- < Previous

Home > History Community Special Collections > Remembering COVID-19 Community Archive > Community Reflections > 21

Community Reflections

My life experience during the covid-19 pandemic.

Melissa Blanco Follow

Document Type

Class Assignment

Publication Date

Affiliation with sacred heart university.

Undergraduate, Class of 2024

My content explains what my life was like during the last seven months of the Covid-19 pandemic and how it affected my life both positively and negatively. It also explains what it was like when I graduated from High School and how I want the future generations to remember the Class of 2020.

Class assignment, Western Civilization (Dr. Marino).

Recommended Citation

Blanco, Melissa, "My Life Experience During the Covid-19 Pandemic" (2020). Community Reflections . 21. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/covid19-reflections/21

Creative Commons License

Since September 23, 2020

Included in

Higher Education Commons , Virus Diseases Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Expert Gallery

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- SelectedWorks Faculty Guidelines

- DigitalCommons@SHU: Nuts & Bolts, Policies & Procedures

- Sacred Heart University Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Law schools with the highest lsats.

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 11, 2024

Today NAIA, Tomorrow Title IX?

Lauren Camera April 9, 2024

Grad School Housing Options

Anayat Durrani April 9, 2024

How to Decide if an MBA Is Worth it

Sarah Wood March 27, 2024

What to Wear to a Graduation

LaMont Jones, Jr. March 27, 2024

FAFSA Delays Alarm Families, Colleges

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

Toward Semiconductor Gender Equity

Alexis McKittrick March 22, 2024

March Madness in the Classroom

Cole Claybourn March 21, 2024

20 Lower-Cost Online Private Colleges

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

COVID-19 reflections: the lessons learnt from the pandemic

by Alana Cullen , Lucy Lipscombe 03 February 2021

Imperial researchers reflect on the lessons they will take away from the pandemic.

Over the past 12 months the Imperial College London community has devoted an intense amount of time and research to COVID-19. Members of the community have been making fundamental scientific contributions to respond to coronavirus , from advising government policy to critical therapy research. A year on, Imperial researchers reflect on what lasting impact the pandemic has left on them.

Watch the clip above to hear the researchers’ insights.

A global contributor

Before I felt like just a person in the world, and now I feel like I’m one of those important people in the world! Dr Kai Hu

The first lesson is how fast- moving science is at this time. It is exciting to have been “on the forefront of vaccine discoveries” said Dr Anna Blakney, Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia, formally a Research Fellow in Imperial’s Department of Infection and Immunity . Imperial has also been key in finding optimal treatments for COVID-19, with clinical academics such as Anthony Gordon , Professor of Anaesthesia and Critical Care and Intensive Care consultant, caring for critically ill patients in intensive care units as well as leading clinical trials. Findings from these trials include the effective use of an arthritis drug in reducing mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The science doesn’t stop there. Outside of the lab Imperial academics have been informing UK government policy. Since the emergence of coronavirus the team from the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis and Jameel Institute (J-IDEA) at Imperial have been predicting the course of the pandemic and informing policy. The team have also been supporting the COVID-19 response in New York State. Furthermore, Imperial academics including Professor Charles Bangham and Professor Wendy Barclay continue to advise the government as part of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE).

In total the Imperial community has contributed nearly 2,000 key workers to essential services and research, from biomedical engineers developing rapid COVID-19 tests to health economists, generating a wealth of knowledge about the science behind the pandemic.

“This is the first time where I feel like what I have learnt is very useful” said Dr Kai Hu, Research Associate in the Department of Infectious Disease. “Before I felt like just a person in the world, and now I feel like I’m one of those important people in the world.” Dr Kai Hu is part of Professor Robin Shattock’s COVID-19 vaccine team, who continue to develop an RNA vaccine .

Watch our full COVID reflections video below, including researchers sharing their hopes for the future.

Collaboration is key

Another key lesson learnt is how much stronger we are when we work together. Vaccine development, production and delivery have all been achieved in under 12 months – an unprecedented timeframe for any disease prevention tool. This goes to show that collaborative efforts with the right funding will go a long way in biomedical science. “I can work even harder than I thought I could work because we can come together as a team” says Dr Paul McKay , Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Infectious Disease. “Science is a competitive endeavour, but a collaborative endeavour too.”

Something that will leave a lasting impression is the kindness of community, family and friends. Kindness at this time has been “unparalleled” said Sonia Saxena , Professor of Primary Care and General Practitioner. From providing free meals to NHS workers to educational materials for homeschooling there has been a feeling of togetherness, even when apart, throughout these difficult times. Going forward, we can bring these lessons into science, bringing more collaboration and kindness into the everyday.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Alana Cullen Communications Division

Contact details

Email: [email protected] Show all stories by this author

Lucy Lipscombe Communications Division

Strategy-staff-community , Vaccines , Infectious-diseases , Viruses , JIDEA , Coronavirus , Staff-development , COVIDWEF , Public-health See more tags

Leave a comment

Your comment may be published, displaying your name as you provide it, unless you request otherwise. Your contact details will never be published.

Latest news

News in brief

Superfast physics and a trio of fellows: news from imperial, vcc final 2024, 'living paint’ startup wins imperial’s top entrepreneurship prize, record-breaking victory, imperial wins university challenge for historic fifth time, most popular.

1 Record-breaking victory:

2 psychedelic treatment:, magic mushroom compound increases brain connectivity in people with depression, 3 blood markers:, long covid leaves telltale traces in the blood, 4 psychedelic experience:, advanced brain imaging study hints at how dmt alters perception of reality, latest comments, comment on scientists confirm the universe has no direction: the universe fake, comment on plastic-free vegan leather that dyes itself grown from bacteria: amazing and brilliant imperial’s proximity to the stella mccartney’s studio in white city shou…, comment on 200 years of charing cross hospital in ten pictures: 969-1976. i remember the old cross with great affection . so many great teachers, arthur makey, john…, latest tweets.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Every year, tuberculosis kills over a million people. Can a new vaccine turn the tide?

The history of Arizona’s Civil War-era abortion ban

Iran’s retaliatory attack against Israel, briefly explained

Life is hard. Can philosophy help?

Don’t sneer at white rural voters — or delude yourself about their politics

You probably shouldn’t panic about measles — yet

COVID-19: A year in reflections

As we mark a full year since the global pandemic upended all of our lives, we asked members of the UC community to share their reflections on how these past months have changed them, and what will stay with them about this unprecedented time in the years to come.

The picture that emerges is one of hardship, courage, gratitude and resilience. For many of us, the last 12 months have meant long hours and rising to meet new challenges with our teammates, families, communities and bubbles. We helped support others in their grief and were helped by others when grief came home to us. We found new strengths in loneliness and formed new practices and bonds to ward off despair.

Now, as we begin to see a little light at the end of the tunnel, here in their own voices, members of UC’s community look back on a year like no other.

On never falling off the treadmill

In the early days of 2020, two doctors, Daniel Uslan and Annabelle de St. Maurice , had already begun preparations with their colleagues in the command center at UCLA Health for the looming pandemic. As clinical chief of infectious diseases and co-chief infection prevention officer at UCLA Health, Dr. Uslan was working alongside Dr. de St. Maurice, pediatric infection control lead and co-chief infection prevention officer, nearly every waking moment. Their work spanned planning for patients, emergency preparedness, communications, and more.

“By the time California shut down non-essential businesses, I had already been working on COVID-19 for several weeks and my day-to-day life had already been thrown into chaos. In the early days I hoped, perhaps naively, that we would all hunker down for a few months and then the crisis would pass us by.”

As more information became available, that hope dimmed.

Dr. Tisha Wang put her entire life on hold when the pandemic hit — as the person overseeing pulmonary and critical care faculty and trainees for UCLA Health, she had no other option. It was clear, early on, that protecting health care workers from infection would be absolutely vital for saving the lives of the critically ill patients showing up at the hospital.

She describes those last three weeks of March 2020 as the worst three weeks of her career. Protecting the workforce, so they could protect the critically ill, was a heavy burden to carry. And as we know, that burden was carried for far longer than those three weeks (Dr. Wang speaks about the difficult experiences of saying goodbye to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, here ). Dr. Wang:

“We wondered if it was ever going to end — the deaths, the grieving, the suffering, the stress and anxiety compounded by the social isolation. In our minds, how could this possibly go on for months to years? I felt like I was constantly running on a treadmill and close to running out of steam. To my disbelief, after 9 months of running, the speed of the treadmill was turned up by 50 percent when Los Angeles became the epicenter of the pandemic. I had no choice but to keep running, but was I going to fall off?

“What have I learned? This is actually a team-based marathon. I was never going to fall off of that treadmill. Someone was going to come along and tag me out and let me breathe and rest for a moment. And as soon as I got some water and air, I was going to jump back on and do the same for them.”

Now there is time, and hope, we can address this situation better in the future. Dr. de St. Maurice has begun to reflect:

“The pandemic has taught us many lessons about preparedness and health equity, among other things. What can we do better in the future to prevent pandemics like this from occurring? What modifications have we made in our lives as a result of the pandemic that are positive and how can we continue these in the future? What health care inequities have intensified as a result of the pandemic and how can we work to improve those inequities?

“In the past many physicians and health care workers would work when they weren’t feeling well and I think that will change going forward.”

On living in a bubble year

Steven Pease has been working part-time at home in his capacity in IT asset management, in a bubble with his wife, their children and her parents, one of whom, her father, passed just before turning 100 in October. Planning the funeral and sharing mourning in the pandemic was challenging, an experience shared by many. Still, Pease felt gratitude for his connection to his family.

“To be certain, some of this will go down in our collective memories as the worst of times. That said, to have been locked up in our little ‘bubble’ together; forced to navigate together uncertain and new waters, but to get to do so with someone I love was in some ways very, very special. I believe that someday I'll look back on this time and see it as some of the best.”

Valerie Simmermaker has been working remotely for the UCPath Center near Riverside and finding silver linings in the pandemic as a single mom.

“I would say for us the stay at home order — working and schooling from home has ultimately been really good for us. I have always been a single parent and my children were used to coming home from school alone, and helping with chores and cooking, sometimes even doing grocery shopping while I worked. This has allowed us to really bond, I am finally able to help them with school work and we eat dinner before 7 p.m., we have really gotten close during this time together.”

Darlene Alvarez at the UC Retirement Administration Service Center (RASC) has had similar experiences with her children, trying to juggle work and keep her children motivated and focused on their school work. One thing that has helped is carving out 30 minutes a day to read for pleasure or dance along to music videos (current favorite is “Levitating” by Dua Lipa featuring DaBaby)!

“Another way we cope with challenges is through creative expression. For instance, we’ve made parols (Filipino Christmas ornamental lanterns) and foam mosaic art. We’re also making more homemade dishes, like arepas (Venezuelan cornmeal cakes).”

Helping to guide our kids through the pandemic hasn’t been easy. Jennifer Mushinskie , a senior communications officer/interim operations liaison at the UCPath Center in Riverside and her son grappled with the loss of high school experiences you can’t get back, while still dealing with the social anxieties that are rampant in the teen years.

“It's heartbreaking to see a screen with 30 kids and only the teacher is on video. The kids aren't required to be on camera, per the district, so the teachers are frustrated, and the kids won't go on camera. I have tried to get him on video but he won’t – saying “Mom, that’s embarrassing if I go on and no one else does.

“Waiting has been exhausting on the kids mentally and physically. It's been a rough road. Our kids witnessed area businesses and mall parking lots filled with cars and shoppers, but they weren’t allowed to play in a high school football game or another type of school sport. We watched the Superbowl, with fans in the stadium, but our children in California weren’t in school or on the field. My son was so frustrated with this and it broke my heart. I’m grateful things are starting to get better.”

For Annette Dwyer , an accounts receivable associate at UCPath in Riverside, the pandemic brought her husband to her, then took him away, before returning him again.

“I married my Welsh boyfriend in July 2019, and had barely started the immigration process for my husband in January 2020, which was expected to take 12-18 months. We planned to pass the time with short visits. He was scheduled to visit in March 2020 to spend time with us during spring break, and for us to have a mini-honeymoon of sorts. That all changed when the executive order was issued on international travel to the U.S. (He barely made it on the plane and through customs thanks to a photocopy of my passport.) He was locked down with us in March, ‘getting stuck’ here for almost four months. We were devastated when my husband was called back to work and had to return to the U.K. in July. We did not know when we would get to see him again and hoped his immigration interview would be soon. (At that point, we were waiting to hear from the embassy.) He ended up receiving his interview in August and his immigrant visa was approved within an unheard of seven-month timeline. He immigrated here at the very end of August.”

On finding strength in community/new families

Ricardo Vela , who leads Spanish language news and outreach for UC’s Agriculture and Natural Resources division, has seen the pandemic turn his co-workers into family, the result of the intense bonds developed as they helped each other through the crisis. Several of his family members fell seriously ill with COVID-19, but recovered. Some of his colleagues were not so fortunate, and he and his team struggled through those moments together.

“As a team, during the pandemic, we have grown closer together. Even when we have not been in the same place for over a year, we pushed each other to think outside the box to accomplish our work's goals. We did better than ever before.

“But despite our success we fell at times into depression and anxiety, for days. When one of my staffers lost her father, we fell into despair, wondering "who is next?" We saw how personal the pandemic could get. It stopped being another headline and became real and painful.

“We shared tears of despair, impotence, and at times of joy! As a team, we pulled it together, we stopped being co-workers, and we became a family.

“A year after, I can say we are stronger, resilient. We learned that distance is only a click away, that we can express that love in many ways. We are ready to face the ‘new normal.’”

Azure Otani , a second-year business administration major at UC Riverside, felt “scared, lonely and claustrophobic” when the pandemic began. To cope, she pushed herself to become more (virtually) involved on campus — and in doing so, found a new sense of community. Today she holds officer positions in several student groups and has even mentored freshmen via text message.

“When the virus basically shut down the world at the snap of a finger, I thought I wasn’t going to be able to accomplish anything. Instead, I’ve been able to teach and learn from other people, and help bring meaning to their lives, just like they’ve brought to mine. I’ve never met any of them in person, but I know that many of them would have my back. I feel a true sense of community and am grateful for what I’ve learned in the process — what I value, how I like to work and the importance of taking time to reflect.

“I will forever be more conscious of the people around me — whether that is recognizing that I don’t know what others are going through or keeping my mask on when I’m sick. Life is extremely short and we don’t know when we’re going to lose everything we have. I know how important it is to spend my time with loved ones and reach out to give back as much as I can.”

On embracing change — and science

Heather Buschman , Ph.D., is assistant director of Communications and Media Relations at UC San Diego Health and an instructor at UC San Diego Extension. Since the start of the pandemic, her team has shared scientists’ stories and fact-based public information. She also volunteered at a vaccination site. From her unique perspective, Buschman has seen the magnitude of the pandemic, and the remarkable strides we’ve made.

“I was in my office when I heard that schools were closing. I ran to tell a coworker and choked with emotion over the gravity of the situation. For more than a month, I’d been serving shifts as a public information officer in our incident command center, which activated to manage coronavirus patient care and protect health care workers. But until then the pandemic hadn’t really affected my family.

“Until they arrived at UC San Diego Health, I never believed we’d have COVID-19 vaccines by early 2021 — and yet here we are, administering multiple, highly effective vaccines since late 2020. I’m blown away by what the scientific community has accomplished with so many people working together, focused on a single problem, with appropriate funding. I’m proud to tell scientists’ stories and play a small part in distributing vaccines to our community. It’s truly historic.”

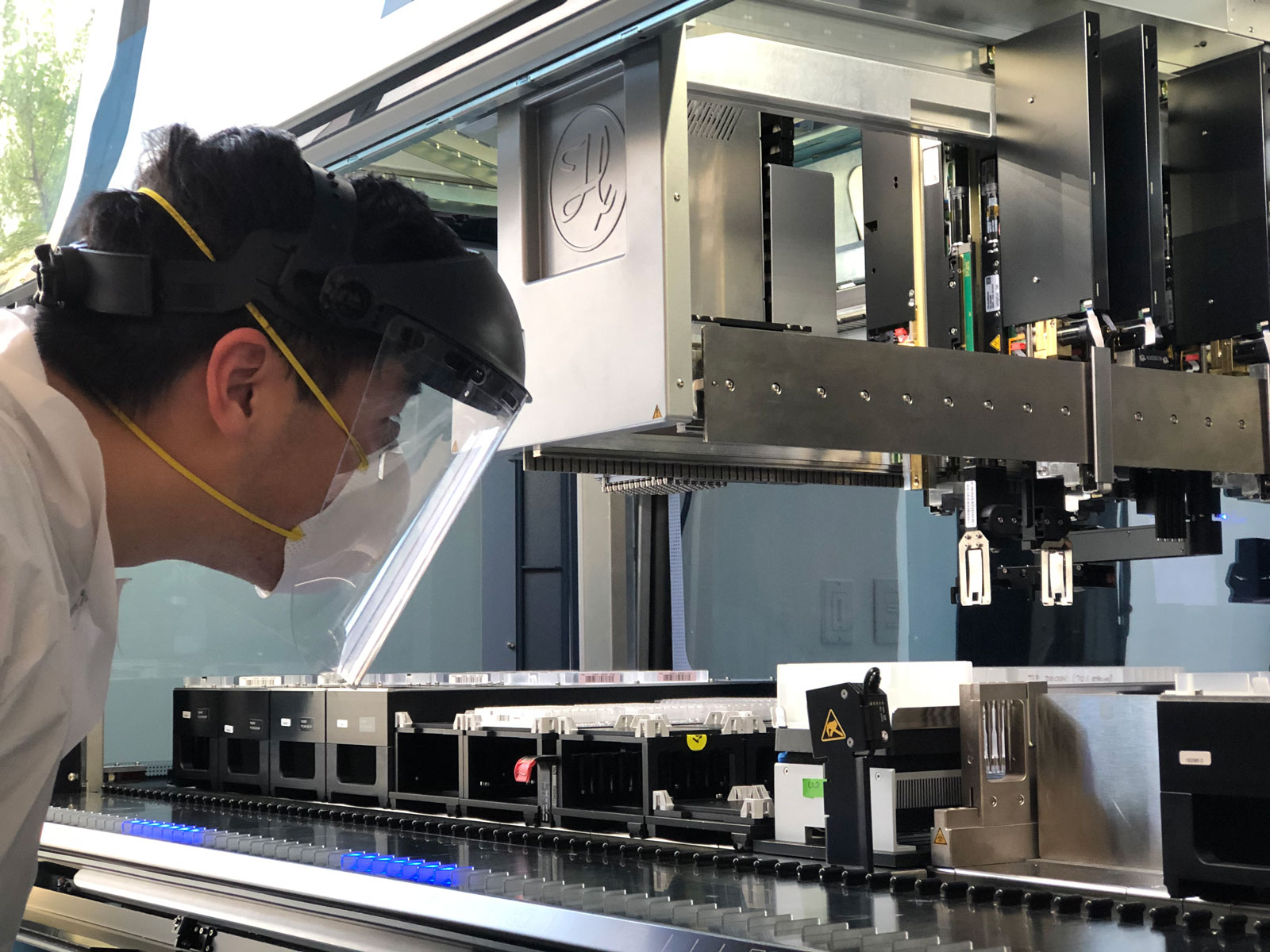

Connor Tsuchida is a graduate student in Jennifer Doudna’s lab at UC Berkeley, working on research related to the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR. When the pandemic hit, he and his colleagues at the Innovative Genomics Institute put aside their regular research to stand up a COVID rapid-results testing lab to meet the urgent need for COVID diagnoses. The transition from one new frontier of science to another wasn’t easy.

“For a [disease] testing lab, the concepts are not the same as genetic engineering, but the skills and technology you use is similar. We knew some of the techniques and protocols of diagnostic testing, and we were familiar with the equipment. That gave us a leg up so we weren’t starting from zero.

“One of the best things has been the opportunity to work with professionals from other fields: volunteer physicians from UC Berkeley’s student health center, people from public health — it’s a multi-disciplinary, team endeavor.

“For me, it’s also been a lesson in setting something up and then being okay with transitioning it to other people. There’s a controlling nature with research that if you are going to do it right, you need to do it yourself. It’s a good experience to hand off what you helped establish and see it take on a life of its own.”

Another bright spot: Tsuchida’s work in biomedical research now seems more vital than ever — and not only to those in the field.

There was so much work done in science and research before the pandemic that we absolutely were able to build upon when developing therapies and vaccines for COVID-19. I hope this will bring home the importance of that research and encourage everyone to support putting money into science.

Teresa Andrews, M.S., is an education and outreach specialist at the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at UC Davis, focusing on the workplace health and safety of farmworkers. Before the pandemic, Andrews and her team hosted in-person trainings for farmworkers and employers across California. COVID-19 forced them to reinvent their approach while maintaining connections with agricultural communities.

“We adapted our interactive activities to a virtual platform and started learning all we could about what farmworkers needed to know about COVID-19 and how employers could reduce workplace infections. Our goal was to be a resource, alleviate fears and empower workers and employers with the knowledge they needed to operate within this new reality.

“Since then, we’ve mastered the use of technology to fill the gap and stay connected. We offer more presentations and workshops than ever before and are reaching more people throughout our region, connecting with workers wherever they are. It brings me satisfaction to counter fears with science; to help explain concepts that can seem abstract to people — what a virus is, how your body responds, and what you can do to reduce the risk of infection — in language that’s easy to understand.”

Paul Kasemsap , an international student from Thailand, stayed close to campus partially to care for the plants he studies. But he also found himself drawn to the local Davis community, volunteering with the food bank to bring groceries to those most at-risk for COVID-19, so they didn’t have to risk trips to the store.

“After this is over, I hope we continue to take care of and check in with each other. I had indeed been taking in-person interactions and small talk for granted. But the pandemic showed me how powerful a role social support plays in our life. I hope we continue to tell our loved ones how much we love them and appreciate their support. Don't wait until the next pandemic!”

Aaron Zachmeier , UCSC Online Education instructional designer, helped hundreds of faculty put their classes online virtually overnight.

“Before the pandemic, the unit I'm in, Online Education, worked with a relatively small number of faculty on online and hybrid courses. We were kind of a boutique unit. When the shut-down happened, we started working with people all over campus.

“My colleagues and I created all sorts of resources to help with the transition to remote teaching and learning and remote working: workshops, self-paced courses, videos, text tutorials, checklists, infographics.

“We had a chat/discussion space that we opened up to all staff and faculty for the pandemic, and it has now become a lively place that spans departments and administrative units. People ask questions and have conversations about technology, teaching, and policy. Those conversations will continue.

“All of those people who started working together to facilitate the transition to remote are still talking regularly. They'll keep talking. That's a wonderful change.”

On improvising

Frida Hernandez is a Class of 2020 UC Berkeley grad. As the first in her family to graduate from college, she was looking forward to celebrating her big day with her family. While a virtual graduation wasn’t what she had hoped for, she was still able to share her accomplishments alongside her family at home in San Diego.

“Graduating in the middle of a pandemic as a first-gen student was tough because I felt the pressure to have my next steps all figured out to make my family proud. I have two younger siblings who are currently in high school, so I wanted to set a good example for them. Luckily, I was able to find a job in my field and I am so grateful I did. Landing my first full-time job in the middle of a pandemic gave me a new perspective on life because I was thankful to find some stability amidst all the chaos. I’ve really enjoyed spending time with my family (in my household) during this time. I moved back in with them after graduation and I’m grateful we have each other during these difficult times.

“As we begin to resume ‘normal’ life, I will live my life with more intention and gratitude. I hope to make up for all the celebrations I missed out on during this past year, such as my college graduation and numerous birthdays.”

In normal times, UC Santa Barbara’s Saameh Solaimani works as an early education specialist at the campus child care center. When the pandemic forced it to close, Solaimani quickly found new ways to help UC families by starting a website, www.ourchildrenscenter.org , that provided a high-quality resource for early child educators and those with young children.

“To see the pivot that so many teachers have made to ensure the healthy development of their students and learning communities, from pre-school all the way through higher-ed, has been incredible. These circumstances have reaffirmed what I knew to be true: That we, in the field of education, got into this work with hope for a better future and we are relentless with that hope, which is what keeps us going.”

Glenn Beltz is a mechanical engineering professor and associate dean at UC Santa Barbara. When the pandemic first hit, he saw first hand that family circumstances made online learning difficult for many students — there were no simple solutions. He and his academic advising team rose to the challenge by providing individual guidance to help as many students navigate the situation as possible. The Academic Senate’s decision at UC Santa Barbara to allow flexibility with pass/no pass grading was a huge help for students, allowing courses to count toward their degree requirements.

His own family faced different, but equally challenging circumstance with online learning.

“I am a parent so the kid aspect strikes a nerve. It has been rough. My wife and I have 2 kids, a daughter in 10th grade and a son in 4th grade. It has been particularly difficult with my son, who is autistic. Every autistic kid is different, but there is no way you could get my son to sit in front of a Zoom session for hours on end. No way at all. I fear that much of this past year will be a lost year in terms of his education. Fortunately, in January ’21, his elementary school worked out a protocol to be able to take him and a few other special-needs kids back. That has been a godsend.”

But he expects to take some positives forward.

“There are many aspects of teaching that I hope will remain in the long term. I think it’s awesome that students can pull a set of notes online from whatever I taught on a given day or even pull a recording of the lecture. Sure, that kind of stuff occurred in former times, but it was not widespread. I don’t think I will ever give a paper-based, sit-down exam again. I like being able to administer and grade exams online via various tools that are available.”

Top photo: One of Frida Hernandez’s journals from the pandemic.

Keep reading

Top UC Davis graduate earns provisional patent, cuddles…

Neeraj Senthil makes the extraordinary look easy.

Food truck offers free meals to students in need

The new AggieEats food truck is believed to be the first and only one in the nation to serve free meals on a college campus.

- Our Mission

- Strategic Plan

- Institute History

- Annual Reviews

- Keeping Up With Kellogg ENews

- Kellogg 40th Anniversary

- Staff by Name

- Staff by Area

- Human Development

- The Ford Program

- K-12 Resources

- Ford Family Notre Dame Award

- Outstanding Doctoral Student Contributions

- Distinguished Dissertation on Democracy and Human Development

- Undergraduate Mentoring Award

- Considine Award

- Bartell Prize for Undergraduate Research

- The Notre Dame Prize

- Employment Opportunities

The Kellogg Institute for International Studies, part of the University of Notre Dame’s new Keough School of Global Affairs, is an interdisciplinary community of scholars that promotes research, provides educational opportunities, and builds linkages related to democracy and human development.

Our welcoming intellectual community helps foster relationships among faculty, graduate students, undergraduate students, and visitors that promote scholarly conversation, further research ideas and insights, and build connections that are often sustained beyond Notre Dame.

- Kellogg Faculty

- Visiting Fellows

- Distinguished Research Affiliates

- Advisory Board

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- Faculty Committee

- Institute Staff

- Engage with Alumni

- International Scholars

A map of the involvement of Kellogg Institute people and programs in countries around the world.

- Democracy Initiative

- Policy and Practice Labs

- Research Clusters

- Varieties of Democracy Project

- Kellogg Institute Book Series

- Kellogg Institute Working Papers

- Conference Publications

- Faculty Research Highlights

- Kellogg Funded Faculty Research

- Visiting Fellow Research

- Visiting Fellows News and Spotlights

- Work in Progress Series

- Working Groups

- Kellogg Funded Doctoral Research

- Doctoral Research Highlights

- Graduate Student News

- Comparative Politics Workshop

- Kellogg Int'l Scholars Program

- Int'l Development Studies Minor

- Kellogg/Kroc Research Grants

- Experiencing the World Fellowships

KELLOGG COMMONS The Commons is flexible space in the Hesburgh Center for our Kellogg community to study and gather in an informal setting. Open M-F, 8am to midnight. To reserve meeting rooms or for more info: 574.631.3434.

- Faculty Grant Opportunities

- Working Paper Series

- Kellogg Event Proposal Form

- Visiting Fellowships

- Postdoctoral Visiting Fellowships

- Fulbright Chair

- Other Visitor Opportunities

- Doctoral Student Affiliates

- PhD Fellowships

- Dissertation Year Fellowship

- Summer Dissertation Fellowship

- Graduate Research Grants

- Professionalization Grants

- Conference Travel Grants

- Overview Page

- Kellogg Developing Researchers Program

- Human Development Conference

- Pre-Experiencing the World Fellowship Program

- Organizations

- Kellogg/Kroc Undergraduate Research Grants

- Postgraduate Opportunities

News & Features Learn what exciting developments are happening at the Kellogg Institute. Check our latest news often to see interesting updates and stories as they develop.

Global Stage Podcasts

No matter the hour, across my window, I see a group of military soldiers outside. It has become a morning routine to stand there, coffee in hand, and read the forever-changing news to which I’ve become addicted to. Today, as I read government instructions forbidding burials and limiting funerals to only close family members, I cannot help but think about when my father passed away. He spent a few days in intensive care, and we were able to mourn him, give him a proper funeral, and choose when and how to continue with our lives as best as we could… and it was the hardest and most painful thing I’ve ever done. I cannot imagine the feeling of those being directly affected by COVID-19 and not only its consequences (as this part has already become universal). More...

Follow up on COVID-19 in Bolivia: A Small Fraction of The Struggle - September 16, 2020 Four months after schools moved to remote learning, on July 9th, the Minister of Education finally presented rules for online instruction, as the government continued with ongoing programs to train teachers and improve access to and quality of the internet. However, on the morning of Sunday August 2nd, the Minister of the Presidency announced the closure of the school year as of July 31st—four months earlier than usual. All students from all levels automatically passed. The government would continue to pay public schools teachers, and private schools could decide whether or not parents wanted to continue online instruction. No one saw this coming, especially not me. More...

As of yesterday, April 4th, the official count is that there are 1,890 confirmed cases, 634 recoveries, and 79 deaths in Mexico. The real number, however, is likely to be much bigger because my country lacks the resources to detect the virus and keep track of the cases. Like the rest of the world, thousands, if not millions, are being affected by this crisis. The totality of the trickle-down effects of COVID-19 is yet to be seen, but thousands of workers have lost their jobs or part of their wages. Government authorities have failed to impose strict measures to control the virus, and many have condemned our president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), for it. In his daily press briefings, he has encouraged hugging, blamed conservatives for purposely wanting our economy to fail, and claimed that we are ready to confront the crisis. The reality is much different. More...

In early February, during one of my Political Science classes, my professor asked the class to go around the room and share its thoughts on COVID-19. When my turn to share came, I answered honestly that I am concerned about the Sub-Saharan African region should the virus spread across the world. The reason behind my deep concern was because the region does not have the same level of health care facilities and resources as western countries and so the spread of the virus could be fatal. I was particularly concerned about my country, Botswana, because it is among the countries that have the highest rates of HIV/AIDS prevalence in the World. From what I had read at the time, people with underlying medical conditions were at a higher risk of getting seriously ill if they get the virus. More...

Facing the threats posed by the coronavirus pandemic is not easy, nor is it easy to conduct a general election – especially a free and fair one in an underdeveloped country. How about doing both simultaneously? The Dominican Republic is currently undergoing this challenge, with elections scheduled for July 5. The coronavirus pandemic was declared a national emergency on March 19. There are currently 16,531 active cases in the country, 9,266 recovered ones, and 488 deaths. Fortunately, our health system has not collapsed – yet, and there seems to be moderate control over the virus’s transmission rate compared to other countries in the region, such as Ecuador. Nonetheless, as the country comes close to holding general elections, the feasibility of doing so while still respecting the well-being of all Dominican citizens is in question. More...

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Reflections On Coronavirus A Year In

Madeline K. Sofia

Rebecca Ramirez

Emily Kwong

An elderly couple wearing face masks walks in Madrid on April 30, 2020 during a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 disease. Gabriel Bouys/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

An elderly couple wearing face masks walks in Madrid on April 30, 2020 during a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 disease.

It's been about a year since the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic. The world has learned a lot in that time — about how the virus spreads, who is at heightened risk and how the disease progresses. Today, Maddie walks us through some of these big lessons.

Follow NPR's continued coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

Helpful links from the episode:

- How To Protect Yourself From Aerosol Transmission

- Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity

- The Key To Coronavirus Testing Is Community

Reach the show by emailing [email protected] .

This episode was produced by Rebecca Ramirez, edited by Gisele Grayson, and fact-checked by Rasha Aridi. Stacey Abbott was the audio engineer. Special thanks to Ariela Zebede and Leah Donella.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A reflection on health and disease amid COVID‐19 pandemic

Si‐woon park.

1 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, International St. Mary's Hospital, Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon South Korea

Associated Data

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is persisting for more than a year and it's still far from being controlled. It is making a big impact not only on physical illness but also on mental and social aspects. In this situation, we need to reflect on current medical society's view of disease and health. The dominant paradigm in contemporary medicine is the reductionist view of disease and the biomedical model of health. As a result, the healthcare system seems to be more focused on virus eradication than on patient care. We need to look back on this position in view of humanities and ethics and broaden our perspective to an ecological view of disease and the sociomedical model of health. The quarantine and health care policy also needs to be re‐built with more focus on patient care.

1. INTRODUCTION

It's been a year and a half since coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic began. This new infectious disease, which had spread at a frightening rate in the early days, became a testing tool for each country's quarantine policy. Unlike the past epidemics, new policies—mass testing, tracing, and isolation—emerged owing to the advancement of information and technology. Some countries have been relatively successful in controlling the number of confirmed cases. However, we are still incompetent in preventing the spread of infectious diseases and confronting many socioeconomic problems over time. The vaccines developed with the greatest hope, although they showed quite good preventive efficacy, are still limited in preventing all the variants of the virus. We are still far from controlling the pandemic.

The current situation leads us to look back on what it means to live a healthy life, and what the healthcare system is for. In this article, I intended to take a look at the problems that emerged during the COVID‐19 pandemic and discuss the meaning of disease, health, and health care in terms of medical epistemology and ethics.

2. WHAT IS A DISEASE?

At the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the South Korean Government recommended screening polymerase chain reaction tests only for those who travelled abroad in certain areas and had a fever and respiratory symptoms. In South Korea, the relationship between the government and the medical association was not so cooperative because the government was planning healthcare policies that the medical association disagreed with. In the meantime, a doctor sent a suspected case to the public health centre for the COVID‐19 test. But the public health centre official refused testing because the case did not meet the indications for the test. 1 Later, the case was confirmed as positive, and the medical association criticized the bureaucracy of the government for its lack of medical expertise. The public and the opposition party also joined the criticism. And the government, being conscious of the people's vote, greatly expanded the indications for the test. Infection control became a political issue. As a result, the subjects to the test included asymptomatic individuals, and anybody who wanted to be tested could get it. The public's excessive fear of the virus also played a role in expanding test indications. Besides, the advanced IT situation in Korea made it technically possible. As the South Korean government's quarantine seemed to go relatively successful in limiting the number of confirmed cases, other countries began to implement similar methods of quarantine as South Korea did. The US Government at that time also faced criticism for having fewer COVID‐19 tests than South Korea, and more aggressive testing was launched to find out more confirmed cases.

As a result of this mass testing policy that has never been done before, the number of COVID‐19 confirmed cases increased drastically. On the contrary, the case fatality rate of COVID‐19 showed a tendency to decrease. The case fatality rate of COVID‐19 was reported to be lower than that of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). 1 , 2 But if the screening test had been restricted to symptomatic cases, the case fatality rate may be higher than reported. The positive effect of this mass testing policy is that it can provide better knowledge regarding the infectivity of the virus. This information is important for establishing effective quarantine policies. However, there are also negative effects. First, the increase in the number of confirmed cases is being reported in the media every day and spreads public fear of the disease. Second, medical resources can be depleted as asymptomatic cases are also included in the management. As a result, patients with symptoms are at risk of being excluded from medical treatment.

An infectious disease develops from the interaction between agent, host, and environment, which is known as the epidemiological triad. Social distancing to suppress the spread of infectious diseases is the right measure in terms of controlling the environment of easy transmission. On the contrary, putting an infected host in an isolated environment with other patients is like leaving the host in a more risky, immune‐deteriorating environment. Even though the host had no symptoms in the first place, later he or she might develop symptoms while being isolated in a poor environment, and the disease could get worse.

Here comes a fundamental question about a disease. Is a test‐positive case without symptoms a patient? Can we say that those who are test positive are having a disease?

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, “disease” is defined as “any harmful deviation from the normal structural or functional state of an organism, generally associated with certain signs and symptoms and differing in nature from physical injury.” As seen in this definition, a disease is generally a phenomenon that involves symptoms and signs. In fact, the disease begins with symptoms that the patient complains of, and then the diagnostic process follows. And the goal of treatment is a relief of symptoms.

Since ancient times, a disease had been defined according to symptoms that the patient complains of. Medical theories arise in the process of explaining and treating symptoms. In ancient Greek medicine, represented by Hippocrates, the disease was seen as a disharmony resulted from fluid dysregulation, 3 and health care was provided based on the holistic care model. 4 In oriental medicine, the symptom was the basic unit and key term in medical theory. 5 The human body was seen as a microcosmos and harmony was emphasized for healing. After the modern era, the invention of microscopes and the discovery of microorganisms have introduced the pathology of diseases. Disease entities have begun to be defined according to pathologic findings. Descartes regarded the world as a giant clockwork machine and thought that one would have to disassemble it and look at the parts to understand it. This mechanistic view was applied to an understanding of the human body, and the reductionist view became the dominant paradigm in medicine. 6

Reductionism in medicine affected the diagnosis, treatment, and preventive approach of disease. The reductionist view is to diagnose a disease based on pathology, assume that the pathologic finding has a causal relationship with the symptoms, seek for a treatment to get rid of pathologic findings, and establish prevention strategies focused on eradicating observable pathology. Consequently, it became ambiguous whether the purpose of health care is an improvement of patient's condition or restoration of pathology. In the same way, it is believed that the detection of pathogens is more essential in the diagnosis of infectious disease than a clinical presentation of patients. Furthermore, by seeing infectious disease as evolutionary warfare between mankind and microorganism, strategies to eradicate microorganisms are considered to be more important than patient care.

The reductionist view, of course, has contributed a lot to the advancement of medicine, but because of its limitations, system theory has attracted attention as an alternative. 7 In contrast to the microscopic view of reductionism, system theory understands the world as a system and provides a macroscopic ecological perspective. The ecological perspective considers disease as disharmony in the entire system and attempts a multidimensional approach in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease (Table 1 ).

Reductionist versus ecological view of infectious disease

In fact, COVID‐19 was initiated by the destruction of ecological balance. Global instability can lead to an increase in new epidemics. Therefore, to properly cope with emerging infectious diseases, we need to integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines and approach problems from a system perspective and ecological context. 8 The microscopic approach of molecular biology is important for understanding the origin and pathology of pathogens. Whereas, understanding the ecology of infectious diseases and agent–host interactions provides key knowledge in regard to transmission and manifestations of diseases, and thus help establish successful disease control strategies. 9 Recognizing that human health and global bio‐system are inextricably linked, efforts should be made to understand infectious diseases and provide solutions from a more ecological perspective. 10 Concentrated too much on reductionist view, we may lose the balanced view. We may fall into the fallacy of thinking newly emerging infectious diseases as problems to be solved solely by biological means rather than seeking more sustainable solutions for coexistence.

A disease entity is neither born nor discovered but defined. Pathologic finding per se is not a disease. Defining disease entities not only affects an individual's health status, but also affects the whole society in both ethical and economic aspects. 11 Now in this pandemic, we are experiencing the influence of disease control strategy, which is based on the reductionist view, on the whole society. It does not seem appropriate to set the number of confirmed cases as the goal of infection control without defining the disease entity. We should first define the disease entity we fight against and clarify who needs medical care.

3. WHAT IS HEALTH?

WHO defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well‐being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This WHO definition has been criticized for the word “complete,” which is usually unachievable, and its disease‐centeredness. As an alternative, the definition of health as “the ability to adapt and self‐manage” has been proposed. 12 It makes more sense to define health as “a dynamic state of wellbeing characterized by a physical, mental and social potential, which satisfies the demands of a life commensurate with age, culture, and personal responsibility.” 13

Aside from the definition of health, WHO published and distributed “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).” 14 ICF takes a more comprehensive approach to health. ICF sees health state in a functional point of view, defines domains of health as body structure, body function, activity, and participation, and identifies personal and environmental factors as modifiers. According to the holistic and social perspective of ICF, health is not just a matter of presence or absence of disease but encompasses the way how we live. This perspective enables us to seek ways of minimizing the negative impact of disease and impairment on activity and participation.

The dominant paradigm of current medical society is the biomedical model. The biomedical model sees health as a disease‐free or pathogen‐free state. Its perspective is restricted to body organ or body system level and focuses only on body structure and function. It often neglects social and system factors that affect health status and sees health problems only at the biological level of an individual. 11 To complement the limitations of the biomedical model, a sociologic perspective is required. In the sociomedical model, one can be said to be healthy if he or she can adapt to life situations even with the disease. The sociomedical model extends the concept of health to the level of whole person and society, and focuses on activity and participation (Table 2 ).

Biomedical versus sociomedical model of health

Absurdly, as the pandemic persists, the quarantine policies limit activities and restrict the participation of individuals in everyday life, even when the virus itself that caused the pandemic does not cause serious symptoms or harm human body. From the health perspective of ICF, healthy lives are being threatened by activity limitations and participation restrictions in the absence of disease or impairment.

As new epidemics such as SARS and MERS emerged since the beginning of the 21st century, principles of quarantine ethics have been established. Upshur 15 suggested the following four principles: harm, proportionality, reciprocity, and transparency. Aside from these ethical principles, we need to ensure whether quarantine policies are effective. For proportionality, we need to estimate whether the potential benefits of quarantine surpass the negative effects resulted from it. Benefits of isolating asymptomatic or mild cases should be weighed against side effects such as stigma. Besides, we should also keep in mind that a high‐intensity quarantine policy can enhance public fear and anxiety, induce stigmatization, and provoke competition for limited resources. It may result in deepened economic polarization and a divided society. 16 Policymakers tend to take position of people who are not infected yet. To protect uninfected, they isolate and confine infected ones. Such a quarantine policy is not different from oppressing the minority for the benefit of the majority. Infectious disease usually affects more in poor people and poor countries. Policymakers should not ignore the principle of justice when making quarantine policy. 17

In South Korea, confirmed cases with no or mild symptoms are forced to be isolated in designated treatment centres. In March 2021, the media reported a case who committed suicide while being isolated in a designated centre. 2 According to press reports, the woman had been accused for violating self‐isolation after receiving test negative result a few weeks ago. She contacted an infected one again and took her second test to get positive result, so she was sent to a designated treatment centre for isolation. The police assumed that she was suffering from being isolated alone in a room. The coronavirus did not cause serious physical symptoms to this woman, but isolation under the quarantine policy caused very serious negative consequence.

This tragic incident was reported in the media and called public attention, but in fact, there are many other unknown cases that are experiencing mental illness during COVID‐19 pandemic. It is important to ensure that involuntary hospitalization be administered in an appropriate and respectful manner to protect the interests of both patients and the community. Special attention must be paid to prevent abuse of forced isolation just to alleviate public anxiety. 18