- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 11 July 2020

Obsessive compulsive disorder in very young children – a case series from a specialized outpatient clinic

- Veronika Brezinka ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2192-3093 1 ,

- Veronika Mailänder 1 &

- Susanne Walitza 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 20 , Article number: 366 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic condition often associated with severe disruptions of family functioning, impairment of peer relationships and academic performance. Mean age of onset of juvenile OCD is 10.3 years; however, reports on young children with OCD show that the disorder can manifest itself at an earlier age. Both an earlier age of onset and a longer duration of illness have been associated with increased persistence of OCD. There seems to be difficulty for health professionals to recognize and diagnose OCD in young children appropriately, which in turn may prolong the interval between help seeking and receiving an adequate diagnosis and treatment. The objective of this study is to enhance knowledge about the clinical presentation, diagnosis and possible treatment of OCD in very young children.

Case presentation

We describe a prospective 6 month follow-up of five cases of OCD in very young children (between 4 and 5 years old). At the moment of first presentation, all children were so severely impaired that attendance of compulsory Kindergarten was uncertain. Parents were deeply involved in accommodating their child’s rituals. Because of the children’s young age, medication was not indicated. Therefore, a minimal CBT intervention for parents was offered, mainly focusing on reducing family accommodation. Parents were asked to bring video tapes of critical situations that were watched together. They were coached to reduce family accommodation for OCD, while enhancing praise and reward for adequate behaviors of the child. CY-BOCS scores at the beginning and after 3 months show an impressive decline in OCD severity that remained stable after 6 months. At 3 months follow-up, all children were able to attend Kindergarten daily, and at 6 months follow-up, every child was admitted to the next level / class.

Conclusions

Disseminating knowledge about the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of early OCD may shorten the long delay between first OCD symptoms and disease-specific treatment that is reported as main predictor for persistent OCD.

Peer Review reports

Paediatric obsessive compulsive disorder [ 1 ] is a chronic condition with lifetime prevalence estimates ranging from 0.25 [ 2 ] to 2–3% [ 3 ]. OCD is often associated with severe disruptions of family functioning [ 4 ] and impairment of peer relationships as well as academic performance [ 5 ]. Mean age of onset of early onset OCD is 10.3 years, with a range from 7.5 to 12.5 years [ 6 ] or at an average of 11 years [ 7 ]. However, OCD can manifest itself also at a very early age - in a sample of 58 children, mean age of onset was 4.95 years [ 8 ], and in a study from Turkey, OCD is described in children as young as two and a half years [ 9 ]. According to different epidemiological surveys the prevalence of subclinical OC syndromes was estimated between 7 and 25%, and already very common at the age of 11 years [ 10 ].

Understanding the phenomenology of OCD in young children is important because both an earlier age of onset and a longer duration of illness have been associated with increased persistence of OCD [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. One of the main predictors for persistent OCD is duration of illness at assessment, which underlines that early recognition and treatment of the disorder are crucial to prevent chronicity [ 10 , 14 , 15 ]. OCD in very young children can be so severe that it has to be treated in an inpatient-clinic [ 16 ]. This might be prevented if the disorder were diagnosed and treated earlier.

In order to disseminate knowledge about early childhood OCD, detailed descriptions of its phenomenology are necessary to enable clinicians to recognize and assess the disorder in time. Yet, studies on this young population are scarce and differ in the definition of what is described as ‘very young’. For example, 292 treatment seeking youth with OCD were divided into a younger group (3–9 years old) and an older group (10–18 years old) [ 17 ]. While overall OCD severity did not differ between groups, younger children exhibited poorer insight, increased incidence of hoarding compulsions, and higher rates of separation anxiety and social fears than older youth. It is not clear how many very young children (between 3 and 5 years old) were included in this study. Skriner et al. [ 18 ] investigated characteristics of 127 young children (from 5 to 8) enrolled in a pilot sample of the POTS Jr. Study. These young children revealed moderate to severe OCD symptoms, high levels of impairment and significant comorbidity, providing further evidence that symptom severity in young children with OCD is similar to that observed in older samples. To our knowledge, the only European studies describing OCD in very young children on a detailed, phenotypic level are a single-case study of a 4 year old girl [ 16 ] and a report from Turkey on 25 children under 6 years with OCD [ 9 ]. Subjects were fifteen boys and ten girls between 2 and 5 years old. Mean age of onset of OCD symptoms was 3 years, with some OCD symptoms appearing as early as 18 months of age. All subjects had at least one comorbid disorder; the most frequent comorbidity was an anxiety disorder, and boys exhibited more comorbid diagnoses than girls. In 68% of the subjects, at least one parent received a lifetime OCD diagnosis. The study reports no further information on follow-up or treatment of these young patients.

In comparison to other mental disorders, duration of untreated illness in obsessive compulsive disorder is one of the longest [ 19 ]. One reason may be that obsessive-compulsive symptoms in young children are mistaken as a normal developmental phase [ 20 ]. Parents as well as professionals not experienced with OCD may tend to ‘watch and wait’ instead of asking for referral to a specialist, thus contributing to the long delay between symptom onset and assessment / treatment [ 10 ]. This might ameliorate if health professionals become more familiar with the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of the disorder in the very young. The purpose of this study is to provide a detailed description of the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of OCD in five very young children.

We describe a prospective 6 month follow-up of five cases of OCD in very young children (between 4 and 5 years old) who were referred to the OCD Outpatient Treatment Unit of a Psychiatric University Hospital. Three patients were directly referred by their parents, one by the paediatrician and one by another specialist. Parents and child were offered a first session within 1 week of referral. An experienced clinician (V.B.) globally assessed comorbidity, intelligence and functioning, and a CY-BOCS was administered with the parents.

Instruments

To assess OCD severity in youth, the Children Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale CY-BOCS [ 21 ] is regarded as the gold standard, with excellent inter-rater and test-retest reliability as well as construct validity [ 21 , 22 ]. The CY-BOCS has been validated in very young children by obtaining information from the parent. As in the clinical interview Y-BOCS for adults, severity of obsessions and compulsions are assessed separately. If both obsessions and compulsions are reported, a score of 16 is regarded as the cut-off for clinically meaningful OCD. If only compulsions are reported, Lewin et al. [ 23 ] suggest a cut-off score of 8. In their CY-BOCS classification, a score between 5 and 13 corresponds to mild symptoms / little functional impairment or a Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) of 2. A score between 14 and 24 corresponds to moderate symptoms / functioning with effort or a CGI-S of 3. Generally, it is recommended to obtain information from both child and parents. However, in case of the very young patients presented here, CY-BOCS scores were exclusively obtained from the parents. The parents of all five children reported not being familiar with any obsessions their child might have. In accordance with previous recommendations [ 23 ], a cut-off point of 8 for clinically meaningful OCD was used.

Patient vignettes

Patient 1 is a 4 year old girl, a single child living with both parents. She had never been separated an entire day from her mother. At the nursery, she suffered from separation anxiety for months. Parents reported that the girl had insisted on rituals already at the age of two. In the evening, she ‚had‘ to take her toys into bed and had got up several times crying because she ‚had to‘ pick up more toys. In the morning, only she ‚had the right‘ to open the apartment door. When dressing in the morning, she ‚had‘ to be ready before the parents. Only she was allowed to flush the toilet, even if it concerned toilet use of the parents. Moreover, only she ‘had the right’ to switch on the light, and this had to be with ten fingers at the same time. If she did not succeed, she got extremely upset and pressed the light button again and again until she was satisfied. The girl was not able to throw away garbage and kept packaging waste in a separate box. In the evening, she had to tidy her room for a long time until everything was ‚right‘. Whenever her routine was changed, she protested by crying, shouting and yelling at her parents. Moreover, she insisted on repeating routines if there had been a ‚mistake‘. In order to avoid conflict, both parents adapted their behavior to their daughter’s desires. In the first assessment with the parents, her score on the CY-BOCS was 15, implying clinically meaningful OCD. Psychiatric family history revealed that the mother had suffered from severe separation anxiety as a child and the father from severe night mares. Both parents described themselves as healthy adults.

Patient 2 is a four and a half year old boy, the younger of two brothers. He was reported to have been very oppositional since the age of two. Since the age of three, he insisted on a specific ritual when flushing the toilet – he had to pronounce several distinct sentences and then to run away quickly. Some months later he developed a complicated fare-well ritual and insisted on every family member using exactly the sentences he wanted to hear. If one of these words changed, he started to shout and threw himself on the floor. After a short time, he insisted on unknown people like the cashier at the supermarket to use the same words when saying good-bye.Moreover, he insisted that objects and meals had to be put back to the same place as before in case they had been moved. When walking outside, he had to count his steps and had to start this over and over again. In the morning, he determined where his mother had to stand and how her face had to look when saying good-bye. In order to avoid conflict, parents and brother had deeply accommodated their behavior to his whims. On the CY-BOCS, patient 2 reached a score of 15, which is equivalent to clinically meaningful OCD. Neither his father nor his mother reported any psychiatric disorder in past or present.

Patient 3 is a 4 year old boy referred because of possible OCD. Since the age of three, he had insisted on things going his way. When this was not the case, he threw a temper tantrum and demanded that time should be turned back. If, for example, he had cut a piece of bread from the loaf and was not satisfied with its form, he insisted that the piece should be ‘glued’ to the loaf again. Since he entered Kindergarten at the age of four, his behavior became more severe. If he was not satisfied with a certain routine like, for example, dressing in the morning, he demanded that the entire family had to undress and go to bed again, that objects had to lie at the same place as before or that the clock had to be turned back. In order to avoid conflict, the parents had repeatedly consented to his wishes. His behavior was judged as problematic at Kindergarten, because he demanded certain situations to be repeated or ‚played back‘. When the teacher refused to do that, the boy once run away furiously. On the CY-BOCS, patient 3 reached a score of 15. The mother described herself as being rather anxious (but not in treatment), the father himself as not suffering from any psychiatric symptoms. However, his mother had suffered from such severe OCD when he was a child that she had undergone inpatient treatment several times. This was also the reason why the parents had asked for referral to a specialist for the symptoms of their son.

Patient 4 is a 5 year old girl, the eldest of three siblings. Since the age of two, she was only able to wear certain clothes. For months, she refused to wear any shoes besides Espadrilles; she was unable to wear jeans and could only wear one certain pair of leggings. Wearing warm or thicker garments was extremely difficult, leading to numerous conflicts with her mother in winter. Socks had to have the same height, stockings had to be thin, and slips slack. When dressing in the morning, she regularly got angry and despaired and engaged in severe conflicts with her mother; dressing took a long time, whereas she had to be in Kindergarten on time. Her compulsions with clothes seemed to influence her social behavior as well; she had been watching other children at the playground for 40 min and did not participate because her winter coat did not ‚feel right‘. She started to join peers only when she was allowed to pull the coat off. She also had to dry herself excessively after peeing and was reported to be perfectionist in drawing, cleaning or tidying. Her CY-BOCS score was 15, equivalent to clinically meaningful OCD. Both parents described themselves as not suffering from any psychiatric problem in past or present. However, the grandmother on the mother’s side was reported to have had similar compulsions when she was a child.

Patient 5 was a four and a half year old girl referred because of early OCD. She had one elder brother and lived with both parents. At the age of 1 year, patient 5 was diagnosed with a benign brain tumor (astrocytoma). The tumor had been removed for 90% by surgery; the remaining tumor was treated with chemotherapy. The first chemotherapy at the age of 3 years was reasonably well tolerated. Shortly thereafter, the girl developed just-right-compulsions concerning her shoes. When the second chemotherapy (with a different drug) was started at the age of four, compulsions increased so dramatically that she was referred to our outpatient clinic by the treating oncologist. She insisted on her shoes being closed very tightly, her socks and underwear being put on according to a certain ritual, and her belt being closed so tightly that her father had to punch an additional hole. She refused to wear slack or new clothes and was not able to leave the toilet after peeing because ‘something might still come’; she used large amounts of toilet paper and complained that she wasn’t dry yet. She also insisted on straightening the blanket of her bed many times. She was described by her mother as extremely stressed, impatient and irritable; she woke up every night and insisted to go to the toilet, from where she would come back only after intense cleaning rituals. In the morning, she frequently threw a severe temper tantrum, including hitting and scratching the mother, staying naked in the bathroom and refusing to get dressed because clothes were not fitting ‚just right‘or were not tight enough. Shortly after the start of the second chemotherapy, the girl had entered Kindergarten which was in a different language than the family language. Moreover, her mother had just taken up a new job and had to make a trip of several days during the first month. Although the mother gave up her job after the dramatic increase in OCD severity, the girl’s symptoms did not change. As an association between chemotherapy and the increase in OCD symptoms could not be excluded, the treating oncologist decided to stop chemotherapy 2 weeks after patient 5 was presented with OCD at our department. At the moment of presentation, she arrived at Kindergarten too late daily, after long scenes of crying and shouting, or refused to go altogether. She reached a score of 20 on the CY-BOCS, the highest score of the five children presented here. Her father described himself as free of any psychiatric symptoms in past or present. Her mother had been extremely socially anxious as a child.

None of the siblings of the children described above was reported to show any psychiatric symptoms in past or present (Table 1 ).

The five cases described above show a broad range of OCD symptomatology in young children. Besides Just-Right compulsions concerning clothes, compulsive behavior on the toilet was reported such as having to pee frequently, having to dry oneself over and over again as well as rituals concerning flushing. Other symptoms were pronouncing certain words or phrases compulsively, insisting on a ‘perfect’ action and claiming that time or situations must be played back like a video or DVD if the action or situation were not ‘perfect enough’. The patients described here have in common that parents were already much involved in the process of family accommodation. For example, the parents of patient 3 had consented several times to undress and go to bed again in order to ‘play back’ certain situations; they had also consented turning back the clock in the house. The parents of patient 2 had accommodated his complicated fare-well ritual, thus having to rush to work in the morning themselves. However, all parents were smart enough not just to indulge their child’s behavior, but to seek professional advice.

Treatment recommendations

Practice Parameters and guidelines for the assessment and treatment of OCD in older children and adolescents recommend cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) as first line treatment for mild to moderate cases, and medication in addition to CBT for moderate to severe OCD [ 24 , 25 ]. However, there is a lack of treatment studies including young children with OCD [ 26 ]. A case series with seven children between the age of 3 and 8 years diagnosed with OCD describes an intervention adapted to this young age group. Treatment emphasized reducing family accommodation and anxiety-enhancing parenting behaviors while enhancing problem solving skills of the parents [ 27 ]. A much larger randomized clinical trial for 127 young children (5 to 8 years of age) with OCD showed family-based CBT superior to a relaxation protocol for this age group [ 14 ]. Despite these advances in treatment for early childhood OCD, availability of CBT for paediatric OCD in the community is scarce due to workforce limitations and regional limitations in paediatric OCD expertise [ 28 ]. This is certainly not only true for the US, but for most European countries as well.

When discussing treatment of OCD in young children, the topic of family accommodation is of utmost importance. Family accommodation, also referred to as a ‘hallmark of early childhood OCD’ [ 15 ] means that parents of children with OCD tend to accommodate and even participate in rituals of the affected child. In order to avoid temper tantrums and aggressive behavior of the child, parents often adapt daily routines by engaging in child rituals or facilitating OCD by allowing extra time, purchasing special products or adapting family rules and organisation to OCD [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Although driven by empathy for and compassion with the child, family accommodation is reported to be detrimental because it further reinforces OCD symptoms and avoidance behavior, thus enhancing stress and anxiety [ 4 , 32 ].

Parent-oriented CBT intervention

At the moment of first presentation, the five children were so severely impaired by their OCD that attendance of (compulsory) Kindergarten was uncertain. All parents reported being utterly worried and stressed by their child’s symptoms and the associated conflicts in the family. However, no single family wanted an in-patient treatment of their child, and because of the children’s young age, medication was not indicated. Some families lived far away from our clinic and / or had to take care of young siblings.

Therefore, a CBT-intervention was offered to the parents, mainly focusing on reducing family accommodation. This approach is in line with current treatment recommendations to aggressively target family accommodation in children with OCD [ 15 ]. Parents and child were seen together in a first session. The following sessions were done with the parents only, who were encouraged to bring video tapes of critical situations. The scenes were watched together and parents were coached to reduce family accommodation for OCD, while enhancing praise and reward for adequate behaviors of the child. Parents were also encouraged to use ignoring and time-out for problematic behaviors. As some families lived far away and had to take care of young siblings as well, telephone sessions were offered as an alternative whenever parents felt the need for it. Moreover, parents were prompted to facilitate developmental tasks of their child such as attending Kindergarten regularly, or building friendships with peers. The minimal number of treatment sessions was four and the maximal number ten, with a median of six sessions.

Three of the five children (patients 3, 4 and 5) were raised in a different language at home than the one spoken at Kindergarten. This can be interpreted as an additional stressor for the child, possibly enhancing OCD symptoms. Instead of expecting their child to learn the foreign language mainly by ‚trial and error‘, parents were encouraged to speak this language at home themselves, to praise their child for progress in language skills and to facilitate playdates with children native in the foreign language.

Three and six months after intake, assessment of OCD-severity by means of the CY-BOCS was repeated. Table 2 shows an impressive decline in OCD-severity after 3 months that remained stable after 6 months. At 3 months follow-up, all children were able to attend Kindergarten daily, and at 6 months follow-up, every child was admitted to the next level of Kindergarten or, in the case of patient 4, to school.

We report on five children of 4 and 5 years with very early onset OCD who were presented at a University Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. These children are ‚early starters‘with regard to OCD. As underlined in a recent consensus statement [ 10 ], delayed initiation of treatment is seen as an important aspect of the overall burden of OCD (see also [ 19 ]). In our small sample, a CBT-based parent-oriented intervention targeting mainly family accommodation led to a significant decline in CY-BOCS scores after 3 months that was maintained at 6 months. At 3 months, all children were able to attend Kindergarten daily, and at 6 months, every child was admitted to the next grade. This can be seen as an encouraging result, as it allowed the children to continue their developmental milestones without disruptions, like staying at home for a long period or following an inpatient treatment that would have demanded high expenses and probably led to separation problems at this young age. Moreover, the reduction on CY-BOCS scores was reached without medication. The number of sessions of the CBT-based intervention with the parents varied between four and ten sessions, depending on the need of the family. Families stayed in touch with the therapist during the 6 month period and knew they could get an appointment quickly when needed.

A possible objection to these results might be the question of differential diagnosis. Couldn’t the problematic behaviors described merely be classified as benign childhood rituals that would change automatically with time? As described in the patient vignettes, the five children were so severely impaired by their OCD that attendance of Kindergarten – a developmental milestone – was uncertain. Moreover, parents were extremely worried and stressed by their child’s symptoms and associated family conflicts. In our view, it would have been a professional mistake to judge these symptoms as benign rituals not worthy of diagnosis or disorder-specific treatment. One possible, but rare and debated cause of OCD are streptococcal infections, often referred to as PANS [ 33 ]. However, in none of the cases parents reported an abrupt and sudden onset of OCD symptoms after an infection. Instead, symptoms seem to have developed gradually over a period of several months or even years. In the case of patient 5 with the astrocytoma, first just-right compulsions appeared at the age of three (after the first chemotherapy), and were followed by more severe compulsions at the age of four, when – within a period of 6 weeks – a new chemotherapy was started, the mother took up a new job and the patient entered Kindergarten. Diagnosing the severe compulsions of patient 5 as, for example, adjustment disorder due to her medical condition would not have delivered a disorder-specific treatment encouraging parents to reduce their accommodation. This might have led to even more family accommodation and to more severe OCD symptoms in the young girl. Last but not least, a possible objection might be that the behaviors described were stereotypies. However, stereotypies are defined as repetitive or ritualistic movements, postures or utterances and are often associated with an autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disability. The careful intake with the children revealed no indication for any of these disorders.

Data reported here have several limitations. The children did not undergo intelligence testing; their reactions and behavior during the first session, as well as their acceptance and graduation at Kindergarten were assumed as sufficient to judge them as average intelligent. Comorbidities were assessed according to clinical impression and parents’ reports. The CBT treatment was based on our clinical expertise as a specialized OCD outpatient clinic. It included parent-oriented CBT elements, but did not have a fixed protocol and was adjusted individually to the needs of every family. Last but not least, no control group of young patients without an intervention was included.

Conclusions and clinical implications

We described a prospective 6 month follow-up of five cases of OCD in very young children. At the moment of first presentation, all children were so severely impaired that attendance of Kindergarten was uncertain. Parents were deeply involved in accommodating their child’s rituals. Because of the children’s young age, medication was not indicated. Therefore, a minimal CBT intervention for parents was offered, mainly focusing on reducing family accommodation. CY-BOCS scores at the beginning and after 3 months show an impressive decline in OCD severity that remained stable after 6 months. At 3 months follow-up, all children were able to attend Kindergarten daily, and at 6 months follow-up, every child had been admitted to the next grade. OCD is known to be a chronic condition. Therefore, in spite of treatment success, relapse might occur. However, as our treatment approach mainly targeted family accommodation, parents will hopefully react with less accommodation, should a new episode of OCD occur. Moreover, parents stay in touch with the outpatient clinic and can call when needed.

The clinical implications of our findings are that clinicians should not hesitate to think of OCD in a young child when obsessive-compulsive symptoms are reported. The assessment of the disorder should include the CY-BOCS, which has been validated in very young children by obtaining information from the parent. If CY-BOCS scores are clinically meaningful (for young children, a score above 8), a parent-based treatment targeting family accommodation should be offered.

By disseminating knowledge about the clinical presentation, assessment and treatment of early childhood OCD, it should be possible to shorten the long delay between first symptoms of OCD and disease-specific treatment that is reported as main predictor for persistent OCD. Early recognition and treatment of OCD are crucial to prevent chronicity [ 14 , 15 ]. As children and adolescents with OCD have a heightened risk for clinically significant psychiatric and psychosocial problems as adults, intervening early offers an important opportunity to prevent the development of long-standing problem behaviors [ 10 , 19 ].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

Obsessive compulsive behavior

Child Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Pediatric OCD Treatment Study PT. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969–76.

Article Google Scholar

Heyman I, Fombonne E, Simmons H, Ford T, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the British nationwide survey of child mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15:178–84.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Zohar AH. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;8:445–60.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Renshaw KD, Steketee GS, Chambless DL. Involving family members in the treatment of OCD. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;34(3):164–75.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barrett P, Farrell L, Dadds M, Boulter N. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: long-term follow-up and predictors of outcome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):1005–14.

Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29:353–70.

Taylor S. Early versus late onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence for distinct subtypes. Clin Psychol Review. 2011;31:1083–100.

Garcia A, Freeman J, Himle M, Berman N, Ogata AK, Ng J, et al. Phenomenology of early childhood onset obsessive compulsive disorder. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2009;31:104–11.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Coskun M, Zoroglu S, Ozturk M. Phenomenology, psychiatric comorbidity and family history in referred preschool children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6(1):36.

Fineberg NA, Dell'Osso B, Albert U, Maina G, Geller DA, Carmi L, et al. Early intervention for obsessive compulsive disorder: an expert consensus statement. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.02.002 .

Micali N, Heyman I, Perez M, Hilton K, Nakatani E, Turner C, et al. Long-term outcomes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: follow-up of 142 children and adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:128–34.

Zellmann H, Jans T, Irblich B, Hemminger U, Reinecker H, Sauer C, et al. Children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorders. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2009;37(3):173–82.

Stewart SE, Geller DA, Jenike M, Pauls D, Shaw D, Mullin B, et al. Long-term outcome of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis and qualitative review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(1):4–13.

Freeman J, Sapyta JJ, Garcia A, Compton S, Khanna M, Flessner C, et al. Family-based Treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder Treatment Study for young children (POTS Jr) - a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):689–98.

Lewin AB, Park JM, Jones AM, Crawford EA, De Nadai AS, Menzel J, et al. Family-based exposure and response prevention therapy for preschool-aged children with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2014;56:30–8.

Renner T, Walitza S. Schwere frühkindliche Zwangsstörung - Kasuistik eines 4-jährigen Mädchens. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2006;34:287–93.

Selles RR, Storch EA, Lewin AB. Variations in symptom prevalence and clinical correlates in younger versus older youth with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2014;45:666–74.

Skriner LC, Freeman J, Garcia A, Benito K, Sapyta J, Franklin M. Characteristics of young children with obsessive–compulsive disorder: baseline features from the POTS Jr. Sample Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2016;47:83–93.

Walitza S, van Ameringen M, Geller D. Early detection and intervention for obsessive-compulsive disorder in childhood and adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30376-1 .

Nakatani E, Krebs G, Micali N, Turner C, Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D. Children with very early onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: clinical features and treatment outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(12):1261–8.

Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M. Children's Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–52.

Freeman J, Flessner C, Garcia A. The Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: reliability and validity for use among 5 to 8 year olds with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39:877–83.

Lewin AB, Piacentini J, De Nadai AS, Jones AM, Peris TS, Geffken GR, et al. Defining clinical severity in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(2):679–84.

AACAP. Practice parameter for the assessment and Treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98–113.

NICE. Treatment options for children and young people with obsessive-compulsive disorder or body dysmorphic disorder. In: Excellence NIfHaC, 2019.

Google Scholar

Freeman J, Choate-Summers ML, Moore PS, Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Leonard HL, et al. Cognitive behavioral Treatment for young children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):337–43.

Ginsburg GS, Burstein M, Becker KD, Drake KL. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder in young children: an intervention model and case series. Child Family Behav Ther. 2011;33(2):97–122.

Comer JS, Furr JM, Kerns CE, Miguel E, Coxe S, Elkins RM, et al. Internet-delivered, family-based treatment for early-onset OCD: a pilot randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(2):178–86.

Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, Goodman WK, et al. Family accommodation in Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(2):207–16.

Brezinka V. Zwangsstörungen bei Kindern. Die Rolle der Angehörigen. Schweizer Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie & Neurologie. 2015;15(4):4–6.

Lebowitz ER. Treatment of extreme family accommodation in a youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Storch EA, Lewin AB, editors. Clinical handbook of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. New York: Springer; 2016. p. 321–35.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lebowitz ER. Parent-based treatment for childhood and adolescent OCD. J Obsessive-Compulsive Related Dis. 2013;2(4):425–31.

Chang K, Frankovich J, Cooperstock M, Cunningham M, Latimer ME, Murphy TK, et al. Clinical evaluation of youth with Pediatric acute onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). Recommendations from the 2013 PANS consensus conference. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25:3–13.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

no funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, University of Zurich, Neumünsterallee 3, 8032, Zurich, Switzerland

Veronika Brezinka, Veronika Mailänder & Susanne Walitza

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

V.B. conducted the diagnostic and therapeutic sessions and wrote the manuscript. V.M. was responsible for medical supervision and revised the manuscript. S.W. supervised the OCD treatment and research overall, applied for ethics approval and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Veronika Brezinka .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

the study was approved by the Kantonale Ethikkommission Zürich, July 22nd, 2019.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

V.B. and V.M. declare that they have no competing interests. S.W. has received royalties from Thieme, Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, Springer, Beltz in the last 5 years. Her work was supported in the last 5 years by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), diff. EU FP7s, HSM Hochspezialisierte Medizin of the Kanton Zurich, Switzerland, Bfarm Germany, ZInEP, Hartmann Müller Stiftung, Olga Mayenfisch, Gertrud Thalmann, Vontobel-, Unisciencia and Erika Schwarz Fonds. Outside professional activities and interests are declared under the link of the University of Zurich www.uzh.ch/prof/ssl-dir/interessenbindungen/client/web/

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Brezinka, V., Mailänder, V. & Walitza, S. Obsessive compulsive disorder in very young children – a case series from a specialized outpatient clinic. BMC Psychiatry 20 , 366 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02780-0

Download citation

Received : 02 March 2020

Accepted : 05 July 2020

Published : 11 July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02780-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

- Early childhood

- Family accommodation

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

CLINICAL CASE STUDY article

A clinical case study of the use of ecological momentary assessment in obsessive compulsive disorder.

- Brain, Behaviour and Mental Health Research Group, School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

Accurate assessment of obsessions and compulsions is a crucial step in treatment planning for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). In this clinical case study, we sought to determine if the use of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) could provide additional symptom information beyond that captured during standard assessment of OCD. We studied three adults diagnosed with OCD and compared the number and types of obsessions and compulsions captured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) compared to EMA. Following completion of the Y-BOCS interview, participants then recorded their OCD symptoms into a digital voice recorder across a 12-h period in reply to randomly sent mobile phone SMS prompts. The EMA approach yielded a lower number of symptoms of obsessions and compulsions than the Y-BOCS but produced additional types of obsessions and compulsions not previously identified by the Y-BOCS. We conclude that the EMA-OCD procedure may represent a worthy addition to the suite of assessment tools used when working with clients who have OCD. Further research with larger samples is required to strengthen this conclusion.

Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a disabling anxiety disorder characterized by upsetting, unwanted cognitions (obsessions) and intense and time consuming recurrent compulsions ( American Psychiatric Association, 2000 ). The idiosyncratic nature of the symptoms of OCD ( Whittal et al., 2010 ) represents a challenge to completing accurate and comprehensive assessments, which if not achieved, can have a deleterious effect on the provision of effective treatment for the disorder ( Kim et al., 1989 ; Taylor, 1995 ; Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ; Deacon and Abramowitz, 2005 ).

Accurately assessing the full range of symptoms of OCD requires reliable and psychometrically sound diagnostic instruments and measures ( Taylor, 1995 , 1998 ; Rees, 2009 ) alongside the standard clinical interview. Although the most commonly used psychometric instrument for assessing OCD, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) ( Goodman et al., 1989a , b ), has acceptable reliability and convergent validity, it has been criticized by Taylor (1995) for weak discriminant validity. Taylor also highlighted that it remains susceptible to administration variance, relies on client memory recall, and is time consuming to administer. As with all measures completed retrospectively, selective memory biases affect the type of information reported by clients about their symptoms ( Clark, 1988 ; Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ; Stone et al., 2004 ). Glass and Arnkoff (1997 , p. 912) have summarized several disadvantages of structured inventories; first, they contain prototypical statements which may fail to capture the idiosyncratic nature of the client's actual thoughts; second, they can be affected by post-hoc reappraisals of what clients feel, as the data is subject to memory recall biases; and finally they may fail to adequately capture the client's internal dialog due to the limitations of the best fit question structure.

Discrepancies have been reported between data collected in the client's natural environment ( in situ ) and those based on the client's later recall ( de Beurs et al., 1992 ; Marks and Hemsley, 1999 ; Stone et al., 2004) . Such discrepancies may be further affected by factors such as the complexity and diversity of obsessions and compulsions, not to mention the ego-dystonic nature of many OCD clients' obsessional thoughts. It seems likely that clients with distressing ego-dystonic obsessions, for example, those involving sexual, aggressive, and/or religious themes may experience a heightened level of discomfort in reporting their obsessions in a face to face assessment with a clinician, thus reducing their willingness to accurately report ( Taylor, 1995 ; Newth and Rachman, 2001 ; Grant et al., 2006 ; Rees, 2009 ). This may contribute to an underreporting of these obsessions, and hence an inaccurate understanding and a restriction of the clinician's ability to adequately treat the client ( Grant et al., 2006 ; Rachman, 2007 ).

Exposure and response prevention, cognitive therapy, and pharmacological interventions have been shown to be effective in the treatment of OCD ( Abramowitz, 1997 , 2001 ; Foa and Franklin, 2001 ; Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ; Fisher and Wells, 2008 ; Chosak et al., 2009 ). Self-monitoring is a useful therapeutic technique that provides essential information to assist in the development of exposure hierarchies and behavioral experiments used in cognitive therapy ( Tolin, 2009 ). Clients typically observe and record their experiences of target behaviors, including triggers, environmental events surrounding those experiences, and their response to those experiences ( Cormier and Nurius, 2003 ). Such self-monitoring can be used to both assist assessment and/or as an intervention. Cormier and Nurius (2003) explained that the mere act of observing and monitoring one's own behavior and experiences can produce change. As people observe themselves and collect data about what they observe, their behavior may be influenced.

A form of self-monitoring and alternative to the typical clinic-based assessment of OCD is the use of sampling from the client's real-world experiences, a procedure known as Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) ( Schwartz and Stone, 1998 ; Stone and Shiffman, 1994 , 2002 ). EMA does not rely on measurements using memory recall within the clinical setting, but rather allows for collection of information about the client's experiences in their natural setting, potentially improving the assessment's ecological validity ( Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ). In situ sampling techniques have been successfully used in psychology, psychiatry, and occupational therapy (for a more detailed account see research by Morgan et al., 1990 ; de Beurs et al., 1992 ; Kamarack et al., 1998 ; Litt et al., 1998 ; Kimhy et al., 2006 ; Gloster et al., 2008 ; Putnam and McSweeney, 2008 ; Trull et al., 2008 ). Generally it is agreed that EMA offers broader assessment within the client's natural environment, as it includes random time sampling of the client's experience, recording of events associated with the client's experience, and self-reports regarding the client's behaviors and physiological experiences ( Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ). Because this assessment method accesses information about the client's situation, the difficulties of memory distortions like recall bias are reduced ( Schwartz and Stone, 1998 ; Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ).

Given that accurate assessment of obsessions and compulsions is a critical aspect of treatment planning and that reliance on self-report and clinician interview has some known limitations, the purpose of this study was to investigate the utility of EMA as a potential adjunct to the conventional assessment of OCD. Specifically, we sought to compare the amount and type of information regarding obsessions and compulsions collected via EMA vs. standard assessment using the gold-standard symptom interview for OCD. As this is a pilot clinical case study, we offer the following tentative hypothesis: (1) EMA will yield additional types of obsessions and compulsions not captured by the Y-BOCS.

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited through clients presenting to the OCD clinic at Curtin University. They were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) ( First et al., 1997 ). Inclusion in the study was based on receiving a primary diagnosis of OCD, and a Y-BOCS ( Goodman et al., 1989a , b ) score of more than 16, placing their OCD symptom severity within the clinical range ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ). Participants were excluded if they presented with current suicidal ideation, psychotic disorders, apparent organic causes of anxiety, were severely depressed, or if they had an intellectual disability. One potential participant was excluded post evaluation despite meeting the inclusion criteria, as she did not own a mobile phone, and reported having “blackouts” throughout the day. The three participants all had OCD symptoms in the “severe” range according to the YBOCS. In order to ensure that participants remain anonymous, pseudonyms have been used.

Participant A

Mary was a 28-year-old female who lived with her husband and small dog. She reported that for approximately 1 year she had been experiencing distressing intrusive thoughts in relation to harming her loved ones, herself, or her dog; for example, by stabbing, electrocution, or breaking the dog's neck. Mary said that she also had reoccurring thoughts and images that her husband or other family members might die. She reported engaging in some rituals, for example straightening pillows and rearranging tea-towels; but mostly reported using “safety nets” in response to her unwanted cognitions; for example ensuring that she was not alone (to prevent self-harm); avoidance and removal of feared object; extensive reassurance seeking from family members. According to the Y-BOCS measure, Mary scored a subtotal of 14 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 18 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 32, classifying her symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

Mary reported that her OCD first occurred after her grandmother passed away about 6 years ago. She explained they had a very close relationship, she said she found it “unbearably distressing” to visit her while she was dying. Mary reported that on one occasion whilst in a coma, her grandmother sat up and gasped, which she found extremely frightening and still remembers it in vivid detail. She reported that she experienced thoughts that her grandmother was in pain and was going “into the unknown, to a scary place.” Mary reported feeling afraid of death and that if someone “even closer” to her died she “would not be able to cope” and that she would “lose control completely.” She stated that her biggest fear was that her husband, mother or father might die. Mary reported that she has been on various anti-depressants for about 10 years. She stated that recently her psychiatrist prescribed Solian (an antipsychotic) which she tried, and found was very effective at blocking out the intrusive thoughts. However, she ceased taking the medication due to nausea.

Participant B

John was a 5-year-old man who lived with his wife and adult son. He reported a long history of distressing intrusive thoughts, and compulsive behaviors. They are summarized in three ways. First, those that relate to religious obsessions, specifically the occult and satanic experiences/fear of being “possessed.” He reported responding to these unwanted cognitions by either washing his hands to cleanse himself; using more than six pieces of toilet paper to wipe after defecating to prevent the devil entering him via his anus; or looking for the number “555,” which represents “God. This is good.” John reported that failing to act in these ways would risk causing harm to his wife and son. Second, those that relate to checking compulsions, specifically when driving, and also checking that doors are locked—which he reported doing 4–12 times per night. He reported that if he thought he heard a “bump” when driving he would have to turn back to check he had not run anyone over, or would seek reassurance from his son or wife if they were passengers in the car with him. He stated that he feared that harm would come to his wife and son if he didn't perform these checks. Third, John said that he arranged shoes so that they were “lined up” and that the clothes in the cupboard were in the “right order.” He also reported the need to compulsively clean his son's bedroom, and that he wouldn't feel “right” until he had done so. According to the Y-BOCS measure, John scored a subtotal of 13 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 15 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 28, classifying his symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

John reported that his symptoms have been present for at least the last 29 years. He reported that his OCD first occurred after he had a “break-down” and tried to commit suicide by stabbing himself in the stomach before he turned 25 years of age. In the years leading up to this, John reported two poignant experiences which appear relevant to the development of his symptoms; he reported being involved in the euthanizing of two dogs whilst working as a Ranger's assistant; and that when he was young, he and his girlfriend at the time had a pregnancy termination. John reported feeling that these were “blasphemous” acts, and posed the question “Is God punishing me?” John reported that he had been on several different anti-depressants for about 19 years, with varying degrees of success and side-effects. He reported that he had seen a psychiatrist every 6 weeks for “many years” and finds being able to talk helpful.

Participant C

Paul was a 35-year-old man, who reported distressing intrusive thoughts and images in relation to harm coming to others as a consequence of him not checking that he had done what he is “supposed to do.” For example, he was concerned that someone at work would be harmed if he forgot to adequately cover shifts on the roster (something he is responsible for); or when a client of the service he coordinates was recently given a stereo, Paul reported that he feared that harm would come to the client if he didn't correctly check it to see if it was faulty, something he felt responsible to do.

Paul reported that only his partner knew of his difficulties. He stated that he did not allow his anxiety to interfere too much with his occupational functioning; however he did report that the main reason he does not practice in his profession is because of his OCD. According to the Y-BOCS measure, Paul scored a subtotal of 12 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 13 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 25, classifying his symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

Paul reported that his intrusive thoughts have “always been there.” He explained that one of the first clear memories he has of them, was when he was seven years old and he saw the film the “The Omen.” He reported remembering checking his head for the numbers “666.” Additionally, he reported remembering that he was concerned for his mother's safety. He reported that he had never taken medication for his OCD. He stated that he saw two therapists when he lived in the UK at an OCD center in London approximately 18 months ago. Paul said that he did not gain much from the first therapist, but believes that second therapist assisted him to look at his cognitions as “just thoughts.”

Materials and Methods

All screening of participants, interviewing and assessment, as well as administration of the study, was conducted by the first author, who was a provisionally registered psychologist undergoing postgraduate training at the time of the research, and was supervised by the second author, an experienced OCD clinician and academic. Potential participants were recruited from the Curtin OCD clinic. They were screened via telephone to ascertain their suitability for the study. A face-to-face assessment session using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First et al., 1997 ) was conducted to determine a primary OCD diagnosis, followed by the administration of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) interview and checklist ( Goodman et al., 1989b ) to identify the participants' obsessions and compulsions and their symptom severity. The Y-BOCS is the most widely used scale for OCD symptoms assessment and is considered by researchers to be the “gold standard” measure for symptom severity ( Deacon and Abramowitz, 2005 ; Himle and Franklin, 2009 ). It consists of two parts; a checklist of prelisted types of obsessions, usually endorsed by the clinician based on disclosures made by the client; and the severity scale which requires the client to rate the severity of their experience by answering the questions based on their recall. Goodman et al. (1989) note that the Y-BOCS has shown adequate interrater agreement, internal consistency, and validity.

Suitable participants then attended a second session where they signed consent forms and were given instructions about the study procedure. During the data collection using the Ecological Momentary Assessment data (EMA-OCD), participants used an Olympus WS-110 digital voice recorder to record their experiences throughout a 12 h period. Participants used their existing mobile phones to receive prompts via the mobile phone Short Message Service (SMS) to record their responses to the research questions. All three participants were then provided with an envelope containing the Olympus WS-100 digital voice recorder, a spare battery, and the participant prompt questions (see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Prompt questions .

Participants were asked to turn their mobile phones on during the data collection day by 10 am, ready to receive their SMS prompts. The researcher manually sent SMS prompts to the participants at random intervals; at least every 2 h (across 1 day, from 10 am to 10 pm), for a minimum of 10 data entries in keeping with research using EMA procedures (see, Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ); asking them to complete their responses to all four questions as details on the EMA-OCD Participant Questions Sheet. Participants were instructed not to respond to the SMS prompts if driving, and were asked to respond as quickly as possible to the prompts. Data was then downloaded from the voice recorder to the researcher's computer, and transcribed. During this process all identifying details were removed. During the debrief session open-ended questions were used to gather as much information as possible regarding the participant's experiences of the study, and suggestions for improvements. During the data collection day the researcher completed a journal to record his observations and reflections related to the use of the EMA. At the completion of the EMD-OCD data collection, each of the participants was provided with a debrief session (Mary by phone, and John and Paul, face to face). The debrief session focused on their experiences of the research and use of the digital voice recorder; and provided the opportunity for them to discuss anything else that arose they wished to tell the researcher. As stated above, the data was downloaded and transcribed by the first author. The Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion categories were used as a framework to compare the data generated from the EMA-OCD procedure. After the complete de-identified data set was tabled, it was provided to a second person who was an expert in OCD for verification of categories. In the case of any discrepancies agreement was reached via consensus.

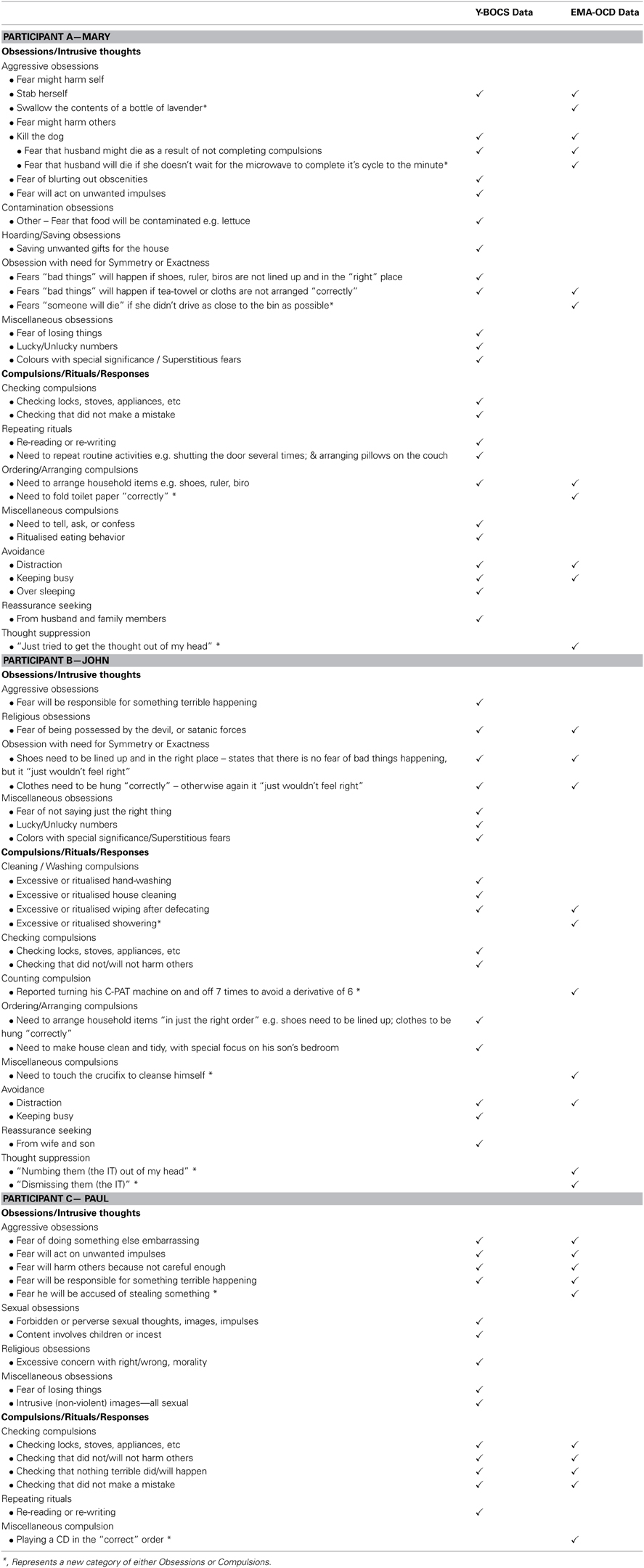

Number of reported symptoms

Table 2 provides a summary of the frequency and type of symptoms recorded during both the face-to-face session, which will be referred to as the Y-BOCS data and the EMA-OCD phase for the study, which will be referred to as the EMA–OCD data. As can be seen when comparing the data contained in the two columns, there are variations between the Y-BOCS data and the EMA-OCD data. All three participants reported more categories of both obsessions and compulsions in the Y-BOCS data, compared to that reported in the EMA-OCD data.

Table 2. Summary by participant of Y-BOCS data and EMA-OCD data .

Mary reported experiencing five categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and six categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data she reported experiencing two categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and three categories of Y-BOCS Compulsions. John reported experiencing four categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and five categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data he reported experiencing two categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and five categories of Y-BOCS Compulsions. Paul reported experiencing four categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and two categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data he reported experiencing one category of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and two categories of Compulsions.

Comparison of content of symptoms

Both Mary and Paul reported previously unidentified Obsessions or intrusive thoughts in the EMA-OCD data, compared to the Y-BOCS data; and all three participants reported previously unidentified compulsions/rituals/responses in the EMA-OCD data. As can be seen in Table 2 , Mary reported two intrusive thoughts in the EMA-OCD data that were not recorded in the Y-BOCS data. Additionally, she reported a previously unreported obsession under the obsession category Obsession with need for Symmetry or Exactness , not reported in the Y-BOCS data. Mary also reported variations on her compulsive behaviors and the presence of thought suppression not identified during the administration of the Y-BOCS. The EMA-OCD data indicated that John substituted one of his compulsions for an alternative anxiety reducing act, which was not recorded in the Y-BOCS data and suggests the identification of a previously unreported compulsion. Additionally, the EMA-OCD data indicated that John engaged in thought suppression to neutralize his intrusive thoughts. Likewise, John's reported compulsive behaviors also varied between data sets. In the EMA-OCD data he reported three previously unreported compulsive behaviors, and like Mary also the presence of thought suppression. In addition to the above, the EMA-OCD data indicated that John substituted one of his rituals for another, when he touched a crucifix instead of performing his usual hand washing ritual to cleanse him-self of the potential satanic possession. This was not something reported in the Y-BOCS data.

This study investigated the utility of EMA as an adjunct assessment approach for OCD. Each of our study hypotheses was supported. As predicted the EMA procedure resulted in the identification of additional types of obsessions and compulsions not captured by the Y-BOCS interview. The finding that the EMA procedure identifies obsession and compulsion symptoms not captured by the Y-BOCS suggests that further studies in this area are warranted. As a pilot case study we cannot generalize from these initial findings but our results indicate that a larger study replicating the procedure used here, is justified. Importantly, the three participants in our study were representative of quite typical OCD clients in that they had severe levels of symptoms and had OCD for a number of years. The EMA procedure we used was found to be satisfactory to all three participants. Feedback from the participants at the de-briefing session included suggestions that this process would be helpful for therapy because it would provide the therapist and client with rich and current material regarding their symptom patterns. From a clinician's point of view, collecting the EMA data is not onerous because the entries are simply short answers collected on 12 occasions and thus is not a time-consuming exercise.

The EMA procedure as used in this study could provide clinicians with a new method by which to gain a current and accurate snap-shot of clients symptoms as they occur in real-time. This information could augment information gained from standard pencil and paper measures but also provide an “active” process which may help to engage clients in the therapeutic process. It seems likely that using a procedure like EMA with OCD clients will assist in understanding their OCD experiences, and thus assist in generating valuable information, supporting accurate assessment, client conceptualization, and ultimately treatment.

Despite these valuable findings, there are limitations of this study. As a pilot study and exploratory in nature, it is only possible to draw limited interpretations from the data provided. However, the preliminary findings of this study support the benefit of conducting further research into this procedure, where it may be possible to draw more empirically valid findings from a larger and more statistically powerful sample. Second, due to the lack of availability of date stamping, participants were asked to record the time they made each recording. Unfortunately this was not routinely provided by all participants, and hence creates an unanswerable question regarding the accuracy of the data recorded. As Stone and Shiffman (2002) discuss, a potential problem relates to participants recording their data based on their recall of what was occurring at the time of the SMS prompt, rather than immediately. Hence introducing possible memory bias, and undermining the premise of the study. Although this is certainly an unwanted variable, based on the EMA-OCD data provided it seems that except for Mary, both John and Paul responded promptly to the SMS messages, or recorded the time if they didn't. Mary on the other hand, reported during the debrief session that she was unable to record the time for the initial targets, but did so for subsequent SMS prompts. It was not possible to ascertain from her data the delay in time between the first SMS prompts and her recordings. In future applications of this procedure, it is recommended that the device used provides automatic date-stamping to address this limitation. Indeed, it may be possible to adapt the EMA methodology for use with smart phones via a dedicated OCD application.

Concluding Remarks

The findings from this study of three patients with severe OCD suggest that the use of EMA provides important additional information regarding obsessions and compulsions and may thus be a useful adjunct to the clinical assessment of OCD.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three participants for taking part in this study.

Abramowitz, J. S. (1997). Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a quantitative review. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol . 65, 44–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.44

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Abramowitz, J. S. (2001). Treatment of scrupulous obsessions and compulsions using exposure and response prevention: a case report. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 8, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80046-8

CrossRef Full Text

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Chosak, A., Marques, L., Fama, J., Renaud, S., and Wilhelm, S. (2009). Cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case example. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.01.005

Clark, D. A. (1988). The validity of measures of cognition: a review of the literature. Cogn. Ther. Res . 12, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01172777

Cormier, S., and Nurius, P. S. (2003). Interviewing and Change Strategies for Helpers: Fundamental Skills and Cognitive Behavioral Interventions . Pacific Grove, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Deacon, B. J., and Abramowitz, J. S. (2005). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: factor analysis, construct validity, and suggestions for refinement. J. Anxiety Disord . 19, 573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.04.009

de Beurs, E., Lange, A., and Van Dyck, R. (1992). Self-monitoring of panic attacks and retrospective estimates of panic: discordant findings. Behav. Res. Ther . 30, 411–413. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90054-K

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., and Williams, J. B. W. (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition (SCID-IP Version 2.0) . New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Fisher, P. L., and Wells, A. (2008). Metacognitive therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: a case series. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 39, 117–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.12.001

Foa, E. B., and Franklin, M. E. (2001). “Obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Clinical Handbook Of Psychological Disorders , ed D. H. Barlow (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 209–263.

Glass, C. R., and Arnkoff, D. B. (1997). Questionnaire methods of cognitive self-statement assessment. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol . 65, 919–927. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.6.911

Gloster, A. T., Richard, D. C. S., Himle, J., Koch, E., Anson, H., Lokers, L., et al. (2008). Accuracy of retrospective memory and covariation estimation in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther . 46, 642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.010

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., Heninger, G. R., et al. (1989a). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: ii. validity. Arch Gen. Psychiatry 46, 1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., et al. (1989b). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: i. development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen. Psychiatry 46, 1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007

Grant, J. E., Pinto, A., Gunnip, M., Mancebo, M. C., Eisen, J. L., and Rasmussen, S. A. (2006). Sexual obsessions and clinical correlates in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehen. Psychiatry 47, 325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.01.007

Himle, M. B., and Franklin, M. E. (2009). The more you do it, the easier it gets: exposure and response prevention for OCD. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.03.002

Kamarack, T. W., Shiffman, S. M., Smithline, L., Goodie, J. L., Paty, J. A., Gyns, M., et al. (1998). Effects of task strain, social conflict, and emotional activation on ambulatory cardiovascular activity: daily life consequences of recurring stress in a multiethnic adult sample. Health Psychol . 17, 17–29. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.17

Kim, J. A., Dysken, M. W., and Katz, R. (1989). Rating scales for obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiat. Anna . 19, 74–79.

Kimhy, D., Delespaul, P., Corcoran, C., Ahn, H., Yale, S., and Malaspina, D. (2006). Computerized experience sampling method (ESMc): assessing feasibility and validity among individuals with schizophrenia. J. Psychiat. Res . 40, 221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.007

Litt, M. D., Cooney, N. L., and Morse, P. (1998). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) with treated alcoholics: methodological problems and potential solutions. Health Psychol . 17, 48–52. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.48

Marks, M., and Hemsley, D. (1999). Retrospective versus prospective self-rating of anxiety symptoms and cognitions. J. Anxiety Disord . 13, 463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00015-8

Morgan, J., McSharry, K., and Sireling, L. (1990). Comparison of a system of staff prompting with a programmable electronic diary in a patient with Korsakoff's Syndrome. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 36, 225–229. doi: 10.1177/002076409003600308

Newth, S., and Rachman, S. (2001). The concealment of obsessions. Behav. Res. Ther . 39, 457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00006-1

Putnam, K. M., and McSweeney, L. B. (2008). Depressive symptoms and baseline prefrontal EEG alpha activity: a study utilizing Ecological Momentary Assessment. Biol. Psychol . 77, 237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.010

Rachman, S. (2007). Unwanted intrusive images in obsessive compulsive disorders. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 38, 402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.008

Rees, C. S. (2009). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Practical Guide to Treatment . East Hawthorn, VIC: IP Communications.

Schwartz, J. E., and Stone, A. A. (1998). Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol . 17, 6–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.6

Steketee, G., and Barlow, D. H. (2002). “Obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Anxiety and its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic, 2nd Edn . ed D. H. Barlow (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 516–550.

Stone, A., and Shiffman, S. (2002). Capturing momentary, self-report data: a proposal for reporting guidelines. Ann. Behav. Med . 24, 236–243. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2403_09

Stone, A. A., Broderick, J. E., Shiffman, S. S., and Schwartz, J. E. (2004). Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain , 107, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.020

Stone, A. A., and Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Ann. Behav. Med . 16, 199–202.

Taylor, S. (1995). Assessment of obsessions and compulsions: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to treatment effects. Clin. Psychol. Rev . 15, 261–296. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(95)00015-h

Taylor, S. (1998). “Assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment , eds R. P. Swinson, M. M. Antony, S. Rachman, and M. A. Richter (New York, NY: Guildford Press), 229–258.

Tolin, D. F. (2009). Alphabet Soup: ERP, CT, and ACT for OCD. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.07.001

Trull, T. J., Solhan, M. B., Tragesser, S. L., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Piasecki, T. M., et al. (2008). Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. J. Abnorm. Psychol . 117, 647–661. doi: 10.1037/a0012532

Whittal, M. L., Robichaud, M., and Woody, S. R. (2010). Cognitive treatment of obsessions: enhancing dissemination with video components. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 17, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.07.001

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), ecological momentary assessment, ecological momentary assessment data, anxiety disorders, assessment

Citation: Tilley PJM and Rees CS (2014) A clinical case study of the use of ecological momentary assessment in obsessive compulsive disorder. Front. Psychol . 5 :339. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00339

Received: 10 March 2014; Accepted: 01 April 2014; Published online: 17 April 2014.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2014 Tilley and Rees. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Clare S. Rees, Brain, Behaviour and Mental Health Research Group, School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia e-mail: [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Mental Health Academy

- Case Studies

- Communication Skills

- Counselling Microskills

- Counselling Process

- Children & Families

- Ethical Issues

- Sexuality & Gender Issues

- Neuropsychology

- Practice Management

- Relationship Counselling

- Social Support

- Therapies & Approaches

- Workplace Issues

- Anxiety & Depression

- Personality Disorders

- Self-Harming & Suicide

- Effectiveness Skills

- Stress & Burnout

- Diploma of Counselling

- Diploma of Financial Counselling

- Diploma of Community Services (Case Management)

- Diploma of Youth Work

- Bachelor of Counselling

- Bachelor of Human Services

- Master of Counselling

Case Study: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

In a previous article we reviewed a range of treatments that are used to help clients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In this edition we showcase the case study of Darcy [fictional name], who worked with a psychologist to address the symptoms and history of her OCD.

Marian, a psychologist who specialised in anxiety disorders, closed the file and put it into the filing cabinet with a smile on her face. This time she had the satisfaction of filing it into the “Work Completed” files, for she had just today celebrated the final session with a very long-term client: Darcy Dawson. They’d come through a lot together, Darcy and Marian, during the twelve years of Darcy’s treatment for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and they had had a particularly strong therapeutic alliance.

Marian reflected on the symptoms and history which had brought Darcy into her practice.

Obsessions at age nine

Now 37, Darcy reckoned that she had begun having obsessions around age nine, soon after her beloved grandma had died. Already grieving the loss of the person she was closest to in life, Darcy experienced further alienation – and resultant anxiety — when her father relocated the family from the small town in Victoria where they lived to Melbourne. Adjusting to big-city life wasn’t easy for someone as anxious as Darcy, and she soon found that she was obsessing. She had fears of being hit by a speeding car if she stepped off the kerb. She feared that the new friends she began to develop in Melbourne would be kidnapped by bad people. And she was terrified that, if she didn’t do an elaborate prayer routine at night, all manner of terrible things would befall her family.

The prayer routine, relatively simple at first, grew to gigantic proportions, containing many rules and restrictions. Darcy believed that she had to repeat each family member’s full name 15 times, say a sentence that asked for each person to be kept safe, promise God that she would improve herself, clap her hands 20 times for each person, kneel down and get up 5 times, and then put her hands into a prayer position while bowing. She “had” to do this routine at least 10 times each night, and if she made a mistake anywhere along the way, she had to start totally over again from the beginning, or else something bad would happen to her parents or little brother. Once she went flying to her mother’s side in the kitchen, tears streaming down her face, because she couldn’t get her “prayers” right. Darcy was certain that she was a huge disappointment to God and everybody.

Just like Granddad