Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

Duke Study: Homework Helps Students Succeed in School, As Long as There Isn't Too Much

The study, led by professor Harris Cooper, also shows that the positive correlation is much stronger for secondary students than elementary students

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

It turns out that parents are right to nag: To succeed in school, kids should do their homework.

Duke University researchers have reviewed more than 60 research studies on homework between 1987 and 2003 and concluded that homework does have a positive effect on student achievement.

Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology, said the research synthesis that he led showed the positive correlation was much stronger for secondary students --- those in grades 7 through 12 --- than those in elementary school.

READ MORE: Harris Cooper offers tips for teaching children in the next school year in this USA Today op-ed published Monday.

"With only rare exception, the relationship between the amount of homework students do and their achievement outcomes was found to be positive and statistically significant," the researchers report in a paper that appears in the spring 2006 edition of "Review of Educational Research."

Cooper is the lead author; Jorgianne Civey Robinson, a Ph.D. student in psychology, and Erika Patall, a graduate student in psychology, are co-authors. The research was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

While it's clear that homework is a critical part of the learning process, Cooper said the analysis also showed that too much homework can be counter-productive for students at all levels.

"Even for high school students, overloading them with homework is not associated with higher grades," Cooper said.

Cooper said the research is consistent with the "10-minute rule" suggesting the optimum amount of homework that teachers ought to assign. The "10-minute rule," Cooper said, is a commonly accepted practice in which teachers add 10 minutes of homework as students progress one grade. In other words, a fourth-grader would be assigned 40 minutes of homework a night, while a high school senior would be assigned about two hours. For upper high school students, after about two hours' worth, more homework was not associated with higher achievement.

The authors suggest a number of reasons why older students benefit more from homework than younger students. First, the authors note, younger children are less able than older children to tune out distractions in their environment. Younger children also have less effective study habits.

But the reason also could have to do with why elementary teachers assign homework. Perhaps it is used more often to help young students develop better time management and study skills, not to immediately affect their achievement in particular subject areas.

"Kids burn out," Cooper said. "The bottom line really is all kids should be doing homework, but the amount and type should vary according to their developmental level and home circumstances. Homework for young students should be short, lead to success without much struggle, occasionally involve parents and, when possible, use out-of-school activities that kids enjoy, such as their sports teams or high-interest reading."

Cooper pointed out that there are limitations to current research on homework. For instance, little research has been done to assess whether a student's race, socioeconomic status or ability level affects the importance of homework in his or her achievement.

This is Cooper's second synthesis of homework research. His first was published in 1989 and covered nearly 120 studies in the 20 years before 1987. Cooper's recent paper reconfirms many of the findings from the earlier study.

Cooper is the author of "The Battle over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents" (Corwin Press, 2001).

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What we know about online learning and the homework gap amid the pandemic

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time – an experience often called the “ homework gap ” – may continue to feel the effects this school year.

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home.

Children across the United States are returning to physical classrooms this fall after 18 months at home, raising questions about how digital disparities at home will affect the existing homework gap between certain groups of students.

Methodology for each Pew Research Center poll can be found at the links in the post.

With the exception of the 2018 survey, everyone who took part in the surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

The 2018 data on U.S. teens comes from a Center poll of 743 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted March 7 to April 10, 2018, using the NORC AmeriSpeak panel. AmeriSpeak is a nationally representative, probability-based panel of the U.S. household population. Randomly selected U.S. households are sampled with a known, nonzero probability of selection from the NORC National Frame, and then contacted by U.S. mail, telephone or face-to-face interviewers. Read more details about the NORC AmeriSpeak panel methodology .

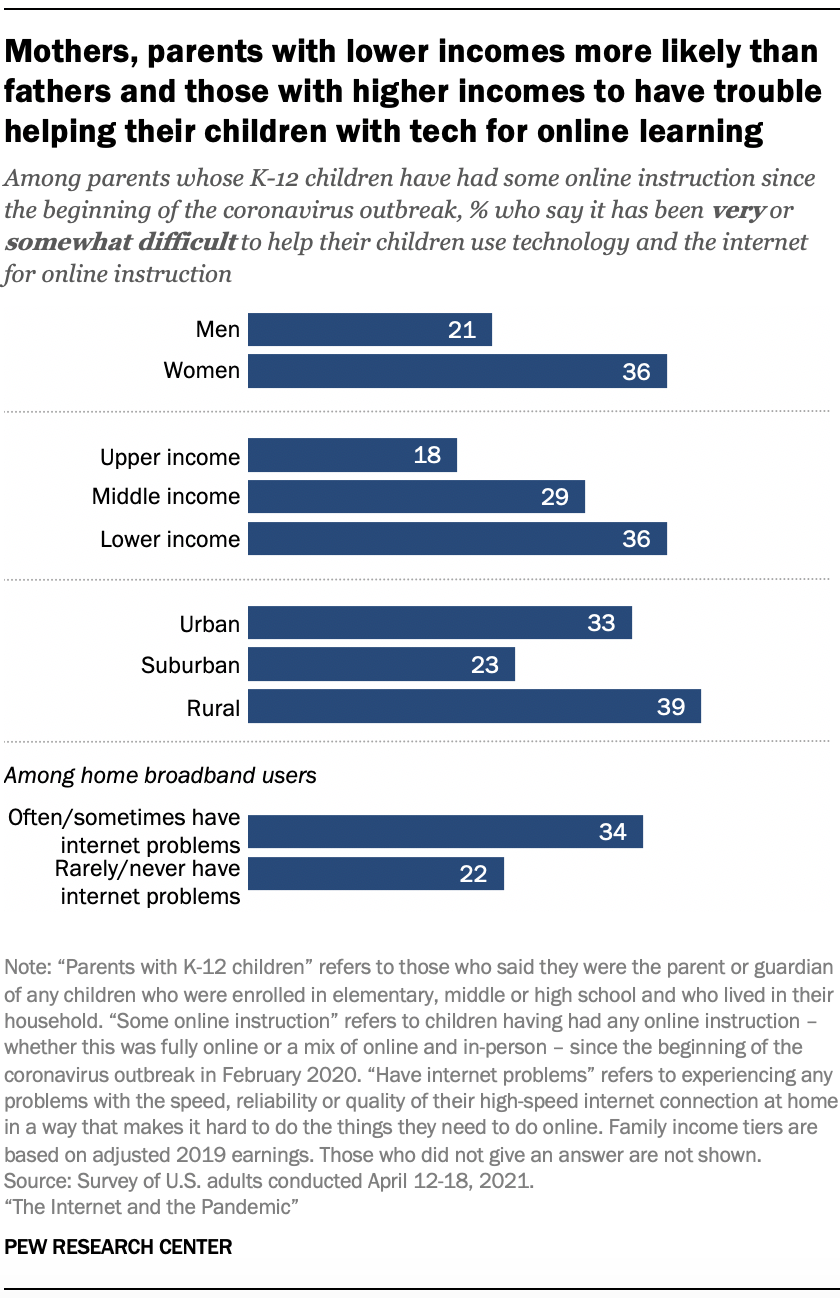

Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 30% of these parents said it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet as an educational tool, according to an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey .

Gaps existed for certain groups of parents. For example, parents with lower and middle incomes (36% and 29%, respectively) were more likely to report that this was very or somewhat difficult, compared with just 18% of parents with higher incomes.

This challenge was also prevalent for parents in certain types of communities – 39% of rural residents and 33% of urban residents said they have had at least some difficulty, compared with 23% of suburban residents.

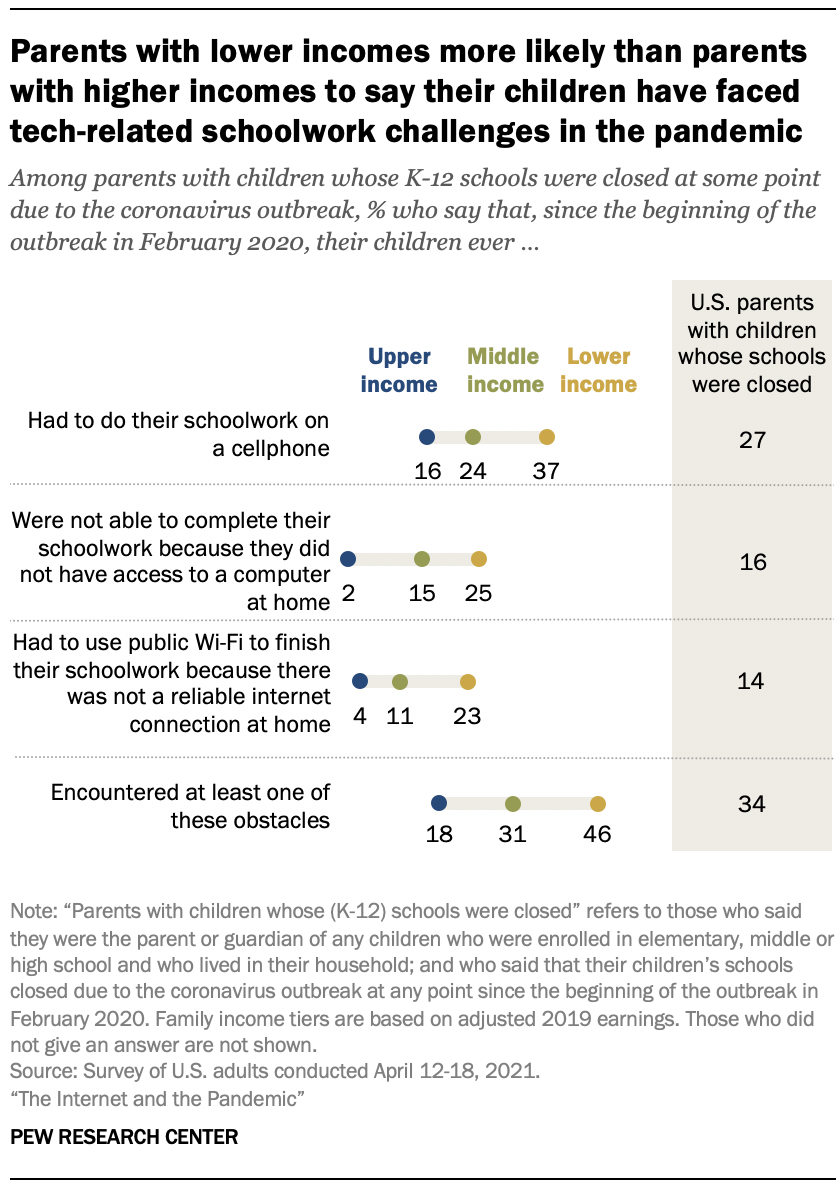

Around a third of parents with children whose schools were closed during the pandemic (34%) said that their child encountered at least one technology-related obstacle to completing their schoolwork during that time. In the April 2021 survey, the Center asked parents of K-12 children whose schools had closed at some point about whether their children had faced three technology-related obstacles. Around a quarter of parents (27%) said their children had to do schoolwork on a cellphone, 16% said their child was unable to complete schoolwork because of a lack of computer access at home, and another 14% said their child had to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

Parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed amid COVID-19 were more likely to say their children faced technology-related obstacles while learning from home. Nearly half of these parents (46%) said their child faced at least one of the three obstacles to learning asked about in the survey, compared with 31% of parents with midrange incomes and 18% of parents with higher incomes.

Of the three obstacles asked about in the survey, parents with lower incomes were most likely to say that their child had to do their schoolwork on a cellphone (37%). About a quarter said their child was unable to complete their schoolwork because they did not have computer access at home (25%), or that they had to use public Wi-Fi because they did not have a reliable internet connection at home (23%).

A Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that, at that time, 59% of parents with lower incomes who had children engaged in remote learning said their children would likely face at least one of the obstacles asked about in the 2021 survey.

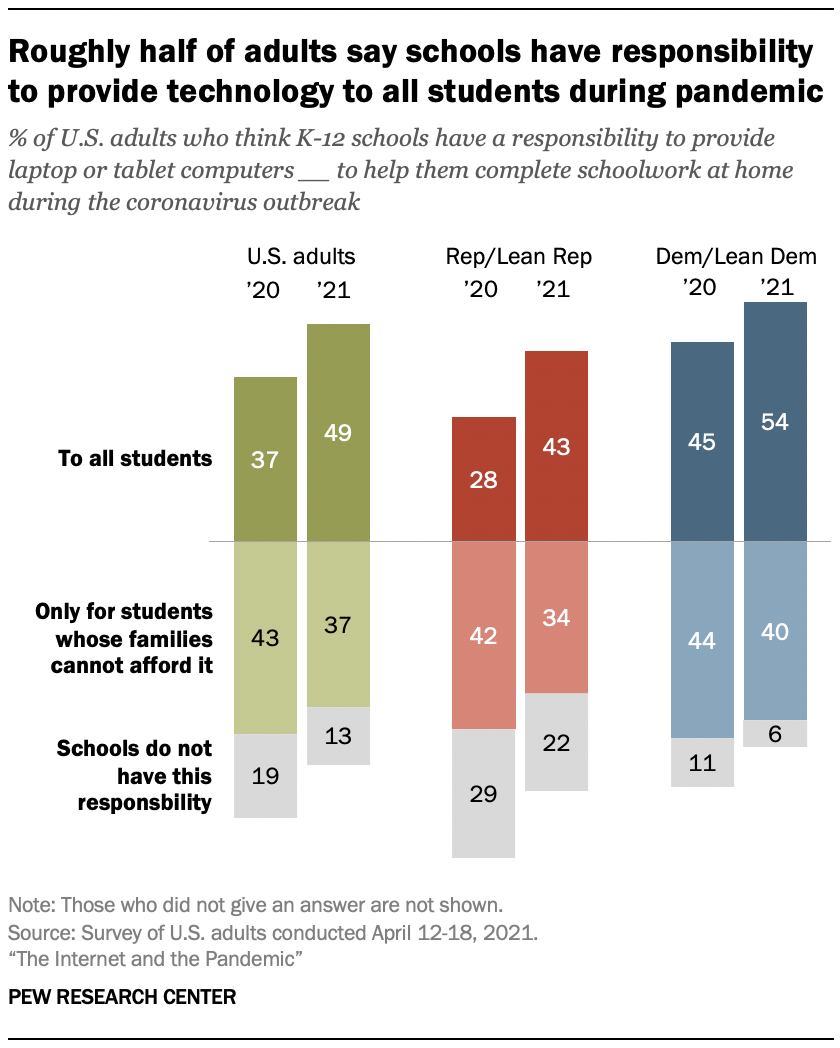

A year into the outbreak, an increasing share of U.S. adults said that K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork at home during the pandemic. About half of all adults (49%) said this in the spring 2021 survey, up 12 percentage points from a year earlier. An additional 37% of adults said that schools should provide these resources only to students whose families cannot afford them, and just 13% said schools do not have this responsibility.

While larger shares of both political parties in April 2021 said K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide computers to all students in order to help them complete schoolwork at home, there was a 15-point change among Republicans: 43% of Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party said K-12 schools have this responsibility, compared with 28% last April. In the 2021 survey, 22% of Republicans also said schools do not have this responsibility at all, compared with 6% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

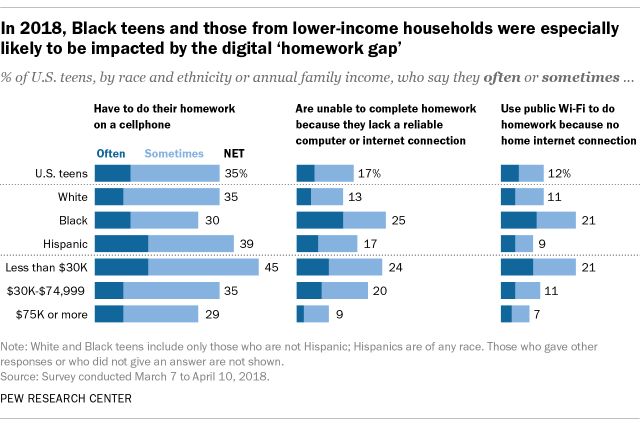

Even before the pandemic, Black teens and those living in lower-income households were more likely than other groups to report trouble completing homework assignments because they did not have reliable technology access. Nearly one-in-five teens ages 13 to 17 (17%) said they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, a 2018 Center survey of U.S. teens found.

One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often. Just 4% of White teens and 6% of Hispanic teens said this often happened to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

A wide gap also existed by income level: 24% of teens whose annual family income was less than $30,000 said the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibited them from finishing their homework, but that share dropped to 9% among teens who lived in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Technology

- Digital Divide

- Education & Learning Online

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center .

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, mental health and the pandemic: what u.s. surveys have found, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Search menu

Research analysis: getting the most out of homework.

If you have a spare couple of minutes and you are feeling mischievous then you can quite easily stir up a hornet’s nest by Tweeting about education’s sacred cow – homework. People have strong opinions on this and they do not hold back...

We have a difficult relationship with homework. Teachers, parents and students all have a view on its effectiveness and those views are often highly charged and pull in different directions (Hallam, 2006).

Some say it is a harmful practice that sabotages family life (and it does). Homework is a parental ball and chain that often leads to meltdowns, tears and slammed doors. It can create anxiety, limit learning, overburden and disengage overloaded pupils and can have a negative impact on wellbeing (Kralovec & Buell, 2000). Alfie Kohn (2006) in The Homework Myth thinks schools should set their default policy to “no homework”.

On the other side of the coin, those who back homework argue that it supports learning, practice and rehearsal, personal development, time management skills and preparation for later life.

But homework feeds on myths and things are not black and white. Much of what is said about homework is based on tradition rather than what we know about effective teaching and learning (Vatterott, 2008).

Decisions have to be made based on what the evidence is telling us and whether the claims for or against homework have a sound empirical basis.

What does the research tell us?

Homework has been extensively researched and studies from across the Western world tell us that it has no appreciable impact (low and moderate) on children’s learning and academic achievement and may lead to poorer outcomes overall. Well, in part.

If, however, we look at the Education Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) Teaching and Learning Toolkit evidence summary for secondary homework then we will find that homework is much more effective with older children. It states: “The evidence shows that the impact of homework, on average, is five months’ additional progress.

However, beneath this average there is a wide variation in potential impact, suggesting that how homework is set is likely to be very important. There is some evidence that homework is most effective when used as a short and focused intervention.”

However, the evidence is also clear that homework has zero effect on achievement for under-11s, as Professor John Hattie found in his Visible Learning meta-analysis (2009).

In 2014 in a BBC Radio 4 interview Prof Hattie said: “Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger ... which is why we need to get it right, not why we need to get rid of it.

“Certainly I think we get over obsessed with homework. Five to 10 minutes has the same effect of one hour to two hours. The worst thing you can do with homework is give kids projects. The best thing you can do is to reinforce something you have already learnt.”

If we delve into Prof Hattie’s research a little further it shows that the effect size at primary age is 0.15 and for secondary students it is 0.64 (the average impact being 0.40). This shows that homework for secondary students has an “excellent” effect, if done well.

As always, what is measured has an impact on the scale of the effect and we are dealing with averages here – so some forms of homework are more likely to show an effect than others. And Professor Dylan Wiliam said at a ResearchEd event in 2014 that “most homework teachers set is crap” (YouTube, 2017).

We all know that homework can be token, poorly defined or even given as a punishment. Homework can be a public relations exercise to make a school look good and a crowd-pleaser to keep parents happy.

We also know that unless teachers ensure that the activities set are meaningful and relevant to current learning, they become largely redundant.

In other words, homework can be effective when it is the right type of homework and we should continue setting it (Kelleher, 2017). Indeed, Marzano and Pickering (2007) say that “teachers should not abandon homework, instead, they should improve its instructional quality”.

Homework does serve a purpose but it has to be purposeful. In Prof Hattie’s own words, when homework is not deliberate practice, it is pointless (The Conversation, 2016).

So what can we do?

MacBeath and Turner (1990) suggest a number of sensible and reasonable ideas:

- Homework should be clearly related to on-going classroom work.

- There should be a clear pattern to class work and homework.

- Homework should be varied.

- Homework should be manageable.

- Homework should be challenging but not too difficult.

- Homework should allow for individual initiative and creativity.

- Homework should promote self-confidence and understanding.

- There should be recognition or reward for work done.

- There should be guidance and support.

Cathy Vatterott, aka the “Homework Lady”, has suggested that “there is a growing suspicion that something is wrong with homework”. In her book Rethinking Homework (2018), she argues that most teachers have never been properly trained in effective homework practices.

Vatterott has also identified five fundamental characteristics of good homework: purpose, efficiency, ownership, competence, and aesthetic appeal (Vatterott, 2010).

- Purpose: All homework assignments are meaningful and students must also understand the purpose of the assignment and why it is important in the context of their academic experience.

- Efficiency: Homework should not take a disproportionate amount of time and needs to involve some hard thinking.

- Ownership: Students who feel connected to the content learn more and are more motivated. Providing students with choice in their assignments is one way to create ownership.

- Competence: Students should feel competent in completing homework and so we need to abandon the one-size-fits-all model. Homework that students cannot do without help is not good homework.

- Inspiring: A well-considered and clearly designed resource and task impacts positively upon student motivation.

So do we need to turn the age-old concept of homework on its head? Homework clearly needs greater attention and redesigning and that includes what Mark Creasy calls “unhomework” (2014), where children set their own learning and targets for homework and then it is self and/or peer assessed.

Or as Russel Tarr suggests, why not give students a choice, takeaway menu style? He says that “giving students the flexibility to choose the content and/or the outcome of their homework assignments increases engagement and promotes independent learning” (Tarr, 2015).

So assignments following the above suggestions and those found in the EEF’s evidence summary will go a long way to improving the image, intent, implementation and impact of secondary homework.

And finally...

Where effective schools do set homework, they guarantee that is it is in line with their global aims and vision for teaching, learning and assessment. In particular, both the level of challenge and the feedback are considered to ensure that homework promotes a greater love of school and interest in learning.

The Teaching Schools Council’s Effective primary teaching practice report (2016) outlined that schools employing homework successfully are clear about:

- Its purpose: communicating with parents and sharing with them why their children do or do not have homework. The school makes sure that children clearly understand its purpose and no pupils lose out.

- The impact on teacher workload: following up, but in a way that does not disproportionately add to teacher workload.

- Limiting the time that children spend doing it: suggesting a cut-off point even if children have not completed everything. The US rule of thumb of “10 minutes per grade” is a sensible guide (this rule was suggested by researcher Harris Cooper – 10 to 20 minutes per night in the first grade, and an additional 10 minutes per grade level thereafter).

- The level of challenge: making sure children can succeed without too many demands and without needing to ask their parents for lots of help.

- The social context: ensuring that any homework set reflects different pupil experiences, background, and types of parental involvement.

Homework does not need to be abandoned but it does need far better management, especially in relation to how we communicate with parents. We need to get it right and start asking whether it is really making any difference.

- John Dabell is a teacher, teacher trainer and writer. He has been teaching for 25 years and is the author of 10 books. He also trained as an Ofsted inspector. Visit www.johndabell.com and read his previous best practice articles for SecEd via http://bit.ly/2gBiaXv

Further information & research

- Homework: Its uses and abuses, Hallam, Institute of Education, UCL, 2006: http://bit.ly/31xXo0u

- The End of Homework: How homework disrupts families, overburdens children, and limits learning, Kralovec & Buell, Beacon Press, 2000.

- The Homework Myth: Why our kids get too much of a bad thing, Kohn, De Capo Books, 2006: www.alfiekohn.org/homework-myth/

- Homework Myths, Vatterott, The Homework Lady, February 2008: http://bit.ly/2H34wua

- Homework (Secondary) Evidence Summary, Teaching and Learning Toolkit, Education Endowment Foundation: http://bit.ly/2YGEGa5

- “Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”, John Hattie interview, BBC Radio 4, August 2014: https://bbc.in/2yWgcdK

- Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses on achievement, Professor John Hattie, 2009: https://visible-learning.org

- Why teaching will never be a research based profession, Dylan Wiliam presentation, ResearchEd, 2017: http://bit.ly/2MdFeO1

- How to shift a school towards better homework, Kelleher, The Learning Scientists, June 2017: http://bit.ly/3016QJA

- The case for and against homework, Marzano & Pickering, Educational Leadership, March 2007: http://bit.ly/2KK3unz

- Speaking with: John Hattie on how to improve the quality of education in Australian schools, The Conversation, May 2016: http://bit.ly/2H3SzUG

- Learning out of school: Homework, policy and practice, Research study commissioned by the Scottish Education Department, MacBeath & Turner, 1990: http://bit.ly/2KFR2Fu

- Rethinking Homework: Best practices that support diverse needs, Vatterott, ASCD, 2018.

- Five hallmarks of good homework, Vatterott, Educational Leadership, September 2010: http://bit.ly/2MfnodE

- Unhomework: How to get the most out of homework, without really setting it, Mark Creasy, Independent Thinking Press, 2014.

- Why students should set and mark their own homework, Mark Creasy, Guardian, April 2014: http://bit.ly/2KwP5MM

- Takeaway Homework, Tarr’s Toolbox, Tarr, 2015: www.classtools.net/blog/takeaway-homework

- Effective primary teaching practice, Teaching Schools Council, 2016: http://bit.ly/2TrXOCC

- The Institute for Effective Education’s Best Evidence in Brief has a selection of homework-related research which is worth a look: www.beib.org.uk/?s=Homework

Related articles

The traits of effective teaching (and teachers), seven principles of effective secondary homework, getting homework right and developing independent learners.

teacherhead

Zest for learning… into the rainforest of teaching.

Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say?

This is an excellent book. It is an attempt to distil the key messages from the vast array of studies that have been undertaken across the world into all the different factors that lead to educational achievement. As you would hope and expect, the book contains details of the statistical methodology underpinning a meta-analysis and the whole notion of ‘effect size’ that drives the thinking in the book. There is a discussion about what is measurable and how effect size can be interpreted in different ways. The key outcomes are interesting, suggesting a number of key factors that are likely to make the greatest impact in classrooms and more widely in the lives of learners.

My main interest here is to explore what Hattie says about homework. This stems from a difficulty I have when I hear or read, fairly often, that ‘research shows that homework makes no difference’. It is cited as a hard fact in articles such as this one by Tim Lott in the Guardian: Why do we torment kids with homework? Even though Tim is talking about his 6 year old, and cites research that refers to ‘younger kids’, too often the sweeping generalisation is applied to all homework for all students. It bugs me and I think it is wrong.

I have written about my views on homework under the heading ‘Homework Matters: Great Teachers set Great Homework’ . I’ve said that all my instincts as a teacher (and a parent) tell me that homework is a vital element in the learning process; reinforcing the interaction between teacher and student; between home and school and paving the way to students being independent autonomous learners. Am I biased? Yes. Is this based on hunches and personal experience? Of course. Is it backed up by research……? Well that is the question.

So, what does Hattie say about homework?

Helpfully he uses Homework studies as an example of the overall process of meta-analyses, so there is plenty of material. In a key example, he describes a study of five meta-analyses that capture 161 separate studies involving over 100,000 students as having an effect size d= 0.29. What does this mean? This is the best typical effect size across all the studies, suggesting:

- improving the rate of learning by 15% – or advancing children’s learning by about a year

- 65% of effects were positive

- 35% of effects were negative

- average achievement exceeded 62% of the levels of students not given homework.

However, there are other approaches such as the ‘common language effect’ (CLE) that compares effects from different distributions. For homework a d= 0.29 effect translates into a 21% chance that homework will make a positive difference. Or, from two classes, 21 times out of a 100, using homework will be more effective. Hattie then says that terms such as ‘small, medium and large’ need to be used with caution in respect of effect size. He is ambitious and won’t accept comparison with 0.0 as a sign of a good strategy. He cites Cohen as suggesting with reason that 0.2 is small, 0.4 is medium and 0.6 is large and later argues himself that we need a hinge-point where d > 0.4 is needed for an effect to be above average and d > 0.6 to be considered excellent.

OK. So what is this all saying. Homework, taken as an aggregated whole, shows an effect size of d= 0.29 that is between small and medium? Oh.. but wait… here comes an important detail. Turn the page: The studies show that the effect size at Primary Age is d = 0.15 and for Secondary students it is d = 0.64! Well, now we are starting to make some sense. On this basis, homework for secondary students has an ‘excellent’ effect. I am left thinking that, with a difference so marked, surely it is pure nonsense to aggregate these measures in the first place?

Hattie goes on to report that other factors make a difference to the results: eg when what is measured is very precise (eg improving addition or phonics), a bigger effect is seen compared to when the outcome is more ephemeral. So, we need to be clear: what is measured has an impact on the scale of the effect. This means that we have to throw in all kinds of caveats about the validity of the process. There will be some forms of homework more likely to show an effect than others; it is not really sensible to lump all work that might be done in between lessons into the catch-all ‘homework’ and then to talk about an absolute measure of impact. Hattie is at pains to point out that there will be great variations across the different studies that simply average out to the effect size on his barometers. Again, in truth, each study really needs to be looked at in detail. What kind of homework? What measure of attainment? What type of students? And so on…. so many variables that aggregating them together is more or less made meaningless? Well, I’d say so.

Nevertheless, d= 0.64! That matches my predisposed bias so I should be happy. q.e.d. Case closed. I’m right and all the nay-sayers are wrong. Maybe, but the detail, as always, is worth looking at. Hattie suggests that the reason for the difference between the d=0.15 at primary level at d=0.64 at secondary is that younger students can’t under take unsupported study as well, they can’t filter out irrelevant information or avoid environmental distractions – and if they struggle, the overall effect can be negative.

At secondary level he suggests there is no evidence that prescribing homework develops time management skills and that the highest effects in secondary are associated with rote learning, practice or rehearsal of subject matter; more task-orientated homework has higher effects that deep learning and problem solving. Overall, the more complex, open-ended and unstructured tasks are, the lower the effect sizes. Short, frequent homework closely monitored by teachers has more impact that their converse forms and effects are higher for higher ability students than lower ability students, higher for older rather than younger students. Finally, the evidence is that teacher involvement in homework is key to its success.

So, what Hattie actually says about homework is complex. There is no meaningful sense in which it could be stated that “the research says X about homework” in a simple soundbite. There are some lessons to learn:

The more specific and precise the task is, the more likely it is to make an impact for all learners. Homework that is more open, more complex is more appropriate for able and older students. Teacher monitoring and involvement is key – so putting students in a position where their learning is too complex, extended or unstructured to be done unsupervised is not healthy. This is more likely for young children, hence the very low effect size for primary age students.

All of this makes sense to me and none of it challenges my predisposition to be a massive advocate for homework. The key is to think about the micro- level issues, not to lose all of that in a ridiculous averaging process. Even at primary level, students are not all the same. Older, more able students in Year 5/6 may well benefit from homework where kids in Year 2 may not. Let’s not lose the trees for the wood! Also, what Hattie shows is that educational inputs, processes and outcomes are all highly subjective human interactions. Expecting these things to be reduced sensibly into scientifically absolute measured truths is absurd. Ultimately, education is about values and attitudes and we need to see all research in that context.

PS. If you are reading this from Sweden, Tack för läsning. Låt mig veta era tankar om denna fråga.

Update : Note that Hattie himself has commented on this blog post: https://teacherhead.com/2012/10/21/homework-what-does-the-hattie-research-actually-say/comment-page-1/#comment-536

(Slides from a Teach First session on homework are here: Teach First Homework )

See also Setting Great Homework: The Mode A:Mode B approach.

Share this:

87 comments.

[…] See Tom Sherrington’s (@HeadGuruTeacher) discussion of some of the research on homework in his blog-post here. […]

“The biggest mistake Hattie makes is with the CLE statistic that he uses throughout the book. In ‘Visible Learning, Hattie only uses two statistics, the ‘Effect Size’ and the CLE (neither of which Mathematicians use).

The CLE is meant to be a probability, yet Hattie has it at values between -49% and 219%. Now a probability can’t be negative or more than 100% as any Year 7 will tell you.”

https://ollieorange2.wordpress.com/2014/08/25/people-who-think-probabilities-can-be-negative-shouldnt-write-books-on-statistics/

[…] at the evidence on homework from Hattie, we’re committed to setting homework but need to be mindful that only certain types of […]

[…] Hattie has thrown some doubt over the effectiveness of homework as an intervention, wouldn’t it be better to, as Tom […]

Nice post… Though, here homework is to target students who are a bit older. Pupils at elementary level or less than 4years may not be taken serious on assignment issue.

Like Liked by 1 person

[…] mentions a couple of bits of research in his post regarding the effectiveness of homework on learning and although some studies suggest a […]

[…] of analogies with outdoor pursuits tasks like learning to abseil. If you look at the detail – for example the homework chapter as I did here – you also learn about the complexities of education research itself and the importance of […]

[…] Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say? […]

[…] as an example of the pitfalls of interpreting the results. I’ve written about this in full in this post. It was interesting to see, in a ranking of the Visible Learning effect sizes, that Drugs appears […]

I’m reading this from Sweden (although I am originally from the UK and trained to teach there). 7 years ago I did a piece of small action research as part of my masters degree looking at how I used homework. I was in the UK at the time. My findings, although much smaller scale, would support Hattie. Homework has an impact but you must design it properly was my basic conclusion. My problem is having to deal with the huge number of parent conversations and societal attitude towards homework in Sweden (which are generally negative), and school in general really, fuelled by the media and it’s anti-homework stance. My own feeling about the attitude is that academic learning should happen only in school. Even getting parents to do something so simple as read with their child can cause endless arguments. No it’s not all parents and it does depend a lot on your location. But that’s just my experience of the schools I have worked in.

Hi LUNATIKSCIENCE,

I am currently in the process of looking into a whole school home learning policy and I would be really interested to read the work you did. I have been trying to read as much research into home learning as possible, but getting some actual data would be great.

Would you be able to share any additional information in regards to your findings?

Many thanks Alasdair

Hi, sorry just noticed this comment. I can send you my paper that I wrote if you are still interested.

Yes please. That would be so useful.

Thanks very much.

Hi, I would also be really interested if you were happy to share your research. I am DH working in a Prep school that is in the midst of analysing our approach to homework. Thanks

[…] I posted a link to a pro-homework argument. Again today, I’ve stumbled across another–this one summarizing John Hattie’s Visible Learning on the […]

Reblogged this on The Maths Mann .

[…] When preparing for our leadership planning day yesterday, I was investigating how to build on-going professional teaching conversations (as an alternative to Performance Review) that I stumbled upon John Hattie again talking up collective teacher efficacy on the Principal Centre Radio podcast. If you are not familiar with Hattie, his name is rarely far from discussions about teacher effectiveness… Visible Learning, 1400 meta-analyses, 80,000 studies, 300 million students… what works best in education (still, his chosen research approach, meta-analysis, is now without its detractors or straightforward teacher criticism.) […]

[…] Feel free to leave comments/thoughts between meetings here e.g. Sam sent me this link: Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say? […]

But you make the assumption that educational achievement is per se, the only thing affected. Easy to see from the teacher /school perspective. But from the parent /home perspective, there may be many more valuable activities going on that are much more important than homework, to the growth of the human being. So these things need to be taken into account too. Where homework detracts from the time spent on these, then it could be good from a school education point of view but bad from a more all – round education point of view.

[…] Homework: What does the research say about its effectiveness? […]

[…] of the problem is that the research on homework, although plentiful, is unclear. In his post Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say? blogger, author of The Learning Rainforest and education consultant Tom Sherrington unpicks the […]

[…] I have explored issues with homework in various different posts. In particular, the research into homework by John Hattie is covered in detail in this post: Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say? […]

[…] Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say? […]

This is an excellent summary of Hattie’s work and gives us all good for thought about what could be meaningful and helpful and what to avoid when considering homework.

[…] ‘Homework: What does the Hattie research actually say?’ by Tom Sherrington. It’s important to keep in mind that all the research around homework applies to remote learning: Specific and precise tasks are more successful than longer tasks that involve complex problem solving, higher ability students benefit more than lower ability students, older students benefit more than younger students, and teacher monitoring is crucial. […]

[…] is more crucial for novices and less effective as students gain expertise, and homework has little impact on educational outcomes, particularly for young […]

[…] a lack of evidence is not the same as evidence that an approach is not successful. This echoes the comments Hattie made here about Visible Learning: “Visible Learning is a literature review, therefore it says what HAS happened not what COULD […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Hoops and Homework:

Academic rank and game day impact on wins in college basketball, by: andrew huang, monica paz parra, eric yao, introduction:.

As college athletics have become more competitive over the years, many have questioned the relationship that exists between academics and sports. Because of this, we wanted to get a better idea of this relationship and see how it impacts college basketball. In this report, we aim to explore if academic ranking influences the performance of college basketball teams. More specifically, we are looking at data from six randomly selected ACC schools where we observe whether their game performance changes on weekday games versus weekend games.

In order to answer this question, we conducted a multilevel analysis where we compared teams from schools ranked in the Top 30 against those in the Top 31-100, focusing on their win rates, scoring averages, and field goal attempts. We randomly selected 3 Top 30 schools, which are Duke (7), UNC (22), University of Virginia (24). We also randomly selected 3 schools that are ranked between 31-100, which are Boston College (39), NC State (60), University of Pittsburgh (67). We wanted to look into this topic because we believe that understanding the balance between academic achievement and athletic success is important for optimizing the overall development of student-athletes. This study could reveal important trends and patterns that help design educational and athletic programs that support student athletes. Moreover, insights from this research could lead to more effective recruitment strategies, where institutions can align their academic and athletic offerings to attract the best talent. Ultimately, by providing a more integrated approach to student-athlete development, schools can enhance their reputational standing and competitiveness in both academic and athletic arenas.

To answer this question, we decided to use college basketball data from the hoopR package in R, specifically from the ‘load_mbb_team_box’ to get the men’s college basketball team box scores. With this data, we filtered the team_abbreviation column to only include Duke, UNC, UVA, Boston College, NC State, and University of Pittsburgh. Since our study focuses on the effect between weekday games VS. weekend games, we need a column that contains the game date. However, the hoopR package only contains the game day. Thus, we used the game_date column to create a new column, named game_day that translates the date the game was played on to the day of the week it corresponds to.

Above we see the first 5 rows of our finalized data. The data includes unique identifiers for each game (game_id), as well as the date (game_date) and time (game_date_time) of when the matches were played. Additionally, the dataset contains identifiers for the teams (team_id, team_uid) and a slug representing the team names (team_slug), providing a straightforward way to reference the competing institutions, such as ‘nc-state-wolfpack’, ‘duke-blue-devils’, and ‘north-carolina-tar-heels’.

Exploratory Data Analysis:

Our first plot focuses on average field goal percentage between weekdays and weekends categorized by Top 30 and 31-100 ranked schools. The data suggests that there is a negligible difference in performance between schools in the Top 30 academic rank and those ranked 31 to 100, especially when comparing weekdays to weekends. Specifically, the Top 30 schools have a slightly higher field goal percentage on weekdays, while schools ranked 31 to 100 have a marginal edge on weekends. This could imply that while academic ranking may play a role in overall athletic success, as indicated in the previous wins data, the direct impact on specific metrics such as field goal percentage is less pronounced. The relatively equal performance across different days of the week also hints at a consistent level of athletic competency regardless of academic ranking. These findings could suggest that factors other than academic ranking, such as individual skill level, team dynamics, and specific game strategies, may have a more direct influence on the precision of athletic performance in this aspect.

Then we wanted to explore the win count between weekdays and weekends categorized by Top 30 and 31-100 ranked schools. According to the bar chart above, schools that are ranked within the Top 30 academically have a higher number of wins on both weekdays and weekends compared to those ranked between 31 and 100. This could indicate that higher academic standards may be associated with more effective athletic programs, or that the environment and resources at top-ranked institutions contribute positively to their athletic success. However, it’s important to consider other variables that might influence this outcome, such as the recruitment of athletes, investment in sports facilities, and the quality of coaching staff.

In general, our modeling stage was divided into three phases: a level one naive model, a level two model using the Two-Stage Modeling Approach, and some varying intercepts and slopes multilevel models. Since our dataset is very similar to the NFL passing data covered in the course, we decided to imitate the analysis techniques that were used in demos 6 and 7 in particular.

The first phase involves a naive logistic regression model, implemented using the glm() function in R. This model predicts the probability of a team winning based on the game day and the team’s top-30 status. Assumptions of this model include the independence of observations and binomial distribution of the response variable (team winner). However, given the nested structure of our data—multiple games for each team—these assumptions are likely violated, prompting the need for more sophisticated approaches. This initial model serves as a baseline to understand simple effects without adjustments for intra-team correlation, providing a preliminary insight into factors directly affecting game outcomes.

In the second phase, we will implement a Two-Stage Modeling Approach. First Stage: Separate logistic regression models are constructed for each team, which allows for capturing unique team behaviors and initial variability in winning probabilities across different game days. Second Stage: We analyze the distribution of intercepts and slopes derived from these individual models to understand broader patterns and potential outliers across teams. The main assumption here is that we believe teams are independent of each other, which is also the foundation for this approach. Generally, this approach was chosen to begin addressing within-team correlation without fully modeling these dependencies, providing a transition from the naive model to more complex structures. It offers a balance between complexity and interpretability, allowing us to isolate team-specific effects before considering deeper interactions in the data.

Phase three advances to varying intercepts and slopes of multilevel models, where we not only account for the non-independence of observations within teams but also allow the effect of predictors to vary by team. Since we decided to proceed with relatively more complicated models, we decided to look at a new variable ‘field_goals_attempted’ as we believe it may have a different relationship between the teams regarding the winning probability. Moreover, assumptions include normally distributed random effects for intercepts and slopes and a logistic link function for the binomial outcome of winning. These models are motivated by our sports question regarding how different factors influence game outcomes. The choice of multilevel modeling aligns with the complex hierarchical structure of our data, ensuring that the dependencies and variances within and between teams are appropriately modeled.

To effectively evaluate and compare the performance of the statistical models developed in the three phases, we used several criteria, which are the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for model selection, as well as the analysis of residuals and consideration of the significance of model coefficients. The AIC is particularly useful for comparing models with different numbers of parameters, providing a balance between model complexity and goodness of fit. Besides, for the multilevel models, we will look at the random effects’ variance components to evaluate if these models adequately capture the hierarchical structure of the data. Since we will be implementing various different types of models, we decided to use a relatively easier way to compare them. As of now, the reason we evaluated our models this way is due to the complex nature of sports analytics, where models must deal with hierarchical data structures and varying effects across teams. The chosen methods of comparison and evaluation are designed to test our models’ effectiveness in answering key questions about NCAA basketball performance.

To this end, our analysis includes methods for quantifying uncertainty for all model estimates. Standard errors, derived directly from our summary output, provide a measure of the variability in our estimates due to sampling error. From these standard errors, we will compute confidence intervals for each coefficient, which offer a range of plausible values for the true effect size and allow us to assess the precision of our estimates. Within the multilevel modeling framework, we will use the output from the lmer and glmer functions to obtain estimates of variance components for random effects. These estimates will be crucial in understanding the uncertainty at different levels of the data hierarchy—individual games within teams—and will be particularly relevant when interpreting the random slopes, which describe how the relationship between predictors and outcomes varies across teams. The nature of NCAA basketball data demands an approach that acknowledges and quantifies uncertainty at multiple levels. Our methods are selected to ensure that our uncertainty quantification is as rigorous and relevant as the estimates themselves, tailored to the context of NCAA basketball data.

The initial analysis involved a naive logistic regression model, which sought to predict the probability of a team winning based on the day of the game and whether the team was ranked in the top 30. This model served as a baseline to understand the influence of game scheduling and team strength without accounting for inter-team variations and other complexities. Our summary output sets Monday games as the baseline. The coefficient for the intercept was 1.23356 with a standard error of 0.66217, indicating a significant base effect on Mondays (p=0.0625). The coefficients for game days from Tuesday to Sunday showed varied effects, with Tuesday games showing a notable decrease in winning probability (coefficient = -1.34008, p=0.0601). Being in the top 30 increased the probability of winning (coefficient = 0.50343, p=0.0965), suggesting a competitive advantage for higher-ranked teams.

The second phase involved a two-stage modeling approach. Initially, separate logistic regression models were computed for each team to explore within-team variability. Subsequently, the intercepts and slopes from these models were aggregated and analyzed to capture overarching trends across teams. In the results, significant variability was observed in the winning probability across different game days, indicating that team performance dynamics vary significantly throughout the week. Additionally, when intercepts and slopes were aggregated, the analysis showed some teams having consistently higher or lower performance irrespective of the game day. The first histogram below shows the distribution of regression estimates for different game days. From the first plot, the estimates for weekend games show a spread with multiple peaks, suggesting varying effects on team performance. To better understand the relationship, we cutoff the outliers by setting a threshold of the absolute value of 20 as shown in plot 2. The estimates are distributed around a central value with slight right skewness, suggesting that for some teams, Mondays might have a slightly positive impact on performance. The estimates for weekends show a spread around zero, with most values slightly negative. This could suggest a slight disadvantage or variation in performance during weekend games.

The third phase involved the deployment of more complex multilevel models to more accurately model the dependency structures within the data, capturing both the fixed effects of known covariates and the random effects associated with individual team variances. We also categorized Fridays to Mondays as Weekends and Tuesdays to Thursdays as Weekdays. The initial model started with varying intercepts only for each team to capture the baseline differences in winning probabilities among teams, without including game day effects or other covariates. The AIC for this model is 276.9, which means it provides a basic understanding of how much team variation exists regarding the outcome. The second model is with additional covariates (fixed effects). Here, field_goals_attempted, top_30 status, and weekend were added as fixed effects to observe their influence alongside the varying intercepts for each team. The AIC is 278.5, which means the increase in AIC despite additional covariates indicated a nuanced understanding but also suggested complexity without significant improvement in model fit. Lastly, we have a varying slopes model, which allows the effect of field_goals_attempted to vary by team, recognizing that different teams might react differently to game dynamics. This model had the highest AIC of 281.3, which often suggests overfitting or an unnecessary complexity in the context of the available data.

The varying intercepts model confirmed significant differences in baseline winning probabilities across teams, emphasizing the unique characteristics of each team. The addition of game-specific covariates like field_goals_attempted showed variable impacts on the outcome, underscoring the diverse strategies and performance factors at play in different games and teams. Finally, the varying slopes model indicated complex interactions within the teams concerning field_goals_attempted, suggesting that teams respond uniquely to the dynamics of each game. To compare the models, the models’ complexity increased, but the AIC scores from multilevel modeling (ranging from 276.9 to 281.3) suggested an improved fit compared to the naive model (AIC = 275.11), indicating that accounting for random effects provides a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing game outcomes. Furthermore, variables like top_30 and field_goals_attempted were found to have differential impacts on winning probability, depending on the team, highlighting the importance of contextual team factors.

In conclusion, our chosen Model 1, which integrates a fixed effect for field goals attempted along with random intercepts for each team, emerges as the most straightforward and statistically robust model based on its low AIC. This model elucidates that neither playing on weekends nor the volume of field goals attempted significantly alters the odds of winning when considering the calculated uncertainty. Specifically, the standard errors associated with these estimates indicate a broad range of potential true effects, reflecting significant uncertainty in these predictors. Furthermore, while being a top 30 team appears to enhance winning odds, the confidence intervals around this estimate suggest this effect is not statistically definitive. These findings highlight the nuanced and complex nature of sports competition outcomes and suggest further analytical avenues to explore additional variables that might significantly impact game results, potentially with narrower confidence intervals to reduce result uncertainty.

Discussion:

In conclusion, our study has provided valuable insights into the relationship between academic rankings and athletic performance, showing that while game timing does not significantly impact outcomes, there is a tendency for teams from top-ranked universities to have better odds of winning, potentially due to better recruitment, funding, and motivation. Although Model 1 offers a balanced analysis, we acknowledge the limitations of not accounting for variables such as coaching and individual player performance. For future study, a robust approach could involve analyzing the effect of individual student-athlete academic progress on athletic performance, potentially using GPA as a proxy for academic commitment and its correlation with sports success. Additionally, it would be beneficial to explore the specific impact of coaching by evaluating the relationship between coaching staff credentials and team performance metrics.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Homework has long been a topic of social research, but rela-tively few studies have focused on the teacher's role in the homework process. Most research examines what students do, and whether and ...

RESEARCH SAYS: Homework serves the distinct purpose to "provide students with an opportunity to practice," according to a 25 year quantitative metaanalysis (Cooper, et al 2006). Homework has the highest impact on achievement in high school and the lowest in elementary school (Hattie 2009, p.235). According to Balli

The research. The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive ...

HARRIS COOPER is a Professor of Psychology and Director of the Program in Education, Box 90739, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0739; e-mail [email protected] His research interests include how academic activities outside the school day (such as homework, after school programs, and summer school) affect the achievement of children and adolescents; he also studies techniques for improving ...

a summary of educational research on homework, discusses the elements of ef - fective homework, and suggests practical classroom applications for teachers. ... In 2006, Cooper, Robinson, and Patall conducted a meta-analysis of . HOMEWORK FOR INCLUSIVE CLASSROOMS 171 homework-related research and found that there is a positive relationship be-

Traditional homework: research findings. Homework is an educational tool present in classrooms from distinct cultures and is assigned to, ... with a preplanned review protocol specifying inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies and subsequent data analysis. Only original research, peer-reviewed, and English-language studies were ...

The Importance of Homework and Homework Research Homework is an important part of most school-aged children's daily routine. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (Campbell et al., 1996), over two-thirds of all 9-year-olds and three-quarters of all 13- and 17-year-olds reported doing some homework every day.

Too much homework may diminish its effectiveness. While research on the optimum amount of time students should spend on homework is limited, there are indications that for high school students, 1½ to 2½ hours per night is optimum. Middle school students appear to benefit from smaller amounts (less than 1 hour per night).

Introduction. Homework is an important part of the learning and instruction process. Each week, students around the world spend 3-14 hours on homework, with an average of 5 hours a week (Dettmers et al., 2009; OECD, 2014).The results of the previous studies and meta-analysis showed that the homework time is correlated significantly with students' gains on the academic tests (Cooper et al ...

It turns out that parents are right to nag: To succeed in school, kids should do their homework. Duke University researchers have reviewed more than 60 research studies on homework between 1987 and 2003 and concluded that homework does have a positive effect on student achievement. Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology, said the research ...

Homework is a pervasive and controversial practice, and a common culprit for producing ... research focused on this question; how can various approaches to the practice of homework ... same analysis, while a positive relationship did exist across all experiment types and levels between homework assigned and academic performance, the effect is ...

Pedagogical Research 2022, 7(2), em0122 e-ISSN: 2468-4929 https://www.pedagogicalresearch.com Research Article OPEN ACCESS An Analysis About the Relationship Between Online Homework and Perceived Responsibility, Self-Efficacy and Motivation Levels of the Students Ceyla Odabas 1* 1 Foreign Languages College , Gaziantep University TURKEY

The main objective of this research is to analyze how homework assignment strategies in schools affect students' academic performance and the differences in students' time spent on homework. Participants were a representative sample of Spanish adolescents ( N = 26,543) with a mean age of 14.4 (±0.75), 49.7% girls.

In this research, meta-analysis was adopted to determine the effect of homework assignments on students' academic achievement. The effect sizes of the studies included in the meta-analysis were compared with regard to their methodological characteristics (research design, sample size, and publication bias) and substantive characteristics ...

America's K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time - an experience often called the "homework gap" - may continue to feel the effects this school year. Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found ...

Highlights of Research Homework has a positive effect on achievement, but the effect varies dramatically with grade level. For high school students, homework has substantial positive effects. Junior high school students also benefit from homework, but only about half as much. For elementary school students, the effect of homework on achievement ...

Homework is a parental ball and chain that often leads to meltdowns, tears and slammed doors. It can create anxiety, limit learning, overburden and disengage overloaded pupils and can have a negative impact on wellbeing (Kralovec & Buell, 2000). Alfie Kohn (2006) in The Homework Myth thinks schools should set their default policy to "no ...

Homework 5 - student -1.docx. Research Methods and Data Analysis in Psychology I (PSY: 2811) Homework #5 (4 points) This homework is due for all sections by 11:59pm, December 5th. Submit your answers by saving this page as "yourname.docx" and submit your document as a file upload unde

So, what Hattie actually says about homework is complex. There is no meaningful sense in which it could be stated that "the research says X about homework" in a simple soundbite. There are some lessons to learn: The more specific and precise the task is, the more likely it is to make an impact for all learners.

Research Methods and Data Analysis in Psychology I (PSY: 2811) Homework #5 (10 points) This homework is due for all sections by November 30th 11:59 pm following Thanksgiving break. Submit your answers by saving this page as "yourname" and submit your document as a file upload under the Homework 5 assignment on Canvas.

The Importance of Homework and Homework Research Homework is an important part of most school-aged children's daily routine. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (Campbell et al., 1996), over two-thirds of all 9-year-olds and three-quarters of all 13- and 17-year- olds reported doing some homework every day.

The initial analysis involved a naive logistic regression model, which sought to predict the probability of a team winning based on the day of the game and whether the team was ranked in the top 30. This model served as a baseline to understand the influence of game scheduling and team strength without accounting for inter-team variations and ...