- Warning Signs and Symptoms

- Mental Health Conditions

- Common with Mental Illness

- Mental Health By the Numbers

- Individuals with Mental Illness

- Family Members and Caregivers

- Kids, Teens and Young Adults

- Veterans & Active Duty

- Identity and Cultural Dimensions

- Frontline Professionals

- Mental Health Education

- Support Groups

- NAMI HelpLine

- Publications & Reports

- Podcasts and Webinars

- Video Resource Library

- Justice Library

- Find Your Local NAMI

- Find a NAMIWalks

- Attend the NAMI National Convention

- Fundraise Your Way

- Create a Memorial Fundraiser

- Pledge to Be StigmaFree

- Awareness Events

- Share Your Story

- Partner with Us

- Advocate for Change

- Policy Priorities

- NAMI Advocacy Actions

- Policy Platform

- Crisis Intervention

- State Fact Sheets

- Public Policy Reports

- Your Journey

Youth and Young Adult Resources

Mental health conditions typically begin during childhood, adolescence or young adulthood. Here you will find additional information intended to help provide young people, educators, parents and caregivers with the resources they need. From a free downloadable coloring and activity book to a teen mental heath education presentation, to a guide for navigating college with a mental health condition, this page has resources for all young people. It also has handy information for parents, caregivers, and educators, like a one-pager on how to start a conversation about mental health and an example week of wellness activities that can be used at home.

For Young People

Meet Little Monster Coloring & Activity Book

Created by NAMI Washington, Meet Little Monster is a mental health coloring and activity book that provides children with a tool for helping express and explore their feelings in a fun, creative and empowering way. Available for download at no-cost in multiple languages. Learn More

Teens and Young Adults

Commitment Planner

A resource to help students balance their school, work and personal time to help their mental well-being! Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Finding A Trusted Adult

Reaching out about mental health can be or feel overwhelming, embarrassing or just hard. Use this guide to help you choose someone to confide. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Getting the Right Start

A one-pager that makes taking the first steps to asking for help less overwhelming Download Resource

How to Help a Friend

A one-pager that gives suggestions on how to support a friend struggling with a mental health condition Download Resource

How Young Adults Can Seek Help

A video on where and how you can find the help and support you need for a mental health condition. Watch Video

How Teens Can Ask for Help

A video on who to reach out to and ways to put your thoughts and feelings into words to receive help for a mental health condition. Watch Video

NAMI On Campus Club

NAMI On Campus clubs are student-led, student-run mental health clubs for colleges and high schools. Learn more on how you can become a part of the national movement and make meaningful change on your campus. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish Learn More

NAMI Say It Out Loud

Created by young people for young people, NAMI Say It Out Loud is a free online card game that will bring you closer to your friends through conversation prompts about life, relationships, and mental health. Play Now

NAMI Teen & Young Adult Resource Directory

NAMI HelpLine volunteers and staff have compiled this directory of outstanding resources to help teens and young adults identify resources to meet their mental health needs. If you or someone you know are in need, use this directory as a guide to help navigate through your mental health journey. Download Resource Directory NAMI does not endorse the resources included in the NAMI TYA HelpLine Resource Directory, and NAMI is not responsible for the content of or service provided by any of these resources.

Teen and Young Adult Mental Health Resources

A set of social media graphics to start a conversation with your community about mental health check-ins, mental health game plans and our four-day gratitude challenge. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish Download Resource Graphics

Time Management

Use these tips to balance your school, work and personal time to help your mental well-being! Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

College Students

Language Matters

A one-pager that helps individuals understand the importance of words when talking about mental health conditions and suicide Download Resource

Making A Mental Health Plan For College Students

In this video, learn how to prepare for a mental health emergency, including how to safely share medical information with someone you trust. Watch Video

Mental Health College Guide

Created in partnership with The JED Foundation, the College Guide is a one stop online resource to help young adults navigate the many situations encountered when in this new and exciting environment Learn More

Positive Coping Skills

Do you have a mental health toolkit? In this video, NAMI volunteer Britt shares what positive coping skills are and how to develop a mental health toolkit so that we don’t fall into negative coping strategies. Additionally, she discusses what specific skills help her cope. Watch Video

Setting Boundaries

Setting healthy limits, or boundaries, in our lives allows us to take care of our health and well-being. In this resource, we’ll cover different types of boundaries, how to set them and ways to communicate to others what you will and will not allow to protect yourself and take charge of your life. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Social Media

Social media can be a great way to connect with friends, family and your community. Learn how to engage safely and protect your mental health. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

External Resources

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

Digital Shareables on Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Resources from Alliance for a Healthier Generation

- Quality Time in No Time: Quick and Simple Ways to Make Family Time More Meaningful (Collaboration with Blue Star Families)

- Ways to Keep Active Together (Collaboration with President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition, GoNoodle®️, and Griffin Middle School)

- How to Foster Self-Awareness when Challenging Emotions Arise (Collaboration with AAPI Youth Rising and Act to Change))

For Educators

Classroom Mental Health Contract

An activity guide to help students develop an understanding of mental health and identify supports available for them inside the classroom and at school. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Five Questions for School Staff to Ask When Preparing for An Active Shooter Drill

Resources for building a trauma-informed active shooter drill in schools. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

A one-pager that helps individuals understand the importance of words when talking about mental health conditions and suicide. Download Resource

Mental Health & Wellness Moments for Educators

An activity guide for educators to incorporate daily wellness activities in the classroom to enhance the emotional well-being of their students. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Mindfulness

Often, in school, students can find it hard to focus or can be impacted by events around them. You can use these exercises to bring students back into the moment. Download for Elementary Download for Middle & High Download Resource in Spanish

NAMI Ending the Silence

NAMI Ending the Silence is an engaging presentation that helps middle and high school aged youth learn about the warning signs of mental health conditions and what steps to take if you or a loved one are showing symptoms of a mental health condition. Learn More

NAMI Ending the Silence is offered in-person by NAMI affiliates across the country and is also now available online when an in-person presentation is not available.

School Mental Health Resource Poster

School Mental Health Resource Poster (black and white)Teachers can help students access vital mental health resources easily and confidentially with this convenient poster. Students can tear away important mental health resource information or scan the QR code to save contacts directly into their phones. NAMI recommends pre-cutting the tear aways at the bottom and tearing off the first one to relieve the pressure of any student being the first to take one. Download Resource Download in Black and White

Supporting Back to School Wellness

A one-pager with a few tips for teachers on how to make students’ transition back to the classroom a little bit easier during these uncertain times. Download Resource

The Three C’s for Educators

A one-pager with tips for educators on supporting their student’s emotional and mental well-being during the transition back to school and throughout the school year! Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Three Keys For a Successful Back-to-School Transition

Resources for educators to create a safe and supportive classroom. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

For Parents and Caregivers

10 Questions on a Tuesday

An activity guide for parents and guardians to discuss mental health and well-being with their children in the home and develop supportive practical strategies. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Bullying Warning Signs

Bullying is a concern with children of all ages. Know how to spot the warning signs and how to start a conversation with your child about bullying. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Creating Positive Change & Back to School Mental Health Tips

A nationwide iHeartRadio special, hosted by Ryan Gorman that includes Barbara Solish, director of youth and young adult initiatives at NAMI, discussing resources and help available for children, teens and young adults faced with the hardship of the pandemic and remote learning. The NAMI segment starts at minute marker 14:47. Listen Now

Crisis & Relapse Plan

Fill out this template to help your family and support team in the event of a crisis or relapse. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Finding Mental Health Care for Your Child

A video that describes what to do and where to go for help when your child shows symptom of a mental health condition Watch Video

How To Be A Trusted Adult

An activity guide for parents and caregivers to explain who is a “trusted adult” and tips on how to become one. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

NAMI Basics

NAMI Basics is a six-session education program for parents, caregivers and other family who provide care for youth (ages 22 and younger) who are experiencing mental health symptoms. This program is free to participants, 99% of whom say they would recommend the program to others. NAMI Basics is available both in person and online through NAMI Basics OnDemand . Learn More

Suicide Warning Signs

Learn the warning signs, learn how to start a conversation and know what to do in a mental health crisis. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

The Three C’s for Parents and Guardians

A one-pager with tips for parents on supporting their children’s emotional and mental well-being during the challenging transition back to the classroom and throughout the school year! Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Week of Wellness for Parents/Caregivers and their Children

An activity guide for parents and caregivers to incorporate daily wellness activities at home to enhance the emotional well-being of their children. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

For Child Welfare Youth, Families and Staff

Behavior Is Communication: A Resource for Child Welfare Support Staff

We created this resource guide to better connect you with the young people you work with. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Building Peer Relationships for Youth and Young Adults in the Child Welfare System

We created this guide to help anyone navigating trauma feel less alone. Here’s how you can safely begin to seek community. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

The Child Welfare System: A Guide to Trauma for Caregivers

We created this resource as a guide to help you reflect, re-establish and rebuild healing relationships with your child experiencing trauma as part of their experience in foster care. Download Resource Download Resource in Spanish

Statistics and Research

2020 Mental Health by the Number

A one-pager with data on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth and young adult. Download Resource

New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic

CDC’s first nationally representative survey of high school students during the pandemic can inform effective programs. View Resource

Poll of Teen Mental Health from Teens Themselves (2022)

A poll conducted by Ipsos on behalf of NAMI finds that most teens are comfortable talking about mental health, but often don’t start the conversation. They also want schools to play a big role in their mental health, and they trust the information they get there, but feel like schools are not doing enough. Download Resource

Poll of Parents Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic (2021)

A poll conducted by Ipsos on behalf of NAMI finds that an overwhelming number of parents support mental health education in schools and “mental health days” for their children. Download Resource

Treatment For Suicidal Ideation, Self-Harm, And Suicide Attempts Among Youth

A guide that provides interventions to treat for suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide attempts among youth. It provides research on implementation and examples of the ways that these recommendations can be implemented. View Resource

Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data Summary and Trends Report 2009-2019

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2009–2019 provides the most recent surveillance data on health behaviors and experiences among high school students in the US related to four priority areas associated with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including HIV, and unintended teen pregnancy: sexual behavior, high-risk substance use, experiencing violence, and mental health and suicide. View Resource

Blogs and Videos

College Mental Health Blogs

Teen Mental Health Blogs

#Notalone Conversation: Heading Back to School

Sherman Gillums joins Ananya Venkatachalam (student), Shobhana Radhakrishnan (mom), and Jamie Meisinger (teacher) to discuss heading back to school after a year of at-home learning. This conversation opens the dialogue to realize the mental health challenges and opportunities for students, teachers and parents. Watch Video

What is PTSD?

Learn what PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder) is, its causes, symptoms and treatment options. Watch Video

Know the warning signs of mental illness

Learn more about common mental health conditions

NAMI HelpLine is available M-F, 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. ET. Call 800-950-6264 , text “helpline” to 62640 , or chat online. In a crisis, call or text 988 (24/7).

Tips for Presenting to Young Audiences

It was my first year in business and I was 20-minutes into delivering a one-hour presentation skills seminar when it was becoming painfully clear that I was losing my audience fast. With this particular group, the early warning signs were all there…

It started with some subtle multi-tasking activity followed by a pronounced loss of eye contact by a few individuals at first and then half the group. If you’ve ever had that experience you know that you only have a couple of options at that point. You can try to pump up the energy level and occasionally re-energize an audience; but, let’s face it, the odds are pretty slim. Or you can always start summarizing, cut your loses and go for a well-scripted close. At least there’s some hope that your audience will, at a minimum, hear a few crisp closing points and an interesting story to tie it all together. On that particular day, I didn’t have a chance to do either. The bell rang at precisely 11:22 and Cheryl Bailey’s PowerPoint class darted for the door and I was left standing there (unplugging my projector and laptop) wondering what the heck just happened. It was my first time presenting to a group of kids and since then I’ve had to revise my technique considerably for this unique audience.

Lest you think these opportunities are pretty rare, you’d be surprised. Recently a client of mine was asked to be a keynote speaker for an audience of 300 high-achiever type high school kids. He had a track history of turning around troubled companies and had spent the last three years creating a nationally recognized direct marketing powerhouse from a once struggling east coast printing company. As we scripted his one-hour address, we came across the writings of Dr. Kenneth McFarland, an International Speaker’s Hall of Fame Award recipient and a strong advocate for the importance of sharing our very best thoughts with the youth of America. R.S Warn captured some of them in a paper called, ‘When Asked to Speak’. If you ever think you may be speaking to a group of kids (or perhaps are just wondering how to get through to your own), you will find these insights helpful as you attempt to communicate with today’s toughest audience.

Have the Right Frame of Mind

Speakers should approach a young audience with one very important understanding – young people are genuine. Young audiences openly express feelings where adults often pretend. When young people don’t like what’s being said, they will never act like they do. They are not naturally rude: they just refuse to pretend. This instant and honest feedback is a sterling quality in young audiences, a quality that some speakers avoid like the plague.

Ignore Their Masks

Shallowness, insincerity and callousness are masks young people wear, but rarely indicate who they really are. Our youth will appear untouched on the surface while deeply stirred by stories with human and emotional elements. They will also rally around basic ideals faster than the average adult audience. They do want to build a better world and are grateful for any relevant insights you may provide.

Make It Come Alive

A common error made by business speakers is the attempt to breathe life into a dead script (theirs or someone else’s). Unless your heartfelt feelings are involved, it is impossible to bring life to the words of another. Young people are not concerned with factual details of a letter-perfect manuscript, what they need to know is that the person standing before them is real. Hiding behind a script is a very fast way to lose them. The more of yourself you weave into the fabric of your speech the more “alive” it will become for them. When looking for ways to drive home a point, look for what you thought, what you found, what you felt, what you did and how you now feel. Inexperienced speakers, breaking every known rule of speech, have touched young people deeply by speaking from their heart.

Know You’re On Stage

This audience is sizing you up from the moment you arrive. When required to sit on stage or at a head table, know that everything you do either “adds to” or “detracts from” the value of the program. Pay full attention to the other speakers on the program as well. When this is not done, it tends to discredit the value of what’s being said. Kids can spot disrespect quickly and it will only impact their perception of you.

The True Power is in Simplicity

True power from the platform lies in using simple language to express meaningful ideas. Words are mental brush strokes we use to paint pictures in the minds of others. Uncommon and difficult words tend to leave people, especially youth, confused and insulted. A speaker overly impressed with a large vocabulary and insistent on demonstrating six syllable words is not a speaker at all, only a person who fills a room with confusing noise. (Noise that young people will always add to in very short order.)

Audience Participation

Audience participation helps hold the attention of young people. The younger the audience, the more important this device becomes. It can be as simple as a show of hands and as involved as your time, talent and ability contributed before and after the event. A participation device needs to tie directly with a major point in your message, however. Where this is not done, your audience becomes sidetracked. When asking group questions from youth, you can expect questions that adults would never ask. (How much do you make? How many hours do you work? Have you ever fired anyone?) Whatever the question, they must be handled as an important question and treated with respect.

Never Talk Down

They may lack wisdom that comes with maturity, but the average high school audience of today is better informed than they’ve ever been before. Young people watch the evening news and are often more in tune with worldwide problems than some adults. Any speaker who stands before them with an attitude of being all wise will lose this audience in the first 60-seconds. Our young people encounter so much condescending speech in their daily lives that they naturally assume any adult who steps before them will deliver the same. You need to break that perception quickly.

Never Attempt to Be One of Them

The only way you can become like a child again is to become senile and these young people know it. When you earn their respect, they will accept you as an adult, but they will never accept you as one of them. Any attempt to be one of them, just one of the gang, will backfire in your face. Everything you do, your dress, actions and words should aim to project an image of an adult, the type of adult they may want to become.

I’ve only hit the highlights from Dr.McFarland’s insights and I’ve thrown in a few of my own. From these pearls of wisdom, one thing is clear, the need to be genuine is never as important as it is with youthful audiences. What kids are looking for is often very different than what we may think. As the father of some great kids, I found some basic wisdom here as well. We rarely understand at the time how our words impact young hearts and minds. And as indifferent as they may seem at times, they desperately want to find adults in their lives who they can look up to and model.

Young people may be one of today’s toughest audiences, but there will never be any more important.

Written by Jim Endicott

Recommended Pages

Hi, I’m from Singapore and I frequently give talks on estate planning. Just last week, my audience was a group of financial advisers mostly in their mid to late 20s. As a 60-year old seasoned presenter, I appeared at the talk without preparing how to I should be presenting to a young audience. I went through my usual “humorous” examples that I’ve used on a mature audience, used technical terms that could have been avoided and tried to sound more animated than usual. Well as you can imagine, half of them started yawning and playing with their cell phones after 10 minutes. I wish I had come across your excellent article before! Thank you for a very welcome wake up call!

- All Templates

- Persuasive Speech Topics

- Informative

- Architecture

- Celebration

- Educational

- Engineering

- Food and Drink

- Subtle Waves Template

- Business world map

- Filmstrip with Countdown

- Blue Bubbles

- Corporate 2

- Vector flowers template

- Editable PowerPoint newspapers

- Hands Template

- Red blood cells slide

- Circles Template on white

- Maps of America

- Light Streaks Business Template

- Zen stones template

- Heartbeat Template

- Web icons template

VentureLab Blog » Entrepreneurship Education Articles

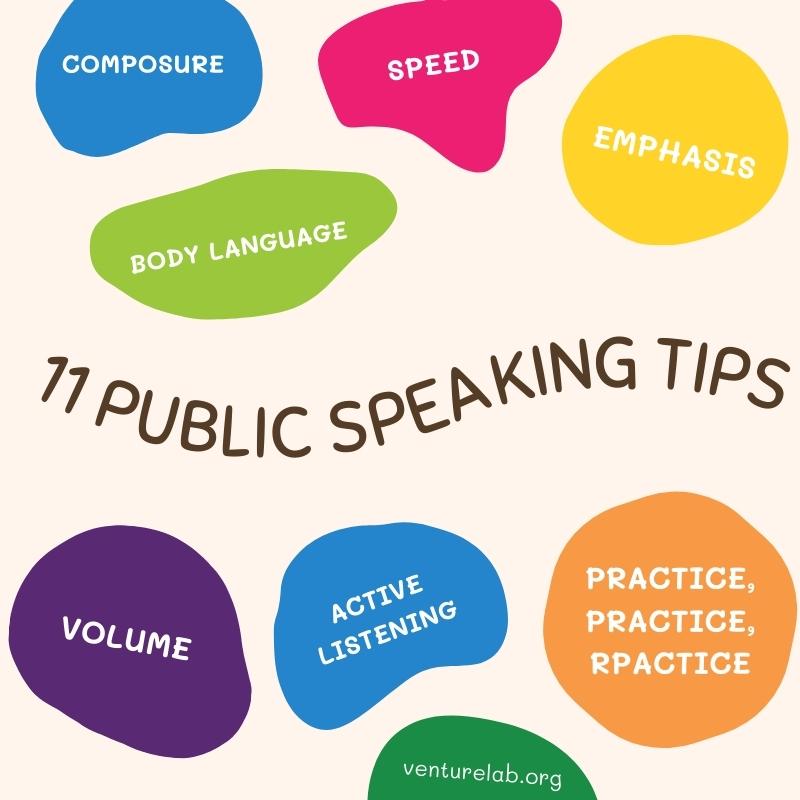

11 Public Speaking Tips for Youth (and Adults!)

- December 6, 2021

Public speaking is an essential skill for entrepreneurship and beyond, but for many, it’s a source of anxiety. However, with consistent practice and applying specific techniques, anyone can become more confident sharing their ideas with any audience!

We’ve compiled a list of public speaking tips that can help both youth and adults become more confident, persuasive speakers.

Public Speaking Tip 1: Composure

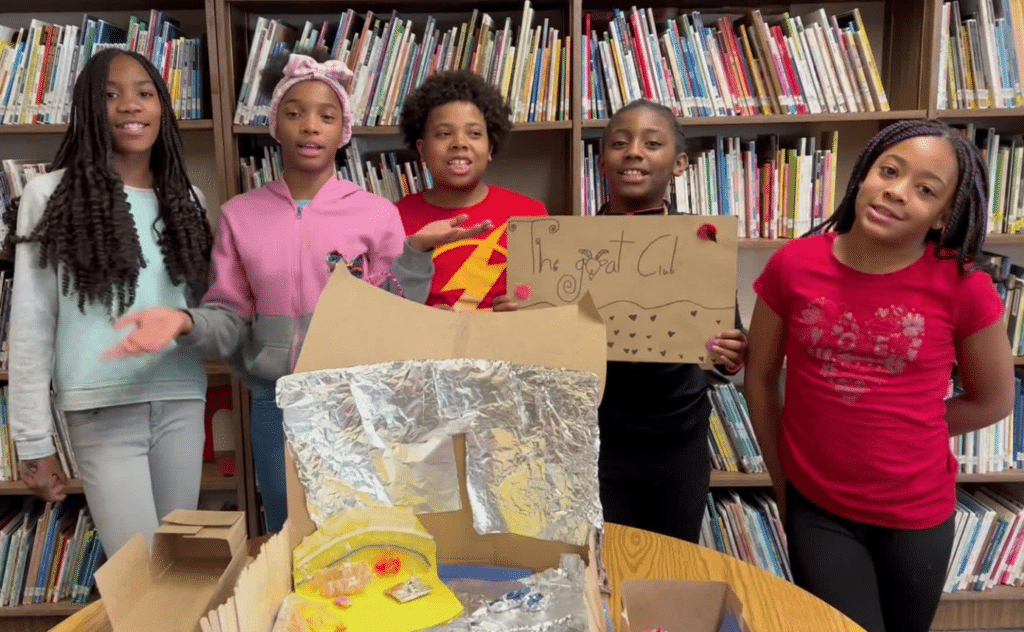

Even professional public speakers get nervous! It’s normal to be anxious or worried and have lots of adrenaline flowing. Take two deep breaths. Practice what you’ll say in your head and go for it! Watch Sage master his composure (and remember to stop and breathe at 30 seconds) to deliver a wonderful pitch:

Public Speaking Tip 2: Body Language

Body language can make a big difference in how your message is perceived. Sit/stand up straight. Use your hands as you talk (but not too much) and avoid crossing your arms. Maintain eye contact with your audience to establish connection, trust, and show confidence .

Public Speaking Tip 3: Speed

Pay attention to how quickly or slowly you are speaking. Effective speakers talk at a pace that makes it easy for the audience to understand what they’re saying. Consider recording yourself and listening back to your speech; you may be surprised by how fast you talk!

Effective speakers talk at a pace that makes it easy for the audience to understand. As you practice, try recording yourself and listening back to your speech; you may be surprised by how fast you talk! Tweet this

Public Speaking Tip 4: Volume

Pay attention to how loud or soft you are speaking. Effective speakers talk at a volume that makes it easy for the audience to hear what they’re saying but avoid shouting. It’s okay to vary your volume , too. (See Tip 5!)

Public Speaking Tip 5: Emphasis

Pay attention to what words you are emphasizing when you speak. Effective speakers draw attention to important words and phrases, which makes your speech more interesting and compelling! Be sure to slow down and emphasize your business name.

Public Speaking Tip 6: Pausing

Pay attention to when you are taking a break to pause. Effective speakers take time to collect their thoughts and leave room for moments of quiet. It’s always okay to stop and take a breath as you need it, too.

Effective speakers take time to collect their thoughts and leave room for moments of quiet. It's always okay to stop and take a breath as you need it, too. Tweet this

Public Speaking Tip 7: Active Listening

Effective speakers are also active listeners! Face the speaker and make eye contact, nod, and smile when appropriate to acknowledge what is being said. Resist the urge to interrupt!

Public Speaking Tip 8: Practice, Practice, Practice!

The best way to get used to implementing all of the public speaking tips above? Practice! This doesn’t have to be formal. Record yourself practicing on your phone or laptop, then watch it back and consider how you’ve applied the tips. Practice in front of family, friends, or the mirror! The more you practice, the easier public speaking becomes.

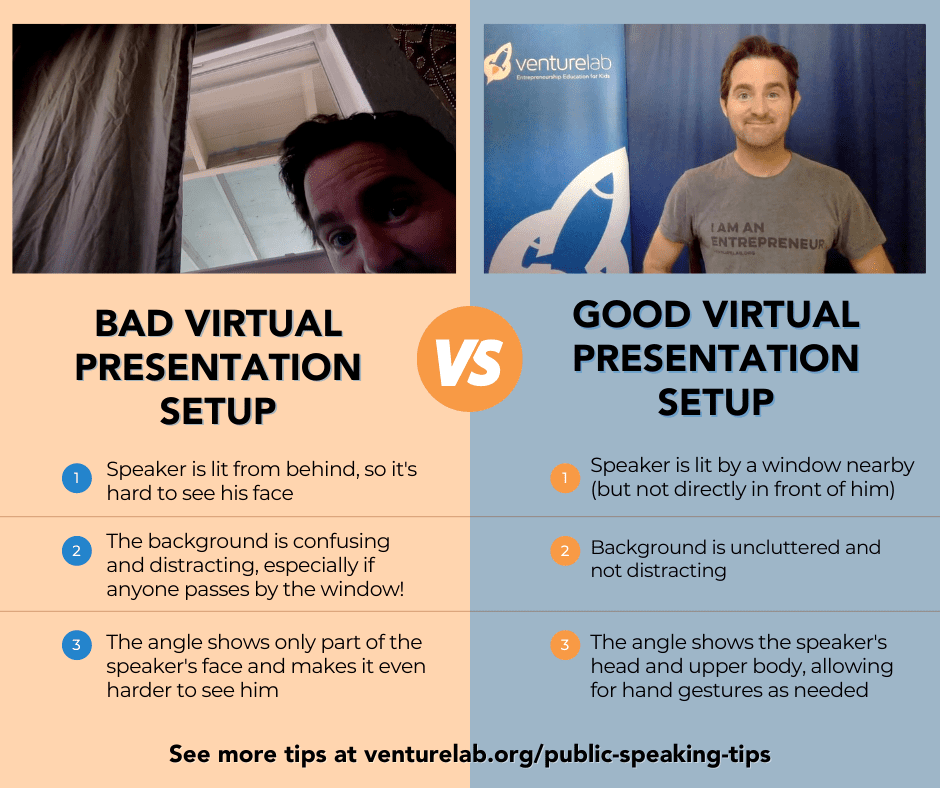

Public Speaking Tips for Virtual Presentations

Virtual Public Speaking Tip 1: Background

Pay attention to what is going on in your background. Effective speakers create a background setting that isn’t distracting . Even a plain wall can work as a perfect setting for viewers to focus on you and not your background!

Virtual Public Speaking Tip 2: Lighting

Poor lighting can make it hard for others to work on your message! Position yourself near a window or other light source so that your face is clearly lit. Avoid sitting with your back to a window, which can cause your image to become too dark to see. Test your lighting ahead of virtual presentations so you’re ready when it’s time!

See an example of a fantastic pitch with great lighting (and camera positioning):

Virtual Public Speaking Tip 3: Camera Positioning

Pay attention to what parts of you appear on screen. Make sure your entire face can be seen. (If you can, include your shoulders, too!) Elevate your device so the camera is eye level. Putting your laptop on top of a few books can do the trick.

Help your youth practice public speaking!

Looking for more youth entrepreneurship.

Sign up for our monthly resource email to receive activities, tips, and more right to your inbox. It’s easy and free!

Related blogs:

Printable Entrepreneurial Mindset Cards

3 Reasons to Bring Entrepreneurship to Summer Learning

VentureLab’s May 2023 Youth Pitch Event Recap and Replay

Three strategies to make your classroom entrepreneurial AND run smoothly

STARBASE Robins Summer Camps brings STEM and entrepreneurship to life for Georgia youth

The Impact of Youth Entrepreneurship Education in Houston with VentureLab and BakerRipley

Recent posts, ready, set, startup was a success, how to plan youth entrepreneurship events for success, venturelab celebrates national mentorship month with a spotlight on spark 2023 graduates, related posts.

We're on a mission to create the next generation of diverse innovators and changemakers by making entrepreneurship education accessible to ALL youth.

Get involved.

© COPYRIGHT 2024 VENTURELAB, A 501 (C)(3) NON-PROFIT | Website developed by iNNOV8 Place | Powered by Electric Oak | Privacy Policy | License Agreement

Pin It on Pinterest

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Committee on Improving the Health, Safety, and Well-Being of Young Adults; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council; Bonnie RJ, Stroud C, Breiner H, editors. Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 Jan 27.

Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

2 Young Adults in the 21st Century

This chapter provides a foundation for the remainder of the report. It summarizes current knowledge regarding young adulthood as a critical developmental period in the life course; highlights historical patterns and recent trends in the social and economic transitions of young adults in the United States; reviews data on the health status of the current cohort of young adults; briefly summarizes the literature on diversity and the effects of bias and discrimination on young adults' health and well-being; presents the committee's key findings and their implications; and enunciates several key principles to guide future action in assembling data, designing research, and formulating programs and policies pertaining to the health, safety, and well-being of young adults. Many of the topics summarized in this chapter are discussed in greater depth in subsequent chapters.

- BASIC PATTERNS OF DEVELOPMENT

Biologically and psychologically, young adulthood is fundamentally a period of maturation and change, although the degree of change may seem less striking than the changes that occurred during childhood and adolescence. As just one example, the physical changes of the transition from childhood into adolescence are transformative, with bodies growing in dramatic bursts and taking on secondary sex characteristics as puberty unfolds. As young people move from adolescence into adulthood, physical changes continue to occur, but they are more gradual. Individuals begin the steady weight gain that will characterize adulthood, but these changes are not as discontinuous as they are at the beginning of adolescence ( Cole, 2003 ; Zagorsky and Smith, 2011 ).

In some ways, the tendency for the developmental change that happens during young adulthood to be gradual instead of dramatic may have led to the devaluation of young adulthood as a critical developmental period, but that developmental change should be not be underestimated. It is integral to transforming children and adolescents into adults. The psychological and brain development that occurs during young adulthood illustrates this point.

Psychological Development

Over the past two decades, research has elucidated some of the key features of adolescent development that have made this period of the life course unique and worthy of attention. These insights, in turn, have helped shape policy in major ways. These adolescent processes, and the increasing scientific and public attention they have received, provide a reference point for understanding the developmental importance of young adulthood.

In general, adolescence is a complex period characterized by substantial cognitive and emotional changes grounded in the unfolding development of the brain, as well as behavioral changes associated with basic psychosocial developmental tasks. In particular, adolescents are faced with the task of individuating from their parents while maintaining family connectedness to facilitate the development of the identities they will take into adulthood. At the same time, the overactive motivational/emotional system of their brain can contribute to suboptimal decision making ( Crosnoe and Johnson, 2011 ). As a result, many adolescents tend to be strongly oriented toward and sensitive to peers, responsive to their immediate environments, limited in self-control, and disinclined to focus on long-term consequences, all of which lead to compromised decision-making skills in emotionally charged situations ( Galván et al., 2006 ; Steinberg et al., 2008 ). This combination of characteristics is implicated in the heightened rates of risky behaviors and accidental death among adolescents (and young adults) relative to childhood and later stages of life, and awareness of these issues has reshaped policy responses to adolescent behavior in general and crime in particular (as described in the National Research Council [2013] report on juvenile justice).

Clearly, much social, emotional, and cognitive maturation needs to occur before adolescents are capable of taking on adult responsibilities and their many behavioral risks decline to adult-like levels. The ongoing development that occurs during young adulthood is what marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Again, this development is not necessarily discontinuous (such as the notable surge in risk taking that occurs during the transition from childhood into adolescence), but instead, it takes a more gradual and linear form, less obvious perhaps but no less important. Although findings from studies that directly compare adolescents and young adults on various cognitive tests and decision-making tasks are by no means uniform, the available research documents the slow and steady progress in self-regulation and related psychological capacities that takes place as adolescents transition into their 20s (see Cauffman et al., 2010 ). Compared with adolescents, young adults

- take longer to consider difficult problems before deciding on a course of action,

- are less influenced by the lure of rewards associated with behavior,

- are more sensitive to the potential costs associated with behavior, and

- have better developed impulse control.

In other words, the differences between adolescents and adults are stark, and the years between 18 and 26 are when young people develop psychologically in ways that bridge these differences. This development reflects many things, including the opportunities young people have to take on new roles and responsibilities and changes in their social contexts. It also reflects the similar gradual development of their brains.

Brain Development

The process of structural and functional maturation of the brain through adolescence to adulthood has garnered a great deal of attention, as neurobiological processes are believed to stabilize before declining with age. Maturation is of particular interest given the role of plasticity in affording opportunities for specialization, but also posing risks for abnormal development. Developmental neuroscientists, however, have traditionally assumed that adulthood is reached by age 18—hence the predominance of neurodevelopmental studies that compare children (under age 12) and adolescents (approximately 12-17) with adults (18-21 or extending and averaging through the mid-20s to the 30s). This approach has revealed many immaturities during the adolescent period, but much less is known about young adulthood. Discussions recently have emerged of the possibility of a prolonged brain maturational trajectory through young adulthood, as described below. Although the most significant qualitative changes in brain maturation have been found to occur from childhood to adolescence, emerging evidence does suggest that specialization of brain processes continues into the 30s, supporting both cognitive and motivational systems.

The primary mechanisms underlying brain maturation through adolescence into adulthood are synaptic pruning, myelination, and neurochemical changes. Synaptic pruning refers to the programmed elimination of synaptic connections between neurons believed to support specialization of brain processes based on experience. After a proliferation of synaptic connections through childhood, when the gray matter thickens, a decline in synaptic connections occurs through adolescence ( Petanjek et al., 2011 ) and is believed to contribute to the thinning of gray matter that proceeds through adolescence ( Gogtay et al., 2004 ). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, which provide in vivo measurements of gray matter thickness, have focused predominantly on immaturities during adolescence and have considered adulthood to be established by the early 20s ( Gogtay et al., 2004 ). MRI studies that sample a wider age range, however, indicate a prolonged period of gray matter thinning of prefrontal cortex that persists through the third decade of life ( Sowell et al., 2003 ; see also Figure 2-1 ). Similar maturational trajectories have been observed in human postmortem studies that indicate a continued decrease in synaptic connections in the prefrontal cortex into the 30s ( Petanjek et al., 2011 ). The prefrontal cortex is the region that supports abstract reasoning and planning. Through its extensive connectivity throughout the brain, it also supports executive function, providing control and modulation of behavior ( Fuster, 2008 ). It plays a major role in decision making, and its maturation is believed to support cognitive development ( Fuster, 2002 ; Luna, 2009 ).

Continued maturation of prefrontal cortex through young adulthood evidenced from (A) in vivo MRI results showing thinning of cortical gray matter in prefrontal cortex and (B) postmortem evidence showing continued loss of synapses in prefrontal cortex (more...)

Notably, despite continued specialization in the prefrontal cortex through the 20s, its engagement during executive tasks can appear adult-like as early as adolescence. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies of executive control through adolescence report both greater and lesser engagement of lateral prefrontal regions known to play a primary role in executive function ( Luna et al., 2010 ). A recent longitudinal study was able to characterize developmental changes in core cognitive components of the ability to suppress impulsive responses by measuring the ability to stop a reflexive eye movement ( Ordaz et al., 2013 ). Results suggest a decrease in prefrontal engagement through childhood stabilizing by adolescence. However, recruitment of the anterior cingulate cortex, a medial prefrontal region that is distinct from other prefrontal regions in supporting performance monitoring and error processing, increases during executive function processing through adolescence and young adulthood ( Ordaz et al., 2013 ). These results suggest that processes distinct from prefrontal executive function that support monitoring behavior underlie cognitive development and continue to mature through young adulthood. The implication is that by young adulthood, prefrontal executive processes are at adult levels, but processes involved in monitoring behavior are still improving, which may affect decision making.

In addition to the maturation of prefrontal systems that support executive function, motivational and emotional brain systems in limbic areas show a protracted development through adolescence and young adulthood. The striatum is a limbic region rich in dopaminergic innervation. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that supports motivation and reward processing ( Cools, 2008 ). Through its connectivity with prefrontal systems, it provides motivational modulation of behavior. MRI studies indicate that the striatum peaks in gray matter growth at an even later time than cortical regions through adolescence ( Raznahan et al., 2014 ; Sowell et al., 1999 ; Wierenga et al., 2014 ). In addition, animal studies suggest a peak in the availability of dopamine, believed to play a role in increased sensation seeking beginning in adolescence ( Padmanabhan and Luna, 2013 ; Spear, 2000 ; Wahlstrom et al., 2010 ). fMRI studies typically show a peak of increased recruitment of the striatum during monetary reward tasks in adolescence that decreases through young adulthood ( Galván et al., 2006 ; Geier et al., 2010 ; van Leijenhorst et al., 2010 ). In particular, the presence of peers has significant salience in adolescence, engaging the reward circuitry to affect decision making ( Chein et al., 2011 ). The trajectory of changes in reward processing through young adulthood, however, has not been directly investigated and in fact some studies have used young adults to represent all adults ( van Leijenhorst et al., 2010 ). It is possible that developmental declines in striatal activity in response to rewards may be lower in young adulthood than in adolescence but still be greater than in later adulthood. Similarly, the amygdala, which supports emotional processing, has a peak in gray matter growth in the teen years, with a subsequent decrease in volume ( Greimel et al., 2013 ; Scherf et al., 2013 ). The amygdala shows greater functional reactivity to emotional stimuli in adolescence ( Blakemore, 2008 ; Hare et al., 2008 ), which may persist through young adulthood. Animal studies indicate that white matter fibers between the amygdala and cortex continue to increase into young adulthood ( Cunningham et al., 2002 ). Despite this increase in structural connectivity, however, human neuroimaging indicates decreased functional connectivity into young adulthood, suggesting developmental increases in regulatory development with regard to the effects of emotion processing on behavior ( Gee et al., 2013 ).

In parallel with decreases in gray matter in prefrontal and striatal regions are increases in white matter brain connectivity, which supports the ability for prefrontal executive systems to modulate reward and emotional processing. Postmortem studies indicate continued myelination—insulating of white matter connections—through adolescence and adulthood throughout cortical regions, including prefrontal systems ( Lebel et al., 2008 ). Diffusion tensor imaging, which measures the integrity of white matter connections in vivo, indicates a hierarchical maturation of white matter, with tracts connecting cortical and limbic regions showing protracted development through adulthood ( Lebel et al., 2008 ; Simmonds et al., 2013 ). During childhood to adolescence, a peak in white matter growth occurs throughout the brain, with continued growth of tracts as they reach cortical and limbic gray matter in young adulthood ( Simmonds et al., 2013 ). Last to mature are the cingulum and uncinate fasciculus, which provide connectivity between cortical and limbic regions. The cingulum integrates dorsal frontal cognitive (e.g., anterior cingulate supporting performance monitoring) and limbic regions supporting emotion processing that continue to mature through the early 20s ( Simmonds et al., 2013 ). The uncinate fasciculus, which integrates ventral frontal cortical (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex supporting motivation), amygdala (supporting emotion), hippocampus (supporting memory), and temporal cortical regions that form a circuit underlying socioemotional processing, continues to mature through the 20s ( Simmonds et al., 2013 ). During young adulthood, therefore, connectivity that supports socioemotional processing is still immature but developing compared with later adulthood.

Within these maturation processes are unique gender differences that emerge in adolescence, are believed to be associated with earlier puberty in girls than in boys, and continue to dissociate through adulthood ( Dorn et al., 2006 ; Ordaz and Luna, 2012 ). Young men have larger total brain volume, females show earlier cortical thinning and maturation of white matter integrity ( Lenroot et al., 2007 ; Simmonds et al., 2013 ), and males show greater change in limbic regions ( Giedd et al., 1997 ; Raznahan et al., 2014 ). These differences are believed to underlie gender differences in the emergence of different psychopathologies, including female predominance of depression and male predominance of antisocial personality disorders.

Taken together, the evidence demonstrates continuing maturation of limbic systems supporting motivation and reward processing and prefrontal executive systems. It has been proposed that the relative balance of maturation of motivational systems and prefrontal executive processing underlies the adolescent sensation seeking already discussed ( Ernst et al., 2006 ; Smith et al., 2013 ; Somerville and Casey, 2010 ). In young adulthood, this imbalance diminishes but is still present. Brain systems supporting motivational and socioemotional processing are still maturing in young adulthood, influencing a more developed prefrontal executive system capable of more sophisticated and effective planning and resulting in unique influences on decision making, such as adaptive choices or risk-taking behavior. Overactive motivational systems may drive adult-like access to cognitive systems, resulting in planned responses that are driven by short-term rewards. Indeed, greater sensation seeking often persists into the mid-20s. This profile of decision making may also affect the attention given to choices regarding health, profession, and relationships, which are addressed in this and later chapters.

The Developmental Bottom Line

Overall, critical developmental processes clearly occur during young adulthood. Initial findings suggest that mature aspects of executive functioning are paired with continuing increased motivational/emotional influences affecting decision making. Still, more work is needed to fully understand young adulthood as a biologically and psychologically distinct and critical period of development and to relate these neurological changes to behavioral and social changes that typically occur during this period. Although these processes of maturation may sometimes appear as limitations on optimal decision making in young adulthood, the enhanced motivational processing that also occurs during this period plays an important adaptive role in supporting optimal learning and the ability and impetus to explore the environment and novel experiences.

- HISTORICAL PATTERNS OF SOCIAL ROLES AND ACTIVITIES

The important psychological development experienced by young adults has not changed dramatically across generations, but their social functioning has ( Steinberg, 2013 ). Social and behavioral scientists frequently discuss such social functioning in terms of five major role transitions of young adulthood—leaving home, completing school, entering the workforce, forming a romantic partnership, and transitioning into or moving toward parenthood ( Schulenberg and Schoon, 2012 ; Shanahan, 2000 ). The focus on these social roles as the benchmark against which young adults from diverse segments of the population are compared can be critiqued as classist, ethnocentric, and heteronormative. These critiques certainly need to be acknowledged, but these role transitions do provide a useful structure for organizing the present discussion of young adulthood in the United States, especially if the significant diversity in these transitions among U.S. youth—both historically and in the contemporary era—is highlighted.

Two basic concepts—the timing and the sequencing of role acquisition—capture how the transition to these adult roles is taking more time and becoming more unpredictable ( Settersten and Ray, 2010 ).

First, the timing of role acquisition in young adulthood is changing. In the long view, today's U.S. young adults are taking less time to undergo these role transitions relative to young adults in the distant past. Relative to more recent cohorts, however, they are taking more time. The timing of role acquisition is affected by, among other things, economic development and state investments that impose various signifiers of life transitions, such as legal rules on when youth are granted various privileges and allowed to enter certain statuses or, alternatively, when they age out of services or other protections ( Modell et al., 1976 ; Shanahan, 2000 ).

Second, the sequencing of role acquisition (i.e., the order in which various roles are assumed) also is changing. Configurations of young adult statuses may change across cohorts. Recently, more diverse combinations of statuses have led to a “disordering” of the transition into adulthood, a term that seems pejorative but is not bad or good per se. The sequence of the roles assumed in the transition to adulthood increasingly is shaped by individual choices and actions rather than social structures. As discussed below, for example, young people partner and parent in different sequences because they have the freedom to do so now that the social stigma of nonmarital childbearing has diminished, and because economic or policy factors make various sequences more appealing and feasible than they used to be ( Fussell and Furstenberg, 2005 ; Lichter et al., 2002 ; Rindfuss et al., 1987 ).

Family Roles

For many young adults, a major event is leaving the parental home to reside independently or with others of the same age. In some ways, leaving home is a rite of passage, which is why one main topic of interest concerning modern young adults in general and young adults during the Great Recession in particular is “boomerang” children—young adults who leave home to live independently but come back to reside with their parents ( Stone et al., 2013 ). In truth, young adults living with their parents 1 in moderate to large numbers is not a new phenomenon in the United States or in other industrialized societies, and doing so is not inherently problematic or beneficial. In the United States, 32 percent of young adults aged 18-31 lived at home with their parent(s) in 1968, in 1981 31 percent did, and in 2012 36 percent did ( Fry, 2013 ). How people assess young adults living with their parents instead of with peers or alone often reflects how they perceive (or misperceive) the past, including their own personal histories ( Settersten and Ray, 2010 ; Stone et al., 2013 ).

Beyond leaving the parental home, many other noteworthy family events occur in the lives of today's young adults. In assessing the historical relevance of these contemporary patterns, one must keep in mind the importance of the comparison point. As with leaving home, contemporary young adult behaviors and statuses often seem so striking because they are viewed in the context of the post–World War II era, especially the 1950s. This era, however, was something of a historical outlier. What is going on today with young adults—especially in relation to family roles and responsibilities—appears to be less divergent, although still divergent, when compared against the full scope of the 20th century ( Coontz, 2000 ).

Partnership and parenting are the core of family formation in the United States (see Chapter 3 ). How partnership is defined and how it connects to parenting have both evolved considerably in recent decades. Traditionally, partnership was defined in formal (i.e., legal) terms as marriage, especially among the white middle class. Today, partnership in young adulthood is most often viewed as a sequence from cohabitation—living with a romantic partner—to marriage (a transition from an informal to a formal partnership widely recognized by laws) or just as cohabitation itself. While most young Americans see cohabitation as a precursor to marriage, this has not always been the case. Many immigrant families from Latin America, for example, have a long tradition of cohabitation as a form of marriage, but the practice of cohabitation as a step toward marriage is new for most groups ( Cherlin, 2009 ).

Figure 2-2 shows the percentages of young adults having engaged in at least one of three family formation behaviors—cohabitation, marriage, and parenting—by age 25 by gender, race/ethnicity, and level of education (high school or college graduate). In total, just under two-thirds of young adults have made at least one of these three family role transitions by age 25 ( Payne, 2011 ). This proportion, however, fluctuates across the population. A larger proportion of women than men have made at least one of these role transitions (69 percent versus 53 percent), and family formation is less common among young adults who are white (59 percent) than among those who are not (66 percent for African Americans and 64 percent for Latino/as). There is also an educational gradient to family formation in young adulthood, with family role transitions becoming less common as educational attainment rises. Indeed, college graduates are the only segment of the population in which less than a majority of young adults have made at least one of the three family role transitions. Of these three transitions, the most common is cohabitation (47 percent), followed by becoming a parent (34 percent) and marrying (27 percent) ( Payne, 2011 ).

Percentage of young adults in the United States with at least one family formation behavior by age 25. NOTE: The dotted line represents the overall sample average (61 percent). SOURCE: National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997 (see Payne, 2011).

One important caveat to keep in mind when considering these family formation patterns is that historically, tracking the family formation behaviors of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people has been exceedingly difficult. Because sexual relations between people of the same gender were outlawed in many states until recently, identifying the LGBT population was a challenge. Only within the past decade have same-sex couples been legally allowed to marry, and they may do so even now only within a minority of states (although the number is growing quickly). Thus, many LGBT young adults would have been classified as cohabiting in the past simply because they were legally barred from marrying. Moreover, innovations in reproduction technology and changes in adoption laws (domestically and internationally) have enabled these young adults to become parents without having to engage in an opposite-sex partnership before entering a same-sex partnership—long the most common path to parenthood for gays and lesbians. In states where same-sex marriage is legally recognized, same-sex parents are demonstrating patterns of union formation (and dissolution) similar to those of opposite-sex parents ( Hunter, 2012 ; Parke, 2013 ; Seltzer, 2000 ).

In terms of timing, family formation is clearly showing signs of becoming a longer-term process. In short, young adults are taking more years to partner and become parents than they did in the past, especially compared with the last half of the 20th century. Today, the median age at first marriage—the age by which half of the population has married—is just under 27 for women, a nearly 5-year increase over the past 30 years and extending beyond the 18-26 age range used to define young adulthood in this report ( Arroyo et al., 2013 ). A similar trend has occurred among men, although their median age at marriage has consistently been a year or so higher than that of women. This trend often is discussed in terms of “delay,” but it is better thought of as part of the prolonged family formation process overall. As Americans live longer, they take more time to reach life-course milestones such as marriage. The transition to parenthood also tends to occur later in the life course, although the increase in median age at first birth over the last three decades has been less pronounced than the increase in median age at first marriage—about 3 years rather than 6 and just within our focal 18-26 age range ( Arroyo et al., 2013 ).

These differences in the magnitude of the age increase in major family role transitions also speak to sequencing, or the growing tendency for transitions to cluster in heterogeneous ways. For most of American history (especially among the white middle class), marriage preceded parenthood. Yet the lesser increase in age at first birth compared with age at first marriage resulted in the two trends eventually converging (in 1991, to be precise). Since that point, median age at first marriage has been older than median age at first birth ( Arroyo et al., 2013 ). The sequence (or order) of these transitions has become less predictable.

Breaking down partnerships into cohabitation and marriage when discussing major family role transitions of young adulthood also reveals evidence of changing sequencing. In line with the increasing prevalence of cohabitation in the population at large, the proportion of young adults who have cohabited by the age of 25 (47 percent) is higher than the proportion of young adults who have married (27 percent) ( Payne, 2011 ). Three-fifths of all young adults who are married cohabited first, lending credence to the idea that cohabitation is now the modal pathway to marriage. Furthermore, one-third of young adults with children became parents before marrying or cohabiting. Just as with overall family formation patterns, these specific family patterns differ by gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. For example, marriage without cohabitation is more common among whites and college graduates, but becoming a parent without partnering is far less common in these same two groups ( Payne, 2011 ).

Overall, young adults (including LGBT young adults) in the United States are taking more time before entering into family roles that have long defined adulthood compared with their parents and grandparents, and they are sequencing these roles in multiple ways. This is particularly true for youth from white middle-class backgrounds.

Socioeconomic Roles

The transition from student to worker is a defining feature of young adulthood, given that Americans widely view financial independence from parents as a marker of becoming an adult. Yet young people are taking longer to become financially independent, and their school-work pathways are becoming more complex ( Settersten and Ray, 2010 ). As with family formation, changes have been occurring in the timing and sequencing of the socioeconomic aspects of young adult role transitions. Chapter 4 gives a detailed accounting of how young people are faring in the educational system and in the labor market, but we highlight a few patterns in school-to-work transitions here in the context of the overall importance of studying young adults today.

Beginning with education, more young adults than in the past have been entering higher education in recent decades, but they are participating in higher education in many different ways and following diverse pathways ( Fischer and Hout, 2006 ; Goldin and Katz, 2008 ; Patrick et al., 2013 ). According to data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, in the United States, 59 percent of young adults have enrolled in some form of higher education by the time they reach age 25 ( Payne, 2012 ). The overwhelming majority enrolled right after leaving high school, around age 18. Of those who enrolled, 33 percent enrolled in 2-year colleges and 44 percent in 4-year colleges and universities, with the remainder enrolling in both ( Payne, 2012 ).

Of course, enrollment is not the same as graduation. The reality is that many young adults who enroll in higher education fail to earn a degree, at least while they are still young adults. Indeed, rates of completion of higher education in the United States have declined even as rates of enrollment have increased ( Bailey and Dynarski, 2011 ; Bound et al., 2010 ), at least in part because enrollment rates have risen over time among those with less academic preparation in the K-12 years.

As with family role transitions, higher education patterns vary considerably across diverse segments of the population ( Brock, 2010 ). Enrollment rates in both 2- and 4-year colleges are higher for women than for men and for whites than for nonwhites ( Holzer and Dunlop, 2013 ; Payne, 2012 ). In fact, enrollment figures are at about 50 percent for African American and Latino/a young adults by the time they reach age 25 (compared with the population figure of 59 percent noted above), with even greater gender differences within these groups ( Payne, 2012 ). The starkest disparities across these groups appear in graduation rates from 4-year colleges and universities, with women earning more bachelor's degrees than men and whites earning more bachelor's degrees than minorities ( Payne, 2012 ). There are also growing disparities in educational attainment between young adults from poor and middle/upper-income families.

Thus, modal or average patterns of higher education enrollment and completion during young adulthood typically subsume a great deal of heterogeneity. This heterogeneity is clearly evident in the growing immigrant population, as many first- and second-generation immigrants have rates of college enrollment and graduation higher than those of the general population, while other immigrant groups (e.g., unauthorized immigrants, the children of Mexican immigrants) are significantly underrepresented in higher education ( Baum and Flores, 2011 ).

Turning to employment, the increased enrollment of young adults in higher education has had a major impact on employment rates, as educational commitments often preclude substantial work commitments. Yet even taking into account the substitution of education for employment in the late teens and early 20s, a key feature of the employment status of young adults is unemployment, or being out of work when one wants to be working. Indeed, the unemployment rate for the under-25 population is twice that of the general population ( Dennett and Modestino, 2013 ). This elevated unemployment among young adults is not altogether new; they have always struggled more than older adults to find and hold onto jobs. Still, this age-related disparity in unemployment has been growing in recent decades, and it has become especially marked since the start of the Great Recession in late 2007. Across all education levels and school enrollment statuses, young adult unemployment has increased significantly in the last several years relative to pre-recession years ( Dennett and Modestino, 2013 ). Furthermore, among those who obtain jobs, many earn considerably less than similar demographic groups did in the past.

Another school-work scenario is “idleness”—when young adults are neither enrolled in higher education nor employed for pay. Many idle young adults are not just unemployed but have dropped out of the labor force altogether, sometimes for very long periods of time, in response to the lower wages and benefits now available to those with high school or less education, especially among young men ( Dennett and Modestino, 2013 ). As discussed in Chapter 4 , rates of idleness and labor force nonparticipation tend to be higher (and are becoming more so) for young African American men, who have been hit harder than other groups by broad changes in the economy and the labor market ( Dennett and Modestino, 2013 ). Their lack of employment activity often becomes reinforced over time if they have a criminal record or if they are in arrears on child support they have been ordered to pay as noncustodial parents.

The sequencing of education and employment in young adulthood also is changing in important ways. A traditional school-work path was college enrollment and graduation in the late teens and early 20s, followed by full-time entry into the labor market in the mid-20s (with some pursuing more education and pushing back full-time employment). This primarily unidirectional path is related to higher economic returns throughout adulthood. Another traditional path was bypassing higher education altogether to enter the labor market directly after secondary schooling, a path related to higher earnings than those of other young adults in the short term but lower earnings in the long term.

In the contemporary economic climate of stagnant or lower real wages and generally higher costs of financing education (despite the rising availability of federal Pell grants to help low-income students pay for college), more young adults are trying to participate in higher education and employment at the same time or moving back and forth between the two. These mixed or bidirectional paths—which tend to be more common among young adults from more socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds—are one of several explanations for the lower odds of completing higher education among low-income or minority students ( Bernhardt et al., 2001 ; Goldin and Katz, 2008 ).

Overall, young adults in the United States are attempting to gain more education, and more education improves employment prospects during young adulthood and beyond (not to mention affecting many nonemployment outcomes, such as civic engagement; see Chapters 4 and 5 ). Yet an unstable economic context and the high immediate costs of financing higher education mean that the process of gaining human capital to improve future job prospects and realize other benefits of education is not so simple, especially for some young adults from more disadvantaged socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups.

Young adults' successes or failures in education and employment are integrally linked to their health. In general, the more educated a young adult becomes, the healthier she or he will be in adulthood, whereas lower educational attainment and occupational success is associated with poor health status, and involuntary loss of employment can have a negative impact on both physical and behavioral health. But the causal direction is also reversed in many cases: young adults with disabilities and chronic health conditions may find it significantly more difficult to obtain higher education and employment.

- SOCIAL/ECONOMIC CHANGES AND THE REFASHIONING OF YOUNG ADULTHOOD

General physical and psychological development and the transition to major family and socioeconomic roles are personal experiences of individual young adults. Yet how these developmental and social processes unfold—and their timing and sequencing—is shaped by broader societal and historical forces ( Shanahan, 2000 ). In other words, what is happening among young adults today reflects the larger context in which they find themselves, through no choice or fault of their own.

First, the U.S. economy has undergone substantial restructuring over the last several decades in ways that have radically altered the landscape of risk and opportunity in young adulthood. The traditional manufacturing and blue-collar sectors of the economy have shrunk, while the information and service sectors have grown. Even within these sectors, earnings inequality has increased dramatically, both across and within occupational categories. There are now broad strata of secure and stable professional and managerial jobs with benefits at the top of the labor market, and broad strata of insecure and unstable jobs with low wages and virtually no employer-provided benefits at the bottom (although these low wages can often be supplemented by a range of tax credits and publicly provided health care and child care benefits). The middle of the earnings distribution has diminished somewhat, however, especially in the production and clerical job categories that used to be accessible to high school graduates (and even dropouts in the manufacturing and blue-collar sectors).

As a result, the returns to higher education—how much more one earns over a lifetime by getting a college or graduate degree—have risen to historic levels, especially in specialized fields that support high-growth sectors of the economy. Increasingly, the way to achieve a middle-class level of earnings is to develop human capital by staying in school longer. A high school diploma, which used to be a ticket to the middle class, does not support mobility as it did in the past ( Bernhardt et al., 2001 ; Goldin and Katz, 2008 ; Schneider, 2007 ); most jobs now require at least some postsecondary education or training, if not a bachelor's degree or higher. At the same time that the benefits of college enrollment have increased, however, the financial costs of enrolling (and staying enrolled) also have increased, as discussed in Chapter 4 . Moreover, more students attend college without sufficient academic preparation and with very little knowledge or information about the world of colleges and universities. As a result, higher education is more economically necessary but also more difficult to attain for many young adults than in past decades.

Second, these socioeconomic changes have been accompanied by evolving norms and values regarding when young adults are expected to become independent of their parents and begin families of their own ( Johnson et al., 2011 ; Roisman et al., 2004 ). Observers of modern social trends have noted that contemporary parents believe that their active parenting role extends further into their children's life courses than was the case for parents in the past ( Fingerman et al., 2012 ). This new conceptualization of active and involved parenting as something that filters into children's 20s (and beyond) is often referred to as “helicopter” parenting ( Fingerman et al., 2012 ). At the same time, Americans are less likely to view the early 20s as an appropriate time for family formation, especially having children, and young adults themselves tend to view marriage as unsuitable for this period of life ( Teachman et al., 2000 ). Although this change in age norms has been most pronounced among the white middle class, it has pervaded diverse segments of the population in a process of cultural diffusion. Of course, changing age norms reflect changing behaviors (i.e., ideas about appropriate ages for a family transition change as people start making that transition at later ages), but age norms also shape how people view family transitions and, therefore, when they feel ready to make them ( Cherlin, 2009 ; Teachman et al., 2000 ).

These macro-level trends are, of course, related. For example, the rising returns to and costs of higher education and the insecurity of the labor market for new workers mean that young people often concentrate on school and work in their late teens and early 20s rather than committing to a partner or starting a family. In this way, the economic changes that shape schooling and work alter age norms about family formation. This impact appears to be greater for marriage than for cohabitation or parenting, as many young adults have high economic standards for entering marriage that do not apply to these other family transitions ( Edin and Kefalas, 2005 ; McLanahan, 2004 ). An economic consequence becomes a cultural influence. As discussed in Chapter 3 , these trends are also raising questions about parental obligations to provide financial support for education and other costs during this transitional period.

Overall, young adults now focus more on socioeconomic attainment than on family formation, which is lengthening the time to financial independence and keeping them tied to their families of origin. For youth from socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds, this period can then become a time of freedom and exploration. For youth from more disadvantaged backgrounds, there is a higher potential for stagnation, with supposed freedoms masking scarcer opportunities and cultural norms and economic realities not always being well aligned ( Arnett, 2004 ; Furstenberg, 2010 ). Both the timing and sequencing of young adult experiences, therefore, reflect the macro-level contexts in which young people are embedded and are closely connected to where they came from and where they are going.

A third important component of social change with implications for social roles and how they interact involves the advances in information technology in recent years. This technological revolution has reshaped American society as a whole and has been acutely felt among and driven by young adults. According to national data from the Pew Research Center, virtually all young adults use the Internet on a fairly regular basis, and nearly all have cell phones and use social media ( Lenhart, 2013 ). Moreover, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in rates of usage are not large. In fact, information technology and social media pervade most aspects of daily life among most young adults ( Lenhart, 2013 ). They are a central feature of school and work activities, keep young adults in closer contact with their parents compared with prior generations, allow young adults to greatly expand the reach of their social networks, serve as an increasingly popular venue for dating and union formation, provide new ways to increase health care access (and to improve health care delivery and facilitate the monitoring of personal health), and serve as a new context for political socialization and civic engagement ( Chan-Olmsted et al., 2013 ; Clark, 2012 ; Kreager et al., 2014 ; Turkle, 2011 ; Wegrzyn, 2014 ). Indeed, young adults are driving much of the innovation and growth of social media ( Lenhart, 2013 ). Consider a recent Harvard Business Review analysis ( Frick, 2014 ), which reports that the modal age of founders of billion-dollar Silicon Valley startups is 20-24. Thus, young adults are both consumers and creators of the new media, and the ways in which they move toward, take on, and function within adult roles are changing as a result—a theme that is revisited repeatedly in subsequent chapters.

- THE HEALTH OF YOUNG ADULTS

Thus far, the general developmental processes of young adulthood (unique in the life course if not historically specific) and the social activities and roles of young adulthood (unique in the life course and historically specific) have been discussed separately, but in reality, they are intertwined. One way to see this intertwining is to consider the health and health behaviors of young adults, which have physical, psychological, social, and structural underpinnings ( Johnson et al., 2011 ).

Developmentally, young adults are continuing to accrue and refine cognitive skills and psychological competencies for mature decision making and self-regulation, and they face fewer natural threats to physical health compared with older adults. As a result, they should engage in less risky behavior than adolescents and be in better health than older adults, both of which are true to some extent. Socially, however, they tend to live more outside the purview of their parents relative to adolescents, and they are less governed by their family's lifestyle and health habits—with less parental monitoring of sleep, curfews, peer relations, physical activity, and diet ( Harris et al., 2005 ). At the same time, compared with older adults, they are less likely to participate in work and family roles that serve as strong social controls on risk taking. And they often have less access to quality health care than younger adolescents or older adults. Consequently, some of the health advantages of young adulthood relative to adolescence or older adulthood may be undermined, and the period of vulnerability often associated with adolescence may be lengthened ( Harris et al., 2006 ; Neinstein, 2013 ; Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002 ).

Health Behavior

Table 2-1 shows the top 10 causes of death among young adults in the United States. The top five are related in part to lifestyles, behaviors, and risk taking, especially the top three (injury, homicide, and suicide). The same is true of many other causes of death just below the top five, such as HIV. In this way, young adulthood has been described as a transitional period between behavioral causes of death in adolescence and health-related causes of death in later adulthood ( Neinstein, 2013 ).

Leading Causes of Death in the United States (per 100,000 population), Ages 12-34.

Looking more closely at the top two causes of death, rates of unintentional injury and homicide are higher among young adults—especially males—than among any other age group ( CDC, 2012 ). Motor vehicle crashes account for the largest percentage of unintentional injuries, and young adults face the highest risk. Compared with those aged 26-34, young adults aged 18-25 are more likely to die or be injured in a motor vehicle crash and have more motor vehicle crash–related hospitalizations and emergency room visits ( CDC, 2012 ). Young adults also are at greatest risk of injury due to firearms; young adult males have 10 times the risk of such an injury compared with young adult females ( CDC, 2012 ).