- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Real Story Behind the ‘Migrant Mother’ in the Great Depression-Era Photo

By: Sarah Pruitt

Published: May 8, 2020

It’s one of the most iconic photos in American history. A woman in ragged clothing holds a baby as two more children huddle close, hiding their faces behind her shoulders. The mother squints into the distance, one hand lifted to her mouth and anxiety etched deep in the lines on her face.

From the moment it first appeared in the pages of a San Francisco newspaper in March 1936, the image known as “Migrant Mother” came to symbolize the hunger, poverty and hopelessness endured by so many Americans during the Great Depression . The photographer Dorothea Lange had taken the shot, along with a series of others, days earlier in a camp of migrant farm workers in Nipomo, California.

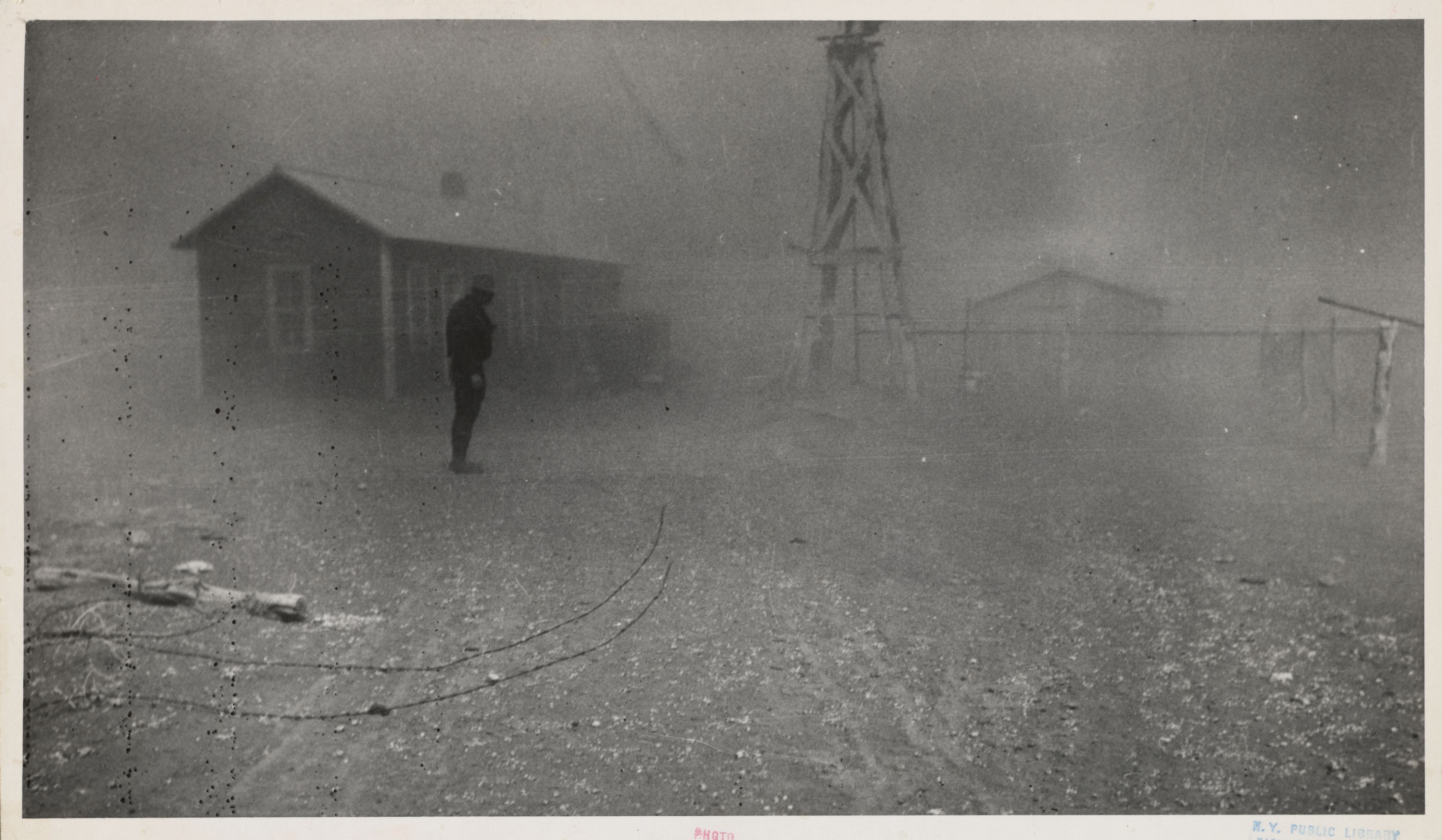

Lange was working for the federal government’s Resettlement Administration—later the Farm Security Administration (FSA)—the New Deal -era agency created to help struggling farm workers. She and other FSA photographers would take nearly 80,000 photographs for the organization between 1935 to 1944, helping wake up many Americans to the desperate plight of thousands of people displaced from the drought-ravaged region known as the Dust Bowl .

How the Photo Was Taken

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange told Popular Photography magazine in 1960 . She had spotted a sign for the migrant workers’ campsite driving north on Highway 101 through San Luis Obispo County, some 175 miles north of Los Angeles. Bad weather had destroyed the local pea crop, and the pickers were out of work, many of them on the brink of starvation.

Lange didn’t ask the woman’s name, or find out her history. She claimed the woman told her she was 32, that she and her children were living on frozen vegetables and birds the children had killed, and that she had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.

Soon after the photos were published in the San Francisco News , the U.S. government announced it was sending 20,000 pounds of food to the pea-pickers’ campsite. But by the time it arrived, the still-anonymous woman and her family had moved on. Even as her image was widely reprinted and reproduced on everything from magazine covers to postage stamps, the “Migrant Mother” herself appeared to have vanished.

The Real ‘Migrant Mother’

Then in 1978, a woman named Florence Owens Thompson wrote a letter to the editor of the Modesto Bee newspaper. She was the mother in the famous “Migrant Mother” photo, Thompson said—and she wanted to set the record straight.

In an Associated Press article that followed, titled “Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo,” Thompson told a reporter that she felt “exploited” by Lange’s portrait. As Geoffrey Dunn wrote in the San Luis Obispo New Times in 2002 , Thompson and her children disputed other details in Lange’s account and sought to dispel the image of themselves as stereotypical Dust Bowl refugees.

Born in Oklahoma, Thompson was actually a full-blooded Native American; both her parents were Cherokee. In the mid-1920s, she and her first husband, Cleo Owens, moved to California, where they found mill and farm work. Cleo died of tuberculosis in 1931, and Florence was left to support six children by picking cotton and other crops.

When Bill Ganzel, a photographer for Nebraska Public Television, interviewed and photographed Thompson in 1979, she told him that while a young mother, she typically picked around 450-500 pounds of cotton a day, leaving home before daylight and coming home after dark. “We just existed,” she said. “We survived, let’s put it that way.”

When Lange found her in Nipomo that day in March 1936, she had two more children and was living with a man named Jim Hill, the father of her infant daughter Norma. After their car broke down on the way to find work picking lettuce, the family had been forced to pull off into the pea-pickers’ camp.

Two of Florence’s older sons were in town when the iconic picture was taken, getting the car’s radiator fixed. One of them, Troy Owens, flatly denied that his mother had sold their tires to buy food, as Lange had claimed. “I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another,” Troy told Dunn . “Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have."

Life After the Famous Photo

The family kept moving after Nipomo, following farm work from one place to another, and Florence would have three more children. After World War II , she settled in Modesto, California and married George Thompson, a hospital administrator.

By 1983, five years after claiming her identity as the “Migrant Mother,” Thompson was living alone in a trailer. She suffered from cancer and heart problems, and at one point her children had to solicit donations for her medical expenses. According to Dunn, thousands of letters poured in, along with more than $35,000 in contributions.

Florence Owens Thompson died in September 1983, just after her 80th birthday, ending a life marked by economic hardship, maternal sacrifice and human dignity.

Even President Ronald Reagan offered his condolences , writing that “Mrs. Thompson's passing represents the loss of an American who symbolizes strength and determination in the midst of the Great Depression.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Books For Review

- Why Publish with Oxford Art Journal?

- About Oxford Art Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Migrant Mother: Histories and Mythologies

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kimberly Schreiber, Migrant Mother: Histories and Mythologies, Oxford Art Journal , Volume 44, Issue 2, August 2021, Pages 346–350, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcab015

- Permissions Icon Permissions

While preparing for her 1966 retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Dorothea Lange noticed the fortuitous absence of her most well-known photograph of a pea picker and her children, commonly known as Migrant Mother , from a draft checklist. ‘It’d be alright with me to leave her out of the show. She’s been shown enough in that museum’, Lange told John Szarkowski, the exhibition’s curator, who strongly urged her to reconsider. ‘That’s right, okay, of course’ Lange acquiesced, ‘she, that one picture, belongs to the public really … she’s really made an expedition that woman … but let’s put her in some unexpected place, in some relationship … in a context people don’t think of her, that people don’t expect, give her a new both interpretation and understanding’. 1 Spoken just one year before her death in 1965, Lange’s comments and, in particular, her Migrant Mother fatigue are best understood, not simply as a response to the photograph’s immediate popularity after it was taken in 1936, but rather as a reaction to the overwhelming circulation of Migrant Mother throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

During his tenure as the Director of the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, Edward Steichen reintroduced Migrant Mother into public, visual culture, harnessing the photograph in order to reframe documentary as an essentially humanist or humanitarian endeavour. The photograph was featured in three exhibitions, including Steichen’s 1955 blockbuster show ‘The Family of Man’, which toured internationally for eight years and attracted over nine million visitors. So although, during the Great Depression, Lange’s photograph certainly reached a broad audience through mainstream newspapers and popular magazines, it was not until decades later that the photograph gained its almost universal recognisability, lending visual expression to, as Steichen wrote, ‘the endurance and fortitude that made the emergence from the Great Depression one of America’s most victorious hours’. 2 Alongside a massive boom in the post-war economy, Lange’s photograph of Florence Owen Thompson and her three daughters became steadily calcified within the popular American imagination as the ultimate signifier of ‘the Thirties’, ossifying her weather-beaten face and worried gaze into the visual–symbolic register of the Great Depression.

For Dorothea Lange in the mid-1960s, the saturation of the public sphere with countless reproductions and reinventions of Migrant Mother presented a methodological quagmire – one that turned around the gradual transformation of the photograph into an icon. Lange recognised that the vast celebrity of Migrant Mother threatened to eclipse the breadth of her oeuvre. In her quest to lead what she termed a ‘completely visual life’, Lange compiled tens of thousands of negatives and contact sheets: the notion that one image could contain her life’s work would have seemed absurd. However, in voicing her discomfort with the photograph, Lange does not simply reveal the way in which Migrant Mother posed a problem to her institutionalisation as an artist; rather, she suggests that the iconic photograph as a public, visual phenomenon conflicted with her conception of documentary. For Lange, meaning was never contained within the frame of a single or singular photograph; instead, it was produced within the series or on the page, always grounded through the use of extended captions or quotations from her subjects. Lange’s 1939 photobook An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion testifies to the tension that emerged between the increasingly singular Migrant Mother and her model of documentary, producing a conflict that Lange resolved by simply leaving the photograph out.

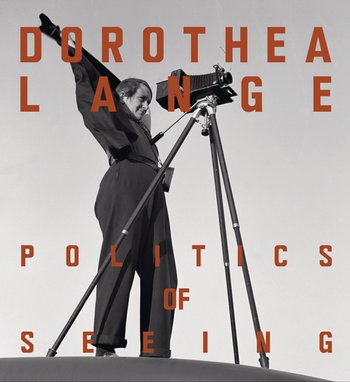

But although Lange and Szarkowski may have quickly settled the question of whether to include Migrant Mother in her 1966 retrospective, the problematic introduced by the photographic icon has not been so easily resolved. In the last several years, the issue has resurfaced in the work of numerous scholars, curators and photographers who have sought not only to reconsider Migrant Mother and its meanings, but also to re-evaluate Lange’s position within American photography and its histories. Several of these projects seek to circumvent Migrant Mother altogether, returning to Lange’s archive in order to broaden contemporary understandings of the photographer and her work. The 2018 exhibition at the Barbican Museum, for instance, endeavoured to correct disproportionate focus on Migrant Mother . ‘Her lifelong work’ the catalogue explains, ‘has been largely overshadowed by the iconic nature of her most famous image. The exhibition … seeks to redress this imbalance and reposition Lange as a critical voice in twentieth-century photography and a founding figure of documentary photographic practice’. 3 Similarly, in her book of photographs Day Sleeper , Sam Contis returned to the archive in order reframe dominant conceptions of Lange, tracing the leitmotif of the sleeping figure that recurs throughout her body of work. ‘The vast majority of images have never been publicly seen’. Contis recalls, ‘When I began visiting the archive in 2017, I came to realise that I had known only a small fraction of her work’ (p. 17).

While these interventions critically engage with Lange’s archive, recovering her more minor works in order to counterbalance the heightened visibility of Migrant Mother , two recent books – Sarah Meister’s Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother and Sally Stein’s Migrant Mother, Migrant Gender – have attempted to confront the iconic image more directly. These books suggest that in order to rethink Lange and her place within the history of photography, Migrant Mother can and should be re-read. A dialogue over why and how to return to Lange and, in particular, her most widely recognised photograph is born out in the references and footnotes of these two works, inviting a comparison between their disparate approaches and varying conclusions. What is revealed through the juxtaposition of these two texts is neither previously buried details about the creation of Migrant Mother nor formerly undisclosed elements of Lange’s biography – the books are roughly in agreement over the historical facts that surround the photograph and its maker. Instead, a comparison of these texts allows us to see the conflicting models through which the problems posed by the photographic icon can be unravelled. At stake in these books, therefore, is not simply a question of what the archive contains, but rather a debate over how the archive can read and whether a history of the icon can be written.

In her book Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother , Museum of Modern Art curator Sarah Meister returns to the photograph as part of the museum’s ‘One on One’ series, which offers extended meditations on single artworks from the collection. Although the book is framed as a reconsideration of Migrant Mother and promises ‘new insights’ into its history, the book nevertheless echoes the familiar beats that have given shape to many previous biographies of Lange’s early life, reproducing the photograph’s iconic status as an inevitable outcome of both Lange’s personal biography and the photograph’s exceptional formal qualities. While, in this account, Lange’s ‘natural sympathies’ and ‘evident compassion’ invariably led the photographer to create such a stirring portrait of a struggling mother, Migrant Mother ’s formal cohesion and balanced composition resulted in its inescapable singularity. With the snap of the shutter, Meister states, Lange ‘created an image that would become an icon, symbolising the Depression and the dire straits of agricultural workers … It is, rightfully, the most memorable and widely reproduced of the series. The superlatives that have been heaped upon it have done nothing to dilute its impact, nor have the passing decades diminished our inclination to empathise with the subject’s plight (pp. 18)’.

In order to strengthen this reading of Migrant Mother as a logical outgrowth of the historical record, Meister must flatten various interpretations of Lange and her work, articulated at several points throughout the middle of the twentieth century, into uniform evidence for the text’s arguments. A 1966 essay, for instance, written by American poet George P. Elliot for Lange’s posthumous retrospective, is quoted alongside a 1934 piece by Willard Van Dyke, who spent over a decade serving as the Director of the Department of Film at MoMA. This dizzying conflation between the 1930s and the 1960s obscures, rather than clarifies the ways in which our interpretations of Depression-era photography have been both coloured and curtailed by the institutionalisation of documentary in the post-war era. The person most responsible for shaping these dominant perceptions of the medium and its history is John Szarkowski, who served as MoMA’s Director of Photography from 1962 to 1991, and as Lange’s key interlocuter in the planning of her retrospective. In championing a rigidly formalist approach to understanding photography, Szarkowski divorced the single photograph from the printed page, essentialising the photograph as a unique product of the artist’s eye, as opposed to the result of an editorial hand.

Although certainly useful for the fine art museum, Szarowski’s frameworks have functioned to forestall a rigorously historical consideration of documentary and its function within the public sphere. These ghosts invariably haunt Meister’s related 2020 exhibition Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures , which creatively reframes the categories normally deployed to organise Lange’s work through a unifying focus on the role of text and its impact on the rhetorical meaning of photographic images. 4 By restoring the photograph to the magazine page and the photobook, the catalogue enriches our understanding of documentary as an inextricable part of public, visual culture, throwing into relief what is lost when photographs are displaced onto the gallery wall. But while the exhibition offers an important, if somewhat uneven, corrective to the long shadow of Szarkowski’s formalism, Meister’s consideration of Migrant Mother nevertheless remains in the thrall of both the icon and its creator, further naturalising its meaning as a Depression-era Madonna. In this way, Meister’s contributions to the discourse around Lange and Migrant Mother are afflicted by a central contradiction – one that stems from an unwillingness to examine the role MoMA has played in foreclosing the very same history of documentary that the institution seeks to recover today.

In her book, Migrant Mother, Migrant Gender , Sally Stein counters Meister’s approach, dislodging the many prevailing assumptions that continue to guide dominant interpretations of Lange’s photograph. Stein contends that the familiarity of Migrant Mother has paradoxically inured us to its contradictions and complexities, producing a discursive inertia that Stein convincingly upends. She demonstrates how existing understandings of the photograph have been undergirded by a blinding tautology; namely, as Stein puts it, ‘that this most famous Lange picture is ipso facto great chiefly because it has been so widely reproduced’. As a result, Stein argues, well-worn attributions of Migrant Mother ’s public resonance to its status as a secular ‘Madonna’ figure have been reflexively rehearsed, serving to obscure how and why the photograph has commanded such widespread attention. Stein refuses to allow the photograph’s now commonly accepted ‘iconic’ status to overdetermine her analysis. Unlike Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, who have sought to understand the enduring appeal of the iconic image and its role within liberal democracy, Stein gives Migrant Mother a history. 5

In doing so, Stein demystifies the aura of inevitability that clouds prevailing accounts of the photograph’s lasting popularity. While Stein agrees that the photograph is likely the last in the series of Nipomo exposures Lange captured, she rejects the notion that Migrant Mother constitutes the calculated refinement of Lange’s impulse towards Marian iconography. Stein problematises this linear narrative, challenging the prevailing assumption that photographic sequences inexorably build towards a formal and conceptual goal. She not only takes seriously a ‘blooper’ photograph in which one of Thompson’s children sabotages the photographic moment, but also decouples the physical proximity of the camera from notions of emotional intimacy. In paying close attention to Thompson’s strained left thumb, a detail that Lange later edited out of the composition in a ‘pictorialist gesture’, Stein argues that Migrant Mother captures ‘closeness as it tends to confine, sometimes unbearably (pp. 78)’. For Stein, the tightly-framed photograph speaks volumes, not of familial bonds, but of domestic bondage, offering insight into Lange’s vexed relationship to motherhood, as well as her desire to smooth over its blemishes.

Stein convincingly shores up this re-reading of Migrant Mother with a rigorous analysis of the immediate response to Lange’s Nipomo series. By attending to the wide variety of ways in which Lange’s negatives were put to work by the popular press, Stein reveals a considerable amount of ambivalence with regards to Migrant Mother and the broader series’ quality, as well as significant equivocation over the photographs’ many potential meanings. When several of Lange’s negatives were first published in The San Francisco News in March 1936, Migrant Mother was not included; and, in subsequent years, Migrant Mother often competed for public attention, vying with others from the series that created similar, if perhaps more conventional, juxtapositions between mother and child. Stein demonstrates how, far from understood as a ready-made image of domestic cohesion, Migrant Mother was made to take on a myriad rhetorical guises. In a September 1936 issue of Survey Graphic , for example, the photograph was featured alongside an article by Lange’s husband Paul Taylor, paired with the much more ambivalent title ‘Draggin' Around People’. By grounding her analysis in the visual and material culture of the 1930s, Stein throws into relief the contingency of history and the indeterminacy of meaning, providing a sharp antidote to the ideological miasma that often surrounds the Migrant Monther and renders its iconic status unavoidable.

Stein also deftly navigates the issue of Florence Thompson’s identity that has belaboured the discourse around Migrant Mother since the 1970s. Alongside many attempts to revisit the places and people enshrined by the Farm Security Administration, curiosity over the identity of Lange’s subject has motivated many writers and photographers to investigate the actual circumstances behind the photograph and to reconstruct the life story of its famous, yet nevertheless anonymous, subject. What often underpins these endeavours is not only the desire to rescue the individual from the generalising tendencies of representation, but also the compulsion to unmask the naïve, or even sinister, truth-claims of documentary. These aims crystallised most acutely in the work of freelance journalist and doctoral student Geoffrey Dunn who, in the 1990s, pieced together Thompson’s story through extensive interviews with her surviving relatives. The revelation of Thompson’s Cherokee heritage serves as Dunn’s smoking gun: the erasure of her genuine identity and blanket assumption of Thompson’s whiteness is laid entirely at Lange’s feet, supposedly testifying to the photographer’s ‘misleading’ practices and ‘colonialistic’ attitudes. 6

Stein not only rejects this argument, contending that Lange’s decision to ‘cast a Native American for the Euro-American role of the New Deal Madonna’ was probably not a conscious one, but also entirely reframes this line of inquiry. For Stein, what becomes legible in the unveiling of Thompson’s Cherokee heritage is not Lange’s personal beliefs or motivations, but rather the projected, cultural fantasies of Native American assimilation that, for many decades, sublimated Thompson into an idealised icon of white motherhood. ‘What better figure’ Stein asks, ‘with whom to create such a fantasy set of relations than a woman whose fair-haired child indicates that she has already entered the process of interracial union? (pp. 57)’ Stein reminds us that even, and perhaps especially, in their invisibility, private identities have public meanings. In doing so, she dramatically expands the terms through which Migrant Mother can be thought and read. In this way, Stein models a critical history of photography – one that does not simply seek to name the politics of an individual photograph or its maker, but historicises photography and its work within the complex networks in which images are circulated and take on their rhetorical value.

By refusing to engage in tired debates over the relative ethical merits of a photographer and their work, Stein offers a clear rebuke to those who have recently looked to Lange for a model of unimpeachable documentary ethics and, in doing so, ultimately reaffirmed postmodern critiques of the mode’s insufficient reflexivity. As the heavily mediatised crises of contemporary American political and economic life push questions of representation to the forefront of public discourse, the impulse to locate within the history of photography a set of ‘answers’ to the quagmires of representation has calcified in these attempts to recover Lange and her documentary practice. ‘More than anything else’, curator Drew Johnson opines, ‘it is this quality of collaboration and intimate connection that enabled Lange to avoid the exploitative tendencies of so much documentary photography’ (pp. 18). Here, Lange’s work is mined for evidence of alternative, implicitly female, documentary approach – one that, we are told, avoids the predatory, voyeuristic tendencies of her male counterparts. Similarly, for Sarah Meister, Lange’s use of direct quotes from her subjects, in contrast with her contemporaries, ‘reveals her particular commitment … to the authentic voices of the individuals represented in her photographs’. 7

So although many have vowed to offer a reconsideration of Lange and her work, by either going through or working against Migrant Mother , few have actually delivered on this promise. Through their inattention to historical difference, these efforts have not only further severed the icon from the material conditions in which it was created and circulated, but also reproduced a history of photography in which documentary is once again framed as dangerously uncritical and politically suspect. In anticipation of these charges, Meister, for instance, reassures us: ‘The fact that Lange was an employee of the federal government … had no impact on the character of her work’. By figuring Lange as exceptional, against, or outside documentary, these narratives reinforce, rather than unsettle the postmodern paradigms that have resulted in the repression of documentary from dominant histories of photography. To echo Sally Stein: What better figure with whom to create such a fantasy of ‘good’ representations than a photographer whose own marginality as a disabled woman indicates an ipso facto identification with her subjects? The spectres of humanism are still haunting the discourse around documentary and, as Stein suggests, the only way out is to write its history.

Dorothea Lange, Interview with KQED, Tape 42, Oakland Museum of California (1964).

Edward Steichen, The Bitter Years: 1935–1941, Rural America as seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962), p. iii.

Jane Alison and Marta Gili, ‘Forward’, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing , ed. by Alona Pardo (London: Prestel, 2018), p. 11.

Sarah Hermanson Meister, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2020).

Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Geoffrey Dunn, ‘Photographic License’, Santa Clara Metro 10:47 (19–25 January 1995), pp. 20–4.

Sarah Hermanson Meister, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2020), p. 18.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-7287

- Print ISSN 0142-6540

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Modernisms 1900-1980

Course: modernisms 1900-1980 > unit 8.

- Shigemi Uyeda's Reflections on the Oil Ditch: Getty Conversations

- Evans, Subway Passengers, New York City

- Ansel Adams: Visualizing a Photograph

- Behind the icon, Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother

- Lotte Jacobi, Albert Einstein

- Harold Edgerton, Milk-Drop Coronet Splash

- Esther Bubley, Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal

"I didn't want to stop, and didn’t. I didn’t want to remember that I had seen it, so I drove on and ignored the summons. … Having well convinced myself for twenty miles that I could continue on, I did the opposite. Almost without realizing what I was doing, I made a U-turn on the empty highway." [3]

"I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it. The pea crop at Nipomo had frozen and there was no work for anybody. But I did not approach the tents and shelters of other stranded pea-pickers. It was not necessary; I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment." [5]

The making of an iconic photograph

"When Dorothea took that picture, that was the ultimate. She never surpassed it. To me, it was the picture of Farm Security. The others were marvelous but that was special." [6]

Beyond iconicity: misrepresenting Migrant Mother ’s story

Living in the shadow of the photograph’s iconicity, want to join the conversation.

Migrant Mother

As was the custom among RA/FSA photographers who were trying to adhere to scientific method, her notes record no names but they do feature socioeconomic categories such as “destitute pea pickers” and “mother of seven children.” The picture itself needs no such help to draw on the prior decades of documentary photography. Direct exposure of ordinary, anonymous, working-class people engaged in the basic tasks of everyday life amidst degraded circumstances was the template of the social reform photography established by Lewis Hine and others in the early part of the twentieth century. The connection between photographic documentary and collective action was a well-established line of response, available as long as the photographer did not include the signs of other genres such as the focus on dramatic events of ordinary photojournalism or the obvious manipulation of art photography. Many other photos also met this standard, however, while the “Migrant Mother” quickly achieved critical acclaim as a model of documentary photography, becoming the preeminent photo among the hundreds of thousands of images being produced by RA/FSA photographers and used to promote New Deal policies. Roy Stryker, the head of the RA/FSA photography section, dubbed Lange’s photo the symbol for the whole project: “She has all the suffering of mankind in her but all of the perseverance too. A restraint and a strange courage. You can see anything you want to in her. She is immortal.” According to a manager at the Library of Congress, where the image remains one of the most requested items in the photography collection, “It’s the most striking image we have; it hits the heart.… an American icon.”

Taken within the context of the Great Depression, it is not difficult to see how the photograph captures simultaneously a sense of individual worth and class victimage. The close portraiture creates a moment of personal anxiety as this specific woman, without name, silently harbors her fears for her children, while the dirty, ragged clothes and bleak setting signify the hard work and limited prospects of the laboring classes. The disposition of her body—and above all, the involuntary gesture of her right arm reaching up to touch her chin—communicates related tensions. We see both physical strength and palpable worry: a hand capable of productive labor and an absent-minded motion that implies the futility of any action in such impoverished circumstances. The remainder of the composition communicates both a reflexive defensiveness, as the bodies of the two standing children are turned inward and away from the photographer (as if from an impending blow), and a sense of inescapable vulnerability, for her body and head are tilted slightly forward to allow each of the three children the comfort they need, her shirt is unbuttoned, and the sleeping baby is in a partially exposed position.

These features of the photograph are cues for emotional responses that the composition manages with great economy. At its most obvious, “Migrant Mother” communicates the pervasive and paralyzing fear that was widely acknowledged to be a defining characteristic of the depression and experienced by many Americans irrespective of income. Thus, the photograph embodies a limit condition for democracy identified by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his first inaugural address: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror.” Roosevelt could not embody that emotion without bringing the country down with him, but perhaps this correspondence accounts in part for each being the most memorable text and image from the era. The shift from his oratory to her visual image has other consequences as well. Embodiment provides a dual function emotionally: it both represents and localizes feelings that can literally know no bounds. By depicting what was known to be a generalized anxiety within the specific form of a woman’s body, that emotion is both made real and constrained by conventional attributions of gender.

Class difference is a touchy subject in American political culture, and its presence is often carefully veiled. In “Migrant Mother” class is framed and subordinated in its allusion to religious imagery and its articulation of gender and family relations. The religious allusion may seem obvious, for the photograph follows the template of the Madonna and Child that has been reproduced thousands of times in Western painting, Roman Catholic artifacts for both church and home, and folk art. The primary relationship within the composition is between the mother and the serene baby lying beside her exposed breast, while the other children double as the cherubs or other heavenly figures that typically surround the Madonna. The center-margin relationship establishes the mother as the featured symbol in the composition, while the surrounding figures fill out its theme. Their poses, with eyes averted, give the scene its deep Christian pathos. Their dirty clothes are evocative of the stable in Bethlehem, while their averted eyes make it clear that all is not right in this scene. Instead of heavenly majesty, the transcription from sacred to secular art features vulnerability.

Rather than merely another instance of reproduction, it is more accurate to see the Lange image as a transitional moment in public art. The “Migrant Mother” provides two parallel transcriptions of the Madonna and Child: the image moves from painting to photography, and the Mother of Christ becomes an anonymous woman of the working class. These shifts demonstrate how iconic appeal can be carried over from religious art to increasingly secular, bourgeois representation, and from fine arts institutions to public media. Indeed, there is another, intermediate predecessor that, as far as we know, has not been noted before: William Adolphe Bougeureau’s painting, Charity (1865). [Offsite link: See an image of the painting on the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery website.] The painting recasts the portrait of the Madonna and Child as a poor woman with a baby and two other ragged children; her face appears tired and anxious, she is staring blankly into the distance, and the children are asleep or looking away from the viewer. We do not know whether Lange was aware of Bougeureau’s portrait, which had been long consigned to oblivion by the modernist artists and writers that she admired. The comparison does remind one that iconic photographs can exemplify what had been characteristic of the Salon painters, the combination of technical realism and moral sentimentalism.

As Wendy Kozol has documented, the use of impoverished women with children to represent poverty had been established as a convention of reformist photography by the 1930s. Lange’s photograph evokes this “iconography of liberal reform” by the association of the children with their mother in a world of want while leaving the male provider, who had been “rendered ineffectual by the Depression,” out of the picture. The analogy with the image of the Madonna strengthens the call to the absent father, whose obligation to care for this woman and her children assumes Biblical proportions (and the structure of patriarchal responsibility and control). The photograph follows the conventional lines of gender by associating paralyzing fear with feminine passivity and keeping maternal concern separate from economic resources. The mother gathers her children to her, protecting them with her body, yet she is unable to provide for their needs. She cannot act, but she (and her children) provide the most important call for action. More to the point, the question posed by the photo is, Who will be the father? The actual father is neither present nor mentioned. The captioning never says something like, “A migrant mother awaits the return of her husband.” As with the Madonna, a substitution has occurred. Another provider is called to step into the husband’s place.

Any iconic photo structures relationships between those in the picture and the public audience; indeed, that rhetorical relationship is the most important appeal in the composition and the primary reason that the images can function as templates for public life. In the case of the Migrant Mother, the photograph interpellates the viewer in the position of the absent father. The viewer, though out of the picture, has the capacity for action identified with the paternal role. This position outside the image also doubles as a place of public identity, for the viewer is always being defined as part of a public audience by the photograph’s placement in the public media, while the public itself never can be seen directly. Thus, the public is cast in the traditional role of family provider, while the viewer becomes capable of potentially great power as part of a collective response. The mother’s dread and distress call forth the patriarchal duty to provide the food, shelter, and work that is needed to sustain the family, while the scale of the response can far exceed individual action. In fact, the picture already has rendered individual action secondary to an organized collective response (a response such as Roosevelt had called for to combat the terror “which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance”). Ironically, the “Migrant Mother” creates the greatest sense of deprivation in respect to one thing that the woman had: a husband who could provide for her. Yet by becoming the definitive representation of the Great Depression, the era is defined visually as Roosevelt proclaimed: a psychological condition and a failure of state action rather than a “failure of substance.”

One measure of the shift of responsibility from individual to collective action is that the woman’s husband is rarely if ever identified, and he remains a cipher throughout later narratives about the photograph and the woman and children in the frame. This marginal identity is marked in a poem dedicated to the photograph: “During bitter years, when fear and anger broke / Men without work or property to shadows.” The shadow father continues the Biblical allegory as well: just as Joseph is not the real father in the Christ myth, so the Migrant Mother’s husband is displaced by the higher power of the public (and its agency of the state). And like Joseph, he is kept offstage, mentioned only to fulfill the same role of providing social legitimacy for the woman and her children. By keeping the literal father offstage, actual economic relations are also subordinated to a dispensation of grace from a higher source of power that either has or acquires transcendental status. And just as identification with the religious icon makes the viewer an agent for continuing God’s work in the world, so does the secular icon make the public response of the viewer an impetus to state action.

By representing a common fear that transcends class and gender and by defining the viewer as one who can marshal collective resources to combat fear localized by class, gender, and family relations, “Migrant Mother” allows one to acknowledge paralyzing fear at the same time that it activates an impulse to do something about it. This formal design reveals an implicit movement from the aestheticization of poverty to a rhetorical engagement with the audience, from a compelling portrait to compelling action by the audience on behalf of the subject depicted. For those who initially encountered this photograph in the 1930s, the “Migrant Mother” captured a profound, generalized sense of vulnerability while simultaneously providing a localized means for breaking its spell. With the passage of time and for subsequent generations, the relationship between vulnerability and the need to act has been reversed somewhat, providing a localized sense of fear (by situating the subject of the photograph within a specific time, place, and class), and a generalized sense of action (by casting the viewing public, in whatever incarnation it might appear, in the position of acting on behalf of those in such circumstances). In short, the photograph compresses into a single image a rationale for the social welfare state. This rationale is not programmatic, of course, but emotional: the photograph works primarily to activate and manage feelings of both vulnerability and obligation that are endemic to our liberal-democratic culture.

The iconic power of Lange’s “Migrant Mother” is manifest in its continual and frequent reproduction since the 1930s as a symbolic representation of America’s communal faith in its capacity to confront and overcome despair and devastation. It is a visual commonplace that retains the aura of its original even as it is reproduced and divorced from its immediate cause and adapted to changing and different circumstances. More than just a representation of our past, it collapses past and present to create a structure of feeling. As Michael Denning notes, “its power lies largely in its iconic, non-narrative stasis, its sense of presence and being. The title seems an oxymoron, as if migrant and mother were contradictory; indeed, there is little sense of migration or movement in the photograph.” A fundamental property of still photography reinforces the idea that the image represents a condition rather than a moment in an unfolding story. The corresponding idea that completes the image dramatically is that any response to and change in that condition must come from outside the frame. Any subsequent narrative should be a story of how the condition was alleviated, not just for that woman, but for all those mired in poverty.

John Szarkowski once remarked that “one could do very interesting research about all of the ways that the Migrant Mother has been used; all of the ways that it has been doctored, painted over, made to look Spanish and Russian; and all the things it has been used to prove.” The photo’s legacy seems to have several, closely related articulations. The most obvious is its role as dominant image in collective memory of the Great Depression. This role is largely institutional: it is the issue of the school books, museum displays, postage stamps, didactic Web pages, and other media for organizing a national narrative for a popular audience. That story is buttressed by the second-order account of the photograph’s iconic status, as when the Art in America curricular package for teachers says “ Migrant Mother, a portrayal of a homeless working family, is an ICON of the Great Depression. ” Steady circulation of the photo and a recounting of its origin, nobility, effect, and stature not only keeps the image before the public but also maintains a structure of democratic representation. The relationships between the people in need, the people as a public, and the people as a state are mediated by the public practice of photojournalism, which in turn assists as it records the course of the nation through the vicissitudes of history.

Whether it is due more to the continued circulation of the photo or the implicit promise it offers about the political function of photojournalism, the icon seems to have become a template for images of want. In the 1970s, the image was appropriated by a Black Panther artist who rendered the photograph as a drawing that racialized the mother and her children, making them African American. The drawing emphasized race, an issue typically repressed in U.S. collective memory of the Great Depression, but the caption drew attention to the relationship between race and economic oppression, a problem that remained for African Americans after the initial successes of the civil rights movement began to fade into the background: “Poverty is a crime and our people are the victims.” The drawing thus conjured the structure of feeling that underscored the original photograph’s characterization of unwarranted victimage, albeit with regard to a different audience. This variation on the image extends across a range of ethnic groups and topics, as is evident from a Google search for “Migrant Mother.” The search turns up not only the original photo but also images of poor women with children who are struggling with poverty, addiction, and forced migration. The mothers range from Hispanic to Asian, sometimes their children are nursing (on the left breast, as the child in the iconic photo had done earlier) and sometimes they are just being held (as in the icon). The template also may be at work in a Time cover that places a woman carrying her child at the front of a migration of civilians during the war in Kosovo. [Offsite link: See this cover image on the Time website.] The relationship between an icon and a stock image may be hard to pin down, but as the captioning suggests, the lineage is there. It also may be reinforced by the circulation of a lesser known image taken during the same year (1936) of a nursing mother looking upward anxiously amidst a crowd in Estremadura, Spain. [Offsite link: See photo by David Seymour on the Corcoran Gallery website.] The single image of the iconic photograph both draws on older visual patterns and produces a logic of substitution and reinforcement, yet without losing its charismatic power.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the photograph was featured once again in a way that underscored its ideological significance, this time as a point of articulation between American liberal democracy and late capitalism. In 1978 the unnamed women in the photograph was identified in an Associated Press (AP) story published initially in the Los Angeles Times and then syndicated across the nation. She was Florence Thompson, a “75 year old Modesto woman.” The story, entitled “æCan’t Get a Penny’: Famed Photo’s Subject Feels She’s Exploited,” featured the original photograph, the cover of Roy Stryker’s edited volume In This Proud Land: America 1935û1943, and a picture of the now aging Thompson sitting in her trailer home adorned in glasses and what appears to be a polyester leisure suit. The story is not subtle in its contrast between the unnamed woman in the photograph and Thompson herself. The woman in the photograph is contemplative, apparently concerned about her children and family; Thompson is bitter, angry, alienated not so much by her past as a migrant worker but by the commodification of her image that completely divorced the woman in the photograph from the living Thompson. As she states in the story: “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t of taken my picture.… She didn’t take ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.” Admitting some pride in being the subject of a famous photograph, she concluded, “But what good’s it doing me?”

Here, of course, we see what happens when the living, named subject of the photograph speaks back in a way that undermines the structure of feeling that the photograph has conventionally evoked. In the original photograph the viewer is invited to identify with and act upon the victimage and despair of an anonymous migrant mother as a duty of family and community. Had Florence Thompson later expressed gratitude or marveled at how far the country had progressed or even hoped aloud that no one should have to go through such want and worry again, her voice would have echoed the photograph’s alignment of generalized sympathy and state action to alleviate the symptoms rather than the causes of inequity. When she speaks back and demands compensation, the aura of the original—or at least the presumed authenticity of the original structure of feeling—is destroyed, and underneath is revealed a harsh (and corrupting) world of alienated labor and commercial exploitation. The expectation created by the iconic image is that one should feel concern and commitment, a willingness to help those worthy of public support; instead, the AP article portrays greed and ingratitude.

This article is particularly troubling because it cuts in two directions. On the one hand, it questions the motives of Lange and those who subsequently have profited financially and otherwise from the photograph. On the other hand, it indicts Thompson, also characterized in the article as a “full-blooded Cherokee Indian,” who fails to understand her place in “America’s” collective memory, and who is made to appear willing to trade it all in for a few pieces of silver. In either case, the self-interested pursuit of gain at others’ expense contradicts the iconic bonding of individual need and collective action within an ethos of democratic community. If this exposé were to stick to the photograph it would make it difficult to preserve the significance of the image in U.S. public culture. The closing line of the article is poignantly ironic in this regard. Contrary to Thompson’s effort to exercise her property right to stop publication of the photo, “lawyers advised her it was not possible.” It is not so much a question of what is possible, however, but rather of what is appropriate. Once framed by the iconic image of the “Migrant Mother,” Florence Thompson’s liberalism is unseemly.

The story, however, does not end here. Five years later Thompson, now a victim of cancer, suffered a stroke that rendered her speechless. Once again the “Migrant Mother” appeared. This time, however, Thompson could not say the wrong thing, and she returned to her original subject position as a voiceless victim of a “paralyzing fear” with which all could identify. Her grown children, now voiced, explained that their mother lived on Social Security and that she had no medical insurance; she was a victim of circumstances. They thus pleaded for funds to help cover her medical costs. Over a period of several weeks she received $30,000 in contributions. Florence Thompson died shortly thereafter, but not before experiencing the impact of her own disembodied iconicity on U.S. public culture.

The story continues to circulate but not as the full story. It has been neatly edited to feature only the shift from poverty then to prosperity now, a change illustrated by a picture of mom with her three daughters from the photo, who now are beaming, healthy adults. [Offsite link: See the photograph on photographer Bill Ganzel’s website.] “Florence and her family came through the Depression and worked their way into the middle class,” we are told. What more does one need to know? Dad is still absent—not in the picture, and never mentioned—and perhaps that erasure schools the viewer not to ask too many questions. Yet despite the journey to Happyville, the second photo still contains a haunting echo of the original. Thompson does not look happy. Indeed, she looks beaten, with downcast eyes and a sagging body that is tilting sideways as if she might fall. More tellingly, her hands again speak volumes. The right hand is, after all those years, still touching her cheek in a gesture of self-consciousness or anxiety. The left hand, which in the original had been removed in the darkroom, now is holding on to her daughter’s arm as if for emotional support. Whereas her daughters look directly at the viewer with snapshot smiles, Thompson still is being offered for view. She remains passive, dependent on others for help, intimately tied to her family but an object rather than agent of public opinion. The narrative explains away this possible dissonance by saying that she felt more at home in the trailer than in the suburban tract house her children had provided her. Still a migrant, Thompson remains trapped in her past, unable to participate fully in the new culture of consumption. Her daughters have no such handicaps, however, and in any case the contradiction between individual self-assertion and collective identity has been artfully erased. Although Thompson and each of her three daughters in the picture now are named, she can never achieve full individuality, while their individual lives stand as narrative fulfillment of and substitute for the political program that undergirded their lives and came to be symbolized by her image.

The photo’s circulation as an icon also generates additional uses. As with any icon, it has been altered for comic effect, although less so than some. Frankly, there is little to exploit in that regard, and perhaps it is significant that the most widely available instances treat gender ironically. Some might conclude that use of the photograph in the 1996 Clinton campaign film “A Place Called America” was close to parody. The film’s organizational scheme is that of paging through a family photo album. The “Migrant Mother” appears and goes quickly by, as if one is looking at a shot of distant relatives or another family from the neighborhood. Too strong a connection would have made little sense during the roaring 1990s, but the almost subliminal presence at once situated the Clinton presidency within the tradition (and accomplishments) of the New Deal, while it constituted a visual (and perhaps only a visual) commitment to the continuation of the Democratic party’s program of social welfare. It is worth noting also that the image appeared amidst shots of military action. What otherwise would be an incongruous association provides a leveling of the hierarchy of national service. If antipoverty programs are as important as the army, then perhaps there was less reason to fault Clinton for his lack of a military record.

And the beat goes on. For a particularly weird example of how the icon of poverty can be used to promote prosperity, we note the January 1997 advertisement for an Arts and Entertainment Network show, “California and the Dream Seekers.” As a blonde woman drives a 1950s red convertible down Rodeo Drive, we see amidst the palm trees three sepia-tinged photos: one of a few guys using old movie cameras, one of a gold prospector and his mule, and the “Migrant Mother.” Perhaps she is just there to provide gender balance, but the brush with irony seems not to have bothered the ad writers. The accompanying text claims that “here [in California] they could escape their past and invent a new life,” and apparently we are to assume that the migrant mother made it, just as did the gold diggers before her, as did the early Hollywood cinema, which now provides the overwhelming validation of the story being told. It’s a good thing to chase dreams, at least if you do so in California. (This use of the photograph reminds us of the remark that the film Gandhi was a hit in Hollywood because its subject embodied their deepest commitments: he was thin and tan.) Marked by sepia tones as events thoroughly interned in the past—there are apparently no starving pea pickers today—the good life now is to be one’s individual pursuit of happiness, a life lived without collective obligations toward others.

Despite these examples of how the iconic image can be simultaneously relied on and diminished in use, the “Migrant Mother” still can be used for powerful statements on behalf of democracy’s promise of social and economic justice. The January 3, 2005, cover of the Nation is a case in point. The feature story is titled “Down and Out in Discount America.” The mother’s dress has been colorized blue and the woman is wearing a Wal-Mart jacket to which a nametag has been added. The designer’s description of his work reveals a clear sense of political artistry:

I think the inspiration is obvious: Wal-Mart is, in many ways, just a new Dustbowl for the workers in it, as it inspires a steady downward spiral of both shoppers and workers. Socially regressive institutions and circumstances still abound; it’s just that this one has better parking. Using the well-known Depression-era symbol of people (and women especially) going as far down as they can go seemed like an [ sic ] simple way to say that. Putting her in a Wal-Mart jacket shows the reason why it’s happening. And everyone who sees it gets it right away.

The “Migrant Mother” is a single, vivid image, and also a complex representation that draws together the reformist tradition of documentary photography, the pictorial conventions of religious iconography, and the interpellation of the public audience in the place of an absent father. Subsequent appropriations reflect varied structural and strategic interests, while they work with and reinforce the defining features of the composition. The image provides a powerful pattern of definition that then can be transposed to other times, social locales, and issues. It articulates a familiar yet complex structure of representation, emotional response, and collective action. It provides a stock resource for both advocacy on behalf of the dispossessed and affirmation of the society capable of meeting those needs. Thus, it outlines a set of conventions for public appeal that can in turn go through successive transpositions, yet it does so without cost to the aura of the original.

The icon’s power comes no more from its plasticity than it does from having a fixed meaning. Instead, the iconic photograph outlines a set of civic relationships in respect to fundamental tensions within liberal-democratic society. This is a society that has to honor both the common good and the individual pursuit of happiness, both the public representation of social reality and the mystification of economic relationships, both sacred images of the common people and a process of commodification. The “Migrant Mother” is only our first and perhaps least complicated example, but identifying the photograph’s several transcriptions and its range of appropriations already begins to trace the borders of the genre. That outline becomes clearer when we turn to the next image in our visual archive of collective memory.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 53-67 of No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy by Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.) Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy ©2007, 432 pages, 53 halftones Cloth $30.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-31606-2 (ISBN-10: 0-226-31606-8) For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for No Caption Needed . See also: Political Style: The Artistry of Power by Robert Hariman Our catalog of history titles Our catalog of rhetoric and communication titles Our catalog of media studies titles Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects Read the Chicago Blog

University of Chicago Press: 1427 E. 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637 USA | Voice: 773.702.7700 | Fax: 773.702.9756 Privacy Policies Site Map Bibliovault Chicago Manual of Style Turabian University of Chicago Awards --> Twitter Facebook YouTube

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Literary representations of migration.

- Marisel Moreno Marisel Moreno Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Notre Dame

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.371

- Published online: 23 May 2019

Migration has always been at the core of Latina/o literature. In fact, it would be difficult to find any work in this corpus that does not address migration to some extent. This is because, save some exceptions, the experience of migration is the unifying condition from which Latina/o identities have emerged. All Latinas/os trace their family origins to Latin America and/or the Hispanic Caribbean. That said, not all of them experience migration first-hand or in the same manner; there are many factors that determine why, how, when, and where migration takes place. Yet, despite all of these factors, it is safe to say that a crucial reason behind the mass movements of people from Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean to the United States has been direct or indirect US involvement in the countries of origin. This is evident, for instance, in the cases of Puerto Rico (invasion of 1898) and Central America (civil wars in the 1980s), where US intervention led to migration to the United States in the second half of the 20th century. Other factors that tend to affect the experience of migration include nationality, class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, language, citizenship status, age, ability, and the historical juncture at which migration takes place.

The heterogeneous ways in which migration is represented in Latina/o literature reflect the wide range of factors that influence and shape the experience of migration. Latina/o narrative, poetry, theatre, essay, and other forms of literary expressions capture the diversity of the migration experience. Some of the constant themes that emerge in these works include nostalgia, transculturation, discrimination, racism, uprootedness, hybridity, and survival. In addressing these issues, Latina/o literature brings visibility to the complexities surrounding migration and Latina/o identity, while undermining the one-dimensional and negative stereotypes that tend to dehumanize Latinas/os in US dominant society. Most importantly, it allows the public to see that while migration is complex and in constant flux, those who experience it are human beings in search for survival.

- Latina/o literature

- Latin America

- Hispanic Caribbean

- transculturation

- marginality

- displacement

- undocumented migration

- forced migration

Migration has always been a central theme in Latina/o literature because movement and displacement are at the core of the US Latina/o experience. The label “Latina/o” itself hints at the idea of movement because it is used to refer to people of Latin American or Hispanic Caribbean descent in the United States. 1 For some Latinas/os, the experience of migration is personal; it is something that they have lived through and recall. For others, it is more of a distant or inherited memory, sometimes passed down from generation to generation. Yet even in cases where there is significant temporal and physical distance from the country of origin, the Latina/o experience in the United States tends to be informed and shaped by the legacy of movement, albeit to different degrees. Migration in Latina/o literature refers not only to the actual process of moving but also to the emotional, psychological, and socioeconomic impact that that process has on individuals, families, and communities. Because of the different contexts in which migration tends to occur, as well as the multiplicity of variables that inform it—race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, age, religion, education, political affiliation, citizenship status, culture, mode of transportation, nationality, generation, and ability—it is important to recognize its fluidity. There is not only one typical Latina/o migration experience, but rather there are multiple ones, and Latina/o literature offers a window into that diversity.

Broadly speaking, the representation of migration in Latina/o narrative, poetry, drama, essay, and other literary forms usually encompasses themes such as displacement (for political and economic reasons), nostalgia, uprootedness, transculturation, cultural hybridity, biculturalism, bilingualism, survival, the American Dream, adaptation, exclusion, discrimination, prejudice, and marginality. Yet the development of these themes varies significantly among writers and works. The extent to which migration is depicted as a positive or negative experience reflects how deeply personal it is. Migration does not occur in a vacuum; it is informed, influenced, and determined by economic, political, and social forces, structures, and circumstances that usually are beyond an individual’s control. As a result, literary texts often reveal the tensions that emerge between the personal and the systemic forces at play. A cursory review of Latina/o literature suffices to illustrate the plurality of experiences surrounding the theme of migration. Precisely because of the immeasurable breadth of the topic, this article does not seek to offer an exhaustive examination, but rather aims to provide a general overview of the representation of migration in Latina/o literary production. Likewise, it is not possible to mention or cover every Latina/o author, poet, or literary work that deals with this theme. The works discussed here have been selected because they illustrate some of the predominant tendencies regarding the representation of migration in this area. The reader should be aware, however, that they constitute a limited sample of the vast and rich literary production that addresses this theme.

Migration from Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean to the United States has been taking place for centuries. Shifting geopolitical borders, in addition to and informed by US economic, neocolonial, and neo-imperialist interests, are some of the reasons behind the mass displacements from these regions. Continuous US interventions, occupations, and invasions throughout the region for economic, political, or military reasons—informed by the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine—have resulted in significant migration from Latin America and the Caribbean to the United States. 2

Although there has been a Latin American and Hispanic Caribbean presence in the United States since the 19th century , the first significant wave of Mexican migration took place as a result of the Mexican Revolution ( 1910–1920 ). Additional waves from other countries followed, and they significantly accelerated at about the middle of the 20th century , in part as a result of technological advances. Some of the reasons for this displacement include political exile, civil wars, dictatorial and authoritarian regimes, cartel and gang violence, ethno-racial prejudice and violence, the search for economic opportunities, family reunification, and persecution due to gender and sexual orientation. Some of these reasons are more urgent than others, but in the end they all have one thing in common: survival. When reflecting on the topic of migration, place of origin is of crucial importance given the specific political and socioeconomic circumstances that characterize each country’s migration history, as well as US policy toward them. This is evident, for instance, in the distinctions that emerge between the representations of migration in the works of US Puerto Ricans (who are US citizens and colonial subjects), Cuban Americans (who fled an authoritarian regime and extreme poverty), and Salvadoran Americans (who escaped the violence of civil war and drug cartels).

Although clear distinctions emerge between histories of migration by country of origin, differences can be found within countries, as well. It is possible for distinct waves of immigrants from the same country to have completely divergent experiences. This is evident in the contrast that emerges between the welcoming reception experienced by upper- and middle-class Cubans who fled after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and the rejection felt by their compatriots, the underprivileged dark-skinned balseros (rafters) who escaped in makeshift vessels in the 1990s and who, unlike their predecessors, were not immediately allowed into the United States. 3 Another crucial factor in the way migration is represented in literature is generation. With some exceptions, the closer an author is to the actual experience of migration, the more pronounced are the themes of nostalgia, longing, anger, or sense of uprootedness. For Latinas/os who belong to the one-and-a-half and second generations, the themes of biculturalism, bilingualism, hybridity, and integration into US society tend to be at the forefront. Regardless of the generation, however, the success or (most often) the failure to attain the American Dream seems to loom large in Latina/o writing.

Mode of transportation is another variable that is tied to the conditions that inform migration and that also determines how this experience is perceived and conveyed in literature. Until the mid- 20th century most migrants arrived in the United States by train or ship, and later on commercial flights. Yet it is important to remember that the mode of transportation is determined by a range of factors that includes an individual’s status, capital, location, and US immigration policy toward the country of origin at that specific historical juncture. Since the late 20th century undocumented Mexican, Central American, and South American migrants have risked their lives walking and riding on top of trains in order to cross the Mexico-US border. Cuban migration through Mexico has increased since the early 21st century . Likewise, for decades unauthorized Dominicans and Cubans have attempted to cross the ocean using yolas and balsas (makeshift rafts) to reach Puerto Rico and the Florida Keys, many perishing in the process.

The way migration is understood has also shifted in recent times. Traditionally thought of as a permanent unidirectional displacement, migration has been transformed by technological advances and globalization, which allow short-term and circular migration to take place. The length of stay in the United States is often determined by push-pull factors including political and socioeconomic conditions in the United States and the country of origin. Since the late 20th century , return migration (to the home country) and circular (back-and-forth) migration have become common, and they contribute to the constant reinforcement and revitalization of transnational ties between populations in the countries of origin and their diasporas. Transmigration, in turn, has led to the interrogation and challenging of cultural, racial, and gender norms in the countries of origin. As migrants move between their home and host countries, their worldviews and perceptions—which travel with them—have led to the dismantling of static notions of identity. One example is the understanding of race: in the United States this is defined by the black-white paradigm, but it is much more nuanced in Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean. Many Latinos/as have embraced their African roots as a result of their experiences living or growing up in the diaspora. This attitude marks a shift in mentality regarding prevailing identity discourses in the countries of origin, given that blackness and the African heritage have tended to be minimized or denied across Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean.

As must be evident by now, migration is a highly complex phenomenon that is experienced, understood, and conveyed in different ways by different people. Because the majority of Latina/o literature has been produced since the mid- 20th century , this article focuses on works published from the 1960s to the present. It is divided by country or region of origin in order to offer the reader a more cohesive overview of migration in Latina/o literature.

Mexican American Literature

A discussion of the Mexican presence in the United States must take into account the shifting geopolitical borders between the two nations. There has been a significant Mexican presence in the United States since 1848 , when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed to put an end to the Mexican-American War. As a result of the treaty and the definition of a new Mexico-US border, the United States absorbed expansive territories that once belonged to Mexico and the populations that had lived on those lands for generations. 4 The first significant wave of Mexican migration to the United States took place as a result of the Mexican Revolution, when thousands tried to escape the violence of war. Mexican and Mexican American workers became the backbone of the US economy during this period, but as a result of the Great Depression in 1929 , thousands were forcibly deported to Mexico. Throughout the 20th century , the push-pull factors that have influenced Mexican migration have mirrored the interdependency that has long existed between the Mexican and US economies. The Bracero Program, for instance, brought thousands of Mexicans to the United States as temporary workers from 1940s to the 1960s, a time when the country desperately needed an expendable workforce. 5 Although the vast majority of Mexicans in the United States have migrated to the country legally, many have done so without documents. Because the US economy and large corporations rely on a cheap labor force, Mexicans trying to escape extreme poverty and violence have been lured to the United States to work, even under conditions of exploitation. Gloria Anzaldúa’s foundational text Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza ( 1987 ) is indispensable reading for anyone seeking to better understand the Mexico-US border, its borderlands, and migration through the lens of intersectionality.

Although Mexican American literary production is quite vast, migration has remained a major theme. Migration is at the heart of . . . y no se lo tragó la tierra ( 1971 ) by Tomás Rivera, also known as the “father of Chicano literature.” Within the narrative frame the reader does not observe the characters crossing the Mexico-US border, but nonetheless as migrant farmworkers they are in a constant state of displacement. Uprootedness and dislocation characterize the lives of the people in this tight-knit community as they travel the migrant circuit between Texas and Minnesota searching for work during the harvest season. The impact of this difficult lifestyle on the unnamed boy protagonist—who provides a sense of unity to a story told from multiple perspectives and in multiple voices—is evident as we observe him struggling at school. In this bildungsroman we not only see the protagonist dealing with the challenges of adolescence but also see how his life as a migrant farmworker leads to an early loss of innocence. Prejudice, racism, exploitation, and extreme poverty are the defining conditions of life in this community. From the death of his aunt and uncle to the heatstroke that almost kills his own father and little brother, abuse at the hands of a corrupt couple who takes advantage of his family, and his expulsion from school after being a victim of bullying, the protagonist faces countless hardships. Yet he does not conform to the role of victim, a position that the adults in the community seem resigned to accepting. On the contrary, he challenges authority by questioning the system that keeps the group oppressed and by questioning God for not protecting his people. Through a series of gestures, the boy makes clear that he is ready to fight for his dignity, thus heralding the rebellious youth spirit that coalesced during the Chicano movement in the 1960s and 1970s.