An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sensors (Basel)

Internet of Multimedia Things (IoMT): Opportunities, Challenges and Solutions

Yousaf bin zikria.

1 Department of Information and Communication Engineering, Yeungnam University, 280 Daehak-Ro, Gyeongsan, Gyeongbuk 38541, Korea; moc.liamg@airkiznibfasuoy

Muhammad Khalil Afzal

2 COMSATS University Islamabad, Wah Campus, Wah Cantt 47010, Pakistan; kp.ude.hawtiic@lazfalilahk

Sung Won Kim

With the immersive growth of the Internet of Things (IoT) and real-time adaptability, quality of life for people is improving. IoT applications are diverse in nature and one crucial aspect of it is multimedia sensors and devices. These IoT multimedia devices form the Internet of Multimedia Things (IoMT). It generates a massive volume of data with different characteristics and requirements than the IoT. The real-time deployment scenarios vary from smart traffic monitoring to smart hospitals. Hence, Timely delivery of IoMT data and decision making is critical as it directly involves the safety of human beings. In this paper, we present a brief overview of IoMT and future research directions. Afterward, we provide an overview of the accepted articles in our special issue on the IoMT: Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions.

1. Introduction

Internet of Things (IoT) devices has limited memory and processing capabilities [ 1 ]. Hence, these constrained devices rely upon efficient routing protocols [ 2 ] and standardized communication stack [ 3 ]. Technological advancements in 5G [ 4 ], intelligent 5G-based IoT [ 5 ], IoT operating systems (OS) [ 6 ], data-driven intelligence in wireless networks [ 7 ], scheduling approaches for heterogeneous content-centric IoT [ 8 ], congestion avoidance techniques in IoT using data science [ 9 ], vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETS) [ 10 ], Information-centric networks (ICN) [ 11 ], reinforcement learning-based solutions for next-generation networks [ 12 , 13 ], coexistence networks [ 14 ], IoT adaptation in agriculture [ 15 ] and Healthcare IoT [ 16 ] are helping to realize to connect everything and anywhere.

Internet of Multimedia Things (IoMT) devices are different from IoT devices. It requires bigger memory, higher computational power, and more power-hungry with higher bandwidth [ 17 ]. Figure 1 shows the key data characteristics of IoT and IoMT. The real-time deployment scenarios vary from industrial IoT, Smart cities, Smart hospitals, smart grid, smart agriculture, and smart homes. The main characteristic of IoMT is the timely and reliable delivery of the data. Therefore, it imposes strict quality of service (QoS) requirements and demands efficient network architecture. The users perspective of QoS is known as quality of experience (QoE). QoE can be further characterized as objective or subjective. The users Objective QoE is challenging to measure and dramatically varies according to the needs. However, service providers concern with the subjective QoE to evaluate the network mean opinion score (MOS). The multimedia data is increasing multifold. It raises new challenges to transmit, process, store and share the data. Processing requires new techniques for edge, fog and cloud devices. Further compression and decompression techniques are introduced for the storage of multimedia data. Routing protocol for low-power and lossy networks (RPL) is the standard IoT routing protocol. It needs further development by considering energy-aware, load balancing, fault tolerance, and delay aware IoMT deployment scenarios.

Key Data Characteristics of IoT and IoMT.

IoT characteristics support multimedia communications; however, multimedia applications are bandwidth-hungry and delay-sensitive. The rapid growth of multimedia traffic in IoT has led the way to innovating new techniques to meet its requirements. IoMT devices require higher bandwidth, bigger memory, and faster computational resources to process data. Typical communications include multipoint-to-point and multipoint-to-multipoint scenarios. Real-world multimedia applications include emergency response systems, traffic monitoring, crime inspection, smart cities, smart homes, smart hospitals, smart agriculture, surveillance systems, Internet of bodies (IoB), and Industrial IoT (IIoT). Dynamic networks, heterogeneous devices and data, strict QoS, and delay sensitivity and reliability requirements over resource-constrained IoMT pose humongous challenges for multimedia communication in IoT. Network-on-chip architecture [ 18 , 19 ] is one of the viable solution to improve the user quality of experience. Figure 2 shows versatile IoMT applications.

IoMT Applications.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides future research directions. Section 3 summarizes the accepted paper. Finally, Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Future Research Directions

Molecular communication exploits the transmission and reception of information encoded in molecules. Molecular communications have the potential of becoming the main technology for the execution of advanced medical solutions. The key research challenges in the molecular communication are the interoperability between molecular communication and the other networks, energy-efficient models and protocols for molecular communication, and implantation of reliability in the molecular communication.

Billions of resource constraint devices will be connected in the IoT. The available spectrum is far from enough to support IoT communication systems. Optimal resource allocation for critical multimedia traffic is a key challenge for IoMT. The use of artificial intelligence (machine learning, deep learning) can improve the energy-efficient resource allocation in IoMT.

Device-to-device (D2D) communication in LTE-A will establish direct communication with the device in its communication range. Potential advantages of D2D communication are increased network spectral efficiency, energy efficiency, reduced transmission delay, traffic offloaded base station, and less congestion in the cellular core network. IoMT can take the benefits of the advantages provided by D2D communication. Interference, radio resource allocation, power control, and QoE improvement for cellular users are the key research areas in D2D communication for IoMT.

Energy Efficient Operation and Protocols are the key requirement of IoMT. Many multimedia traffic sources in IoMT may rely on battery-powered sources with limited energy and/or may not be easily accessible for recharging purposes. Similar to WSNs/IoT, the energy-efficient operation, protocols design (i.e., medium access control and routing protocols), and the need to optimize the network lifetime remains a critical challenge for IoMT. Based on the specific application and deployment environment, energy-efficient protocols can be designed for IoMT.

The Internet of Multimedia Nano-Things (IoMNT) is defined as the interconnection of multimedia nano-devices with communication networks and the Internet. The potential applications of IoMNT are security, biomedical, defense, and industry. The main research challenges in IoMNT includes novel medium access control techniques, addressing schemes, neighbor discovery and routing schemes, QoS-aware cross-layer communication module and security solutions for the IoMNT.

Multimedia-oriented IoT over vehicular networks is increasing drastically. Today, vehicles have the capability of supporting real-time acquisition and transmission of the multimedia traffic generated by the built-in IoT devices. However, due to high mobility, density, and random wireless channel conditions, the performance of the delivery of multimedia contents significantly reduces in vehicular networks. Rate adaptation, multimedia delivery over heterogeneous devices, robust video encoding, scalable, and timely delivery of multimedia contents are the key research challenges in IoMT over vehicular networks.

3. A Brief Review of Articles of This Special Issue

The immense growth in multimedia traffic over the scarce licensed cellular spectrum has inspired to use unlicensed spectrum below 6 GHz for Long Term Evolution (LTE). However, Wi-Fi uses the same unlicensed band, and this gives rise to the issue of coexistence and fairness of two different technologies in the context of physical and link layer protocols. LTE in the Unlicensed (LTE-U) and LTE License Assisted Access (LTE-LAA) has been proposed in the literature for IoT system. The Third Generation Partnership (3GPP) has standardized LAA for industrial IoT. The coexistence mechanism of LAA follows Listen Before Talk (LBT), which is the same process of Wi-Fi system coexistence i.e., Carrier Sense Multiple Access (CSMA). LTE-U operates a carrier ON/OFF switch policy in duty cycles to maintain fairness in LTE and Wi-Fi transmissions. This mechanism causes spectrum inefficiency. Bajracharya et al. [ 20 ] proposed a Machine Learning (ML)-based Adaptive Duty Cycle (ADC) and Dynamic Channel Switch (DCS) mechanism for network to access channel in dynamic network scenarios. ADC and DCS exploit Q-learning to determine the best policy to select an optimal channel and duty cycles. ADC reserve a specific number of sub-frames for Wi-Fi, whereas DCS avoids congested channels for LTE-U users. Performance evaluations are presented in comparison with the fixed duty cycle and channel occupancy time approach. Results show that their proposed method outperforms other methods in the context of fairness and throughput.

With the exponential growth of the IoT, the interaction of multiple physical devices is of extreme importance. These devices are often integrated using Radio Frequency Identification (RFID). The RFID automatically recognizes the object details by reading the physical objects. The system reader, which is equipped with a backend server, uses radio frequencies to communicate with the objects with RFID tags. It makes the practical usage of RFID very vast. Security is the most vital aspect of communication for authentication and securing private data. RFID-based security is beneficial in multiple ways, as RFID does not require a light source and line of sight scenario for communication. Hence RFID can be deployed to sensor monitoring, access control, real-time inventory, and security-aware management systems. However, due to limited computational and memory resources on an RFID tag, limited cryptographic operations can be applied. Therefore, an eavesdropper can forge and access the user’s private data. David et al. in [ 21 ] proposed a hash-based RFID authentication mechanism for Context-Aware Sensor Management System (CASMS) to provide security to prevent attacks such as replay, man-in-the-middle, and desynchronization. Hash-based RFID authentication is the five-phase mechanism, namely pre-phase registration, reader pro-tag request and response, tag mutual session key authentication, back end server key authentication, and session key updating. Performance analysis is made based on the Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) and End-to-End Delay (E2E). Results depict that the proposed model significantly improves PDR and E2E.

Water is the soul of life and essential to the well-being of every person, economy, and the ecosystem on Earth. More than 70% of the Earth is surface is covered by oceans, and they are critical to maintaining the weather and temperature around the globe and providing a means of transportation. However, more than 90% of oceans are unexplored even to the extent that they are still unseen by humans. IoT paved the way to explore and collect the data by connecting different types of networks underwater. Such networks are known as the Internet of Underwater Technology (IoUT) is an emerging technology to support Underwater Sensors Networks (UWSNs) for exploration of undiscovered marine resources. UWSN using communication cables and sensors and maintenance cost is very high. Therefore, underwater wireless communication is proposed. However, UWSN wireless communication is challenging due to environment and propagation losses, which include high noise, Doppler spreading, path loss, multi-path signal propagation, and high power consumption. To overcome these issues, Faheem et al. in [ 22 ] proposed cross layered QoS Aware routing Protocol (QoSRP). The proposed scheme is composed of underwater channel detection, channel assignment, and packets forwarding. The QoSRP selects detects the high probability vacant channel and assigns the high data rate channels to an acoustic sensor node. The QoSRP also balances the traffic, avoids congestion, and data path loops to increase PDR and throughput of the system with minimum delay along the path.

Ultra Wide band (UWB) features include higher bandwidth, and it is one of the viable technologies for IoMT applications. The integration of UWB in health critical IoT applications can provide an effective and reliable solution for the monitoring of patients. Ataxia patients suffer from abnormal movement, and that severely affects walking activities. The walking activities can be classified as a normal walk, difficulty walking in a straight line, walking with heavy steps, and forward bending walking. All of these walking patterns except normal walking shows abnormality. Zilani et al. [ 23 ] proposed a scheme to cater to this problem. They set up the testbed in an indoor environment. They collected sample walk patterns and classified it using Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms, namely SVM-based Sigmoid Kernel Function (SKF) and Radial Basis Function (RBF). Results show that RBF performs better than SKF. The drawback of the proposed scheme is that it is only tested for a single person. Hence, it should be extended to monitor multiple persons.

Security, privacy, and trust remain challenges in IoMT because of the openness and heterogeneity of IoMT. Access control is used to protect the confidentiality and integrity of constrained resources in IoMT services. It provides a solution to avoid any unauthorized access for multimedia applications in IoT services. However, due to increasing the number of users and multimedia services offered by the IoT platform, the access control system is becoming more and more multifaceted. Besides, access control policy evaluation reduces the performance of IoMT applications. Therefore, Meiping Liu et al. [ 24 ] proposed an Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) policy retrieval method to improve the performance of access control policy evaluation in multimedia networks. To rebuild the policy decision tree, an attribute value level, and the depth index is introduced, thus, improve policy retrieval efficiency. Policy analysis is performed with a different number of rules and the increasing complexity of the policy. Results indicate that the proposed method is more efficient and scalable than the existing access control schemes.

Increasing demand for data-intensive applications is growing users’ data requirements exponentially. However, spectrum scarcity is the biggest hurdle in meeting users QoS. One of the viable solutions is to reuse and share the spectrum among the users to fulfill users demands without compromising the user’s experience. Even though unlicensed spectrums are available for free, they are already overcrowded. Different network technologies such as 5G and Wi-Fi use different spectrum access mechanisms, and sharing the spectrum among them is a trivial task. To allow fair coexistence between 5G and Wi-Fi networks operating in the same spectrum, LBT is introduced to work in parallel with the CSMA for channel access. RL techniques can be adapted to make a spectrum access mechanism to learn network conditions itself and adapt to the network changes accordingly. Consequently, the network becomes sustainable and self-adaptive. Neto et al. in [ 25 ] proposed Q-Learning to LTE-U to adjust the duty cycle parameters to reduce coexistence interference and improve the system data rate. A saturated network scenario is considered to evaluate the proposed scheme in the ns-3 simulator. The proposed algorithm performs well in a multi-cell coexistence network scenario. Hence, it improves overall system performance by achieving a higher data rate for users and systems compared to the existing conventional mechanism.

4. Conclusions

Six papers in this SI presented state-of-the-art research trend in the area of IoMT opportunities, challenges, and solutions. The papers presented an interesting discussion and novel ideas for the readers. The guest editors would like to show appreciation to the authors and thank all the anonymous reviewers for providing constructive feedback to improve the overall quality of all the accepted papers. We would also like to thank sensors Editor in Chief Prof. Dr. Vittorio M.N. Passaro, Associate Editor in Chief of the IoT section Prof. Dr. Raffaele Bruno, and managing editor Missy Wu for the invaluable help and productive advice in finalizing this SI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Brain Korea 21 Plus Program (No. 22A20130012814) funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), in part by the MSIT(Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ITRC(Information Technology Research Center) support program(IITP-2019-2016-0-00313) supervised by the IITP(Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation), and in part by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1D1A1A09082266).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.B.Z. and M.K.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.B.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing, Y.B.Z., M.K.A., S.W.K.; Supervision, S.W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Open access

- Published: 15 September 2020

Smart multimedia learning of ICT: role and impact on language learners’ writing fluency— YouTube online English learning resources as an example

- Azzam Alobaid ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2990-6987 1

Smart Learning Environments volume 7 , Article number: 24 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

22 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

This work seeks to determine if and how much the smart learning environment of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) tools like YouTube can help improve learners’ fluency of language use and expression in their daily written communication. This research highlights and takes advantage of the potential role and features of multimedia brought to the language learner by the ICT tools, taking YouTube online English learning resources as an example of this smart learning environment. This work hypothesizes that learners who engage with, expose themselves more to and leverage such online language materials could develop their fluency of daily language use and expression in writing over time. The findings of this research show that there is a statistically significant difference in some but not all aspects of the learners’ writing fluency; basically, the accuracy and organization of ideas as qualitative dimensions of fluency improved after the actual exposure to YouTube over five months as long as factors like engagement, enhancement and intelligibility are provided by its multi-mediated input. However, other aspects of fluency in writing could develop slightly but with no statistically significant difference. Also, compared to other sources of language learning in the learners’ environment, multimedia educational tools developed by ICT like the widely known platform YouTube can be more effective and thus strongly recommended equally for language learners and teachers where optimization of writing fluency is the target of learning. This paper is a work-in-progress that investigates the role and impact of smart learning environment of ICT multi-media on English language learners’ fluency and accuracy of use and expression in speaking and writing.

Introduction

ICT in the field of education is the integration of various technologies of information and communication so as to leverage its capacity for the optimisation, enhancement and creating of a better learning environment and smoother learning process. A wealth of research in the literature showed the significant and positive impact on students’ achievements through the increase in the use and exposure to ICT in education. Aoki ( 2010 ) in a report findings by the National Institute of Multimedia Education in Japan showed that “the students with continuous exposure to ICT technology through education demonstrated better ‘knowledge’, presentation skills, innovative capabilities, and were ready to take more efforts into learning as compared to their counterparts”. Moreover, ICT has impacted multimedia learning of language with its attractive and interactive strengths to provide easy to reach multimedia language materials (MMLM); such MMLM are packaged with graphical, textual, animated, audio and video materials delivered to the end-user through wide variety of electronic devices, primarily via computers, smart boards and phones. ICT, whose implementation is intended to create smart learning environment— YouTube online English learning resources as an example of this smart learning environment, is synonymous with smart learning environments in this work. However, it would be useful to define smart learning environments although there is no completely agreed upon definition for them, yet they are often understood as an improvement of physical environments with novel technologies to provide a smart, interactive classroom with increased interactivity, personalized learning, efficient classroom management, and better student monitoring (Yesner, 2012 , as cited in Libbrecht, Müller, & Rebholz, 2015 ). Smart learning environments are related to ambient technologies, describing learning environments, which exploit new technologies and approaches, such as ubiquitous and mobile learning, to support people in their daily lives in a proactive yet unobtrusive way (Buchem and Pérez-Sanagustín, 2013 ; Mikulecký 2012 , as cited in Libbrecht et al., 2015 ). The rational and significance for integrating ICT tools for creating smart learning environments in foreign/second language education lies in the fact that ICT multi-faceted features in the domain of language learning are many, especially those that can be beneficial for language learners like personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness, richness of authentic and engaging input.

Personalization is one major facilitative characteristic of modern ICT in education also known as customization or individuality of choice of materials where a service or a product can be tailored to cater for specific individuals’ or group’s needs. Put differently, each student can now learn at his/her own pace and space and instructors can accommodate and cater for the individual needs and interests of learners. This feature can be hypothesized to enhance multi-media learning through the adjustment of a given language input that learners may be able to get more and clearer input and thus greater or more fluent output. More on personalization and the integrity of knowledge, Vaughan ( 1993 ) suggested that when the user or viewer of the project can adapt and control what and when these elements are delivered, it is interactive multimedia; more usefully, this interactive multimedia has become hypermedia providing learners with a structure of linked elements where now materials can be widely navigated, interacted with and exchanged. In this research ICT multimedia is employed as both interactive and hypermedia catalyst where a “structure of linked elements of knowledge” is bringing an array of MMLM to learners through their devices. Also, personalization includes the use of YouTube closed captions and its adjustable settings related to font size, color, opacity and the playback speed for learning and improving writing.

Networking and interactivity are the use of social networks in both private and academic life, for example YouTube. (Mukhaini, Al-Qayoudhi, & Al-Badi, 2014 ) “These are tools used to enable users for social interaction. The use of social networks (SNs) complements and enhances teaching in traditional classrooms. For instance, YouTube, Facebook, wikis, and blogs provide a huge amount of material on a wide range of subjects. Students can, therefore, turn to any of these tools for further explanations or clarifications”. This feature can be hypothesized to enhance the reception and production of input giving leaners a chance for language practice and active exposure.

Inclusiveness means that a wider diversity of people can make (easy) use of it. Rice ( 2011 ) Inherent in inclusive education is the notion that reform and improvements should not only focus on children with disabilities but on “whole school improvement in order to remove barriers that prevent learning for all students” (GeSCI, 2007 , as cited in Rice, 2011 ). Inclusive schools can “accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, emotional, social, linguistic or other conditions” (Article 3, Salamanca Framework for Action). However, inclusive education is not a synonym for special needs education or integration techniques but an “an on-going process in an ever-evolving education system, focusing on those currently excluded from accessing education, as well as those who are in school but not learning” (UNESCO 2008 ). According to Rice ( 2011 ) “There is a wide variety of accessible ICTs currently available which can help overcome reduced functional capacity and enable communication, cognition and access to computers.” This feature can mean welcoming and accommodating more learners through the potential outreaching and connecting with everyone.

Rich provider for authentic language input, context and culture as in the easy-to-get authentic input that is quantity- and quality-wise useful. Grzeszczyk ( 2016 ) noted that “CALL was expanding and introducing tools helped teachers to supply learners with more up-to-date, authentic, target-specific, and learner-oriented materials”. According to Pun ( 2013 ) “using multimedia technology offers the students with more information than textbooks and helps them to be familiar with cultural backgrounds and real-life language materials, which can attract the students to learning”. More on culture, Pun ( 2013 ) observed that “the learners, through the use of multimedia technology, will not only improve their listening ability, but also learn the culture of the target language; this brings about an information sharing opportunity among students and makes them actively participate in the class activities that help the students to learn the language more quickly and effectively”. In terms of context, “the utilization of multimedia technology can create a context for the exchange of information among students and between teachers and students, emphasizing student engagement in authentic, meaningful interaction” (Warschauer & Meskill, 2000 , as cited in Pun, 2013 ) as in “using multimedia in English teaching/ learning can be an appropriate method to help students to get a sense of the sociocultural context in which the language is used” (Kramsch, 1999 , as cited in Yang, 2008 ), “as well as raising students’ language awareness under the framework of World Englishes” (Kunschak, 2004 , McKay, 2002 , as cited in Yang, 2008 ).

ICT can provide a whole raft of engaging multi-media materials as learners can be all the more free to choose and adjust their learning materials. A wealth of research has shown that “using social media as an educational tool can lead to increased student engagement motivating them to learn more (about) languages by way of audio, visual and animation support” Tarantino, McDonough, and Hua ( 2013 ). (See also Annetta, Minogue, Holmes, & Cheng, 2009 ; Chen, Lambert, & Guidry, 2010 ; Junco 2012 ; Patera, Draper, & Naef, 2008 ). (Izquierdo, Simard, & Garza, 2015 ) confirmed previously established research in education that ICT makes it easier for learners to access language materials, stressing an existing correlation between second language learning and the use of multi-media materials in a computer-enhanced language learning milieu showing an impact on learning behaviour with increased motivation. This said, ICT multi-media could be enriching for the learners’ language experience as in helping learners write fluently (quantity- as well as quality-wise). This research underscores that the language used in this input can be taken as a model for the language learner. Thus, in addition to other previous and coming input possibly acquired by the learner, the new input could be in effect increasingly adding up to the learner’s knowledge of language and developing their output to be more fluent.

With the above-mentioned plausible advantages of ICT in mind and that modern ICT technology like YouTube has impacted multimedia in education as far as it can be seen through a wide range of educational channels, it’s worth questioning this impact from a desirable angle by language learners and instructors, which is the fluency of writing performance.

A far-reaching definition of fluency in writing that would suit the purpose of this study is based on a number of perspectives of fluency in the literature combined in a study by (Atasoy & Temizkan, 2016 ) “the act of writing the maximum number of language units in a short period of time while also paying attention to accuracy, the coherent and consistent organization of ideas within the text, and the usage of words and sentences in a complex manner.”

The focal point of this study is that, can learners of English make a progress in a better (in the sense of quality and quantity) communicative writing as long as the seemingly learning environment by way of multi-media technology of ICT cannot be more helpful as it is as facilitative as it sounds (both in terms of technical capabilities and language materials and content information possibilities) for learners of English in writing?

This study attempts to reach an understanding of what and how much, if any, can be developed of learners’ written performance in terms of fluency given that they are to varying degrees exposed to and engaging with ICT multi-media during their learning process.

RQ. Can exposure to and engagement with ICT educational multimedia like YouTube have some effect on the development of learners’ fluency of language use and expression in writing?

Literature review

This research examines the multimedia role of ICT in language learning as input provider of language materials, assuming that ICT YouTube technology as input provider and enhancer, and its impact on learners’ development of fluency in writing. Therefore, it would be necessary to look into the relevant input theories of language learning and those of multimedia trying to connect the dots between them; the theories adopted in this research are the language learning theories of Comprehensible Input, Input and Interaction, Comprehensible Output, Input Enhancement, Noticing the Gap and the Multimedia Learning Theory.

The first and foremost stage of language acquisition assumed by Krashen and his proponents is the introduction of “comprehensible input” which is defined as “a language input which can be comprehended by listeners albeit not understanding all the words and structures in it. This input is described as one level above that of the learners if it can only just be understood” (British Council, 2020a , b ). ‘Comprehensible input’ is the crucial and necessary ingredient for the acquisition of language supplied in a low anxiety situation, containing messages that students really want to hear. However essential to the language development, “comprehensible input is held to be a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for SLA” (Krashen, 1985 ; Long, 1983 ). Long’s Input and Interaction Hypothesis (Long, 1985 ) argues for the significance of both input comprehension and modifications in order to facilitate language acquisition, i.e., through negotiated interaction of discourse structure and modified input. Following Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis (1992, 1994), “Multi-media Instruction (MI) research has provided learners with rich exposure to the L2 in meaning-based tasks built upon different media features” (Plass & Jones, 2005 , as cited in Izquierdo et al., 2015 ).

According to Swain ( 2005 ), the output hypothesis “asserts that the act of producing language (speaking or writing) constitutes under certain circumstances, part of the process of second language learning” (Swain, 2005 , p. 471, as cited in Pannell, Partsch, & Fullver, 2017 ) and “that even without implicit or explicit feedback provided from an interlocuter about the learners’ output, learners may still, on occasion, notice a gap in their own knowledge when they encounter a problem in trying to produce the L2” (Swain & Lapkin, 1995 ).

Input enhancement, Smith ( 1991 ) examines the concept of “‘consciousness raising’ in second language learning, i.e., how certain features of language input become salient to learners suggesting different ways for making input salient and different ways in which such salience may affect the learner’s knowledge and performance in language learning”. Relating to the concept of consciousness raising is what is now termed in neurolinguistics as metacognitive awareness. Just as it is essential to effective learning, metacognition is an important part of successful technology adoption (Gurbin, 2015 ).

The noticing hypothesis (Schmidt, 1990 , 2001 , as cited in Schmidt, 2010 ) argues that “input does not become intake for language learning unless it is noticed, that is, consciously registered”.

Mayer ( 2009 ) defines a “multimedia environment as one in which material is presented in more than one format – such as in words and pictures” where according to his “multimedia principle”, Mayer ( 2002 ) premises that “people can learn more deeply when they receive an explanation in words and pictures rather than words alone”. In the same vein, “according to the sensory modalities view, in his perspective, multimedia means that two or more sensory systems in the learner are involved. It focuses on the sensory receptors the learner uses to perceive the incoming material – such as the eyes and the ears”. In this respect, the signalling principle of multimedia states that students engage in “deeper learning when key steps in the narration are signalled rather than non-signalled” (Mayer, 2005 ). Signals give cues to the learners about what words and pictures to notice and enables their organisation. This means that linguistic elements need to be linked to some visual stimuli so as to assist learners’ storage of the new linguistics elements in their long-term memory (Matus, 2018 ).

In relation to these multimedia theories, a number of multimedia technology studies were conducted in the field of language learning focusing on different language aspects and different multimedia applications and their potential impacts and facilitative features. For example, the multi-media effect of captions or subtitles inclusion whilst watching films dealt with issues like the listening comprehension improvement and vocabulary acquisition. (Yoshino, Kano, & Akahori, 2000 ) examined the listening comprehension of Japanese EFL students and found that foreign subtitles inclusion can be “helpful but native-language subtitles provide no benefit or less benefit” in this regard. (Mitterer & McQueen, 2009 ) supported the previous studies that second language learners can boost their listening ability when watching films with “foreign-language subtitles as this can improve repetition of both previously heard and new words, the latter demonstrating lexically-guided retuning of perception. While native-language subtitles can help only recognition of previously heard words but harm recognition of new words”. In terms of vocabulary acquisition, in their study (Winke, Gass, & Sydorenko, 2010 ) mentioned “a number of observations about the use of captions, confirming previous research that captions are beneficial because they result in greater depth of processing by focusing attention, reinforce the acquisition of vocabulary through multiple modalities, and allow learners to determine meaning through the unpacking of language chunks”. Xiao ( 2007 ) conducted a study on the effect of the use or interaction with native speakers through video conferencing as a multimedia for oral practice of speaking in English on learners’ oral improvement of fluency, accuracy and complexity. He found “a significant improvement in fluency, a slightly significant improvement in accuracy, but no improvement in complexity for the L2 learners” as a result of this kind of exposure to English to interact with native speakers.

The potential of using ICT multimedia with its features of personalization, networking, inclusiveness, richness of engaging input, context and culture like YouTube for language learning and its impact on other aspects like the fluency of use and expression of writing, however, has not been sufficiently investigated. This research is mainly interested in the role of the foreign language subtitled multimedia (like YouTube) effect on learner’ improvement of writing fluency. In this research, “multimedia” means the availability of both speech and text as implied by the sensory modalities view of multimedia contrasted with mono-media as having either of them, i.e., speech/ text, Mayer ( 2009 ).

To connect the dots, this work proposes the use of ICT as a multimedia source of comprehensible input which is hypothesized to lend itself to help learners producing comprehensible output, i.e., or more fluent use and expression of language in writing; this is hypothesized to be achieved first, as ‘learners consciously by themselves or made conscious by the teacher to notice their gap(s), (especially in terms of gaps related to accuracy of language use), in the provided input—what becomes intake for learning’ as implied in the Noticing the Gap Hypothesis; second, through ‘negotiated interaction (with the teacher or other learners using some given multi-media material in question) and modified input’ as implied by Long’s Input and Interaction Hypothesis (Long, 1985 ). One effective way to let input noticing and negotiating happen is through the use of the ICT personalization and networking and interactivity features, respectively; “the process by which language input becomes salient to learners” as indicated by the Input Enhancement Hypothesis. These workings entailed from these language learning theories collectively can arguably be practically put into action within the Sensory Modalities View of Multimedia framework when the sensory receptors of the eyes and the ears of the learner are used to perceive the incoming material of text and speech respectively in the ICT leaning environment.

Our multimedia approach takes to the full a great advantage of the multiple personalization features provided by the ICT technology available in this research example, i.e., YouTube, to make a given input as much salient or comprehensible and reproduceable as needed; such features are mainly the optional text aligned with the speech, with care given to correct spelling, placement of punctuation marks and capitalization; font size, colour and opacity; and the playback speed. Such features are considered as highly significant and facilitative for both comprehending the meaning and noticing the form(s) of the language presented in a given episode on such YouTube channels. Familiarizing learners with or controlling these features in proportion to the learners’ needs can perhaps better benefit learners navigate their learning of the language in hand and make it more accurate and fluent; that is to say, understand more and faster meaning and notice more and clearer forms, so much so that their knowledge of the language forms would not only be increasingly informed and enriched but also the number of language errors be it grammatical (omission, addition, mis-ordering), lexical (misinformation, misspelling, informality) or mechanical (punctuation, capitalization) would be reduced (for the categorization of error types and analysis used in this research this work refers to the taxonomy by (Dulay, H. et al., 1982 , as cited in Ellis & Barkhuizen, 2005 ) and the work of Ferdouse ( 2013 ). From the Input and Interaction view such learning is supposed to happen due to the learners being exposed to and engaged with this multi-mediated authentic input which can be set as a model to acquire or learn language from.

Having the plausible advantages of ICT in mind supported by research in the literature, this work attempts to first activate and encourage the use of YouTube as an example of ICT in class as well as out of class and then check on its likely impact to find answers to questions like what and how much linguistic input, if any, learners get through ICT as far as fluency in communicative writing in English is concerned. Our approach explores, in terms of exposure time range and engagement degree, the various potential language learning resources in the learning environment of this sample group, including the ICT YouTube as one of these sources; then, we correlate these sources, which are deemed as explanatory variables in this study, with the learners’ actual performance of communicative writing fluency. This work suggests the BBC Six-Minute English YouTube Channel as a case study.

This study selected and relied on exposure time range and engagement rate as factors or indicators of learning due to their huge popularity in literature as significantly influential drivers of learning foreign/ second languages (For the significance of exposure time see Benson, 2001 ; Ellis, 2002 ; Krashen, Long, & Scarcella, 1979 ; Peregoy & Boyle, 2005 . For the significance of engagement see Astin, 1984 , 1993 ; Benek-Rivera & Matthews, 2004 ; Bertin, Grave, & Narcy-Combes, 2010 ; Sarason & Banbury, 2004 ). Early studies defined student engagement primarily by observable behaviors such as participation and time on task (Brophy, 1983 ; Natriello, 1984 ). Researchers have also incorporated emotional or affective aspects into their conceptualization of engagement (Connell, 1990 ; Finn, 1989 ). It can be understood from these definitions that engagement include feelings of belonging, enjoyment, and attachment, which is how this study defined the engagement for its analysis. Time range of exposure was defined for this study as “the contact that the learner has with the language that they are trying to learn, either generally or with specific language points”. (British Council, 2020a , 2020b ).

Research methods

This research is a longitudinal study investigated patterns within time-series data. The performance of a single group of participants was measured both before and after the experimental treatment. It was conducted over a period of five months at the Iraqi school in New Delhi. It’s a co-education schooling system where 14 learners, who showed interest in this project, were randomly selected. The range of population sample age was 12–15 years (five boys and nine girls, i.e., 35% and 65% respectively). The proficiency level of the language learners was estimated to be pre-intermediate and above as their average formal semester evaluation scores of English subject showed. The medium of instruction at school is Arabic except for English classes it’s English-based most of the time. English for the participants is second as it has to be used outside the classroom where the bigger context is Delhi where English is ‘for most of the population has only ever been a second language’ (Robinson, 2019 ). At the beginning, participants were explained the general framework of the study and given freedom to entirely choose for themselves the content out of the suggested YouTube channel for discussion and writing about for every class. Participants were met three days a week and YouTube was at the heart of the meeting to interact with its content in a watch-take notes-discuss modality using the necessary technological accessories for that matter like an overhead projector, sound amplifier and good internet connectivity for browsing and streaming a given program, in this case the BBC Six-Minute English YouTube channel. It is the program suggested by the researcher as it’s only a six-minute, free of charge weekly show presented in English using the British English. It’s designed and broadcasted by the BBC for intermediate level classes. The rationale behind introducing this channel on YouTube as a tool in ELT classes is that it matches the learners’ overall proficiency level, and these videos use General English—the day-to-day English used exclusively in people’s lives presented in a casual and conversational style that helps learners learn and practice authentic useful English language for everyday situations as in saying, writing or doing something using English.

Pedagogical scenario and task design

At the end of every English class learners were suggested three videos by the instructor (the titles were supposed to be interesting and new to them), and they had to vote (each according to the topic s/he liked) for one of them, and the majority would win for that matter. This new video of BBC six-minute English would be the subject matter for next class. At home, learners start watching to explore and understand the theme on their own. After watching it as many times as needed, learners were asked to write a summary and add their comments about the topic discussed in a given video of this channel. Also, they were encouraged to note down any inquires or doubts about the topic and bring that to class for open discussion. Learners were strongly advised and encouraged to refer to and use the closed captions and its adjustable settings like font size and colour in a given video to check for themselves on the right meaning of the topic/ some sentence or to check (problematic/ unfamiliar) grammatical forms/ vocabulary, word choice, spelling, punctuations, abbreviations, or capitalization. Learners were to do this every time they were given a writing task.

At the start of the writing lesson, the same video with the subtitle turned on was watched by the whole class once again. Then, learners were asked to read out their written summaries and discuss with the class the general idea of the introduced topic. Also, the teacher would basically use the subtitle and its adjustable related settings of font size and colour for their signalling effect (Mayer, 2009 ), which will be projected on the board, to refer to and discuss a particular language point/ inquiry. These language points/ inquiries were mainly those raised directly by the learners themselves, or indirectly when errors were noticed in their writing or even the teacher can pinpoint some language points whenever found noteworthy, relevant and enriching for the learners’ writing. Moreover, learners were encouraged to refer back to the subtitle as a reference point at any time they need to check for themselves and with each other on the right meaning of the topic/ some sentence and check the accuracy of word choice, morphological/ grammatical structures, abbreviations, spelling, punctuations or capitalization.

Data collection

In order to elicit the data from the current population sample, this research adopts a strategy of triangulation through two methods.

Two IELTS-based communicative writing tasks were conducted for the baseline and other two different IELTS writing tasks were conducted as an end line. The tests were given to learners before and after the introduction and integration of the suggested YouTube Channel, BBC Six-Minute English YouTube Channel so as to record their actual writing fluency progress, taking the IELTS standards for the test administration into consideration. Learners are, thus, examined on two communicative tasks each time rather than a single one and the total of two is given as a single line of reference each time for evaluation. This is considered to be more representative of the learners overall communicative competence. The findings of these tests provided the data required to help answering the main research question of this study.

Nonetheless, there is a wide range of likely factors and resources (also known as confounding variables) of English language learning that may co-exist in the learning environment of this research population and hence may impact to varying degrees the improvement of this population’s targeted variable of fluency of writing. Also, this work can only focus on one of these many resources and is mainly interested in the role and impact of ICT multi-media like YouTube as a language learning tool. Therefore, to be able to overcome this challenge and make a valid judgment about other variables which might be playing a role along with the possible YouTube role in the possible development of learners’ writing fluency for this sample group, a quantitative and qualitative online questionnaire was developed according to the specific aims and context of this study, measuring specific potential resources of English language learning in terms of the learners’ daily time range of active exposure to and learning engagement rate with them. The percentages drawn from the population sample responses through the online questionnaire were employed to identify several factors/ independent variables in terms of exposure time and engagement rates with the potential learning sources of English language learning; that would be correlated with the actual linguistic progress learners may make. These percentages are namely the likely potential media or contexts of language learning favoured by learners (e.g. reading and/or listening), preferred mode of exposure (online, offline), modality (text and/or speech), the language skill(s) involved, the type of input material exposed to (as in songs, films, video games, (audio) books). This self-report questionnaire was administered at the end of the five months. The learners’ responses from the survey items were used in the quantitative and qualitative analyses to answer the main research question mentioned above. This questionnaire which was a combination of closed-ended and Likert questions (35 items in total) covered three main areas. First, the participants’ English writing learning experience of both the online and offline English learning resource(s) including YouTube with regards to their engagement rate with and daily time range of exposure to each of these resources (Qs. 4–29 see Appendix A for the questionnaire items related to this area). for the questionnaire items related to this area). Second, the participants’ English writing learning experience with YouTube in particular as an ICT tool for creating the intended smart learning environment with respect to its features of personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness and as a resource for rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving your English writing (Qs. 30–33 see Table 8 for the questionnaire items related to this area). Third, learners’ personal and contextual perspectives on the affordances of YouTube videos and how they thought YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting according to their experience (Qs. 34 & 35 see Tables 9 & 10 for the questionnaire items related to this area).

Data analysis

The data analysis included both quantitative and qualitative methods. The quantitative methods used in this study were Matched-pairs t-test, Pearson’s correlation, Simple linear regression and frequency distributions. A matched-pairs t-test was used as it is appropriate for a repeated measure design where the same subjects are evaluated under two different conditions such as the case in this study. Pearson’s Correlation was used to explore the relationship between the learners’ writing fluency progress (as the dependent variables for correlation; the data for these variables were elicited from the T. test findings after the integration of YouTube) and the participants’ English writing learning day-to-day experience with some potential online/ offline mono-medium and multimedia learning materials/ environments, including YouTube media with regards to the participants’ engagement rate with and daily time range of exposure to each of these resources. (as the independent variables for correlation; the data for these variables were elicited from the respective questionnaire items Qs. 4–29). Simple linear Regression, focusing primarily on the Likert items which showed a linear relationship, was conducted to identify the variation of the engagement rate with and time range of exposure to YouTube as predictor variables on the writing fluency metrics. Frequency Distributions were used to determine the percentages of learners’ active use of ICT with regards to its features of personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness and as a resource for rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving English writing (the data for frequency distribution were elicited from the questionnaire items Qs. 30–33).

In terms of the qualitative method, a simple content analysis consisting of two closed-ended questions was performed. Learners were asked to choose how they thought YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting according to their experience. The answers list (for these two questions) learners were to choose from are widely mentioned in the literature of learning writing (except for those relating to closed captions which were investigated in this study) and in line with the research questions of this study (the data for content analysis were elicited from the questionnaire items Qs. 34–35).

Coding the data

As for the test findings, all the participants’ responses ( n. 14) were analysed in terms of writing accuracy objectively using the taxonomy of errors by Dulay, H. et al. ( 1982 ) cited in Ellis and Barkhuizen ( 2005 ) and then coded based on the work by Oshima and Hogue ( 1997 ) and developed in the work of Ferdouse ( 2013 ). Each writing task was rated twice and the inter-rater reliability of the ratings for the 56 writing tasks used in this study was 0.87. Inter-rater reliability rates between 0.75 and 0.9 are good, Koo and Li ( 2016 ). Also, this research used seven metrics or dimensions of various foci of writing fluency of quantitative and qualitative nature widely accepted in the literature as indicators of fluency development (see Ellis, R., 1990 ; Lu, X., 2010 , 2011 ; Lu, X., & Ai, H, 2015 ; Wolfe-Quintero, K., et al., 1998 ; Vaezi & Kafshgar, 2012 ; Fellner and Apple, 2009 ; Van Gelderen, A., & Oostdam, R., 2005 ); these were used as the dependent variables of this study. These dependent variables are of quantity and quality nature. This study used only one quantitative dimension of writing fluency, namely the writing rate which is measured by the number of syllables written per minute in a text. The qualitative dimensions of writing fluency were the number of error-free T. units per text as a sub-dimension of accuracy dimension; lexical diversity (measured by different number of words/total number of words× 100) and lexical density (measured by the number of content words/total number of words× 100) as sub-dimensions of lexical complexity dimension; mean length of T. unit and number of clauses per T.unit as sub-dimensions of syntactic complexity dimension, and organization of ideas which is measured by the overall coherence & cohesion of ideas and task achievement. It should be mentioned that the author used online automatic softwares to conduct the required writing fluency analyses for this study (see Web-based L2 Syntactic Complexity Analyzer by Ai, H., ( n.d. ), Ai, H., & Lu, X. 2013 ; Analyze My Writing ( n.d. ); TAASSC, see Kyle, K. 2016 ; Text Inspector, ( n.d. )). These softwares are cited in the reference list with the respective URLs.

As for the questionnaire findings, all the participants’ responses ( n. 14) were downloaded to a Microsoft Excel sheet and subsequently exported to SPSS version 21.0. With respect to the engagement rate, it was measured on a five-point Likert scale where 1-point was defined as very low engagement and 5-points as very high engagement. As for the exposure time range, it was defined by the number of hours spent in a day using each of these resources for learning English and measured on a five-point Likert scale. Time range of exposure was coded as 0, one hour as 1, two hours as 2, three hours as 3 and more than 3 h as 4.

Quantitative results

Matched-pairs t-test.

In order to be able to check and account for the difference with regards to the baseline compared to the end line datasets of learners’ writing performance objectively, the statistical T. test was used. The means differences between these datasets showed to various degrees some improvement across all the dependent variables set in this work except for the lexical density variable as shown by the means differences in the fluency gain level of writing post the integration of YouTube as an ICT tool for learning and improving writing (Table 1 ) (Details on each variable will be discussed below). Most statistical analyses would use an alpha of 0.05 as the cut-off for the level of significance. If it is found that the p value < 0.05, then the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the means before and after the study can be rejected. The following null hypothesis (H o ) set in this work and its alternative hypothesis (H a ) are as follows:

H o = exposure to and engagement with ICT educational multimedia like YouTube has no effect on the development of learners’ fluency of language use and expression in writing.

H a = exposure to and engagement with ICT educational multimedia like YouTube has an effect on the development of learners’ fluency of language use and expression in writing.

The following are the T. test results (see Table 1 ) for the quantitative and qualitative writing fluency dimensions.

Quantitative dimension

Writing rate.

The results from the pre-test ( M = 5.72, SD = 2.09) and post-test ( M = 6.19, SD = 1.66) writing tasks showed a slight improvement in the learners’ writing fluency in terms of writing rate after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 1.353, p = .199.

Qualitative dimension

Number of error-free t. units per text.

The results from the pre-test (M = 1.57, SD = 2.24) and post-test (M = 7.21, SD = 6.14) writing tasks showed good improvement in writing fluency in terms of the number of error-free T.units per text after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 4.623, p < .001.

Lexical diversity subdimension of Lexical complexity

The results from the pre-test ( M = 52.54, SD = 19.96) and post-test ( M = 54.86, SD = 15.11) writing tasks showed a slight improvement in writing fluency in terms of lexical diversity after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 0.526, p = .608.

Lexical density subdimension of Lexical complexity

The results from the pre-test ( M = 47.25, SD = 4.59) and post-test ( M = 44.41, SD = 2.75) writing tasks showed no improvement in writing fluency in terms of lexical density after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 2.816, p = .015.

Mean length of T. unit subdimension of Syntactic complexity

The results from the pre-test ( M = 9.97, SD = 1.95) and post-test ( M = 10.48, SD = 2.22) writing tasks showed a slight improvement in writing fluency in terms of syntactic complexity after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 1.063, p = .307.

Number of clauses per T. unit subdimension of Syntactic complexity

The results from the pre-test ( M = 1.26, SD = 0.32) and post-test ( M = 1.34, SD = 0.28) writing tasks showed a slight improvement in writing fluency in terms of syntactic complexity after the exposure to the suggested ICT tool, t (14) = 0.960, p = .354.

Organization of ideas

The results from the pre-test ( M = 4.07, SD = 1.07) and post-test ( M = 6.36, SD = 1.28) writing tasks showed a slight improvement in writing fluency in terms of the number of error-free T.units per text, t (14) = 8.000, p < .001.

To summarize the T. test results, all dependent variables (except for the lexical density variable) set as indicators of fluency of writing in this study have to various degrees shown some improvement after five months of focused exposure to YouTube as indicated by their means differences in the T. test results. However, only two of them were statistically significant, namely, the number of error-free T. units per text and organization of ideas.

Correlation coefficient results (the critical value approach)

Pearson’s Correlation was used to explore the strength and the direction of the relationship between the learners’ writing fluency which was based on the T. test findings after the integration of YouTube and the participants’ English writing learning day-to-day experience with some potential online/ offline mono-medium and multimedia learning materials, including YouTube media with regards to the participants’ engagement rate with and daily time range of exposure to each of these resources. With regards to the strength of association between variables, the critical value for Pearson’s |r| was set at the value of 0.05 = 0.532 (as a level of significance for a two-tailed test given by Pearson table of critical values) with a degree of freedom df = N-2, df = 14–2 = 12. So, any correlation coefficient value falling below the 0.532 was considered insignificant and any correlation coefficient value above the 0.532 was seen as significant (only the significant correlation coefficient values were highlighted in the tables below), where the higher the r value or closer to | + 1/− 1| the stronger the correlation is between any two variables.

As for the direction (i.e., negative = −ve / positive = +ve) of the relationship between variables, all seven dependent variables in each of the correlation tables below should be positively correlated with the independent variables as these particular dependent variables were dealing with factors where higher rates or values reflect higher or better outcome on the part of the learners so that the higher the value of each correlation coefficient means the better the performance or the more fluent the writing is. No negative correlation between any of these variables should be predicted for this work.

The critical value for Pearson’s |r| was set at the level of 0.05 = 0.532.

The results of the correlation analysis were broadly divided into two main categories — online Vs. offline learning.

Online learning

The correlation coefficient results of the learners’ engagement rate with the respective online mono-medium and multimedia learning sources showed various values of which the majority were insignificant in terms of correlation, especially in the mono-medium learning environment. Nevertheless, the significant correlation values in terms of both strength and direction were those in the multimedia environment of YouTube, video games and audio books. (see Table 2 ). These significant correlations were as follows:

One strong +ve correlation (r = .763) for the multimedia provided by video games;

One strong +ve correlation (r = .606) for the multimedia provided by films;

One moderate +ve correlation (r = .575) for the multimedia provided by audio books; and

One moderate +ve correlation (r = .598), two strong +ve correlations (r = .606, .732) and two very strong +ve correlations (r = .867, .844) for the multimedia provided by the YouTube.

These results showed that the correlations of learners’ engagement are significant on the multimedia side rather than the mono-medium one. However, more specifically there are more significant and stronger correlation values with the multimedia by YouTube against most of the set metrics of writing fluency than the correlation values with multimedia by video games, films or audio books.

This may indicate that learners were engaging with the multi-media materials by YouTube more and to a greater extent than the rest of other learning sources in their online learning environment and that the multi-media materials are preferred over the mono-medium materials.

The correlation coefficient results of the learners’ time range of exposure to the respective online mono-medium and multimedia learning sources showed that there were insignificant correlations from the majority of the resources except for the YouTube and video games results (see Table 3 ) which were as follows:

One strong +ve correlation (r = .699) for the multimedia provided by video games;

Four strong +ve correlations (r = .783, .734, .767, .761) for the multimedia provided by YouTube.

The results of time range of exposure (Table 3 ) seem to conform with the above results of engagement rate (Table 2 ) that while learners were giving far greater amounts of their learning time and attention in the multimedia leaning environment, they gave little or no time and attention in the mono-medium learning environment. This may suggest that learners were more inclined towards the multi-media learning environment than the mono-medium environment for learning and improving writing online; more specifically, when compared to other online multi-media learning sources, YouTube as multimedia learning tool cum environment was preferred over other learning multimedia in as far as learning and improving writing is concerned.

Offline learning

The correlation coefficient results of the learners’ engagement rate with the respective offline mono-medium and multimedia learning sources showed insignificant correlation values across all the variables except for one strong +ve correlation value for video games (r = .763). (see Table 4 ).

These insignificant results may suggest that learners were not engaging their learning in the offline mono-medium and multimedia learning environments at all.

The correlation coefficient results of the learners’ time range of exposure with the respective offline mono-medium and multimedia learning sources showed that there are insignificant correlations from most of the resources in terms of time of exposure except for the reading of books variable results which are as follows: (see Table 5 )

Two strong +ve correlations (r = .713, .774) and one very strong +ve correlation (r = .842).

This may suggest that learners were giving a good deal of their learning time to reading books in the offline mono-medium leaning environment.

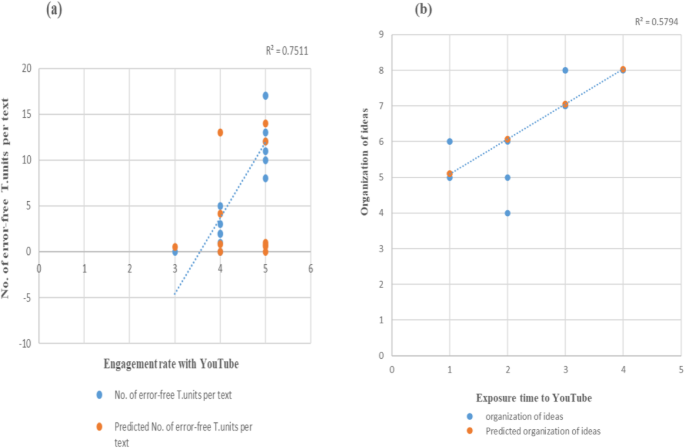

To summarize the correlation results of the above mentioned potential online/ offline mono-medium and multimedia learning materials/ environments, including YouTube media with regards to the participants’ engagement rate with and daily time range of exposure to each of these resources, it can be concluded with statistical evidence that there is a strong positive correlation between the writing fluency performance shown by this group of learners and multi-media (rather than mono-medium) learning environments found online (rather than offline) such as the suggested ICT YouTube tool, where text can be optionally available along with speech. Moreover, multi-media materials/ environments like YouTube as an example are more engaging compared to other language learning sources and hence learners were spending much more time using them which could have led to a more effective learning in their writing fluency; this may suggest the usefulness of ICT tools like YouTube as an example which have resulted in a more fluent use of written language in some (but not all) dimensions of writing fluency over time as learners could with the help of ICT handle their learning efficiently. However, from a statistical perspective, it is important to stress that correlation between any two variables does not mean causation but only that there is a relationship between them such as the kind of positive linear relationship which exists between engagement rate and time range of exposure in relation to the writing fluency metrics of this study (see Fig. 1 . a & b). These correlational findings which revealed such positive linkages among the data set encouraged the employment of the following regression analysis.

a Sample of strongly positive linear correlation. b Sample of moderately positive linear correlation

Regression analysis results

Regression analysis estimated the variation produced by engagement rate with and time range of exposure to YouTube as a source of learning and improving writing on the writing fluency metrics in this study.

The regression analysis results for the engagement rate showed a range of low, moderate and high R Square values (only the moderate and high values were highlighted in the table below). The moderate R Squared values were ( R 2 = .367, .358, .536) and the high values were ( R 2 = .751, .712). R squared values represented the proportion of the variance for the respective writing fluency metrics explained by the engagement rate as a predictor. (see Table 6 ).

Also, most, but not all, of the actual coefficients p values (used to test the null hypothesis where the coefficient is equal to zero i.e., meaning there is no effect while a low p value < 0.05 indicating that the null hypothesis can be rejected) shown in this table were too small, p < 0.05. These values also signified a significant linear relationship between the engagement rate with YouTube against their respective writing fluency metrics under study (see Fig. 1 . (a)). The Significance F. values (these values expressed the results of the F. statistic used to measure the significance of the model and the level of significance) were significant as they were well below the P < 0.05.

So, it may be suggested with statistically significant P and R Squared values of this regression that the engagement rate with the suggested YouTube channel can variably (moderate-high range) explain between 0.35 to 0.75% of the fluency improvement in the learners’ writing for the corresponding writing fluency variables.

The regression analysis results for the time range of exposure showed a range of low and moderate R Square values (only the moderate values were highlighted in the table below). R squared values represented the proportion of the variance for the respective writing fluency metrics explained by the exposure time rate as a predictor (see Table 7 ). Also, most, but not all, of the actual coefficients p values shown in this table were too small, p < 0.05. These values signified a significant linear relationship between the time range of exposure to YouTube against their respective writing fluency metrics under study (see Fig. 1 . (b)). The Significance F . values were significant as they were well below the P < = .05.

So, it may well be suggested that with statistically significant P and R Squared values of this regression that the time range of exposure to the suggested YouTube channel can variably (low-moderate range) explain between 0.53 to 0.61% of the fluency improvement in the learners’ writing.

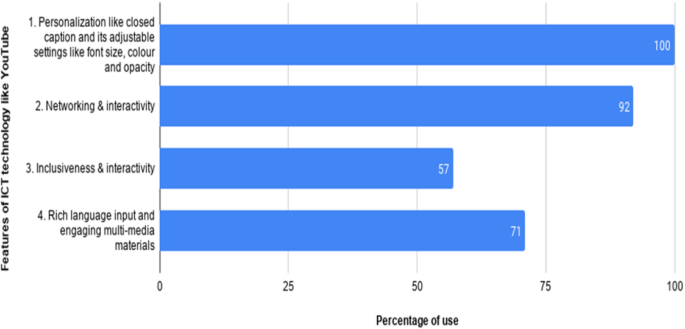

Frequency distributions

Frequency Distributions were run on data responses of the questionnaire for the following dichotomous (Yes/No) questions (Table 8 ) to determine the percentages of learners’ active use of ICT with regards to its features of personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness and as a resource for rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving English writing. Percentages of use for these ICT features can also be found in (Fig. 2 ).

Features of ICT technology like YouTube Vs. Percentage of active use by this group of learners while learning English

From the frequency distributions analysis, it can be seen that all of the participants used the YouTube closed captions and its adjustable related settings of font size, colour, opacity and playback speed when learning and improving writing (Question 30 above). (Question 31 above) showed that nearly all the participants shared with other learners interesting YouTube video materials for learning writing and learnt from what others or YouTube itself suggested them for that matter. (Question 32 above) showed that more than half of the participants used what they thought and learnt through these YouTube videos whenever they wrote in English. The majority of the participants did subscribe and passionately follow the YouTube channels due to their rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving your English writing (Question 33 above). Taken together, analyzing these frequency distributions indicated that the participants actively used ICT tools like YouTube with regards to its features of personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness and as a resource for rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving English writing (see Table 8 ).

Qualitative results

Content analysis.

In general, the results of this qualitative analysis supported the quantitative findings and brought more information about learners’ personal and contextual perspectives on the affordances of YouTube videos and how they thought YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting according to their experience. (see Tables 9 and 10 ). Participants were asked to choose from the answers given to these closed-ended questions what they thought applied to them according to their personal learning experience. The following tables are learners’ responses (given in numbers and percentages) in the affirmative for the two-closed questions (Q.34 & 35) in the questionnaire.

Percentages of participants’ responses in this simple content analysis varied over how they thought the affordances of YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting. Nevertheless, the majority of participants, in response to each of the above statements (see Tables 9 and 10 ), thought that the videos aided in different ways in the development and learning of writing. Overall, the participants found that the affordances of YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting with respect to the above listed affordances of YouTube (see Tables 9 and 10 ).

Discussions

This study examined the potential role and impact smart of learning environment of ICT tools like YouTube on learners’ fluency of language use and expression in their daily written communication. Three main areas related to the main research questions were analysed in this study.

the participants’ English writing learning experience of both the online and offline English learning resources, including YouTube with regards to their engagement rate with and daily time range of exposure to each of these resources;

the participants’ actual use of YouTube in particular as an ICT tool for creating the intended smart learning environment with respect to its features of personalization, networking and interactivity, inclusiveness and as a resource for rich language input and engaging multi-media materials for learning and improving English writing; and

participants’ personal and contextual perspectives on the affordances of YouTube videos and how they thought YouTube videos made learning and improving writing easy and interesting.

Previous research in this area seemingly devoted considerable effort and emphasis on the impact of YouTube usage in the classroom. In this regard, this research has gone a step further by examining the potential impact of such usage on learners’ writing fluency in particular. The quantitative findings of the T. Test (Table 1 ) clearly show some progress in the writing fluency post the integration of YouTube as a tool of language learning over the course of five months for this group of learners. Nonetheless, the T. Test results also show that there is a statistically significant difference only in terms of the number of error-free T. units and organization of ideas but not across all the outcome variables which were used as indicators of writing fluency in this work. The findings of this T. Test support previous studies such as those by Pratiwi ( 2011 ) and Anggraeni ( 2012 ) who reported that YouTube videos help the students to explore main ideas, organize ideas, choose right words to create sentences and paragraphs, produce grammatically correct sentences and use mechanic (punctuation and spelling) in writing. Thus, YouTube is effective in helping the students to better write, quantity and quality-wise, in English.