- Download PDF

- CME & MOC

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Practical Guide to Education Program Evaluation Research

- 1 Department of Surgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

- 2 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora

- 3 Statistical Editor, JAMA Surgery

- 4 Department of Surgery, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston University, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

- Editorial Improving the Integrity of Surgical Education Scholarship Amalia Cochran, MD, MA; Dimitrios Stefanidis, MD, PhD; Melina R. Kibbe, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Ethics in Surgical Education Research Michael M. Awad, MD, PhD, MHPE; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, PhD, MTS, MPH, MBA JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Curricular Development Research Kevin Y. Pei, MD, MHS; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH; Marja A. Boermeester, MD, PhD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Assessment Tool Development for Surgical Education Research Mohsen M. Shabahang, MD, PhD; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH; Liane S. Feldman, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Research in Surgical Education Roy Phitayakorn, MD, MHPE; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH; Gerard M. Doherty, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Pragmatic Clinical Trials in Surgical Education Research Karl Y. Bilimoria, MD, MS; Jason S. Haukoos, MD, MSc; Gerard M. Doherty, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Survey Research in Surgical Education Adnan A. Alseidi, MD, EdM; Jason S. Haukoos, MD, MSc; Christian de Virgilio, MD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Common Flaws With Surgical Education Research Dimitrios Stefanidis, MD, PhD; Laura Torbeck, PhD; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Surgical Education Research Daniel A. Hashimoto, MD; Julian Varas, MD; Todd A. Schwartz, DrPH JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Surgical Simulation Research Aimee K. Gardner, PhD; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Marja Boermeester, MD, PhD JAMA Surgery

- Guide to Statistics and Methods Practical Guide to Qualitative Research in Surgical Education Gurjit Sandhu, PhD; Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD; Amalia Cochran, MD, MA JAMA Surgery

Program evaluation is the systematic assessment of a program’s implementation. In medical education, evaluation includes the synthesis and analysis of educational programs, which in turn provides evidence for educational best practices. In medical education, as in other fields, the quality of the synthesis is dependent on the rigor by which evaluations are performed. Individual program evaluation is best achieved when similar programs apply the same scientific rigor and methodology to assess outcomes, thus allowing for direct comparisons. The pedagogy of a given program, particularly in medical education, can be driven by nonscientific forces (ie, political, faddism, or ideology) rather than evidence. 1 This often impedes more rapid progress of educational methods to achieve an educational goal compared with a more evidence-based practice. 2

- Editorial Improving the Integrity of Surgical Education Scholarship JAMA Surgery

Read More About

de Moya M , Haukoos JS , Itani KMF. Practical Guide to Education Program Evaluation Research. JAMA Surg. Published online January 03, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.6702

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Surgery in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Program Evaluation

- First Online: 01 January 2011

Cite this chapter

- Christel A. Woodward 7

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE,volume 7))

1268 Accesses

2 Citations

Program evaluation provides a set of procedures and tools that can be employed to provide useful information about medical school programs and their components to decision-makers. This chapter begins with contemporary views of program evaluation. It describes the various proposals of evaluation and the areas of decision-making that they can inform. Logic models are introduced as a tool to facilitate evaluation activities. The importance of including stakeholders in planning an evaluation and in clarifying the evaluation questions and goals is stressed. Evaluation requires careful planning, as this activity is always somewhat political in nature. Inadequate attention to planning may lead to questionable information and to poor uptake of results. A series of basic issues that must be considered in developing an evaluation strategy for medical education programs is described and illustrated with examples from recent program evaluation activities in undergraduate medical education. Recommendations are made about how we can continue to improve evaluation activities including some guidelines for those who wish to evaluate medical education programs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Albanese, M. (1999) Rating educational quality: factors in the erosion of professional standards . Academic Medicine 74(6) 652–658.

Article Google Scholar

Ashikawa, H., Hojat, M., Zeleznik, C., & Gonella, J. S. (1991). Reexamination of relationships between students’ undergraduate majors, medical school performances, and career plans at Jefferson Medical College . Academic Medicine 66(8) 458–464.

Cantor, J. C., Cohen, A. B., Barker, D. C., Shuster, A. L., & Reynolds, R. C. (1991). Medical educators’views on medical education reform. Journal of the American Medical Association 265(8) 1002–1006.

Case, S. M., Swanson, D. B., Ripkey, D. R., Bowles, L. T., & Melnick, D. E. (1996). Performance of the class of 1994 in the new era of USMLE. Academic Medicine 71(10 Suppl), S91–93.

Chung, T. W. H., Lam, T. H., & Cheng, Y. H. (1996). Knowledge and attitudes about smoking in medical students before and after a tobacco seminar. Medical Education 30(4) 290–295.

Cooper, H. & Hedges, L. V. (1994). The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Google Scholar

Cronbach, L. J. (1982). Designing and evaluations of educational and social programs . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Des Marchais, J. E., & Bondage G. (1998). Sustaining curricular change at Sherbrooke through external, formative program evaluation. Academic Medicine 73(5), 494–503.

Eisner, E. W. (1976). Educational connoisseurship and criticism: their form and function in educational evaluation. Journal of Aesthetic Education 3 135–150.

Ferrier, B. M., & Woodward, C. A. (1987). A comparison of the career choices of McMaster medical graduates and contemporary Canadian graduates: a secondary analysis of the physician manpower data collected by the Canadian Medical Association. Canadian Medical Association Journal 136 39–44.

Foster, E. A. (1994). Long-term follow-up of an alternative medical curriculum. Academic Medicine 69(6), 501–506.

Friedman, C. P., Krams, D. S., & Mattem, W. D. (1991). Improving the curriculum through continuous evaluation. Academic Medicine 66(5), 257–258.

Friedman, C. P., deBliek, R., Greer, D. S., Mennin, S. P., Norman, G. R., Sheps, Swanson, D. B., & Woodward, C. A. (1990). Charting the winds of change: evaluating innovative medical curricula. Academic Medicine 65 8–14. Reprinted in: Ann Community-Oriented Educ (1992) 5 167–180.

Gerrity, M. S., & Mahaffy, J. (1998). Evaluating change in medical school curricula: How did we know where we were going? Academic Medicine 73(Suppl 9), S55–S59.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hafferty, F. W. (1998). Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Academic Medicine 73(4), 403–407.

Hagenfeldt, K., & Lowry, S. (1997). Evaluation of undergraduate medical education - why and wow? Annals of Medicine 29 357–358.

Hojat, M., Brigham, T. P., Gottheil, E., Xu, G., Glaser, K., & Veloski, J. J. (1998). Medical students’ personal values and their career choices a quarter-century later. Psychological Reports 83(1), 243–248.

Hojat, M., Gonnella, J. S., Veloski, J. J., & Erdmann, J. B. (1993). Is the glass half full or half empty? A reexamination of the associations between assessment measures during medical school and clinical competence after graduation. Academic Medicine 68 ( 2 Suppl.), S69–76.

Hojat, M., Gonnella, J. S., & Xu, G. (1995). Gender comparisons of young physicians’ perceptions of their medical education, professional life, and practice: a follow-up study of Jefferson Medical College graduates. Academic Medicine 70(4), 305–312.

Informatics Panel and the Population Perspective Panel. (1999). The Medical School Objectives Project. Contemporary issues in medicine - medical informatics and population health: report II of the Medical School Objectives Project . Academic Medicine 74(2) 130–141.

Kassebaum, D. (1990). The measurement of outcomes in the assessment of educational program effectiveness. Academic Medicine 65 293–296.

Kassebaum, D. G., Eaglen, R. H., & Cutler, E. R. (1997a). The objectives of medical education: Reflections in the accreditation looking glass. Academic Medicine 72(7), 648–656.

Kassebaum, D. G., Culter, E. R., & Eaglen, R. H. (1997b). The influence of accredition on educational change in U.S. medical schools. Academic Medicine 72(12 ) 1128–1133.

Kaufman, A. (1985). Implementing problem-based medical education: Lessons from successful innovations. New York: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Kaufman, A., Mennin, S., Waterman, R., Duban, S., Hansbarger, C., Silverblatt, H., Obenshain, S. S., Kantrowitz, M., Becker, T., & Samet, J. (1989). The New Mexico experiment: educational innovation and institutional change. Academic Medicine 64(6) 285–294.

Kaufmann, D. M., & Mann, K. V. (1998). Comparing achievement on the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination Part I of students in conventional and problem-based learning curricula. Academic Medicine 73(11), 1211–1213.

Lawry, G. V., Schudlt, S. S., Kreiter, C. D., Densen, P. & Albanese, M. (1999). Teaching a screening musculoskeletal examination: A randomized, controlled trail of different instructional methods. Academic Medicine 74(2), 199–201.

Lewin, L. O., Papp, K. K., Hodder, S. L., Workings, M. G., Wolfe, L., Glover, P. & Headrick, L. A. (1999). Performance of thrid-year primary-care-track students in an integrated curriculum at Case Western Reserve University. Academic Medicine 74(1Suppl), S82–89.

Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME). (1997). Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Accreditation and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education; Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the M.D. Degree. Liaison Committee on Medical Education, Washington, DC and Chicago, IL.

Martini, C. J., Veloski, J. J., Barzansky, B., Xu, G., & Fields, S. K. (1994). Medical school and student characteristics that influence choosing a generalist career. Journal of the American Medical Association 272(9), 661–668.

McAuley, R. G., & Woodward, C. A. (1984). Faculty perceptions of the McMaster M.D. program. Journal of Medical Education 59 842–843.

Medical School Objectives Writing Group. (1999). Learning objectives for medical student education. Guidelines for medical schools: Report I of the medical school objectives project. Academic Medicine 74(1), 13–18.

Mennin, S. P., & Kalishman, S. (Eds.) (1998). Issues and strategies for reform in medical education: Lessons from eight medical schools. Academic Medicine 73(9), Sept. Suppl.

Mennin, S. P., & Martinez-Burrola, N. (1985). Cost of Problem-based Learning. Chapter II in A. Kaufman (Ed.) Implementing problem-based medical education: lessons from successful innovations. New York:Springer.

Mennin, S. P., Friedman, M., Skipper, B., Kalishman, S. & Snyder, J. (1993). Performances on the NBME 1, II, and III by medical students in the problem-based learning and conventional tracks at the University of New Mexico. Academic Medicine 68(8), 616–624.

Mennin, S. P., Kalishman, S., Friedman, M., Pathak, D., & Snyder, J. (1996). A survey of graduates in practice from the University of New Mexico’s conventional and community-oriented, problem-based tracks. Academic Medicine 71(10), 1079–1089.

Moore, G. T., Block, S. D., Style, C. B., & Mitchell, R. (1994). The influence of the New Pathway curriculum on Harvard medical students . Academic Medicine. 69(12) 983–989.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods 2“ d ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Patton, M. Q. (1997). Utilization focussed Evaluation 2“ d ed. Newbury Park, Ca: Sage Publications.

Phillips, T. J., Rosenblatt, R. A., Schaad, D. C., & Cullen, T. J. (1999). The long-term effect of an innovative family physician curricular pathway on the specialty and location of graduates of the University of Washington . Academic Medicine 74 ( 3) 285–288.

Rabinowitz, H. K., Veloski, J. J., Aber, R. C., Adler, S., Ferretti, S. M., Kelliher, G. J., Mochen, E., Morrison, G., Rattner, S. L., Sterling, G., Robeson, M. R., Hojat, M., & Xu, G. (1999). A statewide-system to track medical students’ careers: the Pennsylvania model. Academic Medicine 74(Suppl 1), S112–118.

Reznick, R. K., Blackmore, D., Dauphinee, W. D., Rothman, A. I., & Smee, S. (1996). Large-scale high-stakes testing with an OSCE Report from the Medical Council of Canada Academic Medicine 71(1) S19–S24.

Rothman, A. I., Blackmore, D. E., Dauphinee, W. D., & Reznick, R. (1997). Tests of sequential testing in two years’ results of Part 2 of the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination. Academic Medicine 72(10 Suppl.l), S22–24.

Schmidt, G., Machiels-Bongaerts, M., Hermans, H., Ten Cate, Th. J., Venekamp, R., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1996). The development of diagnostic competence: comparison of a problem-based, an integrated and a conventional medical curriculum. Academic Medicine 71(6), 658–664.

Schuwirth, L. W. T., Verhoeven, B. H., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., Mom, E. M. A., Cohen-Schotanus, J., Van Rossum, H. J. M., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (1999). An inter-and intra-university comparison with short case-based testing. Advances in Health Sciences Education 4(3 ), 233–244.

Shuster, A. L., & Reynolds, R. C. (1998). Medical education: Can we do better? Academic Medicine 73(Suppl 9), Sv-Svi.

Smith, M. F. (1989). Evaluability assessment: a practical approach. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Verhoeven, B. H., Verwijnen, G. M., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., Holdrinet, R. S. G., Oeseburg, B., Bulte, J. A., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (1998). An analysis of progress test results of PBL and non-PBL students. Medical Teacher 20(4), 310–316.

Vosti, K. L., & Jacobs, C. D. (1999). Outcome measurement in postgraduate year one of graduates from a medical school with a pass/fail grading system. Academic Medicine 74(5), 547–549.

Weiss, C. H. (1998). Evaluation 2“ d ed. Toronto, ON: Prentice-Hall.

Weissert, C. S. (1999). Medical schools and state legislatures as partners in a changing policy world. Academic Medicine 74(2), 95–96.

Weissert, C. S., & Silberman, S. L. (1998) Sending a policy signal: state legislatures, medical schools, and primary care mandates. Journal of Health Politics Policy Law 23 ( 5) 743–770.

Wholey, J. S. (1977). Evaluability assessment. In L. Rutman (Ed.) Evaluation research methods: basic guide (pp. 41–56). Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Williams, R. G. (1993). Use of NBME and USMLE examinations to evaluate medical education programs. Academic Medicine 68(10), 748–752.

Woodward, C. A. (1984). Assessing the relationship between medical education and subsequent performance. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 9, 19–29.

Woodward, C. A. (1989). The effects of the innovations in medical education at McMaster: a report on follow-up studies. Medicus 2(3), 64–68.

Woodward, C. A. (1990). Developing a research agenda on career choice in medicine: a commentary. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 2(3), 139–140.

Woodward, C. A., & Ferrier, B. M. (1982). Perspectives of graduates two and five years after graduation from a three-year medical school. Journal of Medical Education 57 294–302.

Woodward, C. A., Ferrier, B. M., Cohen, M., & Goldsmith, C. (1990). A comparison of the practice patterns of general practitioners and family physicians graduating from McMaster University and other Ontario medical schools. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 2(2), 79–88.

Xu, G., & Veloski, J. J. (1991). A comparison of Jefferson Medical College graduates who chose emergency medicine with those who chose other specialities. Academic Medicine 66(6), 366–368.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

McMaster University, USA

Christel A. Woodward

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

McMaster University, Canada

Geoff R. Norman

University of Maastricht, The Netherlands

Cees P. M. van der Vleuten & Diana H. J. M. Dolmans &

University of Sheffield, UK

David I. Newble

Dalhousie University, Canada

Karen V. Mann

University of Toronto, Canada

Arthur Rothman

CurryCorp, Canada

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2002 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Woodward, C.A. (2002). Program Evaluation. In: Norman, G.R., et al. International Handbook of Research in Medical Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education, vol 7. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0462-6_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0462-6_5

Published : 05 May 2011

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-010-3904-8

Online ISBN : 978-94-010-0462-6

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Program evaluation in medical education: An overview of the utilization-focused approach

2010, Journal of educational …

Related Papers

Educational research quarterly

Robert Boruch

This scholarly commentary addresses the basic questions that underlie program evaluation policy and practice in education, as well as the conditions that must be met for the evaluation evidence to be used. The evaluation questions concern evidence on the nature and severity of problems, the programs deployed to address the issues, the programs’ relative effects and cost-effectiveness, and the accumulation of evidence. The basic conditions for the use of evidence include potential users’ awareness of the evidence, their understanding of it, as well as their capacity and incentives for its use. Examples are drawn from studies conducted in the United States and other countries, focusing on evaluation methods that address the questions above.

Archival Science

Sharon Rallis

JIm Carifio

American Journal of Public Health

Jack Meredith

Aldred Neufeldt

Douglas Horton

Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews

Abdul Wadood

Purpose of the study: This article reviews the comparative efficacy, theoretical and practical background of three program evaluation models (Stufflebeam’s CIPP model, Kirkpatrick’s model, and outcome-based evaluation models) and their implications in educational programs. The article discusses the strengths and limitations of the three evaluation models. Methodology: Peer-reviewed and scholarly journals were searched for articles related to program evaluation models and their importance. Keywords included program evaluation’, ‘assessment’, ‘CIPP model’, ‘evaluation of educational programs, ‘outcome-based model, and ‘planning’. Articles on Stufflebeam’s CIPP model, Kirkpatrick’s model, and outcome-based evaluation models were particularlyfocused because the review aimed at analysing these three models. The strengths and inadequacies of the three models were weighed and presented. Main Findings: The three models –outcome-based evaluation model, the Kirkpatric model, and the CIPP eval...

Katrina L Bledsoe

Craig McGill

Program evaluation is an essential process to program assessment and improvement. This paper overviews three published evaluations, such as reduction of HIV-contraction, perceptions of teachers of a newly adopted supplemental reading program, and seniors farmers' market nutrition education program, and considers important aspects of program evaluation more broadly. Few human resource development (HRD) scholars, professionals, and practitioners would argue that the sub-field of program evaluation is not essential to the learning and performance goals of the HRD profession. Program evaluation, a “tool used to assess the implementation and outcomes of a program, to increase a program’s efficiency and impact over time, and to demonstrate accountability” (MacDonald et al., 2001, p. 1), is an essential process to program assessment and improvement. Program evaluation (a) establishes program effectiveness, (b) builds accountability into program facilitators and other stakeholders, (c) ...

sophia epitropoulos

RELATED PAPERS

Immunology Letters

Yong Poovorawan

Journal of occupational medicine. : official publication of the Industrial Medical Association

Oscar.W.W Mote

Ilke Ceylan

Chemical Engineering Science

Corrado Sommariva

Deasy Putri Avanda Sari (C1C020176)

Chantiers de la Création

Johanna Carvajal Gonzalez

Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology

Mahsa Ansari

International Journal of Scientific Reports

Nura Abubakar

Organic Mass Spectrometry

Yves Tondeur

Serafim F S Ferraz

African Health Sciences

Hadijja Namwase

Journal of Low Temperature Physics

Kimitoshi KONO

Journal of Environmental Planning and Management

Felip Gallart

Lars Gulbrandsen

Sanat Dergisi

AURORA ROSA NECIOSUP OBANDO

Mate Puljak

LUIS DAVID CHAVEZ ESTRADA

Escola Anna Nery

Mitzy Reichembach Danski

Jurnal Teknologi Pertanian

Aulanni'am Aulanni'am

hjjgfh rgrgfgfd

Nick Willcox

International journal of economic and environment geology

Safdar A . Shirazi

JURNAL RISET KESEHATAN POLTEKKES DEPKES BANDUNG

Dewi Sodja Laela

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2019

A novel approach to the program evaluation committee

- Amy R. Schwartz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9614-1179 1 , 2 ,

- Mark D. Siegel 1 &

- Alfred Ian Lee 1

BMC Medical Education volume 19 , Article number: 465 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5766 Accesses

3 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires each residency program to have a Program Evaluation Committee (PEC) but does not specify how the PEC should be designed. We sought to develop a PEC that promotes resident leadership and provides actionable feedback.

Participants were residents and faculty in the Traditional Internal Medicine residency program at Yale School of Medicine (YSM). One resident and one faculty member facilitated a 1-h structured group discussion to obtain resident feedback on each rotation. PEC co-facilitators summarized the feedback in written form, then met with faculty Firm Chiefs overseeing each rotation and with residency program leadership to discuss feedback and generate action plans. This PEC process was implemented in all inpatient and outpatient rotations over a 4-year period. Upon conclusion of the second and fourth years of the PEC initiative, surveys were sent to faculty Firm Chiefs to assess their perceptions regarding the utility of the PEC format in comparison to other, more traditional forms of programmatic feedback. PEC residents and faculty were also surveyed about their experiences as PEC participants.

The PEC process identified many common themes across inpatient and ambulatory rotations. Positives included a high caliber of teaching by faculty, highly diverse and educational patient care experiences, and a strong emphasis on interdisciplinary care. Areas for improvement included educational curricula on various rotations, interactions between medical and non-medical services, technological issues, and workflow problems. In survey assessments, PEC members viewed the PEC process as a rewarding mentorship experience that provided residents with an opportunity to engage in quality improvement and improve facilitation skills. Firm chiefs were more likely to review and make rotation changes in response to PEC feedback than to traditional written resident evaluations but preferred to receive both forms of feedback rather than either alone

Conclusions

The PEC process at YSM has transformed our program’s approach to feedback delivery by engaging residents in the feedback process and providing them with mentored quality improvement and leadership experiences while generating actionable feedback for program-wide change. This has led to PEC groups evaluating additional aspects of residency education.

Peer Review reports

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) defines program evaluation as the “Systematic collection and analysis of information related to the design, implementation, and outcomes of a graduate medical education program for the purpose of monitoring and improving the quality and effectiveness of the program.” [ 1 ] Historical models of medical education program evaluation assumed a linear cause-and-effect relationship between program components and outcomes, with a focus on measuring predetermined outcomes. Emphasis was placed on summative evaluation to determine intervention effectiveness [ 2 ]. However, graduate medical education occurs in a complex system, in which much learning is unplanned and curricula are only one part of a dynamic program context. Graduate medical education is affected by a myriad of factors internal and external to the program, including interdisciplinary relationships, patient factors, hospital infrastructure and policies, and resource constraints.

Newer program evaluation models suggest that evaluations should capture both intended and unintended (emergent) effects of medical education programs. They emphasize looking beyond outcomes, to understanding how and why educational interventions do or do not work [ 2 ]. In an internal medicine residency context, this might include understanding both anticipated and unanticipated effects of rotation elements on learning, workflows, faculty-resident relationships, morale, and the hidden curriculum. Program evaluation can also support a focus on ongoing formative feedback to generate actionable information towards program improvement [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. In this way, the development and evaluation processes are intertwined and interdependent, promoting continuous adaptation to evolving context and needs.

There are a number of useful theoretical classifications of program evaluation. Kirkpatrick’s [ 5 ] four-level evaluation model parses program evaluation into [ 1 ] trainee reaction to the program, [ 2 ] trainee learning related to the program, [ 3 ] effects on trainee behavior, and [ 4 ] the program’s final results in a larger context. The CIPP (Context, Input, Process, and Project) evaluation model [ 6 ] divides program evaluation into four domains, [ 1 ] context evaluation, in which learner needs and structural resources are assessed, [ 2 ] input evaluation, which assesses feasibility, [ 3 ] process evaluation, which assesses implementation, and [ 4 ] product evaluation, which assesses intended and unintended outcomes. The CIPP model can be used for both formative and summative evaluations, and embraces the understanding of both predetermined outcomes and unplanned effects.

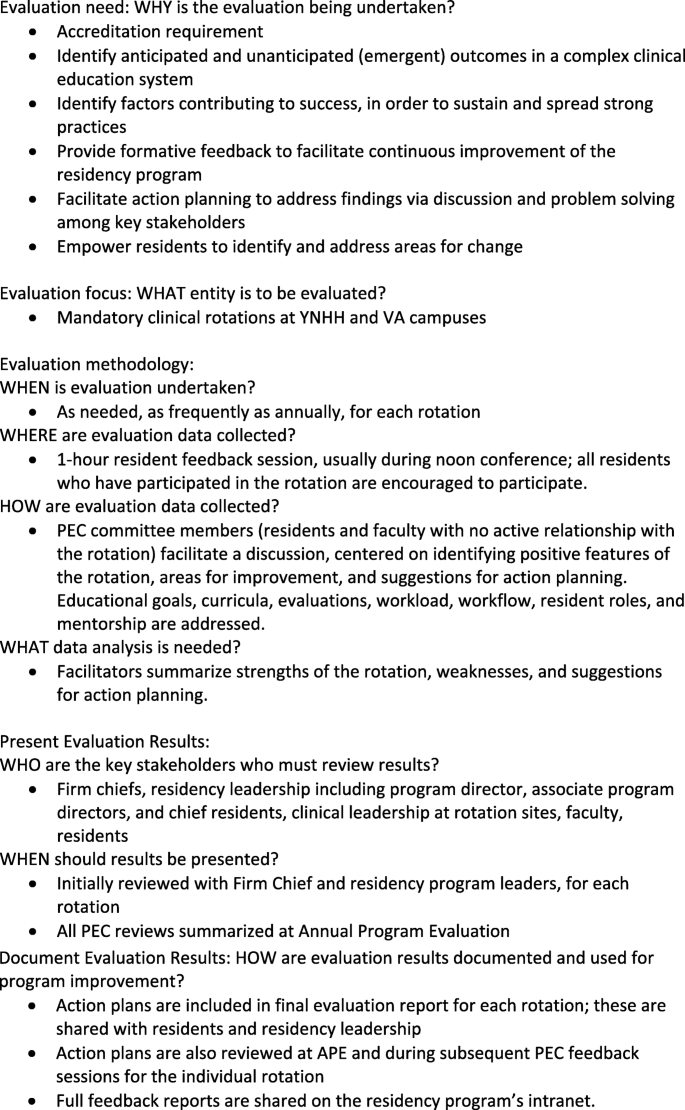

Musick [ 7 ] presents a useful, practical conceptual model of program evaluation for graduate medical education. The task-oriented model identifies five concrete steps to plan and carry out program evaluation. The first and second steps are to determine the rationale for evaluation and identify the specific entity to be evaluated. The third step involves specifying the evaluation methodology to collect and analyze data. The fourth step consists of determining to who and how results should be presented. In the fifth step, decisions are made regarding documentation of evaluation results.

Since 2014, the ACGME has required that each residency program have a Program Evaluation Committee (PEC) [ 8 ]. According to the ACGME, the PEC should participate in “planning, developing, implementing, and evaluating educational activities of the program,” “reviewing and making recommendations for revision of competency-based curriculum goals and objectives,” “addressing areas of non-compliance with ACGME standards,” and “reviewing the program annually using evaluations of faculty, residents, and others”. The program director appoints the PEC members, which must include at least one resident and two faculty. The PEC should utilize feedback from residents and faculty in the program-at-large to improve the training program and generate a written Annual Program Evaluation (APE).

The ACGME has few stipulations regarding how the PEC should carry out its duties. Several institutions have reported on data sources and structure for the APE or similar annual reviews [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. However, there is little published peer-reviewed literature regarding how training programs have designed their PECs [ 12 , 13 ]. In one published report, a general surgery program’s PEC met biannually and included 1 resident, faculty members, and program leadership [ 12 ]. Data reviewed by the PEC included surveys, resident exam performance, and clinical competency committee metrics. In another report, a psychiatry program’s PEC met every other week and examined feedback generated from monthly faculty advisor meetings, residency-wide meetings, resident evaluations, surveys, and a suggestion box, with action plans formulated by the PEC and other workgroups [ 13 ].

Historically, the Traditional Internal Medicine residency program at Yale School of Medicine (YSM) utilized an ACGME resident survey and online rotation evaluations as the primary means of soliciting feedback. While comprehensive, the evaluations were perceived by core faculty and residents as being difficult to interpret and not amenable to identifying actionable items for change. In response, the YSM Traditional Internal Medicine residency program designed an innovative approach to the PEC in which residents would have an active, meaningful role in programmatic evaluation. We hypothesized that structured resident group meetings would promote the synthesis of resident feedback and actionable suggestions, identifying key areas for programmatic improvement and offering trainees opportunities to be mentored in soliciting and giving feedback [ 14 ].

The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation [ 15 ], a coalition of North American professional associations, has developed quality standards for the evaluation of educational programs. These encompass utility, feasibility, propriety, accuracy, and accountability standards. Utility standards are intended to maximize value to stakeholders; feasibility standards to increase effectiveness and efficiency; propriety standards to support fairness and justice; accuracy standards to maximize evaluation reliability and validity; and accountability standards address documentation and evaluation of the evaluation process itself.

In developing our PEC, we sought to emphasize the utility standards of evaluator credibility, attention to stakeholders, negotiated purpose, and timely and appropriate communicating and reporting. We also sought to affirm in particular the feasibility standard of practical procedures, the propriety standard of transparency and disclosure, and the accountability standard of internal meta-evaluation.

Research design

We devised and implemented a novel structure for the YSM Traditional Internal Medicine residency PEC, in which residents led structured group discussions involving other residents, with the purpose of evaluating each of the inpatient and outpatient teaching firms in our training program. Over a 4-year period, we compiled actionable feedback arising out of the PEC focus group discussions, and we surveyed PEC residents and teaching faculty to assess perceptions of the PEC process.

Setting and participants

The YSM Traditional Internal Medicine residency program consists of 124 internal medicine and 14 preliminary residents. Inpatient and outpatient rotations are divided into firms, each overseen by a member of the core teaching faculty who is given a designated title of “Firm Chief.” Most rotations occur on two campuses: Yale-New Haven Hospital (YNHH) and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System. Seventeen rotations are reviewed by the PEC: 10 inpatient firms at YNHH, three inpatient firms at the VA, and four outpatient clinics.

Program description

A Task-Oriented Conceptual Model [ 7 ] of the YSM Traditional Internal Medicine Residency PEC is shown in Fig. 1 . Feedback is obtained from resident group discussions facilitated by residents and faculty who serve on the PEC. All residents in the Traditional Internal Medicine residency program and preliminary interns are invited to join the YNHH or the VA PEC as committee members. At the start of each academic year, the PEC determines which rotations require review for the year, ensuring that all rotations are reviewed on a regular basis and that rotations undergoing or in need of change are reviewed. During the first year of the PEC initiative, all inpatient and outpatient rotations at YNHH and the VA were designated for formal review by the PEC; rotations in which the PEC process identified deficits requiring systematic change were then selected for repeat review by the PEC over subsequent years. The total follow-up period for this study is 4 years.

Task-Oriented Conceptual Model of the YSM Traditional Internal Medicine Residency PEC

Each rotation is assigned a resident-faculty pair in which a PEC resident evaluates the rotation under supervision by a designated faculty member. In every instance, PEC faculty facilitators assigned to review a specific rotation have no active relationship with that rotation. A 1-h group resident feedback session is held for each rotation, generally during the noon conference time; all residents are encouraged to participate. The assigned PEC resident is responsible for facilitating the discussion utilizing a structured format centered on four questions:

What are the positive features of this rotation?

What are areas for improvement?

What features should be adopted on other rotations?

What aspects should be changed, and how?

Prior to the group discussion, the PEC resident assigned to review the rotation is encouraged to engage with the appropriate Firm Chief to identify specific areas to focus on for feedback. During the group discussion, the PEC facilitators ensure that educational goals, curricula, evaluations, workload, workflow, resident roles, and mentorship are addressed, and that resident anonymity is preserved. After the discussion, the PEC facilitators compile additional email feedback from residents who were unable to attend the group discussion, summarize the feedback in a written document, and meet with the Firm Chief in addition to other residency program leadership and teaching faculty to deliver the feedback. The PEC facilitators, Firm Chief, and program leadership together develop an action plan, and the written feedback is submitted to the program and reviewed at the APE.

Data collection

We collected two types of data during the 4-year study period: [ 1 ] summative evaluations of individual inpatient and outpatient rotations generated by the PEC process, and [ 2 ] resident and faculty perceptions of the PEC process. Summative evaluations of the different rotations were obtained from the written documents created by the PEC residents upon completing their evaluations of individual firms, and from the action plans created by the PEC facilitators, Firm Chiefs, and program leadership. Resident and faculty perceptions of the PEC process were gauged using surveys.

Survey design

We sought to understand how feedback obtained by the PEC process was perceived and acted upon by faculty Firm Chiefs in comparison to written surveys. We also wanted to understand how residents and faculty participating on the PEC perceived the PEC process and whether such participation had an impact on resident/faculty mentorship, delivering feedback, or facilitating small group discussions. To assess for these factors, the PEC faculty designed two surveys, one for faculty Firm Chiefs, the other for PEC residents and faculty, aimed at addressing these questions. Survey questions were proposed, drafted, discussed, and edited by faculty members of the PEC. Content validity of the surveys was assessed by one coauthor (M.D.S.) who was involved in the design and implementation of the PEC process but not in the initial generation of survey questions. The surveys were tested on 3 YSM faculty and further modified according to their feedback, with the revised surveys incorporating simplified “Yes/No” response options and multiple prompts for free text responses. The final surveys were distributed electronically using SurveyMonkey to all faculty Firm Chiefs and PEC faculty and resident members in 2016 and 2018 after completion of the second and fourth years, respectively, of the project [ 16 ].

Data analysis

For each inpatient and outpatient rotation, major recommendations were compiled from the written documents created by PEC residents and from the action plans created by PEC facilitators, Firm Chiefs, and program leadership. For the 2016 and 2018 surveys of PEC residents and Firm Chiefs, response rates and responses to “Yes/No” and free-text questions were analyzed. The small sample size of the study population precluded statistical analysis of any answers to survey questions. The free text responses for both surveys were independently reviewed by two authors (ARS and AIL) according to Miles and Huberman [ 17 ]; themes emerging from these responses were identified and analyzed for repetitive patterns and contrasts. The two investigators then met to discuss the themes; at least 80% agreement on themes was achieved, with discrepancies resolved by consensus discussion. The exact survey instruments are shown in Additional file 1 (survey of faculty Firm Chiefs) and Additional file 2 (survey of PEC member residents and faculty).

During the course of four academic years (2014–15 through 2017–18), 40 residents and 14 faculty (including chief residents) participated as PEC facilitators.

PEC findings

Over the 4-year study period, the PEC process generated a number of specific points of feedback on every inpatient and outpatient rotation. At both the YNHH and VA campuses, numerous services were lauded for their outstanding educational experiences and other positive attributes. Many suggestions for change were able to be implemented over subsequent years. Summaries of positive features, recommended changes, and feedback implementation after the first year of the PEC initiative are shown in Table 1 (YNHH) and Table 2 (VA Hospital).

While many of the PEC’s findings were unique to individual rotations, several common themes emerged in PEC feedback reports for multiple rotations. Frequently cited strengths included:

Caliber of teaching. Residents described a high caliber of precepting and teaching by ward and clinic attendings on the majority of inpatient and outpatient rotations. Examples include, “quality of attending rounds is phenomenal, caters to resident, intern, and med student levels,” “the VA MICU is a great place to get to know your attending very well, develop mentors, get career advice, and get very specific, day to day feedback,” “attendings at the VA are amazing life mentors … and are very optimistic with strong passion and enthusiasm for work that is contagious,” and “both women’s clinic preceptors were excellent mentors, approachable, very good teachers.”

Patient care. Residents found their inpatient and ambulatory patient care experiences to be highly diverse and of great educational value. Examples include, “the high clinical volume, complicated patients, and new patient evaluations were noted as maximizing educational value on this rotation,” “enjoyed having the experience of being a consultant,” “amazing VA patient population … it is quite an honor to serve them and to learn specific military and exposure histories,” and “sufficient diversity of diseases … many bread and butter cases as well as multiple different specialty cases.”

Interdisciplinary care. Residents encountered a strong emphasis on interdisciplinary care across many services, which improved the quality of care delivered. Examples include, “incorporating other clinicians (APRNs, pharmacists, health psych [ology]) into daily work flow helps with management of difficult patients,” “exceptionally comprehensive multidisciplinary set-up,” “case management rounds are very efficient,” and “nurses are helpful, informative.”

Common areas for improvement included:

Didactics. On several rotations, residents identified a need to optimize the orientation process and to streamline or improve availability of educational curricula. For example, “residents are unclear of the goals for specific immersion blocks,” “there is currently no curriculum to guide independent study. Attending rounds have not been a feature of the rotation,” “would like more women’s health didactics during educational half days,” and “some teams sat down and defined their learning goals and career interests the first day of the rotation … it would be great if this process became standard for all teams.”

Interactions with other services. Residents identified needs for improvement in communication with nursing staff, utilization of specialty services, and navigation of disposition decisions between services. For example, “very difficult to obtain imaging studies overnight,” “medicine appears to be the default service to admit to … there is a concern that some patients could benefit and be managed better from being on the specialty service,” and “very difficult to reach [several services].”

Technological issues. Residents found problems with the paging system and with computer or identification badge access on some rotations. For example, “residents proposed making access easier to the Psychiatry ER and [psychiatry] inpatient units, such as by granting this access on their VA identification card,” “some residents reported consistent glitches in home access,” “sometimes the pagers do not work due to dead zones. It would be helpful to move to a phone or otherwise more reliable electronic system,” and “[confusing] charting of ED medications.”

Workflow. Residents identified problems with call schedules, admitting algorithms, and balance between teaching and service on certain rotations. Examples include, “clinic work flow is inefficient … .geographic barriers (clinic is very far from check in and the waiting room) and poor staffing,” “if patients are already signed out to be admitted to the floor but are still physically present in the ED … .residents found it challenging to manage … because of the distance between the medicine floors and the ED,” “imbalanced admission loads on different admitting days due to diversion,” and “social admissions and observation patients accounted for a large number of their census.”

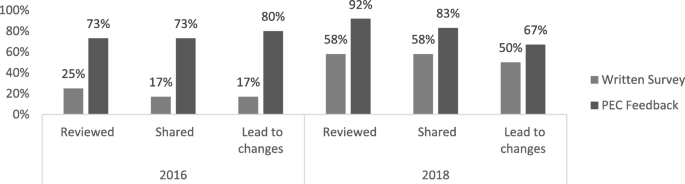

Evaluation of the PEC

To understand how feedback obtained by the PEC was viewed and utilized, we designed a survey, sent to all Firm Chiefs, which asked whether PEC feedback was reviewed and shared with other faculty or administrators, and whether the PEC process led to changes in the rotation. The same questions were asked about traditional written evaluations filled out by residents. Surveys were sent to a total of 16 Firm Chiefs in 2016 and 17 in 2018; response rates for each survey were 75 and 71%, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2 , in both years, Firm Chiefs reviewed, shared, and responded with change to feedback obtained from the PEC with greater frequency than that obtained from written resident evaluations. Firm Chiefs preferred to receive feedback from both the PEC and written evaluations rather than only the PEC or only written evaluations alone (for 2016: 90.9, 9.1, and 0%, respectively; for 2018: 50, 33, and 17%, respectively).

Comparison of written surveys vs. PEC feedback by Firm Chiefs in 2016 and 2018. For 2016, a greater number of Firm Chiefs reviewed, shared, and responded to feedback generated by the PEC than by written surveys; all of these differences were statistically significant ( p = 0.04, 0.01, and 0.01, respectively). For 2018, a greater number of Firm Chiefs reviewed, shared, and responded to PEC vs. written survey data but these findings were not statistically significant ( p = 0.16, 0.37, and 0.40, respectively)

To understand how PEC participants viewed their experiences participating in and contributing to the PEC process, we also designed a survey, sent to all resident and faculty PEC members, which asked about their perspectives on the utility of the PEC process and whether participation in the PEC led to resident-faculty mentoring relationships and improvement in skills of facilitating and delivering feedback. Surveys were sent to a total of 26 PEC members in 2016 and 25 in 2018; response rates for each survey were 69 and 80%, respectively. Across both years, 84% of survey respondents indicated that their experiences with the PEC improved their feedback skills. The majority of respondents developed a mentoring relationship as a result of the PEC. Committee members were also asked to provide written commentary regarding the feedback process; major themes as identified using content analysis are shown in Table 3 (with representative comments):

Expansion of the PEC

As a result of the PEC’s ability to identify actionable feedback for change, in the years following the PEC’s inception, residents in the Traditional Internal Medicine program at YSM adopted the PEC format not only for continued assessment and optimization of inpatient and outpatient firms but also for examination of a number of broad residency domains such as educational conferences, call structures, and evaluations. During the 2015–2016 academic year, several residents created a PEC subgroup focused on medical education, which used structured group discussions and surveys to identify several areas for potential change; as a result of this effort, a noon conference committee was convened in the 2018–2019 academic year that completely redesigned the noon conference series for the year. During the 2018–2019 academic year, the PEC group again utilized structured group discussions and surveys to evaluate resident perceptions of hospital rotations with a 28-h call schedule, leading to the creation of a 28-h call working group to restructure those services. PEC residents also undertook formal evaluations of the residency program’s leadership (including chief residents, associate program directors, and the program director) using the same PEC format for eliciting verbal group and written feedback.

Many residents also indicated a need for the PEC to better inform the program-at-large regarding PEC findings and action plans. In response to this, in 2018 the PEC began posting its feedback reports on our residency program’s intranet. Going forward, the PEC will also look to identify more robust processes for follow-up of action plans, and to align the PEC feedback process with other ongoing quality improvement initiatives (i.e. resident team quality improvement projects, chief resident for quality and safety interventions).

Over the course of four years, the PEC for the YSM Traditional Internal Medicine residency program transformed the process by which feedback is obtained from residents and delivered to educational leadership. We emphasized the role of residents in facilitating, synthesizing, and delivering feedback. Compared to written evaluations, feedback generated by the PEC was more likely to be reviewed and responded to by Firm Chiefs. Residents and faculty who participated in the PEC generally found that their experiences improved their feedback skills, and many participants developed resident-faculty mentoring relationships. The success of our approach to the PEC led to the development and implementation of additional projects to expand the PEC’s scope.

Firm Chiefs preferred to obtain feedback from both the PEC and written surveys rather than either one alone. Focus groups and written surveys are complementary tools; written surveys provide quantitative data, while group discussions provide qualitative data that allow for brainstorming, synthesis, and prioritization. Implementation of PEC discussion groups cannot entirely supplant surveys, as the ACGME requires that residents have the opportunity to evaluate the program anonymously in writing.

In the Firm Chief surveys, between 2016 and 2018, there was an apparent rise in the percentage of Firm Chiefs who made use of written surveys across the two years. It is possible that this may reflect an increase in awareness and/or accessibility of the results of the written surveys during this time period, although some of the differences may alternately reflect the small number of respondents. The 2016 and 2018 Firm Chief surveys also showed an interval decline in the percentage of Firm Chiefs who responded with change to feedback obtained from the PEC, which could be due to a diminishing need to launch systematic changes when actionable feedback is being regularly obtained.

Newer program evaluation models [ 2 ], including the CIPP model [ 6 ], focus on understanding the complex educational system, assessing unanticipated outcomes, and formative evaluation. Findings from our PEC rotation evaluations reflected this complexity in graduate medical education, in which learning and the trainee experience are affected by many factors internal and external to the program. We found that open-ended discussions focused on rotation strengths and areas for improvement allowed for reflection on unanticipated outcomes (i.e. communication issues with other services, lack of standardization of patient transitions, slow patient workflows, and imbalanced workloads), as well as those more directly related to the curriculum (i.e. need for improvements in orientation and curricula). This approach also facilitated identification of best practices and ideas for sustainment and spread. The emphasis on formative feedback allowed us to identify actionable items for change, conduct bi-directional discussions among stakeholders, and participate in the iterative improvement of the program.

Standards for evaluation of educational programs include the dimensions of utility, feasibility, propriety, accuracy, and accountability [ 15 ]. We sought to maximize utility via the values of evaluator credibility (residents and faculty both have an active leadership and facilitation role, PEC committee members have no relationship with the rotation that they review); attention to stakeholders (residents, faculty, program leadership, and firm chiefs are involved in assessment and action planning); negotiated purpose (discussion with firm chiefs regarding areas of desired feedback, focus on helping medical educators optimize education and clinical care); and timely and appropriate communicating and reporting (stakeholder meetings regarding action planning, written documentation of feedback and action plans, reporting via APE meeting, email, and intranet.) We sought to emphasize the feasibility standard of practical procedures (use of available conference time resources, meeting in locations easily accessible to residents). We asserted the propriety standard of transparency and disclosure by making full reports available to stakeholders. Our periodic structured inquiry to PEC members and firm chiefs regarding their experience and needs sought to satisfy the accountability standard of internal meta-evaluation.

There are several limitations to our study. We took a participant-oriented approach that sought to determine how trainees experienced their rotations [ 3 ]. However, this limited us to level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s program evaluation model [ 5 ], trainee reaction, and did not directly assess learning, behavior, or clinical outcomes. Ultimately, we found that our PEC approach was most effective when used as a supplement to many other measures considered at our APE, including board scores, fellowship and career information, and Faculty and Resident ACGME surveys. Another limitation is the focus on the experience of resident stakeholders; however, we made this choice due to a perceived need for resident input by program leadership. Faculty and other stakeholder input is also considered at both the APE and individual rotation action planning meetings. Additional limitations of our study include generalizability, as successful implementation at our program may reflect the institutional culture or other elements specific to our program; and the small numbers of Firm Chiefs and committee members in a single training program. Also, the feedback obtained during resident group discussions is dependent on the quality of the facilitation and level of resident engagement.

In conclusion, we created an innovative format for the PEC, consisting of structured resident discussions led by resident-faculty facilitators. These are synthesized to generate actionable feedback for each rotation. Feedback is presented in person to Firm Chiefs, concrete action plans created, and residency and clinical leadership alerted to rotation strengths and areas for improvement. Our PEC experience has had a sustained and transformative impact on the feedback process for our residency program.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

Annual Program Evaluation

Context Input Process Product

Program Evaluation Committee

Veterans Affairs

Yale-New Haven Hospital

Yale School of Medicine

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Glossary of Terms. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/ab_ACGMEglossary.pdf?ver=2018-05-14-095126-363 Accessed Oct 17 2019.

Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach. 2012;34:e288–99.

Article Google Scholar

Cook DA. Twelve tips for evaluating educational programs. Med Teach. 2010;32:296–301.

Haji F, Morin M-P, Parker K. Rethinking programme evaluation in health professions education: beyond ‘did it work?’. Med Educ. 2013;47:342–51.

Kirkpatrick D. Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s four-level model. Train Dev. 1996;1:54–9.

Google Scholar

Stufflebeam DL. The CIPP Model for Evaluation. In: Kellaghan T, Stufflebeam DL, editors. International Handbook of Educational Evaluation. Kluwer International Handbooks of Education, vol 9. Dordrecht: Springer; 2003.

Musick DW. A conceptual model for program evaluation in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2006;81:759–65.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Amedee RG, Piazza JC. Institutional oversight of the graduate medical education enterprise: development of an annual institutional review. Ochsner J. 2015;16:85–9.

Rose SH, Long TR. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual anesthesiology residency and fellowship program review: a “report card” model for continuous improvement. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:13.

Nadeau MT, Tysinger JW. The annual program review of effectiveness: a process improvement approach. Fam Med. 2012;44:32–8.

Deal SB, Seabott H, Chang L, Alseidi AA. The program evaluation committee in action: lessons learned from a general surgery residency’s experience. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:7–13.

Erickson JM, Duncan AM, Arenella PB. Using the program evaluation committee as a dynamic vehicle for improvement in psychiatry training. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:200–1.

Rucker L, Shapiro J, Fornwalt C, Hundal K, Reddy S, Singson Z, Trieu K. Using focus groups to understand causes for morale decline after introducing change in an IM residency program. BMC Medical Educ. 2014;14:132.

Yarbrough DB, Shulha LM, Hopson RK, Caruthers FA. The program evaluation standards: a guide for evaluators and evaluation users. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011.

SurveyMonkey. http://www.surveymonkey.com . Accessed 4 June 2018.

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd ed. SAGE: Thousand Oaks; 2014.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge all the residents and faculty members who have ably served on the PEC. We also wish to acknowledge the YSM residents who gave feedback during the PEC sessions, and the Firm Chiefs who were eager to receive feedback and continuously improve their rotations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT, 06510, USA

Amy R. Schwartz, Mark D. Siegel & Alfred Ian Lee

VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Primary Care, Firm B, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, CT, 06516, USA

Amy R. Schwartz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ARS drafted the manuscript and acquired and analyzed the data. AIL drafted the manuscript and acquired and analyzed the data. MDS substantively revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study conceptualization and design and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amy R. Schwartz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Yale University Human Investigation Committee determined that this project is quality improvement, not requiring IRB review, on 2/26/19. Because participation was voluntary and occurred in the course of normal educational activities, written informed consent was considered unnecessary.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

2018 PEC Survey – Firm Chiefs. Text of electronic survey to assess firm chief perceptions of PEC Feedback.

Additional file 2.

2018 PEC Survey – Committee Members. Text of electronic survey to assess committee member experiences on the PEC.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Schwartz, A.R., Siegel, M.D. & Lee, A.I. A novel approach to the program evaluation committee. BMC Med Educ 19 , 465 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1899-x

Download citation

Received : 10 May 2019

Accepted : 04 December 2019

Published : 16 December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1899-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Program evaluation

- Medical education – graduate

- Medical education – qualitative methods

- American council of graduate medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lippincott Open Access

Program Evaluation in Health Professions Education: An Innovative Approach Guided by Principles

Dorene f. balmer.

1 D.F. Balmer is professor, Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and director of research on education, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6805-4062 .

Hannah Anderson

2 H. Anderson is research associate, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Daniel C. West

3 D.C. West is professor and associate chair for education, Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and senior director of medical education, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0909-4213 .

Program evaluation approaches that center the achievement of specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound goals are common in health professions education (HPE) but can be challenging to articulate when evaluating emergent programs. Principles-focused evaluation is an alternative approach to program evaluation that centers on adherence to guiding principles, not achievement of goals. The authors describe their innovative application of principles-focused evaluation to an emergent HPE program.

The authors applied principles-focused evaluation to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Medical Education Collaboratory, a works-in-progress program for HPE scholarship. In September 2019, the authors drafted 3 guiding principles. In May 2021, they used feedback from Collaboratory attendees to revise the guiding principles: Advance Excellence , Build Bridges , and Cultivate Learning .

In July 2021, the authors queried participants about the extent to which their experience with the Collaboratory adhered to the revised guiding principles. Twenty of the 38 Collaboratory participants (53%) responded to the survey. Regarding the guiding principle Advance Excellence , 9 respondents (45%) reported that the Collaboratory facilitated engagement in scholarly conversation only by a small extent, and 8 (40%) reported it facilitated professional growth only by a small extent. Although some respondents expressed positive regard for the high degree of rigor promoted by the Collaboratory, others felt discouraged because this degree of rigor seemed unachievable. Regarding the guiding principle Build Bridges , 19 (95%) reported the Collaboratory welcomed perspectives within the group. Regarding the guiding principle Cultivate Learning , 19 (95%) indicated the Collaboratory welcomed perspectives within the group and across disciplines, and garnered collaboration.

Next steps include improving adherence to the principle of Advancing Excellence , fostering a shared mental model of the Collaboratory’s guiding principles, and applying a principles-focused approach to the evaluation of multi-site HPE programs.

Achievement of specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound (SMART) goals is commonly used as a criterion for judging the value or effectiveness of programs in health professions education (HPE). 1 – 3 Although SMART goals are useful in program evaluation, articulating SMART goals can be challenging when evaluating emergent or novel programs. In these situations, program leaders may have a general sense of what matters and what they want to accomplish, but exactly how they will accomplish that is unclear and may shift as the program evolves.

Patton’s 4 principles-focused evaluation is an alternative to goal-oriented program evaluation. It uses adherence to guiding principles, not achievement of goals, as the criterion for judging the value or effectiveness of a program. Guiding principles may be defined as “statements that provide guidance about how to think or behave toward some desired result, based on personal values, beliefs, and experience.” 4 (p9) In the context of program evaluation, Patton recommends that the guiding principles be (1) guiding (provide guidance and direction), (2) useful (inform decisions), (3) inspiring (articulate what could be), (4) developmental (adapt over time and contexts), and (5) evaluable (can be documented and judged). 4 , 5 Thus, notable differences exist between the use of guiding principles versus SMART goals as criteria for making judgments about a program. Guiding principles offer a values-informed sense of direction toward outcomes that are difficult to quantify and frame by time (Table (Table1). 1 ). In addition, guiding principles are aspirational, whereas SMART goals explicate what is feasible to achieve.

Contrasting SMART Goals and Principles-Focused Evaluation a

We argue that adhering to guiding principles, while being flexible and open to how to realize those principles, may foster creativity in HPE programs. The use of guiding principles may also prevent premature closure when making judgments about the value or effectiveness of a program. As with false-negative results, program leaders could conclude that their program was not effective if SMART goals were not achieved (e.g., if only 10% of participants had at least 1 peer-reviewed publication within 12 months of completing the faculty development program and not the specific goal of > 20% of participants). However, with principles-focused evaluation, program leaders could conclude that the same program was effective because guiding principles were honored (e.g., participants routinely referred to the faculty development program as “my people” or “home base,” which indicates that the program adhered to the guiding principle of creating community).

To our knowledge, guiding principles have not been used for evaluating HPE programs, although they have been used for designing and implementing HPE programs. 6 , 7 To address this gap, we describe an innovative approach to program evaluation—principles-focused evaluation—and our application of this innovative approach to an emergent program in HPE.

Developing the program and crafting guiding principles

In 2019, we developed the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Medical Education Collaboratory (Collaboratory), a works-in-progress program for HPE scholarship. The Collaboratory was designed to be a forum for faculty, staff, and trainees to present scholarly projects and receive constructive feedback and a gathering place for them to learn from the scholarly projects of their peers.

To craft guiding principles, we reviewed existing documents from a 2017 visioning meeting attended by committed health professions educators at CHOP. Documents included statements about what educators valued, believed in, and knew from their own experience at CHOP. We met 3 times from September to November 2019 to review documents and inductively derive guiding principles. Our initial guiding principles were to Advance Excellence , Build Capacity , and Encourage Collaboration (Figure 1). We edited these initial principles based on Patton’s guidelines so that they fit the purpose of program evaluation when program value or effectiveness is judged based on adherence to principles. 4 In operationalizing the program, we routinely shared our guiding principles via email announcements about the Collaboratory and verbally at Collaboratory sessions at the start of each semester. We sought approval from CHOP’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, which deemed our project exempt from review.

Implementing and improving the program

We remained cognizant of our guiding principles as we implemented the Collaboratory in January 2020 and made program improvements over time. For example, we iteratively adapted the schedule of Collaboratory sessions to best fit the needs of our attendees and presenters from across CHOP by shifting from 2 presenters to 1 presenter per 60-minute Collaboratory and adding an early evening timeslot. We also revised presenter guidelines to maximize time for discussion (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B345 ). When pandemic restrictions prohibited face-to-face meetings, we shifted to video conferencing and took advantage of virtual meeting features (e.g., using the chat feature to share relevant articles).

This study was approved as exempt by the CHOP Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

We report outcomes of our innovation—application of principles-focused evaluation to program evaluation—in 2 respects. First, we consider our revision of guiding principles as outcomes. Second, we provide evidence of our adherence to those guiding principles.

Revised guiding principles

In May 2021, after 3 semesters of implementation and iterative improvements, we launched our principles-focused evaluation of the Collaboratory. Specifically, we asked, “Are we adhering to our guiding principles?” We started to address that question by sharing descriptive information (e.g., number of sessions, number attendees) and initial guiding principles with attendees of an end-of-semester Collaboratory and eliciting their ideas for program improvement. On the basis of their feedback and aware of a new venue to build community among physician educators, we scaled back on our intention to build capacity and instead focused on building collaboration. We were struck by perceptions that the forum had become a safe space for learning and wanted to incorporate that in our guiding principles. Thus, we revised our guiding principles to Advance Excellence , Build Bridges , and Cultivate Learning (Figure (Figure1 1 ).

Initial and revised guiding principles of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Medical Education Collaboratory (Collaboratory), with an example of GUIDE (guiding, useful, inspiring, developmental, evaluable) criteria 4 for one guiding principle.

Then, we constructed a survey to query Collaboratory attendees and presenters about the extent to which the Collaboratory adhered to the revised guiding principles. The survey was composed of 7 items rated on a 4-point scale, with 1 indicating not at all and 4 indicating a great extent, and corresponding text boxes for optional open-ended comments (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B345 ). Survey items were crafted from language of the guiding principles, which were informed by feedback from attendees of the end-of-semester Collaboratory, but the survey itself was not pilot tested.

To further address our evaluation question, we administered the survey via email to past presenters (n = 13) and attendees (n = 25) at the Collaboratory in July 2021. We received 20 unique responses, 9 from presenters and 11 from attendees for a response rate of 53% (n = 20/38). We analyzed quantitative data descriptively, calculating percentage of responses for each item. We categorized qualitative data from open-ended comments by guiding principle and reviewed these data for evidence of alignment with principles. Results for each item can be found in Figure Figure2 2 .