Research perspectives on social media influencers and their followers

- Marissa Hayes Tarleton State University

Watkins, B. (Ed.). (2021). Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and Their Followers. Lexington Books.

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access ).

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Part of the PKP Publishing Services Network

Based at Tarleton State University in Stephenville, Texas, USA, The Journal of Social Media in Society is sponsored by the Colleges of Liberal and Fine Arts, Education, Business, and Graduate Studies.

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Politics & Social Sciences

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and their Followers Kindle Edition

Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and their Followers argues that the brands that find the most success on social media are the ones that acknowledge the real key to social media marketing—it’s all about the followers. This collection, edited by Brandi Watkins, explores how social media has shifted power dynamics away from brands and toward the consumers themselves—the social media users who choose to like, share, and engage with brands online. This dynamic has paved the way for the rise of the social media influencer (SMI); a unique category of social media user who has a large platform and compelling content that attracts a number of loyal and devoted followers.. It’s the followers that make SMI relevant and appealing to brands as a marketing strategy. Contributors discuss emerging trends in research related to the SMI and their followers; as the influencer marketing industry continues to grow and evolve, they argue, so too should our understanding of the influencer-follower relationship that makes this marketing strategy successful. Each chapter of this collection presents a variety of research perspectives, questions, and methodologies that can be used to analyze this trend. Scholars of media studies, communication, technology studies, celebrity studies, marketing, and economics will find this book particularly useful.

- Print length 250 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Lexington Books

- Publication date March 15, 2021

- File size 7620 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Not Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

Brandi Watkins is associate professor in the School of Communication and Digital Media at Virginia Tech.

Product details

- ASIN : B08XG58Q8G

- Publisher : Lexington Books (March 15, 2021)

- Publication date : March 15, 2021

- Language : English

- File size : 7620 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Not Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 250 pages

- Page numbers source ISBN : 1793613648

- #2,318 in Communication Reference (Kindle Store)

- #3,450 in Academic & Commercial Writing Reference

- #5,135 in Media Studies (Kindle Store)

About the author

Brandi watkins.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Next available on Sunday 2–10 p.m.

Additional Options

- smartphone Call / Text

- voice_chat Consultation Appointment

- place Visit

- email Email

Chat with a Specific library

- Business Library Offline

- College Library (Undergraduate) Offline

- Ebling Library (Health Sciences) Offline

- Gender and Women's Studies Librarian Offline

- Information School Library (Information Studies) Offline

- Law Library (Law) Offline

- Memorial Library (Humanities & Social Sciences) Offline

- MERIT Library (Education) Offline

- Steenbock Library (Agricultural & Life Sciences, Engineering) Offline

- Ask a Librarian Hours & Policy

- Library Research Tutorials

Search the for Website expand_more Articles Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more Catalog Explore books, music, movies, and more Databases Locate databases by title and description Journals Find journal titles UWDC Discover digital collections, images, sound recordings, and more Website Find information on spaces, staff, services, and more

Language website search.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

- ASK a Librarian

- Library by Appointment

- Locations & Hours

- Resources by Subject

book Catalog Search

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Available Online

- Print/Physical Items

- Limit to UW-Madison

- Advanced Search

- Browse by...

collections_bookmark Database Search

Find databases subscribed to by UW-Madison Libraries, searchable by title and description.

- Browse by Subject/Type

- Introductory Databases

- Top 10 Databases

article Journal Search

Find journal titles available online and in print.

- Browse by Subject / Title

- Citation Search

description Article Search

Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

- Scholarly (peer-reviewed)

- Open Access

- Library Databases

collections UW Digital Collections Search

Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW Digital Collections Center .

- Browse Collections

- Browse UWDC Items

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Email/Calendar

- Google Apps

- Loans & Requests

- Poster Printing

- Account Details

- Archives and Special Collections Requests

- Library Room Reservations

Search the UW-Madison Libraries

Catalog search.

Research perspectives on social media influencers and their followers

"This book analyzes social media influencers and their relationship with their online followers. Each chapter represents a unique theoretical and methodological approach to examining the importance...

"This book analyzes social media influencers and their relationship with their online followers. Each chapter represents a unique theoretical and methodological approach to examining the importance of this relationship from a variety of perspectives and contexts"--

- toc Request Options

- format_quote Citation

Physical Locations

Publication details.

- Watkins, Brandi, editor

- Lanham, Maryland : Lexington Books, an imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., [2021]

- xii, 235 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm

- Includes bibliographical references and index.

- Introduction / Brandi Watkins -- The science of social media influencer marketing / Kelli S. Burns -- #FitnessGoals and brands on Instagram: influencers and digital dialogic communication / Alison N. Novak -- #MarketingFaith: the megachurch pastor as social media influencer / Elizabeth B. Jones, Sydney O. Scheller, and Nathan A. Vick -- Become an #AcademicInfluencer: a blueprint for building bridges between the classroom and industry / Carolyn Kim, Karen Freberg, Mitchell Friedman, and Amanda J. Weed -- Social media influencers in Africa: an analysis of Instagram content and brand endorsements / Anne W. Njathi and Nicole M. Lee -- It's a whole new world: the impact of social media influencers on Type 1 diabetics' attitudes about, and behaviors regarding, insulin pump therapy / Corey Jay Liberman -- You "can't put concealer on this one": crisis management in an influencer context / Chelsea Woods -- Ethical responsibilities for social media influencers / Jenn Burleson Mackay -- The case of Dina Tokio: using symbolic theory to understand the backlash / JoAnna Boudreaux -- Connecting via social media for weight loss: an exploration of social media influencers in a weight-loss community / Carrie S. Trimble and Nancy J. Curtin -- Influenced by My Lifestyle net idols (#Contentcreators): exploring the relationships between Thai net idols and followers / Vimviriya Limkangvanmongkol

- Online social networks.

- Social media -- Influence.

- Social influence.

Items Related By Call Number

Additional information, information from the web, library staff details, keyboard shortcuts, available anywhere, available in search results.

- Browse by Subjects

- New Releases

- Coming Soon

- Chases's Calendar

- Browse by Course

- Instructor's Copies

- Monographs & Research

- Intelligence & Security

- Library Services

- Business & Leadership

- Museum Studies

- Pastoral Resources

- Psychotherapy

Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and their Followers

Edited by brandi watkins - contributions by kelli s. burns; joanna boudreaux; nancy j. curtin; karen freberg; mitchell friedman; elizabeth b. jones; carolyn kim; nicole m. lee; corey jay liberman; vimviriya limkangvanmongkol; jenn burleson mackay; wangari njathi; alison n. novak; sydney o. scheller; carrie s. trimble; nathan vick; amanda j. weed and chelsea woods.

Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and their Followers argues that the brands that find the most success on social media are the ones that acknowledge the real key to social media marketing—it’s all about the followers. This collection, edited by Brandi Watkins, explores how social media has shifted power dynamics away from brands and toward the consumers themselves—the social media users who choose to like, share, and engage with brands online. This dynamic has paved the way for the rise of the social media influencer (SMI); a unique category of social media user who has a large platform and compelling content that attracts a number of loyal and devoted followers.. It’s the followers that make SMI relevant and appealing to brands as a marketing strategy. Contributors discuss emerging trends in research related to the SMI and their followers; as the influencer marketing industry continues to grow and evolve, they argue, so too should our understanding of the influencer-follower relationship that makes this marketing strategy successful. Each chapter of this collection presents a variety of research perspectives, questions, and methodologies that can be used to analyze this trend. Scholars of media studies, communication, technology studies, celebrity studies, marketing, and economics will find this book particularly useful.

ALSO AVAILABLE

Research Perspectives on Social Media Influencers and Brand Communication

November 30, 2020

- Brandi Watkins

- Communication Books

- Faculty Bookshelf

What Do We Know About Influencers on Social Media? Toward a New Conceptualization and Classification of Influencers

- First Online: 26 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- María Sicilia 2 &

- Manuela López 2

3014 Accesses

3 Citations

The arrival of influencers has modified marketing budgets all over the world, being used more and more often as a new marketing tool. Given the importance of the influencer phenomenon, many studies have been published about this topic in the previous years. However, there are still several areas that need further research. One of these areas is the conceptualization of influencers. The influencer phenomenon is dynamic, so what was understood as an influencer ten years ago may have evolved and changed. Additionally, classifications based on the number of followers may be easily manipulated, so there is need for an improved classification of influencers based on their potential reach. Following this criterion, the authors propose to classify influencers as mega-reach, macro-reach, medium-reach, and mini-reach influencers. Moreover, the numerous factors that may determine their influence are still not well accounted for nor organized. Finally, most studies have analyzed the success of influencers as a new marketing tool, but the way influencers collaborate with brands is very special and has also evolved recently. This chapter contributes to previous literature by proposing a renewed definition and classification of influencers that is more consistent with their origin, evolution, and progressive level of professionalization, as well as by identifying several research gaps that may guide future research.

- Potential reach

- Interactivity

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (4), 411–454.

Article Google Scholar

Al-Emadi, F. A., & Yahia, I. B. (2020). Ordinary celebrities related criteria to harvest fame and influence on social media. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing., 14 (2), 195–213.

Araujo, T., Neijens, P., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Getting the word out on Twitter: The role of influentials, information brokers and strong ties in building word-of-mouth for brands. International Journal of Advertising, 36 (3), 496–513.

Balaban, D. C., & Szambolics, J. (2022). A proposed model of self-perceived authenticity of social media influencers. Media and Communication, 10 (1), 235–246.

Berthon, P., Pitt, L., & Watson, R. T. (1996). Re-surfing W3: Research perspectives on marketing communication and buyer behavior on the worldwide web. International Journal of Advertising, 15 (9), 287–301.

Bi, N. C., & Zhang, R. (2022). I will buy what my ‘friend’ recommends: The effects of parasocial relationships, influencer credibility and self-esteem on purchase intentions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Ahead-of-Print, . https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-08-2021-0214

Boerman, S. C. (2020). The effects of the standardized Instagram disclosure for micro-and meso-influencers. Computers in Human Behavior, 103 , 199–207.

Boerman, S. C., & Müller, C. M. (2021). Understanding which cues people use to identify influencer marketing on Instagram: An eye tracking study and experiment. International Journal of Advertising , 1–24.

Google Scholar

Boerman, S. C., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2020). Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: The moderating role of para-social relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 3042.

Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., & Van Der Aa, E. P. (2017). “This post is sponsored”: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38 , 82–92.

Bu, Y., Parkinson, J., & Thaichon, P. (2022). Influencer marketing: Homophily, customer value co-creation behaviour and purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 66 , 102904.

Burns, K. (2021). The history of social media influencers in research perspectives on social media influencers and brand communication (B. Watkins, Ed., pp. 1–21). Lexington Books .

Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63 (4), 469–479.

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117 , 510–519.

Chae, J. (2017). Explaining females’ envy toward social media influencers. Media Psychology, 21 (2), 246–262.

Chen, T. Y., Yeh, T. L., & Lee, F. Y. (2021). The impact of Internet celebrity characteristics on followers’ impulse purchase behavior: The mediation of attachment and parasocial interaction. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15 (3), 483–501.

Corrêa, S. C. H., Soares, J. L., Christino, J. M. M., Gosling, M. D. S., & Gonçalves, C. A. (2020). The influence of YouTubers on followers’ use intention. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 14 (2), 173–194.

Cresci, S., Di Pietro, R., Petrocchi, M., Spognardi, A., & Tesconi, M. (2015). Fame for sale: Efficient detection of fake Twitter followers. Decision Support Systems, 80 , 56–71.

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36 (5), 798–828.

De Veirman, M., Hudders, L., & Nelson, M. R. (2019). What is influencer marketing and how does it target children? A review and direction for future research. Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 2685.

De Veirman, M., & Hudders, L. (2020). Disclosing sponsored Instagram posts: The role of material connection with the brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. International Journal of Advertising , 39 (1), 94–130.

Delbaere, M., Michael, B., & Phillips, B. J. (2021). Social media influencers: A route to brand engagement for their followers. Psychology & Marketing, 38 (1), 101–112.

Dhanesh, G. S., & Duthler, G. (2019). Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relations Review, 45 (3), 101765.

Dinh, T. C. T., & Lee, Y. (2021). I want to be as trendy as influencers”–how “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, in press.

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68 , 1–7.

EASA. (2018). EASA best practice recommendation on influencer marketing . https://www.easa-alliance.org/sites/default/files/BEST%20PRACTICE%20RECOMMENDATION%20ON%20INFLUENCER%20MARKETING%20GUIDANCE_v2022.pdf (last accessed 5/3/2022).

Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2009). Connecting with celebrities: Celebrity endorsement, brand meaning, and self-brand connections. Journal of Marketing Research, 13 (3), 339–348.

Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17 (2), 138–149.

Farivar, S., Wang, F., & Yuan, Y. (2021). Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: Key factors in influencer marketing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59 , 102371.

Fazli-Salehi, R., Jahangard, M., Torres, I. M., Madadi, R., & Zúñiga, M. Á. (2022). Social media reviewing channels: The role of channel interactivity and vloggers’ self-disclosure in consumers’ parasocial interaction. Journal of Consumer Marketing . https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-06-2020-3866

Fink, M., Koller, M., Gartner, J., Floh, A., & Harms, R. (2020). Effective entrepreneurial marketing on Facebook–A longitudinal study. Journal of Business Research, 113 , 149–157.

Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review , 37 (1), 90–92.

FTC. (2022). Soliciting and paying for online reviews: A guide for marketers . https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/advertising-and-marketing/endorsements%2C-influencers%2C-and-reviews

Ge, J., & Gretzel, U. (2018). Emoji rhetoric: A social media influencer perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 34 (15–16), 1272–1295.

Gerrath, M. H., & Usrey, B. (2021). The impact of influencer motives and commonness perceptions on follower reactions toward incentivized reviews. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38 (3), 531–548.

Girgin, B. A. (2021). Ranking influencers of social networks by semantic kernels and sentiment information. Expert Systems with Applications, 171 , 114599.

Gómez, A. R. (2019). Digital Fame and Fortune in the age of social media: A Classification of social media influencers. aDResearch: Revista Internacional de Investigación en Comunicación (19), 8–29.

Haenlein, M., Anadol, E., Farnsworth, T., Hugo, H., Hunichen, J., & Welte, D. (2020). Navigating the new era of influencer marketing: How to be successful on instagram, tikTok, & Co. California Management Review , 63 (1), 5–25.

Hashtagsforlikes. (2020). Instagram followers: How many does the average person have? www.hashtagsforlikes.co

Herhausen, D., Ludwig, S., Grewal, D., Wulf, J., & Schoegel, M. (2019). Detecting, preventing, and mitigating online firestorms in brand communities. Journal of Marketing, 83 (3), 1–21.

Hinz, O., Skiera, B., Barrot, C., & Becker, J. U. (2011). Seeding strategies for viral marketing: An empirical comparison. Journal of Marketing, 75 (6), 55–71.

Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40 (3), 327–375.

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83 (5), 78–96.

Influencer Marketing Hub. (2019). Instagram testing creators accounts . https://influencermarketinghub.com/instagram-creators-accounts/

Influencer Marketing Hub. (2022). The state of influencer marketing in 2022: A benchmark report . https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/

Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43 (2), 181–195.

Jin, S. V., Muqaddam, A., & Ryu, E. (2019). Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning., 37 (5), 567–579.

Johnstone, L., & Lindh, C. (2018). The sustainability-age dilemma: A theory of (un) planned behaviour via influencers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17 (1), e127–e139.

Ki, C. W. C., & Kim, Y. K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36 (10), 905–922.

Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H.-Y. (2022). Social media influencers as human brands: An interactive marketing perspective. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Ahead-of-Print . https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-08-2021-0200

Ladhari, R., Massa, E., & Skandrani, H. (2020). YouTube vloggers’ popularity and influence: The roles of homophily, emotional attachment, and expertise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54 , 102027.

Lee, J. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2021). Perceived authenticity of social media influencers: Scale development and validation. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15 (4), 822–841.

Lee, J. E., & Watkins, B. (2016). YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 69 (12), 5753–5760.

Leite, F. P., & de Paula Baptista, P. (2021). Influencers’ intimate self-disclosure and its impact on consumers’ self-brand connections: Scale development, validation, and application. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing , in press.

Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50 , 226–251.

Lin, H. C., Bruning, P. F., & Swarna, H. (2018). Using online opinion leaders to promote the hedonic and utilitarian value of products and services. Business Horizons, 61 (3), 431–442.

Lokithasan, K., Simon, S., Jasmin, N. Z. B., & Othman, N. A. B. (2019). Male and female social media influencers: The impact of gender on emerging adults. International Journal of Modern Trends in Social Sciences, 2 (9), 21–30.

López, M., & Sicilia, M. (2014a). Determinants of E-WOM influence: The role of consumers’ internet experience. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 9 (1), 28–43.

López, M., & Sicilia, M. (2014b). eWOM as source of influence: The impact of participation in eWOM and perceived source trustworthiness on decision making. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 14 (2), 86–97.

López, M., Sicilia, M., & Verlegh, P. W. (2022). How to motivate opinion leaders to spread e-WoM on social media: Monetary vs non-monetary incentives. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16 (1), 154–171.

López-Barceló, A., & López, M. (2022). Influencers’ promoted posts and stories on Instagram: Do they matter? Journal of Innovations in Digital Marketing, 3 (1), 12–26.

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19 (1), 58–73.

Lou, C. (2021). Social media influencers and followers: Theorization of a trans-parasocial relation and explication of its implications for influencer advertising. Journal of Advertising , 1–18.

Lou, C., & Kim, H. K. (2019). Fancying the new rich and famous? Explicating the roles of influencer content, credibility, and parental mediation in adolescents’ parasocial relationship, materialism, and purchase intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 2567.

Mete, M. (2021). A study on the impact of personality traits on attitudes towards social media influencers. Multidisciplinary Business Review , 14 (2).

Monge-Benito, S., Elorriaga-Illera, A., Jiménez-Iglesias, E., & Olabarri-Fernández, E. (2021). Advertising disclosure and content creation strategies of Spanish-speaking instagrammers: Case study of 45 profiles. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico, 27 (4), 1151–1162.

Olsenmetrix. (2020). The history of influencer marketing . https://olsenmetrix.com/views/the-history-of-influencer-marketing/

Ouvrein, G., Pabian, S., Giles, D., Hudders, L., & De Backer, C. (2021). The web of influencers. A marketing-audience classification of (potential) social media influencers. Journal of Marketing Management , 37 (13–14), 1313–1342.

Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1998). Matching versus mismatching attitude functions: Implications for scrutiny of persuasive messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24 (3), 227–240.

Pöyry, E., Pelkonen, M., Naumanen, E., & Laaksonen, S. M. (2019). A call for authenticity: Audience responses to social media influencer endorsements in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13 (4), 336–351.

Riboldazzi, S. & Capriello, A. (2020). Identifying and selecting the right influencers in the digital era. In Influencer marketing (pp. 43–58). Routledge.

Rogers, E. M., & Cartano, D. G. (1962). Methods of measuring opinion leadership. Public Opinion Quarterly , 435–441.

Rosengren, S., Eisend, M., Koslow, S., & Dahlen, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of when and how advertising creativity works. Journal of Marketing, 84 (6), 39–56.

Safko, L. (2014). The social media bible: Tactics, tools, and strategies for business success . John Wiley & Sons.

Sakib, M. N., Zolfagharian, M., & Yazdanparast, A. (2020). Does parasocial interaction with weight loss vloggers affect compliance? The role of vlogger characteristics, consumer readiness, and health consciousness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52 , 101733.

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39 (2), 258–281.

Shen, Z. (2021). A persuasive eWOM model for increasing consumer engagement on social media: Evidence from Irish fashion micro-influencers. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15 (2), 181–199.

Sicilia, M., Ruiz, S., & Munuera, J. L. (2005). Effects of interactivity in a web site: The moderating effect of need for cognition. Journal of Advertising , 34 (3), 31–44.

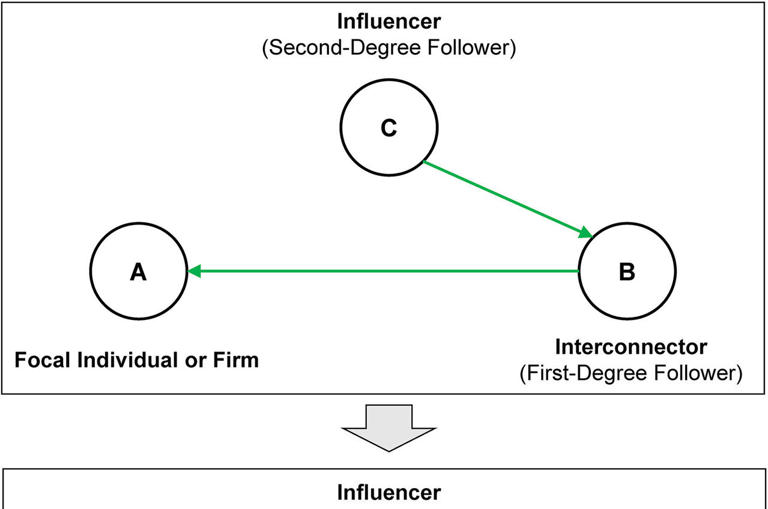

Sicilia, M., Palazón, M., & López, M. (2020). Intentional vs. unintentional influences of social media friends. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications , 42 , 100979.

Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53.

Statista. (2021). Influencer Marketing . https://www.statista.com/topics/2496/influence-marketing

Taillon, B. J., Mueller, S. M., Kowalczyk, C. M., & Jones, D. N. (2020). Understanding the relationships between social media influencers and their followers: The moderating role of closeness. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29 (6), 767–782.

Taylor, C. R. (2020). The urgent need for more research on influencer marketing. International Journal of Advertising, 39 (7), 889–891.

Tiggemann, M., & Anderberg, I. (2020). Muscles and bare chests on Instagram: The effect of Influencers’ fashion and fitspiration images on men’s body image. Body Image, 35 , 237–244.

Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencers endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology & Marketing, 36 , 1267–1276.

Uribe, R., Buzeta, C., & Velásquez, M. (2016). Sidedness, commercial intent and expertise in blog advertising. Journal of Business Research, 69 (10), 4403–4410.

Uzunoğlu, E., & Kip, S. M. (2014). Brand communication through digital influencers: Leveraging blogger engagement. International Journal of Information Management, 34 (5), 592–602.

Van Driel, L., & Dumitrica, D. (2021). Selling brands while staying “Authentic”: The professionalization of Instagram influencers. Convergence, 27 (1), 66–84.

Van Reijmersdal, E. A., Rozendaal, E., Hudders, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Cauberghe, V., & Van Berlo, Z. M. (2020). Effects of disclosing influencer marketing in videos: An eye tracking study among children in early adolescence. Journal of Interactive Marketing , 49 (1), 94–106.

Vrontis, D., Makrides, A., Christofi, M., & Thrassou, A. (2021). Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45 (4), 617–644.

Wang, C. L. (2021). New frontiers and future directions in interactive marketing: Inaugural Editorial. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15 (1), 1–9.

Wang, E. S. T., & Hu, F. T. (2022). Influence of self-disclosure of Internet celebrities on normative commitment: The mediating role of para-social interaction. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16 (2), 292–309.

Wellman, M. L., Stoldt, R., Tully, M., & Ekdale, B. (2020). Ethics of authenticity: Social media influencers and the production of sponsored content. Journal of Media Ethics, 35 (2), 68–82.

Xiao, M., Wang, R., & Chan-Olmsted, S. (2018). Factors affecting YouTube influencer marketing credibility: A heuristic-systematic model. Journal of Media Business Studies, 15 (3), 188–213.

Yuan, S., & Lou, C. (2020). How social media influencers foster relationships with followers: The roles of source credibility and fairness in parasocial relationship and product interest. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 20 (2), 133–147.

Zhou, S., Blazquez, M., McCormick, H., & Barnes, L. (2021). How social media influencers’ narrative strategies benefit cultivating influencer marketing: Tackling issues of cultural barriers, commercialised content, and sponsorship disclosure. Journal of Business Research, 134 , 122–142.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

María Sicilia & Manuela López

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to María Sicilia .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of New Haven, West Haven, CT, USA

Cheng Lu Wang

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Sicilia, M., López, M. (2023). What Do We Know About Influencers on Social Media? Toward a New Conceptualization and Classification of Influencers. In: Wang, C.L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_26

Published : 26 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-14960-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-14961-0

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Rise of Social Media Influencers as a New Marketing Channel: Focusing on the Roles of Psychological Well-Being and Perceived Social Responsibility among Consumers

1 Department of Integrated Strategic Communication, College of Communication and Information, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA; [email protected]

Minseong Kim

2 Department of Management & Marketing, College of Business, Louisiana State University Shreveport, Shreveport, LA 71115, USA

Associated Data

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

This empirical research investigated the structural relationships between social media influencer attributes, perceived friendship, psychological well-being, loyalty, and perceived social responsibility of influencers, focusing on the perspective of social media users. More specifically, this study conceptually identified social media influencer attributes such as language similarity, interest similarity, interaction frequency, and self-disclosure and examined the respective effects of each dimension on perceived friendship and psychological well-being, consequently resulting in loyalty toward social media influencers. The authors collected and analyzed data from 388 social media users in the United States via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk with multivariate analyses to test the hypothesized associations among the variables in this study. The findings indicated that perceived friendship was significantly influenced by language similarity, interest similarity, and self-disclosure, but did not have a significant impact on psychological well-being. Additionally, perceived friendship significantly affected psychological well-being and loyalty, and psychological well-being significantly influenced loyalty. Lastly, social media influencers’ social responsibility moderated the path from psychological well-being to loyalty. Based on these findings, this study proposes theoretical and managerial implications for the social media influencer marketing context.

1. Introduction

Social media use is widespread and has been shown to play an important role in the lives of both adolescents and young adults [ 1 ]. Social media platforms enable adolescents and young adults to consume digital content without time and space limits and to virtually interact with other users without geographical boundaries [ 2 ]. Particularly, the development of digital platforms leads young adults to closely interact with their favorite celebrities, brands, and other users in the virtual world via two-way communication tools, such as live chats and comment options [ 3 ]. Interestingly, as social media platforms have grown, the digital world created a new phrase, “social media influencers,” who become famous through their digital content on social media, compared to traditional celebrities who become famous on TV shows and film [ 4 ]. Hence, social media users tend to feel connected with social media influencers by interacting with them in the virtual world and perceive social media influencers as more authentic in their fields, including fashion, health, or music, than celebrity endorsements in traditional advertisements [ 1 ]. Therefore, there is a need to empirically investigate what drives social media users’ loyalty toward their favorite influencers, such as repeat purchase behavior, positive word-of-mouth, and recommendation of products advertised by social media influencers from the perspectives of an influencer’s digitalized attributes [ 5 , 6 ]. These perspectives are especially important because social media users interact with their favorite influencers in the digital world instead of in the real world. This means that social media influencers’ digitalized attributes can be more important determinants of users’ perceptions, feelings, behavioral intention, and even actual behaviors than the visual characteristics of social media influencers. However, prior research in this field focused primarily on the visual and/or actual characteristics of social media influencers (e.g., physical attractiveness or social attractiveness) to predict marketing outcomes, such as positive attitudes toward and favorable intention for a product advertised by the influencers [ 7 ]. In particular, loyalty toward social media influencers leads followers to have a strong sense of product/brand association and reality by perceiving influencers’ product/brand and advertisements as more persuasive and authentic [ 4 ]. Accordingly, users are more likely to behave favorably for the product/brand social media influencers advertise in order to endorse the influencers and support the influencers’ fame and social status [ 7 ].

Specifically, this study considers psychological well-being as one of the core determinants of social media users’ loyalty toward their favorite influencers by focusing on the fundamental motivations of consuming digital content among users, such as enjoyment, pleasure, happiness, and friendship [ 6 ]. For example, according to Kim and Kim [ 3 ], social media platforms provide users with virtual spaces to consume celebrities’ digital content and interact with social media influencers and other users in the social media community, leading users to form positive emotions in the digital world that transfer to happiness and pleasure in the real world. Accordingly, this study draws from the parasocial interaction, the self-congruity, and the psychological well-being theories to propose that social media users develop perceived friendships with their favorite influencers in the virtual world by consuming the influencers’ digital content and interacting with the influencers, resulting in the development of psychological well-being among users in the real world [ 7 ]. More specifically, the digitalized interactive features of social media platforms enable users to feel emotionally tied to their favorite social media influencers (i.e., users perceive the influencers as intimate friends in the real world via virtual interactions), including social foci, proximity, interaction frequency, and self-disclosure [ 3 , 8 ]. Through the social media features, users tend to feel like they develop a solid friendship with their favorite social media influencers and to be satisfied with their real life [ 7 , 8 ]. Therefore, based on the parasocial interaction theory and prior studies on social media [ 3 , 7 , 9 ], this study identifies language similarity, interest similarity, interaction frequency, and self-disclosure as social media influencer attributes that serve as core determinants of users’ perceived friendship with their favorite social media influencers and psychological well-being in real life.

Importantly, in the social media influencer marketing context, consumers develop their own beliefs regarding why their favorite influencers promote and advertise a product/brand and whether the influencers as well as the product/brand are socially acceptable or not. Social media users may be skeptical about socially unacceptable brands even though their favorite influencers have a strong partnership with the brands, and vice versa [ 10 ]. Nowadays, media coverage has reported that social media influencers have created digital content without ethical standards, and media coverage has disclosed socially unacceptable scandals of social media influencers [ 10 , 11 ]. Social media influencers’ wrongdoing or deviance has created spillover effects on brands and/or products that have partnerships with the social media influencers [ 10 ]. Therefore, users’ perceived social responsibility of social media influencers needs to be studied as a moderator in the context of social media influencer marketing. Some brands have partnerships with social media influencers based on the influencers’ number of loyal followers without consideration of the influencers’ socially responsible aspects. Based on the notion of the spillover effect, this study assumes that the social values and socially responsible behaviors of social media influencers, such as money and time donations for people in need and support for nonprofit organizations, have significantly influenced their followers’ and other users’ perceptions about the influencers and digital content (i.e., including advertisements) [ 12 ]. To the best of our knowledge, although social media users’ perceived social responsibility has been well-studied from the perspective of brands or companies [ 13 ], no empirical research has been conducted from the perspective of users’ perceived social responsibility of social media influencers playing a role as brand ambassadors and advertising agencies in social media, such as a spokesperson.

In conclusion, this study investigates the distinct effects of social media influencer attributes on users’ perceived friendships with their favorite social media influencers and psychological well-being, consequently resulting in loyalty toward the influencers and advertised products. More importantly, this research examines the moderating role of users’ perceived social responsibility of their favorite social media influencers in the relationships between perceived friendship/psychological well-being and loyalty. From a theoretical perspective, this empirical research contributes to the existing literature on social media influencer marketing by extending the parasocial interaction theory considering the digitalized attributes of social media influencers compared to previous studies that emphasized influencers’ visual attributes [ 7 ]. Additionally, this research extends the parasocial interaction theory by considering the roles of the perceived social responsibility of social media influencers and psychological well-being among digital users, reflecting the current trend in the marketing field (i.e., the importance of social responsibility and psychological well-being in the era of COVID-19) [ 3 , 6 ]. From a managerial standpoint, this study proposes the important role of social media influencers’ social responsibility in formulating a partnership between a brand (or company) and the influencers.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. the parasocial interaction theory as a theoretical backgroud.

The parasocial interaction theory was developed from the perspectives of developing relationships between spectators and mass media, such as television and radio [ 14 ]. As an illusionary experience, the parasocial interaction is based on the notion that spectators perceive that media-mediated representations on mass media, such as characters, celebrities, or presenters, are talking directly to them, engaging in reciprocal relationships [ 15 ]. After perceiving it, spectators begin to consider media-mediated representators as their real friends according to the representators’ nonverbal and verbal interaction cues on mass media [ 16 , 17 ]. If the indirect interactions between spectators and representators continue, spectators’ feelings about friendships with the representators can be enduring and strengthened [ 18 ].

The parasocial interaction theory has been applied to computer-mediated environments that bring users closer to a computer-mediated person via communication tools [ 16 ]. More specifically, computer-mediated environments provide users with direct two-way communications between users and/or between a user and a celebrity/influencer, generating virtual interactions to enable the user to view the celebrity/influencer as a real friend [ 19 ]. Additionally, consistent with the components of traditional mass media, social media users use verbal and nonverbal cues of influencers to foster parasocial interactions [ 3 ]. More specifically, social media influencers may use digitalized verbal and nonverbal cues by demonstrating similar language styles and similar interests as their followers to facilitate a feeling of psychological proximity, leading the followers to develop a parasocial relationship with the influencers [ 19 ]. Additionally, social media users who directly and indirectly interact with their favorite influencers more frequently tend to report a strong feeling of parasocial relationships with the influencers. This is primarily because users feel like the interactions with the influencers on social media are ordinary meetings with real friends, according to the notion of the parasocial interaction theory [ 16 ]. Interestingly, as social media users are exposed to their favorite influencers’ personal stories over time, they form beliefs and opinions about the influencers by developing parasocial relationships with the influencers in the virtual world, similar to in the real world [ 9 ]. Therefore, this study proposes language similarity, interest similarity, interaction frequency, and self-disclosure as verbal and nonverbal cues of influencers (i.e., social media influencer attributes in this study) [ 3 , 9 ].

2.2. Social Media Influencer Attributes

In this study, similarities between social media users and influencers regarding personality, values, or beliefs are referred to as self-congruity based on the self-congruity theory that explains how social media users select their favorite influencers [ 3 , 9 ]. According to the self-congruity theory, social media users select and consume their favorite influencers’ digital content consistent with their self-concepts [ 20 ]. This study proposes that social media users’ perceived consistency with images of influencers is based on the sources of self-congruity, such as perceived similar language styles and messages the influencers use to communicate with social media followers and spectators [ 20 , 21 ]. For example, perceived language similarity can be formed by communication styles, phrases, and words between social media users and influencers, and perceived interest similarity can be formed by influencers’ digital content [ 21 ]. In particular, the social media influencers’ digital content can create more opportunities for disclosing personal information with other users if the digital content is more frequently uploaded and updated [ 3 , 22 ]. Thus, social media users have more opportunities to interact with their favorite influencers and learn more about their favorite influencers’ images over time [ 23 ]. Lastly, social media users’ perceived images of their favorite influencers can also be influenced by the influencers’ personal thoughts, information, and feelings intentionally shared with the users on social media [ 22 , 23 ]. The shared personal information results in users’ perceived intimacy with the influencers, strong connections and emotional exchanges [ 3 , 9 ].

2.3. Perceived Friendship

In consumer behavior, the concept of friendship has been considered to be a close relationship between service providers and consumers [ 24 , 25 ]. Additionally, consumers’ perceptions of friendship can be formed by a close relationship with intangible things, such as brands and digitalized content, via interpersonal interactions on social media [ 9 , 26 ]. However, the interpersonal interactions between users on social media should be based on inclusion, loyalty, reciprocity, mutual trust, and intimacy and care between the users [ 24 ]. Due to the components of interpersonal interactions, social media users develop and maintain friendships with other users by reducing limitations of the virtual world, such as uncertainty, intangibility, and complexity [ 3 ]. In addition, for interpersonal purposes, users can employ particular tools of social media platforms, including clicking the like and share buttons and leaving comments on others’ posts, leading users to feel like they are interacting with real friends in the virtual world [ 3 , 25 , 26 ]. Therefore, social media platform tools serve as a full mediator of building a perceived friendship between users in the virtual world [ 26 ].

2.4. Psychological Well-Being

In general, psychological well-being refers to life satisfaction and fulfillment, including individuals’ emotional reactions to both short moments and long periods of time [ 27 , 28 ]. The psychological well-being theory assumes that the short moments and long periods of time should fulfill individuals’ social, psychological, and physical needs to maintain a high level of psychological well-being [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Interestingly, the extant literature indicates the positive relationship between psychological well-being and the use of social media platforms, such as digital content consumption and virtual interactions with others on social media, by highlighting that it increases individuals’ feelings of belonging and provides individuals with confidence in life [ 27 , 28 , 30 ]. Therefore, social media platforms have the potential to meet users’ social, psychological, leisure, and even physical needs, increasing their level of psychological well-being [ 30 ]. However, heavy social media users may often displace social activities in the real world by being addicted to social media use, focusing on maintaining their life satisfaction primarily via digital activities [ 30 ]. In addition, although heavy social media users can maintain their psychological well-being, excessive digital activities may generate detrimental effects on users’ physical health, such as body composition and quality of sleep [ 29 ]. Thus, heavy digital media use may result in deleterious consequences for social media users.

2.5. Loyalty

On social media, user loyalty refers to influencers’ ability to keep users consuming digital content created by the influencers over other influencers [ 32 , 33 ]. Hence, social media user loyalty can be displayed as primarily consuming the influencers’ digital content, although there are many alternatives who create digital content similar to that of their favorite influencer [ 34 ]. Social media user loyalty also tends to be expressed as positive word-of-mouth and recommendation of the influencer to other users [ 33 ]. In other words, users who are loyal toward a particular influencer are more likely to play a role as an active advocator or supporter for the influencer in the real world as well as in the virtual world [ 34 ]. Interestingly, social media user loyalty toward favorite influencers consequently leads to users’ favorable behaviors for products/services the influencer advertises and promotes, including purchase behavior, positive word-of-mouth, and recommendation of the products/services to relatives, friends, and others on social media [ 33 , 35 ]. The users tend to commit a substantial amount of money and time to the products/services without reservation only because their favorite influencer advertises and promotes the products/services [ 35 ]. Therefore, it is especially important for social media influencers to build user loyalty by retaining their followers and spectators on a long-term basis, bringing the influencers reputation and profitability [ 32 , 33 ].

2.6. Research Hypotheses

According to the social media literature, users are more likely to develop and maintain strong relationships with others who have similar interests [ 3 , 5 ]. Within the virtual world, perceived similarity enables users to mitigate potential conflicts and misunderstandings of other users when building relationships on social media [ 36 ]. Additionally, social media users are more likely to communicate with others more frequently and effectively if they have the same language styles and interests in particular topics, including between a user and a user and between a user and a social media influencer [ 3 , 5 , 36 ]. More importantly, on social media platforms, users’ similarity with others can also be perceived by user-generated digital content that includes language and communication style in addition to physical similarity (e.g., location and gender) [ 9 , 37 ]. Furthermore, social media platforms provide influencers with enough space and storage to offer digital content to other users without time and space limits [ 2 , 37 ]. Thus, social media users can always consume their favorite influencers’ digital content and interact with them, leading them to develop friendships between users and influencers via frequent interactions [ 3 ]. Additionally, influencers who reveal personal interests, thoughts, and beliefs to users on social media may form an intimacy and emotional reliance [ 37 ]. Therefore, this study argues that digital content and attributes, including influencers’ characteristics, may lead social media users to develop and maintain close relationships with the influencers, such as with a good friendship. Accordingly, this study formulates the following research hypothesis:

Social media users’ perception of language similarity in communication with their favorite influencer is positively associated with perceived friendship with the influencer.

Social media users’ perception of interest similar to their favorite influencer is positively associated with perceived friendship with the influencer.

Social media users’ perception of interaction frequency with their favorite influencer is positively associated with perceived friendship with the influencer.

Social media users’ perception of self-disclosure of influencer-related information is positively associated with perceived friendship with the influencer.

One of the most powerful drivers of social media users’ digital content consumption behavior is to bring them pleasure, happiness, and enjoyment [ 6 , 7 ]. For example, if the digital content created by social media influencers is not able to fulfill social media users’ hedonic motivation, it may generate negative influences on users’ emotional and mental states, such as unhappiness [ 3 ]. In addition, social media users are likely to enjoy interacting with their favorite influencers on social media platforms and consuming the influencers’ digital content to escape from everyday life and/or relieve boredom [ 38 , 39 ]. The virtual interactions with social media influencers lead users to feel like they spend time with close friends with the same communication style and interests in the virtual world [ 40 ]. Additionally, social media platforms enable users to easily communicate with their favorite influencers and consume the influencers’ digital content regarding personal facts and stories [ 9 ]. Discussing influencers’ personal facts and stories leads social media users to feel happy as they perceive the influencers as close friends, contributing to their psychological well-being in the real world [ 3 , 40 ]. Based on that, the current research proposes the following hypothesis:

Social media users’ perception of language similarity in communication with their favorite influencer is positively associated with psychological well-being.

Social media users’ perception of interest similar to their favorite influencer is positively associated with psychological well-being.

Social media users’ perception of interaction frequency with their favorite influencer is positively associated with psychological well-being.

Social media users’ perception of self-disclosure of influencer-related information is positively associated with psychological well-being.

In general, good friendships between individuals result in each party’s psychological well-being as well as life satisfaction [ 3 ]. From a psychological perspective, the theory of human flourishing assumes that individuals attempt to build and maintain close relationships with others by continuously interacting with them in order to enhance their psychological well-being [ 41 ]. In other words, social media users are likely to enjoy life satisfaction and feel happier in the real world when perceiving that they succeed in developing and maintaining close relationships with their favorite influencers even though the relationship exists only in the virtual world [ 38 , 42 ]. Accordingly, social media users are more likely to interact with their favorite influencers in the virtual world to develop perceived close relationships or friendships with the influencers, leading users to emotionally reduce work and/or life stress [ 38 , 39 ]. Social media users’ perceived friendship with their favorite influencers established by virtual interactions on social media serves as a significant driver of developing a feeling of psychological well-being in their daily life [ 3 ]. Based on this notion, the following research hypothesis is established:

Social media users’ perceived friendship with their favorite influencer is positively associated with psychological well-being.

In the consumer behavior fields, consumers’ perceived friendships with a particular brand or company become a significant driver of their reciprocity, re-patronage, and loyalty toward the brand [ 43 , 44 ]. This is primarily because the relationship between a consumer and a brand leads the consumer to devalue other brands and forgive the brand’s service failure as the consumer perceives and deals with the brand as a close friend [ 9 , 45 ]. As a result, the consumer is more likely to be behaviorally loyal toward the brand by maintaining a good friendship with it via continuously purchasing and using its products/services [ 9 , 43 , 45 ]. In addition, individuals’ perceived friendships with an object could be expressed as their levels of passion about, trust or dependence toward, commitment to, and self-connection with the object, resulting in favorable behaviors toward the object [ 3 , 44 ]. Accordingly, this study proposes that social media users can build a close relationship with their favorite influencers via aggregated virtual interactions on social media into overall loyalty toward the influencers and products/services advertised and promoted by the influencers on social media. Therefore, this study formulates the following research hypothesis:

Social media users’ perceived friendship with their favorite influencer is positively associated with loyalty toward the influencer.

In general, individuals are likely to form a sense of happiness when remembering and/or experiencing a particular object, environment, or situation. Hence, good memories and positive experiences with a specific environment, object, or situation lead individuals to formulate a sense of happiness and make individuals more optimistic about the environment, object, or situation [ 46 ]. In other words, social media users with good memories and positive experiences with their favorite influencers are more likely to behave favorably for the influencers, expecting higher levels of good memories and positive experiences, core components of happiness in their daily life (i.e., psychological well-being in this study) [ 3 , 47 ]. For example, social media users are more likely to support their favorite influencers who can bring users happiness and help users to maintain positive emotional states in the virtual world. The virtually formulated happiness and positive emotional states among social media users can be transferred to their psychological well-being in the real world [ 47 ]. Hence, social media users are more likely to purchase products/services advertised and promoted by their favorite influencers to enhance their level of psychological well-being formed by the virtual interactions with the influencers [ 3 , 46 ]. Accordingly, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

Social media users’ psychological well-being is positively associated with loyalty toward their favorite influencer.

As a phenomenon, the spillover effect means that “a message influences beliefs related to attributes that are not contained in the message” [ 48 ] (p. 458). The spillover effect has been studied within various contexts, such as different brands within the same firm, different attributes of a company and/or brand, and between a firm and a nonprofit organization in partnership with the firm in cause-related marketing situations [ 49 , 50 ]. Particularly, in the socially responsible communication context, a spillover effect may occur between a brand and its spokesperson or ambassador. According to the associative network theory of memory, individuals’ memory of a particular object (or product) tends to be formed as a web or network of interconnected conceptual nodes in their brains that represents a variety of different pieces of information about the object (or product) with varied associative strength [ 51 , 52 ]. Therefore, individuals store the different pieces of information about the product in memory as conceptual nodes that are complicated and interconnected with other associative links, such as the products’ spokesperson and brands [ 53 ]. Since individuals’ product nodes have already been interconnected with the spokesperson and brand nodes within the same network, the product nodes will be influenced by external factors if the spokesperson and brand nodes are influenced by those external factors. Based on the fundamental notion of the associative network theory of memory, the current research predicts the spillover effect of social media influencers’ (spokesperson) perceived social responsibility on users’ behavioral intention to purchase products advertised by the influencers on social media. In other words, this study assumes that social media users are more likely to positively evaluate and purchase the products their favorite influencers advertise and promote on social media when perceiving the influencers as more socially responsible, and vice versa. Thus, the following research hypothesis is formulated:

Social media users’ perceived social responsibility of their favorite influencer moderates the relationships between their perceived friendship/psychological well-being and loyalty toward the influencer.

3.1. Data Collection

In this study, the unit of analysis was social media users in the United States subscribing to their favorite social media influencers’ pages via YouTube or following the influencers via Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. These social media platforms were specifically chosen because a majority of Americans have commonly used YouTube (81%), Facebook (69%), Instagram (40%), and Twitter (23%) according to the “Survey of U.S. adults conducted from 25 January to 8 February 2021.” The first page of the questionnaire addressed a brief description of a social media influencer to help the participants to understand the study context. To collect data from representative samples, the second page of the questionnaire provided the participants with two screening questions carefully reviewed by the authors: (1) Who is your favorite social media influencer? (i.e., the participants’ responses to this question were carefully checked by the authors by searching for the addressed names of social media influencers on Google; based on the social media influencers-related information on Google, the authors could double-check whether the influencers addressed by the participants were playing a role as social media influencers conceptually well-aligned with the definition of social media influencers in this study); and (2) Please write two main reasons why you like the social media influencer (the participants with simple answers, such as “I don’t know” or “None,” were removed during the authors’ data purification process). The second question was also designed to arouse the participants’ cognition of their addressed social media influencer before responding to the next questions. The authors posted the online survey link on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in the second week of May 2021 until the recommended number of participants was met for multivariate analyses to confirm reliabilities/validities (i.e., confirmatory factor analysis) and test the hypothesized associations among the variables in this study (i.e., structural equation modeling) ( N = 388). The demographic characteristics of the participants in this study used for data analyses are indicated in Table 1 .

Demographic analysis of respondents.

3.2. Measures

The authors adapted and revised multiple items to measure language similarity, interest similarity, interaction frequency, self-disclosure, perceived friendship, psychological well-being, loyalty, and perceived social responsibility of social media influencers. The authors invited two professionals to review the revised items and operationalizations of all constructs before conducting a pilot test. Next, the authors conducted a pilot test with 50 undergraduates at a public university in the United States, resulting in minor changes in the wording of some items and overall flow of the questionnaire, and then finalized the questionnaire. The participants were asked to respond to all questions with a 7-point Likert scale anchored by “1 = strongly disagree” and “7 = strongly agree” except for demographic characteristics. This study referred to the works of Su et al. [ 9 ] and Kim and Kim [ 3 ] to measure social media influencer attributes, consisting of language similarity (four items), interest similarity (three items), interaction frequency (four items), and self-disclosure (five items). Second, this study measured social media users’ perceived friendship with seven items from the work of Yim, Tse, and Chan [ 54 ]. Third, to measure psychological well-being, four items were adapted and revised from the work of Lee [ 55 ]. Fourth, the perceived social responsibility of influencers was measured with three items from Liu, Wong, Rongwei, and Tseng [ 56 ] (e.g., (1) “My favorite social media influencer supports nonprofit organizations working in socially problematic areas”; (2) “My favorite social media influencer contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of the society”; and (3) “My favorite social media influencer attempts to create a better life for others in need”). Lastly, this study operationalized loyalty with four items based on the work of Kim and Kim [ 57 ]. To avoid any issue with common method bias, the authors randomly ordered the survey items by employing a procedural remedy suggested by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff [ 58 ].

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. tests of reliabilities and validities.

To test the reliabilities and validities of all measures, the authors used the two-step approach proposed by Anderson and Gerbing [ 59 ]. before empirically testing the research hypotheses through structural equation modeling. As the first step, with SPSS 28.0, the authors conducted reliability analysis by estimating Cronbach alpha coefficients of all variables measured with multiple items. As indicated in Table 2 , all variables’ alpha coefficients were greater than the value of 0.70, which is generally acceptable in the social science fields [ 60 ].

Results of confirmatory factor analysis for items.

As the second step, with AMOS 28.0, the authors performed a confirmatory factor analysis to rigorously test the validities of all measures. To maintain the level of convergent validity, one of the items with less than 0.50 of the standardized regression weight, measuring the perceived friendship construct, was removed. The estimated fit indices of the measurement model were overall acceptable to proceed with tests of validities: χ 2 = 859.075, degree of freedom = 353 (the normed χ 2 = 2.434), p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.061, IFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.901, and CFI = 0.914 [ 61 ]. Table 2 indicates that all standardized regression weights and critical ratios of all items exceeded 0.50 and were statistically significant ( p < 0.001), respectively, confirming the convergent validities of all measures. In addition, the authors estimated the composite construct reliabilities of all constructs based on the empirical findings of the confirmatory factor analysis, signifying convergent validities because the values were greater than 0.70 [ 61 ] (see Table 3 ).

Construct intercorrelations ( Φ ), mean, SD (standard deviation), AVE (average variance extracted), and CCR (composite construct reliability).

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

The authors tested the discriminant validities of all constructs according to the recommendation of Fornell and Larcker [ 62 ]. First, the respective average variance extracted values were estimated based on the standardized regression weights of all items of each construct (see Table 3 ). Second, the authors conducted correlation analyses and compared the squared correlation coefficients of two constructs to the average extracted variance extracted values of each construct. In this case, the squared correlation coefficients of two constructs should not exceed the respective average variance extracted values of each construct to signify the discriminant validities of the two constructs. As demonstrated in Table 3 , the average variance extracted values of all constructs were greater than the squared correlation coefficients, confirming the discriminant validities of all constructs used in this study.

Lastly, the authors conducted Harman’s one-factor test as a statistical remedy to check whether the procedural remedy used during the questionnaire development process controlled common method bias [ 58 ]. The measurement model’s χ 2 and degree of freedom values were 859.075 and 353 (the normed χ 2 = 2.434), whereas a one-factor model’s χ 2 and degree of freedom values were 2366.695 and 377 (the normed χ 2 = 6.278), respectively. Because the normed χ 2 value of the measurement model was significantly better than that of the one-factor model (i.e., the measurement model has a higher level of factor-explanation power than that of the one-factor model), it was confirmed that the procedural remedy used in this study controlled common method bias well.

4.2. Tests of Research Hypotheses

With AMOS 28.0, the structural equation modeling approach was used to empirically test the research hypotheses based on maximum likelihood estimates of each path (see Figure 1 ). Compared to other multivariate techniques that investigate only a single relationship at a time, structural equation modeling enables scholars to examine the interrelationships among multiple independent variables, mediators, and dependent variables via one comprehensive technique, testing an entire theory with all possible variables [ 61 ]. Hence, the structural equation modeling approach was used by the authors because it would help test the key theoretical associations in the parasocial interaction, the self-congruity, and the psychological well-being theories through one comprehensive technique. The fit indices of the proposed model were acceptable to interpret the empirical findings in the social science fields: χ 2 = 887.539, degree of freedom = 357 (the normed χ 2 = 2.486), p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.063, IFI = 0.911, TLI = 0.898, and CFI = 0.910 [ 61 ].

Estimates of structural equation modeling.** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Note. Standardized regression weight (critical ratio), solid line: significant path, dotted line: insignificant path.