Research Project A & B (Stage 2)

Length of course, compulsory or elective, pre-requisites, subject description.

Students choose a research question that is based on an area of interest to them. They explore and develop one or more capabilities in the context of their research.

The term ‘research’ is used broadly and may include practical or technical investigations, formal research, or exploratory inquiries.

The Research Project provides a valuable opportunity for SACE students to develop and demonstrate skills essential for learning and living in a changing world. It enables students to develop vital skills of planning, research, synthesis, evaluation, and project management.

The Research Project enables students to explore an area of interest in depth, while developing skills to prepare them for further education, training, and work. Students develop their ability to question sources of information, make effective decisions, evaluate their own progress, be innovative, and solve problems.

The content of both Research Project A and B consists of:

- developing the capabilities

- applying the research framework

In Research Project students choose a research question that is based on an area of interest . They identify one or more capabilities that are relevant to their research.

Students use the research framework as a guide to developing their research and applying knowledge, skills, and ideas specific to their research question. They choose one or more capabilities, explore the concept of the capability or capabilities, and how it or they can be developed in the context of their research.

Students synthesise their key findings to produce a Research Outcome, which is substantiated by evidence and examples from the research. They review the knowledge and skills they have developed, and reflect on the quality of their Research Outcome.

Students must achieve a C– grade or better to complete the subject successfully and gain their SACE.

For Research Project A, students can choose to present their external assessment in written, oral, or multimodal form.

For Research Project B, the external assessment must be written.

The following assessment types enable students to demonstrate their learning in Stage 2 Research Project A and B:

School Assessment (70%)

Assessment Type 1: Folio (30%)

Assessment Type 2: Research Outcome (40%)

External Assessment (30%)

Assessment Type 3: Review (30% Research Project A)

Assessment Type 3: Evaluation (30% Research Project B)

Research Project A and B contribute to an ATAR

Pathways for Cross Disciplinary

Click a subject to view its pathway

Subject added

THS Curriculum Handbook

Year 11 – Research Project

Length: Single Semester (10 Stage 2 credits) Contact: SACE Leader ALL students must complete the 10-credit Research Project at Stage 2 of the SACE, with a C− grade or better. Course Description Students will:

- Choose a topic of interest and develop a research question

- Learn and apply research processes and the knowledge and skills specific to their research topic

- Record their research and evaluate what they have learnt.

The term research is used broadly and may include practical or technical investigations, formal research, or exploratory enquiries. Students are expected to:

- Work independently and with others to initiate an idea, and to plan and manage a research project

- Demonstrate the learning capability and 1 other chosen capability

- Analyse information and explore ideas to develop their research

- Develop and apply specific knowledge and skills

- Communicate and evaluate their research outcome

- Evaluate the research processes used and their chosen capability.

Assessment (Both ATAR accredited) Research Project A

- Folio (30%)

- Research Outcome (40%)

- Review (external assessment – 30%).

Maximum of 1500 words if written. Maximum of 10 minutes for an oral presentation. Equivalent in multimodal form. Research Project B

- Evaluation (30%).

A maximum of 2000 words if written or a maximum of 12 minutes for an oral presentation, or the equivalent in multimodal form. Note: We strongly advise that Research Project B be undertaken for those students on a University pathway.

Enterprising Research and the SACE Research Project

Topic outline, 2.2 what makes a good sace research project question.

While we now know a bit more about the research questions that researchers at UniSA are working with, it’s important to contextualise your own research questions within the Research Project itself. University-level research and Research Projects are of course very different, and the sorts of questions you ask reflect that.

While our researchers at UniSA have whole labs, teams, and sometimes years at their disposal, you only have a short amount of time to complete your projects. This means your questions should look a little different.

So, what should Research Project questions look like?

You shouldn’t be able to answer it with a Google search, or by asking one expert what they think. It should require research using multiple sources, both primary and secondary.

You should be looking for a gap, a question that someone else hasn’t asked yet. A good rule of thumb is to think local. How does this question impact someone like you? Or year 12 students? Or people in Adelaide? These are often questions often in need of an answer, and questions that will require a suitable amount of effort on your part.

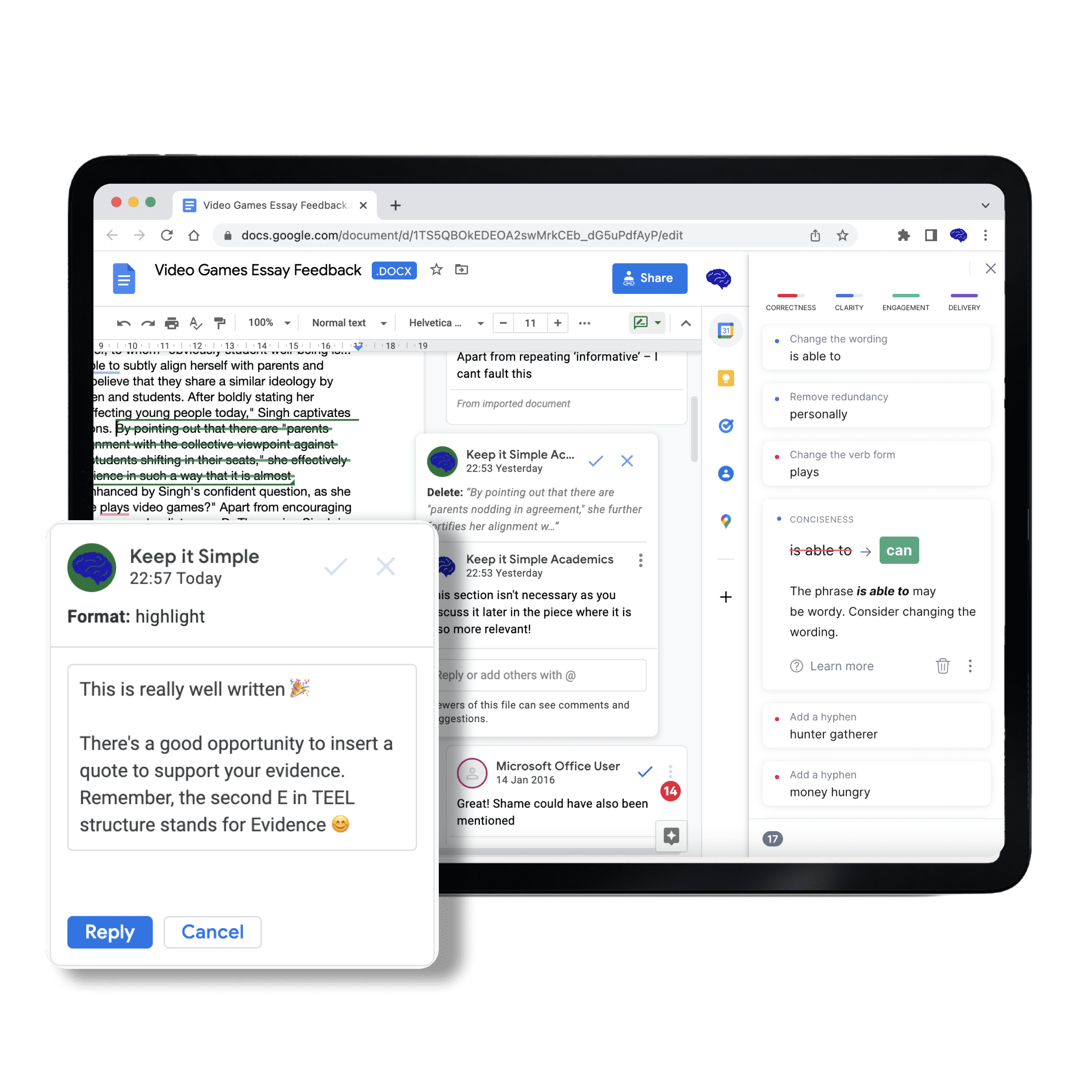

KIS Academics

We'll mark your

Sace research project, assignment feedback starting at $30.

Our expert tutors can help you ace your

Last minute cram? Get your

back as quickly as you need it

Get your assignment back on time, or we'll give you a full refund and send it to you anyway

.png)

It's as easy as 1, 2, 3 🎶

Here's why kis academics is your #1 choice:.

Marked by the top 3% of tutors in Australia

Year 7-12 Science Practicals

Assignment marking starts at $30

Science Poster Presentations and EPIs

Year 5-10 English Essays

Research Projects (SACE)

Year 11-12 ATAR English Essays

Maths Investigations

SACE SHE tasks. Learn how to ace it here .

...and more!

Getting an expert to look over your

Won't just boost your mark... it'll make sure you actually learn and improve with the help of useful feedback, how does the sace research project work 🔬, so what is the research project.

Unlike your other SACE stage 2 subjects being 20 credits, the research project is a 10-credit SACE subject you will either complete in year 11 or 12 depending on which high school you attend. The subject consists of three parts: the folio, outcome, and review for research project A or the evaluation if you are undertaking research project B.

Despite research projects A and B having different performance standards, both encourage you to explore a topic of choice in depth, gathering various sources and writing reflections on your learning. In the first few weeks of the subject, your teacher will guide you when developing your question.

The folio is 10 pages in length and typically consists of your reflections and the main sources you have collected through your research (both primary and secondary sources!). You will then write an outcome that is essentially answering your original research question. Lastly, comes the evaluation or review where you will write an overall reflection and evaluate the findings in the outcome.

How do I develop the best question for my topic of interest?

The most important part of the research is picking the right topic.

You want to pick something you have a strong interest in. This way, it will be much easier for you to feel more motivated to sit down and do your research. However, at the same time, you want to pick a topic that will have lots of research behind it, you don't want to be stuck for sources!

To avoid this, write down a list of topics you have an interest in and do some research on each - see what is available online or at a local library. This way, you will be more prepared when your teacher comes over to your desk to ask you what you have done so far!

Once you have picked your topic, create another list of possible questions you could investigate. These questions should be open-ended, not just with a simple yes or no answer. Keep in mind you will be writing a 1500 to 2000-word answer to this question, so make it a question you can go into complete depth with. Typical questions should be specific and may begin with ‘to what extent’, ‘evaluate’, ‘what’ or ‘how’. For example, if you picked social media as your topic, your question could be ‘to what extent does social media use impact the attention spans of teenagers aged 13-17?’ rather than ‘does social media impact attention spans?’.

You may then have to break down your main question into four more guiding questions to help you structure your folio and outcome. For example, ‘how much time do teenagers aged 13-17 spend on social media every day?’. It is important that you keep documentation of this process as you will be displaying it in your folio.

Want an expert tutor to read over your Research Project before handing it in? You've come to the right place.

Send it through to us now and we'll return your Research Project to you with detailed marking and feedback. We'll even compare it to any criteria or rubric you've been given to make sure it aligns with your marking standards 🔥

Trusted Tutors by families all over Australia 🇦🇺

Real results and verified reviews, why you should get your, marked by kis academics:, review before submitting, maximise your marks.

If you really want to achieve the highest grades for your assignments, submit them to be marked by KIS Academics' expert tutors before handing them in. Having someone look over your work and provide feedback is one of the best ways to pre-screen assignments before submission and get the best advantage. As soon as you send your assignment to us, our tutors will review and return it to you with thorough and useful recommendations to improve not just this assignment, but your academic skills overall. All assignment reviewing is done in accordance with our Academic Integrity Policy

get expert advice

Don't just hand assignments in... learn from them.

Assignments aren't just a way to test your knowledge. You should be able to learn from them too. Receive valuable feedback on: 👉 Spelling, grammar and punctuation 👉 Sentence and essay structure 👉 Themes, quotes and analysis 👉 Scientific and Mathematical Accuracy 👉 Sticking to curriculum and rubric requirements 👉 And more...

Let's ace your

Our academic integrity policy: provide help, not answers 🎓.

KIS Academics is committed to maintaining the highest levels of academic integrity by creating, using, and sharing information in a manner that is responsible , honourable , and, at all times, ethical .

KIS Academics considers the upholding of academic integrity to be the responsibility of all employees within the company, as well as all private tutors.

KIS Academics takes an educative - not punitive - approach to ensure students and private tutors are provided with the support needed to effectively address any academic integrity issues that may be identified.

KIS Academics mandates our tutors to maintain the highest levels of academic integrity in all their interactions with their students.

Australia’s Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) defines academic integrity as ‘a commitment ... to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage’ (International Centre for Academic Integrity, 2014 AS CITED IN TEQSA).

These fundamental values are the basis on which principles and behaviours within the scope of academic integrity are developed. For the purpose of this policy, academic integrity is the moral and ethical code of conduct related to the use, generation and communication of information in an honourable, fair, and responsible manner.

Submitting your assignment to be reviewed by a KIS Academics tutor will ensure you not only receive top-notch feedback and guidance on how to improve your academic skills, but you do so in a way that is ethical, legal and maintains academic integrity

Assignment and essay marking

Frequently asked questions 🙋, what is the marking service.

How much does it cost?

How does it work, who will mark my assignment, is it confidential, what if it's not sent back in time.

.png)

That's why we set out to hire only the best tutors in Australia .

We have hundreds of amazing, qualified online tutors offering top quality services, starting at just $40 per hour. Whether the student is in high school or primary school, we cater for all. So, why are our tutors so amazing compared to other companies? It's simple, we pay them better. We take a low commission so you can get top scoring private tutors at the best rates. Discover our team of dedicated tutors who specialize in various subjects, from Chemistry and Maths to English and UCAT , as well as offering support for high school, HSC , and VCE , and many more. View all tutoring locations .

Paying for an initial lesson with a tutor you've never met is absolutely crazy! And surprisingly, that's what most tutoring places will ask you to do. We think you deserve to meet your tutor and make sure they're the right fit for you - free of charge. Request a tutor and they will reach out to you to organise this free trial session!

Skeptical about online courses ? Trust us, you won't be for long. With tutors specifically trained to deliver content online and use the latest and greatest teaching tools, we'll make you wish you had done things with KIS from the start. You can watch, rewatch, revise and review content as often as you need to. Starting at only $8 per week.

It's hard to express just how much we care that you have a great experience with us. We invite you to look us up on Facebook, TrustPilot, Instagram and Google. There's plenty of amazing stories from our previous customers. Click below to see all our reviews on posted on our Wall of Love ❤️

- VCE Chemistry tutors Melbourne

- VCE English tutors Melbourne

- VCE Methods tutors Melbourne

- Year 5-12 Maths tutors Melbourne

- Year 5-12 English tutors Melbourne

- HSC Chemistry tutors Sydney

- HSC English tutors Sydney

- HSC Physics tutors Sydney

- Year 5-12 Maths tutors Sydney

- Year 5-12 English tutors Sydney

- ATAR Chemistry tutors Brisbane

- ATAR English tutors Brisbane

- ATAR Methods tutors Brisbane

- Year 5-12 Maths tutors Brisbane

- Year 5-12 English tutors Brisbane

- WACE Chemistry tutors Perth

- WACE English tutors Perth

- WACE Maths Methods tutors Perth

- Year 5-12 Maths tutors Perth

- Year 5-12 English tutors Perth

- Medical Entry

- Study Skills

- Private Tutoring

- Bring a Friend and Save

- Online Courses

- Assignment and Essay Marking

- How Private Tutoring Works

- How The ATAR Works

- Atar Calculator

- Free Events

- Tutoring Reviews ❤️

- Help Centre

- Become a Tutor

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Jobs at KIS Academics 🚀

- Chemistry Tutors in Adelaide

- English Tutors in Adelaide

- Maths Tutors in Adelaide

- Mathematical Methods Tutors in Adelaide

- Chemistry Tutors in Perth

- English Tutors in Perth

- Maths Tutors in Perth

- Mathematical Methods Tutors in Perth

- Chemistry Tutors in Brisbane

- English Tutors in Brisbane

- Maths Tutors in Brisbane

- Mathematical Methods Tutors in Brisbane

- Chemistry Tutors in Melbourne

- English Tutors in Melbourne

- Maths Tutors in Melbourne

- Mathematical Methods Tutors in Melbourne

.png)

- How it Works

- Find a Tutor

- Read Today's Paper

Controversial SACE research project to stay in curriculum despite criticism

STUDENTS must continue to study the controversial research project despite many submissions asking for it to be dumped, Education Minister Grace Portolesi says.

STUDENTS must continue to study the controversial research project despite many submissions to a review asking for it to be dumped, made optional or strictly a Year 11 subject, Education Minister Grace Portolesi says.

Responding to the SACE first year evaluation, the State Government says it will now encourage students to study five full subjects in Year 12.

But it is not willing to enforce the move, instead leaving it up to the state's universities to boost entry requirements.

Ms Portolesi yesterday said the Government would also provide more support for teaching and marking, more practical research project options and an optional preparatory research skills subject in Year 11.

There will be no changes for students introduced next year. Revised research project options and the research skills subject will be introduced in 2014.

"We are strengthening the research project and we are backing the SACE," Ms Portolesi said.

She revealed plans to provide students with an incentive to study a fifth Year 12 subject and had written to each of SA's three universities asking them to consider calculating the university entry score using a 90-point system rather than the current 80 points.

Under the current system, the score is based on students' results in four subjects because each subject is worth 20 points. Moving to a 90-point system would allow the fifth subject to also be counted.

"The decision to have a 90-point aggregate is up to universities and I am asking them to consider this in time for students studying for their SACE in 2015," Ms Portolesi said.

"This means students could study five full-year subjects in their final year and have each of them count towards their ATAR (university entrance score).

An Institute of Educational Assessors would also be established to assist teachers and the SACE Board would receive an extra $7.6 million investment over the next five years.

The independent evaluation of the first year of the new SACE found the research project provides an "inherent advantage" for female students and recommended an easier version be available to Year 11 students who wanted to do five subjects in Year 12.

The government did not support this recommendation and instead would continue to allow schools to offer the research project designed for Year 12s in Year 11.

Each of SA's three universities said they were willing to look at Ms Portolesi's request to change the entry requirements.

Australian Education Union SA branch president Correna Haythorpe said teachers wanted to see more flexibility and thought the research project should not be compulsory.

"I believe members would continue to hold the view that students should be able to decide whether to engage in the research project or not," she said.

Association of Independent Schools of SA chief executive Garry Le Duff said there were very diverse views about the SACE among private schools but some leaders were critical of the research project.

"Our submission to the review wanted students who want to study five subjects be given recognition so the government's response has gone some way to meeting that request," he said.

"(It) is a step in the right direction and we will continue to monitor the SACE and its development."

St Peter's Girls principal Fiona Godfrey said she applauded the consideration given to all the major issues but was concerned the changes did not go far enough.

"In terms of the research project I still firmly believe it shouldn't be a compulsory element of Stage 2 (Year 12) and should be a Stage 1 (Year 11) subject or an elective in Stage 2," she said.

"Changes to university entrance doesn't force students to study five subjects and most will just continue to study four subjects and the compulsory research project.

"The real issues not addressed at all are the falling number of students studying languages other than English and humanities."

SA Secondary Principals Association president Jan Paterson said she welcomed the decision because it would enhance schools' capacity to deliver a high school certificate that was valuable to all students.

Opposition Leader Isobel Redmond said the new SACE was a "failed experiment".

"I understand some people were doing planning their wedding or building a dog kennel and all sorts of things (for the Research Project). Those things should be extra curricular, not part of a serious qualification," she said.

"Having only four subjects was not good. I believe that we need to have a bigger focus on English as a language being taught. I don't believe that we do that well enough."

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

- STUDY PROGRAMS

- OVERSEAS STUDY CONSULTING

- SCHOLARSHIPS

Australian courses

Research project.

I. INTRODUCTION

Stage 2 Research Project is a compulsory 10-credit subject. Students must achieve a C–grade or better to complete the subject successfully and gain their SACE.

Students enrol in either Research Project A or Research Project B.

The external assessment for Research Project B must be written. Students can choose to present their external assessment for Research Project A in written, oral, or multimodal form.

Research Project B may contribute to a student’s Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR).

Students choose a research question that is based on an area of interest to them. They explore and develop one or more capabilities in the context of their research.

The term ‘research’ is used broadly and may include practical or technical investigations, formal research, or exploratory inquiries.

The Research Project provides a valuable opportunity for SACE students to develop and demonstrate skills essential for learning and living in a changing world. It enables students to develop vital skills of planning, research, synthesis, evaluation, and project management.

The Research Project enables students to explore an area of interest in depth, while developing skills to prepare them for further education, training, and work. Students develop their ability to question sources of information, make effective decisions, evaluate their own progress, be innovative, and solve problems.

II. LEARNING SCOPE AND REQUIREMENTS

1. Learning Requirements

The learning requirements summarise the knowledge, skills, and understanding that students are expected to develop and demonstrate through their learning in Stage 2 Research Project B.

In this subject, students are expected to:

- generate ideas to plan and develop a research project

- understand and develop one or more capabilities in the context of their research

- analyse information and explore ideas to develop their research

- develop specific knowledge and skills

- produce and substantiate a Research Outcome

- evaluate their research.

Stage 2 Research Project B is a 10-credit subject.

The content of Research Project B consists of:

- developing the capabilities

- applying the research framework.

In Research Project B students choose a research question that is based on an area of interest. They identify one or more capabilities that are relevant to their research.

Students use the research framework as a guide to developing their research and applying knowledge, skills, and ideas specific to their research question. They choose one or more capabilities, explore the concept of the capability or capabilities, and how it or they can be developed in the context of their research.

Students synthesise their key findings to produce a Research Outcome, which is substantiated by evidence and examples from the research. They evaluate the research processes used, and the quality of their Research Outcome.

2.1. Developing the Capabilities

The purpose of the capabilities is to develop in students the knowledge, skills, and understanding to be successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens.

The capabilities that have been identified are:

- information and communication technology capability

- critical and creative thinking

- personal and social capability

- ethical understanding

- intercultural understanding.

The capabilities enable students to make connections in their learning within and across subjects in a wide range of contexts.

2.1.1. Literacy

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for literacy by, for example:

- communicating with a range of people in a variety of contexts

- asking questions, expressing opinions, and taking different perspectives into account

- using language with increasing awareness, clarity, accuracy, and suitability for a range of audiences, contexts, and purposes

- accessing, analysing, and selecting appropriate primary and secondary sources

- engaging with, and reflecting on, the ways in which texts are created for specific purposes and audiences

- composing a range of texts — written, oral, visual, and multimodal

- reading, viewing, writing, listening, and speaking, using a range of technologies

- developing an understanding that different text types (e.g. website, speech, newspaper article, film, painting, data set, report, set of instructions, or interview) have their own distinctive stylistic features

- acquiring an understanding of the relationships between literacy, language, and culture.

2.1.2. Numeracy

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for numeracy by, for example:

- using appropriate language and representations (e.g. symbols, tables, and graphs) to communicate ideas to a range of audiences

- analysing information displayed in a variety of representations and translating information from one representation to another

- justifying the validity of the findings, using everyday language, when appropriate

- applying skills in estimating and calculating, using thinking, written, and digital strategies to solve and model everyday problems

- interpreting information given in numerical form in diagrams, maps, graphs, and tables

- visualising, identifying, and sorting shapes and objects in the environment

- interpreting patterns and relationships when solving problems

- recognising spatial and geographical features and relationships

- recognising and incorporating statistical information that requires an understanding of the diverse ways in which data are gathered, recorded, and presented.

2.1.3. Information and Communication Technology Capability

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for information and communication technology by, for example:

- understanding how contemporary information and communication technologies affect communication

- critically analysing the limitations and impacts of current technologies

- considering the implications of potential technologies

- communicating and sharing ideas and information, to collaboratively construct knowledge and digital solutions

- defining and planning information searches of a range of primary and secondary sources when investigating research questions

- developing an understanding of hardware and software components, and operations of appropriate systems, including their functions, processes, and devices

- applying knowledge and skills of information and communication technology to a range of methods to collect and process data, and transmit and produce information

- learning to manage and manipulate electronic sources of data, databases, and software applications

- applying technologies to design and manage projects.

2.1.4. Critical and Creative Thinking

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for critical and creative thinking by, for example:

- thinking critically, logically, ethically, and reflectively

- learning and applying new knowledge and skills

- accessing, organising, using, and evaluating information

- posing questions, and identifying and clarifying information and ideas

- developing knowledge and understanding of a range of research processes

- understanding the nature of innovation

- recognising how knowledge changes over time and is influenced by people

- exploring and experiencing creative processes and practices

- designing features that are fit for function (e.g. physical, virtual, or textual)

- investigating the place of creativity in learning, the workplace, and community life

- examining the nature of entrepreneurial enterprise

- reflecting on, adjusting and explaining their thinking, and identifying the reasons for choices, strategies, and actions taken.

2.1.5. Personal and Social Capability

In Research Project B, students develop their personal and social capability by, for example:

- developing a sense of personal identity

- reviewing and planning personal goals

- developing an understanding of, and exercising, individual and shared obligations and rights

- participating actively and responsibly in learning, work, and community life

- establishing and managing relationships in personal and community life, work, and learning

- developing empathy for and understanding of others

- making responsible decisions based on evidence

- working effectively in teams and handling challenging situations constructively

- building links with others, locally, nationally, and/or globally.

2.1.6. Ethical Understanding

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for ethical understanding by, for example:

- identifying and discussing ethical concepts and issues

- considering ethical and safe research processes, including respecting the rights and work of others, acknowledging sources, and observing protocols when approaching people and organisations

- appreciating the ethical and legal dimensions of research and information

- reflecting on ethics and honesty in personal experiences and decision-making

- exploring ideas, rights, obligations, and ethical principles

- considering workplace safety principles, practices, and procedures

- developing ethical sustainable practices in the workplace and the community

- inquiring into ethical issues, selecting and justifying an ethical position, and understanding the experiences, motivations, and viewpoints of others

- debating ethical dilemmas and applying ethical principles in a range of situations.

2.1.7. Intercultural Understanding

In Research Project B, students develop their capability for intercultural understanding by, for example:

- identifying, observing, analysing, and describing characteristics of their own cultural identities and those of others (e.g. group memberships, traditions, values, religious beliefs, and ways of thinking)

- recognising that culture is dynamic and complex and that there is variability within all cultural, linguistic, and religious groups

- learning about and engaging with diverse cultures in ways that recognise commonalities and differences, create connections with others, and cultivate mutual respect

- developing skills to relate to and move between cultures

- acknowledging the social, cultural, linguistic and religious diversity of a nation, including that of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies in Australia

- recognising the challenges of living in a culturally diverse society and of negotiating, interpreting, and mediating difference.

2.2. Applying the Research Framework

The four parts of the research framework for Research Project B are:

- initiating and planning the research

- developing the research

- producing and substantiating the Research Outcome

- evaluating the research.

The four parts of the research framework are explained below.

2.2.1. Students Initiate and Plan their Research

Students plan their research by making decisions, seeking help, responding to and creating opportunities, and solving problems.

Students Formulate and Refine a Research Question

Formulating and refining the question help students to focus their research.

A research question:

- could be based on an idea or issue, a technical or practical challenge, a hypothesis, creating an artefact, or solving a problem

- may be an area of interest that is not related to a subject or course

- may be linked to content in an existing subject or course. Work that has been previously assessed for another subject or course cannot be used in this subject. However, information gained or ideas expressed in one assessment task can be extended in another assessment task.

Students refine their question, ensuring that the question lends itself to being researched and that the research is likely to be manageable and achievable. Refining a question may involve identifying a precise context, for example, place, type, age group, or time period.

Students and teachers must ensure that the research question and processes proposed do not compromise the principles of honest, safe, and ethical research.

Students Plan their Research

- consider, select, and/or design research processes (e.g. qualitative and quantitative research, practical experimentation, fieldwork) that are appropriate to their research question

- investigate and propose safe and ethical research processes

- identify knowledge, skills, and ideas that are specific to their research question

- identify people with whom to work (e.g. their teacher, a community expert, or a peer group) and negotiate processes for working together

- plan the research in manageable parts

- explore ideas in an area of interest

- explore the concept of a capability or capabilities in the context of their research

- consider the form of and audience for the Research Outcome.

2.2.2. Students Develop their Research

- develop a capability or capabilities in ways that are relevant to their research question

- develop and apply specific knowledge and skills

- develop and explore ideas

- locate, select, organise, analyse, use, and acknowledge information from different sources

- consult teachers and others with expertise in their area of interest

- participate in discussions with the teacher about the progress of their research

- apply safe and ethical research processes

- review and adjust the direction of their research in response to feedback, opportunities, questions, and problems as they arise

- maintain a record of progress made and sources used.

2.2.3. Students Produce and Substantiate their Research Outcome

Students synthesise their key findings (knowledge, skills, and ideas) to produce a Research Outcome.

The Research Outcome is substantiated by evidence and examples from the research, and shows how the student resolved the research question.

Substantiation should be relevant to the Research Outcome, and is usually provided in one or both of the following ways:

- By referencing the key findings from the research to sources, using, for example, in‑text references and thereby demonstrating the origin of ideas and thoughts.

- By explaining the validity of the methodology adopted and thereby demonstrating that it is able to be reproduced.

The Research Outcome must include the key findings and substantiation. The Research Outcome can take the form of:

- the key findings and substantiation, which together form a product

Examples include: an essay, a report, an oral or written history with appropriate in-text referencing and a bibliography and/or references list; a multimedia presentation; a documented science experiment

- the key findings and substantiation, with elements of or reference to a separate product

Examples include: a supporting statement and annotated photographs of a product that has been created; an extract from a student-developed children’s story, with a record of the background research

- the key findings presented as annotations on a product, and substantiated by evidence and examples of the research

Examples include: a recorded dance performance with notes and a director’s statement.

Students negotiate with their teacher suitable forms for producing their Research Outcome.

2.2.4 Students Evaluate their Research

- explain the choice of research processes used (e.g. qualitative and quantitative research, practical experimentation, fieldwork) and evaluate the usefulness of the research processes specific to the research question

- evaluate decisions made in response to challenges and/or opportunities (e.g. major activities, insights, turning points, and problems encountered)

- evaluate the quality of the Research Outcome

- organise their information coherently and communicate ideas accurately and appropriately

- communicate in written form.

III. ASSESSMENT SCOPE AND REQUIREMENTS

All Stage 2 subjects have a school assessment component and an external assessment component.

1. Evidence of Learning

The following assessment types enable students to demonstrate their learning in Stage 2 Research Project B:

School Assessment (70%)

Assessment Type 1: Folio (30%)

Assessment Type 2: Research Outcome (40%)

External Assessment (30%)

- Assessment Type 3: Evaluation (30%).

2. Assessment Design Criteria

The assessment design criteria are based on the learning requirements and are used by:

- teachers to clarify for the student what he or she needs to learn

- teachers and assessors to design opportunities for the student to provide evidence of his or her learning at the highest possible level of achievement.

The assessment design criteria consist of specific features that:

- students should demonstrate in their learning

- teachers and assessors look for as evidence that students have met the learning requirements.

For this subject the assessment design criteria are:

- development

The specific features of these criteria are described below.

The set of assessments, as a whole, must give students opportunities to demonstrate each of the specific features by the completion of study of the subject.

2.1. Planning

The specific features are as follows:

- P1: Consideration and refinement of a research question.

- P2: Planning of research processes appropriate to the research question.

2.2. Development

- D1: Development of the research.

- D2: Analysis of information and exploration of ideas to develop the research.

- D3: Development of knowledge and skills specific to the research question.

- D4: Understanding and development of one or more capabilities.

2.3. Synthesis

- S1: Synthesis of knowledge, skills, and ideas to produce a resolution to the research question.

- S2: Substantiation of key findings relevant to the Research Outcome.

- S3: Expression of ideas.

2.4. Evaluation

- E1: Evaluation of the research processes used, specific to the research question.

- E2: Evaluation of decisions made in response to challenges and/or opportunities specific to the research processes used.

- E3: Evaluation of the quality of the Research Outcome.

3. School Assessment

The Folio is a record of the student’s research. Students develop a research question and then select and present evidence of their learning from the planning and development stages of the research project. The Folio includes a proposal (evidence of planning), and evidence of the research development, which may take a variety of forms, including a discussion.

- consider and define a research question, and outline their initial ideas for the research

- consider and select research processes that are likely to be appropriate to their research question (i.e. valid, ethical, and manageable research processes).

Evidence could include:

- guiding questions

- a written statement

- an oral discussion

- a multimedia presentation,

that may lead to the development of, and its incorporation in, a management plan.

Research Development

- develop the research, including knowledge and skills specific to the research question

- organise and analyse information gathered

- explore ideas

- understand and develop one or more capabilities.

- information collected, selected, annotated, and analysed, and ideas explored in relation to the research question

Examples include: notes, drafts, letters, sketches, plans, models, interview notes, observations, trials, reflections, data from experiments, records of visits or fieldwork, photographs, annotations, feedback, translations, and interpretations

- responses to feedback, interactions, questions, and problem-solving

Examples include: major activities, insights, turning points, and problems encountered

- recordings of discussions with the teacher (either digital or in the form of notes taken by the student) about how the research is developing, the research processes used, ideas that are developing through the research, and the knowledge and skills being developed and applied.

For this assessment type, students provide evidence of their learning in relation to all specific features of the following assessment design criteria:

Refer to the subject operational information on the Research Project minisite on the SACE website ( www.sace.sa.edu.au ) for details about materials to be submitted for moderation.

The Research Outcome is the resolution of the research question, through the presentation of the key findings from the research.

Students identify the intended audience for their Research Outcome, and consider the value of their research to this audience. The form and language of the Research Outcome should be appropriate to the intended audience.

In resolving the research question, students come to a position or conclusion as a response to their research question.

Students synthesise their key findings (knowledge, skills, and ideas) to produce a Research Outcome and substantiate these with evidence and examples from their research to show how they resolved the research question.

The Research Outcome must include the key findings and substantiation. The Research Outcome can take the form of:

Examples include: an essay, a report, an oral or written history, with appropriate in-text referencing and a bibliography and/or references list; a multimedia presentation; a documented science experiment

Students negotiate with their teacher suitable forms for producing their Research Outcome, for example:

- written results, conclusions, recommendations, or solutions to a problem or question (e.g. an essay, a report, a booklet, or an article)

- a product (e.g. an artefact, a manufactured article, or a work of art or literature) and a producer’s statement

- a display or exhibition with annotations

- a multimedia presentation and podcast

- a performance (live or recorded) with a supporting statement

- a combination of any of the above.

Students submit their Research Outcome to the teacher and, if they choose, present it to a broader audience (e.g. other students or community members).

Evidence of the Research Outcome must be:

- a maximum of 2000 words if written

- a maximum of 12 minutes for an oral presentation

- the equivalent in multimodal form.

For this assessment type, students provide evidence of their learning in relation to all specific features of the following assessment design criterion:

4. External Assessment

Assessment Type 3: Evaluation (30%)

The Evaluation is a series of judgments about the research processes used and the Research Outcome produced.

For this assessment type, students:

- evaluate the usefulness of the research processes used specific to the research question.

Students make judgments about the effectiveness of processes they used to collect information as part of their research (e.g. qualitative and quantitative research, practical experimentation, fieldwork). They make reference to specific sources of information to provide examples of the usefulness of the research processes.

- evaluate decisions made in response to challenges and/or opportunities specific to the research processes used.

Students make judgments about their actions when faced with challenges and/or opportunities while using research processes. They draw conclusions about the effect of these actions on the research.

- evaluate the quality of the Research Outcome.

Students make balanced judgments about the quality of their Research Outcome with a focus on the significance of their findings, and the particular features that influence the overall value and worth of their Research Outcome, including the extent to which the question has been resolved.

- organise their information coherently and communicate ideas accurately and appropriately.

Students prepare a written summary of the research question and the Research Outcome, to a maximum of 150 words. This summary is assessed.

Students must present their Evaluation in written form to a maximum of 1500 words (excluding the written summary).

The Evaluation can include visual material (e.g. photographs and diagrams), integrated into the written text.

The following specific features of the assessment design criteria for this subject are assessed in the external assessment component:

- evaluation — E1, E2, and E3

- synthesis — S3.

5. Performance Standards

The performance standards describe five levels of achievement, A to E.

Each level of achievement describes the knowledge, skills, and understanding that teachers and assessors refer to in deciding how well a student has demonstrated his or her learning on the basis of the evidence provided.

During the teaching and learning program the teacher gives students feedback on their learning, with reference to the performance standards.

At the student’s completion of study of each school assessment type, the teacher makes a decision about the quality of the student’s learning by:

- referring to the performance standards

- assigning a grade between A+ and E- for the assessment type.

The student’s school assessment and external assessment are combined for a final result, which is reported as a grade between A+ and E-.

6. Assessment Integrity

The SACE Assuring Assessment Integrity Policy outlines the principles and processes that teachers and assessors follow to assure the integrity of student assessments. This policy is available on the SACE website (www.sace.sa.edu.au) as part of the SACE Policy Framework.

The SACE Board uses a range of quality assurance processes so that the grades awarded for student achievement, in both the school assessment and the external assessment, are applied consistently and fairly against the performance standards for a subject, and are comparable across all schools.

Information and guidelines on quality assurance in assessment at Stage 2 are available on the SACE website (www.sace.sa.edu.au).

IV. SUPPORT MATERIALS

1. Subject-specific Advice

Online support materials are provided for each subject and updated regularly on the SACE website ( www.sace.sa.edu.au ). Examples of support materials are sample learning and assessment plans, annotated assessment tasks, annotated student responses, and recommended resource materials.

2. Advice on Ethical Study and Research

Advice for students and teachers on ethical study and research practices is available in the guidelines on the ethical conduct of research in the SACE on the SACE website ( www.sace.sa.edu.au ).

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Environment | Climate-change research project aboard USS…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Today's E-Edition

- Commercial Real Estate

- Marketplace

- The Mercury News

Environment

Environment | climate-change research project aboard uss hornet paused for environmental review, after city raised concerns, scientists agreed to delay but reasserted safety of spraying salt water into air.

The city asked the Hornet’s administrators and the University of Washington to stop the experiment, stating it was in violation of the Hornet’s lease with the city and was taking place without the city’s knowledge, officials announced in a Facebook post May 4. The experiment is not allowed under the ship’s museum operations outlined in its lease, Jennifer Ott, Alameda’s city manager, wrote in a letter to the Hornet which was shared with Bay Area News Group by the city.

The city has contracted biological and hazardous material consultants to independently investigate the environmental safety and health of the experiment, officials said in the post, adding that “there is no indication that the spray from the previous experiments presented a threat to human health or the environment.”

The program stopped its experiments prior to Alameda’s public announcement, according to a statement released by Dr. Rob Wood, principal investigator and Dr. Sarah Doherty, program director. The scientists added that the city was informed of the study’s corresponding educational exhibit in advance but asked for a closer review of the study after news articles released details in April.

“This type of review was not unexpected given that the approach in undertaking the studies and engaging with the public on the USS Hornet … is something new,” Wood and Doherty wrote. “We are happy to support their review and it has been a highly constructive process so far.”

The Marine Cloud Brightening Project aims to test whether ejecting plumes of microscopic droplets of salt water into the clouds will make them more reflective, helping to counteract warming climates by sending heat back up into the sky instead of allowing it down to the ground. Based out of the University of Washington, the program partnered with the U.S.S. Hornet, a World War II-era aircraft carrier-turned museum which is perpetually docked on the coast of Alameda, to conduct experiments on its top deck.

The team of scientists and engineers developed the spray technology and nozzle designs over the course of several years in the lab and launched the next phase of the study — testing whether the theory works in actual atmospheric conditions — in April. Scientists had planned to test the technology over the course of several months and measure its effectiveness with computer models.

Before beginning tests on the Hornet, the program went through an expert assessment of requirements and “found that the study does not exceed established regulatory or permitting thresholds,” Wood and Doherty wrote. The plumes of salt water “operate well below established thresholds for environmental or human health impact for emissions.”

A comment on the city’s Facebook post from the USS Hornet’s account read in part: “We believed that our existing permits and lease covered these activities when we started. As we now know, there was a gap in communication and understanding of the scope of the project and we are committed to working with the City to meet all of their needs regarding this effort.”

The findings will be presented to the Alameda City Council in June and will be shared with the public, according to the post.

“We continue to appreciate our engagement with the community on the nature of this type of research study, which is not designed to impact clouds, the environment or climate,” Wood and Doherty wrote.

More in Environment

Environment | Can’t install your own solar panels? Some areas let you join a community project

Environment | Tire toxicity faces fresh scrutiny after salmon die-offs

Environment | Exxon and Chevron output booms in world’s hottest oil patches

Environment | Share water bottles? Use refill shampoo pouches? New concepts in cutting plastic pollution

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

What are the strengths and limitations to utilising creative methods in public and patient involvement in health and social care research? A qualitative systematic review

- Olivia R. Phillips 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Cerian Harries 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Jo Leonardi-Bee 1 , 2 , 4 na1 ,

- Holly Knight 1 , 2 ,

- Lauren B. Sherar 2 , 3 ,

- Veronica Varela-Mato 2 , 3 &

- Joanne R. Morling 1 , 2 , 5

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 10 , Article number: 48 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is increasing interest in using patient and public involvement (PPI) in research to improve the quality of healthcare. Ordinarily, traditional methods have been used such as interviews or focus groups. However, these methods tend to engage a similar demographic of people. Thus, creative methods are being developed to involve patients for whom traditional methods are inaccessible or non-engaging.

To determine the strengths and limitations to using creative PPI methods in health and social care research.

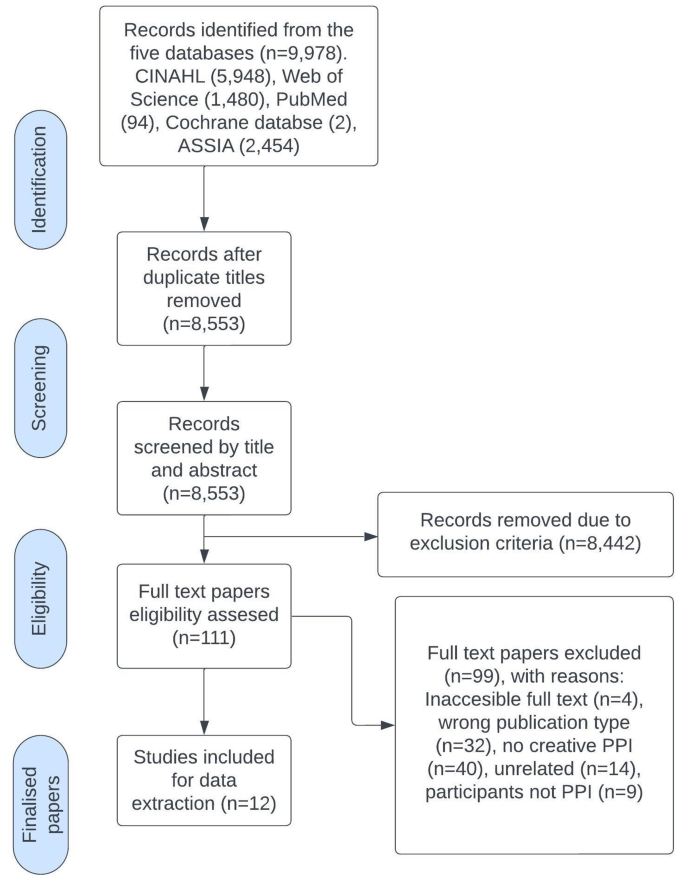

Electronic searches were conducted over five databases on 14th April 2023 (Web of Science, PubMed, ASSIA, CINAHL, Cochrane Library). Studies that involved traditional, non-creative PPI methods were excluded. Creative PPI methods were used to engage with people as research advisors, rather than study participants. Only primary data published in English from 2009 were accepted. Title, abstract and full text screening was undertaken by two independent reviewers before inductive thematic analysis was used to generate themes.

Twelve papers met the inclusion criteria. The creative methods used included songs, poems, drawings, photograph elicitation, drama performance, visualisations, social media, photography, prototype development, cultural animation, card sorting and persona development. Analysis identified four limitations and five strengths to the creative approaches. Limitations included the time and resource intensive nature of creative PPI, the lack of generalisation to wider populations and ethical issues. External factors, such as the lack of infrastructure to support creative PPI, also affected their implementation. Strengths included the disruption of power hierarchies and the creation of a safe space for people to express mundane or “taboo” topics. Creative methods are also engaging, inclusive of people who struggle to participate in traditional PPI and can also be cost and time efficient.

‘Creative PPI’ is an umbrella term encapsulating many different methods of engagement and there are strengths and limitations to each. The choice of which should be determined by the aims and requirements of the research, as well as the characteristics of the PPI group and practical limitations. Creative PPI can be advantageous over more traditional methods, however a hybrid approach could be considered to reap the benefits of both. Creative PPI methods are not widely used; however, this could change over time as PPI becomes embedded even more into research.

Plain English Summary

It is important that patients and public are included in the research process from initial brainstorming, through design to delivery. This is known as public and patient involvement (PPI). Their input means that research closely aligns with their wants and needs. Traditionally to get this input, interviews and group discussions are held, but this can exclude people who find these activities non-engaging or inaccessible, for example those with language challenges, learning disabilities or memory issues. Creative methods of PPI can overcome this. This is a broad term describing different (non-traditional) ways of engaging patients and public in research, such as through the use or art, animation or performance. This review investigated the reasons why creative approaches to PPI could be difficult (limitations) or helpful (strengths) in health and social care research. After searching 5 online databases, 12 studies were included in the review. PPI groups included adults, children and people with language and memory impairments. Creative methods included songs, poems, drawings, the use of photos and drama, visualisations, Facebook, creating prototypes, personas and card sorting. Limitations included the time, cost and effort associated with creative methods, the lack of application to other populations, ethical issues and buy-in from the wider research community. Strengths included the feeling of equality between academics and the public, creation of a safe space for people to express themselves, inclusivity, and that creative PPI can be cost and time efficient. Overall, this review suggests that creative PPI is worthwhile, however each method has its own strengths and limitations and the choice of which will depend on the research project, PPI group characteristics and other practical limitations, such as time and financial constraints.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Patient and public involvement (PPI) is the term used to describe the partnership between patients (including caregivers, potential patients, healthcare users etc.) or the public (a community member with no known interest in the topic) with researchers. It describes research that is done “‘with’ or ‘by’ the public, rather than ‘to,’ ‘about’ or ‘for’ them” [ 1 ]. In 2009, it became a legislative requirement for certain health and social care organisations to include patients, families, carers and communities in not only the planning of health and social care services, but the commissioning, delivery and evaluation of them too [ 2 ]. For example, funding applications for the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR), a UK funding body, mandates a demonstration of how researchers plan to include patients/service users, the public and carers at each stage of the project [ 3 ]. However, this should not simply be a tokenistic, tick-box exercise. PPI should help formulate initial ideas and should be an instrumental, continuous part of the research process. Input from PPI can provide unique insights not yet considered and can ensure that research and health services are closely aligned to the needs and requirements of service users PPI also generally makes research more relevant with clearer outcomes and impacts [ 4 ]. Although this review refers to both patients and the public using the umbrella term ‘PPI’, it is important to acknowledge that these are two different groups with different motivations, needs and interests when it comes to health research and service delivery [ 5 ].

Despite continuing recognition of the need of PPI to improve quality of healthcare, researchers have also recognised that there is no ‘one size fits all’ method for involving patients [ 4 ]. Traditionally, PPI methods invite people to take part in interviews or focus groups to facilitate discussion, or surveys and questionnaires. However, these can sometimes be inaccessible or non-engaging for certain populations. For example, someone with communication difficulties may find it difficult to engage in focus groups or interviews. If individuals lack the appropriate skills to interact in these types of scenarios, they cannot take advantage of the participation opportunities it can provide [ 6 ]. Creative methods, however, aim to resolve these issues. These are a relatively new concept whereby researchers use creative methods (e.g., artwork, animations, Lego), to make PPI more accessible and engaging for those whose voices would otherwise go unheard. They ensure that all populations can engage in research, regardless of their background or skills. Seminal work has previously been conducted in this area, which brought to light the use of creative methodologies in research. Leavy (2008) [ 7 ] discussed how traditional interviews had limits on what could be expressed due to their sterile, jargon-filled and formulaic structure, read by only a few specialised academics. It was this that called for more creative approaches, which included narrative enquiry, fiction-based research, poetry, music, dance, art, theatre, film and visual art. These practices, which can be used in any stage of the research cycle, supported greater empathy, self-reflection and longer-lasting learning experiences compared to interviews [ 7 ]. They also pushed traditional academic boundaries, which made the research accessible not only to researchers, but the public too. Leavy explains that there are similarities between arts-based approaches and scientific approaches: both attempts to investigate what it means to be human through exploration, and used together, these complimentary approaches can progress our understanding of the human experience [ 7 ]. Further, it is important to acknowledge the parallels and nuances between creative and inclusive methods of PPI. Although creative methods aim to be inclusive (this should underlie any PPI activity, whether creative or not), they do not incorporate all types of accessible, inclusive methodologies e.g., using sign language for people with hearing impairments or audio recordings for people who cannot read. Given that there was not enough scope to include an evaluation of all possible inclusive methodologies, this review will focus on creative methods of PPI only.

We aimed to conduct a qualitative systematic review to highlight the strengths of creative PPI in health and social care research, as well as the limitations, which might act as a barrier to their implementation. A qualitative systematic review “brings together research on a topic, systematically searching for research evidence from primary qualitative studies and drawing the findings together” [ 8 ]. This review can then advise researchers of the best practices when designing PPI.

Public involvement

The PHIRST-LIGHT Public Advisory Group (PAG) consists of a team of experienced public contributors with a diverse range of characteristics from across the UK. The PAG was involved in the initial question setting and study design for this review.

Search strategy

For the purpose of this review, the JBI approach for conducting qualitative systematic reviews was followed [ 9 ]. The search terms were (“creativ*” OR “innovat*” OR “authentic” OR “original” OR “inclu*”) AND (“public and patient involvement” OR “patient and public involvement” OR “public and patient involvement and engagement” OR “patient and public involvement and engagement” OR “PPI” OR “PPIE” OR “co-produc*” OR “co-creat*” OR “co-design*” OR “cooperat*” OR “co-operat*”). This search string was modified according to the requirements of each database. Papers were filtered by title, abstract and keywords (see Additional file 1 for search strings). The databases searched included Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, ASSIA and CINAHL. The Cochrane Library was also searched to identify relevant reviews which could lead to the identification of primary research. The search was conducted on 14/04/23. As our aim was to report on the use of creative PPI in research, rather than more generic public engagement, we used electronic databases of scholarly peer-reviewed literature, which represent a wide range of recognised databases. These identified studies published in general international journals (WoS, PubMed), those in social sciences journals (ASSIA), those in nursing and allied health journals (CINAHL), and trials of interventions (Cochrane Library).

Inclusion criteria

Only full-text, English language, primary research papers from 2009 to 2023 were included. This was the chosen timeframe as in 2009 the Health and Social Reform Act made it mandatory for certain Health and Social Care organisations to involve the public and patients in planning, delivering, and evaluating services [ 2 ]. Only creative methods of PPI were accepted, rather than traditional methods, such as interviews or focus groups. For the purposes of this paper, creative PPI included creative art or arts-based approaches (e.g., e.g. stories, songs, drama, drawing, painting, poetry, photography) to enhance engagement. Titles were related to health and social care and the creative PPI was used to engage with people as research advisors, not as study participants. Meta-analyses, conference abstracts, book chapters, commentaries and reviews were excluded. There were no limits concerning study location or the demographic characteristics of the PPI groups. Only qualitative data were accepted.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [ 10 ] was conducted by the primary authors (ORP and CH). This was done independently, and discrepancies were discussed and resolved. If a consensus could not be reached, a third independent reviewer was consulted (JRM). The full list of quality appraisal questions can be found in Additional file 2 .

Data extraction

ORP extracted the study characteristics and a subset of these were checked by CH. Discrepancies were discussed and amendments made. Extracted data included author, title, location, year of publication, year study was carried out, research question/aim, creative methods used, number of participants, mean age, gender, ethnicity of participants, setting, limitations and strengths of creative PPI and main findings.

Data analysis

The included studies were analysed using inductive thematic analysis [ 11 ], where themes were determined by the data. The familiarisation stage took place during full-text reading of the included articles. Anything identified as a strength or limitation to creative PPI methods was extracted verbatim as an initial code and inputted into the data extraction Excel sheet. Similar codes were sorted into broader themes, either under ‘strengths’ or ‘limitations’ and reviewed. Themes were then assigned a name according to the codes.

The search yielded 9978 titles across the 5 databases: Web of Science (1480 results), PubMed (94 results), ASSIA (2454 results), CINAHL (5948 results) and Cochrane Library (2 results), resulting in 8553 different studies after deduplication. ORP and CH independently screened their titles and abstracts, excluding those that did not meet the criteria. After assessment, 12 studies were included (see Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process

Study characteristics

The included studies were published between 2018 and 2022. Seven were conducted in the UK [ 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 23 ], two in Canada [ 21 , 22 ], one in Australia [ 13 ], one in Norway [ 16 ] and one in Ireland [ 20 ]. The PPI activities occurred across various settings, including a school [ 12 ], social club [ 12 ], hospital [ 17 ], university [ 22 ], theatre [ 19 ], hotel [ 20 ], or online [ 15 , 21 ], however this information was omitted in 5 studies [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 18 , 23 ]. The number of people attending the PPI sessions varied, ranging from 6 to 289, however the majority (ten studies) had less than 70 participants [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Seven studies did not provide information on the age or gender of the PPI groups. Of those that did, ages ranged from 8 to 76 and were mostly female. The ethnicities of the PPI group members were also rarely recorded (see Additional file 3 for data extraction table).

Types of creative methods

The type of creative methods used to engage the PPI groups were varied. These included songs, poems, drawings, photograph elicitation, drama performance, visualisations, Facebook, photography, prototype development, cultural animation, card sorting and creating personas (see Table 1 ). These were sometimes accompanied by traditional methods of PPI such as interviews and focus group discussions.

The 12 included studies were all deemed to be of good methodological quality, with scores ranging from 6/10 to 10/10 with the CASP critical appraisal tool [ 10 ] (Table 2 ).

Thematic analysis

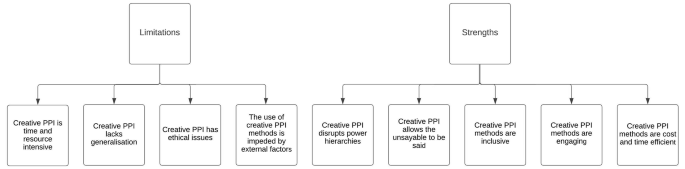

Analysis identified four limitations and five strengths to creative PPI (see Fig. 2 ). Limitations included the time and resource intensity of creative PPI methods, its lack of generalisation, ethical issues and external factors. Strengths included the disruption of power hierarchies, the engaging and inclusive nature of the methods and their long-term cost and time efficiency. Creative PPI methods also allowed mundane and “taboo” topics to be discussed within a safe space.

Theme map of strengths and limitations

Limitations of creative PPI

Creative ppi methods are time and resource intensive.

The time and resource intensive nature of creative PPI methods is a limitation, most notably for the persona-scenario methodology. Valaitis et al. [ 22 ] used 14 persona-scenario workshops with 70 participants to co-design a healthcare intervention, which aimed to promote optimal aging in Canada. Using the persona method, pairs composed of patients, healthcare providers, community service providers and volunteers developed a fictional character which they believed represented an ‘end-user’ of the healthcare intervention. Due to the depth and richness of the data produced the authors reported that it was time consuming to analyse. Further, they commented that the amount of information was difficult to disseminate to scientific leads and present at team meetings. Additionally, to ensure the production of high-quality data, to probe for details and lead group discussion there was a need for highly skilled facilitators. The resource intensive nature of the creative co-production was also noted in a study using the persona scenario and creative worksheets to develop a prototype decision support tool for individuals with malignant pleural effusion [ 17 ]. With approximately 50 people, this was also likely to yield a high volume of data to consider.

To prepare materials for populations who cannot engage in traditional methods of PPI was also timely. Kearns et al. [ 18 ] developed a feedback questionnaire for people with aphasia to evaluate ICT-delivered rehabilitation. To ensure people could participate effectively, the resources used during the workshops, such as PowerPoints, online images and photographs, had to be aphasia-accessible, which was labour and time intensive. The author warned that this time commitment should not be underestimated.

There are further practical limitations to implementing creative PPI, such as the costs of materials for activities as well as hiring a space for workshops. For example, the included studies in this review utilised pens, paper, worksheets, laptops, arts and craft supplies and magazines and took place in venues such as universities, a social club, and a hotel. Further, although not limited to creative PPI methods exclusively but rather most studies involving the public, a financial incentive was often offered for participation, as well as food, parking, transport and accommodation [ 21 , 22 ].

Creative PPI lacks generalisation

Another barrier to the use of creative PPI methods in health and social care research was the individual nature of its output. Those who participate, usually small in number, produce unique creative outputs specific to their own experiences, opinions and location. Craven et al. [ 13 ], used arts-based visualisations to develop a toolbox for adults with mental health difficulties. They commented, “such an approach might still not be worthwhile”, as the visualisations were individualised and highly personal. This indicates that the output may fail to meet the needs of its end-users. Further, these creative PPI groups were based in certain geographical regions such as Stoke-on-Trent [ 19 ] Sheffield [ 23 ], South Wales [ 12 ] or Ireland [ 20 ], which limits the extent the findings can be applied to wider populations, even within the same area due to individual nuances. Further, the study by Galler et al. [ 16 ], is specific to the Norwegian context and even then, maybe only a sub-group of the Norwegian population as the sample used was of higher socioeconomic status.

However, Grindell et al. [ 17 ], who used persona scenarios, creative worksheets and prototype development, pointed out that the purpose of this type of research is to improve a certain place, rather than apply findings across other populations and locations. Individualised output may, therefore, only be a limitation to research wanting to conduct PPI on a large scale.

If, however, greater generalisation within PPI is deemed necessary, then social media may offer a resolution. Fedorowicz et al. [ 15 ], used Facebook to gain feedback from the public on the use of video-recording methodology for an upcoming project. This had the benefit of including a more diverse range of people (289 people joined the closed group), who were spread geographically around the UK, as well as seven people from overseas.

Creative PPI has ethical issues

As with other research, ethical issues must be taken into consideration. Due to the nature of creative approaches, as well as the personal effort put into them, people often want to be recognised for their work. However, this compromises principles so heavily instilled in research such as anonymity and confidentiality. With the aim of exploring issues related to health and well-being in a town in South Wales, Byrne et al. [ 12 ], asked year 4/5 and year 10 pupils to create poems, songs, drawings and photographs. Community members also created a performance, mainly of monologues, to explore how poverty and inequalities are dealt with. Byrne noted the risks of these arts-based approaches, that being the possibility of over-disclosure and consequent emotional distress, as well as people’s desire to be named for their work. On one hand, the anonymity reduces the sense of ownership of the output as it does not portray a particular individual’s lived experience anymore. On the other hand, however, it could promote a more honest account of lived experience. Supporting this, Webber et al. [ 23 ], who used the persona method to co-design a back pain educational resource prototype, claimed that the anonymity provided by this creative technique allowed individuals to externalise and anonymise their own personal experience, thus creating a more authentic and genuine resource for future users. This implies that anonymity can be both a limitation and strength here.

The use of creative PPI methods is impeded by external factors

Despite the above limitations influencing the implementation of creative PPI techniques, perhaps the most influential is that creative methodologies are simply not mainstream [ 19 ]. This could be linked to the issues above, like time and resource intensity, generalisation and ethical issues but it is also likely to involve more systemic factors within the research community. Micsinszki et al. [ 21 ], who co-designed a hub for the health and well-being of vulnerable populations, commented that there is insufficient infrastructure to conduct meaningful co-design as well as a dominant medical model. Through a more holistic lens, there are “sociopolitical environments that privilege individualism over collectivism, self-sufficiency over collaboration, and scientific expertise over other ways of knowing based on lived experience” [ 21 ]. This, it could be suggested, renders creative co-design methodologies, which are based on the foundations of collectivism, collaboration and imagination an invalid technique in the research field, which is heavily dominated by more scientific methods offering reproducibility, objectivity and reliability.

Although we acknowledge that creative PPI techniques are not always appropriate, it may be that their main limitation is the lack of awareness of these methods or lack of willingness to use them. Further, there is always the risk that PPI, despite being a mandatory part of research, is used in a tokenistic or tick-box fashion [ 20 ], without considering the contribution that meaningful PPI could make to enhancing the research. It may be that PPI, let alone creative PPI, is not at the forefront of researchers’ minds when planning research.

Strengths of creative PPI

Creative ppi disrupts power hierarchies.