Slang language Detection and Identification In Text

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

INFLUENCE OF INTERNET SLANGS ON THE ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT OF SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN ESSAY WRITING IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE CHAPTER ONE

2019, INTERNET SLANG

The study on the impact of internet slang on the academic achievement of students aimed to determine the relationship between internet slang and academic achievement in secondary schools. The study made use of primary data obtained from research questionnaires. The study used Pearson correlation method for data analysis. The study concluded that there is a significant relationship between internet slang and academic performance.

RELATED PAPERS

produksibenihjagung distributorbenihjagung

Animal Agricultural Journal

Carmenza Gallego Giraldo

Viviana Parreño

Proceedings of the …

Stephen M Pickles

Jurnal Sains dan Terapan Kimia

Putri Ramadhani

Journal of Mathematics and Computer Science

haridas pawar

Journal of Law ( Jurnal Ilmu Hukum )

anshelvy triana ismi

Transfusion

tai man chan

Animal Biotechnology

Flavia Aline Bressani Donatoni

Al-Mudarris (Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Islam)

Putri Riani

Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica

María Ruiz-Ruigómez

Archives of Ophthalmology

Nhung Nguyen

Journal of Cancer Education

Eugenia Trotti

Mihaela Miki

Pablo Enrique Argañaras

Journal of Molecular Recognition

Gregory Crescenzo

Denis Puthier

Canadian journal of communication

Jody Berland

Ismahan Arslan-ari

Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine

Emilie Viollet

Ocean and Coastal Management

Tanya King , Nyree Raabe , Adam Cardilini

Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment

Karim Hamdi

Computers in Biology and Medicine

Tarik Mohamed

Journal of Molecular Structure

Ahsan Iqbal

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Good Slang or Bad Slang? Embedding Internet Slang in Persuasive Advertising

Internet slang is a new language with innovative and novel characteristics, and its use can be considered a form of creative advertising. Embedding internet slang into advertisements can thus enhance their creative quality and increase the attention paid to them. In this study, we examined the effect of the characteristics of internet slang on attention to advertisements, brand awareness, product evaluation, and attitudes toward advertising by conducting two empirical studies, one utilizing eye-tracking experiments and the other utilizing questionnaires. We found that using internet slang in advertising significantly increased audience attention compared with standard language but did not necessarily improve product evaluation and brand awareness for various types of goods. We discovered code-switching effects of psycholinguistics existed in standard language and its variant (internet slang). Our findings can guide advertisers in selecting the embedded language that can be effective in achieving their desired advertising effect. Our findings also indicate that the excessive use of internet slang may have a negative effect on brand and product evaluation.

Introduction

As society and the economy continue to develop, internet slang has shifted from being a mode of communication to being an everyday language. People’s communicative behavior, language, and psychology have all been affected by the subtle influence of internet slang ( Crystal, 2006 ). Corporations have also started employing internet slang in public communications. McDonald’s, for example, used the internet slang “么么哒” ( Mo Mo Da , a mimetic word for kissing) to promote its “Ice Cream Day,” because this word expresses ideas such as cuteness, proximity, and delightfulness. Some internet slang originates from the news, movies, TV programs, or online videos. For example, a popular online video featuring a character from an American TV show saying the phrase “Cash me ousside, howbow dah” (“Catch me outside, how about that?”) went viral because of the strong accent and rebellious attitude of the character. On the internet, a catch phrase or an incident can be publicized overnight, such as the expression “prehistoric powers” introduced by the young Chinese swimming athlete Yuanhui Fu or the emerging blend “Brexit” referring to the UK public vote for departure from the European Union. Internet slang has attracted the attention of corporations and its widespread use continues to grow.

In this study, we posed the following question: Is internet slang suitable for every product? It is possible that overusing internet slang in advertisements may yield unfavorable results, although such slang might attract more attention compared with standard language (SL). Therefore, this study explored people’s attention and evaluations (such as product evaluation and brand awareness) when encountering internet slang in various types of advertisements for products. The study also addressed whether internet slang is always has a positive effect on such evaluations.

This research makes several notable contributions. First, it adds to the literature related to advertising effect of languages, our work demonstrated the complex effects of internet slang on advertisements. Second, this work examined the advertising effect of internet slang from the attention perspective according to code-switching theory by using embedded language and eye tracking. These findings enrich both language and advertising communication theories.

Theoretical Framework

Internet slang.

The emergence of internet slang is a result of language variation. Language variation is a core concept in sociolinguistics ( Chambers, 2008 ) and a characteristic of language, which means there is more than one way of saying the same thing. Speakers may use distinct pronunciation (accent), word choice (lexicon), or morphology and syntax. In this research, internet slang is regarded as a variant of SL because it is normally related to word choice or morphology and syntax. Internet slang as a variant of SL (e.g., English, Chinese, and German) ( Collot and Belmore, 1996 ) is informal, irregular, and dynamic.

Internet slang often borrows foreign words, dialects, digital elements, and icons; it also frequently integrates the use of paraphrasing, homonyms, thumbnails, reduplication, and other word formation methods and unconventional syntax ( Kundi et al., 2014 ). Internet slang has gained a “novelty” effect through its anticonventional nature, which is why non-normativity is its defining characteristic. Compared with SL, internet slang has innovative and novel characteristics ( Collot and Belmore, 1996 ), and its use in advertising is highly creative. Attention to advertisements has increased following improvements in creative quality ( Pieters et al., 2002 ). For example, in tobacco advertisements, creative warnings attract more audience attention than regular warnings do ( Krugman et al., 1994 ). Exciting visuals can increase the perception of creativity, which attracts more attention to advertisements ( Hagtvedt, 2011 ).

Internet slang is novel, humorous, and interesting, and it possesses qualities that attract attention, particularly that of humor ( Eisend, 2011 ). By contrast, SL is more credible than non-SL. For example, the use of a standard accent in advertisements can largely offset any geographic, racial, or product differences ( Alcántara-Pilar et al., 2013 ); thus, a considerable number of studies have recommended the use of SL to improve the influence of communication. In our previous study, we observed that compared with advertisements that used SL, those that used internet slang attracted more attention ( Liu et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, electroencephalography studies have demonstrated that the cognitive processing of internet slang yields a significant N400 component and may involve creative thinking ( Zhao et al., 2017 ).

Internet Slang, Embedded Language, and Code-Switching Theory

Internet slang is often used in combination with SL. For example, communication in SL is occasionally interspersed with some internet slang terms to increase the attractiveness. Accordingly, internet slang is used in everyday life in the form of an embedded language. The advertising tactic of “inserting a foreign word or expression into a sentence (e.g., into an ad slogan), resulting in a mixed-language message” is called code-switching ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005a ; Lin et al., 2017 ). We applied code-switching theory in this research because the use of internet slang in advertising results in a similar situation as that of using code-switching. First, internet slang differs from SL because of its salient features, such as creative use of punctuation (e.g., emoticons), use of initialisms, omission of non-essential letters, and substitution of homophones ( Jones and Schieffelin, 2009 ). This distinctive style enables audiences to distinguish internet slang from SL when embedded in advertisements. For example, a study ( Zhao et al., 2017 ) reported that the processing of internet slang involves a novel N400 and late positive component, which reflects the recognition of the novel meanings of internet slang through event-related potentials (ERPs). Second, the language schema of internet slang is different from that of SL. Internet slang is heavily used by young people in computer-mediated communications and is usually perceived as creative, interesting, and pop culture-related ( Tagliamonte, 2016 ). However, for adults who mainly speak SL, internet slang is viewed as informal and extremely difficult to understand ( Jones and Schieffelin, 2009 ). Thus, examining the use of internet slang in advertising from the perspective of code-switching is reasonable.

The Markedness Model ( Myers-Scotton, 1993 ) has been used to explain the code-switching direction effect ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005b ). The linguistic term “markedness” is analogous to perceptual salience ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005b ). When an object or part of a message stands out from its immediate context, it becomes salient from the audience’s prior experience or expectation, or from foci of attention ( Fiske and Taylor, 1984 ). In regard to code-switching, the Markedness Model suggests that individuals will switch languages or insert other-language elements into their speech so as to communicate certain meanings or group memberships. Another language element becomes marked because of its contrast with the listener’s expectation. Luna and Peracchio (2005b) further explained that a marked element is recognized by the parties involved in the exchange as communicating a specific intended meaning. Scholars have argued that in a code-switching situation, the language schema of the words embedded in a message is activated because such words are more salient or marked compared with the matrix language. Language schemata include individuals’ perceptions of the social meanings of the language, the culture associated with the language, attitudes toward the language, the type of people who speak the language, the contexts in which the language can be used, the topics for which the language is appropriate, and beliefs about how others perceive the language ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005a , b ). For example, Luna and Peracchio (2005a) found that the language schema of Spanish, a minority language in the United States, can be activated when Spanish words are embedded in an ad slogan written in English (and vice versa). We propose that internet slang and SL may have similar code-switching effects when they are mix-used in advertisements. Therefore, this research involved conducting two studies to investigate whether code-switching effects occur between internet slang and SL, although internet slang is a variant of SL instead of a foreign language.

We believe that when internet slang is embedded in SL, the novelty of advertisements can provide a refreshing change for the audience and thus more likely garner their attention. Using eye movement tracking, we aimed to study the advertising effects produced by the use of internet slang as an embedded language, determine whether the use of internet slang as an embedded language can attract more attention, and explore whether this can generate positive advertising effects in terms of product evaluation and brand awareness. We expected that internet slang leads to an increase in consumers’ attention toward products, but excessive internet slang in advertisement does not necessarily generate a positive effect:

H1 : Embedded internet slang (EIL) (vs. SL) in advertisements results in an increased number of fixations and fixation time.

Luxury and Necessity Goods

Consumers may prefer different advertisements for various types of products, such as those that are functional or hedonic ( Drolet et al., 2007 ). Luxury brands are typically associated with social status, prestige ( Han et al., 2010 ), and superior product quality ( Zhan and He, 2012 ). Consequently, the purchase of luxury goods requires advertisements that resonate with the identity of consumers and thus attract their attention. Accordingly, SL can be reminiscent of a high value and trust level ( Lin and Wang, 2016 ), however, internet slang is timeliness, brisk and civilian that more consistent with style of necessity goods, could make necessity goods vivid and brisk; these features may increase consumers’ evaluations for brand and product. On the other hand, advertisement using internet slang for luxury brands may not be very appropriate, internet slang’s brisk and civilian style do not match with nobility and credibility of luxury goods, thus may not be better than SL which is meet the expectation of high value and credibility ( Lin and Wang, 2016 ). Moreover, overusing internet slang may result in frivolous feeling that would compromise the high quality which luxury goods state. Therefore, whether the use of EIL in advertisements for luxury and necessity goods generates different advertising effects is a subject that merits investigation. Moreover, there is a relative lack of empirical research on advertisements and on the effects of EIL and SL in advertisements for necessity and luxury goods.

In this study, eye tracking was the primary means of measurement employed. We used eye tracking because its superior signal-to-noise ratio (relative to brain imaging) renders it more suitable for the study of attention when individuals evaluate various types of products and make a choice. We conducted two studies to empirically examine the effects of using internet slang as an embedded language in advertising copies, the audience’s attention when reading the copies, and the effect of different embedded language advertising formats on the audience’s product evaluation, brand awareness, and attitudes toward advertising. We also intended to test whether overusing internet slang in advertisements compromises the persuasive effect of the advertisements. Therefore, we designed another type of advertisement that comprised several internet slang words with embedded standard language (ESL). The difference between EIL and ESL is that the main body of ESL advertisement was used internet slang, one sentence using SL was embedded (see Figure 1 ); in the contrast, the main body of EIL advertisement was used SL, one sentence using internet slang was embedded (see Figure 1 ). ESL was designed to overuse internet slang. We hypothesized the following: (1) regarding advertising copies, advertisements of EIL would be more effective in attracting consumers’ attention compared with advertisements of SL or ESL and (2) the use of internet slang would attract different levels of attention and have distinct advertising effects depending on the type of product (necessity goods and luxury goods) for which it is employed. These hypotheses are outlined as follows:

ROI zoning of SL, SIL, and ESL in study 1.

H2 : EIL in advertisements of luxury goods (vs. necessity goods) attracts more attention (an increased number of fixations and fixation time). H3a : EIL (vs. SL) in advertisements of necessity goods results in increased product evaluation, brand awareness, and attitude toward advertisements. H3b : EIL (vs. SL) in advertisements of luxury goods makes no significant difference in brand awareness, product evaluation, and attitude toward advertisements. H4 : ESL (vs. SL) in advertisements of luxury goods results in decreased product evaluation, brand awareness, and attitude toward advertisements.

Pilot Study

Before conducting formal experiments, we first performed a pilot study on advertising language screening and advertising copy evaluation. The pilot study served two purposes. The first purpose was to confirm that the three language versions (SL, ESL, and EIL) used in subsequent studies would not exhibit semantic differences; accordingly, we could exclude alternative explanations of semantics. The second purpose was to ensure that the products and advertisements selected would not exhibit any distinct appeal.

To compile a list of internet slang words, we applied our screening process to select the 20 most searched terms in China on Baidu. The primary criteria established for this process were as follows: the term must be well known; its usage must be widespread; and it must not have negative connotations, rendering it suitable for the design of an advertising copy. The designed advertising copy covered necessity goods, such as mineral water, toothpaste, cooking oil, towels, and shampoo, and luxury goods, such as watches, cars, perfume, jewelry, and leather items. Finally, the materials of the pilot study included 30 advertisements of five necessity goods (each product included three different language versions of SL, ESL, and EIL) and five luxury goods (each product included three different language versions of SL, ESL, and EIL). To exclude the influence of prior knowledge, all brands of products used in the advertisements were fabricated and not similar to any real brand, for excluding the influence of prior knowledge.

We first divided the advertising language into 10 groups for various products; each group contained three types of advertising language. Subsequently, the participants were asked to view advertisements in the three types of language (SL, ESL, and EIL) and to evaluate whether there were differences in semantics among the three language versions (SL, ESL, and EIL), which were measured on a five-point Likert scale. The findings revealed that for each product, the three versions of advertising language (SL, ESL, and EIL) yielded no semantic differences. Specifically, for necessity goods, such as toothpaste [mean = 2.43, standard deviation (SD) = 1.43], mineral water (mean = 2.33, SD = 1.30), cooking oil (mean = 2.60, SD = 1.43), towels (mean = 2.43, SD = 1.46), and shampoo (mean = 2.27, SD = 1.36), the means were all below the median (3). For luxury goods, such as watches (mean = 2.13, SD = 1.07), cars (mean = 2.40, SD = 1.33), perfume (mean = 2.63, SD = 1.52), jewelry (mean = 2.50, SD = 1.33), and leather items (mean = 2.33, SD = 1.16), the means were all below the median (3). The participants were 30 undergraduate students from the Shenzhen University. The results indicated that there were no significant semantic differences between the three versions of advertising language, signifying that our study would not be affected by semantic differences.

We recruited an additional group of 30 participants for the pilot study, all of whom were young people including university students and new employees. Concurrently, to avoid other differences caused by the copy used, manipulative variables were used to rate the responses regarding the rational and emotional appeal of the same 30 advertisements. Resnik and Stern proposed a standard definition of rational appeal based on 11 classification criteria: price, quality, characteristics, ingredients, purchase time and location, means of promotion, trial, function, packaging, guarantees, and novelty ( Resnik and Stern, 1977 ). Sciulli and Lisa (1998) proposed an emotional appeal scale comprising the following items: happiness, fear, joy, anger, interest, disgust, sadness, surprise, and numerous other emotional experiences. Therefore, these classification criteria were adopted in the pilot study. To measure advertising appeal, we selected four items (quality, ingredients, guarantees, and novelty) from the rational appeal scale and four items (happiness, interest, disgust, and sadness) from the emotional appeal scale. The participants were asked to evaluate these items for the 30 advertisements.

For all statistical analyses performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), the significance level was set to 0.05. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted using language type (SL, ESL, and EIL) by product type (necessity goods vs. luxury goods) as within-subjects factors. For the formal experiment, we selected the copy according to the ratings received in the pilot experiment. We conducted an ANOVA using language type (SL, ESL, and EIL) and product type (necessity and luxury) as the independent variables and rational and emotional appeal scores as the dependent variables. No significant main effects of language version were observed for rational appeal [ F (1, 29) = 1.616, p = 0.199] or emotional appeal [ F (1, 29) = 2.247, p = 0.106]. Furthermore, the main effects of product categories revealed no significant differences for rational appeal [ F (1, 29) = 1.277, p = 0.259] or emotional appeal [ F (1, 29) = 0.092, p = 0.762]. Moreover, the two-way interaction was not significant for rational appeal [ F (1, 29) = 0.066, p = 0.939] or emotional appeal [ F (1, 29) = 0.266, p = 0.767]. Therefore, the advertisements in three languages for both necessity goods and luxury goods did not differ in terms of rational and emotional appeal scores. The experimental materials were thus suitable for formal experimental study to explore the effect of advertising language versions on product evaluation, brand awareness, and attitude toward advertisements.

Participants

In total, 120 healthy volunteers (71 female individuals; mean age: 22.42 years) from the Shenzhen University, China, participated in the experiment, although six were subsequently excluded because of recording errors and severe artifacts in the data; the included participants took MBA classes and had an independent income and several years of work experience. A 2 (product type: necessity goods vs. luxury goods) × 3 (language type: SL, ESL, and EIL) between-subjects design was employed (factors were not significantly correlated). All participants were right-handed, had normal vision (with or without correction), reported no history of affective disorders or neurological diseases, and did not regularly use medication. All participants provided written informed consent before the experiment, and the study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University. All methods were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol.

In this experiment, we used the ASL-D6 eye-tracking system developed by the Applied Sciences Laboratory in the United States. This system has outstanding capturing and contract capabilities, can rapidly and accurately compensate for head movement, and can provide instant feedback during the tracking process. Thus, this system met the requirements of this experiment. After the initiation of the experiment, the screen displayed an advertising copy that was viewed by the participants. Upon completion of the experiment, the participants’ eye movement data and basic information were stored; the participants were then asked to complete a questionnaire regarding the content they had viewed.

Three types of languages were used for the advertisements, namely SL, SL embedded with internet slang, and internet slang embedded with SL. Thirty advertisements of five necessity goods (each product included the three different language versions of SL, ESL, and EIL) and five luxury goods (each product included the three different language versions of SL, ESL, and EIL) were used. As illustrated in Figure 1 , each advertisement contained five short sentences. Each advertisement was presented for 12 s to the participants. The study sequence was counterbalanced. The condition “SL” means that all sentences in the advertisement used SL. The condition “EIL” means that the main body of the advertisement was SL, but one sentence using internet slang was embedded; the non-embedded language was one sentence that did not contain internet slang, brand, or product name. The condition “ESL” means that the main body of the advertisement was internet slang, but one sentence using SL was embedded; the non-embedded language was one sentence that did not contain SL, brand, or product name. Figures on the advertisement copy with embedded language were then compared and adjusted to ensure that SL was embedded with internet slang (and vice versa), that the corresponding regions of interest (ROIs) of each figure were the same, and that brand names were placed in the same location.

After the eye movement experiment, the participants answered a questionnaire on the advertising copy. Experimental stimuli were divided into three ROIs ( Figure 1 ). An ROI is a specific region presented to participants for visual stimulation. To perform an intergroup comparison, the selected ROI for the same types of products was same placement of the embedded and non-embedded languages within the ROI. ROI1 contained the embedded language; ROI2 contained the brand and product name; and ROI3 contained the non-embedded language.

We selected three commonly used measures to evaluate attention to advertisements: fixation time ( Wedel and Pieters, 2000 ; Rayner et al., 2001 ; Decrop, 2007 ), number of fixations ( García et al., 2000 ; Wedel and Pieters, 2000 ; Wang and Day, 2007 ), and pupil diameter ( Krugman et al., 1994 ). Fixation time is the length of time a participant spends viewing the target zone, and it represents the amount of information they have processed in the zone. The longer the time is, the deeper the information processing in a specific area is. The number of fixations is a measure of the frequency of fixation in a zone by a participant; it represents the amount of information the participant has processed in the zone. The higher the number of fixations is, the greater the attention paid to the information in a specific zone is. The pupil diameter measures the size of the pupil; it represents the level of interest a participant shows in a specific zone. When the pupil diameter is enlarged, it implies the participant is viewing a zone that interests him or her.

Because arousal plays a vital role in cognitive tasks ( Schimmack and Derryberry, 2005 ; Dresler et al., 2009 ) by stimulating audience attention, the level of arousal was used as a control variable. According to Massar et al. (2011) , the question whose answer ultimately determines the level of arousal is “Were you calm when you viewed this ad?” The other control variables measured were follows: familiarity with internet slang, attitude toward the internet slang used, and product preferences.

For all statistical analyses performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), the significance level was set to 0.05. Post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni method. Significant interactions were analyzed through simple-effect models. ANOVAs were conducted using language type (SL, ESL, and EIL) by product type (necessity goods vs. luxury goods) as between-subjects factors.

Statistical results ( Figure 2 ) revealed that (1) in ROI1 (embedded language), language type [ F (2, 110) = 5.871, p = 0.004] and product type [ F (1, 110) = 12.185, p = 0.001] had significant main effects on fixation time; however, the interaction between language type and product type exhibited no significant effect [ F (2, 110) = 1.153, p = 0.319]. Regarding the product type, the fixation time on necessity goods was shorter than that on luxury goods. Concerning language type, the fixation time on ESL was the longest, followed by that on EIL and then that on SL. All means and SDs are presented in Table 1 .

Number of fixations and fixation time for standard language (SL), embedded standard language (ESL), and embedded internet slang (EIL) for necessity goods and luxury goods in study 1.

Mean and SD for standard language (SL), embedded standard language (ESL), and embedded internet slang (EIL) for necessity goods and luxury goods in study 1.

Language type [ F (2, 111) = 9.944, p < 0.001] and product type [ F (1, 111) = 14.148, p < 0.001] exerted significant main effects on number of fixations; however, the interaction between language type and product type displayed no significant effect [ F (2, 111) = 0.226, p = 0.798]. Regarding the product type, the number of fixations on necessity goods was lower than that on luxury goods. Concerning the language type, the number of fixations on ESL was the highest, followed by that on EIL and then that on SL. All means and SDs are presented in Table 1 .

(2) In ROI2 (brand and product name), language type [ F (2, 110) = 7.998, p = 0.001] and product type [ F (1, 110) = 12.335, p = 0.001] had significant main effects on fixation time, and the interaction between language type and product type exerted a significant effect on fixation time [ F (2, 110) = 4.298, p = 0.016]. The fixation time on necessity goods was shorter than that on luxury goods. Regarding the language type, the fixation time on EIL was the longest, followed by that on ESL and then that on SL. These results suggest that EIL attracts more attention to brand and product names. Furthermore, the results of simple-effect tests showed that for necessity goods, the use of EIL and ESL had no effect (but they performed better than SL alone), whereas for luxury goods, the use of EIL and ESL had a significant effect. Therefore, EIL outperformed SL, whereas ESL and SL did not differ in performance. All means and SDs are shown in Table 1 .

Language type [ F (2, 111) = 11.615, p < 0.001] and product type [ F (1, 111) = 16.197, p < 0.001] had significant main effects on the number of fixations; however, the interaction between language type and product type exhibited no significant effect [ F (2, 111) = 2.490, p = 0.088]. Concerning the product type, the number of fixations on necessity goods was lower than that on luxury goods. In terms of the language type, the number of fixations on EIL was the highest, followed by the number of fixations on ESL and SL. All means and SDs are listed in Table 1 .

Our results reveal that the type of language used in the advertisements significantly influenced the participants’ attention to both necessity and luxury goods. Internet slang in the advertisements was proved to be eye-catching, and ESL attracted much more attention than SL and EIL did in the ROI of embedded language. However, in the ROI of brand and product name, EIL attracted more attention than SL and ESL did.

A total of 900 healthy volunteers (420 female individuals, mean age: 23.68 years; 580 student samples and 271 non-student samples) from the Shenzhen University, China, participated in the experiment, of whom 49 were excluded because of incorrectly answered questionnaires; therefore, the final sample comprised 580 students and 271 nonstudents. A 2 (product type: necessity goods vs. luxury goods) × 3 (language type: SL, ESL, and EIL) between-subjects design was employed (factors were not significantly correlated). All participants were right-handed, had normal vision (with or without correction), reported no history of affective disorders or neurological diseases, and did not regularly use medication. All participants provided written informed consent before the experiment, and the study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Shenzhen University. All methods were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol.

The products and advertising copy employed in this experiment were the same as those used in study 1. We created an online survey on WJX, 1 a widely used online survey platform in China, to measure all the variables for experiments. Online surveys are usually subject to concerns such as an insufficient amount of time spent on questions and multiple questionnaires being completed by the same individual. The WJX survey platform avoids these problems by setting a minimum duration required to complete a questionnaire and by preventing users with the same IP address or device from participating multiple times.

We combined the scales developed by Gardner et al. (1985) and Huang et al. (2006) to determine five questions used to measure attitudes toward advertisements. Brand awareness is based on the brand equity model ( Keller, 1993 ) and includes both brand recognition and brand recall. Brand recognition refers to aided brand awareness, whereas brand recall refers to unaided brand awareness. To measure product evaluation, Dodds et al. (1991) proposed the use of perceived product quality, perceived product value, and purchase intent. We tested all three measures ( p < 0.001) using a univariate analysis, and their component reliability was higher than the recommended standard of 0.6. Finally, the following measures of product evaluation were used: perceived product quality (quality, reliability, and durability), perceived product value (cost effectiveness, acceptability, and value for money), and purchase intent (purchase intent and considering purchase). The control variables in our study were as follows: (1) familiarity with internet slang, (2) attitude toward the internet slang, (3) product preferences, and (4) arousal. We selected all these control variables as covariates in the ANOVA.

For all statistical analyses performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), the significance level was set to 0.05. Post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni method. Significant interactions were analyzed through simple-effect models. ANOVAs were conducted using language type (SL, ESL, and EIL) by the product type (necessity goods vs. luxury goods) as between-subjects factors.

Statistical results ( Figure 3 ) indicated that the language type had a significant main effect [ F (2, 844) = 8.767, p < 0.001] on brand awareness, although the main effect of product type was not significant [ F (1, 844) = 0.623, p = 0.430]. The interaction between the language type and product type exhibited no significant effect [ F (2, 844) = 1.888, p = 0.152]. Overall, the brand awareness of EIL was the highest and was significantly higher than that of ESL. All means and SDs are presented in Table 2 .

Brand awareness, product evaluation, and attitude toward advertisements for necessity goods and luxury goods in study 2.

Mean and SD for standard language (SL), embedded standard language (ESL), and embedded internet slang (EIL) for necessity goods and luxury goods in study 2.

Language type [ F (2, 845) = 47.125, p < 0.001] and product type [ F (1, 845) = 6.163, p = 0.013] had significant main effects on product evaluation; however, the interaction between language type and product type exhibited no significant effect [ F (2, 845)= 1.888, p = 0.529]. Overall, the product evaluation of EIL was the highest and was significantly higher than that of ESL. All means and SDs are shown in Table 2 .

Language type had a significant main effect [ F (2, 845) = 34.368, p < 0.001] on attitudes toward advertisements; however, product type exhibited no significant main effect [ F (1, 845) = 0.747, p = 0.388]. The interaction between language type and product type exhibited no significant effect [ F (2, 845) = 1.183, p = 0.307]. Overall, the brand awareness of EIL was the highest and was significantly higher than that of ESL. All means and SDs are presented in Table 2 .

The observed mediational relationship was confirmed by a bootstrapping analysis (bias-corrected; 10,000 samples), in which the 95% confidence interval in the indirect effect did not include zero (0.05, 0.90). Bootstrap results revealed that the indirect effect was significant ( p < 0.001) and that attitudes toward advertisements mediated the effect of language type on brand awareness ( Figure 4 ). These results suggest that the advertisements that used EIL performed better than those that used ESL and SL regarding brand awareness, product evaluation, and attitudes toward advertisements.

Mediation of language type to brand awareness through attitudes toward advertisements. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Our results reveal that EIL advertisements had higher ratings on brand awareness, product evaluation, and attitudes toward advertisements than SL and ESL advertisements did. Compared with EIL advertisements, ESL advertisements had the lowest of all ratings, even lower than those of SL advertisements. This indicates that the excessive use of internet slang may have a negative effect on brand and product evaluation. For luxury goods, internet slang did not generate a positive effect on brand awareness compared with SL.

Changes in languages used in advertising can affect the market value of corporations. Advertising languages that are outstanding or have gained consumers’ recognition exert significant and positive effects on the development and market value of corporations ( Mathur and Mathur, 1995 ). Advertisements that focus on consumer recognition and use modern internet slang may exert a positive effect on both a firm and its product(s). We argue that the effect of internet slang on advertisement is complex; it depends on the types of products and the embedding style. Our findings indicate that advertisements with internet slang are not always attractive, and the excessive use of internet slang may have a negative effect on brand and product evaluation.

Theoretical Contribution and Implications

Code-switching theory.

According to Ahn et al. (2017) , code-switching is a mixed-language approach and is often used to target consumers with knowledge of two languages. Code-switching refers to the insertion of linguistic elements of one language into another language ( Grosjean, 1982 ). An example of code-switching is inserting an English word into a Korean sentence ( Ahn et al., 2017 ). However, most studies examining the effect of code-switching on processing ads have been undertaken in the United States by focusing on the mixed use of Spanish and English languages ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005a , b ; Bishop and Peterson, 2010 ). Ahn et al. (2017) suggested that additional research is warranted in other regions where code-switching occurs between languages other than English and Spanish.

Our study was undertaken in the China market. Chinese language is a character-based writing system as well as a meaning-based writing system, whereas English is a sound-based writing system and an alphabetic writing system ( Cook and Bassetti, 2005 ). Our results indicate that code-switching effects occur not only in a sound-based and alphabetic writing system but also in a character-based and meaning-based writing system. Therefore, these findings extend the external validation of code-switching theory.

Furthermore, in this study, we investigated SL (Mandarin) and its variant (internet slang), and the results demonstrate that code-switching theory is also effective to SL and its variant. Specifically, the validation of code-switching is further extended because previous research has mainly focused on the mixed use of two different languages ( Bishop and Peterson, 2010 ; Ahn et al., 2017 ). Finally, by empirically investigating the role of code-switching in advertising effectiveness, the findings of this study provide theoretical and practical implications regarding the code-switching approach for researchers and advertisers.

Novelty and Attention of Internet Slang

SL and internet slang have distinct characteristics. When advertisements use SL, a feeling of standardization and strictness is induced ( Vignovic and Thompson, 2010 ); by contrast, when advertisements use internet slang, consumers identify the signals sent by the language, such as novelty or trendiness ( Collot and Belmore, 1996 ; Crystal, 2006 ), with their own personalities, making them feel closer to the brand and generating a more favorable emotional experience. Therefore, compared with advertisements in SL, advertisements embedded with internet slang highlight the fun and fresh characteristics of such slang; consequently, people form more positive attitudes toward such advertisements.

Liu et al. (2013) reported that advertisements in Cantonese and Mandarin have different advertising effects, and Henderson et al. (2004) revealed that trademarks in standard and handwritten typefaces can leave different impressions. Thus, different effects are exerted depending on how advertising language is presented. Exciting advertisements evoke positive emotions from consumers, and the consumers associate these with the product ( Eunsun et al., 2005 ). Internet slang is generally considered to be humorous, fun, and exciting ( Collot and Belmore, 1996 ). The employment of internet slang in advertising copies exerts a “novelty” effect on the corresponding advertisement; therefore, attention increases as advertisements become more creative ( Pieters et al., 2002 ). A novel advertising language that is creative can attract more attention, which is in line with the findings of our previous study. The novelty, humor, and fun characteristics of internet slang are evident when EIL appears in advertisements ( Pieters et al., 2002 ); thus, advertisements in SL that are embedded with internet slang can attract more attention compared with other advertisements.

Peng et al. (2017) reported that consumers believed the exposure time to internet slang was longer than that to SL, although internet slang and SL as stimuli lasted for the same period in their experiment. A possible explanation for these results is that consumers have to spend more resources on processing internet slang. The results of our eye-tracking experiments support this supposition, and we discovered that EIL (vs. SL) in advertisements results in an increased number of fixations and a longer fixation time.

The eye-catching ability of internet slang is attributable to its higher amount of information and greater association for consumers, which thus signifies that internet slang requires more time to process. A recent ERP study on internet slang indicated that the information processing fluency of internet slang is much lower than that of SL ( Zhao et al., 2017 ). This finding is also supported by our eye-tracking experiments; more attention is paid to internet slang. The reason for this outcome requires elucidation. This outcome can be explained by the novelty of internet slang, which originates from pop culture. Previous research suggested that internet slang is considered novel and innovative ( Hagtvedt and Patrick, 2008 ). This is because internet slang is generally created in a creative and innovative manner. Thus, since its creation, internet slang has been accepted and spread rapidly and extensively ( Liu et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, Zhao et al. (2017) argued that internet slang is perceived through creative information processing; this perception process reflects the recognition of the novel meanings of internet words as well as the integration of novel semantic processing.

The innovativeness of language has a crucial advertising effect ( Eisend, 2011 ). Internet slang is inherently creative, and the creativity of internet slang has a positive influence on consumers’ perception of advertisements ( Karson and Fisher, 2005 ). Specifically, Eisend (2011) suggested that the innovativeness of internet slang can elicit consumers’ perception of an ad’s innovativeness. This thus explains our finding that internet slang used in advertisements had positive effects on product evaluation, brand awareness, and attitude toward advertisements.

Complex Effect of Internet Slang on Various Types of Products

Necessity goods are indispensable for the daily lives of consumers and are extremely practical ( Chen and Wang, 2012 ); consumers purchase such goods to fulfill their daily needs. Necessity goods are relatively cheap, are only slightly affected by information, and do not require extra information processing on the part of the consumer. Consumers can easily develop brand loyalty toward necessity goods in a way that transforms into habitual purchasing behavior ( Monle and Tuen-Ho, 2003 ). In the ROIs of brand names of necessity goods in this study, EIL and ESL did not elicit distinct levels of attention (but both of them outperformed SL), indicating that internet slang helps increase consumers’ attention to brands of necessity goods. For luxury goods, the effects of EIL and ESL differed significantly; EIL outperformed SL, but ESL and SL did not differ in performance. These findings indicate that the excessive use of internet slang (advertising copy in ESL) does not increase audience attention to brands of luxury goods.

Luxury goods are subject to a high perceived risk; thus, information must be processed more carefully. In contrast to the level of information processing necessary for necessity goods, information on luxury goods requires in-depth processing. When a product becomes a luxury good, the use of SL in advertisements prompts consumers to associate the advertised products with high quality because SL is associated with high value and credibility ( Lin and Wang, 2016 ) and serves as the principal language with rigor and reliability ( Yip and Matthews, 2006 ). Therefore, appropriately embedding internet slang can increase attention to a brand. However, the use of inappropriate internet slang would not achieve positive advertising effects.

Our study indicates that because of its high levels of creativity and timeliness, internet slang may temporarily increase audience attention to advertising language, but it cannot produce the same effect on higher status products (such as luxury goods). Furthermore, an excessive use of internet slang may cause the audience to feel frivolous, which damages the trust consumers have in a brand or product. For example, a highly trusted advertising language generates better results ( Kronrod et al., 2012 ). The second experiment also showed that in terms of brand awareness and product evaluation, advertising copies in ESL had the lowest scores; the conventional use of SL for advertising copies can thus yield superior performance compared with the extensive use of internet slang for advertising copies.

Practical Implications

The rapid spread of internet platforms means that internet slang can become a social buzzword under certain circumstances ( Sun et al., 2011 ). Once internet slang gains public recognition and spreads at an extremely rapid rate, numerous corporations will begin to integrate it into their advertising copies. In practice, the use of internet slang requires careful consideration by marketing practitioners. Copies in internet slang can increase an audience’s attention, but they may also weaken their attention to other elements of the same advertisement. Although internet slang can significantly enhance product evaluation, it may undermine advertising reliability. Marketing practitioners should use internet slang based on their communication objectives to produce effective results. In addition, rather than simply following the current internet slang trends, marketing personnel should employ differentiated advertising strategies depending on the type of product to help align the implemented advertising copy with that product.

Limitation and Future Direction

Our work has a few limitations, which opens up avenues for future research. First, creativity is one of the major features of internet slang, but it was not measured in our research. Novelty and creativity may be alternative explanations for the positive effect of EIL on attention and higher evaluations for advertisements and brand. Future studies should focus on the connection between attention and the creativity and novelty features of internet slang. Second, notably, novelty and creativity cannot explain the negative effect of ESL. The excessive use of internet slang possibly leads to frivolousness, vulgarity, and incredulity about an advertisement, particularly for luxury goods that exhibit strengthened superiority and dignity. Future studies could examine the various effects and corresponding mechanisms of EIL and ESL on advertisements.

Third, the process of code-switching costs more attention resources. Luna and Peracchio (2005a) argued that, when individuals direct their attention to the codeswitched word, they will activate the language schema to which that word belongs and become aware of the social meaning carried by that language. The language schema associated with the code-switched term is subject to a high degree of elaboration because of the markedness of the term ( Johnston et al., 1990 ). However, more attention and high degree of elaboration do not necessarily mean EIL and ESL are confusing; in fact, code-switching is generally socially motivated and is rarely a sign of a lack of fluency in either language ( Grosjean, 1982 ; Luna and Peracchio, 2005b ). There might be some differences of how easy to understand the ads among SL, EIL, and ESL, future studies should add the items that measure how easy (or hard) to understand different advertisements.

Timeliness of internet slang is another interesting feature that we did not examine in the current research. Internet slang displays strong timeliness; the novelty and creativity of internet slang may decrease with time, and the corresponding positive effect may also decline. Finally, the current research examined the code-switching effect between SL and its variant for Chinese advertisements; however, whether it exists in other languages (such as English or Spanish) should be further examined by future studies.

We examined the effect of internet slang on attention to advertisements, product evaluation, and advertising attitude by conducting two empirical studies, one of which involved eye-tracking experiments and the other applied questionnaires. The results show that advertisements in EIL generated positive brand awareness and product evaluation and also increased advertising attention. Our findings reveal the complex effects of internet slang on advertisements and extend the external validation of code-switching theory. These findings can guide advertisers in selecting an embedded language that can be effective in achieving their desired advertising effect. To attract an audience’s attention, the use of EIL can help consumers experience the creativity of internet slang, thereby forming positive brand awareness and product evaluation. However, for different types of products that address dissimilar needs, practitioners should avoid the extensive use of internet slang once they have decided which advertising strategy and advertising copy they will use, particularly in relation to luxury goods. They can decide to use SL or embed a small portion of internet slang into their advertisements.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Local Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University.

Author Contributions

SL and D-YG conceived and designed the experiments. SL, YD, and YZ performed the experiments. D-YG and YZ analyzed the data. D-YG and SL wrote the manuscript. SL and D-YG contributed materials and analysis tools. SL provided lab equipment for running the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support granted by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Project Number: 71572116), National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (2018A030310568), and the Scientific Research Foundation for New Teacher of Shenzhen University (2017012). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

1 https://www.wjx.com/

- Ahn J., La Ferle C., Lee D. (2017). Language and advertising effectiveness: code-switching in the Korean marketplace . Int. J. Advert. 36 , 477–495. 10.1080/02650487.2015.1128869 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alcántara-Pilar J. M., del Barrio-García S., Porcu L. (2013). A cross-cultural analysis of the effect of language on perceived risk online . Comput. Hum. Behav. 29 , 596–603. 10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.021 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bishop M. M., Peterson M. (2010). The impact of medium context on bilingual consumers’ responses to code-switched advertising . J. Advert. 39 , 55–67. 10.2753/JOA0091-3367390304 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chambers J. K. (2008). Sociolinguistic theory. 3rd Edn. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen J., Wang F. (2012). Effect of perceived values on consumer purchase intention among commodity category . J. Syst. Manag. 21 , 802–810. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-2542.2012.06.012 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Collot M., Belmore N. (1996). Electronic language: A new variety of english. (Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook V., Bassetti B. (2005). Second language writing systems. (Bristol, United Kingdom: Channel View Publications Ltd; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Crystal D. (2006). Language and the internet. (New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Decrop A. (2007). The influence of message format on the effectiveness of print advertisements for tourism destinations . Int. J. Advert. 26 , 505–525. 10.1080/02650487.2007.11073030 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dodds W. B., Monroe K. B., Grewal D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations . J. Mark. Res. 28 , 307–319. 10.2307/3172866 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dresler T., Meriau K., Heekeren H. R., van der Meer E. (2009). Emotional stroop task: effect of word arousal and subject anxiety on emotional interference . Psychol. Res. 73 , 364–371. 10.1007/s00426-008-0154-6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drolet A., Williams P., Lau-Gesk L. (2007). Age-related differences in responses to affective vs. rational ads for hedonic vs. utilitarian products . Mark. Lett. 18 , 211–221. 10.1007/s11002-007-9016-z [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisend M. (2011). How humor in advertising works: a meta-analytic test of alternative models . Mark. Lett. 22 , 115–132. 10.1007/s11002-010-9116-z [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eunsun L., Tinkham S., Edwards S. M. (2005). The multidimensional structure of attitude toward the ad: Utilitarian, hedonic, and interestingness dimensions. (American Academy of Advertising; ), 58–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fiske S., Taylor S. (1984). Social cognition. (New York: McGraw-Hill; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- García C., Ponsoda V., Estebaranz H. (2000). Scanning ads: effects of involvement and of position of the illustration in printed advertisements . Adv. Consum. Res. 27 , 104–109. Retrieved from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=6686970&lang=es&site=ehost-live%5Cnhttp://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?T=P&P=AN&K=6686970&S=R&D=bth&EbscoContent=dGJyMNLe80SeprI4yOvqOLCmr0uep7FSs624TLaWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGus [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner M. P., Mitchell A. A., Russo J. E. (1985). Low involvement strategies for processing advertisements . J. Advert. 14 , 4–56. 10.1080/00913367.1985.10672941 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grosjean F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagtvedt H. (2011). The impact of incomplete typeface logos on perceptions of the firm . J. Mark. 75 , 86–93. 10.1509/jmkg.75.4.86 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagtvedt H., Patrick V. M. (2008). Art infusion: the influence of visual art on the perception and evaluation of consumer products . J. Mark. Res. 45 , 379–389. 10.1509/jmkr.45.3.379 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Han Y. J., Nunes J. C., Drèze X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: the role of brand prominence . J. Mark. 74 , 15–30. 10.1509/jmkg.74.4.15 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson P. W., Cote G. J. A. (2004). Impression management using typeface design . J. Mark. 68 , 60–72. 10.1509/jmkg.68.4.60.42736 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang J., Wang G., Zhao P. (2006). Advertising persuasion for brand extension: revising the dual mediation model . Acta Psychol. Sin. 38 , 924–933. 10.1016/S0379-4172(06)60092-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnston W. A., Hawley K. J., Plewe S. H., Elliott J. M. G., DeWitt M. J. (1990). Attention capture by novel stimuli . J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 119 , 397–411. 10.1037/0096-3445.119.4.397 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones G. M., Schieffelin B. B. (2009). Talking text and talking back: “my bff jill” from boob tube to youtube . J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 14 , 1050–1079. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01481.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Karson E. J., Fisher R. J. (2005). Reexamining and extending the dual mediation hypothesis in an on-line advertising context . Psychol. Mark. 22 , 333–351. 10.1002/mar.20062 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keller K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, managing customer-based brand equity . J. Mark. 57 , 1–22. 10.2307/1252054 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kronrod A. N. N., Grinstein A., Wathieu L. U. C. (2012). Enjoy! Hedonic consumption and compliance with assertive messages . J. Consum. Res. 39 , 51–61. 10.1086/661933 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krugman D. M., Fox R. J., Fletcher J. E., Fischer P. M., Rojas T. H. (1994). Do adolescents attend to warnings in cigarette advertising? An eye-tracking approach . J. Advert. Res. 34 , 39–52. 10.1016/0165-4101(94)90027-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kundi F. M., Ahmad S., Khan A., Asghar M. Z. (2014). Detection and scoring of internet slangs for sentiment analysis using sentiwordnet . Life Sci. J. 11 , 66–72. 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.1609621 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin Y.-C., Wang K.-Y. (2016). Local or global image? The role of consumers’ local–global identity in code-switched ad effectiveness among monolinguals . J. Advert. 45 , 482–497. 10.1080/00913367.2016.1252286 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin Y.-C., Wang K.-Y., Hsieh J.-Y. (2017). Creating an effective code-switched ad for monolinguals: the influence of brand origin and foreign language familiarity . Int. J. Advert. 36 , 613–631. 10.1080/02650487.2016.1195054 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Bi X., He G. (2017). The impact of internet language copy on consumers’ attention and perceptions of the advertisement . Acta Psychol. Sin. 49 , 1590–1603. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.01590 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Wen X., Wei L., Zhao W. (2013). Advertising persuasion in China: using mandarin or cantonese? J. Bus. Res. 66 , 2383–2389. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.05.024 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luna D., Peracchio L. A. (2005a). Advertising to bilingual consumers: the impact of code-switching on persuasion . J. Consum. Res. 31 , 760–765. 10.1086/426609 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luna D., Peracchio L. A. (2005b). Sociolinguistic effects on code-wwitching ads targeting bilingual consumers . J. Advert. 34 , 43–56. 10.1080/00913367.2005.10639196 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Massar S. A., Mol N. M., Kenemans J. L., Baas J. M. (2011). Attentional bias in high- and low-anxious individuals: evidence for threat-induced effects on engagement and disengagement . Cognit. Emot. 25 , 805–817. 10.1080/02699931.2010.515065, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathur L. K., Mathur I. (1995). The effect of advertising slogan changes on the market values of firms . J. Advert. Res. 35 , 59–65. 10.2307/2491382 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Monle L., Tuen-Ho H. (2003). The refinement of measuring consumer involvement-an empirical study . Compet. Rev. 13 , 56–65. 10.1108/eb046452 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Myers-Scotton C. (1993). Social motivations for codeswitching: Evidence from Africa. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Peng M., Jin W., Cai M., Zhou Z. (2017). Perceptual difference between internet words and real-world words: temporal perception, distance perception, and perceptual scope . Acta Psychol. Sin. 49 , 866–874. 10.3724/sp.j.1041.2017.00866 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pieters R., Warlop L., Wedel M. (2002). Breaking through the clutter: benefits of advertisement originality and familiarity for brand attention and memory . Manag. Sci. 48 , 765–781. 10.1287/mnsc.48.6.765.192 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rayner K., Rotello C. M., Stewart A. J., Keir J., Duffy S. A. (2001). Integrating text and pictorial information: eye movements when looking at print advertisements . J. Exp. Psychol. 7 , 219–226. 10.1037/1076-898X.7.3.219, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Resnik A., Stern B. L. (1977). An analysis of information content in television advertising . J. Mark. 41 , 50–53. 10.2307/1250490 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schimmack U., Derryberry D. (2005). Attentional interference effects of emotional pictures: threat, negativity, or arousal? Emotion 5 , 55–66. 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.55, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sciulli, Lisa M. (1998). How organizational structure influences success in various types of innovations . J. Retail Bank. Serv. 20 , 13–18. 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.55, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sun J., Fan Q., Chao N. (2011). The concept and communication process of network buzzwords . J. Nanjing Univ. Post. Telecommun. 13 , 15–19. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5420.2011.03.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tagliamonte S. A. (2016). So sick or so cool? the language of youth on the internet . Lang. Society 45 , 1–32. 10.1017/S0047404515000780 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vignovic J. A., Thompson L. F. (2010). Computer-mediated cross-cultural collaboration: attributing communication errors to the person versus the situation . J. Appl. Psychol. 95 , 265–276. 10.1037/a0018628, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang J.-C., Day R.-F. (2007). The effects of attention inertia on advertisements on the www . Comput. Hum. Behav. 23 , 1390–1407. 10.1016/j.chb.2004.12.014 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wedel M., Pieters R. (2000). Eye fixations on advertisements and memory for brands: a model and findings . Mark. Sci. 19 , 297–312. 10.1287/mksc.19.4.297.11794 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yip V., Matthews S. (2006). Assessing language dominance in bilingual acquisition: a case for mean length utterance differentials . Lang. Assess. Q. 3 , 97–116. 10.1207/s15434311laq0302_2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhan L., He Y. (2012). Understanding luxury consumption in China: consumer perceptions of best-known brands . J. Bus. Res. 65 , 1452–1460. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.011 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhao Q., Ke W., Tong B., Zhou Z., Zhou Z. (2017). Creative processing of internet language: novel n400 and lpc . Acta Psychol. Sin. 49 , 143–154. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00143 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Measuring internet slang style in the marketing context: scale development and validation.

- 1 Department of Marketing, College of Management, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 2 Asia Europe Business School, Faculty of Economics and Management, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

As an emerging language variant, practitioners have extensively used Internet slang in advertising and other communication activities. However, its unique characteristics that differ from standard language have yet to be explored. Drawing upon interdisciplinary theories on schema and communication styles, this research makes the first attempt to conceptualize and measure these characteristics by introducing a new multi-dimensional construct, “Internet slang style,” in the marketing context. It develops and validates a new scale to measure Internet slang style along the dimensions of amiability, overtness, candor, and harshness through a series of in-depth interviews, two surveys, and one experiment with consumers. In addition, this research investigates the impact of Internet slang styles on brand personality and brand attitude. The results indicate that different Internet slang style dimensions positively correspond to different brand personality dimensions but exert no influence on brand attitude. Practically, the scale provides an easy-to-use instrument to evaluate Internet slang styles from a consumer perspective to help companies appropriately employ Internet slang in marketing communication activities.

Introduction

The extensive usage of the Internet and social media leads to the integration of virtual and real-life ( Kilicer et al., 2017 ). As a result, Internet slang that emerges and develops online has become part of our everyday language, and even unconsciously influences people’s psychological states and behaviors in areas such as communication and consumption ( Crystal, 2006 ; Liu et al., 2019 ). For example, expressions such as “rona” or “vid” have been popular among young people to replace the formal designation “COVID-19” and to inject a sense of humor as a relief when facing the problematic current pandemic situation. Meanwhile, marketing practitioners have begun to notice the advantages of introducing Internet slang in advertisements. An example of this is Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” summer campaign in China, in which many popular online nicknames were selected and printed on the coke bottles [e.g., “北鼻 (Bei Bi),” a transliteration of “baby”] to generate senses of proximity and cuteness among young consumers.

Internet slang can create distinct associations in consumers’ perceptions as a unique language variant of the standard language ( Crystal, 2006 ). These associations can be understood within the framework of language schemata, which refers to an individual’s prototypical knowledge about the language, including its underlying social and cultural meanings, typical users, contexts, and appropriate topics, as well as individuals’ beliefs about the language ( Luna and Peracchio, 2005 ). Such understanding would help both academics and practitioners clarify the merits and demerits of Internet slang and establish criteria for selecting appropriate slang in marketing activities. For example, recent empirical research shows that Internet slang with innovative and novel characteristics can attract audience attention ( Liu et al., 2019 ). However, no study yet has systematically investigated consumers’ perceptions about Internet slang as a whole.

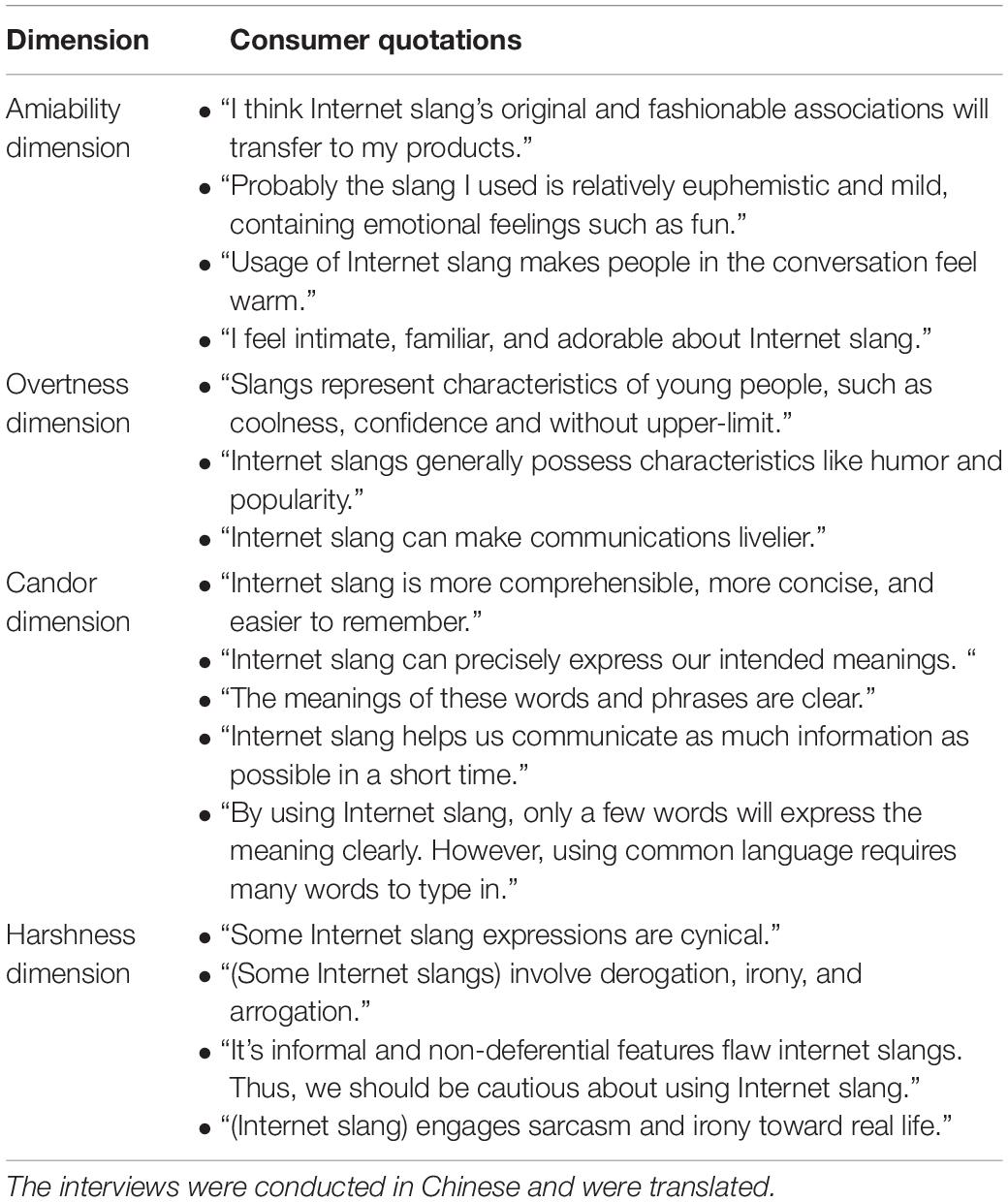

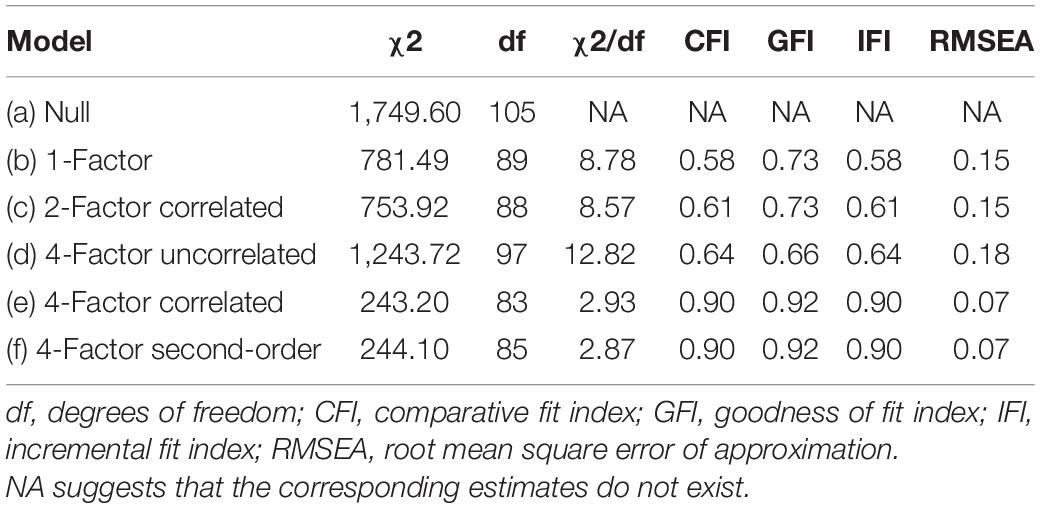

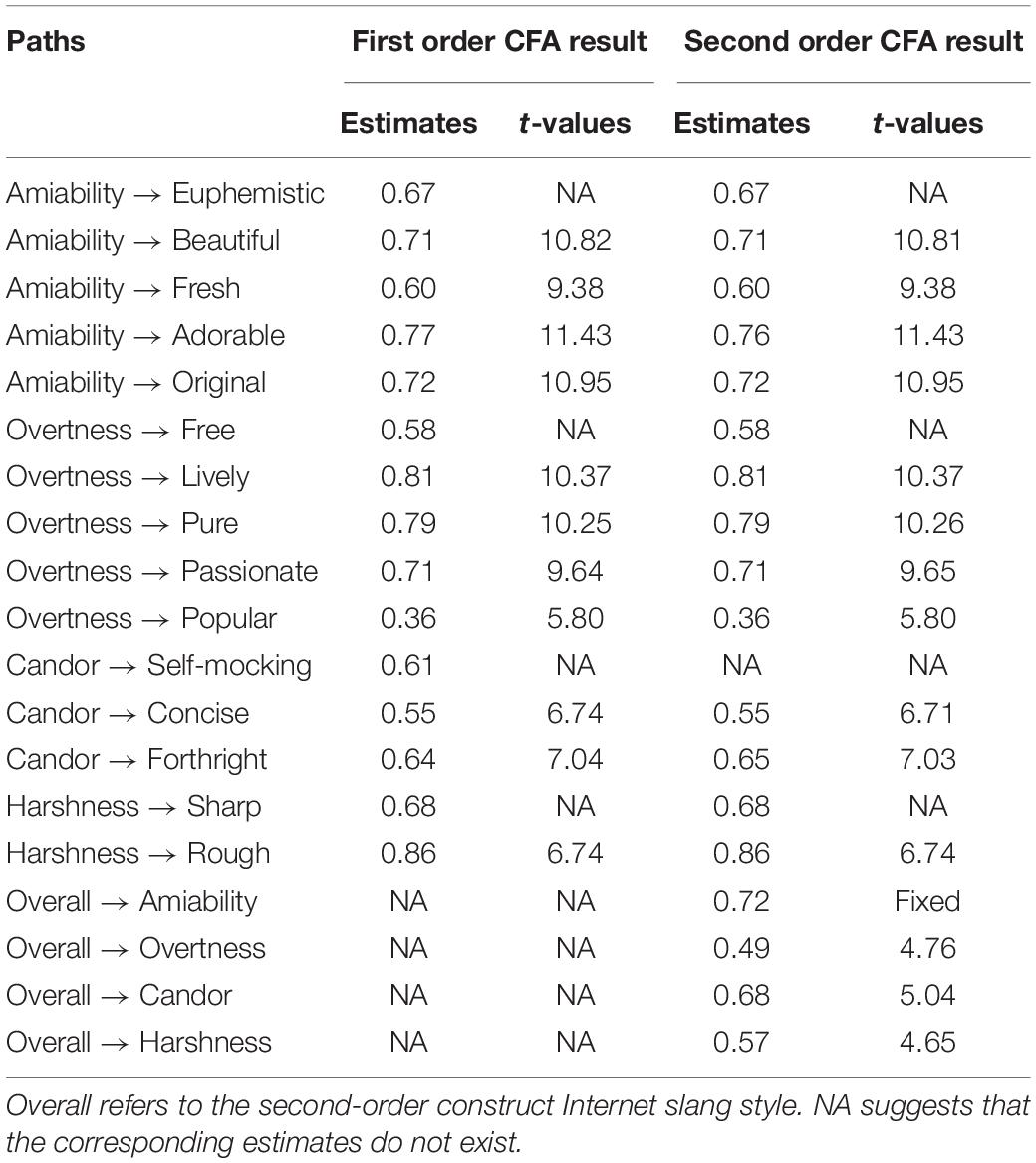

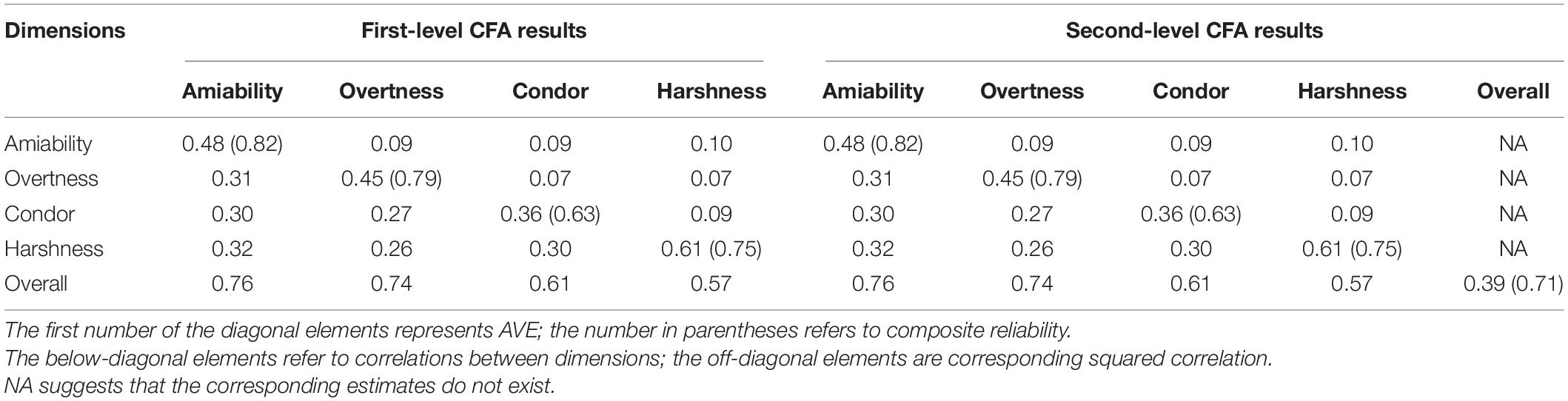

Our study introduces the “Internet slang style” to address this gap, defined as consumers’ schematic perception of the characteristics conveyed by the Internet slang expressions adopted in marketing-related contexts. Drawing upon relevant theories from psychology, communication, and marketing, we aim to contribute theoretically by: (1) establishing valid conceptualization of its definition and dimensions; (2) developing an adequate scale to measure it as a multi-dimensional construct; (3) exploring its possible marketing-relevant outcomes from a consumer perspective. To do so, we first derive the definition of Internet slang style and its dimensions based on an extensive literature review. A pilot study that involves consumer interviews validates these conceptualizations. Then, following scale-development procedures, four studies are conducted to develop the scale (Studies 1–2), examine its validity and reliability (Study 3), differentiate it from the brand personality scale ( Aaker, 1997 ), and reveal its influence on brand personality dimensions (Study 4). As far as we know, this is a very initial attempt to systematically conceptualize and empirically examine the characteristics of Internet slang, especially in the marketing domain. We also aim to contribute to practitioners by providing an easy-to-use instrument to evaluate Internet slang style.

Conceptualizing Internet Slang Style

Theoretical foundation: schema theory.

Internet slang, consisting of distinct pronunciation, word, morphology, and syntax derived from online context, is a variant of the standard language ( Liu et al., 2019 ). The emergence of Internet slang depends on two factors: its users and the context. On the one hand, netizens, active online for a long time, create and speak Internet slang instead of the standard language to express their unique identity. On the other, compared to real communication context, online communication is more accessible, random, and secretive, constructing a different environment for the continuous evolution of Internet slang as an independent variety.

As such, we draw from schema theory to clarify the conceptual nature of Internet slang style. Schema theory describes how people recognize and understand the world by using cognitive structures to organize prior knowledge ( Fiske, 1982 ). In this vein, schemata refer to the knowledge unit in the human mind, and an intermediary between objects and language. People organize schemata as a psychological structure network that represents shared meaning among many individuals. In the marketing context, this network allows individuals to form mental representations of ads, brands, or products, process, retrieve, and categorize information related to them, and finally facilitate decision-making ( Sujan and Bettman, 1989 ; Halkias, 2015 ).

Similarly, people with direct or indirect experiences with online communication will develop a cognitive representation of Internet slang. In other words, they establish prototypical knowledge and consensual meaning of this particular language variety, forming the “style” perception of Internet slang ( Jeffries and McIntyre, 2010 , p. 127). As people see similarities between events or experiences during processing, and weave them into different schema categories ( Schank, 1982 ), the “style” of Internet slang can also be further understood and measured based on the “types” of thematic meaning delivered.

Definition of Internet Slang Style in the Marketing Context

To the best of our knowledge, the literature contains no conceptually useful definition of Internet slang style and its dimensions that can be further extended to a scale and used in business practices. Therefore, the definition of Internet slang style should be first established before scale development. To achieve this purpose, we searched extensively to identify articles on “linguistic style,” “language style,” “communication style,” and “advertising style” published in leading journals that encompass communication or linguistic topics. By carefully understanding these articles, we tried to establish an appropriate framework to introduce the conceptualization of the Internet slang style.

Recent general conceptualizations in prior literature seem to coalesce around two streams of frameworks. On the one hand, the construct “communication style” emphasizes how people communicate with others. In this vein, communication style can be “conceived to mean the way one verbally and paraverbally interacts to signal how literal meaning should be taken, interpreted, filtered, or understood ( Norton, 1978 , p.99).” Prior research often uses this conceptualization to evaluate different ways that service providers use to interact with customers (e.g., Webster and Sundaram, 2009 ; Hwang and Park, 2018 ). On the other hand, “linguistic style,” or “language style,” reflects the linguistic nature of a word within a sentence structure, … and the meaning of a word provided by the semantics of the word and the rest of the sentence ( Hung and Guan, 2020 , p. 597). Operationalization of linguistic style usually relies on LIWC, a coding dictionary that categorizes nearly 6,400 words into 89 themes ( Pennebaker et al., 2015 ; Kovacs and Kleinbaum, 2020 ). Eighteen out of these 89 themes directly capture linguistic style, and can be used to predict intentions or personality traits (e.g., Lee et al., 2019 ; Koh et al., 2020 ).

General conceptualizations outlined in this section underlie divergent theoretical natures. Although linguistic styles are indeed psychologically-derived, their operationalization is based on specific linguistic features. For example, a social linguistic style is associated with the number of social intercourse-related words, such as family, employee, neighbor, and personal pronouns ( Lee et al., 2019 ). Therefore, the linguistic style framework cannot directly describe consumers’ perceptions of Internet slang as a unique language variety. Internet slang may contain very distinct elements or rules from the standard language and generate different consumer mindsets perceptions. By contrast, the framework of “communication styles” seems more in line with the essence of our intended definition of Internet slang style (i.e., the schema theory), as it emphasizes more on people’s schematic perceptions.

Responding to the argument that language features should be examined with consideration of social meanings embedded in the applied context ( Coupland, 2007 ; Moore, 2012 ), we aim to provide a conceptualization that encompasses the essence of Internet slang style specific to the marketing domain while still offering consistency with prior communication style literature. Therefore, in our research, we formally define Internet slang style as consumers’ schematic perception of the characteristics conveyed by the Internet slang expressions adopted in marketing-related contexts (e.g., in an advertisement, on the product package).

Dimensions of Internet Slang Style in the Marketing Context

As communication style plays as the conceptual basis for Internet slang style, we reviewed all the extracted articles again, focusing on possible dimensions of this scale. Generally, communication style consists of nine dimensions: dominant, dramatic, contentious, animated, impression-leaving, relaxed, attentive, open, and friendly ( Norton, 1978 ). However, in line with our aim of developing a parsimonious scale specific to the marketing domain, we determined whether some dimensions needed to be summarized or eliminated and whether additional components should be considered. Embedding Internet slang in the marketing context is not the same as communicating with others in everyday interactions. We, therefore, examined the unique features of Internet slang (especially those in the marketing context) to decide on possible dimensions for the conceptualization of Internet slang style.

The anti-conventional nature of Internet slang determines its originality ( Collot and Belmore, 1996 ; Liu et al., 2019 ). According to social information processing theory, netizens creatively employ verbal cues (e.g., foreign words, dialects, digital elements, and icons) and interaction strategies (e.g., paraphrasing, homonyms, thumbnails, reduplication, and unconventional syntax) to express and interpret social and emotional messages in online contexts ( Kundi et al., 2014 ; Valkenburg et al., 2016 ). In this way, Internet slang keeps gaining novelty and freshness. It allows its users, who are young and full of entertainment spirits, to generate more favorable and attractive impressions to similar others in computer-mediated communication ( Gao, 2006 ; Valkenburg and Peter, 2009 ). As a result, Internet slang may lead its users to cultivate psychological belongingness and familiarity.