Speech to Text - Voice Typing & Transcription

Take notes with your voice for free, or automatically transcribe audio & video recordings. secure, accurate & blazing fast..

~ Proudly serving millions of users since 2015 ~

I need to >

Dictate Notes

Start taking notes, on our online voice-enabled notepad right away, for free.

Transcribe Recordings

Automatically transcribe (and optionally translate) audios & videos - upload files from your device or link to an online resource (Drive, YouTube, TikTok or other). Export to text, docx, video subtitles and more.

Speechnotes is a reliable and secure web-based speech-to-text tool that enables you to quickly and accurately transcribe your audio and video recordings, as well as dictate your notes instead of typing, saving you time and effort. With features like voice commands for punctuation and formatting, automatic capitalization, and easy import/export options, Speechnotes provides an efficient and user-friendly dictation and transcription experience. Proudly serving millions of users since 2015, Speechnotes is the go-to tool for anyone who needs fast, accurate & private transcription. Our Portfolio of Complementary Speech-To-Text Tools Includes:

Voice typing - Chrome extension

Dictate instead of typing on any form & text-box across the web. Including on Gmail, and more.

Transcription API & webhooks

Speechnotes' API enables you to send us files via standard POST requests, and get the transcription results sent directly to your server.

Zapier integration

Combine the power of automatic transcriptions with Zapier's automatic processes. Serverless & codeless automation! Connect with your CRM, phone calls, Docs, email & more.

Android Speechnotes app

Speechnotes' notepad for Android, for notes taking on your mobile, battle tested with more than 5Million downloads. Rated 4.3+ ⭐

iOS TextHear app

TextHear for iOS, works great on iPhones, iPads & Macs. Designed specifically to help people with hearing impairment participate in conversations. Please note, this is a sister app - so it has its own pricing plan.

Audio & video converting tools

Tools developed for fast - batch conversions of audio files from one type to another and extracting audio only from videos for minimizing uploads.

Our Sister Apps for Text-To-Speech & Live Captioning

Complementary to Speechnotes

Reads out loud texts, files & web pages

Reads out loud texts, PDFs, e-books & websites for free

Speechlogger

Live Captioning & Translation

Live captions & translations for online meetings, webinars, and conferences.

Need Human Transcription? We Can Offer a 10% Discount Coupon

We do not provide human transcription services ourselves, but, we partnered with a UK company that does. Learn more on human transcription and the 10% discount .

Dictation Notepad

Start taking notes with your voice for free

Speech to Text online notepad. Professional, accurate & free speech recognizing text editor. Distraction-free, fast, easy to use web app for dictation & typing.

Speechnotes is a powerful speech-enabled online notepad, designed to empower your ideas by implementing a clean & efficient design, so you can focus on your thoughts. We strive to provide the best online dictation tool by engaging cutting-edge speech-recognition technology for the most accurate results technology can achieve today, together with incorporating built-in tools (automatic or manual) to increase users' efficiency, productivity and comfort. Works entirely online in your Chrome browser. No download, no install and even no registration needed, so you can start working right away.

Speechnotes is especially designed to provide you a distraction-free environment. Every note, starts with a new clear white paper, so to stimulate your mind with a clean fresh start. All other elements but the text itself are out of sight by fading out, so you can concentrate on the most important part - your own creativity. In addition to that, speaking instead of typing, enables you to think and speak it out fluently, uninterrupted, which again encourages creative, clear thinking. Fonts and colors all over the app were designed to be sharp and have excellent legibility characteristics.

Example use cases

- Voice typing

- Writing notes, thoughts

- Medical forms - dictate

- Transcribers (listen and dictate)

Transcription Service

Start transcribing

Fast turnaround - results within minutes. Includes timestamps, auto punctuation and subtitles at unbeatable price. Protects your privacy: no human in the loop, and (unlike many other vendors) we do NOT keep your audio. Pay per use, no recurring payments. Upload your files or transcribe directly from Google Drive, YouTube or any other online source. Simple. No download or install. Just send us the file and get the results in minutes.

- Transcribe interviews

- Captions for Youtubes & movies

- Auto-transcribe phone calls or voice messages

- Students - transcribe lectures

- Podcasters - enlarge your audience by turning your podcasts into textual content

- Text-index entire audio archives

Key Advantages

Speechnotes is powered by the leading most accurate speech recognition AI engines by Google & Microsoft. We always check - and make sure we still use the best. Accuracy in English is very good and can easily reach 95% accuracy for good quality dictation or recording.

Lightweight & fast

Both Speechnotes dictation & transcription are lightweight-online no install, work out of the box anywhere you are. Dictation works in real time. Transcription will get you results in a matter of minutes.

Super Private & Secure!

Super private - no human handles, sees or listens to your recordings! In addition, we take great measures to protect your privacy. For example, for transcribing your recordings - we pay Google's speech to text engines extra - just so they do not keep your audio for their own research purposes.

Health advantages

Typing may result in different types of Computer Related Repetitive Strain Injuries (RSI). Voice typing is one of the main recommended ways to minimize these risks, as it enables you to sit back comfortably, freeing your arms, hands, shoulders and back altogether.

Saves you time

Need to transcribe a recording? If it's an hour long, transcribing it yourself will take you about 6! hours of work. If you send it to a transcriber - you will get it back in days! Upload it to Speechnotes - it will take you less than a minute, and you will get the results in about 20 minutes to your email.

Saves you money

Speechnotes dictation notepad is completely free - with ads - or a small fee to get it ad-free. Speechnotes transcription is only $0.1/minute, which is X10 times cheaper than a human transcriber! We offer the best deal on the market - whether it's the free dictation notepad ot the pay-as-you-go transcription service.

Dictation - Free

- Online dictation notepad

- Voice typing Chrome extension

Dictation - Premium

- Premium online dictation notepad

- Premium voice typing Chrome extension

- Support from the development team

Transcription

$0.1 /minute.

- Pay as you go - no subscription

- Audio & video recordings

- Speaker diarization in English

- Generate captions .srt files

- REST API, webhooks & Zapier integration

Compare plans

Privacy policy.

We at Speechnotes, Speechlogger, TextHear, Speechkeys value your privacy, and that's why we do not store anything you say or type or in fact any other data about you - unless it is solely needed for the purpose of your operation. We don't share it with 3rd parties, other than Google / Microsoft for the speech-to-text engine.

Privacy - how are the recordings and results handled?

- transcription service.

Our transcription service is probably the most private and secure transcription service available.

- HIPAA compliant.

- No human in the loop. No passing your recording between PCs, emails, employees, etc.

- Secure encrypted communications (https) with and between our servers.

- Recordings are automatically deleted from our servers as soon as the transcription is done.

- Our contract with Google / Microsoft (our speech engines providers) prohibits them from keeping any audio or results.

- Transcription results are securely kept on our secure database. Only you have access to them - only if you sign in (or provide your secret credentials through the API)

- You may choose to delete the transcription results - once you do - no copy remains on our servers.

- Dictation notepad & extension

For dictation, the recording & recognition - is delegated to and done by the browser (Chrome / Edge) or operating system (Android). So, we never even have access to the recorded audio, and Edge's / Chrome's / Android's (depending the one you use) privacy policy apply here.

The results of the dictation are saved locally on your machine - via the browser's / app's local storage. It never gets to our servers. So, as long as your device is private - your notes are private.

Payments method privacy

The whole payments process is delegated to PayPal / Stripe / Google Pay / Play Store / App Store and secured by these providers. We never receive any of your credit card information.

More generic notes regarding our site, cookies, analytics, ads, etc.

- We may use Google Analytics on our site - which is a generic tool to track usage statistics.

- We use cookies - which means we save data on your browser to send to our servers when needed. This is used for instance to sign you in, and then keep you signed in.

- For the dictation tool - we use your browser's local storage to store your notes, so you can access them later.

- Non premium dictation tool serves ads by Google. Users may opt out of personalized advertising by visiting Ads Settings . Alternatively, users can opt out of a third-party vendor's use of cookies for personalized advertising by visiting https://youradchoices.com/

- In case you would like to upload files to Google Drive directly from Speechnotes - we'll ask for your permission to do so. We will use that permission for that purpose only - syncing your speech-notes to your Google Drive, per your request.

Skip to main navigation

- Email Updates

- Federal Court Finder

What Does Free Speech Mean?

Among other cherished values, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech. The U.S. Supreme Court often has struggled to determine what exactly constitutes protected speech. The following are examples of speech, both direct (words) and symbolic (actions), that the Court has decided are either entitled to First Amendment protections, or not.

The First Amendment states, in relevant part, that:

“Congress shall make no law...abridging freedom of speech.”

Freedom of speech includes the right:

- Not to speak (specifically, the right not to salute the flag). West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette , 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

- Of students to wear black armbands to school to protest a war (“Students do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.”). Tinker v. Des Moines , 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

- To use certain offensive words and phrases to convey political messages. Cohen v. California , 403 U.S. 15 (1971).

- To contribute money (under certain circumstances) to political campaigns. Buckley v. Valeo , 424 U.S. 1 (1976).

- To advertise commercial products and professional services (with some restrictions). Virginia Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Consumer Council , 425 U.S. 748 (1976); Bates v. State Bar of Arizona , 433 U.S. 350 (1977).

- To engage in symbolic speech, (e.g., burning the flag in protest). Texas v. Johnson , 491 U.S. 397 (1989); United States v. Eichman , 496 U.S. 310 (1990).

Freedom of speech does not include the right:

- To incite imminent lawless action. Brandenburg v. Ohio , 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

- To make or distribute obscene materials. Roth v. United States , 354 U.S. 476 (1957).

- To burn draft cards as an anti-war protest. United States v. O’Brien , 391 U.S. 367 (1968).

- To permit students to print articles in a school newspaper over the objections of the school administration. Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier , 484 U.S. 260 (1988).

- Of students to make an obscene speech at a school-sponsored event. Bethel School District #43 v. Fraser , 478 U.S. 675 (1986).

- Of students to advocate illegal drug use at a school-sponsored event. Morse v. Frederick, __ U.S. __ (2007).

Disclaimer: These resources are created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for use in educational activities only. They may not reflect the current state of the law, and are not intended to provide legal advice, guidance on litigation, or commentary on legislation.

DISCLAIMER: These resources are created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for educational purposes only. They may not reflect the current state of the law, and are not intended to provide legal advice, guidance on litigation, or commentary on any pending case or legislation.

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

Fundamentals of Speechwriting

Taught in English

Financial aid available

Gain insight into a topic and learn the fundamentals

Instructor: Laura Ewing

Included with Coursera Plus

Recommended experience

Beginner level

Some experience—even if minimal—in writing and delivering speeches.

Skills you'll gain

- Speechwriting

- Public Speaking

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There is 1 module in this course

Fundamentals of Speechwriting is a course that enhances speechwriting skills by deepening learners’ understanding of the impact of key elements on developing coherent and impactful speeches. It is aimed at learners with experience writing and speaking who wish to enhance their current skills. This course covers strategies for analyzing audience and purpose, selecting style and tone, and incorporating rhetorical appeals and storytelling. Learners will craft openings and closings, build structured outlines, review effective rehearsal techniques, and examine methods for editing and revising. This comprehensive course prepares participants to deliver powerful and persuasive speeches.

By the end of this course, learners will be able to: -Identify the elements of speechwriting -Identify common advanced writing techniques for speeches -Identify the parts of a structured speech outline -Identify the role of speech rehearsal, editing, and revising in speechwriting

This is a single-module short course. This module covers the three stages of speechwriting: prewriting, drafting, and editing and revising.

What's included

10 videos 1 reading 4 quizzes

10 videos • Total 61 minutes

- Welcome to Fundamentals of Speechwriting • 3 minutes • Preview module

- Asking "Who?" and "Why?" • 8 minutes

- The Best Way to Say It • 5 minutes

- Appealing to Your Audience • 8 minutes

- Where to Start? • 6 minutes

- Connecting Your Ideas • 5 minutes

- Wrapping Up • 6 minutes

- The Power of Practice • 5 minutes

- Editing vs. Revising • 8 minutes

- Pulling it All Together • 3 minutes

1 reading • Total 5 minutes

- Welcome • 5 minutes

4 quizzes • Total 60 minutes

- Final Assessment • 30 minutes

- New Quiz • 10 minutes

- Writing a Speech • 10 minutes

- Refining a Speech • 10 minutes

The Coursera Instructor Network is a select group of instructors who have demonstrated expertise in specific tools or skills through their industry experience or academic backgrounds in the topics of their courses.

Recommended if you're interested in Personal Development

Coursera Project Network

Create an Affinity Diagram Using Creately

Guided Project

University of California, Santa Cruz

Ecosystems of California

University of California San Diego

Communicating with the Public

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Sports Turf Management: Best Practices

Why people choose coursera for their career.

New to Personal Development? Start here.

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I purchase the Certificate?

When you purchase a Certificate you get access to all course materials, including graded assignments. Upon completing the course, your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

You will be eligible for a full refund until two weeks after your payment date, or (for courses that have just launched) until two weeks after the first session of the course begins, whichever is later. You cannot receive a refund once you’ve earned a Course Certificate, even if you complete the course within the two-week refund period. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- About me/contact

How to write a good speech in 7 steps

By: Susan Dugdale

- an easily followed format for writing a great speech

Did you know writing a speech doesn't have be an anxious, nail biting experience?

Unsure? Don't be.

You may have lived with the idea you were never good with words for a long time. Or perhaps giving speeches at school brought you out in cold sweats.

However learning how to write a speech is relatively straight forward when you learn to write out loud.

And that's the journey I am offering to take you on: step by step.

To learn quickly, go slow

Take all the time you need. This speech format has 7 steps, each building on the next.

Walk, rather than run, your way through all of them. Don't be tempted to rush. Familiarize yourself with the ideas. Try them out.

I know there are well-advertised short cuts and promises of 'write a speech in 5 minutes'. However in reality they only truly work for somebody who already has the basic foundations of speech writing in place.

The foundation of good speech writing

These steps are the backbone of sound speech preparation. Learn and follow them well at the outset and yes, given more experience and practice you could probably flick something together quickly. Like any skill, the more it's used, the easier it gets.

In the meantime...

Step 1: Begin with a speech overview or outline

Are you in a hurry? Without time to read a whole page? Grab ... The Quick How to Write a Speech Checklist And come back to get the details later.

- WHO you are writing your speech for (your target audience)

- WHY you are preparing this speech. What's the main purpose of your speech? Is it to inform or tell your audience about something? To teach them a new skill or demonstrate something? To persuade or to entertain? (See 4 types of speeches: informative, demonstrative, persuasive and special occasion or entertaining for more.) What do you want them to think, feel or do as a result of listening the speech?

- WHAT your speech is going to be about (its topic) - You'll want to have thought through your main points and have ranked them in order of importance. And have sorted the supporting research you need to make those points effectively.

- HOW much time you have for your speech eg. 3 minutes, 5 minutes... The amount of time you've been allocated dictates how much content you need. If you're unsure check this page: how many words per minute in a speech: a quick reference guide . You'll find estimates of the number of words required for 1 - 10 minute speeches by slow, medium and fast talkers.

Use an outline

The best way to make sure you deliver a perfect speech is to start by carefully completing a speech outline covering the essentials: WHO, WHY, WHAT and HOW.

Beginning to write without thinking your speech through is a bit like heading off on a journey not knowing why you're traveling or where you're going to end up. You can find yourself lost in a deep, dark, murky muddle of ideas very quickly!

Pulling together a speech overview or outline is a much safer option. It's the map you'll follow to get where you want to go.

Get a blank speech outline template to complete

Click the link to find out a whole lot more about preparing a speech outline . ☺ You'll also find a free printable blank speech outline template. I recommend using it!

Understanding speech construction

Before you begin to write, using your completed outline as a guide, let's briefly look at what you're aiming to prepare.

- an opening or introduction

- the body where the bulk of the information is given

- and an ending (or summary).

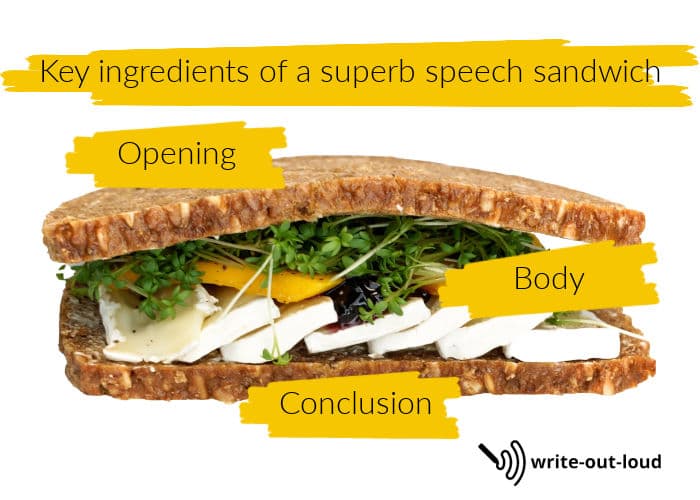

Imagine your speech as a sandwich

If you think of a speech as a sandwich you'll get the idea.

The opening and ending are the slices of bread holding the filling (the major points or the body of your speech) together.

You can build yourself a simple sandwich with one filling (one big idea) or you could go gourmet and add up to three or, even five. The choice is yours.

But whatever you choose to serve, as a good cook, you need to consider who is going to eat it! And that's your audience.

So let's find out who they are before we do anything else.

Step 2: Know who you are talking to

Understanding your audience.

Did you know a good speech is never written from the speaker's point of view? ( If you need to know more about why check out this page on building rapport .)

Begin with the most important idea/point on your outline.

Consider HOW you can explain (show, tell) that to your audience in the most effective way for them to easily understand it.

Writing from the audience's point of view

To help you write from an audience point of view, it's a good idea to identify either a real person or the type of person who is most likely to be listening to you.

Make sure you select someone who represents the "majority" of the people who will be in your audience. That is they are neither struggling to comprehend you at the bottom of your scale or light-years ahead at the top.

Now imagine they are sitting next to you eagerly waiting to hear what you're going to say. Give them a name, for example, Joe, to help make them real.

Ask yourself

- How do I need to tailor my information to meet Joe's needs? For example, do you tell personal stories to illustrate your main points? Absolutely! Yes. This is a very powerful technique. (Click storytelling in speeches to find out more.)

- What type or level of language is right for Joe as well as my topic? For example if I use jargon (activity, industry or profession specific vocabulary) will it be understood?

Step 3: Writing as you speak

Writing oral language.

Write down what you want to say about your first main point as if you were talking directly to Joe.

If it helps, say it all out loud before you write it down and/or record it.

Use the information below as a guide

(Click to download The Characteristics of Spoken Language as a pdf.)

You do not have to write absolutely everything you're going to say down * but you do need to write down, or outline, the sequence of ideas to ensure they are logical and easily followed.

Remember too, to explain or illustrate your point with examples from your research.

( * Tip: If this is your first speech the safety net of having everything written down could be just what you need. It's easier to recover from a patch of jitters when you have a word by word manuscript than if you have either none, or a bare outline. Your call!)

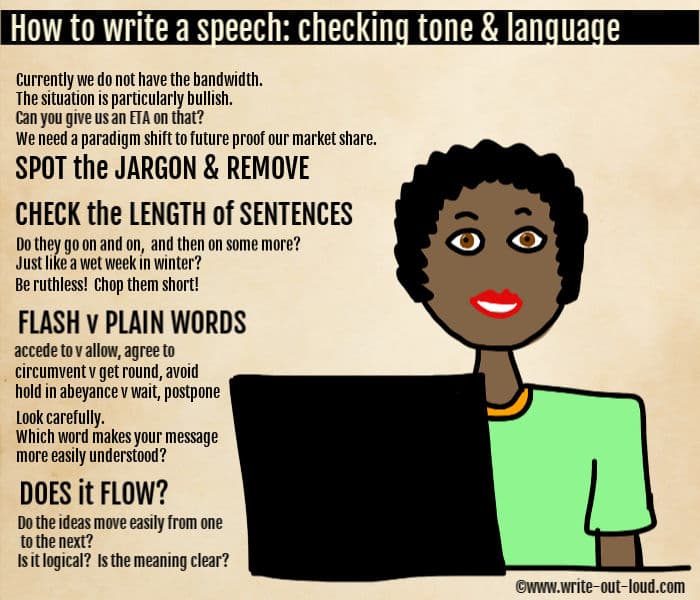

Step 4: Checking tone and language

The focus of this step is re-working what you've done in Step 2 and 3.

You identified who you were talking to (Step 2) and in Step 3, wrote up your first main point. Is it right? Have you made yourself clear? Check it.

How well you complete this step depends on how well you understand the needs of the people who are going to listen to your speech.

Please do not assume because you know what you're talking about the person (Joe) you've chosen to represent your audience will too. Joe is not a mind-reader!

How to check what you've prepared

- Check the "tone" of your language . Is it right for the occasion, subject matter and your audience?

- Check the length of your sentences. You need short sentences. If they're too long or complicated you risk losing your listeners.

Check for jargon too. These are industry, activity or group exclusive words.

For instance take the phrase: authentic learning . This comes from teaching and refers to connecting lessons to the daily life of students. Authentic learning is learning that is relevant and meaningful for students. If you're not a teacher you may not understand the phrase.

The use of any vocabulary requiring insider knowledge needs to be thought through from the audience perspective. Jargon can close people out.

- Read what you've written out loud. If it flows naturally, in a logical manner, continue the process with your next main idea. If it doesn't, rework.

We use whole sentences and part ones, and we mix them up with asides or appeals e.g. "Did you get that? Of course you did. Right...Let's move it along. I was saying ..."

Click for more about the differences between spoken and written language .

And now repeat the process

Repeat this process for the remainder of your main ideas.

Because you've done the first one carefully, the rest should follow fairly easily.

Step 5: Use transitions

Providing links or transitions between main ideas.

Between each of your main ideas you need to provide a bridge or pathway for your audience. The clearer the pathway or bridge, the easier it is for them to make the transition from one idea to the next.

If your speech contains more than three main ideas and each is building on the last, then consider using a "catch-up" or summary as part of your transitions.

Is your speech being evaluated? Find out exactly what aspects you're being assessed on using this standard speech evaluation form

Link/transition examples

A link can be as simple as:

"We've explored one scenario for the ending of Block Buster 111, but let's consider another. This time..."

What follows this transition is the introduction of Main Idea Two.

Here's a summarizing link/transition example:

"We've ended Blockbuster 111 four ways so far. In the first, everybody died. In the second, everybody died BUT their ghosts remained to haunt the area. In the third, one villain died. His partner reformed and after a fight-out with the hero, they both strode off into the sunset, friends forever. In the fourth, the hero dies in a major battle but is reborn sometime in the future.

And now what about one more? What if nobody died? The fifth possibility..."

Go back through your main ideas checking the links. Remember Joe as you go. Try each transition or link out loud and really listen to yourself. Is it obvious? Easily followed?

Keep them if they are clear and concise.

For more about transitions (with examples) see Andrew Dlugan's excellent article, Speech Transitions: Magical words and Phrases .

Step 6: The end of your speech

The ideal ending is highly memorable . You want it to live on in the minds of your listeners long after your speech is finished. Often it combines a call to action with a summary of major points.

Example speech endings

Example 1: The desired outcome of a speech persuading people to vote for you in an upcoming election is that they get out there on voting day and do so. You can help that outcome along by calling them to register their support by signing a prepared pledge statement as they leave.

"We're agreed we want change. You can help us give it to you by signing this pledge statement as you leave. Be part of the change you want to see!

Example 2: The desired outcome is increased sales figures. The call to action is made urgent with the introduction of time specific incentives.

"You have three weeks from the time you leave this hall to make that dream family holiday in New Zealand yours. Can you do it? Will you do it? The kids will love it. Your wife will love it. Do it now!"

How to figure out the right call to action

A clue for working out what the most appropriate call to action might be, is to go back to your original purpose for giving the speech.

- Was it to motivate or inspire?

- Was it to persuade to a particular point of view?

- Was it to share specialist information?

- Was it to celebrate a person, a place, time or event?

Ask yourself what you want people to do as a result of having listened to your speech.

For more about ending speeches

Visit this page for more about how to end a speech effectively . You'll find two additional types of speech endings with examples.

Write and test

Write your ending and test it out loud. Try it out on a friend, or two. Is it good? Does it work?

Step 7: The introduction

Once you've got the filling (main ideas) the linking and the ending in place, it's time to focus on the introduction.

The introduction comes last as it's the most important part of your speech. This is the bit that either has people sitting up alert or slumped and waiting for you to end. It's the tone setter!

What makes a great speech opening?

Ideally you want an opening that makes listening to you the only thing the 'Joes' in the audience want to do.

You want them to forget they're hungry or that their chair is hard or that their bills need paying.

The way to do that is to capture their interest straight away. You do this with a "hook".

Hooks to catch your audience's attention

Hooks come in as many forms as there are speeches and audiences. Your task is work out what specific hook is needed to catch your audience.

Go back to the purpose. Why are you giving this speech?

Once you have your answer, consider your call to action. What do you want the audience to do, and, or take away, as a result of listening to you?

Next think about the imaginary or real person you wrote for when you were focusing on your main ideas.

Choosing the best hook

- Is it humor?

- Would shock tactics work?

- Is it a rhetorical question?

- Is it formality or informality?

- Is it an outline or overview of what you're going to cover, including the call to action?

- Or is it a mix of all these elements?

A hook example

Here's an example from a fictional political speech. The speaker is lobbying for votes. His audience are predominately workers whose future's are not secure.

"How's your imagination this morning? Good? (Pause for response from audience) Great, I'm glad. Because we're going to put it to work starting right now.

I want you to see your future. What does it look like? Are you happy? Is everything as you want it to be? No? Let's change that. We could do it. And we could do it today.

At the end of this speech you're going to be given the opportunity to change your world, for a better one ...

No, I'm not a magician. Or a simpleton with big ideas and precious little commonsense. I'm an ordinary man, just like you. And I have a plan to share!"

And then our speaker is off into his main points supported by examples. The end, which he has already foreshadowed in his opening, is the call to vote for him.

Prepare several hooks

Experiment with several openings until you've found the one that serves your audience, your subject matter and your purpose best.

For many more examples of speech openings go to: how to write a speech introduction . You'll find 12 of the very best ways to start a speech.

That completes the initial seven steps towards writing your speech. If you've followed them all the way through, congratulations, you now have the text of your speech!

Although you might have the words, you're still a couple of steps away from being ready to deliver them. Both of them are essential if you want the very best outcome possible. They are below. Please take them.

Step 8: Checking content and timing

This step pulls everything together.

Check once, check twice, check three times & then once more!

Go through your speech really carefully.

On the first read through check you've got your main points in their correct order with supporting material, plus an effective introduction and ending.

On the second read through check the linking passages or transitions making sure they are clear and easily followed.

On the third reading check your sentence structure, language use and tone.

Double, triple check the timing

Now go though once more.

This time read it aloud slowly and time yourself.

If it's too long for the time allowance you've been given make the necessary cuts.

Start by looking at your examples rather than the main ideas themselves. If you've used several examples to illustrate one principal idea, cut the least important out.

Also look to see if you've repeated yourself unnecessarily or, gone off track. If it's not relevant, cut it.

Repeat the process, condensing until your speech fits the required length, preferably coming in just under your time limit.

You can also find out how approximately long it will take you to say the words you have by using this very handy words to minutes converter . It's an excellent tool, one I frequently use. While it can't give you a precise time, it does provide a reasonable estimate.

Step 9: Rehearsing your speech

And NOW you are finished with writing the speech, and are ready for REHEARSAL .

Please don't be tempted to skip this step. It is not an extra thrown in for good measure. It's essential.

The "not-so-secret" secret of successful speeches combines good writing with practice, practice and then, practicing some more.

Go to how to practice public speaking and you'll find rehearsal techniques and suggestions to boost your speech delivery from ordinary to extraordinary.

The Quick How to Write a Speech Checklist

Before you begin writing you need:.

- Your speech OUTLINE with your main ideas ranked in the order you're going to present them. (If you haven't done one complete this 4 step sample speech outline . It will make the writing process much easier.)

- Your RESEARCH

- You also need to know WHO you're speaking to, the PURPOSE of the speech and HOW long you're speaking for

The basic format

- the body where you present your main ideas

Split your time allowance so that you spend approximately 70% on the body and 15% each on the introduction and ending.

How to write the speech

- Write your main ideas out incorporating your examples and research

- Link them together making sure each flows in a smooth, logical progression

- Write your ending, summarizing your main ideas briefly and end with a call for action

- Write your introduction considering the 'hook' you're going to use to get your audience listening

- An often quoted saying to explain the process is: Tell them what you're going to tell them (Introduction) Tell them (Body of your speech - the main ideas plus examples) Tell them what you told them (The ending)

TEST before presenting. Read aloud several times to check the flow of material, the suitability of language and the timing.

- Return to top

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Blogging Aloud

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Freedom of Speech

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: December 4, 2017

Freedom of speech—the right to express opinions without government restraint—is a democratic ideal that dates back to ancient Greece. In the United States, the First Amendment guarantees free speech, though the United States, like all modern democracies, places limits on this freedom. In a series of landmark cases, the U.S. Supreme Court over the years has helped to define what types of speech are—and aren’t—protected under U.S. law.

The ancient Greeks pioneered free speech as a democratic principle. The ancient Greek word “parrhesia” means “free speech,” or “to speak candidly.” The term first appeared in Greek literature around the end of the fifth century B.C.

During the classical period, parrhesia became a fundamental part of the democracy of Athens. Leaders, philosophers, playwrights and everyday Athenians were free to openly discuss politics and religion and to criticize the government in some settings.

First Amendment

In the United States, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech.

The First Amendment was adopted on December 15, 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution . The Bill of Rights provides constitutional protection for certain individual liberties, including freedoms of speech, assembly and worship.

The First Amendment doesn’t specify what exactly is meant by freedom of speech. Defining what types of speech should and shouldn’t be protected by law has fallen largely to the courts.

In general, the First Amendment guarantees the right to express ideas and information. On a basic level, it means that people can express an opinion (even an unpopular or unsavory one) without fear of government censorship.

It protects all forms of communication, from speeches to art and other media.

Flag Burning

While freedom of speech pertains mostly to the spoken or written word, it also protects some forms of symbolic speech. Symbolic speech is an action that expresses an idea.

Flag burning is an example of symbolic speech that is protected under the First Amendment. Gregory Lee Johnson, a youth communist, burned a flag during the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas to protest the Reagan administration.

The U.S. Supreme Court , in 1990, reversed a Texas court’s conviction that Johnson broke the law by desecrating the flag. Texas v. Johnson invalidated statutes in Texas and 47 other states prohibiting flag burning.

When Isn’t Speech Protected?

Not all speech is protected under the First Amendment.

Forms of speech that aren’t protected include:

- Obscene material such as child pornography

- Plagiarism of copyrighted material

- Defamation (libel and slander)

- True threats

Speech inciting illegal actions or soliciting others to commit crimes aren’t protected under the First Amendment, either.

The Supreme Court decided a series of cases in 1919 that helped to define the limitations of free speech. Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, shortly after the United States entered into World War I . The law prohibited interference in military operations or recruitment.

Socialist Party activist Charles Schenck was arrested under the Espionage Act after he distributed fliers urging young men to dodge the draft. The Supreme Court upheld his conviction by creating the “clear and present danger” standard, explaining when the government is allowed to limit free speech. In this case, they viewed draft resistant as dangerous to national security.

American labor leader and Socialist Party activist Eugene Debs also was arrested under the Espionage Act after giving a speech in 1918 encouraging others not to join the military. Debs argued that he was exercising his right to free speech and that the Espionage Act of 1917 was unconstitutional. In Debs v. United States the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act.

Freedom of Expression

The Supreme Court has interpreted artistic freedom broadly as a form of free speech.

In most cases, freedom of expression may be restricted only if it will cause direct and imminent harm. Shouting “fire!” in a crowded theater and causing a stampede would be an example of direct and imminent harm.

In deciding cases involving artistic freedom of expression the Supreme Court leans on a principle called “content neutrality.” Content neutrality means the government can’t censor or restrict expression just because some segment of the population finds the content offensive.

Free Speech in Schools

In 1965, students at a public high school in Des Moines, Iowa , organized a silent protest against the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to protest the fighting. The students were suspended from school. The principal argued that the armbands were a distraction and could possibly lead to danger for the students.

The Supreme Court didn’t bite—they ruled in favor of the students’ right to wear the armbands as a form of free speech in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District . The case set the standard for free speech in schools. However, First Amendment rights typically don’t apply in private schools.

What does free speech mean?; United States Courts . Tinker v. Des Moines; United States Courts . Freedom of expression in the arts and entertainment; ACLU .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Free Speech

Protecting free speech means protecting a free press, the democratic process, diversity of thought, and so much more. The ACLU has worked since 1920 to ensure that freedom of speech is protected for everyone.

What you need to know

10 Advocates on Why They Won’t Stand for Classroom Censorship

People across the country shared their thoughts about why inclusive education is crucial for students.

Ask an Expert: Is My Tweet Protected Speech?

Ask an expert: what are my speech rights at school.

10 Books Politicians Don’t Want You to Read

Defending Our Right to Learn

Explore more, what we're focused on.

Artistic Expression

The ACLU works in courts, legislatures, and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties that the Constitution and the laws of the United States guarantee everyone in this country.

Campaign Finance Reform

Employee speech and whistleblowers, freedom of the press, intellectual property, internet speech, photographers' rights, rights of protesters, student speech and privacy, what's at stake.

“Freedom of expression is the matrix, the indispensable condition, of nearly every other form of freedom.”

—U.S. Supreme Court Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo in Palko v. Connecticut

Freedom of speech, the press, association, assembly, and petition: This set of guarantees, protected by the First Amendment, comprises what we refer to as freedom of expression. It is the foundation of a vibrant democracy, and without it, other fundamental rights, like the right to vote, would wither away.

The fight for freedom of speech has been a bedrock of the ACLU’s mission since the organization was founded in 1920, driven by the need to protect the constitutional rights of conscientious objectors and anti-war protesters. The organization’s work quickly spread to combating censorship, securing the right to assembly, and promoting free speech in schools.

Almost a century later, these battles have taken on new forms, but they persist. The ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project continues to champion freedom of expression in its myriad forms — whether through protest, media, online speech, or the arts — in the face of new threats. For example, new avenues for censorship have arisen alongside the wealth of opportunities for speech afforded by the Internet. The threat of mass government surveillance chills the free expression of ordinary citizens, legislators routinely attempt to place new restrictions on online activity, and journalism is criminalized in the name of national security. The ACLU is always on guard to ensure that the First Amendment’s protections remain robust — in times of war or peace, for bloggers or the institutional press, online or off.

Over the years, the ACLU has represented or defended individuals engaged in some truly offensive speech. We have defended the speech rights of communists, Nazis, Ku Klux Klan members, accused terrorists, pornographers, anti-LGBT activists, and flag burners. That’s because the defense of freedom of speech is most necessary when the message is one most people find repulsive. Constitutional rights must apply to even the most unpopular groups if they’re going to be preserved for everyone.

Some examples of our free speech work from recent years include:

- In 2019, we filed a petition of certiorari on behalf of DeRay Mckesson, a prominent civil rights activist and Black Lives Matter movement organizer, urging the Supreme Court to overturn a lower court ruling that, if left standing, would dismantle civil rights era speech protections safeguarding the First Amendment right to protest.

- In 2019, we successfully challenged a spate of state anti-protest laws aimed at Indigenous and climate activists opposing pipeline construction.

- We’ve called on big social media companies to resist calls for censorship.

- We’re representing five former intelligence agency employees and military personnel in a lawsuit challenging the government’s pre-publication review system, which prohibits millions of former intelligence agency employees and military personnel from writing or speaking about topics related to their government service without first obtaining government approval.

- In 2018, we filed a friend-of-the-court brief arguing that the NRA’s lawsuit alleging that the state of New York violated its First Amendment rights should be allowed to proceed.

- In 2016, the we defended the First Amendment rights of environmental and racial justice activists in Uniontown, Alabama, who were sued for defamation after they organized against the town’s hazardous coal ash landfill.

- In 2014, the ACLU of Michigan filed an amicus brief arguing that the police violated the First Amendment by ejecting an anti-Muslim group called Bible Believers from a street festival based on others’ violent reactions to their speech.

Today, years of hard-fought civil liberty protections are under threat.

To influence lawmakers, we need everyone to get involved. Here is 1 action you can take today:

SpeechTexter is a free multilingual speech-to-text application aimed at assisting you with transcription of notes, documents, books, reports or blog posts by using your voice. This app also features a customizable voice commands list, allowing users to add punctuation marks, frequently used phrases, and some app actions (undo, redo, make a new paragraph).

SpeechTexter is used daily by students, teachers, writers, bloggers around the world.

It will assist you in minimizing your writing efforts significantly.

Voice-to-text software is exceptionally valuable for people who have difficulty using their hands due to trauma, people with dyslexia or disabilities that limit the use of conventional input devices. Speech to text technology can also be used to improve accessibility for those with hearing impairments, as it can convert speech into text.

It can also be used as a tool for learning a proper pronunciation of words in the foreign language, in addition to helping a person develop fluency with their speaking skills.

Accuracy levels higher than 90% should be expected. It varies depending on the language and the speaker.

No download, installation or registration is required. Just click the microphone button and start dictating.

Speech to text technology is quickly becoming an essential tool for those looking to save time and increase their productivity.

Powerful real-time continuous speech recognition

Creation of text notes, emails, blog posts, reports and more.

Custom voice commands

More than 70 languages supported

SpeechTexter is using Google Speech recognition to convert the speech into text in real-time. This technology is supported by Chrome browser (for desktop) and some browsers on Android OS. Other browsers have not implemented speech recognition yet.

Note: iPhones and iPads are not supported

List of supported languages:

Afrikaans, Albanian, Amharic, Arabic, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Basque, Bengali, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Burmese, Catalan, Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Filipino, Finnish, French, Galician, Georgian, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Javanese, Kannada, Kazakh, Khmer, Kinyarwanda, Korean, Lao, Latvian, Lithuanian, Macedonian, Malay, Malayalam, Marathi, Mongolian, Nepali, Norwegian Bokmål, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Sinhala, Slovak, Slovenian, Southern Sotho, Spanish, Sundanese, Swahili, Swati, Swedish, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tsonga, Tswana, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu, Uzbek, Venda, Vietnamese, Xhosa, Zulu.

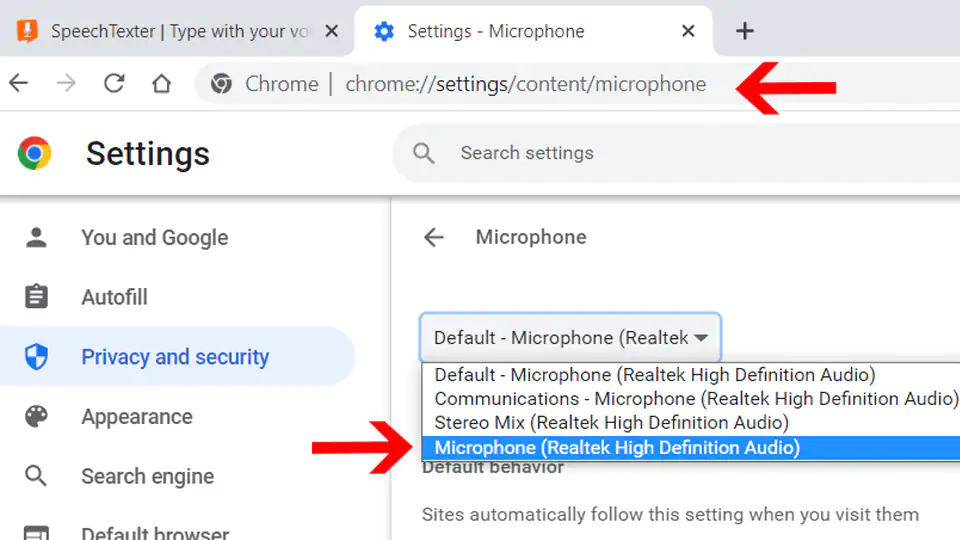

Instructions for web app on desktop (Windows, Mac, Linux OS)

Requirements: the latest version of the Google Chrome [↗] browser (other browsers are not supported).

1. Connect a high-quality microphone to your computer.

2. Make sure your microphone is set as the default recording device on your browser.

To go directly to microphone's settings paste the line below into Chrome's URL bar.

chrome://settings/content/microphone

To capture speech from video/audio content on the web or from a file stored on your device, select 'Stereo Mix' as the default audio input.

3. Select the language you would like to speak (Click the button on the top right corner).

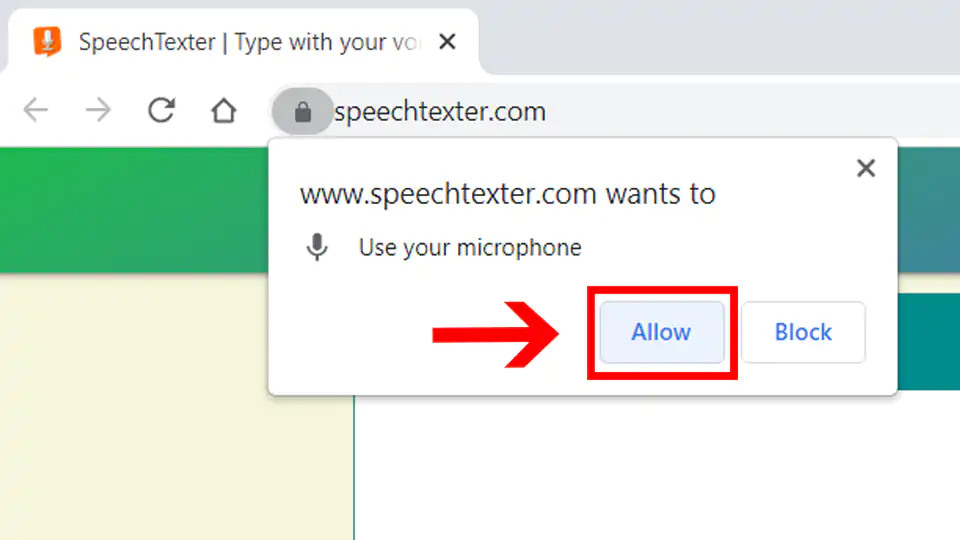

4. Click the "microphone" button. Chrome browser will request your permission to access your microphone. Choose "allow".

5. You can start dictating!

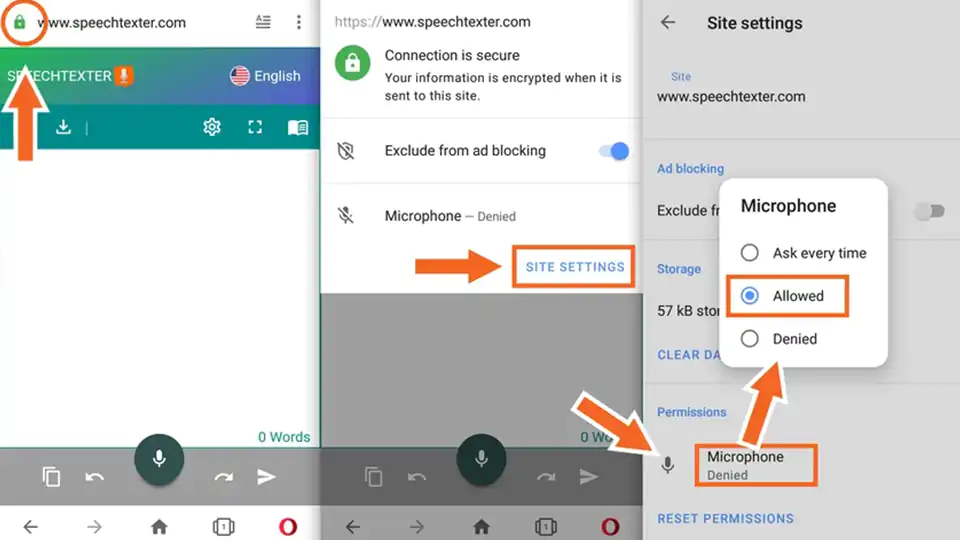

Instructions for the web app on a mobile and for the android app

Requirements: - Google app [↗] installed on your Android device. - Any of the supported browsers if you choose to use the web app.

Supported android browsers (not a full list): Chrome browser (recommended), Edge, Opera, Brave, Vivaldi.

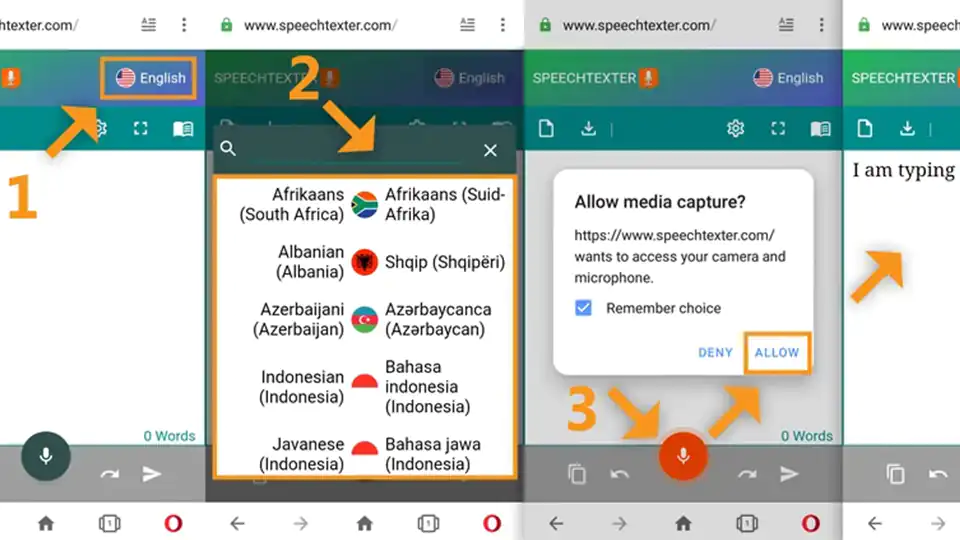

1. Tap the button with the language name (on a web app) or language code (on android app) on the top right corner to select your language.

2. Tap the microphone button. The SpeechTexter app will ask for permission to record audio. Choose 'allow' to enable microphone access.

3. You can start dictating!

Common problems on a desktop (Windows, Mac, Linux OS)

Error: 'speechtexter cannot access your microphone'..

Please give permission to access your microphone.

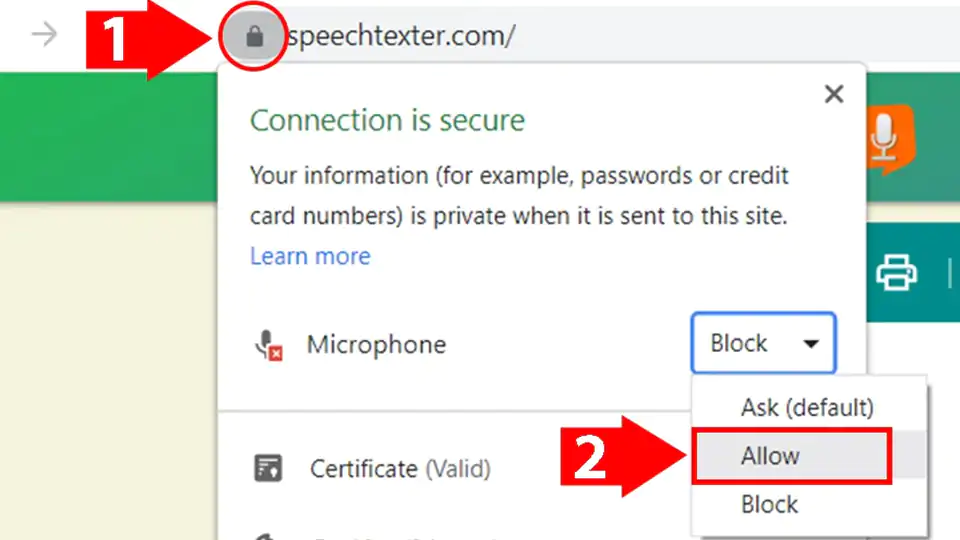

Click on the "padlock" icon next to the URL bar, find the "microphone" option, and choose "allow".

Error: 'No speech was detected. Please try again'.

If you get this error while you are speaking, make sure your microphone is set as the default recording device on your browser [see step 2].

If you're using a headset, make sure the mute switch on the cord is off.

Error: 'Network error'

The internet connection is poor. Please try again later.

The result won't transfer to the "editor".

The result confidence is not high enough or there is a background noise. An accumulation of long text in the buffer can also make the engine stop responding, please make some pauses in the speech.

The results are wrong.

Please speak loudly and clearly. Speaking clearly and consistently will help the software accurately recognize your words.

Reduce background noise. Background noise from fans, air conditioners, refrigerators, etc. can drop the accuracy significantly. Try to reduce background noise as much as possible.

Speak directly into the microphone. Speaking directly into the microphone enhances the accuracy of the software. Avoid speaking too far away from the microphone.

Speak in complete sentences. Speaking in complete sentences will help the software better recognize the context of your words.

Can I upload an audio file and get the transcription?

No, this feature is not available.

How do I transcribe an audio (video) file on my PC or from the web?

Playback your file in any player and hit the 'mic' button on the SpeechTexter website to start capturing the speech. For better results select "Stereo Mix" as the default recording device on your browser, if you are accessing SpeechTexter and the file from the same device.

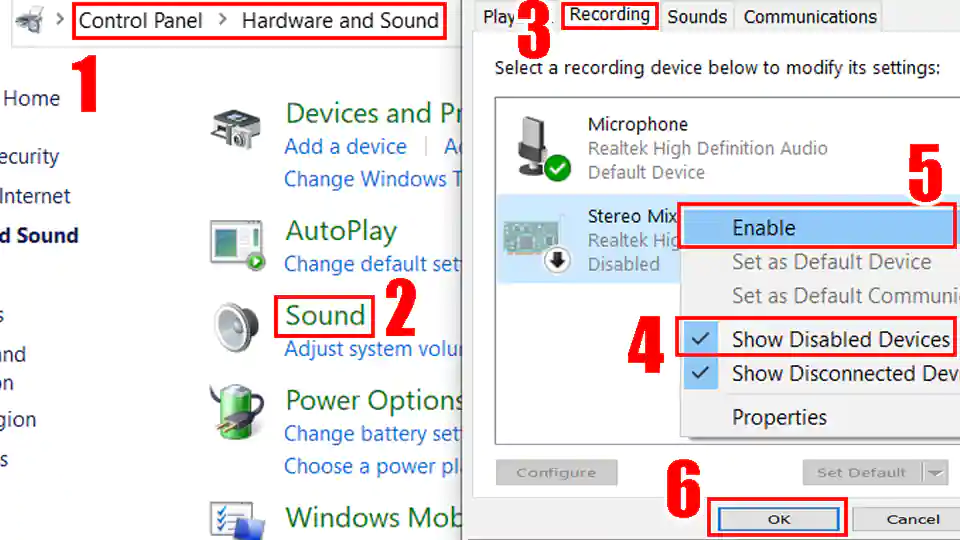

I don't see the "Stereo mix" option (Windows OS)

"Stereo Mix" might be hidden or it's not supported by your system. If you are a Windows user go to 'Control panel' → Hardware and Sound → Sound → 'Recording' tab. Right-click on a blank area in the pane and make sure both "View Disabled Devices" and "View Disconnected Devices" options are checked. If "Stereo Mix" appears, you can enable it by right clicking on it and choosing 'enable'. If "Stereo Mix" hasn't appeared, it means it's not supported by your system. You can try using a third-party program such as "Virtual Audio Cable" or "VB-Audio Virtual Cable" to create a virtual audio device that includes "Stereo Mix" functionality.

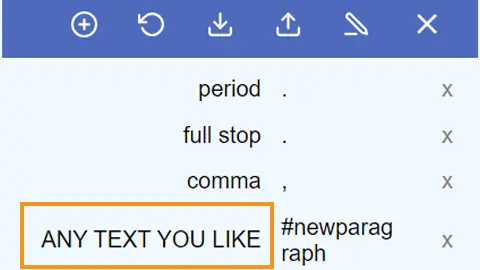

How to use the voice commands list?

The voice commands list allows you to insert the punctuation, some text, or run some preset functions using only your voice. On the first column you enter your voice command. On the second column you enter a punctuation mark or a function. Voice commands are case-sensitive. Available functions: #newparagraph (add a new paragraph), #undo (undo the last change), #redo (redo the last change)

To use the function above make a pause in your speech until all previous dictated speech appears in your note, then say "insert a new paragraph" and wait for the command execution.

Found a mistake in the voice commands list or want to suggest an update? Follow the steps below:

- Navigate to the voice commands list [↑] on this website.

- Click on the edit button to update or add new punctuation marks you think other users might find useful in your language.

- Click on the "Export" button located above the voice commands list to save your list in JSON format to your device.

Next, send us your file as an attachment via email. You can find the email address at the bottom of the page. Feel free to include a brief description of the mistake or the updates you're suggesting in the email body.

Your contribution to the improvement of the services is appreciated.

Can I prevent my custom voice commands from disappearing after closing the browser?

SpeechTexter by default saves your data inside your browser's cache. If your browsers clears the cache your data will be deleted. However, you can export your custom voice commands to your device and import them when you need them by clicking the corresponding buttons above the list. SpeechTexter is using JSON format to store your voice commands. You can create a .txt file in this format on your device and then import it into SpeechTexter. An example of JSON format is shown below:

{ "period": ".", "full stop": ".", "question mark": "?", "new paragraph": "#newparagraph" }

I lost my dictated work after closing the browser.

SpeechTexter doesn't store any text that you dictate. Please use the "autosave" option or click the "download" button (recommended). The "autosave" option will try to store your work inside your browser's cache, where it will remain until you switch the "text autosave" option off, clear the cache manually, or if your browser clears the cache on exit.

Common problems on the Android app

I get the message: 'speech recognition is not available'..

'Google app' from Play store is required for SpeechTexter to work. download [↗]

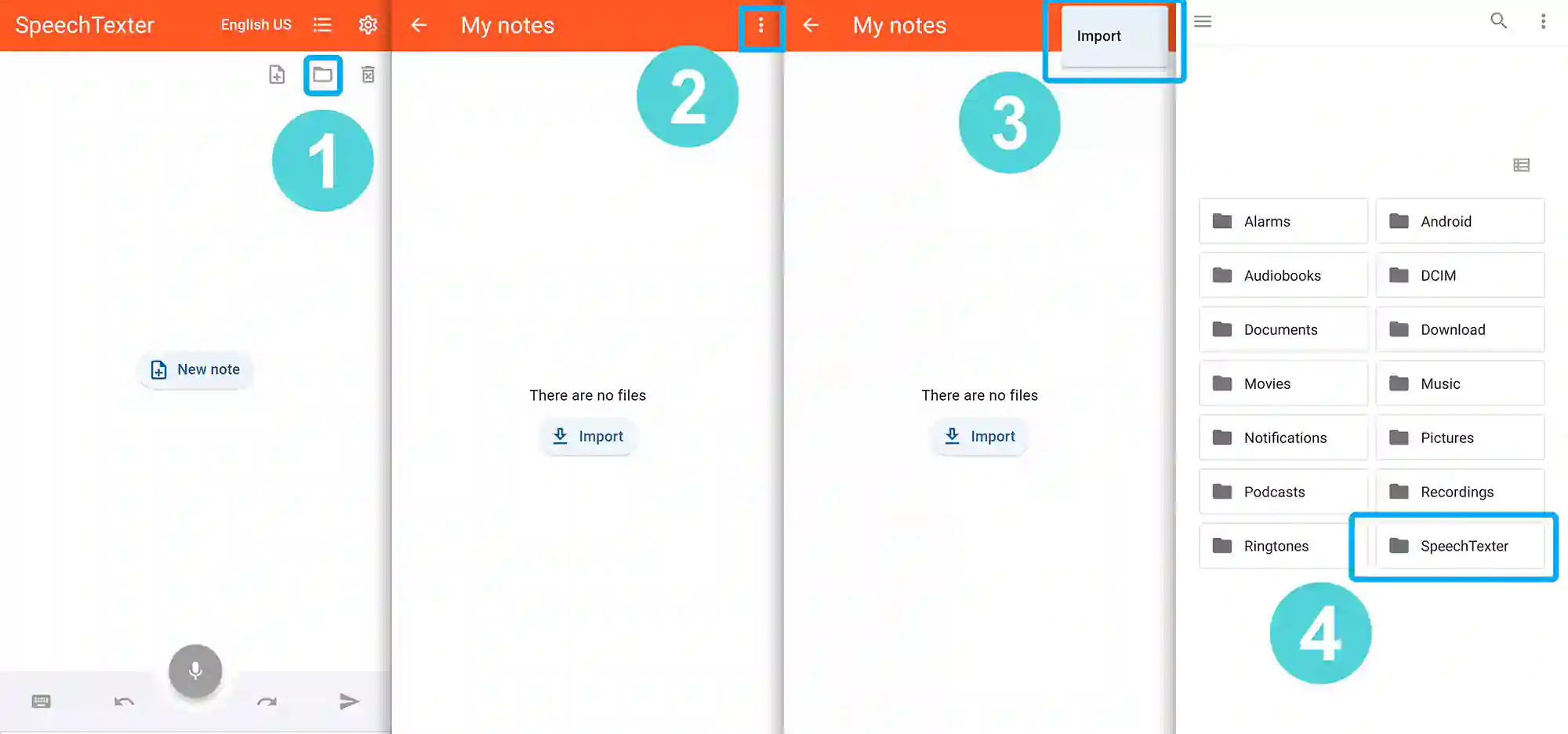

Where does SpeechTexter store the saved files?

Version 1.5 and above stores the files in the internal memory.

Version 1.4.9 and below stores the files inside the "SpeechTexter" folder at the root directory of your device.

After updating the app from version 1.x.x to version 2.x.x my files have disappeared

As a result of recent updates, the Android operating system has implemented restrictions that prevent users from accessing folders within the Android root directory, including SpeechTexter's folder. However, your old files can still be imported manually by selecting the "import" button within the Speechtexter application.

Common problems on the mobile web app

Tap on the "padlock" icon next to the URL bar, find the "microphone" option and choose "allow".

- TERMS OF USE

- PRIVACY POLICY

- Play Store [↗]

copyright © 2014 - 2024 www.speechtexter.com . All Rights Reserved.

AI Speech Writer

Craft compelling speeches with ai.

- Deliver a keynote address: Create an inspiring and memorable speech for conferences or events.

- Present a persuasive argument: Develop a compelling speech that effectively communicates your point of view.

- Teach or inform an audience: Craft an informative speech that engages listeners and helps them understand complex topics.

- Accept an award or honor: Write a heartfelt and gracious speech to express gratitude and share your journey.

- Commemorate special occasions: Generate a touching and memorable speech for weddings, anniversaries, or other celebrations.

New & Trending Tools

Ai text generator, webpage text extractor ai.

What this handout is about

This handout will help you create an effective speech by establishing the purpose of your speech and making it easily understandable. It will also help you to analyze your audience and keep the audience interested.

What’s different about a speech?

Writing for public speaking isn’t so different from other types of writing. You want to engage your audience’s attention, convey your ideas in a logical manner and use reliable evidence to support your point. But the conditions for public speaking favor some writing qualities over others. When you write a speech, your audience is made up of listeners. They have only one chance to comprehend the information as you read it, so your speech must be well-organized and easily understood. In addition, the content of the speech and your delivery must fit the audience.

What’s your purpose?

People have gathered to hear you speak on a specific issue, and they expect to get something out of it immediately. And you, the speaker, hope to have an immediate effect on your audience. The purpose of your speech is to get the response you want. Most speeches invite audiences to react in one of three ways: feeling, thinking, or acting. For example, eulogies encourage emotional response from the audience; college lectures stimulate listeners to think about a topic from a different perspective; protest speeches in the Pit recommend actions the audience can take.

As you establish your purpose, ask yourself these questions:

- What do you want the audience to learn or do?

- If you are making an argument, why do you want them to agree with you?

- If they already agree with you, why are you giving the speech?

- How can your audience benefit from what you have to say?

Audience analysis

If your purpose is to get a certain response from your audience, you must consider who they are (or who you’re pretending they are). If you can identify ways to connect with your listeners, you can make your speech interesting and useful.

As you think of ways to appeal to your audience, ask yourself:

- What do they have in common? Age? Interests? Ethnicity? Gender?

- Do they know as much about your topic as you, or will you be introducing them to new ideas?

- Why are these people listening to you? What are they looking for?

- What level of detail will be effective for them?

- What tone will be most effective in conveying your message?

- What might offend or alienate them?

For more help, see our handout on audience .

Creating an effective introduction

Get their attention, otherwise known as “the hook”.

Think about how you can relate to these listeners and get them to relate to you or your topic. Appealing to your audience on a personal level captures their attention and concern, increasing the chances of a successful speech. Speakers often begin with anecdotes to hook their audience’s attention. Other methods include presenting shocking statistics, asking direct questions of the audience, or enlisting audience participation.

Establish context and/or motive

Explain why your topic is important. Consider your purpose and how you came to speak to this audience. You may also want to connect the material to related or larger issues as well, especially those that may be important to your audience.

Get to the point

Tell your listeners your thesis right away and explain how you will support it. Don’t spend as much time developing your introductory paragraph and leading up to the thesis statement as you would in a research paper for a course. Moving from the intro into the body of the speech quickly will help keep your audience interested. You may be tempted to create suspense by keeping the audience guessing about your thesis until the end, then springing the implications of your discussion on them. But if you do so, they will most likely become bored or confused.

For more help, see our handout on introductions .

Making your speech easy to understand

Repeat crucial points and buzzwords.

Especially in longer speeches, it’s a good idea to keep reminding your audience of the main points you’ve made. For example, you could link an earlier main point or key term as you transition into or wrap up a new point. You could also address the relationship between earlier points and new points through discussion within a body paragraph. Using buzzwords or key terms throughout your paper is also a good idea. If your thesis says you’re going to expose unethical behavior of medical insurance companies, make sure the use of “ethics” recurs instead of switching to “immoral” or simply “wrong.” Repetition of key terms makes it easier for your audience to take in and connect information.

Incorporate previews and summaries into the speech

For example:

“I’m here today to talk to you about three issues that threaten our educational system: First, … Second, … Third,”

“I’ve talked to you today about such and such.”

These kinds of verbal cues permit the people in the audience to put together the pieces of your speech without thinking too hard, so they can spend more time paying attention to its content.

Use especially strong transitions

This will help your listeners see how new information relates to what they’ve heard so far. If you set up a counterargument in one paragraph so you can demolish it in the next, begin the demolition by saying something like,

“But this argument makes no sense when you consider that . . . .”

If you’re providing additional information to support your main point, you could say,

“Another fact that supports my main point is . . . .”

Helping your audience listen

Rely on shorter, simpler sentence structures.

Don’t get too complicated when you’re asking an audience to remember everything you say. Avoid using too many subordinate clauses, and place subjects and verbs close together.

Too complicated:

The product, which was invented in 1908 by Orville Z. McGillicuddy in Des Moines, Iowa, and which was on store shelves approximately one year later, still sells well.

Easier to understand:

Orville Z. McGillicuddy invented the product in 1908 and introduced it into stores shortly afterward. Almost a century later, the product still sells well.

Limit pronoun use

Listeners may have a hard time remembering or figuring out what “it,” “they,” or “this” refers to. Be specific by using a key noun instead of unclear pronouns.

Pronoun problem:

The U.S. government has failed to protect us from the scourge of so-called reality television, which exploits sex, violence, and petty conflict, and calls it human nature. This cannot continue.

Why the last sentence is unclear: “This” what? The government’s failure? Reality TV? Human nature?

More specific:

The U.S. government has failed to protect us from the scourge of so-called reality television, which exploits sex, violence, and petty conflict, and calls it human nature. This failure cannot continue.

Keeping audience interest

Incorporate the rhetorical strategies of ethos, pathos, and logos.

When arguing a point, using ethos, pathos, and logos can help convince your audience to believe you and make your argument stronger. Ethos refers to an appeal to your audience by establishing your authenticity and trustworthiness as a speaker. If you employ pathos, you appeal to your audience’s emotions. Using logos includes the support of hard facts, statistics, and logical argumentation. The most effective speeches usually present a combination these rhetorical strategies.

Use statistics and quotations sparingly

Include only the most striking factual material to support your perspective, things that would likely stick in the listeners’ minds long after you’ve finished speaking. Otherwise, you run the risk of overwhelming your listeners with too much information.

Watch your tone

Be careful not to talk over the heads of your audience. On the other hand, don’t be condescending either. And as for grabbing their attention, yelling, cursing, using inappropriate humor, or brandishing a potentially offensive prop (say, autopsy photos) will only make the audience tune you out.

Creating an effective conclusion

Restate your main points, but don’t repeat them.

“I asked earlier why we should care about the rain forest. Now I hope it’s clear that . . .” “Remember how Mrs. Smith couldn’t afford her prescriptions? Under our plan, . . .”

Call to action

Speeches often close with an appeal to the audience to take action based on their new knowledge or understanding. If you do this, be sure the action you recommend is specific and realistic. For example, although your audience may not be able to affect foreign policy directly, they can vote or work for candidates whose foreign policy views they support. Relating the purpose of your speech to their lives not only creates a connection with your audience, but also reiterates the importance of your topic to them in particular or “the bigger picture.”

Practicing for effective presentation

Once you’ve completed a draft, read your speech to a friend or in front of a mirror. When you’ve finished reading, ask the following questions:

- Which pieces of information are clearest?

- Where did I connect with the audience?

- Where might listeners lose the thread of my argument or description?

- Where might listeners become bored?

- Where did I have trouble speaking clearly and/or emphatically?

- Did I stay within my time limit?

Other resources

- Toastmasters International is a nonprofit group that provides communication and leadership training.

- Allyn & Bacon Publishing’s Essence of Public Speaking Series is an extensive treatment of speech writing and delivery, including books on using humor, motivating your audience, word choice and presentation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Boone, Louis E., David L. Kurtz, and Judy R. Block. 1997. Contemporary Business Communication . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ehrlich, Henry. 1994. Writing Effective Speeches . New York: Marlowe.

Lamb, Sandra E. 1998. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write . Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Freedom of Speech

[ Editor’s Note: The following new entry by Jeffrey W. Howard replaces the former entry on this topic by the previous author. ]

Human beings have significant interests in communicating what they think to others, and in listening to what others have to say. These interests make it difficult to justify coercive restrictions on people’s communications, plausibly grounding a moral right to speak (and listen) to others that is properly protected by law. That there ought to be such legal protections for speech is uncontroversial among political and legal philosophers. But disagreement arises when we turn to the details. What are the interests or values that justify this presumption against restricting speech? And what, if anything, counts as an adequate justification for overcoming the presumption? This entry is chiefly concerned with exploring the philosophical literature on these questions.

The entry begins by distinguishing different ideas to which the term “freedom of speech” can refer. It then reviews the variety of concerns taken to justify freedom of speech. Next, the entry considers the proper limits of freedom of speech, cataloging different views on when and why restrictions on communication can be morally justified, and what considerations are relevant when evaluating restrictions. Finally, it considers the role of speech intermediaries in a philosophical analysis of freedom of speech, with special attention to internet platforms.

1. What is Freedom of Speech?

2.1 listener theories, 2.2 speaker theories, 2.3 democracy theories, 2.4 thinker theories, 2.5 toleration theories, 2.6 instrumental theories: political abuse and slippery slopes, 2.7 free speech skepticism, 3.1 absoluteness, coverage, and protection, 3.2 the limits of free speech: external constraints, 3.3 the limits of free speech: internal constraints, 3.4 proportionality: chilling effects and political abuse, 3.5 necessity: the counter-speech alternative, 4. the future of free speech theory: platform ethics, other internet resources, related entries.

In the philosophical literature, the terms “freedom of speech”, “free speech”, “freedom of expression”, and “freedom of communication” are mostly used equivalently. This entry will follow that convention, notwithstanding the fact that these formulations evoke subtly different phenomena. For example, it is widely understood that artistic expressions, such as dancing and painting, fall within the ambit of this freedom, even though they don’t straightforwardly seem to qualify as speech , which intuitively connotes some kind of linguistic utterance (see Tushnet, Chen, & Blocher 2017 for discussion). Still, they plainly qualify as communicative activity, conveying some kind of message, however vague or open to interpretation it may be.

Yet the extension of “free speech” is not fruitfully specified through conceptual analysis alone. The quest to distinguish speech from conduct, for the purpose of excluding the latter from protection, is notoriously thorny (Fish 1994: 106), despite some notable attempts (such as Greenawalt 1989: 58ff). As John Hart Ely writes concerning Vietnam War protesters who incinerated their draft cards, such activity is “100% action and 100% expression” (1975: 1495). It is only once we understand why we should care about free speech in the first place—the values it instantiates or serves—that we can evaluate whether a law banning the burning of draft cards (or whatever else) violates free speech. It is the task of a normative conception of free speech to offer an account of the values at stake, which in turn can illuminate the kinds of activities wherein those values are realized, and the kinds of restrictions that manifest hostility to those values. For example, if free speech is justified by the value of respecting citizens’ prerogative to hear many points of view and to make up their own minds, then banning the burning of draft cards to limit the views to which citizens will be exposed is manifestly incompatible with that purpose. If, in contrast, such activity is banned as part of a generally applied ordinance restricting fires in public, it would likely raise no free-speech concerns. (For a recent analysis of this issue, see Kramer 2021: 25ff).

Accordingly, the next section discusses different conceptions of free speech that arise in the philosophical literature, each oriented to some underlying moral or political value. Before turning to the discussion of those conceptions, some further preliminary distinctions will be useful.

First, we can distinguish between the morality of free speech and the law of free speech. In political philosophy, one standard approach is to theorize free speech as a requirement of morality, tracing the implications of such a theory for law and policy. Note that while this is the order of justification, it need not be the order of investigation; it is perfectly sensible to begin by studying an existing legal protection for speech (such as the First Amendment in the U.S.) and then asking what could justify such a protection (or something like it).