Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors.

Now streaming on:

At a time when it seems as if cinema experiences a new technological breakthrough every few months, it's oddly comforting that moviegoers can still be hooked by a film that's presented as being one unbroken shot. Granted, it's not a new idea, but the concept of an extended single shot, whether the shot is meant to stretch for an entire movie, or just serve as the focus for an especially showy scene, still has the power to excite viewers on some basic level. “1917,” the new film from Sam Mendes , is the latest attempt at the feature-length single-shot approach, and its technical accomplishments cannot be denied. But the film is so obsessed with its particular technique that it doesn’t leave room for the other things we also go to the movies for—little things like a strong story, interesting characters, or a reason for existing other than as a feat of technical derring-do. Sitting through it is like watching someone else playing a video game for two solid hours, and not an especially compelling one at that.

As indicated by the title, “1917” is set amidst the turmoil of World War I and takes place in and around the so-called “no man’s land” in northern France separating British and German troops. Two young corporals, Blake ( Dean-Charles Chapman ) and Schofield ( George MacKay ), are awoken from what could have only been a few minutes of sleep and ordered to report for a new assignment. A few miles away, another company, one that includes Blake’s brother, has planned an attack to commence in a few hours designed to push the Germans back even further following a recent retreat. However, recent intelligence suggests that the retreat is a ruse that will land them in ambush that will cost thousands of British lives. With the radio lines down, Blake and Schofield are ordered to head on foot to that company in order to call off the attack before it can commence, a journey that will force them to travel through enemy territory. Of course, the two have been assured that where they will be crossing is safe enough, but the tension within the soldiers they meet as they get closer to the front, and the recent nature of the carnage they witness when they first go over the top, suggests otherwise. And yet, that first glimpse of the literal Hell on earth they must journey through is only a taste of what they have to endure—at one point, one of them inadvertently plunges a hand recently sliced by barbed wire into the open wound of a corpse and that turns out to be one of the less excruciating moments in store for them.

“1917” essentially wants to do for World War I what “ Saving Private Ryan ” did for World War II and “ Platoon ” did for Vietnam—provide a visceral depiction of the horrors of combat for viewers whose only frame of reference for those conflicts has been history books or other movies. This is not a bad idea for a film, but "1917" never quite comes alive in the way that Mendes presumably hoped, and much of the reason for that is the direct result of how he has deployed to tell his story. Now, I enjoy an extended single-shot sequence that exists solely for a filmmaker to show off their technical finesse, but if I were to make a list of the most effective one-shot sequences, they would be the ones that are so absorbing for other reasons that we don’t even register at first that they have been done in what looks like one long take. Take the famous opening scene in Orson Welles' “ Touch of Evil ,” for example. Yes, it is a technical marvel. But at the same time Welles was pulling off this trick with the aid of cinematographer Russell Metty , he was setting up the story and introducing several of the key characters quickly and efficiently. When he did finally make a cut, it came as a genuine shock.

By comparison, there is hardly a moment to be had in “1917” in which Mendes is not calling out for viewers to notice all the technical brilliance on display. Taken strictly on those terms, the film is undeniably impressive— Roger Deakins is one of the all-time great cinematographers and his work here on what must have been a fiendishly challenging shoot is as impressive as anything he has done. The problem is that the visual conceit can’t help but draw attention to itself throughout, whether it is due to the increasingly showy camera moves or the sometimes awkward methods that are deployed to camouflage the edits and which begin to stick out more and more. (Oddly enough, the most blatantly obvious method used to hide a cut—one of the characters being briefly knocked unconscious—is actually the most dramatically effective of the bunch.) Instead of gradually fading into the background in order to make room for elements of a more dramatic or emotional nature, the distracting technique remains front and center.

Granted, one of the reasons that the visual style ends up dominating the proceedings is because there isn’t really much of anything on hand here that has much chance of stealing focus. The storyline concocted by Mendes and co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns too often feels like an amalgamation of such classic WWI films as "The Big Parade," “All Quiet on the Western Front” and " Paths of Glory ." At certain points, the story stops dead for brief appearances by familiar faces like Colin Firth , Benedict Cumberbatch and Mark Strong in exposition-heavy sequences that feel exactly like the cut scenes that appear between the different levels in video games.

“1917” is not entirely without interest. This was clearly a fiendishly complicated project to stage and execute and there are some scenes (such as an especially tense one set in a seemingly abandoned shelter that contains a few nasty surprises), that are legitimate knockouts. And yet, for all of its technical expertise, little of it helps viewers to care about the characters or what might happen to them. When all is said and done, "1917" is basically a gimmick film. If that is enough for you, you may admire it for its accomplishments. Personally, I wanted more.

Peter Sobczynski

A moderately insightful critic, full-on Swiftie and all-around bon vivant , Peter Sobczynski, in addition to his work at this site, is also a contributor to The Spool and can be heard weekly discussing new Blu-Ray releases on the Movie Madness podcast on the Now Playing network.

Now playing

Brian Tallerico

Monica Castillo

The Listener

Matt zoller seitz.

In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon

Clint worthington.

Rebel Moon - Part Two: The Scargiver

Simon abrams.

Film Credits

1917 (2019)

Rated R for violence, some disturbing images, and language.

119 minutes

George MacKay as Schofield

Dean-Charles Chapman as Blake

Mark Strong as Captain Smith

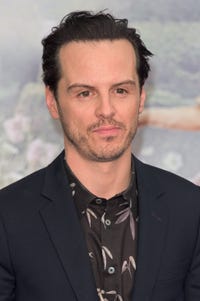

Andrew Scott as Lieutenant Leslie

Richard Madden as Lieutenant Blake

Benedict Cumberbatch as MacKenzie

- Krysty Wilson-Cairns

Cinematographer

- Roger Deakins

- Thomas Newman

Latest blog posts

Sonic the Hedgehog Franchise Moves to Streaming with Entertaining Knuckles

San Francisco Silent Film Festival Highlights Unearthed Treasures of Film History

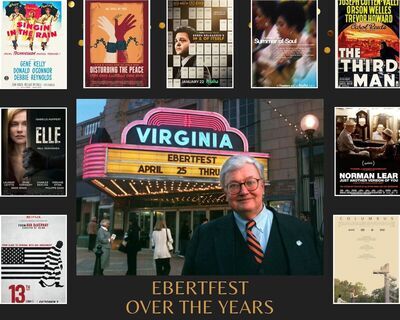

Ebertfest Film Festival Over the Years

The 2024 Chicago Palestine Film Festival Highlights

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Fandango at Home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Challengers Link to Challengers

- Abigail Link to Abigail

- Arcadian Link to Arcadian

New TV Tonight

- The Jinx: Season 2

- Knuckles: Season 1

- THEM: The Scare: Season 2

- Velma: Season 2

- The Big Door Prize: Season 2

- Secrets of the Octopus: Season 1

- Dead Boy Detectives: Season 1

- Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story: Season 1

- We're Here: Season 4

Most Popular TV on RT

- Baby Reindeer: Season 1

- Fallout: Season 1

- The Sympathizer: Season 1

- Ripley: Season 1

- Shōgun: Season 1

- 3 Body Problem: Season 1

- Under the Bridge: Season 1

- Sugar: Season 1

- A Gentleman in Moscow: Season 1

- Parasyte: The Grey: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- Under the Bridge Link to Under the Bridge

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

The Best TV Seasons Certified Fresh at 100%

Best TV Shows of 2024: Best New Series to Watch Now

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Weekend Box Office Results: Civil War Earns Second Victory in a Row

Deadpool & Wolverine : Release Date, Trailer, Cast & More

- Trending on RT

- Rebel Moon: Part Two - The Scargiver

- The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare

- Play Movie Trivia

1917 Reviews

The power of 1917 lies in its ability to tell a human story of a single mission and translate that into an account that encompasses the brutality of trench warfare.

Full Review | Sep 17, 2023

Edited to look like one continuous shot, 1917 is a mind-blowing technical achievement, elevated by Roger Deakins’ jaw-dropping cinematography, Thomas Newman’s emotionally powerful score, Sam Mendes' impeccable directing, and Lee Smith’s seamless editing.

Full Review | Original Score: A | Jul 24, 2023

Without a doubt, 1917 is technically brilliant, visually stunning, and occasionally moving. If not for its lack of fully realized characters and a deeper story, it might have been a masterpiece.

Full Review | Jul 20, 2023

With a fresh, new approach, Mendes memorializes not only his grandfather, but all the brave soldiers of WWI, reminding viewers of the individual tragedies that comprise warfare.

Full Review | Jun 5, 2023

1917 can best be described as a mediocre war film. Yes, Deakins worked his usual magic with cinematography...McKay did an adequate job...sadly, we know very little about his character, and the film does not allow him to grow...

Full Review | Apr 25, 2023

Sam Mendes’ technically dazzling and emotionally devastating World War I tale.../

Full Review | Dec 7, 2022

A technical marvel to behold that puts you right in the heart of war but ultimately leaves you emotionally cold to the resultant horror and heroics of the men involved.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Nov 11, 2022

With “1917” Sam Mendes takes his audience on a perilous journey driven by a simple but tightly-wound story soaked in an unending tension. It’s a harrowing tale of heroism, friendship, and sacrifice.

Full Review | Original Score: 4.5/5 | Aug 24, 2022

1917 is a stunning cinematic achievement.

Full Review | Original Score: 4.5/5 | Aug 23, 2022

MacKay is simultaneously appearing in the lead role of Justin Kurzel's True History of the Kelly Gang, the latest film about the local folk hero who refused to take orders from anyone.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Aug 18, 2022

For experiences like the one I had in the theatre watching this is why I love film. Constantly asking myself how they did this. Probably Sam Mendes' best movie to date. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 9/10 | Jun 23, 2022

Unfortunately I dont see what most see in 1917. Respectively, I hardly feel anything except some respect for the technical achievements. But that alone isnt enough - it actually slightly damages the film overall.

Full Review | Original Score: 6/10 | Apr 25, 2022

The film's formal indulgences distract from its dramatic potential.

Full Review | Original Score: 2/4 | Feb 22, 2022

What makes it so special is the balance between artistry and realism. Mendes reaches down into the mud and finds something beautiful.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Feb 21, 2022

1917 is a technical masterpiece that comes together with genuine powerful emotion to become a captivating work of art.

Full Review | Feb 12, 2022

We should be drawn into the personal story--director Sam Mendes loosely based the movie on his grandfather Alfred's wartime experiences--but instead, we're watching all the smoke and mirrors. It's sound and fury that could signify so much more.

Full Review | Nov 16, 2021

What could have been a gimmick in the service of a weaker narrative becomes a masterstroke here, basically denying us any let-off from the tension of what is happening on the screen.

Full Review | Sep 17, 2021

The gimmicky side of [its single take] fades juxtaposed to the perspective it offers.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Jul 31, 2021

In addition to Deakins, production designer Dennis Gassner and composer Thomas Newman also add layers of bravura artistry to create an experience that will leave you breathless, heart pounding and absolutely emotionally wrecked by the end.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jul 25, 2021

Mendes creates one of the best films released in 2019.

Full Review | Jul 23, 2021

Advertisement

Supported by

‘1917’ Review: Paths of Technical Glory

Sam Mendes directs this visually extravagant drama about young British soldiers on a perilous mission in World War I.

- Share full article

By Manohla Dargis

On June 28, 1914, a young Serbian nationalist assassinated the presumptive heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, thus starting World War I. That, at any rate, is the familiar way that the origins for this war have been shaped into a story, even if historians agree the genesis of the conflict is far more complicated. None of those complications and next to no history, though, have made it into “1917,” a carefully organized and sanitized war picture from Sam Mendes that turns one of the most catastrophic episodes in modern times into an exercise in preening showmanship.

The story is simple. It opens on April 6, 1917, with Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay), British soldiers stationed in France, receiving new orders. They are to deliver a message to troops at the front line who are readying an assault on the Germans, who have retreated. (Coincidentally or not, April 6 is the date that the United States formally entered the war.) The British command, however, believes that the German withdrawal is a trap, an operational Trojan horse. The two messengers need to carry the dispatch ordering the waiting British troops to stand down, thereby saving countless lives.

It’s the usual action-movie setup — a mission, extraordinary odds, ready-made heroes — but with trenches, barbed wire and a largely faceless threat. Blake jumps on the assignment because his brother is among the troops preparing the assault. Schofield takes orders more reluctantly, having already survived the Battle of the Somme , with its million-plus casualties. The modest difference in attitude between the messengers will vanish, presumably because any real criticism — including any skepticism about this or any war — might impede the movie’s embrace of heroic individualism for the greater good, which here largely translates as vague national struggle and sacrifice.

What complicates the movie is that it has been created to look like it was made with a single continuous shot. In service of this illusion, the editing has been obscured, though there are instances — an abrupt transition to black, an eruption of thick dust — where the seams almost show. Throughout, the camera remains fluid, its point of view unfixed. At times, it shows you what Blake and Schofield see, though it sometimes moves like another character. Like a silent yet aggressively restless unit member, it rushes before or alongside or behind the messengers as they snake through the mazy trenches and cross into No Man’s Land, the nightmarish expanse between the fronts.

The idea behind the camerawork seems to be to bring viewers close to the action, so you can share what Blake and Schofield endure each step of the way. Mostly, though, the illusion of seamlessness draws attention away from the messengers, who are only lightly sketched in, and toward Roger Deakins’s cinematography and, by extension, Mendes’s filmmaking. Whether the camera is figuratively breathing down Blake’s and Schofield’s necks or pulling back to show them creeping inside a water-filled crater as big as a swimming pool, you are always keenly aware of the technical hurdles involved in getting the characters from here to there, from this trench to that crater.

In another movie, such demonstrative self-reflexivity might have been deployed to productive effect; here, it registers as grandstanding. It’s too bad and it’s frustrating, because the two leads make appealing company: The round-faced Chapman brings loose, affable charm to his role, while MacKay, a talented actor who’s all sharp angles, primarily delivers reactive intensity. This lack of nuance can be blamed on Mendes, who throughout seems far more interested in the movie’s machinery than in the human costs of war or the attendant subjects — sacrifice, patriotism and so on — that puff into view like little wisps of engine steam.

The absence of history ensures that “1917” remains a palatable war simulation, the kind in which every button on every uniform has been diligently recreated, and no wound, no blown-off limb, is ghastly enough to truly horrify the audience. Here, everything looks authentic but manicured, ordered, sane, sterile. Save for a quick appearance by Andrew Scott, as an officer whose overly bright eyes and jaundiced affect suggest he’s been too long in the trenches, nothing gestures at madness. Worse, the longer this amazing race continues, the more it resembles an obstacle course by way of an Indiana Jones-style adventure, complete with a showstopping plane crash and battlefield sprint.

Mendes, who wrote the script with Krysty Wilson-Cairns, has included a note of dedication to his grandfather, Alfred H. Mendes , who served in World War I. It’s the most personal moment in a movie that, beyond its technical virtues, is intriguing only because of Britain’s current moment. Certainly, the country’s acrimonious withdrawal from the European Union makes a notable contrast with the onscreen camaraderie. And while the budget probably explains why most of the superior officers who pop in briefly are played by name actors — Colin Firth, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch — their casting also adds distinctly royal filigree to the ostensibly democratic mix.

Rated R for war violence. Running time: 1 hour 58 minutes.

Manohla Dargis has been the co-chief film critic since 2004. She started writing about movies professionally in 1987 while earning her M.A. in cinema studies at New York University, and her work has been anthologized in several books. More about Manohla Dargis

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

As “Sex and the City” became more widely available on Netflix, younger viewers have watched it with a critical eye . But its longtime millennial and Gen X fans can’t quit.

Hoa Xuande had only one Hollywood credit when he was chosen to lead “The Sympathizer,” the starry HBO adaptation of a prize-winning novel. He needed all the encouragement he could get .

Even before his new film “Civil War” was released, the writer-director Alex Garland faced controversy over his vision of a divided America with Texas and California as allies.

Theda Hammel’s directorial debut, “Stress Positions,” a comedy about millennials weathering the early days of the pandemic , will ask audiences to return to a time that many people would rather forget.

If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.

Sign up for our Watching newsletter to get recommendations on the best films and TV shows to stream and watch, delivered to your inbox.

- Entertainment

- <i>1917</i> Is a Movie About the Horrors of War, Told With a Devotion to Beauty and Life

1917 Is a Movie About the Horrors of War, Told With a Devotion to Beauty and Life

A good movie can be built from any number of components: a great story, distinctive visuals, a haunting score. But sometimes a face can take you 90 percent of the way. And although Sam Mendes’ extraordinary World War I drama 1917 is notable for the technical feat of its cinematography—Mendes and director of photography Roger Deakins have constructed it to be perceived as one unbroken shot—the true key to its effectiveness is the face of one of its central actors, George MacKay. MacKay plays a young British soldier, Schofield, who just happens to be nearby when one of his mates, Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman), accepts a dangerous assignment: The two must cross enemy lines to deliver a message to British troops on the other side by the next day’s dawn. Blake has a personal stake in the assignment: he has a brother among the troops at risk. Schofield doesn’t think the mission is such a good idea—but he sticks by his friend anyway.

The first thing that strikes you is how young these two are, barely out of boyhood. That’s true of nearly all war pictures, though those set in World War I—including this one—come with a particular, sorrowful sting. The First World War, one of the deadliest in modern history, came with no satisfying “The bad guy is dead!” ending. The losses were devastating for all countries involved, certainly for Great Britain. And if the imagery we associate with this war are bleak enough—the dank trenches, the dead horses, the ghostly barbed wire—the rows of grave markers in its aftermath, most of them guarding the remains of very young men, make for an especially somber end note.

Mendes captures all of that tense sadness in 1917 , yet the film—which he co-wrote with Krysty Wilson-Cairns, and which is dedicated to his grandfather, a veteran of the war—also has a glorious, pulsing energy. It’s largely about death, or the risk of death, but in addressing some of the horrors of this particular war, Mendes has made a film that feels wholly alive. It’s a carefully polished picture, not one that strives for gritty realism. But its inherent devotion to life and beauty is part of its power, in the same way that Lewis Milestone’s quietly wrenching 1930 All Quiet on the Western Front —a story not about the experience of English soldiers but of German ones, adapted from Erich Maria Remarque’s novel—stressed that individual moments of life, grasped and held tight, are the only real protection we have against the pointlessness of war.

1917 opens in a moment of repose: Blake and Schofield are lounging around a tree, reveling in the ultimate luxury of killing time, when they’re informed that they’re to report for a special assignment. (The general who gives them the order is a businesslike but clear-eyed Colin Firth—he looks from one lad to the other as if fully aware of the likelihood that neither will make it back.) Further afield, the Germans have allegedly retreated, and two English battalions, a total of some 1,600 men, have advanced and are ready to strike, hopeful that they can bring swift end to a war that has already been raging—and killing millions—for three years. But the retreat is a ruse. The Germans are now lying in wait for their prey. They have also, craftily, cut all lines of communication, so the message must travel in person, and it’s Blake and Schofield who must carry it.

Deakins’ camera follows this duo as they leap out of the bleak safety of the trenches and embark on a bone-rattling trek across no-man’s land. They pass dead horses ringed by haloes of flies, and the corpses of fellow soldiers, twisted and deformed in their shallow graves of mud. Schofield gallantly holds back a loop of barbed wire so that Blake might pass through; the thorns spring to life and pierce his hand. Shortly thereafter, he’ll lose his footing in a mud crater, instinctively breaking his fall with the wounded hand—it lands in the festering gut of a swollen corpse, a sick moment of slapstick. All of this is within the movie’s first 15 minutes or so, and you may be looking ahead to all the horrors that will surely follow, wondering if you’ll be able to bear them.

But Mendes knows what he’s doing. There are moments of horror and deep sorrow in 1917, including a scene of brutality followed by an aching loss—that this loss results from an act of compassion makes it even more cosmically cruel. This event occurs roughly a third of the way into the movie, and you feel its punch, hard. Yet Mendes’ aim isn’t to serve up relentless punishments for two hours. (The picture is just the right length for the story: You don’t need an epic runtime when your movie has an epic spirit.) Mendes moves his heroes through a field of chopped-down cherry trees, desolate in their lifeless beauty—though even then, there’s the promise that, after the stones have sunk into the ground, even more trees will pop up in their wake. There’s a deserted farmhouse whose environs are populated by one lonely cow. Someone—who?—has recently milked her, and Schofield, after testing to make sure it’s not poisoned, dips his hand in for a drink of the sublime. He’ll be shot at; he’ll have to silently kill a young German soldier with his bare hands. But Mendes is so careful with the story’s pacing that you never feel assaulted, even if you do feel the weight of every act.

And even if you fear the one-shot-effect might just be a gimmick, in Deakins’ capable hands, it works. The camera’s movement has its own silent dignity; there’s an overarching calmness to the film, even in its most intense moments. Deakins’ and Mendes’ sense of color may be even more wondrous than their one-shot feat: The ruins of a village lit by mortar explosions are bridal white. And if the colors of World War I are mostly brown, Deakins’ camera finds the stark beauty in its myriad hues, from dusky olives to soulful ochres.

The actors, moving through this world of terror with no glory, are terrific: Chapman’s baby face is sullen one moment, radiantly good-natured the next. Andrew Scott shows up for a few brilliant moments as a deadpan, disillusioned lieutenant. But it’s MacKay’s face that haunts you after the screen dims. It’s not a modern face, but a 1917 face, that of a young man who’s staunch in doing his duty but who has no idea what he’s gotten into. His ears stick out a little; he doesn’t smile much, but then, he can’t find much cause to. This is a face you might see inside an antique silver locket, the face of someone who’s loved very much, but who is very far away, and in danger. Through the space of the movie, we’re his guardians, keeping watch over him as well as we can. That he inspires this care in us is the key to the movie. He’s one of millions, but for the duration of 1917 , he’s our boy.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

‘1917’: Film Review

Actor George MacKay carries Sam Mendes' audacious real-time WWI adventure, which alternates between ground-level and God's-eye perspectives.

By Peter Debruge

Peter Debruge

Chief Film Critic

- ‘The Three Musketeers – Part II: Milady’ Review: Eva Green Surprises in French Blockbuster’s Less-Than-Faithful Finale 4 days ago

- ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’ Review: Henry Cavill Leads a Pack of Inglorious Rogues in Guy Ritchie’s Spirited WWII Coup 6 days ago

- ‘Challengers’ Review: Zendaya and Company Smash the Sports-Movie Mold in Luca Guadagnino’s Tennis Scorcher 1 week ago

How do you define heroism? For more than a century, movies have shaped our collective idea of the individuals and actions that qualify, often making the word appear out of reach to ordinary mortals. Now, along comes Sam Mendes ’ “ 1917 ” to smash those assumptions, revisiting a day in World War I when two ordinary British soldiers — Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman of “Game of Thrones”) and Schofield ( George MacKay ) — distinguish themselves by undertaking a mission for which neither is the slightest bit prepared.

Heroism reflects courage, of course. But that’s not the same as an absence of fear. There are scenes in “1917” when audiences will see Blake and Schofield panic-stricken, terrified and even in tears. Their errand calls for bravery, and yet, at times the pair can’t help but second-guess their decision to deliver a message that could save the lives of 1,600 fellow British soldiers. To do so, they must cross the battlefield in broad daylight, infiltrate booby-trapped German bunkers and confront the enemy face to face. One can hardly fault them for being afraid. If anything, the tension they feel makes the characters more relatable.

Heroism is about doing the right thing, but also about doing the thing that no one else wants to do. To a certain degree, it’s about luck, for many a heroic act has been thwarted by chance, leaving no one to acknowledge the sacrifice — although as “1917” demonstrates, glory plays no part in heroism. “Nothing like a patch of ribbons to cheer up a widow,” one officer cynically remarks. Drawing from war stories shared by his grandfather Alfred, who fought in the trenches, Mendes brilliantly re-creates the terrain — physical and emotional — navigated by its unlikely heroes, seen peacefully napping beneath a shady tree in the opening scene.

In the two hours ahead, Mendes will follow the pair into the realm of nightmares, depicting WWI as we’ve never seen it: simultaneously horrific and beautiful, immersive and detached, immediate and impossibly far removed from our own experience. These paradoxes define the unique sensibility of “1917,” which isn’t necessarily “better” than such iconic WWI films as “War Horse” and “All Quiet on the Western Front,” but different. Mendes has found an original approach to a familiar subject, refreshing events from a century ago in a way that looks, sounds and feels absolutely cutting-edge.

To maintain a sense of anticipation, the studio shared little about “1917” in advance, apart from the fact that Mendes had designed the entire movie to play out in a single shot — a “plan-séquence,” as the French call it, or “oner” among film students and cinephiles — à la Iñárritu’s “Birdman” and Hitchcock’s “Rope.” Such an audacious choice can often feel like a stunt, drawing audiences’ attention to the technique over the substance, which is intermittently the case here. The way Mendes collaborates with DP Roger Deakins , it’s as if someone pressed pause on the war and allowed two low-level infantrymen to poke around the spaces where it all went down — an almost-virtual-reality version of events, conveyed through the continuous-take (but not quite first-person-shooter) aesthetic of video games. All that’s missing is the ability to choose for oneself where to point the camera, though such decisions are better left to Deakins.

The day is April 6, 1917. German forces have retreated from the position they were holding in northern France, although they’re not “on the ropes” or nearly ready to surrender, as some of their British rivals mistakenly believe. The Fritzes have fallen back to meet up with reinforcements, hoping to lure the Allies into a trap, and two British battalions are about to fall for it, ready to send their men to certain death the following morning. With communication channels cut and no way of contacting those outfits, the British commanding general (Colin Firth, one of several stars cast as officers, each appearing only briefly, à la George Clooney and John Travolta in Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line”) sends two lance corporals, Blake and Schofield, across the French countryside to deliver the warning and call off the attack.

Given the importance of the message, it seems odd that two unproven foot soldiers should be chosen for the task, although Blake has a personal stake in seeing the mission through: His older sibling is among the first wave of troops to be dispatched in the morning. When we meet him in the film’s final minutes, the elder Blake comes across as the more conventional hero: tall, handsome, covered in blood and mud and the scars of battle. By comparison, his kid brother looks soft and altogether too young to be enlisted, as does best friend Schofield. In MacKay’s case, that’s a reflection of his performance — his character seems aptly intimidated by the mission.

Thomas Newman’s score ticks nervously through the first act, which takes place in the trenches, as the camera pushes behind Blake and Schofield through crowds of soldiers — alternating between following over their shoulders and hustling backward so we can study their faces — to track these two foolhardy volunteers to the front line. At times, the camera can make us feel like a third character along for the ride, and we the audience share in their anxiety. Seventeen minutes in, they hoist themselves up to the surface, and we hold our breath as the camera lifts alongside them, taking in the surreal wasteland so few of their comrades live to see, with its half-decayed horse corpses and monstrous rats.

As if the aboveground trek weren’t daunting enough — a Homeric micro-odyssey that unfolds in real time against awesome outdoor sets — it gets more intimidating still when they reach the newly vacated German trench. No matter how much we know about WWI going in, Mendes and Deakins’ visual design meticulously withholds and reveals vital information about the surroundings, such that stepping into darkened spaces requires nearly as much nerve from us as it does the characters. At times, the camera lags a split-second behind, subliminally agonizing as we sense Blake and Schofield suddenly exposed to something beyond our vision. At others, we see what’s coming before they do, as when a distant aerial dogfight ends with one of the biplanes crashing almost directly into the camera.

During moments like these, it’s easy to forget the single-shot gimmick, although the conceit comes at a price: Traditional editing allows filmmakers to tighten and manipulate time for dramatic effect, whereas here, Mendes and editor Lee Smith (whose job involves hiding the splices) must commit to the pace that was captured on set. “1917” drags in places, and though a bit of quiet introspection is welcome in a war movie, Mendes and co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns fill these with forgettable stories: A scene involving a cherry orchard chopped down by the Germans during their retreat serves as a good example, pairing the surreal imagery with banal observations about the different varieties of cherry trees.

The script feels most exciting when other characters are involved, especially after a shocking off-camera setback threatens the mission. Things pick up about midway through when we cross a group of soldiers led by Mark Strong, who take us as far as the bombed-out French village of Écoust, where a scuffle with a German sniper knocks Schofield unconscious. It’s here that the film’s only discernible cut occurs, during a long subjective blackout that drastically shortens the amount of time left to finish his mission. Later that night, as we stumble out into a vision of hell, and Newman’s score swells to full orchestra as flares illuminate the godforsaken ruins.

(Note: the next paragraph contains spoilers.) There’s still quite a distance to travel to reach the battalions at Croisilles Wood, where Schofield arrives as the raid is underway — which explains the iconic sight, so central to the film’s marketing, of MacKay running perpendicular to a swarm of charging soldiers as bombs erupt around him. That shot (or “segment,” in light of the film’s long-take aesthetic) is outrageous and exhilarating, an act of last-minute desperation by a character who’s proved far more sensible about his own safety until now. It also serves as a metaphor for the entire mission, whose heroic dimension has been revealed gradually over time: While the British forces’ attention were focused elsewhere, Blake and Schofield set out in an entirely different direction, exposing themselves to danger.

Perhaps its Mendes’ theatrical side that can’t resist the temptation to bring “1917” full circle, back to a viewpoint that rhymes, ironically, with the film’s opening frame. That intellectually driven choice underscores what a different filmmaker he is from Spielberg or Nolan, with Mendes looking to imprint some kind of poetic sensibility on the technical accomplishment we’ve just witnessed. Astonishing as the filmmaking can be at times, it’s Mendes’ attention to character, more than the technique, that makes “1917” one of 2019’s most impressive cinematic achievements.

Reviewed at Arclight Cinemas, Hollywood, Nov. 21, 2019. MPAA Rating: R. Running time: 119 MIN.

- Production: A Universal Pictures release of a DreamWorks Pictures, Reliance Entertainment presentation, in association with New Republic Pictures, of a Neal Street Prods., Amblin Partners production. Producers: Sam Mendes, Pippa Harris, Jayne-Ann Tenggren, Callum McDougall, Brian Oliver.

- Crew: Director: Sam Mendes. Screenplay: Sam Mendes, Krysty Wilson-Cairns. Camera (color, widescreen): Roger Deakins. Editor: Lee Smith: Music: Thomas Newman.

- With: George MacKay, Dean-Charles Chapman, Mark Strong , Andrew Scott, Richard Madden, Claire Duburcq, Colin Firth, Benedict Cumberbatch. (English, French, German dialogue)

More From Our Brands

Céline dion on living with stiff person syndrome: ‘nothing’s going to stop me’, mg just unveiled an ultra-aerodynamic hypercar that can hit 60 mph in under 2 seconds, alexis ohanian’s 776 foundation invests in women’s sports bar, be tough on dirt but gentle on your body with the best soaps for sensitive skin, kristian alfonso confirms days of our lives return for bill hayes tribute — but how long will hope stay in salem, verify it's you, please log in.

- Universal Pictures

Summary At the height of the First World War, two young British soldiers, Schofield (George MacKay) and Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) are given a seemingly impossible mission. In a race against time, they must cross enemy territory and deliver a message that will stop a deadly attack on hundreds of soldiers—Blake’s own brother among them.

Directed By : Sam Mendes

Written By : Krysty Wilson-Cairns, Sam Mendes

Where to Watch

Dean-Charles Chapman

Lance corporal blake.

George MacKay

Lance corporal schofield.

Daniel Mays

Sergeant sanders.

Colin Firth

General erinmore.

Lieutenant Gordon

Andy apollo, sergeant miller, josef davies, private stokes, billy postlethwaite, gabriel akuwudike, private buchanan.

Andrew Scott

Lieutenant leslie, spike leighton, private kilgour, robert maaser, german pilot, gerran howell, private parry, adam hugill, private atkins.

Mark Strong

Captain smith, richard mccabe, colonel collins, benjamin adams, sergeant harrop, private cooke, kenny fullwood, private rossi, critic reviews.

- All Reviews

- Positive Reviews

- Mixed Reviews

- Negative Reviews

User Reviews

Related movies.

Seven Samurai

The Wild Bunch

North by Northwest

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

The French Connection

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Mad Max: Fury Road

The Incredibles

Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope

House of Flying Daggers

Assault on Precinct 13

The Hidden Fortress

Gangs of Wasseypur

Captain Blood

Related news.

2024 Movie Release Calendar

Jason dietz.

Find release dates for every movie coming to theaters, VOD, and streaming throughout 2024 and beyond, updated weekly.

Every Zack Snyder Movie, Ranked

With the arrival of Zack Snyder's latest Rebel Moon chapter on Netflix, we rank every one of the director's films—from bad to, well, less bad—by Metascore.

Every Guy Ritchie Movie, Ranked

We rank every one of the British director's movies by Metascore, from his debut Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels to his brand new film, The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.

April Movie Preview (2024)

Keith kimbell.

The month ahead will bring new films from Alex Garland, Luca Guadagnino, Dev Patel, and more. To help you plan your moviegoing options, our editors have selected the most notable films releasing in April 2024, listed in alphabetical order.

DVD/Blu-ray Releases: New & Upcoming

Find a list of new movie and TV releases on DVD and Blu-ray (updated weekly) as well as a calendar of upcoming releases on home video.

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

Common sense media reviewers.

Unique WWI epic has brutal war violence, smoking.

A Lot or a Little?

What you will—and won't—find in this movie.

War is hell. Camaraderie and loyalty can help moti

Blake and Schofield demonstrate incredible courage

Horrors of war are on full display from a first-pe

Masturbation joke.

Strong language throughout, including "bastards,"

One character drinks from flask. Smoking.

Parents need to know that 1917 is an outstanding World War I drama that makes viewers feel like they're experiencing what it might really have been like to be in the trenches on the front lines. Director Sam Mendes wrote the screenplay based on the stories his grandfather told him about being a runner in the…

Positive Messages

War is hell. Camaraderie and loyalty can help motivate people in dire circumstances. You can make headway in the worst situation if you persevere and focus on your goal. Themes include compassion and courage.

Positive Role Models

Blake and Schofield demonstrate incredible courage for the greater good, as well as compassion for others -- including the enemy. Schofield perseveres on his mission, even after being given the opportunity to seek a safer situation.

Violence & Scariness

Horrors of war are on full display from a first-person viewpoint, including being shot at, feeling the fear of the enemy nearby, getting bombed. Climbing over human carcasses, walking past dead animals. A couple of instances of men killing enemies face to face. Many bloody, gory injuries, including missing limbs, men writhing in pain. A soldier unintentionally puts his wounded hand in the open guts of a dead horse when he lands in a bomb crater. Characters are visibly in substantial peril throughout; tons of tension.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

Sex, Romance & Nudity

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Sex, Romance & Nudity in your kid's entertainment guide.

Strong language throughout, including "bastards," "piss off," "s--t," several uses of "f--k."

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Drinking, Drugs & Smoking

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Drinking, Drugs & Smoking in your kid's entertainment guide.

Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that 1917 is an outstanding World War I drama that makes viewers feel like they're experiencing what it might really have been like to be in the trenches on the front lines. Director Sam Mendes wrote the screenplay based on the stories his grandfather told him about being a runner in the British Army. The camera follows the young soldiers in one long tracking shot, making it feel like you're right in the action. Consequently, it all feels very real, and tension runs extremely high. Battle violence is graphically realistic, including shootings, strangling, stabbing, bombings, etc. Wounded soldiers are bloody, missing limbs, and crying in pain. Soldiers smoke (accurate for the era), drink, and use strong language ("f--k," "s--t"). Benedict Cumberbatch and Colin Firth make cameo appearances alongside stars George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman . To stay in the loop on more movies like this, you can sign up for weekly Family Movie Night emails .

Where to Watch

Videos and photos.

Community Reviews

- Parents say (46)

- Kids say (130)

Based on 46 parent reviews

Great movie!

What's the story.

During World War I, it's 1917, and British soldiers Schofield ( George MacKay ) and Blake ( Dean-Charles Chapman ) are selected to deliver an urgent message to a nearby battalion. In their high-stakes effort to save 1,600 lives, the runners must themselves survive the journey through enemy territory.

Is It Any Good?

About 15 minutes in to this movie, it dawns on you that this is something uniquely brilliant; by the end, it's clear that Sam Mendes has made one of the best films of 2019. That's largely because of the innovative cinematography: The entire film is one long tracking shot. Of course, there are edits, as imperceptible to viewers as they might be. And, honestly, whether or when the film stopped rolling isn't the point -- it's the effect. As the camera follows the two British runners trying to get across a German-occupied battlefield to deliver their urgent message, it moves around them -- in front, behind, next to, sometimes around a rock or a slightly different route but keeping the soldiers in view. It creates the video game-like feeling that you're the third runner on the mission. The first-person viewpoint transforms the experience of watching 1917 into something intimate, just short of interactive. Cinematographers aren't often household names, but Roger Deakins might just become one thanks to this Herculean accomplishment.

Given that the film is essentially a one-direction journey in which the camera rarely stops rolling, the production design is a real feat. Smoke and mirrors can't possibly exist: We follow Blake and Schofield through a looooooong trench, a maze of a barracks, and French countryside that's ravaged from the wages of war. The actors are all superb, but MacKay will rip your heart out as a low-ranking officer who's resentful of his assignment but rises to see his mission through, no matter the potential sacrifice. Teens may be reluctant to see a movie about World War I, but 1917 could be a game changer: It's hard to imagine anyone won't appreciate its originality, heart, and grit.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about World War I. How was it different from other wars? How have you seen it depicted in the media before? How does 1917 's portrayal of it compare?

Did you find the movie's violence realistic? How does the impact of this kind of violence compare to what you might see in a horror or superhero movie? Why do you think the filmmakers chose to show the violence in this way?

Why do you think the filmmakers chose their unusual camera technique? How did it change your experience as a viewer? Do you think it was effective?

How do the characters demonstrate compassion ? In the heat of war, is compassion a luxury, or a necessity? How do you think Blake should have interacted with the pilot?

Talk about examples of teamwork in the film. Why is it important in the film, and why is it an important skill in real life?

Movie Details

- In theaters : December 25, 2019

- On DVD or streaming : March 24, 2020

- Cast : George MacKay , Dean-Charles Chapman , Benedict Cumberbatch

- Director : Sam Mendes

- Studio : Universal Pictures

- Genre : Action/Adventure

- Topics : Great Boy Role Models , History

- Character Strengths : Compassion , Courage , Perseverance

- Run time : 110 minutes

- MPAA rating : R

- MPAA explanation : violence, some disturbing images, and language

- Awards : BAFTA , Golden Globe

- Last updated : March 30, 2024

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

Our editors recommend.

They Shall Not Grow Old

Saving Private Ryan

Band of Brothers

Journey's End

A Very Long Engagement

Testament of Youth

Best history documentaries, world war i books for kids, related topics.

- Perseverance

- Great Boy Role Models

Want suggestions based on your streaming services? Get personalized recommendations

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

1917 review – Sam Mendes’s unblinking vision of the hell of war

Mendes’s first world war drama, filmed to appear as one continuous take, plunges the viewer into the trenches alongside two young British soldiers to breathless effect

F or the opening of his 2015 Bond movie Spectre , director Sam Mendes (who won an Oscar for his first feature, American Beauty ) mounted a memorable sequence set amid Mexico City’s day of the dead festival. In what appears to be a single continuous shot, the camera tracks a masked figure through crowded streets, into a hotel lobby, up an elevator, out of a window, and over the rooftops to a deadly assignation. It’s an audacious, attention-grabbing curtain-raiser widely hailed as the film’s strongest asset.

For his latest movie – an awards-garlanded first world war drama that has already won best picture honours at the Golden Globes – Mendes has returned to the lure of the “one-shot” format, this time stretching it out to feature length. Like Hitchcock’s Rope or Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman , 1917 uses several takes and set-ups, seamlessly conjoined to give the appearance of a continuous cinematic POV, albeit with periodic ellipses. The result is a populist, immersive drama that leads the viewer through the trenches and battlefields of northern France, as two young British soldiers attempt to make their way through enemy lines on 6 April 1917.

George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman are perfectly cast as Schofield and Blake, the lance corporals enlisted to venture into enemy territory with a message for fellow troops poised to launch a potentially catastrophic assault. The Germans have made a “strategic withdrawal”, suggesting that they are on the run. In fact they’re lying in wait, armed and ready to repel the planned British push. Together, these young soldiers must reach their comrades and halt the attack – a race against time and insurmountable odds.

With meticulous attention to detail (plaudits to production designer Dennis Gassner) and astonishingly fluid cinematography by Roger Deakins that shifts from ground level to God’s-eye view, Mendes puts his audience right there in the middle of the unfolding chaos. There’s a real sense of epic scale as the action moves breathlessly from one hellish environment to the next, effectively capturing our reluctant heroes’ sense of anxiety and discovery as they stumble into each new unchartered terrain. This is nail-biting stuff, interspersed with genuine shocks and surprises. Whether it’s a tripwire moment that provokes an audible gasp, a distant dogfight segueing into up-close-and-personal horror, or a single gunshot that made me jump out of my seat during an otherwise near-silent sequence, there’s no doubting the film’s theatrical impact.

Yet for all the steel-trap visceral efficiency, it’s the more low-key moments that really pack a punch – those moments when we’re confronted with the simple human cost of war. As with Peter Jackson’s monumentally moving documentary They Shall Not Grow Old , 1917 works best when showing us the boyish face of this conflict; the pitiable plight of a young generation, old or lost before their time. It’s a quality perfectly captured by MacKay’s endlessly watchable eyes, which manage simultaneously to project ravaged innocence and world-weary exhaustion – fatalism and hope.

“Hope is a dangerous thing,” says Benedict Cumberbatch’s Colonel MacKenzie, just one of a number of small roles filled by high-profile actors happy to play second fiddle. It’s a line that mirrors the central refrain from The Shawshank Redemption , another humanist movie tinged with horror that seems to haunt Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns’ script. There are evocations, too, of Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan , not only in the unflinching depiction of battlefield violence, but also in a plot device that sets soldiers searching for a brother in a desperate quest for redemption. In one of its more surreal (or perhaps transcendent) sequences, wherein a purgatorial night-time underworld is illuminated in a yellow phosphorescent haze, I was unexpectedly reminded of a dream scene from Waltz With Bashir , in which young men rise from the water, like ghosts walking among the living.

Throughout this Homeric odyssey, Thomas Newman’s pulsing score ratchets up the tension, travelling “up the down trench”, through the body-strewn carnage of no man’s land (a forest of wood and wire, bone and blood) and into the eerie environs of deserted farmhouses and bombed-out churches. Occasionally, we hear echoes of the rising crescendo of Hans Zimmer’s Dunkirk score; elsewhere, Newman’s cues are full of piercing melancholia mingled with distant threat.

In a film in which music plays such a crucial role, it’s significant that perhaps the most powerful scene is an interlude of song. Emerging from a river after a baptismal episode of death and rebirth, we find ourselves in a wood where a young man sings The Wayfaring Stranger. It’s an interlude that brings the characters and audiences together in silence, communally experiencing that still-small voice of calm that lies at the heart of so many great war movies.

- Mark Kermode's film of the week

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

‘1917’ Review: War Is Hell, One Shot at a Time

By Peter Travers

Peter Travers

In the first shot of this groundbreaking World War I film, two young British soldiers — lance corporals Schofield (George MacKay) and Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) — are caught napping in a field. It’s the last time they, or we in the audience, will be able to catch a breath. For the next two hours, director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins will stalk these young men in what seems like one continuous take, tagging along as they charge through enemy territory on a mission to save lives. Their orders from General Erinmore (Colin Firth) are crystal clear: They must make their way across booby-trapped, corpse-strewn terrain in France to hand-deliver a message to Col. Mackenzie ( Benedict Cumberbatch ), commander of the Second Battalion. It contains orders to call off a planned advance against the German army, falsely assumed to be on the ropes. Turns out it’s a trap that could result in the slaughter of more than 1,600 British soldiers, including Blake’s brother ( Bodyguard star Richard Madden). With communications down, the only hope rests with two boys who can barely shave.

And they’re off, over two days in April 1917, choking on tension that never lets up. Mendes, who won an Oscar for his 1999 debut film, American Beauty, and has been performing award-winning wonders on stage with The Ferryman and The Lehman Trilogy, is testing himself. About that single take — it’s impossible, of course. Filmmakers from Alejandro G. Iñárritu in Birdman and Alexander Sokurov in Russian Ark have also faked it before. But Mendes, in ardent and artful tandem with editor Lee Smith ( Dunkirk ) and Deakins, his creative partner on Skyfall, Revolutionary Road and Jarhead, creates a visionary miracle. Any fears you might have going in that technical trickery is usually short for “gimmick” are instantly allayed by the film’s palpable sense of intimacy.

For the screenplay that Mendes wrote with Krysty Wilson-Cairns ( Penny Dreadful ), he didn’t consult the history books so much as the stories told to him by his grandfather, Alfred Mendes, a messenger on the Belgian front to whom 1917 is dedicated. You can see the influence of other films about the period, notably Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory and Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old, a documentary that restored actual WWI footage to startling life. But Mendes follows his own muse in juxtaposing terror with surprising tenderness, as when a German biplane plummets from the sky and Blake and Schofield try to rescue the enemy pilot. Images of war vie with such moments as Schofield’s encounter with a woman and an orphan baby in the bombed-out village of Écoust, where a skirmish with a German sniper knocks Schofield out cold, creating a brief break in the film’s real-time momentum.

Editor’s picks

The 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, the 50 worst decisions in movie history, every awful thing trump has promised to do in a second term.

Still, the director makes sure the actors aren’t upstaged by the pyrotechnics. Mark Strong ( Kingsman ) and Andrew Scott (the hot priest on Fleabag ) register strongly as British officers encountered along the way. But the real soul of 1917 can be found in it two lead actors. Chapman (Tommen Baratheon on Game of Thrones ) displays the fighting spirit of youth as Blake blunders into heroism. And MacKay (the eldest son of Viggo Mortensen in Captain Fantastic ) nails every nuance in an astounding performance. Whether running past soldiers storming the battlefield or getting stopped in his tracks by a voice singing the haunting “Wayfaring Stranger,” Schofield stays determined to complete his mission. And the burning intensity of MacKay’s face, reflecting the ferocity and futility of war, leaves an indelible mark. His fervor, coupled with the creative passion that Mendes infuses in every frame, makes 1917 impossible to shake.

Dakota Fanning's Talking Bird Is Trying to Warn Her in New Trailer for 'The Watchers'

- Tweet Tweet

- By Jon Blistein

'Power' Documentary Trailer Traces the History of Policing in the U.S.

- People vs The Police

- By Kalia Richardson

'Deadpool & Wolverine' Trailer: What Could Go Wrong With These Two Together?

- Claw & Order

- By Kory Grow

10 Very Important Things I Learned From Watching 'Rebel Moon: Part 2 — The Scargiver'

- MOVIE REVIEW

- By David Fear

'Sesame Street' Writers Avoid Strike With Last-Minute Agreement

- Sesame Strike

- By Kalia Richardson and Ethan Millman

Most Popular

The rise and fall of gerry turner's stint as abc's first 'golden bachelor', which new taylor swift songs are about matty healy, joe alwyn or travis kelce breaking down 'tortured poets department' lyric clues, prince william’s bond with his in-laws sheds a light on his 'chilly' relationship with these royals, college football ‘super league’ pitch deck details breakaway plan, you might also like, andrew jarecki addresses lingering ethical concerns about ‘the jinx’ and explains why he wanted to revisit robert durst’s crimes, louis vuitton’s voyager show livestream breaks xiaohongshu record, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, ‘dune,’ ‘rebel moon,’ and sydney sweeney made home viewing success a package deal, alexis ohanian’s 776 foundation invests in women’s sports bar.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Verify it's you

Please log in.

Breaking News

Review: Sam Mendes’ World War I drama ‘1917’ is a technical triumph — and a half-successful experiment

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Sometime after nightfall in “1917,” a gravely virtuosic dispatch from the front lines of World War I, a British soldier, Lance Cpl. Schofield (George MacKay), makes his way through a darkened building amid the ruins of a bombed-out French village. There, in a shadowy room illuminated by overhead flares and rattled by distant explosions, he stumbles on a frightened young woman (Claire Duburcq) in hiding.

They communicate in gestures and whispers. She sees that he’s wounded and tenderly touches his bloodied head; he winces in pain but gratefully accepts. There’s a surreal, even ghostly feel to this encounter, a fleeting moment of consolation in a place suffused with death. For the audience, it’s a delicate interlude in a dark, violent story; for Schofield, it offers respite but no escape from a hell on earth that has raged for three years and shows little sign of abating.

The movie’s simple title and taut time frame — it unfolds over two consecutive days in April 1917 — serve as a grim reminder to the audience that the war will rage on for more than a year. But for the most part, English director Sam Mendes (who wrote the script with Krysty Wilson-Cairns) avoids granting us any knowledge not already possessed by his characters. His aim is to convey, with immersive realism and real-time immediacy, the experience of two men on an overnight mission — one that may look small in the war’s grander context but, like many such missions, serves a crucial purpose.

Inspired by stories that Mendes heard from his grandfather, Alfred Mendes, a veteran of the war’s Belgian front, “1917” follows Schofield and Lance Cpl. Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman), young men stationed in northern France. Blake is the louder and livelier of the two, a raconteur with a poetic streak who rhapsodizes longingly about his family’s cherry orchard. Schofield is quieter, more withdrawn and disillusioned. The traumas of the Battle of the Somme are still fresh, leaving him with awful memories and a medal he neither wears nor talks about.

Further horrors and tests of bravery await. The ticktock-thriller plot is set in motion by a general (Colin Firth) who instructs Schofield and Blake to travel on foot over miles of bloodied, bombed-out terrain to deliver a warning to the Second Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, which is planning an imminent attack on fleeing German forces. But what appears to be an enemy retreat is actually a brilliant tactical calculation; the battalion’s 1,600 troops, who include Blake’s brother, are walking into a skillfully orchestrated trap.

And a skillfully orchestrated trap seems as fitting a way as any to think of “1917,” in which the rawness and brutality of the Great War have been largely tamed into aesthetic submission. The movie is a powerfully incongruous hybrid: a soldier’s lament and a formalist’s delight. Reuniting with the great cinematographer Roger Deakins, his collaborator on “Skyfall,” “Revolutionary Road” and “Jarhead,” Mendes has constructed “1917” so as to simulate the appearance of one unbroken take — a long, sinuous tracking shot sustained without any visible cuts. (The clever peekaboo editing is by Lee Smith, who also cut Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk,” a war epic as fragmented as this one is seamless.)

The result is a two-hour tightrope walk that keeps us intently focused on these men and their mission, never allowing us to look away even when we’d like to. By the time Blake and Schofield receive their marching orders, the camera has already followed them through several hundred yards’ worth of trenches. Mendes fills the widescreen frame with deft pointillist flourishes; he’s fond of pulling back and letting the background come into focus, giving us just enough time to register the sight of other soldiers — working, playing and bickering in their filthy uniforms and steel helmets — before whisking us on to the next episode.

The camera will remain alongside Blake and Schofield as they venture out of the ditches and across a no man’s land etched with craters and barbed wire. (The scorched-earth production design is by Dennis Gassner.) Inch by grisly inch, they make their way through a gnarled labyrinth of deserted fortifications and sun-bleached human skeletons lying embedded and forgotten in the craggy terrain, all bearing silent witness to a war seemingly without end.

In these moments, “1917” casts aside the chaotic grammar of the combat picture and takes on the hushed eloquence of a post-apocalyptic horror movie. Rarely have two men seemed so utterly alone: Here there are only the remnants of battle, a few skittering rats and the stench of mass death. The overall effect of Mendes’ blocking and camerawork, staggeringly complicated though it must have been to pull off, is disarmingly spare and simple. His technique weaves an undeniable spell, sometimes deepened and sometimes broken by a Thomas Newman score that veers from low, ominous drones to majestic orchestral surges.

Mendes is good at building tension within the frame, even as his gently drifting, weightless camera conveys the oddly pleasurable feeling of a guided tour. He has a talent for luring his protagonists, and the audience, into an eerie calm, only to jolt us with a showman’s sense of cunning. There are at least two moments when the movie brutally ambushes its characters — once with a circling fighter plane that winks at “North by Northwest,” and later with a devastatingly swift attack that takes place, perversely, when the camera isn’t looking.

I realize that nearly everything I have written has characterized “1917” in terms of its visual choreography, which undersells the actors — MacKay and Chapman are both heartrendingly good — but also speaks to the limitations of Mendes’ formal conceit. He is one of many filmmakers, from Max Ophüls and Andrei Tarkovsky to Alfonso Cuarón, who have embraced the tracking shot, in which time itself is given weight and physicality by the unified movement of the camera. A few movies have stretched the technique to feature-length, like Alexander Sokurov’s “Russian Ark” (2002) and Sebastian Schipper’s “Victoria” (2015), both notably executed the hard way, with no postproduction trickery.

By contrast, movies like Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s “Birdman” and now “1917” create their visual continuity using techniques that would have been unimaginable in the predigital era. One of the distractions of Mendes’ movie is that you may spend a lot of time looking for those hidden edits, those moments when the camera effectively “blinks.” (It’s like a higher-tech version of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 one-take wonder, “Rope.”) It’s a fun game, but it also gets at the paradox of so much extended long-take cinema: A device meant to be seamless and immersive can’t help but keep drawing your attention to its own impeccable craftsmanship.

Perhaps it’s because Schofield and Blake are making their way through Gallic terrain, but “1917” at times brought to mind the words of two French-born filmmakers who were themselves once fellow travelers. “There’s no such thing as an antiwar film” is a quote often attributed to François Truffaut, and it was Jean-Luc Godard who said, “Film is truth 24 times per second, and every cut is a lie.”

Intentionally or not, “1917” feels like an attempted rejoinder to both those famous declarations. Genuinely uninterested in glorifying the spectacle of war, Mendes deploys technological trickery in pursuit of a new kind of cinematic truth.

I think he half succeeds. There are times when the nonstop visual momentum lends “1917” the feel of a virtual-reality installation, and others when the simulation of raw immediacy slips to reveal the calculated construct underneath. Mendes’ films have had a weakness for overly pristine surfaces — in evidence since his Oscar-winning debut feature, “American Beauty” — and his coolly detached, slightly bloodless aestheticism makes for an odd but fascinating fit with the war movie, a genre that often encourages filmmakers to unleash a full-blown sensory assault.

“1917,” by contrast, keeps its composure, giving you the distance to process its assiduously doled-out horrors; it only occasionally achieves gut-level impact, but it also doesn’t try to bludgeon you in submission. If Mendes has not made an antiwar movie in the unattainable Truffautian sense, he has nonetheless rendered a thoughtful, clear-eyed argument for the futility and endlessness of armed conflict, a message that reverberates well beyond these particular front lines into the present.

At one point, a wise captain (Mark Strong) tells Schofield that even if he makes it to his destination, his attempt to call off the attack may be in vain: “Some men just want the fight.” He is one of several peripheral characters — played by actors including Firth, Andrew Scott, Benedict Cumberbatch and an especially good Richard Madden — who show up to offer a few often-cynical words of counsel before sending them on their way.

Their famous faces may pull you briefly out of the movie, but seeing each one is pleasurable all the same — and instructive. Taken together, they suggest that “1917” might be best approached not as a work of strict realism but as a knowing hybrid of authenticity and artifice. It’s worth recalling that Mendes is a longtime theater director, which may explain some of the movie’s more brazenly operatic gestures: In one stunning nighttime scene, Deakins’ camera rises over those fire-lit ruins, transforming a disaster zone into a stage as Newman’s score rises in a mighty crescendo. It may be a grandiose flourish, but you can’t deny it makes for a startlingly literal theater of war.

Rating: R, for violence, some disturbing images and language Running time: 2 hours Playing: Opens Dec. 25 in general release

More to Read

How accurate is a new movie about the real-life spies who inspired Bond? We checked

April 19, 2024

Review: Long before Bond, ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’ kicked off British covert ops

April 18, 2024

Inside the most unnerving scene in ‘Civil War’: ‘It was a stunning bit of good luck’

April 12, 2024

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Justin Chang was a film critic for the Los Angeles Times from 2016 to 2024. He is the author of the book “FilmCraft: Editing” and serves as chair of the National Society of Film Critics and secretary of the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Entertainment & Arts

Sydney Sweeney claps back at critics (again), this time in new Hawaiian vacation pictures

Ryan Reynolds and Hugh Jackman battle it out before joining forces in ‘Deadpool and Wolverine’ trailer

April 22, 2024

David Mamet slams Hollywood’s ‘garbage’ DEI initiatives. ‘It’s fascist totalitarianism’

April 21, 2024

Company Town

Documentary filmmaker and social activist Lourdes Portillo dies at 80

1917 (2019)

- User Reviews

Awards | FAQ | User Ratings | External Reviews | Metacritic Reviews

- User Ratings

- External Reviews

- Metacritic Reviews

- Full Cast and Crew

- Release Dates

- Official Sites

- Company Credits

- Filming & Production

- Technical Specs

- Plot Summary

- Plot Keywords

- Parents Guide

Did You Know?

- Crazy Credits

- Alternate Versions

- Connections

- Soundtracks

Photo & Video

- Photo Gallery

- Trailers and Videos

Related Items

- External Sites

Related lists from IMDb users

Recently Viewed

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

The War Film 1917 Is One of the Year’s Mightiest Technical Achievements

By Richard Lawson

Director Sam Mendes’s last war film was the 2005 mood piece Jarhead , about American troops during Desert Storm going a bit mad as they wait, and wait, and wait to see combat. No such empty tedium is enjoyed by the war boys of 1917 (out December 25), Mendes’s relentless WWI film about a frantic two-man mission to avert a strategic disaster.

Based partly on stories Mendes was told by his war vet grandfather, 1917 is the first time Mendes has a writing credit on one of his films, sharing billing with Krysty Wilson-Cairns, a screenwriter and history buff who worked with Mendes to shape his nascent ambition into what it is now. While there are moments of poignant writerly grace to be found in 1917 , the main attraction—if you can call it that—is the film’s suspense-filled race through the hell of war. It’s a dazzling technical achievement, offering much of Mendes’s typical aesthetic splendor, but reined in perhaps just before the horror is drowned in too much lushness.

It’s April 1917 in the flatlands of France, and two young British soldiers— Dean-Charles Chapman’s Blake and George MacKay’s Schofield—are roused from a rare and uneasy rest in a flower-dotted meadow. They awake to an urgent mandate: an attack planned by another battalion, camped somewhere across enemy-occupied territory, is set to fall into a German trap. It’s up to Blake and Schofield, then, to deliver the vital order to halt the charge. To do so, they must scramble through an expanse of mud and ruin, running against the clock, unsure where enemies might lie.

There’s a bit of Saving Private Ryan ’s DNA in 1917 , the way it similarly employs a single-motive pursuit as a means to explore various facets of a roiling vastness. But Mendes has given his film tighter constraints than the sweep of Steven Spielberg ’s World War II film. He stages 1917 in two sections that are made to look like a pair of long, unbroken shots unfolding in real-time. Of course, 1917 wasn’t actually filmed without cuts, much as the same-styled Birdman wasn’t actually one continuous scene. Mendes and his editor Lee Smith stitch things together rather seamlessly, though, the camera smoothly tracking along—in the narrow canyons of trenches, through fetid water, into bombed-out homes—as the two young men make their way, inch by agonizing inch, toward their goal.

It’s a staggering piece of filmmaking, admirable both for its complexity and its control. 1917 is a harrowing survival-adventure film, and yet Mendes doesn’t make super-humans of his two main characters. They are often almost impossibly lucky, yes, but there are no action-movie heroics to be found in the film. Which makes the whole thing that much more gripping; we can imagine almost any scared soul doing all this desperate maneuvering.