Random Assignment in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology, random assignment refers to the practice of allocating participants to different experimental groups in a study in a completely unbiased way, ensuring each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group.

In experimental research, random assignment, or random placement, organizes participants from your sample into different groups using randomization.

Random assignment uses chance procedures to ensure that each participant has an equal opportunity of being assigned to either a control or experimental group.

The control group does not receive the treatment in question, whereas the experimental group does receive the treatment.

When using random assignment, neither the researcher nor the participant can choose the group to which the participant is assigned. This ensures that any differences between and within the groups are not systematic at the onset of the study.

In a study to test the success of a weight-loss program, investigators randomly assigned a pool of participants to one of two groups.

Group A participants participated in the weight-loss program for 10 weeks and took a class where they learned about the benefits of healthy eating and exercise.

Group B participants read a 200-page book that explains the benefits of weight loss. The investigator randomly assigned participants to one of the two groups.

The researchers found that those who participated in the program and took the class were more likely to lose weight than those in the other group that received only the book.

Importance

Random assignment ensures that each group in the experiment is identical before applying the independent variable.

In experiments , researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables. Random assignment increases the likelihood that the treatment groups are the same at the onset of a study.

Thus, any changes that result from the independent variable can be assumed to be a result of the treatment of interest. This is particularly important for eliminating sources of bias and strengthening the internal validity of an experiment.

Random assignment is the best method for inferring a causal relationship between a treatment and an outcome.

Random Selection vs. Random Assignment

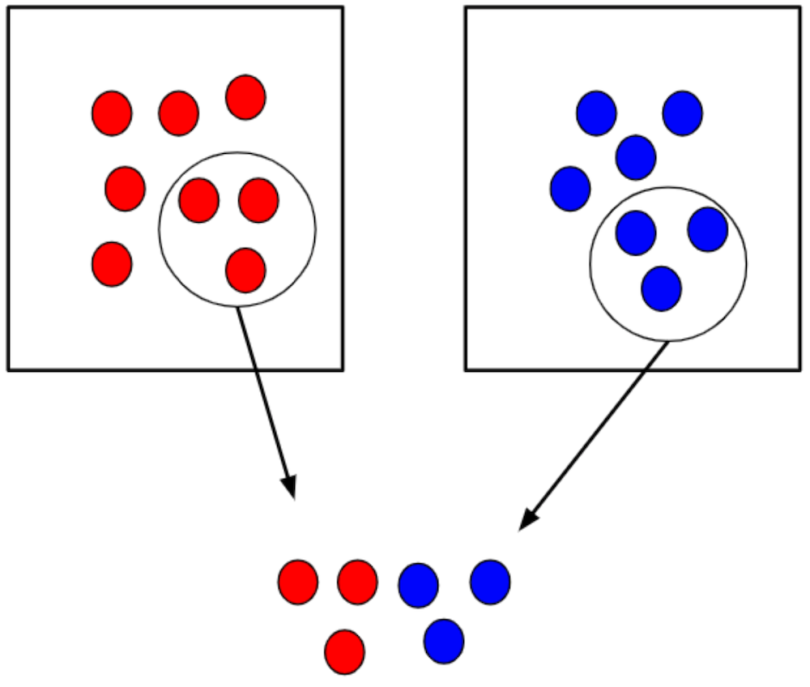

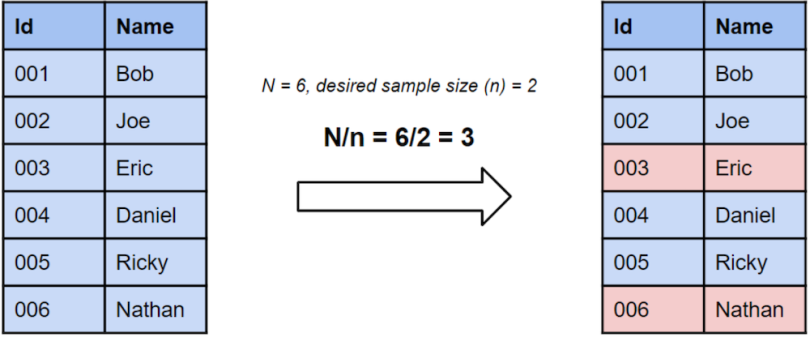

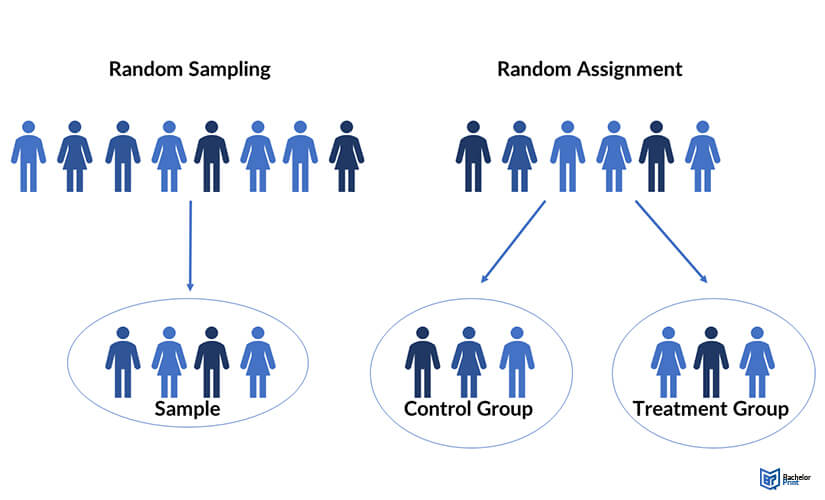

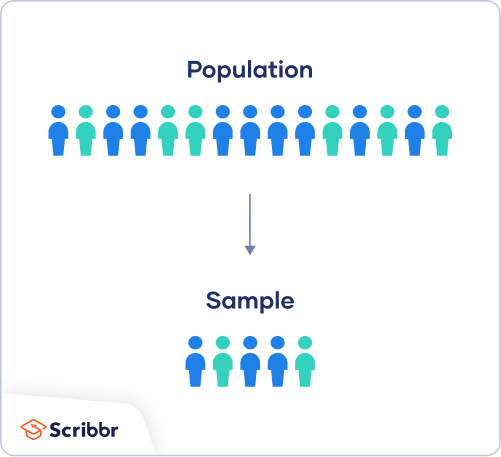

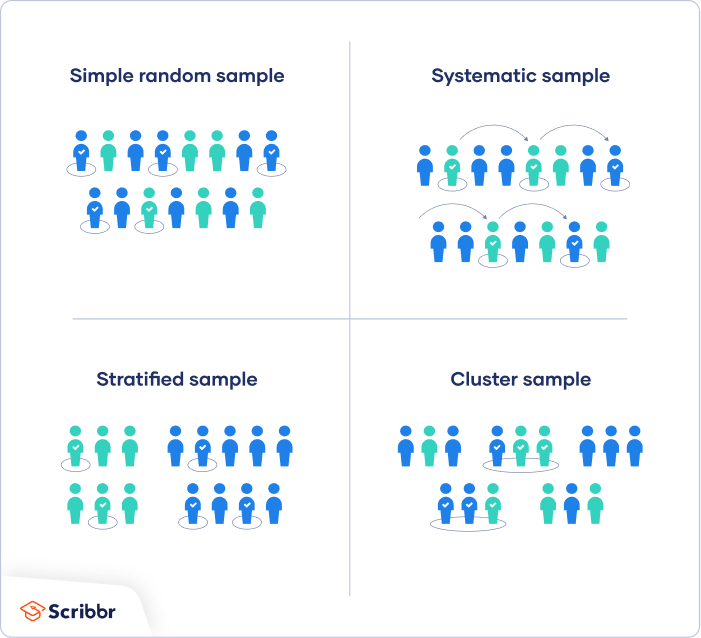

Random selection (also called probability sampling or random sampling) is a way of randomly selecting members of a population to be included in your study.

On the other hand, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample participants into control and treatment groups.

Random selection ensures that everyone in the population has an equal chance of being selected for the study. Once the pool of participants has been chosen, experimenters use random assignment to assign participants into groups.

Random assignment is only used in between-subjects experimental designs, while random selection can be used in a variety of study designs.

Random Assignment vs Random Sampling

Random sampling refers to selecting participants from a population so that each individual has an equal chance of being chosen. This method enhances the representativeness of the sample.

Random assignment, on the other hand, is used in experimental designs once participants are selected. It involves allocating these participants to different experimental groups or conditions randomly.

This helps ensure that any differences in results across groups are due to manipulating the independent variable, not preexisting differences among participants.

When to Use Random Assignment

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design.

In these research designs, researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables.

There is usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the onset of the study.

How to Use Random Assignment

There are a variety of ways to assign participants into study groups randomly. Here are a handful of popular methods:

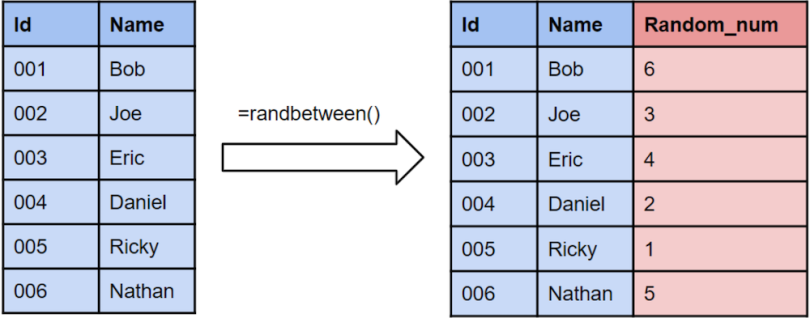

- Random Number Generator : Give each member of the sample a unique number; use a computer program to randomly generate a number from the list for each group.

- Lottery : Give each member of the sample a unique number. Place all numbers in a hat or bucket and draw numbers at random for each group.

- Flipping a Coin : Flip a coin for each participant to decide if they will be in the control group or experimental group (this method can only be used when you have just two groups)

- Roll a Die : For each number on the list, roll a dice to decide which of the groups they will be in. For example, assume that rolling 1, 2, or 3 places them in a control group and rolling 3, 4, 5 lands them in an experimental group.

When is Random Assignment not used?

- When it is not ethically permissible: Randomization is only ethical if the researcher has no evidence that one treatment is superior to the other or that one treatment might have harmful side effects.

- When answering non-causal questions : If the researcher is just interested in predicting the probability of an event, the causal relationship between the variables is not important and observational designs would be more suitable than random assignment.

- When studying the effect of variables that cannot be manipulated: Some risk factors cannot be manipulated and so it would not make any sense to study them in a randomized trial. For example, we cannot randomly assign participants into categories based on age, gender, or genetic factors.

Drawbacks of Random Assignment

While randomization assures an unbiased assignment of participants to groups, it does not guarantee the equality of these groups. There could still be extraneous variables that differ between groups or group differences that arise from chance. Additionally, there is still an element of luck with random assignments.

Thus, researchers can not produce perfectly equal groups for each specific study. Differences between the treatment group and control group might still exist, and the results of a randomized trial may sometimes be wrong, but this is absolutely okay.

Scientific evidence is a long and continuous process, and the groups will tend to be equal in the long run when data is aggregated in a meta-analysis.

Additionally, external validity (i.e., the extent to which the researcher can use the results of the study to generalize to the larger population) is compromised with random assignment.

Random assignment is challenging to implement outside of controlled laboratory conditions and might not represent what would happen in the real world at the population level.

Random assignment can also be more costly than simple observational studies, where an investigator is just observing events without intervening with the population.

Randomization also can be time-consuming and challenging, especially when participants refuse to receive the assigned treatment or do not adhere to recommendations.

What is the difference between random sampling and random assignment?

Random sampling refers to randomly selecting a sample of participants from a population. Random assignment refers to randomly assigning participants to treatment groups from the selected sample.

Does random assignment increase internal validity?

Yes, random assignment ensures that there are no systematic differences between the participants in each group, enhancing the study’s internal validity .

Does random assignment reduce sampling error?

Yes, with random assignment, participants have an equal chance of being assigned to either a control group or an experimental group, resulting in a sample that is, in theory, representative of the population.

Random assignment does not completely eliminate sampling error because a sample only approximates the population from which it is drawn. However, random sampling is a way to minimize sampling errors.

When is random assignment not possible?

Random assignment is not possible when the experimenters cannot control the treatment or independent variable.

For example, if you want to compare how men and women perform on a test, you cannot randomly assign subjects to these groups.

Participants are not randomly assigned to different groups in this study, but instead assigned based on their characteristics.

Does random assignment eliminate confounding variables?

Yes, random assignment eliminates the influence of any confounding variables on the treatment because it distributes them at random among the study groups. Randomization invalidates any relationship between a confounding variable and the treatment.

Why is random assignment of participants to treatment conditions in an experiment used?

Random assignment is used to ensure that all groups are comparable at the start of a study. This allows researchers to conclude that the outcomes of the study can be attributed to the intervention at hand and to rule out alternative explanations for study results.

Further Reading

- Bogomolnaia, A., & Moulin, H. (2001). A new solution to the random assignment problem . Journal of Economic theory , 100 (2), 295-328.

- Krause, M. S., & Howard, K. I. (2003). What random assignment does and does not do . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 59 (7), 751-766.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Statistics and probability

Course: statistics and probability > unit 6.

- Introduction to experiment design

- Matched pairs experiment design

- The language of experiments

- Principles of experiment design

- Experiment designs

Random sampling vs. random assignment (scope of inference)

- (Choice A) Just the residents involved in Hilary's study. A Just the residents involved in Hilary's study.

- (Choice B) All residents in Hilary's town. B All residents in Hilary's town.

- (Choice C) All residents in Hilary's country. C All residents in Hilary's country.

- (Choice A) Yes A Yes

- (Choice B) No B No

- (Choice A) Just the residents in Hilary's study. A Just the residents in Hilary's study.

Want to join the conversation?

Chapter 6: Experimental Research

6.2 experimental design, learning objectives.

- Explain the difference between between-subjects and within-subjects experiments, list some of the pros and cons of each approach, and decide which approach to use to answer a particular research question.

- Define random assignment, distinguish it from random sampling, explain its purpose in experimental research, and use some simple strategies to implement it.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

- Define several types of carryover effect, give examples of each, and explain how counterbalancing helps to deal with them.

In this section, we look at some different ways to design an experiment. The primary distinction we will make is between approaches in which each participant experiences one level of the independent variable and approaches in which each participant experiences all levels of the independent variable. The former are called between-subjects experiments and the latter are called within-subjects experiments.

Between-Subjects Experiments

In a between-subjects experiment , each participant is tested in only one condition. For example, a researcher with a sample of 100 college students might assign half of them to write about a traumatic event and the other half write about a neutral event. Or a researcher with a sample of 60 people with severe agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) might assign 20 of them to receive each of three different treatments for that disorder. It is essential in a between-subjects experiment that the researcher assign participants to conditions so that the different groups are, on average, highly similar to each other. Those in a trauma condition and a neutral condition, for example, should include a similar proportion of men and women, and they should have similar average intelligence quotients (IQs), similar average levels of motivation, similar average numbers of health problems, and so on. This is a matter of controlling these extraneous participant variables across conditions so that they do not become confounding variables.

Random Assignment

The primary way that researchers accomplish this kind of control of extraneous variables across conditions is called random assignment , which means using a random process to decide which participants are tested in which conditions. Do not confuse random assignment with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population, and it is rarely used in psychological research. Random assignment is a method for assigning participants in a sample to the different conditions, and it is an important element of all experimental research in psychology and other fields too.

In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands heads, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands tails, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment.

One problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible. One approach is block randomization . In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. Table 6.2 “Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions” shows such a sequence for assigning nine participants to three conditions. The Research Randomizer website ( http://www.randomizer.org ) will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions. Again, when the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the block randomization.

Table 6.2 Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions

Random assignment is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this is not a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population takes the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design.

Treatment and Control Conditions

Between-subjects experiments are often used to determine whether a treatment works. In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bedsheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008).

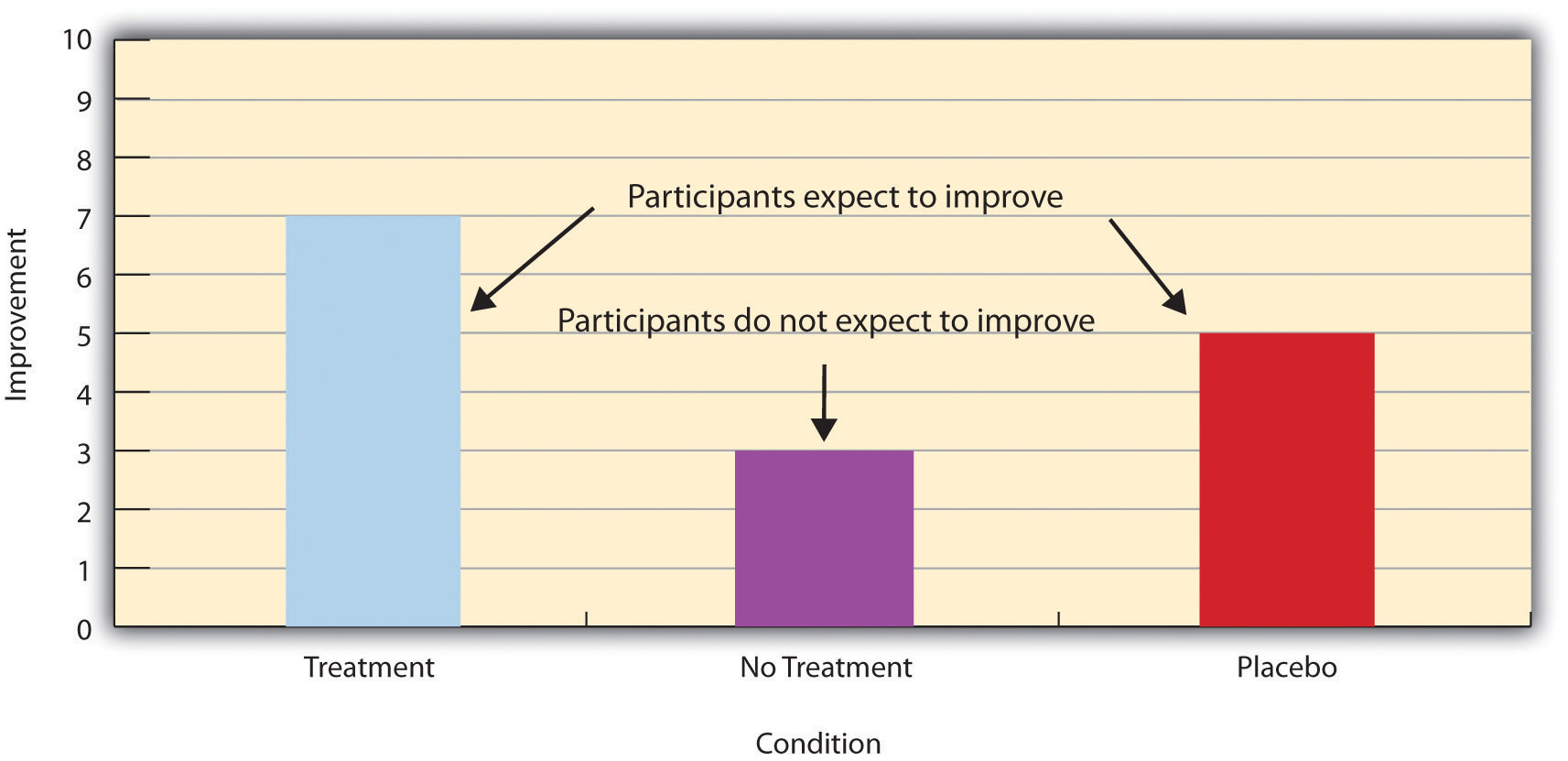

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note 6.28 “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Figure 6.2 Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a waitlist control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?”

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999). There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002). The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

Research has shown that patients with osteoarthritis of the knee who receive a “sham surgery” experience reductions in pain and improvement in knee function similar to those of patients who receive a real surgery.

Army Medicine – Surgery – CC BY 2.0.

Within-Subjects Experiments

In a within-subjects experiment , each participant is tested under all conditions. Consider an experiment on the effect of a defendant’s physical attractiveness on judgments of his guilt. Again, in a between-subjects experiment, one group of participants would be shown an attractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt, and another group of participants would be shown an unattractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt. In a within-subjects experiment, however, the same group of participants would judge the guilt of both an attractive and an unattractive defendant.

The primary advantage of this approach is that it provides maximum control of extraneous participant variables. Participants in all conditions have the same mean IQ, same socioeconomic status, same number of siblings, and so on—because they are the very same people. Within-subjects experiments also make it possible to use statistical procedures that remove the effect of these extraneous participant variables on the dependent variable and therefore make the data less “noisy” and the effect of the independent variable easier to detect. We will look more closely at this idea later in the book.

Carryover Effects and Counterbalancing

The primary disadvantage of within-subjects designs is that they can result in carryover effects. A carryover effect is an effect of being tested in one condition on participants’ behavior in later conditions. One type of carryover effect is a practice effect , where participants perform a task better in later conditions because they have had a chance to practice it. Another type is a fatigue effect , where participants perform a task worse in later conditions because they become tired or bored. Being tested in one condition can also change how participants perceive stimuli or interpret their task in later conditions. This is called a context effect . For example, an average-looking defendant might be judged more harshly when participants have just judged an attractive defendant than when they have just judged an unattractive defendant. Within-subjects experiments also make it easier for participants to guess the hypothesis. For example, a participant who is asked to judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then is asked to judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant is likely to guess that the hypothesis is that defendant attractiveness affects judgments of guilt. This could lead the participant to judge the unattractive defendant more harshly because he thinks this is what he is expected to do. Or it could make participants judge the two defendants similarly in an effort to be “fair.”

Carryover effects can be interesting in their own right. (Does the attractiveness of one person depend on the attractiveness of other people that we have seen recently?) But when they are not the focus of the research, carryover effects can be problematic. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant. If they judge the unattractive defendant more harshly, this might be because of his unattractiveness. But it could be instead that they judge him more harshly because they are becoming bored or tired. In other words, the order of the conditions is a confounding variable. The attractive condition is always the first condition and the unattractive condition the second. Thus any difference between the conditions in terms of the dependent variable could be caused by the order of the conditions and not the independent variable itself.

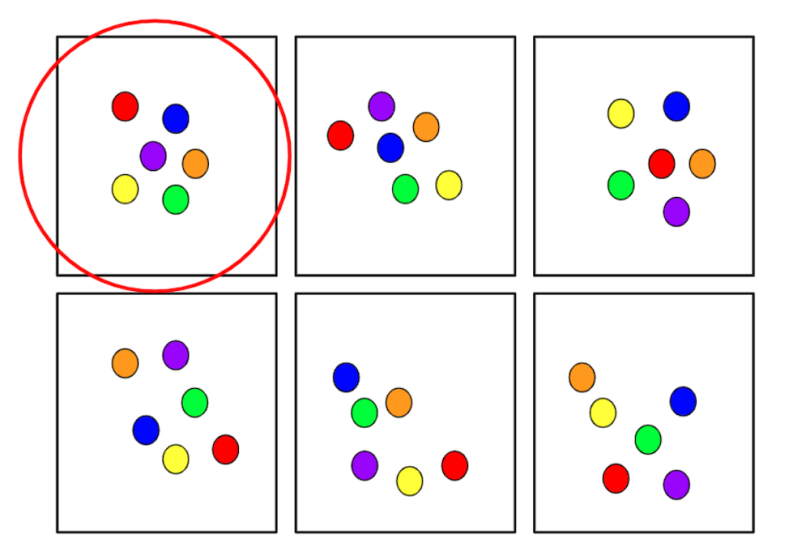

There is a solution to the problem of order effects, however, that can be used in many situations. It is counterbalancing , which means testing different participants in different orders. For example, some participants would be tested in the attractive defendant condition followed by the unattractive defendant condition, and others would be tested in the unattractive condition followed by the attractive condition. With three conditions, there would be six different orders (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, and CBA), so some participants would be tested in each of the six orders. With counterbalancing, participants are assigned to orders randomly, using the techniques we have already discussed. Thus random assignment plays an important role in within-subjects designs just as in between-subjects designs. Here, instead of randomly assigning to conditions, they are randomly assigned to different orders of conditions. In fact, it can safely be said that if a study does not involve random assignment in one form or another, it is not an experiment.

There are two ways to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes. One is that it controls the order of conditions so that it is no longer a confounding variable. Instead of the attractive condition always being first and the unattractive condition always being second, the attractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Likewise, the unattractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Thus any overall difference in the dependent variable between the two conditions cannot have been caused by the order of conditions. A second way to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes is that if there are carryover effects, it makes it possible to detect them. One can analyze the data separately for each order to see whether it had an effect.

When 9 Is “Larger” Than 221

Researcher Michael Birnbaum has argued that the lack of context provided by between-subjects designs is often a bigger problem than the context effects created by within-subjects designs. To demonstrate this, he asked one group of participants to rate how large the number 9 was on a 1-to-10 rating scale and another group to rate how large the number 221 was on the same 1-to-10 rating scale (Birnbaum, 1999). Participants in this between-subjects design gave the number 9 a mean rating of 5.13 and the number 221 a mean rating of 3.10. In other words, they rated 9 as larger than 221! According to Birnbaum, this is because participants spontaneously compared 9 with other one-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively large) and compared 221 with other three-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively small).

Simultaneous Within-Subjects Designs

So far, we have discussed an approach to within-subjects designs in which participants are tested in one condition at a time. There is another approach, however, that is often used when participants make multiple responses in each condition. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of 10 attractive defendants and 10 unattractive defendants. Instead of having people make judgments about all 10 defendants of one type followed by all 10 defendants of the other type, the researcher could present all 20 defendants in a sequence that mixed the two types. The researcher could then compute each participant’s mean rating for each type of defendant. Or imagine an experiment designed to see whether people with social anxiety disorder remember negative adjectives (e.g., “stupid,” “incompetent”) better than positive ones (e.g., “happy,” “productive”). The researcher could have participants study a single list that includes both kinds of words and then have them try to recall as many words as possible. The researcher could then count the number of each type of word that was recalled. There are many ways to determine the order in which the stimuli are presented, but one common way is to generate a different random order for each participant.

Between-Subjects or Within-Subjects?

Almost every experiment can be conducted using either a between-subjects design or a within-subjects design. This means that researchers must choose between the two approaches based on their relative merits for the particular situation.

Between-subjects experiments have the advantage of being conceptually simpler and requiring less testing time per participant. They also avoid carryover effects without the need for counterbalancing. Within-subjects experiments have the advantage of controlling extraneous participant variables, which generally reduces noise in the data and makes it easier to detect a relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

A good rule of thumb, then, is that if it is possible to conduct a within-subjects experiment (with proper counterbalancing) in the time that is available per participant—and you have no serious concerns about carryover effects—this is probably the best option. If a within-subjects design would be difficult or impossible to carry out, then you should consider a between-subjects design instead. For example, if you were testing participants in a doctor’s waiting room or shoppers in line at a grocery store, you might not have enough time to test each participant in all conditions and therefore would opt for a between-subjects design. Or imagine you were trying to reduce people’s level of prejudice by having them interact with someone of another race. A within-subjects design with counterbalancing would require testing some participants in the treatment condition first and then in a control condition. But if the treatment works and reduces people’s level of prejudice, then they would no longer be suitable for testing in the control condition. This is true for many designs that involve a treatment meant to produce long-term change in participants’ behavior (e.g., studies testing the effectiveness of psychotherapy). Clearly, a between-subjects design would be necessary here.

Remember also that using one type of design does not preclude using the other type in a different study. There is no reason that a researcher could not use both a between-subjects design and a within-subjects design to answer the same research question. In fact, professional researchers often do exactly this.

Key Takeaways

- Experiments can be conducted using either between-subjects or within-subjects designs. Deciding which to use in a particular situation requires careful consideration of the pros and cons of each approach.

- Random assignment to conditions in between-subjects experiments or to orders of conditions in within-subjects experiments is a fundamental element of experimental research. Its purpose is to control extraneous variables so that they do not become confounding variables.

- Experimental research on the effectiveness of a treatment requires both a treatment condition and a control condition, which can be a no-treatment control condition, a placebo control condition, or a waitlist control condition. Experimental treatments can also be compared with the best available alternative.

Discussion: For each of the following topics, list the pros and cons of a between-subjects and within-subjects design and decide which would be better.

- You want to test the relative effectiveness of two training programs for running a marathon.

- Using photographs of people as stimuli, you want to see if smiling people are perceived as more intelligent than people who are not smiling.

- In a field experiment, you want to see if the way a panhandler is dressed (neatly vs. sloppily) affects whether or not passersby give him any money.

- You want to see if concrete nouns (e.g., dog ) are recalled better than abstract nouns (e.g., truth ).

- Discussion: Imagine that an experiment shows that participants who receive psychodynamic therapy for a dog phobia improve more than participants in a no-treatment control group. Explain a fundamental problem with this research design and at least two ways that it might be corrected.

Birnbaum, M. H. (1999). How to show that 9 > 221: Collect judgments in a between-subjects design. Psychological Methods, 4 , 243–249.

Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88.

Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590.

Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Research Methods in Psychology. Provided by : University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Located at : http://open.lib.umn.edu/psychologyresearchmethods . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

Statistics Made Easy

Random Selection vs. Random Assignment

Random selection and random assignment are two techniques in statistics that are commonly used, but are commonly confused.

Random selection refers to the process of randomly selecting individuals from a population to be involved in a study.

Random assignment refers to the process of randomly assigning the individuals in a study to either a treatment group or a control group.

You can think of random selection as the process you use to “get” the individuals in a study and you can think of random assignment as what you “do” with those individuals once they’re selected to be part of the study.

The Importance of Random Selection and Random Assignment

When a study uses random selection , it selects individuals from a population using some random process. For example, if some population has 1,000 individuals then we might use a computer to randomly select 100 of those individuals from a database. This means that each individual is equally likely to be selected to be part of the study, which increases the chances that we will obtain a representative sample – a sample that has similar characteristics to the overall population.

By using a representative sample in our study, we’re able to generalize the findings of our study to the population. In statistical terms, this is referred to as having external validity – it’s valid to externalize our findings to the overall population.

When a study uses random assignment , it randomly assigns individuals to either a treatment group or a control group. For example, if we have 100 individuals in a study then we might use a random number generator to randomly assign 50 individuals to a control group and 50 individuals to a treatment group.

By using random assignment, we increase the chances that the two groups will have roughly similar characteristics, which means that any difference we observe between the two groups can be attributed to the treatment. This means the study has internal validity – it’s valid to attribute any differences between the groups to the treatment itself as opposed to differences between the individuals in the groups.

Examples of Random Selection and Random Assignment

It’s possible for a study to use both random selection and random assignment, or just one of these techniques, or neither technique. A strong study is one that uses both techniques.

The following examples show how a study could use both, one, or neither of these techniques, along with the effects of doing so.

Example 1: Using both Random Selection and Random Assignment

Study: Researchers want to know whether a new diet leads to more weight loss than a standard diet in a certain community of 10,000 people. They recruit 100 individuals to be in the study by using a computer to randomly select 100 names from a database. Once they have the 100 individuals, they once again use a computer to randomly assign 50 of the individuals to a control group (e.g. stick with their standard diet) and 50 individuals to a treatment group (e.g. follow the new diet). They record the total weight loss of each individual after one month.

Results: The researchers used random selection to obtain their sample and random assignment when putting individuals in either a treatment or control group. By doing so, they’re able to generalize the findings from the study to the overall population and they’re able to attribute any differences in average weight loss between the two groups to the new diet.

Example 2: Using only Random Selection

Study: Researchers want to know whether a new diet leads to more weight loss than a standard diet in a certain community of 10,000 people. They recruit 100 individuals to be in the study by using a computer to randomly select 100 names from a database. However, they decide to assign individuals to groups based solely on gender. Females are assigned to the control group and males are assigned to the treatment group. They record the total weight loss of each individual after one month.

Results: The researchers used random selection to obtain their sample, but they did not use random assignment when putting individuals in either a treatment or control group. Instead, they used a specific factor – gender – to decide which group to assign individuals to. By doing this, they’re able to generalize the findings from the study to the overall population but they are not able to attribute any differences in average weight loss between the two groups to the new diet. The internal validity of the study has been compromised because the difference in weight loss could actually just be due to gender, rather than the new diet.

Example 3: Using only Random Assignment

Study: Researchers want to know whether a new diet leads to more weight loss than a standard diet in a certain community of 10,000 people. They recruit 100 males athletes to be in the study. Then, they use a computer program to randomly assign 50 of the male athletes to a control group and 50 to the treatment group. They record the total weight loss of each individual after one month.

Results: The researchers did not use random selection to obtain their sample since they specifically chose 100 male athletes. Because of this, their sample is not representative of the overall population so their external validity is compromised – they will not be able to generalize the findings from the study to the overall population. However, they did use random assignment, which means they can attribute any difference in weight loss to the new diet.

Example 4: Using Neither Technique

Study: Researchers want to know whether a new diet leads to more weight loss than a standard diet in a certain community of 10,000 people. They recruit 50 males athletes and 50 female athletes to be in the study. Then, they assign all of the female athletes to the control group and all of the male athletes to the treatment group. They record the total weight loss of each individual after one month.

Results: The researchers did not use random selection to obtain their sample since they specifically chose 100 athletes. Because of this, their sample is not representative of the overall population so their external validity is compromised – they will not be able to generalize the findings from the study to the overall population. Also, they split individuals into groups based on gender rather than using random assignment, which means their internal validity is also compromised – differences in weight loss might be due to gender rather than the diet.

Published by Zach

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Frequently asked questions

What’s the difference between random selection and random assignment.

Random selection, or random sampling , is a way of selecting members of a population for your study’s sample.

In contrast, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample into control and experimental groups.

Random sampling enhances the external validity or generalisability of your results, while random assignment improves the internal validity of your study.

Frequently asked questions: Methodology

Quantitative observations involve measuring or counting something and expressing the result in numerical form, while qualitative observations involve describing something in non-numerical terms, such as its appearance, texture, or color.

To make quantitative observations , you need to use instruments that are capable of measuring the quantity you want to observe. For example, you might use a ruler to measure the length of an object or a thermometer to measure its temperature.

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

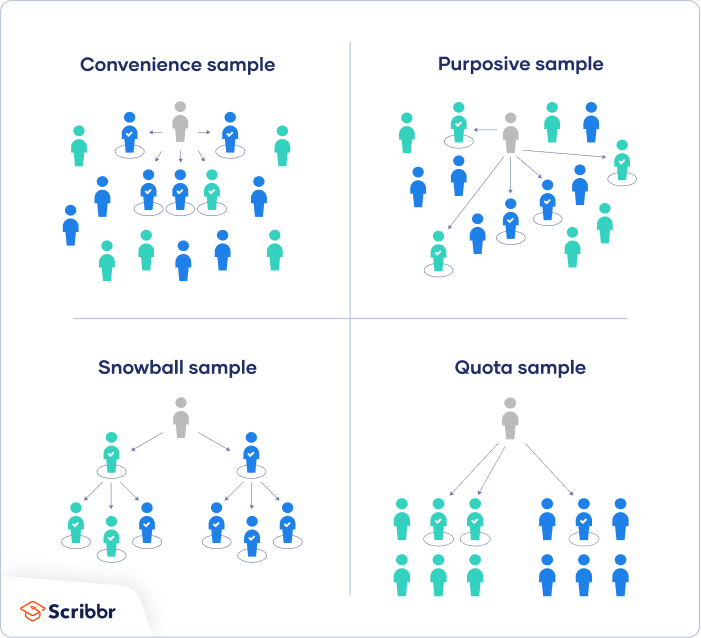

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are predominantly used in non-probability sampling . In purposive sampling and snowball sampling , restrictions apply as to who can be included in the sample .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are typically presented and discussed in the methodology section of your thesis or dissertation .

The purpose of theory-testing mode is to find evidence in order to disprove, refine, or support a theory. As such, generalisability is not the aim of theory-testing mode.

Due to this, the priority of researchers in theory-testing mode is to eliminate alternative causes for relationships between variables . In other words, they prioritise internal validity over external validity , including ecological validity .

Convergent validity shows how much a measure of one construct aligns with other measures of the same or related constructs .

On the other hand, concurrent validity is about how a measure matches up to some known criterion or gold standard, which can be another measure.

Although both types of validity are established by calculating the association or correlation between a test score and another variable , they represent distinct validation methods.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures what it was designed to measure. There are 4 main types of validity :

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the construct it was designed to measure?

- Face validity : Does the test appear to be suitable for its objectives ?

- Content validity : Does the test cover all relevant parts of the construct it aims to measure.

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test measures the outcome it was designed to measure. An outcome can be, for example, the onset of a disease.

Criterion validity consists of two subtypes depending on the time at which the two measures (the criterion and your test) are obtained:

- Concurrent validity is a validation strategy where the the scores of a test and the criterion are obtained at the same time

- Predictive validity is a validation strategy where the criterion variables are measured after the scores of the test

Attrition refers to participants leaving a study. It always happens to some extent – for example, in randomised control trials for medical research.

Differential attrition occurs when attrition or dropout rates differ systematically between the intervention and the control group . As a result, the characteristics of the participants who drop out differ from the characteristics of those who stay in the study. Because of this, study results may be biased .

Criterion validity and construct validity are both types of measurement validity . In other words, they both show you how accurately a method measures something.

While construct validity is the degree to which a test or other measurement method measures what it claims to measure, criterion validity is the degree to which a test can predictively (in the future) or concurrently (in the present) measure something.

Construct validity is often considered the overarching type of measurement validity . You need to have face validity , content validity , and criterion validity in order to achieve construct validity.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity are both subtypes of construct validity . Together, they help you evaluate whether a test measures the concept it was designed to measure.

- Convergent validity indicates whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same or similar construct.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related. This type of validity is also called divergent validity .

You need to assess both in order to demonstrate construct validity. Neither one alone is sufficient for establishing construct validity.

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analysing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

Content validity shows you how accurately a test or other measurement method taps into the various aspects of the specific construct you are researching.

In other words, it helps you answer the question: “does the test measure all aspects of the construct I want to measure?” If it does, then the test has high content validity.

The higher the content validity, the more accurate the measurement of the construct.

If the test fails to include parts of the construct, or irrelevant parts are included, the validity of the instrument is threatened, which brings your results into question.

Construct validity refers to how well a test measures the concept (or construct) it was designed to measure. Assessing construct validity is especially important when you’re researching concepts that can’t be quantified and/or are intangible, like introversion. To ensure construct validity your test should be based on known indicators of introversion ( operationalisation ).

On the other hand, content validity assesses how well the test represents all aspects of the construct. If some aspects are missing or irrelevant parts are included, the test has low content validity.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related

Construct validity has convergent and discriminant subtypes. They assist determine if a test measures the intended notion.

The reproducibility and replicability of a study can be ensured by writing a transparent, detailed method section and using clear, unambiguous language.

Reproducibility and replicability are related terms.

- A successful reproduction shows that the data analyses were conducted in a fair and honest manner.

- A successful replication shows that the reliability of the results is high.

- Reproducing research entails reanalysing the existing data in the same manner.

- Replicating (or repeating ) the research entails reconducting the entire analysis, including the collection of new data .

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method . Unlike probability sampling (which involves some form of random selection ), the initial individuals selected to be studied are the ones who recruit new participants.

Because not every member of the target population has an equal chance of being recruited into the sample, selection in snowball sampling is non-random.

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method , where there is not an equal chance for every member of the population to be included in the sample .

This means that you cannot use inferential statistics and make generalisations – often the goal of quantitative research . As such, a snowball sample is not representative of the target population, and is usually a better fit for qualitative research .

Snowball sampling relies on the use of referrals. Here, the researcher recruits one or more initial participants, who then recruit the next ones.

Participants share similar characteristics and/or know each other. Because of this, not every member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample, giving rise to sampling bias .

Snowball sampling is best used in the following cases:

- If there is no sampling frame available (e.g., people with a rare disease)

- If the population of interest is hard to access or locate (e.g., people experiencing homelessness)

- If the research focuses on a sensitive topic (e.g., extra-marital affairs)

Stratified sampling and quota sampling both involve dividing the population into subgroups and selecting units from each subgroup. The purpose in both cases is to select a representative sample and/or to allow comparisons between subgroups.

The main difference is that in stratified sampling, you draw a random sample from each subgroup ( probability sampling ). In quota sampling you select a predetermined number or proportion of units, in a non-random manner ( non-probability sampling ).

Random sampling or probability sampling is based on random selection. This means that each unit has an equal chance (i.e., equal probability) of being included in the sample.

On the other hand, convenience sampling involves stopping people at random, which means that not everyone has an equal chance of being selected depending on the place, time, or day you are collecting your data.

Convenience sampling and quota sampling are both non-probability sampling methods. They both use non-random criteria like availability, geographical proximity, or expert knowledge to recruit study participants.

However, in convenience sampling, you continue to sample units or cases until you reach the required sample size.

In quota sampling, you first need to divide your population of interest into subgroups (strata) and estimate their proportions (quota) in the population. Then you can start your data collection , using convenience sampling to recruit participants, until the proportions in each subgroup coincide with the estimated proportions in the population.

A sampling frame is a list of every member in the entire population . It is important that the sampling frame is as complete as possible, so that your sample accurately reflects your population.

Stratified and cluster sampling may look similar, but bear in mind that groups created in cluster sampling are heterogeneous , so the individual characteristics in the cluster vary. In contrast, groups created in stratified sampling are homogeneous , as units share characteristics.

Relatedly, in cluster sampling you randomly select entire groups and include all units of each group in your sample. However, in stratified sampling, you select some units of all groups and include them in your sample. In this way, both methods can ensure that your sample is representative of the target population .

When your population is large in size, geographically dispersed, or difficult to contact, it’s necessary to use a sampling method .

This allows you to gather information from a smaller part of the population, i.e. the sample, and make accurate statements by using statistical analysis. A few sampling methods include simple random sampling , convenience sampling , and snowball sampling .

The two main types of social desirability bias are:

- Self-deceptive enhancement (self-deception): The tendency to see oneself in a favorable light without realizing it.

- Impression managemen t (other-deception): The tendency to inflate one’s abilities or achievement in order to make a good impression on other people.

Response bias refers to conditions or factors that take place during the process of responding to surveys, affecting the responses. One type of response bias is social desirability bias .

Demand characteristics are aspects of experiments that may give away the research objective to participants. Social desirability bias occurs when participants automatically try to respond in ways that make them seem likeable in a study, even if it means misrepresenting how they truly feel.

Participants may use demand characteristics to infer social norms or experimenter expectancies and act in socially desirable ways, so you should try to control for demand characteristics wherever possible.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information – for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

- In a single-blind study , only the participants are blinded.

- In a double-blind study , both participants and experimenters are blinded.

- In a triple-blind study , the assignment is hidden not only from participants and experimenters, but also from the researchers analysing the data.

Blinding is important to reduce bias (e.g., observer bias , demand characteristics ) and ensure a study’s internal validity .

If participants know whether they are in a control or treatment group , they may adjust their behaviour in ways that affect the outcome that researchers are trying to measure. If the people administering the treatment are aware of group assignment, they may treat participants differently and thus directly or indirectly influence the final results.

Blinding means hiding who is assigned to the treatment group and who is assigned to the control group in an experiment .

Explanatory research is a research method used to investigate how or why something occurs when only a small amount of information is available pertaining to that topic. It can help you increase your understanding of a given topic.

Explanatory research is used to investigate how or why a phenomenon occurs. Therefore, this type of research is often one of the first stages in the research process , serving as a jumping-off point for future research.

Exploratory research is a methodology approach that explores research questions that have not previously been studied in depth. It is often used when the issue you’re studying is new, or the data collection process is challenging in some way.

Exploratory research is often used when the issue you’re studying is new or when the data collection process is challenging for some reason.

You can use exploratory research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

To implement random assignment , assign a unique number to every member of your study’s sample .

Then, you can use a random number generator or a lottery method to randomly assign each number to a control or experimental group. You can also do so manually, by flipping a coin or rolling a die to randomly assign participants to groups.

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design. In this research design, there’s usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable.

In general, you should always use random assignment in this type of experimental design when it is ethically possible and makes sense for your study topic.

Clean data are valid, accurate, complete, consistent, unique, and uniform. Dirty data include inconsistencies and errors.

Dirty data can come from any part of the research process, including poor research design , inappropriate measurement materials, or flawed data entry.

Data cleaning takes place between data collection and data analyses. But you can use some methods even before collecting data.

For clean data, you should start by designing measures that collect valid data. Data validation at the time of data entry or collection helps you minimize the amount of data cleaning you’ll need to do.

After data collection, you can use data standardisation and data transformation to clean your data. You’ll also deal with any missing values, outliers, and duplicate values.

Data cleaning involves spotting and resolving potential data inconsistencies or errors to improve your data quality. An error is any value (e.g., recorded weight) that doesn’t reflect the true value (e.g., actual weight) of something that’s being measured.

In this process, you review, analyse, detect, modify, or remove ‘dirty’ data to make your dataset ‘clean’. Data cleaning is also called data cleansing or data scrubbing.

Data cleaning is necessary for valid and appropriate analyses. Dirty data contain inconsistencies or errors , but cleaning your data helps you minimise or resolve these.

Without data cleaning, you could end up with a Type I or II error in your conclusion. These types of erroneous conclusions can be practically significant with important consequences, because they lead to misplaced investments or missed opportunities.

Observer bias occurs when a researcher’s expectations, opinions, or prejudices influence what they perceive or record in a study. It usually affects studies when observers are aware of the research aims or hypotheses. This type of research bias is also called detection bias or ascertainment bias .

The observer-expectancy effect occurs when researchers influence the results of their own study through interactions with participants.

Researchers’ own beliefs and expectations about the study results may unintentionally influence participants through demand characteristics .

You can use several tactics to minimise observer bias .

- Use masking (blinding) to hide the purpose of your study from all observers.

- Triangulate your data with different data collection methods or sources.

- Use multiple observers and ensure inter-rater reliability.

- Train your observers to make sure data is consistently recorded between them.

- Standardise your observation procedures to make sure they are structured and clear.

Naturalistic observation is a valuable tool because of its flexibility, external validity , and suitability for topics that can’t be studied in a lab setting.

The downsides of naturalistic observation include its lack of scientific control , ethical considerations , and potential for bias from observers and subjects.

Naturalistic observation is a qualitative research method where you record the behaviours of your research subjects in real-world settings. You avoid interfering or influencing anything in a naturalistic observation.

You can think of naturalistic observation as ‘people watching’ with a purpose.

Closed-ended, or restricted-choice, questions offer respondents a fixed set of choices to select from. These questions are easier to answer quickly.

Open-ended or long-form questions allow respondents to answer in their own words. Because there are no restrictions on their choices, respondents can answer in ways that researchers may not have otherwise considered.

You can organise the questions logically, with a clear progression from simple to complex, or randomly between respondents. A logical flow helps respondents process the questionnaire easier and quicker, but it may lead to bias. Randomisation can minimise the bias from order effects.

Questionnaires can be self-administered or researcher-administered.

Self-administered questionnaires can be delivered online or in paper-and-pen formats, in person or by post. All questions are standardised so that all respondents receive the same questions with identical wording.

Researcher-administered questionnaires are interviews that take place by phone, in person, or online between researchers and respondents. You can gain deeper insights by clarifying questions for respondents or asking follow-up questions.

In a controlled experiment , all extraneous variables are held constant so that they can’t influence the results. Controlled experiments require:

- A control group that receives a standard treatment, a fake treatment, or no treatment

- Random assignment of participants to ensure the groups are equivalent

Depending on your study topic, there are various other methods of controlling variables .

An experimental group, also known as a treatment group, receives the treatment whose effect researchers wish to study, whereas a control group does not. They should be identical in all other ways.

A true experiment (aka a controlled experiment) always includes at least one control group that doesn’t receive the experimental treatment.

However, some experiments use a within-subjects design to test treatments without a control group. In these designs, you usually compare one group’s outcomes before and after a treatment (instead of comparing outcomes between different groups).

For strong internal validity , it’s usually best to include a control group if possible. Without a control group, it’s harder to be certain that the outcome was caused by the experimental treatment and not by other variables.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Cross-sectional studies are less expensive and time-consuming than many other types of study. They can provide useful insights into a population’s characteristics and identify correlations for further research.

Sometimes only cross-sectional data are available for analysis; other times your research question may only require a cross-sectional study to answer it.

Cross-sectional studies cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship or analyse behaviour over a period of time. To investigate cause and effect, you need to do a longitudinal study or an experimental study .

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

Longitudinal studies are better to establish the correct sequence of events, identify changes over time, and provide insight into cause-and-effect relationships, but they also tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than other types of studies.

The 1970 British Cohort Study , which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study .

Longitudinal studies can last anywhere from weeks to decades, although they tend to be at least a year long.

A correlation reflects the strength and/or direction of the association between two or more variables.

- A positive correlation means that both variables change in the same direction.

- A negative correlation means that the variables change in opposite directions.

- A zero correlation means there’s no relationship between the variables.

A correlational research design investigates relationships between two variables (or more) without the researcher controlling or manipulating any of them. It’s a non-experimental type of quantitative research .

A correlation coefficient is a single number that describes the strength and direction of the relationship between your variables.

Different types of correlation coefficients might be appropriate for your data based on their levels of measurement and distributions . The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r ) is commonly used to assess a linear relationship between two quantitative variables.

Controlled experiments establish causality, whereas correlational studies only show associations between variables.

- In an experimental design , you manipulate an independent variable and measure its effect on a dependent variable. Other variables are controlled so they can’t impact the results.

- In a correlational design , you measure variables without manipulating any of them. You can test whether your variables change together, but you can’t be sure that one variable caused a change in another.

In general, correlational research is high in external validity while experimental research is high in internal validity .

The third variable and directionality problems are two main reasons why correlation isn’t causation .

The third variable problem means that a confounding variable affects both variables to make them seem causally related when they are not.

The directionality problem is when two variables correlate and might actually have a causal relationship, but it’s impossible to conclude which variable causes changes in the other.

As a rule of thumb, questions related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups . Take your time formulating strong questions, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can bias your responses.

Overall, your focus group questions should be:

- Open-ended and flexible

- Impossible to answer with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (questions that start with ‘why’ or ‘how’ are often best)

- Unambiguous, getting straight to the point while still stimulating discussion

- Unbiased and neutral

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favourably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias in research can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behaviour accordingly.

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of four types of interviews .

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.