Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn Icon

Report recommends changes in screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip :

However, most of the guidance remains unchanged from a 2000 clinical practice guideline.

Evaluation and Referral for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Infants , from the AAP Section on Orthopaedics, is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3107 and will be published in the December issue of Pediatrics .

Latest guidance

- If parents choose to swaddle their infants, encourage hip-healthy swaddling that allows freedom of hip motion and avoids forced position of hip extension and adduction (see http://bit.ly/2fh8gZ8 ).

- Risk factors for which the pediatrician may wish to consider an imaging study in the child with a normal screening physical examination are:

- breech position in the third trimester — both males and females;

- family history of DDH;

- history of improper swaddling; and

- history of abnormal hip physical examination in the neonatal period, which subsequently normalizes.

Periodic hip examination crucial

The report reinforces the earlier advice to carefully perform and document the periodic hip examination until the child is walking. This exam should include the Ortolani test (see resources), hip abduction, gluteal or major thigh crease asymmetry (low specificity) and leg length inequality (Galeazzi sign). The importance of the periodic exam cannot be overemphasized because other than female gender, most children with DDH do not have risk factors. In other words, risk factors are poor indicators of DDH, and all children need to undergo periodic hip examination until they begin walking.

The report confirmed that no screening method completely eliminates the risk of late presentation of DDH.

Use of imaging

When an imaging study is indicated, whether by risk factors or by suspicious physical examination, it is best to defer diagnostic hip ultrasound until age 6 weeks (adjust for prematurity) or plain anteroposterior pelvis radiograph at ages 4-6 months. Ultrasonography may be done earlier in guiding treatment of an Ortolani-positive hip. Initial diagnostic ultrasound usually is deferred until after age 6 weeks because of the high rate of false positives or immature hips, which spontaneously resolve most often by age 6 weeks.

In using imaging for assessment of babies with one or more risk factors but negative physical exam, there is no proven benefit to ultrasound at 6 weeks vs. radiograph at 4-6 months; the report recommends choosing based on local conditions and availability of experienced, trained pediatric hip sonographers.

Regarding breech position in the third trimester as a risk factor, the term breech is used broadly: It doesn’t matter if the child is delivered breech, turns or is turned.

When considering family history as a risk factor, the term again is used broadly without specificity. Clinicians may include early (age younger than 40 years) hip replacement for dysplasia in a close relative.

Finally, there is sensitivity to the medicolegal concerns of AAP members. This report provides only guidance; there is no DDH screening method that completely eliminates late presenting DDH or mild degrees of dysplasia. When in doubt, it’s best to make a referral and listen carefully to any parental concerns.

Drs. Shaw and Segal are lead authors of the clinical report and members of the AAP Section on Orthopaedics Executive Committee.

- A link to a video showing how to perform the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers is on the AAP Section on Orthopaedics website.

- International Hip Dysplasia Institute

Advertising Disclaimer »

Email alerts

1. 4 million children lose Medicaid, CHIP insurance after public health emergency protections end

2. Autism diagnosis in primary care promotes equity, benefits families

3. Long hours, guilt, more compassion: Pediatrician moms share stresses, rewards

April issue digital edition

Subscribe to AAP News

Column collections

Topic collections

Affiliations

Advertising.

- Submit a story

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- Online ISSN 1556-3332

- Print ISSN 1073-0397

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

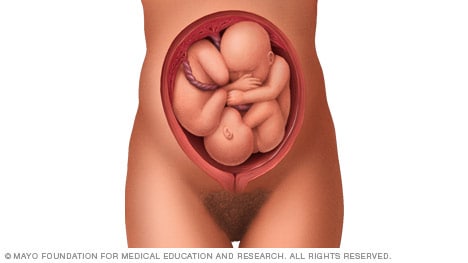

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

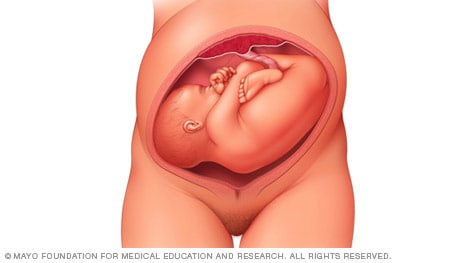

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

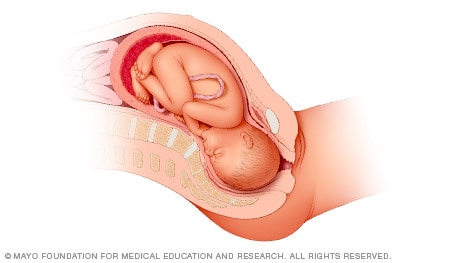

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

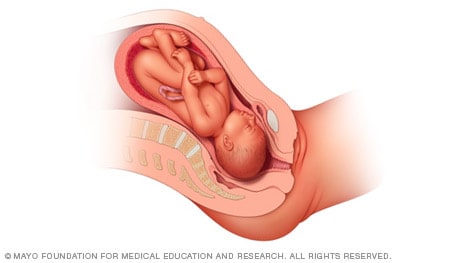

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

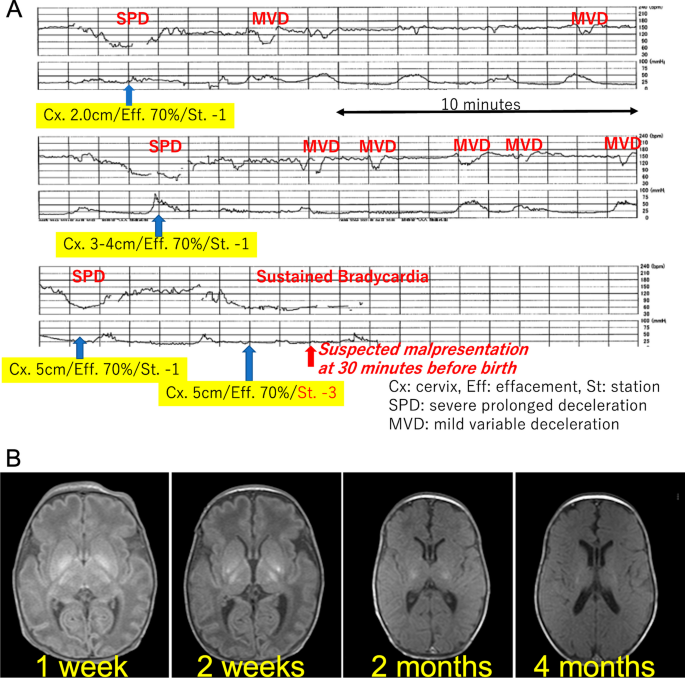

- A 28-year-old G1P0 woman at 37 weeks of gestation presents to her obstetrician for a prenatal care appointment. She describes feeling some soreness under her ribs in the past few weeks and feels her baby kicking in her lower abdomen. An ultrasound is performed and is seen in the image. The obstetrician describes management approaches, including an external cephalic version before labor.

- flexion of the hips and knees

- some deflexion of one hip and knee

- flexion of both hips with extension of both knees

- 3-4% of all deliveries

- 22-25% of births before 28 weeks of gestation

- 7-15% of births at 32 weeks of gestation

- 3-4% of births at term

- prematurity

- uterine malformations

- uterine fibroids

- polyhydramnios

- placenta previa

- multiple gestations

- subcostal discomfort (due to fetal head in the uterine fundus)

- feeling of kicking in the lower abdomen

- presence of soft mass (buttocks) and absence of hard fetal skull on transabdominal examination of the lower uterine segment

- when cervix is dilated

- detection of breech presentation prior to 37 weeks does not warrant intervention

- fetal head in the uterine fundus

- buttocks in the lower uterine segment

- extension angle > 90 degrees

- at 37 weeks gestation or later

- perform trial of vaginal delivery if the version is successful

- may be planned for breech presentation, without a trial of external cephalic version

- may be performed if trial of vaginal delivery is unsuccessful after external cephalic labor

- ↑ up to 4-fold with breech presetnation

- associated with malformations, prematurity, and intrauterine fetal demise

- 17% of preterm breech deliveries

- 9% of term breech deliveries

- abnormalities include CNS malformations, neck masses, and aneuploidy

- - Breech Presentation

Please Login to add comment

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- Identification of breech presentation

Evidence review L

NICE Guideline, No. 201

National Guideline Alliance (UK) .

- Copyright and Permissions

Review question

What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation?

Introduction

Breech presentation in late pregnancy may result in prolonged or obstructed labour for the woman. There are interventions that can correct or assist breech presentation which are important for the woman’s and the baby’s health. This review aims to determine the most effective way of identifying a breech presentation in late pregnancy.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) characteristics of this review.

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For further details see the review protocol in appendix A .

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014 . Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A .

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s conflicts of interest policy .

Clinical evidence

Included studies.

One single centre randomised controlled trial (RCT) was included in this review ( McKenna 2003 ). The study was carried out in Northern Ireland, UK. The study compared ultrasound examination at 30-32 and 36-37 weeks with maternal abdomen palpation during the same gestation period. The intervention group in the study had the ultrasound scans in addition to the abdomen palpation, while the control group had only the abdomen palpation. Clinical management options reported in the study based on the ultrasound scan or the abdomen palpation include referral for full biophysical assessment which included umbilical artery Doppler ultrasound, early antenatal review, admission to antenatal ward, and induction of labour.

The included study is summarised in Table 2 .

See the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C .

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this review are listed, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in appendix K .

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Summaries of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 2 .

Summary of included studies.

See the full evidence tables in appendix D . No meta-analysis was conducted (and so there are no forest plots in appendix E ).

Quality assessment of clinical outcomes included in the evidence review

See the evidence profiles in appendix F .

Economic evidence

One study, a cost utility analysis was included ( Wastlund 2019 ).

See the literature search strategy in appendix B and economic study selection flow chart in appendix G .

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in appendix K .

Summary of studies included in the economic evidence review

For full details of the economic evidence, see the economic evidence tables in appendix H and economic evidence profiles in appendix I .

Wastlund (2019) assessed the cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation at 36 weeks’ gestational age in nulliparous woman (N=3879). The comparator was selective ultrasound scanning which was reported as current practice. In this instance, fetal presentation was assessed by palpation of the abdomen by a midwife, obstetrician or general practitioner. The sensitivity of this method ranges between 57%-70% whereas ultrasound scanning is detected with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity. Women in the selective ultrasound scan arm only received an ultrasound scan after detection of a breech presentation by abdominal palpation. Where a breech was detected, a woman was offered external cephalic version (ECV). The structure of the model undertook a decision tree, with end states being the mode of birth; either vaginal, elective or emergency caesarean section. Long term health outcomes were modelled based on the mortality risk associated with each mode of birth. Average lifetime quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were estimated from Euroqol general UK population values.

Only the probabilistic results (n=100000 simulations) were reported which showed that on average, universal ultrasound resulted in an absolute decrease in breech deliveries by 0.39% compared with selective ultrasound scanning. The expected cost per person with breech presentation of universal ultrasound was £2957 (95% Credibility Interval [CrI]: £2922 to £2991), compared to £2,949 (95%CrI: £2915 to £2984) from selective ultrasound. The expected QALYs per person was 24.27615 in the universal ultrasound cohort and 24.27582 in the selective ultrasound cohort. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) from the probabilistic analysis was £23611 (95%CrI: £8184 to £44851).

A series of one-way sensitivity analysis were conducted which showed that the most important cost parameter was the unit cost of a universal ultrasound scan. This parameter is particularly noteworthy as the study costed this scan at a much lower value than the ‘standard antenatal ultrasound’ scan in NHS reference costs on the basis that such a scan can be performed by a midwife during a routine antenatal care visit in primary care. According to the NICE guideline manual economic evaluation checklist this model was assessed as being directly applicable with potentially severe limitations. The limitations were mostly attributable to the limitations of the clinical inputs.

Economic model

No economic modelling was undertaken for this review because the committee agreed that other topics were higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Evidence statements

Clinical evidence statements, comparison 1. routine ultrasound scan versus selective ultrasound scan, critical outcomes, unexpected breech presentation in labour.

No evidence was identified to inform this outcome.

Mode of birth

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=1993) showed that there is no clinically important difference between routine ultrasound scan at 36-37 weeks and selective ultrasound scan on the number of women who had elective caesarean section: RR 1.22 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.63).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=1993) showed that there is no clinically important difference between routine ultrasound scan at 36-37 weeks and selective ultrasound scan on number of women who had emergency caesarean section: RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.60).

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=1993) showed that there is no clinically important difference between routine ultrasound scan at 36-37 weeks and selective ultrasound scan on number of women who had vaginal birth: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.01).

Important outcomes

Maternal anxiety, women’s experience and satisfaction of care, gestational age at birth.

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=1993) showed that there is no clinically important difference between routine ultrasound scan at 36-37 weeks and selective ultrasound scan on the number of babies’ born between 39-42 gestational weeks: RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.02).

Admission to neonatal unit

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=1993) showed that there is no clinically important difference between routine ultrasound scan at 36-37 weeks and selective ultrasound scan on the number of babies admitted into the neonatal unit: RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.35).

Economic evidence statements

One directly applicable cost-utility analysis from the UK with potentially serious limitations compared universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation at 36 weeks’ gestational age with selective ultrasound scanning, stated as current practice. Universal ultrasound scanning was found to be borderline cost effective; the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was £23611 per QALY gained. The cost of the scan was seen to be a key driver in the cost effectiveness result.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence, the outcomes that matter most.

Unexpected breech presentation in labour and mode of birth were prioritised as critical outcomes by the committee. This reflects the different options available to women with a known breech presentation in pregnancy and the different choices that women make. There are some women and/or clinicians who may feel uncomfortable with the risks of aiming for vaginal breech birth, and for these women and/or clinicians avoiding an unexpected breech presentation in labour would be the preferred option.

As existing evidence suggests that aiming for vaginal breech birth carries greater risk to the fetus than planned caesarean birth, it is important to consider whether earlier detection of the breech presentation would reduce the risk of these outcomes.

The committee agreed that maternal anxiety and women’s experience and satisfaction of care were important outcomes to consider as the introduction of an additional routine scan during pregnancy could have a treatment burden for women. Gestational age at birth and admission to neonatal unit were also chosen as important outcomes as the committee wanted to find out whether earlier detection of breech presentation would have an impact on whether the baby was born preterm, and as a consequence admitted to the neonatal unit. These outcomes were agreed to be important rather than critical as they are indirect outcomes of earlier detection of breech presentation.

The quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence ranged from low to high. Most of the evidence was rated high or moderate, with only 1 outcome rated as low. The quality of the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision around the effect estimates for emergency caesarean section, elective caesarean section and admissions to neonatal unit.

No evidence was identified for the following outcomes: unexpected breech presentation in labour, maternal anxiety, women’s experiences and satisfaction of care.

The committee had hoped to find evidence that would inform whether early identification of breech presentation had an impact on preterm births, and although the review reported evidence for gestational age as birth, the available evidence was for births 39-42 weeks of gestation.

Benefits and harms

The available evidence compared routine ultrasound scanning with selective ultrasound scanning, and found no clinically important differences for mode of birth, gestational age at birth, or admissions to the neonatal unit. However, the committee discussed that it was important to note that the study did not focus on identifying breech presentation. The committee discussed the differences between the intervention in the study, which was an ultrasound scan to assess placental maturity, liquor volume, and fetal weight, to an ultrasound scan used to detect breech presentation. Whilst the ultrasound scan in the study has the ability to determine breech presentation, there are additional and costlier training required for the assessment of the other criteria. As such, it is important to separate the interventions. The committee also highlighted that the study did not look at whether an identification of breech presentation had an impact on the outcomes which were selected for this review.

In light of this, the committee felt that they were unable to reach a conclusion as to whether routine scanning to identify breech presentation, was associated with any benefits or harms. The committee agreed that while this review suggests routine ultrasound scanning to be no more effective than selective scanning, it does not definitively establish equivalence. Therefore, the committee agreed to recommend a continuation of the current practice with selective scanning and make a research recommendation to compare the clinical and cost effectiveness of routine ultrasound scanning versus selective ultrasound scanning from 36 weeks to identify fetal breech presentation.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

The committee acknowledged that there was included economic evidence on the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation.

The 1 included study suggested that offering a routine scan for breech is borderline cost effective. A key driver of cost effectiveness was the cost of the scan, which was substantially lower in the economic model than the figure quoted in NHS reference costs for routine ultrasound scanning. The committee noted that a scan for breech presentation only is a simpler technique and uses a cheaper machine. The committee agreed that the other costing assumptions presented in the study seemed appropriate.

However, the committee expressed concerns about the cohort study which underpinned the economic analysis which had a high risk of bias. The committee noted that a number of assumptions in the model which were key drivers of cost effectiveness, including the palpation diagnosis rates and prevalence of breech position, were from this 1 cohort study. This increased the uncertainty around the cost effectiveness of the routine scan. The committee also noted that, whilst the cost of the scan was fairly inexpensive, the resource impact would be substantial if a routine scan for breech presentation was offered to all pregnant women.

Overall, the committee felt that the clinical and cost effectiveness evidence presented was not strong enough to recommend offering a routine ultrasound scan given the potential for a significant resource impact. The recommendation to offer abdominal palpation to all pregnant women, and to offer an ultrasound scan where breech is suspected reflects current practice and so no substantial resource impact is anticipated.

McKenna 2003

Wastlund 2019

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 244K)

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Literature search strategies for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 370K)

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Clinical study selection for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 117K)

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Clinical evidence tables for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 213K)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Forest plots for review question: what is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation.

This section includes forest plots only for outcomes that are meta-analysed. Outcomes from single studies are not presented here, but the quality assessment for these outcomes is provided in the GRADE profiles in appendix F .

Appendix F. GRADE tables

GRADE tables for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 196K)

Appendix G. Economic evidence study selection

Economic evidence study selection for review question: what is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation.

A single economic search was undertaken for all topics included in the scope of this guideline. One economic study was identified which was applicable to this review question. See supplementary material 2 for details.

Appendix H. Economic evidence tables

Economic evidence tables for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 143K)

Appendix I. Economic evidence profiles

Economic evidence profiles for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 129K)

Appendix J. Economic analysis

Economic evidence analysis for review question: what is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation.

No economic analysis was conducted for this review question.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Excluded clinical and economic studies for review question: what is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation, clinical studies, table 8 excluded studies and reasons for their exclusion.

View in own window

Economic studies

A single economic search was undertaken for all topics included in the scope of this guideline. No economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question. See supplementary material 2 for details.

Appendix L. Research recommendations

Research recommendations for review question: What is the effectiveness of routine scanning between 36+0 and 38+6 weeks of pregnancy compared to standard care regarding breech presentation? (PDF, 164K)

Evidence reviews underpinning recommendations 1.2.36 to 1.2.37

These evidence reviews were developed by the National Guideline Alliance, which is a part of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer : The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government , Scottish Government , and Northern Ireland Executive . All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- Cite this Page National Guideline Alliance (UK). Identification of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review L. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2021 Aug. (NICE Guideline, No. 201.)

- PDF version of this title (518K)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- NICE Evidence Reviews Collection

Related NICE guidance and evidence

- NICE Guideline 201: Antenatal care

Supplemental NICE documents

- Supplement 1: Methods (PDF)

- Supplement 2: Health economics (PDF)

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Management of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review M [ 2021] Review Management of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review M National Guideline Alliance (UK). 2021 Aug

- Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. [J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009] Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. Kotaska A, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R, MATERNAL FETAL MEDICINE COMMITTEE. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009 Jun; 31(6):557-566.

- [The effect of the woman's age on the course of pregnancy and labor in breech presentation]. [Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 1996] [The effect of the woman's age on the course of pregnancy and labor in breech presentation]. Dimitrov A, Borisov S, Nalbanski B, Kovacheva M, Chintolova G, Dzherov L. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 1996; 35(1-2):7-9.

- Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005] Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18; (2):CD003928. Epub 2005 Apr 18.

- Review Hands and knees posture in late pregnancy or labour for fetal malposition (lateral or posterior). [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005] Review Hands and knees posture in late pregnancy or labour for fetal malposition (lateral or posterior). Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18; (2):CD001063. Epub 2005 Apr 18.

Recent Activity

- Identification of breech presentation Identification of breech presentation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Labor & Delivery

What Causes Breech Presentation?

Learn more about the types, causes, and risks of breech presentation, along with how breech babies are typically delivered.

What Is Breech Presentation?

Types of breech presentation, what causes a breech baby, can you turn a breech baby, how are breech babies delivered.

FatCamera/Getty Images

Toward the end of pregnancy, your baby will start to get into position for delivery, with their head pointed down toward the vagina. This is otherwise known as vertex presentation. However, some babies turn inside the womb so that their feet or buttocks are poised to be delivered first, which is commonly referred to as breech presentation, or a breech baby.

As you near the end of your pregnancy journey, an OB-GYN or health care provider will check your baby's positioning. You might find yourself wondering: What causes breech presentation? Are there risks involved? And how are breech babies delivered? We turned to experts and research to answer some of the most common questions surrounding breech presentation, along with what causes this positioning in the first place.

During your pregnancy, your baby constantly moves around the uterus. Indeed, most babies do somersaults up until the 36th week of pregnancy , when they pick their final position in the womb, says Laura Riley , MD, an OB-GYN in New York City. Approximately 3-4% of babies end up “upside-down” in breech presentation, with their feet or buttocks near the cervix.

Breech presentation is typically diagnosed during a visit to an OB-GYN, midwife, or health care provider. Your physician can feel the position of your baby's head through your abdominal wall—or they can conduct a vaginal exam if your cervix is open. A suspected breech presentation should ultimately be confirmed via an ultrasound, after which you and your provider would have a discussion about delivery options, potential issues, and risks.

There are three types of breech babies: frank, footling, and complete. Learn about the differences between these breech presentations.

Frank Breech

With frank breech presentation, your baby’s bottom faces the cervix and their legs are straight up. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

Footling Breech

Like its name suggests, a footling breech is when one (single footling) or both (double footling) of the baby's feet are in the birth canal, where they’re positioned to be delivered first .

Complete Breech

In a complete breech presentation, baby’s bottom faces the cervix. Their legs are bent at the knees, and their feet are near their bottom. A complete breech is the least common type of breech presentation.

Other Types of Mal Presentations

The baby can also be in a transverse position, meaning that they're sideways in the uterus. Another type is called oblique presentation, which means they're pointing toward one of the pregnant person’s hips.

Typically, your baby's positioning is determined by the fetus itself and the shape of your uterus. Because you can't can’t control either of these factors, breech presentation typically isn’t considered preventable. And while the cause often isn't known, there are certain risk factors that may increase your risk of a breech baby, including the following:

- The fetus may have abnormalities involving the muscular or central nervous system

- The uterus may have abnormal growths or fibroids

- There might be insufficient amniotic fluid in the uterus (too much or too little)

- This isn’t your first pregnancy

- You have a history of premature delivery

- You have placenta previa (the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix)

- You’re pregnant with multiples

- You’ve had a previous breech baby

In some cases, your health care provider may attempt to help turn a baby in breech presentation through a procedure known as external cephalic version (ECV). This is when a health care professional applies gentle pressure on your lower abdomen to try and coax your baby into a head-down position. During the entire procedure, the fetus's health will be monitored, and an ECV is often performed near a delivery room, in the event of any potential issues or complications.

However, it's important to note that ECVs aren't for everyone. If you're carrying multiples, there's health concerns about you or the baby, or you've experienced certain complications with your placenta or based on placental location, a health care provider will not attempt an ECV.

The majority of breech babies are born through C-sections . These are usually scheduled between 38 and 39 weeks of pregnancy, before labor can begin naturally. However, with a health care provider experienced in delivering breech babies vaginally, a natural delivery might be a safe option for some people. In fact, a 2017 study showed similar complication and success rates with vaginal and C-section deliveries of breech babies.

That said, there are certain known risks and complications that can arise with an attempt to deliver a breech baby vaginally, many of which relate to problems with the umbilical cord. If you and your medical team decide on a vaginal delivery, your baby will be monitored closely for any potential signs of distress.

Ultimately, it's important to know that most breech babies are born healthy. Your provider will consider your specific medical condition and the position of your baby to determine which type of delivery will be the safest option for a healthy and successful birth.

ACOG. If Your Baby Is Breech .

American Pregnancy Association. Breech Presentation .

Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Mount Sinai. Breech Babies .

Takeda J, Ishikawa G, Takeda S. Clinical Tips of Cesarean Section in Case of Breech, Transverse Presentation, and Incarcerated Uterus . Surg J (N Y). 2020 Mar 18;6(Suppl 2):S81-S91. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702985. PMID: 32760790; PMCID: PMC7396468.

Shanahan MM, Gray CJ. External Cephalic Version . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Fonseca A, Silva R, Rato I, Neves AR, Peixoto C, Ferraz Z, Ramalho I, Carocha A, Félix N, Valdoleiros S, Galvão A, Gonçalves D, Curado J, Palma MJ, Antunes IL, Clode N, Graça LM. Breech Presentation: Vaginal Versus Cesarean Delivery, Which Intervention Leads to the Best Outcomes? Acta Med Port. 2017 Jun 30;30(6):479-484. doi: 10.20344/amp.7920. Epub 2017 Jun 30. PMID: 28898615.

Related Articles

Ultrasound Examination for Infants Born Breech by Elective Cesarean Section With a Normal Hip Exam for Instability

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Orthopedics, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA.

- PMID: 26491915

- DOI: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000668

Introduction: Because of the risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants born breech-despite a normal physical exam-the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines recommend ultrasound (US) hip imaging at 6 weeks of age for breech females and optional imaging for breech males. The purpose of this study is to report US results and follow-up of infants born breech with a normal physical exam.

Methods: The electronic medical record for children born at 1 hospital from 2008 to 2011 was reviewed. Data were analyzed for sex, birth weight, breech position, birth order, ethnicity, US and x-ray results, follow-up, and cost.

Results: A total of 237 infants were born breech with a normal physical examination, all delivered by cesarean section. Of the infants, 55% were male and 45% female. About 151 breech infants (64%) with a normal Barlow and Ortolani exam had a precautionary hip US as recommended by the AAP performed at an average of 7 weeks of age. Eighty-six breech infants (35%) did not have an US and were followed clinically. Of the 151 infants that had an US, 140 (93%) were read as normal. None had a dislocated hip. Two patients had a normal physical exam but laxity on US. These 2 patients were the only infants treated in a Pavlik harness. A pediatric orthopaedic surgeon followed those with subtle US findings and no laxity until normal.

Conclusions: The decision by the AAP to recommend US screening at 6 weeks of age for infants with a normal physical exam but breech position was based on an extensive literature review and expert opinion. Not all pediatricians are following the AAP guidelines. The decision to perform an US should be done on a case-by-case basis by the examining physician. A more practical, cost-effective strategy would be to skip the US if the physical exam is normal and simply obtain an AP pelvis x-ray at 4 months.

Level of evidence: Level III-this is a case-control study investigating the outcomes of infants on data drawn from the electronic medical record.

- Breech Presentation / surgery*

- Case-Control Studies

- Cesarean Section / methods

- Hip Dislocation, Congenital / diagnosis*

- Joint Instability / diagnosis*

- Physical Examination / methods

- Risk Assessment / methods

- Ultrasonography / methods*

Variation in fetal presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created The Radswiki had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Yuranga Weerakkody had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Delivery presentations

- Variation in delivary presentation

- Abnormal fetal presentations

There can be many variations in the fetal presentation which is determined by which part of the fetus is projecting towards the internal cervical os . This includes:

cephalic presentation : fetal head presenting towards the internal cervical os, considered normal and occurs in the vast majority of births (~97%); this can have many variations which include

left occipito-anterior (LOA)

left occipito-posterior (LOP)

left occipito-transverse (LOT)

right occipito-anterior (ROA)

right occipito-posterior (ROP)

right occipito-transverse (ROT)

straight occipito-anterior

straight occipito-posterior

breech presentation : fetal rump presenting towards the internal cervical os, this has three main types

frank breech presentation (50-70% of all breech presentation): hips flexed, knees extended (pike position)

complete breech presentation (5-10%): hips flexed, knees flexed (cannonball position)

footling presentation or incomplete (10-30%): one or both hips extended, foot presenting

other, e.g one leg flexed and one leg extended

shoulder presentation

cord presentation : umbilical cord presenting towards the internal cervical os

- 1. Fox AJ, Chapman MG. Longitudinal ultrasound assessment of fetal presentation: a review of 1010 consecutive cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46 (4): 341-4. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00603.x - Pubmed citation

- 2. Merz E, Bahlmann F. Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology. Thieme Medical Publishers. (2005) ISBN:1588901475. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Obstetric curriculum

- Cord presentation

- Polyhydramnios

- Footling presentation

- Normal obstetrics scan (third trimester singleton)

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Impact of point-of-care ultrasound and routine third trimester ultrasound on undiagnosed breech presentation and perinatal outcomes: An observational multicentre cohort study

Contributed equally to this work with: Samantha Knights, Smriti Prasad

Roles Data curation

Affiliation Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Norwich, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Fetal Medicine Unit, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Statistics, Middle East Technical University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Ankara, Turkey, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Koc University, School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

Roles Conceptualization

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Fetal Medicine Unit, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, Vascular Biology Research Centre, Molecular and Clinical Sciences Research Institute, St George’s University of London, London, United Kingdom, Fetal Medicine Unit, Liverpool Women’s Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- Samantha Knights,

- Smriti Prasad,

- Erkan Kalafat,

- Anahita Dadali,

- Pam Sizer,

- Francoise Harlow,

- Asma Khalil

- Published: April 6, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004192

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

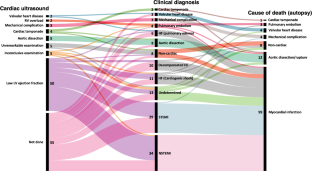

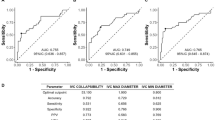

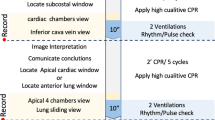

Accurate knowledge of fetal presentation at term is vital for optimal antenatal and intrapartum care. The primary objective was to compare the impact of routine third trimester ultrasound or point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) with standard antenatal care, on the incidence of overall and proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed at term, and on the related adverse perinatal outcomes.

Methods and findings

This was a retrospective multicentre cohort study where we included data from St. George’s (SGH) and Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals (NNUH). Pregnancies were grouped according to whether they received routine third trimester scan (SGH) or POCUS (NNUH). Women with multiple pregnancy, preterm birth prior to 37 weeks, congenital abnormality, and those undergoing planned cesarean section for breech presentation were excluded. Undiagnosed breech presentation was defined as follows: (a) women presenting in labour or with ruptured membranes at term subsequently discovered to have a breech presentation; and (b) women attending for induction of labour at term found to have a breech presentation before induction. The primary outcome was the proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed. The secondary outcomes included mode of birth, gestational age at birth, birth weight, incidence of emergency cesarean section, and the following neonatal adverse outcomes: Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes, unexpected neonatal unit (NNU) admission, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and perinatal mortality (including stillbirths and early neonatal deaths). We employed a Bayesian approach using informative priors from a previous similar study; updating their estimates (prior) with our own data (likelihood). The association of undiagnosed breech presentation at birth with adverse perinatal outcomes was analyzed with Bayesian log-binomial regression models. All analyses were conducted using R for Statistical Software (v.4.2.0).

Before and after the implementation of routine third trimester scan or POCUS, there were 16,777 and 7,351 births in SGH and 5,119 and 4,575 in NNUH, respectively. The rate of breech presentation in labour was consistent across all groups (3% to 4%). In the SGH cohort, the percentage of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed was 14.2% (82/578) before (years 2016 to 2020) and 2.8% (7/251) after (year 2020 to 2021) the implementation of universal screening ( p < 0.001). Similarly, in the NNUH cohort, the percentage of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed was 16.2% (27/167) before (year 2015) and 3.5% (5/142) after (year 2020 to 2021) the implementation of universal POCUS screening ( p < 0.001). Bayesian regression analysis with informative priors showed that the rate of undiagnosed breech was 71% lower after the implementation of universal ultrasound (RR, 0.29; 95% CrI 0.20, 0.38) with a posterior probability greater than 99.9%. Among the pregnancies with breech presentation, there was also a very high probability (>99.9%) of reduced rate of low Apgar score (<7) at 5 minutes by 77% (RR, 0.23; 95% CrI 0.14, 0.38). There was moderate to high probability (posterior probability: 89.5% and 85.1%, respectively) of a reduction of HIE (RR, 0.32; 95% CrI 0.0.05, 1.77) and extended perinatal mortality rates (RR, 0.21; 95% CrI 0.01, 3.00). Using informative priors, the proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed was 69% lower after the initiation of universal POCUS (RR, 0.31; 95% CrI 0.21, 0.45) with a posterior probability greater of 99.9%. There was also a very high probability (99.5%) of a reduced rate of low Apgar score (<7) at 5 minutes by 40% (RR, 0.60; 95% CrI 0.39, 0.88). We do not have reliable data on number of facility-based ultrasound scans via the standard antenatal referral pathway or external cephalic versions (ECVs) performed during the study period.

Conclusions

In our study, we observed that both a policy of routine facility-based third trimester ultrasound or POCUS are associated with a reduction in the proportion of term breech presentations that were undiagnosed, with an improvement in neonatal outcomes. The findings from our study support the policy of third trimester ultrasound scan for fetal presentation. Future studies should focus on exploring the cost-effectiveness of POCUS for fetal presentation.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Accurate knowledge of fetal presentation is essential for optimal care during pregnancy and birth. Vaginal breech delivery is associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.

- Abdominal palpation has poor sensitivity (50% to 70%) for determination of fetal presentation.

- The role of a routine third ultrasound assessment of fetal presentation has been reported but the impact on neonatal outcomes is yet to be determined.

- There are limited reports on antenatal use of handheld point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for the determination of fetal presentation, but the impact of their systematic use for this purpose is largely unknown.

What did the researchers do and find?

- We analysed 2 cohorts of pregnant women from 2 large teaching hospitals in the United Kingdom where a policy of routine third trimester ultrasound or POCUS has been implemented.

- We studied the impact of routine third trimester ultrasound or POCUS on the percentage of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed and adverse neonatal outcomes, in pre- and post-screening epochs.

- Due to the rarity of adverse outcomes, we employed Bayesian regression analysis with informative priors. This statistical tool permits updating previous findings with new data to generate new evidence.

- We found that the incidence of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed reduced drastically in the post-screening epoch following the implementation of either a third trimester ultrasound (decreased from 14.2% to 2.8%) or POCUS (decreased from 16.2% to 3.5%). There was an associated improvement in neonatal outcomes.

What do these findings mean?

- Our findings imply that a policy of either a third trimester ultrasound by sonographers or POCUS by trained midwives was effective in reducing the proportion of all term breech presentations at the time of birth that were undiagnosed and associated neonatal complications.

- Cost-effectiveness of POCUS needs to be explored further for feasibility of implementation on a wider scale for assessment of fetal presentation at term.

Citation: Knights S, Prasad S, Kalafat E, Dadali A, Sizer P, Harlow F, et al. (2023) Impact of point-of-care ultrasound and routine third trimester ultrasound on undiagnosed breech presentation and perinatal outcomes: An observational multicentre cohort study. PLoS Med 20(4): e1004192. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004192

Received: August 19, 2022; Accepted: February 7, 2023; Published: April 6, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Knights et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data cannot be shared publicly because consent was not obtained from women; permission for sharing data was not sought as part of ethical approval. Data is only available following approval from Research Ethics Committee and Confidentiality Advisory Group. Enquiries and requests should be made to the the Research Governance and Delivery team at St George's University of London ( [email protected] ).

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: AK is a Vice President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. AK is a Trustee (and the Treasurer) of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology AK has lectured at and consulted in several ultrasound-based projects, webinars and educational events.

Abbreviations: BAME, black, Asian, and minority ethnic; BMI, body mass index; CrI, credible intervals; ECV, external cephalic version; HIE, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; HRA, Health Research Authority; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; IMD, index of multiple deprivation; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; NNU, neonatal unit; NNUH, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital; NSC, National Screening Committee; POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound; RR, risk ratio; SGH, St. George’s Hospital

Introduction

The incidence of breech presentation at term is 3% to 4% [ 1 ]. Breech vaginal birth is associated with an increase in both perinatal mortality and morbidity as well as maternal morbidity [ 2 – 7 ]. Correct knowledge of fetal presentation at term is essential for providing optimum antepartum and intrapartum care. Women with breech presentation at term can be effectively counselled about their options—external cephalic version (ECV), planned vaginal birth, or elective cesarean birth—with their inherent risks and perceived benefits [ 1 ]. There is substantial evidence that clinical examination is not accurate enough for determination of fetal presentation, with unacceptably high rates of missed breech/noncephalic presentations at term [ 8 , 9 ].

There are 2 modalities to screen for fetal presentation at term, each with its advantages and disadvantages: routine third trimester ultrasound or point-of-care/portable ultrasound (POCUS). Currently, routine third trimester ultrasound is not recommended by the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in low-risk pregnancies due to insufficient clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence [ 10 , 11 ]. In the UK, the current practice is to perform an early pregnancy risk assessment followed by referral pathways for low-risk and high-risk women. These risks relate to maternal, fetal, and placental pathology but are unrelated to the risk of breech presentation at term. Women deemed to be at high risk are referred for an ultrasound scan at 28 weeks’ gestation for fetal biometry with or without additional follow-up ultrasound scans. Low-risk women are followed up with clinical assessment (serial measurement of symphysio-fundal height) and referred for third trimester ultrasound if fetal growth restriction is suspected or if it is difficult to perform clinical examination, as in women with high body mass index (BMI), multiple pregnancy, or multiple uterine fibroids, or there is clinical suspicion of noncephalic fetal presentation at term [ 12 – 14 ]. Emerging data from observational studies and a systematic review indicate that it is feasible to accurately diagnose fetal presentation at term by third trimester ultrasound, thereby reducing the proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed at the time of labour and birth [ 15 – 18 ]. The clinical end point of any study of the diagnosis of breech presentation at term would be an improvement in neonatal outcomes, associated with reduction in incidence of undiagnosed breech. Hitherto published literature, however, could not demonstrate a translation of increased antenatal diagnosis of breech presentation into a statistically significant improvement in neonatal outcomes, most likely owing to the rarity of adverse outcomes.

Most of the data on the use of POCUS in antenatal settings are from low-resource settings where there is inadequate access to ultrasound owing to both material and physical constraints; hence, the focus is on task-shifting of obstetric ultrasound from sonographers to primary care providers [ 19 , 20 ]. A recently published review reported improved diagnostic accuracy with POCUS compared to clinical examination only, for high-risk obstetric conditions including fetal malpresentation, albeit studies were heterogeneous and referred to varying standards [ 21 ]. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada identifies POCUS as a useful modality for timely determination of fetal presentation [ 22 ]. A retrospective criterion-based audit performed in one of our study hospitals demonstrated that the use of POCUS by midwives in the antenatal ward/labour ward was associated with identification of previously unrecognized breech presentation, thereby preventing inappropriate induction of labour [ 23 ]. A recent validation study of POCUS in obstetric care showed near perfect agreement for assessment of fetal presentation [95.6% agreement, Kappa −0.887, 95% CI (0.78 to 0.99)] when compared to routine ultrasound [ 24 ]. There is, however, scanty literature on the diagnostic accuracy of POCUS in antenatal care settings for assessment of fetal presentation, compared to standard antenatal care, i.e., routine abdominal palpation, with referral for ultrasound when there is clinical suspicion of breech presentation.

In our study, we aimed to compare the impact of routine third trimester ultrasound or POCUS with standard antenatal care, on the incidence of overall and proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed at term, and on the related adverse perinatal outcomes.

The study included data from St. George’s University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (SGH) and Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (NNUH). For both centres, pregnancies were grouped according to whether they received routine third trimester scan (SGH) or POCUS (NNUH).

Routine third trimester scan cohort

We included a cohort of pregnant women who gave birth between 4 April 2016 and 30 September 2021, at SGH, a large teaching hospital in South West London. The chosen starting point was the date when birth records were first systematically entered into the current electronic database. At SGH, a policy of routine third trimester (at 36 weeks) ultrasound scan by sonographers for all pregnant women has been implemented since January 2020; this includes assessment of fetal biometry, umbilical and middle cerebral artery Doppler, placental localization, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal presentation. Following a diagnosis of breech presentation during the ultrasound scan, women are counselled about their options: ECV, planned cesarean birth, or planned vaginal birth. If women declined ECV or if it was unsuccessful, they were offered elective cesarean delivery from 39 weeks of gestation. The population was divided into 2 study groups: Group 1 (women who were offered and accepted a routine third trimester scan) and Group 2 (women who received standard antenatal care in line with national guidance, without a routine third trimester scan).

POCUS cohort

The POCUS cohort included pregnant women from NNUH where a policy of routine POCUS at the 36-week antenatal visit was fully adopted from November 2020 following stage-wise implementation in 2016. The POCUS is performed by a midwife using Vscan Air (GE Healthcare). NNUH is a large teaching hospital with approximately 6,000 births per year, and approximately 250 midwives working across the hospital and community. We included 2 groups: a historical cohort of women who received routine care—abdominal palpation and referral for selective ultrasound on clinical suspicion of breech presentation (2015) and those who had POCUS at the 36- to 37-week visit (November 2020 to 2021). Through 2016 to November 2020, POCUS was variably used, either on the labour ward or via referral from community midwives, on clinical suspicion of noncephalic presentation, and these women were not included in this study.

Training of midwives for POCUS cohort

The midwives in NNUH underwent a structured 3-month training programme. The workshops consisted of daily handheld scanning sessions with an hour of dedicated lectures. The theoretical lectures were followed by practice on consenting women in the antenatal ward. All the trainee midwives maintained a competency logbook, detailing both successful and unsuccessful cases. Following the initial workshops, “midwife champions” were identified who were deemed competent or held other ultrasound qualifications and were suitable for cascade training. POCUS training was a part of preceptor ship training of newly qualified midwives, while midwives working in nonpermanent roles were supported and advised to work with one of the champions.

The primary outcome was the proportion of all term breech presentations that were undiagnosed. Undiagnosed breech presentation was defined as follows: (a) breech presentation after the onset of labour or rupture of membranes at term; and (b) breech presentation diagnosed immediately before commencing induction of labour. The secondary outcomes included mode of birth, gestational age at birth, birth weight, incidence of emergency cesarean section, and the following neonatal adverse outcomes: Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes, unexpected neonatal unit (NNU) admission, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) 1 to 3, and perinatal mortality (includes stillbirths and early neonatal deaths).

Women with multiple pregnancies, preterm birth <37 weeks, and congenital abnormalities were excluded. Pregnancies undergoing planned cesarean section for breech presentation were excluded from the analysis of the study outcomes, except for the neonatal outcomes. Maternal demographic characteristics, antenatal, intrapartum, and perinatal data were extracted from Euroking E3 maternity information system and Viewpoint database (ViewPoint 5.6.8.428, ViewPoint Bildverarbeitung GmbH, Weßling, Germany). Routinely collected clinical data were collated from electronic health records and were deemed not to require ethics approval or signed patient consent as per the Health Research Authority (HRA) decision tool.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive variables were compared with Wilcoxon-signed rank test, t test, or chi-squared test, where appropriate. An adequately powered analysis is not practically feasible due to rarity of adverse outcomes following breech delivery. Therefore, we employed a Bayesian approach using informative priors from a previous similar study; updating their estimates (prior) with our own data (likelihood) [ 18 ]. The association of undiagnosed breech presentation at birth with adverse perinatal outcomes was analyzed with Bayesian log-binomial regression models and reported as RR (risk ratios) with credible intervals (CrI). Informative priors ( N ~ μ, σ ) for population mean were derived from Salim and colleagues and a weakly informative prior (Student t , df = 3) for model intercept. Prior parameters were estimated by using the log-risk ratios and log-confidence intervals from Salim and colleagues, and in case an effect could not be estimated in the original study due to a no-event situation, we added a single event to the corresponding group and reestimated the risk ratios. Two Markov chains were run for 1,500 iterations after an initial 500 burn-in period. Posterior probabilities were calculated using the probability density function of normal distribution. A sensitivity analysis using flat priors (noninformative) was also undertaken to investigate the weight of informative prior on the posterior density. Number needed to treat for important outcomes was calculated using current population numbers without incorporating external data. Convergence was checked with trace plots. All analyses were conducted using R for Statistical Software (v.4.2.0) using “brms” and “its.analysis” packages [ 25 , 26 ]. This study is reported as per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline ( S1 STROBE Checklist).

Study cohorts

In the SGH cohort, there were 24,128 singleton pregnancies during the eligibility period, of which 16,777 births were before the introduction of universal third trimester ultrasound scan and 7,351 after. Baseline characteristics of included pregnancies are presented in Table 1 . Women who gave birth before universal ultrasound scan were significantly younger (33.2 versus 35.7 years, p < 0.001), had similar BMI (25.6 versus 25.7 kg/m 2 , p = 0.194) and multiparity rate (49.6% [8,316/16,777] versus 49.2% [3,617/7,351], p = 0.612) compared to those who gave birth after. There was a slight drop in the proportion of births that were in women from black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) background (39.3% [6,588/16,777] versus 37.9% [2,785/7,351], p = 0.044). The index of multiple deprivation (IMD) quintiles were similar between the 2 epochs ( p > 0.05 for all quintiles; Table 1 ), as was the total number of breech presentations at the time of birth (3.4% [578/16,777] versus 3.4% [251/7,351], p = 0.953), including all diagnosed and undiagnosed cases. A comparison of the baseline characteristics, as well as the gestational age at delivery in weeks and mode of birth of pregnancies with breech presentation at birth in the study epochs before and after the introduction of universal 36-week ultrasound scan is shown in Table 2 . Pregnancies with breech presentation at term were significantly more likely to be delivered by elective cesarean section (76.9% [193/251] versus 60.7% [351/278], p < 0.001) after compared to before the implementation of the universal 36-week ultrasound scan. Emergency cesarean section was lower (17.1% [43/251] versus 30.8% [178/578], p < 0.001) after compared to before the implementation of the universal 36-week ultrasound scan. A similar trend was noted for vaginal breech delivery ( Table 2 ). The gestational age at birth was 39.1 weeks in both groups with a mean difference of 1 day. Although the difference was statistically significant, it would be deemed clinically inconsequential.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004192.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004192.t002