Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.4 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This book is primarily about quantitative research . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from each of a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study many psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To do this, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this book is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, or that female college students are not substantially more talkative than male college students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And it is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973). Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

As with correlational research, data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews . Interviews in qualitative research tend to be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them. The researcher can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that do come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. This was essentially the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide survivors. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as focus groups . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses.

Another approach to data collection in qualitative research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. The data they collect can include interviews (usually unstructured), their own notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. An example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins (published in Social Psychology Quarterly ) on a college-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008). Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009). Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 7.1 “Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers” shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

Table 7.1 Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

- Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic?

Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 .

Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press.

Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Research and Hypothesis Testing: Moving from Theory to Experiment

- First Online: 14 November 2019

Cite this chapter

- Mark W. Scerbo 6 ,

- Aaron W. Calhoun 7 &

- Joshua Hui 8

2203 Accesses

In this chapter, we discuss the theoretical foundation for research and why theory is important for conducting experiments. We begin with a brief discussion of theory and its role in research. Next, we address the relationship between theory and hypotheses and distinguish between research questions and hypotheses. We then discuss theoretical constructs and how operational definitions make the constructs measurable. Next, we address the experiment and its role in establishing a plan to test the hypothesis. Finally, we offer an example from the literature of an experiment grounded in theory, the hypothesis that was tested, and the conclusions the authors were able to draw based on the hypothesis. We conclude by emphasizing that theory development and refinement does not result from a single experiment, but instead requires a process of research that takes time and commitment.

- Null hypothesis

- Operation definition

- PICO framework

- Research question

- Theoretical construct

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Badia P, Runyon RP. Fundamentals of behavioral research. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1982.

Google Scholar

Roeckelein JE. Elsevier’s dictionary of psychological theories. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2006.

Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Designing experiments and analyzing data: a model comparison perspective. 2nd ed. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2004.

Graziano AM, Raulin ML. Research methods: a process of inquiry. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2000.

Passer MW. Research methods: concepts and connections. New York: Worth; 2014.

Weinger MB, Herndon OW, Paulus MP, Gaba D, Zornow MH, Dallen LD. An objective methodology for task analysis and workload assessment in anesthesia providers. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:77–92.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Warm JS. An introduction to vigilance. In: Warm JS, editor. Sustained attention in human performance. Chichester: Wiley; 1984. p. 1–14.

Freud S. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Volume XIX (1923–1926) The ego and the id and other works. Strachey, James, Freud, Anna, 1895–1982, Rothgeb, Carrie Lee, 1925-, Richards, Angela, Scientific literature corporation. London: Hogarth Press; 1978.

Mill JS. A system of logic, vol. 1. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific; 2002. p. 1843.

Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406.

Article Google Scholar

Darian S. Understanding the language of science. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2003.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

Calhoun AW, Gaba DM. Live or let die: new developments in the ongoing debate over mannequin death. Simul Healthc. 2017;12:279–81.

Goldberg A, et al. Exposure to simulated mortality affects resident performance during assessment scenarios. Simul Healthc. 2017;12:282–8.

Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, Mckoy NA. Frameworks for determining research gaps during systematic reviews. Report No.: 11-EHC043-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011.

O’Sullivan D, Wilk S, Michalowski W, Farion K. Using PICO to align medical evidence with MDs decision making models. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:1057.

PubMed Google Scholar

Christensen LB, Johnson RB, Turner LA. Research methods: design and analysis. 12th ed. Boston: Pearson; 2014.

Keppel G. Design and analysis: a researcher’s handbook. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1982.

Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ. State-trait anxiety inventory and state-trait anger expression inventory. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. p. 292–321.

Cheng A, et al. Reporting guidelines for health care simulation research: extensions to the CONSORT and STROBE statements. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(4):238–48.

Turner TR, Scerbo MW, Gliva-McConvey G, Wallace AM. Standardized patient encounters: periodic versus postencounter evaluation of nontechnical clinical performance. Simul Healthc. 2016;11:174–2.

Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ. Working memory. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation: advances in research and theory. 8th ed. New York: Academic; 1974. p. 47–89.

Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1962.

Newton-Smith WH. The rationality of science. London: Routledge & Keegan Paul; 1981.

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA

Mark W. Scerbo

Department of Pediatrics, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY, USA

Aaron W. Calhoun

Emergency Medicine, Kaiser Permanente, Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark W. Scerbo .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Monash Institute for Health and Clinical Education, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Debra Nestel

Department of Surgery, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Baltimore, MD, USA

Kevin Kunkler

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Scerbo, M.W., Calhoun, A.W., Hui, J. (2019). Research and Hypothesis Testing: Moving from Theory to Experiment. In: Nestel, D., Hui, J., Kunkler, K., Scerbo, M., Calhoun, A. (eds) Healthcare Simulation Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26837-4_22

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26837-4_22

Published : 14 November 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-26836-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-26837-4

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Getting Started

- GLG Institute

- Expert Witness

- Integrated Insights

- Qualitative

- Featured Content

- Medical Devices & Diagnostics

- Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology

- Industrials

- Consumer Goods

- Payments & Insurance

- Hedge Funds

- Private Equity

- Private Credit

- Investment Managers & Mutual Funds

- Investment Banks & Research

- Consulting Firms

- Advertising & Public Relations

- Law Firm Resources

- Social Impact

- Clients - MyGLG

- Network Members

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research — Here’s What You Need to Know

Will Mellor, Director of Surveys, GLG

Read Time: 0 Minutes

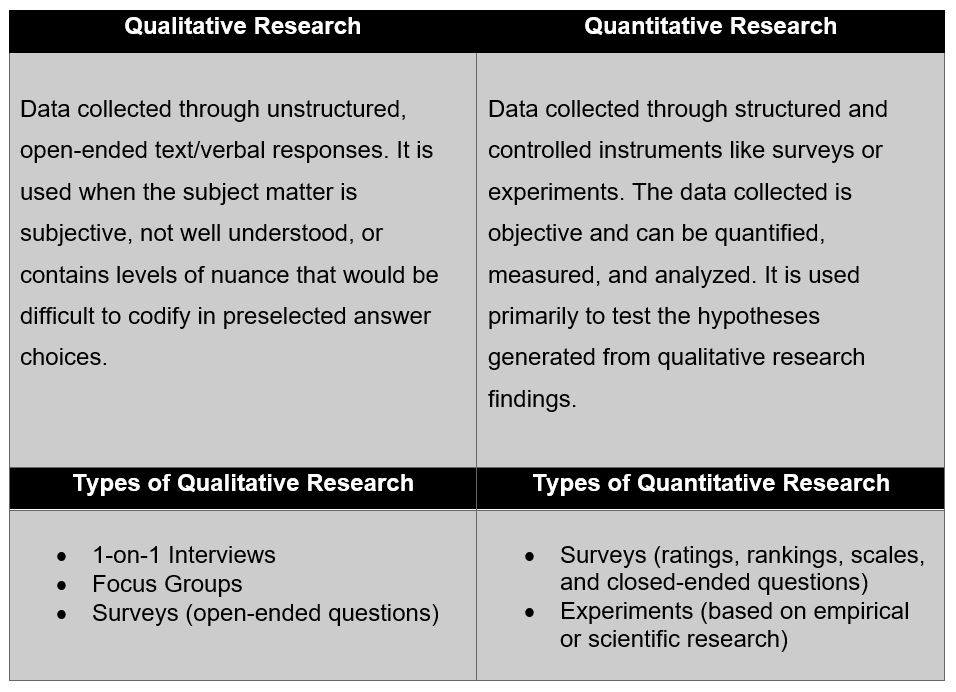

Qualitative vs. Quantitative — you’ve heard the terms before, but what do they mean? Here’s what you need to know on when to use them and how to apply them in your research projects.

Most research projects you undertake will likely require some combination of qualitative and quantitative data. The magnitude of each will depend on what you need to accomplish. They are opposite in their approach, which makes them balanced in their outcomes.

When Are They Applied?

Qualitative

Qualitative research is used to formulate a hypothesis . If you need deeper information about a topic you know little about, qualitative research can help you uncover themes. For this reason, qualitative research often comes prior to quantitative. It allows you to get a baseline understanding of the topic and start to formulate hypotheses around correlation and causation.

Quantitative

Quantitative research is used to test or confirm a hypothesis . Qualitative research usually informs quantitative. You need to have enough understanding about a topic in order to develop a hypothesis you can test. Since quantitative research is highly structured, you first need to understand what the parameters are and how variable they are in practice. This allows you to create a research outline that is controlled in all the ways that will produce high-quality data.

In practice, the parameters are the factors you want to test against your hypothesis. If your hypothesis is that COVID is going to transform the way companies think about office space, some of your parameters might include the percent of your workforce working from home pre- and post-COVID, total square footage of office space held, and/or real-estate spend expectations by executive leadership. You would also want to know the variability of those parameters. In the COVID example, you will need to know standard ranges of square footage and real-estate expenditures so that you can create answer options that will capture relevant, high-quality, and easily actionable data.

Methods of Research

Often, qualitative research is conducted with a small sample size and includes many open-ended questions . The goal is to understand “Why?” and the thinking behind the decisions. The best way to facilitate this type of research is through one-on-one interviews, focus groups, and sometimes surveys. A major benefit of the interview and focus group formats is the ability to ask follow-up questions and dig deeper on answers that are particularly insightful.

Conversely, quantitative research is designed for larger sample sizes, which can garner perspectives across a wide spectrum of respondents. While not always necessary, sample sizes can sometimes be large enough to be statistically significant . The best way to facilitate this type of research is through surveys or large-scale experiments.

Unsurprisingly, the two different approaches will generate different types of data that will need to be analyzed differently.

For qualitative data, you’ll end up with data that will be highly textual in nature. You’ll be reading through the data and looking for key themes that emerge over and over. This type of research is also great at producing quotes that can be used in presentations or reports. Quotes are a powerful tool for conveying sentiment and making a poignant point.

For quantitative data, you’ll end up with a data set that can be analyzed, often with statistical software such as Excel, R, or SPSS. You can ask many different types of questions that produce this quantitative data, including rating/ranking questions, single-select, multiselect, and matrix table questions. These question types will produce data that can be analyzed to find averages, ranges, growth rates, percentage changes, minimums/maximums, and even time-series data for longer-term trend analysis.

Mixed Methods Approach

You aren’t limited to just one approach. If you need both quantitative and qualitative data, then collect both. You can even collect both quantitative and qualitative data within one type of research instrument. In a survey, you can ask both open-ended questions about “Why?” as well as closed-ended, data-related questions. Even in an unstructured format, like an interview or focus group, you can ask numerical questions to capture analyzable data.

Just be careful. While qualitative themes can be generalized, it can be dangerous to generalize on such a small sample size of quantitative data. For instance, why companies like a certain software platform may fall into three to five key themes. How much they spend on that platform can be highly variable.

The Takeaway

If you are unfamiliar with the topic you are researching, qualitative research is the best first approach. As you get deeper in your research, certain themes will emerge, and you’ll start to form hypotheses. From there, quantitative research can provide larger-scale data sets that can be analyzed to either confirm or deny the hypotheses you formulated earlier in your research. Most importantly, the two approaches are not mutually exclusive. You can have an eye for both themes and data throughout the research process. You’ll just be leaning more heavily to one or the other depending on where you are in your understanding of the topic.

Ready to get started? Get the actionable insights you need with the help of GLG’s qualitative and quantitative research methods.

About Will Mellor

Will Mellor leads a team of accomplished project managers who serve financial service firms across North America. His team manages end-to-end survey delivery from first draft to final deliverable. Will is an expert on GLG’s internal membership and consumer populations, as well as survey design and research. Before coming to GLG, he was the vice president of an economic consulting group, where he was responsible for designing economic impact models for clients in both the public sector and the private sector. Will has bachelor’s degrees in international business and finance and a master’s degree in applied economics.

For more information, read our articles: Three Ways to Apply Qualitative Research , Focusing on Focus Groups: Best Practices, What Type of Survey Do You Need?, or The 6 Pillars of Successful Survey Design

You can also download our eBooks: GLG’s Guide to Effective Qualitative Research or Strategies for Successful Surveys

Enter your contact information below and a member of our team will reach out to you shortly.

Thank you for contacting GLG, someone will respond to your inquiry as soon as possible.

Subscribe to Insights 360

Enter your email below and receive our monthly newsletter, featuring insights from GLG’s network of approximately 1 million professionals with first-hand expertise in every industry.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes.2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed ...

First, stating a prior hypothesis that is to be tested deductively is quite rare in qualitative research. One way this can be done is to divide the the total set of participants into so ...

objectives, and hypotheses; and mixed methods research questions. QUALITATIVE RESEARCH QUESTIONS In a qualitative study, inquirers state research questions, not objectives (i.e., specific goals for the research) or hypotheses (i.e., predictions that involve variables and statistical tests). These research questions assume two forms:

The problem here is with. the term test. Normally, in quantitative research designs, testing. hypotheses involves manipulating variables so as to isolate specific factors and observe their effect on learning outcomes. Thus, the researcher needs to hypothesize what the significant relationships are before the research.

The Hypothesis Tester allows a researcher to generate a theoretical framework inductively from their data, or to test out a preexisting set of theoretical ideas on a given data set deductively. The hypothesis-testing component of HyperRESEARCH provides a semiformal mechanism for theory building and hypothesis testing.

While many books and articles guide various qualitative research methods and analyses, there is currently no concise resource that explains and differentiates among the most common qualitative approaches. We believe novice qualitative researchers, students planning the design of a qualitative study or taking an introductory qualitative research course, and faculty teaching such courses can ...

Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is "grounded in" those data.

in qualitative research. Based on its objective of creating an understanding of qualitative research to provide guidelines on how qualitative researchers can use (include formulate, write and test) hypotheses, this study uses the evidence available in the literature to explore and present arguments in support of hypothesis-driven qualitative ...

An experiment represents the actual plan and process for testing the hypothesis. A hypothesis suggests how the theory will be tested, but not the specific details. The Method section of a research paper describes the details of the experiment and how the hypothesis was formally tested.

This study uses Chigbu's work to illustrate the "how-to" aspect of testing a research hypothesis in qualitative research. Qualitative hypothesis testing is the process of using qualitative research data to determine whether the reality of an event (situation or scenario) described in a specific hypothesis is true or false, or occurred or ...

Generally, we tend to cull out a few hypotheses or propositions from the existing theory, and then attempt to test the former in the case under investigation. This is akin to deductive 7 approach in social science research. Hypothesis testing is best achieved through the process of 'falsification' as propounded by Popper . The doctrine of ...

Depending on the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis methods, there are various methods and techniques that qualitative researchers use to test their hypotheses ...

There are 5 main steps in hypothesis testing: State your research hypothesis as a null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis (H o) and (H a or H 1 ). Collect data in a way designed to test the hypothesis. Perform an appropriate statistical test. Decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis. Present the findings in your results ...

6. Write a null hypothesis. If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing, you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0, while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a.

qualitative hypothesis - testing theory te sting as well as concept-guided descriptive research, which is research that begins with sensitizing concepts. The use of sensit izing concepts is

Deductive qualitative analysis (DQA; Gilgun, 2005) is a specific approach to deductive qualitative research intended to systematically test, refine, or refute theory by integrating deductive and inductive strands of inquiry.The purpose of the present paper is to provide a primer on the basic principles and practices of DQA and to exemplify the methodology using two studies that were conducted ...

usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require bo th quantitative and qualitative

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research, which involves collecting and ...

For this reason, qualitative research often comes prior to quantitative. It allows you to get a baseline understanding of the topic and start to formulate hypotheses around correlation and causation. Quantitative. Quantitative research is used to test or confirm a hypothesis. Qualitative research usually informs quantitative.