Span identification and technique classification of propaganda in news articles

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2021

- Volume 8 , pages 3603–3612, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Wei Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2738-4350 1 ,

- Shiqian Li 1 ,

- Chenhao Liu 1 ,

- Longfei Lu 1 ,

- Ziyu Shi 1 &

- Shiping Wen 2

3304 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Propaganda is a rhetorical technique designed to serve a specific topic, which is often used purposefully in news article to achieve our intended purpose because of its specific psychological effect. Therefore, it is significant to be clear where and what propaganda techniques are used in the news for people to understand its theme efficiently during our daily lives. Recently, some relevant researches are proposed for propaganda detection but unsatisfactorily. As a result, detection of propaganda techniques in news articles is badly in need of research. In this paper, we are going to introduce our systems for detection of propaganda techniques in news articles, which is split into two tasks, Span Identification and Technique Classification. For these two tasks, we design a system based on the popular pretrained BERT model, respectively. Furthermore, we adopt the over-sampling and EDA strategies, propose a sentence-level feature concatenating method in our systems. Experiments on the dataset of about 550 news articles offered by SEMEVAL show that our systems perform state-of-the-art.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards an Ontology for Propaganda Detection in News Articles

Measuring populist discourse using semantic text analysis: a comment

Roel Popping

UlyssesSD-Br: Stance Detection in Brazilian Political Polls

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, with the development of related models in the field of natural language processing, research on propaganda detection also goes ahead, which originates from document level [ 1 ], then develops to sentence level [ 6 , 21 ] and now to fragment level [ 13 , 26 ]. At present, identifying those specific fragments which contain at least one propaganda technique and identifying the applied propaganda technique in the fragment are main tasks of the fragment-level propaganda detection. As an extension of text classification task in the field of natural language processing, there are many relevant advanced algorithms [ 8 , 10 , 12 , 19 , 27 ] which can be used for reference.

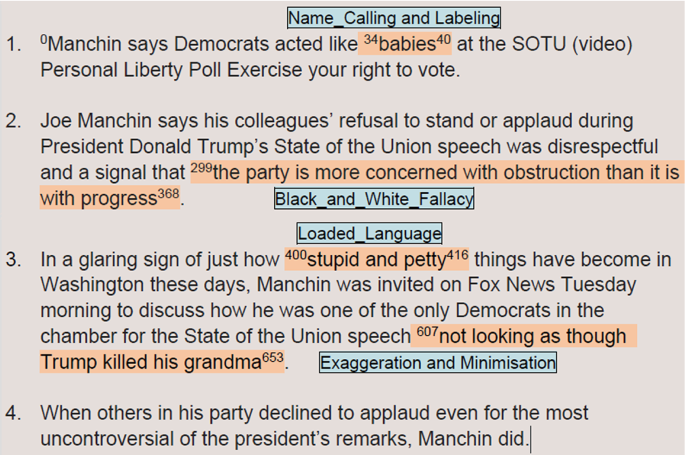

The corpus of news articles which have been retrieved with the newspaper 3k library and sentence splitting has been performed automatically with NLTK sentence splitter

SEMEVAL, the most influential and largest semantic evaluation competition all over the world, provides a news article corpus in which fragments containing one out of 14 propaganda techniques [ 14 , 18 ] have been annotated as shown in Fig. 1 . Based on this dataset, numerous researchers have sprung up putting forward a large quantity of algorithms to search the usages of propaganda techniques. Among the algorithms, the great mass of them are based on the popular language models such as ELMO [ 16 ], GPT [ 17 ] and especially BERT [ 3 ]. As shown in Fig. 2 , BERT Model raised by Google outperforms previous methods in 11 NLP tasks. Undoubtedly, it has achieved state-of-the-art performance on multiple NLP benchmarks [ 22 ]. In our systems, we choose BERT as our basic model as well.

In this work, we introduce our systems for span identification and technique classification of propaganda in news articles. As for the span identification task, we have set forth two of architectures working on it. The first is the BERT-based binary classifier, and the other one is the BERT-based three-token type classifier. The latter is our second-to-none system. Besides joining the most popular BERT model, we have also optimized the sampling [ 2 ] process, combined EDA [ 23 , 24 ] to prevent the overfitting of our system and adopted the sentence-level feature concatenating (SLFC), in which case our model can learn characteristics better. As for the technique classification of propaganda task, we have designed a BERT-based architecture with a dimensionality reduction Full Connected (FC) layer and a linear classifier. Same as SI task, we have utilized EDA strategy in the data loading process. The final result in “Experiment and results” shows that it is very meaningful of our optimizing and improving of the pre-trained BERT model. At last, both of our systems for SI and TC have exceeded most of the existed models and made a breakthrough.

The contributions of our paper are as follows:

We fine-tune the BERT with Linear layers and devise two accurate systems for the span identification and technique classification of propaganda in news articles.

We change the binary sequence tagging task SI into a three-way classification task by adding ’invalid’ token type and compare the binary tagging method with the three-token type method.

We propose SLFC approach in SI system. To our best knowledge, it is the first work to integrate sentence-level classification features into each word.

For our systems, we have obtained the optimal network parameters through experiments and comparative analysis.

Related work

The followings are the history and the correlative approaches about propaganda detection in news articles.

- Propaganda detection

Propaganda techniques detection is born in the process of fake news detection. Some of the earlier workers judge a news article as authentic or not only according to its origin. As we can imagine that this approach is unscientific. Recently, with the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning, propaganda detection has attracted researcher’s eyes which promotes it to become a standalone research field.

In the early days of NLP neural networks, a bidirectional long-term short-term memory (BiLSTM) [ 5 ] layer was proposed to capture the semantic features of human language. Gradually, people began to utilize it to detect the using of propaganda in news articles. Initially, a corpus has been created for news articles automatically annotated with a novel multi-granularity neural network which is superior to some powerful BERT-based baselines [ 14 ]. Simultaneously, Proppy [ 1 ], a system to unmask propaganda in online news, has appeared for document-level propaganda detection, which works by analysing various representations, from writing style and readability level to the presence of certain keywords. Later, to further improve the accuracy of detection, researchers began to pay attention to the detection of sentence level. Hou et al. proposed a model for sentence-level detecting which could understand semantic features of language better by constructing context-dependent input pairs (sentence-title pair and sentence-context pair) [ 6 ]. After the NLP4IF workshop, fragment-level classification (FLC) of propaganda occurred. For instance, different neural architectures (e.g., CNN, LSTM-CRF, and BERT) have been explored to further improve the effect of neural networks [ 15 ].

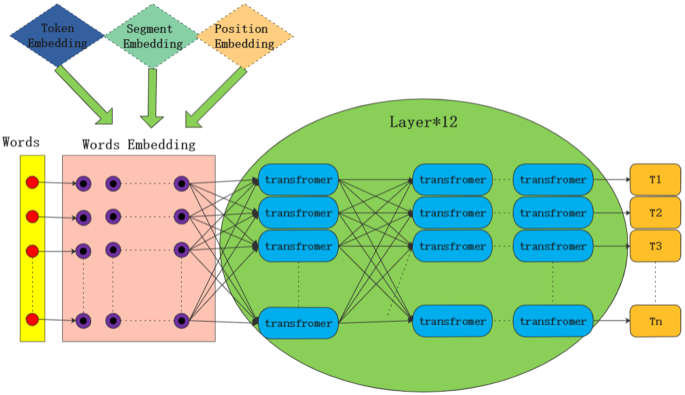

BERT-based model

In our experiment, we have been designing models specifically for SI and TC tasks based on BERT [ 3 , 4 ] model architecture, which incorporates the strength of the other language models. As shown in Fig. 2 , BERT utilizes the transformer’s attention mechanism [ 20 ] to decode the input word vector. Unlike the previous NLP models, BERT is able to run in parallel. More uniquely, the pre-training process of BERT includes two tasks, Masked Language Model (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP), which make the BERT model more suitable for NLP tasks. After completing different pre-training and fine-tuning for different tasks, BERT has made great progress on many NLP tasks. Many researchers have discovered the huge potential of the two-stage new model (pre-training and then fine-tuning) on BERT. As a consequence, in recent years, based on BERT, many improved models occurred, such as MT-DNN [ 7 ], XLNET [ 25 ], ALBERT [ 11 ], etc.

The architecture of the pre-trained BERT model with the Word Embedding layer for the gain of word vectors and 12-layer Encoders making up of parallel transformers for the fusion of semantic

In our system, using BERT is mainly for word feature extraction, thanks to that BERT adopts the popular feature extractor transformer, and also implements a bidirectional language model. It is the core concept of BERT to convert word into word vector input, which is added by Token Embedding, Segment Embedding, and Position Embedding to integrate the whole sentence semantics into each word in the same sentence. For our SI task, we process the obtained feature vector from BERT generator by incorporating sentence-level features into each word vector and then put it to a multi-class (prop, non-prop, invalid) classifier layer. To fit our TC task, we truncate the valid fragments and pad it for the latter FC layer and the classifier. Since there are two versions of BERT, taking our SI and TC tasks into account we use the 12-layer BERT pre-trained model as our basis.

In this section, we will introduce the details of our solutions and show the model architectures designed for the span identification (SI) and technique classification (TC) tasks.

Data process

S On account of that only a small portion of the texts use propaganda in SI and some of the techniques rarely appear in the given fragments in TC which lead to the imbalance of dataset, we have proposed two methods aimed at these two problems.

Over-sampling In the task of SI, we utilize the over-sampling (OS) [ 2 , 26 ] method to get more balanced and suitable dataset for training. Since sentences with propaganda techniques are relatively few, we sample them with a higher probability, and the number of non-propaganda ones is correspondingly reduced considering the whole training process. Nevertheless, during our experiment, we find that if over-sampling is overused, the labeled part will be too much in the sample which will cause overfitting, and the F1-score will decline to an undesirable level as a result. Therefore, when training our model, we take the strategy that the first half of the epoch uses the over-sampling and the latter part uses the sequential sampling. While TC is merely a classification task and each fragment in the given dataset corresponds to a specific propaganda technique, over-sampling is superfluous.

Data augmentation Since the pre-trained BERT model is easy to overfit, we have adopted a data augmentation scheme to improve the generalization ability and robustness [ 24 ] of the model. In the task of SI, we apply EDA Synonym Replacement (SR) [ 9 ] and Random Swap (RS) [ 23 ] to our model. Namely, each word has equal probability of being swapped or replaced by its synonyms without changing the label. Compared to short sentences, long sentences absorb more noise, which can better balance the dataset. After processing, sentences different from before are added to the training dataset. While in TC task, the data augmentation strategy is the same as that in SI which is a random process, initially. However, some of the techniques still cannot be detected such as Appeal_to_Authority, Bandwagon, Reductio_ad_hitlerum and Black-and-White_Fallacy. Aiming at this problem, on the basis of random data augmentation, we compulsively add them into the set to be data augmented. In this way, the purpose of increasing the valid noise of the training dataset is achieved. Meanwhile, the training time gets shortened as well.

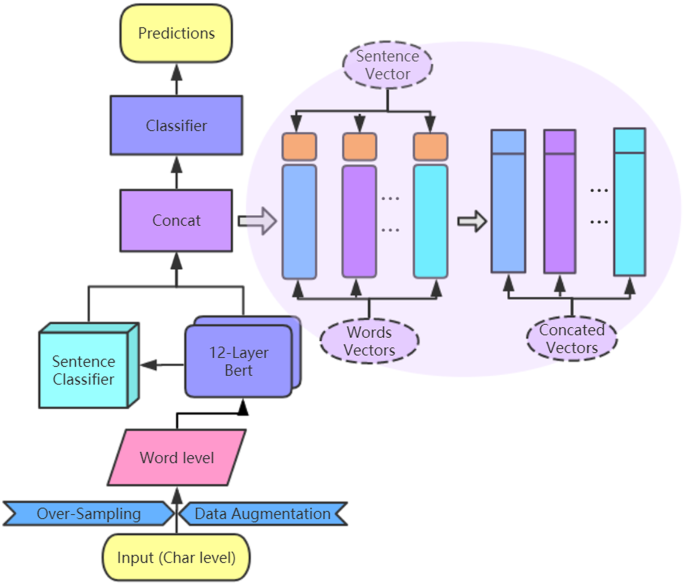

Approach of span identification (SI)

The architecture of Span Identification task adopting over-sampling, data augmentation and sentence-level feature concatenating. The Concat means adding the classification feature of the sentence to its every word vector

To deal with the SI task, we first defined it as a binary classification task [ 13 ], but after experiment we found Precision and F1-score of this solution were unexpected. After analyzing the cause and effect of this issue, we propose a three-classification model to classify each word in the news articles into three token types. The concrete architecture of our model is shown in Fig. 3 . Two of them are ‘prop’ and ‘non-prop’; the other one is ‘invalid’ which means the label of some invalid words like ‘CLS’, ‘SEP’ [ 3 ] and those used to ensure the input sentence with the same length. Classifying these invalid words into a ’invalid’ token type reduces the noise and improves Precision and F1-score. Furthermore, we have utilized sampling skill and EDA to optimize the dataset.

Due to that the labels of the plain-text document offered by SEMEVAL are at char level, converting them into word level for word embedding in pre-trained BERT model is the first step. Before inputting them into the classifier, we combine the word vectors in each sentence with the feature vector of the sentence where they are. Then the word vectors with semantic integration of the sentence are normalized for the last classifier layer. As shown in Figure 3 on the right, the concatenating process generates the new concatenated vectors by placing the sentence vector in front of the word vectors. The following formula ( 1 ) shows the concatenating process mathematically:

where \(s_1,s_2\) represent the elements in a sentence vector which contains the classifying result of sentence-level prediction. And the right matrix ( \(768\times 200\) ) contains 200 word vectors (768 dim) on behalf of one sentence. By concatenating, the input matrix ( \(770\times 200\) ) of the final classifier is made as the below one. This concatenating step is reasonable considering that sentence-level prediction is more undemanding and accurate than word-level prediction. The result also shows that concatenating step plays a key role in the promotion of word-level prediction accuracy. Finally, by merging the successive words with identical propaganda technique, those specific fragments which include at least one propaganda technique are identified.

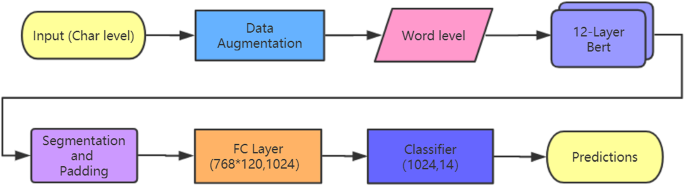

Approach of technique classification (TC)

For the multi-class classification task TC, we have utilized a Full Connection layer and a linear classifier based on BERT model, as shown in Fig. 4 . Since the dimension of the valid fragment vector is large, we utilize the former Full Connection layer for dimensionality reduction, and the second for classifying them into 14 classes. And we handle those propaganda techniques that rarely appear in the dataset by utilizing EDA so as to solve the imbalance of dataset. Comparing our model without and with EDA, the latter gets an improvement of around 4 points in F1 score as shown in Table 3 .

The architecture of Technique Classification task with segmentation and padding operations, an FC layer and a linear classifier layer

For details of TC task, we take the given text fragment identified as propaganda and its document context as the input of the pre-trained BERT generator. Different from SI task which is a word-level classification task, the TC task is fragment-level. Hence, incorporating sentence-level features into each word vector is ineffectual for TC task. As for the fragment which belongs to several sentences, we divide it into different sentences in the training process, while evaluating we treat it as a whole. Then for the sake of obtaining the valid fragment with propaganda techniques, we make segmentation of the output of BERT and pad it with invalid zero vector to a settled length (120). With the dimensionality reduction of our Full Connection layer, a linear classifier is used for 14 token types classification.

Experiment and results

In this section, we will show the experiment details and the achieved experiment results by comparing our surpassing systems respectively for SI and TC to several other attempts.

Experiment details

In our experiment, we have trained our models parallelly with 4 Nvidia GTX 1080Ti GPUs to reduce the time required. Based on the PyTorch Framework and CrossEntropy Optimizer [ 28 ] (after trying the focal loss), we have fine-tuned the pre-trained BERT model for our SI and TC tasks.

Dataset The datasets for both of the SI and TC tasks are news articles in plain text format, including train-articles, dev-articles and the label files. To begin with, we have split each article into individual sentences to reduce parameters of our model. And before the experiment, we divided the annotated corpus of about 550 articles into 80% train set for model training and 20% test set for model evaluation, respectively. By calculating the instances of each technique, we find that the dataset for TC is imbalanced as shown in Table 1 . Some of the techniques such as “Loaded_Language” has a high proportion of 34.64%, while some of the techniques such as “Black-and-White_Fallacy”, “Slogans” and “Whataboutism, Straw_Men, Red_Herring” show up less often. What is worse, neither “Bandwagon, Reductio_ad_hitlerum” nor “Thought-terminating_Cliches” has no more than 80 instances which may badly influence the training process. During training, in order to enhance the generalization capability of our model, we utilized EDA to make train set extended and more well-proportioned. Besides, particularly for SI task, we adopted the over-sampling strategy for tagged sentences.

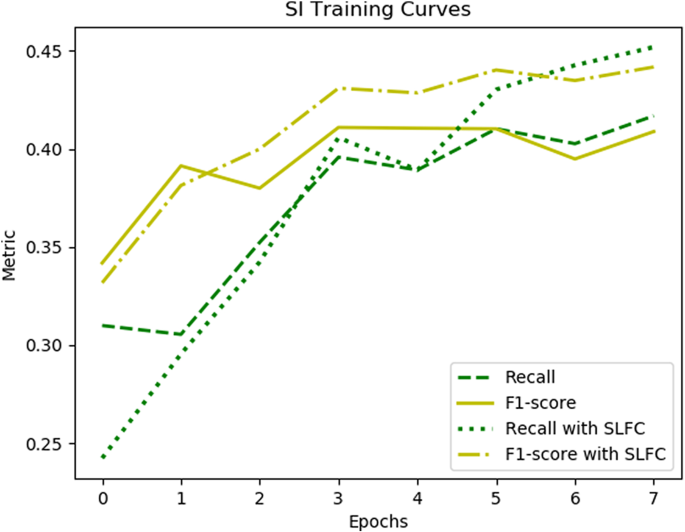

The comparison of SI training process between our systems with and without SLFC

Evaluation metric So as to make a fair comparison, we use different evaluation criteria in different comparison experiment. For both of SI and TC tasks, we adopt the F1-score (F1) as the main metric. In addition, the general Precision (P) and Recall (R) are the secondary metric for SI task. The F1-score is denoted by the following formula:

Results: span identification (SI)

For the purpose of achieving the SI task, we have presented two diverse architectures and optimized one of them with over-sampling, EDA, and sentence-level feature concatenating (SLFC). As is shown in Table 2 , our top perform system is three-token type classification system with Over-sampling, EDA and SLFC. We have contrasted our SI system with BERT-based Binary classifier model, and BERT-based Three-token type classifier model.

As we have seen, the BERT-based three-token type classifier reaching 40.8815% F1-score, 40.1099% Precision and 41.6834% Recall behaves better than baseline which is merely BERT-based with no fine tuning and the Binary classifier model. We owe this success to the ’invalid’ token type which impairs the noise of the invalid words by classifying the irrelevant words individually. Besides, after using EDA, it only took two epochs or so to reach the peak of the Recall, without which it took about six epochs to reach the peak and the results were not as expected. Ultimately, our SI system, based on our three-token type classifier and utilizing our strategies of over-sampling, EDA and SLFC, prevails over others, which scores 44.1732% of F1-score on the test set.

Next, we will give a deep analysis of the usage of SLFC and how it benefits our system on Recall and F1-score shown in Fig. 5 . Generally speaking, the word-level prediction requires more accurate detection and there is a bigger margin of error than sentence-level prediction, which is why we give each word more information about whether the sentence it is in has propaganda with the aid of SLFC. Namely, the sentence classification prediction provides reference for the word prediction. If a sentence is propagandistic, it is of high probability containing propaganda fragments. On the contrary, if a sentence is non-propagandistic, the words in it are not of propagandistic as well. Based on this knowledge, we successively apply SLFC to our model, which does increase the F1-score by around three points and the Recall by around four points, respectively. Meanwhile, the precision does not decrease significantly. All in all, compared with no SLFC, our system identifies the propaganda spans more accurate which consequently promotes the F1-score and Recall.

Results: technique classification (TC)

To better complete the TC task, we have presented two architectures, one without EDA and another with EDA. Comparing them with the baseline which is merely BERT-based with no fine tuning, both of our systems with EDA or not have reached a new high state, improving the F1-score by two times approximately as shown in Table 3 . During our experiment, we have made an experimental comparison and analysis for our strategy of utilizing EDA in the data loading process of our TC system. The final result has indicated that our TC system with EDA improved F1-score by around 3% compared to the absent EDA system. It stands to reason that our TC system reaches the state-of-the-art in the end, which scores 57.5729% of F1-score on the test set.

The respective promotions with EDA strategy in F1-score for each of propaganda technique are shown in Table 4 . Compared with our no EDA model, in spite of the fact that three of techniques (‘Doubt’, ‘Flag-Waving’, and ‘Whataboutism, Straw_Men, Red_Herring’) have slightly decreased to some extent, more than half of the techniques have made progress in F1-score. For details, most of them have gotten about eight-point improvement on average, such as ‘Appeal_to_fear-prejudice’, ‘Exaggeration, Minimisation’, ‘Repetition’ and so on. What is worth mentioning is that the techniques named ‘Causal_Oversimplification’ and ‘Thought-terminating_Cliches’ have gotten about 14-point improvement. Thus, our TC system makes many breakthroughs on the whole, giving the credit to EDA which can enhance the data set, prompt the model to converge faster and improve the generalization ability and robustness of the model.

Parameter analysis

After a series of experiments, we have given a set of optimal parameters [epoch, learning rate (lr), sentence length (sent-len)] for the models of the two tasks. The optimal parameter combinations are shown in bold in Table 5 .

For the sentence length, which is the length of the single input into the BERT and is usually set to 256, we have set it to 200 and 210 for our SI and TC tasks, respectively. In SI task, it is attributed to that the whole sentences in dataset do not exceed 200 in length, and too much padding will lead to greater classification error. As for TC task, the maximum length of valid fragments in the dataset is 210, so we choose it as the limit for padding. In terms of learning rate, both of our choices are 3 \(\times 10^{-5}\) because our valid dataset is small. Through the analysis of the SLFC method for SI task in Sect. 4.2 , we have found that the model began to converge around the epoch 7, so we set the training epoch to 8 to prevent overfitting in our SI system. Besides, in the experiment process of TC task, we have found the epoch parameter greater than 15 caused F1-score decreased, so we set it as the best choice for our TC system. Based on the above optimal parameters, our SI and TC systems finally obtained the F1-score of 0.441732 and 0.575729, and both of the training processes have taken around 2.5 h using 4 Nvidia GTX 1080Ti graphics cards (i.e. around 10 GPU hours).

Conclusion and future work

Based on the BERT model, we have set forth two specific systems for Span Identification and Technique Classification of Propaganda in news articles. In the data loading process, we have tried two strategies, over-sampling in SI task and EDA in both of SI and TC tasks, in order to deal with the imbalance between data with and without tags and enlarge our training dataset. For SI task, we have afresh defined it as a three-token type sequence tagging task with our SI system, and adopted sentence-level feature concatenating method. For TC task, we have devised a system based on BERT with a dimensionality reduction FC layer and a linear classifier. Ultimately, we have achieved two efficient and accurate systems for propaganda detection in news articles. And the final result also confirmed that our research further perfects the BERT model.

In the future, we are going to improve the Precision, Recall and F1-score further by drawing lessons from the SpanBERT model, which may perform better. Namely, in the process of masking, we would like to cover consecutive words randomly instead of scattered words. And we are thinking about searching for a more suitable architecture of BERT adopting the popular Neural Architecture Search (NAS). Besides, we hope our model can be compressed to some extent. For instance, we can prune the classifier layer, quantify or share the parameters of our model. In these cases our model can be applied widely and conveniently in our daily lives.

Barron-Cedeno A, Da San Martino G, Jaradat I, Nakov P (2019) Proppy: a system to unmask propaganda in online news. In: Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pp 9847–9848

Corney D, Albakour D, Martinez-Alvarez M, Moussa S (2016) What do a million news articles look like? In: NewsIR@ ECIR, pp 42–47

Devlin J, Chang M.W, Lee K, Toutanova K (2018) Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics

Fadel A, Tuffaha I, Al-Ayyoub M (2019) Pretrained ensemble learning for fine-grained propaganda detection. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda, pp 139–142

Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J (1997) Long short-term memory. Neural Comput:1735–1780

Hou W, Chen Y (2019) Caunlp at nlp4if 2019 shared task: context-dependent bert for sentence-level propaganda detection. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda, pp 83–86

Huang Y, Wang W, Wang L, Tan T (2013) Multi-task deep neural network for multi-label learning. In: 2013 IEEE International conference on image processing, pp 2897–2900

Khalid A, Khan FA, Imran M, Alharbi M, Khan M, Ahmad A, Jeon G (2019) Reference terms identification of cited articles as topics from citation contexts. Comput Electr Eng 74:569–580

Article Google Scholar

Kobayashi, S (2018) Contextual augmentation: data augmentation by words with paradigmatic relations. North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics, pp 452–457

Kurian D, Sattari F, Lefsrud L, Ma Y (2020) Using machine learning and keyword analysis to analyze incidents and reduce risk in oil sands operations. Saf Sci

Lan Z, Chen M, Goodman S, Gimpel K, Sharma P, Soricut R (2020) Albert: a lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. ICLR

Liu S, Lee K, Lee I (2020) Document-level multi-topic sentiment classification of email data with bilstm and data augmentation. Knowl Based Syst:105918

Mapes N, White A, Medury R, Dua S (2019) Divisive language and propaganda detection using multi-head attention transformers with deep learning bert-based language models for binary classification. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda, pp 103–106

Martino DSG, Yu S, Barron-Cedeno A, Petrov R, Nakov P (2019) Fine-grained analysis of propaganda in news articles. EMNLP/IJCNLP 1:5635–5645

Google Scholar

Pankaj G, Khushbu S, Usama Y, Thomas R, Hinrich S (2019) Neural architectures for fine-grained propaganda detection in news. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda

Peters E.M, Neumann M, Iyyer M, Gardner M, Clark C, Lee K, Zettlemoyer S.L (2018) Deep contextualized word representations. North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics

Radford A, Narasimhan K, Salimans T, Sutskever I (2018) Improving language understanding by generative pretraining

San G.D.M, Alberto B.C, Preslav N (2019) Findings of the nlp4if-2019 shared task on fine-grained propaganda detection. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda

Tchiehe N.D, Gauthier F (2017) Classification of risk acceptability and risk tolerability factors in occupational health and safety. Saf Sci:138–147

Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez N.A, Kaiser L, Polosukhin I (2017) Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (NIPS 2017), pp 5998–6008

Vlad G.A, Tanase M.A, Onose C, Cercel D.C (2019) Sentence-level propaganda detection in news articles with transfer learning and bert-bilstm-capsule model. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda, pp 148–154

Wang A, Singh A, Michael J, Hill F, Levy O, Bowman R.S (2018) Glue: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. In: International conference on learning representations

Wei WJ, Zou K (2019) Eda: easy data augmentation techniques for boosting performance on text classification tasks. EMNLP/IJCNLP 1:6381–6387

Xie Z, Wang I.S, Li J, Lévy D, Nie A, Jurafsky D, Ng Y.A (2017) Data noising as smoothing in neural network language models. ICLR

Yang Z, Dai Z, Yang Y, Carbonell GJ, Salakhutdinov R, Le VQ (2019) Xlnet: generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (NIPS 2019), pp 5754–5764

Yoosuf S, Yang Y (2019) Fine-grained propaganda detection with fine-tuned bert. In: Proceedings of the second workshop on natural language processing for internet freedom: censorship, disinformation, and propaganda, pp 87–91

Zhan Z, Hou Z, Yang Q, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Hu C (2020) Knowledge attention sandwich neural network for text classification. Neurocomputing:1–11

Zhang Z, Sabuncu M (2018) Generalized cross entropy loss for training deep neural networks with noisy labels. In: Advances in neural information processing systems, pp 8778–8788

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Wei Li, Shiqian Li, Chenhao Liu, Longfei Lu & Ziyu Shi

University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, Australia

Shiping Wen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wei Li .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Li, W., Li, S., Liu, C. et al. Span identification and technique classification of propaganda in news articles. Complex Intell. Syst. 8 , 3603–3612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-021-00393-y

Download citation

Received : 18 March 2021

Accepted : 30 April 2021

Published : 08 May 2021

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-021-00393-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Neural network

- Span identification

- Technique classification

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies

Jonathan Auerbach, University of Maryland

Russ Castronovo is Dorothy Draheim Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is author of three books: Fathering the Nation: American Genealogies of Slavery and Freedom; Necro Citizenship: Death, Eroticism, and the Public Sphere in the Nineteenth-Century United States; and Beautiful Democracy: Aesthetics and Anarchy in a Global Era. He is also editor of Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics (with Dana Nelson) and States of Emergency: The Object of American Studies (with Susan Gillman).

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This handbook includes 23 essays by leading scholars from a variety of disciplines, divided into three sections: (1) Histories and Nationalities, (2) Institutions and Practices, and (3) Theories and Methodologies. In addition to dealing with the thorny question of definition, the handbook takes up an expansive set of assumptions and a full range of approaches that move propaganda beyond political campaigns and warfare to examine a wide array of cultural contexts and practices.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, propaganda analysis in social media: a bibliometric review.

Information Discovery and Delivery

ISSN : 2398-6247

Article publication date: 27 January 2021

Issue publication date: 18 February 2021

This paper aims to examine the trends in research studies in the past decade which address the use and analysis of propaganda in social media using natural language processing. The purpose of this study is to conduct a comprehensive bibliometric review of studies focusing on the use, identification and analysis of propaganda in social media.

Design/methodology/approach

This work investigates and examines the research papers acquired from the Scopus database which has huge number of peer reviewed literature and also provides interfaces to access required for bibliometric study. This paper has covered subject papers from 2010 to early 2020 and using tools such as VOSviewer and Biblioshiny.

This bibliometric survey shows that propaganda in social media is more studied in the area of social sciences, and the field of computer science is catching up. The evolution of research for propaganda in social media shows positive trends. This subject is primarily rooted in the social sciences. Also this subject has shown a recent shift in the area of computer science. The keyword analysis shows that the propaganda in social media is being studied in conjunction with issues such as fake news, political astroturfing, terrorism and radicalization.

Research limitations/implications

The lack of highly cited papers and co-citation analysis implies intermittent contributions by the researchers. Propaganda in social media is becoming a global phenomenon, and ill effects of this are evident in developing countries as well. This denotes a great deal of scope of work for researchers in other countries focusing on their territorial issues. This study was conducted in the confines of data captured from the Scopus database. Hence, it should be noted that some vital publications in recent times could not be included in this study.

Originality/value

The uniqueness of this work is that a thorough bibliometric analysis of the topic is demonstrated using several forms such as mind map, co-occurrence, co-citations, Sankey plot and topic dendrograms by using bibliometric tools such as VOSviewer and Biblioshiny.

- Social media

- Social media analysis

- Bibliometrics analysis

- Propaganda detection

Chaudhari, D.D. and Pawar, A.V. (2021), "Propaganda analysis in social media: a bibliometric review", Information Discovery and Delivery , Vol. 49 No. 1, pp. 57-70. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-06-2020-0065

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Special Issue: Propaganda

This essay was published as part of the Special Issue “Propaganda Analysis Revisited”, guest-edited by Dr. A. J. Bauer (Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism and Creative Media, University of Alabama) and Dr. Anthony Nadler (Associate Professor, Department of Communication and Media Studies, Ursinus College).

Peer Reviewed

“A most mischievous word”: Neil Postman’s approach to propaganda education

Article metrics.

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Before there was a term called media literacy education, there was an interdisciplinary group of writers and thinkers who taught people to guard themselves against the manipulative power of language. One of the leaders of this group was Neil Postman, known for his best-selling book published in 1985, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Early in his career, Postman promoted a pedagogy of teaching and learning about language, media, and culture. In defining propaganda as “a most mischievous word,” Postman aimed to heighten learners’ attention on the abstracting function of language and its capacity to reshape attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge.

Harrington School of Communication and Media, University of Rhode Island, USA

Research Questions

- What concepts and instructional practices did Neil Postman use to help people learn to critically analyze contemporary propaganda?

- How does Postman’s exploration of language and meaning fit into the larger history of media literacy education?

Essay Summary

- Postman defines propaganda as intentionally designed communication that invites people to respond emotionally, immediately, and in an either-or manner, emphasizing its capacity to undo more reasoned habits of mind. By defining propaganda in relation to its form, context, and impact on audiences, Postman acknowledges that propaganda is present in many forms of contemporary media, including entertainment, information, and persuasion.

- Postman’s pedagogy builds upon literary close reading practices, and he uses comparison contrast to examine an example of emotion-laden propaganda and compare it with another form of expression that purports to be more informational. Transparent and emotionally evocative propaganda is not to be feared, Postman explains. But when propaganda is not transparent about its aims, when it uses language in ways that distort reality, it can be harmful, even when its intentions are well-meaning and designed to support a worthy cause.

- Through the strategic selection of propaganda artifacts, educators may provoke learners in ways that enable dialogue and discussion to contribute towards the building of a community of inquiry. From this, learners gain awareness of the value of encountering multiple, diverse, and conflicting interpretations of media messages. As a result, pedagogies rooted in discussion and dialogue contribute to civic education.

- Although Postman advocated for dialogue and discussion as a primary pedagogy, he acknowledged the importance of students learning to use the power of information and communication to make a difference in the world. By creating propaganda, students learn about the social responsibilities of digital authorship.

Implications

As an effort to help learners of all ages navigate increasingly complex media and information ecosystems, the pedagogy of media literacy has a long intellectual history. Although the term “media literacy” only became widely used during the 1990s, ideas underpinning its practice were germinating during the early part of the 20 th century, when many philosophers, writers, critics, and academics were exploring the difficulties of living in a symbolic world replete with mass media and communication. Scholars including Kenneth Burke, Aldous Huxley, Alfred North Whitehead, Ludwig Wittgenstein, C. S. Peirce, John Dewey, Ernest Cassirer, Edward Sapir, and I. A. Richards all offered ideas about the relationship between expression, media, education, and democracy that influenced the work of later educators and scholars who developed and used the term media literacy (Hobbs, 2016).

In the 1930s, as fascism grew in Europe and around the world, scholars noted that although humans’ use of language enabled vast innovation, it also put people at tremendous risk from the harmful propaganda of demagogues and dictators. Educators were fascinated with the challenge of teaching about contemporary propaganda in the years leading up to World War II, as film and radio offered new ways to combine entertainment, information, and persuasion. The Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) offered monthly publications to educators who were urged to help people recognize the rhetorical strategies used by propagandists (Miller & Edwards, 1936). Based in New York City, the organization had active correspondence with high school teachers from across the region and across the nation. More than 1 million students participated in IPA learning activities on the topic of propaganda. Although the IPA folded at the onset of American involvement in the war, many teachers continued to teach students how to recognize “glittering generalities,” “card stacking,” and “bandwagon” and other rhetorical appeals (Hobbs & McGee, 2014). Although we don’t know for certain, Neil Postman himself may have learned to identify propaganda techniques as a high school student in New York City public schools.

Neil Postman, known for his best-selling book published in 1985, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, influenced a generation of media literacy educators with his insights on inquiry learning in and out of schools, the role of technology in shaping culture and values, and the narratives that underpin the aims of education. Early in his career, Postman promoted a pedagogy of teaching and learning about language, media, and culture that focused on the systematic analysis and exploration of modes of communication (Postman, 1974a), which he termed media ecology (Postman, 1974b). But how does Postman’s work on propaganda fit into the history of media literacy and propaganda education?

Actually, Postman’s interest in propaganda was incidental to a much larger narrative, situated at the blurry intersections of the humanities, media studies, and education. Well before he became a media scholar, Postman was a teacher and teacher educator (Postman, 1958; 1961). Postman’s work demonstrates the central practice of the critical analysis of language (Postman, 1976), using specific media texts or artifacts of popular culture. In examining Postman’s approach to teaching propaganda in the 1970s in the years leading up to his formulation of the scholarly practice of media ecology, there are some themes in his work that have implications for how propaganda education is currently conceptualized within contemporary dialogues about media literacy education. When media artifacts are strategically chosen by the instructor, they may provoke learners into genuine thinking (Postman, 1979). The resulting dialogue, discussion, and creative expression in the classroom enable students to recognize the active process of meaning-making and interpretation. Such pedagogies may cultivate communities of inquiry that embody the collaborative practices of engaged citizenship (Kahne & Bowyer, 2019). For these reasons, Postman’s close analysis of 20 th -century propaganda offers some value for today’s educators seeking to help learners thrive in a culture saturated with new forms of digital propaganda.

The pedagogy of media literacy education is rooted in the practices of critical reading and creative media production, where a focus on media and popular culture enables rich connections between classroom and contemporary culture (Hobbs, 2010). These practices were foundational to Neil Postman’s pedagogy and stemmed from his background in English education (Thaler, 2003). Following in the footsteps of Marshall McLuhan (1960), Postman emphasized the value of using topics, issues, and materials that were relevant to children and young people (Postman, 1995). Like McLuhan, Postman included examples from advertising, news, music, and even fashion, conflating city and classroom (Mason, 2016). By emphasizing the interconnectedness of technology, communication, art, and symbolic forms, both Postman and McLuhan wanted to help people better “understand the past, make sense out of the present, and provide us with the best hope of anticipating and planning for the future” (Strate, 2017, p. 245).

Because propaganda comes in many diverse genres and forms (including public service announcements, political campaigns, news media, movies, memes, and social media, just to name a few) it provides a rich array of opportunities for learners to engage in sense-making using strategies of reasoning and interpretation. Sadly, the scholarly literature on literacy education still makes little acknowledgement of the fact that advertising and propaganda are persuasive genres that demand different types of critical reading practices than texts whose purpose is primarily informational (Hobbs, 2020a). To interpret persuasive genres, learners must be attentive to the emotional dimensions of messages as they make inferences about audience interpretation and authorial intent. They must imagine the potential impact and consequences of messages upon different viewers, readers, or listeners. By identifying the target audience and rhetorical appeals used to construct a message, learners come to appreciate how propaganda engages the active participation of audiences, whose hopes, fears, and dreams are addressed through symbolic expression.

Long before terms such as implicit bias and confirmation bias were formulated, Postman articulated how dialogue and discussion activities increase learners’ awareness of how their own beliefs and prior knowledge might lead them to differentially interpret the meaning, quality, utility, and value of propaganda that can be found in information, entertainment, and persuasion. Moreover, as learners interpret and analyze propaganda, conversations inevitably get into deeper terrain, opening up ethical issues including the changing nature of knowledge, the limits of human freedom, and the role of propaganda in gaining and maintaining social and institutional power (Hobbs, 2020b).

Postman understood that the motives of the propagandist were inherently unknowable and that even propaganda that is designed to support or advance a worthy cause can be harmful when it distorts people’s understanding of social reality. Building on the work of Jacques Ellul (1979), Postman recognized that moral and ethical judgments about the relative benefits and potential harms of propaganda are baked into the interpretation process. For this reason, people need advanced skills of interpretation and analysis because of the linguistic and epistemic mischief caused by propaganda, which can create “a thicket of unreality” (Boorstin, 1961, p. 3).

Writing at a time before email and the Internet were becoming ubiquitous, Postman recognized that information technologies were creating a culture “without moral foundation” by altering our understanding of what is real (Postman, 1994). He noted that every tool has an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing rather than another. For today’s learners, understanding the propaganda function of algorithmic personalization may lead to a deeper consideration of texts that tap into audience values for aesthetic, commercial, and political purposes (Hobbs, 2020a). But these competencies and skills cannot merely be transmitted through a teacher’s lecture. They must be cultivated through active participation in a discourse community.

Recently, there has been a call for media literacy education to focus less on knowledge and skills and more on “connecting humans, embracing differences” through relational activities, where the process matters as much as the outcome (Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017, p. 451). As my analysis of Postman’s lesson reveals, media literacy education has long been conceptualized as a dimension of civic education; indeed, much of Postman’s writing about education emphasizes its role in the construction of community, where the critical analysis of media messages is explicitly presented as a collaborative practice of citizenship, designed to advance the exercise of democratic rights and civil responsibilities. For example, in a brilliantly titled book, Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1969), Postman and Weingartner explain how inquiry-learning pedagogies advance learner confidence and autonomy by empowering students to take responsibility for their own interpretations of the symbolic environment. In their formulation of inquiry learning, the teacher rarely tells students a personal opinion about a particular social or political issue and does not accept a single statement as an answer to a question. The teacher encourages student-to-student interaction as opposed to student-to-teacher interaction and the teacher generally avoids acting as a mediator or judge. Lessons develop from the interests and responses of students and not from a predetermined curriculum.