rationality, and how their pessimism is rooted in a seemingly mundane detail: methodological choices.

APS Fellows Elected to SEP

In addition, an APS Rising Star receives the society’s Early Investigator Award.

Privacy Overview

- Utility Menu

6b604b7f91d918e5639cf90ab80a98b4

Harvard t.h. chan school of public health research administration.

- Institutional Info

- eRA Commons Setup

- Statement of Work (SOW)

The Statement of Work (SOW) is the heart of any subagreement at Harvard University. Similar to the Project Description/Research Plan, it describes the proposed work to be performed on a research project or sponsored activity. It is designed to provide ta full and detailed explanation of the proposed activity, typically including project goals, specific aims, methodology, and Investigator responsibilities for an agreement, including pricing information and a schedule of deliverables, if applicable. The SOW should be no shorter than a paragraph in length.

Statement of Intent Form (SOI)

A subrecipient's Statement of Work and other institutional information is provided to the Harvard Chan School using a signed Statement of Intent (SOI) form . At the proposal stage, an SOI must be completed and signed by each institution listed as a subrecipient on an Harvard Chan School proposal, prior to submission. If a subagreement is being added to an award after the proposal stage, an SOI must be completed and signed by the institution, at the new subagreement approval stage.

Please note: HSPH's SOI is to be used on all submissions when we are the prime. Changes are rarely allowable. If changes are made to this SOI, or an alternative to our SOI is desired, the assigned AD must be informed, and review/approve these changes.

Sponsor Specific Requirements

Research plan .

Source: NIH

A description of the rationale for your research and your experiments. Your Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, where you describe your research rationale and the experiments you will conduct to accomplish each aim. Information you put in the Research Plan affects just about every other application part. This section will vary in length determined by the sponsor and the particular RFA to which you are applying. You'll need to keep everything in sync as your plans evolve during the writing phase.

Read complete NIH instructions

Project Description

Source: NSF

The Project Description must contain, as a separate section within the narrative, a section labeled “Intellectual Merit”. The Project Description should provide a clear statement of the work to be undertaken and must include the objectives for the period of the proposed work and expected significance; the relationship of this work to the present state of knowledge in the field, as well as to work in progress by the PI under other support.

The Project Description should outline the general plan of work, including the broad design of activities to be undertaken, and, where appropriate, provide a clear description of experimental methods and procedures. Proposers should address what they want to do, why they want to do it, how they plan to do it, how they will know if they succeed, and what benefits could accrue if the project is successful. The project activities may be based on previously established and/or innovative methods and approaches, but in either case must be well justified. These issues apply to both the technical aspects of the proposal and the way in which the project may make broader contributions.

The Project Description also must contain, as a separate section within the narrative, a section labeled “Broader Impacts”. This section should provide a discussion of the broader impacts of the proposed activities. Broader impacts may be accomplished through the research itself, through the activities that are directly related to specific research projects, or through activities that are supported by, but are complementary to the project. NSF values the advancement of scientific knowledge and activities that contribute to the achievement of societally relevant outcomes. Such outcomes include, but are not limited to: full participation of women, persons with disabilities, and underrepresented minorities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); improved STEM education and educator development at any level; increased public scientific literacy and public engagement with science and technology; improved well-being of individuals in society; development of a diverse, globally competitive STEM workforce; increased partnerships between academia, industry, and others; improved national security; increased economic competitiveness of the U.S.; and enhanced infrastructure for research and education.

Plans for data management and sharing of the products of research, including preservation, documentation, and sharing of data, samples, physical collections, curriculum materials and other related research and education products should be described in the Special Information and Supplementary Documentation section of the proposal (see Chapter II.C.2.j for additional instructions for preparation of this section). For proposals that include funding to an International Branch Campus of a U.S. IHE or to a foreign organization (including through use of a subaward or consultant arrangement), the proposer must provide the requisite explanation/justification in the project description. See Chapter I.E for additional information on the content requirements.

Read complete NSF instructions

GMAS Requirement

The SOW/ Project Description/ Research Plan must be uploaded to the GMAS request document repository.

Statement of Work (SOW) with Data Exchange

When a PI is writing a Statement of Work (SOW) that involves data exchange , it's helpful if the PI includes the following clarifying information in the SOW:

- e.g., Purdue University will send de-identified data to Harvard Chan consortium PI and Harvard Chan consortium PI will ____ (do what with the data?)

- De-Identified Data : De-identified data stripped of all person's "direct identifiers", (e.g., stripped of HIPAA's 16 categories of direct identifiers)

- Limited Data Set : stripped of all person's "direct identifiers" but can include geographic data, dates, and other unique identifier, characteristic or code other than those specified in the list of 16 identifiers that are expressly disallowed.

- Fully Identifiable : information with any personal identifiers, as well as information about an individual, or his or her relatives, household members, or employer that alone or in combination could identify the individual, including full-on HIPAA covered under Protected Health Information.

- e.g., BWH, sub under Purdue University, will provide a limited data set to Harvard Chan and Harvard Chan will___(do what with the data?)

- Add to SOW: “If necessary, a data-use agreement (DUA) will be executed between the parties.”

- Identify the materials and state all of the direction of the materials exchange -> from which organization to which organization?

- Add to SOW: “If necessary, a material transfer agreement (MTA) will be executed between the parties.”

- Find Funding

- Funding Sources

- Proposal Deadlines

- PI Eligibility

- Limited Submissions

- Letters of Support

- NIH Applications

- NSF Applications

- Utility Menu

- Site Search

- SOW/Research Plan

The Project Description/Research Plan describes the project work to be performed on a research project or sponsored activity. On a subagreement, a similar document is known as the Statement of Work. Each sponsor has specified guidelines for these sections.

Statement of Work (SOW)

One of the most critical elements of a Harvard proposal that is a subaward, is the Statement of Work (SOW). At a minimum, the SOW should provide a full and detailed explanation of the proposed activity, typically including project goals, specific aims, methodology, and Investigator responsibilities. It should be no shorter than a paragraph in length.

Sponsor Specific Requirements

Research plan , source: nih .

A description of the rationale for your research and your experiments. Your Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, where you describe your research rationale and the experiments you will conduct to accomplish each aim. Information you put in the Research Plan affects just about every other application part. This section will vary in length determined by the sponsor and the particular RFA to which you are applying. You'll need to keep everything in sync as your plans evolve during the writing phase.

Read complete NIH instructions

Project Description

Source: nsf .

The Project Description must contain, as a separate section within the narrative, a section labeled “Intellectual Merit”. The Project Description should provide a clear statement of the work to be undertaken and must include the objectives for the period of the proposed work and expected significance; the relationship of this work to the present state of knowledge in the field, as well as to work in progress by the PI under other support.

The Project Description should outline the general plan of work, including the broad design of activities to be undertaken, and, where appropriate, provide a clear description of experimental methods and procedures. Proposers should address what they want to do, why they want to do it, how they plan to do it, how they will know if they succeed, and what benefits could accrue if the project is successful. The project activities may be based on previously established and/or innovative methods and approaches, but in either case must be well justified. These issues apply to both the technical aspects of the proposal and the way in which the project may make broader contributions.

The Project Description also must contain, as a separate section within the narrative, a section labeled “Broader Impacts”. This section should provide a discussion of the broader impacts of the proposed activities. Broader impacts may be accomplished through the research itself, through the activities that are directly related to specific research projects, or through activities that are supported by, but are complementary to the project. NSF values the advancement of scientific knowledge and activities that contribute to the achievement of societally relevant outcomes. Such outcomes include, but are not limited to: full participation of women, persons with disabilities, and underrepresented minorities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); improved STEM education and educator development at any level; increased public scientific literacy and public engagement with science and technology; improved well-being of individuals in society; development of a diverse, globally competitive STEM workforce; increased partnerships between academia, industry, and others; improved national security; increased economic competitiveness of the U.S.; and enhanced infrastructure for research and education.

Plans for data management and sharing of the products of research, including preservation, documentation, and sharing of data, samples, physical collections, curriculum materials and other related research and education products should be described in the Special Information and Supplementary Documentation section of the proposal (see Chapter II.C.2.j for additional instructions for preparation of this section). For proposals that include funding to an International Branch Campus of a U.S. IHE or to a foreign organization (including through use of a subaward or consultant arrangement), the proposer must provide the requisite explanation/justification in the project description. See Chapter I.E for additional information on the content requirements.

Read complete NSF instructions

GMAS Requirement

The SOW/ Project Description/ Research Plan must be uploaded to the GMAS request document repository.

- Sponsor Set up

- C&P/Other Support

- CV/Bio Sketch

- Collaborator/Consultant/Other Significant Contributor

- Including a Subrecipient on Proposal Submissions

- Interfaculty Involvement

- Representations and Certifications

- Subrecipient vs. Vendor

- When Harvard is the Subrecipient

- Proposal Review

- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors

- Social Media

- Career Services Policies

- Walk-Ins & Pop-Ins

- Strategic Plan 2022-2025

Research statements for faculty job applications

The purpose of a research statement.

The main goal of a research statement is to walk the search committee through the evolution of your research, to highlight your research accomplishments, and to show where your research will be taking you next. To a certain extent, the next steps that you identify within your statement will also need to touch on how your research could benefit the institution to which you are applying. This might be in terms of grant money, faculty collaborations, involving students in your research, or developing new courses. Your CV will usually show a search committee where you have done your research, who your mentors have been, the titles of your various research projects, a list of your papers, and it may provide a very brief summary of what some of this research involves. However, there can be certain points of interest that a CV may not always address in enough detail.

- What got you interested in this research?

- What was the burning question that you set out to answer?

- What challenges did you encounter along the way, and how did you overcome these challenges?

- How can your research be applied?

- Why is your research important within your field?

- What direction will your research take you in next, and what new questions do you have?

While you may not have a good sense of where your research will ultimately lead you, you should have a sense of some of the possible destinations along the way. You want to be able to show a search committee that your research is moving forward and that you are moving forward along with it in terms of developing new skills and knowledge. Ultimately, your research statement should complement your cover letter, CV, and teaching philosophy to illustrate what makes you an ideal candidate for the job. The more clearly you can articulate the path your research has taken, and where it will take you in the future, the more convincing and interesting it will be to read.

Separate research statements are usually requested from researchers in engineering, social, physical, and life sciences, but can also be requested for researchers in the humanities. In many cases, however, the same information that is covered in the research statement is often integrated into the cover letter for many disciplines within the humanities and no separate research statement is requested within the job advertisement. Seek advice from current faculty and new hires about the conventions of your discipline if you are in doubt.

Timeline: Getting Started with your Research Statement

You can think of a research statement as having three distinct parts. The first part will focus on your past research, and can include the reasons you started your research, an explanation as to why the questions you originally asked are important in your field, and a summary some of the work you did to answer some of these early questions.

The middle part of the research statement focuses on your current research. How is this research different from previous work you have done, and what brought you to where you are today? You should still explain the questions you are trying to ask, and it is very important that you focus on some of the findings that you have (and cite some of the publications associated with these findings). In other words, do not talk about your research in abstract terms, make sure that you explain your actual results and findings (even if these may not be entirely complete when you are applying for faculty positions), and mention why these results are significant.

The final part of your research statement should build on the first two parts. Yes, you have asked good questions, and used good methods to find some answers, but how will you now use this foundation to take you into your future? Since you are hoping that your future will be at one of the institutions to which you are applying, you should provide some convincing reasons why your future research will be possible at each institution, and why it will be beneficial to that institution, or to the students at that institution.

While you are focusing on the past, present, and future or your research, and tailoring it to each institution, you should also think about the length of your statement and how detailed or specific you make the descriptions of your research. Think about who will be reading it. Will they all understand the jargon you are using? Are they experts in the subject, or experts in a range of related subjects? Can you go into very specific detail, or do you need to talk about your research in broader terms that make sense to people outside of your research field focusing on the common ground that might exist? Additionally, you should make sure that your future research plans differ from those of your PI or advisor, as you need to be seen as an independent researcher. Identify 4-5 specific aims that can be divided into short-term and long-term goals. You can give some idea of a 5-year research plan that includes the studies you want to perform, but also mention your long-term plans, so that the search committee knows that this is not a finite project.

Another important consideration when writing about your research is realizing that you do not perform research in a vacuum. When doing your research you may have worked within a team environment at some point, or sought out specific collaborations. You may have faced some serious challenges that required some creative problem-solving to overcome. While these aspects are not necessarily as important as your results and your papers or patents, they can help paint a picture of you as a well-rounded researcher who is likely to be successful in the future even if new problems arise, for example.

Follow these general steps to begin developing an effective research statement:

Step 1: Think about how and why you got started with your research. What motivated you to spend so much time on answering the questions you developed? If you can illustrate some of the enthusiasm you have for your subject, the search committee will likely assume that students and other faculty members will see this in you as well. People like to work with passionate and enthusiastic colleagues. Remember to focus on what you found, what questions you answered, and why your findings are significant. The research you completed in the past will have brought you to where you are today; also be sure to show how your research past and research present are connected. Explore some of the techniques and approaches you have successfully used in your research, and describe some of the challenges you overcame. What makes people interested in what you do, and how have you used your research as a tool for teaching or mentoring students? Integrating students into your research may be an important part of your future research at your target institutions. Conclude describing your current research by focusing on your findings, their importance, and what new questions they generate.

Step 2: Think about how you can tailor your research statement for each application. Familiarize yourself with the faculty at each institution, and explore the research that they have been performing. You should think about your future research in terms of the students at the institution. What opportunities can you imagine that would allow students to get involved in what you do to serve as a tool for teaching and training them, and to get them excited about your subject? Do not talk about your desire to work with graduate students if the institution only has undergraduates! You will also need to think about what equipment or resources that you might need to do your future research. Again, mention any resources that specific institutions have that you would be interested in utilizing (e.g., print materials, super electron microscopes, archived artwork). You can also mention what you hope to do with your current and future research in terms of publication (whether in journals or as a book), try to be as specific and honest as possible. Finally, be prepared to talk about how your future research can help bring in grants and other sources of funding, especially if you have a good track record of receiving awards and fellowships. Mention some grants that you know have been awarded to similar research, and state your intention to seek this type of funding.

Step 3: Ask faculty in your department if they are willing to share their own research statements with you. To a certain extent, there will be some subject-specific differences in what is expected from a research statement, and so it is always a good idea to see how others in your field have done it. You should try to draft your own research statement first before you review any statements shared with you. Your goal is to create a unique research statement that clearly highlights your abilities as a researcher.

Step 4: The research statement is typically a few (2-3) pages in length, depending on the number of images, illustrations, or graphs included. Once you have completed the steps above, schedule an appointment with a career advisor to get feedback on your draft. You should also try to get faculty in your department to review your document if they are willing to do so.

Explore other application documents:

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about the abortion debate in America

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

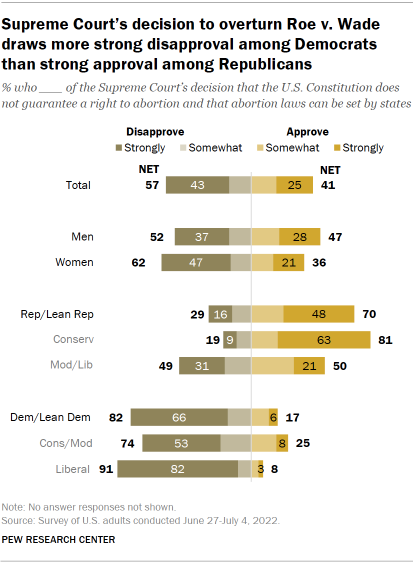

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

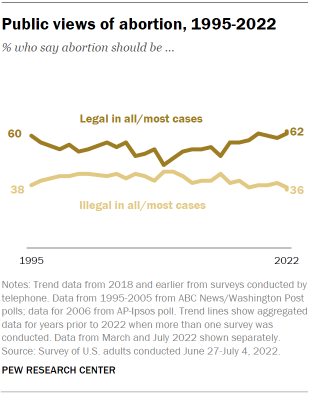

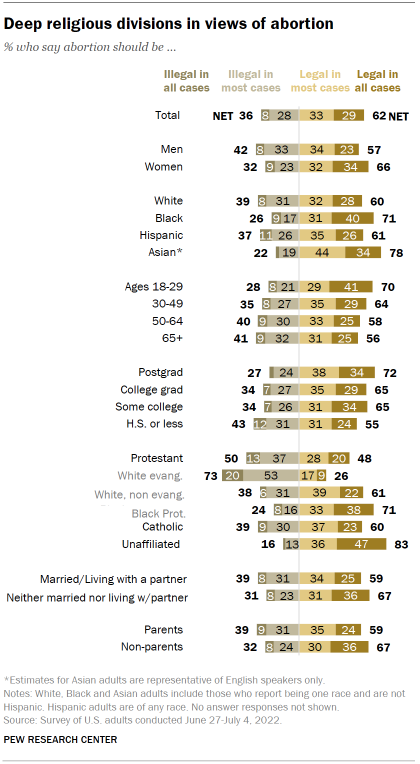

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

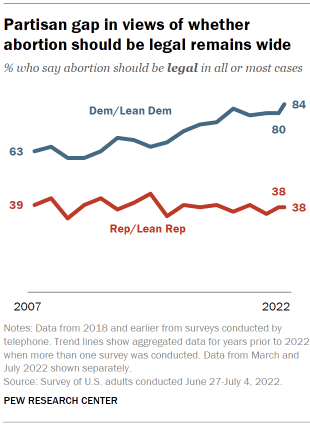

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

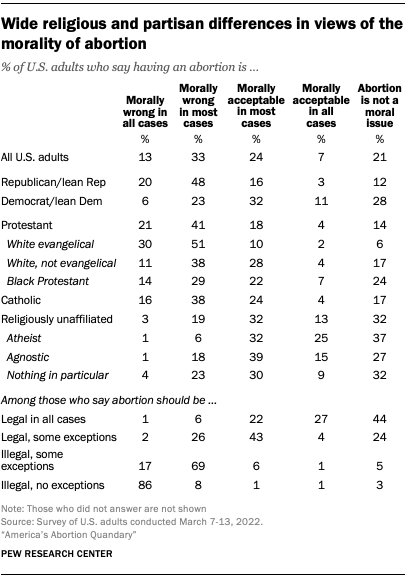

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

- Religion & Abortion

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many countries, especially in europe, nearly a year after roe’s demise, americans’ views of abortion access increasingly vary by where they live, by more than two-to-one, americans say medication abortion should be legal in their state, most latinos say democrats care about them and work hard for their vote, far fewer say so of gop, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Global directory Global directory

- Product logins Product logins

- Contact us Contact us

Our Privacy Statement & Cookie Policy

All Thomson Reuters websites use cookies to improve your online experience. They were placed on your computer when you launched this website. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.

- Privacy Statement

- Cookie Policy

Join our community

Sign up for industry-leading insights, updates, and all things AI @ Thomson Reuters.

Webcast and events

Browse all our upcoming and on-demand webcasts and virtual events hosted by leading legal experts.

Generative AI for legal professionals: What to know and what to do right now

AI is reshaping the legal landscape by providing invaluable support across various roles in law firms and legal departments. Rather than replacing legal professionals, gen AI enhances efficiency, accelerates tasks, and enables lawyers to focus on applying their expertise.

Westlaw Precision | Harness the power of generative AI

Innovative tools deliver advanced speed and accuracy, providing you with greater confidence in your legal research

Related posts

6 ways law firms can set themselves up for innovation success

Legal professionals with GenAI see increased efficiency and productivity, as shown in new report

How businesses can responsibly use AI and address ethical and security challenges

More answers.

Get your key stakeholders on board with contract lifecycle management

How can corporations prioritize risk mitigation while still remaining profitable?

Antitrust Law Basics – Section 2 of the Sherman Act

- Exhibitions

- General Information

- Press Images

- FAQs for Media

- Search the Press Room

Press release

The metropolitan museum of art returns sculpture to the republic of iraq.

The Met initiated the return of the Early Dynastic figurative sculpture after provenance research by Met scholars established that the work rightfully belongs to Iraq (New York, April 16, 2024)—The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Republic of Iraq announced today that The Met has repatriated a third-millennium BCE Sumerian sculpture—the copper alloy depiction of a man carrying a box, possibly for offerings—to the Republic of Iraq. The repatriation was marked by a ceremony in Washington D.C. with the Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq, His Excellency Mohamed Shia’ Al Sudani; Ambassador of the Republic of Iraq to the United States of America, His Excellency Nazar Al Khirullah; United States Ambassador to Iraq, Alina L. Romanowski; and from The Met, Andrea Bayer, Deputy Director for Collections and Administration; and Kim Benzel, Curator in Charge, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art.

The Met purchased the statue in 1955. After provenance research by the Museum’s scholars established that the work rightfully belongs to the Republic of Iraq, the Museum met with H.E. Nazar Al Khirullah, Ambassador of the Republic of Iraq to the United States of America, and offered to return the work. The repatriation follows the launch of The Met’s Cultural Property Initiative last year.

“The Met is committed to the responsible collecting of antiquities and to the shared stewardship of the world’s cultural heritage,” said Max Hollein, The Met’s Director and Chief Executive Officer. “We are honored to collaborate with the Republic of Iraq on the return of this sculpture, and we value the important relationships we have fostered with our colleagues there. We look forward to continuing the ongoing and open dialogue between us.”

About the Statue

Temples were the most important institutions in Mesopotamian cities of the Early Dynastic period (2900–2350 BCE). Each city had a patron deity, whose temple was built on a large platform and was visible for great distances in the flat countryside. The temple was literally a house for the god and a place of ritual, but it was also the most significant economic institution of the time, with large numbers of laborers to work its fields, produce goods for use in the temple, and trade with distant lands. Temple building had its own series of rituals, including purifying the ground on which the temple would stand and dedicating foundation deposits to the resident god. The figure of a nude man carrying a box on his head is a fine example of Sumerian sculpture in metal. Only certain categories of people were represented as nude in the Early Dynastic period: priests, athletes, mythological heroes, and prisoners of war. This figure, reminiscent of scenes depicting priests carrying offerings, carries an object that might be a temple foundation deposit or an offering related to its building.

The Met’s Cultural Property Initiative