- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Quality improvement in healthcare: the need for valid, reliable and efficient methods and indicators.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Mohaimenul Islam, Yu-Chuan (Jack) Li, Quality improvement in healthcare: the need for valid, reliable and efficient methods and indicators, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 31, Issue 7, August 2019, Pages 495–496, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzz077

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Quality of care and patient’s safety are now recognized globally as a healthcare priority. While adverse events (AEs) are a serious issue related to the patient’s safety, concern has been raised on the quality of care provided globally. It is reported that AEs reckon additional 13–16% costs alone due to only prolonged hospital stay. The annual cost of prolonging hospital stay because of AEs is ~£2 billion in the UK [ 1 ]. Moreover, other issues like pain and suffering, loss of independence and productivity of patients or costs of litigation and settlement of medical negligence claims are often ignored while calculating the total economic burden of AEs. An increased number of AEs always have detrimental effects on both patients and healthcare providers including physical and mental harm, reducing credibility of the healthcare system. It is therefore important to identify and measure AEs for prioritizing problems to work on and making sophisticated ideas for better patient care as they generate substantial burden to patients and healthcare providers [ 2 ]. Although there is no gold standard for measuring AEs, a significant number of studies used the Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS) approach as a standard methodology for measuring AEs [ 3 ]. Trigger tools like the global trigger tool (GTT) (introduced by the institute for healthcare improvement) have been developed to identify and measure the AEs. It is an easy and less labor intensive two-stage method of retrospectively manual review of the patient’s chart. Firstly, two nurses individually screen patients’ reports for specific triggers and ascertain AEs regarding these triggers before making any decision. Secondly, physicians verify them based on the standard definition [ 4 ].

A study based on the local analysis at hospital reported that the GTT method had both high sensitivity and high specificity than other methodologies like HMPS [ 5 ]. Moreover, the GTT method correctly detected most of the AEs that were missed out by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Patients Safety Indicators. Mevik et al . [ 6 ] evaluated a modified GTT method with a manual review of automatically triggered records to measure AEs using the original GTT method as a gold standard. However, the modified GTT method was more reliable and efficient when it came to monitoring and accurately identifying AEs. While comparing time to identify AEs, modified GTT took less time than original GTT (a total of 23 h to complete the manual review of 658 automatic triggered records with modified GTT compared to 411 h of review of 1233 records with the original GTT) but both of the methods identified same amount AEs (35 AEs) per 1000 patient’s days. Modified GTT would be the right choice for the higher sample size as it provides an effective alternative to valid, efficient and time-consuming approaches to identify and monitor AEs. In the future, an automatic trigger-identifying system with electronic health records might enhance the utility and assess triggers in real time to lessen the risk of AEs.

The health of pregnant women and child still remains a serious public health issue. Despite comprehensive efforts and investments in the healthcare sector; maternal and child mortality is unacceptably high [ 7 ]. Antenatal care (ANC) is of paramount importance for ensuring optimal care of pregnant women and reducing the risk of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Quality of care during pregnancy and childbirth can help to reduce pregnancy complications and improve the survivals and health of babies. According to the updated recommendation by WHO, women need first ANC visit within the first trimester and an additional seven visits are recommended [ 8 ]. However, raised awareness, trained healthcare workers, strong national information and surveillance systems are needed for proper monitoring and timely and respectful care.

Morón-Duarte et al . [ 9 ] conducted a systematic review to describe indicators used for the assessment of ANC quality globally under the WHO framework. A total of 86 original studies were included, which described the ANC model and ANC quality indicators such as the use of services, clinical or laboratory diagnostic procedure and educational and prophylactic intervention. The quality of the included studies was evaluated according to the ‘Checklist for Measuring Quality’ proposed by Downs and Black [ 10 ]. A highly diverse and region-specific description of indicators was observed while relevance and use depend on the country-specific context. However, 8.7% of the articles reported healthy eating counseling and 52.2% iron and folic acid supplementation on the basis of updated WHO recommendation. The evaluation indicators on maternal and fetal interventions were syphilis testing (55.1%), HIV testing (47.8%), gestational diabetes mellitus screening (40.6%) and ultrasound (27.5%). Essential ANC activity assessment ranged from 26.1% report of fetal heart sound, 50.7% of maternal weight and 63.8% of blood pressure. Concern has been raised due to the quality assessment of ANC content especially in the utilization of services across countries. It is important to use health indicators based on the international guidelines but the appropriateness of suggested indicators and the construction of structured and standardized indices are necessary to be implemented in the different countries allowing international comparability and monitoring.

In summary, various trigger tools have been implemented and evaluated to improve drug therapy assessment and monitoring in hospitalized patients, nutrition support practice and tertiary care hospitals, but these tools need to be validated in varied patients’ populations. Moreover, improved quality of care and patient’s safety initiatives are essential to reduce AEs and maternal and newborn mortality.

Rafter N , Hickey A , Condell S et al. Adverse events in healthcare: learning from mistakes . QJM 2014 ; 108 : 273 – 7 .

Google Scholar

Jha A , Pronovost P . Toward a safer health care system: the critical need to improve measurement . JAMA 2016 ; 315 : 1831 – 2 .

Brennan TA , Leape LL , Laird NM et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard medical practice study I . N Engl J Med 1991 ; 324 : 370 – 6 .

Naessens JM , O’byrne TJ , Johnson MG et al. Measuring hospital adverse events: assessing inter-rater reliability and trigger performance of the global trigger tool . Int J Qual Health Care 2010 ; 22 : 266 – 74 .

Classen DC , Resar R , Griffin F et al. ‘Global trigger tool’shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured . Health Aff 2011 ; 30 : 581 – 9 .

Mevik K , Hansen TE , Deilkås EC et al. Is a modified Global Trigger Tool method using automatic trigger identification valid when measuring adverse events? A comparison of review methods using automatic and manual trigger identification . Int J Qual Health Care 2018 .

Moller A-B , Petzold M , Chou D et al. Early antenatal care visit: a systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013 . Lancet Glob Health 2017 ; 5 : e977 – 83 .

World Health Organization . WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience . World Health Organization , 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland, 2016 .

Google Preview

Morón-Duarte LS , Ramirez Varela A , Segura O et al. Quality assessment indicators in antenatal care worldwide: a systematic review . Int J Qual Health Care 2018 .

Downs SH , Black N . The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions . J Epidemiol Community Health 1998 ; 52 : 377 – 84 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 October 2019

Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects

- Søren Valgreen Knudsen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3792-8983 1 , 3 ,

- Henrik Vitus Bering Laursen 3 ,

- Søren Paaske Johnsen 1 ,

- Paul Daniel Bartels 4 ,

- Lars Holger Ehlers 3 &

- Jan Mainz 1 , 2 , 5 , 6

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 683 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

76k Accesses

76 Citations

79 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method is widely used in quality improvement (QI) strategies. However, previous studies have indicated that methodological problems are frequent in PDSA-based QI projects. Furthermore, it has been difficult to establish an association between the use of PDSA and improvements in clinical practices and patient outcomes. The aim of this systematic review was to examine whether recently published PDSA-based QI projects show self-reported effects and are conducted according to key features of the method.

A systematic literature search was performed in the PubMed, Embase and CINAHL databases. QI projects using PDSA published in peer-reviewed journals in 2015 and 2016 were included. Projects were assessed to determine the reported effects and the use of the following key methodological features; iterative cyclic method, continuous data collection, small-scale testing and use of a theoretical rationale.

Of the 120 QI projects included, almost all reported improvement (98%). However, only 32 (27%) described a specific, quantitative aim and reached it. A total of 72 projects (60%) documented PDSA cycles sufficiently for inclusion in a full analysis of key features. Of these only three (4%) adhered to all four key methodological features.

Even though a majority of the QI projects reported improvements, the widespread challenges with low adherence to key methodological features in the individual projects pose a challenge for the legitimacy of PDSA-based QI. This review indicates that there is a continued need for improvement in quality improvement methodology.

Peer Review reports

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles are widely used for quality improvement (QI) in most healthcare systems where tools and models inspired by industrial management have become influential [ 1 ]. The essence of the PDSA cycle is to structure the process of improvement in accordance with the scientific method of experimental learning [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. It is used with consecutive iterations of the cycle constituting a framework for continuous learning through testing of changes [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

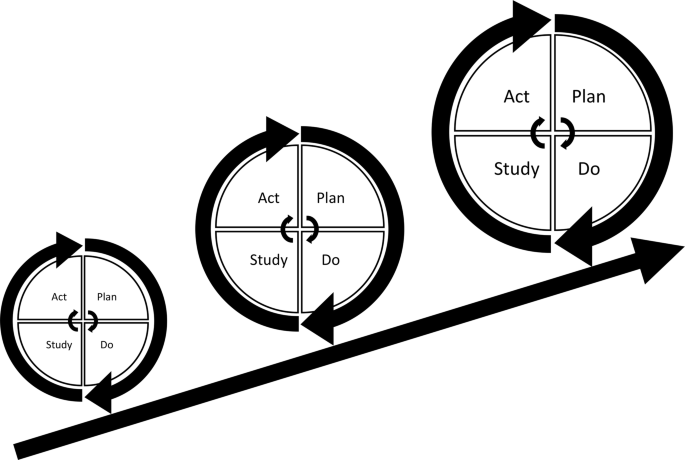

The concept of improvement through iterative cycles has formed the basis for numerous structured QI approaches including Total Quality Management, Continuous Quality Improvement, Lean, Six Sigma and the Model for Improvement [ 4 , 6 , 10 ]. These “PDSA models” have different approaches but essentially consist of improvement cycles as the cornerstone combined with a bundle of features from the management literature. Especially within healthcare, several PDSA models have been proposed for QI adding other methodological features to the basic principles of iterative PDSA cycles. Key methodological features include the use of continuous data collection [ 2 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], small-scale testing [ 6 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 ] and use of a theoretical rationale [ 5 , 9 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Most projects are initiated in the complex social context of daily clinical work [ 12 , 23 ]. In these settings, focus on use of these key methodological features ensures quality and consistency by supporting adaptation of the project to the specific context and minimizing the risk of introducing harmful or wasteful unintended consequences [ 10 ]. Thus, the PDSA cycle is not sufficient as a standalone method [ 4 ] and integration of the full bundle of key features is often simply referred to as the PDSA method (Fig. 1 ).

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) based quality improvement. Each cycle informs the subsequent cycle. Ideally, the complexity and size of the intervention is upscaled iteratively as time pass, knowledge is gained and quality of care is improved

Since its introduction to healthcare in the 1990s, numerous QI projects have been based on the PDSA method [ 10 , 24 ]. However, the scientific literature indicates that the evidence for effect is limited [ 10 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. The majority of the published PDSA projects have been hampered with severe design limitations, insufficient data analysis and incomplete reporting [ 12 , 31 ]. A 2013 systematic review revealed that only 2/73 projects reporting use of the PDSA cycle applied the PDSA method in accordance with the methodological recommendations [ 10 ]. These methodological limitations have led to an increased awareness of the need for more methodological rigor when conducting and reporting PDSA-based projects [ 4 , 10 ]. This challenge is addressed by the emergent field of Improvement Science (IS) which attempts to systematically examine methods and factors that best facilitate QI by drawing on a range of academic disciplines and encourage rigorous use of scientific methods [ 5 , 12 , 32 , 33 ]. It is important to make a distinction between local QI projects, where the primary goal is to secure a change, and IS, where the primary goal is directed at evaluation and scientific advancement [ 12 ].

In order to improve local QI projects, Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines have been developed to provide a framework for reporting QI projects [ 18 , 34 ]. Still, it remains unclear to what extent the increasing methodological awareness is reflected in PDSA-based QI projects published in recent years. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of recent peer-reviewed publications reporting QI projects using the PDSA methodology in healthcare and focused on the use of key features in the design and on the reported effects of the projects.

The key features of PDSA-based QI projects were identified, and a simple but comprehensive framework was constructed. The review was conducted in adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 35 ].

The framework

Informed by recommendations for key features in use and support of PDSA from literature specific to QI in healthcare the following key features were identified:

Use of an iterative cyclic method [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]

Use of continuous data collection [ 2 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]

Small-scale testing [ 6 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]

Explicit description of the theoretical rationale of the projects [ 5 , 9 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]

Aiming for conceptual simplicity, we established basic minimum requirements for the presence of the key features operationalizing them into binary (yes/no) variables. General characteristics and supplementary data that elaborated the use of the key features were operationalized and registered as categorical variables. See Table 1 for an overview of the framework and Additional file 1 for a more in-depth elaboration of the definitions used for the key features. Since a theoretical rationale can take multiple forms, the definition for this feature was taken from the recent version of the SQUIRE guidelines [ 18 ].

Since no formal standardized requirements for reporting PDSA-based QI projects across journals are established, not all report the individual PDSA cycles in detail. To ensure that variation in use of key features were inherent in the conduct of the projects and not just due to differences in the reporting, sufficient documentation of PDSA cycles was set as a requirement for analysis against the full framework.

Self-reported effects

A pre-specified, quantitative aim can assist to facilitate evaluation of whether the changes represent clinically relevant improvements when using the PDSA method [ 16 ]. Self-reported effects of the projects were registered using four categories: 1) Quantitative aim set and reached; 2) No quantitative aim set, improvement registered; 3) Quantitative aim set but not reached; 4) No quantitative aim and no improvement registered.

Systematic review of the literature

The target of the literature search was peer-reviewed publications that applied the PDSA cycle as the main method for a QI project in a healthcare setting. The search consisted of the terms ([ ‘PDSA’ OR ‘ plan-do-study-act’ ] AND [‘ quality ’ OR ‘ improvement ’]). The terms were searched for in title and abstract. No relevant MeSH terms were available. To get a contemporary status of the QI field, the search was limited to QI projects published in 2015 and 2016. PubMed, Embase and CINAHL databases were searched with the last search date being 2nd of March 2017.

Study selection

The following inclusion criteria were used: Peer-reviewed publications reporting QI projects using the PDSA methodology in healthcare, published in English. Exclusion criteria were: IS studies, editorials, conference abstracts, opinions and audit articles, reviews or projects solely involving teaching the PDSA method.

Two reviewers (SVK and HVBL) performed the screening process independently. Title and abstract were screened for inclusion followed by an assessment of the full text according to the eligibility criteria. This was performed in a standardized manner with the Covidence software. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data collection process

A data collection sheet was developed and pilot tested. The subsequent refinement resulted in a standardized sheet into which data were extracted independently by SVK and HVBL.

Data from the key and supplementary features were extracted in accordance with the framework. The binary data were used to grade QI projects on a scale of 0–4, based on how many of the four key features were applied. Data were analyzed in STATA (version 15.0, StataCorp LLC).

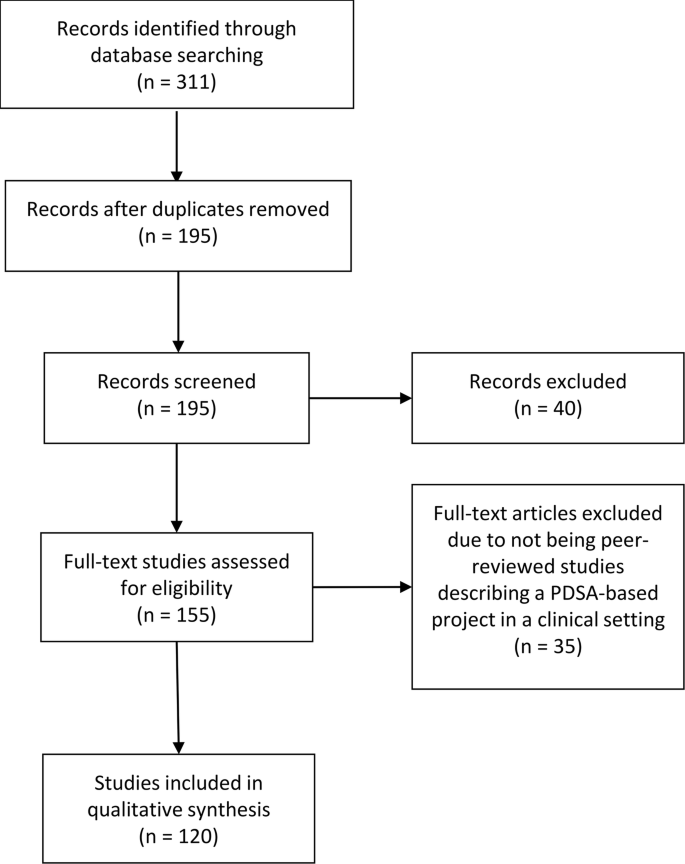

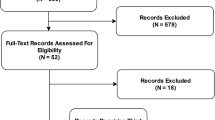

Selection process

The search identified 311 QI projects of which 195 remained after duplicate removal. A total of 40 and 35 projects were discarded after screening abstracts and full texts, respectively. Hence, a total of 120 projects met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (see Fig. 2 ).

PRISMA diagram

An overview of general characteristics, supplementary features and self-reported effects of the included projects are presented in Table 2 .

General characteristics

Country and journal.

The included QI projects originated from 18 different countries including the USA ( n = 52), the UK ( n = 43), Canada ( n = 6), Singapore ( n = 5), Saudi Arabia ( n = 4), Australia ( n = 2) and one each from eight other countries. Fifty different journals had published QI projects with the vast majority ( n = 53) being from BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. See Additional file 2 for a full summery of the findings.

Area and specialty

In terms of reach, most were local ( n = 103) followed by regional ( n = 13) and nationwide ( n = 3). The areas of healthcare were primarily at departmental ( n = 68) and hospital level ( n = 36). Many different specialties were represented, the most common being pediatrics ( n = 28), intensive or emergency care ( n = 13), surgery ( n = 12), psychiatry ( n = 11) and internal medicine ( n = 10).

Supporting framework

Most QI projects did not state using a supporting framework ( n = 70). However, when stated, most used The Model for Improvement ( n = 40). The last ( n = 10) used Lean, Six-sigma or other frameworks.

Reported effects

All 120 projects included were assessed for the self-reported effects. Overall, 118/120 (98%) projects reported improvement. Thirty-two (27%) achieved a pre-specified aim set in the planning process, whereas 68 (57%) reported an improvement without a pre-specified aim. Eighteen projects (15%) reported setting an aim and not reaching it while two (2%) projects did not report a pre-specified aim and did not report any improvement.

Documentation

Seventy-two projects had sufficient documentation of the PDSA cycles. Sixty of these contained information on individual stages of cycles, while 12 in addition presented detailed information on the four stages of the PDSA cycles.

Application of key features of PDSA

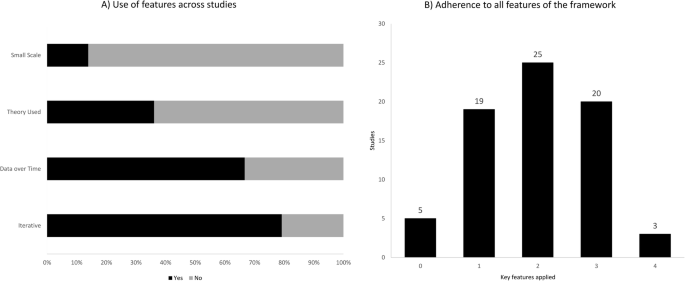

The application of the key PDSA features appeared to be highly inconsistent. The iterative method was used in 75 projects (79%), continuous data collection in 48 (67%), an explicit theoretical rational was present in 26 (36%) projects and small-scale testing was carried out by 10 (14%) (Fig. 3 a). All key features of the method were applied in 3/72 projects (4%), while 20 (28%), 26 (36%), and 18 (25%) used three, two, and one feature respectively. Five projects (7%) lacked all features (Fig. 3 b). See Additional file 3 for a full summary of the findings.

a ) Bar-chart depicting how often the four key features were used across the projects. b ) Bar-chart depicting the number of projects, which had used zero to four key features

Iterative cycles

Fifty-seven projects (79%) had a sequence of cycles where one informed the actions of the next. A single iterative chain of cycles was used in 41 (57%), while four (5%) had multiple isolated iterative chains and 12 (17%) had a mix of iterative chains and isolated cycles. Of the 15 projects using non-iterative cycles, two reported a single cycle while 13 used multiple isolated cycles. The majority (55/72) (76%) tested one change per cycle.

Small scale testing

The testing of changes in a small scale was carried out by 10 projects (14%), of which seven did so in an increasing scale, while two kept testing at the same scale. It was unclear which type of scaling was used in the remaining project. Sixty-two projects (86%) carried out testing on an entire department or engaged in full-scale implementation before having tested the improvement intervention.

Continuous data collection

Continuous measurements over time with three or more data points at regular intervals were used by 48 (67%) out of 72 projects. Of these 48, half used run charts, while the other half used control charts. Other types of data measurement such as before and after or per PDSA cycle or having a single data point as outcome after cycle(s) was done by 18 (25%) and 5 (7%), respectively. One project did not report their data. Sixty-five projects (90%) used a baseline measurement for comparison.

Theoretical rationale

Twenty-six (36%) out of 72 projects explicitly stated the theoretical rationale of the project describing why it was predicted to lead to improvement in their specific clinical context. In terms of inspiration for the need for improvement 68 projects (94%) referred to scientific literature. For the QI interventions used in the projects 26 (36%) found inspiration in externally existing knowledge in forms of scientific literature, previous QI projects or benchmarking. Twenty-one (29%) developed the projects themselves, 10 (14%) used existing knowledge in combination with own ideas while 15 (21%) did not state the source.

In this systematic review nearly all PDSA-based QI projects reported improvements. However, only approximately one out of four projects had defined a specific quantitative aim and reached it. In addition, only a small minority of the projects reported to have adhered to all four key features recommended in the literature to ensure the quality and adaptability of a QI project.

The claim that PDSA leads to improvement should be interpreted with caution. The methodological limitations in many of the projects makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the size and the causality of the reported improvements in quality of care. The methodological limitations question the legitimacy of PDSA as an effective improvement method in health care. The widespread lack of theoretical rationale and continuous data collection in the projects makes it difficult to track and correct the process as well as to relate an improvement to the use of the method [ 10 , 11 ]. The apparent limited use of the iterative approach and small-scale-testing constitute an additional methodological limitation. Without these tools of testing and adapting one can risk introducing unintended consequences [ 1 , 36 ]. Hence, QI initiatives may potentially tamper with the system in unforeseen ways creating more harm and waste than improvement. The low use of small-scale-testing could perhaps originate in a widespread misunderstanding that one should test large-scale to get a proper statistical power. However, this is not necessarily the case with PDSA [ 15 ].

There is no simple answer to this lack of adherence to the key methodological features. Some scholars claim that even though the concept of PDSA is relatively simple it is difficult to master in reality [ 4 ]. Some explanations to this have been offered including an urge to favour action over evidence [ 36 ], an inherent messiness in the actual use of the method [ 11 ], its inability to address “big and hairy” problems [ 37 ], an oversimplification of the method, and an underestimation of the required resources and support needed to conduct a PDSA-based project [ 4 ].

In some cases, it seems reasonable that the lack of adherence to the methodological recommendations is a problem with documentation rather than methodological rigor, e.g. the frequent lack of small-scale pilot testing may be due to the authors considering the information too irrelevant, while still having performed it in the projects.

Regarding our framework one could argue that it has too many or too few key features to encompass the PDSA method. The same can be said about the supplementary features where additional features could also have been assessed e.g. the use of Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timebound (SMART) goals [ 14 ]. It has been important for us to operationalize the key features so their presence easily and accurately can be identified. Simplification carries the risk of loss of information but can be outweighed by a clear and applicable framework.

This review has some limitations. We only included PDSA projects reported in peer-reviewed journals, which represents just a fraction of all QI projects being conducted around the globe. Further, it might be difficult to publish projects that do not document improvements. This may introduce potential publication bias. Future studies could use the framework to examine the grey literature of evaluation reports etc. to see if the pattern of methodological limitations is consistent. The fact that a majority of the projects reported positive change could also indicate a potential bias. For busy QI practitioners the process of translating a clinical project into a publication could well be motivated by a positive finding with projects with negative effects not being reported. However, we should not forget that negative outcome of a PDSA project may still contribute with valuable learning and competence building [ 4 , 6 ].

The field of IS and collaboration between practitioners and scholars has the potential to deliver crucial insight into the complex process of QI, including the difficulties with replicating projects with promising effect [ 5 , 12 , 20 , 32 ]. Rigorous methodological adherence may be experienced as a restriction on practitioners, which could discourage engagement in QI initiatives. However, by strengthening the use of the key features and improving documentation the PDSA projects will be more likely to contribute to IS, including reliable meta-analyses and systematic reviews [ 10 ]. This could in return provide QI practitioners with evidence-based knowledge [ 5 , 38 ]. In this way rigor in performing and documenting QI projects benefits the whole QI community in the long run. It is important that new knowledge becomes readily available and application oriented, in order for practitioners to be motivated to use it. An inherent part of using the PDSA method consists of acknowledging the complexity of creating lasting improvement. Here the scientific ideals about planning, executing, hypothesizing, data managing and documenting with rigor and high quality should serve as inspiration.

Our framework could imply that the presence of all four features will inevitably result in the success of an improvement project. This it clearly not the case. No “magic bullets” exist in QI [ 39 ]. QI is about implementing complex projects in complex social contexts. Here adherence to the key methodological recommendations and rigorous documentation can help to ensure better quality and reproducibility. This review can serve as a reminder of these features and how rigor in the individual QI projects can assist the work of IS, which in return can offer new insight for the benefit of practitioners.

This systematic review documents that substantial methodological challenges remain when reporting from PDSA projects. These challenges pose a problem for the legitimacy of the method. Individual improvement projects should strive to contribute to a scientific foundation for QI by conducting and documenting with a higher rigor. There seems to be a need for methodological improvement when conducting and reporting from QI initiatives.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

Improvement Science

Plan-Do-Study-Act

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Quality Improvement

Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timebound

Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence

Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, Benn J, Chaturvedi S, Phillips N, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical healthcare. Br J Surg. 2012;99(3):324–35.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Speroff T, O’Connor GT. Study designs for PDSA quality improvement research. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13(1):17–32.

Article Google Scholar

Moen R. Foundation and history of the PDSA cycle. Assoc Process Improv. 2009; Available from: https://deming.org/uploads/paper/PDSA_History_Ron_Moen.pdf .

Reed JE, Card AJ. The problem with plan-do-study-act cycles. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):147–52.

Portela MC, Lima SML, Martins M, Travassos C. Improvement Science: conceptual and theoretical foundations for its application to healthcare quality improvement. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32(sup 2):e00105815.

Google Scholar

Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide, 2nd edition. Jossey-Bass. 2009.

Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2008;299(10):1182–4.

Berwick DM, Nolan TW. Developing and testing changes in delivery of care. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(1):651–6.

Perla RJ, Provost LP, Parry GJ. Seven propositions of the science of improvement: exploring foundations. Qual Manag Health Care. 2013;22(3):170–86.

Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;0:1–9.

Ogrinc G. Building knowledge, asking questions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):265–7.

Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M. How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1076):343–54.

Thor J, Lundberg J, Ask J, Olsson J, Carli C, Härenstam KP, et al. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: systematic review. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2007;16(5):387–99.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Etchells E, Ho M, Shojania KG. Value of small sample sizes in rapid-cycle quality improvement projects. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):202–6.

Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ Br Med J. 1996;312(7031):619.

Speroff T, James BC, Nelson EC, Headrick LA, Brommels M. Guidelines for appraisal and publication of PDSA quality improvement. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13(1):33–9.

Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence 2.0: revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:986–92.

Moonesinghe SR, Peden CJ. Theory and context: putting the science into improvement. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(4):482–4.

Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):228–38.

Foy R, Ovretveit J, Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Taylor SL, Dy S, et al. The role of theory in research to develop and evaluate the implementation of patient safety practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(5):453–9.

Walshe K. Pseudoinnovation: the development and spread of healthcare quality improvement methodologies. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2009;21(3):153–9.

Walshe K. Understanding what works-and why-in quality improvement: the need for theory-driven evaluation. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19(2):57–9.

Powell AE, Rushmer RK, Davies HT. A systematic narrative review of quality improvement models in health care. Glasgow: Quality Improvement Scotland (NHS QIS ). 2009.

Groene O. Does quality improvement face a legitimacy crisis? Poor quality studies, small effects. J Heal Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(3):131–2.

Dixon-Woods M, Martin G. Does quality improvement improve quality? Futur Hosp J. 2016;3(3):191–4.

Blumenthal D, Kilo CM. A report Card on continuous quality improvement. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):625–48.

Dellifraine JL, Langabeer JR, Nembhard IM. Assessing the evidence of six sigma and lean in the health care industry. Qual Manag Health Care. 2010;19(3):211–25.

D’Andreamatteo A, Ianni L, Lega F, Sargiacomo M. Lean in healthcare: a comprehensive review. Health Policy (New York). 2015;119(9):1197–209.

Moraros J, Lemstra M, Nwankwo C. Lean interventions in healthcare: do they actually work? A systematic literature review. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2016:150–65.

Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff. 2005;24(1):138–50.

Marshall M, Pronovost P, Dixon-Woods M. Promotion of improvement as a science. Lancet. 2013;381(9881):419–21.

The Health Foundation. Improvement science. Heal Found Heal Scan. 2011. Available from: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/ImprovementScience.pdf .

Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2008;17(SUPPL. 1):i3–9.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Br Med J. 2009;339:b2700.

Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608–13.

Dixon-Woods M, Martin G, Tarrant C, Bion J, Goeschel C, Pronovost P, et al. Safer clinical systems: evaluation findings. Heal Found. 2014; Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/safer-clinical-systems-evaluation-findings .

Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: developing an ex post theory of a quality improvement program. Milbank Q. 2011;89(2):167–205.

Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes B. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Cmaj. 1995;153(10):1423–31.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The review was funded by Aalborg University, Denmark. The funding body had no influence on the study design, on the collection, analysis and interpretation of data or on the design of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Danish Center for Clinical Health Services Research (DACS), Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Mølleparkvej 10, 9000, Aalborg, Denmark

Søren Valgreen Knudsen, Søren Paaske Johnsen & Jan Mainz

Psychiatry, Aalborg University Hospital, The North Denmark Region Mølleparkvej 10, 9000, Aalborg, Denmark

Danish Center for Healthcare Improvements (DCHI), Aalborg University, Fibigerstræde 11, 9220, Aalborg Øst, Denmark

Søren Valgreen Knudsen, Henrik Vitus Bering Laursen & Lars Holger Ehlers

Danish Clinical Registries, Denmark, Nrd. Fasanvej 57, 2000, Frederiksberg, Denmark

Paul Daniel Bartels

Department for Community Mental Health, Haifa University, Haifa, Israel

Department of Health Economics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to the review. SVK and HVBL have been the primary authors and have made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data as well as developing drafts of the manuscript. LHE and JM have been primary supervisors and have contributed substantially with intellectual feedback and manuscript revision. SPJ and PB have made substantial contributions by revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. Each author agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work and all authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Søren Valgreen Knudsen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Description of variables and coding. (DOCX 24 kb)

Additional file 2:

Projects identified in the search that used PDSA method. (DOCX 204 kb)

Additional file 3:

Projects identified in search that describes PDSA method in sufficient detail to be included for full analysis for framework. (DOCX 145 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Knudsen, S.V., Laursen, H.V.B., Johnsen, S.P. et al. Can quality improvement improve the quality of care? A systematic review of reported effects and methodological rigor in plan-do-study-act projects. BMC Health Serv Res 19 , 683 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4482-6

Download citation

Received : 07 January 2019

Accepted : 28 August 2019

Published : 04 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4482-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Plan-do-study-act

- Health services research

- Quality improvement

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Quality improvement...

Quality improvement into practice

Read the full collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Adam Backhouse , quality improvement programme lead 1 ,

- Fatai Ogunlayi , public health specialty registrar 2

- 1 North London Partners in Health and Care, Islington CCG, London N1 1TH, UK

- 2 Institute of Applied Health Research, Public Health, University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

- Correspondence to: A Backhouse adam.backhouse{at}nhs.net

What you need to know

Thinking of quality improvement (QI) as a principle-based approach to change provides greater clarity about ( a ) the contribution QI offers to staff and patients, ( b ) how to differentiate it from other approaches, ( c ) the benefits of using QI together with other change approaches

QI is not a silver bullet for all changes required in healthcare: it has great potential to be used together with other change approaches, either concurrently (using audit to inform iterative tests of change) or consecutively (using QI to adapt published research to local context)

As QI becomes established, opportunities for these collaborations will grow, to the benefit of patients.

The benefits to front line clinicians of participating in quality improvement (QI) activity are promoted in many health systems. QI can represent a valuable opportunity for individuals to be involved in leading and delivering change, from improving individual patient care to transforming services across complex health and care systems. 1

However, it is not clear that this promotion of QI has created greater understanding of QI or widespread adoption. QI largely remains an activity undertaken by experts and early adopters, often in isolation from their peers. 2 There is a danger of a widening gap between this group and the majority of healthcare professionals.

This article will make it easier for those new to QI to understand what it is, where it fits with other approaches to improving care (such as audit or research), when best to use a QI approach, making it easier to understand the relevance and usefulness of QI in delivering better outcomes for patients.

How this article was made

AB and FO are both specialist quality improvement practitioners and have developed their expertise working in QI roles for a variety of UK healthcare organisations. The analysis presented here arose from AB and FO’s observations of the challenges faced when introducing QI, with healthcare providers often unable to distinguish between QI and other change approaches, making it difficult to understand what QI can do for them.

How is quality improvement defined?

There are many definitions of QI ( box 1 ). The BMJ ’s Quality Improvement series uses the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges definition. 6 Rather than viewing QI as a single method or set of tools, it can be more helpful to think of QI as based on a set of principles common to many of these definitions: a systematic continuous approach that aims to solve problems in healthcare, improve service provision, and ultimately provide better outcomes for patients.

Definitions of quality improvement

Improvement in patient outcomes, system performance, and professional development that results from a combined, multidisciplinary approach in how change is delivered. 3

The delivery of healthcare with improved outcomes and lower cost through continuous redesigning of work processes and systems. 4

Using a systematic change method and strategies to improve patient experience and outcome. 5

To make a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness, and experience of care by using understanding of our complex healthcare environment, applying a systematic approach, and designing, testing, and implementing changes using real time measurement for improvement. 6

In this article we discuss QI as an approach to improving healthcare that follows the principles outlined in box 2 ; this may be a useful reference to consider how particular methods or tools could be used as part of a QI approach.

Principles of QI

Primary intent— To bring about measurable improvement to a specific aspect of healthcare delivery, often with evidence or theory of what might work but requiring local iterative testing to find the best solution. 7

Employing an iterative process of testing change ideas— Adopting a theory of change which emphasises a continuous process of planning and testing changes, studying and learning from comparing the results to a predicted outcome, and adapting hypotheses in response to results of previous tests. 8 9

Consistent use of an agreed methodology— Many different QI methodologies are available; commonly cited methodologies include the Model for Improvement, Lean, Six Sigma, and Experience-based Co-design. 4 Systematic review shows that the choice of tools or methodologies has little impact on the success of QI provided that the chosen methodology is followed consistently. 10 Though there is no formal agreement on what constitutes a QI tool, it would include activities such as process mapping that can be used within a range of QI methodological approaches. NHS Scotland’s Quality Improvement Hub has a glossary of commonly used tools in QI. 11

Empowerment of front line staff and service users— QI work should engage staff and patients by providing them with the opportunity and skills to contribute to improvement work. Recognition of this need often manifests in drives from senior leadership or management to build QI capability in healthcare organisations, but it also requires that frontline staff and service users feel able to make use of these skills and take ownership of improvement work. 12

Using data to drive improvement— To drive decision making by measuring the impact of tests of change over time and understanding variation in processes and outcomes. Measurement for improvement typically prioritises this narrative approach over concerns around exactness and completeness of data. 13 14

Scale-up and spread, with adaptation to context— As interventions tested using a QI approach are scaled up and the degree of belief in their efficacy increases, it is desirable that they spread outward and be adopted by others. Key to successful diffusion of improvement is the adaption of interventions to new environments, patient and staff groups, available resources, and even personal preferences of healthcare providers in surrounding areas, again using an iterative testing approach. 15 16

What other approaches to improving healthcare are there?

Taking considered action to change healthcare for the better is not new, but QI as a distinct approach to improving healthcare is a relatively recent development. There are many well established approaches to evaluating and making changes to healthcare services in use, and QI will only be adopted more widely if it offers a new perspective or an advantage over other approaches in certain situations.

A non-systematic literature scan identified the following other approaches for making change in healthcare: research, clinical audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation. We also identified innovation as an important catalyst for change, but we did not consider it an approach to evaluating and changing healthcare services so much as a catch-all term for describing the development and introduction of new ideas into the system. A summary of the different approaches and their definition is shown in box 3 . Many have elements in common with QI, but there are important difference in both intent and application. To be useful to clinicians and managers, QI must find a role within healthcare that complements research, audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation while retaining the core principles that differentiate it from these approaches.

Alternatives to QI

Research— The attempt to derive generalisable new knowledge by addressing clearly defined questions with systematic and rigorous methods. 17

Clinical audit— A way to find out if healthcare is being provided in line with standards and to let care providers and patients know where their service is doing well, and where there could be improvements. 18

Service evaluation— A process of investigating the effectiveness or efficiency of a service with the purpose of generating information for local decision making about the service. 19

Clinical transformation— An umbrella term for more radical approaches to change; a deliberate, planned process to make dramatic and irreversible changes to how care is delivered. 20

Innovation— To develop and deliver new or improved health policies, systems, products and technologies, and services and delivery methods that improve people’s health. Health innovation responds to unmet needs by employing new ways of thinking and working. 21

Why do we need to make this distinction for QI to succeed?

Improvement in healthcare is 20% technical and 80% human. 22 Essential to that 80% is clear communication, clarity of approach, and a common language. Without this shared understanding of QI as a distinct approach to change, QI work risks straying from the core principles outlined above, making it less likely to succeed. If practitioners cannot communicate clearly with their colleagues about the key principles and differences of a QI approach, there will be mismatched expectations about what QI is and how it is used, lowering the chance that QI work will be effective in improving outcomes for patients. 23

There is also a risk that the language of QI is adopted to describe change efforts regardless of their fidelity to a QI approach, either due to a lack of understanding of QI or a lack of intention to carry it out consistently. 9 Poor fidelity to the core principles of QI reduces its effectiveness and makes its desired outcome less likely, leading to wasted effort by participants and decreasing its credibility. 2 8 24 This in turn further widens the gap between advocates of QI and those inclined to scepticism, and may lead to missed opportunities to use QI more widely, consequently leading to variation in the quality of patient care.

Without articulating the differences between QI and other approaches, there is a risk of not being able to identify where a QI approach can best add value. Conversely, we might be tempted to see QI as a “silver bullet” for every healthcare challenge when a different approach may be more effective. In reality it is not clear that QI will be fit for purpose in tackling all of the wicked problems of healthcare delivery and we must be able to identify the right tool for the job in each situation. 25 Finally, while different approaches will be better suited to different types of challenge, not having a clear understanding of how approaches differ and complement each other may mean missed opportunities for multi-pronged approaches to improving care.

What is the relationship between QI and other approaches such as audit?

Academic journals, healthcare providers, and “arms-length bodies” have made various attempts to distinguish between the different approaches to improving healthcare. 19 26 27 28 However, most comparisons do not include QI or compare QI to only one or two of the other approaches. 7 29 30 31 To make it easier for people to use QI approaches effectively and appropriately, we summarise the similarities, differences, and crossover between QI and other approaches to tackling healthcare challenges ( fig 1 ).

How quality improvement interacts with other approaches to improving healthcare

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

QI and research

Research aims to generate new generalisable knowledge, while QI typically involves a combination of generating new knowledge or implementing existing knowledge within a specific setting. 32 Unlike research, including pragmatic research designed to test effectiveness of interventions in real life, QI does not aim to provide generalisable knowledge. In common with QI, research requires a consistent methodology. This method is typically used, however, to prove or disprove a fixed hypothesis rather than the adaptive hypotheses developed through the iterative testing of ideas typical of QI. Both research and QI are interested in the environment where work is conducted, though with different intentions: research aims to eliminate or at least reduce the impact of many variables to create generalisable knowledge, whereas QI seeks to understand what works best in a given context. The rigour of data collection and analysis required for research is much higher; in QI a criterion of “good enough” is often applied.

Relationship with QI

Though the goal of clinical research is to develop new knowledge that will lead to changes in practice, much has been written on the lag time between publication of research evidence and system-wide adoption, leading to delays in patients benefitting from new treatments or interventions. 33 QI offers a way to iteratively test the conditions required to adapt published research findings to the local context of individual healthcare providers, generating new knowledge in the process. Areas with little existing knowledge requiring further research may be identified during improvement activities, which in turn can form research questions for further study. QI and research also intersect in the field of improvement science, the academic study of QI methods which seeks to ensure QI is carried out as effectively as possible. 34

Scenario: QI for translational research

Newly published research shows that a particular physiotherapy intervention is more clinically effective when delivered in short, twice-daily bursts rather than longer, less frequent sessions. A team of hospital physiotherapists wish to implement the change but are unclear how they will manage the shift in workload and how they should introduce this potentially disruptive change to staff and to patients.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article?

Adopting a QI approach, the team realise that, although the change they want to make is already determined, the way in which it is introduced and adapted to their wards is for them to decide. They take time to explain the benefits of the change to colleagues and their current patients, and ask patients how they would best like to receive their extra physiotherapy sessions.

The change is planned and tested for two weeks with one physiotherapist working with a small number of patients. Data are collected each day, including reasons why sessions were missed or refused. The team review the data each day and make iterative changes to the physiotherapist’s schedule, and to the times of day the sessions are offered to patients. Once an improvement is seen, this new way of working is scaled up to all of the patients on the ward.

The findings of the work are fed into a service evaluation of physiotherapy provision across the hospital, which uses the findings of the QI work to make recommendations about how physiotherapy provision should be structured in the future. People feel more positive about the change because they know colleagues who have already made it work in practice.

QI and clinical audit

Clinical audit is closely related to QI: it is often used with the intention of iteratively improving the standard of healthcare, albeit in relation to a pre-determined standard of best practice. 35 When used iteratively, interspersed with improvement action, the clinical audit cycle adheres to many of the principles of QI. However, in practice clinical audit is often used by healthcare organisations as an assurance function, making it less likely to be carried out with a focus on empowering staff and service users to make changes to practice. 36 Furthermore, academic reviews of audit programmes have shown audit to be an ineffective approach to improving quality due to a focus on data collection and analysis without a well developed approach to the action section of the audit cycle. 37 Clinical audits, such as the National Clinical Audit Programme in the UK (NCAPOP), often focus on the management of specific clinical conditions. QI can focus on any part of service delivery and can take a more cross-cutting view which may identify issues and solutions that benefit multiple patient groups and pathways. 30

Audit is often the first step in a QI process and is used to identify improvement opportunities, particularly where compliance with known standards for high quality patient care needs to be improved. Audit can be used to establish a baseline and to analyse the impact of tests of change against the baseline. Also, once an improvement project is under way, audit may form part of rapid cycle evaluation, during the iterative testing phase, to understand the impact of the idea being tested. Regular clinical audit may be a useful assurance tool to help track whether improvements have been sustained over time.

Scenario: Audit and QI

A foundation year 2 (FY2) doctor is asked to complete an audit of a pre-surgical pathway by looking retrospectively through patient documentation. She concludes that adherence to best practice is mixed and recommends: “Remind the team of the importance of being thorough in this respect and re-audit in 6 months.” The results are presented at an audit meeting, but a re-audit a year later by a new FY2 doctor shows similar results.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this paper?

Contrast the above with a team-led, rapid cycle audit in which everyone contributes to collecting and reviewing data from the previous week, discussed at a regular team meeting. Though surgical patients are often transient, their experience of care and ideas for improvement are captured during discharge conversations. The team identify and test several iterative changes to care processes. They document and test these changes between audits, leading to sustainable change. Some of the surgeons involved work across multiple hospitals, and spread some of the improvements, with the audit tool, as they go.

QI and service evaluation

In practice, service evaluation is not subject to the same rigorous definition or governance as research or clinical audit, meaning that there are inconsistencies in the methodology for carrying it out. While the primary intent for QI is to make change that will drive improvement, the primary intent for evaluation is to assess the performance of current patient care. 38 Service evaluation may be carried out proactively to assess a service against its stated aims or to review the quality of patient care, or may be commissioned in response to serious patient harm or red flags about service performance. The purpose of service evaluation is to help local decision makers determine whether a service is fit for purpose and, if necessary, identify areas for improvement.

Service evaluation may be used to initiate QI activity by identifying opportunities for change that would benefit from a QI approach. It may also evaluate the impact of changes made using QI, either during the work or after completion to assess sustainability of improvements made. Though likely planned as separate activities, service evaluation and QI may overlap and inform each other as they both develop. Service evaluation may also make a judgment about a service’s readiness for change and identify any barriers to, or prerequisites for, carrying out QI.

QI and clinical transformation

Clinical transformation involves radical, dramatic, and irreversible change—the sort of change that cannot be achieved through continuous improvement alone. As with service evaluation, there is no consensus on what clinical transformation entails, and it may be best thought of as an umbrella term for the large scale reform or redesign of clinical services and the non-clinical services that support them. 20 39 While it is possible to carry out transformation activity that uses elements of QI approach, such as effective engagement of the staff and patients involved, QI which rests on iterative test of change cannot have a transformational approach—that is, one-off, irreversible change.

There is opportunity to use QI to identify and test ideas before full scale clinical transformation is implemented. This has the benefit of engaging staff and patients in the clinical transformation process and increasing the degree of belief that clinical transformation will be effective or beneficial. Transformation activity, once completed, could be followed up with QI activity to drive continuous improvement of the new process or allow adaption of new ways of working. As interventions made using QI are scaled up and spread, the line between QI and transformation may seem to blur. The shift from QI to transformation occurs when the intention of the work shifts away from continuous testing and adaptation into the wholesale implementation of an agreed solution.

Scenario: QI and clinical transformation

An NHS trust’s human resources (HR) team is struggling to manage its junior doctor placements, rotas, and on-call duties, which is causing tension and has led to concern about medical cover and patient safety out of hours. A neighbouring trust has launched a smartphone app that supports clinicians and HR colleagues to manage these processes with the great success.

This problem feels ripe for a transformation approach—to launch the app across the trust, confident that it will solve the trust’s problems.

Before continuing reading think about your own organisation— What do you think will happen, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article for this situation?

Outcome without QI

Unfortunately, the HR team haven’t taken the time to understand the underlying problems with their current system, which revolve around poor communication and clarity from the HR team, based on not knowing who to contact and being unable to answer questions. HR assume that because the app has been a success elsewhere, it will work here as well.

People get excited about the new app and the benefits it will bring, but no consideration is given to the processes and relationships that need to be in place to make it work. The app is launched with a high profile campaign and adoption is high, but the same issues continue. The HR team are confused as to why things didn’t work.

Outcome with QI

Although the app has worked elsewhere, rolling it out without adapting it to local context is a risk – one which application of QI principles can mitigate.

HR pilot the app in a volunteer specialty after spending time speaking to clinicians to better understand their needs. They carry out several tests of change, ironing out issues with the process as they go, using issues logged and clinician feedback as a source of data. When they are confident the app works for them, they expand out to a directorate, a division, and finally the transformational step of an organisation-wide rollout can be taken.

Education into practice

Next time when faced with what looks like a quality improvement (QI) opportunity, consider asking:

How do you know that QI is the best approach to this situation? What else might be appropriate?

Have you considered how to ensure you implement QI according to the principles described above?

Is there opportunity to use other approaches in tandem with QI for a more effective result?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

This article was conceived and developed in response to conversations with clinicians and patients working together on co-produced quality improvement and research projects in a large UK hospital. The first iteration of the article was reviewed by an expert patient, and, in response to their feedback, we have sought to make clearer the link between understanding the issues raised and better patient care.

Contributors: This work was initially conceived by AB. AB and FO were responsible for the research and drafting of the article. AB is the guarantor of the article.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ , including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Olsson-Brown A

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Batalden PB ,

- Berwick D ,

- Øvretveit J

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

- Nelson WA ,

- McNicholas C ,

- Woodcock T ,

- Alderwick H ,

- ↵ NHS Scotland Quality Improvement Hub. Quality improvement glossary of terms. http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/qi-basics/quality-improvement-glossary-of-terms.aspx .

- McNicol S ,

- Solberg LI ,

- Massoud MR ,

- Albrecht Y ,

- Illingworth J ,

- Department of Health

- ↵ NHS England. Clinical audit. https://www.england.nhs.uk/clinaudit/ .

- Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership

- McKinsey Hospital Institute

- ↵ World Health Organization. WHO Health Innovation Group. 2019. https://www.who.int/life-course/about/who-health-innovation-group/en/ .

- Sheffield Microsystem Coaching Academy

- Davidoff F ,

- Leviton L ,

- Taylor MJ ,

- Nicolay C ,

- Tarrant C ,

- Twycross A ,

- ↵ University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. Is your study research, audit or service evaluation. http://www.uhbristol.nhs.uk/research-innovation/for-researchers/is-it-research,-audit-or-service-evaluation/ .

- ↵ University of Sheffield. Differentiating audit, service evaluation and research. 2006. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.158539!/file/AuditorResearch.pdf .

- ↵ Royal College of Radiologists. Audit and quality improvement. https://www.rcr.ac.uk/clinical-radiology/audit-and-quality-improvement .

- Gundogan B ,

- Finkelstein JA ,

- Brickman AL ,

- Health Foundation

- Johnston G ,

- Crombie IK ,

- Davies HT ,

- Hillman T ,

- ↵ NHS Health Research Authority. Defining research. 2013. https://www.clahrc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/defining-research.pdf .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 09 April 2024

The potential for artificial intelligence to transform healthcare: perspectives from international health leaders

- Christina Silcox 1 ,

- Eyal Zimlichmann 2 , 3 ,

- Katie Huber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2519-8714 1 ,

- Neil Rowen 1 ,

- Robert Saunders 1 ,

- Mark McClellan 1 ,

- Charles N. Kahn III 3 , 4 ,

- Claudia A. Salzberg 3 &

- David W. Bates ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6268-1540 5 , 6 , 7

npj Digital Medicine volume 7 , Article number: 88 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2843 Accesses

39 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health policy

- Health services

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform care delivery by improving health outcomes, patient safety, and the affordability and accessibility of high-quality care. AI will be critical to building an infrastructure capable of caring for an increasingly aging population, utilizing an ever-increasing knowledge of disease and options for precision treatments, and combatting workforce shortages and burnout of medical professionals. However, we are not currently on track to create this future. This is in part because the health data needed to train, test, use, and surveil these tools are generally neither standardized nor accessible. There is also universal concern about the ability to monitor health AI tools for changes in performance as they are implemented in new places, used with diverse populations, and over time as health data may change. The Future of Health (FOH), an international community of senior health care leaders, collaborated with the Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy to conduct a literature review, expert convening, and consensus-building exercise around this topic. This commentary summarizes the four priority action areas and recommendations for health care organizations and policymakers across the globe that FOH members identified as important for fully realizing AI’s potential in health care: improving data quality to power AI, building infrastructure to encourage efficient and trustworthy development and evaluations, sharing data for better AI, and providing incentives to accelerate the progress and impact of AI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Guiding principles for the responsible development of artificial intelligence tools for healthcare

A short guide for medical professionals in the era of artificial intelligence

Reporting guidelines in medical artificial intelligence: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

Artificial intelligence (AI), supported by timely and accurate data and evidence, has the potential to transform health care delivery by improving health outcomes, patient safety, and the affordability and accessibility of high-quality care 1 , 2 . AI integration is critical to building an infrastructure capable of caring for an increasingly aging population, utilizing an ever-increasing knowledge of disease and options for precision treatments, and combatting workforce shortages and burnout of medical professionals. However, we are not currently on track to create this future. This is in part because the health data needed to train, test, use, and surveil these tools are generally neither standardized nor accessible. This is true across the international community, although there is variable progress within individual countries. There is also universal concern about monitoring health AI tools for changes in performance as they are implemented in new places, used with diverse populations, and over time as health data may change.

The Future of Health (FOH) is an international community of senior health care leaders representing health systems, health policy, health care technology, venture funding, insurance, and risk management. FOH collaborated with the Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy to conduct a literature review, expert convening, and consensus-building exercise. In total, 46 senior health care leaders were engaged in this work, from eleven countries in Europe, North America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. This commentary summarizes the four priority action areas and recommendations for health care organizations and policymakers that FOH members identified as important for fully realizing AI’s potential in health care: improving data quality to power AI, building infrastructure to encourage efficient and trustworthy development and evaluations, sharing data for better AI, and providing incentives to accelerate the progress and impact of AI.

Powering AI through high-quality data

“Going forward, data are going to be the most valuable commodity in health care. Organizations need robust plans about how to mobilize and use their data.”

AI algorithms will only perform as well as the accuracy and completeness of key underlying data, and data quality is dependent on actions and workflows that encourage trust.

To begin to improve data quality, FOH members agreed that an initial priority is identifying and assuring reliable availability of high-priority data elements for promising AI applications: those with the most predictive value, those of the highest value to patients, and those most important for analyses of performance, including subgroup analyses to detect bias.

Leaders should also advocate for aligned policy incentives to improve the availability and reliability of these priority data elements. There are several examples of efforts across the world to identify and standardize high-priority data elements for AI applications and beyond, such as the multinational project STANDING Together, which is developing standards to improve the quality and representativeness of data used to build and test AI tools 3 .

Policy incentives that would further encourage high-quality data collection include (1) aligned payment incentives for measures of health care quality and safety, and ensuring the reliability of the underlying data, and (2) quality measures and performance standards focused on the reliability, completeness, and timeliness of collection and sharing of high-priority data itself.

Trust and verify

“Your AI algorithms are only going to be as good as the data and the real-world evidence used to validate them, and the data are only going to be as good as the trust and privacy and supporting policies.”

FOH members stressed the importance of showing that AI tools are both effective and safe within their specific patient populations.

This is a particular challenge with AI tools, whose performance can differ dramatically across sites and over time, as health data patterns and population characteristics vary. For example, several studies of the Epic Sepsis Model found both location-based differences in performance and degradation in performance over time due to data drift 4 , 5 . However, real-world evaluations are often much more difficult for algorithms that are used for longer-term predictions, or to avert long-term complications from occurring, particularly in the absence of connected, longitudinal data infrastructure. As such, health systems must prioritize implementing data standards and data infrastructure that can facilitate the retraining or tuning of algorithms, test for local performance and bias, and ensure scalability across the organization and longer-term applications 6 .

There are efforts to help leaders and health systems develop consensus-based evaluation techniques and infrastructure for AI tools, including HealthAI: The Global Agency for Responsible AI in Health, which aims to build and certify validation mechanisms for nations and regions to adopt; and the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI), which recently announced plans to build a US-wide health AI assurance labs network 7 , 8 . These efforts, if successful, will assist manufacturers and health systems in complying with new laws, rules, and regulations being proposed and released that seek to ensure AI tools are trustworthy, such as the EU AI Act and the 2023 US Executive Order on AI.

Sharing data for better AI