Stephen Hawking biography: Theories, books & quotes

A brief history of theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking.

- Scientific achievements

- Filmography

- Quotes and controversial statements

Additional resources

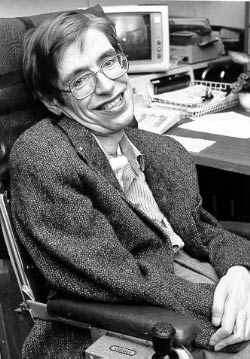

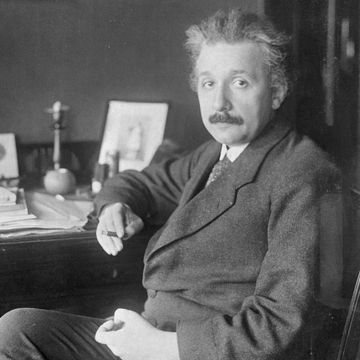

Stephen Hawking is regarded as one of the most brilliant theoretical physicists in history.

His work on the origins and structure of the universe, from the Big Bang to black holes, revolutionized the field, while his best-selling books have appealed to readers who may not have Hawking's scientific background. Hawking died on March 14, 2018 , at the age of 76.

Stephen Hawking was seen by many as the world's smartest person, though he never revealed his IQ score. When asked about his IQ score by a New York Times reporter he replied, "I have no idea, people who boast about their IQ are losers," according to the news site The Atlantic .

Related: 4 bizarre Stephen Hawking theories that turned out to be right (and 6 we're not sure about)

In this brief biography, we look at Hawking's education and career — ranging from his discoveries to the popular books he's written — and the disease that robbed him of mobility and speech.

The early life of Stephen Hawking

British cosmologist Stephen William Hawking was born in Oxford, England on Jan. 8, 1942 — 300 years to the day after the death of the astronomer Galileo Galilei . He attended University College, Oxford, where he studied physics, despite his father's urging to focus on medicine. Hawking went on to Cambridge to research cosmology , the study of the universe as a whole.

In early 1963, just shy of his 21st birthday, Hawking was diagnosed with motor neuron disease, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) . Doctors told Hawkings that he would likely not survive more than two years with the disease. Completing his doctorate did not appear likely, but Hawking defied the odds. He also obtained his PhD in 1966 for his thesis entitled " Properties of expanding universes ". In that same year, Hawking also won the prestigious Adams Prize for his essay entitled "Singularities and the Geometry of Space-Time".

From then Hawking went on to forge new roads into the understanding of the universe in the decades since.

As the disease spread, Hawking became less mobile and began using a wheelchair. Talking grew more challenging and, in 1985, an emergency tracheotomy caused his total loss of speech. A speech-generating device constructed at Cambridge, combined with a software program, served as his electronic voice, allowing Hawking to select his words by moving the muscles in his cheek.

Just before his diagnosis, Hawking met Jane Wilde, and the two were married in 1965. The couple had three children before separating in 1990. Hawking remarried in 1995 to Elaine Mason but divorced in 2006.

Stephen Hawking's greatest scientific achievements

Throughout his career, Hawking proposed several theories regarding astronomical anomalies, posed curious questions about the cosmos and enlightened the world about the origin of everything. Here are just some of the many milestones Hawking made in the name of science.

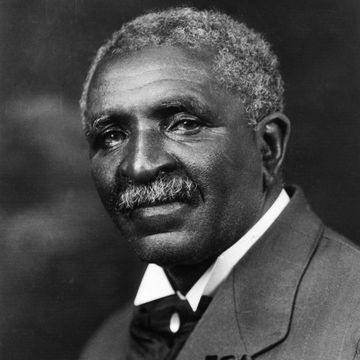

In 1970, Hawkings and fellow physicist and Oxford classmate, Roger Penrose, published a joint paper entitled " The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology ". In this paper, Hawking and Penrose proposed a new theory of spacetime singularities — a breakdown in the fabric of the universe found in one of Hawking's later discoveries, the black hole. This early work not only challenged concepts in physics but also supported the concept of the Big Bang as the birth of the universe, as outlined in Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity in the 1940s.

Over the course of his career, Hawking studied the basic laws governing the universe. In 1974, Hawking published another paper called " Black hole explosions? ", in which he outlined a theorem that united Einstein's theory of general relativity, with quantum theory — which explains the behavior of matter and energy on an atomic level. In this new paper, Hawking hypothesized that matter not only fell into the gravitational pull of black holes but that photons radiated from them — which has now been confirmed in laboratory experiments by the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Israel — aptly named "Hawking radiation".

In 1974, Hawking was inducted into the Royal Society, a worldwide fellowship of scientists. Five years later, he was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, the most famous academic chair in the world (the second holder was Sir Isaac Newton , also a member of the Royal Society).

During the 1980s, Hawking turned his attention to the Big Bang and the uncertainties about the beginning of the universe. "Events before the Big Bang are simply not defined, because there’s no way one could measure what happened at them. Since events before the Big Bang have no observational consequences, one may as well cut them out of the theory and say that time began at the Big Bang," he said during his lecture called The Beginning of Time . In 1983, Hawking, along with scientists James Harlte, published a paper outlining their " no-boundary proposal " for the universe. In their paper, Hawking and Hartle describe the shape of the universe as reminiscent of a shuttlecock — with the Big Bang at the narrowest point and the expanding universe emerging from it.

Related: Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Books by Stephen Hawking

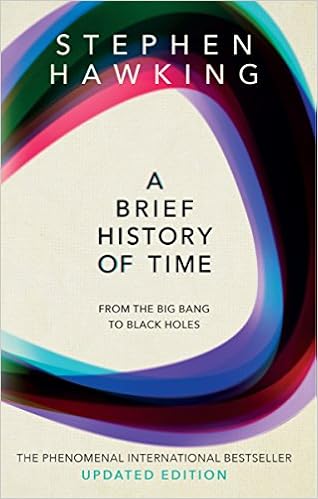

In the last three decades of Hawking's life, he not only continued to publish academic literature, but he also published several popular science books to share his theories of the history of the universe with the layperson. His most popular book " A Brief History of Time " (10th-anniversary edition: Bantam, 1998) was first published in 1988 and became an international bestseller. It has sold almost 10 million copies and has been translated into 40 different languages.

Hawking went on to write other nonfiction books aimed at non-scientists. These include " A Briefer History of Time ," " The Universe in a Nutshell ," " The Grand Design " and " On the Shoulders of Giants ."

Along with his many successful books about the inner workings of the universe, Hawking also began a series of science fiction books called " George and the Big Bang ", with his daughter Lucy Hawking in 2011. Aimed at middle school children, the series follows George's adventures as he travels through space.

Stephen Hawking's filmography

Hawking has made several television appearances, including a playing hologram of himself on "Star Trek: The Next Generation" and a cameo on the television show "Big Bang Theory." He has also voiced himself in several episodes of the animated series "Futurama" and "The Simpson". In 1997, PBS also presented an educational miniseries titled " Stephen Hawking's Universe ," which probes the theories of the cosmologist.

In 2014, a movie based on Hawking's life was released. Called "The Theory of Everything," the film drew praise from Hawking , who said it made him reflect on his own life. "Although I'm severely disabled, I have been successful in my scientific work," Hawking wrote on Facebook in November 2014. "I travel widely and have been to Antarctica and Easter Island, down in a submarine and up on a zero-gravity flight. One day, I hope to go into space."

Related: The Theory of Everything: Searching for the universal rules of physics

Stephen Hawking's quotes and controversial statements

Hawking's quotes range from notable to poetic to controversial. Among them:

- "Even if there is only one possible unified theory, it is just a set of rules and equations. What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing? "— A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes , 1988

- "All of my life, I have been fascinated by the big questions that face us, and have tried to find scientific answers to them. If, like me, you have looked at the stars, and tried to make sense of what you see, you too have started to wonder what makes the universe exist."— Stephen Hawking's Universe , 1997.

- "Science predicts that many different kinds of universe will be spontaneously created out of nothing. It is a matter of chance which we are in." — The Guardian, 2011 .

- "We should seek the greatest value of our action." — The Guardian, 2011.

- "The whole history of science has been the gradual realization that events do not happen in an arbitrary manner, but that they reflect a certain underlying order, which may or may not be divinely inspired. "— A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes , 1988.

- "The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge."

- "It is not clear that intelligence has any long-term survival value." — Life in the Universe , 1996.

- "One cannot really argue with a mathematical theorem." — A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes , 1988.

- "It is a waste of time to be angry about my disability. One has to get on with life and I haven't done badly. People won't have time for you if you are always angry or complaining." — The Guardian, 2005 .

- "I relish the rare opportunity I've been given to live the life of the mind. But I know I need my body and that it will not last forever." — Stem Cell Universe , 2014.

A list of Hawking quotes would be incomplete without mentioning some of his more controversial statements.

He frequently said that humans must leave Earth if we wished to survive.

- "It will be difficult enough to avoid disaster in the next hundred years, let alone the next thousand or million...Our only chance of long-term survival is not to remain inward-looking on planet Earth, but to spread out into space," he said during an interview with video site Big Think , 2010.

- "[W]e must … continue to go into space for the future of humanity…I don't think we will survive another 1,000 years without escaping beyond our fragile planet," Hawking said during a lecture at the Oxford Union debating society , 2016.

- "We are running out of space and the only places to go to are other worlds. It is time to explore other solar systems. Spreading out may be the only thing that saves us from ourselves. I am convinced that humans need to leave Earth," he said during a speech at the Starmus Festival in Norway, 2017.

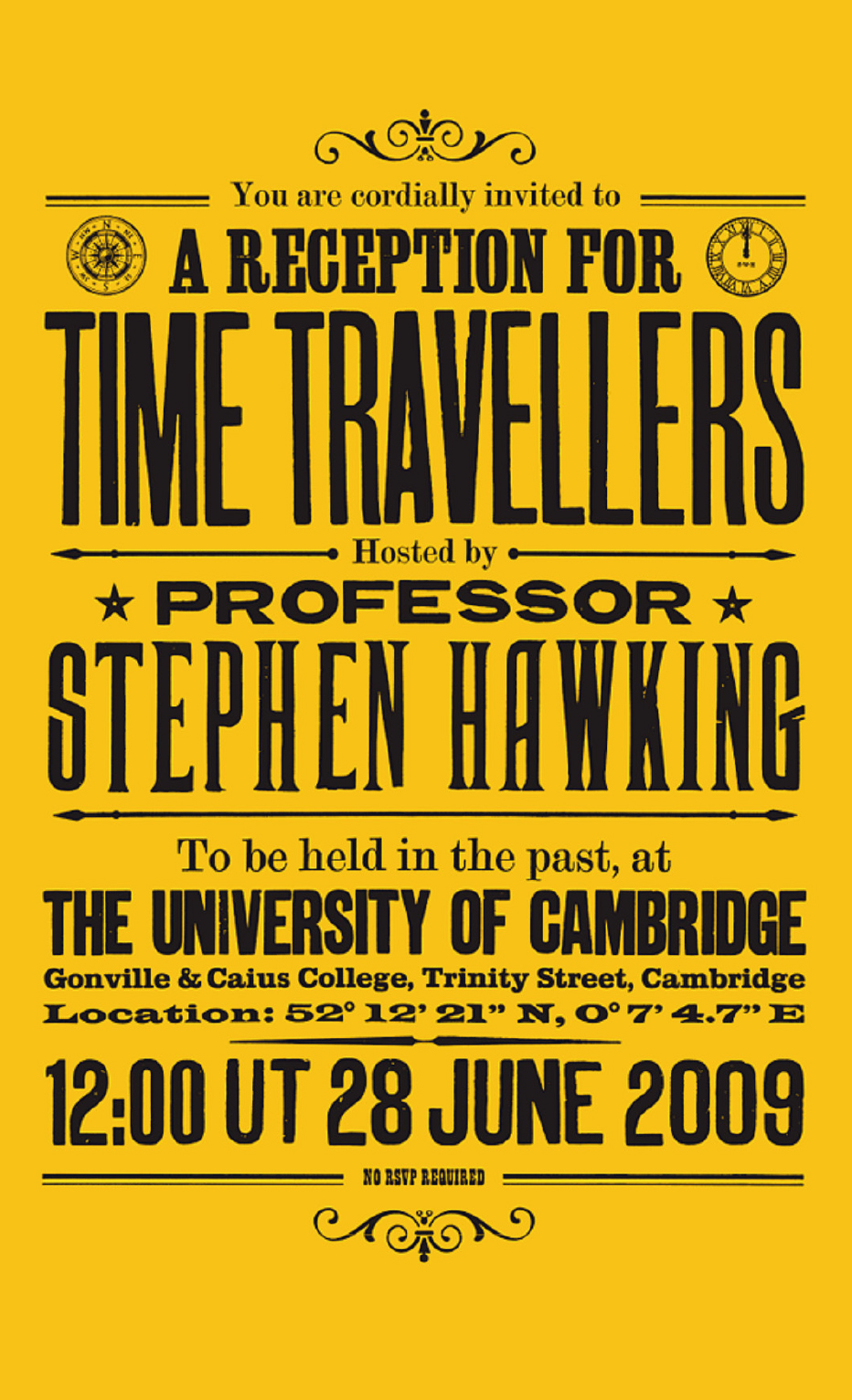

He also said time travel should be possible, and that we should explore space for the romance of it.

"Time travel used to be thought of as just science fiction, but Einstein's general theory of relativity allows for the possibility that we could warp space-time so much that you could go off in a rocket and return before you set out. I was one of the first to write about the conditions under which this would be possible. I showed it would require matter with negative energy density, which may not be available. Other scientists took courage from my paper and wrote further papers on the subject," he told the new site Parade in 2010. "Science is not only a disciple of reason, but, also, one of romance and passion," he adds.

The theoretical physicist was also concerned that robots could not only have an impact on the economy but also mean doom for humanity.

"The automation of factories has already decimated jobs in traditional manufacturing, and the rise of artificial intelligence is likely to extend this job destruction deep into the middle classes, with only the most caring, creative or supervisory roles remaining," he wrote in a 2016 column in The Guardian .

"The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race," he told the BBC in 2014. Hawking added, however, that AI developed to date has been helpful. It's more the self-replication potential that worries him. "It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever-increasing rate. Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn't compete, and would be superseded."

"The genie is out of the bottle. I fear that AI may replace humans altogether," Hawking told WIRED in November 2017.

An avowed atheist, Hawking also occasionally waded into the topic of religion.

- "Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist. It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going." — The Grand Design, by Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow.

- "I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail…There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark," he said during a 2011 interview with The Guardian .

- "Before we understand science, it is natural to believe that God created the universe. But now science offers a more convincing explanation. What I meant by 'we would know the mind of God' is, we would know everything that God would know, if there were a God, which there isn't. I'm an atheist," Hawking said in a 2014 interview with the news site El Mundo .

For more information about Stephen Hawking, his theories and read through the many transcriptions of his influential lectures, check out his official website . You can also watch Hawking probe the origins of the cosmos in his extraordinary TED talk .

Bibliography

#5: Stephen Hawking’s warning: Abandon earth-or face extinction . Big Think. (2010, July 27). https://bigthink.com/surprising-science/5-stephen-hawkings-warning-abandon-earth-or-face-extinction/

Beck, J. (2017, October 11). “people who boast about their IQ are losers.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/10/trump-tillerson-iq-brag-boast-psychology-study/542544/

The beginning of time . Stephen Hawking. (n.d.-c). https://www.hawking.org.uk/in-words/lectures/the-beginning-of-time

Guardian News and Media. (2005, September 27). Interview: Stephen Hawking . The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/sep/27/scienceandnature.highereducationprofile

Guardian News and Media. (2011a, May 15). Stephen Hawking: “there is no heaven; it’s a Fairy story.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/may/15/stephen-hawking-interview-there-is-no-heaven

Guardian News and Media. (2011b, May 15). Stephen Hawking: “there is no heaven; it’s a Fairy story.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/may/15/stephen-hawking-interview-there-is-no-heaven

Guardian News and Media. (2016, December 1). This is the most dangerous time for our planet | Stephen Hawking . The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/dec/01/stephen-hawking-dangerous-time-planet-inequality

Hartle, J. B., & Hawking, S. W. (1983, December 15). Wave function of the universe . Physical Review D. https://journals.aps.org/prd/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevD.28.2960

Hawking radiation and the sonic black hole - technion - israel institute of technology . Technion. (2021, February 17). https://www.technion.ac.il/en/2021/02/hawking-radiation-and-the-sonic-black-hole/

Hawking, S. W. (1974, March 1). Black Hole Explosions? . Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/248030a0

Life in the universe . Stephen Hawking. (n.d.-a). https://www.hawking.org.uk/in-words/lectures/life-in-the-universe

Medeiros, J. (2017, November 28). Stephen Hawking: “I fear ai may replace humans altogether.” WIRED UK. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/stephen-hawking-interview-alien-life-climate-change-donald-trump

Oxford Union Speech . Stephen Hawking. (n.d.-b). https://www.hawking.org.uk/in-words/speeches/speech-5

Pablo Jáuregui, Enviado especial Guía de Isora (Tenerife), & Chocolatillo. (2018, March 14). Stephen Hawking: “no hay ningún dios. soy ateo.” ELMUNDO. https://www.elmundo.es/ciencia/2014/09/21/541dbc12ca474104078b4577.html

The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology . Royal Society Publishing. (1970, January 27). https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspa.1970.0021

Hawking, S. W. (1966). Properties of expanding universes. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.11283

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd

- Scott Dutfield Contributor

NASA gets $25.4 billion in White House's 2025 budget request

'Interstellar meteor' vibrations actually caused by a truck, study suggests

How to stay safe during the April 8 solar eclipse

Most Popular

By Fran Ruiz January 26, 2024

By Conor Feehly January 05, 2024

By Keith Cooper December 22, 2023

By Fran Ruiz December 20, 2023

By Fran Ruiz December 19, 2023

By Fran Ruiz December 18, 2023

By Tantse Walter December 18, 2023

By Robert Lea December 05, 2023

By Robert Lea December 04, 2023

By Robert Lea December 01, 2023

By Rebecca Sohn November 27, 2023

- 2 Massive explosions may be visible on the sun during the April 8 total solar eclipse

- 3 Satellites watch Iceland volcano spew gigantic plume of toxic gas across Europe

- 4 Flight attendant becomes 1st Belarusian woman in space on ISS-bound Soyuz launch

- 5 This Week In Space podcast: Episode 103 — Starship's Orbital Feat

Biography of Stephen Hawking, Physicist and Cosmologist

Karwai Tang/Getty Images

- Important Physicists

- Physics Laws, Concepts, and Principles

- Quantum Physics

- Thermodynamics

- Cosmology & Astrophysics

- Weather & Climate

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/AZJFaceShot-56a72b155f9b58b7d0e783fa.jpg)

- M.S., Mathematics Education, Indiana University

- B.A., Physics, Wabash College

Stephen Hawking (January 8, 1942–March 14, 2018) was a world-renowned cosmologist and physicist, especially esteemed for overcoming an extreme physical disability to pursue his groundbreaking scientific work. He was a bestselling author whose books made complex ideas accessible to the general public. His theories provided deep insights into the connections between quantum physics and relativity, including how those concepts might be united in explaining fundamental questions related to the development of the universe and the formation of black holes.

Fast Facts: Stephen Hawking

- Known For : Cosmologist, physicist, best-selling science writer

- Also Known As : Steven William Hawking

- Born : January 8, 1942 in Oxfordshire, England

- Parents : Frank and Isobel Hawking

- Died: March 14, 2018 in Cambridge, England

- Education : St Albans School, B.A., University College, Oxford, Ph.D., Trinity Hall, Cambridge, 1966

- Published Works : A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes, The Universe in a Nutshell, On the Shoulders of Giants, A Briefer History of Time, The Grand Design, My Brief History

- Awards and Honors : Fellow of the Royal Society, the Eddington Medal, the Royal Society's Hughes Medal, the Albert Einstein Medal, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, the Wolf Prize in Physics, the Prince of Asturias Awards in Concord, the Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society, the Michelson Morley Award of Case Western Reserve University, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society

- Spouses : Jane Wilde, Elaine Mason

- Children : Robert, Lucy, Timothy

- Notable Quote : “Most of the threats we face come from the progress we’ve made in science and technology. We are not going to stop making progress, or reverse it, so we must recognize the dangers and control them. I’m an optimist, and I believe we can.”

Stephen Hawking was born on January 8, 1942, in Oxfordshire, England, where his mother had been sent for safety during the German bombings of London of World War II. His mother Isobel Hawking was an Oxford graduate and his father Frank Hawking was a medical researcher.

After Stephen's birth, the family reunited in London, where his father headed the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research. The family then moved to St. Albans so that Stephen's father could pursue medical research at the nearby Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill.

Education and Medical Diagnosis

Stephen Hawking attended school in St. Albans, where he was an unexceptional student. His brilliance was much more apparent in his years at Oxford University. He specialized in physics and graduated with first-class honors despite his relative lack of diligence. In 1962, he continued his education at Cambridge University, pursuing a Ph.D. in cosmology.

At age 21, a year after beginning his doctoral program, Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as motor neuron disease, ALS, and Lou Gehrig's disease). Given only three years to live, he has written that this prognosis helped motivate him in his physics work .

There is little doubt that his ability to remain actively engaged with the world through his scientific work helped him persevere in the face of the disease. The support of family and friends were equally key. This is vividly portrayed in the dramatic film "The Theory of Everything."

The ALS Progresses

As his illness progressed, Hawking became less mobile and began using a wheelchair. As part of his condition, Hawking eventually lost his ability to speak, so he utilized a device capable of translating his eye movements (since he could no longer utilize a keypad) to speak in a digitized voice.

In addition to his keen mind within physics, he gained respect throughout the world as a science communicator. His achievements are deeply impressive on their own, but some of the reason he is so universally respected was his ability to accomplish so much while suffering the severe debility caused by ALS.

Marriage and Children

Just before his diagnosis, Hawking met Jane Wilde, and the two were married in 1965. The couple had three children before separating. Hawking later married Elaine Mason in 1995 and they divorced in 2006.

Career as Academic and Author

Hawking stayed on at Cambridge after his graduation, first as a research fellow and then as a professional fellow. For most of his academic career, Hawking served as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a position once held by Sir Isaac Newton .

Following a long tradition, Hawking retired from this post at age 67, in the spring of 2009, though he continued his research at the university's cosmology institute. In 2008 he also accepted a position as a visiting researcher at Waterloo, Ontario's Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics.

In 1982 Hawking began work on a popular book on cosmology. By 1984 he had produced the first draft of "A Brief History of Time," which he published in 1988 after some medical setbacks. This book remained on the Sunday Times bestsellers list for 237 weeks. Hawking's even more accessible "A Briefer History of Time" was published in 2005.

Fields of Study

Hawking's major research was in the areas of theoretical cosmology , focusing on the evolution of the universe as governed by the laws of general relativity . He is most well-known for his work in the study of black holes . Through his work, Hawking was able to:

- Prove that singularities are general features of spacetime.

- Provide mathematical proof that information which fell into a black hole was lost.

- Demonstrate that black holes evaporate through Hawking radiation .

On March 14, 2018, Stephen Hawking died in his home in Cambridge, England. He was 76. His ashes were placed in London’s Westminster Abbey between the final resting places of Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin.

Stephen Hawking made large contributions as a scientist, science communicator, and as a heroic example of how enormous obstacles can be overcome. The Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication is a prestigious award that "recognizes the merit of popular science on an international level."

Thanks to his distinctive appearance, voice, and popularity, Stephen Hawking is often represented in popular culture. He made appearances on the television shows "The Simpsons" and "Futurama," as well as having a cameo on "Star Trek: The Next Generation" in 1993.

"The Theory of Everything," a biographical drama film about Hawking's life, was released in 2014.

- “ Stephen Hawking .” Famous Scientists .

- Redd, Nola Taylor. “ Stephen Hawking Biography (1942-2018) .” Space.com , Space, 14 Mar. 2018.

- “ Stephen William Hawking .” Stephen Hawking (1942-2018) .

- Biography of Brian Cox

- What Is Astronomy and Who Does It?

- Leonard Susskind Bio

- Niels Bohr and the Manhattan Project

- Biography of Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist

- Understanding Cosmology and Its Impact

- Biography of Physicist Paul Dirac

- Biography of Ernest Rutherford

- Georges-Henri Lemaitre and the Birth of the Universe

- What Is the Anthropic Principle?

- The History of Gravity

- Biography of Joseph Louis Lagrange, Mathematician

- Biography of Mary Somerville, Mathematician, Scientist, and Writer

- Biography of Pierre Curie, Influential French Physicist, Chemist, Nobel Laureate

- Niels Bohr Institute

Biography Online

Stephen Hawking Biography

Early life Stephen Hawking

Stephen William Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 in Oxford, England. His family had moved to Oxford to escape the threat of V2 rockets over London. As a child, he showed prodigious talent and unorthodox study methods. On leaving school, he got a place at University College, Oxford University where he studied Physics. His physics tutor at Oxford, Robert Berman, later said that Stephen Hawking was an extraordinary student. He used few books and made no notes, but could work out theorems and solutions in a way other students couldn’t.

“My goal is simple. It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is and why it exists at all.”

– Stephen Hawking’s Universe (1985) by John Boslough, Ch. 7

It was in Cambridge that Stephen Hawking first started to develop symptoms of neuro-muscular problems – a type of motor neuron disease. This quickly started to hamper his physical movements. His speech became slurred, and he became unable to even to feed himself. At one stage, the doctors gave him a lifespan of three years. However, the progress of the disease slowed down, and he has managed to overcome his severe disability to continue his research and active public engagements. At Cambridge, a fellow scientist developed a synthetic speech device which enabled him to speak by using a touchpad. This early synthetic speech sound has become the ‘voice’ of Stephen Hawking, and as a result, he has kept the original sound of this early model – despite technological advancements.

Nevertheless, despite the latest technology, it can still be a time-consuming process for him to communicate. Stephen Hawking has taken a pragmatic view to his disability:

“It is a waste of time to be angry about my disability. One has to get on with life and I haven’t done badly. People won’t have time for you if you are always angry or complaining. ” The Guardian (27 September 2005)

Stephen Hawking’s principal fields of research have been involved in theoretical cosmology and quantum gravity.

Amongst many other achievements, he developed a mathematical model for Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. He has also undertaken a lot of work on the nature of the Universe, The Big Bang and Black Holes.

In 1974, he outlined his theory that black holes leak energy and fade away to nothing. This became known as “Hawking radiation” in 1974. With mathematicians Roger Penrose he demonstrated that Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity implies space and time would have a beginning in the Big Bang and an end in black holes.

Despite being one of the best physicists of his generation, he has also been able to translate difficult physics models into a general understanding for the general public. His books – A Brief History of Time and The Universe in A Nutshell have both became runaway bestsellers – with a Brief History of Time staying in the Bestsellers lists for over 230 weeks and selling over 10 million copies. In his books, Hawking tries to explain scientific concepts in everyday language and give an overview to the workings behind the cosmos.

“The whole history of science has been the gradual realization that events do not happen in an arbitrary manner, but that they reflect a certain underlying order, which may or may not be divinely inspired.”

– A Brief History Of Time (1998) ch. 8

Stephen Hawking has become one of the most famous scientists of his generation. He makes frequent public engagements and his portrayed himself in popular media culture from programmes, such as The Simpsons to Star Trek.

Hawking had the capacity to relate the most complex physics to relateable incidents in everyday life.

“The message of this lecture is that black holes ain’t as black as they are painted. They are not the eternal prisons they were once thought. Things can get out of a black hole both on the outside and possibly to another universe. So if you feel you are in a black hole, don’t give up – there’s a way out.”

Stephen Hawking. 7 January 2016 – Reith lecture at the Royal Institute in London.

In the late 1990s, he was reportedly offered a knighthood, but 10 years later revealed he had turned it down over issues with the government’s funding for science

He married Jane Wilde, a language student in 1965. He said this was a real turning point for him at a time when he was fatalistic because of his illness. They later divorced but had three children.

Stephen Hawking passed away on 14 March 2018 at his home in Cambridge.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Stephen Hawking ”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Last updated 15 January 2018.

A Brief History Of Time

A Brief History Of Time by Stephen Hawking at Amazon

Quotes of Stephen Hawking

“If we do discover a complete theory, it should in time be understandable in broad principle by everyone, not just a few scientists. Then we shall all, philosophers, scientists, and just ordinary people, be able to take part in the discussion of the question of why it is that we and the universe exist. If we find the answer to that, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason — for then we would know the mind of God.”

– Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (1993)

“Even if there is only one possible unified theory, it is just a set of rules and equations. What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?”

– A Brief History of Time (1988)

“One, remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Two, never give up work. Work gives you meaning and purpose and life is empty without it. Three, if you are lucky enough to find love, remember it is there and don’t throw it away.”

– Stephen Hawking

“For millions of years, mankind lived just like the animals. Then something happened which unleashed the power of our imagination. We learned to talk and we learned to listen. Speech has allowed the communication of ideas, enabling human beings to work together to build the impossible. Mankind’s greatest achievements have come about by talking, and its greatest failures by not talking. It doesn’t have to be like this. Our greatest hopes could become reality in the future. With the technology at our disposal, the possibilities are unbounded. All we need to do is make sure we keep talking.”

– Stephen Hawking (BT advert 1993)

Related pages

- Stephen Hawking.org.uk

Stephen hawkings amazing scientist

- February 20, 2019 5:18 AM

- By Rambharat Singh

Very interesting and helpful to know the supernova of physics

- April 16, 2018 2:34 PM

- By Jiji nixon

MacTutor

Stephen william hawking.

I got an education there that was as good as, if not better than, that I would have had at Westminster. I have never found that my lack of social graces has been a hindrance.

The prevailing attitude at Oxford at that time was very anti-work. You were supposed to be brilliant without effort, or accept your limitations and get a fourth-class degree. To work hard to get a better class of degree was regarded as the mark of a grey man - the worst epithet in the Oxford vocabulary.

... although there was a cloud hanging over my future, I found to my surprise that I was enjoying life in the present more than I had before. I began to make progress with my research...

... I therefore started working for the first time in my life. To my surprise I found I liked it.

... that both time and space are finite in extent, but they don't have any boundary or edge. ... there would be no singularities, and the laws of science would hold everywhere, including at the beginning of the universe.

I was in Geneva, at CERN, the big particle accelerator, in the summer of 1985 . ... I caught pneumonia and was rushed to hospital. The hospital in Geneva suggested to my wife that it was not worth keeping the life support machine on. But she was having none of that. I was flown back to Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, where a surgeon called Roger Grey carried out a tracheotomy. That operation saved my life but took away my voice.

While many prominent physicists, cosmologists and astronomers have made important contributions to the study of quantum gravity and cosmology, the impact of Stephen Hawking's contributions to the field truly stand out. Although his work on black hole thermodynamics is perhaps the most well known, Hawking has also made major contributions to the study of singularity theorems in general relativity, black hole uniqueness, quantum fields in curved spacetimes, Euclidean quantum gravity, the wave function of the universe and many other areas as well. In addition to his own work, Hawking has served as advisor and mentor to a remarkable set of students. Furthermore, it would be hard to imagine assembling any list of researchers working in quantum cosmology without including a large number of Hawking's students and close colleagues. Thus the group that gathered at the CMS in Cambridge in honour of his 60 th birthday includes some of the leading theorists in the field.

... for boldness and creativity in gravitational physics, best illustrated by the prediction that black holes should emit black body radiation and evaporate, and for the special gift of making abstract ideas accessible and exciting to experts, generalists, and the public alike.

Stephen Hawking has contributed as much as anyone since Einstein to our understanding of gravity. This medal is a fitting recognition of an astonishing research career spanning more than 40 years.

Stephen Hawking is a definitive hero to all of us involved in exploring the Cosmos. His contribution to science is unique and he serves as a continuous inspiration to every thinking person. It was an honour for the crew of the STS- 121 mission to fly his medal into space. We think that this is particularly appropriate as Stephen has dedicated his life to thinking about the larger Universe.

This is a very distinguished medal. It was awarded to Darwin, Einstein and Crick. I am honoured to be in their company.

References ( show )

- Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Stephen-W-Hawking

- S Hawking, Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays ( London, 1993) .

Additional Resources ( show )

Other pages about Stephen Hawking:

- Guardian obituary

- New York Times obituary

- Multiple entries in The Mathematical Gazetteer of the British Isles ,

- Miller's postage stamps

Other websites about Stephen Hawking:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Stephen Hawking's home page

- A Google doodle

- Mathematical Genealogy Project

- MathSciNet Author profile

- zbMATH entry

Honours ( show )

Honours awarded to Stephen Hawking

- Lucasian Professor 1979

- LMS Naylor Prize 1999

- Copley Medal 2006

- Google doodle 2022

Cross-references ( show )

- History Topics: A history of time: 20 th century time

- History Topics: The development of the 'black hole' concept

- Societies: Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Other: 2009 Most popular biographies

- Other: Cambridge Colleges

- Other: Cambridge Individuals

- Other: Cambridge professorships

- Other: Jeff Miller's postage stamps

- Other: London Museums

- Other: Most popular biographies – 2024

- Other: Oxford Institutions and Colleges

- Other: Oxford individuals

- Other: Popular biographies 2018

Stephen Hawking, Famed Physicist, Dies at 76

Hawking's scientific claim to fame was his revelation that the universe began in a singularity, an infinitely dense point of spacetime.

Stephen Hawking, the British theoretical physicist who found a link between gravity and quantum theory, and who declared that black holes aren't really black at all, has died, a spokesperson for the family told the Guardian and the Associated Press .

“He was a great scientist and an extraordinary man whose work and legacy will live on for many years," Hawking's children Lucy, Robert, and Tim said in a statement. "His courage and persistence with his brilliance and humor inspired people across the world.

“He once said: ‘It would not be much of a universe if it wasn’t home to the people you love.’ We will miss him for ever.”

Hawking was 76 years old, more than 50 years older than the age doctors told him he could expect to reach after being diagnosed in 1963 with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) , also called Lou Gehrig's disease.

"Few, if any, have done more to deepen our knowledge of gravity, space, and time," said British astrophysicist Martin Rees . In a reminiscence to mark the occasion of his Cambridge University colleague's improbable 70th birthday, he recalled a young man who was unsteady on his feet and spoke with great difficulty. No one expected him to live long enough to earn his Ph.D.

Although his degenerative disease progressively crippled him and robbed him of speech, Hawking did more than survive. He became "arguably the most famous scientist in the world," Rees said, "acclaimed for his brilliant research, for his best-selling books [about space, time, and the cosmos], and, above all, for his astonishing triumph over adversity."

Hawking's scientific claim to fame was his revelation that the universe began in a singularity, an infinitely dense point of space-time. Working with mathematical physicist Roger Penrose , he would show that Einstein's General Theory of Relativity "implied space and time would have a beginning in the big bang and an end in black holes," according to Hawking's website, and that "the way the universe began was completely determined by the laws of science."

In the early 1970s, he was the first to show that radiation escapes from black holes and that the holes aren't completely black. His theory explaining what came to be called Hawking radiation made him a scientific superstar.

It was, said Declan Fahy , a communications professor who studies scientists as celebrities and public intellectuals, "a signature contribution to cosmology [just] as the field became the most exciting place in physics."

Years later, Hawking would say that black holes do not have "event horizons," or points of no return, and that one of space's most mysterious objects may need rethinking. (See " No Black Holes Exist, Says Stephen Hawking—At Least Not Like We Think .")

Early Years

Stephen William Hawking was born in Oxford, England, on January 8, 1942, a date that he often noted was exactly 300 years after the death of Galileo. The first of four children of Oxford University graduates Isobel and Frank Hawking, he grew up in a prodigiously intellectual family that read books at the dinner table and that he later described as "slightly eccentric."

His father, a noted researcher on tropical diseases, wanted his son to go into medicine; young Hawking was drawn to the stars. Hawking attended St. Alban's School and Oxford, where he studied cosmology and fought off boredom before graduating with honors.

He went on to Cambridge for his doctorate, earning it in 1966, three years after receiving the devastating diagnosis of ALS at age 21 and being given two and a half years to live.

The scientist would credit his relationship with Jane Wilde, whom he met shortly before his diagnosis, with giving him a reason to live. The couple married in 1965 and had three children, who survive him.

But the strain of being her husband's caregiver even as he became a worldwide phenomenon took a toll, and they divorced after 25 years of marriage. Hawking soon married one of his nurses, Elaine Mason. That marriage, tainted by allegations (later dismissed by police) that his second wife was abusive, also ended in divorce.

Later Celebrity

Hawking became an international celebrity in 1988 when his book, A Brief History of Time , was published. A layman's guide to the universe that explains complex mathematics and concepts in terms non-scientists can understand, it sold more than ten million copies and made him a household name.

In the years that followed, Steven Spielberg produced the film version while its author appeared in a string of films and TV shows, including a six-part series, Stephen Hawking's Universe. He played a hologram of himself on Star Trek: The Next Generation and an animated character in the Simpsons .

Hawking's franchise wasn't based solely on his work, though he'd already been elected at age 32 to Britain's prestigious Royal Society. "Because of his physical appearance," Fahy said, "he became a symbol of pure intellect, an image journalists recycled over and over again. That image connected with people around the world."

It also dismayed many of Hawking's fellow physicists, who considered comparisons to Einstein to be "over the top."

He was "a symbol of the overcoming of great difficulty, and that, obviously, you have to admire," said Virginia Trimble , an astronomer at the University of California, Irvine, who was a fellow student at Cambridge. "But I think the work would not have raised him as high in the pantheon if he'd done it as someone who could go out skiing every weekend."

Hawking himself acknowledged that he "fit the stereotype of a disabled genius," though he never let his wheelchair slow him down. He traveled the world giving lectures, always accompanied by a retinue of caregivers. At Cambridge, he held the Lucasian Professorship of Mathematics, Isaac Newton's former chair, and was director of research at the university's Center for Theoretical Cosmology.

In later years, Hawking completely lost his ability to speak after a bout of pneumonia necessitated a tracheotomy. Communicating took longer and longer. Toward the end, he could form just one word per minute using a speech-generating device controlled by his right cheek muscle. Fears that Hawking's brilliance would soon be "locked in" his body prompted efforts to find ways to preserve his ability to express himself.

Before his final decline, Hawking wrote on his website about the voice synthesizer that kept him connected to the world.

"It is the best I have heard," he wrote, "although it gives me an accent that has been described variously as Scandinavian, American or Scottish."

Related Topics

- BLACK HOLES

- SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

You May Also Like

The Belgian city where the Big Bang theory was born

This is what the first stars looked like as they were being born

Limited time offer.

Get a FREE tote featuring 1 of 7 ICONIC PLACES OF THE WORLD

What is the multiverse—and is there any evidence it really exists?

Step inside the factory where the NFL’s footballs are made

How hitchhiking through America spurred a love of desert walking for author Geoff Nicholson

The true history of Einstein's role in developing the atomic bomb

The Ghanaian-British poet Nii Ayikwei Parkes discovers the dark secrets of his ancestral Caribbean homeland, in Guadeloupe

- Paid Content

- Environment

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Women of Impact

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Advertisement

Comment and Physics

A brief history of stephen hawking: a legacy of paradox.

By Stuart Clark

14 March 2018

Gemma Levine/Getty

Stephen Hawking, the world-famous theoretical physicist, has died at the age of 76.

Hawking’s children, Lucy, Robert and Tim said in a statement: “We are deeply saddened that our beloved father passed away today.

“He was a great scientist and an extraordinary man whose work and legacy will live on for many years. His courage and persistence with his brilliance and humour inspired people across the world.

“He once said: ‘It would not be much of a universe if it wasn’t home to the people you love.’ We will miss him for ever.”

Stephen Hawking dies aged 76

Tributes flow in following the death of world-famous theoretical physicist stephen hawking.

The most recognisable scientist of our age, Hawking holds an iconic status. His genre-defining book, A Brief History of Time , has sold more than 10 million copies since its publication in 1988, and has been translated into more than 35 languages. He appeared on Star Trek: The Next Generation , The Simpsons and The Big Bang Theory . His early life was the subject of an Oscar-winning performance by Eddie Redmayne in the 2014 film The Theory of Everything . He was routinely consulted for oracular pronouncements on everything from time travel and alien life to Middle Eastern politics and nefarious robots . He had an endearing sense of humour and a daredevil attitude – relatable human traits that, combined with his seemingly superhuman mind, made Hawking eminently marketable.

But his cultural status – amplified by his disability and the media storm it invoked – often overshadowed his scientific legacy. That’s a shame for the man who discovered what might prove to be the key clue to the theory of everything , advanced our understanding of space and time, helped shape the course of physics for the last four decades and whose insight continues to drive progress in fundamental physics today.

Beginning with the big bang

Hawking’s research career began with disappointment. Arriving at the University of Cambridge in 1962 to begin his PhD, he was told that Fred Hoyle , his chosen supervisor, already had a full complement of students. The most famous British astrophysicist at the time, Hoyle was a magnet for the more ambitious students. Hawking didn’t make the cut. Instead, he was to work with Dennis Sciama, a physicist Hawking knew nothing about. In the same year, Hawking was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a degenerative motor neurone disease that quickly robs people of the ability to voluntarily move their muscles. He was told he had two years to live.

Although Hawking’s body may have weakened, his intellect stayed sharp. Two years into his PhD, he was having trouble walking and talking, but it was clear that the disease was progressing more slowly than the doctors had initially feared. Meanwhile, his engagement to Jane Wilde – with whom he later had three children, Robert, Lucy and Tim – renewed his drive to make real progress in physics.

Stephen and Lucy Hawking

James Veysey/Camera Press

Working with Sciama had its advantages. Hoyle’s fame meant that he was seldom in the department, whereas Sciama was around and eager to talk. Those discussions stimulated the young Hawking to pursue his own scientific vision. Hoyle was vehemently opposed to the big bang theory (in fact, he had coined the name “big bang” in mockery). Sciama, on the other hand, was happy for Hawking to investigate the beginning of time.

Time’s arrow

Hawking was studying the work of Roger Penrose , which proved that if Einstein’s general theory of relativity is correct, at the heart of every black hole must be a point where space and time themselves break down – a singularity. Hawking realised that if time’s arrow were reversed, the same reasoning would hold true for the universe as a whole. Under Sciama’s encouragement, he worked out the maths and was able to prove it: the universe according to general relativity began in a singularity.

Hawking was well aware, however, that Einstein didn’t have the last word. General relativity, which describes space and time on a large scale, doesn’t take into account quantum mechanics , which describes matter’s strange behaviour at much smaller scales. Some unknown “theory of everything” was needed to unite the two. For Hawking, the singularity at the universe’s origin did not signal the breakdown of space and time; it signalled the need for quantum gravity .

Luckily, the link that he forged between Penrose’s singularity and the singularity at the big bang provided a key clue for finding such a theory. If physicists wanted to understand the origin of the universe, Hawking had just shown them exactly where to look: a black hole .

Black holes were a subject ripe for investigation in the early 1970s. Although Karl Schwarzschild had found such objects lurking in the equations of general relativity back in 1915, theoreticians viewed them as mere mathematical anomalies and were reluctant to believe they could actually exist.

Albeit frightening, their action is reasonably straightforward: black holes have such strong gravitational fields that nothing, not even light, can escape their grip. Any matter that falls into one is forever lost to the outside world. This, however, is a dagger in the heart of thermodynamics.

Stephen Hawking's final theorem turns time and causality inside out

In his final years, Stephen Hawking tackled the question of why the universe appears fine-tuned for life. His collaborator Thomas Hertog explains the radical solution they came up with

Thermodynamic threat

The second law of thermodynamics is one of the most well-established laws of nature. It states that the entropy, or level of disorder in a system, always increases. The second law gives form to the observation that ice cubes will melt into a puddle, but a puddle of water will never spontaneously turn into a block of ice. All matter contains entropy, so what happens when it is dropped into a black hole? Is entropy lost along with it? If so, the total entropy of the universe goes down and black holes would violate the second law of thermodynamics.

Hawking thought that this was fine. He was happy to discard any concept that stood in the way to a deeper truth. And if that meant the second law, then so be it.

Bekenstein and breakthrough

But Hawking met his match at a 1972 physics summer school in the French ski resort of Les Houches, France. Princeton University graduate student Jacob Bekenstein thought that the second law of thermodynamics should apply to black holes too. Bekenstein had been studying the entropy problem and had reached a possible solution thanks to an earlier insight of Hawking’s .

A black hole hides its singularity with a boundary known as the event horizon. Nothing that crosses the event horizon can ever return to the outside. Hawking’s work had shown that the area of a black hole’s event horizon never decreases over time. What’s more, when matter falls into a black hole, the area of its event horizon grows.

Bekenstein realised this was key to the entropy problem. Every time a black hole swallows matter, its entropy appears to be lost, and at the same time, its event horizon grows. So, Bekenstein suggested, what if – to preserve the second law – the area of the horizon is itself a measure of entropy?

Hawking immediately disliked the idea and was angry that his own work had been used in support of a concept so flawed. With entropy comes heat, but the black hole couldn’t be radiating heat – nothing can escape its pull of gravity. During a break from the lectures, Hawking got together with colleagues Brandon Carter, who also studied under Sciama, and James Bardeen, of the University of Washington, and confronted Bekenstein.

The disagreement bothered Bekenstein. “These three were senior people. I was just out of my PhD. You worry whether you are just stupid and these guys know the truth,” he recalls.

Back in Cambridge, Hawking set out to prove Bekenstein wrong. Instead, he discovered the precise form of the mathematical relationship between entropy and the black hole’s horizon. Rather than destroying the idea, he had confirmed it. It was Hawking’s greatest breakthrough.

Hawking radiation

Hawking now embraced the idea that thermodynamics played a part in black holes. Anything that has entropy, he reasoned, also has a temperature – and anything that has a temperature can radiate.

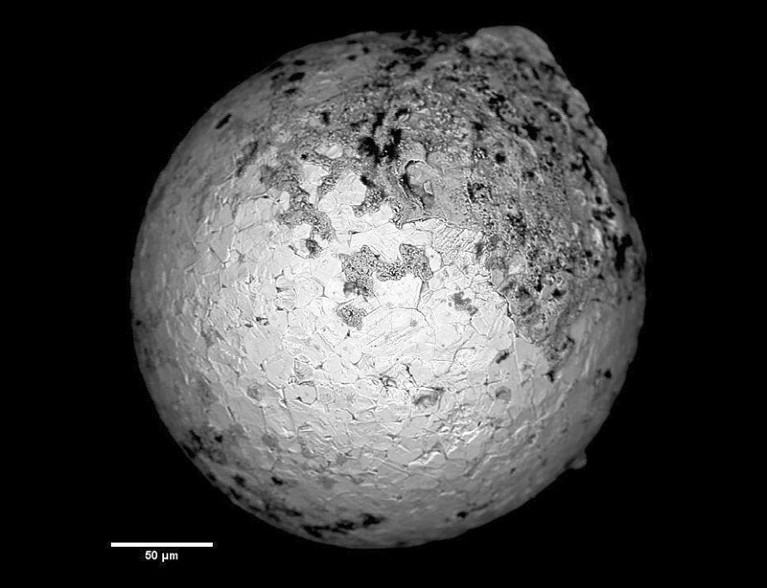

His original mistake, Hawking realised, was in only considering general relativity, which says that nothing – no particles, no heat – can escape the grip of a black hole. That changes when quantum mechanics comes into play. According to quantum mechanics, fleeting pairs of particles and antiparticles are constantly appearing out of empty space, only to annihilate and disappear in the blink of an eye. When this happens in the vicinity of an event horizon, a particle-antiparticle pair can be separated – one falls behind the horizon while one escapes, leaving them forever unable to meet and annihilate. The orphaned particles stream away from the black hole’s edge as radiation. The randomness of quantum creation becomes the randomness of heat.

“I think most physicists would agree that Hawking’s greatest contribution is the prediction that black holes emit radiation,” says Sean Carroll , a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology. “While we still don’t have experimental confirmation that Hawking’s prediction is true, nearly every expert believes he was right.”

Experiments to test Hawking’s prediction are so difficult because the more massive a black hole is, the lower its temperature. For a large black hole – the kind astronomers can study with a telescope – the temperature of the radiation is too insignificant to measure. As Hawking himself often noted, it was for this reason that he was never awarded a Nobel Prize. Still, the prediction was enough to secure him a prime place in the annals of science, and the quantum particles that stream from the black hole’s edge would forever be known as Hawking radiation .

Some have suggested that they should more appropriately be called Bekenstein-Hawking radiation, but Bekenstein himself rejects this. “The entropy of a black hole is called Bekenstein-Hawking entropy, which I think is fine. I wrote it down first, Hawking found the numerical value of the constant, so together we found the formula as it is today. The radiation was really Hawking’s work. I had no idea how a black hole could radiate. Hawking brought that out very clearly. So that should be called Hawking radiation.”

Theory of everything

The Bekenstein-Hawking entropy equation is the one Hawking asked to have engraved on his tombstone. It represents the ultimate mash-up of physical disciplines because it contains Newton’s constant, which clearly relates to gravity; Planck’s constant, which betrays quantum mechanics at play; the speed of light, the talisman of Einstein’s relativity; and the Boltzmann constant, the herald of thermodynamics.

The presence of these diverse constants hinted at a theory of everything, in which all physics is unified. Furthermore, it strongly corroborated Hawking’s original hunch that understanding black holes would be key in unlocking that deeper theory.

Hawking’s breakthrough may have solved the entropy problem, but it raised an even more difficult problem in its wake. If black holes can radiate, they will eventually evaporate and disappear. So what happens to all the information that fell in? Does it vanish too? If so, it will violate a central tenet of quantum mechanics. On the other hand, if it escapes from the black hole, it will violate Einstein’s theory of relativity. With the discovery of black hole radiation, Hawking had pit the ultimate laws of physics against one another. The black hole information loss paradox had been born.

Hawking staked his position in another ground-breaking and even more contentious paper entitled Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse, published in Physical Review D in 1976. He argued that when a black hole radiates away its mass, it does take all of its information with it – despite the fact that quantum mechanics expressly forbids information loss. Soon other physicists would pick sides, for or against this idea, in a debate that continues to this day. Indeed, many feel that information loss is the most pressing obstacle in understanding quantum gravity.

“Hawking’s 1976 argument that black holes lose information is a towering achievement, perhaps one of the most consequential discoveries on the theoretical side of physics since the subject was invented,” says Raphael Bousso of the University of California, Berkeley.

By the late 1990s, results emerging from string theory had most theoretical physicists convinced that Hawking was wrong about information loss, but Hawking, known for his stubbornness, dug in his heels. It wasn’t until 2004 that he would change his mind. And he did it with flair – dramatically showing up at a conference in Dublin and announcing his updated view : black holes cannot lose information.

Today, however, a new paradox known as the firewall has thrown everything into doubt (see “Hawking’s paradox”, below). It is clear that the question Hawking raised is at the core of the quest for quantum gravity.

“Black hole radiation raises serious puzzles we are still working very hard to understand,” says Carroll . “It’s fair to say that Hawking radiation is the single biggest clue we have to the ultimate reconciliation of quantum mechanics and gravity, arguably the greatest challenge facing theoretical physics today.”

Hawking’s legacy, says Bousso, will be “having put his finger on the key difficulty in the search for a theory of everything”.

Hawking continued pushing the boundaries of theoretical physics at a seemingly impossible pace for the rest of his life. He made important inroads towards understanding how quantum mechanics applies to the universe as a whole, leading the way in the field known as quantum cosmology. His progressive disease pushed him to tackle problems in novel ways, which contributed to his remarkable intuition for his subject. As he lost the ability to write out long, complicated equations, Hawking found new and inventive methods to solve problems in his head, usually by reimagining them in geometric form. But, like Einstein before him, Hawking never produced anything quite as revolutionary as his early work.

“Hawking’s most influential work was done in the 1970s, when he was younger,” says Carroll, “but that’s completely standard even for physicists who aren’t burdened with a debilitating neurone disease.”

Stephen Hawking's black hole paradox may finally have a solution

Black holes may not destroy all information about what they were originally made of, according to a new set of quantum calculations, which would solve a major physics paradox first described by Stephen Hawking

Hawking the superstar

In the meantime, the publication of A Brief History of Time catapulted Hawking to cultural stardom and gave a fresh face to theoretical physics. He never seemed to mind. “In front of the camera, Hawking played the character of Hawking. He seemed to play with his cultural status,” says Hélène Mialet, an anthropologist from the University of California, Berkeley, who courted controversy in 2012 with the publication of her book Hawking Incorporated. In it, she investigated the way the people around Hawking helped him build and maintain his public image .

That public image undoubtedly made his life easier than it might otherwise have been. As Hawking’s disease progressed, technologists gladly provided increasingly complicated machines to allow him to communicate. This, in turn, let him continue doing the thing for which he should ultimately be remembered: his science.

“Stephen Hawking has done more to advance our understanding of gravitation than anyone since Einstein,” Carroll says. “He was a world-leading theoretical physicist, clearly the best in the world for his time among those working at the intersection of gravity and quantum mechanics, and he did it all in the face of a terrible disease. He is an inspirational figure, and history will certainly remember him that way.”

Hawking's paradox

In 2012, four physicists at the University of California, Santa Barbara – Ahmed Almheiri, Donald Marolf, Joseph Polchinski and James Sully, known collectively by physicists as AMPS – shocked the physics community with the results of a thought experiment .

When pairs of particles and antiparticles spawn near a black hole's event horizon, each pair shares a connection called entanglement. But what happens to this link and the information it holds when one of the pair falls in, leaving its twin to become a particle of Hawking radiation (see main story)?

One school of thought holds that the information is preserved as the hole evaporates, and that it is placed into subtle correlations among these particles of Hawking radiation.

But, AMPS asked, what does it look like to observers inside and outside the black hole? Enter Alice and Bob.

According to Bob, who remains outside the black hole, that particle has been separated from its antiparticle partner by the horizon. In order to preserve information, it must become entangled with another particle of Hawking radiation.

But what's happening from the point of view of Alice, who falls into the black hole? General relativity says that for a free-falling observer, gravity disappears, so she doesn't see the event horizon. According to Alice, the particle in question remains entangled with its antiparticle partner, because there is no horizon to separate them. The paradox is born.

So who is right? Bob or Alice? If it's Bob, then Alice will not encounter empty space at the horizon as general relativity claims. Instead she will be burned to a crisp by a wall of Hawking radiation – a firewall. If it's Alice who's right, then information will be lost, breaking a fundamental rule of quantum mechanics. "The fervent controversy surrounding Hawking's paradox reflects the stakes his work has raised: in quantising gravity, what gives? And how much?" says Raphael Bousso of the University of California, Berkeley. The answer awaits us in the theory of everything. Amanda Gefter

Article amended on 14 March 2018

- Stephen Hawking

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

The sun could contain a tiny black hole that formed in the big bang

Subscriber-only

Stephen Hawking’s parting shot is a fresh challenge to cosmologists

Stephen hawking memoir: 'an iron man in a frail man's facade', popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Stephen Hawking

Toggle-div#toggle"> 1940s: birth and childhood.

It is a curious fact that Stephen William Hawking was born on 8th January 1942, exactly 300 years after the death of the Italian astronomer, Galileo Galilei. Perhaps it seems a fitting symmetry. Often referred to as ‘the father of observational astronomy,’ Galileo was one of Stephen’s inspirations during his long career as a theoretical physicist and cosmologist.

Stephen was born in Oxford during WWII, the eldest of four children to parents Dr Frank Hawking and Eileen Isobel Hawking. With his siblings, Stephen had a happy childhood mostly spent in Highgate, London and then in St. Albans, Hertfordshire. Stephen admitted to being a late developer and recalled that he was never more than halfway up the class at St Albans School. However, he developed an early curiosity as to how things work, saying later, ‘If you understand how the universe operates, you control it, in a way.’ His classmates called him ‘Einstein’ as they clearly saw the signs of genius in him, missed by his teachers. While still at school, Stephen speculated about the origin of the universe with his friends and wondered whether God created it – “I wanted to fathom the depths of the universe.” This spirit of enquiry set the pattern for his academic career.

toggle-div#toggle"> 1960s: graduation from Oxford and the move to Cambridge

Somewhat reluctantly, Stephen agreed to apply to his father’s college, University College, Oxford . Stephen wanted to read mathematics but his father, tropical medicine specialist Dr Frank Hawking, was adamant that there would be no jobs for mathematicians and Stephen should read medicine. They compromised on Natural Sciences and Stephen went up to Oxford at the young age of 17 in 1959. Despite claiming to do very little work, Stephen performed well enough in his written examinations to be called for a ‘viva’ (an interview) to determine which class of degree he should receive. Stephen told the examiners that if they awarded him a first-class degree he would leave Oxford and go to Cambridge but if he got a second, he would stay in Oxford. They duly gave him a first, as of course, he hoped they would. Stephen went to Trinity Hall, Cambridge in 1962. However, while still an undergraduate, Stephen had begun to realise all was not well. He had become increasingly clumsy, was struggling with small tasks such as doing up his shoelaces and his movements were erratic and ungainly. After an accident at a skating lake in St Albans, his mother took him to Guy’s Hospital in London for tests. Soon after Stephen’s 21st birthday, these tests showed he had a progressive and incurable illness. These tests were exhaustive although primitive by today’s standards. Even after these were completed, oddly Stephen was not told his diagnosis. Eventually, he discovered he had motor neurone disease which slowly and inexorably erodes muscle control but leaves the brain intact. He was given only two years to live. Stephen later recalled that he became desperately demoralised at this time but he did find two sources of inspiration and solace: the intense music of Wagner (a subsequent lifelong passion) and falling in love with Jane Wilde, the woman who would become his wife. The young couple vowed to fight Stephen’s illness together. Stephen now had someone to live for, and in the manner typical of his stubbornness, he threw himself into his research – “To my surprise I found I liked it”, he said later.

Despite his renewed enthusiasm, Stephen’s early career progressed erratically. In Cambridge, he had hoped to study under the most famous astronomer of the time, Fred Hoyle, but Professor Hoyle had too many students already and sent him to physicist and cosmologist Dennis Sciama instead. Later, Stephen recognised this as a piece of luck which laid the foundation of his later career and said that he would have been unlikely to flourish under Hoyle’s supervision. In fact, the two clashed in public in 1964 when Stephen interrupted Fred Hoyle, during a lecture, to tell the famous scientist he had got something wrong. When Hoyle asked how he knew this, Stephen said, ‘Because I have worked it out’. Sciama also introduced Stephen to Roger Penrose in 1965 when Penrose gave a talk on singularity theorems in Cambridge. In that same year, Stephen received his Ph.D for his thesis entitled ‘Properties of Expanding Universes.’ This thesis was released in 2017 on the University of Cambridge’s website, causing the site to crash almost immediately due to the extraordinarily high demand.

In 1965, Stephen applied for a research fellowship at Gonville & Caius College in Cambridge and was accepted. He was to remain a fellow there for the rest of his life. Marriage to Jane and children followed; Robert (1967), Lucy (1970) and Timothy (1979). Supported and cared for by his wife, his loyal PhD students, friends, family, colleagues and his children, Stephen settled into day to day academic life, and continued working right up until his death in March 2018.

toggle-div#toggle"> Mid-60s to early-70s: serious career work

The accolades began. In 1966 Stephen won the Adams Prize for his essay entitled, ‘Singularities and the Geometry of Space-Time’, and which formed the basis for his first academic book, co-authored with George Ellis, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time . This book remains in print today.

In 1969, during a trip to the USA, Stephen observed Joseph Weber’s early and rudimentary experiments for detecting gravitational waves. Stephen would have loved to conduct his own experiments in this new and exciting scientific area but understood that his disability was a barrier in that era. As ever, Stephen made an advantage out of what other people would perceive as a setback, arguing that a theorist can conclude an argument in an afternoon: an experiment can take years. “I was glad I remained a theorist”, he admitted afterwards.

Against the background of increasing and fervent scientific discovery, Stephen began working on the basic laws that govern the universe – the field he had been obsessed with since he was a young schoolboy. Since their first meeting in 1965, Stephen and Roger Penrose had many discussions about singularity theorems which culminated in their joint paper in 1970. In that paper, Stephen showed that Einstein’s general theory of relativity implied space and time would have a beginning in the Big Bang and an end in black holes. Together, Hawking and Penrose developed a singularity theorem proving this theory and this led to Stephen’s ensuing fascination with black holes. His subsequent work in this area laid the foundations for today’s understanding of the universe and how it began.

toggle-div#toggle"> 1970s: ‘I was writing the rulebook for black holes’

The 1970s were a prolific period of work. In 1970, shortly after the birth of his daughter and in a ‘eureka’ moment, Stephen realized, almost in an instant: ● that when black holes merge, the surface area of the final black hole must exceed the sum of the areas of the initial black holes, ● that this places limits on the amount of energy that can be carried away by gravitational waves in such a merger, ● there are parallels to be drawn between the laws of thermodynamics and the behaviour of black holes.

In 1973, and at a bit of a loose end after the publication of his first book, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time , Stephen decided the next step in his research would be to combine general relativity (the theory of the very large) with quantum theory (the theory of the very small). To his disbelief, it seemed that emissions could emanate from a black hole, that particles could escape, i.e. ‘radiate’ from a black hole’s event horizon, a revolutionary quantum effect that appeared to make a mockery of the laws of physics. This research was published in 1974 by Nature as ‘Black hole explosions?’ . However, when announced at a conference in Oxford, his theory was seen as controversial and angrily disputed. Now widely accepted and known as Hawking radiation , Stephen’s proposal unifies the seemingly impossible – general relativity with quantum theory, the large with the small.

Despite their names becoming joined in a formula, Stephen and Jacob Bekenstein never actually worked together. In 1972, Bekenstein proposed that black holes have an entropy. Bekenstein had a formula for entropy that said the entropy was proportional to the area of the event horizon but his numerical co-efficient was incorrect. Stephen did not believe this because black holes were thought to have zero temperatures. It was not until Stephen discovered black hole temperature that he came to believe that black holes have entropy. Stephen was able thereby to confirm the idea that black holes have entropy and fix the coefficient in Bekenstein’s formula.

S = Entropy A = The area of the horizon c = The speed of light G = Newton’s constant of gravitation k = Boltzmann’s constant ħ = Planck’s constant

Stephen’s equation reveals a ‘deep and previously unexpected relationship between gravity and thermodynamics, the science of heat’. But it also raises questions – where does the information about the previously existing matter go when matter ‘disappears’ into a hole? And if information is lost, this is incompatible with quantum mechanics at least in its usual form. This is Stephen’s black hole ‘Information Paradox’ that violates a fundamental tenet of quantum mechanics and has led to decades of furious debate.

The late 1970s were a golden age for Stephen’s academic career and for the field of theoretical physics in general. After being promoted to Reader in Gravitational Physics at Cambridge in 1975, and subsequently Professor of Gravitational Physics in 1977, in 1979 he was appointed as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics , a position he held until 2009. The chair was founded in 1663 with money left in the will of the Reverend Henry Lucas who had been the Member of Parliament for the University. Previously held by Isaac Newton in 1669, this chair was awarded to Stephen in recognition of his ground-breaking scientific work on black holes. In 1979 Stephen was also awarded the first, prestigious Albert Einstein medal, in recognition of ‘scientific findings, works or publications related to Albert Einstein’. This was a period of intense speculation in physics and growing public interest in black holes. Journalists for print and television regularly interviewed Stephen - his name was becoming known.

toggle-div#toggle"> 1980s: A health crisis, and authorial success

Stephen sought to understand the whole universe in scientific terms. As he said famously, ‘My goal is simple. It is a complete understanding of the universe.’ The singularity theorems proved by Stephen and Penrose had shown conclusively that the universe had a beginning in a Big Bang. But the singularity theorems did not say how the universe had begun. Rather, they showed something more sweeping: Einstein’s general relativity breaks down at the Big Bang, and quantum theory becomes important. Working with Jim Hartle, Stephen set out to use the techniques he had developed to understand the quantum dynamics of black holes, to describe the quantum birth of the universe. Stephen first put forward a proposal along these lines at a conference in the Vatican in 1981, where he suggested that the universe began with four space dimensions curled up as a sphere, without any boundary, which through a quantum transition gave rise to the universe with three space dimensions and one time dimension that we have today. Asking what came before the Big Bang, he famously said, `is like asking what lies South of the South Pole’. Stephen and Hartle aptly called their model the no boundary wave function, or no boundary proposal, the first scientific model of the origin of the universe.

Stephen continued to study the no boundary proposal throughout his career. He discovered that there was a profound connection between the no boundary wave function and cosmic inflation – the idea that our universe started with a rapid burst of expansion. In a series of papers over many years Stephen and his students consolidated this connection, showing that the no boundary proposal predicts an early period of inflation. But the scientific importance of the no boundary proposal is not just as a successful theory of the origin of the basic structure of the universe. Perhaps even more important is the impact it has had on how we think about the universe, and our place in it. The no boundary proposal describes an ensemble of universes. Working with Thomas Hertog, Stephen showed this leads to what he called a `top-down approach to cosmology’, reconstructing the universe’s history backwards in time starting from our position within it. ‘The history of the universe depends on the question we ask,’ he used to say.