When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

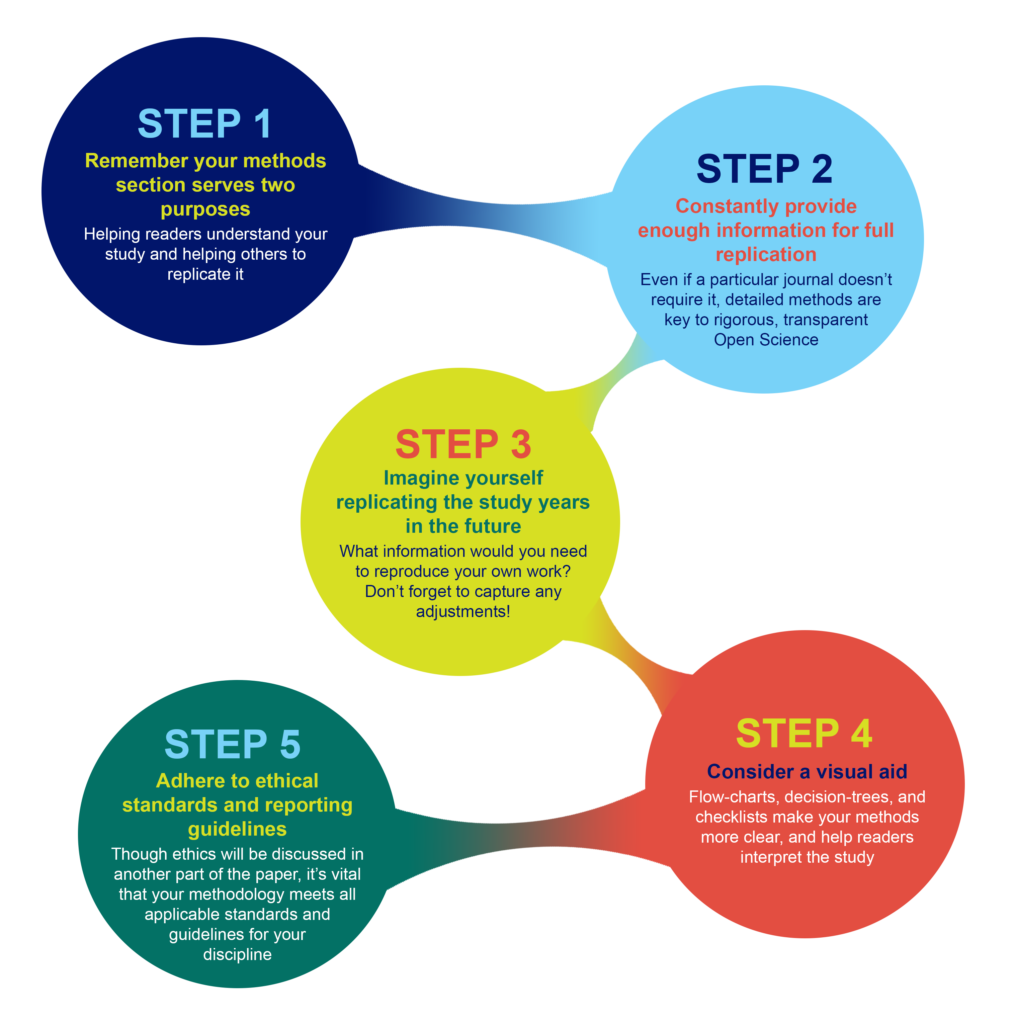

- How to Write Your Methods

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

Published on 25 February 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Your research methodology discusses and explains the data collection and analysis methods you used in your research. A key part of your thesis, dissertation, or research paper, the methodology chapter explains what you did and how you did it, allowing readers to evaluate the reliability and validity of your research.

It should include:

- The type of research you conducted

- How you collected and analysed your data

- Any tools or materials you used in the research

- Why you chose these methods

- Your methodology section should generally be written in the past tense .

- Academic style guides in your field may provide detailed guidelines on what to include for different types of studies.

- Your citation style might provide guidelines for your methodology section (e.g., an APA Style methods section ).

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

How to write a research methodology, why is a methods section important, step 1: explain your methodological approach, step 2: describe your data collection methods, step 3: describe your analysis method, step 4: evaluate and justify the methodological choices you made, tips for writing a strong methodology chapter, frequently asked questions about methodology.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Your methods section is your opportunity to share how you conducted your research and why you chose the methods you chose. It’s also the place to show that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated .

It gives your research legitimacy and situates it within your field, and also gives your readers a place to refer to if they have any questions or critiques in other sections.

You can start by introducing your overall approach to your research. You have two options here.

Option 1: Start with your “what”

What research problem or question did you investigate?

- Aim to describe the characteristics of something?

- Explore an under-researched topic?

- Establish a causal relationship?

And what type of data did you need to achieve this aim?

- Quantitative data , qualitative data , or a mix of both?

- Primary data collected yourself, or secondary data collected by someone else?

- Experimental data gathered by controlling and manipulating variables, or descriptive data gathered via observations?

Option 2: Start with your “why”

Depending on your discipline, you can also start with a discussion of the rationale and assumptions underpinning your methodology. In other words, why did you choose these methods for your study?

- Why is this the best way to answer your research question?

- Is this a standard methodology in your field, or does it require justification?

- Were there any ethical considerations involved in your choices?

- What are the criteria for validity and reliability in this type of research ?

Once you have introduced your reader to your methodological approach, you should share full details about your data collection methods .

Quantitative methods

In order to be considered generalisable, you should describe quantitative research methods in enough detail for another researcher to replicate your study.

Here, explain how you operationalised your concepts and measured your variables. Discuss your sampling method or inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as any tools, procedures, and materials you used to gather your data.

Surveys Describe where, when, and how the survey was conducted.

- How did you design the questionnaire?

- What form did your questions take (e.g., multiple choice, Likert scale )?

- Were your surveys conducted in-person or virtually?

- What sampling method did you use to select participants?

- What was your sample size and response rate?

Experiments Share full details of the tools, techniques, and procedures you used to conduct your experiment.

- How did you design the experiment ?

- How did you recruit participants?

- How did you manipulate and measure the variables ?

- What tools did you use?

Existing data Explain how you gathered and selected the material (such as datasets or archival data) that you used in your analysis.

- Where did you source the material?

- How was the data originally produced?

- What criteria did you use to select material (e.g., date range)?

The survey consisted of 5 multiple-choice questions and 10 questions measured on a 7-point Likert scale.

The goal was to collect survey responses from 350 customers visiting the fitness apparel company’s brick-and-mortar location in Boston on 4–8 July 2022, between 11:00 and 15:00.

Here, a customer was defined as a person who had purchased a product from the company on the day they took the survey. Participants were given 5 minutes to fill in the survey anonymously. In total, 408 customers responded, but not all surveys were fully completed. Due to this, 371 survey results were included in the analysis.

Qualitative methods

In qualitative research , methods are often more flexible and subjective. For this reason, it’s crucial to robustly explain the methodology choices you made.

Be sure to discuss the criteria you used to select your data, the context in which your research was conducted, and the role you played in collecting your data (e.g., were you an active participant, or a passive observer?)

Interviews or focus groups Describe where, when, and how the interviews were conducted.

- How did you find and select participants?

- How many participants took part?

- What form did the interviews take ( structured , semi-structured , or unstructured )?

- How long were the interviews?

- How were they recorded?

Participant observation Describe where, when, and how you conducted the observation or ethnography .

- What group or community did you observe? How long did you spend there?

- How did you gain access to this group? What role did you play in the community?

- How long did you spend conducting the research? Where was it located?

- How did you record your data (e.g., audiovisual recordings, note-taking)?

Existing data Explain how you selected case study materials for your analysis.

- What type of materials did you analyse?

- How did you select them?

In order to gain better insight into possibilities for future improvement of the fitness shop’s product range, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 8 returning customers.

Here, a returning customer was defined as someone who usually bought products at least twice a week from the store.

Surveys were used to select participants. Interviews were conducted in a small office next to the cash register and lasted approximately 20 minutes each. Answers were recorded by note-taking, and seven interviews were also filmed with consent. One interviewee preferred not to be filmed.

Mixed methods

Mixed methods research combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. If a standalone quantitative or qualitative study is insufficient to answer your research question, mixed methods may be a good fit for you.

Mixed methods are less common than standalone analyses, largely because they require a great deal of effort to pull off successfully. If you choose to pursue mixed methods, it’s especially important to robustly justify your methods here.

Next, you should indicate how you processed and analysed your data. Avoid going into too much detail: you should not start introducing or discussing any of your results at this stage.

In quantitative research , your analysis will be based on numbers. In your methods section, you can include:

- How you prepared the data before analysing it (e.g., checking for missing data , removing outliers , transforming variables)

- Which software you used (e.g., SPSS, Stata or R)

- Which statistical tests you used (e.g., two-tailed t test , simple linear regression )

In qualitative research, your analysis will be based on language, images, and observations (often involving some form of textual analysis ).

Specific methods might include:

- Content analysis : Categorising and discussing the meaning of words, phrases and sentences

- Thematic analysis : Coding and closely examining the data to identify broad themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying communication and meaning in relation to their social context

Mixed methods combine the above two research methods, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches into one coherent analytical process.

Above all, your methodology section should clearly make the case for why you chose the methods you did. This is especially true if you did not take the most standard approach to your topic. In this case, discuss why other methods were not suitable for your objectives, and show how this approach contributes new knowledge or understanding.

In any case, it should be overwhelmingly clear to your reader that you set yourself up for success in terms of your methodology’s design. Show how your methods should lead to results that are valid and reliable, while leaving the analysis of the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results for your discussion section .

- Quantitative: Lab-based experiments cannot always accurately simulate real-life situations and behaviours, but they are effective for testing causal relationships between variables .

- Qualitative: Unstructured interviews usually produce results that cannot be generalised beyond the sample group , but they provide a more in-depth understanding of participants’ perceptions, motivations, and emotions.

- Mixed methods: Despite issues systematically comparing differing types of data, a solely quantitative study would not sufficiently incorporate the lived experience of each participant, while a solely qualitative study would be insufficiently generalisable.

Remember that your aim is not just to describe your methods, but to show how and why you applied them. Again, it’s critical to demonstrate that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated.

1. Focus on your objectives and research questions

The methodology section should clearly show why your methods suit your objectives and convince the reader that you chose the best possible approach to answering your problem statement and research questions .

2. Cite relevant sources

Your methodology can be strengthened by referencing existing research in your field. This can help you to:

- Show that you followed established practice for your type of research

- Discuss how you decided on your approach by evaluating existing research

- Present a novel methodological approach to address a gap in the literature

3. Write for your audience

Consider how much information you need to give, and avoid getting too lengthy. If you are using methods that are standard for your discipline, you probably don’t need to give a lot of background or justification.

Regardless, your methodology should be a clear, well-structured text that makes an argument for your approach, not just a list of technical details and procedures.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research. Developing your methodology involves studying the research methods used in your field and the theories or principles that underpin them, in order to choose the approach that best matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. interviews, experiments , surveys , statistical tests ).

In a dissertation or scientific paper, the methodology chapter or methods section comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/methodology/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide.

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

Writing the research paper.

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

Before Writing the Paper

Methods, thesis, and hypothesis, clarity, precision, and academic expression, format your paper, typical problems, a few suggestions, avoid plagiarism.

- Presenting the Research Paper

- Try to find a subject that really interests you.

- While you explore the topic, narrow or broaden your target and focus on something that gives the most promising results.

- Don't choose a huge subject if you have to write a 3 page long paper, and broaden your topic sufficiently if you have to submit at least 25 pages.

- Consult your class instructor (and your classmates) about the topic.

- Find primary and secondary sources in the library.

- Read and critically analyse them.

- Take notes.

- Compile surveys, collect data, gather materials for quantitative analysis (if these are good methods to investigate the topic more deeply).

- Come up with new ideas about the topic. Try to formulate your ideas in a few sentences.

- Review your notes and other materials and enrich the outline.

- Try to estimate how long the individual parts will be.

- Do others understand what you want to say?

- Do they accept it as new knowledge or relevant and important for a paper?

- Do they agree that your thoughts will result in a successful paper?

- Qualitative: gives answers on questions (how, why, when, who, what, etc.) by investigating an issue

- Quantitative:requires data and the analysis of data as well

- the essence, the point of the research paper in one or two sentences.

- a statement that can be proved or disproved.

- Be specific.

- Avoid ambiguity.

- Use predominantly the active voice, not the passive.

- Deal with one issue in one paragraph.

- Be accurate.

- Double-check your data, references, citations and statements.

Academic Expression

- Don't use familiar style or colloquial/slang expressions.

- Write in full sentences.

- Check the meaning of the words if you don't know exactly what they mean.

- Avoid metaphors.

- Almost the rough content of every paragraph.

- The order of the various topics in your paper.

- On the basis of the outline, start writing a part by planning the content, and then write it down.

- Put a visible mark (which you will later delete) where you need to quote a source, and write in the citation when you finish writing that part or a bigger part.

- Does the text make sense?

- Could you explain what you wanted?

- Did you write good sentences?

- Is there something missing?

- Check the spelling.

- Complete the citations, bring them in standard format.

Use the guidelines that your instructor requires (MLA, Chicago, APA, Turabian, etc.).

- Adjust margins, spacing, paragraph indentation, place of page numbers, etc.

- Standardize the bibliography or footnotes according to the guidelines.

- EndNote and EndNote Basic by UCLA Library Last Updated Mar 18, 2024 974 views this year

- Zotero by UCLA Library Last Updated Apr 23, 2024 678 views this year

(Based on English Composition 2 from Illinois Valley Community College):

- Weak organization

- Poor support and development of ideas

- Weak use of secondary sources

- Excessive errors

- Stylistic weakness

When collecting materials, selecting research topic, and writing the paper:

- Be systematic and organized (e.g. keep your bibliography neat and organized; write your notes in a neat way, so that you can find them later on.

- Use your critical thinking ability when you read.

- Write down your thoughts (so that you can reconstruct them later).

- Stop when you have a really good idea and think about whether you could enlarge it to a whole research paper. If yes, take much longer notes.

- When you write down a quotation or summarize somebody else's thoughts in your notes or in the paper, cite the source (i.e. write down the author, title, publication place, year, page number).

- If you quote or summarize a thought from the internet, cite the internet source.

- Write an outline that is detailed enough to remind you about the content.

- Read your paper for yourself or, preferably, somebody else.

- When you finish writing, check the spelling;

- Use the citation form (MLA, Chicago, or other) that your instructor requires and use it everywhere.

Plagiarism : somebody else's words or ideas presented without citation by an author

- Cite your source every time when you quote a part of somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you summarize a thought from somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you use a source (quote or summarize) from the Internet.

Consult the Citing Sources research guide for further details.

- << Previous: Writing a Research Proposal

- Next: Presenting the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 12:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Methods

Definition:

Research Methods refer to the techniques, procedures, and processes used by researchers to collect , analyze, and interpret data in order to answer research questions or test hypotheses. The methods used in research can vary depending on the research questions, the type of data that is being collected, and the research design.

Types of Research Methods

Types of Research Methods are as follows:

Qualitative research Method

Qualitative research methods are used to collect and analyze non-numerical data. This type of research is useful when the objective is to explore the meaning of phenomena, understand the experiences of individuals, or gain insights into complex social processes. Qualitative research methods include interviews, focus groups, ethnography, and content analysis.

Quantitative Research Method

Quantitative research methods are used to collect and analyze numerical data. This type of research is useful when the objective is to test a hypothesis, determine cause-and-effect relationships, and measure the prevalence of certain phenomena. Quantitative research methods include surveys, experiments, and secondary data analysis.

Mixed Method Research

Mixed Method Research refers to the combination of both qualitative and quantitative research methods in a single study. This approach aims to overcome the limitations of each individual method and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. This approach allows researchers to gather both quantitative data, which is often used to test hypotheses and make generalizations about a population, and qualitative data, which provides a more in-depth understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

Key Differences Between Research Methods

The following Table shows the key differences between Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Research Methods

Examples of Research Methods

Examples of Research Methods are as follows:

Qualitative Research Example:

A researcher wants to study the experience of cancer patients during their treatment. They conduct in-depth interviews with patients to gather data on their emotional state, coping mechanisms, and support systems.

Quantitative Research Example:

A company wants to determine the effectiveness of a new advertisement campaign. They survey a large group of people, asking them to rate their awareness of the product and their likelihood of purchasing it.

Mixed Research Example:

A university wants to evaluate the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student performance. They collect both quantitative data (such as test scores) and qualitative data (such as feedback from students and teachers) to get a complete picture of the impact of the new method.

Applications of Research Methods

Research methods are used in various fields to investigate, analyze, and answer research questions. Here are some examples of how research methods are applied in different fields:

- Psychology : Research methods are widely used in psychology to study human behavior, emotions, and mental processes. For example, researchers may use experiments, surveys, and observational studies to understand how people behave in different situations, how they respond to different stimuli, and how their brains process information.

- Sociology : Sociologists use research methods to study social phenomena, such as social inequality, social change, and social relationships. Researchers may use surveys, interviews, and observational studies to collect data on social attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

- Medicine : Research methods are essential in medical research to study diseases, test new treatments, and evaluate their effectiveness. Researchers may use clinical trials, case studies, and laboratory experiments to collect data on the efficacy and safety of different medical treatments.

- Education : Research methods are used in education to understand how students learn, how teachers teach, and how educational policies affect student outcomes. Researchers may use surveys, experiments, and observational studies to collect data on student performance, teacher effectiveness, and educational programs.

- Business : Research methods are used in business to understand consumer behavior, market trends, and business strategies. Researchers may use surveys, focus groups, and observational studies to collect data on consumer preferences, market trends, and industry competition.

- Environmental science : Research methods are used in environmental science to study the natural world and its ecosystems. Researchers may use field studies, laboratory experiments, and observational studies to collect data on environmental factors, such as air and water quality, and the impact of human activities on the environment.

- Political science : Research methods are used in political science to study political systems, institutions, and behavior. Researchers may use surveys, experiments, and observational studies to collect data on political attitudes, voting behavior, and the impact of policies on society.

Purpose of Research Methods

Research methods serve several purposes, including:

- Identify research problems: Research methods are used to identify research problems or questions that need to be addressed through empirical investigation.

- Develop hypotheses: Research methods help researchers develop hypotheses, which are tentative explanations for the observed phenomenon or relationship.

- Collect data: Research methods enable researchers to collect data in a systematic and objective way, which is necessary to test hypotheses and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Analyze data: Research methods provide tools and techniques for analyzing data, such as statistical analysis, content analysis, and discourse analysis.

- Test hypotheses: Research methods allow researchers to test hypotheses by examining the relationships between variables in a systematic and controlled manner.

- Draw conclusions : Research methods facilitate the drawing of conclusions based on empirical evidence and help researchers make generalizations about a population based on their sample data.

- Enhance understanding: Research methods contribute to the development of knowledge and enhance our understanding of various phenomena and relationships, which can inform policy, practice, and theory.

When to Use Research Methods

Research methods are used when you need to gather information or data to answer a question or to gain insights into a particular phenomenon.

Here are some situations when research methods may be appropriate:

- To investigate a problem : Research methods can be used to investigate a problem or a research question in a particular field. This can help in identifying the root cause of the problem and developing solutions.

- To gather data: Research methods can be used to collect data on a particular subject. This can be done through surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, and more.

- To evaluate programs : Research methods can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a program, intervention, or policy. This can help in determining whether the program is meeting its goals and objectives.

- To explore new areas : Research methods can be used to explore new areas of inquiry or to test new hypotheses. This can help in advancing knowledge in a particular field.

- To make informed decisions : Research methods can be used to gather information and data to support informed decision-making. This can be useful in various fields such as healthcare, business, and education.

Advantages of Research Methods

Research methods provide several advantages, including:

- Objectivity : Research methods enable researchers to gather data in a systematic and objective manner, minimizing personal biases and subjectivity. This leads to more reliable and valid results.

- Replicability : A key advantage of research methods is that they allow for replication of studies by other researchers. This helps to confirm the validity of the findings and ensures that the results are not specific to the particular research team.

- Generalizability : Research methods enable researchers to gather data from a representative sample of the population, allowing for generalizability of the findings to a larger population. This increases the external validity of the research.

- Precision : Research methods enable researchers to gather data using standardized procedures, ensuring that the data is accurate and precise. This allows researchers to make accurate predictions and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Efficiency : Research methods enable researchers to gather data efficiently, saving time and resources. This is especially important when studying large populations or complex phenomena.

- Innovation : Research methods enable researchers to develop new techniques and tools for data collection and analysis, leading to innovation and advancement in the field.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The methods section of a research paper provides the information by which a study’s validity is judged. The method section answers two main questions: 1) How was the data collected or generated? 2) How was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and written in the past tense.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you choose affects the results and, by extension, how you likely interpreted those results.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and it misappropriates interpretations of findings .

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. Your methodology section of your paper should make clear the reasons why you chose a particular method or procedure .

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The research method must be appropriate to the objectives of the study . For example, be sure you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring . For any problems that did arise, you must describe the ways in which their impact was minimized or why these problems do not affect the findings in any way that impacts your interpretation of the data.

- Often in social science research, it is useful for other researchers to adapt or replicate your methodology. Therefore, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow others to use or replicate the study . This information is particularly important when a new method had been developed or an innovative use of an existing method has been utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article . Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The empirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences. This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation .

- The interpretative group is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . This research method allows you to recognize your connection to the subject under study. Because the interpretative group focuses more on subjective knowledge, it requires careful interpretation of variables.

II. Content

An effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods should have a clear connection with your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is unsuited to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors?

- Provide background and rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a rationale for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of statisics being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate.

- Address potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE : Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but to the point. Don’t provide any background information that doesn’t directly help the reader to understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how it was analyzed. Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. NOTE: An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional approach to doing the method; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall research process. Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose. Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section. Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics. Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship . S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

- << Previous: What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Quantitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Need Help Locating Statistics?

Resources for locating data and statistics can be found here:

Statistics & Data Research Guide

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numeric and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantitative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing data does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Design for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Composition and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); "A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper." Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

Strengths of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative researchers try to recognize and isolate specific variables contained within the study framework, seek correlation, relationships and causality, and attempt to control the environment in which the data is collected to avoid the risk of variables, other than the one being studied, accounting for the relationships identified.

Among the specific strengths of using quantitative methods to study social science research problems:

- Allows for a broader study, involving a greater number of subjects, and enhancing the generalization of the results;

- Allows for greater objectivity and accuracy of results. Generally, quantitative methods are designed to provide summaries of data that support generalizations about the phenomenon under study. In order to accomplish this, quantitative research usually involves few variables and many cases, and employs prescribed procedures to ensure validity and reliability;

- Applying well established standards means that the research can be replicated, and then analyzed and compared with similar studies;

- You can summarize vast sources of information and make comparisons across categories and over time; and,

- Personal bias can be avoided by keeping a 'distance' from participating subjects and using accepted computational techniques .

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Limitations of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods presume to have an objective approach to studying research problems, where data is controlled and measured, to address the accumulation of facts, and to determine the causes of behavior. As a consequence, the results of quantitative research may be statistically significant but are often humanly insignificant.

Some specific limitations associated with using quantitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include:

- Quantitative data is more efficient and able to test hypotheses, but may miss contextual detail;

- Uses a static and rigid approach and so employs an inflexible process of discovery;

- The development of standard questions by researchers can lead to "structural bias" and false representation, where the data actually reflects the view of the researcher instead of the participating subject;

- Results provide less detail on behavior, attitudes, and motivation;

- Researcher may collect a much narrower and sometimes superficial dataset;

- Results are limited as they provide numerical descriptions rather than detailed narrative and generally provide less elaborate accounts of human perception;

- The research is often carried out in an unnatural, artificial environment so that a level of control can be applied to the exercise. This level of control might not normally be in place in the real world thus yielding "laboratory results" as opposed to "real world results"; and,

- Preset answers will not necessarily reflect how people really feel about a subject and, in some cases, might just be the closest match to the preconceived hypothesis.

Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods

- Next: Insiderness >>

- Last Updated: Apr 29, 2024 1:49 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Open access

- Published: 29 April 2024

Correction: Impact of sampling and data collection methods on maternity survey response: a randomised controlled trial of paper and push‑to‑web surveys and a concurrent social media survey

- Siân Harrison 1 ,

- Fiona Alderdice 1 &

- Maria A. Quigley 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 24 , Article number: 100 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The Original Article was published on 12 January 2023

Correction: BMC Med Res Methodol 23, 10 (2023)

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-01833-8

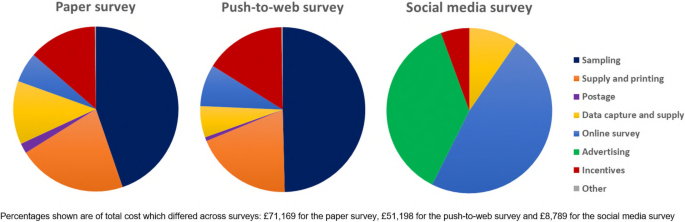

Following publication of the original article [ 1 ], the authors reported an error in the Fig. 4 : the colours in the pie charts in Fig. 4 do not all correspond with the legend. See the Fig. 4 corrected.

Breakdown of total costs across the surveys

The original article [ 1 ] has been updated.

Harrison S, Alderdice F, Quigley MA. Impact of sampling and data collection methods on maternity survey response: a randomised controlled trial of paper and push-to-web surveys and a concurrent social media survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-01833-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

NIHR Policy Research Unit in Maternal and Neonatal Health and Care, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Old Road Campus Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK

Siân Harrison, Fiona Alderdice & Maria A. Quigley

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Siân Harrison .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Harrison, S., Alderdice, F. & Quigley, M.A. Correction: Impact of sampling and data collection methods on maternity survey response: a randomised controlled trial of paper and push‑to‑web surveys and a concurrent social media survey. BMC Med Res Methodol 24 , 100 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-024-02216-3

Download citation

Published : 29 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-024-02216-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Home

- Article citations

- Biomedical & Life Sci.

- Business & Economics

- Chemistry & Materials Sci.

- Computer Sci. & Commun.

- Earth & Environmental Sci.

- Engineering

- Medicine & Healthcare

- Physics & Mathematics

- Social Sci. & Humanities

Journals by Subject

- Biomedical & Life Sciences

- Chemistry & Materials Science

- Computer Science & Communications

- Earth & Environmental Sciences

- Social Sciences & Humanities

- Paper Submission

- Information for Authors

- Peer-Review Resources

- Open Special Issues

- Open Access Statement

- Frequently Asked Questions

Publish with us

Article citations more>>.

Crossman, A. (2020) An Overview of Qualitative Research Methods. Direct Observation, Interviews, Participation, Immersion, Focus Groups. Thought Co. https://www.thoughtco.com/qualitative-research-methods-3026555

has been cited by the following article:

TITLE: Grounded Theory as an Analytical Tool to Explore Housing Decisions Related to Living in the Vicinity of Industrial Wind Turbines

KEYWORDS: Wind Turbines , Vacated/Abandoned Homes , Qualitative

JOURNAL NAME: Open Access Library Journal , Vol.8 No.3 , March 26, 2021

ABSTRACT: Background: Some people living near wind turbines have reported adverse health effects and taken the step to vacate/abandon their homes, while others contemplate doing so or have decided to remain in their homes. Research on the extent and outcomes of these events is lacking. To date, our preliminary findings and an overview of results have been published in the scientific literature. Methods: This study utilized a qualitative methodology, specifically Grounded Theory, to interview 67 residents of Ontario living within 10 km of an industrial wind turbine project. Objectives: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research each has strengths and weaknesses in addressing particular research questions. The purpose of this article is to compare the qualitative and quantitative methodologies and to describe the benefits of having used a qualitative methodology, specifically Grounded Theory, to explore the events that influenced families living within 10 km of wind energy facilities to contemplate vacating their homes and to formulate a substantive theory regarding these housing decisions. Results: It was found that research into the impacts of siting industrial wind turbines in a rural residential population can be challenging for a quantitative methodological approach due to factors such as low population density, obtaining a sufficient sample, and achieving statistical power and statistical significance. We conclude that the Grounded Theory methodology was applicable to this study as it assisted with the development of a coherent theory which explained participants’ housing decisions. Discussion: This paper assesses the appropriateness of a qualitative methodology for conducting the vacated/abandoned home study. Through the utilization of the qualitative Grounded Theory methodology, government authorities, researchers, medical and health practitioners, social scientists and policy makers with an interest in health policy and disease prevention have the opportunity to gain an awareness of the potential risk of placing wind energy projects near family homes.

Related Articles: