108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best gambling topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ good research topics about gambling, 👍 simple & easy gambling essay titles, ❓ research questions on gambling.

- Gambling Benefits and Disadvantages Also in relation to this, the gambling industry offers employment to a myriad of people. This is thus a boost to the economy of the local people.

- Gambling Should Be Illegal Furthermore, gambling leads to lowering reputation of the city in question as a result of the crimes associated. The government is forced to spend a lot of money in controlling crime and rehabilitating addicted gamblers. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Online Gambling Addiction Gambling is an addiction as one becomes dependent on the activity; he cannot do without it, it becomes a necessity to him. Online gambling is more of an addiction than a game to the players.

- Gambling’s Positive and Negative Effects In some cases such as in lotteries, the financial reward is incidental and secondary because the participants drive is to help raise funds for the course the lottery promotes.

- Internet Gambling and Its Impact on the Youth However, it is necessary to remember that apart from obvious issues with gambling, it is also associated with higher crime rates and it is inevitable that online gambling will fuel an increase of crime rates […]

- Comorbid Gambling Disorder and Alcohol Dependence The patient was alert and oriented to the event, time, and place and appropriately dressed for the occasion, season, and weather.

- Gambling: Debate Against the Legislation of Gambling More significantly, the Australian government has so far adopted a conciliatory and indulgent attitude towards most kinds of gambling, which has been the main reason for the rampant growth and proliferation of both forms of […]

- Impact of Internet Use, Online Gaming, and Gambling Among College Students The researchers refute the previous works of literature that have analyzed the significance of the Internet, whereby previous studies depict that the Internet plays a significant role in preventing depression ordeals and making people happy.

- History of Gambling in the US and How It Connects With the Current Times It is possible to note that it is in the Americans’ blood from the sides of Native Americans and the Pilgrims to bet.

- Effects of Gambling on Happiness: Research in the Nursing Homes The objective of the study was to determine whether the elderly in the nursing homes would prefer the introduction of gambling as a happiness stimulant.

- The Era of Legalized Gambling Importantly, they build on each other to demonstrate power in taking risk action and actually how legalizations of the practice can influence character integrity. The conclusive speculation is whether there is a changing definition of […]

- Gambling as an Acceptable Form of Leisure In leisure one should have the freedom to choose which activity to engage in and at what time to do it. Gambling is considered as a form of leisure activity and one has freedom to […]

- Legalization of Casino Gambling in Hong Kong Thus, the problem is in the controversy of the allegedly positive and negative effects of gambling legalization on the social and economic development of Hong Kong.

- Internet Gambling Issue Description There are certain new features added to the gambling game by the internet gamblers, such as proxy gambling, gambling for credit and claim of gambling in the virtual offshore gambling environment.

- The Problem of Gambling in the Modern Society as the Type of Addiction Old people and adolescents, rich and poor, all of them may become the prisoners of this addiction and the only way out may be the treatment, serious psychological treatment, as gambling addiction is the disease […]

- The Psychology of Lottery Gambling This kind of gambling also refers to the expenditure of more currency than was first future and then returning afterward to win the cash lost in the history.

- Gambling, Fraud and Security in Banking By supervising the institutions and banks, there exists openness into the dealings of the banks and this allows investors to get full information about the banks before investing.

- High-Risk Gambles Prevention in Banking The elements of a valid contract between banks and their customers vary according to the context of the contract. This involves the willingness and devotion of both parties to a particular cause.

- Earmark Gambling Revenue Legislation in Illinois The state of Illinois enacted PA 91-40 in 1999, which has affected the gaming industry. The growth in the revenue from gambling has attracted the attention of lawmakers.

- Jay Cohen’s Gambling Company and American Laws Disregarding the controversy concerning the harmful effects of gambling, one might want to ask the question concerning whether the USA had the right to question the policies of other states, even on such a dubious […]

- Fantasy Football: Gambling Regulation and Outlawing Taking this into consideration, it can be stated that fantasy football and its other iterations on sites like Draft Kings is not a form of gambling.

- Gambling and Addiction’s Effects on Neuroplasticity It was established further that blood flow from other parts of the body to the brain is changes whenever an individual engages in gambling, which is similar to the intake of cocaine.

- Gambling and Its Effect on Families The second notable effect of gambling on families is that it results in the increased cases of domestic violence. The third notable effect of gambling on the family is that it increases child abuse and […]

- Online Gambling Legalization When asked about the unavoidable passing of a law decriminalizing online gambling in the US, the CEO of Sams Casino stated that the legislation would not have any impact on their trade.

- Casino Gambling Legalization in Texas In spite of the fact that the idea of legalizing casino gambling is often discussed by opponents as the challenge to the community’s social health, Texas should approve the legalization of casino gambling because this […]

- Economic Issues: Casino Gambling Evidence from several surveys suggests that the competition from various states within the US has contributed to the growth and expansion of casinos. The growth and expansion of casinos has been fueled by competition from […]

- Casino Gambling Industry Trends This will make suppliers known to the rest of the companies operating in the industry. The bargaining power of the supplier in the casino gambling industry is also high.

- Gambling Addiction Research Approaches Therefore, it is possible to claim that the disease model is quite a comprehensive approach which covers several possible factors which lead to the development of the disorder.

- Public Policy on Youth Gambling The outcomes of the research would be useful in identifying the program outcomes as well as provide answers to the whys of youth gambling.

- Gambling and Gaming Industry Compulsive gambling Compulsive gambling refers to the inability to control an individual’s urge to engage in gambling activities. Other gambling activities in the state are classified as a misdemeanour.

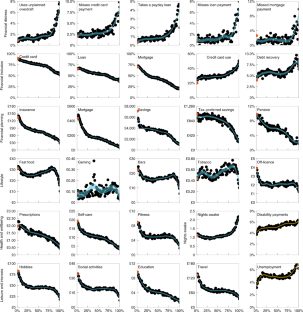

- Revision of Problem Gambling The reasoning behind the researchers’ decision to focus on the social and financial factors of gambling within the UK is because of the significant increase in gambling-related problems within Britain.

- Impact of Gambling on the Bahamian Economy Sources from the government of The Bahamas indicate that the first of gambling casinos in the name of the Bahamian Club opened for business from the capital of Nassau towards the close of the 1920s […]

- Positive Aspects of Gambling It is therefore essential for sociologist to understand the positive aspects of gambling and the impact that it has on our lives. However, it is essential to control the level of gambling.

- Argument for Legalization of Gambling in Texas The subject of gambling is that the gambler losses the money offered if the outcome of the event is against him or her or gains the money offered if the event outcome favors the gambler.

- Gambling in Kentucky: Moral Obligations vs. the Economical Reasons The industries that added to the well-being of the state and its GNP since the day the state was founded and throughout the past century was the coal mining, which contributed to the state’s income […]

- Gambling in Ohio The purpose of this project is to investigate the history of gambling in Ohio, its development in the 1990s, and its impact on ordinary human lives in order to underline the significance of this process […]

- Gambling Projects: Impact on the Cultural Transformations in America The high rates of unemployment and low earning levels may coerce residents to engage in gambling, hoping that they would enrich themselves.

- Gambling in Four Perspectives A gambler faces the challenge of imminent effect of addiction to the effects of gambling every time he continues with the exercise of gambling something that may take long to drop.

- Gambling Discusses Three Causes or Effects of Gambling and Their Impact on Society

- Taking the Risk: Love, Luck, and Gambling in Literature

- Financial Crime and Gambling in a Virtual World

- Management and Information Issues for Industries With Externalities: The Case of Casino Gambling

- Internet Gambling Consumers Industry and Regulation

- Human Resource Management for Gambling Industry

- Youth Gambling Abuse: Issues and Challenges to Counselling

- Differentiate Between Investment Speculation and Gambling

- The Gambling and Its Influence on the Individual and Society

- Assessing the Differential Impacts of Online, Mixed, and Offline Gambling

- Gambling Taxation: Public Equity in the Gambling Business

- Risk and Protective Factors in Problem Gambling: An Examination of Psychological Resilience

- Behavioral Accounts and Treatments of Problem Gambling

- Cognitive Remediation Interventions for Gambling Disorder

- Gambling: The Problems and History of Addiction, Helpfulness, and Tragedy

- Casino Gambling Myths and Facts: When Fun Becomes Dangerous

- Associations Between Problem Gambling, Socio-Demographics, Mental Health Factors, and Gambling Type

- Gambling With the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice

- Differences in Effects on Brain Functional Connectivity in Patients With Internet-Based Gambling Disorder and Internet Gaming Disorder

- Gambling Addiction Hidden Evils of Online Play

- Diagnosing and Treating Pathological Addictions: Compulsive Gambling, Drugs, and Alcohol Addiction

- The Pleasure Principle: Gambling and Brain Chemistry

- Gambling, Geographical Variations, and Deprivation: Findings From the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey

- Behavior Change Strategies for Problem Gambling: An Analysis of Online Posts

- Economic Recession Affects Gambling Participation but Not Problematic Gambling: Results From a Population-Based Follow-up Study

- Different Gambling Consequence Western Civilisation Countries Sociology

- Gambling Among Culturally Diverse Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Data

- Decision-Making Under Risk, but Not Under Ambiguity, Predicts Pathological Gambling in Discrete Types of Abstinent Substance Users

- Gambling: The Game Where Everyone Is a Loser

- The Problems and Issues Concerning Legalization of Online Gambling

- Gambling Attitudes and Beliefs Associated With Problem Gambling: The Cohort Effect of Baby Boomers

- Pathological Compulsive Gambling: Diagnosis and Treatment of a Medical Disorder

- Accounting and Financial Reports in the Gambling Monopoly – Measures for a Moral Economic System

- Gender, Gambling Settings and Gambling Behaviors Among Undergraduate Poker Players

- Gambling Among Young Croatian People: An Exploratory Study of the Relationship Between Psychopathic Traits, Risk-Taking Tendencies, and Gambling-Related Problems

- Buying and Selling Price for Risky Lotteries and Expected Utility Theory With Gambling Wealth

- Charitable Giving and Charitable Gambling: Cognitive Abilities, Non-cognitive Skills, and Gambling Behaviors

- Compulsive Buying Behavior: Characteristics of Comorbidity With Gambling Disorder

- Motivation, Personality Type, and the Choice Between Skill and Luck Gambling Products

- Gambling and the Use of Credit: An Individual and Household Level Analysis

- Why Will Internet Gambling Prohibition Ultimately Fail?

- How Do Binge Drinking, Gambling, and Procrastinating Affect Students?

- What Motivates Gambling Behavior?

- Does Charitable Gamble Crowd Out Charitable Donations?

- What Should the State’s Policy Be On Gambling?

- How Does Gambling Effect the Economy?

- What Does the Bible Say About Gambling?

- Are There Gambling Effects in Incentive-Compatible Elicitations of Reservation Prices?

- How Does the Gambling Affect the Society?

- Does Indian Casino Gambling Reduce State Revenues?

- How Does the Stigma of Problem Gambling Influence Help-Seeking, Treatment, and Recovery?

- Why Are Gambling Markets Organised So Differently From Financial Markets?

- Can Expected Utility Theory Explain Gambling?

- What Is the Attraction to Gambling?

- Should Sports Gambling Be Legalized?

- Who Gets Hurt From Gambling?

- How Do Gambling Addiction Affect Families?

- Does Individual Gambling Behavior Vary Across Gambling Venues With Differing Numbers of Terminals?

- Why Gambling Should Not Be Prohibited or Policed?

- How Has Gambling Become the Favorite Distraction of Americans?

- Should Age Restriction for Gambling Be Increase?

- Are There Net State Social Benefits or Costs From Legalizing Slot Machine Gambling?

- What Are the Possible Circumstances for Gambling?

- How Do Habit and Satisfaction Affect Player Retention for Online Gambling?

- Does DRD2 Taq1A Mediate Aripiprazole-Induced Gambling Disorder?

- How Does the Online Gambling Ban Help Al Qaeda?

- Does Pareto Rule Internet Gambling?

- Should Governments Sponsor Gambling?

- What Are the Problems Associated With Gambling?

- Why Isn’t Congress Closing a Loophole That Fosters Gambling in College?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/

"108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

- Basketball Topics

- Cognitive Therapy Essay Topics

- Bible Questions

- Criminal Behavior Essay Topics

- Sociological Imagination Topics

- Tennis Essay Titles

- Depression Essay Topics

- Economic Topics

- Hobby Research Ideas

- Ethics Ideas

- Online Community Essay Topics

- Mobile Technology Paper Topics

- Social Networking Essay Ideas

- Technology Essay Ideas

- Video Game Topics

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

126 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Gambling is a popular pastime that has been around for centuries. Whether it's placing bets on sports games, playing poker at a casino, or buying lottery tickets, the thrill of risking money in the hopes of winning big is something that many people enjoy.

If you're looking for essay topics related to gambling, you're in luck. We've compiled a list of 126 gambling essay topic ideas and examples to help inspire your next paper. From the ethics of gambling to the impact of online gambling on society, there are plenty of angles to explore in this fascinating topic.

- The history of gambling

- The psychology of gambling addiction

- The ethics of gambling

- The impact of gambling on society

- The economics of gambling

- The role of luck in gambling

- The legality of online gambling

- The relationship between gambling and crime

- The effects of gambling on mental health

- The role of gambling in popular culture

- The impact of gambling on families

- The regulation of gambling

- The social stigma of gambling

- The role of gambling in politics

- The impact of gambling on the economy

- The link between gambling and substance abuse

- The role of gambling in sports

- The impact of gambling on indigenous communities

- The relationship between gambling and religion

- The effects of gambling advertising

- The impact of gambling on tourism

- The relationship between gambling and technology

- The role of gambling in education

- The impact of gambling on the environment

- The link between gambling and mental illness

- The role of gambling in history

- The impact of gambling on the brain

- The relationship between gambling and poverty

- The effects of gambling on relationships

- The role of gambling in the criminal justice system

- The impact of gambling on youth

- The link between gambling and suicide

- The role of gambling in healthcare

- The impact of gambling on the elderly

- The relationship between gambling and gender

- The effects of gambling on personal finances

- The role of gambling in international relations

- The impact of gambling on education

- The link between gambling and public health

- The role of gambling in social welfare

- The impact of gambling on mental health services

- The relationship between gambling and social services

- The effects of gambling on community development

- The role of gambling in urban planning

- The impact of gambling on rural communities

- The link between gambling and economic development

- The role of gambling in environmental conservation

- The impact of gambling on cultural heritage

- The relationship between gambling and human rights

- The effects of gambling on social justice

- The role of gambling in international development

- The impact of gambling on global health

- The link between gambling and international trade

- The role of gambling in sustainable development

- The impact of gambling on climate change

- The relationship between gambling and poverty reduction

- The effects of gambling on gender equality

- The role of gambling in conflict resolution

- The impact of gambling on peacebuilding

- The link between gambling and human security

- The role of gambling in disaster response

- The impact of gambling on humanitarian aid

- The relationship between gambling and international law

- The effects of gambling on global governance

- The role of gambling in international organizations

- The impact of gambling on regional cooperation

- The link between gambling and international relations

- The role of gambling in diplomacy

- The impact of gambling on conflict prevention

- The relationship between gambling and peacekeeping

- The effects of gambling on peacebuilding

- The role of gambling in post-conflict reconstruction

- The impact of gambling on transitional justice

- The link between gambling and human rights

- The role of gambling in international criminal justice

- The impact of gambling on international humanitarian law

- The relationship between gambling and international human rights law

- The effects of gambling on international refugee law

- The role of gambling in international environmental law

- The impact of gambling on international trade law

- The link between gambling and international investment law

- The role of gambling in international economic law

- The impact of gambling on international financial law

- The relationship between gambling and international banking law

- The effects of gambling on international tax law

- The role of gambling in international competition law

- The impact of gambling on international antitrust law

- The link between gambling and international intellectual property law

- The role of gambling in international labor law

- The impact of gambling on international human rights law

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 04 February 2021

The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data

- Naomi Muggleton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6462-3237 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Paula Parpart 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Philip Newall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1660-9254 5 , 6 ,

- David Leake 3 ,

- John Gathergood ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0067-8324 7 &

- Neil Stewart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2202-018X 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 5 , pages 319–326 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3885 Accesses

71 Citations

292 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social policy

Gambling is an ordinary pastime for some people, but is associated with addiction and harmful outcomes for others. Evidence of these harms is limited to small-sample, cross-sectional self-reports, such as prevalence surveys. We examine the association between gambling as a proportion of monthly income and 31 financial, social and health outcomes using anonymous data provided by a UK retail bank, aggregated for up to 6.5 million individuals over up to 7 years. Gambling is associated with higher financial distress and lower financial inclusion and planning, and with negative lifestyle, health, well-being and leisure outcomes. Gambling is associated with higher rates of future unemployment and physical disability and, at the highest levels, with substantially increased mortality. Gambling is persistent over time, growing over the sample period, and has higher negative associations among the heaviest gamblers. Our findings inform the debate over the relationship between gambling and life experiences across the population.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Genome-wide association studies

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from LBG but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of LBG.

Code availability

Data were extracted from LBG databases using Teradata SQL Assistant (v.15.10.1.9). Data analysis was conducted using R (v.3.4.4). The SQL code that supports the analysis is commercially sensitive and is therefore not publicly available. The code is available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of LBG. The R code that supports this analysis can be found at github.com/nmuggleton/gambling_related_harm . Commercially sensitive code has been redacted. This should not affect the interpretability of the code.

Schwartz, D. G. Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling (Winchester Books, 2013).

Supreme Court of the United States. Murphy, Governor of New Jersey et al. versus National Collegiate Athletic Association et al. No. 138, 1461 (2018).

Industry Statistics (Gambling Commission, 2019); https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-industry-statistics.pdf

Cassidy, R. Vicious Games: Capitalism and Gambling (Pluto Press, 2020).

Orford, J. The Gambling Establishment: Challenging the Power of the Modern Gambling Industry and its Allies (Routledge, 2019).

Duncan, P., Davies, R. & Sweney, M. Children ‘bombarded’ with betting adverts during World Cup. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/jul/15/children-bombarded-with-betting-adverts-during-world-cup (15 July 2018).

Hymas, C. Church of England backs ban on gambling adverts during live sporting events. The Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/08/church-england-backs-ban-gambling-adverts-live-sporting-events/ (10 August 2018).

McGee, D. On the normalisation of online sports gambling among young adult men in the UK: a public health perspective. Public Health 184 , 89–94 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Editorial. Science has a gambling problem. Nature 553 , 379 (2018).

National Gambling Strategy (Gambling Commission, 2019); https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/News/gambling-commission-launches-new-national-strategy-to-reduce-gambling-harms

van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Cassidy, R., McKee, M. & Petticrew, M. Gambling control: in support of a public health response to gambling. The Lancet 393 , 1680–1681 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Wardle, H., Reith, G., Langham, E. & Rogers, R. D. Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm. BMJ 365 , l1807 (2019).

Volberg, R. A. Fifteen years of problem gambling prevalence research: what do we know? Where do we go? J. Gambl. Issues https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2004.10.12 (2004).

Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. Corrected Oral Evidence: Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry (UK Parliament, 2019); https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/15/html/

Wardle, H. et al. British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 (National Centre for Social Research, 2011); https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/243515/9780108509636.pdf

Smith, G., Hodgins, D. & Williams, R. Research and Measurement Issues in Gambling Studies (Emerald, 2007).

Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I. & Ross, D. The risk of gambling problems in the general population: a reconsideration. J. Gambl. Stud. 36 , 1133–1159 (2020).

Wood, R. T. & Williams, R. J. ‘How much money do you spend on gambling?’ The comparative validity of question wordings used to assess gambling expenditure. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 10 , 63–77 (2007).

Toneatto, T., Blitz-Miller, T., Calderwood, K., Dragonetti, R. & Tsanos, A. Cognitive distortions in heavy gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 13 , 253–266 (1997).

Wardle, H., John, A., Dymond, S. & McManus, S. Problem gambling and suicidality in England: secondary analysis of a representative cross-sectional survey. Public Health 184 , 11–16 (2020).

Karlsson, A. & Håkansson, A. Gambling disorder, increased mortality, suicidality, and associated comorbidity: a longitudinal nationwide register study. J. Behav. Addict. 7 , 1091–1099 (2018).

Wong, P. W. C., Chan, W. S. C., Conwell, Y., Conner, K. R. & Yip, P. S. F. A psychological autopsy study of pathological gamblers who died by suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 120 , 213–216 (2010).

LaPlante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., LaBrie, R. A. & Shaffer, H. J. Stability and progression of disordered gambling: lessons from longitudinal studies. Can. J. Psychiatry 53 , 52–60 (2008).

Wohl, M. J. & Sztainert, T. Where did all the pathological gamblers go? Gambling symptomatology and stage of change predict attrition in longitudinal research. J. Gambl. Stud. 27 , 155–169 (2011).

Browne, M., Goodwin, B. C. & Rockloff, M. J. Validation of the Short Gambling Harm Screen (SGHS): a tool for assessment of harms from gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 34 , 499–512 (2018).

Browne, M. et al. Assessing Gambling-related Harm in Victoria: A Public Health Perspective (Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, 2016).

Canale, N., Vieno, A. & Griffiths, M. D. The extent and distribution of gambling-related harms and the prevention paradox in a British population survey. J. Behav. Addict. 5 , 204–212 (2016).

Salonen, A. H., Hellman, M., Latvala, T. & Castrén, S. Gambling participation, gambling habits, gambling-related harm, and opinions on gambling advertising in Finland in 2016. Nordisk Alkohol Nark. 35, 215–234 (2018).

Langham, E. et al. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health 16 , 80 (2016).

Wardle, H., Reith, G., Best, D., McDaid, D. & Platt, S. Measuring Gambling-related Harms: A Framework for Action (Gambling Commission, 2018).

Browne, M. & Rockloff, M. J. Prevalence of gambling-related harm provides evidence for the prevention paradox. J. Behav. Addict. 7 , 410–422 (2018).

Collins, P., Shaffer, H. J., Ladouceur, R., Blaszszynski, A. & Fong, D. Gambling research and industry funding. J. Gambl. Stud. 36 , 1–9 (2019).

Google Scholar

Delfabbro, P. & King, D. L. Challenges in the conceptualisation and measurement of gambling-related harm. J. Gambl. Stud. 35 , 743–755 (2019).

Browne, M. et al. What is the harm? Applying a public health methodology to measure the impact of gambling problems and harm on quality of life. J. Gambl. Issues https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2017.36.2 (2017).

Markham, F., Young, M. & Doran, B. The relationship between player losses and gambling-related harm: evidence from nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in four countries. Addiction 111 , 320–330 (2016).

Markham, F., Young, M. & Doran, B. Gambling expenditure predicts harm: evidence from a venue-level study. Addiction 109 , 1509–1516 (2014).

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R. & Shaffer, H. J. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J. Gambl. Stud. 20 , 301–317 (2004).

Rose, G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine (Oxford Univ. Press, 1992).

Improving the Financial Health of the Nation (Financial Inclusion Commission, 2015); https://www.financialinclusioncommission.org.uk/pdfs/fic_report_2015.pdf

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Trendl and H. Wardle for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. We thank R. Burton, Z. Clarke, C. Henn, J. Marsden, M. Regan, C. Sharpe and M. Smolar from Public Health England and L. Balla, L. Cole, K. King, P. Rangeley, H. Rhodes, C. Rogers and D. Taylor from the Gambling Commission for providing feedback on a presentation of this work. We thank A. Akerkar, D. Collins, T. Davies, D. Eales, E. Fitzhugh, P. Jefferson, T. Bo Kim, M. King, A. Lazarou, M. Lien and G. Sanders for their assistance. We thank the Customer Vulnerability team, with whom we worked as part of their ongoing strategy to help vulnerable customers. We acknowledge funding from LBG, who also provided us with the data but had no other role in study design, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of LBG, its affiliates or its employees. We also acknowledge funding from Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grants nos. ES/P008976/1 and ES/N018192/1. The ESRC had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Naomi Muggleton

Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

Naomi Muggleton, Paula Parpart & Neil Stewart

Applied Science, Lloyds Banking Group, London, UK

Naomi Muggleton, Paula Parpart & David Leake

Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Paula Parpart

Warwick Manufacturing Group, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

- Philip Newall

School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQ University, Melbourne, Australia

School of Economics, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

John Gathergood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.P. and P.N. proposed the initial concept. All authors contributed to the design of the analysis and the interpretation of the results. J.G. and N.S. wrote the initial draft; all authors contributed to the revision. N.M. and P.P. constructed variables and N.M. prepared all figures and tables. D.L. established collaboration with LBG. D.L., J.G. and N.S. secured funding for the research. P.N. conducted a review of the existing literature.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Naomi Muggleton .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

N.M. was previously, and D.L. is currently, an employee of LBG. P.P. was previously a contractor at LBG. They do not, however, have any direct or indirect interest in revenues accrued from the gambling industry. P.N. was a special advisor to the House of Lords Select Committee Enquiry on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. In the last 3 years, P.N. has contributed to research projects funded by GambleAware, Gambling Research Australia, NSW Responsible Gambling Fund and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. In 2019, P.N. received travel and accommodation funding from the Spanish Federation of Rehabilitated Gamblers and in 2020 received an open access fee grant from Gambling Research Exchange Ontario. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Aisha Bradshaw.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Tables 1–24.

Reporting Summary

Peer review information, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Muggleton, N., Parpart, P., Newall, P. et al. The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat Hum Behav 5 , 319–326 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w

Download citation

Received : 26 March 2020

Accepted : 23 December 2020

Published : 04 February 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Differences amongst estimates of the uk problem gambling prevalence rate are partly due to a methodological artefact.

- Philip W. S. Newall

- Leonardo Weiss-Cohen

- Peter Ayton

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2024)

When Vegas Comes to Wall Street: Associations Between Stock Price Volatility and Trading Frequency Amongst Gamblers

- Iain Clacher

Skill-Based Electronic Gaming Machines: Features that Mimic Video Gaming, Features that could Contribute to Harm, and Their Potential Attraction to Different Groups

- Matthew Rockloff

- Georgia Dellosa

Journal of Gambling Studies (2024)

A Double-Edged-Sword Effect of Overplacement: Social Comparison Bias Predicts Gambling Motivations and Behaviors in Chinese Casino Gamblers

- Gui-Hai Huang

- Zhu-Yuan Liang

Exploring the Complex Dynamics: Examining the Influence of Deviant Personas in Online Gambling

- Garima Malik

- Dharmendra Singh

- Rohit Bansal

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Gambling behavior and risk factors in preadolescent students: a cross sectional study.

- Department of Psychology, Niccolò Cusano University, Rome, Italy

Although gambling was initially characterized as a specific phenomenon of adulthood, the progressive lowering of the age of onset, combined with earlier and increased access to the game, led researchers to study the younger population as well. According to the literature, those who develop a gambling addiction in adulthood begin to play significantly before than those who play without developing a real disorder. In this perspective, the main hypothesis of the study was that the phenomenon of gambling behavior in this younger population is already associated with specific characteristics that could lead to identify risk factors. In this paper, are reported the results of an exploratory survey on an Italian sample of 2,734 preadolescents, aged between 11 and 14 years, who replied to a self-report structured questionnaire developed ad hoc . Firstly, data analysis highlighted an association between the gambling behavior and individual or ecological factors, as well as a statistically significant difference in the perception of gambling between preadolescent, who play games of chance, and the others. Similarly, the binomial logistic regression performed to ascertain the effects of seven key variables on the likelihood that participants gambled with money showed a statistically significant effect for six of them. The relevant findings of this first study address a literature gap and suggest the need to investigate the preadolescent as a cohort in which it identifies predictive factors of gambling behavior in order to design effective and structured preventive interventions.

Introduction

In recent years, addiction has undergone changes both in terms of choice of the so-called substance and for the age groups involved ( Echeburúa and de Corral Gargallo, 1999 ; Griffiths, 2000 ). Although addiction is a condition associated to substance abuse disorder, it also determines other conducts that can significantly affect the lifestyle of subjects ( Schulte and Hser, 2013 ).

In the last edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ), the pathological gambling behavior has been conceptualized differently than in previous editions, as a result of a series of empirical evidence indicating the commonality of some clinical and neurobiological correlates between pathological gambling and substance use disorders ( Rash et al., 2016 ). The new classification into the “ Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders ” category supports the model of behavioral addictions in which people may be compulsively and dysfunctionally engaged in behaviors that do not involve exogenous drug administration, and these conducts can be conceptualized within an addiction framework as different expressions of the same underlying syndrome ( Shaffer et al., 2004 ).

Despite the fact that in many countries gambling is forbidden to minors, in recent years, there has been a marked increase in this behavior among younger people so that from surveys conducted in different cultural contexts it emerges that a percentage between 60 and 99% of boys and between 12 and 20 years have gambled at least once ( Splevins et al., 2010 ). The increasing number of children and underaged youth participating in games of chance for recreation and entertainment is attributable to the legalization, normalization, and proliferation of gambling opportunities/activities ( Hurt et al., 2008 ).

Several studies have shown that the percentage of young people who gamble in a pathological way is significant and even greater than the percentage of adult pathological gamblers ( Blinn-Pike et al., 2010 ). Using the definitions of at-risk and problem gambler that directly refer to the diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling, the review of Splevins et al. (2010) showed that a percentage of adolescents between 2 and 9% can be classified within the category of problem gamblers, while between 10 and 18% are adolescents who can be considered at-risk gamblers.

The first comprehensive review on problematic gambling in Italy noted a lack of large-scale epidemiological studies and of a national observatory regarding this issue ( Croce et al., 2009 ). More recent studies regarding the Italian national context are now available. A survey carried out with 2,853 students aged between 13 and 20 years showed that 7% of adolescents interviewed were classified as pathological gamblers ( Villella et al., 2011 ), while the study conducted by Donati et al. (2013) indicated that 17% of adolescents showed problematic gambling behaviors.

As far as ecological factors are concerned, the crucial role of family and play behavior of friends has been widely documented. In particular, a strong association between parents’ and children’s gambling behavior has emerged ( Hardoon et al., 2004 ), and it has been highlighted that the spread of gambling in the group of friends influences the practice of gambling among adolescents ( Gupta and Derevensky, 1998 ).

Traditionally, gambling in youth was considered as related to poor academic achievement, truancy, criminal involvement, and delinquency. More recently, investigators have examined the relationship between gambling and delinquent behaviors among adolescents in a systematic way, shifting the understanding beyond the explanation that delinquency associated with problem gambling is merely financially motivated by gambling losses ( Kryszajtys et al., 2018 ). This suggests that young players may have more general problems of conduct than specific criminal behavior.

Conversely, in relation to poor academic achievement, it has been highlighted that problem gambling in adolescence affect students’ performance mainly by reducing the time spent in studying ( Allami et al., 2018 ).

Although the phenomenon of gambling has been widely analyzed in the adult population and there are numerous studies on the adolescent population, the data in the literature suggest that gambling may be a phenomenon already present in preadolescence and needs to be analyzed. In fact, the lowering of the age of onset of problematic behaviors related to pathological gambling raises a question about the presence of gambling in preadolescents, as more exposed to the use of the Internet, smartphones, and tablets as tools that could encourage this type of conduct. A series of studies ( Shaffer and Hall, 2001 ; Vitaro et al., 2004 ; Winters et al., 2005 ; Kessler et al., 2008 ) have highlighted how adult pathological players started playing significantly earlier from a non-pathological player’s chronological point of view.

Nevertheless, it has been seen in the literature as, within the population of those who start playing before the age of 15, only 25% maintain the same frequency of play even in adulthood ( Vitaro et al., 2004 ; Delfabbro et al., 2009 , 2014 ).

In the review by Volberg and colleagues, it was shown how teenagers tend to prefer social and intimate games, such as card games and sports betting, while only a small percentage of teenagers are involved in illegal age gambling activities ( Volberg et al., 2010 ).

Pathological and problem players seem to be more involved in machine gambling (such as slot machines and poker machines), non-strategy games (such as bingo and lottery or super jackpot), and online games; they play in different contexts such as the Internet, school, and dedicated rooms ( Rahman et al., 2012 ; Yip et al., 2015 ).

It has been seen that online gambling is particularly attractive for young people due to its extreme accessibility, the large number of events dedicated to gambling, accessibility from the point of view of the economic share invested, and the multisensory experience and high level of involvement reported by young people ( Brezing et al., 2010 ; King et al., 2010 ).

Considering what is present in the literature, it is evident that the phenomenon of pathological gambling in adulthood is linked to a series of risk factors already present in adolescence. At the same time, the progressive lowering of the age at the beginning, which has been seen to be one of the main risk factors, makes it necessary to analyze the presence of the phenomenon of gambling in preadolescents, an analysis that at this time cannot count on the support of validated tools and questionnaires.

Considering that young people spend part of their time playing, it is necessary to distinguish between what is considered a game and what is considered gambling, even if not in a pathological way.

According to King et al., “gaming is principally defined by its interactivity, skill-based play, and contextual indicators of progression and success. In contrast, gambling is defined by betting and wagering mechanics, predominantly chance-determined outcomes, and monetization features that involve risk and payout to the player” ( King et al., 2015 ).

Primarily, the objective of this study is to verify the presence, the possible extent, and the characteristics of the phenomenon of gambling as defined before in a population of preadolescents (percentage, distribution by gender) to see if the population of preadolescent players shows the same characteristics as those found in larger populations at the age level (adolescents and adults). Secondly, the study aims to verify any differences in the perception of the game between those who play and those who do not, in order to identify additional specific characteristics.

In addition, on the basis of what is highlighted in the literature with respect to the risk factors detected in adults and adolescents, the study aims to assess whether and which of these factors can be predictive of the phenomenon of preadolescent gambling.

Finally, always in line with the identification of possible prodromal factors of gambling, the study wants to analyze the differences with respect to the types of games preferred by preadolescent players to assess any similarity with what emerged in the adolescent population.

In addition, the study aims to verify whether preadolescent players show the same game-level preferences highlighted in the literature as risk factors for the development of a real game disorder ( Rahman et al., 2012 ; Yip et al., 2015 ).

Materials and Methods

The investigation followed the Ethical Standards of the 1994 Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Departmental Research Authorization Committee of Niccolò Cusano University and the Italian Ministry of Labour and Social Policy. In a prospective study of gambling perception, behavior, and risk factors, youth aged 11 to 14 years were recruited from 47 schools situated in 18 regions of Italy. The respondents’ survey was composed by 2,734 preadolescents (1,256 female and 1,452 male), enrolled in the 6, 7, and 8 grades across all national areas (18 provinces out of 20 Italian regions).

The administration of the survey was approved by the school boards of all the institutes involved, and all parents signed the informed consent and authorization to process personal data of their children. The self-report questionnaire was proposed and filled out in the classroom during school time.

The complete questionnaire developed ad hoc by the authors for the survey is composed of 19 items, 6 related to demographic characteristics of the sample and the remaining tighter focused on gambling behaviors and information related to the context of the subject. An excerpt of all the analyzed questionnaire items is provided in the appendix to facilitate the understanding of the Likert scale administered (see Supplementary Data Sheet 4 ).

After data screening, which excluded incomplete/invalid questionnaires, the sample presented the following characteristics: gender, 1,312 male (53%) and 1,163 female (47%); nationality, 93% Italian and 7% others; age: M = 12.36, SD = 0.95, distributed in 11 years old n = 541 (21.9%), 12 years old n = 803 (32.4%), 13 years old n = 841 (34.0%), and 14 years old n = 290 (11.7%).

Gamblers were defined as individuals who showed gambling behaviors in the previous year, classified as the ones who answered “yes” to the question “In the last twelve months did you game and gamble money playing any game?”

In the first sets of analysis, data were examined to determine whether there was an association between the gambling behavior and individual or ecological factors measured on nominal, continuous, or ordinal scales. Variable dependence was assessed as appropriate using chi-square for nominal variables, t -test for comparing groups on two continuous variables (e.g., age), or the sound nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test to confront two ordinal variables (e.g., Likert 5/4-point scale from fully agree to fully disagree). The decision to apply nonparametric tests was made considering the correlational research design of the survey and the non-previously validated questionnaire as the tool for collecting data. Moreover, the utilization of nonparametric analysis gives the most accurate estimates of significance in case of non-normal data distributions and variables of intrinsic ordinal nature as the ones obtained from Likert items in the questionnaire ( Laake et al., 2015 ).

For the same reason, a Friedman test was run to determine if there were differences in the playing rates of gamers concerning different games of chance, because this nonparametric test determines if there are differences between more than two variables measured on ordinal scales, e.g., when the answers to the questionnaire items are a rank ( Conover, 1999 ). The different categories of game taken into account were “videopoker, slot machine e video slot,” “lotto, lottery and superjackpot,” “Scratch card,” “Sport bets,” and “Daily fantasy sports.”

The second set of analyses examined the probability of being in the category “gamblers” of the dependent variable given the set of relevant independent variables already identified in base of preliminary analysis results and substantive literature support. More specifically, the following variables measured by the questionnaire were analyzed: gender, inappropriate school behavior, parent with gambling behavior, and troubles with parent – videogame-related and gambling-related. In this perspective, model selection in the multivariate logistic regression is aimed to the understanding of possible causes, knowing that certain variables did not explain much of the variation in gambling could suggest that they are probably not important causes of the variation in predicted variable. Moreover, introduction of too many variables could not only violate the parsimony principle but also produce numerically unstable estimates due to overfitting ( Rothman et al., 2008 ).

Individual characteristics of participants who gambled (gamblers) versus participants who did not gamble (nongamblers) are shown in Supplementary Table S1 .

Gamblers were more likely males, older, and showed a higher record of inappropriate behavior at school in the past. Moreover, the parents of these students presented a higher proportion of gambling behavior and family conflicts related to playing videogames or gambling. As shown in Supplementary Table S2 , the two groups also differed significantly on the variable “online gambling without money.”

Subsequently, several Mann-Whitney U tests were run to determine if there were differences in the perception of many gambling’s facets (measured through self-report scores) between gamblers and nongamblers. To analyze the perception of the game and any differences between players and nonplayers have been isolated four variables measured through the following items: “loosing money because of gambling,” “becoming rich through gambling,” “gambling is funny,” “gambling is an exciting activity.” The distributions of the perception scores for gamers and not gamers on these four items were similar, as assessed by visual inspection. Median perception of gambling as a risk was statistically significantly lower in gamblers (3) than in nongamblers (4), U = 344, z = −4.59, p < 0.001, as well as the difference between median perception scores of gambling as an habit was statistically significantly lower in gamblers (3) than in nongamblers (4); U = 357, z = −3.48, p < 0.001. Statistically significant differences were also found between the median perception scores of gamblers and nongamblers on the variable “ losing money because of gambling ” [lower in gamblers (3) than in nongamblers (4); U = 327, z = −6.27, p < 0.001] and “ becoming rich through gambling ” [higher in gamblers (2) than in nongamblers (1); U = 519, z = 9.879, p < 0.001].

Differently, on two similar items regarding the perception of gambling as an entertaining activity and as an exciting activity, the distributions for gamblers and nongamblers were not similar, as assessed by visual inspection. One of the two items concerned the perception of gambling as an entertaining activity; the Mann-Whitney U test revealed that scores for gamblers (mean rank = 1.8) were significantly higher than for nongamblers (mean rank = 1.14; U = 608, z = 17.52, p < 0.001). The last item concerned the perception of gambling as an exciting activity; the Mann-Whitney U test revealed that scores for gamblers (mean rank = 1.7) were significantly higher than for nongamblers (mean rank = 1.16; U = 569, z = 14.23, p < 0.001).

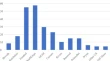

For this reason, a Friedman test was run to determine if there were differences in the playing rates of gamers concerning different games of chance, because this nonparametric test determine if there are differences between more than two variables measured on ordinal scale, i.e., when the answers to the questionnaire items are a rank ( Conover, 1999 ). The students who stated to have gambled money in the previous 12 months were asked in the following question about the frequency they played different group of games.

Pairwise comparisons were performed ( IBM Corporation Released, 2017 ) with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Gambling/playing rate was statistically significantly different in the five groups of games, χ 2 (4) = 226.693, p < 0.0005. The values of post hoc analysis are presented in Supplementary Table S2 , and the Pairwise Friedman’s comparisons revealed relevant statistically significant differences in playing rates of gamers. In fact, the category of game of chance constituted by “videopoker, slot machine e video slot” (mean rank = 2.46) is preferred to all other kinds of game of chance, except “lotto, lottery and superjackpot” (mean rank = 2.50). In the case of “Lotto, lottery, SuperJackpot,” this category of game of chance is preferred to “Scratch card” (mean rank = 3.30) in a statistically significant way, but it is also statistically less played in comparison to “Sport bets” (mean rank = 3.35) and “Daily fantasy sports” (mean rank = 3.40). None of the remaining differences were statistically significant.

Regarding the second set of analyses, Supplementary Table S3 provides the model used in the binomial logistic regression performed to ascertain the effects of key variables on the likelihood that participants played game of chance with money. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ 2 (7) = 326, p < 0.001. The model explained 23.0% (Nagelkerke R 2 ) of the variance in the predicted variable (gambling behavior) and demonstrated a percentage accuracy in classification (PAC) equal to 86.6%. Sensitivity was 22.5%, specificity was 97.6%, positive predictive value was 62.2%, and negative predictive value was 87.9%. Of the seven predictor variables only six were statistically significant: gender, inappropriate school behavior, parents with gambling behavior, troubles with parents – videogames related, online gambling without money, and age (as shown in Supplementary Table S3 ). Analysis showed that male had 2.96 times higher odds to be gamers than females (OR = 0.337; 95% CI 0.248–0.458), and increasing age was associated with an increased likelihood of gambling behavior. Also, inappropriate school behavior (OR = 1.859; 95% CI 1.395–2.477), parents with gambling behavior (OR = 3.836; 95% CI 2.871–5.125), troubles with parents – videogames related (OR = 1.285; 95% CI.510–3.236), and online gambling without money (OR = 2.297; 95% CI 1.681–3.139) increased the likelihood of gambling. By contrast, the “Troubles with parents – gambling related” variable was not statistically significant, probably because of the extremely unbalanced case ratio between the two modalities.

The first objective of this study was to evaluate the presence or absence and the consequent extent of the phenomenon of gambling in a population of preadolescents and to understand which factors are associated to the progressive lowering of the age of onset.

Consistently with the literature on the adult and adolescent population, the evidence presented thus far supports the idea that even in the preadolescent population players tend to be predominantly males ( Hurt et al., 2008 ; Splevins et al., 2010 ; Villella et al., 2011 ; Dowling et al., 2017 ).

One of the more significant findings to emerge from this study is that players of game of chance have a significantly different perception of the game than nonplayers, i.e., they see the game as “less risky” and perceive less risk of losing money through the game. In addition, confirming this “altered” perception, they show higher values than nonplayers in the perception of being able to become rich through the game ( Hurt et al., 2008 ; Dowling et al., 2017 ). Gamblers have a perception of the game as exciting and fun, a tendency which increases with age. This pattern seems to confirm what is expressed in the literature regarding the theme of sensation seeking and its connection with the development of gambling disease ( Dickson et al., 2002 , 2008 ; Hardoon and Derevensky, 2002 ; Messerlian et al., 2007 ; Blinn-Pike et al., 2010 ; Shead et al., 2010 ; Ariyabuddhiphongs, 2011 ; Lussier et al., 2014 ).

Even more importantly, some possible predictive factors of gambling emerged among the variables analyzed: thus, the phenomenon of gambling was associated with problems of school conduct, problems with parents related to the use of video games and, interestingly, also to the presence of parents who are gamers.

Since there are no validated tools in the literature for the diagnosis of preadolescent gambling, the analyses were conducted on those who were “gamblers” according to what was previously stated. It is therefore of particular relevance that the sample of preadolescent gamblers shows descriptive characteristics and predictive factors similar to those highlighted by the literature on adolescent gamblers with a diagnosis of gambling.

In this sense, the analysis of the most frequently used game types is particularly important.

With respect to the game categories analyzed, with the exception of “Lotto, lottery, SuperJackpot,” the category that is most frequently chosen by the sample of gamblers is that of “videopoker, slot machine e video slot.”

These data are of particular relevance considering that some studies in the literature have shown that adult pathological players have shown in previous ages a strong preference for these types of games. Although it is necessary to investigate with further studies the reasons underlying the choice of this type of game by preadolescents, this fact suggests that the phenomenon of preadolescent gambling has a number of aspects and characteristics common to those identified by the literature in the analysis of the precursors of pathological gambling.

There are some issues to take under consideration in framing the present results. Regarding the sample, although the numerous participants and the geographical representativeness of the population, the sample was not randomly selected. Therefore, we cannot exclude that subjects were unbalanced on unobserved, causally relevant concomitants. Although the methodology allows prediction, it should be noted that causality cannot be established from this survey, because the research design does not properly establish temporal sequence. In addition, only self-report measures and not thoroughly validated scales were used, as the objective of this study was to conduct an exploratory survey on the characteristics of the phenomenon, and there were some dichotomous variable with uneven case ratios. Furthermore, some constructs related to gambling behavior (e.g., impulsivity) and neurocognitive functioning were not analyzed in designing this first study; although in the wider research program, it is intended to explore also these factors.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study makes some noteworthy contributions to the understanding of the phenomenon of gambling and its characteristics in a population (preadolescents) which is still not very explored in the literature.

In particular, one significant finding is that the lowering of the age has not substantially changed what has been established in the literature with respect to the phenomenon in adolescents: the characteristics of players in terms of gender are substantially unchanged in the comparison between adolescents and preadolescents.

Moreover, from the analyses carried out, it appears that those that the literature has highlighted as risk factors of gambling in adolescence and adulthood are already present in younger players and may be predictive factors of gambling conduct already in preadolescence.

The data show, moreover, that the perception of gambling for those who play is significantly different from those who do not play, and specifically on aspects related to attractiveness, the low perception of risk and the possibility of getting rich easily. Finally, even with respect to an analysis carried out on different types of games, what emerged from the literature as additional risk factors for adolescents and adults is already present in preadolescence.

The findings of this study focus on the need to investigate the preadolescent age group in order to identify specific predictive factors of gambling in order to structure effective and structured preventive interventions and the parallel need to structure a standardized tool for the diagnosis of gambling in this specific population.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The study was carried out according to the principles of the 2012–2013 Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the parents of all children. The study was approved by the IRB of the Department of Psychology of Niccolò Cusano University of Rome.

Author Contributions

NV and GF designed and performed the design of the study and conducted the literature searches. CD, MC, and GP provided the acquisition of the data, while FM undertook the statistical analyses. NV, CP, and FM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors significantly participated in interpreting the results, revising the manuscript, and approved its final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01287/full#supplementary-material

Allami, Y., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Carbonneau, R., and Tremblay, R. E. (2018). Identifying at-risk profiles and protective factors for problem gambling: a longitudinal study across adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 32, 373–382. doi: 10.1037/adb0000356

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. (2011). Before, during and after measures to reduce gambling harm: commentaries. Addiction 106, 12–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03178.x

Blinn-Pike, L., Worthy, S. L., and Jonkman, J. N. (2010). Adolescent gambling: a review of an emerging field of research. J. Adolesc. Health 47, 223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.003

Brezing, C., Derevensky, J. L., and Potenza, M. N. (2010). Non–substance-addictive behaviors in youth: pathological gambling and problematic internet use. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 19, 625–641. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.012

Conover, W. J. (1999). “Wiley series in probability and statistics. Applied probability and statistics section” in Practical nonparametric statistics. 3rd edn. (New York: Wiley).

Google Scholar

Croce, M., Lavanco, G., Varveri, L., and Fiasco, M. (2009). Problem gambling in Europe: Challenges, prevention, and interventions. (NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media), 153–171.

Delfabbro, P., King, D., and Griffiths, M. D. (2014). From adolescent to adult gambling: an analysis of longitudinal gambling patterns in South Australia. J. Gambl. Stud. 30, 547–563. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9384-7

Delfabbro, P. H., Winefield, A. H., and Anderson, S. (2009). Once a gambler – always a gambler? A longitudinal analysis of gambling patterns in young people making the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Int. Gambl. Stud. 9, 151–163. doi: 10.1080/14459790902755001

Dickson, L. M., Derevensky, J. L., and Gupta, R. (2002). The prevention of gambling problems in youth: a conceptual framework. J. Gambl. Stud. 18, 97–159.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Dickson, L., Derevensky, J. L., and Gupta, R. (2008). Youth gambling problems: examining risk and protective factors. Int. Gambl. Stud. 8, 25–47. doi: 10.1080/14459790701870118

Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., and Primi, C. (2013). A model to explain at-risk/problem gambling among male and female adolescents: gender similarities and differences. J. Adolesc. 36, 129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.10.001

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., and Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.008

Echeburúa, E., and de Corral Gargallo, P. (1999). Avances en el tratamiento cognitivo-conductual de los trastornos de personalidad. Análisis y modificación de conducta. 25, 585–614.

Griffiths, M. (2000). Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 3, 211–218. doi: 10.1089/109493100316067

Gupta, R., and Derevensky, J. L. (1998). Adolescent gambling behavior: a prevalence study and examination of the correlates associated with problem gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 14, 319–345. doi: 10.1023/A:1023068925328

Hardoon, K. K., and Derevensky, J. L. (2002). Child and adolescent gambling behavior: current knowledge. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 7, 263–281. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007002012

Hardoon, K. K., Gupta, R., and Derevensky, J. L. (2004). Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 18, 170–179. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.170

Hurt, H., Giannetta, J. M., Brodsky, N. L., Shera, D., and Romer, D. (2008). Gambling initiation in preadolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 43, 91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.018

IBM Corporation Released (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation).

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., and Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for problematic video game players: Conceptual considerations and practice issues. J. Cyber Ther. Rehabil. 3, 261–273.

King, D. L., Gainsbury, S. M., Delfabbro, P. H., Hing, N., and Abarbanel, B. (2015). Distinguishing between gaming and gambling activities in addiction research. J. Behav. Addict. 4, 215–220. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.045

Kryszajtys, D. T., Hahmann, T. E., Schuler, A., Hamilton-Wright, S., Ziegler, C. P., and Matheson, F. I. (2018). Problem gambling and delinquent behaviours among adolescents: a scoping review. J. Gambl. Stud. 34, 893–914. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9754-2

Laake, P., Benestad, H. B., and Olsen, B. R. (2015). Research in medical and biological sciences: From planning and preparation to grant application and publication. (Amsterdam/Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press).

Lussier, I. D., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R., and Vitaro, F. (2014). Risk, compensatory, protective, and vulnerability factors related to youth gambling problems. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 28, 404–413. doi: 10.1037/a0034259

Messerlian, C., Gillespie, M., and Derevensky, J. L. (2007). Beyond drugs and alcohol: including gambling in a high-risk behavioural framework. Paediatr. Child Health 12, 199–204. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.3.199

Rahman, A. S., Pilver, C. E., Desai, R. A., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L., Krishnan-Sarin, S., et al. (2012). The relationship between age of gambling onset and adolescent problematic gambling severity. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46, 675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.007

Rash, C., Weinstock, J., and Van Patten, R. (2016). A review of gambling disorder and substance use disorders. Subst. Abus. Rehabil. 3–13. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S83460

Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., and Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn. (Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York: Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins).

Schulte, M. T., and Hser, Y.-I. (2013). Substance use and associated health conditions throughout the lifespan. Public Health Rev. 35. doi: 10.1007/BF03391702

Shaffer, H. J., and Hall, M. N. (2001). Updating and refining prevalence estimates of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada. Can. J. Public Health 92, 168–172.

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R. C., Donato, A. N., and Stanton, M. V. (2004). Toward a syndrome model of addiction: multiple expressions, common etiology. Har. Rev. Psychiatry 12, 367–374. doi: 10.1080/10673220490905705

Shead, N. W., Derevensky, J. L., and Gupta, R. (2010). Risk and protective factors associated with youth problem gambling. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 22, 39–58.

Splevins, K., Mireskandari, S., Clayton, K., and Blaszczynski, A. (2010). Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling, related harms and help-seeking behaviours among an Australian population. J. Gambl. Stud. 26, 189–204. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9169-1

Villella, C., Martinotti, G., Di Nicola, M., Cassano, M., La Torre, G., Gliubizzi, M. D., et al. (2011). Behavioural addictions in adolescents and young adults: results from a prevalence study. J. Gambl. Stud. 27, 203–214. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9206-0

Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., Ladouceur, R., Brendgen, M., and Tremblay, R. E. (2004). Trajectories of gambling during adolescence. J. Gambl. Stud. 20, 47–69. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGS.0000016703.84727.d3

Volberg, R. A., Gupta, R., Griffiths, M. D., Olason, D. T., and Delfabbro, P. (2010). An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 22, 3–38.

Winters, K. C., Stinchfield, R. D., Botzet, A., and Slutske, W. S. (2005). Pathways of youth gambling problem severity. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 19, 104–107. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.104

Yip, S. W., Mei, S., Pilver, C. E., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L. J., Krishnan-Sarin, S., et al. (2015). At-risk/problematic shopping and gambling in adolescence. J. Gambl. Stud. 31, 1431–1447. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9494-x

Keywords: gambling, risk factors, preadolescence, addiction, prevention

Citation: Vegni N, Melchiori FM, D’Ardia C, Prestano C, Canu M, Piergiovanni G and Di Filippo G (2019) Gambling Behavior and Risk Factors in Preadolescent Students: A Cross Sectional Study. Front. Psychol . 10:1287. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01287

Received: 15 February 2019; Accepted: 16 May 2019; Published: 12 June 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Vegni, Melchiori, D’Ardia, Prestano, Canu, Piergiovanni and Di Filippo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicoletta Vegni, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 27 August 2020

Risk factors for gambling and problem gambling: a protocol for a rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Caryl Beynon 1 ,

- Nicola Pearce-Smith 1 &

- Rachel Clark ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2800-2713 1

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 198 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

4845 Accesses

3 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gambling and problem gambling are increasingly being viewed as a public health issue. European surveys have reported a high prevalence of gambling, and according to the Gambling Commission, in 2018, almost half of the general population aged 16 and over in England had participated in gambling in the 4 weeks prior to being surveyed. The potential harms associated with gambling and problem are broad, including harms to individuals, their friends and family, and society. There is a need to better understand the nature of this issue, including its risk factors. The purpose of this study is to identify and examine the risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling.

An umbrella review will be conducted, where systematic approaches will be used to identify, appraise and synthesise systematic reviews and meta-analyses of risk factors for gambling and problem gambling. The review will include systematic reviews and meta-analyses published between 2005 and 2019, in English language, focused on any population and any risk factor, and of quantitative or qualitative studies. Electronic searches will be conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycInfo, NICE Evidence and SocIndex via EBSCO, and a range of websites will be searched for grey literature. Reference lists will be scanned for additional papers and experts will be contacted. Screening, quality assessment and data extraction will be conducted in duplicate, and quality assessment will be conducted using AMSTAR-2. A narrative synthesis will be used to summarise the results.

The results of this review will provide a comprehensive and up-to-date understanding of the risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling. It will be used by Public Health England as part of a broader evidence review of gambling-related harms.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019151520

Peer Review reports