Unethical Leadership: Review, Synthesis and Directions for Future Research

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2022

- Volume 183 , pages 511–550, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sharfa Hassan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2828-4212 1 ,

- Puneet Kaur 2 , 3 ,

- Michael Muchiri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6816-8350 4 ,

- Chidiebere Ogbonnaya 5 &

- Amandeep Dhir 3 , 6 , 7

39k Accesses

22 Citations

70 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The academic literature on unethical leadership is witnessing an upward trend, perhaps given the magnitude of unethical conduct in organisations, which is manifested in increasing corporate fraud and scandals in the contemporary business landscape. Despite a recent increase, scholarly interest in this area has, by and large, remained scant due to the proliferation of concepts that are often and mistakenly considered interchangeable. Nevertheless, scholarly investigation in this field of inquiry has picked up the pace, which warrants a critical appraisal of the extant research on unethical leadership. To this end, the current study systematically reviews the existing body of work on unethical leadership and offers a robust and multi-level understanding of the academic developments in this field. We organised the studies according to various themes focused on antecedents, outcomes and boundary conditions. In addition, we advance a multi-level conceptualisation of unethical leadership, which incorporates macro, meso and micro perspectives and, thus, provide a nuanced understanding of this phenomenon. The study also explicates critical knowledge gaps in the literature that could broaden the horizon of unethical leadership research. On the basis of these knowledge gaps, we develop potential research models that are well grounded in theory and capture the genesis of unethical leadership under our multi-level framework. Scholars and practitioners will find this study useful in understanding the occurrence, consequences and potential strategies to circumvent the negative effects of unethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why Does Unethical Behavior in Organizations Occur?

Developing a framework for ethical leadership.

Alan Lawton & Iliana Páez

The Value of Autoethnography in Leadership Studies, and its Pitfalls

Jan Deckers

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The contemporary business landscape is witnessing staggering levels of unethical conduct that has strikingly surfaced at the bottom-line figures with estimated total losses worth US$42 billion reported by PwC's Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey ( 2020 ). Interestingly, the contributions of top management in various unethical practices account for over 26% which includes some of the costliest instances of fraud producing not only financial impacts for organisations but also emotional and psychological impacts for their stakeholders (PwC, 2020 ). While sufficient evidence also indicates that top management exhibits serious concerns for business integrity in terms of complying with rules and regulations, behaving responsibly towards various stakeholder groups and maintaining high moral standards (Earnest &Young, 2020 ), the trajectory of corporate scandals continues to increase at a more rapid rate than ever before (Mishra et al., 2021 ), and reciprocal dynamism is witnessed among ‘bad apples’ and ‘bad barrels’(Cialdini et al., 2021 ). Accordingly, corporate leaders, along with the cultures they foster within organisations, work in a vicious cycle wherein one reinforces the other to establish a breeding ground for profound and severe unethical practices. Unsurprisingly, therefore, more than 50% of companies globally experience a minimum of six fraud incidents per year, with another 50% not reporting or investigating the worst incidents (PwC, 2020 ). Hence, unethical leadership is at the intersection of immoral, illegal leadership practices and the unethical climate that further strengthens such leadership. Whether bad apples promote bad barrels or bad barrels host bad apples, the contemporary line of discourse in leadership is increasingly realising the consequential nature of unethical leadership.

Unethical leadership is conceptualised as leader behaviours and decisions that are not only anti-moral but most often illegal and exhibit an outrageous intent to instigate unethical behaviours among followers (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 ). Unethical leadership has long been documented to cause a deleterious impact on organisations. For example, the famous emissions scandal of Volkswagen, known as ‘Dieselgate’, cost the company an estimated US$63 billion (Jung & Sharon, 2019 ). The consequences of this scandal resulted from an interplay of unethical leaders and an unethical organisational culture (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Similar evidence has been reported in another famous case involving Enron, where an unethical climate fostered conscious rule breaking within the organisation, which resulted in both reputational and financial consequences (Sims & Brinkmann, 2003 ). This scenario has been accentuated by the growing reporting of corporate misconduct in the mainstream media (Chen, 2010a ), which has heightened the interest of scholars in this direction.

Research into unethical leadership has largely focused on the aftermath that accompanies organisation leaders’ morally inappropriate and legally unacceptable behaviours that are directed towards the organisation and followers (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Scholars have gauged the impact of unethical leadership in the domains of employee attitudes, e.g. intentions to stay (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ) and intentions to engage in fraudulent acts (Johnson et al., 2017 ), and employee behaviours, e.g. counterproductive work behaviours (Knoll et al., 2017 ), crimes of obedience (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, 2013 ) and knowledge hiding (Qin et al., 2021 ), among others. Recently, scholars have begun to investigate the team- or group-level ( b ; Cialdini et al., 2021 ; Peng, Schaubroeck, et al., 2019 ) and organisational-level consequences (Mujkic & Klingner, 2019 ; Sherif et al., 2016 ; Vasconcelos, 2015 ) of this phenomenon; however, such investigations remain scant.

An important trend in recent years is the interchangeable use of various measures, conceptualisations and terminologies, which has, by and large, confused the research space on unethical leadership. In fact, concepts such as destructive leadership and its offshoot abusive supervision have dominated this area (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and research pertaining solely to unethical leadership has received extremely limited attention. Given the rampant proliferation of measures and concepts, both the empirical and conceptual distinctiveness of unethical leadership has been blurred (Ünal et al., 2012 ). Furthermore, a dispute over the distinction between unethical and ethical leadership has distorted the conceptual underpinnings of both concepts. Some scholars treat unethical leadership as the flipside of ethical leadership and equate the absence of exemplary leader behaviours with the presence of unethical leadership. However, others have challenged this notion, asserting a quantitative distinction between unethical and ethical leadership styles, which requires separate lines of academic inquiry (Gan et al., 2019 ). Ünal et al. ( 2012 ) captured this view, demonstrating that a single occurrence of dysfunctional leader behaviour does not amount to unethical leadership.

Despite the consequential and distinctive nature of unethical leadership, scholars have made few attempts to systematically organise the literary work in this field and thereby facilitate a comprehensive understanding of unethical leadership from an academic perspective. One of the earliest scholarly investigations in this regard is that of Brown and Mitchell ( 2010 ), who synthesised the academic literature on unethical leadership under the framework of ethical leadership. Their article had an overt focus on ethical leadership within organisations, which they supplemented with unethical perspectives on leadership to broaden the study’s scope. Our review is not only exclusively geared towards unethical leadership but also distinguishes unethical leadership from the absence of ethical behaviours. Furthermore, the early work on unethical leadership does not provide a comprehensive account of the developments in the area, perhaps because this line of literature, as a separate research area, has developed only in the recent past. Thus, we believe that the significant body of research conducted on unethical leadership since Brown and Mitchell’s ( 2010 ) review study needs to be synthesised. Furthermore, Lašáková and Remišová ( 2015 ) enhanced theoretical understanding of unethical leadership by delineating problems in its existing conceptualisations. While their study broadened the concept’s definitional space, it did not account for the extant empirical work in the area. Our study not only distinguishes unethical leadership from related concepts but also provides a detailed view of the empirical work in the area and offers new practical insights into the field.

Apart from the above-discussed rationale, we contend that unethical leadership remains the least researched concept among its academic offshoots. In fact, scholars have thoroughly investigated concepts such as abusive supervision and destructive leadership via both empirical studies and a good number of systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and meta-analyses (Mackey et al., 2017 , 2021 ; Schyns & Schilling, 2013 ; Zhang & Bednall, 2016 ). This points towards the need to examine the extant unethical leadership studies in their own right without confusing them with studies that focus on any of these related concepts. Furthermore, existing SLRs are either too specific or too general and, thus, provide few insights into the area of unethical leadership. For example, studies pertaining exclusively to abusive supervision highlight the verbal and non-verbal abuse leaders direct towards their followers, but these studies offer only a limited understanding of other unethical behaviours, e.g. violations of rules or norms. In the same manner, studies pertaining to destructive leadership examine myriad behaviours that further add to the problematic proliferation of concepts in this research domain (Mackey et al., 2021 ).This underscores an urgent need to re-examine the concept of unethical leadership and the associated literature and thereby facilitate a robust understanding of unethical leadership as a distinct concept.

The current study’s overarching aim is, thus, to conduct an SLR of the extant literature and thereby not only help to synthesise this literature but also identify new issues and broaden the horizon of research in that area by highlighting important knowledge gaps in the existing body of work. Consistent with the above discussion, the present study seeks to address the following research questions (RQs): RQ1 What is the research profile of the relevant extant literature published on unethical leadership? RQ2 What are the dominant focus areas and themes on which most of the academic inquiry has concentrated? RQ3 What are the important knowledge gaps in the existing body of research and potential future research areas that must be investigated to enrich the field?

To address the above research queries, we first extracted the most relevant data with the aid of a robust SLR protocol that has already been validated in a number of studies (Kaur et al., 2021 ; Khan et al., 2021 ; Seth et al., 2020 ; Talwar et al., 2020 ). For RQ1 , we generated the descriptive statistics for the existing research by establishing precise inclusion and exclusion criteria and listing the keywords to search in the most reliable databases. To address RQ2 , we organised all of the shortlisted studies around themes derived from the results of our content analysis. For RQ3 , we identified research gaps and corresponding research questions specific to each emergent theme. To further complement the identified gaps, we developed a multi-level framework of unethical leadership—titled the ‘M3 framework’. Furthermore, we proposed seven potential research models for scholars and practitioners interested in studying unethical leadership. The proposed framework and potential models will be useful for delineating the specific variable relationships scholars can examine in greater detail and from various theoretical lenses to facilitate both conceptual and empirical work in this area. Therefore, these models aim to capture some of the lacunae in the literature.

This SLR is organised into the following sections. In Sect. 2, we examine the conceptual understanding of unethical leadership and make some important distinctions between unethical leadership and other concepts. Section 3, which is devoted to the methodology, explicates the exact protocol we followed to identify the relevant corpus of studies. In this section, we discuss both the data extraction process and the research profile of the sampled studies. In Sect. 4, we discuss the themes that emerged in the coding process as well as the knowledge gaps and potential research questions pertaining to each theme. In Sect. 5, we propose and discuss the conceptual framework and seven potential research models based on gaps identified in Sect. 4. Section 6 provides the practical and theoretical implications of the current study, while Sect. 7 concludes the study by acknowledging its limitations.

Conceptualising Unethical Leadership

Defining unethical leadership.

Contemporary discourse on unethical leadership remains relatively sparse, with only a few studies extensively focused on crystallising the conceptual underpinnings of this leadership type. Brown and Mitchell ( 2010 ) laid the early foundations by offering definitional and conceptual reflections on the phenomenon. They defined unethical leadership ‘ as behaviours conducted and decisions made by organisational leaders that are illegal and/or violate moral standards and those that impose processes and structures that promote unethical conduct by followers ’ (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 , p. 588). The essential tenet of this definition pertains to the leader behaviours that instil unethical conduct in followers. Under this definition, therefore, unethical leadership amounts not only to leaders themselves engaging in unethical behaviours but also enabling and harnessing unethical follower behaviours. Leaders perform these efforts either by overtly demonstrating unethical conduct or passively promoting an unethical climate by ignoring unethical conduct and, thus, allowing unethical behaviours to flourish within organisations (Brown et al., 2005 ).The potential drawback of this definition, however, is its failure to explicitly identify the exact behaviours that could be labelled as unethical. Because morality is a diverse and culturally ingrained phenomenon, the manifestations of unethical behaviours are likewise diverse, which renders unethical leadership a rather relative concept (Resick et al., 2011 ).

To address some of these pitfalls, Ünal et al., ( 2012 ) conducted a seminal study to develop a more robust and comprehensive understanding of unethical leadership. They discussed unethical leadership from normative perspectives and advanced a deeper understanding of the concept by differentiating it from similar leadership styles as well as from the lack of exemplary ethical leader behaviours. Specifically, they defined unethical leadership/supervision as ‘ supervisory behaviours that violate normative standards ’(Ünal et al., 2012 , p.6). Their distinction between unethical leadership and other related concepts, along with the description of precise unethical leadership practices, offers nuanced insights into this research area. In particular, they utilised virtue ethics, deontology, teleology and utilitarian perspectives to develop normative foundations of unethical leadership practices. They identified the violation of employee rights, unfair justice mechanisms, violation of legitimate organisational interests and weak leader character as potential manifestations of unethical leadership. Subsequent research has captured these manifestations of unethical leader behaviour in various cultural contexts. For example, Eisenbeiß and Brodbeck ( 2014 ) examined cross-cultural and cross-sectoral similarities in unethical leadership perceptions. Their comparative research highlighted the interplay of compliance-oriented and value-oriented perspectives within the domain of unethical leadership, and they identified dishonesty, unfair treatment, irresponsible behaviour, non-adherence to rules, laws and regulations, engagement in corruption and other criminal behaviours, an egocentric orientation, manipulative tendencies and a lack of empathy towards followers as the common manifestations of unethical behaviour in various countries.

The above discussion highlights the efforts made, thus, far to clarify what unethical leadership is and what it is not and to define it as a distinct concept rather than merely the opposite of ethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). With research on unethical leadership taking a new direction and scholars investigating distinct yet related concepts more frequently than unethical leadership itself, however, it becomes crucial to highlight unethical leadership as a separate line of inquiry that requires equal attention. In the sections that follow, we discuss some of these concepts and reveal the differences between them and the concept of unethical leadership.

Unethical Leadership and Related Concepts

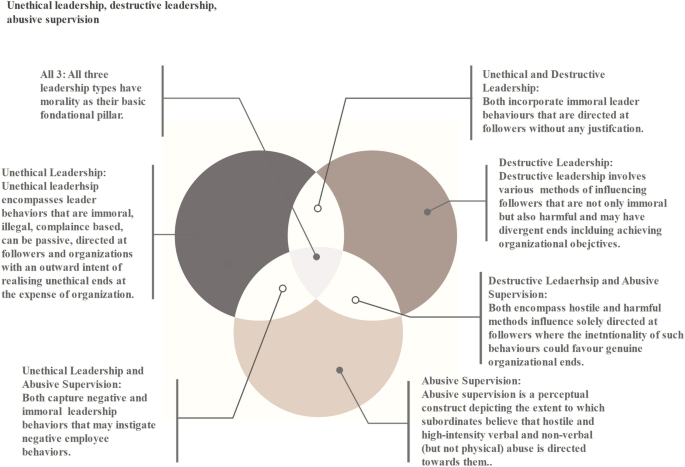

The domain of unethical leadership has witnessed an increasing proliferation of concepts, which has seriously obstructed the meaningful application of findings to unethical leadership research and practice (Tepper & Henle, 2011 ; Ünal et al., 2012 ). For example, scholars have employed concepts including petty tyranny (Ashforth, 1997 ), supervisor undermining (Duffy et al., 2002 ), workplace aggression (Neuman & Baron, 1998 ), despotic leadership (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008 ), abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000 ), destructive leadership (Einarsen et al., 2007 ) and some newer forms, e.g. Machiavellian leadership (Belschak et al., 2018 ), interchangeably. In fact, concepts such as abusive supervision and destructive leadership have received the most scholarly attention and have developed into separate lines of academic inquiry. It is important to mention here that destructive leadership and abusive supervision have been highly influential in the academic literature (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and the remainder of the concepts mentioned above fall under the domain of these two leadership types. Hence, we discuss these two concepts and attempt to differentiate them from unethical leadership. Furthermore, we advance the conceptual distinction between unethical leadership and the absence of ethical leadership/the lack of exemplary ethical behaviours. Figure 1 presents a conceptual overview of the differences between unethical leadership and other forms of leadership styles. Before discussing these, we provide a brief conceptual understanding of unethical leadership and the lack of ethical behaviours.

Overview of conceptual differences between unethical leadership and other forms of leadership styles

Unethical Leadership vs Lack of Ethical Leadership

The dominant discussions on ethical and unethical leadership have recently shifted towards viewing ethical and unethical leadership as distinct concepts that require their own investigation (Gan et al., 2019 ). These concepts are increasingly recognised as quantitatively distinct, with scholars acknowledging that the absence of ethical behaviour does not necessarily amount to unethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). While ethical leadership is ‘ the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships’ (Brown et al., 2005 , p. 120), unethical leadership, as discussed above, incorporates behaviours and decisions that could be illegal or morally unsound (Brown & Mitchell, 2010 ). This suggests that the mechanism that explains the formation of unethical leadership and its consequences is distinct from that of ethical leadership (Gan et al., 2019 ). Therefore, a single instance of dysfunctional leader behaviour does not always equate to unethical leadership (Ünal et al., 2012 ). This understanding has implications for the concept’s operationalisation because simply reverse coding the scale items would fail to accurately reflect an unethical leader’s behaviour. Hence, the present study incorporates research that has explicitly studied unethical leadership. In mining the literature, we specifically sought studies that were focused on unethical leadership and not those where the major theme was the absence of exemplary leader behaviours or ethical failures.

Unethical Leadership vs Destructive Leadership

Destructive leadership is defined as ‘ a process in which over a longer period of time the activities, experiences and/or relationships of an individual or the members of a group are repeatedly influenced by their supervisor in a way that is perceived as hostile and/or obstructive ’ (Schyns & Schilling, 2013 , p. 141) While an overlap appears to exist between unethical and destructive leadership, a fine line separates these concepts. Destructive leadership essentially captures harmful methods of influence directed at followers (Mackey et al., 2021 ), and it includes myriad leader behaviours, such as punishment, leader incivility, leader undermining, leader atrocities, toxic behaviours etc. We argue that although both concepts share the dimension of immorality, unethical leadership also includes behaviours that can be compliance based (Eisenbeiß & Brodbeck, 2014 ). In other words, unethical leadership can also entail behaviours that are illegal and amount to regulatory violations (Javaid et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, we argue that some types of destructive leader behaviours—e.g. tyrannical and insular leadership—can be pro-organisational. While such leadership types override follower interests, leaders pursue them under the guise of organisational interests (Einarsen et al., 2007 ).

In fact, pseudo-transformational leadership, yet another form of destructive leadership, has the potential to yield positive organisational outcomes (Almeida et al., 2021 ). In contrast, unethical leadership includes behaviours that are undeniably illegal and, at the same time, violate moral standards, thus, granting no benefit of the doubt to the intentionality of the leader’s behaviour. It can, thus, be inferred that destructive leadership and its various types employ ‘harmful methods of follower influence’, where the intentionality of such behaviour is subject to interpretation. While unethical leadership may not employ harmful methods of punishment, oppression or committing atrocities, it may reflect in corporate scandals and financial misreporting, among others. Finally, destructive leadership, which essentially includes behaviours that are hostile and obstructive, can originate from other types of leadership that need not be unethical. Even positive leadership types, e.g. ethical leadership, can instigate hostile behaviours with the presence of a curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and positive employee outcomes (Stouten et al., 2013 ).

Unethical Leadership vs Abusive Supervision

Another leading concept in this direction is abusive supervision, which scholars have, at times, categorised under destructive leadership. Abusive supervision is defined as ‘subordinates' perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviours, excluding physical contact ’ (Tepper, 2000 , p. 178). Under this definition, abusive supervision, like destructive leadership, encompasses longitudinal hostile behaviours, but these are limited solely to verbal and non-verbal abuse (i.e. these behaviours exclude physical abuse; Zhang & Bednall, 2016 ). Once again, however, scholars have not explicated the direction of outcomes in the context of abusive supervision, making it a typical category of destructive leadership (Guo et al., 2020 ).

The target of the intended behaviour is another critical point of distinction not only for delineating the scope but also the research framework of the present study. Under abusive supervision, leaders’ demeaning language and derogatory remarks are directed solely at their followers (Tepper, 2000 ). Under unethical leadership, however, different forms of unethical leader behaviours can target both followers and organisations. This confirms the view that abusive supervision is highly psychological in nature, encompassing high-intensity hostile behaviours that are directed at people (Almeida et al., 2021 ). The preceding discussion, however, suggests that unethical leadership need not be highly intense or hostile. Rather, it can entail passive and more subtle as well as legally unacceptable behaviours. This means that unethical leadership, unlike abusive supervision, can be task-oriented. Therefore, corporate scandals and financial misreporting fall under the concept of unethical leadership, and abusive supervision is, thus, conceptually distinct from unethical leadership. Furthermore, abusive supervision entails micro-level interactions between a leader and his or her immediate followers. In contrast, unethical leadership can operate at many levels and is much broader than these interactions between the leader and his or her followers.

The remaining concepts enumerated above, including petty tyranny, supervisor undermining, workplace aggression, despotic leadership, corrupt leadership, evil leadership and derailed leadership, likewise fall under the framework of destructive leadership with minor differences based on intentionality, types of behaviour, perceived versus actual behaviour, the inclusion of outcomes and the persistence of behaviours (Schyns & Schilling, 2013 ; Ünal et al., 2012 ). For example, workplace aggression is a type of destructive leadership wherein leaders direct hostile physical behaviours—e.g. pushing, hitting etc.—towards their followers (Neuman & Baron, 1998 ). Similarly, individuals who exercise Machiavellian leadership do not exhibit persistent hostile behaviours but rather intermittent and situational hostile behaviours towards followers (Belschak et al., 2018 ). It is important to mention here that although these conceptual differences have been delineated, the operational measurement of these concepts is not mutually exclusive, which often renders them interchangeable (Ünal et al., 2012 ). However, the current study treats them as separate concepts and includes only those studies that have examined unethical leadership in its own right without reference to any of these overlapping concepts.

The aim of the present study is to systematically review the extant literature on unethical leadership. Systematic reviews are considered scientific and enable the researcher to identify and critically analyse relevant research in a particular domain. This method of synthesising academic literature has gained acceptance across various disciplines primarily because it enhances research rigour (Dorn et al., 2016 ). In fact, the SLR method has gained wider acceptance in the management literature (Talwar et al., 2020 ) because it provides evidence-informed and reproducible research (Tranfield et al., 2003 ). As we discuss in the following paragraphs, SLRs ensure an audit trail of the decisions taken, which produces transparent, unbiased and objective results with minimum bias (Seth et al., 2020 ).

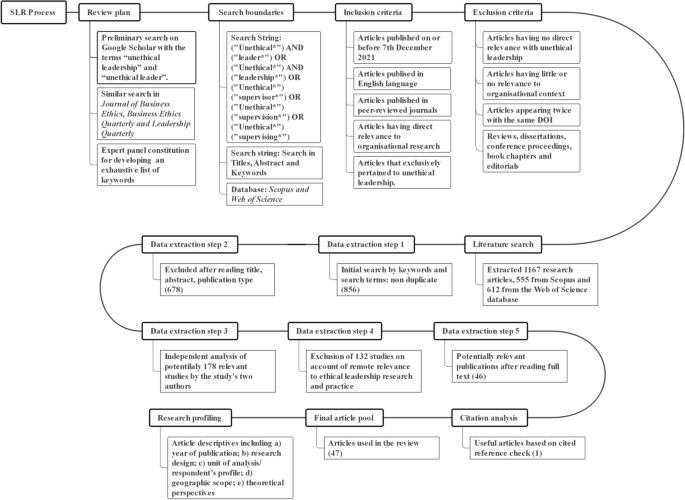

To ensure objectivity throughout the entire process, researchers follow various steps in systematically synthesising the existing body of research in a particular domain; the resulting objectivity in the process, in turn, expands opportunities for replicating as well as extending the work of the SLR (Seth et al., 2020 ; Talwar et al., 2020 ). Consistent with the procedures previous scholars have followed, we employed a four-step sequential process to systematically review research in the area of unethical leadership. We began by planning the review and ended with a descriptive analysis of the sampled studies. We now discuss these steps in detail (see Fig. 2 ).

An overview of the SLR process

Planning the Review

In this step, which aims to obtain the most relevant and greatest number of results, we ran a preliminary search on Google Scholar with the terms ‘unethical leadership’ and ‘unethical leader’. We analysed the first 100 results from this initial search to update the list of keywords that would eventually be used in developing the final corpus of studies. Then, consistent with best practices, we ran a similar search in the leading journals on ethics, including the Journal of Business Ethics , Business Ethics Quarterly and Leadership Quarterly , to ensure that we did not miss any important studies. Recent work in the domain of business ethics has supported the inclusion of these journals (Newman et al., 2020 ). The results from Google Scholar and reputed journals in business and ethics revealed that, by and large, the literature has employed uniform terminology for unethical leadership with a difference of one or two concepts, e.g. unethical supervision and bad leadership. Therefore, to ensure that we used only the most relevant search terms, we constructed a review panel, which consisted of two senior professors and two senior scholars. The panel was assembled with the intent to provide us with critical feedback and appraisal before we finalised each step in the process. After thorough discussions with the panel members, we added ‘unethical supervision’, ‘unethical supervising’ and ‘unethical supervisor’ to the initial list of keywords. Finally, we searched these terms in Scopus and Web of Science databases because these databases have been frequently used in SLRs due to the exhaustive list of journals they host, particularly in social sciences research (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016 ).

Screening Criteria

We established the following inclusion criteria before constructing the dataset for the present study. First, we only included studies that were peer-reviewed and published in the English language on or before 7 December 2021. Second, we included studies that contained the term unethical leadership in any part of the study, including the title, abstract, keywords or text. Third, we only included studies that had direct relevance to organisational research. Fourth, we only included studies that pertained to unethical leadership. In other words, we discarded studies that used synonyms for unethical leadership that are conceptually different from unethical leadership unless otherwise specified. The exclusion criteria caused us to omit those studies that(a) had no direct relevance to unethical leadership; (b) had little or no relevance to the organisational context—e.g. teacher samples, military samples, sports administration; (c) appeared twice with the same DOI and (d) pertained to reviews, dissertations, conference proceedings, book chapters and editorials.

Data Extraction

We used asterisk (*), 'OR' and 'AND' connectors to develop search strings for use in the databases. We retrieved a total of 1167 research articles, 555 from Scopus and 612 from the Web of Science databases. We removed duplicate items, which reduced the initial corpus to 856. These remaining studies were filtered through the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which resulted in the exclusion of 678 studies. It is important to mention here that studies pertaining to abusive supervision, destructive leadership and authentic supervision were excluded for the reasons mentioned in Sect. 2. The two authors then thoroughly and independently analysed the remaining 178 studies. After a comprehensive evaluation of these studies, we decided that another 132 studies should be removed because they were only remotely relevant to ethical leadership research and practice. For example, initially, we had shortlisted pseudo-transformational leadership (Barling et al., 2008 ) as a type of unethical leadership, but after carefully screening the text, we decided that this type of leadership does not directly pertain to the research domain of unethical leadership. This left us with 46studiesin the main dataset of the present study. Finally, we added one paper manually after conducting forward and backward chaining of the references of the 46 shortlisted papers (see Fig. 2 ). Because two authors were independently involved in this process, we assessed interrater reliability (IRR) using the kappa statistic (Landis & Koch, 1977 ), which significantly exceeded the threshold for agreement between the independent coders.

Research Profiling

A comprehensive overview of the extant literature on unethical leadership is presented in Table 1 .This includes (a) year of publication; (b) research design; (c) unit of analysis/respondent profile; (d) geographic scope and (e) theoretical perspectives. The table reveals that research on unethical leadership has progressed, particularly over the past three years. However, much of the research remains concentrated in developed nations, particularly the USA, which poses serious limitations to the generalizability of the results to emerging nations. Most scholars have employed quantitative techniques, including field surveys, laboratory experiments and field experiments, and various quantitative techniques, including structural equation modelling, logistic regression, hierarchical regression and polynomial regression, to enhance the existing understanding and the generalizability of the results. Interestingly, a good number of scholars have utilised multiple surveys in the same study to comprehensively gauge the proposed effects. For example, scholars have often used experiments and questionnaire-based surveys with different respondents in a single study to enhance the reliability and generalizability of their findings.

No consensus exists regarding the best type of scale for capturing unethical leader behaviours. We observed the use of various scales, with some of the studies simply reverse coding the ethical leadership scale items. For example, Cialdini et al. ( 2021 ) reverse coded the scale item, ‘ Sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics ’, so that a higher score represented unethical behaviour. The remainder of the studies employed toxic leadership dimensions (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ) or organisational and interpersonal deviance (Qin et al., 2021 ), or they adapted general unethical organisational behaviours to the leadership context (Fehr et al., 2020 ; Javaid et al., 2020 ).

Moral theory, institutional theory, social cognitive theory and social information processing theory have been the most widely used approaches to understand the phenomenon of unethical leadership in organisational contexts. However, we also observed that scholars have relied less on validation from other theoretical perspectives, e.g. institutional pillars, organisational structure, goal setting and stakeholder theory, among myriad others.

Finally, most of the studies have used organisations, managers, CEOs and employees as the main respondents from whom to collect data—mostly through questionnaires administered via various offline and online modes. While these categories of respondents are common in leadership research, few studies have examined leader–follower dyads.

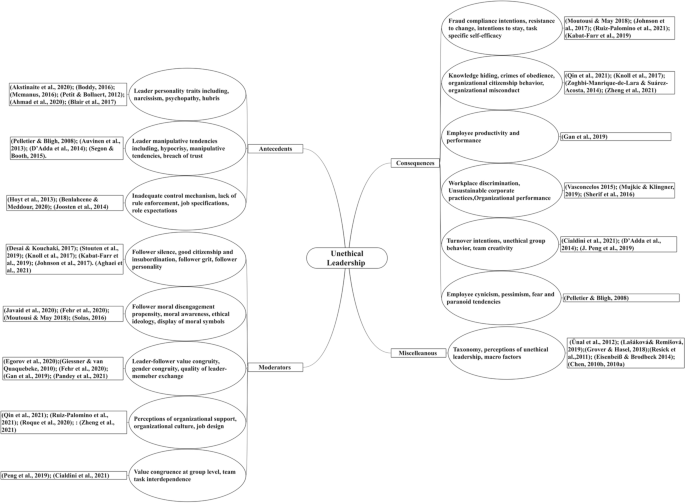

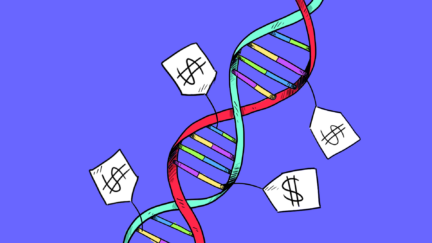

Review of Extant Research on Unethical Leadership

We thoroughly analysed the final sample of included studies with the goal of understanding the antecedents, boundary conditions and consequences of unethical leadership. We employed the content analysis method, a qualitative data analysis technique, to analyse and synthesise the selected studies and thereby develop themes, identify critical knowledge gaps in the existing literature and suggest future research directions. We adopted a three-step protocol employed in recently published studies (Kaur et al., 2021 ; Khan et al., 2021 ; Seth et al., 2020 ), which minimises bias and produces an audit trail of crucial decisions in conducting SLRs. Following Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ), we developed first-order codes and second-order codes and, finally, segregated the studies into aggregate theoretical dimensions (see Fig. 3 ). In the first step, we utilised open coding to categorise all of the reviewed studies into provisional categories. We then examined the studies to determine their research model and the results of the relationships hypothesised. When this was not possible, we relied on the major findings of the study to curate themes. In the next step—i.e. the axial coding process, we examined the relationships among these categories following deductive and inductive logic to arrive at broader categories. In the final step, we used the selective coding process to identify the final core/aggregate thematic dimensions, which we will discuss in the subsequent sections. In this step, we also invited two academicians with experience in ethics-related topics to review the aggregate themes developed in the prior step. Upon receiving their feedback, we made some minor changes to the themes.

Concept map of extant research on unethical leadership

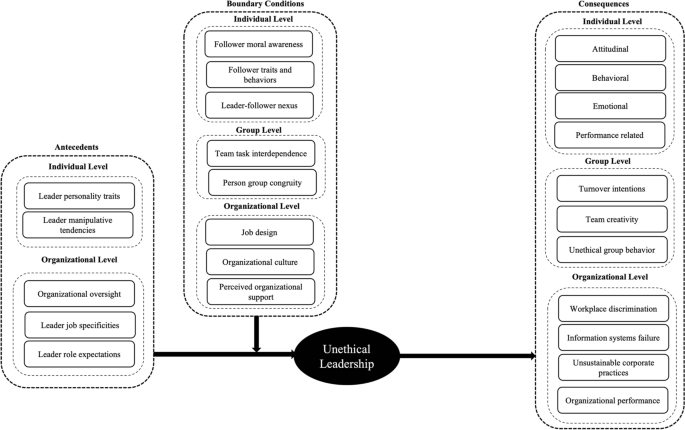

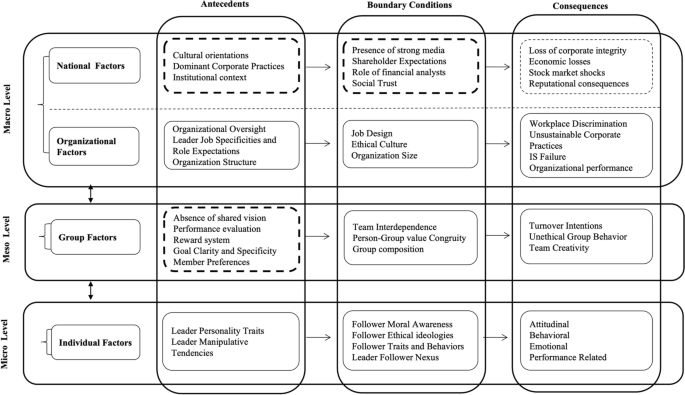

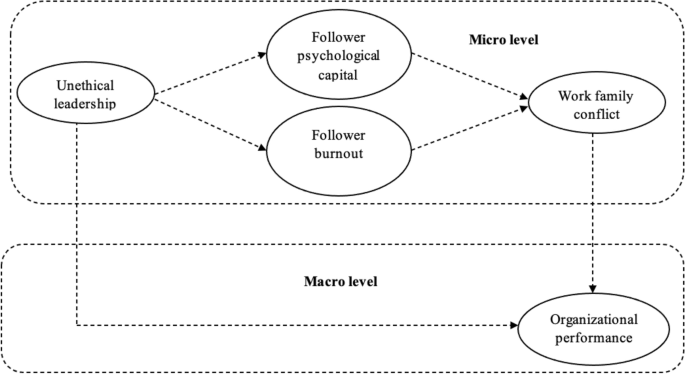

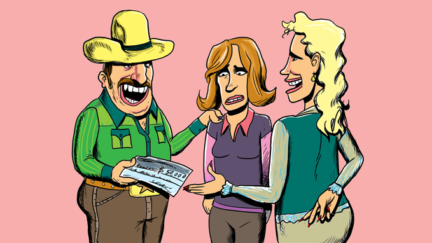

The process resulted in four broad themes: antecedents, consequences, boundary conditions and miscellaneous. The first three themes are discussed at three levels: the individual, group and organisational levels. Figure 4 presents an overview of the three key thematic areas of research examined in the prior extended literature. The major scholarly work has expanded to gauge the impact of unethical leadership, with employee-related outcomes receiving the greatest attention. We also noted that group-level examinations of unethical leadership are quite scant with outright exclusion of group-level antecedents. In the following sections, we discuss these levels and the associated factors in detail and propose important research directions in the area.

An overview of associations among three key thematic areas of research on unethical leadership

Antecedents of Unethical Leadership

We discuss factors that lead to the formation of unethical leadership and identify possible knowledge gaps in this direction.

Individual-Level Antecedents

Leaders’ personality traits.

In seeking to identify individual-level factors that promote unethical leader behaviours, the prior literature has devoted significant attention to leaders’ personality traits. In particular, the literature has cited narcissism, hubris and psychopathological traits as the determinants of unethical leader behaviour. Scholars suggest that a narcissistic leader is likely to possess inflated views about his or her own achievements and capabilities, which create dysfunctional agentic relationships among leaders and followers because leaders promote their own self-interests at the expense of their followers (Campbell et al., 2011 ). Narcissistic leaders indulge in self-aggrandising and derogatory behaviours, which often causes their subordinates to perceive them as unethical in the context of organisations (Hoffman et al., 2013 ). In addition, leaders who are high in narcissism can exhibit moral entitlement, where follower pro-organisational behaviour could lead to the emergence of unethical leadership (Ahmad et al., 2020 ).

Hubris is a similar personality trait that refers to a leader’s exaggerated confidence and prestige in work-related situations. Hubris is often described as a cognitive state in which leaders develop an amplified sense of self-esteem and pride in their abilities; their inflated self-esteem and pride, in turn, makes them think that prevailing norms do not apply to them, which could result in unethical manifestations of this personality trait (Petit & Bollaert, 2012 ). Research has provided similar evidence regarding hubris among CEOs. CEO hubris has a significant influence on the unethical practice of earnings manipulation in organisations (McManus, 2016 ). In fact, hubris is positioned to stimulate leaders towards manipulative language use, which could foster an unethical climate within organisations (Akstinaite et al., 2020 ).

Finally, unethical leadership practices are also associated with psychopaths who are deficient in emotions and conscience and, thus, engage in cold, ruthless and self-seeking behaviours (Marshall et al., 2014 ). Boddy’s ( 2016 ) study supported this, finding that leader psychopathy is associated with unethical practices, including corporate scandals.

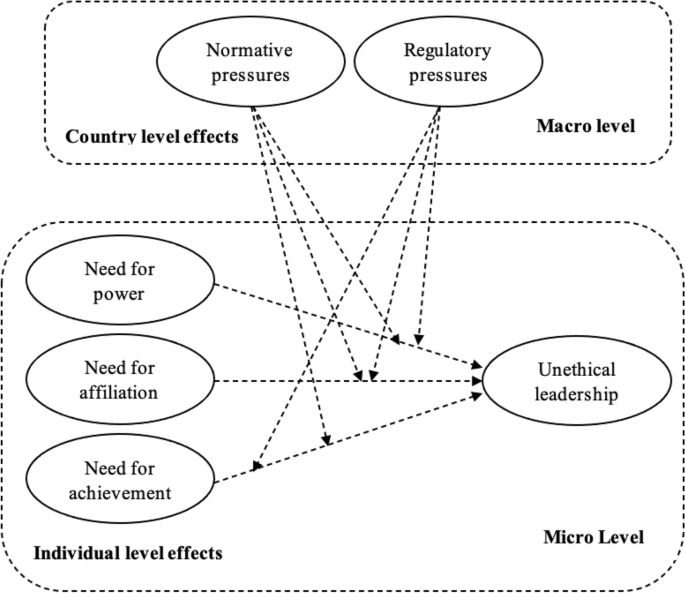

The above discussion signals that the literature, thus, far has examined only dark personality traits, which opens room for other personality frameworks in this direction. The two key research gaps in this regard are as follows. First, many individual factors, needs and behaviours remain unexamined in the literature, thus, far. Second, different personality frameworks have not been validated in the context of unethical leadership. We propose three research questions to address these research gaps. RQ1 How do leaders’ various needs (e.g. achievement, power, affiliation) produce unethical behaviours? RQ2 Do leaders’ personality traits adjust in the work context to stimulate unethical practices? RQ3 Can the cybernetic Big Five model be used to explain unethical leadership?

Leaders ‘Manipulative Tendencies

Leader immorality has long been considered the foundational pillar of unethical leadership practices within organisations (Hartman, 2000 ; Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ). Unethical leaders are often associated with a lack of integrity and exhibit manipulative behaviours, including hypocrisy and breach of trust (Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ). Here manipulation refers to the deliberate unethical use of leader competencies and use of manipulative communication directed towards followers in a disguised way (Auvinen et al., 2013 ). Scholars have identified leaders’ prominent statements and communication styles as fostering unethical behaviour within organisations (Akstinaite et al., 2020 ; D’Adda et al., 2014 ). Such manipulative storytelling directed towards followers is considered one possible way to fortify unethical leadership practices within organisations (Auvinen et al., 2013 ). In fact, such manipulation is also manifested in leaders’ use of their emotional competencies to serve their self-interests (Segon & Booth, 2015 ).

While immoral behaviour is the cornerstone of most negative leadership types, including unethical leadership, scholars have investigated most manipulative tendencies in isolation without any regard to leader–follower interactions or person–situation perspectives. To address this gap, we propose the following RQs. RQ1 How can a leader's expression of humour and/or anger interact with his or her moral awareness to produce unethical behaviours? RQ2 What is the relationship of leaders’ implicit personality traits (incremental and entity) and leader–situation fit on the formation of unethical leadership?

Organisational-Level Antecedents

Despite the centrality of organisational factors in the formation of unethical leadership, scholarly attention in this direction is quite scarce. One of the important organisational-level factors with the potential to facilitate unethical behaviour is the lack of organisational oversight mechanisms. When organisations have inadequate control mechanisms, lackadaisical rules enforcement and a lack of transparency, unethical leader behaviours tend to surface (Benlahcene & Meddour, 2020 ). The job specificities and role expectations that are entrusted to a leader can accentuate this effect. For example, under the framework of social role theory, the overarching importance of group goals and the expectations thereof can cause leaders to engage in unethical means to achieve the group’s ends (Hoyt et al., 2013 ). Joosten et al.'s ( 2014 ) study elucidates this effect, suggesting that the depletion of cognitive resources as a result of an excessive workload can cause the emergence of unethical leader behaviours.

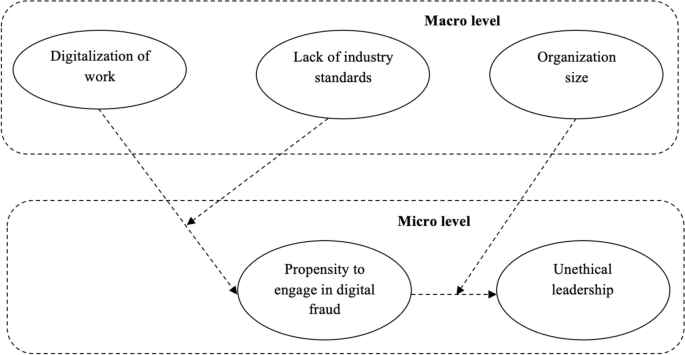

Our review of the literature suggests that scholars have yet to explore the full range of organisational factors in the unethical leadership context. To that end, future research can investigate the impact of organisation structure on unethical leader behaviour. In particular, scholars could analyse the impact of new and emerging forms of organisation structures to understand their facilitating and inhibiting impact on unethical leadership. In fact, scholars can employ various theoretical frameworks, including dual-factor theory, to identify the factors that inhibit and facilitate unethical leader behaviours; such endeavours have, thus far, been entirely overlooked. Furthermore, research can explore the potential impact of technology, particularly digital technology, on unethical leadership practices. We propose the following research questions for future scholars. RQ1 Do organic and mechanistic organisational structures differ in their influence on unethical leadership? If so, under what conditions? RQ2 What are the mechanisms that underlie unethical leader behaviours in contemporary organisational structures, e.g. virtual organisations? RQ3 Can the dual-factor theory be used to investigate different sets of facilitators and inhibitors of unethical leadership at the organisational level? RQ4 How might firm digitalisation influence unethical leadership practices at the organisational level?

Consequences of Unethical Leadership

We discuss the impact of unethical leadership at various levels and identify relevant research gaps.

Individual-Level Consequences

Employee work attitudes.

Workplace attitudes are considered the fundamental mechanisms through which employees respond to the prevailing ethical or unethical culture as well as the dominant leadership style in an organisation (Zhao & Li, 2019 ). Such employee perspectives regarding their organisation’s dominant ethical or unethical tone condition their own work-related attitudes, e.g. intentions to leave (Charoensap et al., 2018 ). In addition, these favourable or unfavourable evaluations about the dominant ethical or unethical tone in the organisation, which emanate from social exchange and social learning phenomena, condition followers to exhibit positive and negative work attitudes, respectively (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ).

In this vein, scholars have not only investigated the impact of unethical leader behaviours on the development of negative work attitudes but also the deleterious impact of such behaviours on positive work attitudes. In fact, scholars are also increasingly interested in whether unethical leadership can foster positive attitudes under certain boundary conditions. For example, Moutousi and May ( 2018 ) suggested that unethical leadership that manifests in organisational change-related initiatives can result in follower attitudinal resistance to such changes, which could benefit the organisation. This study demonstrated follower resistance as a functional organisational outcome that may result whenever unethical means or unethical ends are suspected in change manifestos heralded in the organisation. The work demonstrated that change-related unethical leadership can result in followers’ resistance to change. They found evidence of the impact of unethical leader practices, including the ethicality of change-related goals and the means to achieve them, on followers’ attitudinal resistance to such change initiatives. Furthermore, the study viewed follower resistance as a positive and functional work attitude triggered by prevailing unethical change manifestos heralded in the organisation.

In sharp contrast, unethical leadership also stimulates malfeasance and the development of negative work attitudes. Johnson et al.'s ( 2017 ) study corroborated this, finding that unethical leaders encourage financial statement fraud intentions among employees. Furthermore, unethical leadership has also been found to negatively influence important work attitudes, e.g. lower job satisfaction. Thus, unethical leadership is considered detrimental to employees’ personal growth satisfaction and intentions to stay (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, employees’ perceptions of the desirability of remaining with an organisation depend on the extent to which their leaders work to meet the employees’ developmental needs (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021 ). Because unethical leadership weakens such employee perceptions, it is logical to assume that it increases their volition to leave.

Similar evidence has been found for the influence of unethical leadership on followers’ task-specific self-efficacy (Kabat-Farr et al., 2019 ). A cognitive phenomenon, self-efficacy refers to the ‘ beliefs in one's capabilities to mobilise the motivation, cognitive resources and courses of action needed to meet given situational demands ’(Wood & Bandura, 1989 ). In the present context, task-specific self-efficacy describes an employee's subjective appraisal of his or her work-related abilities (McGonagle et al., 2015 ). By acting as workplace stressors, unethical leader behaviours negatively influence employees’ beliefs in their own ability to successfully perform their jobs (Kabat-Farr et al., 2019 ).

The prior literature suffers from inconclusive findings regarding the influence of unethical leadership on employee outcomes and the exclusion of important work attitudes. In light of the varying and inconclusive nature of the extant results, future research might consider studying other organisational factors in the context of unethical leadership. We propose two key research questions here. RQ1 How is unethical leadership related to organisational commitment? Does it influence normative, affective and continuance commitment differently? If so, how? RQ2 Does unethical leader behaviour influence work engagement and employee loyalty?

Employee Work Behaviours

Scholars have shown that unethical leadership contributes to negative workplace behaviours and, at the same time, exerts a negative influence on functional work behaviours. Drawing upon the conservation of resource theory, Qin et al. ( 2021 ) asserted that unethical leadership exerts a significant impact on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviour (Qin et al., 2021 ). In addition, unethical leader behaviours induce actual and perceived resource depletion among employees; this further reaffirms their hiding behaviour, with an aim to avoid additional resource losses. In such situations, employees not only work to protect their existing knowledge from further loss but also attempt to comply with unethical leader requests, which might violate followers’ moral grounds (Javaid et al., 2020 ). In other words, followers indulge in crimes of obedience where they find themselves abiding by leaders’ immoral actions either out of coercion or respect for their authority (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, 2013 ). This may further trigger employees to exhibit negative behaviours and reduce positive work outcomes. For example, follower perceptions of unethical leadership result in negative employee outcomes in the form of deviant workplace behaviour(DWB) and the reduction of positive work behaviours (Knoll et al., 2017 ), including organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara & Suárez-Acosta, 2014 ). In fact, the prevalence of interpersonal injustice has been shown to influence the perceptions of unethical leadership, which, in turn, promote negative interpersonal work behaviours (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara & Suárez-Acosta, 2014 ).

Despite the above findings, it is quite surprising that few employee work behaviours have been empirically validated in the context of unethical leadership. While one study above captured DWBs, we did not locate any research that has attempted to examine counterproductive work behaviours (CPBs) directed towards the organisation. Furthermore, the impact of unethical leadership on overt employee behaviours, including scouting for a new position and leaving the organisation, remains inconclusive. Future research can investigate employees’ actual exit behaviour emanating from leaders’ unethical conduct. In fact, employee voice behaviours and pro-organisational behaviours could provide significant insights into the phenomenon of unethical leadership. Finally, given the intrusion of digital technology in the workplace, the influence of unethical leadership on cyber loafing would be worth scholarly investigation. We enumerate the following key research questions for future research. RQ1 Under what conditions does unethical leadership result in destructive and constructive employee behaviours? RQ2 What is the incidence of unethical leadership on employees’ actual exit behaviour? RQ3 How and when does unethical leader behaviour result in cyber loafing?

Employee Emotions

While employee emotions are increasingly seen as important work-related feelings directed at supervisors and organisations ( b ; Peng, Schaubroeck, et al., 2019 ), the extant literature on unethical leadership has not comprehensively captured employee emotions in the work context. We found very little evidence of the emotional outrage that prevailing unethical practices in the organisation might provoke among employees. However, this stimulation of negative emotions directed at organisations and their leaders as a response to unethical leader behaviours can take the form of employee cynicism, pessimism, fear and paranoid tendencies (Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ). Pelletier and Blight ( 2008 ) found that employees experience a heightened sense of disillusionment, abhorrence and anger after being exposed to unethical leader behaviours. In fact, in their study, 50% of these emotional reactions took the form of frustration, which employees expressed in the form of cynical statements aimed at organisational practices, retributive justice and unsuccessful implementation of ethics intervention. These reactions to the breach of trust resulting from unethical leadership (Knoll et al., 2017 ) can also promote fear and increased suspicion among employees (Pelletier & Bligh, 2008 ).

While we found some evidence of the negative emotional backlash arising from unethical leadership, scholars have yet to produce conclusive evidence regarding the impact of unethical leader behaviours on negative as well as positive employee emotions. Future research can investigate whether unethical leadership results in emotional dissonance such that employees experience incompatibility between what they feel and what they express. This has potential relevance to the domain of unethical leadership research because employees, as a result of their respect for authority and fear at the workplace, might experience such emotional inconsistency. Another research direction pertains to the impact of unethical leadership on emotional labour (both service and non-service organisations), where affective events theory and social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfefer, 1978 ) offer useful theoretical lenses. Furthermore, mediation analysis has the potential to determine whether employee exhaustion and psychological burnout resulting from unethical leadership influence the work–life balance and employee well-being. Finally, employee happiness is another research area where unethical leadership plays a potential role. We recommend that scholars examine the following RQs. RQ1 Can unethical leadership result in employee emotional dissonance? RQ2 Is unethical leadership related to work–family balance or employee well-being? If so, what are the psychological mechanisms to it?

Employee Performance

In the present context, efforts to understand the role of unethical leadership in the task performance of employees, including the quality and efficiency of their work output, have been quite scarce. We identified only one a single significant study from the selected pool that examined the impact of unethical leadership on employee performance. It found that unethical leader behaviour decreases employee performance by influencing employees' moral mental maps (Gan et al., 2019 ). When employees witness amoral practices in their organisation, their moral identity activates; this, in turn, reduces their work discipline and productivity.

Scholars have largely neglected the performance outcomes that result from unethical leadership. Furthermore, prior studies lack robust theoretical frameworks that could be used to explain how unethical leadership influences employees’ task-specific performance. Noting the dearth of studies related to job performance, we suggest the use of self-determination theory to understand work motivations in the context of unethical leadership. Self-determination theory (Rigby & Ryan, 2018 ) can provide a useful theoretical lens to understand potential interactions between various levels of employee work motivations (from low quality to high quality) and unethical leadership behaviours, which, in turn, influence employee job performance. Furthermore, scholars can use the job-demands-resources (JD-R) (Lesener et al., 2019 ) model to investigate the ways in which unethical leadership increases the psychological and physiological costs associated with a job by increasing job demands (e.g. extra work shifts demanded by the leader) and reducing job resources (e.g. lack of supervisor support) to influence employee performance. We suggest three key research questions for future research. RQ1 How do various levels of employee work motivations interact with unethical leadership behaviours to influence job performance? RQ2 Does task-specific performance of employees could be influenced by unethical leadership? Can self-determination theory offer a useful theoretical lens? RQ3 In what ways does unethical leadership increase the psychological and physiological costs associated with employee performance? Can the JD-R model be used to investigate this phenomenon?

Group-Level Consequences

Scholars have investigated the potential consequences of unethical leadership at the group or team level. Cialdini et al.( 2021 ) studied the impact of unethical leadership on group members’ turnover intentions. Drawing on the attraction–selection–attrition model, the study established that unethical leader behaviours increase group members’ intentions to leave their organisations. Furthermore, followers who intend to stay with an organisation after unethical encounters engage more in cheating and other unethical group behaviours (Cialdini et al., 2021 ). D’Adda et al. ( 2014 ) found similar evidence, demonstrating that unethical leader behaviours are causally related to group members’ unethical conduct. These studies suggest that unethical leadership can stimulate an unethical climate among workgroups, which could, in turn, negatively impact other group behaviours. For example, unethical leader behaviours hinder team creativity by fostering knowledge hiding behaviours among group members ( b ; Peng, Schaubroeck, et al., 2019 ). Under the framework of social information processing and social learning theory, the study reported that team members experience psychological distress and exhibit a dysfunctional sense of competitiveness that is detrimental to team creativity.

Given the paucity of research on group-level outcomes in the context of unethical leadership, scholars must devote additional research to understanding the implications of unethical leadership at the team level. One such fundamental research direction, which has, thus, far received no attention, is the impact of unethical leadership on group performance. Future research can study in-role (task-specific) and extra-role (helping behaviour) group performances and the mechanisms through which unethical leadership influences them. Another potential area of interest might explore whether unethical leadership can trigger group conflict through in-group and out-group categorisations. In this context, social categorisation theory may prove useful. Finally, scholars can investigate group organisational citizenship behaviours to understand the circumstances in which unethical leadership promotes or hinders such pro-organisational team behaviours. Consistent with this discussion, we outline the following potential research questions. RQ1 How is unethical leadership related to group performance? RQ2 Through what specific mechanisms does unethical leadership influence in-role and extra-role group behaviours? RQ3 Can unethical leadership hinder or foster group pro-organisational behaviours? Why or why not? RQ4 Does unethical leadership result in group conflict? How can social categorisation theory lend support to this phenomenon?

Organisational-Level Consequences

We found very few scholarly investigations of the organisational-level outcomes associated with unethical leadership. Furthermore, the research pertaining to this level of consequences is extremely disparate, with the studies pertaining to various organisational dynamics. For example, Vasconcelos ( 2015 ) found that unethical leadership contributes to derogatory discrimination framing of the organisation, which may result in a negative corporate image. Furthermore, unethical leadership can foster unsustainable corporate practices, including corporate scandals that can tarnish organisations’ social responsibility ethics (Mujkic & Klingner, 2019 ). In an entirely different context, unethical leadership has been found to result in the failure of information systems that aim to foster control mechanisms within organisations (Sherif et al., 2016 ). The study establishes the strategic importance of leadership ethics where the ethical or unethical tone set by the leaders determines the success of such control mechanisms. The study further highlighted the ways in which unethical leadership can circumvent the potential use of information systems by fostering unethical conduct that supersedes control interventions.

The prior literature, however, does not provide clear empirical evidence on the organisational consequences of unethical leadership. Furthermore, evidence pertaining to contemporary forms of performance measures are lacking. In light of the paucity of existing research, future research can investigate the impact of unethical leadership on firm performance, market share and firm value. Apart from these outcomes, scholars can study firm innovation performance and sustainable business model innovation in the context of unethical leadership. We, thus, propose the following key RQs. RQ1 How does unethical leadership translate into various organisational outcomes, e.g. financial performance, market share? RQ2 In what ways does unethical leadership influence green innovation practices within organisations? RQ3 What are the mechanisms through which unethical leadership relate to sustainable business performance?

Boundary Conditions of Unethical Leadership

In this section, we discuss important boundary conditions that have been established either to mitigate or to exacerbate the negative consequences of unethical leadership as well as the various coping mechanisms and amplifiers that are critical in scholarship on unethical leadership.

Individual-Level Boundary Conditions

Follower moral awareness and ethical ideology.

The contemporary line of discourse in leadership research is witnessing a burgeoning interest in the active role that followers play in the dyadic and reciprocal nature of leadership phenomena (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014 ). Follower perspectives have been advanced to provide a more comprehensive picture of the emergence of various leadership practices (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, 2012 ) and insights into the co-production of unethical organisational behaviours (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, 2013 ). In fact, in the context of the present study, follower morals and ethicality have been established to condition the impact of unethical leadership via its various consequences. Javaid et al.'s ( 2020 ) work supports this assertion, finding differences in followers’ moral awareness and the tendency of unethical leadership to foster unethical employee behaviours. Based on socio-cognitive theory, the study advances the role of follower moral cognition and awareness in mitigating the effects of unethical leadership on unethical work behaviours. Similarly, followers with a high propensity to morally disengage retain higher levels of trust in their unethical leaders and exhibit greater support for unethical leader behaviours than do followers with a low propensity for moral disengagement (Fehr et al., 2020 ). Scholars have attributed such differences in follower compliance with unethical leader requests to follower ethical ideologies such that followers’ scores on relativism and idealism determine their perceptions and reactions to any unethical encounters (Moutousi & May, 2018 ). Followers high on idealism and low on relativism are, thus, likely to be more sensitive to the unethical practices in which their leaders engage. The common thread in these studies pertains to the followers’ moral awakening and the strengthening of their good conscience, which may reduce occurrences of unethical behaviours within the organisation (Solas, 2016 ).

While follower-focused studies are valuable, we believe leader-specific behaviours, social and ethnic ascriptions require further examination. To date, scholars have not explored leader-related factors that could condition the impact of unethical leadership. We suggest the following potential research questions. RQ1 What is the relevance of leader religious affiliations and religiosity to unethical leadership practices? Can cross-cultural studies benefit from this line of investigation? RQ2 How and under what circumstances does a leader’s gender condition the effects of unethical leadership?

Follower Traits and Behaviours

Despite the importance of follower traits in the leadership domain, we encountered only two studies in which follower tendencies and socially constructed follower identity were able to resist or amplify unethical leadership within organisations. Stouten et al. ( 2019 ) showed that employee silence plays a strategic and functional role in circumventing the negative effects of unethical leadership. Employee silence has been considered a significant dysfunctional employee behaviour that could fortify unethical leader behaviours (Morrison, 2014 ). Based on the 'see-judge-act' mechanism, however, employees can better understand the ethicality of a situation and develop more robust responses beyond merely voicing their opinions (Stouten et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, unethical leader requests are filtered through the socially constructed ideation of followership. In particular, follower good citizenship and insubordination determine whether unethical leadership is welcomed or abhorred. In other words, followers who exhibit good citizenship are more inclined to abide by their leaders’ unethical requests than followers who tend towards insubordination (Knoll et al., 2017 ). Moreover, employee grit—defined as ‘ perseverance and passion for long-term goals’ (Duckworth et al., 2007 )—moderates the relationship between unethical leader behaviour and employee outcomes. Seeking to gauge this effect, Kabat-Farr et al. ( 2019 ) documented the insignificant impact of unethical leadership on the perceived workability of high grit employees. The study also indicated that this relationship holds even when employee job involvement is high. Finally, followers who are inclined towards self-sacrificing and self-enhancement but who hold less proactive attitudes exhibit greater compliance with CEO requests (Johnson et al., 2017 ).

Based on the above discussion, the extant literature has rigorously studied personality factors, while leaving room, however, for future investigations of various job and career-related issues. Thus, we recommend that scholars address the following research question. RQ1 Does employees’ career adaptability influence the practice of unethical leadership within organisations?

Leader–Follower Nexus

Another individual-level boundary mechanism that can influence the outcomes of unethical leadership falls under the leader–follower connection. We understand this connection in terms of the moral congruence between leaders and followers and the quality of the relationship they share. Moral or value congruence refers to a follower's perception of the fit between the values he or she holds and the values the leader holds (Cable & De Rue, 2002 ). This concordance of moral and ethical principles has been considered fundamental in followers’ perceptions of leadership, both ethical and unethical (Egorov et al., 2020 ). In fact, when followers and leaders have entirely different moral identities, followers are more likely to develop unethical leadership perceptions (Giessner & van Quaquebeke, 2010 ). Studies have empirically validated the ability of this leader–follower value congruence to condition the impact of unethical leadership on follower outcomes, with high-value congruence amplifying the effect (Fehr et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, the quality of relationships between leaders and followers in the form of leader–member exchange (LMX) can also exacerbate the negative consequences of unethical leadership. For example, Gan et al. ( 2019 ) highlighted that situations of high LMX lead employees to exhibit poor job performance as a result of their greater sensitivity to unethical leader behaviours. This suggests that followers who have high reciprocity with their leaders may reduce their job performance.

While scholars have validated value congruence in the context of unethical leadership, we believe other leader–follower parameters require further investigation. Apart from moral congruence, we understand little about the role of the leader–follower nexus in unethical leadership. We suggest future studies examine the following RQ. RQ1 Do cross-generational differences surface in leader–follower dyads? If so, what is their impact on unethical leadership?

Group-Level Boundary Conditions

At the team level, scholars have paid scant attention to delineating the boundary mechanisms that might moderate team-related outcomes. Cialdini et al.'s ( 2021 )study positioned value congruence at the group level as an important boundary condition that stimulates selective attrition among group members who experience unethical leader behaviour. These group members’ perceptions of the fit between group moral values and their own ethicality (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005 ) determine their future course of action, including their decisions to leave the group or engage in malfeasance. Another group-level moderator used in the context of unethical leadership pertains to job design in groups. Goncalo and Staw ( 2006 ) found that team–task interdependence facilitates information sharing and increases the interdependence of group members in the successful completion of group tasks. Such job characteristics can mitigate the negative consequences of unethical leadership on group-level outcomes, e.g. team creativity ( b ; Peng, Schaubroeck, et al., 2019 ).

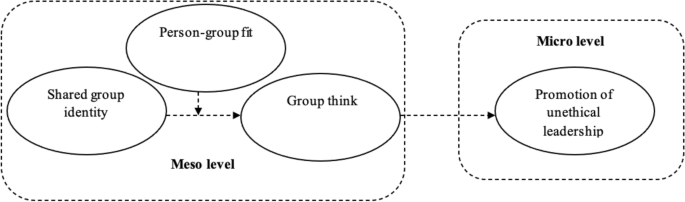

The existing research on group-level moderators is shallow, exhibits disparate results and has neglected important team- and group-level constructs. Given the paucity of research on group-level boundary conditions, we enumerate some critical research avenues with the potential to advance the literary developments in this area. RQ1 What is the role of group diversity in mitigating the negative impact of unethical leadership? RQ2 In what ways can groupthink promote unethical leadership practices within organisations?

Organisational-Level Boundary Conditions

At the organisational level, scholars have suggested work design as a coping mechanism against the potential downsides of unethical leadership. For example, job complexity, defined as the degree of complexity a job involves (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006 ), increases employee interdependence and knowledge sharing, which, in turn, help mitigate the negative effects of unethical leadership (Qin et al., 2021 ). Ruiz-Palomino et al. ( 2021 ) reported similar evidence, demonstrating that a responsibility climate can act as a buffer for the effects of unethical leader behaviour. Their study utilised job autonomy to manifest the responsibility climate of organisations where employees are entrusted with the responsibilities of their jobs and delegated adequate job authority (Ahmad et al., 2018 ). Another organisational-level coping mechanism is a resilient ethical culture that can transcend and resist unethical leader behaviours. Ethical culture delineates the line between ethical and unethical behaviours and can enable employees to develop perceptions to guide their ethical assessments of leaders’ behaviours (Kaptein, 2011 ). In the context of unethical leadership, an ethical culture could encounter unethical leader practices through a robust succession process, the eradication of perceptions of inequity, efforts to overcome moral blindness and the banality of evil and to reduce moral mutism through control mechanisms (Roque et al., 2020 ).

The above discussion reveals that scholars have examined the roles of few organisational factors in circumventing the impact of unethical leadership. In fact, most of the papers dwelt on organisational design perspectives while neglecting structure- and size-related factors. We suggest scholars explore the following RQs in future studies. RQ1 How does ownership structure relate to unethical leadership practices? RQ2 Can organisation size moderate the impact of unethical leadership? RQ3 Do unethical leadership practices differ significantly between leaders of large and small firms?

Miscellaneous

In this section, we discuss studies that did not fit in any of the prior categories. These pertain to the taxonomy of unethical leadership, the development of followers’ perceptions of unethical leadership in general and in different cultures and the country-specific conditions that influence the practice of unethical leadership at the macro-level.

Ünal et al.’s ( 2012 ) extension of the conceptual underpinnings of unethical leadership added the dimensions of utilitarianism, perceptions of justice and the right to dignity as important normative grounds to define unethical leadership in a robust way. These dimensions enhanced the conceptual rigour of unethical leadership, which the existing literary work in the field has largely ignored.

In another approach to unethical leadership in work contexts, scholars have gauged the influence of various individual-, organisational- and country-specific factors on perceptions of unethical leadership. For example, managers’ demographic characteristics, including age, gender, tenure and education, have been shown to influence their perceptions of unethical leadership (Lašáková& Remišová, 2019). In a slightly different context, follower perceptions of unethical leadership stem from the reputation that a leader has prior to the manifestation of infidelity at work and the degree to which the leader’s discretion involved the abuse of power (Grover & Hasel, 2018 ). As expected, these perceptions vary across countries. However, similar attributions of unethical leadership have also surfaced in the prior literature. While noting differences in the perceptions of unethical leadership across cultures, Resick et al. ( 2011 )also identified dominant perceptions that held across six countries. Similarly, Eisenbeiß and Brodbeck ( 2014 ) found that managers’ perceptions of unethical leadership in Eastern and Western countries are specific to their cultural roots, but some attributions, including those regarding a leader’s honesty, integrity, responsibility etc., remain constant across countries (Kimura & Nishikawa, 2018 ). Apart from institutional pressures from a country’s media, shareholders also influence the practice of unethical leadership (Chen, 2010a , 2010b ).

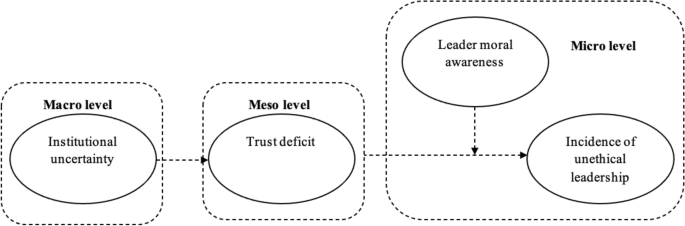

While the above studies have captured institutional factors, we did not locate any robust study delineating the impact of various institutional conditions on the formation of unethical leadership. It is important to note that broader institutional pillars can influence the perceptions of moral behaviour as well as the legality of actions in a country. Thus, we propose that future scholars address the following RQs. RQ1 How do a country’s institutional conditions (regulatory, normative and socio-cultural) influence unethical leadership? RQ2 Does the institutional stability of a country influence the extent of unethical leadership in organisations within that country?

Conceptual Framework and Potential Models

In this section, we discuss our multi-level conceptual framework and potential research models, which scholars can further investigate to advance the literary space of unethical leadership. Our multi-level conceptual framework essentially extends the existing body of work on unethical leadership while including the missing elements identified in the knowledge gaps (see Sect. 4). The extant literature has neglected group-level mechanisms—in particular, group-level antecedents—as well as organisational-level consequences and antecedents (see Fig. 4 ). Our conceptual model addresses these lacunae by capturing the missing elements and organising the extant work in a multi-level framework. While the multi-level framework addresses the broader themes in the field, the proposed potential research models discern precise research directions informed by the multi-level framework. Scholars have suggested that proposing potential models enables us to address critical knowledge gaps in the existing literature and thereby inform theoretical as well practical developments in the field (Shamsollahi et al., 2021 ).

Micro-Meso-Macro (M3) Framework of Unethical Leadership

Our segregation of the sampled studies into various themes offers a broader understanding of the similarities and differences in the extant academic discourse on unethical leadership and allowed us to uncover various knowledge gaps in the current body of work. Following this understanding and using inductive logic, we developed a M3 framework of unethical leadership using a multi-level analysis approach. Multiple levels of analysis are quite popular among organisational research scholars primarily because their use facilitates a robust analytical focus by offering linkages among the various units of organisations (Roberts, 2020 ).