- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Critical Thinking and Effective Communication: Enhancing Interpersonal Skills for Success

In today’s fast-paced world, effective communication and critical thinking have become increasingly important skills for both personal and professional success. Critical thinking refers to the ability to analyze situations, gather information, and make sound judgments, while effective communication involves not only conveying ideas clearly but also actively listening and responding to others. These two crucial abilities are intertwined, as critical thinking often mediates information processing, leading to a more comprehensive understanding and ultimately enhancing communication.

The importance of critical thinking and effective communication cannot be overstated, as they are essential in various aspects of life, including problem-solving, decision-making, and relationship-building. Additionally, these skills are indispensable in the workplace, as they contribute to overall productivity and foster a positive and collaborative environment. Developing and nurturing critical thinking and effective communication abilities can significantly improve both personal and professional experiences, leading to increased success in various realms of life.

Key Takeaways

- Critical thinking and effective communication are essential skills for personal and professional success.

- These abilities play a vital role in various aspects of life, including problem-solving, decision-making, and relationship-building.

- Developing and honing critical thinking and communication skills can lead to increased productivity and a more positive, collaborative environment.

Critical Thinking Fundamentals

Skill and knowledge.

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive skill that individuals should cultivate in order to master effective communication. It is the ability to think clearly and rationally, understand the logical connections between ideas, identify and construct arguments, and evaluate information to make better decisions in personal and professional life [1] . A well-developed foundation of knowledge is crucial for critical thinkers, as it enables them to analyze situations, evaluate arguments, and draw, inferences from the information they process.

Analysis and Evidence

A key component of critical thinking is the ability to analyze information, which involves breaking down complex problems or arguments into manageable parts to understand their underlying structure [2] . Analyzing evidence is essential in order to ascertain the validity and credibility of the information, which leads to better decision-making. Critical thinkers must consider factors like the source’s credibility, the existence of potential biases, and any relevant areas of expertise before forming judgments.

Clarity of Thought

Clarity of thought is an integral element of critical thinking and effective communication. Being able to articulate ideas clearly and concisely is crucial for efficient communication [3] . Critical thinkers are skilled at organizing their thoughts and communicating them in a structured manner, which is vital for ensuring the transmission of accurate and relevant information.

In summary, mastering critical thinking fundamentals, including skill and knowledge, analysis of evidence, and clarity of thought, is essential for effective communication. Cultivating these abilities will enable individuals to better navigate their personal and professional lives, fostering stronger, more efficient connections with others.

Importance of Critical Thinking

Workplace and leadership.

Critical thinking is a vital skill for individuals in the workplace, particularly for those in leadership roles. It contributes to effective communication, enabling individuals to articulate their thoughts clearly and understand the perspectives of others. Furthermore, critical thinking allows leaders to make informed decisions by evaluating available information and considering potential consequences. Developing this skill can also empower team members to solve complex problems by exploring alternative solutions and applying rational thinking.

Decisions and Problem-Solving

In both personal and professional contexts, decision-making and problem-solving are crucial aspects of daily life. Critical thinking enables individuals to analyze situations, identify possible options, and weigh the pros and cons of each choice. By employing critical thinking skills, individuals can arrive at well-informed decisions that lead to better outcomes. Moreover, applying these skills can help to identify the root cause of a problem and devise innovative solutions, thereby contributing to overall success and growth.

Confidence and Emotions

Critical thinking plays a significant role in managing one’s emotions and cultivating self-confidence. By engaging in rational and objective thinking, individuals can develop a clearer understanding of their own beliefs and values. This awareness can lead to increased self-assurance and the ability to effectively articulate one’s thoughts and opinions. Additionally, critical thinking can help individuals navigate emotionally-charged situations by promoting logical analysis and appropriate emotional responses. Ultimately, honing critical thinking skills can establish a strong foundation for effective communication and emotional intelligence.

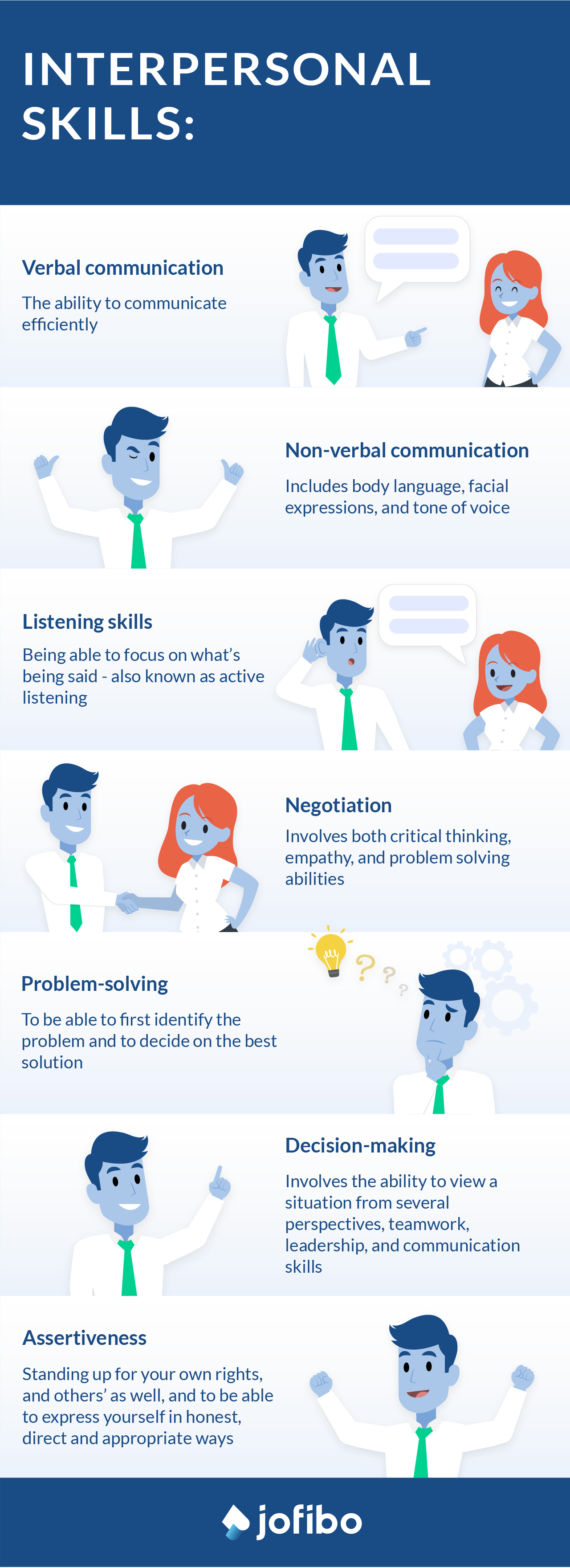

Effective Communication

Effective communication is essential in building strong relationships and achieving desired outcomes. It involves the exchange of thoughts, opinions, and information so that the intended message is received and understood with clarity and purpose. This section will focus on three key aspects of effective communication: Verbal Communication, Nonverbal Communication, and Visual Communication.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communication is the use of spoken or written words to convey messages. It is vital to choose the right words, tone, and structure when engaging in verbal communication. Some elements to consider for effective verbal communication include:

- Being clear and concise: Focus on the main points and avoid unnecessary information.

- Active listening: Give full attention to the speaker and ask questions for clarification.

- Appropriate language: Use language that is easily understood by the audience.

- Emotional intelligence: Understand and manage emotions during communication.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication involves gestures, body language, facial expressions, and other visual cues that complement verbal messages. It plays a crucial role in conveying emotions and intentions, and can often have a significant impact on the effectiveness of communication. Some key aspects of nonverbal communication are:

- Eye contact: Maintaining eye contact shows that you are attentive and engaged.

- Posture: Good posture indicates confidence and credibility.

- Gestures and facial expressions: Use appropriate gestures and facial expressions to support your message.

- Proximity: Maintain a comfortable distance from your audience to establish rapport.

Visual Communication

Visual communication involves the use of visual aids such as images, graphs, charts, and diagrams to support or enhance verbal messages. It can help to make complex information more understandable and engaging. To maximize the effectiveness of visual communication, consider the following tips:

- Relevance: Ensure that the visual aids are relevant to the message and audience.

- Simplicity: Keep the design and content simple for easy comprehension.

- Consistency: Use a consistent style, format, and color scheme throughout the presentation.

- Accessibility: Make sure that the visual aids are visible and clear to all audience members.

In conclusion, understanding and implementing verbal, nonverbal, and visual communication skills are essential for effective communication. By combining these elements, individuals can establish strong connections, and successfully relay their messages to others.

Critical Thinking Skills in Communication

Listening and analyzing.

Developing strong listening and analyzing skills is crucial for critical thinking in communication. This involves actively paying attention to what others are saying and sifting through the information to identify key points. Taking a step back to analyze and evaluate messages helps ensure a clear understanding of the topic.

By improving your listening and analyzing abilities, you become more aware of how people communicate their thoughts and ideas. Active listening helps you dig deeper and discover the underlying connections between concepts. This skill enhances your ability to grasp the core meaning and identify any ambiguities or inconsistencies.

Biases and Perspective

Recognizing biases and considering different perspectives are essential components of critical thinking in communication. Everyone has preconceived notions and beliefs that can influence their understanding of information. By being aware of your biases and actively questioning them, you can strengthen your ability to communicate more effectively.

Considering other people’s perspectives allows you to view an issue from multiple angles, eventually leading to a more thorough understanding. Approaching communications with an open and receptive mind gives you a greater ability to relate and empathize with others, which in turn enhances the overall effectiveness of communication.

Problem-Solving and Questions

Critical thinking is intrinsically linked to problem-solving and asking questions. By incorporating these skills into the communication process, you become more adept at identifying issues, formulating solutions, and adapting the way you communicate to different situations.

Asking well-crafted questions helps you uncover valuable insights and points of view that may be hidden or not immediately apparent. Inquiring minds foster a more dynamic and interactive communication; promoting continuous learning, growth, and development.

Ultimately, enhancing your critical thinking skills in communication leads to better understanding, stronger connections, and more effective communication. By combining active listening, awareness of biases and perspectives, and problem-solving through questioning, you can significantly improve your ability to navigate even the most complex communications with confidence and clarity.

Improving Critical Thinking and Communication

Methods and techniques.

One approach to improve critical thinking and communication is by incorporating various methods and techniques into your daily practice. Some of these methods include:

- Asking open-ended questions

- Analyzing information from multiple perspectives

- Employing logical reasoning

By honing these skills, individuals can better navigate the complexities of modern life and develop more effective communication capabilities.

Problem-Solving Skills

Developing problem-solving skills is also essential for enhancing critical thinking and communication. This involves adopting a systematic framework that helps in identifying, analyzing, and addressing problems. A typical problem-solving framework includes:

- Identifying the problem

- Gathering relevant information

- Evaluating possible solutions

- Choosing the best solution

- Implementing the chosen solution

- Assessing the outcome and adjusting accordingly

By mastering this framework, individuals can tackle problems more effectively and communicate their solutions with clarity and confidence.

Staying on Point and Focused

Staying on point and focused is a critical aspect of effective communication. To ensure that your message is concise and clear, it is crucial to:

- Determine the main purpose of your communication

- Consider the needs and expectations of your audience

- Use precise language to convey your thoughts

By maintaining focus throughout your communication, you can improve your ability to think critically and communicate more effectively.

In summary, enhancing one’s critical thinking and communication skills involves adopting various techniques, honing problem-solving skills, and staying focused during communication. By incorporating these practices into daily life, individuals can become more confident, knowledgeable, and capable communicators.

Teaching and Training Critical Thinking

Content and curriculum.

Implementing critical thinking in educational settings requires a well-designed curriculum that challenges learners to think deeply on various topics. To foster critical thinking, the content should comprise of complex problems, real-life situations, and thought-provoking questions. By using this type of content , educators can enable students to analyze, evaluate, and create their own understandings, ultimately improving their ability to communicate effectively.

Instructors and Teachers

The role of instructors and teachers in promoting critical thinking cannot be underestimated. They should be trained and equipped with strategies to stimulate thinking, provoke curiosity, and encourage students to question assumptions. Additionally, they must create a learning environment that supports the development of critical thinking by being patient, open-minded, and accepting of diverse perspectives.

Engaging Conversations

Conversations play a significant role in the development of critical thinking and effective communication skills. Instructors should facilitate engaging discussions, prompt students to explain their reasoning, and ask open-ended questions that promote deeper analysis. By doing so, learners will be able to refine their ideas, understand various viewpoints, and build their argumentation skills, leading to more effective communication overall.

Critical thinking and effective communication are two interrelated skills that significantly contribute to personal and professional success. Through the application of critical thinking , individuals can create well-structured, clear, and impactful messages.

- Clarity of Thought : Critical thinking helps in organizing thoughts logically and coherently. When engaging in communication, this clarity provides a strong foundation for conveying ideas and opinions.

- Active Listening : A crucial aspect of effective communication involves actively listening to the messages from others. This allows for better understanding and consideration of multiple perspectives, strengthening the critical thinking process.

- Concise and Precise Language : Utilizing appropriate language and avoiding unnecessary jargon ensures that the message is easily understood by the target audience.

Individuals who excel in both critical thinking and communication are better equipped to navigate complex situations and collaborate with others to achieve common goals. By continuously honing these skills, one can improve their decision-making abilities and enhance their relationships, both personally and professionally. In a world where effective communication is paramount, mastering critical thinking is essential to ensuring one’s thoughts and ideas are received and understood by others.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the essential aspects of critical thinking.

Critical thinking involves the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to make sound decisions and solve problems. Essential aspects of critical thinking include asking better questions , identifying and challenging assumptions, understanding different perspectives, and recognizing biases.

How do communication skills impact problem-solving?

Effective communication skills are crucial in problem-solving, as they facilitate the exchange of information, ideas, and perspectives. Clear and concise communication helps ensure that all team members understand the problem, the proposed solutions, and their roles in the process. Additionally, strong listening skills enable better comprehension of others’ viewpoints and foster collaboration.

How does language influence critical thinking?

Language plays a key role in critical thinking, as it shapes the way we interpret and express information. The choice of words, phrases, and structures can either clarify or obscure meaning. A well-structured communication promotes a better understanding of complex ideas, making it easier for individuals to think critically and apply the concepts to problem-solving.

What strategies can enhance communication in critical thinking?

To enhance communication during critical thinking, individuals should be clear and concise in expressing their thoughts, listen actively to others’ perspectives, and use critical thinking skills to analyze and evaluate the information provided. Encouraging open dialogue, asking probing questions, and being receptive to feedback can also foster a conducive environment for critical thinking.

What are the benefits of critical thinking in communication?

Critical thinking enhances communication by promoting clarity, objectivity, and logical reasoning. When we engage in critical thinking, we question assumptions, consider multiple viewpoints, and evaluate the strength of arguments. As a result, our communication becomes more thoughtful, persuasive, and effective at conveying the intended message .

How do critical thinking skills contribute to effective communication?

Critical thinking skills contribute to effective communication by ensuring that individuals are able to analyze, comprehend, and interpret the information being shared. This allows for more nuanced understanding of complex ideas and helps to present arguments logically and coherently. Additionally, critical thinking skills can aid in identifying any underlying biases or assumptions in the communicated information, thus enhancing overall clarity and effectiveness.

You may also like

Critical Thinking vs Positive Thinking (The Pros and Cons)

In a world where we are expected to be on top of things every second of the day, having the best coping […]

Critical Reading Strategies

Critical thinking is all about deeply analyzing and considering every aspect of any given information. Applying critical thinking to reading can go […]

Critical Thinking Brain Teasers: Enhance Your Cognitive Skills Today

Critical thinking brain teasers are an engaging way to challenge one’s cognitive abilities and improve problem-solving skills. These mind-bending puzzles come in […]

How to Overcome Critical Thinking Barriers

Critical thinking is typically needed when graded performances and livelihoods are involved. However, its true value shines outside of academic and professional […]

Collaborative Learning and Critical Thinking

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Anu A. Gokhale 2

2439 Accesses

28 Citations

Cooperative learning ; Creative thinking ; Problem-solving

The term “collaborative learning” refers to an instruction method in which students at various performance levels work together in small groups toward a common goal. Collaborative learning is a relationship among learners that fosters positive interdependence, individual accountability, and interpersonal skills. “Critical thinking” involves asking appropriate questions, gathering and creatively sorting through relevant information, relating new information to existing knowledge, reexamining beliefs, reasoning logically, and drawing reliable and trustworthy conclusions.

Theoretical Background

The advent of revolutionary information and communication technologies has effected changes in the organizational infrastructure and altered the characteristics of the workplace putting an increased emphasis on teamwork and processes that require individuals to pool their resources and integrate specializations. The...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

American Philosophical Association. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. ERIC document ED (pp. 315–423).

Google Scholar

Cooper, J., Prescott, S., Cook, L., Smith, L., Mueck, R., & Cuseo, J. (1990). Cooperative learning and college instruction: Effective use of student learning teams . Long Beach: California State University Foundation.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7 (1), 22–30.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and competition: Theory and research . Edina: Interaction Book Company.

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., & Hesse, F. (2006). Collaboration scripts – A conceptual analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 18 (2), 159–185.

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technology, Illinois State University, Campus Box 5100, Normal, IL, 61790-5110, USA

Dr. Anu A. Gokhale

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anu A. Gokhale .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Gokhale, A.A. (2012). Collaborative Learning and Critical Thinking. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_910

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_910

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

How to build critical thinking skills for better decision-making

It’s simple in theory, but tougher in practice – here are five tips to get you started.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Have you heard the riddle about two coins that equal thirty cents, but one of them is not a nickel? What about the one where a surgeon says they can’t operate on their own son?

Those brain teasers tap into your critical thinking skills. But your ability to think critically isn’t just helpful for solving those random puzzles – it plays a big role in your career.

An impressive 81% of employers say critical thinking carries a lot of weight when they’re evaluating job candidates. It ranks as the top competency companies consider when hiring recent graduates (even ahead of communication ). Plus, once you’re hired, several studies show that critical thinking skills are highly correlated with better job performance.

So what exactly are critical thinking skills? And even more importantly, how do you build and improve them?

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the ability to evaluate facts and information, remain objective, and make a sound decision about how to move forward.

Does that sound like how you approach every decision or problem? Not so fast. Critical thinking seems simple in theory but is much tougher in practice, which helps explain why 65% of employers say their organization has a need for more critical thinking.

In reality, critical thinking doesn’t come naturally to a lot of us. In order to do it well, you need to:

- Remain open-minded and inquisitive, rather than relying on assumptions or jumping to conclusions

- Ask questions and dig deep, rather than accepting information at face value

- Keep your own biases and perceptions in check to stay as objective as possible

- Rely on your emotional intelligence to fill in the blanks and gain a more well-rounded understanding of a situation

So, critical thinking isn’t just being intelligent or analytical. In many ways, it requires you to step outside of yourself, let go of your own preconceived notions, and approach a problem or situation with curiosity and fairness.

It’s a challenge, but it’s well worth it. Critical thinking skills will help you connect ideas, make reasonable decisions, and solve complex problems.

7 critical thinking skills to help you dig deeper

Critical thinking is often labeled as a skill itself (you’ll see it bulleted as a desired trait in a variety of job descriptions). But it’s better to think of critical thinking less as a distinct skill and more as a collection or category of skills.

To think critically, you’ll need to tap into a bunch of your other soft skills. Here are seven of the most important.

Open-mindedness

It’s important to kick off the critical thinking process with the idea that anything is possible. The more you’re able to set aside your own suspicions, beliefs, and agenda, the better prepared you are to approach the situation with the level of inquisitiveness you need.

That means not closing yourself off to any possibilities and allowing yourself the space to pull on every thread – yes, even the ones that seem totally implausible.

As Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D. writes in a piece for Psychology Today , “Even if an idea appears foolish, sometimes its consideration can lead to an intelligent, critically considered conclusion.” He goes on to compare the critical thinking process to brainstorming . Sometimes the “bad” ideas are what lay the foundation for the good ones.

Open-mindedness is challenging because it requires more effort and mental bandwidth than sticking with your own perceptions. Approaching problems or situations with true impartiality often means:

- Practicing self-regulation : Giving yourself a pause between when you feel something and when you actually react or take action.

- Challenging your own biases: Acknowledging your biases and seeking feedback are two powerful ways to get a broader understanding.

Critical thinking example

In a team meeting, your boss mentioned that your company newsletter signups have been decreasing and she wants to figure out why.

At first, you feel offended and defensive – it feels like she’s blaming you for the dip in subscribers. You recognize and rationalize that emotion before thinking about potential causes. You have a hunch about what’s happening, but you will explore all possibilities and contributions from your team members.

Observation

Observation is, of course, your ability to notice and process the details all around you (even the subtle or seemingly inconsequential ones). Critical thinking demands that you’re flexible and willing to go beyond surface-level information, and solid observation skills help you do that.

Your observations help you pick up on clues from a variety of sources and experiences, all of which help you draw a final conclusion. After all, sometimes it’s the most minuscule realization that leads you to the strongest conclusion.

Over the next week or so, you keep a close eye on your company’s website and newsletter analytics to see if numbers are in fact declining or if your boss’s concerns were just a fluke.

Critical thinking hinges on objectivity. And, to be objective, you need to base your judgments on the facts – which you collect through research. You’ll lean on your research skills to gather as much information as possible that’s relevant to your problem or situation.

Keep in mind that this isn’t just about the quantity of information – quality matters too. You want to find data and details from a variety of trusted sources to drill past the surface and build a deeper understanding of what’s happening.

You dig into your email and website analytics to identify trends in bounce rates, time on page, conversions, and more. You also review recent newsletters and email promotions to understand what customers have received, look through current customer feedback, and connect with your customer support team to learn what they’re hearing in their conversations with customers.

The critical thinking process is sort of like a treasure hunt – you’ll find some nuggets that are fundamental for your final conclusion and some that might be interesting but aren’t pertinent to the problem at hand.

That’s why you need analytical skills. They’re what help you separate the wheat from the chaff, prioritize information, identify trends or themes, and draw conclusions based on the most relevant and influential facts.

It’s easy to confuse analytical thinking with critical thinking itself, and it’s true there is a lot of overlap between the two. But analytical thinking is just a piece of critical thinking. It focuses strictly on the facts and data, while critical thinking incorporates other factors like emotions, opinions, and experiences.

As you analyze your research, you notice that one specific webpage has contributed to a significant decline in newsletter signups. While all of the other sources have stayed fairly steady with regard to conversions, that one has sharply decreased.

You decide to move on from your other hypotheses about newsletter quality and dig deeper into the analytics.

One of the traps of critical thinking is that it’s easy to feel like you’re never done. There’s always more information you could collect and more rabbit holes you could fall down.

But at some point, you need to accept that you’ve done your due diligence and make a decision about how to move forward. That’s where inference comes in. It’s your ability to look at the evidence and facts available to you and draw an informed conclusion based on those.

When you’re so focused on staying objective and pursuing all possibilities, inference can feel like the antithesis of critical thinking. But ultimately, it’s your inference skills that allow you to move out of the thinking process and onto the action steps.

You dig deeper into the analytics for the page that hasn’t been converting and notice that the sharp drop-off happened around the same time you switched email providers.

After looking more into the backend, you realize that the signup form on that page isn’t correctly connected to your newsletter platform. It seems like anybody who has signed up on that page hasn’t been fed to your email list.

Communication

3 ways to improve your communication skills at work

If and when you identify a solution or answer, you can’t keep it close to the vest. You’ll need to use your communication skills to share your findings with the relevant stakeholders – like your boss, team members, or anybody who needs to be involved in the next steps.

Your analysis skills will come in handy here too, as they’ll help you determine what information other people need to know so you can avoid bogging them down with unnecessary details.

In your next team meeting, you pull up the analytics and show your team the sharp drop-off as well as the missing connection between that page and your email platform. You ask the web team to reinstall and double-check that connection and you also ask a member of the marketing team to draft an apology email to the subscribers who were missed.

Problem-solving

Critical thinking and problem-solving are two more terms that are frequently confused. After all, when you think critically, you’re often doing so with the objective of solving a problem.

The best way to understand how problem-solving and critical thinking differ is to think of problem-solving as much more narrow. You’re focused on finding a solution.

In contrast, you can use critical thinking for a variety of use cases beyond solving a problem – like answering questions or identifying opportunities for improvement. Even so, within the critical thinking process, you’ll flex your problem-solving skills when it comes time to take action.

Once the fix is implemented, you monitor the analytics to see if subscribers continue to increase. If not (or if they increase at a slower rate than you anticipated), you’ll roll out some other tests like changing the CTA language or the placement of the subscribe form on the page.

5 ways to improve your critical thinking skills

Beyond the buzzwords: Why interpersonal skills matter at work

Think critically about critical thinking and you’ll quickly realize that it’s not as instinctive as you’d like it to be. Fortunately, your critical thinking skills are learned competencies and not inherent gifts – and that means you can improve them. Here’s how:

- Practice active listening: Active listening helps you process and understand what other people share. That’s crucial as you aim to be open-minded and inquisitive.

- Ask open-ended questions: If your critical thinking process involves collecting feedback and opinions from others, ask open-ended questions (meaning, questions that can’t be answered with “yes” or “no”). Doing so will give you more valuable information and also prevent your own biases from influencing people’s input.

- Scrutinize your sources: Figuring out what to trust and prioritize is crucial for critical thinking. Boosting your media literacy and asking more questions will help you be more discerning about what to factor in. It’s hard to strike a balance between skepticism and open-mindedness, but approaching information with questions (rather than unquestioning trust) will help you draw better conclusions.

- Play a game: Remember those riddles we mentioned at the beginning? As trivial as they might seem, games and exercises like those can help you boost your critical thinking skills. There are plenty of critical thinking exercises you can do individually or as a team .

- Give yourself time: Research shows that rushed decisions are often regrettable ones. That’s likely because critical thinking takes time – you can’t do it under the wire. So, for big decisions or hairy problems, give yourself enough time and breathing room to work through the process. It’s hard enough to think critically without a countdown ticking in your brain.

Critical thinking really is critical

The ability to think critically is important, but it doesn’t come naturally to most of us. It’s just easier to stick with biases, assumptions, and surface-level information.

But that route often leads you to rash judgments, shaky conclusions, and disappointing decisions. So here’s a conclusion we can draw without any more noodling: Even if it is more demanding on your mental resources, critical thinking is well worth the effort.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee on the Assessment of 21st Century Skills. Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

3 Assessing Interpersonal Skills

The second cluster of skills—broadly termed interpersonal skills—are those required for relating to other people. These sorts of skills have long been recognized as important for success in school and the workplace, said Stephen Fiore, professor at the University of Central Florida, who presented findings from a paper about these skills and how they might be assessed (Salas, Bedwell, and Fiore, 2011). 1 Advice offered by Dale Carnegie in the 1930s to those who wanted to “win friends and influence people,” for example, included the following: be a good listener; don’t criticize, condemn, or complain; and try to see things from the other person’s point of view. These are the same sorts of skills found on lists of 21st century skills today. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills includes numerous interpersonal capacities, such as working creatively with others, communicating clearly, and collaborating with others, among the skills students should learn as they progress from preschool through postsecondary study (see Box 3-1 for the definitions of the relevant skills in the organization’s P-21 Framework).

Interpersonal Capacities in the Partnership for 21st Century Skills Framework. Develop, implement, and communicate new ideas to others effectively Be open and responsive to new and diverse perspectives; incorporate group input and feedback into the work (more...)

It seems clear that these are important skills, yet definitive labels and definitions for the interpersonal skills important for success in schooling and work remain elusive: They have been called social or people skills, social competencies, soft skills, social self-efficacy, and social intelligence, Fiore said (see, e.g., Ferris, Witt, and Hochwarter, 2001 ; Hochwarter et al., 2006 ; Klein et al., 2006 ; Riggio, 1986 ; Schneider, Ackerman, and Kanfer, 1996 ; Sherer et al., 1982 ; Sternberg, 1985 ; Thorndike, 1920 ). The previous National Research Council (NRC) workshop report that offered a preliminary definition of 21st century skills described one broad category of interpersonal skills ( National Research Council, 2010 , p. 3):

- Complex communication/social skills: Skills in processing and interpreting both verbal and nonverbal information from others in order to respond appropriately. A skilled communicator is able to select key pieces of a complex idea to express in words, sounds, and images, in order to build shared understanding ( Levy and Murnane, 2004 ). Skilled communicators negotiate positive outcomes with customers, subordinates, and superiors through social perceptiveness, persuasion, negotiation, instructing, and service orientation ( Peterson et al., 1999 ).

These and other available definitions are not necessarily at odds, but in Fiore’s view, the lack of a single, clear definition reflects a lack of theoretical clarity about what they are, which in turn has hampered progress toward developing assessments of them. Nevertheless, appreciation for the importance of these skills—not just in business settings, but in scientific and technical collaboration, and in both K-12 and postsecondary education settings—has been growing. Researchers have documented benefits these skills confer, Fiore noted. For example, Goleman (1998) found they were twice as important to job performance as general cognitive ability. Sonnentag and Lange (2002) found understanding of cooperation strategies related to higher performance among engineering and software development teams, and Nash and colleagues (2003) showed that collaboration skills were key to successful interdisciplinary research among scientists.

- WHAT ARE INTERPERSONAL SKILLS?

The multiplicity of names for interpersonal skills and ways of conceiving of them reflects the fact that these skills have attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive components, Fiore explained. It is useful to consider 21st century skills in basic categories (e.g., cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal), but it is still true that interpersonal skills draw on many capacities, such as knowledge of social customs and the capacity to solve problems associated with social expectations and interactions. Successful interpersonal behavior involves a continuous correction of social performance based on the reactions of others, and, as Richard Murnane had noted earlier, these are cognitively complex tasks. They also require self-regulation and other capacities that fall into the intrapersonal category (discussed in Chapter 4 ). Interpersonal skills could also be described as a form of “social intelligence,” specifically social perception and social cognition that involve processes such as attention and decoding. Accurate assessment, Fiore explained, may need to address these various facets separately.

The research on interpersonal skills has covered these facets, as researchers who attempted to synthesize it have shown. Fiore described the findings of a study ( Klein, DeRouin, and Salas, 2006 ) that presented a taxonomy of interpersonal skills based on a comprehensive review of the literature. The authors found a variety of ways of measuring and categorizing such skills, as well as ways to link them both to outcomes and to personality traits and other factors that affect them. They concluded that interpersonal effectiveness requires various sorts of competence that derive from experience, instinct, and learning about specific social contexts. They put forward their own definition of interpersonal skills as “goal-directed behaviors, including communication and relationship-building competencies, employed in interpersonal interaction episodes characterized by complex perceptual and cognitive processes, dynamic verbal and non verbal interaction exchanges, diverse roles, motivations, and expectancies” (p. 81).

They also developed a model of interpersonal performance, shown in Figure 3-1 , that illustrates the interactions among the influences, such as personality traits, previous life experiences, and the characteristics of the situation; the basic communication and relationship-building skills the individual uses in the situation; and outcomes for the individual, the group, and the organization. To flesh out this model, the researchers distilled sets of skills for each area, as shown in Table 3-1 .

Model of interpersonal performance. NOTE: Big Five personality traits = openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism; EI = emotional intelligence; IPS = interpersonal skills. SOURCE: Stephen Fiore’s presentation. Klein, (more...)

Taxonomy of Interpersonal Skills.

Fiore explained that because these frameworks focus on behaviors intended to attain particular social goals and draw on both attitudes and cognitive processes, they provide an avenue for exploring what goes into the development of effective interpersonal skills in an individual. They also allow for measurement of specific actions in a way that could be used in selection decisions, performance appraisals, or training. More specifically, Figure 3-1 sets up a way of thinking about these skills in the contexts in which they are used. The implication for assessment is that one would need to conduct the measurement in a suitable, realistic context in order to be able to examine the attitudes, cognitive processes, and behaviors that constitute social skills.

- ASSESSMENT APPROACHES AND ISSUES

One way to assess these skills, Fiore explained, is to look separately at the different components (attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive). For example, as the model in Figure 3-1 indicates, previous life experiences, such as the opportunities an individual has had to engage in successful and unsuccessful social interactions, can be assessed through reports (e.g., personal statements from applicants or letters of recommendation from prior employers). If such narratives are written in response to specific questions about types of interactions, they may provide indications of the degree to which an applicant has particular skills. However, it is likely to be difficult to distinguish clearly between specific social skills and personality traits, knowledge, and cognitive processes. Moreover, Fiore added, such narratives report on past experience and may not accurately portray how one would behave or respond in future experiences.

The research on teamwork (or collaboration)—a much narrower concept than interpersonal skills—has used questionnaires that ask people to rate themselves and also ask for peer ratings of others on dimensions such as communication, leadership, and self-management. For example, Kantrowitz (2005) collected self-report data on two scales: performance standards for various behaviors, and comparison to others in the subjects’ working groups. Loughry, Ohland, and Moore (2007) asked members of work teams in science and technical contexts to rate one another on five general categories: contribution to the team’s work; interaction with teammates; contribution to keeping the team on track; expectations for quality; and possession of relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Another approach, Fiore noted, is to use situational judgment tests (SJTs), which are multiple-choice assessments of possible reactions to hypothetical teamwork situations to assess capacities for conflict resolution, communication, and coordination, as Stevens and Campion (1999) have done. The researchers were able to demonstrate relationships between these results and both peers’ and supervisors’ ratings and to ratings of job performance. They were also highly correlated to employee aptitude test results.

Yet another approach is direct observation of team interactions. By observing directly, researchers can avoid the potential lack of reliability inherent in self- and peer reports, and can also observe the circumstances in which behaviors occur. For example, Taggar and Brown (2001) developed a set of scales related to conflict resolution, collaborative problem solving, and communication on which people could be rated.

Though each of these approaches involve ways of distinguishing specific aspects of behavior, it is still true, Fiore observed, that there is overlap among the constructs—skills or characteristics—to be measured. In his view, it is worth asking whether it is useful to be “reductionist” in parsing these skills. Perhaps more useful, he suggested, might be to look holistically at the interactions among the facets that contribute to these skills, though means of assessing in that way have yet to be determined. He enumerated some of the key challenges in assessing interpersonal skills.

The first concerns the precision, or degree of granularity, with which interpersonal expertise can be measured. Cognitive scientists have provided models of the progression from novice to expert in more concrete skill areas, he noted. In K-12 education contexts, assessment developers have looked for ways to delineate expectations for particular stages that students typically go through as their knowledge and understanding grow more sophisticated. Hoffman (1998) has suggested the value of a similar continuum for interpersonal skills. Inspired by the craft guilds common in Europe during the Middle Ages, Hoffman proposed that assessment developers use the guidelines for novices, journeymen, and master craftsmen, for example, as the basis for operational definitions of developing social expertise. If such a continuum were developed, Fiore noted, it should make it possible to empirically examine questions about whether adults can develop and improve in response to training or other interventions.

Another issue is the importance of the context in which assessments of interpersonal skills are administered. By definition, these skills entail some sort of interaction with other people, but much current testing is done in an individualized way that makes it difficult to standardize. Sophisticated technology, such as computer simulations, or even simpler technology can allow for assessment of people’s interactions in a standardized scenario. For example, Smith-Jentsch and colleagues (1996) developed a simulation of an emergency room waiting room, in which test takers interacted with a video of actors following a script, while others have developed computer avatars that can interact in the context of scripted events. When well executed, Fiore explained, such simulations may be able to elicit emotional responses, allowing for assessment of people’s self-regulatory capacities and other so-called soft skills.

Workshop participants noted the complexity of trying to take the context into account in assessment. For example, one noted both that behaviors may make sense only in light of previous experiences in a particular environment, and that individuals may display very different social skills in one setting (perhaps one in which they are very comfortable) than another (in which they are not comfortable). Another noted that the clinical psychology literature would likely offer productive insights on such issues.

The potential for technologically sophisticated assessments also highlights the evolving nature of social interaction and custom. Generations who have grown up interacting via cell phone, social networking, and tweeting may have different views of social norms than their parents had. For example, Fiore noted, a telephone call demands a response, and many younger people therefore view a call as more intrusive and potentially rude than a text message, which one can respond to at his or her convenience. The challenge for researchers is both to collect data on new kinds of interactions and to consider new ways to link the content of interactions to the mode of communication, in order to follow changes in what constitutes skill at interpersonal interaction. The existing definitions and taxonomies of interpersonal skills, he explained, were developed in the context of interactions that primarily occur face to face, but new technologies foster interactions that do not occur face to face or in a single time window.

In closing, Fiore returned to the conceptual slippage in the terms used to describe interpersonal skills. Noting that the etymological origins of both “cooperation” and “collaboration” point to a shared sense of working together, he explained that the word “coordination” has a different meaning, even though these three terms are often used as if they were synonymous. The word “coordination” captures instead the concepts of ordering and arranging—a key aspect of teamwork. These distinctions, he observed, are a useful reminder that examining the interactions among different facets of interpersonal skills requires clarity about each facet.

- ASSESSMENT EXAMPLES

The workshop included examples of four different types of assessments of interpersonal skills intended for different educational and selection purposes—an online portfolio assessment designed for high school students; an online assessment for community college students; a situational judgment test used to select students for medical school in Belgium; and a collection of assessment center approaches used for employee selection, promotion, and training purposes.

The first example was the portfolio assessment used by the Envision High School in Oakland, California, to assess critical thinking, collaboration, communication, and creativity. At Envision Schools, a project-based learning approach is used that emphasizes the development of deeper learning skills, integration of arts and technology into core subjects, and real-world experience in workplaces. 2 The focus of the curriculum is to prepare students for college, especially those who would be the first in their family to attend college. All students are required to assemble a portfolio in order to graduate. Bob Lenz, cofounder of Envision High School, discussed this online portfolio assessment.

The second example was an online, scenario-based assessment used for community college students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs. The focus of the program is on developing students’ social/communication skills as well as their technical skills. Louise Yarnall, senior research scientist with SRI, made this presentation.

Filip Lievens, professor of psychology at Ghent University in Belgium, described the third example, a situational judgment test designed to assess candidates’ skill in responding to health-related situations that require interpersonal skills. The test is used for high-stakes purposes.

The final presentation was made by Lynn Gracin Collins, chief scientist for SH&A/Fenestra, who discussed a variety of strategies for assessing interpersonal skills in employment settings. She focused on performance-based assessments, most of which involve role-playing activities.

Online Portfolio Assessment of High School Students 3

Bob Lenz described the experience of incorporating in the curriculum and assessing several key interpersonal skills in an urban high school environment. Envision Schools is a program created with corporate and foundation funding to serve disadvantaged high school students. The program consists of four high schools in the San Francisco Bay area that together serve 1,350 primarily low-income students. Sixty-five percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and 70 percent are expected to be the first in their families to graduate from college. Most of the students, Lenz explained, enter the Envision schools at approximately a sixth-grade level in most areas. When they begin the Envision program, most have exceedingly negative feelings about school; as Lenz put it they “hate school and distrust adults.” The program’s mission is not only to address this sentiment about schools, but also to accelerate the students’ academic skills so that they can get into college and to develop the other skills they will need to succeed in life.

Lenz explained that tracking students’ progress after they graduate is an important tool for shaping the school’s approach to instruction. The first classes graduated from the Envision schools 2 years ago. Lenz reported that all of their students meet the requirements to attend a 4-year college in California (as opposed to 37 percent of public high school students statewide), and 94 percent of their graduates enrolled in 2- or 4-year colleges after graduation. At the time of the presentation, most of these students (95 percent) had re-enrolled for the second year of college. Lenz believes the program’s focus on assessment, particularly of 21st century skills, has been key to this success.

The program emphasizes what they call the “three Rs”: rigor, relevance, and relationships. Project-based assignments, group activities, and workplace projects are all activities that incorporate learning of interpersonal skills such as leadership, Lenz explained. Students are also asked to assess themselves regularly. Researchers from the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning, and Equity (SCALE) assisted the Envision staff in developing a College Success Assessment System that is embedded in the curriculum. Students develop portfolios with which they can demonstrate their learning in academic content as well as 21st century skill areas. The students are engaged in three goals: mastery knowledge, application of knowledge, and metacognition.

The components of the portfolio, which is presented at the end of 12th grade, include

- A student-written introduction to the contents

- Examples of “mastery-level” student work (assessed and certified by teachers prior to the presentation)

- Reflective summaries of work completed in five core content areas

- An artifact of and a written reflection on the workplace learning project

- A 21st century skills assessment

Students are also expected to defend their portfolios, and faculty are given professional development to guide the students in this process. Eventually, Lenz explained, the entire portfolio will be archived online.

Lenz showed examples of several student portfolios to demonstrate the ways in which 21st century skills, including interpersonal ones, are woven into both the curriculum and the assessments. In his view, teaching skills such as leadership and collaboration, together with the academic content, and holding the students to high expectations that incorporate these sorts of skills, is the best way to prepare the students to succeed in college, where there may be fewer faculty supports.

STEM Workforce Training Assessments 4

Louise Yarnall turned the conversation to assessment in a community college setting, where the technicians critical to many STEM fields are trained. She noted the most common approach to training for these workers is to engage them in hands-on practice with the technologies they are likely to encounter. This approach builds knowledge of basic technical procedures, but she finds that it does little to develop higher-order cognitive skills or the social skills graduates need to thrive in the workplace.

Yarnall and a colleague have outlined three categories of primary skills that technology employers seek in new hires ( Yarnall and Ostrander, in press ):

Social-Technical

- Translating client needs into technical specifications

- Researching technical information to meet client needs

- Justifying or defending technical approach to client

- Reaching consensus on work team

- Polling work team to determine ideas

- Using tools, languages, and principles of domain

- Generating a product that meets specific technical criteria

- Interpreting problems using principles of domain

In her view, new strategies are needed to incorporate these skills into the community college curriculum. To build students’ technical skills and knowledge, she argued, faculty need to focus more on higher-order thinking and application of knowledge, to press students to demonstrate their competence, and to practice. Cooperative learning opportunities are key to developing social skills and knowledge. For the skills that are both social and technical, students need practice with reflection and feedback opportunities, modeling and scaffolding of desirable approaches, opportunities to see both correct and incorrect examples, and inquiry-based instructional practices.

She described a project she and colleagues, in collaboration with community college faculty, developed that was designed to incorporate this thinking, called the Scenario-Based Learning Project (see Box 3-2 ). This team developed eight workplace scenarios—workplace challenges that were complex enough to require a team response. The students are given a considerable amount of material with which to work. In order to succeed, they would need to figure out how to approach the problem, what they needed, and how to divide up the effort. Students are also asked to reflect on the results of the effort and make presentations about the solutions they have devised. The project begins with a letter from the workplace manager (the instructor plays this role and also provides feedback throughout the process) describing the problem and deliverables that need to be produced. For example, one task asked a team to produce a website for a bicycle club that would need multiple pages and links.

Sample Constructs, Evidence of Learning, and Assessment Task Features for Scenario-Based Learning Projects. Ability to document system requirements using a simplified use case format; ability to address user needs in specifying system requirements. Presented (more...)

Yarnall noted they encountered a lot of resistance to this approach. Community college students are free to drop a class if they do not like the instructor’s approach, and because many instructors are adjunct faculty, their positions are at risk if their classes are unpopular. Scenario-based learning can be risky, she explained, because it can be demanding, but at the same time students sometimes feel unsure that they are learning enough. Instructors also sometimes feel unprepared to manage the teams, give appropriate feedback, and track their students’ progress.

Furthermore, Yarnall continued, while many of the instructors did enjoy developing the projects, the need to incorporate assessment tools into the projects was the least popular aspect of the program. Traditional assessments in these settings tended to measure recall of isolated facts and technical procedures, and often failed to track the development or application of more complex cognitive skills and professional behaviors, Yarnall explained. She and her colleagues proposed some new approaches, based on the theoretical framework known as evidence-centered design. 5 Their goal was to guide the faculty in designing tasks that would elicit the full range of knowledge and skills they wanted to measure, and they turned to what are called reflection frameworks that had been used in other contexts to elicit complex sets of skills ( Herman, Aschbacher, and Winters, 1992 ).

They settled on an interview format, which they called Evidence-Centered Assessment Reflection, to begin to identify the specific skills required in each field, to identify the assessment features that could produce evidence of specific kinds of learning, and then to begin developing specific prompts, stimuli, performance descriptions, and scoring rubrics for the learning outcomes they wanted to measure. The next step was to determine how the assessments would be delivered and how they would be validated. Assessment developers call this process a domain analysis—its purpose was to draw from the instructors a conceptual map of what they were teaching and particularly how social and social-technical skills fit into those domains.

Based on these frameworks, the team developed assessments that asked students, for example, to write justifications for the tools and procedures they intended to use for a particular purpose; rate their teammates’ ability to listen, appreciate different points of view, or reach a consensus; or generate a list of questions they would ask a client to better understand his or her needs. They used what Yarnall described as “coarse, three-level rubrics” to make the scoring easy to implement with sometimes-reluctant faculty, and have generally averaged 79 percent or above in inter-rater agreement.

Yarnall closed with some suggestions for how their experience might be useful for a K-12 context. She noted the process encouraged thinking about how students might apply particular knowledge and skills, and how one might distinguish between high- and low-quality applications. Specifically, the developers were guided to consider what it would look like for a student to use the knowledge or skills successfully—what qualities would stand out and what sorts of products or knowledge would demonstrate a particular level of understanding or awareness.

Assessing Medical Students’ Interpersonal Skills 6

Filip Lievens described a project conducted at Ghent University in Belgium, in which he and colleagues developed a measure of interpersonal skills in a high-stakes context: medical school admissions. The project began with a request from the Belgian government, in 1997, for a measure of these skills that could be used not only to measure the current capacities of physicians, but also to predict the capacities of candidates and thus be useful for selection. Lievens noted the challenge was compounded by the fact the government was motivated by some negative publicity about the selection process for medical school.

One logical approach would have been to use personality testing, often conducted through in-person interviews, but that would have been very difficult to implement with the large numbers of candidates involved, Lievens explained. A paper on another selection procedure, called “low-fidelity simulation” ( Motowidlo et al., 1990 ), suggested an alternative. This approach is also known as a situational judgment test, mentioned above, in which candidates select from a set of possible responses to a situation that is described in writing or presented using video. It is based on the proposition that procedural knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of possible courses of action can be measured, and that the results would be predictive of later behaviors, even if the instrument does not measure the complex facets that go into such choices. A sample item from the Belgian assessment, including a transcription of the scenario and the possible responses, is shown in Box 3-3 . In the early stages of the project, the team used videotaped scenarios, but more recently they have experimented with presenting them through other means, including in written format.

Sample Item from the Situational Judgment Test Used for Admissions to Medical School in Belgium. Situation: Patient: So, this physiotherapy is really going to help me?

Lievens noted a few differences between medical education in Belgium and the United States that influenced decisions about the assessment. In Belgium, prospective doctors must pass an admissions exam at age 18 to be accepted for medical school, which begins at the level that for Americans is the less structured 4-year undergraduate program. The government-run exam is given twice a year to approximately 4,000 students in total, and it has a 30 percent pass rate. Once accepted for medical school, students may choose the university at which they will study—the school must accept all of the students who select it.

The assessment’s other components include 40 items covering knowledge of chemistry, physics, mathematics, and biology and 50 items covering general cognitive ability (verbal, numerical, and figural reasoning). The two interpersonal skills addressed—in 30 items—are building and maintaining relationships and exchanging information.

Lievens described several challenges in the development of the interpersonal component. First, it was not possible to pilot test any items because of a policy that students could not be asked to complete items that did not count toward their scores. In response to both fast-growing numbers of candidates as well as technical glitches with video presentations, the developers decided to present all of the prompts in a paper-and-pencil format. A more serious problem was feedback they received questioning whether each of the test questions had only one correct answer. To address this, the developers introduced a system for determining correct answers through consensus among a group of experts.

Because of the high stakes for this test, they have also encountered problems with maintaining the security of the test items. For instance, Lievens reported that items have appeared for sale on eBay, and they have had problems with students who took the test multiple times simply to learn the content. Developing alternate test forms was one strategy for addressing this problem.

Lievens and his colleagues have conducted a study of the predictive validity of the test in which they collected data on four cohorts of students (a total of 4,538) who took the test and entered medical school ( Lievens and Sackett, 2011 ). They examined GPA and internship performance data for 519 students in the initial group who completed the 7 years required for the full medical curriculum as well as job performance data for 104 students who later became physicians. As might be expected, Lievens observed, the cognitive component of the test was a strong predictor, particularly for the first years of the 7-year course, whereas the interpersonal portion was not useful for predicting GPA (see Figure 3-2 ). However, Figure 3-3 shows this component of the test was much better at predicting the students’ later performance in internships and in their first 9 years as practicing physicians.

Correlations between cognitive and interpersonal components (situational judgment test, or SJT) of the medical school admission test and medical school GPA. SOURCE: Filip Lievens’ presentation. Used with permission.

Correlations between the cognitive and interpersonal components (situational judgment test, or SJT) of the medical school admission test and internship/job performance. SOURCE: Filip Lievens’ presentation. Used with permission.

Lievens also reported the results of a study of the comparability of alternate forms of the test. The researchers compared results for three approaches to developing alternate forms. The approaches differed in the extent to which the characteristics of the situation presented in the items were held constant across the forms. The correlations between scores on the alternate forms ranged from .34 to .68, with the higher correlation occurring for the approach that maintained the most similarities in the characteristics of the items across the forms. The exact details of this study are too complex to present here, and the reader is referred to the full report ( Lievens and Sackett, 2007 ) for a more complete description.

Lievens summarized a few points he has observed about the addition of the interpersonal skills component to the admissions test:

- While cognitive assessments are better at predicting GPA, the assessments of interpersonal skills were superior at predicting performance in internships and on the job.

- Applicants respond favorably to the interpersonal component of the test—Lievens did not claim this component is the reason but noted a sharp increase in the test-taking population.

- Success rates for admitted students have also improved. The percentage of students who successfully passed the requirements for the first academic year increased from 30 percent, prior to having the exam in place, to 80 percent after the exam was installed. While not making a causal claim, Lievens noted that the increased pass rate may be due to the fact that universities have also changed their curricula to place more emphasis on interpersonal skills, especially in the first year.

Assessment Centers 8

Lynn Gracin Collins began by explaining what an assessment center is. She noted the International Congress on Assessment Center Methods describes an assessment center as follows 9 :

a standardized evaluation of behavior based on multiple inputs. Several trained observers and techniques are used. Judgments about behavior are made, in major part, from specifically developed assessment simulations. These judgments are pooled in a meeting among the assessors or by a statistical integration process. In an integration discussion, comprehensive accounts of behavior—and often ratings of it—are pooled. The discussion results in evaluations of the assessees’ performance on the dimensions or other variables that the assessment center is designed to measure.

She emphasized that key aspects of an assessment center are that they are standardized, based on multiple types of input, involve trained observers, and use simulations. Assessment centers had their first industrial application in the United States about 50 years ago at AT&T. Collins said they are widely favored within the business community because, while they have guidelines to ensure they are carried out appropriately, they are also flexible enough to accommodate a variety of purposes. Assessment centers have the potential to provide a wealth of information about how someone performs a task. An important difference with other approaches is that the focus is not on “what would you do” or “what did you do”; instead, the approach involves watching someone actually perform the tasks. They are commonly used for the purpose of (1) selection and promotion, (2) identification of training and development needs, and (3) skill enhancement through simulations.

Collins said participants and management see them as a realistic job preview, and when used in a selection context, prospective employees actually experience what the job would entail. In that regard, Collins commented it is not uncommon for candidates—during the assessment—to “fold up their materials and say if this is what the job is, I don’t want it.” Thus, the tasks themselves can be instructive, useful for experiential learning, and an important selection device.

Some examples of the skills assessed include the following:

- Interpersonal : communication, influencing others, learning from interactions, leadership, teamwork, fostering relationships, conflict management

- Cognitive : problem solving, decision making, innovation, creativity, planning and organizing

- Intrapersonal : adaptability, drive, tolerance for stress, motivation, conscientiousness

To provide a sense of the steps involved in developing assessment center tasks, Collins laid out the general plan for a recent assessment they developed called the Technology Enhanced Assessment Center (TEAC). The steps are shown in Box 3-4 .

Steps involved in Developing the Technology Enhanced Assessment Center. SOURCE: Adapted from presentation by Lynn Gracin Collins. Used with permission.

Assessment centers make use of a variety of types of tasks to simulate the actual work environment. One that Collins described is called an “inbox exercise,” which consists of a virtual desktop showing received e-mail messages (some of which are marked “high priority”), voice messages, and a calendar that includes some appointments for that day. The candidate is observed and tracked as he or she proceeds to deal with the tasks presented through the inbox. The scheduled appointments on the calendar are used for conducting role-playing tasks in which the candidate has to participate in a simulated work interaction. This may involve a phone call, and the assessor/observer plays the role of the person being called. With the scheduled role-plays, the candidate may receive some information about the nature of the appointment in advance so that he or she can prepare for the appointment. There are typically some unscheduled role-playing tasks as well, in order to observe the candidate’s on-the-spot performance. In some instances, the candidate may also be expected to make a presentation. Assessors observe every activity the candidate performs.

Everything the candidate does at the virtual desktop is visible to the assessor(s) in real time, although in a “behind the scenes” manner that is blind to the candidate. The assessor can follow everything the candidate does, including what they do with every message in the inbox, any responses they make, and any entries they make on the calendar.

Following the inbox exercise, all of the observers/assessors complete evaluation forms. The forms are shared, and the ratings are discussed during a debriefing session at which the assessors come to consensus about the candidate. Time is also reserved to provide feedback to the candidate and to identify areas of strengths and weaknesses.

Collins reported that a good deal of information has been collected about the psychometric qualities of assessment centers. She characterized their reliabilities as adequate, with test-retest reliability coefficients in the .70 range. She said a wide range of inter-rater reliabilities have been reported, generally ranging from .50 to .94. The higher inter-rater reliabilities are associated with assessments in which the assessors/raters are well trained and have access to training materials that clearly explain the exercises, the constructs, and the scoring guidelines. Providing behavioral summary scales, which describe the actual behaviors associated with each score level, also help the assessors more accurately interpret the scoring guide.

She also noted considerable information is available about the validity of assessment centers. The most popular validation strategy is to examine evidence of content validity, which means the exercises actually measure the skills and competencies that they are intended to measure. A few studies have examined evidence of criterion-related validity, looking at the relationship between performance on the assessment center exercises and job performance. She reported validities of .41 to .48 for a recent study conducted by her firm ( SH&A/Fenestra, 2007 ) and .43 for a study by Byham (2010) . Her review of the research indicates that assessment center results show incremental validity over personality tests, cognitive tests, and interviews.

One advantage of assessment center methods is they appear not to have adverse impact on minority groups. Collins said research documents that they tend to be unbiased in predictions of job performance. Further, they are viewed by participants as being fairer than other forms of assessment, and they have received positive support from the courts and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Assessment centers can be expensive and time intensive, which is one of the challenges associated with using them. An assessment center in a traditional paradigm (as opposed to a high-tech paradigm) can cost between $2,500 and $10,000 per person. The features that affect cost are the number of assessors, the number of exercises, the length of the assessment, the type of report, and the type of feedback process. They can be logistically difficult to coordinate, depending on whether they use a traditional paradigm in which people need to be brought to a single location as opposed to a technology paradigm where much can be handled remotely and virtually. The typical assessment at a center lasts a full day, which means they are resource intensive and can be difficult to scale up to accommodate a large number of test takers.

Lievens mentioned but did not show data indicating (1) that the predictive validity of the interpersonal items for later performance was actually greater than the predictive validity of the cognitive items for GPA, and (2) that women perform slightly better than men on the interpersonal items.